- 1Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, Shandong, China

- 2Institute for Translational Medicine, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, College of Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

- 3Institute of Regenerative Medicine and Laboratory Technology Innovation, Qingdao University, Qingdao, Shandong, China

- 4Department of Ophthalmology, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, Shandong, China

Ferroptosis plays a vital role in the progression of various retinal diseases. The analysis of the mechanism of retinal cell ferroptosis has brought new targeted strategies for treating retinal vascular diseases, retinal degeneration and retinal nerve diseases, and is also a major scientific issue in the field of ferroptosis. In this review, we summarized results from currently available in vivo and in vitro studies of multiple eye disease models, clarified the pathological role and molecular mechanism of ferroptosis in retinal diseases, summed up the existing pharmacological agents targeting ferroptosis in retinal diseases as well as highlighting where future research efforts should be directed for the application of ferroptosis targeting agents. This review indicates that ferroptosis of retinal cells is involved in the progression of age-related/inherited macular degeneration, blue light-induced retinal degeneration, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and retinal damage caused by retinal ischemia-reperfusion via multiple molecular mechanisms. Nearly 20 agents or extracts, including iron chelators and transporters, antioxidants, pharmacodynamic elements from traditional Chinese medicine, ferroptosis-related protein inhibitors, and neuroprotective agents, have a remissioning effect on retinal disease in animal models via ferroptosis inhibition. However, just a limited number of agents have received approval or are undergoing clinical trials for conditions such as iron overload-related diseases. The application of most ferroptosis-targeting agents in retinal diseases is still in the preclinical stage, and there are no clinical trials yet. Future research should focus on the development of more potent ferroptosis inhibitors, improved drug properties, and ideally clinical testing related to retinal diseases.

1 Introduction

Diseases of the retina are a primary factor in causing permanent blindness and vision loss, impacting millions of individuals globally (Hoon et al., 2014). Retinopathy has many classifications that can affect retinal blood vessels, nerves and cells, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD), central retinal artery occlusion and branch artery occlusion, central retinal vein occlusion and branch vein occlusion, retinal detachment, diabetic retinopathy (DR), retinitis pigmentosa (RP), retinal tumor, congenital eye disease and intraocular parasites (Hoon et al., 2014; Mead and Tomarev, 2020). Retinopathy can lead to vision loss, macular edema, retinal detachment, fundus hemorrhage, visual field defects, and in severe cases, blindness, which seriously affects the quality of life of patients. Studying the pathogenesis of retinal diseases and exploring potential treatment strategies are hot spots and difficulties in this field (Kaji et al., 2018; Mead and Tomarev, 2020; Dhurandhar et al., 2021).

Ferroptosis is a programmed death modality of non-apoptotic cells that relies on the accumulation of iron in cells, resulting in an increase in the toxic lipid peroxide reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Jiang et al., 2021). Lipid peroxidation of unsaturated fatty acids that are highly expressed on the cell membrane in response to ferric iron or esteroxygenase induces cell death (Rochette et al., 2022). The characteristics of ferroptosis cells mainly include smaller mitochondria, increased membrane density, decreased cristae, increased intracellular lipid peroxidation, increased ROS, and iron ion aggregation (Jiang et al., 2021; Tang D. et al., 2021). In addition, ferroptosis is also manifested by a decrease in protein GPX4 levels, the core enzyme that regulates the antioxidant system (glutathione system) (Jiang et al., 2021; Tang D. et al., 2021; Li F. et al., 2023).

Iron is essential for retinal metabolism, but an excess of ferrous iron causes oxidative stress, which is one of the main mechanisms for the occurrence of ferroptosis (Youale et al., 2022). Iron overload is essential for ferroptosis execution (Liu K. et al., 2023). Under physiological conditions, circulating ferric irons (Fe3+) that bind to transferrin (TF) are transported into cells via transferrin receptor (TFRC). Inside the cells, Fe3+ undergoes reduction to ferrous (Fe2+) and is then exported by divalent metal transporter one in the cytosol, contributing to the labile iron pool. Excess intracellular free Fe2+ facilitates the reduction of oxygen, generating superoxide radicals, and causes lipid peroxides through Fenton reactions, resulting in ferroptosis finally (Liu K. et al., 2023). Several factors, including hypoxia, overload of all-transetinal (atRAL), high intraocular pressure, aging, and iron metabolism imbalance, lead to abnormal accumulation of iron in cells and retinas by affecting the proteins involved in the iron metabolism and homeostasis (Ugarte et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2021; Vogt et al., 2021; Henning et al., 2022; Yao et al., 2023).

Recently, many studies have shown that ferroptosis plays a vital role in the progression of various retinal diseases, and targeting ferroptosis provides promising potential strategies for the treatment of ferroptosis-related retinal diseases. The analysis of the mechanism of retinal cell ferroptosis has brought new-targeted strategies for the treatment of retinal vascular diseases, retinal degeneration and retinal nerve diseases, and is also a major scientific issue in the field of ferroptosis. In this review, we summarized results from currently available in vivo and in vitro studies of multiple eye disease models, clarified the pathological role and molecular mechanism of ferroptosis in retinal diseases, summed up the existing pharmacological agents targeting ferroptosis in retinal diseases as well as highlighting where future research efforts should be directed for the application of ferroptosis targeting agents.

2 Pathological role of ferroptosis in retinal diseases

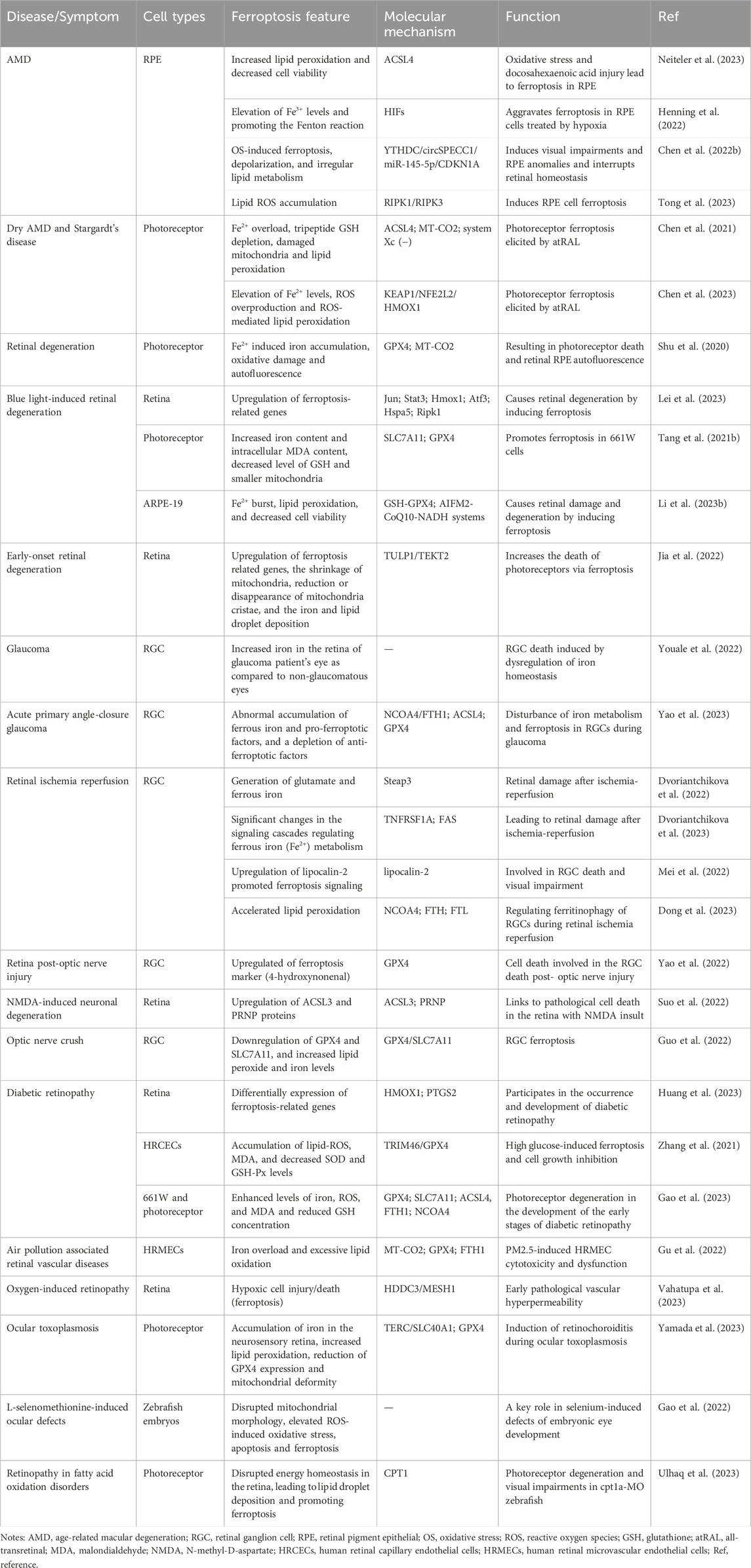

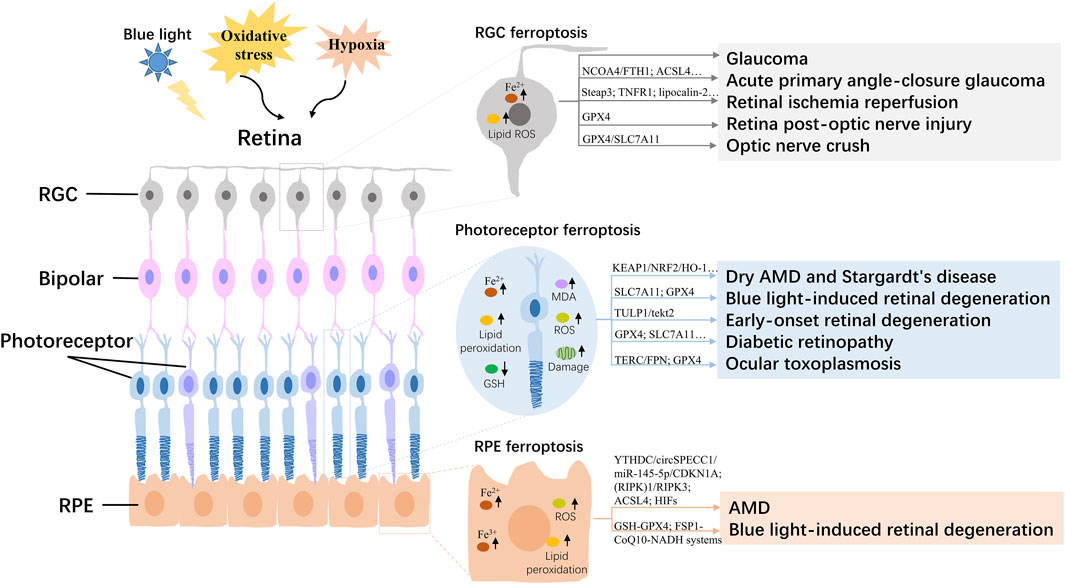

The retina is mainly composed of the inside out of retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE), photoreceptor cells, horizontal cells, bipolar cells, node cells, amacrine cells, and retinal ganglion cells (RGC), as the key part of the vision with the functions that captures light and passes it to the brain (Hoon et al., 2014). Ferroptosis of retinal cells, such as RPE, photoreceptor, and RGC, has been reported to be involved in the progression of age-related/inherited macular degeneration, blue light-induced retinal degeneration, glaucoma, DR, and retinal damage caused by retinal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1. Overview of the regulatory mechanism of ferroptosis in the retina. AMD, age-related macular degeneration; RGC, retinal ganglion cell; RPE, Retinal pigment epithelial; ROS, reactive oxygen species; GSH, glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde.

2.1 Age-related/inherited macular degeneration

The RPE performs many crucial functions, such as phagocytosis, barrier, nutrient transportation, oxidative stress resistance, visual cycle maintenance and factors production, and is essential for the survival and function of the retina (Wang S. et al., 2023). RPE dysfunction and atrophy cause various retinal diseases including AMD. Recent studies showed that ferroptosis in RPE cells participates in the pathogenesis of AMD through multiple molecular regulatory mechanisms (Chen et al., 2021; Chen X. et al., 2022; Henning et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023; Neiteler et al., 2023; Tong et al., 2023) and is a potential therapeutic target for AMD.

Oxidative stress and hypoxia-induced RPE cell death have long been considered to play crucial roles in the initiation and progression of AMD, and ferroptosis was identified as one of the main cell death mechanisms of oxidative stress (Henning et al., 2022; Neiteler et al., 2023). Iron accumulation and altered iron metabolism are characteristic features of AMD retinas and RPE cells (Henning et al., 2022). Oxidative stress and docosahexaenoic acid injury-induced downregulation of ferroptosis regulator acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), increased lipid peroxidation and decreased cell viability, and lead to ferroptosis in RPE (Neiteler et al., 2023). Hypoxia aggravates ferroptosis in RPE cells by elevating Fe3+ levels, and promoting the Fenton reaction (Henning et al., 2022). In RPE of AMD patients, the expression of circSPECC1 is downregulated, and circSPECC1 insufficiency leads to oxidative stress-induced ferroptosis, depolarization, and irregular lipid metabolism via circSPECC1/miR-145-5p/CDKN1A axis, and then induces visual impairments and RPE anomalies and interrupts retinal homeostasis (Chen X. et al., 2022). In addition, RAS-selective lethal three induced-RPE ferroptosis shows the features of receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIPK)1/RIPK3 activation and lipid ROS accumulation (Tong et al., 2023).

Dysfunction of photoreceptors in dry AMD and Stargardt disease (SD) is associated with defects of atRAL clearance (Chen et al., 2021). The overload of atRAL lead to Fe2+ overload, tripeptide glutathione (GSH) depletion, damaged mitochondria and lipid peroxidation in photoreceptors via ACSL4 elevation, system Xc(−) inhibition and MT-CO2 activation, resulting in photoreceptor ferroptosis and dysfunction (Chen et al., 2021). HMOX1 is a key factor that regulates atRAL-induced ferroptosis in photoreceptors via KEAP1/NFE2L2/HMOX1 axis, and its inhibition may be a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of dry AMD and SD (Chen et al., 2023).

2.2 Retinal degeneration induced by blue light or others

Retinal photoreceptors, mainly including rod and cone cells, are a special type of neuroepithelial cells with light transduction ability with the function of converting light signals into neural signals (Zhao and Peng, 2021). Photoreceptor degeneration and death, as one of the main characteristics of retinal degeneration diseases, lead to severe visual impairment (Wang et al., 2024).

Ferroptosis is implicated in the pathogenesis of retinal degeneration. Fe2+ induced iron accumulation, oxidative damage and autofluorescence of photoreceptors, resulting in photoreceptor death and RPE autofluorescence in mouse models (Shu et al., 2020). Light damage is a widely used model for retinal degeneration. In the light damage retina of mice models, ferroptosis genes, such as Jun, Stat3, Hmox1, Atf3, Hspa5 and Ripk1, were significantly upregulated, which suggests the important role of ferroptosis in retinal degeneration (Lei et al., 2023). The photoreceptor cells showed pro-ferroptotic changes after light exposure, including increased iron content and intracellular malondialdehyde (MDA) content, decreased level of GSH, smaller mitochondria and decreased protein expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4, resulting in decreased cell viability in vitro (Tang W. et al., 2021). In addition, light also triggers ROS and Fe2+ burst, lipid peroxidation, and decreased cell viability of RPE cell lines, resulting in retinal damage and degeneration by inducing ferroptosis via GSH-GPX4 and AIFM2-CoQ10-NADH systems (Li X. et al., 2023). Through TULP1 knockout models in zebrafish, scientists found that TULP1 deficiency causes early-onset retinal degeneration through up-regulating ferroptosis-related genes, increasing the shrinkage of mitochondria, iron and lipid droplet deposition and reducing mitochondria cristae, and increasing the death of photoreceptors via ferroptosis (Jia et al., 2022).

2.3 Glaucoma

RGC is located in the innermost layer of the retina, composed of multipolar ganglion cells, and its dendrites are mainly connected to bipolar cells (Masland, 2012). Its axons extend to the optic nerve nipple, pass through the sieve plate, and form the optic nerve, playing a role in transmitting visual signals to the brain (Parisi et al., 2018). RGC degeneration is a common cause of glaucoma and optic neuropathy, which is the main cause of irreversible blindness and visual impairment (Ju et al., 2023).

Pathological high intraocular pressure (pH-IOP) is the main cause of visual impairment in glaucoma patients, which can lead to RGC death and permanent visual impairment (Yao et al., 2023). Research has found that the iron staining is increased in the retina of a glaucoma patient’s eye as compared to non-glaucomatous eyes (Youale et al., 2022). The levels of ferric iron in the peripheral serum of patients with acute primary angle closure glaucoma are significantly higher than the average population, indicating that iron homeostasis is involved in regulating the damage of RGCs under pH IOP (Yao et al., 2023). pH IOP leads to abnormal accumulation of ferrous iron and pro-ferroptotic factors including lipid peroxidation and ACLS4, and depletion of anti-ferroptotic factors, such as GSH, GPX4, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, in RGC cells and retinas via NCOA4/FTH1 axis, thus disrupting iron metabolism and leading to ferroptosis in RGCs during glaucoma (Yao et al., 2023).

2.4 Retinal ischemia-reperfusion

Retinal I/R injury, as a common cause of irreversible visual impairment in clinical can lead to RGC death and is implicated in the pathological process of glaucoma, retinal artery occlusion and DR and other eye diseases. Multiple research results indicate that RGC ferroptosis is involved in the process of retinal damage triggered by I/R (Dvoriantchikova et al., 2022; Mei et al., 2022; Dong et al., 2023; Dvoriantchikova et al., 2023).

RNA-seq data analysis result of a retinal I/R mouse model showed RGC ferroptosis contributes simultaneously to retinal damage after I/R, through Steap3 promoting the glutamate, and ferrous iron generation, which trigger ferroptosis in ischemic RGC (Dvoriantchikova et al., 2022). RGCs isolated from retinas 24 h after IR show that the signaling cascades regulating ferrous iron (Fe2+) metabolism, such as TNFRSF1A and FAS, undergo significant changes, which causes retinal damage after I/R (Dvoriantchikova et al., 2023). After IOP-induced retinal I/R injury, lipocalin-2 transgenic mice showed more aggravated RGC death and visual impairment compared with wild-type mice (Mei et al., 2022). Lipocalin-2 plays an important role in RGC death and visual impairment via strongly promoting ferroptosis signaling (Mei et al., 2022). NCOA4, a cargo receptor for ferritinophagy, is upregulated and accelerates lipid peroxidation in retinal tissues, and regulates ferritinophagy of RGCs during retinal I/R (Dong et al., 2023).

2.5 Optic nerve injury

Irreversible visual impairment and blindness occur as a result of optic nerve injury, with RGC death being a crucial pathological initiator. Following optic nerve injury, ferroptosis emerges as a significant mode of cell death for RGCs (Yao et al., 2022). Following the early reduction of GPX4, the upregulation of the ferroptosis marker (4-hydroxynonenal) was observed in mouse retina between Day 7 and Day 14 post-ON injury, indicating the ferroptosis in RGC (Yao et al., 2022). Ferroptosis is also linked to pathological cell death in the retina with N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) insult (Suo et al., 2022). The ACSL3 and PRNP proteins were upregulated in the NMDA-damaged retina and connected with ferroptosis (Suo et al., 2022). For the optic nerve crush rat models, the RGC shows a reduction of GPX4 and SLC7A11 expression, increased membrane density, reduced mitochondrial cristae, and increased lipid peroxide and iron levels, indicating RGC ferroptosis after optic nerve crush (Guo et al., 2022).

2.6 Diabetic retinopathy

DR is one of the most common microvascular complications of diabetes, which is a series of fundus diseases caused by retinal microvascular leakage and occlusion caused by chronic progressive diabetes. Ferroptosis is involved in the occurrence and development of DR. RNA sequencing results showed that the expression of ferroptosis-related genes in DR retinas changed significantly, and HMOX1 and PTGS2 genes were hub genes of differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes (Huang et al., 2023). High glucose induces accumulation of lipid-ROS and MDA, and decrease of superoxide dismutase and GSH levels in human retinal capillary endothelial cells (HRCECs), then leading to ferroptosis and cell growth inhibition via TRIM46/GPX4 ubiquitination axis, and results in dysfunction in HRCECs (Zhang et al., 2021). In addition, the photoreceptor cells in diabetic mice also showed enhanced levels of iron, ROS, and MDA and reduced GSH concentration with downregulation of GPX4 and SLC7A11, and upregulation of ACSL4, FTH1 and NCOA4, which suggested that ferroptosis is also involved in the pathogenesis of photoreceptor degeneration in the development of the early stages of DR (Gao et al., 2023).

2.7 Other retinal vascular diseases

Ferroptosis is also involved in the pathogenesis of other retinal vascular diseases, such as air pollution associated retinal vascular diseases (Gu et al., 2022) and oxygen-induced retinopathy (Vahatupa et al., 2023). Airborne fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure induces iron overload and excessive lipid oxidation with significantly altered expression of ferroptosis-related genes (MT-CO2, GPX1 and FTH1) in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells, suggesting that ferroptosis plays a crucial role in PM2.5-induced HRMEC cytotoxicity and dysfunction, and is a potential precautionary target in air pollution associated retinal vascular diseases (Gu et al., 2022). Besides, in the retina of Rras knockout mice, hypoxia can cause early pathological vascular hyperpermeability via hypoxic cell injury/death (ferroptosis), indicating an important role of ferroptosis in ischemic retinal diseases (Vahatupa et al., 2023).

2.8 Ocular toxoplasmosis

Ocular toxoplasmosis (OT), as the main clinical manifestation of toxoplasmosis, seriously threatens the patient’s vision. The study found that the iron concentration in the vitreous of human OT patients decreased significantly, suggesting that ferroptosis is involved in the pathogenesis of OT (Yamada et al., 2023). The eyes after infecting toxoplasma gondii showed accumulation of iron in the neurosensory retina, and increased lipid peroxidation, reduction of GPX4 expression and mitochondrial deformity in the photoreceptor, suggesting that ferroptosis plays a crucial role in the induction of retinochoroiditis during ocular toxoplasmosis (Yamada et al., 2023).

2.9 Other ocular defects in zebrafish

In zebrafish embryos, excessive selenium disrupted mitochondrial morphology and elevated ROS-induced oxidative stress, apoptosis and ferroptosis (Gao et al., 2022). Ferroptosis plays a key role in l-selenomethionine-induced defects of embryonic eye development (Gao et al., 2022). The deficiency of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1) was reported to disrupt energy homeostasis in the retina, leading to lipid droplet deposition and promoting ferroptosis in zebrafish models, which is attributed to the photoreceptor degeneration and visual impairments of fatty acid oxidation disorders (Ulhaq et al., 2023).

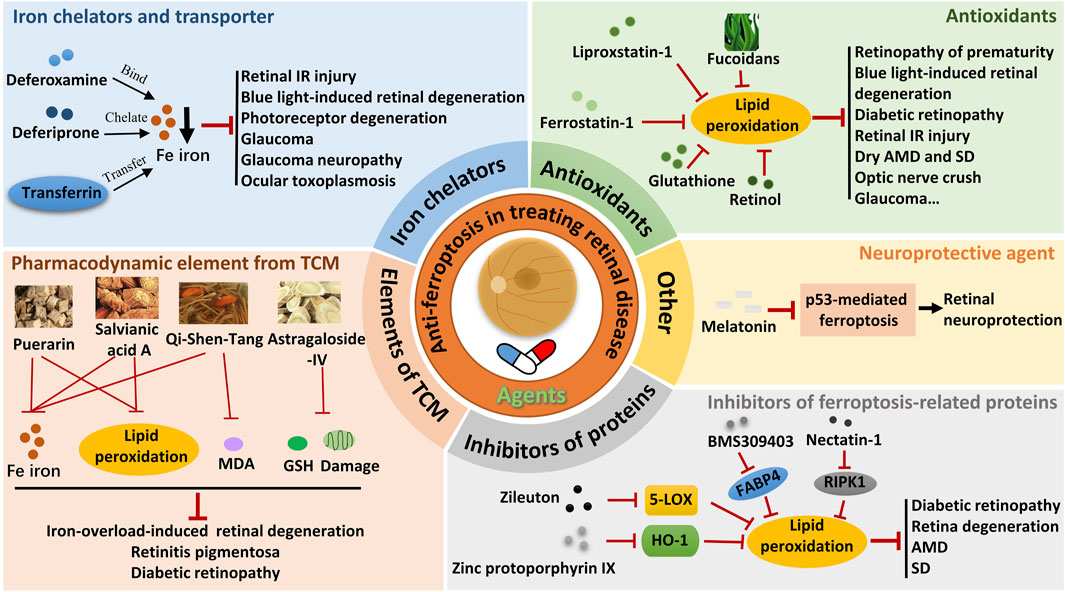

3 Pharmacological agents targeting ferroptosis in retinal diseases

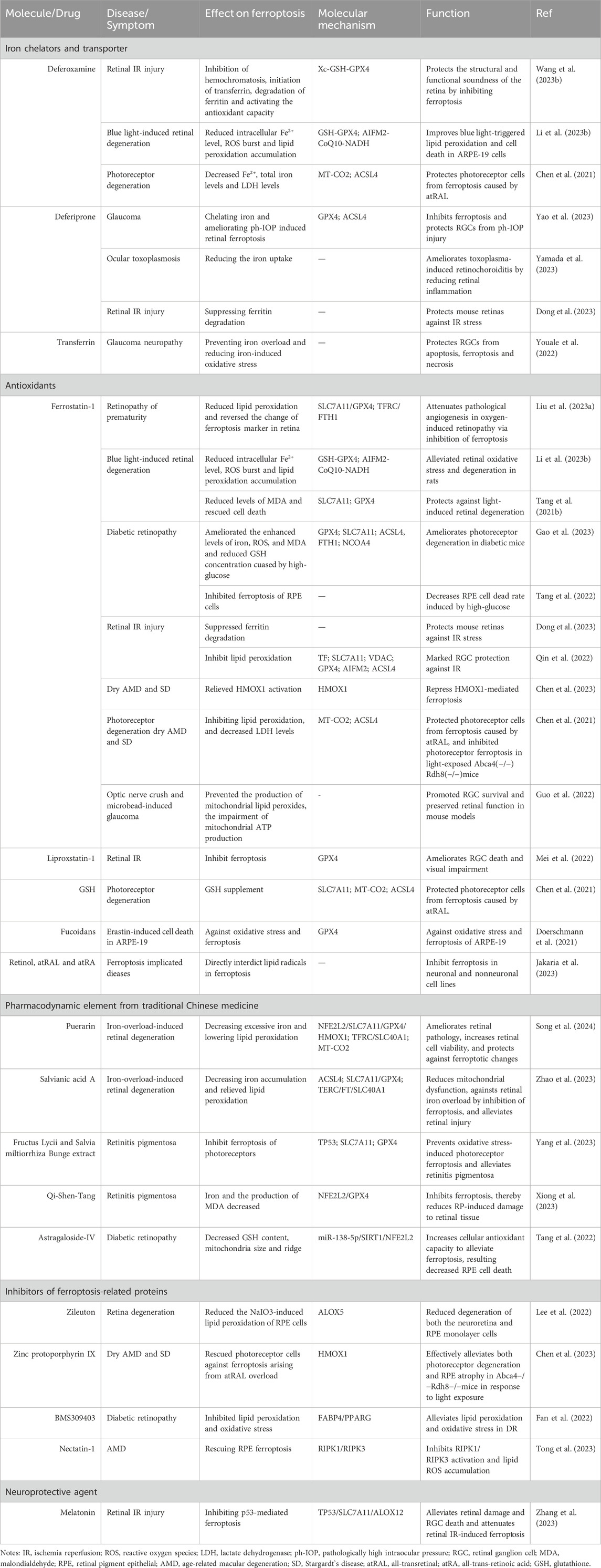

The critical role of retinal cell ferroptosis in various retinal diseases suggests a potential therapeutic role of ferroptosis inhibitors in related diseases. Ferroptosis inhibitors mainly act by reducing free iron, eliminating free radicals, and inhibiting lipid oxidation. Nearly 20 agents and extracts, including iron chelators and transporter, antioxidants, pharmacodynamic element from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), ferroptosis-related protein inhibitors, and neuroprotective agent that inhibit ferroptosis have been reported to have a remissioning effect on retinal disease in animal models (Table 2; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Therapeutic strategies targeting ferroptosis in retinal diseases. IR, ischemia-reperfusion; MDA, malondialdehyde; AMD, age-related macular degeneration; SD, Stargardt’s disease; GSH, glutathione; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

3.1 Iron chelators and transporter

3.1.1 Deferoxamine

Deferoxamine (DFO) is an iron chelator (binds Fe (III) and many other metal cations) that is widely used to reduce the accumulation and deposition of iron in tissues. Through the inhibition of hemochromatosis, initiation of transferrin, degradation of ferritin and activation the antioxidant capacity, DFO protects the structural and functional soundness of the retina by inhibiting ferroptosis in the rat models of retinal I/R injury [33]. On the other hand, DFO improves blue light-triggered lipid peroxidation and cell death in ARPE-19 cells via reducing intracellular Fe2+ level, ROS burst and lipid peroxidation accumulation in the model of blue light-induced retinal damage and degeneration (Li X. et al., 2023). Furthermore, DFO protects photoreceptor cells from ferroptosis caused by atRAL by decreasing Fe2+ levels, total iron levels, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (Chen et al., 2021). Via inhibition of ferroptosis, DFO has the potential to attenuate and against various retinal damage and degeneration and offer new strategies for treating ferroptosis-related retinal diseases.

3.1.2 Deferiprone

Deferiprone (DFP) is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved oral active iron chelator with brain permeability, cell permeability and skin permeability, which is currently used in the clinical treatment of iron overload. In vivo studies have demonstrated that the oral intake of DFP effectively binds to iron and improves the condition of retinal ferroptosis induced by ph-IOP (Yao et al., 2023). Furthermore, it inhibits ferroptosis and safeguards RGCs against ph-IOP-related damage (Yao et al., 2023). These findings offer valuable insights into the role of iron homeostasis and ferroptosis pathways in the understanding and treatment of glaucoma. Furthermore, the iron uptake was diminished by DFP while simultaneously improving the condition of retinochoroiditis caused by toxoplasma through the reduction of retinal inflammation (Yamada et al., 2023). This presents a promising therapeutic option for OT. In addition, it was reported that DFP inhibits the breakdown of ferritin, limits cell death and inflammation, and safeguards the retinas of mice from I/R stress (Dong et al., 2023).

3.1.3 Transferrin

TF serves as an endogenous iron transporter that plays a crucial role in regulating iron levels within the eye. By preventing iron overload and reducing oxidative stress caused by iron, the intraocular delivery of TF has been found to have neuroprotective effects in various retinal degeneration models (Bigot et al., 2020). TF also has the ability to intervene in apoptosis, ferroptosis and necrosis associated with glaucoma pathogenesis, demonstrating its potential to shield RGCs from elevated intraocular pressure (Youale et al., 2022). These collective findings suggest that TF could be a promising treatment for glaucomatous neuropathy.

3.2 Antioxidants

3.2.1 Ferrostatin-1

Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1, C15H22N2O2), as an artificially synthesized antioxidantis, is a potent and selective inhibitor of ferroptosis. Via inhibition of ferroptosis, Fer-1 has the potential to attenuate and against various retinal damage and degeneration, and provides new potential strategies for the treatment of ferroptosis-related retinal diseases.

In a mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy, Fer-1 administration attenuates pathological angiogenesis in the retina via inhibition of ferroptosis, suggesting a promising target for retinopathy of prematurity therapy (Liu C.-Q. et al., 2023). Fer-1 alleviates ferroptosis and protects the retina against light-induced retinal degeneration in rats (Tang W. et al., 2021; Li X. et al., 2023). Via inhibition of ferroptosis, Fer-1 ameliorates photoreceptor degeneration and decreases the RPE cell death rate caused by high glucose, and has also shown potential therapeutic effects in DR (Tang et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2023). In mouse models of retinal I/R, Fer-1 administration suppressed ferritin degradation and lipid peroxidation, restrained apoptosis and inflammation of the retina, inhibited RGC death, and protected mouse retinas against I/R stress (Qin et al., 2022; Dong et al., 2023). Fer-1 administered intraperitoneally also shows potential in treating dry AMD and SD by inhibiting atRAL-induced ferroptosis in photoreceptor and RPE cells of light-exposed Abca4(−/−)Rdh8(−/−)mice (Chen et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2023). Fer-1 demonstrated a substantial enhancement in the survival of RGC and the preservation of retinal function in mouse models of optic nerve crush and microbead-induced glaucoma (Guo et al., 2022). This compound holds the potential as a protective approach for mitigating RGC injuries in optic neuropathies.

3.2.2 Liproxstatin-1

Liproxstatin-1 (C19H21ClN4) is a potent inhibitor of ferroptosis with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, able to inhibit ferroptosis in the low nanomolar range. Liproxstatin-1 could significantly ameliorate RGC death and visual impairment in the pathogenesis of ischemic retinopathy, indicating its potential as a treatment for retinal IR (Mei et al., 2022).

3.2.3 Glutathione

GSH is a cofactor of GPX4, a lipid peroxidase that inhibits ferroptosis. GSH supplement protects photoreceptor cells from ferroptosis caused by atRAL, and may provide a new strategy for protection against dry AMD and SD (Chen et al., 2021).

3.2.4 Fucoidans

Fucoidans, derived from various algae species such as F. serratus, F. distichus subsp. evanescens, and Laminaria hyperborea, have been shown to possess protective properties against oxidative stress. Specifically, these fucoidans have been found to mitigate the reduction in protein levels of the antioxidant enzyme GPX4, offering partial protection against erastin-induced oxidative stress and ferroptosis in ARPE-19 cells (Doerschmann et al., 2021). These results indicate that fucoidans with protective qualities could potentially serve as therapeutic agents for conditions related to ARP ferroptosis. Further research is necessary to fully understand the beneficial effects of fucoidans on health and to elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying their antioxidative properties.

3.2.5 Vitamin A metabolites

Vitamin A, also known as retinol, is a fat-soluble vitamin that serves as a precursor for various bioactive substances, including retinaldehyde (retinal) and different forms of retinoic acid (Jakaria et al., 2023). Retinol and its metabolites, such as atRAL and all-trans-retinoic acid, have the ability to prevent ferroptosis in both neuronal and nonneuronal cell types by directly blocking lipid radicals (Jakaria et al., 2023). These compounds could potentially be used as treatments for conditions associated with ferroptosis. It has been noted that excessive concentrations of retinoids can be toxic to retinal cells (Chen et al., 2021; Jakaria et al., 2023). As a result, establishing the correct dosage concentration is an important consideration that should be taken into account in upcoming clinical trials.

3.3 Pharmacodynamic elements from traditional Chinese medicine

3.3.1 Puerarin

Puerarin (C21H20O9), a natural isoflavone derived from Pueraria lobata and utilized in traditional Chinese herbal medicine, has been proven to possess preventive properties against iron overload (Song et al., 2020). Its efficacy in mitigating iron overload-induced ferroptosis by decreasing excessive iron and lowering lipid peroxidation in the retina through an NFE2L2-mediated mechanism, ameliorates retinal pathology, increases retinal cell viability, protects against ferroptotic changes in mouse models, which highlights its potential as a novel approach in managing retinal degeneration (Song et al., 2024).

3.3.2 Salvianic acid A

Salvianic acid A (C9H10O5) is a significant pharmacodynamic element present in the water-soluble components of Salvia miltiorrhiza herb. It was reported to possess antioxidative properties and act as an anti-inflammatory agent in cases of liver injury due to iron overload (Zhang Y. et al., 2020). Through Decreasing iron accumulation and relieving lipid peroxidation, salvianic acid A is effective in reducing mitochondrial dysfunction, inhibiting ferroptosis to combat retinal iron overload, and alleviating retinal damage in iron overload mouse models, and holds potential as an innovative treatment strategy for retinal degeneration caused by iron overload (Zhao et al., 2023).

3.3.3 Fructus Lycii and Salvia mTCNiltiorrhiza bunge extract

Fructus Lycii (Gouqizi) and Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Danshen) are commonly utilized in TCM for addressing deficiencies, improving blood circulation, or as daily nutritional supplements (Amagase et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2019). The use of extracts from Fructus Lycii and Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge can help prevent oxidative stress-induced photoreceptor ferroptosis and reduce the severity of RP by inhibiting photoreceptor ferroptosis through the TP53/SLC7A11 pathway (Yang et al., 2023).

Furthermore, another investigation revealed that Qi-Shen-Tang, a TCM formula containing Gouqizi and Danshen in a 1:1 ratio, can suppress ferroptotic characteristics of the retina in mice with RP by blocking the NFE2L2/GPX4 signaling pathway (Xiong et al., 2023). This ultimately leads to a decrease in retinal tissue damage caused by RP. These findings suggest that these herbal extracts could be beneficial in clinical treatments for RP.

3.3.4 Astragaloside-IV

Decoctions made from the roots of Astragalus membranaceus, commonly referred to as “Huangqi,” have been extensively utilized in TCM to address viral and bacterial infections as well as inflammation (Zhang J. et al., 2020). Astragaloside IV (AS-IV, C41H68O14), a significant component found in the aqueous extract of Astragalus membranaceus, is a cycloartane-type triterpene glycoside with proven biological properties (Zhang J. et al., 2020). Laboratory experiments have revealed that AS-IV reduces GSH levels, alters the size and structure of mitochondria in RPE cells, enhances cellular antioxidant capabilities to mitigate ferroptosis, and ultimately decreases high glucose-induced RPE cell death through the miR-138-5p/SIRT1/NFE2L2 pathway (Tang et al., 2022). The findings suggest that AS-IV can alleviate ferroptosis triggered by high glucose in RPE cells, indicating its potential as a treatment for diabetic retinopathy.

3.4 Inhibitors of ferroptosis-related proteins

3.4.1 Lipoxygenase inhibitor

Lipoxygenases (LOXs) are enzymes that metabolize arachidonic acid and polyunsaturated fatty acids, leading to lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis induction (Stockwell et al., 2017). Zileuton, a specific inhibitor of ALOX5, decreased NaIO3-induced lipid peroxidation in RPE cells, as well as the degeneration of neuroretina and RPE monolayer cells (Lee et al., 2022). This suggests that Zileuton could be a valuable strategy in managing ROS and ferroptosis-induced damage, which contribute to degeneration in retinal diseases.

3.4.2 Zinc protoporphyrin IX

HMOX1 plays a crucial role in controlling atRAL-induced ferroptosis in photoreceptors and the RPE (Chen et al., 2023). Zinc protoporphyrin IX, acting as an inhibitor of HMOX1, protected photoreceptor cells from ferroptosis caused by atRAL overload (Chen et al., 2023). This intervention effectively reduced both photoreceptor degeneration and RPE atrophy in Abca4−/−Rdh8−/−mice exposed to light, indicating the potential of zinc protoporphyrin IX for treating dry AMD and SD (Chen et al., 2023).

3.4.3 BMS309403

BMS-309403 (C31H26N2O3) demonstrates strong inhibitory effects on adipocyte fatty acid binding protein (FABP) and is orally active and selective. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have confirmed that treatment with BMS309403 effectively suppresses lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress, and ferroptosis in DR by modulating FABP4/PPARG-mediated ferroptosis (Fan et al., 2022). These findings suggest that BMS-309403 holds promise as a therapeutic option for retinal DR.

3.4.4 Necrostatin-1

Necrostatin-1 (C13H13N3OS) is an inhibitor of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1). As the RIPK1-targeted inhibitor of necroptosis, necrostatin-1 could both rescue the ferroptosis and necroptosis of RPE cells via inhibiting RIPK1/RIPK3 activation and lipid ROS accumulation (Tong et al., 2023). This compound shows promise as a potential treatment for geographic atrophy in AMD.

3.5 Neuroprotective agent

Acetyl–5–methoxytryptamine, also known as melatonin (C13H16N2O2), is a hormone that is secreted by the pineal gland in the brain, and shows great potential as a neuroprotective agent (Su et al., 2015). A recent study has shown that melatonin has the ability to alleviate retinal damage and RGC death and protect against retinal I/R injury by inhibiting TP53-mediated ferroptosis (Zhang et al., 2023). This finding indicates that melatonin is a specific ferroptosis inhibitor that can defer damage to the retina, making it a promising therapeutic agent for retinal neuroprotection.

4 Challenges for the application of ferroptosis targeting agents

4.1 Approved ferroptosis targeting agents

Given the novel role of ferroptosis in the pathogenesis of various retinal diseases, ferroptosis is a promising therapeutic target. Currently, a limited number of iron chelators have received approval from the FDA or are undergoing clinical trials for conditions such as iron overload-related diseases, organ damage, and transplants (Ballas et al., 2018). DFO was the first iron chelator to be approved for subcutaneous or intravenous administration, with treatment lasting up to 10–12 h for chronic iron overload caused by blood transfusions. Exjade (deferasirox) is the first oral iron chelator approved by the FDA. Initially indicated for chronic transfusion-induced iron overload in children aged two and above, it was later approved in 2013 for patients aged 10 and older with non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia syndrome, a condition characterized by chronic iron overload. Additionally, reduced glutathione eye drops (ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical) code: V03AB32) have been given the green light for treating conditions like corneal ulcers, corneal epithelium peeling, keratitis, and early senile cataracts. Zileuton (DrugBank Accession Number: DB00744) has been approved for both the prophylaxis and chronic treatment of asthma in both adults and children. Puerarin (DrugBank Accession Number: DB12290) was approved for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases in China in 1993. Melatonin (ATC code: N05CH01) has been approved for use in autism spectrum disorders, Smith Magnis syndrome, as well as indications for falling asleep and sleep disorders. The FDA has approved the designation of EYS611 (a DNA plasmid encoding human transferrin) developed by Eyevensys as an orphan drug for the treatment of RP degeneration (Bigot et al., 2020). The application of most ferroptosis-targeting agents in retinal diseases is still in the preclinical stage of new drug development, and there are no clinical trials yet. This will be an important direction for future research.

4.2 Prospects of the pharmacodynamic element from TCM

Previous studies have shown that by targeting ferroptosis, some pharmacodynamic elements from TCM have certain effects or unique advantages in retinal diseases, and have potential research value for the efficacy of related retinopathy (Tang et al., 2022; Xiong et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023; Song et al., 2024). Through a well-designed clinical research approach, the advancement of research on treating retinal diseases with TCM can be facilitated. How to explore new TCM drugs that may have clinical value for retinal ferroptosis-related diseases based on TCM theory and clinical efficacy, and confirm the clinical efficacy based on reliable data, is a scientific problem that needs to be solved urgently in the research and development of new TCM drugs related to retinal diseases.

4.3 Limitations of ferroptosis targeting agents

The discovery of these potential therapeutic drugs provides some new perspectives and options for the treatment of retina-related diseases. However, some limitations may hinder the use of these potential drugs in clinical settings. With regard to the long-term use of iron chelators in patients with chronic diseases, these patients may experience specific side effects, such as rash, nausea and dizziness, diarrhea, vomiting, hearing and vision loss, abdominal pain, and increasing risk of infection (Mobarra et al., 2016; Entezari et al., 2022). The biological half-life of Fer-1 is only a few minutes, and the unsatisfactory pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles are generally unacceptable for clinical applications (Chen J. et al., 2022). The oral administration of AS-IV results in a bioavailability of 7.4% in beagle dogs and 3.66% in rats (Zhang J. et al., 2020). This limited absolute bioavailability hinders its potential for oral use.

4.4 Questions need to be solved urgently

The therapeutic effects of ferroptosis inhibitors on retina-related diseases have been shown to be effective in preclinical trials. Future research should focus on the development of more potent ferroptosis inhibitors, improved drug properties, and ideally clinical testing related to retinal diseases.

With the development of modern ophthalmic examination technology and wide clinical application, fundus manifestations such as retinal vascular morphology and lesions can be visualized, which is helpful in observing the physiological and pathological changes during the progression of retinal diseases. In the clinical practice of ferroptosis, the correlation between retinal ferroptosis and visual acuity, fundus manifestations, objective imaging examinations of the eye, and biochemical examination indicators are explored to provide support for further accurate clinical positioning.

In addition, there are several key issues to be addressed for the further development of clinical development of ferroptosis-targeting drugs. What is the physiological role of ferroptosis in the eye? In the context of retinal disease, more evidence is needed to provide a complete view of the dynamic processes of ferroptosis that drive retinal degeneration. Can we identify reliable, sensitive biomarkers of ferroptosis in the retina? When should we use targeted ferroptosis drugs for specific pathological vision conditions, fundus manifestations, and/or stages of disease? What dosing modalities and regimens are used in the treatment of the retina without affecting other cells? What strategies can be implemented to enhance pharmacokinetic characteristics like oral bioavailability, half-life, and organ distribution to maximize the therapeutic efficacy of ferroptosis-targeted drugs? Addressing the key scientific questions discussed in this review will improve our understanding of the precise role of ferroptosis in various retinal diseases, thereby providing a new scientific basis for the prevention and treatment of retinal diseases with ferroptosis-targeted drugs.

5 Conclusion

Ferroptosis plays a vital role in the progression of various retinal diseases. Ferroptosis of retinal cells, such as RPE, photoreceptor, and RGC, has been reported to be involved in the progression of age-related/inherited macular degeneration, blue light-induced retinal degeneration, glaucoma, DR, and retinal damage caused by retinal IR via multiple molecular mechanisms. The analysis of the mechanism of retinal cell ferroptosis has brought new targeted strategies for the treatment of retinal vascular diseases, retinal degeneration, and retinal nerve diseases. Ferroptosis inhibitors mainly act by reducing free iron, eliminating free radicals, and inhibiting lipid oxidation. Nearly 20 agents and extracts, including iron chelators and transporter, antioxidants, pharmacodynamic elements from TCM, ferroptosis-related protein inhibitors, and neuroprotective agent have been reported to have a remissioning effect on retinal disease in animal models via inhibiting ferroptosis. However, just a limited number of iron chelators have received approval from the FDA or are undergoing clinical trials for conditions such as iron overload-related diseases, organ damage, and transplants. The application of most ferroptosis-targeting agents in retinal diseases is still in the preclinical stage of new drug development, and there are no clinical trials yet. This will be an important direction for future research. The therapeutic effects of ferroptosis inhibitors on retina-related diseases have been shown to be effective in preclinical trials. Future research should focus on the development of more potent ferroptosis inhibitors, improved drug properties, and ideally clinical testing related to retinal diseases.

Author contributions

X-DH: Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft. W-HX: Writing–review and editing. XZ: Writing–review and editing. JX: Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (ZR2020MC059 and RH2200000157).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Amagase, H., Sun, B., and Borek, C. (2009). Lycium barbarum (goji) juice improves in vivo antioxidant biomarkers in serum of healthy adults. Nutr. Res. 29 (1), 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2008.11.005

Ballas, S. K., Zeidan, A. M., Duong, V. H., DeVeaux, M., and Heeney, M. M. (2018). The effect of iron chelation therapy on overall survival in sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia: a systematic review. Am. J. Hematol. 93 (7), 943–952. doi:10.1002/ajh.25103

Bigot, K., Gondouin, P., Benard, R., Montagne, P., Youale, J., Piazza, M., et al. (2020). Transferrin non-viral gene therapy for treatment of retinal degeneration. Pharmaceutics 12 (9), 836. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics12090836

Chen, C., Chen, J., Wang, Y., Liu, Z., and Wu, Y. (2021). Ferroptosis drives photoreceptor degeneration in mice with defects in all-trans-retinal clearance. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100187. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA120.015779

Chen, C., Yang, K., He, D., Yang, B., Tao, L., Chen, J., et al. (2023). Induction of ferroptosis by HO-1 contributes to retinal degeneration in mice with defective clearance of all-trans-retinal. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 194, 245–254. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.12.008

Chen, J., Li, X., Ge, C., Min, J., and Wang, F. (2022a). The multifaceted role of ferroptosis in liver disease. Cell Death Differ. 29 (3), 467–480. doi:10.1038/s41418-022-00941-0

Chen, X., Wang, Y., Wang, J.-N., Cao, Q.-C., Sun, R.-X., Zhu, H.-J., et al. (2022b). m6A modification of circSPECC1 suppresses RPE oxidative damage and maintains retinal homeostasis. Cell Rep. 41 (7), 111671. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111671

Dhurandhar, D., Sahoo, N. K., Mariappan, I., and Narayanan, R. (2021). Gene therapy in retinal diseases: a review. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 69 (9), 2257–2265. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_3117_20

Doerschmann, P., Apitz, S., Hellige, I., Neupane, S., Alban, S., Kopplin, G., et al. (2021). Evaluation of the effects of fucoidans from fucus species and Laminaria hyperborea against oxidative stress and iron-dependent cell death. Mar. Drugs 19 (10), 557. doi:10.3390/md19100557

Dong, X., Zhang, Z., Yu, N., Shi, H., Lin, L., and Hou, Y. (2023). A novel role of ARA70 in regulating ferritinophagy of RGCs during retinal ischemia reperfusion. DNA Cell Biol. 42 (11), 668–679. doi:10.1089/dna.2023.0077

Dvoriantchikova, G., Adis, E., Lypka, K., and Ivanov, D. (2023). Various forms of programmed cell death are concurrently activated in the population of retinal ganglion cells after ischemia and reperfusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (12), 9892. doi:10.3390/ijms24129892

Dvoriantchikova, G., Lypka, K. R., Adis, E. V., and Ivanov, D. (2022). Multiple types of programmed necrosis such as necroptosis, pyroptosis, oxytosis/ferroptosis, and parthanatos contribute simultaneously to retinal damage after ischemia-reperfusion. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 17152. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-22140-0

Entezari, S., Haghi, S. M., Norouzkhani, N., Sahebnazar, B., Vosoughian, F., Akbarzadeh, D., et al. (2022). Iron chelators in treatment of iron overload. J. Toxicol. 2022, 4911205. doi:10.1155/2022/4911205

Fan, X. e., Xu, M., Ren, Q., Fan, Y., Liu, B., Chen, J., et al. (2022). Downregulation of fatty acid binding protein 4 alleviates lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress in diabetic retinopathy by regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-mediated ferroptosis. Bioengineered 13 (4), 10540–10551. doi:10.1080/21655979.2022.2062533

Gao, M., Hu, J., Zhu, Y., Wang, X., Zeng, S., Hong, Y., et al. (2022). Ferroptosis and apoptosis are involved in the formation of L-selenomethionine-induced ocular defects in zebrafish embryos. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (9), 4783. doi:10.3390/ijms23094783

Gao, S., Gao, S., Wang, Y., Li, N., Yang, Z., Yao, H., et al. (2023). Inhibition of ferroptosis ameliorates photoreceptor degeneration in experimental diabetic mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (23), 16946. doi:10.3390/ijms242316946

Gu, Y., Hao, S., Liu, K., Gao, M., Lu, B., Sheng, F., et al. (2022). Airborne fine particulate matter (PM2.5) damages the inner blood-retinal barrier by inducing inflammation and ferroptosis in retinal vascular endothelial cells. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 156563. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156563

Guo, M., Zhu, Y., Shi, Y., Meng, X., Donga, X., Zhang, H., et al. (2022). Inhibition of ferroptosis promotes retina ganglion cell survival in experimental optic neuropathies. Redox Biol. 58, 102541. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2022.102541

Henning, Y., Blind, U. S., Larafa, S., Matschke, J., and Fandrey, J. (2022). Hypoxia aggravates ferroptosis in RPE cells by promoting the Fenton reaction. Cell Death and Dis. 13 (7), 662. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-05121-z

Hoon, M., Okawa, H., Della Santina, L., and Wong, R. O. (2014). Functional architecture of the retina: development and disease. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 42, 44–84. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2014.06.003

Huang, Y., Peng, J., and Liang, Q. (2023). Identification of key ferroptosis genes in diabetic retinopathy based on bioinformatics analysis. Plos One 18 (1), e0280548. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280548

Jakaria, M., Belaidi, A. A., Bush, A. I., and Ayton, S. (2023). Vitamin A metabolites inhibit ferroptosis. Biomed. and Pharmacother. 164, 114930. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114930

Jia, D., Gao, P., Lv, Y., Huang, Y., Reilly, J., Sun, K., et al. (2022). Tulp1 deficiency causes early-onset retinal degeneration through affecting ciliogenesis and activating ferroptosis in zebrafish. Cell Death and Dis. 13 (11), 962. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-05372-w

Jiang, X., Stockwell, B. R., and Conrad, M. (2021). Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22 (4), 266–282. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8

Ju, W. K., Perkins, G. A., Kim, K. Y., Bastola, T., Choi, W. Y., and Choi, S. H. (2023). Glaucomatous optic neuropathy: mitochondrial dynamics, dysfunction and protection in retinal ganglion cells. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 95, 101136. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101136

Kaji, H., Nagai, N., Nishizawa, M., and Abe, T. (2018). Drug delivery devices for retinal diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 128, 148–157. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2017.07.002

Lee, J.-J., Chang-Chien, G.-P., Lin, S., Hsiao, Y.-T., Ke, M.-C., Chen, A., et al. (2022). 5-Lipoxygenase inhibition protects retinal pigment epithelium from sodium iodate-induced ferroptosis and prevents retinal degeneration. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 1792894. doi:10.1155/2022/1792894

Lei, X.-L., Yang, Q.-L., Wei, Y.-Z., Qiu, X., Zeng, H.-Y., Yan, A.-M., et al. (2023). Identification of a novel ferroptosis-related gene signature associated with retinal degeneration induced by light damage in mice. Heliyon 9 (12), e23002. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23002

Li, F., Li, P. F., and Hao, X. D. (2023a). Circular RNAs in ferroptosis: regulation mechanism and potential clinical application in disease. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1173040. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1173040

Li, X., Zhu, S., and Qi, F. (2023b). Blue light pollution causes retinal damage and degeneration by inducing ferroptosis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B-Biology 238, 112617. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2022.112617

Liu, C.-Q., Liu, X.-Y., Ouyang, P.-W., Liu, Q., Huang, X.-M., Xiao, F., et al. (2023a). Ferrostatin-1 attenuates pathological angiogenesis in oxygen-induced retinopathy via inhibition of ferroptosis. Exp. Eye Res. 226, 109347. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2022.109347

Liu, K., Li, H., Wang, F., and Su, Y. (2023b). Ferroptosis: mechanisms and advances in ocular diseases. Mol. Cell Biochem. 478 (9), 2081–2095. doi:10.1007/s11010-022-04644-5

Masland, R. H. (2012). The neuronal organization of the retina. Neuron 76 (2), 266–280. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.002

Mead, B., and Tomarev, S. (2020). Extracellular vesicle therapy for retinal diseases. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 79, 100849. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100849

Mei, T., Wu, J., Wu, K., Zhao, M., Luo, J., Liu, X., et al. (2022). Lipocalin 2 induces visual impairment by promoting ferroptosis in retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann. Transl. Med. 11, 3. doi:10.21037/atm-22-3298

Mobarra, N., Shanaki, M., Ehteram, H., Nasiri, H., Sahmani, M., Saeidi, M., et al. (2016). A review on iron chelators in treatment of iron overload syndromes. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Res. 10 (4), 239–247.

Neiteler, A., Palakkan, A. A., Gallagher, K. M., and Ross, J. A. (2023). Oxidative stress and docosahexaenoic acid injury lead to increased necroptosis and ferroptosis in retinal pigment epithelium. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 21143. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-47721-5

Parisi, V., Oddone, F., Ziccardi, L., Roberti, G., Coppola, G., and Manni, G. (2018). Citicoline and retinal ganglion cells: effects on morphology and function. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 16 (7), 919–932. doi:10.2174/1570159X15666170703111729

Qin, Q., Yu, N., Gu, Y., Ke, W., Zhang, Q., Liu, X., et al. (2022). Inhibiting multiple forms of cell death optimizes ganglion cells survival after retinal ischemia reperfusion injury. Cell Death and Dis. 13 (5), 507. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-04911-9

Rochette, L., Dogon, G., Rigal, E., Zeller, M., Cottin, Y., and Vergely, C. (2022). Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism: two corner stones in the homeostasis control of ferroptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (1), 449. doi:10.3390/ijms24010449

Shi, M., Huang, F., Deng, C., Wang, Y., and Kai, G. (2019). Bioactivities, biosynthesis and biotechnological production of phenolic acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59 (6), 953–964. doi:10.1080/10408398.2018.1474170

Shu, W., Baumann, B. H., Song, Y., Liu, Y., Wu, X., and Dunaief, J. L. (2020). Ferrous but not ferric iron sulfate kills photoreceptors and induces photoreceptor -dependent RPE autofluorescence. Redox Biol. 34, 101469. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2020.101469

Song, Q., Jian, W., Zhang, Y., Li, Q., Zhao, Y., Liu, R., et al. (2024). Puerarin attenuates iron overload-induced ferroptosis in retina through a nrf2-mediated mechanism. Mol. Nutr. and Food Res. 68, e2300123. doi:10.1002/mnfr.202300123

Song, Q., Zhao, Y., Li, Q., Han, X., and Duan, J. (2020). Puerarin protects against iron overload-induced retinal injury through regulation of iron-handling proteins. Biomed. Pharmacother. 122, 109690. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109690

Stockwell, B. R., Friedmann Angeli, J. P., Bayir, H., Bush, A. I., Conrad, M., Dixon, S. J., et al. (2017). Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell 171 (2), 273–285. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021

Su, L. Y., Li, H., Lv, L., Feng, Y. M., Li, G. D., Luo, R., et al. (2015). Melatonin attenuates MPTP-induced neurotoxicity via preventing CDK5-mediated autophagy and SNCA/α-synuclein aggregation. Autophagy 11 (10), 1745–1759. doi:10.1080/15548627.2015.1082020

Suo, L., Dai, W., Chen, X., Qin, X., Li, G., Song, S., et al. (2022). Proteomics analysis of N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced cell death in retinal and optic nerves. J. Proteomics 252, 104427. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2021.104427

Tang, D., Chen, X., Kang, R., and Kroemer, G. (2021a). Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 31 (2), 107–125. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1

Tang, W., Guo, J., Liu, W., Ma, J., and Xu, G. (2021b). Ferrostatin-1 attenuates ferroptosis and protects the retina against light-induced retinal degeneration. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 548, 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.02.055

Tang, X., Li, X., Zhang, D., and Han, W. (2022). Astragaloside-IV alleviates high glucose-induced ferroptosis in retinal pigment epithelial cells by disrupting the expression of miR-138-5p/Sirt1/Nrf2. Bioengineered 13 (4), 8240–8254. doi:10.1080/21655979.2022.2049471

Tong, Y., Wu, Y., Ma, J., Ikeda, M., Ide, T., Griffin, C. T., et al. (2023). Comparative mechanistic study of RPE cell death induced by different oxidative stresses. Redox Biol. 65, 102840. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2023.102840

Ugarte, M., Osborne, N. N., Brown, L. A., and Bishop, P. N. (2013). Iron, zinc, and copper in retinal physiology and disease. Surv. Ophthalmol. 58 (6), 585–609. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.12.002

Ulhaq, Z. S., Ogino, Y., and Tse, W. K. F. (2023). Deciphering the pathogenesis of retinopathy associated with carnitine palmitoyltransferase I deficiency in zebrafish model. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 664, 100–107. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.04.096

Vahatupa, M., Nattinen, J., Aapola, U., Uusitalo-Jarvinen, H., Uusitalo, H., and Jarvinen, T. A. H. (2023). Proteomics analysis of R-ras deficiency in oxygen induced retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (9), 7914. doi:10.3390/ijms24097914

Vogt, A. S., Arsiwala, T., Mohsen, M., Vogel, M., Manolova, V., Bachmann, M. F., et al. (2021). On iron metabolism and its regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (9). doi:10.3390/ijms22094591

Wang, S., Li, W., Chen, M., Cao, Y., Lu, W., and Li, X. (2023a). The retinal pigment epithelium: functions and roles in ocular diseases. Fundam. Res. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.fmre.2023.08.011

Wang, X., Li, M., Diao, K., Wang, Y., Chen, H., Zhao, Z., et al. (2023b). Deferoxamine attenuates visual impairment in retinal ischemia-reperfusion via inhibiting ferroptosis. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 20145. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-46104-0

Wang, Y., Liu, X., Wang, B., Sun, H., Ren, Y., and Zhang, H. (2024). Compounding engineered mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: a potential rescue strategy for retinal degeneration. Biomed. Pharmacother. 173, 116424. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116424

Xiong, M., Ou, C., Yu, C., Qiu, J., Lu, J., Fu, C., et al. (2023). Qi-Shen-Tang alleviates retinitis pigmentosa by inhibiting ferroptotic features via the NRF2/GPX4 signaling pathway. Heliyon 9 (11), e22443. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22443

Yamada, K., Tazaki, A., Ushio-Watanabe, N., Usui, Y., Takeda, A., Matsunaga, M., et al. (2023). Retinal ferroptosis as a critical mechanism for the induction of retinochoroiditis during ocular toxoplasmosis. Redox Biol. 67, 102890. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2023.102890

Yang, Y., Wang, Y., Deng, Y., Lu, J., Xiao, L., Li, J., et al. (2023). Fructus Lycii and Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge extract attenuate oxidative stress-induced photoreceptor ferroptosis in retinitis pigmentosa. Biomed. and Pharmacother. 167, 115547. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115547

Yao, F., Peng, J., Zhang, E., Ji, D., Gao, Z., Tang, Y., et al. (2023). Pathologically high intraocular pressure disturbs normal iron homeostasis and leads to retinal ganglion cell ferroptosis in glaucoma. Cell Death Differ. 30 (1), 69–81. doi:10.1038/s41418-022-01046-4

Yao, Y., Xu, Y., Liang, J.-J., Zhuang, X., and Ng, T. K. (2022). Longitudinal and simultaneous profiling of 11 modes of cell death in mouse retina post-optic nerve injury. Exp. Eye Res. 222, 109159. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2022.109159

Youale, J., Bigot, K., Kodati, B., Jaworski, T., Fan, Y., Nsiah, N. Y., et al. (2022). Neuroprotective effects of transferrin in experimental glaucoma models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (21), 12753. doi:10.3390/ijms232112753

Zhang, F., Lin, B., Huang, S., Wu, P., Zhou, M., Zhao, J., et al. (2023). Melatonin alleviates retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting p53-mediated ferroptosis. Antioxidants 12 (6), 1173. doi:10.3390/antiox12061173

Zhang, J., Qiu, Q., Wang, H., Chen, C., and Luo, D. (2021). TRIM46 contributes to high glucose-induced ferroptosis and cell growth inhibition in human retinal capillary endothelial cells by facilitating GPX4 ubiquitination. Exp. Cell Res. 407 (2), 112800. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2021.112800

Zhang, J., Wu, C., Gao, L., Du, G., and Qin, X. (2020a). Astragaloside IV derived from Astragalus membranaceus: a research review on the pharmacological effects. Adv. Pharmacol. 87, 89–112. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2019.08.002

Zhang, Y., Zhang, G., Liang, Y., Wang, H., Wang, Q., Zhang, Y., et al. (2020b). Potential mechanisms underlying the hepatic-protective effects of danshensu on iron overload mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 43 (6), 968–975. doi:10.1248/bpb.b19-01084

Zhao, M., and Peng, G. H. (2021). Regulatory mechanisms of retinal photoreceptors development at single cell resolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (16), 8357. doi:10.3390/ijms22168357

Zhao, Y., Li, Q., Jian, W., Han, X., Zhang, Y., Zeng, Y., et al. (2023). Protective benefits of salvianic acid A against retinal iron overload by inhibition of ferroptosis. Biomed. and Pharmacother. 165, 115140. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115140

Glossary

AMD age-related macular degeneration

DR diabetic retinopathy

RP retinitis pigmentosa

ROS reactive oxygen species

RPE retinal pigment epithelial cells

RGC retinal ganglion cells

I/R ischemia-reperfusion

ACSL4 acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4

SD Stargardt disease

atRAL all-transretinal

GSH glutathione

MDA malondialdehyde

pH IOP pathological high intraocular pressure

NMDA N-methyl-D-aspartate

HRCECs human retinal capillary endothelial cells

PM2.5 airborne fine particulate matter

HRMECs human retinal microvascular endothelial cells

OT Ocular toxoplasmosis

CPT1 carnitine palmitoyltransferase I

TCM traditional Chinese medicine

DFO deferoxamine

LDH lactate dehydrogenase

DFP deferiprone

FDA Food and Drug Administration

TF transferrin

Fer-1 ferrostatin-1

atRA all-trans-retinoic acid

AS-IV astragaloside IV

LOX lipoxygenase

RIPK receptor-interacting protein kinase

ATC Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

Keywords: ferroptosis, retinal diseases, regulatory mechanism, ferroptosis targeting agents, ferroptosis inhibitors

Citation: Hao X-D, Xu W-H, Zhang X and Xue J (2024) Targeting ferroptosis: a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of retinal diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 15:1489877. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1489877

Received: 02 September 2024; Accepted: 21 October 2024;

Published: 30 October 2024.

Edited by:

Ana Raquel Santiago, University of Coimbra, PortugalReviewed by:

Aarti Sharma, Mayo Clinic Arizona, United StatesPere Garriga, Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya, Spain

Copyright © 2024 Hao, Xu, Zhang and Xue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiao-Dan Hao, aGFveGlhb2RhbjE5ODdAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Junqiang Xue, eHVlanFAcWR1LmVkdS5jbg==

Xiao-Dan Hao

Xiao-Dan Hao Wen-Hua Xu

Wen-Hua Xu Xiaoping Zhang4

Xiaoping Zhang4