94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol., 03 March 2025

Sec. Inflammation Pharmacology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2025.1515864

Atrial fibrillation (AF), a common cardiac arrhythmia, is associated with severe complications such as stroke and heart failure. Although the precise mechanisms underlying AF remain elusive, inflammation is acknowledged as a pivotal factor in its progression. Angiotensin II (AngII) is implicated in promoting atrial remodeling and inflammation. However, the exact pathways through which AngII exacerbates AF are still not fully defined. This study explores the key molecular mechanisms involved, including dysregulation of calcium ions, altered connexin expression, and activation of signaling pathways such as TGF-β, PI3K/AKT, MAPK, NF-κB/NLRP3, and Rac1/JAK/STAT3. These pathways are instrumental in contributing to atrial fibrosis, electrical remodeling, and increased susceptibility to AF. Ang II-induced inflammation disrupts ion channel function, resulting in structural and electrical remodeling of the atria and significantly elevating the risk of AF. Anti-inflammatory treatments such as RAAS inhibitors, colchicine, and statins have demonstrated potential in reducing the incidence of AF, although clinical outcomes are inconsistent. This manuscript underscores the link between AngII-induced inflammation and the development of AF, proposing the importance of targeting inflammation in the management of AF.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the most common persistent arrhythmias encountered in clinical practice. It is strongly linked to conditions such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure, all of which exacerbate its prevalence with advancing age (Krijthe, B.P. et al., 2013; Schnabel, R.B. et al., 2015). AF is associated with severe complications, including thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, and the worsening of heart failure (Staerk et al., 2017; Catanese and Hart, 2019). Despite its prevalence, the underlying mechanisms of AF are not completely understood.

In AF, the atrial myocardium becomes hyperexcitable with a shortened refractory period, often triggered by ectopic atrial activity and reentry pathways. These mechanisms contribute to both electrical and structural remodeling (Iwasaki et al., 2011; Allessie et al., 2002), with angiotensin II (Ang II) playing a crucial role.

Ang II, a central component of the renin-angiotensin system, is frequently elevated in pathological conditions. It stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species, and promotes inflammation, fibrosis, and apoptosis through multiple pathways mediated by the AT1 receptor, a G-protein-coupled receptor. These processes result in significant electrical and structural alterations in the atria, thereby exacerbating fibrosis and accelerating the progression of AF (Forrester et al., 2018).

Extensive research indicates that Ang II is crucial in initiating key inflammatory processes. It increases vascular permeability, initiates inflammation, recruits inflammatory cells, and activates immune responses through chemotaxis and differentiation (Yusuke et al., 2003). Further studies suggest that Ang II not only induces inflammation but also impacts ion channels and currents, contributing to the atrial electrical and structural remodeling seen in AF (Jia et al., 2012).

Inflammation plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of AF by promoting the accumulation of inflammatory mediators in the atrial tissue, impacting both its structural and electrical properties (Vyas et al., 2020). Elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as CRP, interleukins (ILs), TNF, TGF-β, NF-κB, and NLRP3 have been observed in patients with AF (Sinner et al., 2014; Brezinov et al., 2021; Gungor et al., 2013; Allah et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2015; Guo, 2019; Deng et al., 2011; Lu, 2024; Xu et al., 2022; Yao C. et al., 2018). These factors disrupt electrical conduction by altering calcium homeostasis and connexins, thus increasing susceptibility to AF. Additionally, inflammatory mediators influence signaling pathways that promote atrial fibrosis (Hu et al., 2015; Hoffmann et al., 2016).

The interplay between inflammation, Ang II, and AF is intricate. While the influence of inflammation on Ang II-mediated signaling in AF is recognized, it is not yet fully elucidated. This article systematically reviews recent research on the key inflammatory pathways influenced by Ang II in AF and examines the roles of various inflammatory factors. Targeting these inflammatory pathways may offer novel insights into contemporary anti-inflammatory molecular mechanisms.

Ang II plays a pivotal role in atrial electrical remodeling by modulating ion channels and currents, thereby substantially contributing to the development of AF. Via the AT1R, AngII increases intracellular sodium levels and enhances sodium-calcium exchange. This activity stimulates calcium-dependent potassium and chloride channels, effectively shortening the atrial refractory period (Iwasaki et al., 2011). Furthermore, AngII facilitates the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, thereby shortening the duration of the action potential (Nakashima and Kumagai, 2007).

Ang II is implicated in the upregulation of T-type calcium currents and the inhibition of L-type channels, thereby shortening the plateau phase of the action potential, which promotes rapid atrial excitation and facilitates atrial remodeling (Tsai et al., 2007). It also impacts potassium currents by inhibiting Ito and Ikur, while amplifying Ik1. These changes degrade structural proteins and alter potassium channel expression (Gu et al., 2014; Brundel et al., 2002). Additionally, Ang II induces atrial insufficiency and aberrant Ca2+ handling in AF models through the activation of CaMKII, which modulates RyR2 and results in Ca2+ leakage (Aonuma et al., 2022). Activation of CaMKII also increases CREB phosphorylation, enhancing the transcription of KCNJ2 and CACNA1C. This upregulation impacts both potassium and calcium channels, further promoting AF (Li et al., 2024).

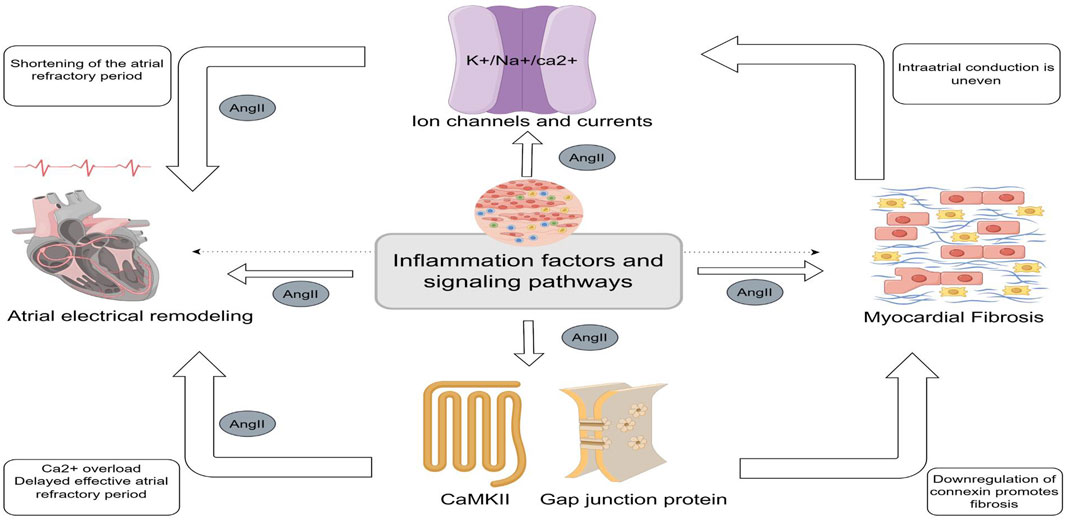

As a well-documented pro-fibrotic agent, AngII’s interaction with the AT1R promotes myocardial fibrosis through multiple signaling pathways. This fibrosis contributes to intra- and inter-atrial conduction inhomogeneities, creating localized zones of refractoriness and a substrate conducive to the progression of AF (Li et al., 1999). This process is closely linked to inflammation (Jia et al., 2012). Moreover, higher levels of AngII correlate with more severe atrial fibrosis and a higher incidence of AF (Jansen et al., 2019). Ang II and inflammation drive atrial electrical remodeling and fibrosis by modulating ion channel function, thereby exacerbating atrial structural and electrical abnormalities (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Central illustration (By Figdraw). Central role of inflammation in Angiotensin II- Induced Atrial Fibrillation. Inflammatory factors and inflammatory signaling pathways can contribute to atrial fibrillation by modulating ion channels and ion currents, calmodulin, and gap junction proteins to promote shortening and delaying of the effective atrial opriod. Myocardial fibrosis is the result of the co-regulation of Angiotensin II and multiple inflammatory signaling pathways. Fibrosis can lead to heterogeneous electrical signaling in the atria, affecting ion channels and currents and contributing to the occurrence of electrical remodeling.

Atrial electrical remodeling encompasses alterations in ion channel remodeling, ion current properties, and gap junction proteins, with inflammation playing a significant role in these processes (Ma et al., 2018). During experiments involving rapid atrial pacing in dogs, there is an observed increase in the expression of KCa3.1, a channel that regulates the repolarization phase of the cardiac action potential. This upregulation is mediated by the inflammation-related PI3K/AKT pathway (Yuntao et al., 2024). Inhibition of KCa3.1 has been shown to reduce macrophage polarization and prevent AF during sustained rapid pacing (He et al., 2021).

Furthermore, NF-κB activation induces its translocation to the nucleus, where it regulates the transcription of the KCa3.1 gene. Inhibiting NF-κB can attenuate the associated inflammation (Chen H et al., 2024). The interaction between RyR2 and CaMKII influences calcium transients and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release, while the NLRP3/IL-1β pathway activates Ca2+/CaMKII, inducing Ca2+ release and arrhythmia. Increased CaMKII activity has been found to inhibit PI3K/AKT signaling, elevating the risk of AF (Shuai et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2019).

Gap junction proteins such as Cx40 and Cx43, which are essential for cardiomyocyte coupling, are downregulated in inflammatory states. This downregulation alters atrial structure and conduction, promoting AF (Sawaya et al., 2007; Friedrichs et al., 2011). CX43 hemichannels mediate peripheral inflammatory signals, triggering the release of pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-1β and TNF-α (Ahmad et al., 2012). AngII may inhibit Cx43 by decreasing AMPK phosphorylation via KATP channels and activates p38, which overphosphorylates Cx43, disrupting cellular coupling and electrical remodeling (Wang, 2023). The inhibition of Cx43 attenuates JNK signaling and reduces the release of inflammatory mediators (Tien et al., 2021). Additionally, Cx43 hemichannels are involved in NLRP3 vesicle assembly and activation; the Cx43 inhibitor Gap26 has been shown to reduce inflammation markers (Wang WB et al., 2022). The involvement of ion channels and gap junction proteins in atrial electrical remodeling and fibrosis is illustrated in Figure 1.

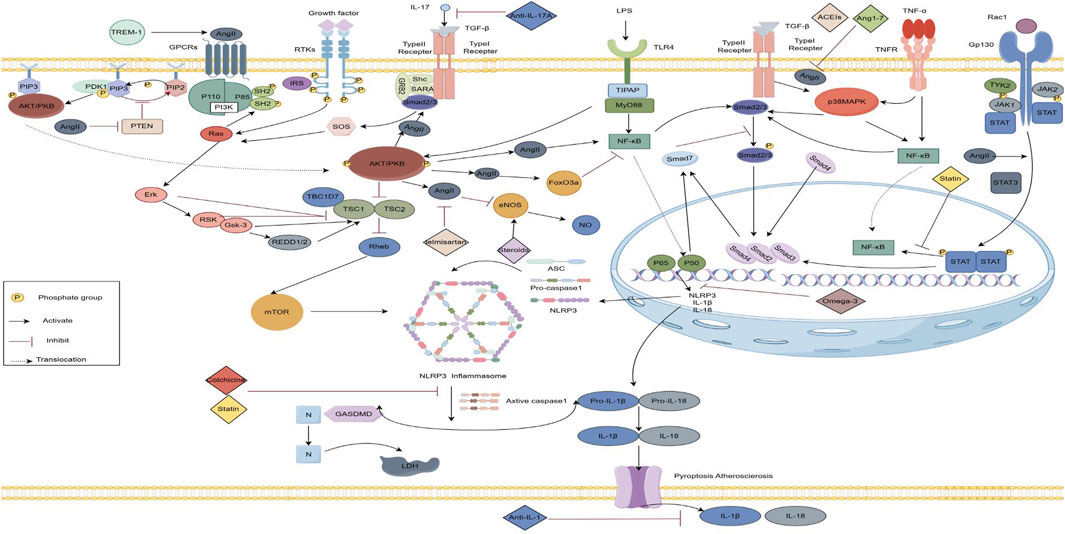

Atrial myocardial fibrosis, a defining feature of structural remodeling in AF, arises from a complex interplay of pro-fibrotic signaling pathways, inflammation, and oxidative stress (Tan and Zimetbaum, 2011). AngII plays a central role in these processes by engaging G-protein-coupled receptors to initiate various signaling cascades involved in intracellular, nuclear, and extracellular inflammatory responses. Figure 2 illustrates the interplay of inflammatory pathways.

Figure 2. Inflammatory crosstalk and anti-inflammatory mechanisms in the angiotensin II-induced fibrosis pathway. (By Figdraw) AngII mediates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and participates in upstream PTEN, downstream TGF-ß, m TOR, FoxO3a and e NOS signaling pathways, as well as the P38MAPK, JAK/STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways, and NF-κB further activates the NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles, releasing IL-1ẞ, IL-18.Anti-inflammatory drugs act on the corresponding inflammatory pathways. TLR, Toll-like Receptor; IGF 1, Insulin-like growth factor 1 ;TNF, Tumor necrosis factor; TGF-B, Transforming growth factor-ß; IL, Interleukins; PI3K,Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase;PIP3,Phosphatidylinositol Trisphosphate;PDK,Phosphatidylinositol-dependent kinase;FoxO3a, Forkhead box 03;mTOR, The Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin;e NOS,Endothelial nitric oxide synthas;JAK,Janus tyrosine Kinase;STAT,Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa-B protein;NLRP3, NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3.

The TGF-β signaling pathway, critical for regulating cellular proliferation, differentiation, immune responses, extracellular matrix synthesis, and inflammation, acts as a potent chemokine for cardiac fibroblasts. It promotes myocardial fibrosis by facilitating collagen deposition and suppressing its degradation (Xiao and Zhang, 2008). IL-17 enhances AngII-induced proliferation of atrial fibroblasts and fibrosis by upregulating TGF-β1 (Zhang, 2017). The TGF-β1/Smad pathway, integral to myocardial fibrosis, is regulated by the activation of AngII, NF-κB, and PI3K pathways (Hirsh et al., 2015). TGF-β1 synthesized by fibroblasts binds to TβRI/TβRII receptors, initiating a cascade that transmits signals to the nucleus via Smad proteins. Paced rabbit heart tissues show elevated levels of AngII, TGF-β1, and phosphorylated Smad2/3, alongside reduced Smad7, a critical negative regulator (He et al., 2011). Melatonin inhibits AngII-mediated TGF-β/Smad signaling, influencing atrial remodeling and AF (Xie et al., 2022). Additionally, GPR30 mitigates AngII-induced fibrosis by upregulating Smad7 expression (Liu et al., 2022).

This pathway is central to inflammatory responses, linked to mediators like NLRP3, interleukins, and TNF-α (Guo et al., 2012). Dog studies with AF show reduced mRNA levels of PI3K/AKT in atrial tissues, alongside increases in TNF-α, IL-6, XO, and ROS in peripheral blood (Stark et al., 2015). Both mRNA and protein expressions of PI3K and p-AKT are downregulated in myocardial tissues of rats, where inflammatory factors are notably elevated, exacerbating myocardial fibrosis (Kang, 2019). AngII activates PI3K/AKT via GPCRs, promoting myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis. LY294002, a PI3K/AKT inhibitor, reduces AngII-induced inflammation and myocardial fibrosis by lowering IL-6 and TNF-α levels (Zhu et al., 2024).

PTEN, an upstream regulator of PI3K-AKT, when degraded, enhances cardiac hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis (Cao et al., 2019). Liraglutide moderates AngII-induced proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition via the miR-21/PTEN/PI3K pathway (Wang et al., 2023). The immunoproteasome subunit PSMB10 alleviates myocardial fibrosis by reducing PTEN degradation and suppressing AKT1 activation (Li et al., 2018). The mTOR pathway downstream of PI3K/AKT contributes to fibrosis by promoting collagen production and myofibroblast transformation (Wu et al., 2021; Luo, 2023). Rapamycin, by inhibiting mTOR, diminishes inflammation and reverses cardiac remodeling (Liang, 2023). The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway also activates NLRP3 inflammasomes, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18 (Tai et al., 2022). FoxO3a, targeted by AKT, is upregulated in AngII-induced cardiac fibroblasts, fostering labile AF through enhanced fibrosis (Lin et al., 2024). FoxO3a knockdown markedly reduces fibroblast proliferation, migration, and collagen secretion (Lin et al., 2024). IGF-1R promotes myocardial fibrosis through activation of the PI3K/Akt/FoxO3a signaling pathway and predisposes to AF development and maintenance (Zhang, 2024). TREM-1 activation enhances susceptibility to AF by modulating the PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a signalling pathway to mediate inflammation production and release (Chen X et al., 2024). In diabetic rats, atrial fibrosis correlates with the inactivation of the PI3K/AKT/eNOS axis (Chu, 2015), while H2S modulates this pathway to alleviate fibrosis (Xue et al., 2020). Furthermore, the PI3K/AKT pathway triggers the TGF-β/Smad pathway, contributing to myocardial fibrosis.

MAPKs, serine/threonine kinases, are pivotal in cellular processes like proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The MAPK signaling cascade, consisting of MAPK, MAPKK, and MAPKKK, is activated by AngII binding to AT1R, stimulating fibroblast proliferation and inducing cellular hypertrophy and apoptosis. Elevated AngII levels, via TNF-α, prompt ROS release, activating the ASK1/MEKK3/6 pathway, which in turn activates p38MAPK, ERK, and JNK pathways, increasing protein synthesis and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Yu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2019). IL-17A activates the p38MAPK and ERK1/2 pathways, enhancing fibroblast proliferation and migration (Valente et al., 2012). p38MAPK is crucial in activating inflammatory pathways, regulating cytokine expression and increasing MMP1 mRNA levels, exacerbating myocardial fibrosis (Reunanen et al., 2002). Phosphorylated p38 protein expression in atrial tissues correlates with increased myofibroblast numbers (Shintaro et al., 2020). Laccase ameliorates left atrial dilatation, inflammation, and fibrosis by modulating the p38MAPK/Smad3 pathway (Liu et al., 2019). The antifibrotic drug c-Ski reduces p38MAPK phosphorylation and exerts antifibrotic effects (Han et al., 2021).

Rac1, a small GTP-binding protein of the Rho GTPase superfamily, induces myocardial ROS production through NADPH oxidase activation, increasing oxidative stress, inflammation, and collagen accumulation, which facilitates the development of AF (Adam et al., 2007). Rac1 participates in the Ang II-mediated JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway, upregulating the expression of type I procollagen α1 (COL1A1) and contributing to myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis (Hattori et al., 2006). Furthermore, AngII activates Rac1, which upregulates connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), N-cadherin, and Cx43 (Adam et al., 2010). CTGF is pivotal in extracellular matrix remodeling and tissue fibrosis (Perbal, 2004). The increased expression and redistribution of Cx43 and N-cadherin may impair atrial electrical conduction and promote interstitial fibrosis (Rucker-Martin et al., 2006). Rac1 also activates the Rac1/ASK1/NF-κB pathway, inducing cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and structural changes in the heart (Hirotani et al., 2002).

STATs, nuclear transcription factors, are integral to the JAK/STAT pathway and are closely associated with pathways like MAPK, NF-κB, TGF-β/Smad, and integrin/ERK. In atrial myocytes, AngII may activate STAT3 via Rac1 or a JAK/TYK-independent mechanism. In atrial fibroblasts, AngII-induced STAT1 activation requires Rac3-mediated autocrine or paracrine signaling (Ausma et al., 2008; Tsai et al., 2008). Rac1 membrane translocation and STAT3 activation drive structural remodeling and inflammatory responses in pacing-induced persistent AF. AngII also activates STAT3 by binding to the AT1 receptor, promoting the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1) and MMP-2 in atrial fibroblasts (Zheng et al., 2014). STAT3 further promotes Smad2/3 expression, contributing to fibrosis (Li, 2019). Inflammatory factors like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-4 activate and regulate the JAK-STAT pathway, influencing cardiac hypertrophy and myocardial remodeling (Butler et al., 2006; Dawn et al., 2004; Fischer and Hilfiker-Kleiner, 2008). Additionally, anti-inflammatory factors IL-10 and IL-11 mitigate fibrosis, prevent apoptosis, and reduce inflammatory responses by activating STAT3 (Krishnamurthy et al., 2009; Obana et al., 2010).

NF-κB, a key intracellular transcription factor, is activated by pro-inflammatory stimuli like TNF-α, IL-1, and bacterial products such as LPS. It induces the expression of genes encoding various cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, IFN-β, TNF-α, G-CSF, GM-CSF), enhancing the inflammatory response (Hu et al., 2018). NF-κB and TNF-α protein expression, along with inflammatory cell infiltration, were significantly elevated in the atrial tissues of patients with atrial fibrillation and in rats (Fan and Xue, 2012). Activated NF-κB induces myocardial fibrosis by promoting PICP production, modulating collagen tension, and reducing type I collagen accumulation (Fan, 2014). TNF-α also activates the NF-κB signaling pathway, promoting lung fibrosis in mice (Di et al., 2009). Toll-like receptors (TLRs) bind to MyD88, activating NF-κB, which triggers transcription and synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, contributing to the immune-inflammatory response (Lee et al., 2016). Clinical studies show higher expression levels of NF-κB, TLR4, and MyD88-related molecules in AF patients compared to healthy individuals (Xu et al., 2018). High-fat diets increase susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias by activating the TLR4/MyD88/CaMKII/NF-κB pathway, resulting in left ventricular hypertrophy, fibrosis, and reduced ion channel protein expression (Shuai et al., 2019). TLR4 antagonists prevent myocardial fibrosis by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88 pathway (Mian et al., 2019).

NLRP3, a downstream component of NF-κB, is a multiprotein complex composed of NLRP3, pro-caspase-1, and ASC, abundantly expressed in cardiac fibroblasts (Guan et al., 2022). Recognition of stressors like TRAF6 and TLR-mediated activation of NF-κB upregulates inflammatory vesicle-associated proteins, including IL-1β and IL-18. This process involves monomer assembly into a complex and the conversion of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms, mediating inflammatory responses (Celias et al., 2019). The NLRP3/IL-1β pathway induces inflammation through ROS production, with ROS acting as secondary messengers to promote further inflammation (Checa and Aran, 2020). The activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in atrial cardiomyocytes initiates a fibroinflammatory cascade involving cardiomyocytes, immune cells, and fibroblasts, thereby driving atrial fibrosis, remodeling, and the progression of AF (Dzeshka et al., 2015). These vesicles promote cytokine and collagen production by myofibroblasts, contributing to structural remodeling, RyR2 channel remodeling, atrial enlargement, stromal fibrosis, and abnormal gap junction protein distribution via RYR2 upregulation (Li and Brundel, 2020; Li et al., 2020). These abnormalities occur through the NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway. Elevated NLRP3 and IL-1β levels have been observed in aged rat atria with AF, linked to increased TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway activation. Blockade of TRPV4 prevents AF and reduces fibrosis in aseptic pericardial mice by inhibiting the ERK/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway (Yang et al., 2022; Zhang H et al., 2022). Furthermore, the NLRP3/IL-1β/MyD88 pathway triggers the TGF-β/Smad pathway, promoting fibrosis development (Alyaseer et al., 2020).

Ang II promotes AF and myocardial fibrosis via diverse inflammatory signaling pathways. Inhibiting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) can reduce inflammation and reverse atrial electrical and structural remodeling (Roşianu et al., 2013). Meta-analyses have demonstrated that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) decrease the risk of AF in patients with hypertension, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and hypertrophy. These agents are effective in treating paroxysmal and persistent AF and in preventing recurrence post-electrical cardioversion or catheter ablation (Jibrini et al., 2008; Li et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2020). ACEIs reduce AF duration by decreasing frequency-dependent APD90 in the atrial myocardium and lowering MAPK and AngII levels (Nakashima et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2011). Chlorosartan decreases AF susceptibility by modulating ion channel expression, particularly increasing Ito (Kv4.2) and decreasing Kv1.5 and Kir2.1/2.3 (Saygili et al., 2007). Furthermore, telmisartan reduces AF in hypertensive rats by enhancing PI3K/AKT/eNOS signaling (Wang, 2015). Ang1-7, an endogenous antagonist of AngII, improves ventricular remodeling by interfering with p38MAPK and reducing inflammatory mediators such as TGF-β and TNF-α (Bai, 2021).

However, aldosterone antagonists like spironolactone and eplerenone also play a role in delaying the recurrence of paroxysmal and post-catheter ablation AF (Dabrowski et al., 2010; Ito et al., 2013). Eplerenone, in particular, reduces atrial dilation and fibrosis without affecting electrical remodeling (Takemoto et al., 2017). Despite these benefits, a retrospective study indicated that ACEIs and ARBs might increase AF risk post-cardiac bypass grafting, highlighting the complexity of the RAAS-AF relationship (Miceli et al., 2009). This is related to the limitations of clinical detection tools, as it is difficult to detect all clinical AFs before the development of atrial remodelling. There are no reports that inhibition of RAAS can inhibit and reverse atrial remodelling, which may explain the clinical inconsistency. In addition ARNI as a treatment for heart failure, which contains ARBs, has shown potential to reverse remodelling (Abboud and Januzzi, 2021),but has not been used in AF, and future focus should be on the role of RAAS inhibitors/ARNIs on reverse AF remodelling.

Colchicine, a microtubule inhibitor, downregulates various inflammatory pathways and modulates innate immunity by inhibiting protein polymerization and microtubule formation (Lawler et al., 2021). It reduces the activity of NLRP3 inflammasomes and decreases the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and interleukins, such as IL-1β and IL-6 (Amaral et al., 2023). Colchicine has shown efficacy in animal models by reducing atrial fibrosis driven by inflammatory responses, impacting pathways involving IL-1β/IL-6, p38, AKT, and STAT3, as well as NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation (Liu, 2019; Misawa et al., 2013).

Although promising in animal studies, clinical trials have produced mixed outcomes. Some studies report a prophylactic effect against postoperative AF, while others show increased risks of side effects such as gastrointestinal issues, which may influence electrolyte balances and increase AF susceptibility (Wang X. et al., 2022; Deftereos et al., 2012; Gudbjartsson et al., 2020; Duarte, 2014; Conen et al., 2023). Conflicting findings also exist regarding the prevention of pericarditis associated with postoperative AF (Ahmed et al., 2023; Mohanty et al., 2023). The variability in outcomes may result from differences in study designs, dosages, timing, duration, and drug combinations used (Attia and Hiram, 2024).

Steroid therapy, known for its anti-inflammatory effects, shows mixed efficacy in preventing AF (Larsson et al., 2021). While some studies indicate that steroids like prednisolone can reduce electrophysiological changes and fibrosis markers associated with atrial tachycardia remodeling (Shiroshita-Takeshita et al., 2006; Zhang Y. et al., 2022), others have reported potential adverse effects, including the induction of atrial arrhythmias (Iwasaki et al., 2022). Steroids have been effective in preventing AF recurrence post-catheter ablation (Kim et al., 2015) and reducing inflammatory markers (Iskandar et al., 2017). However, they have not consistently improved clinical outcomes post-AF ablation. Dosage plays a critical role, with some studies suggesting that moderate doses may reduce the risk of postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) more effectively than either high or low doses (Viviano et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2014; Chai et al., 2022; Ho and Tan, 2009).

Statins are recognized for their anti-inflammatory properties and their ability to modulate multiple pathways that could reduce AF incidence (Oraii et al., 2021). They have been shown to inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation and modulate the PDGF/Rac1/NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby reducing atrial fibrosis (Soucek et al., 2015; Peña et al., 2012). While statins have been effective in reducing POAF in various surgical contexts, they have not significantly changed the incidence and prognosis of POAF in all studies (Kuhn et al., 2021; An et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2014; Allah et al., 2019; Bonano et al., 2021; Fiedler et al., 2021; Oliveri et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2022). However, they have been shown to reduce the risk of heart failure, stroke, and all-cause mortality, with stronger statins demonstrating greater efficacy (Choi et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2023; Pastori et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Low-dose statin pretreatment has also been found to improve initial stroke severity and functional outcomes at 90 days (Dong et al., 2019). Despite these benefits, current guidelines do not recommend statins specifically for AF management due to study heterogeneity.

Omega-3 fatty acids, a type of polyunsaturated fatty acid found in fish oil, are known for their antioxidant properties. They regulate ion channels, mitigate rapid-pacing-induced shortening of atrial refractory periods, and regulate myocardial CX40 expression, ensuring normal electrical signaling. They also inhibit NF-κB-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation, reducing inflammation and myocardial fibrosis (Szeiffova et al., 2020). While animal studies suggest that PUFA treatment reduces the risk of AF and atrial structural remodeling (Ninio et al., 2005; Sakabe et al., 2007), clinical trials have shown mixed results. Some trials suggest a beneficial effect following coronary artery bypass grafting (Calò et al., 2005), but most report no effect or even exacerbation of AF development, postoperative AF, or post-recovery AF (Saravanan et al., 2010; Albert et al., 2021; Kowey et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2012; Kalstad et al., 2021; Lombardi et al., 2021; Qi et al., 2023). The risk of atrial fibrillation increases with higher doses (Gencer et al., 2021). Variations in patient profiles, surgeries, arrhythmia definitions, and monitoring methods may account for these conflicting findings. Overall, current evidence does not support the use of omega-3 fatty acids for AF treatment.

Although anti-inflammatory therapy for AF has been proposed for over 2 decades, its targeted therapeutic strategies remain under development. The CANTOS trial demonstrated that the monoclonal anti-IL-1β antibody canakinumab reduced major cardiac events and heart failure hospitalizations in CAD patients with elevated hsCRP (Ridker et al., 2011). IL-6 plays a role in AF pathogenesis by promoting neutrophil-induced atrial fibrosis and abnormal calcium currents. IL-6 antibody treatment attenuates atrial fibrosis and reduces AF risk in aseptic pericarditis rat models (Liao et al., 2021). IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, has been shown to mitigate high-fat diet-induced AF, with IL-10 knockout mice exhibiting more severe fibrosis and AF progression, both alleviated by IL-10 administration (Kondo et al., 2018). IL-17A, a pro-inflammatory cytokine from Th17 cells, activates NF-κB and MAPK pathways, contributing to fibrosis and AF in AngII-induced models (Liu et al., 2012). Anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibodies have reduced AF in transesophageal atrial pacing models (Fu et al., 2015). Additionally, IL-33 mediates atrial remodeling by activating CaMKII/RyR2 and NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathways, promoting arrhythmogenesis. Anti-ST2 antibodies have reduced IL-33-mediated atrial fibrosis and arrhythmias in mice (Tzu et al., 2024). These findings indicate that the targeted blockade of inflammatory factors and associated pathways holds significant potential, although further clinical trials are required to validate their efficacy.

AF is one of the most prevalent cardiac arrhythmias, significantly influenced by the RAAS. AngII, a crucial component of this system, facilitates atrial electrical remodeling by modulating ion channels and currents, thereby contributing to the development of AF. Beyond its role in electrical remodeling, AngII also serves as a potent pro-fibrotic agent, driving atrial fibrosis through various inflammatory signaling pathways, including TGF-β, PI3K/AKT, MAPK, Rac1/JAK/STAT3, and NF-κB/NLRP3. This mediation of inflammation and the resultant crosstalk among these pathways are instrumental in the progression of AF. Moreover, AF itself can intensify the inflammatory response, thus perpetuating a vicious cycle that accelerates disease progression.

Recent research underscores the pivotal role of inflammation in the initiation and perpetuation of AF. Inflammation fosters a pro-arrhythmic environment, disrupts the electrophysiological properties of atrial myocytes, and promotes structural remodeling. Targeting inflammation has emerged as a promising strategy for the prevention and treatment of AF. Further investigation into the molecular mechanisms underlying Ang II-induced inflammation is essential to identify novel therapeutic targets. A variety of anti-inflammatory therapies, including RAAS inhibitors, colchicine, steroids, statins, and polyunsaturated fatty acids, have shown potential in reducing AF incidence and improving clinical outcomes, although the results remain inconsistent. The role of ARNI and RAAS inhibitors in reversing cardiac remodeling warrants further investigation. Additionally, the potential of combination therapies integrating anti-inflammatory agents with existing AF treatments should be explored. Large-scale randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of anti-inflammatory strategies in AF management and to develop early interventions aimed at preventing the onset and recurrence of AF. Despite these challenges, the central role of inflammation in arrhythmogenesis highlights a potential path for innovative treatment approaches.

AH: Software, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. DS: Supervision, Writing–review and editing. HH: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing. YL: Formal Analysis, Software, Writing–review and editing. YZ: Supervision, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. R&D and Transformation of Medical Institution Preparations and New Chinese Medicines with Intellectual Property Rights at Xiyuan Hospital, China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (CATCM) (XYZX0303-18).

This is a short text to acknowledge the contributions of specific colleagues, institutions, or agencies that aided the efforts of the authors. The Figures in this paper are all drawn by Figdraw.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1515864/full#supplementary-material

Abboud, A., and Januzzi, J. L. (2021). Reverse cardiac remodeling and ARNI therapy. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 18 (2), 71–83. doi:10.1007/s11897-021-00501-6

Adam, O., Frost, G., Custodis, F., Sussman, M. A., Schäfers, H. J., Böhm, M., et al. (2007). Role of Rac1 GTPase activation in atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50 (4), 359–367. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.041

Adam, O., Lavall, D., Theobald, K., Hohl, M., Grube, M., Ameling, S., et al. (2010). Rac1-induced connective tis-sue growth factor regulates connexin 43 and N-cadherin exp ression inatrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55 (5), 469–480. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.064

Ahmad, W. A., Andrabi, K., and Ul, H. M. (2012). Adenosine-triphosphate-sensitive K+ channel (Kir6.1): a novel phosphospecific interaction partner of connexin 43 (Cx43). Exp. Cell Res. 318 (20), 2559–2566. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.08.004

Ahmed, A. S., Miller, J., Foreman, J., Golden, K., Shah, A., Field, J., et al. (2023). Prophylactic colchicine after radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation: the PAPERS study. Clin. Electrophysiol. 9 (7 Pt 2), 1060–1066. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2023.02.003

Albert, C. M., Cook, N. R., Pester, J., Moorthy, M. V., Ridge, C., Danik, J. S., et al. (2021). Effect of marine omega-3 fatty acid and vitamin D supplementation on incident atrial fibrilla tion:a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 325 (11), 1061–1073. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.1489

Allah, E. A., Kamel, E. Z., Osman, H. M., Abd-Elshafy, S. K., Nabil, F., Elmelegy, T. T. H., et al. (2019). Could short-term perioperative high-dose atorvastatin offer antiarrhythmic and cardio-protective effects in rheumatic valve replacement surgery? J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 33 (12), 3340–3347. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2019.05.013

Allessie, M., Ausma, J., and Schotten, U. (2002). Electrical, contractile and structural remodeling during atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 54 (2), 230–246. doi:10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00258-4

Alyaseer, A. A. A., de Lima, M. H. S., and Braga, T. T. (2020). The role of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the epithelial to mesenchymal transition process during the fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 11, 883. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00883

Amaral, N. B., Rodrigues, T. S., Giannini, M. C., Lopes, M. I., Bonjorno, L. P., Menezes, P. I. S. O., et al. (2023). Colchicine reduces the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in COVID-19 patients. Inflamm. Res. 72 (5), 895–899. doi:10.1007/s00011-023-01718-y

An, J., Shi, F., Liu, S., Ma, J., and Ma, Q. (2017). Preoperative statins as modifiers of cardiac and inflammatory outcomes following coronary artery by pass graft surgery:a meta-analysis. Interact. Cardiovasc Thorac. Surg. 25 (6), 958–965. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivx172

Aonuma, K., Xu, D., Murakoshi, N., Tajiri, K., Okabe, Y., Yuan, Z., et al. (2022). Novel preventive effect of isorhamnetin on electrical and structural remodeling in atrial fibrillation. Clin. Sci. Lond. Engl. 1979 136 (24), 1831–1849. doi:10.1042/CS20220319

Attia, A., and Hiram, R. (2024). Colchicine for the prevention of atrial fibrillation: why do some studies say 'yes', and others say 'no. Int. J. Cardiol. 408, 132110. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.132110

Ausma, J., Lai, L. P., Kuo, K. T., Hwang, J. J., Hsieh, C. S., Hsu, K. L., et al. (2008). Angiotensin II activates signal transducer and activators of transcription 3 via Rac1 in atrial myocytes and fibroblasts: implication for the therapeutic effect of statin in atrial structural remodeling. Circulation 117, 344–355. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.695346

Bai, L.(2021). Effects of Ang1-7 on P38MAPK pathway and inflammation in HL-1 cells. China: Tianjin Medical University.

Bonano, J. C., Aratani, A. K., Sambare, T. D., Goodman, S. B., Huddleston, J. I., Maloney, W. J., et al. (2021). Perioperative statin use may reduce postoperative arrhythmia rates after total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 36 (10), 3401–3405. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2021.05.022

Brezinov, P., Sevylia, Z., Rahkovich, M., Kakzanov, Y., Yahud, E., Fortis, L., et al. (2021). Measurements of immature platelet fraction and inflammatory markers in atrial fibrillation patients - does persistency or ablation affect results? Int. J. laboratory Hematol. 43 (4), 602–608. doi:10.1111/ijlh.13426

Brundel, B. J., et al. (2002). Activation of proteolysis by calpains and structural changes in human paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 54 (2), 380–389. doi:10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00289-4

Butler, K. L., Huffman, L. C., Koch, S. E., Hahn, H. S., and Gwathmey, J. K. (2006). STAT-3 activation is necessary for ischemic preconditioning in hypertrophied myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291 (2), 797–803. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.01334.2005

Calò, L., Bianconi, L., Colivicchi, F., Lamberti, F., Loricchio, M. L., de Ruvo, E., et al. (2005). N-3 Fatty acids for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 17 (45), 1723–1728. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.079

Cao, H., Wang, X., Huang, H., Ying, S. Z., Gu, Y. W., Wang, T., et al. (2012). Omega-3 fatty acids in the prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrences after cardioversion: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Intern. Med. (Tokyo, Jpn.) 51 (18), 2503–2508. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7714

Cao, H. J., Fang, J., Zhang, Y. L., Zou, L. X., Han, X., Yang, J., et al. (2019). Genetic ablation and pharmacological inhibition of immunosubunit β5i attenuates cardiac remodeling in deoxycorticosterone-acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertensive mice. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 137, 34–45. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.09.010

Catanese, L., and Hart, R. G. (2019). Stroke and atrial fibrillation. Stroke Prev. Atr. Fibrillation, 161–170. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-55429-9.00013-3

Celias, D. P., Corvo, I., Silvane, L., Tort, J. F., Chiapello, L. S., Fresno, M., et al. (2019). Cathepsin L3 from fasciola hepatica induces NLRP3 inflammasome alternative activation in murine dendritic cells. Front. Immunol. 10, 552. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00552

Chai, T., Zhuang, X., Tian, M., Yang, X., Qiu, Z., Xu, S., et al. (2022). Meta-Analysis: shouldn't prophylactic corticosteroids be administered during cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass? Front. Surg. 9, 832205. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2022.832205

Checa, J. M., and Aran, J. M. (2020). Reactive oxygen species: drivers of physiological and pathological processes. Res 13, 1057–1073. doi:10.2147/jir.s275595

Chen, X., Yu, L., Meng, S., Zhao, J., Huang, X., Wang, Z., et al. (2024). Inhibition of TREM-1 ameliorates angiotensin II-induced atrial fibrillation by attenuating macrophage infiltration and inflammation through the PI3K/AKT/FoxO3a signaling pathway. Cell Signal 124, 111458. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2024.111458

Chen, H., Liu, H., Liu, D., Fu, Y., Yao, Y., Cao, Z., et al. (2024). M2 macrophage-derived exosomes alleviate KCa3.1 channel expression in rapidly paced HL-1 myocytes via the NF-κB (p65)/STAT3 signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 29 (4), 55. doi:10.3892/mmr.2024.13179

Choi, S. E., Bucci, T., Huang, J. Y., Yiu, K. H., Tsang, C. T., Lau, K. K., et al. (2024). Early statin use is associated with improved survival and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and recent ischaemic stroke: a propensity-matched analysis of a global federated health database. Eur. Stroke J., 23969873241274213. doi:10.1177/23969873241274213

Chu, S. L. (2015). “Mediating role of PI3k-Akt signaling pathway in type,” in 2 diabetic rats susceptible to atrial fibrillation. Fujian, China: Fujian Medical University.

Conen, D., Ke Wang, M., Popova, E., Chan, M. T. V., Landoni, G., Cata, J. P., et al. (2023). Effect of colchicine on perioperative atrial fibrillation and myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery in patients undergoing major thoracic surgery (COP-AF): an international randomised trial. Lancet (London, Engl.) 402 (10413), 1627–1635. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01689-6

Dabrowski, R., Borowiec, A., Smolis-Bak, E., Kowalik, I., Sosnowski, C., Kraska, A., et al. (2010). Effect of combined spironolactone–β-blocker ± enalapril treatment on occurrence of symptomatic atrial fibrillation episodes in patients with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (SPIR-AF study). Am. J. Cardio I 106 (11), 1609–1614. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.07.037

Dawn, B., Xuan, Y. T., Guo, Y., Rezazadeh, A., Stein, A. B., Hunt, G., et al. (2004). IL-6 plays an obligatory role in late preconditioning via JAK-STAT signaling and upregulation of iNOS and COX-2. Cardiovasc Res. 64 (1), 61–71. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.05.011

Deftereos, S., Giannopoulos, G., Kossyvakis, C., Efremidis, M., Panagopoulou, V., Kaoukis, A., et al. (2012). Colchicine for prevention of early atrial fibrillation recurrence after pulmonary vein isolation: a randomized controlled study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60, 1790–1796. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.031

Deng, H., Xue, Y. M., Zhan, X. Z., Liao, H. T., Guo, H. M., and Wu, S. L. (2011). Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Chin. Med. Jen. Gl. 124 (13), 1976–1982. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2011.13.010

Di, G. M., Gambelli, F., Hoyle, G. W., Lungarella, G., Studer, S. M., Richards, T., et al. (2009). Systemic inhibition of NF-kappaB activation protects from silicosis. PLoS One 4 (5), 5689. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005689

Dong, S., Guo, J., Fang, J., Hong, Y., Cui, S., and He, L. (2019). Low-dose statin pretreatment reduces stroke severity and improves functional outcomes. J. neurology 266 (12), 2970–2978. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09520-9

Duarte, J. H. (2014). Interventional cardiology: colchicine therapy prevents postpericardiotomy syndrome but not postoperative atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 11 (11), 620. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2014.152

Dzeshka, M. S., Lip, G. Y. H., Snezhitskiy, V., and Shantsila, E. (2015). Cardiac fibrosis in patients with atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and clinical implications. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66 (8), 943–959. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1313

Fan, D. M., and Xue, L. (2012). Study on the role of nuclear transcription factor kappaB in ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. Shaanxi Med. J. 41 (12), 1582–1585. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7377.2012.12.005

Fan, B. Z. (2014). Expression of NF-kB protein in atrial muscle of patients with rheumatic heart disease with atrial fibrillation. Fujian, China: Fujian Medical University.

Fiedler, L., Hallsson, L., Tscharre, M., Oebel, S., Pfeffer, M., Schönbauer, R., et al. (2021). Upstream statin therapy and long-term recurrence of atrial fibrillation after cardioversion: a propensity-matched analysis. J. Clin. Med. 10 (4), 807. doi:10.3390/jcm10040807

Fischer, P., and Hilfiker-Kleiner, D. (2008). Role of gp130-mediated signalling pathways in the heart and its impact on potential therapeutic aspects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153 (1), 414–427. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.1

Forrester, S. J., Booz, G. W., Sigmund, C. D., Coffman, T. M., Kawai, T., Rizzo, V., et al. (2018). Angiotensin II signal transduction: an update on mechanisms of physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 98 (3), 1627–1738. doi:10.1152/physrev.00038.2017

Friedrichs, K., Klinke, A., and Baldus, S. (2011). Inflammatory pathways underlying atrial fibrillation. Trends Mol. Med. 17 (10), 556–563. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.007

Fu, X. X., Zhao, N., Dong, Q., Du, L. L., Chen, X. J., Wu, Q. F., et al. (2015). Interleukin-17A contributes to the development of post-operative atrial fibrillation by regulating inflammation and fibrosis in rats with sterile pericarditis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 36 (1), 83–92. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2015.2204

Gencer, B., Djousse, L., Al-Ramady, O. T., Cook, N. R., Manson, J. E., and Albert, C. M. (2021). Effect of long-term marine ɷ-3 fatty acids supplementation on the risk of atrial fibrillation in randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 144 (25), 1981–1990. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055654

Gu, J., Hu, W., and Liu, X. (2014). Pioglitazone improves potassium channel remodeling induced by angiotensin II in atrial myocytes. Med. Sci. Monit. basic Res. 20, 153–160. doi:10.12659/MSMBR.892450

Guan, X. X., Yang, H. H., Zhong, W. J., Duan, J. X., Zhang, C. Y., Jiang, H. L., et al. (2022). Fn14 exacerbates acute lung injury by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome in mice. Mol. Med. 28 (1), 85. doi:10.1186/s10020-022-00514-4

Gudbjartsson, T., Helgadottir, S., Sigurdsson, M. I., Taha, A., Jeppsson, A., Christensen, T. D., et al. (2020). New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation after heart surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 64 (2), 145–155. doi:10.1111/aas.13507

Gungor, B., Ekmekci, A., Arman, A., Ozcan, K. S., Ucer, E., Alper, A. T., et al. (2013). Assessment of interleukin-1 gene cluster polymorphisms in lone atrialfibrillation:new insight into the role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation. Pacing clinicalelectrophysiology:PACE 36 (10), 1220–1227. doi:10.1111/pace.12182

Guo, Y., Lip, G. Y., and Apostolakis, S. (2012). Inflammation in atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60 (22), 226–2270. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.063

Guo, Y. Y., et al. (2019). Study on the correlation between interleukin-18 and atrial fibrillation. J. Harbin Med. Univ. 53 (01), 47–52.

Han, S. X., et al. (2021). c-Ski improves structural remodeling of canine atria through inhibition of TGF-β1/SMAD and p38 MAPK pathways. J. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 37 (10), 910–916. doi:10.13423/j.cnki.cjcmi.009256

Hattori, Y., Akimoto, K., Nishikimi, T., Matsuoka, H., and Kasai, K. (2006). Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase enhances angiotensin II–induced proliferation in cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 47, 265–270. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.0000198425.21604.aa

He, X., Gao, X., Peng, L., Wang, S., Zhu, Y., Ma, H., et al. (2011). Atrial fibrillation induces myocardial fibrosis through angiotensin II type 1 receptor-specific Arkadia-mediated downregulation of Smad7. Circ. Res. 108 (2), 164–175. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.234369

He, S., Wang, Y., Yao, Y., Cao, Z., Yin, J., Zi, L., et al. (2021). Inhibition of KCa3.1 channels suppresses atrial fibrillation via the attenuation of macrophage pro-inflammatory polarization in a canine model with prolonged rapid atrial pacing. Front. Cardiovasc Med. 8, 656631. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.656631

Hirotani, S., Otsu, K., Nishida, K., Higuchi, Y., Morita, T., Nakayama, H., et al. (2002). Involvement of nuclear factor-κb and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in G-protein–coupled receptor agonist–induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Circulation 105, 509–515. doi:10.1161/hc0402.102863

Hirsh, B. J., Copeland-Halperin, R. S., and Halperin, J. L. (2015). Fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, and thromboembolism: mechanistic links and clinical inferences. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 2239–2251. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.557

Ho, K. M., and Tan, J. A. (2009). Benefits and risks of corticosteroid prophylaxis in adult cardiac surgery: a dose-response meta-analysis. Circulation 119 (14), 1853–1866. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.848218

Hoffmann, S., Clauss, S., Berger, I. M., Weiß, B., Montalbano, A., Röth, R., et al. (2016). Coding and non-coding variants in the SHOX2 gene in patients with early-onset atrial fibrillation. Basic Res. Cardiol. 111 (3), 36. doi:10.1007/s00395-016-0557-2

Hu, Y. F., Chen, Y. J., Lin, Y. J., and Chen, S. A. (2015). Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 12, 230–243. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2015.2

Hu, W., Lu, H., Zhang, J., Fan, Y., Chang, Z., Liang, W., et al. (2018). Krüppel-like factor 14, a coronary artery disease associated transcription factor, inhibits endothelial inflammation via NF-κB signaling pathway. Atherosclerosis 278, 39–48. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.09.018

Huang, C. Y., Yang, Y. H., Lin, L. Y., Tsai, C. T., Hwang, J. J., Chen, P. C., et al. (2018). Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone blockade reduces atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart (British Card. Soc.) 104 (15), 1276–1283. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312573

Huang, J. Y., Chan, Y. H., Tse, Y. K., Yu, S. Y., Li, H. L., Chen, C., et al. (2023). Statin therapy is associated with a lower risk of heart failure in patients with atrial fibrillation: a population-based study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12 (23), 032378. doi:10.1161/JAHA.123.032378

Iskandar, S., Reddy, M., Afzal, M. R., Rajasingh, J., Atoui, M., Lavu, M., et al. (2017). Use of oral steroid and its effects on atrial fibrillation recurrence and inflammatory cytokines post ablation - the steroid af study. J. Atr. Fibrillation 9, 1604. doi:10.4022/jafib.1604

Ito, Y., Yamasaki, H., Naruse, Y., Yoshida, K., Kaneshiro, T., Murakoshi, N., et al. (2013). Effect of eplerenone on maintenance of sinus rhythm after catheter ablation in patients with lo ng-standing persistent atrial fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 111 (7), 1012–1018. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.12.020

Iwasaki, Y. K., Nishida, K., Kato, T., and Nattel, S. (2011). Atrial fibrillation pathophysiology: implications for management. Circulation 124 (20), 2264–2274. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.019893

Iwasaki, Y. K., Sekiguchi, A., Kato, T., and Yamashita, T. (2022). Glucocorticoid induces atrial arrhythmogenesis via modification of ion channel gene expression in rats. Int. heart J. 63 (2), 375–383. doi:10.1536/ihj.21-677

Jansen, H., Mackasey, M., Moghtadaei, M., Liu, Y., Kaur, J., Egom, E. E., et al. (2019). NPR-C (natriuretic peptide receptor-C) modulates the progression of angiotensin II-mediated atrial fibrillation and atrial remodeling in mice. Circulation, Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 12, e006863. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006863

Jia, L., et al. (2012). Angiotensin II induces inflammation leading to cardiac remodeling. Front. Biosci. 17, 221–231. doi:10.2741/3923

Jiang, L., Li, L., Ruan, Y., Zuo, S., Wu, X., Zhao, Q., et al. (2019). Ibrutinib promotes atrial fibrillation by inducing structural remodeling and calcium dysregulation in the atrium. Heart rhythm. 16 (9), 1374–1382. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.04.008

Jibrini, M. B., Molnar, J., and Arora, R. R. (2008). Prevention of atrial fibrillation by way of abrogation of the renin-angiotensin system:a systemati c review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Ther. 15 (1), 36–43. doi:10.1097/mjt.0b013e31804beb59

Kalstad, A. A., Myhre, P. L., Laake, K., Tveit, S. H., Schmidt, E. B., Smith, P., et al. (2021). Effects of n-3 fatty acid supplements in elderly patients after myocardial infarction: a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation 143 (6), 528–539. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052209

Kang, J. Y. (2019). Role and mechanism of Toll-like receptor 4 expression regulation in anti-inflammatory and inhibition of myocardial fibrosis by erythropoietin in rats. Nanchang, China: Nanchang University.

Kim, Y. R., Nam, G. B., Han, S., Kim, S. H., Kim, K. H., Lee, S., et al. (2015). Effect of short-term steroid therapy on early recurrence during the blanking period after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 8 (6), 1366–1372. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002957

Kondo, H., Abe, I., Gotoh, K., Fukui, A., Takanari, H., Ishii, Y., et al. (2018). Interleukin 10 treatment ameliorates high-fat diet-induced inflammatory atrial remodeling and fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 11 (5), 006040. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.117.006040

Kowey, P. R., Reiffel, J. A., Ellenbogen, K. A., Naccarelli, G. V., and Pratt, C. M. (2010). Efficacy and safety of prescription omega-3 fatty acids for the prevention of recurrent symptomatic atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 304 (21), 2363–2372. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1735

Krijthe, B. P., Kunst, A., Benjamin, E. J., Lip, G. Y. H., Franco, O. H., Hofman, A., et al. (2013). Projections on the number of individuals with atrial fibrillation in the European Union, from 2000 to 2060. Eur. Heart J. 34 (35), 2746–2751. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht280

Krishnamurthy, P., Rajasingh, J., Lambers, E., Qin, G., Losordo, D. W., and Kishore, R. (2009). IL-10 inhibits inflammation and attenuates left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction via activation of STAT3 and suppression of HuR. Circ. Res. 104 (2), e9–e18. doi:10.1161/circresaha.108.188243

Kuhn, E. W., Liakopoulos, O. J., Choi, Y. H., Rahmanian, P., Eghbalzadeh, K., Slottosch, I., et al. (2021). Preoperative statin therapy for atrial fibrillation and renal failure after cardiac surgery. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 69 (2), 141–147. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1710322

Larsson, S. C., Lee, W. H., Burgess, S., and Allara, E. (2021). Plasma cortisol and risk of atrial fibrillation: a mendelian randomization study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. metabolism 106 (7), 2521–2526. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab219

Lawler, P. R., Bhatt, D. L., Godoy, L. C., Lüscher, T. F., Bonow, R. O., Verma, S., et al. (2021). Targeting cardiovascular inflammation:next steps in clinical translation. Eur. Heart J. 42 (1), 113–131. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa099

Lee, H. M., Kim, T. S., and Jo, E. K. (2016). MiR-146 and miR-125 in the regulation of innate immunity and inflammation. BMB Rep. 49 (6), 311–318. doi:10.5483/bmbrep.2016.49.6.056

Li, N., and Brundel, B. (2020). Inflammasomes and proteostasis novel molecular mechanisms associated with atrial fibrillation. Circ. Res. 127 (1), 73–90. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.316364

Li, D., Fareh, S., Leung, T. K., and Nattel, S. (1999). Promotion of atrial fibrillation by heart failure in dogs: atrial remodeling of a different sort. Circulation 100, 87–95. doi:10.1161/01.cir.100.1.87

Li, T. J., Zang, W. D., Chen, Y. L., Geng, N., Ma, S. M., and Li, X. D. (2013). Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors for prevention of recurrent atrial fibrillation:a metaanalysis. IntJ Clin. Pract. 67 (6), 536–543. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12063

Li, J., Wang, S., Bai, J., Yang, X. L., Zhang, Y. L., Che, Y. L., et al. (2018). Novel role for the immunoproteasome subunit PSMB10 in angiotensinII-induced atrial fibrillatio n in mice. Hypertension 71 (5), 866–876. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10390

Li, B., Zhang, B., Bai, F., Li, J., Qin, F., et al. (2020). Metformin regulates adiponectin signalling in epicardial adipose tissue and reduces atrial fibrillation vulnerability. J. Cell Mol. Med. 24 (14), 7751–7766. doi:10.1111/jcmm.15407

Li, D., Liu, Y., Li, C., Zhou, Z., Gao, K., Bao, H., et al. (2024). Spexin diminishes atrial fibrillation vulnerability by acting on galanin receptor 2. Circulation 150 (2), 111–127. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.067517

Li, S. C. (2019). FGF23 promotes atrial fibrosis through the ROS/STAT3/SMAD3 pathway. Nanchang, China: Nanchang University.

Liang, X. Y. (2023). Intervention of PI3k/Akt/mTOR pathway to regulate Tregs/Th17 immune self-stabilization imbalance in heart failure ventricular remodeling and mechanism. Xinjiang, China: Xinjiang Medical University. doi:10.27433/d.cnki.gxyku.2022.000021

Liao, J., Zhang, S., Yang, S., Lu, Y., Lu, K., Wu, Y., et al. (2021). Interleukin-6-mediated-Ca(2+) handling abnormalities contributes to atrial fibrillation in sterile pericarditis rats. Front. Immunol. 12, 758157. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.758157

Lin, D., Luo, H., Dong, B., He, Z., Ma, L., Wang, Z., et al. (2024). FOXO3a induces myocardial fibrosis by upregulating mitophagy. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 29 (2), 56. doi:10.31083/j.fbl2902056

Liu, E., Xu, Z., Li, J., Yang, S., Yang, W., and Li, G. (2011). Enalapril,irbesartan,and angiotensin-(1-7)prevent atrial tachycardia-induced ionic remodeling. Int. J. Car diol 146 (3), 364–370. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.07.015

Liu, T., Peng, L., Yu, P., Zhao, Y., Shi, Y., Mao, X., et al. (2012). Increased circulating Th22 and Th17 cells are associated with tumor progression and patient survival in human gastric cancer. J. Clin. Immunol. 32, 1332–1339. doi:10.1007/s10875-012-9718-8

Liu, C., Wang, J., Yiu, D., and Liu, K. (2014). The efficacy of glucocorticoids for the prevention of atrial fibrillation, or length of intensive care unite or hospital stay after cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Ther. 32 (3), 89–96. doi:10.1111/1755-5922.12062

Liu, L., Gan, S., Ge, X., Yu, H., and Zhou, H. (2019). Fisetin alleviates atrial Inflammation,Remodeling,and vulnerability to atrial fibrillation after myocar dial infarction. Int. Heart J. 60 (6), 1398–1406. doi:10.1536/ihj.19-131

Liu, D., Zhan, Y., Ono, K., Yin, Y., Wang, L., Wei, M., et al. (2022). Pharmacological activation of estrogenic receptor G protein-coupled receptor 30 attenuates angiotensin II-induced atrial fibrosis in ovariectomized mice by modulating TGF-β1/smad pathway. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49 (7), 6341–6355. doi:10.1007/s11033-022-07444-8

Liu, H. (2019). Colchicine inhibits atrial fibrillation in a rat model of aseptic pericarditis by blocking IL-1β/IL-6. Xinjiang, China: Xiamen University.

Lombardi, M., Carbone, S., Del Buono, M. G., Chiabrando, J. G., Vescovo, G. M., Camilli, M., et al. (2021). Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation and risk of atrial fibrillation: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 7 (4), 69–70. doi:10.1093/ehjcvp/pvab008

Lu, Q. (2024). Clinical analysis of glucose-regulated protein 94 and transforming growth factor-β1 in patients with atrial fibrillation. Bengbu Med. Coll. 2024. doi:10.26925/d.cnki.gbbyc.2023.000111

Luo, L. Y. (2023). Mechanism of angiotensin II promoting myocardial amyloid deposition and fibrosis through PI3K-AKT-mTOR. China: Dalian Medical University. doi:10.26994/d.cnki.gdlyu.2022.000030

Ma, X., Yuan, H., Luan, H. x., Shi, Y. l., Zeng, X. l., and Wang, Y. (2018). Elevated soluble ST2 concentration mayinvolve in the progression of atrial fibrillation. Clin. Chimica Acta;International J. ofClinical Chem. 480, 138–142. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2018.02.005

Mian, M. O. R., He, Y., Bertagnolli, M., Mai-Vo, T. A., Fernandes, R. O., Boudreau, F., et al. (2019). TLR (Toll-Like receptor) 4 antagonism prevents left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction caused by neonatal hyperoxia exposure in rats. Hypertension 74 (4), 843–853. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13022

Miceli, A., Capoun, R., Fino, C., Narayan, P., Bryan, A. J., Angelini, G. D., et al. (2009). Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy on clinical outcome in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 54, 1778–784. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.008

Misawa, T., Takahama, M., Kozaki, T., Lee, H., Zou, J., Saitoh, T., et al. (2013). Microtubule-driven spatial arrangement of mitochondria promotes activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. NatureImmunology 14 (5), 454–460. doi:10.1038/ni.2550

Mohanty, S., Mohanty, P., Kessler, D., Gianni, C., Baho, K. K., Morris, T., et al. (2023). Impact of colchicine monotherapy on the Risk of acute pericarditis following atrial fibrillation ablation. Clin. Electrophysiol. 9 (7 Pt 2), 1051–1059. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2023.01.037

Nakashima, H., and Kumagai, K. (2007). Reverse-remodeling effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker in a canine atrial fibrillation model. Circ. J. 71 (12), 1977–1982. doi:10.1253/circj.71.1977

Nakashima, H., Kumagai, K., Urata, H., Gondo, N., Ideishi, M., and Arakawa, K. (2000). Angiotensin II antagonist prevents electrical remodeling in atrial fibrillation. Circulation 101 (22), 2612–2617. doi:10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2612

Ninio, D. M., Murphy, K. J., Howe, P. R., and Saint, D. A. (2005). Dietary fish oil protects against stretch-induced vulnerability to atrial fibrillation in a rabbit model. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 16 (11), 1189–1194. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.50007.x

Obana, M., Maeda, M., Takeda, K., Hayama, A., Mohri, T., Yamashita, T., et al. (2010). Therapeutic activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 by interleukin-11 ameliorates cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation 121 (5), 684–691. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.893677

Oliveri, F., Bongiorno, A., Compagnoni, S., Fasolino, A., Gentile, F. R., Pepe, A., et al. (2022). Statin and postcardiac surgery atrial fibrillation prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 80 (2), 180–186. doi:10.1097/FJC.0000000000001294

Oraii, A., Vasheghani-Farahani, A., Oraii, S., Roayaei, P., Balali, P., and Masoudkabir, F. (2021). Update on the efficacy of statins in primary and secondary prevention of atrial fibrillation. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 40 (7), 509–518. doi:10.1016/j.repce.2020.11.024

Pastori, D., Baratta, F., Di Rocco, A., Farcomeni, A., Del Ben, M., Angelico, F., et al. (2021). Statin use and mortality in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 100,287 patients. Pharmacol. Res. 165, 105418. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105418

Peña, J. M., MacFadyen, J., Glynn, R. J., and Ridker, P. M. (2012). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein,statin therapy,and risks of atrial fibrillation: an exploratory analysis of the JUPITER trial. Eur. Heart J. 33 (4), 531–537. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr460

Perbal, B. (2004). CCN proteins: multifunctional signalling regulators. Lancet 363, 62–64. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15172-0

Qi, X., Zhu, H., Ya, R., and Huang, H. (2023). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplements and cardiovascular disease outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis on randomized controlled trials. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 24 (1), 24. doi:10.31083/j.rcm2401024

Reunanen, N., Li, S. P., Ahonen, M., Foschi, M., Han, J., and Kähäri, V. M. (2002). Activation of p38a MAPK enhances collagenase-1 (matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1) and stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) expression by mRNA stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32360–32368. doi:10.1074/jbc.m204296200

Ridker, P. M., Thuren, T., Zalewski, A., and Libby, P. (2011). Interleukin-1β inhibition and the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events: rationale and design of the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS). Am. heart J. 162 (4), 597–605. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.06.012

Roşianu, Ş. H., Roşianu, A. N., Aldica, M., Căpâlneanu, R., and Buzoianu, A. D. (2013). Inflammatory markers in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and the protective role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Clujul Med. 86 (3), 217–221.

Rucker-Martin, C., Milliez, P., Tan, S., Decrouy, X., Recouvreur, M., Vranckx, R., et al. (2006). Chronic hemodynamic o-verload of the atria is an important factor for gap junction rem odelingin human and rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 72, 69–79. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.016

Sakabe, M., Shiroshita-Takeshita, A., Maguy, A., Dumesnil, C., Nigam, A., Leung, T. K., et al. (2007). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids prevent atrial fibrillation associated with heart failure but not atrial tachycardia remodeling. Circulation 116 (19), 2101–2109. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704759

Saravanan, P., Bridgewater, B., West, A. L., O'Neill, S. C., Calder, P. C., and Davidson, N. C. (2010). Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation does not reduce risk of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 3 (1), 46–53. doi:10.1161/circep.109.899633

Sawaya, S. E., Rajawat, Y. S., Rami, T. G., Szalai, G., Price, R. L., Sivasubramanian, N., et al. (2007). Downregulation of connexin40 and increased prevalence of atrial arrhythmias in tran sgenic mice with cardiac-restricted overexpression of tumor necrosis factor. AmJ Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292 (3), 1561–1567. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00285.2006

Saygili, E., Rana, O. R., Reuter, H., Frank, K., Schwinger, R. H. G., et al. (2007). Losartan prevents stretch-induced electrical remodeling in cultured atrial neonatal myocytes. AmJ Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292 (6), 2 898–H2905. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00546.2006

Schnabel, R. B., Yin, X., Gona, P., Larson, M. G., Beiser, A. S., McManus, D. D., et al. (2015). 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a Cohort Study. Lancet 386 (9989), 154–162. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61774-8

Shintaro, K., Abe, I., Ishii, Y., Miyoshi, M., Oniki, T., Arakane, M., et al. (2020). Role of angiopoietin-like protein 2 in atrial fibrosis induced by human epicardial adipose tissue: analysis using an organo-culture system. Heart rhythm. 17 (9), 1591–1601. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.04.027

Shiroshita-Takeshita, A., Brundel, B. J. J. M., Lavoie, J., and Nattel, S. (2006). Prednisone prevents atrial fibrillation promotion by atrial tachycardia remodeling in dogs. Cardiovasc. Res. 69 (4), 865–875. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.028

Shuai, W., Kong, B., Fu, H., Shen, C., and Huang, H. (2019). Loss of MD1 increases vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmia in diet-induced obesity mice via enhanced activation of the TLR4/MyD88/CaMKII signaling pathway. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc Dis. 29 (9), 991–998. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2019.06.004

Shuai, W., Peng, B., Zhu, J., Kong, B., Fu, H., and Huang, H. (2023). 5-Methoxytryptophan alleviates atrial structural remodeling in ibrutinib-associated atrial fibrillation. Heliyon 9 (9), e19501. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19501

Sinner, M. F., Stepas, K. A., Moser, C. B., Krijthe, B. P., Aspelund, T., Sotoodehnia, N., et al. (2014). B-type natriuretic peptide and C-reactive protein in the prediction of atrial fibrillation risk: the CHARGE-AF Consortium of community-based cohort studies. Europace 16 (10), 1426–33. doi:10.1093/europace/euu175

Soucek, F., Covassin, N., Singh, P., Ruzek, L., Kara, T., Suleiman, M., et al. (2015). Effects of atorvastatin (80 mg) therapy on quantity of epicardial adipose tissue in patients undergoing pulmonary vein isolation for atrial fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 116 (9), 1443–1446. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.067

Staerk, L., Sherer, J. A., Ko, D., Benjamin, E. J., and Helm, R. H. (2017). Atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical outcomes. Circulation Res. 120 (9), 1501–1517. doi:10.1161/circresaha.117.309732

Stark, A. K., Sriskantharajah, S., Hessel, E. M., and Okkenhaug, K. (2015). PI3K inhibitors in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 23 (23), 82–91. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2015.05.017

Szeiffova, B. B., Viczenczova, C., Andelova, K., Sykora, M., Chaudagar, K., Barancik, M., et al. (2020). Antiarrhythmic effects of melatonin and omega-3 are linked with protecti on of myocardial Cx43 topology and suppression of fibrosis in catecholamine stressed normotensive and hypertensive rats. Anti Oxid. 9 (6), 546. doi:10.3390/antiox9060546

Tai, B. Y., Lu, M. K., Yang, H. Y., Tsai, C. S., and Lin, C. Y. (2022). Ziprasidone induces rabbit atrium arrhythmogenesis via modification of oxidative stress and sodium/calcium homeostasis. Biomedicines 10 (5), 976. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10050976

Takemoto, Y., Ramirez, R. J., Kaur, K., Salvador-Montañés, O., Ponce-Balbuena, D., Ramos-Mondragón, R., et al. (2017). Eplerenone reduces atrial fibrillation burden without preventing atrial electrical remodeling. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 70 (23), 2893–2905. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.014

Tan, A. Y., and Zimetbaum, P. (2011). Atrial fibrillation and atrial fibrosis. J. Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 57, 625–629. doi:10.1097/fjc.0b013e3182073c78

Tien, T. Y., Wu, Y. J., Su, C. H., Wang, H. H., Hsieh, C. L., Wang, B. J., et al. (2021). Reduction of connexin 43 attenuates angiogenic effects of human smooth muscle progenitor cells via inactivation of akt and NF-κB pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Bio1 41 (2), 915–930. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.120.315650

Tsai, C. T., Wang, D. L., Chen, W. P., Hwang, J. J., Hsieh, C. S., Hsu, K. L., et al. (2007). Angiotensin II increases expression of alpha1C subunit of L-type calcium channel through a reactive oxygen species and cAMP response element-binding protein-dependent pathway in HL-1 myocytes. Circ. Res. 100 (10), 1476–1485. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000268497.93085.e1

Tsai, C. T., Lin, J. L., Lai, L. P., Lin, C. S., and Huang, S. K. S. (2008). Membrane translocation of small GTPase Rac1 and activation of STAT1 and STAT3 in pacing-induced sustained atrial fibrillation. Heart rhythm. 5, 1285–1293. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.012

Tzu, Y. C., Chen, Y. C., Li, S. J., Lin, F. J., Lu, Y. Y., Lee, T. I., et al. (2024). Interleukin-33/ST2 axis involvement in atrial remodeling and arrhythmogenesis. Transl. Res. 268, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2024.01.006

Valente, A. J., Yoshida, T., Gardner, J. D., Somanna, N., Delafontaine, P., and Chandrasekar, B. (2012). Interleukin-17A stimulates cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration via negative regulation of the dual-specificity phosphatase MKP-1/DUSP-1. Cell. Signal 24, 560–568. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.10.010

Viviano, A., Kanagasabay, R., and Zakkar, M. (2014). Is perioperative corticosteroid administration associated with a reduced incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation in adult cardiac surgery?. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 18 (2), 225–229. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivt486

Vyas, V., Hunter, R. J., Longhi, M. P., and Finlay, M. C. (2020). Inflammation and adiposity: new frontiers in atrial fibrillation. Europace 22, 1609–1618. doi:10.1093/europace/euaa214

Wang, W. B., et al. (2022). Cx43 regulates NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles involved in a1-AR activation-induced acute sympathetic stress in the heart. J. Anhui Med. Univ. 57 (4), 534–539. doi:10.19405/j.cnki.issn1000-1492.2022.04.006

Wang, X., Peng, X., Li, Y., Lin, R., Liu, X., Ruan, Y., et al. (2022). Colchicine for prevention of post-cardiac surgery and post-pulmonary vein isolation atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 23 (12), 387. doi:10.31083/j.rcm2312387

Wang, J., Guo, R., Ma, X., Wang, Y., Zhang, Q., Zheng, N., et al. (2023). Liraglutide inhibits AngII-induced cardiac fibroblast proliferation and ECM deposition through regulating miR-21/PTEN/PI3K pathway. Cell tissue Bank. 24 (1), 125–137. doi:10.1007/s10561-022-10021-9

Wang, W. W. (2015). The role of AngⅡ/AT1R and PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway in structural remodeling of hypertensive atria and the effect of telmisartan on susceptibility to atrial fibrillation in hypertensive rats. China: Fujian Medical University.

Wang, X. L. (2023). Experimental study of structural remodeling-electrical remodeling in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes regulated by Zhenwu Tang via p38-MAPK signaling pathway. Jiangxi Univ. Traditional Chin. Med. Master's Degree Thesis. doi:10.27180/d.cnki.gjxzc.2023.000232

Wu, Q. W., et al. (2021). Inhibitory effect of curcumin on angiotensin II-induced activation of cardiac fibroblasts and its mechanism. J. Guangxi Med. Univ. 38 (05), 853–857. doi:10.16190/j.cnki.45-1211/r.2021.05.003

Xiao, H., and Zhang, Y. Y. (2008). Understanding the role of transforming growth factor-beta signalling in the heart: overview of studies using genetic mouse models. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. and physiology 35 (3), 335–341. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04876.x

Xie, X., Shen, T. T., Su, Z. L., Liao, Z. Q., Zhang, Y., et al. (2022). Melatonin inhibits angiotensin II-induced atrial fibrillation through preventing degradation of Ang II Type I Receptor-Associated Protein (ATRAP). Biochem. Pharmacol. 202, 115146. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115146

Xu, Q., Bo, L., Hu, J., Geng, J., Chen, Y., Li, X., et al. (2018). High mobility group box 1 was associated with thrombosis in patients with atrial fibrillation. Medicine (Baltimore) 97(13), 0132. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010132

Xu, N., et al. (2022). Correlation between NF-κB/TNF-α pathway and atrial fibrillationJ. J. Hainan Med. Coll. 28 (12), 898–903. doi:10.13210/j.cnki.jhmu.20220407.004

Xue, X., Ling, X., Xi, W., Wang, P., Sun, J., Yang, Q., et al. (2020). Exogenous hydrogen sulfide reduces atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation induced by diabetes mellitus via activation of the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 22, 1759–1766. doi:10.3892/mmr.2020.11291

Yan, P., Dong, P., Li, Z., and Cheng, J. (2014). Statin therapy decreased the recurrence frequency of atrial fibrillation after electrical cardioversion: a meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 20, 2753–2758. doi:10.12659/MSM.891049

Yang, S., Zhao, Z., Zhao, N., Liao, J., Lu, Y., Zhang, S., et al. (2022). Blockage of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 prevents postoperative atrial fibrillation by inhibiting NLRP3-inflammasome in sterile pericarditis mice. Cell Calcium 104, 102590. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2022.102590

Yao, C., Veleva, T., Scott, L., Cao, S., Li, L., Chen, G., et al. (2018). Enhanced cardiomyocyte NLRP3 inflammasome signaling promotes atrial fibrillation. Circulation 138 (20), 2227–2242. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035202

Yu, Y. X., et al. (2013). Signaling pathways and targeted therapeutics for Chinese diseases. Hefei: Anhui Science and Technology Press.

Yu, Y., Ding, L., Deng, Y., Huang, H., Cheng, S., Cai, C., et al. (2022). Independent and joint association of statin therapy with adverse outcomes in heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 6645–6656. doi:10.2147/JIR.S390127

Yuntao, F., Jinjun, L., Hua Fen, L., Huiyu, C., Dishiwen, L., Zhen, C., et al. (2024). Atrial fibroblast-derived exosomal miR-21 upregulate myocardial KCa3.1 via the PI3K-Akt pathway during rapid pacing. Heliyon 10 (13), e33059. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33059

Yusuke, S., Ruiz-Ortega, M., Lorenzo, O., Ruperez, M., Esteban, V., and Egido, J. (2003). Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int. J. Biochem. and Cell Biol. 35 (6), 881–900. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00271-6

Zhang, C., Li, J., Aji, T., Li, L., Bi, X., Yang, N., et al. (2019). Identification of functional MKK3/6 and MEK1/2 homologs from echinococcus granulosus and investigation of protoscolecidal activity of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway inhibitors in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63 (1), e01043. doi:10.1128/AAC.01043-18

Zhang, J., Feng, R., Ferdous, M., Dong, B., Yuan, H., and Zhao, P. (2020). Effect of 2 different dosages of rosuvastatin on prognosis of acute myocardial infarction patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation in jinan, China. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 26, 925666. doi:10.12659/MSM.925666

ZhangH., , Lai, Y., Zhou, H., Zou, L., Xu, Y., and Yin, Y. (2022). Prednisone ameliorates atrial inflammation and fibrosis in atrial tachypacing dogs. Int. heart J. 63 (2), 347–355. doi:10.1536/ihj.21-249

ZhangY., , Zhang, S., Luo, Y., Gong, Y., Jin, X., et al. (2022). Gut microbiota dysbiosis promotesage-related atrial fibrillation by lipopolysaccharide and glucose-induced activation ofNLRP3-inflammasome. Cardiovasc. Res. 118 (3), 785–797. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvab114

Zhang, X. D. (2017). Mechanism of IL-17 involved in atrial fibrosis and its predictive value for recurrence after atrial fibrillation ablation. China: Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Zhang, P. (2024). Molecular mechanism of IGF-1R regulating myocardial fibrosis in atrial fibrillation through PI3K/Akt/FoxO3a pathway. China: Shandong University. doi:10.27272/d.cnki.gshdu.2022.006781

Zhao, J., Chen, M., Zhuo, C., Huang, Y., Zheng, L., and Wang, Q. (2020). The effect of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors on the recurrence of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation. Int. Heart J. 61 (6), 1174–1182. doi:10.1536/ihj.20-346

Zheng, L. Y., Zhang, M. H., Xue, J. H., Li, Y., Nan, Y., Li, M. J., et al. (2014). Effect of angiotensin II on STAT3 mediated atrial structural remodeling. Eur. Rev. Med. Phar macol Sci. 18 (16), 2365–2377.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, inflammation, AngII, electrical remodelling, fibrosis, anti-inflammatory therapy

Citation: Hou A, Shi D, Huang H, Liu Y and Zhang Y (2025) Inflammation pathways as therapeutic targets in angiotensin II induced atrial fibrillation. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1515864. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1515864

Received: 25 October 2024; Accepted: 30 January 2025;

Published: 03 March 2025.

Edited by:

Ting Shen, Yangzhou University, ChinaReviewed by:

Nobuaki Fukuma, Columbia University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Hou, Shi, Huang, Liu and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Zhang, ZWNobzk5MzI3MkBzaW5hLmNvbQ==