95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Phys. , 24 October 2023

Sec. Nuclear Physics

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2023.1247311

This article is part of the Research Topic Cross Section Data of Interest for Nuclear Astrophysics: Experimental and Theoretical Status, and Perspectives View all 7 articles

Analysis of the latest high–precision cross sections of (α,γ) and (α,n) reactions on 144Sm below the Coulomb barrier is carried out using a consistent parameter set of the statistical model. This prevents the need to use empirical rescaling factors of either γ or neutron widths. Particular attention is paid to uncertainties of the calculated cross sections which are related to the accuracy of the primary data that were used to set up the consistent input parameters. The calculated cross sections are found in good agreement with the new experimental data for the 144Sm(α,n)147Gd reaction; however, the same is not true for the excitation function of 144Sm(α,γ)148Gd which decreases faster at incident energies below ∼12 MeV. An increase of the α-particle direct collective inelastic scattering at lower energies is found responsible for this decrease of the (α,γ) reaction cross sections. The consequent lower nuclear effects may correspond to the Coulomb excitation effect assumed, although in a different manner, within the so-called “α-potential mystery” for the same optical–potential account of α-particle absorption and emission as well.

Recent high-precision measurements of angular distributions of α-particle elastic scattering [1] and cross sections of (α,γ) and (α,n) reactions [2, 3] on 144Sm make possible an extended analysis of the related α-particle optical model potential (OMP). It concerns the agreement between the experimental and statistical–model (SM) calculated cross sections for the 144Sm(α,n)147Gd reaction below the Coulomb barrier (B), with two recent potentials [4, 5], while the 144Sm(α,γ)148Gd reaction data cannot be reproduced with the same accuracy [3]. However, the latter reaction has been most important for the validation of the α-particle OMP since its first measurement with a singular energy precision [6]. Thus, it was the first one concerned regarding the ’α-potential mystery’ of an OMP that accounts for α-particle both absorption and emission [7]. A key issue in this respect has been the Coulomb excitation (CE) within the former process. Specific studies on 144Sm have also evaluated the sensitivity of SM results to various input parameters for these reactions [8, 9] as well as their significance [1–3].

Nevertheless, the knowledge of the α-particle OMP has greatly impacted nuclear astrophysics and fusion technology (e.g., [10, 11]). Thus, it motivated the analysis of the new data in addition to the earlier ones involved to obtain the OMP parameter set [4]. This potential was established and verified using no empirical rescaling factors of either γ or neutron widths within reaction data analysis but SM consistent parameters [11–17] found by analysis of other independent data [18]. Nevertheless, the uncertainties of these primary data may have effects on the calculated reaction cross sections that could be better assessed within the increased accuracy of the recently measured cross sections [2, 3].

Several steps were needed to set up the α-particle OMP of Ref. [4]. First, only the α-particle elastic scattering on nuclei with the mass number A∼100, at energies E<35 MeV, was analyzed above B [19]. Question marks related to the rest of SM parameters needed to calculate cross sections of reactions with either incident or emitted α-particles were thus avoided. Moreover, a double–folding model (DFM), with an explicit treatment of the exchange component, was initially used in a semi–microscopic approach. A dispersive correction to the microscopic DFM real potential was also considered, along with a phenomenological imaginary part that was energy–dependent. A full phenomenological analysis then focused on the same angular distributions, without changing the already determined imaginary part, provided the local OMP parameter sets corresponding to each data set. Lastly, a regional OMP with energy–dependent average mass and charge parameters was derived for further use in SM calculations.

Additional semi–microscopic and phenomenological analyses were carried out for the target nuclei with A between 50 and 120 and α-particle energies of 13–50 MeV [20]. However, an SM assessment of the cross sections of α-induced reactions below B, available for the same A range and energies below 12 MeV, was included. Similar consideration for the heavy nuclei (A between 121 and 197) also resulted in different results for the energy–dependence eventual change below B of the surface imaginary potential depth WD and the volume imaginary potential depth WV [21]. Thus, there were no issues in the extrapolation to lower energies of WV from analysis of the α-particle elastic scattering above B, while WD presents a distinct case.

The α-particle elastic scattering analysis, above B, provides a decrease of WD(E) with the energy increase. However, its extrapolation below B would contradict the strong increase in the number of open reaction channels of the compound–nucleus (CN). The related trend was well described by a minimum constant value until an energy limit E1, followed by a linear increase of WD(E) up to a second energy limit E2 corresponding to 0.9*B [20]. Only then, a decrease in WD with increasing energy is in order, until its cancellation at a few tens of MeV [21], along with the WV continuum increase. Both are considered by the parameters of the OMP, especially the more inelastic channels which are opened by the incident energy increase. These channels are open due to α-particle interactions with the target nucleus on the surface region, firstly, and then within its whole volume. Thus, the data analysis of the α-induced reactions determines the increasing side of WD while the elastic–scattering data constrain its decrease at higher energies.

Finally, the updated parameter set [4] for A≈45–209 took advantage of the new measured data, including their enlarged accuracy, as well as of an improvement for the well–deformed nuclei (152

The above review of the OMP [4] setting up is twofold. The energy limits E1 = 13.896 MeV and E2 = 16.863 MeV for 144Sm are are within the incident–energy range ∼10–20 MeV of the recent measurements [1–3]. However, all energies of the (α,γ) data are just below E1, whereas the (α,n) data are mainly above it as well as centered on E2. Therefore, the former data set constrains the parameters of the OMP [4] triggered by the reaction–data analysis, and the latter is equally related to the setting of the OMP based on the two types of data analysis.

It is noteworthy that, at the time, the former 144Sm(α,γ)148Gd data set [6] was the only one available below E1 for target nuclei with A ≥130. Based on this analysis, the constant WD of 4 MeV at energies

The SM analysis and the assessment of direct–interaction (DI) collective inelastic–scattering cross sections were recently carried out by using the same models and codes [25, 26] within a local approach [4, 27] and excitation energy grid with an equidistant binning ≥0.2 MeV. Therefore, only different or additional aspects are discussed hereafter.

Similar parameters of (i) back-shifted Fermi gas (BSFG) [28], (ii) OMP parameter sets [4, 29], and (iii) radiative strength functions (RSF) [30, 31] were used to account for the nuclear level density (NLD) and particle and γ-ray transmission coefficients, respectively. Particularly, the NLD and RSF consistent parameters were established or validated in advance with distinct data analysis.

The number and maximum excitation energy of the low-lying discrete levels [32] and level density parameters are given in Table 1 for the main SM reaction channels. They are followed by the data used for setting up the corresponding NLD parameters, such as the low-lying levels fitted along with, if known, the s-wave nucleon–resonance spacings

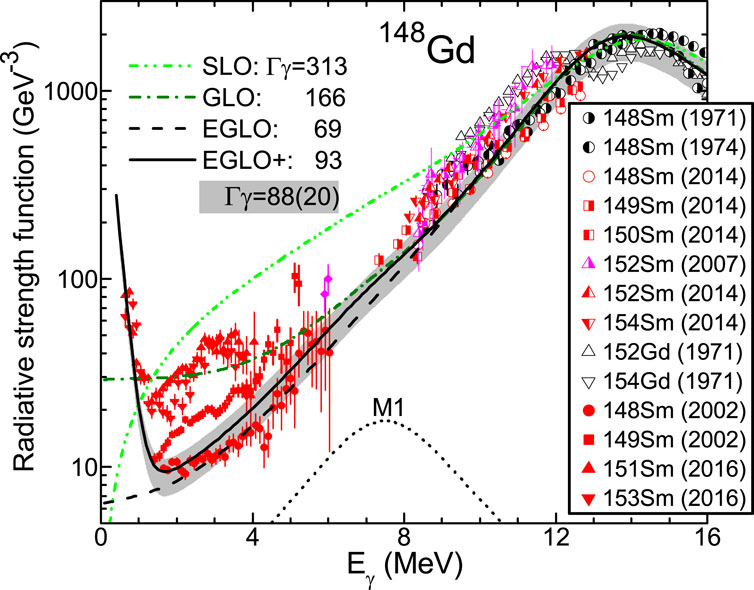

TABLE 1. Low-lying levels number Nd up to excitation energy

The smooth-curve method has been used for nuclei without resonance data [35]. Thus, an average of the fitted a-values for nearby nuclei [4] was employed to obtain only the Δ value by fitting the low-lying levels. Table 1 also shows the cumulative uncertainty of the NLD parameters corresponding to the incertitude of the above–mentioned data involved within their setting up. Larger uncertainties of the averaged a-values are due to the spreading of the results of

The transmission coefficients were obtained using the global OMPs of either Koning and Delaroche [29], for nucleons, or [4] for α-particles. Moreover, the same parameters provided the DI collective inelastic–scattering cross sections through the distorted-wave Born approximation (DWBA) method and the DWUCK4 code [26]. A more detailed discussion follows in Section 2.3.

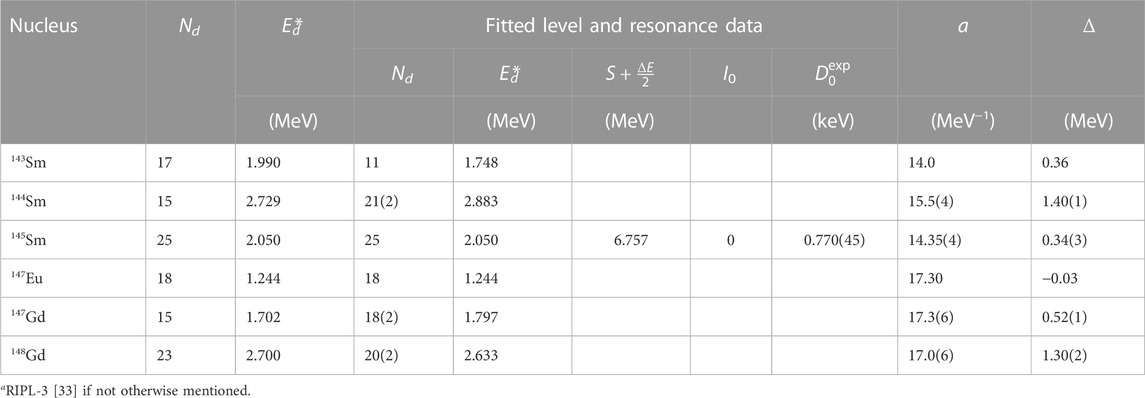

The γ-ray transmission coefficients were provided by the recently available widespread RSFs systematics [31, 36]. However, there is no related RSF analysis for the neutron–poor Gd isotopes similar to those in the rare-earth region for the 148,149,151,153Sm isotopes [30, 37]. The comparative survey of the RSF data [36] of lighter Sm and Gd isotopes shown in Figure 1 suggested an apparent mass–and charge–dependency. It may support a prediction for the compound nucleus 148Gd based on measured RSF data for 148,149Sm nuclei. Therefore, we employed the giant dipole resonance (GDR) parameters of Kawano et al. for 150Gd [31] within the former Lorentzian (SLO) [38], generalized Lorentzian (GLO) [39], and enhanced generalized Lorentzian (EGLO) [40] models for the electric-dipole RSF. Moreover, the SLO model and the additional M1 upbend parameters that were recently found to describe the RSF data for 151,153Sm nuclei [37] were used. A nuclear–temperature EGLO parameter Tf=0.4 MeV, which is between the values found for Sm and Gd isotopes (Table I of Ref. [4]), was considered appropriate.

FIGURE 1. Comparison of measured RSFs of 148,149,150,151,152,153,154Sm and 152,154Gd nuclei [36] and calculated sum of M1-radiation SLO model (short dotted) and either E1-radiation SLO (dash-dot-dotted), GLO (dash-dotted) models, or the sum of upbend M1 component and EGLO (solid) models, with the resonance parameters for 150Sm nucleus ([31], Table III) for 148Gd nucleus. The corresponding average s-wave radiation widths Γγ (in meV), deduced from systematics [33] as well as calculated with the above models, are also shown.

We obtained a suitable EGLO account of the RSF measured data of 148,149Sm nuclei [30, 36] as well as the averaged s-wave radiation widths Γγ [33]. The dependency of the Γγ(S), for the even-even nuclei [33], also provided an estimation of this width and its uncertainty for 148Gd nucleus as (88 ± 20) meV. Figure 1 shows an RSF uncertainty band corresponding to these Γγ estimated limits to match almost all data measured either above or below S. The effect of this uncertainty on the calculated reaction cross sections is also concerned hereinafter. Nevertheless, the SLO and GLO models resulted in different RSF energy dependencies below S, as well as larger Γγ–values well beyond the systematic uncertainty (Figure 1).

The α-particle OMP [4] was employed to get the DI collective inelastic scattering with the DWUCK4 code [26] using the corresponding deformation parameters of the first 2+ and 3− collective states [41, 42]. The DI cross-section was then subtracted from the σR to obtain the CN cross-section for further SM calculations.

A note should be added concerning the CE discussion given in Sec. II of Refs. [4, 13, 15]. Because the inelastic–scattering cross section could be strongly affected by the Coulomb component of the interaction between the projectile and target nucleus, we used a value COUEX = 1.0 in the DWUCK4 calculations [26]. Actually, a previous DWBA analysis pointed out the issue of the collective form factors corresponding to (i) either CE or nuclear excitation (NE) alone, as well as their coherent interference (NE+CE) (e.g., [43]), and (ii) integration radii Rmax of either 15 or 30 fm, which are typical to the short–range nuclear interactions [26] and the long-range Coulomb field, respectively [44]. The largest contributor to the CE cross sections were partial waves larger than those contributing to the optical model total–reaction cross section σR. Simultaneously, the assessment of α-particle DI inelastic scattering should include the effects of the CE+NE interference corresponding to an integration radius that is typical of the short–range nuclear interactions (∼15 fm).

We obtained α-particle DI inelastic–scattering cross sections up to ∼9% of σR for incident energies of ∼14 MeV. Above 20 MeV, these cross sections slightly decreased to 2% of σR. The corresponding decrease of σR was then considered within the SM analysis of various reaction channels.

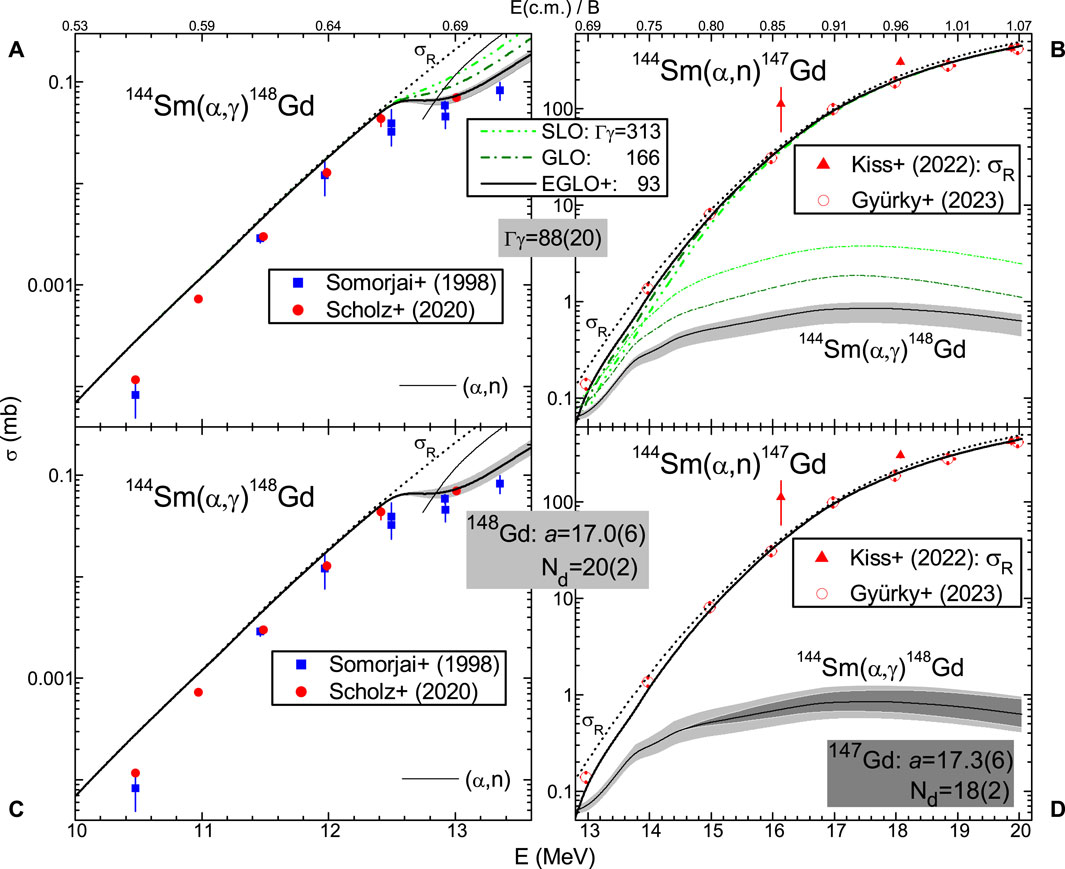

Figure 2 provides an initial comparison of the measured cross sections of the reactions (α,γ) [2, 6] and (α,n) [3] on 144Sm, and calculated results obtained with the α-particle OMP [4] and the above–mentioned model parameters and assumptions. It includes the calculated α-particle σR, to highlight the weight of each reaction channel at various energies.

FIGURE 2. Comparison of measured [1–3, 6] and calculated (α, γ) and (α, n) reaction (solid curves) as well as α-particle total–reaction cross sections (dotted curves), for the target nucleus 144Sm and α-particle OMP [4], vs. either α-particle laboratory energy (bottom) or ratio of center-of-mass energy to Coulomb barrier B [49] (top). The excitation functions calculated by using E1-radiative strength functions of the SLO (dash-dot-dotted), GLO (dash-dotted), and EGLO (solid curves) models are shown at once with the corresponding average s-wave radiation widths Γγ (in meV). The displayed uncertainty bands correspond to (A, B) the Γγ error bar deduced from systematics [33], and (C, D) the error bars of the level–density parameter a (Table 1) of the CN 148Gd (light–gray), and residual nucleus 147Gd (gray).

The recent (α,γ) measured data [2], which had higher accuracy than previous ones [6], are described within so small error bars only at incident energies above 12 MeV. Otherwise, there is an overestimation which increases with the energy lowering, until a factor of ∼2 around 10.5 MeV. This trend, at incident energies where the (α,γ) cross section equals σR, can be explained neither by the RSF option (Figure 2A) nor the incertitude of the NDL parameters given in Table 1 for the compound nucleus 148Gd (Figure 2C).

On the other hand, at energies where the α-capture becomes a minor reaction channel, the uncertainty band of the calculated cross section corresponding to the systematic Γγ [33] incertitude is similar to the error bar of the highest–energy measured data (Figure 2A). Moreover, a replacement of the EGLO strength function with the GLO and then SLO forms leads each time to additional overestimation of the same size.

A similar uncertainty band is related, at the same energies, to the incertitude of the NLD parameters for the compound nucleus 148Gd (Figure 2C). Another uncertainty band corresponds to NLD of the residual nucleus 147Gd at incident energies well above the (α, n) reaction threshold for the continuum population of this nucleus (Figure 2D). Altogether, below the incident energy of ∼12 MeV, no RSF and NLD effects may correspond to the increasing overestimation of the (α,γ) data.

The accurate most recently measured (α, n) cross sections [3] are well described within their small error bars (Figures 2B, D). Only the two lowest-energy points, at 13–14 MeV incident energies, are accounted for at the lowest limit of the experimental errors. However, an interplay of the (α,γ) and (α,n) cross sections for various RSF occurs solely at these energies. Thus, while the EGLO model provides lower cross sections for the former reaction, the reverse occurs with the usual SLO model. On the other hand, the uncertainty band of only ∼10% for (α, n) calculated cross sections at these energies, related to the systematic Γγ incertitude, is hardly visible in Figure 2B. Meanwhile, the results of the GLO and SLO models decrease by ∼17% and 36%, respectively.

This case provides a sound motivation for further study of the RSF modeling and competition between the capture and particle emission. At incident energies near 13 MeV, even lower RSF values would provide a better data account for both the (α,γ) and (α,n) calculated cross sections. However, a further decrease of the RSF for the compound nucleus 148Gd is less probably on the basis of the RSF data available for neighboring nuclei (Figure 1).

The comparison of the σR values which were deduced through the elastic–scattering analysis at incident energies between 16 and 20 MeV [1] and the calculated results using the OMP [4] shows an agreement at the highest–energy point but a significant underestimation at the lower energies (Figure 2B). A previous note [1] on this measured and calculated σR difference concerned the fact that the setting up of the OMP [4] included the fit of a similar angular distribution measured at the same energy of 20 MeV. Nevertheless, the present suitable account of the more accurate (α, n) cross sections at these incident energies, which amount to 97%–90%σR, supports additionally the α-particle OMP [4]. Moreover, a suitable account of elastic–scattering angular distribution by the same OMP was proven for another semi–magic nucleus 140Ce at a comparable lower energy of 15 MeV [Figure 8(d) of Ref. [4]].

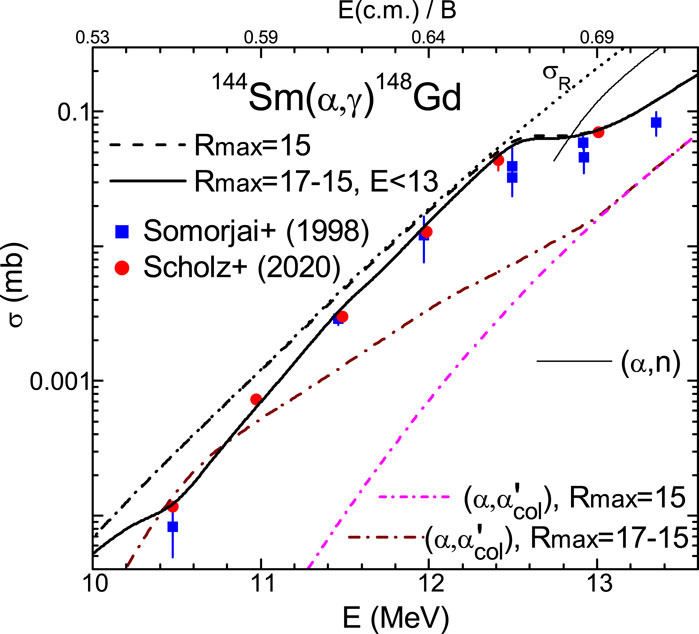

The faster decrease of the (α,γ) cross sections below ∼12 MeV could be associated only with the above–mentioned weighting of the α-particle collective inelastic–scattering cross sections. Their maximum around 9% of σR at incident energies near 14 MeV, followed by a decrease to 2% above 20 MeV, is in line with the agreement of the measured and calculated (α,γ) and (α,n) cross sections at these energies. However, following the dependency of the DWBA outcome on the integration radius Rmax, we found that the newly measured (α,γ) cross sections, at the incident energies decreasing from 12 to 10.5 MeV, correspond to DI inelastic–scattering cross sections increased by the use of Rmax values rising from 15.5 to 17 fm.

Taking into account the agreement already provided by the use of the value Rmax=15 fm at the energies ≥13 MeV, it results that a simple linear dependency of the form Rmax(fm)=25.4–0.8E is leading to suitable collective DI inelastic–scattering and (α, γ) reaction cross sections also at the incident energies between 10.5 and 13 MeV (Figure 3). Thus, the excitation function of the (α, γ) reaction which formerly overlapped σR below ∼12 MeV (Figures 2A, C), has now a distinct trend. However, while Rmax=17 fm has currently been used down from the energy of 10.5 MeV, its form below the energy range of the new (α, γ) reaction data [3] should be clarified by further analysis.

FIGURE 3. As Figure 2A but for α-particle DI inelastic–scattering cross sections obtained by using an integration radius constant Rmax=15 fm (short dash-dotted curve) as well as increasing to 17 fm for the incident energy decrease from 13 to 10.5 MeV (dash-dotted curve), and the corresponding (α,γ) reaction cross sections (dashed and thick solid curves, respectively).

The increase of the integration radius beyond the typical 15 fm value to the short–range nuclear interactions, with the decrease of the α-particle energy, may correspond to nuclear effects decreasing [43]. Therefore, it could be a Coulomb excitation effect, as was assumed although in a different manner [7]. Nevertheless, the above Rmax(E) dependency is a form used to describe only the recently measured (α,γ) data at α-particle energies above 10.5 MeV [2].

An analysis of the latest high–precision measured cross sections of (α,γ) and (α,n) reactions on 144Sm [2, 3], below the Coulomb barrier, is carried out using a consistent parameter set of the statistical model. Therefore, empirical rescaling factors of either γ or neutron widths are no longer involved. Moreover, in addition to previous studies on SM sensitivities [1–3, 8, 9], particular attention was paid to the uncertainties of the calculated cross sections that correspond to the accuracy of the primary data used to set up the consistent input parameters. The experimental and calculated cross sections of 144Sm(α,n)147Gd and 144Sm(α,γ)148Gd reactions agreed only at energies above 12 MeV. This leaves open the question of suitable parameter or model assumptions.

First, we considered that the calculated cross–section accuracy cannot exceed that of the model parameters and, consequently, of the data used for their setting. However, we found minor nuclear–level density effects within SM analysis, with respect to the uncertainty of either the average level–density parameter a values, based on both the spreading and the error bars of the fitted

A similar case was that of the RSF impact. The RSF data as well as the average s-wave radiation widths Γγ deduced from systematics [33] were considered in the absence of the corresponding data for the compound nucleus 148Gd. An interplay of the calculated cross sections of (α,γ) and (α,n) reaction was found near the threshold of the (α,n) reaction. Thus, while the EGLO model provided lower cross sections for the (α,γ) reaction, the reverse corresponds to the usual SLO model. This case is significant owing to the scarce attention paid to the RSF assessment within (α,γ) reaction studies, leading to a distinct conclusion on the other important SM parameter which is the α-particle optical potential. For the sake of completeness, one may note the claimed need for OMPs correction factors [45, 46], at once with no proof of the accompanying RSF. It thus fully explains the disagreement with the previous conclusions for the same reactions [4, 13–15, 20, 47], which followed a former RSF detailed analysis.

Because we found no RSF and NLD effects at the origin of the (α,γ) data overestimation, which is increasing below the incident energy of ∼12 MeV, further consideration was given to the DWBA analysis of the α-particle direct inelastic scattering. The faster decrease of the (α,γ) reaction cross sections below ∼12 MeV is described by means of an increase of the corresponding integration radius at lower α-particle energies, from the typical value of 15 fm (corresponding to the short–range nuclear interactions) at the incident energy of 13 MeV, to 17 fm at 10.5 MeV. This increase of the integration radius with the decrease of the α-particle energy may correspond to nuclear effects decreasing. Therefore, it could be a Coulomb excitation effect, as was assumed although in a different manner [7], within the so-called “α-potential mystery” for the same optical–potential account of α-particle absorption and emission as well. However, the integration–radius form below the energy range of the measured cross sections of the (α,γ) reaction [3] should be clarified by further analysis. This is important for both nuclear astrophysics and fusion technology.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This work has been partly supported by the Executive Unit for the Financing of Higher Education, Research, Development and Innovation (UEFISCDI) (Project No. PN-III-ID-PCE-2021-1260) and carried out within the framework of the EUROfusion Consortium, funded by the European Union via the Euratom Research and Training Programme (Grant Agreement No. 101052200—EUROfusion). Views and opinions expressed are, however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

The support by the Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) Data Bank, Paris, in providing their services hosting the progress meetings, is gratefully acknowledged.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor YX declared a shared affiliation with the author(s) at the time of review

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Kiss GG, Mohr P, Gyürky G, Szücs T, Csedreki L, Halász Z, et al. High-precision 144Sm(α,α)144Sm scattering at low energies and the rate of the 144Sm(α,γ)148Gd reaction. Phys Rev C (2022) 106:015802. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.106.015802

2. Scholz P, Wilsenach H, Becker HW, Blazhev A, Heim F, Foteinou V, et al. New measurement of the 144Sm(α,γ)148Gd reaction rate for the γ process. Phys Rev C (2020) 102:045811. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.102.045811

3. Gyürky G, Mohr P, Angyal A, Halász Z, Kiss GG, Mátyus Z, et al. Cross section measurement of the 144Sm(α,n)147Gd reaction for studying the α-nucleus optical potential at astrophysical energies. Phys Rev C (2023) 107:025803. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.107.025803

4. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M, Mănăilescu C. Further explorations of the α-particle optical model potential at low energies for the mass range A ≈ 45–209. Phys Rev C (2014) 90:044612. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.90.044612

5. Mohr P, Fülöp Z, Gyürky G, Kiss GG, Szücs T. Successful prediction of total α-induced reaction cross sections at astrophysically relevant sub-coulomb energies using a novel approach. Phys Rev Lett (2020) 124:252701. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.252701

6. Somorjai E, Fülöp Z, Kiss A, Rolfs C, Trautvetter H, Greife U, et al. Experimental cross section of 144Sm(α,γ)148Gd and implications for the p-process. Astron Astrophysics (1998) 333:1112–6.

7. Rauscher T. Solution of the α-potential mystery in the γ process and its impact on the Nd/Sm ratio in meteorites. Phys Rev Lett (2013) 111:061104. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.061104

8. Rauscher T. The path to improved reaction rates for astrophysics. Int J Mod Phys E (2011) 20:1071–169. doi:10.1142/s021830131101840x

9. Rauscher T. Sensitivity of astrophysical reaction rates to nuclear uncertainties. Astrophysical J Suppl Ser (2012) 201:26. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/201/2/26

10. Fischer U, Avrigeanu M, Avrigeanu V, Cabellos O, Dzysiuk N, Koning A, et al. Nuclear data for fusion technology - the European approach. EPJ Web Conf (2017) 146:09003. doi:10.1051/epjconf/201714609003

11. Avrigeanu M, Avrigeanu V. Consistent optical potential for incident and emitted low-energy α particles. III. Nonstatistical processes induced by neutrons on Zr, Nb, and Mo nuclei. Phys Rev C (2023) 107:034613. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.107.034613

12. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M. Consistent optical potential for incident and emitted low-energy α particles. Phys Rev C (2015) 91:064611. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.91.064611

13. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M. Analysis of uncertainties in α-particle optical-potential assessment below the Coulomb barrier. Phys Rev C (2016) 94:024621. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.94.024621

14. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M. Consistent optical potential for incident and emitted low-energy α particles. II. α emission in fast-neutron-induced reactions on Zr isotopes. Phys Rev C (2017) 96:044610. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.96.044610

15. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M. Role of consistent parameter sets in an assessment of the α-particle optical potential below the Coulomb barrier. Phys Rev C (2019) 99:044613. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.99.044613

16. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M. Validation of an optical potential for incident and emitted low-energy α-particles in the A ≈ 60 mass range. Eur Phys J A (2021) 57:54. doi:10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00336-0

17. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M. Validation of an optical potential for incident and emitted low-energy α-particles in the A ≈ 60 mass range. II. Neutron–induced reactions on Ni isotopes. Eur Phys J A (2022) 58:189. doi:10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00831-6

18. Arthur ED. Parameter determination and application to nuclear model calculations of neutron-induced reactions on yttrium and zirconium isotopes. Nucl Sci Eng (1980) 76:137–47. doi:10.13182/NSE80-A19446

19. Avrigeanu M, von Oertzen W, Plompen AJM, Avrigeanu V. Optical model potentials for α-particles scattering around the Coulomb barrier on A ∼100 nuclei. Nucl Phys A (2003) 723:104–26. doi:10.1016/S0375-9474(03)01159-X

20. Avrigeanu M, Obreja AC, Roman FL, Avrigeanu V, von Oertzen W. Complementary optical-potential analysis of α-particle elastic scattering and induced reactions at low energies. At Data Nucl Data Tables (2009) 95:501–32. doi:10.1016/j.adt.2009.02.001

21. Avrigeanu M, Avrigeanu V. α-particle nuclear surface absorption below the Coulomb barrier in heavy nuclei. Phys Rev C (2010) 82:014606. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.82.014606

22. Kiss GG, Mohr P, Fülöp Z, Rauscher T, Gyürky G, Szücs T, et al. High precision 113In(α, α)113In elastic scattering at energies near the Coulomb barrier for the astrophysical γ process. Phys Rev C (2013) 88:045804. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.88.045804

23. Ornelas A, Kiss G, Mohr P, Galaviz D, Fülöp Z, Gyürky G, et al. The 106Cd(α,α)106Cd elastic scattering in a wide energy range for γ process studies. Nucl Phys A (2015) 940:194–209. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2015.04.008

24. Kiss GG, Szücs T, Mohr P, Török Z, Huszánk R, Gyürky G, et al. α-induced reactions on 115In: cross section measurements and statistical model analysis. Phys Rev C (2018) 97:055803. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.97.055803

25. Avrigeanu M, Avrigeanu V. Recent improvements of the STAPRE-H95 preequilibrium and statistical model code. Tech rep., Inst Phys Nucl Eng (1995). Available at: http://www.oecd-nea.org/tools/abstract/detail/iaea0971/.

26. [Dataset] Kunz PD. DWUCK4 user manual (1984). Available at: http://www.oecd-nea.org/tools/abstract/detail/nesc9872/.

27. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M. Consistent assessment of neutron-induced activation of 93Nb. Front Phys (2023) 11. doi:10.3389/fphy.2023.1142436

28. Vonach H, Uhl M, Strohmaier B, Smith BW, Bilpuch EG, Mitchell GE. Comparison of average s-wave resonance spacings from proton and neutron resonances. Phys Rev C (1988) 38:2541–9. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.38.2541

29. Koning AJ, Delaroche JP. Local and global nucleon optical models from 1 keV to 200 MeV. Nucl Phys A (2003) 713:231–310. doi:10.1016/S0375-9474(02)01321-0

30. UiO/OCL. Level densities and gamma-ray strength functions (2022). Available at: http://ocl.uio.no/compilation (Accessed October 15, 2022).

31. Kawano T, Cho Y, Dimitriou P, Filipescu D, Iwamoto N, Plujko V, et al. IAEA photonuclear data library 2019. Nucl Data Sheets (2020) 163:109–62. doi:10.1016/j.nds.2019.12.002

32. IAEA. Evaluated nuclear structure data file (ENSDF) (2022). Available at: https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/ensdf/ (Accessed October 15, 2022).

33. Capote R, Herman M, Obložinský P, Young PG, Goriely S, Belgya T, et al. RIPL – reference input parameter library for calculation of nuclear reactions and nuclear data evaluations. Nucl Data Sheets (2009) 110:3107–214. doi:10.1016/j.nds.2009.10.004

34. Reffo G. Average neutron resonance parameters and other data collected in Beijing (1998). Available at: https://www-nds.iaea.org/ripl/resonances/other_files/beijing_dat.htm (Accessed October 15 1998).

35. Johnson CH. Statistical model radiation widths for 75 < A < 130 and the enhancement of P-wave neutron capture for A ≈ 90. Phys Rev C (1977) 16:2238–48. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.16.2238

36. Goriely S, Dimitriou P, Wiedeking M, Belgya T, Firestone R, Kopecky J, et al. Reference database for photon strength functions. Eur Phys J A (2019) 55:172. doi:10.1140/epja/i2019-12840-1

37. Simon A, Guttormsen M, Larsen AC, Beausang CW, Humby P, Harke JT, et al. First observation of low-energy γ-ray enhancement in the rare-earth region. Phys Rev C (2016) 93:034303. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.93.034303

38. Axel P. Electric dipole ground-state transition width strength function and 7-mev photon interactions. Phys Rev (1962) 126:671–83. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.126.671

39. Kopecky J, Uhl M. Test of gamma-ray strength functions in nuclear reaction model calculations. Phys Rev C (1990) 41:1941–55. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.41.1941

40. Kopecky J, Uhl M, Chrien RE. Radiative strength in the compound nucleus 157Gd. Phys Rev C (1993) 47:312–22. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.47.312

41. Raman S, Nestor CW, Tikkanen P. Transition probability from the ground to the first-excited 2+ state of even–even nuclides. At Data Nucl Data Tables (2001) 78:1–128. doi:10.1006/adnd.2001.0858

42. Kibédi T, Spear RH. Reduced electric-octupole transition probabilities, B(E3;01+→31−)—an update. At Data Nucl Data Tables (2002) 80:35–82. doi:10.1006/adnd.2001.0871

43. Bassel RH, Satchler GR, Drisko RM, Rost E. Analysis of the inelastic scattering of alpha particles. I. Phys Rev (1962) 128:2693–707. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.128.2693

44. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M, Mănăilescu C. Coulomb excitation effects on alpha-particle optical potential below the Coulomb barrier (2016). Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1605.05455v1.pdf.doi:10.48550/arXiv.1605.05455

45. Le NN, Hung NQ. Improved version of the α-nucleus optical model potential for reactions relevant to the γ process. Phys Rev C (2022) 105:014602. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.105.014602

46. Basak D, Basu C. Determination of α-optical potential for reactions with p-nuclei from the study of (α, n) reactions in the astrophysically relevant energy region. Eur Phys J A (2022) 58:150. doi:10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00798-4

47. Avrigeanu V, Avrigeanu M. Analysis of α-induced reactions on 151Eu below the coulomb barrier. Phys Rev C (2011) 83:017601. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.83.017601

48. Avrigeanu V, Glodariu T, Plompen AJM, Weigmann H. On consistent description of nuclear level density. J Nucl Sci Tech (2002) 39:746–9. doi:10.1080/00223131.2002.10875205

Keywords: nuclear reactions, cross sections, nuclear models, optical potential, nuclear level density, model calculation uncertainty bands

Citation: Avrigeanu V and Avrigeanu M (2023) Constrained model assumptions using recent data of α-particle reactions on 144Sm. Front. Phys. 11:1247311. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2023.1247311

Received: 25 June 2023; Accepted: 10 October 2023;

Published: 24 October 2023.

Edited by:

Yi Xu, Horia Hulubei National Institute for Research and Development in Physics and Nuclear Engineering (IFIN-HH), RomaniaReviewed by:

Francesco Giovanni Celiberto, Bruno Kessler Foundation (FBK), ItalyCopyright © 2023 Avrigeanu and Avrigeanu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vlad Avrigeanu, dmxhZC5hdnJpZ2VhbnVAbmlwbmUucm8=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.