- 1ITAMP, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA, USA

- 2Physics Department, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Recently it has been shown that pairs of atoms can form metastable bonds due to non-conservative forces induced by dissipation [Lemeshko and Weimer, Nature Comm. 4, 2230 (2013)]. Here we study the dynamics of interaction-induced coherent population trapping—the process responsible for the formation of dissipatively bound molecules. We derive the effective dissipative potentials induced between ultracold atoms by laser light, and study the time evolution of the scattering states. We demonstrate that binding occurs on short timescales of ~10 μs, even if the initial kinetic energy of the atoms significantly exceeds the depth of the dissipative potential. Dissipatively-bound molecules with preordained bond lengths and vibrational wavefunctions can be created and detected in current experiments with ultracold atoms.

1. Introduction

Most realistic systems are “open,” i.e., coupled to a fluctuating environment, which, for sufficiently strong coupling strengths, is capable of fundamentally changing the system's properties. In some applications, such as quantum information (1) and coherent spectroscopy (2), the uncontrollable dissipation due to the environment results in decoherence, complicating preparation and read-out of quantum states. In other situations, the environment can lead to novel effects, such as enhanced efficiency of photosynthetic energy transfer in biological systems (3) and the localization transition in a spin coupled to a bosonic bath (4).

Apart from the fundamental perspective, understanding the effects of environment is crucial for practical applications, since many technologies operate in far-from-equilibrium conditions. In polyatomic systems, usually studied in chemistry and physics, acquiring such an understanding is challenged by the complexity of an underlying Hamiltonian and the uncontrollable nature of dissipation. However, a tremendous recent progress in designing controllable quantum settings paves the way to a detailed understanding of open quantum systems. For example, experimental setups based on ultracold atoms, quantum dots, and superconducting circuits, allow to engineer desired Hamiltonians and control couplings to the environment, thereby getting insight into the microscopic nature of dissipation (5–7). Moreover, the degree of control achieved in such experiments allows to make a step beyond studying the couplings between a system and its environment: recently it has been theoretically predicted that dissipation can be used as a resource for quantum state engineering (8–11). The method is based upon tuning the the properties of the dissipative bath and system-bath couplings in such a way that the driven dissipative system evolves toward a desired stationary state. The possibility of using dissipation for quantum state preparation has been recently demonstrated in experiments with cold trapped ions by Barreiro et al. (12).

In a recent paper (13) Lemeshko and Weimer demonstrated that controlled dissipation can be used to create metastable bonds between ultracold atoms. Remarkably, such “dissipatively-bound molecules” can be formed even if interparticle interactions are purely repulsive. An extension of this idea to many-particle systems allows to dissipatively prepare crystals of ultracold atoms in free space, i.e., without artificially breaking the translational symmetry with an optical lattice or harmonic trap (14). In this contribution, we focus on the effect of light-induced dissipation on the scattering properties of ultracold atoms. Using perturbation theory, we derive the effective dissipative potential energy curves, and study the time-evolution of the scattering states. We show that by appropriately tuning the couplings of the atoms to the environment one can create dissipatively-bound molecules with desired bond lengths and vibrational wavefunctions.

2. Materials and Methods

We consider a pair of ultracold atoms whose spatial motion is restricted to one dimension (1D) using an appropriate optical trap, see Figure 1A. Each atom possesses the electronic configuration shown in Figure 1B. Two fine or hyperfine components of the electronic ground state, |1〉 and |3〉, are coupled to an electronically excited state, |2〉, using two counter-propagating lasers with Rabi frequencies Ω. In alkali atoms, Ω corresponds to the laser-cooling transition, 2S1/2 ↔ 2P3/2. The field coupling states |2〉 and |3〉 is on resonance, while the other field is detuned by Δ from the |1〉 − |2〉 transition. For simplicity we assume that |2〉 decays to both ground states at the same spontaneous emission rate γ. The atoms are initially prepared in state |1〉, which is coupled to a highly-excited Rydberg state, |Ry〉, possessing a large dipole moment, using a two-photon transition ΩRy in presence of a weak external electric field (15–17). Dressing of state |3〉 can be avoided by making use of the dipole selection rules. If coupling to the Rydberg state is far-off-resonant, i.e., for the detuning ΔRy » ΩRy, one can adiabatically eliminate the state |Ry〉 and assign to state |1〉 an effective dipole moment d. As a result, state |1〉 exhibits a distance-dependent shift induced by the dipole-dipole interaction. On the other hand, states |2〉 and |3〉 have a zero dipole moment and therefore are non-interacting. We note that a similar setup can be realized based on laser-cooled molecules that possess nearly closed transitions (18–20), in which case the dipole-dipole interactions can be imposed by microwave dressing of rotational levels (21).

Figure 1. Setup of the system. (A) Ultracold atoms are confined in a one-dimensional optical trap. Two counter-propagating laser beams drive the electronic transitions with a Rabi frequency Ω. (B) Internal level structure of the atoms. Two components of the ground electronic state, |1〉 and |3〉, are coupled to an electronically excited state, |2〉, spontaneously decaying with a rate γ. The laser field coupling states |1〉 and |2〉 is detuned from the resonance by Δ; state |1〉 is provided with an effective dipole moment, d, via far-off-resonant Rydberg dressing, ΔRy » ΩRy. States |2〉 and |3〉 are non-interacting.

The Λ-configuration of Figure 1B, formed by two fields Ω, entails a dark state: on resonance, Δ = 0, the system is in a stationary state, |dark〉 = (|1〉 − |3〉)/, which cannot absorb photons and is therefore decoupled from light. This phenomenon is called coherent population trapping (CPT) (22) and has been used to trap atoms in a particular momentum state below a single photon recoil, so-called velocity selective CPT (VSCPT) (23, 24). In a system of two Rydberg-dressed atoms, the dipole-dipole interaction renders the detuning Δ dependent on the interatomic distance r. This results in interaction-induced CPT: at a particular “dark distance,” rd, the interaction shifts level |1〉 to resonance, effectively decoupling the atomic pair from photon absorption-emission. The resulting metastable state corresponds to a dissipation-induced interatomic bond, recently described by (13). In this section we derive the effective potentials corresponding to the non-conservative forces acting between ultracold atoms, which underly the formation of the dissipation-induced bonds.

A pair of ultracold atoms described above represents an open quantum system with the electromagnetic field acting as a reservoir. The system's dynamics is given by the quantum master equation for the density operator ρ (25):

with ħ Planck's constant. The coherent part of the dynamics is contained in the Hamiltonian accounting for the motion of the atoms, their interaction with the laser fields, and the dipole-dipole interactions,

Here, i = 1, 2, and k label the atoms and their corresponding momentum states, and Ũ(q) is the Fourier transform of the dipole–dipole interaction potential. The dissipative part of Equation (1) contains the rates γn = γ and jump operators cn = ∑k |k + Δkn, jn〉 〈2, k|in in the Lindblad form, responsible for the decay of each atom from state |2〉. The index in = 1, 2 runs over the two atoms, while jn = 1, 3 accounts for the two final states, and Δkn contains all possible values of the emitted photon's wave vector (26, 27).

In the regime of weak dissipation, Ω2/γ2 « 1, one can neglect the quantum jumps, i.e., the cnρc†n term of Equation (1). As a result, the dynamics of the system is described by an effective non-Hermitian Hamiltonian, Heff = H − iVd, containing a dissipative potential:

In this work we focus on ultracold atoms at sub-Doppler temperatures of ~1–10 microKelvin. In particular, the kinetic energy is considered to be small compared to the interaction between the atoms, which in turn is small compared to the laser Rabi frequency and the spontaneous decay rate, i.e., (ħk)2/2m « U(r), ħΔ « ħγ, ħΩ. As a first step, we derive the effective interatomic potentials in the limit of zero kinetic energy, i.e., the center-of-mass motion is considered to be cold enough in order to neglect the corresponding Doppler shifts; in this case the resulting effective potentials are independent of the relative momentum.

In a two-atom system, the fields Ω connect only the states symmetric against the particle exchange, therefore we reduce the manifold of relevant states to the following 6 levels: . In this basis, the interaction part of the two-atom Hamiltonian reads:

where U(r) gives the interaction between the atoms in state |11〉. Treating U(r) and ħΔ as perturbations, one can obtain the ground state, |ψ〉, of the Hamiltonian (4), which corresponds to the density operator ρ = ∑i, j ρij |ψ〉 〈ψ|. The complex dissipative potential Vd(r) can be derived as the total probability of photon absorption, i.e., as a sum of those density matrix elements ρij that correspond to the transitions |1〉 − |2〉 and |3〉 − |2〉 in each atom, multiplied by the photon scattering rate, Ω2/γ, and ħ. The resulting expression for Vd(r) reads:

where , and .

3. Results

In what follows, we assume the dipole-dipole interaction between the atoms, U(r) = d2/(4πϵ0r3), where d is the effective dipole moment of state |1〉 and ϵ0 is the vacuum permittivity. The distance at which the dipole-dipole interaction equals ħγ defines the characteristic radius, r0 = d2/3/(4πϵ0 ħγ)1/3, and Equation (5) can be rewritten as:

Here , and . The dissipative potential (6) possesses a minimum at the so-called “dark distance,” rd, where the photon scattering rate is significantly reduced,

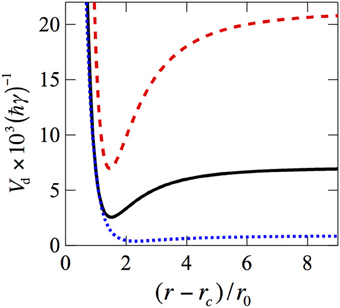

with , and . The value of rd, as well as the depth of the potential well, D = C6/r6d, can be tuned by changing the Rabi-frequency and the detuning of the laser fields. Figure 2 exemplifies the dissipative potentials for different values of Ω and Δ.

Figure 2. Examples of the dissipative potentials, Equation (6), for different values of parameters. Black solid line: Ω = γ/4, Δ = γ/20 (these values correspond to the results of Figures 3, 4); blue dotted line: Ω = γ/2, Δ = γ/40; red dashed line: Ω = γ/12, Δ = γ/20. The cutoff radius is set to rc = r0. The steady-state probability distributions corresponding to these potentials are shown in Figure 5.

The dynamics of the two-atom system is given by the Schrödinger equation in the center-of-mass frame:

Here the kinetic energy scales with the parameter α = ħ/(2mr20 γ), with m the reduced mass of the atomic pair. Note that Vd(r) occurs in Equation (8) with a minus sign, i.e., the distance rd corresponds to a reduced absorption of particles.

In order to study the time evolution of the scattering states, we solve Equation (8) numerically for different initial conditions. We exemplify the laser driving with the Rabi frequency Ω = γ/4 and detuning Δ = γ/20, which corresponds to Vd(r) shown in Figure 2 by the black solid line; this results in the dark distance rd = 2.5 r0. In order to simulate an experiment with a fixed particle density, we consider two particles confined in a box of length L = 14.5 r0. We set the kinetic energy parameter to α = 4· 10−4, and use a short-range cutoff, i.e., an impenetrable wall condition, for r < rc = r0. These values of parameters can be realized, e.g. with ultracold cesium atoms. In this case, two hyperfine components of the ground electronic state, 62S1/2, are chosen as states |1〉 and |3〉; state |1〉 is provided with an effective dipole moment d = 15 Debye due to Rydberg dressing in an external electric field. The laser field Ω drives the 62S1/2 ↔ 62P3/2 transition whose linewidth is γ = 2π × 5.2 MHz. This results in r0 = 186 nm, which corresponds to the three-dimensional atomic density of 4·1011 cm−3. In our calculation, the spatial grid is chosen such that the maximal value of the relative momentum kmax = 18.5/r0, which in the case of Cs corresponds to ~14 atomic recoil momenta.

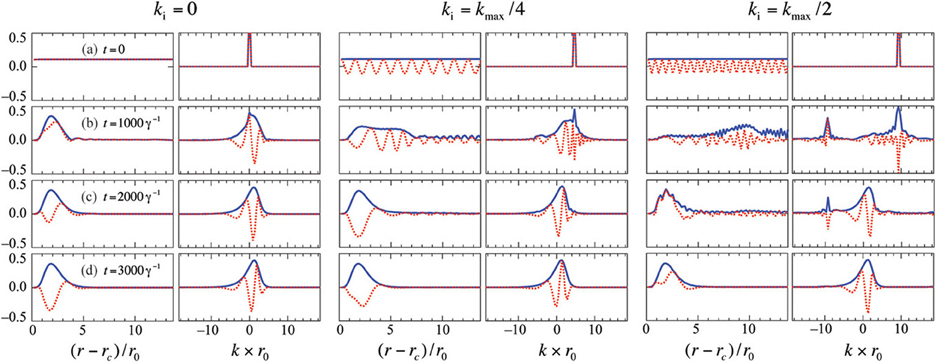

Figure 3 shows the time evolution of the scattering states starting from different initial relative momenta, ki. Three pairs of columns show the cases of ki = 0 (left panels), ki = kmax/4 (middle panels), and ki = kmax/2 (right panels). Within each pair, the left column shows the wave function in the position representation, ψ(r, t), while the right column shows its Fourier transform, giving the relative momentum distribution of the scattering state, ψ(k, t). One can see that in the long-time limit, panels (d), the driven-dissipative dynamics steers the pair of atoms toward the same steady state, independent of the initial conditions. The interplay between the kinetic energy term and the dissipative potential of Equation (8) results in a distribution of the relative distances around rd, and the relative momentum distribution peaked in the vicinity of k = 0. As a result, the dissipation-induced bond is formed. Similarly to conventional molecules bound by conservative forces (28), the distance and momentum distributions are asymmetric, which arises due to the anharmonicity of the dissipative potential, cf. Figure 2.

Figure 3. Absolute values (blue solid lines) and real parts (red dotted lines) of the scattering wavefunctions at times (a) t = 0; (b) t = 1000γ−1; (c) t = 2000γ−1; and (d) t = 3000γ−1. Pairs of columns show the wavefunctions in the position and momentum representation for different initial relative momenta: ki = 0 (left); ki = kmax/4 (middle); and ki = kmax/2 (right), with kmax = 18.5/r0. The cutoff radius rc = r0.

Note that the presented cases of ki = kmax/4 and ki = kmax/2 correspond to the initial kinetic energies of 9 × 10−3 ħ γ and 34 × 10−3 ħ γ, respectively, which significantly exceeds the depth of the dissipative potential well, cf. Figure 2. Interestingly, even in this case the formation of the dissipative bond occurs at a timescale comparable to the case of ki = 0. For a pair of Cs atoms, the unit of time γ−1 ≈ 30 ns, i.e., the timescales of the bond formation are on the order of 10–100 μs. Since the initial atomic wavefunctions of Figure 3(a) are completely delocalized in space, the bonding timescales are a few times longer compared to the ones obtained in Ref. (13).

The dynamics of the bond formation can be characterized by the imaginary binding energy. It is defined as the difference between the dissipation rate at t = 0, corresponding to atoms completely delocalized in space, and the dissipation rate at a given time t, when the molecules are formed:

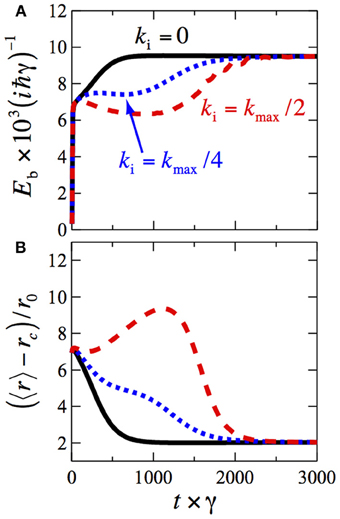

Figure 4A shows the time evolution of Eb starting from different initial conditions. At small times t the binding energy grows rapidly, due to strong dissipation at small interatomic distances that quickly pushes the population toward larger r. In the long-time limit, Eb approaches the value of 9.5 × 10−3iħγ, independently of the initial relative momentum. Note that while the qualitative behavior of Eb(t) does not depend on the details of the interatomic potential, the lower limit of the integral in Equation (9) is set by the short-range cutoff radius rc. The exact numerical value of Eb therefore depends on rc.

Figure 4. (A) Time-dependence of the imaginary binding energy of the molecules, Equation (9). (B) Time-dependence of the mean interatomic distance, Equation (10). Results for different initial relative momenta are shown: ki = 0 (black solid line), ki = kmax/4 (blue dotted line), and ki = kmax/2 (red dashed line), with kmax = 18.5/r0. The cutoff radius rc = r0.

The length of the dissipative bond is characterized by the mean interatomic distance,

whose time-evolution is shown in Figure 4B. In the long-time limit 〈r〉 approaches the value of 〈r〉 ≈ 3 r0 ≈ 1.2 rd.

4. Discussion

In this work we studied collisions of ultracold atoms in presence of dissipation due to near-resonant scattering of laser photons. The laser configuration is chosen such that dissipation is significantly reduced at some preordained interatomic distance rd, due to the interaction-induced coherent population trapping taking place. Working in the regime of small kinetic energy, we derived the effective, purely imaginary, interatomic potentials featuring minima at r = rd, whose shape can be tuned by changing the laser Rabi frequency and detuning.

Starting from the states with a particular value of the relative momentum, we studied the time evolution of the scattering wavefunctions. It was shown that, independently of the initial conditions, the driven-dissipative dynamics results in the steady state corresponding to a dissipatively-bound atomic pair, reached at the short timescales of ~10–100 μs. Interestingly, the bound states are formed even if the initial kinetic energy significantly exceeds the depth of the dissipative potential well. The dynamics of the dissipation-induced association was characterized by the time-dependent relative distance and momentum distributions, bond lengths, and imaginary binding energies.

The spectroscopic parameters of the dissipatively-bound molecules can be altered by tuning the laser parameters: the bond length scales with the effective dipole moment d due to Rydberg dressing, and with the detuning Δ; the binding energy (and therefore the shape of the vibrational wavefunction) depends on the photon scattering rate proportional to Ω2/γ. Figure 5A shows the vibrational probability distributions for molecules bound by the potentials shown in Figure 2; the panel (B) shows the corresponding momenta distributions. One can see that appropriately choosing the laser frequency and intensity makes it possible to prepare molecules with desired vibrational wavefunctions.

Figure 5. Steady states corresponding to the potentials of Figure 2. (A) Probability distribution of relative distances; (B) corresponding relative momenta distributions. Black solid line: Ω = γ/4, Δ = γ/20; blue dotted line: Ω = γ/2, Δ = γ/40; red dashed line: Ω = γ/12, Δ = γ/20. The cutoff radius rc = r0.

The relative distance distributions shown in Figures 3, 5A are proportional to the pair-correlation function, g(2)(r), that can be directly measured in experiment using a number of techniques such as noise correlation spectroscopy (29, 30) or Bragg scattering (31). The dissipative bond manifests itself as a peak emerging in g(2)(r) during the time evolution.

It is worth noting that dissipative binding occurs during the incoherent evolution of the scattering states, therefore its observation does not require long coherence times needed to observe the effects of the interactions on the coherent evolution of Rydberg-dressed atoms. The coherence times longer than the binding timescales of ~0.1 ms are achievable in current experiments (32–38).

The goal of this work was to develop a simple model allowing to understand the main features of dissipation-assisted scattering and the dynamics of interaction-induced coherent population trapping. The model is based on a few approximations whose limitations are worth discussing here. First, within the wavefunction approach that we employed, the system's state was assumed to be pure, as opposed to a mixed state resulting from the solution of the full master equation, Equation (1). Furthermore, the applied theory did not include quantum jumps that might quantitatively alter the relative momentum distribution in the steady-state, as well as the evolution times at which the steady state is reached. Finally, the internal and external degrees of freedom were decoupled from each other by introducing an effective interatomic potential, therefore the model does not provide information about the final population of the ground states |1〉 and |3〉. However, even with these approximations in place, the model is capable of capturing the physics of the system, as it is confirmed by a good agreement with the results of Ref. (13).

Finally, while in this work we focused on the realization based on Rydberg-dressed atoms (15–17), similar ideas can be applied to laser-cooled polar molecules (18–20, 39). Extensions to other types of interparticle interactions, such as magnetic dipole-dipole (40) and electric quadrupole-quadrupole (41) ones, also seem possible.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Hendrik Weimer and Johannes Otterbach for fruitful discussions.

Funding

The work was supported by the NSF through a grant for the Institute for Theoretical Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics at Harvard University and Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

References

1. Nielsen MA, Chuang IL. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2010).

3. Lambert N, Chen Y-N, Cheng Y-C, Li C-M, Chen G-Y, Nori F. Quantum biology. Nat Phys. (2012) 9:10–18. doi: 10.1038/nphys2474

4. Leggett A, Chakravarty S, Dorsey A, Fisher M, Garg A, Zwerger W. Dynamics of the dissipative two-state system. Rev Mod Phys. (1987) 59:1–85. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.59.1

5. Ladd TD, Jelezko F, Laflamme R, Nakamura Y, Monroe C, Brien JLOr. Quantum computers. Nat Phys. (2010) 464:45–53. doi: 10.1038/nature08812

7. Müller M, Diehl S, Pupillo G, Zoller P. Engineered open systems and quantum simulations with atoms and ions. Adv Atom Mol Opt Phys. (2012) 61:1–80. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396482-3.00001-6

8. Diehl S, Micheli A, Kantian A, Kraus B, Büchler HP, Zoller P. Quantum states and phases in driven open quantum systems with cold atoms. Nat Phys. (2008) 4:878–883. doi: 10.1038/nphys1073

9. Verstraete F, Wolf MM, Ignacio Cirac J. Quantum computation and quantum-state engineering driven by dissipation. Nat Phys. (2009) 5:633–636. doi: 10.1038/nphys1342

10. Weimer H, Müller M, Lesanovsky I, Zoller P, Büchler HP. A Rydberg quantum simulator. Nat Phys. (2010) 6:382–388. doi: 10.1038/nphys1614

11. Diehl S, Yi W, Daley AJ, Zoller P. Dissipation-induced d-wave pairing of fermionic atoms in an optical lattice. Phys Rev Lett. (2010) 105:227001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.227001

12. Barreiro JT, Müller M, Schindler P, Nigg D, Monz T, Chwalla M, et al. An open-system quantum simulator with trapped ions. Nature (2011) 470:486–491. doi: 10.1038/nature09801

13. Lemeshko M, Weimer H. Dissipative binding of atoms by non-conservative forces. Nat Commun. (2013) 4:2230. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3230

14. Otterbach J, Lemeshko M. Long-range crystalline order induced by dissipation. arXiv:1308.5905. (2013).

15. Henkel N, Nath R, Pohl T. Three-dimensional roton excitations and supersolid formation in Rydberg-excited Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys Rev Lett. (2010) 104:195302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.195302

16. Pupillo G, Micheli A, Boninsegni M, Lesanovsky I, Zoller P. Strongly correlated gases of Rydberg-dressed atoms: quantum and classical dynamics. Phys Rev Lett. (2010) 104:223002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.223002

17. Honer J, Weimer H, Pfau T, Büchler HP. Collective many-body interaction in Rydberg dressed atoms. Phys Rev Lett. (2010) 105:160404. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.160404

18. Stuhl BK, Sawyer BC, Wang D, Ye J. Magneto-optical trap for polar molecules. Phys Rev Lett. (2008) 101:243002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.243002

19. Shuman ES, Barry JF, Demille D. Laser cooling of a diatomic molecule. Nature (2010) 467:820–823. doi: 10.1038/nature09443

20. Manai I, Horchani R, Lignier H, Pillet P, Comparat D, Fioretti A, et al. Rovibrational cooling of molecules by optical pumping. Phys Rev Lett. (2012) 109:183001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.183001

21. Lemeshko M, Krems RV, Weimer H. Nonadiabatic preparation of spin crystals with ultracold polar molecules. Phys Rev Lett. (2012) 109:035301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.035301

22. Gray HR, Whitley RM, C R Stroud J. Coherent trapping of atomic populations. Opt Lett. (1978) 3:218–220. doi: 10.1364/OL.3.000218

23. Aspect A, Arimondo E, Kaiser R, Vansteenkiste N, Cohen-Tannoudji C. Laser cooling below the one-photon recoil energy by velocity-selective coherent population trapping. Phys Rev Lett. (1988) 61:826–829. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.61.826

24. Aspect A, Arimondo E, Kaiser R, Vansteenkiste N, Cohen-Tannoudji C. Laser cooling below the one-photon recoil energy by velocity-selective coherent population trapping: theoretical analysis. J Opt Soc Am. B (1989) 6:2112–2124. doi: 10.1364/JOSAB.6.002112

25. Breuer HP, Petruccione F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2002).

26. Dalibard J, Castin Y, Mølmer K. Wave-function approach to dissipative processes in quantum optics. Phys Rev Lett. (1992) 68:580–583. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.580

27. Mølmer K, Castin Y, Dalibard J. Monte Carlo wave-function method in quantum optics. J Opt Soc Am. B (1993) 10:524. doi: 10.1364/JOSAB.10.000524

28. Herzberg G. Molecular spectra and molecular structure: I. spectra of diatomic molecules; II. infrared and Raman spectra of polyatomic molecules; III. electronic spectra and electronic structure of polyatomic molecules. Krieger; 1989.

29. Altman E, Demler E, Lukin MD. Probing many-body states of ultracold atoms via noise correlations. Phys Rev. A (2004) 70:013603. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.70.013603

30. Fölling S, Gerbier F, Widera A, Mandel O, Gericke T, Bloch I. Spatial quantum noise interferometry in expanding ultracold atom clouds. Nature (2005) 434:481–484. doi: 10.1038/nature03500

31. Stamper-Kurn DM, Chikkatur AP, Görlitz A, Inouye S, Gupta S, Pritchard DE, et al. Excitation of phonons in a Bose-Einstein condensate by light scattering. Phys Rev Lett. (1999) 83:2876–2879. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.2876

32. Löw R, Weimer H, Nipper J, Balewski JB, Butscher B, Büchler HP, et al. An experimental and theoretical guide to strongly interacting Rydberg gases. J Phys. B (2012) 45:113001. doi: 10.1088/0953-4075/45/11/113001

33. Schempp H, Günter G, Hofmann CS, Giese C, Saliba SD, DePaola BD, et al. Coherent population trapping with controlled interparticle interactions. Phys Rev Lett. (2010) 104:173602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.173602

34. Pritchard JD, Maxwell D, Gauguet A, Weatherill KJ, Jones MPA, Adams CS. Cooperative atom-light interaction in a blockaded Rydberg ensemble. Phys Rev Lett. (2010) 105:193603. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.193603

35. Nipper J, Balewski JB, Krupp AT, Butscher B, Löw R, Pfau T. Highly resolved measurements of Stark-tuned Förster Resonances between Rydberg atoms. Phys Rev Lett. (2012) 108:113001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.113001

36. Dudin YO, Kuzmich A. Strongly interacting Rydberg excitations of a cold atomic gas. Science (2012) 336:887–889. doi: 10.1126/science.1217901

37. Peyronel T, Firstenberg O, Liang QY, Hofferberth S, Gorshkov AV, Pohl T, et al. Quantum nonlinear optics with single photons enabled by strongly interacting atoms. Nature (2012) 488:57–60. doi: 10.1038/nature11361

38. Schauß P, Cheneau M, Endres M, Fukuhara T, Hild S, Omran A, et al. Observation of spatially ordered structures in a two-dimensional Rydberg gas. Nature (2012) 491:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature11596

39. Lemeshko M, Krems R, Doyle J, Kais S. Manipulation of molecules with electromagnetic fields. Mol Phys. (2013) arXiv:1306.0912. doi: 10.1080/00268976.2013.813595

40. Lu M, Burdick N, Youn S, Lev B. Strongly dipolar Bose-Einstein condensate of dysprosium. Phys Rev Lett. (2011) 107.

Keywords: ultracold atoms, cold controlled collisions, coherent population trapping, dark state, dissipative preparation of quantum states, dissipatively-bound molecules, non-Hermitian Hamiltonian, Rydberg dressing

Citation: Lemeshko M (2013) Manipulating scattering of ultracold atoms with light-induced dissipation. Front. Physics 1:17. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2013.00017

Received: 02 August 2013; Paper pending published: 23 August 2013;

Accepted: 16 September 2013; Published online: 08 October 2013.

Edited by:

Alkwin Slenczka, Universität Regensburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Jens Riedel, BAM Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing, GermanyIlya Averbukh, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel

Copyright © 2013 Lemeshko. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mikhail Lemeshko, ITAMP, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, MS-14, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA e-mail:bWlraGFpbC5sZW1lc2hrb0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Mikhail Lemeshko

Mikhail Lemeshko