- 1College of Electronics and Information Engineering, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

- 2Guangdong Key Laboratory of Intelligent Information Processing, Shenzhen, China

- 3School of Artificial Intelligence, Shenzhen Polytechnic, Shenzhen, China

- 4Institute of Applied Artificial Intelligence of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, Shenzhen Polytechnic, Shenzhen, China

Oblivious transfer (OT) is one of the keystones of secure multi-party computation. It is generally believed that unconditionally secure OT is impossible. In this article, we propose a practical and secure quantum all-or-nothing oblivious transfer protocol based on the quantum one-way function. The protocol is built upon a quantum public-key encryption construction, and its security relies on the no-cloning theorem and no-communication theorem. Practical security is reflected in limitations on non-demolition measurements.

1 Introduction

Rabin pioneered the concept of oblivious transfer in 1981 [1]. In Rabin’s OT (also called all-or-nothing OT) protocol, Alice sends a message m to Bob, and Bob receives the message m with a probability of 1/2. Toward the end of the protocol interaction, Alice does not know whether Bob received the message m while Bob does. Later in 1985, Even et al. [2] proposed a more practical OT called 1-out-of-2 oblivious transfer, which can be used to implement a wide variety of protocols [2, 3]. In this version of OT, Alice has a message pair (m0, m1), Bob makes a choice, and one of the messages is chosen. At the end of the protocol, Bob is allowed to retrieve one message from Alice’s message pair corresponding to his choice without knowing anything about the other message, while Alice is unaware of Bob’s choice. However, Crépeau demonstrated that the two kinds of oblivious transfer protocols are similar when the messages are single bits, meaning that one may be created from the other and vice versa [4]. Furthermore, one can build a 1-out-of-2 oblivious transfer protocol that transmits bit-string messages from a 1-out-of-2 oblivious transfer protocol for single bits [5–7].

The versatility of these protocol settings motivates a wider study on the power of secure two-party computation. Classical OT relies on computational hardness assumptions. Typically, these assumptions fall into two categories: general hardness assumptions such as the existence of one-way functions (OWFs) and specific hardness assumptions such as factoring integers, discrete logarithms, and lattice-based problems, also known as trapdoor one-way functions. However, Shor’s algorithm [8] can be used to solve difficult mathematical problems such as integer factorization, discrete logarithms, and elliptic curve discrete logarithms, posing a risk that the security of trapdoor one-way functions generated by certain existing number-theoretic-based cryptography is threatened. Moreover, OT protocols that rely only on the assumption of the existence of one-way functions are resistant to quantum attacks.

The principles of quantum mechanics can be used to design more secure cryptographic protocols. In 1983, Wiesner proposed that the uncertainty principle [9] could be used in cryptography [10]. In 1984, Bennett and Brassard used the quantum no-cloning theorem to implement basic cryptographic protocols, proposing the first unconditionally secure quantum key distribution protocol, BB84 [11, 12]. However, Mayers [13], Lo, and Chau [14, 15] proved that all previously proposed quantum bit commitment (QBC) protocols and quantum oblivious transfer (QOT) protocols are not unconditionally secure. Because the sender Alice can almost always cheat successfully by using an Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR)-type attack and delaying the measurement until disclosing her commitment. Moreover, OT generally requires a secure BC, so unconditionally secure OT is also impossible. The no-go theorem (based on the Hughston–Jozsa–Wootters (HJW) theorem [16, 17]) was proposed, resulting in the non-existence of unconditionally secure BC and unconditionally secure OT being widely accepted.

Following the classical equivalence [4] between the two flavors of oblivious transfer, one might conclude that the impossibility of having an unconditionally secure 1-out-of-2 oblivious transfer would imply the same for oblivious transfer. However, the laws of quantum physics allow for a greater range of scenarios, potentially jeopardizing classical reduction theories. One must run numerous oblivious transfer protocols as black boxes to create the 1-out-of-2 oblivious transfer, and this raises the risk of so-called coherent attacks (joint quantum measurements on several black boxes). Thus, having a secure quantum all-or-nothing oblivious transfer protocol does not necessarily mean that it is possible to construct a secure 1-out-of-2 oblivious transfer. We can implement all-or-nothing OT multi-party computation without using the BC protocol. As a consequence, no matter how high the security level our all-or-nothing OT has, this fact alone is not in contradiction with the Lo–Chau–Mayers no-go theorem. The alternative, ensuring practical security of such protocols, is to consider noisy or bounded memories [18–20]. Recently, a (quantum) computationally secure version of the oblivious transfer protocol was presented in [21].

In 2017, João et al. proposed a practical all-or-nothing QOT [22] based on single-qubit rotations in which the authors improve the public-key encryption scheme. However, there are two issues in the scheme that need to be addressed, which are also the main concerns of this article: 1) if all the secret keys si are indeed chosen uniformly at random, then some of them will be close to 0 or π/2, and this part of the measurement will always be correct. Therefore, the authors added the step of checking whether s is likely to be a possible output of a random process to avoid Alice cheating. Nevertheless, when Bob chooses the wrong direction of rotation, the state of each qubit becomes

The one-way function is one of the most fundamental cryptographic primitives, as it can be used as a component of other, more complex cryptographic protocols. Recently, two independent works [23, 24] proved that secure one-way functions imply secure computation in a quantum world. They showed that quantum oblivious transfer can be obtained from the black-box use of any statistically binding, quantum computationally hidden commitment. Additionally, they pointed out that such commitments can be constructed by quantum-secure one-way functions (classic one-way functions that can be resistant to quantum attacks). Although exhaustive search is the only way to attack classical ideal secure one-way functions, cryptographic protocols based on classical secure one-way functions require the assumption that the attacker’s computing power is limited. If we can design one-way functions based on physical laws, i.e., quantum mechanics principles, then we can potentially obtain secure quantum one-way functions. Thus, it is possible for us to construct secure OTs. In view of this, we will focus on the design of specific quantum one-way functions (QOWFs). Following that, we build more complex quantum oblivious transfer protocols based on the one-way function.

In this article, we study the design of quantum one-way functions as well as introduce and enhance a quantum public-key encryption (qPKE) construction. Then, we design a practical secure quantum all-or-nothing OT protocol based on a specific QOWF. The soundness of the protocol relies on secure communication by applying qPKE. The security of the protocol can be reduced to one-wayness of the quantum one-way function, the no-cloning theorem, and the no-communication theorem. It is worth mentioning that the application of the hash function (digest algorithm) and the idea of secret sharing ensures that honest Bob can check whether he has obtained the message and dishonest Bob gets nothing about the message. More specifically, the distributor divides a secret into t-shared units, such that any of the t-shared units can be combined to reconstruct the secret, but no information about the secret is available to any of the t − 1-shared units. The t-shared units are transferred to Bob in cipher, and each shared unit corresponds to exactly one check unit, attempting to necessarily check and destroy the shared units.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: first, in Section 2, we discuss the definition of quantum one-way functions and prove the security of a rotation-based quantum one-way function. Then, in Section 3, we introduce and improve the quantum public-key encryption system based on the classical-to-quantum one-way function. In Section 4, we describe in detail the construction of the all-or-nothing oblivious transfer protocol based on the qPKE. In Section 5, we analyze the proposed OT protocol and show that the security of the new scheme can be reduced to the one-wayness of the quantum one-way function. Finally, we give a summary in Section 6.

2 Quantum one-way functions

A function f: {0,1}* → {0,1}* is one-way if f can be computed by a polynomial-time algorithm, but any polynomial-time randomized algorithm F that attempts to compute a pseudo-inverse for f succeeds with negligible probability. That is, a one-way function is a function that is easy to compute on every input but hard to invert given the image of random input. By definition, the function must be “hard to invert” in the average-case sense, rather than the worst-case sense [25]. The existence of such one-way functions is still an open conjecture. In fact, their existence would prove that the complexity classes P and NP are not equal. The converse is not known to be true, i.e., the existence of proof that P ≠ NP would not directly imply the existence of one-way functions.

Generally, a one-way function designed based on quantum mechanical principles (such as the no-cloning theorem [9]) is called a quantum one-way function. One-wayness needs to be satisfied, i.e., the function can effectively (polynomial time) get the output according to the input, while the input cannot be obtained according to the output. The concept of classical-to-quantum one-way function (CQ-OWF) was first proposed by Gottesman and Chuang [26], who showed that such a function can be obtained by mapping classical bit strings to quantum states of a collection of qubits, and designed a quantum signature scheme based on it, where the classical-to-quantum one-way function is defined as a function that can be easily solved by quantum algorithms but cannot be inverted by any polynomial-time quantum algorithm [26]. That is, we can obtain a natural generalized version of the classical one-way function for quantum one-way functions by extending the probabilistic polynomial-time Turing machine to quantum algorithms.

Definition 1. (Quantum one-way function). Let

be a classical-to-quantum function that maps n bits of input to m qubits of output, where

is a 2m-dimensional Hilbert space made up of m copies of a single qubit space

Deterministic: the same input always gives the same output.

Easy to compute: for any input x, one can get the output |f(x)⟩ in polynomial time.

Hard to invert: given |f(x)⟩, it is impossible to invert x by virtue of the fundamental quantum information theory.

The input and output of a classical one-way function involve only classical bits, and given a pair (input, output), one can efficiently verify whether the output is generated by f according to the input. However, for quantum one-way functions, because the input and output involve quantum states, it is not always the case that we can verify the pair (input, output) effectively. Furthermore, given two outputs |f(x)⟩ and |f(x′)⟩, we are not able to definitively determine whether they are equal or not. This involves the comparison of quantum states, such as the swap-test, and the result of the test is probabilistic. If the states are the same, the swap-test is always passed, but if they are different, the swap-test is sometimes failed.Nikolopoulos [27] constructed a practical CQ-OWF using single-qubit rotations, explored the one-wayness of functions mapping integers to single quantum bit states, and proposed a quantum public-key cryptographic theoretical framework based on it, which is provably secure even against powerful quantum eavesdropping strategies. The scheme proposed in this article will also make use of this cryptosystem. To have a clearer understanding of the characteristics of this CQ-OWF, we re-elaborate this function in formal language, define its constituent elements as single-qubit OWFs, and give rigorous proof that this function satisfies one-wayness under the constraint of the no-cloning theorem.

2.1 Single-qubit OWF

The single-qubit OWF can be defined as

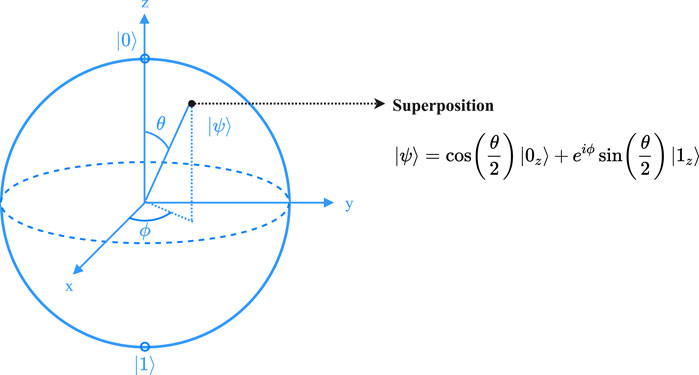

where 0 ≤ θ < 2π, ϕ = 0, is shown in Figure 1. Hence, unlike the classical bit, which can store a discrete variable taking only two real values (that is “0” and “1”), a qubit may represent a continuum of states on the x − z plane. Introducing the rotation operator about the y axis,

The input of the proposed single-qubit OWF is a random integer

However, in quantum public-key encryption, we use a one-way function with multiple integers input and multiple qubits output, so we define the CQ-OWF based on the single-qubit OWF as follows: consider two sets,

Theorem 1. The function denoted as

Deterministic: the same input always results in the same output.

Easy to compute: for any input x = {n, s}, one can get the output Fcq(x) in polynomial time.

Hard to invert: given

Proof. As follows, we first prove the one-wayness of the single-qubit OWF and then the one-wayness of the CQ-OWF.

2.2 One-wayness of the single-qubit OWF

To further illustrate the two expressions “easy to compute” and “hard to invert,” a quantum system initially prepared in a state of

It is common knowledge that the mapping

Inversion of the map

Hence, we see that for a given n ≫ 1, the map

2.3 One-wayness of the CQ-OWF

In general, there will always exist a family of quantum circuits

3 Quantum public-key encryption

In this section, we will discuss and improve the quantum public-key encryption construction proposed by Nikolopoulo [27], which has been proven to be secure. Based on the CQ-OWF mentioned in Section 3, when it comes to two consecutive rotations, the map

3.1 Stage 1—Key generation

Choose a random integer string s of length k, i.e.,

3.2 Stage 2—Encryption

Assume a sender wants to transfer a k-bit string m ≜ m1, m2, …, mk, with

(1) Obtain authentic public key e.

(2) When encrypting the jth bit of message, say mj, by applying the rotation

(3) Now that, we generate the quantum ciphertext (or else cipher state) that is the new state of the k qubits, i.e.,

3.3 Stage 3—Decryption

To recover the plaintext m from the cipher state

(1) Undo initial rotations, i.e., to apply

(2) Measure each qubit of the cipher state on the basis of

In the introduction to quantum public-key cryptography [27], only one encryption method is included, which is

In Section 3.2, we would like to analyze the encryption encoding method

When b = 1, there is

When b = 1, there is

In contrast, encoding different binary bits with the same encoding method, the cipher states

In Section 3.3, we would like to point out that the aforementioned two steps are basically equivalent to a von Neumann measurement, which projects the jth qubit onto the basis

where

where

When b = 1, there is

We can see that the quantum state after undoing the original rotation will only be in one of the four most common states

In summary, the improvement version, which does not change the original features of qPKE construction, still guarantees secure communication. To be compatible with the proposed oblivious transfer scheme, new encryption has been added to ensure that Bob cannot distinguish between the two encryption methods. In addition, the inherent property of qPKE is not broken, i.e., the message can always be correctly decrypted by following the correct steps. Lastly, we have agreed on only two bases, computational and Hadamard, to ensure that the protocol is oblivious.

Notice that, unlike the classical public keys that can be reused unlimited times, in the qPKE construction, the same public key e can also be reused, but it cannot be reused unlimited times. The public and secret keys need to be replaced after the security factor is exceeded, i.e., the upper bound needs to be bounded as follows: I(x, d) ≤ kN. When N copies of the public key circulate simultaneously, the mutual information between Eve and the key I(x, d) increases, and the confidentiality of the secret key is always guaranteed if

4 New quantum all-or-nothing oblivious transfer

In this section, we will design a secure all-or-nothing oblivious transfer protocol based on the aforementioned CQ-OWF as well as qPKE. Moreover, the hash function is applied in this scheme, along with the idea of secret sharing.

A hash function creates a digest (a string that is shorter) of a message in such a way that 1) the probability of generating at random strings with the same hash value is negligible; and 2) the hash values are distributed almost uniformly over the set of all possible digests. A digest algorithm (hash function) is a method used to prevent a message from being altered privately, and Bob’s choice of the wrong decryption method is considered a private alteration of the message. Therefore, Bob can verify whether the message was obtained or not after the opening phase. In the proposed scheme, the proposed hash function to be used to generate the digest is: Consider dividing a random key r into t successive blocks of bits

Shamir’s secret sharing, formulated by Adi Shamir, is one of the first secret-sharing schemes in cryptography. It is based on polynomial interpolation over finite fields [29]. The basic idea is that the distributor divides a secret into n-shared units by a polynomial, such that any of the t-shared units can be combined to reconstruct the secret, but no information about the secret is available to any of the t − 1-shared units. As mentioned previously, consider dividing the random key r into t successive units of bits

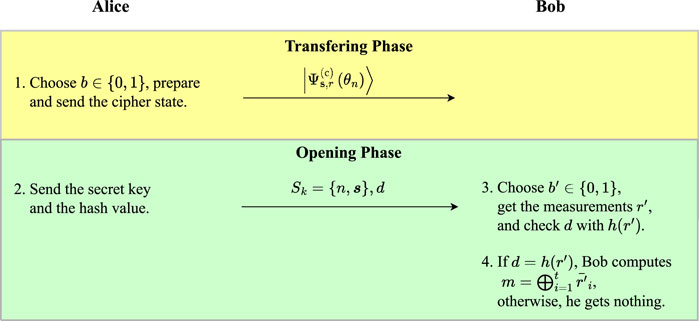

The framework of the proposed all-or-nothing OT protocol is shown in Figure 2. The detailed steps are described as follows:

Notations:

Security parameters:

Secret key: s = (s1, s2, …, skt), where each si ∈ {0,1}n;

Random key:

Hash function: h: {0,1}kt → {0,1}t;

Message to transfer: m = m1m2…mk.

Transferring phase:

(1) Alice uniformly at random takes any t − 1 random numbers

(2) After coding, she sends the result,

Opening phase:

(3) Alice sends to Bob the secret key as

(4) Bob applies

(5) Bob chooses uniformly at random b′ ∈ {0, 1} and measures each qubit of the cipher state on the basis of

(6) Let r′ be the random key that Bob recovers. He checks if d = h(r′). If that is the case, then Bob is almost sure that r′ = r; otherwise, he knows that r′ is not the correct random key. Finally, if r′ = r, dividing the random key r′ into t successive units of bits

This ends the proposed protocol.

5 Security analysis and discussion

In the proposed protocol, Bob’s main goal is to recover plaintext information from the cipher state, a goal that seems too ambitious to achieve under the quantum no-cloning theorem, and he may use different methods to try to compromise the security of the protocol. Alice’s main goal is to know whether Bob received the correct message or not. As long as one of these two goals is accomplished, the OT protocol is considered invalid. The security of the proposed OT protocol is then examined. All-or-nothing OT must fulfill the following four requirements (the first expresses correctness, while the next three ensure the security of the protocol):

(1) Soundness: if Bob and Alice are both honest, there is a 1/2 probability that Bob will get the correct message m. Bob is aware of whether he received the correct message or not, but Alice is not.

(2) Concealing: Bob cannot learn the message Alice intended to transfer before the opening phase if Alice is honest.

(3) Probabilistic transfer: after the opening phase, Bob is unable to learn the message in more than 50% of instances.

(4) Oblivious: if Bob is honest, Alice can only guess with a probability of 1/2 as to whether Bob received the message.

Definition 2. when a function f(x), for each polynomial function P(x), has the following equation held,

5.1 Soundness

In the following paragraphs, we prove the soundness of the proposed protocol: if both Alice and Bob are honest, then with a probability of 1/2 + ϵ(k), Bob will get the correct message, where ϵ(k) is a negligible function of the size of the message m = m1m2…mk. Bob is aware of whether he received the correct message or not, but Alice is not. As mentioned previously, the message can be recovered using the random key, and the information Bob receives about the random key consists of two parts: one belonging to the cipher state sent by Alice, and the other belonging to its hash value. It has shown that, by the nature of the digest algorithm, the hash function does not help Bob recover the random key r. This is because the hash is obtained in a lossy and irreversible way.

Without loss of generality, assume that Alice chooses b = 0, i.e., the computational method

In the opening phase, Bob receives the secret key Sk from Alice, where s = s1s2…sk. Later, he undoes their initial rotations, i.e., to apply

By the assumption b′ = 0, Bob chooses to measure each qubit on the basis of

By the assumption b′ = 1, Bob chooses to measure each qubit on the basis of

The two cases, b′ = b and b′ ≠ b, occur both with a probability of 1/2. While in the first case Bob always gets r correctly, in the second case, the probability of getting correct rj is 1/2. Hence, the probability that Bob will get the whole random key r is

where ϵ(k) = 1/2kt+1 is negligible. Therefore, Alice is unaware of whether Bob received the correct message or not.

However, Bob can check whether he has recovered the correct random key r by comparing his hash value h(r′) with the second part of the received information d. According to the properties of the hash function, the probability of the first part of the hash value matching the second part is negligible in the case of Alice’s coding basis being different from the measurement basis chosen by Bob.

5.2 Concealing

In this section, we show that if Alice is honest, the probability of Bob recovering the message to transfer before the opening phase is negligible.

This part of the statement follows directly from the security of the qPKE construction. The entropy of the entire secret key is given by the joint entropy

where n is distributed uniformly over a finite interval

In addition, the secrecy of the secret key is guaranteed by the fact that the preparation of the public key state is unknown to everyone except Alice before the opening phase. The state of each qubit of the public key is randomly chosen by Alice and is independent of the other qubits. As proven in [27], with a proper choice of n, the qPKE construction is secure against unauthorized users based on the uncertainty principle. Therefore, with the same choice of a proper n, the unidirectionality of the one-way function ensures that Bob cannot learn the message that Alice meant to send before the opening phase, and the protocol is a concealing one.

5.3 Probabilistic transfer

Furthermore, after the opening phase, Bob recovers the message with, up to a negligible value, a probability 1/2 + ϵ(k). This part of the description can be attributed to the fact that after Bob receives the secret key from Alice in the opening phase, there is still no strategy to get the whole encoded random key.

The proposed scheme divides the random key r into t successive units of bits

Now consider dishonest Bob. First, we analyze the optimal cheating strategy if Bob has infinite ability. Bob chooses a basis to measure the quantum state, and if the projection is successful, i.e., the correct basis is chosen, he will further calculate to get the message. If the projection fails, Bob recovers the quantum state and then chooses another measurement basis and measures the quantum state again to obtain the message. However, both non-demolition measurements of qubits are out of technological reach today and could remain hard for a very long time for high k values [30]. Bob must therefore seek other strategies, such as utilizing the several qubits present in a shared unit to infer the coding basis with a probability greater than 1/2.

After undoing the initial rotation of the quantum state, Bob will get the following state:

Let

In summary, Bob can only infer whether the measurement basis is correct by parity bits, i.e., he has to try one basis to measure several shared units. According to the idea of secret sharing (any t − 1-shared units will get nothing about the message), these shared units would also be irreversibly damaged, making it impossible for him to obtain the message.

5.4 Oblivious

To conclude our discussion on security, we demonstrate that the protocol is oblivious. At the end of the protocol, Alice is unaware of whether Bob has received the message or not. The no-communication theorem may be referenced in this section of the statement. It should be noted that Alice’s attacks should not have the effect of making it difficult for Bob to know for sure whether he obtained the correct message or not, as this would go against the original objective of OT.

Theorem 2. (No-communication theorem). During the measurement of an entangled quantum state, it is not possible for one observer, by measuring a subsystem of the total state, to communicate information to another observer. The theorem gives conditions under which such transfer of information between two observers is impossible.As can be seen, Alice communicates with Bob in one-way communication, in which Bob performs local operations and measurements without communicating with Alice. Here, no follow-up communication of entanglement can be used to exchange and obtain information; therefore Alice has no way of knowing through entanglement whether Bob has chosen the correct measurement basis. Otherwise, one could achieve faster-than-light communication, thus explicitly violating causality and the principle of relativity. Indeed, what entanglement effects are the correlations: Bell inequalities are given in terms of various correlation functions, and the violation of local realism can be observed only upon distant observers exchanging the results of their local measurements. Alice honestly chooses the coding basis, sends the quantum state to Bob, and does not receive any feedback from Bob. Therefore, based on the no-communication theorem, Alice is oblivious to whether Bob gets the message or not.On the one hand, dishonest Alice could not convince Bob that the lack of access to the message was his own business without being detected as cheating. For this reason, Bob can check whether Alice is cheating by following the steps as follows: first, Bob measures the quantum bits at position [1, kt/2]. Each bit di of the hash value d = h(r) is the parity of the ith unit of the message; hence, all the bits of the digest are mutually independent. If he always observes the parity bit di matching the shared unit

where

6 Conclusion

In this article, we study the design methods and security analysis of the quantum all-or-nothing OT protocol based on secure quantum one-way functions, mainly in soundness, concealing, probabilistic transfer, and obliviousness. The proposed scheme does not violate the no-go theorem, and its security is based on the laws of quantum physics. In practice, the security of the protocol will remain very reliable for high k values because of limitations on non-demolition measurements. Moreover, the design of secure QOTs is important for building highly trusted cryptographic protocols and algorithms and is the foundation of quantum cryptographic protocols.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PW and YS conceived the presented idea. PW and YS developed the theory and the proofs. PW and ZS verified the methods. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61872245), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20210324100813034, JCYJ20190809152003992, and JCYJ20180305123639326), and Shenzhen Polytechnic Research Foundation (6022310031K).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Rabin M. How to exchange secrets with oblivious transfer. In: Technical report tech. Memo TR-81. Cambridge, MA: Aiken Computation Laboratory (1981).

2. Even S, Goldreich O, Lempel A. A randomized protocol for signing contracts. Commun ACM (1985) 28(6):637–47. doi:10.1145/3812.3818

3. Brassard G, Crépeau C, Robert JM. All-or-nothing disclosure of secrets. In: Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques (1986). p. 234–8.

4. Crépeau C. Equivalence between two flavours of oblivious transfers. In: Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques. Berlin, Germany: Springer (1987). p. 350–4.

5. Brassard G, Crépeau C, Robert JM. Information theoretic reductions among disclosure problems. In: 27th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (sfcs 1986). Toronto, ON, Canada: IEEE (1986). p. 168–73.

6. Crépeau C, Sántha M. Efficient reduction among oblivious transfer protocols based on new self-intersecting codes. In: Sequences II. Berlin, Germany: Springer (1993). p. 360–8.

7. Brassard G, Crépeau C, Santha M. Oblivious transfers and intersecting codes. IEEE Trans Inf Theor (1996) 42(6):1769–80. doi:10.1109/18.556673

8. Shor PW. Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. In: Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. Santa Fe, NM, USA: IEEE (1994). p. 124–34.

9. Heisenberg W. Über den anschaulichen inhalt der quantentheoretischen kinematik und mechanik. In: Original scientific papers wissenschaftliche originalarbeiten (1985). p. 478–504.

11. Bennett CH, Brassard G, Mermin ND. Quantum cryptography without bell’s theorem. Phys Rev Lett (1992) 68:557–9. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.68.557

12. Renner R, Gisin N, Kraus B. Information-theoretic security proof for quantum-key-distribution protocols. Phys Rev A (Coll Park) (2005) 72(1):012332. doi:10.1103/physreva.72.012332

13. Mayers D. Unconditionally secure quantum bit commitment is impossible. Phys Rev Lett (1997) 78:3414–7. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.78.3414

14. Lo HK, Chau HF. Is quantum bit commitment really possible? Phys Rev Lett (1997) 78:3410–3. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.78.3410

15. Lo HK, Chau H. Why quantum bit commitment and ideal quantum coin tossing are impossible. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena (1998) 120(1-2):177–87. doi:10.1016/s0167-2789(98)00053-0

16. Hughston L, Jozsa R, Wootters W. A complete classification of quantum ensembles having a given density matrix. Phys Lett A (1993) 183(1):14–8. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(93)90880-9

17. Halvorson H. Generalization of the hughston-jozsa-wootters theorem to hyperfinite von neumann algebras. J Math Phys (2003).

18. Bouman NJ, Fehr S, González-Guillén C, Schaffner C. An all-but-one entropic uncertainty relation, and application to password-based identification. In: Conference on Quantum Computation, Communication, and Cryptography. Berlin, Germany: Springer (2012). p. 29–44.

19. Wehner S, Schaffner C, Terhal BM. Cryptography from noisy storage. Phys Rev Lett (2008) 100(22):220502. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.100.220502

20. Konig R, Wehner S, Wullschleger J. Unconditional security from noisy quantum storage. IEEE Trans Inf Theor (1984) 58(3):1962–84. doi:10.1109/tit.2011.2177772

21. Souto A, Mateus P, Adao P, Paunković N. Bit-string oblivious transfer based on quantum state computational distinguishability. Phys Rev A (Coll Park) (2015) 91(4):042306. doi:10.1103/physreva.91.042306

22. Rodrigues J, Mateus P, Paunković N, Souto A. Oblivious transfer based on single-qubit rotations. J Phys A: Math Theor (2017) 50(20):205301. doi:10.1088/1751-8121/aa6a69

23. Grilo AB, Lin H, Song F, Vaikuntanathan V. Oblivious transfer is in miniqcrypt. In: Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques (2021). p. 531–61.

24. Bartusek J, Coladangelo A, Khurana D, Ma F. One-way functions imply secure computation in a quantum world. In: Annual International Cryptology Conference (2021). p. 467–96.

25. Shi J, Lu Y, Feng Y, Huang D, Lou X, Li Q, et al. A quantum hash function with grouped coarse-grained boson sampling. Quan Inf Process (2022) 21(2):73–17. doi:10.1007/s11128-022-03416-w

27. Nikolopoulos GM. Applications of single-qubit rotations in quantum public-key cryptography. Phys Rev A (Coll Park) (2008) 77(3):032348. doi:10.1103/physreva.77.032348

28. Nielsen MA, Chuang IL. Quantum computation and quantum information: 10th anniversary edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2010).

Keywords: oblivious transfer, quantum one-way function, no-communication theorem, practical secure, multi-party computation

Citation: Wang P, Su Y and Sun Z (2022) All-or-nothing oblivious transfer based on the quantum one-way function. Front. Phys. 10:979838. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2022.979838

Received: 28 June 2022; Accepted: 13 July 2022;

Published: 09 August 2022.

Edited by:

Tian-Yin Wang, Luoyang Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Tingting Song, Jinan University, ChinaJinjing Shi, Central South University, China

Lvzhou Li, Sun Yat-sen University, China

Copyright © 2022 Wang, Su and Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ping Wang, d2FuZ3BpbmdAc3p1LmVkdS5jbg==; Zhiwei Sun, c21la2VyQHN6cHQuZWR1LmNu

Ping Wang

Ping Wang Yiting Su1

Yiting Su1 Zhiwei Sun

Zhiwei Sun