- 1Key Laboratory of Intelligence Computing and Novel Software Technology, Tianjin University of Technology, Tianjin, China

- 2Engineering Research Center of Learning-Based Intelligent System, Ministry of Education, Tianjin, China

Previous studies have verified that the local-world mechanism can greatly affect the structural properties and dynamical processes occurring on isolated complex networks; however, the impact of local-world mechanism on structural vulnerability of interdependent systems is still not efficiently explored. Therefore, in this study, the joint influence of interdependence and local worlds on attack vulnerability of interdependent networks is addressed. First, a partially interdependent system model is proposed, consisting of two networks which are dependent on each other with different types of interdependence preference. In particular, each network evolves according to the local-world model with an adjustable parameter to control the size of local worlds during network evolution. Next, the cascading failure process induced by intentional attack on high-degree nodes is presented. Then, the responses of interdependent systems after cascading failures are investigated through large quantities of numerical simulations. The results show that the emergence of local worlds during network evolution plays an important role in the structural vulnerability of both single and interdependent networks; that is, networks with larger size of local worlds are found to be more vulnerable against attacks. Moreover, interdependent links make the entire system much more fragile, especially when the networks are with max–max assortative interdependence and the strength is enhanced. These results are beneficial to the deep understanding of the intrinsic connection between attack robustness and underlying structure of large-scale interdependent systems.

Introduction

In the past two decades, network science has been developed rapidly and enriched fruitful results in many fields [1–3]. Among all the active topics, due to the importance of network models in characterizing the structural properties and dynamics of complex large-scale systems, the study on a variety of network models is of great significance. For example, many real-world systems can be classified into and modeled as scale-free networks, such as Internet, World Wide Web, movie actor collaboration networks, and paper citation networks [4]. Let

In order to interpret the underlying formation mechanism of the abovementioned scale-free property, Barabási and Albert proposed the classical BA scale-free model [4], which includes two important ingredients: I) network growth, which means that new nodes and links are added into the network continuously, and II) preferential attachment in linking new-added nodes and old nodes. These two ingredients are thought to be responsible for the appearance of power-law degree distributions in many systems. However, during the evolution of many real-world complex networks, preferential attachment mechanism is found to only take effect in the local worlds, not the entire network [6]. Therefore, considering the local-world effect during network evolution, Li and Chen proposed the local-world evolving model [7]. An adjustable parameter, M, is introduced into the evolution of networks, which controls the size of the local worlds of the new-added nodes in which the preferential attachment mechanism works. As M increases, that is, the local world becomes larger, the resultant networks can show transitional behaviors between exponential and scale-free networks with respect to node degree distributions.

Motivated by this pioneering work, subsequent studies have been focused on local-world effect in modeling real-world complex networks, characterizing underlying structures and analyzing important dynamical processes occurring in complex systems. Some variants of local-world models are continually proposed to better understand the structural and functional properties of real systems, such as wireless communication networks [8], power grids [9], and energy supply–demand system [10]. Also, localization mechanism has been incorporated into the construction of other models in describing the structures of hypernetworks [11], bipartite networks [12], and weighted networks [13]. In addition, several important topological properties, such as clustering [14], community [15], hierarchical structures [16], and local neighborhood [17], are combined with the local-world effect to comprehensively uncover the underling structure of large-scale systems. Furthermore, previous findings have revealed that local-world effect can greatly affect the dynamical processes and collective behaviors of complex networks, including attack robustness [18], synchronization [19], epidemic spreading [20], cascading failures [21], consensus [22], and structural controllability [23].

In reality, many natural, technological, and social systems are composed of fully or partially interdependent networks [24, 25], which are becoming increasingly dependent on each other since no particular network can exist in isolation. Take the interdependence between three modern critical infrastructures, for instance, considering water supply system, communication network, and power grids, communication network and water supply system require power grids to provide power support for normal operations, power grids and water supply system need communication network to transmit control signals, and power grids require water supply system to cool down the electric generators. Particularly, due to the dependencies between networks, interdependent systems are extremely vulnerable to damage; that is, a small disturbance can result in a cascade of failures propagating through the interdependent connections between networks [26–28]. Hence, understanding the vulnerability of interdependent systems is of vital importance [29–37]. Attack vulnerability is regarded as one fundamental problem in many artificial and real-world interdependent networks, which has attracted extensive attention in the academic communities [38–42].

Although localization has been considered as an indispensable mechanism in modeling and analyzing isolated complex systems, the combined study of interdependence and local-world mechanism is not sufficiently explored by far. Especially for attack vulnerability, isolated [18] and fully interdependent local-world networks [43] have been investigated, and it is found that the existence of local worlds during network evolution can have a great impact on networks’ performance-resisting attacks. These results motivate us to extent the study to partially interdependent networks to future explore the joint influence of interdependence and local-world effect on attack vulnerability. First, a partially interdependent system model is constructed, consisting of two networks which are dependent on each other with different coupling preference. In particular, each network is evolved according to the local-world model with an adjustable parameter to control the size of local worlds. Then, after the attack on a small fraction of nodes, the process of cascading failures of nodes and links in partially interdependent system is described. Moreover, different from random attack simulated by selecting and removing nodes randomly, an important and realistic attacking strategy in real world—intentional attack on high-degree nodes—is considered in this study.

The structure of the article is organized as follows. In Section 2, a partially interdependent system model is presented, consisting of two networks which are dependent on each other. Then, the cascading failure process induced by intentional removal of a small fraction of high-degree nodes is described in detail. In Section 3, through large quantities of numerical simulations, the impacts of local worlds and interdependence on system’s performance after cascading failures are investigated. Section 4 includes the conclusion of the whole article and the perspective on future works.

Models and Vulnerability Metrics

Interdependent Local-World Networks

In order to further investigate the joint influence of both interdependence and local worlds on structural vulnerability of interdependent networks, a partially interdependent system model with two networks, that is, networks A and B, is established based on the fully interdependent system model proposed by Buldyrev et al. [24]. This model considers both interdependence strength and preference. In the meantime, to explore the effect of local-world mechanism during network evolution, A and B are constructed according to the local-world evolving model [7].

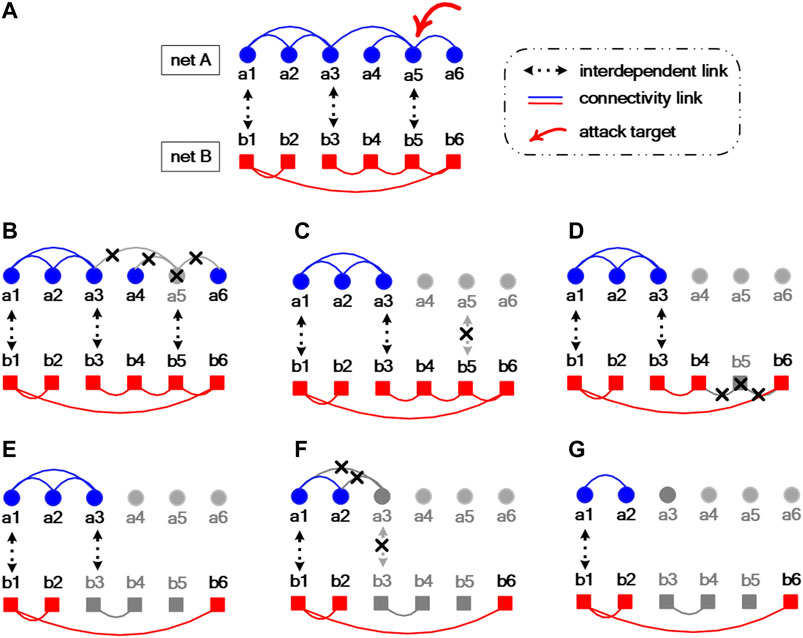

An example of such interdependent system is exhibited in Figure 1A, which is composed of two networks A (

FIGURE 1. (Color online) Schematic illustration of a partially interdependent system with two networks (A and B) and the cascade process of successive failures of nodes and links of both networks induced by single node removal (

Interdependence Strength

Even in real-world interdependent systems, there exist some nodes which have no dependency on other networks. To this end, different from fully interdependent networks, the partially interdependent model involves an important parameter, q, to define the fraction of nodes in one network which have interdependent links. Thus, q (

Interdependence Preference

Two kinds of interdependent interaction preference, that is, assortative and disassortative mixing, are usually considered in previous studies. Assortative mixing means that nodes with similar degree tend to be connected, and disassortative mixing indicates that nodes with different degree are connected. However, since only a fraction q of nodes have dependency relationships in partially interdependent networks, it is necessary to redefine assortative and disassortative interdependence as following.

Random interdependence

Random interdependence means randomly selecting nodes from networks A and B, respectively, and setting up interdependent links between them.

Assortative interdependence: max–max and min–min

First, sort nodes in networks A and B in the descending order of node degree, respectively, then, in the case of max–max interdependence, bidirectional interdependent links are set up between the fraction q of high-degree nodes in A and the fraction q of high-degree nodes in B. While, in the mode of min–min interdependence, the fraction q of low-degree nodes in one network are preferentially dependent on low-degree nodes in other network.

Disassortative interdependence: max–min and min–max

Here, max–min and min–max stand for two different kinds of disassortative interdependence. Considering max–min interdependence between networks A and B, it means that bidirectional interdependent links exist between high-degree nodes in A and low-degree nodes in B. On the contrary, in the case of min–max interdependence, the fraction q of low-degree nodes in A depend on the fraction q of high-degree nodes in B and vice versa.

For simplicity, only symmetric and one-to-one interdependence is considered, and two networks are with the same numbers of nodes and links in this study. One-to-one interdependence indicates that node

• Network growth

The network evolves with m isolated nodes initially; then, at each time step

• Locally preferential attachment

At each time step t,

The adjustable parameter M controls the extent to which locally preferential mechanism takes effect. If M is equal to the size of existing network at each time step, which is indicated by

Iterative Process of Cascading Failures under Intentional Attacks

In reality, targeted attacks on vital nodes are usually considered as effective strategies to destroy networked systems rather than random attacks. Therefore, it is of practical significance to investigate the performance of interdependent systems against intentional attacks. In this study, high-degree nodes are deliberately selected and removed from the system. For simplicity, nodes only in one network are initially attacked. Take the system shown in Figure 1A as an example; if network A is selected as the target, intentional attack can be simulated by sorting all the nodes in the descending order of degree and sequentially removing the nodes with the highest degree from network A.

Because of the interdependence between networks, once a small fraction of nodes are removed from one network, the damage may not be limited therein. The cascading failures of nodes and links can propagate between networks, just resulting in the collapse of the entire system. Figures 1B–G illustrate the propagating process of cascading failures of nodes and links which are caused by the removal of node

Structural Vulnerability Metrics

Generally speaking, after one network suffers attack on nodes and/or links, the structural vulnerability can be evaluated from two aspects, the damage on connectivity integrity and the loss of communication efficiency. Several widely used robustness measures are listed as follows:

(1) S, relative size of the largest connected component

For an unconnected network, considering all the components, that is, the subnetworks of connected nodes, the largest connected component (LCC) represents the component which has the maximum number of connected nodes [44]. Let

(2) η, residual communication efficiency

Communication efficiency is an important quantity to characterize how efficiently the information is transmitted between node pairs over the whole network [45]. Assume that information is always exchanged along the shortest paths, let

(3)

The critical threshold

Numerical Simulation Results and Analysis

To explore the influence of both local-world mechanism and interdependence on structural vulnerability of interdependent systems, in the following numerical simulations, partially interdependent systems composed of two networks are established with different interdependence strength q and preference. According to the local-world evolving model, all the networks are constructed with different parameter M. Intentional attack is initiated by the removal of a fraction f of high-degree nodes in one network, indicated as the target network, which induces the cascading failures of nodes and links throughout both networks. When the system reaches the steady state after cascading failures, the damage on connectivity integrity and loss of communication efficiency of the target network are evaluated by monitoring the changes of S, η, and

Effect of Local-World Mechanism

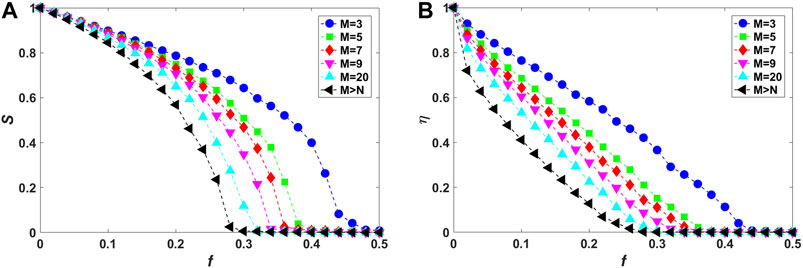

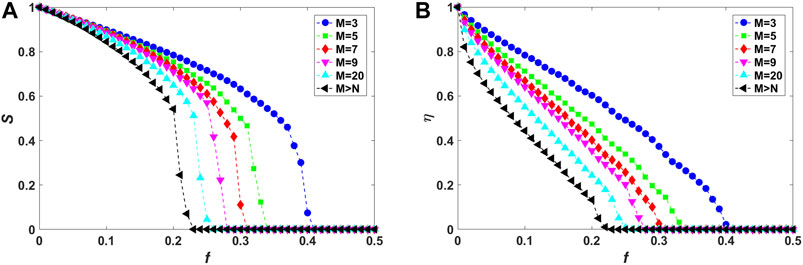

First, the influence of local-world mechanism on vulnerability of isolated networks is investigated, which is corresponding to the special case of strength

FIGURE 2. (Color online) Vulnerability analysis of isolated local-world networks (corresponding to interdependence strength

From Figure 2A, with the increasing of f, the values of S inevitably are reduced to near 0. However, S is observed to decline more sharply in networks with the increasing of M. The rapid decrease of the size of largest connected component implies that nodes break off from the main body and all the connected components break into small pieces quickly, just accelerating the collapse of the whole network. For example, at

Meanwhile, after cascading failures, the residual communication efficiency η of networks is also examined (Figure 2B). As more nodes are attacked and removed from the network, that is, η monotonically decreases, with the increasing of the fraction f of eliminated nodes. However, as M increases (from top to bottom), under the same level of external damage, that is, with the same f, η declines more rapidly in networks with higher values of M. For example, when

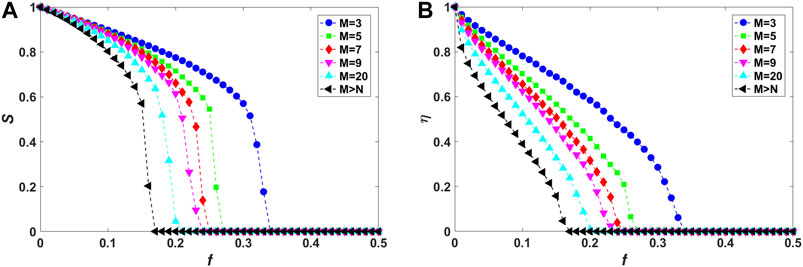

Second, the impact of local-world mechanism on structural vulnerability of fully interdependent local-world networks is also explored, which can be regarded as a special case of partially interdependent system with strength

Figures 3–5 show the relative size S of the largest connected component and the residual communication efficiency η as functions of the fraction f of initially removed high-degree nodes for fully interdependent local-world networks in the case of random, assortative and disassortative interdependence, respectively. It can be observed from Figures 3A, 4A, 5A that, as M is increased, the decline of S becomes more drastically with increasing f, implying that corresponding networks are more vulnerable against cascading failures. Also, as shown in Figures 3B, 4B, 5B, residual communication efficiency η decreases more rapidly in networks with higher values of M. Note that, these behaviors are consistent with those of isolated local-world networks (Figure 2).

FIGURE 3. (Color online) Vulnerability analysis of fully interdependent local-world networks (corresponding to interdependence strength

FIGURE 4. (Color online) Vulnerability analysis of fully interdependent local-world networks (corresponding to interdependence strength

FIGURE 5. (Color online) Vulnerability analysis of fully interdependent local-world networks (corresponding to interdependence strength

In summary, the simulation results demonstrate that the emergence of local worlds during network evolution has great influence on structural vulnerability of both single and interdependent networks. Deliberate attacks on highly connected nodes can induce more damage and sequentially more easily lead to abrupt collapse on networks with larger size M of local worlds. In other words, networks with larger size of local worlds are found to be more vulnerable against attacks.

Influence of Interdependence Preference

Previous study has verified that interdependent links accelerate the cascading spreading of node and link failures between networks, thus greatly enhancing the fragility of entire system against cascading failures [24]. This can be proved by the following observation of the simulation results. From Figures 3–5, compared with isolated networks (Figure 2), S decreases more drastically and

Considering the effect of different interdependence preference, systems with assortative interdependence (Figure 4) are found to be the most vulnerable resisting cascading failures compared with random (Figure 3) and disassortative (Figure 5) cases. As M is fixed, the relative size S declines most rapidly and drops to

Moreover, the effect of interdependence preference can also be verified by exploring the loss of communication efficiency induced by the elimination of nodes and links at the end of a cascading process. The changes of residual communication efficiency η versus the fraction f of initially removed high-degree nodes are shown in Figures 3B, 4B, 5B, which are corresponding to systems with random, assortative, and disassortative interdependence, respectively. In Figure 4B, for interdependent networks with assortative interdependence and local world size

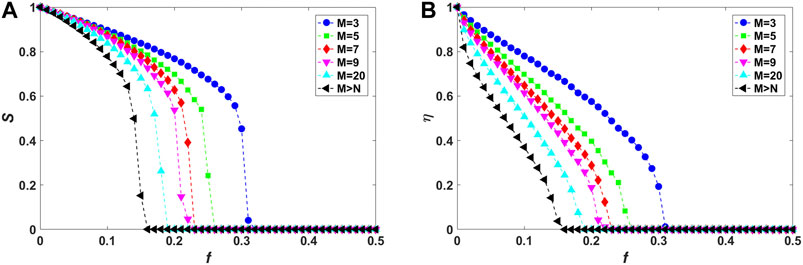

Impact of Interdependence Strength

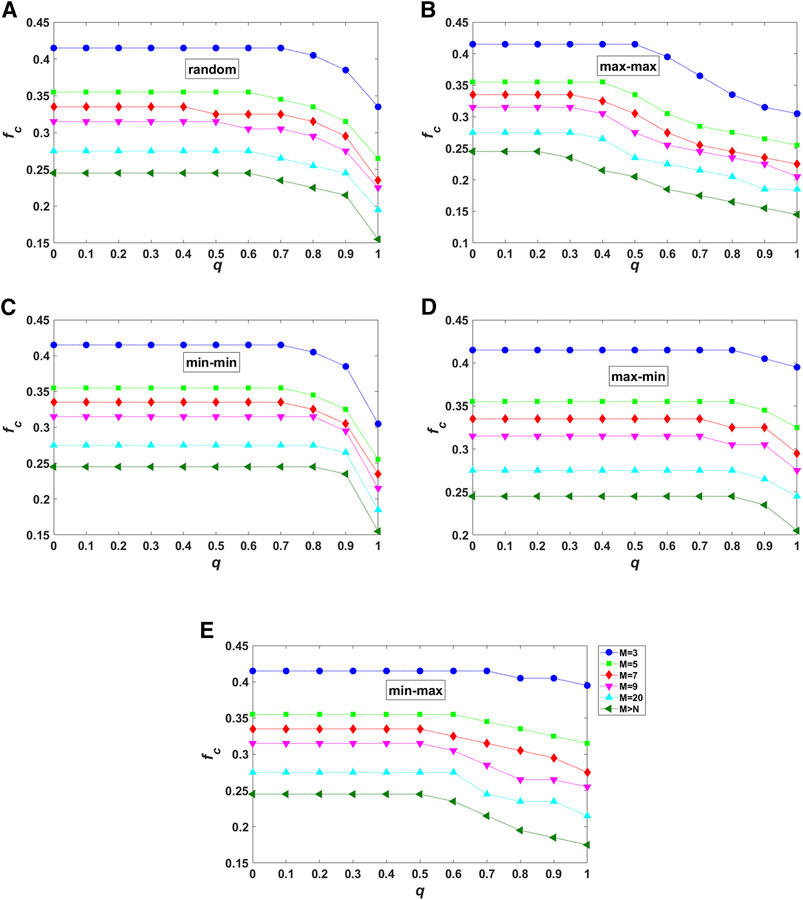

Sequentially, in the following simulations, the vulnerability of partially interdependent networks after cascading failures is investigated by monitoring the joint influence of interdependence strength q, interdependence preference, and local world size M on the values of critical node threshold

FIGURE 6. (Color online) Vulnerability analysis of partially interdependent local-world networks after cascading failures caused by intentional removal of high-degree nodes from one network. Both interdependence preference and strength are considered: (A)random; (B)max–max; (C)min–min; (D)max–min; (E)min–max. All the plots show the joint effect of interdependence strength q and local world size M on the critical threshold values of

In all the plots of Figure 6, from top (

Compared with random interdependence (Figure 6A),

As q is increased, for example,

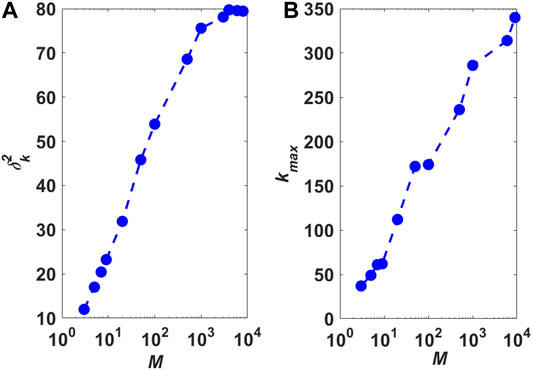

In previous studies, it has been revealed that node degree distribution and degree heterogeneity are essentially important for attack robustness of complex networks [46–49]. Two basic topological metrics,

FIGURE 7. (Color online) Heterogeneity analysis of node degree distribution of local-world evolving networks with different parameter M. (A)

The results in Figure 7 demonstrate that with the increasing of size M of local worlds, the local-world characteristic of the network decreases, especially when

Conclusion

To give a deep insight into the joint influence of interdependence and local worlds on complex interdependent networks with respect to the structural vulnerability after cascading failures, an interdependent system composed of two networks is established incorporating the consideration of both interdependence strength and preference. Especially, based on the local-world model, both networks are constructed with an adjustable parameter which controls the size of local worlds during network evolution. Through numerical simulations, it has been revealed that local-world mechanism can greatly affect the vulnerability of both isolated and interdependent networks. As the size of local world increases, corresponding networks are found to be more vulnerable after cascading failures induced by node removal. Additionally, the research results strongly verify that interdependent links can accelerate the collapse of the entire system. Comparing different interdependence preference, networks with max–max assortative interdependence are the most fragile against cascading failures. These results suggest that protecting highly connected nodes and weakening the interdependence between high-degree nodes can be effective for enhancing the robustness of interdependent systems. Especially, from the viewpoint of network evolution, controlling the extent of preferential attachment can be quite beneficial to preventing the drastic catastrophic failures of isolated and interdependent networks.

In this study, the investigation on network vulnerability against cascading failures is mainly focused on a simple binary networked system model, where links between nodes are only with two states, that is, present or absent. Nonetheless, most real-world networks are naturally weighted with some interaction values associated to the links (i.e., the link weight) [13, 44]. Thus, in the following work, the study on the relationships between local-world effect and network attack will be extended to weighted interdependent networks and real-world networks. Recently, many protection approaches have been developed to improve attack robustness and avoid abrupt collapse of complex systems, including setting reinforced nodes to support their neighborhood [50], targeted node recovery [51–53], and introducing node repair after collapse [54]. Therefore, local-world mechanism should be incorporated into the robustness improvement of interdependent systems, which remains as an interesting topic to be explored extensively. Moreover, several important dynamical behaviors, such as system crash behavior [36], epidemic dynamics [55] and structural controllability [56], have been extended into multiple networked systems. The effect of local worlds on these dynamic behaviors in interdependent systems deserves further study as well.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

JW and SS conceived and conducted the numerical experiments. LW and CX proposed the advice. All the authors analyzed the research results and together wrote the first version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is partially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin under Grant No. 18JCYBJC87800 and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 61773286.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions to improve the quality of our manuscript.

References

1. Albert, R, and Barabási, AL. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Rev Mod Phys (2002). 74:47–97. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.47

2. Newman, MEJ. The structure and function of complex networks. SIAM Rev (2003). 45:167–256. doi:10.1137/S003614450342480

3. Boccaletti, S, Latora, V, Moreno, Y, Chavez, M, and Hwang, D. Complex networks: structure and dynamics. Phys Rep (2006). 424:175–308. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2005.10.009

4. Barabási, AL, and Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science (1999). 286:509–12. doi:10.1126/science.286.5439.509

5. Erdős, P, and Rényi, A. On the evolution of random graphs. Publ Math Inst Hung Acad Sci (1960). 5:17–61. doi:10.1515/9781400841356.38

6. Li, X, Ying Jin, Y, and Chen, G. Complexity and synchronization of the world trade web. Phys Stat Mech Appl (2003). 328:287–96. doi:10.1016/S0378-4371(03)00567-3

7. Li, X, and Chen, G. A local-world evolving network model. Physica A (2003). 328:247–86. doi:10.1016/S0378-4371(03)00604-6

8. Ding, Y, Li, X, Tian, YC, Ledwich, G, Mishra, Y, and Zhou, C. Generating scale-free topology for wireless neighborhood area networks in smart grid. IEEE Trans Smart Grid (2019). 10:4245–52. doi:10.1109/TSG.2018.2854645

9. Xing, YF, Chen, X, Guan, MX, and Lu, ZM. An evolving network model for power grids based on geometrical location clusters. IEICE Trans Info Syst (2018). E101.D:539–42. doi:10.1587/transinf.2017EDL8177

10. Sun, M, Han, D, Li, D, and Fang, C. The general evolving model for energy supply-demand network with local-world. Int J Mod Phys C (2013). 24:1350070. doi:10.1142/S0129183113500708

11. Yang, GY, and Liu, JG. A local-world evolving hypernetwork model. Chin Phys B (2014). 23:018901. doi:10.1088/1674-1056/23/1/018901

12. Tian, L, He, Y, and Huang, Y. A novel local-world-like evolving bipartite network model. Acta Phys Sin (2012). 61:228903. doi:10.7498/aps.61.228903.

13. Li, P, Zhao, Q, and Wang, H. A weighted local-world evolving network model based on the edge weights preferential selection. Int J Mod Phys B (2013). 27:1350039. doi:10.1142/S0217979213500392

14. Zhang, Z, Rong, L, Wang, B, Zhou, S, and Guan, J. Local-world evolving networks with tunable clustering. Phys Stat Mech Appl (2007). 380:639–50. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2007.02.045

15. Xie, Z, Li, X, and Wang, X. A new community-based evolving network model. Phys Stat Mech Appl (2007). 384:725–32. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2007.05.031

16. Wang, LN, Guo, JL, Yang, HX, and Zhou, T. Local preferential attachment model for hierarchical networks. Phys Stat Mech Appl (2009). 388:1713–20. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2008.12.028

17. Mu, J, Zheng, W, Wang, J, and Liang, J. A novel edge rewiring strategy for tuning structural properties in networks. Knowl Base Syst (2019). 177:55–67. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2019.04.004

18. Sun, S, Liu, Z, Chen, Z, and Yuan, Z. Error and attack tolerance of evolving networks with local preferential attachment. Phys Stat Mech Appl (2007). 373:851–60. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2006.05.049

19. Sun, S, Liu, Z, Chen, Z, and Yuan, Z. On synchronizability of dynamical local-world networks. Int J Mod Phys B (2008). 22:2713–23. doi:10.1142/S0217979208039770

20. Xia, C, Liu, Z, Chen, Z, Sun, S, and Yuan, Z. Epidemic spreading behavior with time delay on local-world evolving networks. Front Electr Electron Eng China (2008). 3:129–35. doi:10.1007/s11460-008-0033-3. CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Bao, Zj, and Cao, Yj. Cascading failures in local-world evolving networks. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci (2008). 9:1336–40. doi:10.1631/jzus.A0820336

22. Wu, ZP, Guan, ZH, and Wu, X. Consensus problem in multi-agent systems with physical position neighbourhood evolving network. Phys Stat Mech Appl (2007). 379:681–90. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2006.12.026

23. Sun, S, Ma, Y, Wu, Y, Wang, L, and Xia, C. Towards structural controllability of local-world networks. Phys Lett (2016). 380:1912–17. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2016.03.048

24. Buldyrev, SV, Parshani, R, Paul, G, Stanley, HE, and Havlin, S. Catastrophic cascade of failures in interdependent networks. Nature (2010). 464:1025–28. doi:10.1038/nature08932

25. Kivelä, M, Arenas, A, Barthelemy, M, Gleeson, JP, Moreno, Y, and Porter, MA. Multilayer networks. Journal of Complex Networks (2014). 2:203–71. doi:10.1093/comnet/cnu016

26. Boccaletti, S, Bianconi, G, Criado, R, del Genio, CI, Gómez-Gardeñes, J, and Romance, M. The structure and dynamics of multilayer networks. Phys Rep (2014). 544:1–122. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2014.07.001

27. Li, J, Wang, Y, Huang, S, Xie, J, Shekhtman, L, Hu, Y, et al. Recent progress on cascading failures and recovery in interdependent networks. Internat J Disaster Risk Reduction (2019). 40:101266. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101266

28. Jiang, W, Liu, R, Fan, T, Liu, S, and Lu, L. Overview of precaution and recovery strategies for cascading failures in multilayer networks. Acta Phys Sin (2020). 69:088904. doi:10.7498/aps.69.20192000.

29. Albert, R, Jeong, H, and Barabási, AL. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature (2000). 406:378–82. doi:10.1038/35019019

30. Podobnik, B, Horvatic, D, Lipic, T, Perc, M, Buldú, JM, and Stanley, HE. The cost of attack in competing networks. J R Soc Interface (2015). 12:20150770. doi:10.1098/rsif.2015.0770

31. Qiu, T, Liu, J, Si, W, Han, M, Ning, H, and Atiquzzaman, M. A data-driven robustness algorithm for the internet of things in smart cities. IEEE Commun Mag (2017). 55:18–23. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2017.1700247

32. Zhou, M, and Liu, J. A two-phase multiobjective evolutionary algorithm for enhancing the robustness of scale-free networks against multiple malicious attacks. IEEE Trans Cybern (2016). 47:1–14. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2016.2520477

33. Lin, Y, Burghardt, K, Rohden, M, Noël, P-A, and D’Souza, RM. Self-organization of dragon king failures. Phys Rev E (2018). 98:022127. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.98.022127

34. Kornbluth, Y, Barach, G, Tuchman, Y, Kadish, B, Cwilich, G, and Buldyrev, SV. Network overload due to massive attacks. Phys Rev E (2018). 97:052309. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.97.052309

35. Yang, Y, Nishikawa, T, and Motter, AE. Vulnerability and cosusceptibility determine the size of network cascades. Phys Rev Lett (2017). 118:048301. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.048301

36. Yu, Y, Xiao, G, Zhou, J, Wang, Y, Wang, Z, Kurths, J, et al. System crash as dynamics of complex networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2016). 113:11726–31. doi:10.1073/pnas.1612094113

37. Yang, Y, Nishikawa, T, and Motter, AE. Small vulnerable sets determine large network cascades in power grids. Science (2017b). 358:eaan3184. doi:10.1126/science.aan3184

38. Duan, D, Lv, C, Si, S, Wang, Z, Li, D, and Gao, J. Universal behavior of cascading failures in interdependent networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2019). 116:22452–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1904421116

39. Cai, Y, Cao, Y, Li, Y, Huang, T, and Zhou, B. Cascading failure analysis considering interaction between power grids and communication networks. IEEE Trans Smart Grid (2016). 7:530–8. doi:10.1109/TSG.2015.2478888

40. Chen, Z, Wu, J, Xia, Y, and Zhang, X. Robustness of interdependent power grids and communication networks: a complex network perspective. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst II (2018). 65:115–19. doi:10.1109/TCSII.2017.2705758

41. Zhang, H, Peng, M, Guerrero, JM, Gao, X, Liu, Y, and Liu, Y. Modelling and vulnerability analysis of cyber-physical power systems based on interdependent networks. Energies (2019). 12:3439. doi:10.3390/en12183439

42. Zhou, D, and Bashan, A. Dependency-based targeted attacks in interdependent networks. Phys Rev E (2020). 102:022301. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.102.022301

43. Wu, Y, Sun, S, Wang, L, and Xia, C. Attack vulnerability of interdependent local-world networks: the effect of degree heterogeneity. In: Proc. IEEE IECON 2017 - 43rd Ann. Conf. of the IEEE Ind. Elect. Soc. 2017 (2017). p. 8763–7. doi:10.1109/IECON.2017.8217540

44. Bellingeri, M, Bevacqua, D, Scotognella, F, Alfieri, R, Nguyen, Q, Montepietra, D, et al. Link and node removal in real social networks: a review. Front Physiol (2020). 8:228. doi:10.3389/fphy.2020.00228

45. Latora, V, and Marchiori, M. Efficient behavior of small-world networks. Phys Rev Lett (2001). 87:198701. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.198701

46. Yuan, X, Shao, S, Stanley, HE, and Havlin, S. How breadth of degree distribution influences network robustness: comparing localized and random attacks. Phys Rev E (2015). 92:032122. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.92.032122

47. Sun, S, Wu, Y, Ma, Y, Wang, L, Gao, Z, and Xia, C. Impact of degree heterogeneity on attack vulnerability of interdependent networks. Sci Rep (2016). 6:32983. doi:10.1038/srep32983

48. Buldyrev, SV, Shere, NW, and Cwilich, GA. Interdependent networks with identical degrees of mutually dependent nodes. Phys Rev E (2011). 83:016112. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.83.016112

49. Zhou, D, Stanley, HE, D’Agostino, G, and Scala, A. Assortativity decreases the robustness of interdependent networks. Phys Rev E (2012). 86:066103. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.86.066103

50. Yuan, X, Hu, Y, Stanley, HE, and Havlin, S. Eradicating catastrophic collapse in interdependent networks via reinforced nodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2017). 114:3311–15. doi:10.1073/pnas.1621369114

51. Majdandzic, A, Podobnik, B, Buldyrev, SV, Kenett, DY, Havlin, S, and Eugene Stanley, H. Spontaneous recovery in dynamical networks. Nat Phys (2014). 10:34–8. doi:10.1038/NPHYS2819

52. Gong, M, Ma, L, Cai, Q, and Jiao, L. Enhancing robustness of coupled networks under targeted recoveries. Sci Rep (2015). 5:8439. doi:10.1038/srep08439

53. Zhou, D, and Elmokashfi, A. Network recovery based on system crash early warning in a cascading failure model. Sci Rep (2018). 8:1–9. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25591-6

54. Majdandzic, A, Braunstein, LA, Curme, C, Vodenska, I, Levy-Carciente, S, Eugene Stanley, H, et al. Multiple tipping points and optimal repairing in interacting networks. Nat Commun (2016). 7:1–10. doi:10.1038/ncomms10850

55. Wang, Z, Guo, Q, Sun, S, and Xia, C. The impact of awareness diffusion on sir-like epidemics in multiplex networks. Appl Math Comput (2019). 349:134–47. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2018.12.045

Keywords: interdependent networks, complex networks, structural vulnerability, cascading failures, local worlds, network attack

Citation: Wang J, Sun S, Wang L and Xia C (2020) Structural Vulnerability Analysis of Partially Interdependent Networks: The Joint Influence of Interdependence and Local Worlds. Front. Phys. 8:604595. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2020.604595

Received: 09 September 2020; Accepted: 29 September 2020;

Published: 17 November 2020.

Edited by:

Mahdi Jalili, RMIT University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Yongxiang Xia, Hangzhou Dianzi University, ChinaMichele Bellingeri, University of Parma, Italy

Copyright © 2020 Wang, Sun, Wang and Xia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shiwen Sun, c3Vuc3dAdGp1dC5lZHUuY24=

Jiawei Wang

Jiawei Wang Shiwen Sun

Shiwen Sun Li Wang1,2

Li Wang1,2