95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Phys. , 13 April 2022

Sec. Optics and Photonics

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.857422

Qiuming Zeng1

Qiuming Zeng1 Yi Huang1*

Yi Huang1* Shuncong Zhong1,2*

Shuncong Zhong1,2* Tingling Lin1

Tingling Lin1 Yujie Zhong1

Yujie Zhong1 Zhenghao Zhang1

Zhenghao Zhang1 Yingjie Yu2

Yingjie Yu2 Zhike Peng3

Zhike Peng3A bilayer metamaterial to realize the broadband transmission in a terahertz (THz) filter was proposed, whose periodic unit structure consists of two rectangular apertures. The broadband consisting of three transmission peaks has a 3dB transmission range of 0.75 THz, which is 1.6 times that of the monolayer structure. Different from the traditional narrow band excitation mode, two additional transmission peaks are produced by the bilayer metamaterials. Sweeping frequency analysis has illustrated that the spacing between two layers of metamaterials has an influence on these additional transmission peaks. The bandwidth ranges can be regulated by adjusting the spacing at a proportional height. In particular, the experimental results show that the proposed filter has an excellent frequency selective performance with a bandwidth of 0.7 THz from 0.79 THz to 1.49 THz. This design of broadband filtering by introducing the bilayer metamaterial supplies a new approach with potential application in the THz broadband filter.

Terahertz (THz) radiation (0.1–10 THz) has drawn tremendous interest due to its incredible features, which have got extensive application in object imaging, non-destructive testing, satellite communication, medical diagnosis, and biosensing [1–6]. In recent years, owing to the ability to control electromagnetic waves in a unique manner, metamaterials (typically referring to surface plasmon polaritons, SPPs) have become essential core components in various THz functional devices [7–10], but the usage of metamaterial is relatively less employed in broadband modulation, especially in THz metamaterial bandpass filters. Traditional metamaterials THz filters are usually based on a single-layer metal structure designed with subwavelength periodic patterns [11–13]. As the THz wave in a certain frequency band travels through the subwavelength structure with periodicity, the free electrons respond collectively by oscillating in resonance with the light wave. An intense confined electromagnetic field is supported by this resonance to promote light–matter interactions and derive dramatic spectral characteristics [14, 15]. However, the resonance depending on the specific structure only corresponds to a sharp transmission peak with the enormous enhancement of the amplitude in the spectrum. The existing transmission mode based on the single structure cannot adequately meet the practical application of broadband THz filters.

Recently, substantial valid approaches have been conducted to fulfill the requirement for broadband filters. The most direct method is designing a complex construction or stacking multilayer structures without two-dimensional (2D) materials, such as a free-standing and a polarization insensitive terahertz filter composed of cross and rectangular apertures in a monolayer metamaterial [16], a set of H-shaped resonators with different sizes in a regular array [17], a broadband terahertz metamaterial filter and its complementary metasurface electromagnetically induced transparency structure [18], a second-order frequency selective surface (FSS) composed of two layers of metallic arrays separated from each other by a polymer dielectric spacer [19], and a tunable terahertz metamaterial by using three-dimensional double split-ring resonators [20]. In these ways, different parts of the metal patterns enable the incoming THz waves in adjacent frequencies to inspire SPPs. All sharp transmission peaks induced by the SPP mode will be combined to keep continuous high transmittance in the spectrum, which explains the formation of broadband transmission. Then, the other method is to stack multilayer structures with 2D materials [21]. By regulating the surface conductivity of 2D materials, such as chemical doping, optical pumping, or bias voltage, the broadband bandpass with a large range can be reached [22–25]. However, most of the THz metamaterial filters mentioned earlier are too complex to restrict their processing, and the range of bandwidth generated by superimposing resonance is limited because it is difficult to stack an infinite number of sandwich structures decorated with cyclical designs in a nanoscale space.

In this article, a bilayer bandpass filter with a double rectangular hole periodic array structure is proposed and experimentally demonstrated. Femtosecond laser direct writing technology is utilized to fabricate the metamaterial filters on the aluminum foil. After that, the transmission curves corresponding to different structures have been compared to verify the broadband filtering performance using experiment and simulation. Meanwhile, the mechanism of excitation for wideband transmission was analyzed by FEM calculation. Different from the excited mode of the narrow band, the bilayer metamaterial produces more resonance peaks with high transmittance, and some of them will form a broadband at the specific spacing. Therefore, a thorough exploration on the variation of resonance frequencies was conducted using simulation and numerical analyses. Finally, the experimental consequence was measured by THz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) to prove the previous analysis.

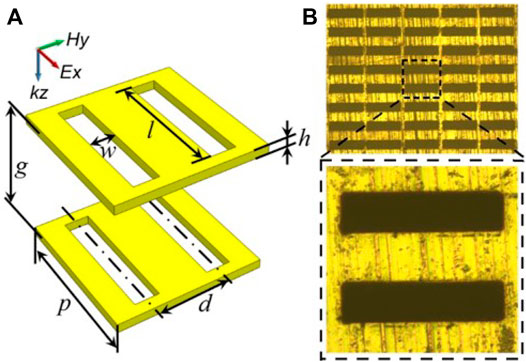

Figure 1A shows the schematic diagram of the bandpass metamaterial filter which is composed of two layers of aluminum foil with a thickness of h = 10 μm. The tunable spacing between two monolayer samples was set as g. The period of the unit cell along the x (Px) and y (Py) directions are both 180 μm. Each subwavelength periodic structure has the same dimensions, which are as follows: the length and width of rectangular holes are l = 150 μm and w = 30 μm, and the center distance is d = 45 μm. The applicable structural parameters are acquired by using the eigenmode solver of commercial CST Microwave Studio software before manufacturing. Periodic boundary conditions are employed both in the x and y directions with an open (add space) boundary in the z direction. As for the settings of the incident wave, the incoming port is automatically added in the z direction, which is perpendicular to the metallic surface. The electric field of the incident wave is polarized in the x direction.

FIGURE 1. Schematic diagram (A) of the bilayer THz metamaterial filter with a period of p = 180 μm, rectangular hole length of l = 150 μm, width of w = 30 μm, central distance of d = 45 μm, thickness of h = 10 μm, and spacing of g = 130 μm. Optical microscopy imaging (B) of the fabricated metamaterial and partial enlarged drawing.

According to the optimized physical dimensions, the proposed THz metamaterial filter is fabricated on aluminum foils with a conductivity of 3.56 × 107 S/m using an ultrafast high-intensity laser technology. The chosen femtosecond laser has 45 fs pulse width, 800 nm wavelength, and 1 kHz repetition rate. First, the aluminum foil with a thickness of 10 μm is affixed on a hollow square plate as a free-standing sample for processing and experiment. The square plate size is 5 × 5 cm2. Before the actual processing, we performed a trial cut on the corner area of the aluminum foil to make sure that the foil is flat and well affixed on the square plate. The sample is placed on a computer-controlled three-axis machining platform. Then, the laser with 10 μm spot size and 200 μm/s moving speed is employed to fabricate the arrayed aperture. At the same time, an objective lens is used to focus the femtosecond laser on the surface. The entire process can be monitored in real-time by using a CCD imaging system and displayed on the computer screen. The aluminum foil is periodically patterned with rectangular apertures with a total area of 9 × 9 mm2. The microscopic imaging of the fabricated structure and its partially enlarged drawing are depicted in Figure 1B. It can be seen that the aperture edge is smooth and straight, and the similarity of each unit is high, indicating a good processing quality. Unlike micro-nano manufacturing methods, such as the conventional photolithography technology, femtosecond laser ablation has the advantage of a simple machining process, low cost, and high efficiency, which is appropriate for the fabrication of the periodic aperture structure [26, 27].

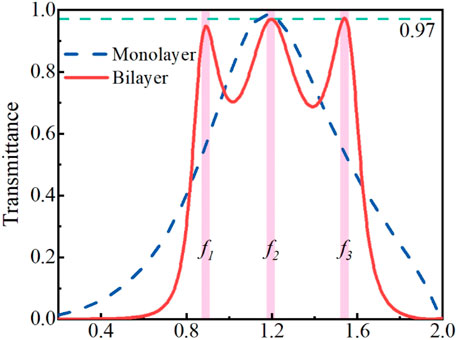

Figure 2 illustrates the transmission spectra of the monolayer structure (the blue dash line) and those of the bilayer structure (the red solid line) in the case that the spacing is g = 130 μm. The monolayer structure produces a transmission curve that possesses a transmission peak of transmittance (T) = 98.41% at 1.178 THz with a 3 dB transmission range of 0.47 THz. The periodical apertures can be regarded as the subwavelength structure to induce SPPs [28, 29] whose resonance frequency is directly associated with the geometrical parameters of the apertures, which can be calculated by the following formula [30]:

FIGURE 2. Simulated transmission spectra of the monolayer structure (the blue dash line) and bilayer structure (the red solid line). Three transmission peaks are 0.89, 1.19, and 1.54 THz, respectively.

Under the circumstance of the bilayer structure, there is no longer one central frequency but three transmission peaks occur at f1 (0.89 THz), f2 (1.19 THz), and f3 (1.54 THz). The transmission values we obtained for the three peaks are 94.75, 96.97, and 97.3%, respectively. The curvilinear path of the transmission peak at f2 (1.19 THz) is almost identical to that in the single-layer filter. This means that the SPP mode supported on the bilayer structure resembles that of the monolayer structure. The resonance frequency can also be calculated by formula [1]. Two additional peaks with a transmittance over 0.9 appeared at f1 and f3, resulting from the near-field coupling of two plasmonic structures with the same dimension [31–33]. More importantly, three peaks are sufficiently close to each other, which allow the non-destructive overlap of the transmission spectra to realize a 3dB broadband transmission with the range of 0.75 THz, accompanied by a slight drop between each peak. Moreover, the broadband edges display superior frequency selective characteristics due to the steeper roll-off rate and higher out-of-band values.

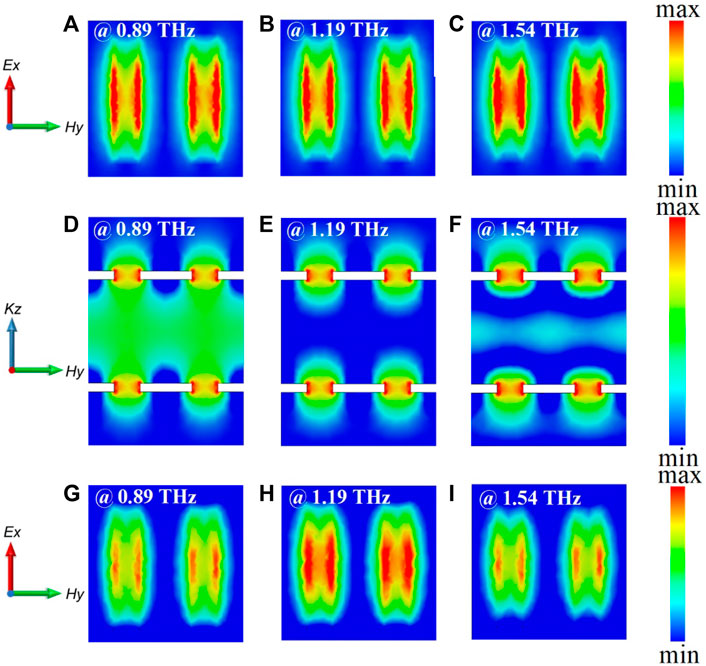

For further investigating the underlying mechanism of the transmission response for the bilayer filter, the electric field distributions of the upper metal surface at three transmission peaks are plotted in Figure 3A–C. As it can be seen, two rectangular apertures have the same electric field distribution, which is concentrated around the hole. Due to the SPPs on the metal surface, the free electrons respond collectively on the long side of rectangular apertures by oscillating in resonance with the light wave [34]. Meanwhile, there is no difference in electric field distribution between each peak except for a slight rise in the response intensity. To better distinguish the differences between each electric field, the corresponding electric field diagram on the side of the structure was plotted. As seen from Figure 3D–F, the SPP wave is excited so that the electric field is strongly confined in the metal aperture as expected, and the upper metal has the same electric field distribution as the lower metal. Specifically, an unusual distribution with a weaker electromagnetic response is filled with all interspace, as depicted in Figure 3D. By comparison, there is no electric field enhancement in the spacing in Figure 3E, indicating that no additional coupling occurs at this frequency. Moreover, it can be observed from Figure 3F that the motivated field only takes up a fraction at the gap, which may originate from higher-order resonance using the bilayer metamaterial [35, 36]. The electric field of a single layer is plotted in Figure 3G–I to distinguish the difference of the coupling effect in each transmission peak. Figure 3H shows that the electric field at 1.19 THz for the single layer is the same as the double layer plotted in Figure 3B. As can be seen from Figures 3G,I, the electric field strength is much lower than that of the double layer. It can be concluded from the aforementioned electric field analysis that the coupling intensity of the SPP mode can be improved by introducing a bilayer metamaterial.

FIGURE 3. Electric field distributions of the upper metal surface at transmission peaks (A) 0.89 THz, (B) 1.19 THz, and (C) 1.54 THz, respectively. The electric field distributions on the side of the double-layer structure at transmission peaks (D) 0.89 THz, (E) 1.19 THz, and (F) 1.54 THz, respectively. The electric field distributions of the single layer at transmission peaks (G) 0.89 THz, (H) 1.19 THz, and (I) 1.54 THz, respectively.

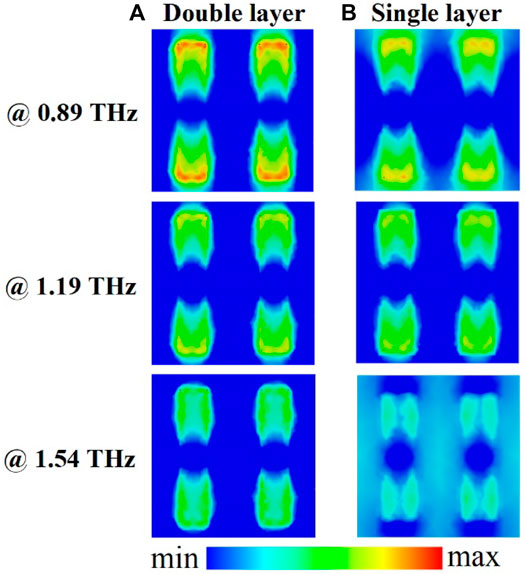

We further depicted the magnetic field distribution in Figure 4. It is observed that the magnetic fields are all excited on the short side of the rectangular apertures. By making a comparison with the single and double layers corresponding to Figure 4A and Figure 4B, the field intensity in the double layer at f1 (0.89 THz) or f3 (1.54 THz) is stronger than that in the single layer. It means that the resonance intensity can be enhanced by the near-field interaction between two plasmonic structures.

FIGURE 4. Magnetic field distributions of (A) double layer and (B) single layer for three transmission peaks at 0.89, 1.19, and 1.54 THz, respectively.

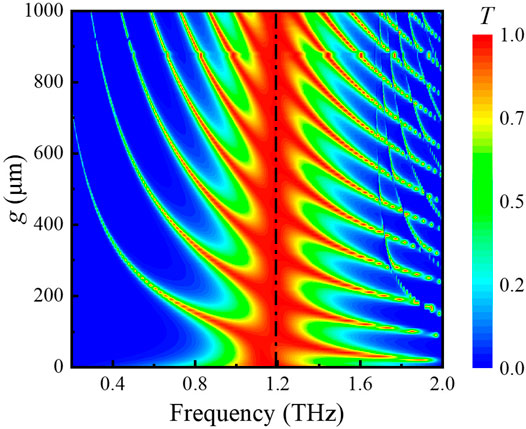

The variation law of high transmittance peaks is performed using rigorous simulations by varying the spacing between two layers of metal. The variation trend of T for different frequencies and spacings are calculated by FEM calculation with CST Microwave Studio software (the spacing g is from 1 to 1,000 μm, step length is 10 μm, and the frequency sweep range is from 0.2 to 2 THz). As can be seen from Figure 5, a pronounced high transmission area is concentrated around the nearby region of 1.19 THz highlighted by the vertical black dash dot line. It suggests that the central frequency based on FSS will be invariant until the fixed construction changes. Meanwhile, the rest transmission peaks will redshift as the spacing length increases gradually and eventually form a red airfoil-like stripe on both sides of the central frequency without any consecutive constructive and destructive interferences. When the spacing augments to a certain value, there will be a new transmission peak arising in the high-frequency region, which attributes to the coupling of the higher-order resonance mode. Moreover, the slope of the redshift curve for the single-resonant frequency increases gradually, and the movement trend of each peak is astonishingly consistent. Thus, these interesting phenomena demonstrate that the spacing between the two layers of metamaterials is a key to control the peak number and resonance intensity. The bilayer structure in a specific spacing may be used in exciting more resonance frequencies with high transmittance.

FIGURE 5. Contour map of the transmittance with changing spacing from 0 to 1,000 μm at a THz range from 0.2 to 1.8 THz. The vertical highlighted line is at f2 = 1.19 THz.

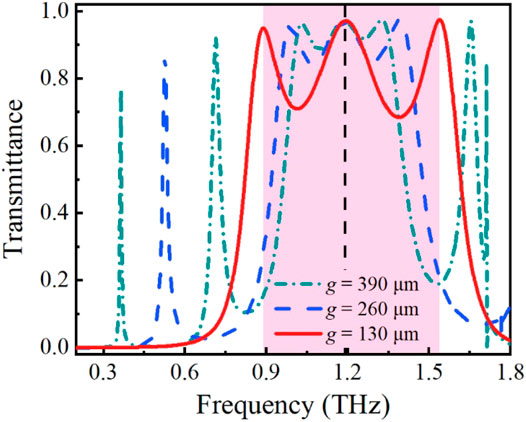

To obtain the largest bandwidth for a bilayer metamaterial filter, three transmission curves corresponding to different intervals are plotted in Figure 6. All of them can produce a wideband by coupling three transmission peaks. The transmission peaks increase, and the distance between each resonance peak becomes shorter as the spacing increases. The transmittance diminishes as the peak shifts further and further away from the central frequency. Owing to the non-destructive superimposed effect, the loss between each peak is in decline. By comparing the broadband range in each curve, the broadband range reaches a maximum value of 0.65 THz in the case of the spacing equal to 130 μm (the scope is distinguished by pink). The simulation result demonstrates that this bilayer filter can acquire different broadband ranges by regulating the spacing and has significant design portability.

FIGURE 6. Transmission spectra of the bilayer structure at 130 μm, 260 μm, and 390 μm, respectively. f2 is the central frequency at 1.19 THz.

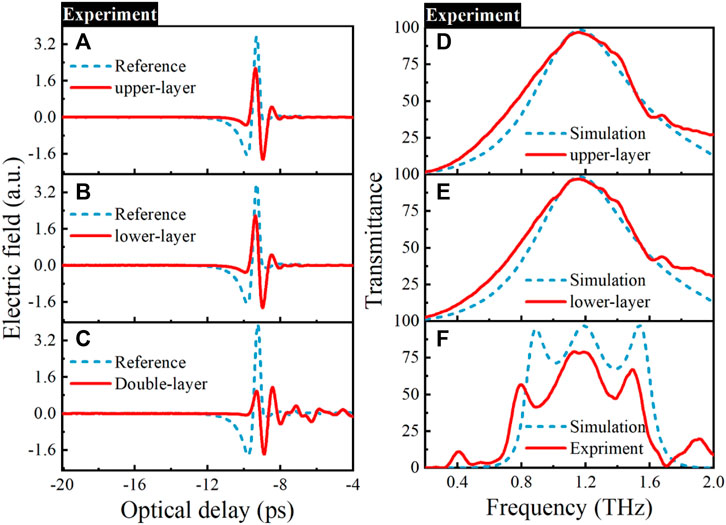

A photoconductive THz-TDS system (commercial terahertz detection system-TeraPulse 4000) filled with nitrogen gas was utilized to measure the actual transmission spectra for the metamaterial filter. A GaAs photoconductive antenna is irradiated by the femtosecond laser, whose central wavelength is 780 nm, the pulse width is about 100 fs, the repetition rate is 100 MHz, and the output power is greater than 65 mW, to produce and detect the THz radiation whose detection ranges from 0.1 to 4 THz. Figure 7A and Figure 7B depict the experimental time-domain waveforms for the monolayer structure. The blue dash line shows the original THz time-domain signal without matter, which is chosen as the reference signal. The red solid line demonstrates that the amplitude of the time-domain wave peaks reduces significantly due to the reflection of the metal surface for the incident wave [37]. Meanwhile, the primary dip approached flat and a new dip with the electric intensity at -1.6 appears after the peak. The transmission spectra of the metamaterial can be calculated by the following equations:

where

FIGURE 7. Experimental THz time-domain signal (red solid lines) and reference signal (blue dash lines) for the structure of upper layer (A), lower layer (B), and double layer (C). Experimental transmittance spectra of the monolayer filter (D,E) and the proposed double layer metamaterial filter (F) obtained by using simulation (blue dash lines) and experiment (red solid lines).

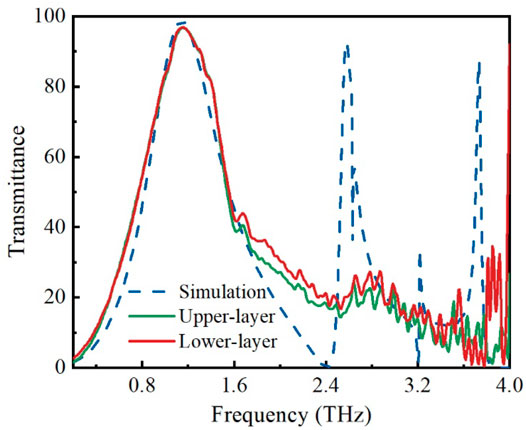

Meanwhile, the experimental transmission spectra from the metamaterial filter for the upper and lower layers with the same set of parameters are compared to the simulation results in Figure 8. The obtained curves of the first transmission peak for the two samples are highly consistent and match exceptionally well with simulation. In addition, the experimental spectrum in high frequencies do not develop transmission peaks as the simulation has expected due to the interference of system noise, which is not related to the scope of this study. Overall, the experimental spectra in the region of interest are in good agreement with the simulation result so that we can utilize them to build a double-layer filter to verify the broadband coupling reaction. We stacked hollow and ultra-thin polytetrafluoroethylene to control the spacing between the two layers of the metal structure. Then, the fixture was used to clamp the processed specimen to improve the experimental accuracy. Figure 7C shows the experimental results about the time-domain signal of the double-layer metamaterial filter and the reference signal. As it can be seen, the first time-domain wave peak declines even more while a new peak with a higher value is motivated, and there will be irregular fluctuations in a low amplitude behind them. These experimental results are a good validation of the previous inference that the resonance intensity can be enhanced by the bilayer metamaterial. Figure 7F depicts the simulated and experimentally transmission spectrum of the double-layer metamaterial. Although the transmittance is reduced and the spectrum redshifts in general, the experimental results are in good agreement with the simulated results. The measured bandpass filter has a wider broadband of 0.7 THz from 0.79 to 1.49 THz, with the center frequency located at 1.15 THz. The redshift of the transmission curve overall and the enlarging bandwidth may derive from the larger processing dimension caused by the unmanageable laser spot [38]. On the other hand, the propagation of incident waves is impeded by the imperfect alignment of apertures for two monolayer filters, which lead to transmission reduction [39]. To optimize the actual experimental situation, the improvement of the spot size and surface roughness in femtosecond laser processing is another important research content in the future.

FIGURE 8. Comparison for transmission spectra about the simulation results and two samples with the same set of parameters.

In summary, we have experimentally demonstrated a broadband THz filter made up of double-layer metal structures. In contrast to the monolayer structure, the bilayer metamaterial produces two additional peaks with high transmittance. The enhancement of the resonance intensity is attributed to the near-field interaction between two layers of metamaterials. More importantly, two transmission peaks are close to the center frequency so that a 3 dB broadband with the range from 0.84 THz to 1.59 THz is formed. The broadband edges possess better frequency selectivity due to the steeper roll-off rate. Numerical analyses show that the spacing between two layers of metamaterials have an influence on the number and amplitude of resonance frequencies. The broadband scope can be obtained by controlling the spacing at the specific values. The experimental transmission spectrum demonstrates that the bandpass filter has a broadband of 0.7 THz from 0.79 THz to 1.49 THz, positively verifying the simulation and theoretical analysis. Therefore, this coupling mode produced in the bilayer metamaterial to realize the greater broadband range with stronger resonance intensity provides a new design idea to the broadband THz filter.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

YH and SZ put forward the initial idea and supervised the project. QZ and YH further developed and confirmed the idea through analysis and simulations. QZ conducted sample fabrication. TL and YZ conducted data analysis and collection. ZZ performed image processing. SZ, YY and ZP provided methodology and resources. QZ, YH and SZ wrote the manuscript with inputs from all other authors. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (51675103), the Fujian Provincial Science and Technology Project (2019I0004), the State Key Laboratory of Mechanical Systems and Vibration (MSV-2018-07), and the Shanghai Natural Sciences Fund (18ZR1414200).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Ahmadivand A, Gerislioglu B, Ahuja R, Kumar Mishra Y. Terahertz Plasmonics: The Rise of Toroidal Metadevices towards Immunobiosensings. Mater Today (2020) 32:108–30. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2019.08.002

2. Huang Y, Zhong S, Shi T, Shen Y-c., Cui D. Terahertz Plasmonic Phase-Jump Manipulator for Liquid Sensing. Nanophotonics (2020) 9(9):3011–21. doi:10.1515/nanoph-2020-0247

3. Jia S, Yu X, Hu H, Yu J, Guan P, Da Ros F, et al. THz Photonic Wireless Links with 16-QAM Modulation in the 375-450 GHz Band. Opt Express (2016) 24(21):23777–83. doi:10.1364/OE.24.023777

4. Kawase K, Ogawa Y, Watanabe Y, Inoue H. Non-destructive Terahertz Imaging of Illicit Drugs Using Spectral Fingerprints. Opt Express (2003) 11(20):2549–54. doi:10.1364/OE.11.002549

5. Li K, Wu J, Wu F, Guo D, Chen L, Fang Z, et al. The Clinical and Chest CT Features Associated with Severe and Critical COVID-19 Pneumonia. Invest Radiol (2020) 55(6):327–31. doi:10.1097/RLI.0000000000000672

6. Zhong S. Progress in Terahertz Nondestructive Testing: A Review. Front Mech Eng (2019) 14(3):273–81. doi:10.1007/s11465-018-0495-9

7. Huang Y, Zhong S, Shi T, Shen Y-C, Cui D. HR-si Prism Coupled Tightly Confined Spoof Surface Plasmon Polaritons Mode for Terahertz Sensing. Opt Express (2019) 27(23):34067–78. doi:10.1364/OE.27.034067

8. Nemati A, Wang Q, Wang Q, Hong M, Teng J. Tunable and Reconfigurable Metasurfaces and Metadevices. Opto-electron Adv (2018) 1(5):18000901–25. doi:10.29026/oea.2018.180009

9. Sun Z, Martinez A, Wang F. Optical Modulators with 2D Layered Materials. Nat Photon (2016) 10(4):227–38. doi:10.1038/NPHOTON.2016.15

10. Nagatsuma T, Ducournau G, Renaud CC. Advances in Terahertz Communications Accelerated by Photonics. Nat Photon (2016) 10(6):371–9. doi:10.1038/NPHOTON.2016.65

11. Wang DS, Chen BJ, Chan CH. High-Selectivity Bandpass Frequency-Selective Surface in Terahertz Band. IEEE Trans Thz Sci Technol (2016) 6(2):284–91. doi:10.1109/TTHZ.2016.2526638

12. Wang Q, Gao B, Raglione M, Wang H, Li B, Toor F, et al. Design, Fabrication, and Modulation of THz Bandpass Metamaterials. Laser Photon Rev (2019) 13(11):1900071. doi:10.1002/lpor.201900071

13. Zhang M, Zhang J, Chen A, Song Z. Vanadium Dioxide-Based Bifunctional Metamaterial for Terahertz Waves. IEEE Photon J. (2020) 12(1):1–9. doi:10.1109/JPHOT.2019.2958340

14. Huang Y, Zhong S, Shi T, Shen Y-C, Cui D. Trapping Waves with Tunable Prism-Coupling Terahertz Metasurfaces Absorber. Opt Express (2019) 27(18):25647–55. doi:10.1364/OE.27.025647

15. Lin T, Huang Y, Zhong S, Luo M, Zhong Y, Yu Y, et al. Sensing Enhancement of Electromagnetically Induced Transparency Effect in Terahertz Metamaterial by Substrate Etching. Front Phys (2021) 9:664864. doi:10.3389/fphy.2021.664864

16. Manikandan E, Sreeja BS, Radha S, Bathe RN, Jain R, Prabhu S. A Rapid Fabrication of Novel Dual Band Terahertz Metamaterial by Femtosecond Laser Ablation. J Infrared Milli Terahz Waves (2018) 40(1):38–47. doi:10.1007/s10762-018-0543-x

17. Cui Z, Zhu D, Yue L, Hu H, Chen S, Wang X, et al. Development of Frequency-Tunable Multiple-Band Terahertz Absorber Based on Control of Polarization Angles. Opt Express (2019) 27(16):22190–7. doi:10.1364/OE.27.022190

18. Sun D, Qi L, Liu Z. Terahertz Broadband Filter and Electromagnetically Induced Transparency Structure with Complementary Metasurface. Results Phys (2020) 16:102887. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2019.102887

19. Ebrahimi A, Nirantar S, Withayachumnankul W, Bhaskaran M, Sriram S, Al-Sarawi SF, et al. Second-Order Terahertz Bandpass Frequency Selective Surface with Miniaturized Elements. IEEE Trans Thz Sci Technol (2015) 5(5):761–9. doi:10.1109/TTHZ.2015.2452813

20. Lin Y-S, Liao S, Liu X, Tong Y, Xu Z, Xu R, et al. Tunable Terahertz Metamaterial by Using Three-Dimensional Double Split-Ring Resonators. Opt Laser Tech (2019) 112:215–21. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2018.11.020

21. Dideikin AT, Vul' AY. Graphene Oxide and Derivatives: The Place in Graphene Family. Front Phys (2019) 6:149. doi:10.3389/fphy.2018.00149

22. Huang Y, Zhong S, Shen Y-c., Yu Y, Cui D. Terahertz Phase Jumps for Ultra-sensitive Graphene Plasmon Sensing. Nanoscale (2018) 10(47):22466–73. doi:10.1039/c8nr08672a

23. Sun J-Z, Li J-S. Broadband Adjustable Terahertz Absorption in Series Asymmetric Oval-Shaped Graphene Pattern. Front Phys (2020) 8:245. doi:10.3389/fphy.2020.00245

24. Tan Z-Y, Fan F, Chang S-J. Active Broadband Manipulation of Terahertz Photonic Spin Based on Gyrotropic Pancharatnam-Berry Metasurface. IEEE J Select Top Quan Electron. (2020) 26(6):1–8. doi:10.1109/JSTQE.2020.2984560

25. Zhong Y, Huang Y, Zhong S, Lin T, Luo M, Shen Y, et al. Tunable Terahertz Broadband Absorber Based on MoS2 Ring-Cross Array Structure. Opt Mater (2021) 114:110996. doi:10.1016/j.optmat.2021.110996

26. Ma Z-C, Zhang Y-L, Han B, Chen Q-D, Sun H-B. Femtosecond-Laser Direct Writing of Metallic Micro/Nanostructures: From Fabrication Strategies to Future Applications. Small Methods (2018) 2(7):1700413. doi:10.1002/smtd.201700413

27. Tanaka T, Sun H-B, Kawata S. Rapid Sub-diffraction-limit Laser Micro/nanoprocessing in a Threshold Material System. Appl Phys Lett (2002) 80(2):312–4. doi:10.1063/1.1432450

28. Kumar G, Cui A, Pandey S, Nahata A. Planar Terahertz Waveguides Based on Complementary Split Ring Resonators. Opt Express (2011) 19(2):1072–80. doi:10.1364/oe.19.001072

29. Zhu W, Agrawal A, Cui A, Kumar G, Nahata A. Engineering the Propagation Properties of Planar Plasmonic Terahertz Waveguides. IEEE J Select Top Quan Electron. (2011) 17(1):146–53. doi:10.1109/JSTQE.2010.2051799

30. Nolte DD, Lange AE, Richards PL. Far-infrared Dichroic Bandpass Filters. Appl Opt (1985) 24(10):1541–5. doi:10.1364/AO.24.001541

31. Ferraro A, Tanga AA, Zografopoulos DC, Messina GC, Ortolani M, Beccherelli R. Guided Mode Resonance Flat-Top Bandpass Filter for Terahertz Telecom Applications. Opt Lett (2019) 44(17):4239–42. doi:10.1364/OL.44.004239

32. Rao L, Yang D, Zhang L, Li T, Xia S. Design and Experimental Verification of Terahertz Wideband Filter Based on Double-Layered Metal Hole Arrays. Appl Opt (2012) 51(1):912–6. doi:10.1364/AO.51.000912

33. Chiang Y-J, Yang C-S, Yang Y-H, Pan C-L, Yen T-J. An Ultrabroad Terahertz Bandpass Filter Based on Multiple-Resonance Excitation of a Composite Metamaterial. Appl Phys Lett (2011) 99(19):191909. doi:10.1063/1.3660273

34. Shen X, Cui TJ. Ultrathin Plasmonic Metamaterial for Spoof Localized Surface Plasmons. Laser Photon Rev (2014) 8(1):137–45. doi:10.1002/lpor.201300144

35. Mavrona E, Rajabali S, Appugliese F, Andberger J, Beck M, Scalari G, et al. THz Ultrastrong Coupling in an Engineered Fabry-Perot Cavity. ACS Photon (2021) 8(9):2692–8. doi:10.1021/acsphotonics.1c00717

36. Schalch J, Duan G, Zhao X, Zhang X, Averitt RD. Terahertz Metamaterial Perfect Absorber with Continuously Tunable Air Spacer Layer. Appl Phys Lett (2018) 113(6):061113. doi:10.1063/1.5041282

37. Zhang Y, Xu G, Qiao S, Zhou Y, Wu Z, Yang Z. Enhanced THz Resonance Based on the Coupling between Fabry-Perot Oscillation and Dipolar-like Resonance in a Metamaterial Surface Cavity. J Phys D: Appl Phys (2015) 48(48):485105. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/48/48/485105

38. Lin Y, Yao H, Ju X, Chen Y, Zhong S, Wang X. Free-standing Double-Layer Terahertz Band-Pass Filters Fabricated by Femtosecond Laser Micro-machining. Opt Express (2017) 25(21):25125–34. doi:10.1364/OE.25.025125

Keywords: metamaterials, surface plasmon polaritons, terahertz, broadband transmission, filter

Citation: Zeng Q, Huang Y, Zhong S, Lin T, Zhong Y, Zhang Z, Yu Y and Peng Z (2022) Multiple Resonances Induced Terahertz Broadband Filtering in a Bilayer Metamaterial. Front. Phys. 10:857422. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2022.857422

Received: 18 January 2022; Accepted: 21 March 2022;

Published: 13 April 2022.

Edited by:

Venu Gopal Achanta, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, IndiaReviewed by:

Goutam Rana, SRM University, IndiaCopyright © 2022 Zeng, Huang, Zhong, Lin, Zhong, Zhang, Yu and Peng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Huang, WWlIdWFuZ0BmenUuZWR1LmNu; Shuncong Zhong, emhvbmdzaHVuY29uZ0Bob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.