- 1Department of Hematology, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China

- 2Department of Hematology, Yanyuan People’s Hospital, Liangshan, China

All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) plays a role in tissue development, neural function, reproduction, vision, cell growth and differentiation, tumor immunity, and apoptosis. ATRA can act by inducing autophagic signaling, angiogenesis, cell differentiation, apoptosis, and immune function. In the blood system ATRA was first used with great success in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), where ATRA differentiated leukemia cells into mature granulocytes. ATRA can play a role not only in APL, but may also play a role in other hematologic diseases such as immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), non-APL acute myeloid leukemia (AML), aplastic anemia (AA), multiple myeloma (MM), etc., especially by regulating mesenchymal stem cells and regulatory T cells for the treatment of ITP. ATRA can also increase the expression of CD38 expressed by tumor cells, thus improving the efficacy of daratumumab and CD38-CART. In this review, we focus on the mechanism of action of ATRA, its role in various hematologic diseases, drug combinations, and ongoing clinical trials.

1 Introduction

Retinoids are a group of vitamin A metabolites that include retinal, β-carotene, retinol, isotretinoin, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), 9-cis retinoic acid, and 13-cis retinoic acid (Ni et al., 2019; Szymański et al., 2020). ATRA plays a role in tissue development, neurological function, immune function, reproduction, vision, cell growth and differentiation, tumor immunity, apoptosis (Niapour et al., 2015; Busada and Geyer, 2016; Hao et al., 2021; Isla-Magrané et al., 2022). Mammals cannot synthesize vitamin A on their own and get it mainly from fruits, vegetables, and animal food sources (eggs and liver). Vitamin A is hydrolyzed to retinol by retinyl ester hydrolase (REH) in the intestines, and retinol is oxidized to all-trans retinaldehyde by retinol dehydrogenase in extrahepatic cells, which is then converted to ATRA by retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RDH) (Kedishvili, 2013; Ni et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2021). Vitamin A and its synthetic analogs regulate epidermal keratinization, differentiation, maturation, and proliferation. Retinoids are widely used in cutaneous oncology for therapeutic and chemo-prevention (non-melanoma skin cancer, primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) and for the treatment of inflammatory skin disorders (acne vulgaris, rosacea, melasma) and hyperproliferative disorders (ichtyosis, psoriasis) (Cosio et al., 2021). Retinoids are also used in the treatment of photodamaged skin, where primarily ATRA ameliorates UV-induced skin damage (Cosio et al., 2021). Subsequently, ATRA has also been used in the treatment of central nervous system disorders (depression), allergic disorders (asthma), metabolic disorders (atherosclerosis), infectious disorders (invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and bacterial infections), tumor immunity and other diseases (Sakamoto et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2020; Campione et al., 2021; Kalisz et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2022). In solid tumors, ATRA promotes programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression to modulate immunosurveillance in gastric cancer (GC), ATRA treats breast cancer by reversing the mesenchymal transcription programs, and disruption of ATRA signaling plays a role in driving aberrant behavior in cancer stem cells (Bobal et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2022; Brown, 2023). ATRA is not new to hematologists. It is used in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) and was the first cell differentiation agent to be used for clinical approval (Wang and Chen, 2000). It is well known that APL used to be an acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a great risk of bleeding and a high mortality rate, and that APL is caused by a balanced translocation t (15; 17) (q22; q12-21), that leads to a fusion of the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene with the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) gene, and that the PML-RARα fusion oncoprotein induces leukemia by blocking normal myeloid cell differentiation (Yilmaz et al., 2021). The combination of ATRA and arsenic trioxide has changed the treatment strategy for APL, making it an acute leukemia that can be cured without chemotherapy regimens (Wang HY. et al., 2022; Kutny et al., 2022).

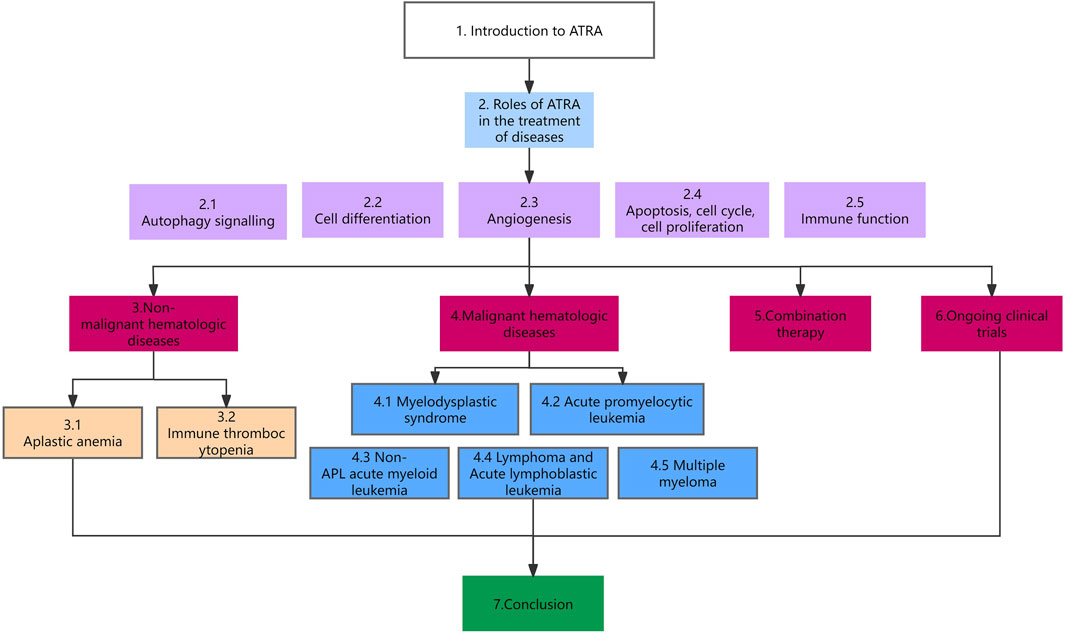

As the study of ATRA has intensified, researchers have found it to be useful in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), aplastic anemia (AA), non-APL AML, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and it has been used as a new second-line regimen in a number of diseases. This article provides an overview of the role and mechanism of action of ATRA in hematologic diseases. The organization of this paper is shown in Figure 1.

2 Roles of ATRA in the treatment of diseases

2.1 Autophagy signalling

Autophagy is a critical homeostatic pathway that promotes degradation and recycling of cellular material (Klionsky et al., 2021). Currently, it is widely accepted that lack of autophagy promotes early tumor development due to its tumor suppressor role in normal cells (Debnath et al., 2023). Autophagy can also contribute to the development of some tumors in some cases. Rat sarcoma (RAS) activation promotes tumor proliferation and drives tumor development, but this can lead to an increase in the tumor’s demand for cellular energy metabolism and anabolic precursors. Autophagy promotes tumor development by alleviating the limited supply of external nutrients through self-digestion (Debnath et al., 2023). The PML-RARα gene inhibits PU-1-dependent transcriptional activation of several genes, including autophagy-related genes, in APL cells (Brigger et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2018). APL cells have low levels of autophagy gene expression and reduced autophagic activity. ATRA induces autophagy via the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway (mTOR), and autophagic degradation is significant for both basal turnover and therapy-induced proteolysis of PML/RARα (Isakson et al., 2010; Moosavi and Djavaheri-Mergny, 2019). The combination of ATRA and valproic acid (VPA) induces the development of autophagy in ATRA-resistant AML (Benjamin et al., 2022). ATRA-mediated crosstalk between hepatic stellate cells and Kupffer cells promotes the NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) activation, inhibits autophagy, and aggravates acute liver injury (Yu et al., 2022). In breast cancer cells, ATRA induces the onset of autophagy mediated by RARα (Brigger et al., 2015). ATRA-mediated upregulation of miR-30a sensitizes GC cells to cisplatin by inhibiting autophagy (Abbasi et al., 2022). In bacterial infections, ATRA also promotes autophagy, thereby reducing the bacterial burden in human macrophages (Coleman et al., 2018). ATRA works by promoting autophagy in a variety of diseases, including acute leukemia, breast cancer, and bacterial infections.

2.2 Cell differentiation

PML-RARα fusion gene is the major genetic alteration in APL. PML acts as a tumor suppressor protein that accumulates in the nucleosome to induce apoptosis, whereas RARα is mainly involved in cell differentiation and renewal, and the formation of the PML-RARα fusion gene impairs the functions of PML and RARα, leading to tumor formation (di Masi et al., 2015). Physiological concentrations of ATRA (up to 90 nmol/L) bound to RARα failed to release the co-repressor of the PML-RARα multimer, and differentiated genes could not be transcribed (Borges et al., 2021). However, binding of pharmacological concentration of ATRA (around 1umol/L) to RARα, RARα transcription restarted to proceed normally, PML-RARα protein was degraded, and APL cells differentiated into polymorphonuclear granulocytes through the RAF-1/MEK/ERk signaling pathway, which reversed the malignant phenotype of APL, and the reduction in the concentration of PML protein restored apoptosis of APL cells (Nervi et al., 1998; Borges et al., 2021). Blocking RAF-1 activation reduces MEK/ERk activation and ATRA-induced cell differentiation, and ATRA plays a role in inducing APL cell differentiation by increasing the protein levels of C/EBPβ, C/EBPε, and PU.1 through the MEK/ERk pathway (Weng et al., 2016). In isocitrate dehydrogenase-2 (IDH2) mutated AML, ATRA in combination with the IDH2 inhibitor enasidenib induces cell differentiation, an effect associated with the RAF-1/MEK/ERK pathway and the induction of autophagy. Enasidenib in combination with ATRA may further improve or increase the response rate in patients with IDH2-mutated AML (Kim et al., 2020). Dasatinib in combination with ATRA could exert a synergistic effect in ATRA-resistant APL cells, and the combination of the two drugs activated the RAF-1/MEK/ERK pathway, and augmented the upregulation of ATRA-promoted PU.1, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPε protein levels, which facilitated cell differentiation (Ding et al., 2018). ATRA plays a major role in inducing cell differentiation through the RAF-1/MEK/ERK signaling pathway and activation of PU.1, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPε proteins, and the addition of dasatinib may play a synergistic role when ATRA is resistant.

2.3 Angiogenesis

In vitro experiments revealed a decrease in the expression of both vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGFR-2 when ATRA and melatonin were co-treated with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and NB4 (APL cell line), which suggests that the combination of ATRA and melatonin has an anti-angiogenic effect (Amirzargar et al., 2023). In breast cancer, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) are critical for resistance to antiangiogenic therapies, and in vivo experiments have found that ATRA treatment reduces MDSC and improves the efficacy of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 antibodies alone or in combination with chemotherapy (Bauer et al., 2018). In gliomas, in vitro experiments revealed a significant increase in the expression of VEGF and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) was observed in the low-concentration group ATRA (5 and 10 μmol/L) and a significant decrease in the expression of VEGF and HIF-1α was observed in the high-concentration ATRA group (40 μmol/L), and in vivo experiments revealed that high concentration of ATRA reduced microvessel density (MVD) in gliomas compared to the control group (Liang et al., 2014). In vitro experiments in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, ATRA inhibited angiogenesis by decreasing the protein levels of angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2, and the receptor Tie-2 (Li et al., 2017). In hepatocellular carcinoma, MDSC are key drivers in maintaining an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, and in vivo experiments have revealed that ATRA induces differentiation of MDSC into mature myeloid cells, inhibits angiogenic markers, and ATRA moves towards an anti-tumor phenotype by altering the relative ratio between pro- and anti-tumor immune cells (Li X. et al., 2023). Vessel formation and in vivo wound healing were significantly enhanced in ATRA-treated mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (Pourjafar et al., 2017). Therapeutic doses of ATRA inhibit angiogenesis most of the time, but may promote angiogenesis at low concentrations.

2.4 Apoptosis, cell cycle, cell proliferation

ATRA increases the apoptotic effect of the apoptosis inducer ABT-737 (a bcl-2 selective inhibitor) on AML (Buschner et al., 2021). ATRA treatment of myeloid leukemia cell line K562 resulted in a significant increase in apoptosis, cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase, and a decrease in cell proliferation, which was achieved by up-regulating the increased expression of homeobox A5 (HOXA5) (Liu et al., 2016). ATRA induced cell cycle arrest, increased apoptosis, and decreased cell proliferation in APL cell line NB4, and this effect was exerted by inducing retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I) expression and further through the AKT-FOXO3A signaling pathway (Chen et al., 2017). ATRA treatment induces a persistent inhibition of B cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) in non-APL AML cells, first upregulating and then decreasing myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL-1). Activation of the MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways by ATRA leads to activation of p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (90RSK) and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β), which increases MCL-1 levels. Sorafenib reverses the activation of p90RSK and inactivation of GSK3β, thereby blocking the increase in MCL-1 and maintaining the sustained inhibition of BCL-2, ultimately increasing apoptosis in non-APL AML (Wang et al., 2016). ATRA can also induce increased apoptosis in glioma cells in vitro (Wu et al., 2020). The combination of ATRA with other drugs to increase apoptosis is a future research direction.

2.5 Immune function

As we have mentioned before, ATRA in hepatocellular carcinoma reduces MDSC infiltrated in the tumor, increases the infiltration of cytotoxic T-cells, and moves the tumor microenvironment toward an anti-tumor phenotype (Li X. et al., 2023). ATRA enhances the expression of B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) on MM cells, thereby improving the efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy (García-Guerrero et al., 2023). Also, ATRA upregulates the expression of CD38 in MM cells, and this upregulation is dependent on the t (4; 14) translocation. t (4; 14) translocation-induced nuclear receptor-binding SET domain-containing 2 (NSD2) is positively correlated with the ATRA-induced CD38 expression level, and ATRA enhances the efficacy of anti-CD38 CAR T cells against NSD2-high MM cells (Peng et al., 2023). Guarrera L et al. (Guarrera et al., 2023) performed RNA sequence studies on 13 GC cell lines, for which ATRA had an antiproliferative effect, and constructed a model consisting of 42 genes whose expression was correlated with ATRA sensitivity, and they used these data to analyze GC RNA sequences in the in the Cancer Genome Atlas/Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (TCGA/CCLE) database. They found that 45% of TCGA GCs were sensitive to ATRA, which had a significant immunomodulatory effect that was controlled by upregulation of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1). ATRA and immune checkpoint inhibitors are a reasonable combination for the treatment of GC. However, a study by Ma ZL et al. (Ma et al., 2022) found that ATRA antagonized the function of PD-L1 antibody in GC, and ATRA induced the expression of PD-L1 in GC, which made GC cells highly resistant to killing by activated T cells. ATRA can greatly weaken the immunosuppressive effects of infiltrating MDSC and also activate the antitumor effects of CD8+ T cells, and the combination of ATRA with immune checkpoint inhibitors, tumor vaccines, and chemotherapy has been widely studied in a variety of tumors (Bi et al., 2023). ATRA not only plays a crucial role in inducing intestinal tropism of lymphocytes and regulating T helper cell differentiation, but is also an important regulator of innate immune cells such as tolerogenic dendritic cells (DCs) and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) (Czarnewski et al., 2017). The poor aqueous solubility and rapid metabolism of ATRA have limited its application as an immunomodulator for anticancer immunotherapy. Liposomal ATRA (L-ATRA) is a drug with release persistence, and actively loaded L-ATRA achieves stable encapsulation and controlled release and accumulation of the drug in tumor tissues; they promote the maturation of MDSCs into DCs and the immune response against cancer cells. L-ATRA can prevent tumor growth when used as monotherapy, and its anticancer activity is higher when L-ATRA is combined with checkpoint inhibitors (Zheng et al., 2022). The modulation of tumor immunity by ATRA and the combination of ATRA with immunosuppressive agents deserve more attention.

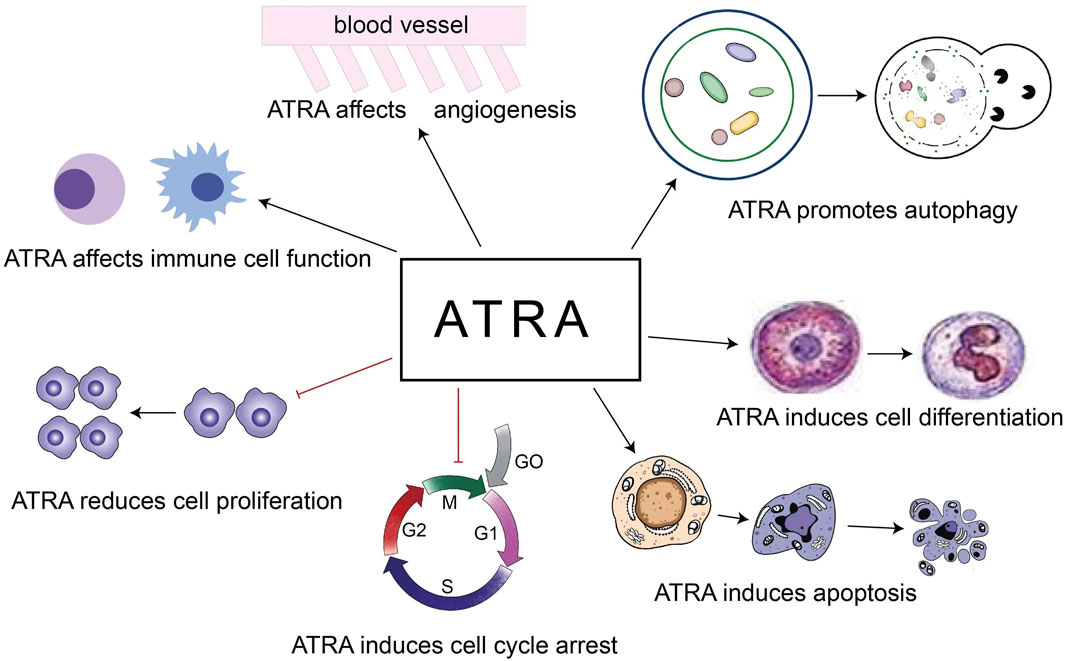

The role of ATRA in the treatment of diseases is based on the above 5 points (Figure 2). Our review focuses on the role of ATRA in the treatment of hematologic diseases, especially the new applications in the last 5 years, and first we look at the role of ATRA in non-malignant hematologic diseases.

3 Non-malignant hematologic diseases

3.1 Aplastic anemia

Aplastic anemia (AA) is a bone marrow failure syndrome that manifests itself as a decrease in total blood count. AA is an immune-mediated disease caused primarily by abnormally active T-cell function that attacks hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Symptoms in most patients with AA improve with the use of anti-thymocyte globulin and cyclosporine to inhibit T-cell function (Young, 2018). The balance between T helper (Th) 1 cells and Th2 cells is important for a normal immune response, and the two work together to maintain immune homeostasis. AA is characterized by an overreaction of Th1 cells and overproduction of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and a decrease in regulatory T cells (Tregs) (Tang et al., 2020). ATRA maintains the balance between T cell subsets and exhibits strong immunomodulatory capacity (Brown et al., 2015; Erkelens and Mebius, 2017). In the model of AA treated with ATRA, ATRA inhibited the proliferation, activation and effector functions of T cells and inhibited the Fas/FasL pathway, caused Th1 cells to develop into Th2 cells by targeting the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) pathway, promoted Th2 cells by upregulating JunB, and ultimately rebalance T cell subsets (Tang et al., 2020). ATRA also inhibits the differentiation of Th17 cells, promotes the development of Tregs, and reduces abnormally activated T cells in the bone marrow microenvironment. ATRA ameliorates bome marrow (BM) dysplasia and pancytopenia in AA mice, and ATRA is a potent agent for improving the therapeutic outcome of AA (Tang et al., 2020).

3.2 Immune thrombocytopenia

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an autoimmune disease in which DCs play a crucial role in the destruction of self-tolerance, and MSCs promote the development of regulatory DCs (regDCs) (Xu et al., 2017). MSCs become senescent and apoptotic in ITP, with a reduced immunosuppressive effect on T cells and B cells. The impaired ability of MSCs in ITP patients to induce CD34+-regDCs is associated with the Notch-1/Jagged-1 signaling pathway. ATRA partially corrects the impairment of MSCs in ITP patients and partially restores the ability of MSCs in ITP patients and healthy controls to induce CD34+-derived regDCs, which is therapeutic for ITP (Xu et al., 2017). The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is involved in the process of MSCs deficiency. MiR-98-5p can act by targeting insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1), and the subsequent downregulation of insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF-2) inhibits the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, and miR-98-5p can also upregulate the expression of p53. ATRA could protect MSCs and reduce apoptosis of MSCs by downregulating miR-98-5p (Wang et al., 2020). Macrophages differentiate into either a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype or an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype in response to different environmental stimuli. ITP patients have more polarized M1 macrophages in the spleen and impaired immune function. High-dose dexamethasone or ATRA can correct this imbalance by decreasing the expression of M1 markers and increasing the expression of M2 markers, and ATRA modulation of macrophages can shift the T-cell cytokine profile toward Th2 (Feng Q. et al., 2017).

The previous paragraph mainly describes the mechanism of action of ATRA in the treatment of ITP, and below we look at the data from the relevant clinical trials. Dai L et al. (Dai et al., 2016) treated 35 patients with relapsed refractory ITP with ATRA (10 mg tid). Complete and overall responses were observed in 10 (28.6%) and 19 (54.3%) patients, and, treatment with ATRA significantly increased the proportion of Treg cells, IL-10 levels, and forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) expression (all three of which were significantly decreased in ITP patients). The study by Feng FE et al. (Feng FE. et al., 2017) randomly assigned ITP patients in a 1:1 ratio to receive either oral ATRA (10 mg bid) + oral danazol (200 mg bid) or oral danazol monotherapy (200 mg bid) for 16 weeks 45 patients were enrolled in the ATRA + danazol group, and 48 in the danazol group. 28 patients (62%) treated with ATRA + danazol achieved a sustained response compared with 12 patients (25%) in the danazol monotherapy group, a statistically significant difference between the two groups. Wu YJ et al. (Wu et al., 2022) randomized ITP patients in a 2:1 ratio, with 112 patients receiving low-dose rituximab (LD-RTX) (100 mg qw for a total of 6 weeks) + ATRA (20 mg/m2 for 12 weeks), and 56 receiving LD-RTX monotherapy; there was an overall response of 80% in the LD-RTX + ATRA group compared to 59% in the LD-RTX 59% in the monotherapy group. ATRA significantly improves initial and long-term responses in patients with ITP and is associated with reduced rates of relapse and salvage therapy, with the main adverse effects being dry skin, dizziness, headache, and acne-like rashes (Yang et al., 2023). ATRA has provided a new boon in the treatment of ITP patients.

4 Malignant hematologic diseases

4.1 Myelodysplastic syndrome

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a heterogeneous disorder characterized by hypoplasia, disturbed differentiation of hematopoietic cells, and increased apoptosis of diseased cells leading to a decrease in one or more lineages, and patients with high-risk MDS (HR-MDS) are predisposed to progression to AML (Trivedi et al., 2021). Decitabine (DAC) is one of the main drugs used in the treatment of HR-MDS, and DAC alone may be resistant by a mechanism that induces NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) activation and a downstream antioxidant response that inhibits reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, leading to drug resistance. The combination of DAC + ATRA decreased the viability of MDS cells, delayed the progression of tumor cells, and prolonged the survival time of mice, and ATRA increased the efficacy of DAC by blocking Nrf2 activation through activation of the RARα-Nrf2 complex, which led to ROS accumulation and ROS-dependent cytotoxicity (Wang et al., 2023). USO1 is a vesicular transporter involved in endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport of proteins. USO1 is aberrantly activated in MDS in vivo and in vitro, and silencing of USO1 promotes myeloid differentiation and inhibits proliferation of MDS cells. USO1 exerts its oncogenic effects by inactivating Raf/ERK signaling (Li et al., 2021). 4-Amino-2-Trifluoromethyl-Phenyl Retinate (ATPR) is a ATRA derivative, and ATPR can induce MDS remission in vitro by decreasing USO1 and modifying Raf/ERK signaling (Li et al., 2021). ATPR also increases apoptosis in MDS cells via p53, and this apoptosis is interdependent with activation of the BNIP3 gene (Du et al., 2018). ATRA or ATPR has a pro-apoptotic effect on MDS cells and ATRA overcomes DAC resistance, next we look at the results of clinical trials of ATRA for MDS.

Low-dose cytarabine or hydroxyurea in combination with or without ATRA in elderly patients with MDS, low-dose cytarabine improved the remission rate of MDS, but there was no better efficacy in combination with ATRA (Burnett et al., 2007). VPA monotherapy for MDS resulted in a response in 44% (8) of patients, including 1 partial remission, and 4 of 5 relapsed patients were treated with VPA + ATRA, with 2 responding again; VPA + ATRA for MDS may be efficacious (Kuendgen et al., 2004). VPA + ATRA treatment of low-risk MDS (LR-MDS) patients resulted in significant freedom from platelet transfusions lasting several months in approximately 30% of patients, reducing the burden of palliative care and improving quality of life (Pilatrino et al., 2005). VPA + ATRA treatment of patients with MDS resulted in improvement in hematologic status in only 18 (24%) of 75, with a median duration of response of 4 months (Kuendgen et al., 2005). Addition of demethylating drugs improves the response rate of VPA + ATRA for MDS. Soriano AO’s study of AML or HR-MDS treated with azacitidine (AZA) + VPA + ATRA had an overall response rate of 42% in 53 patients, 52% in previously untreated elderly patients, and a median duration of remission of 26 weeks (Soriano et al., 2007). Zhang W et al. (Zhang et al., 2006)treated 63 patients with primary refractory anemia (RA) with ATRA + androgens + calcitriol, and 68.3% (43) of the patients showed an improvement in their hematological status, with overall survival rates of 68.72% and 53.18% at 3 and 5 years, respectively. In 31 patients (13 AML, 18 MDS) with myeloid tumors unsuitable for intense chemotherapy treated with low-dose DAC + ATRA, complete remission was achieved in 7 patients (22.6%) and partial remission in 4 patients (12.9%), resulting in an overall remission rate of 58.1%, a median overall survival of 11.0 months, and a 1-year OS rate of 41.9% and a 2-year OS rate of 26.6% (Wu et al., 2016). ATRA + erythropoietin (EPO) treated 27 patients with low- or intermediate-risk MDS; 13 patients (48%) experienced a clinically significant erythrocyte response with a rise in hemoglobin level of at least 1 g/dL or a reduction in transfusion requirements, 5 of 12 neutropenic patients had a neutrophilic response, 6 of 9 thrombocytopenic patients had platelet responses, and three patients had a whole blood cell response; all patients had tolerable side effects (Stasi et al., 2002). Another clinical trial found that EPO + ATRA could be used to treat patients with MDS anemia in whom erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) alone were ineffective, but not in patients with high levels of endogenous EPO, and it did not improve neutropenia or thrombocytopenia (Itzykson et al., 2009).

Clinical trials of ATRA for the treatment of MDS were carried out in large numbers 20 years ago, including ATRA combined with VPA, EPO, androgens, cytarabine, and hydroxyurea, etc. The efficacy of ATRA combined with EPO or androgens in the treatment of RA is worthy of affirmation, but the treatment of HR-MDS did not obtain too good clinical efficacy, and the subsequent application in the clinic is also less. However, ATRA overcoming the resistance of DAC opens a new window for ATRA treatment of MDS, and the efficacy of ATRA combined with demethylating drugs in the treatment of MDS deserves further study.

4.2 Acute promyelocytic leukemia

APL accounts for approximately 10%–15% of all AML and is characterized by leukocyte abnormalities, anemia, low platelets, coagulation abnormalities, and severe bleeding, with a major chromosomal abnormality of t (15; 17) (q22; q12-21), which produces the PML-RARα fusion gene (Yilmaz et al., 2021). In the 1980s, ATRA was used to treat APL, and all 24 patients achieved complete remission, but the duration of complete remission with ATRA monotherapy for APL was short (Huang et al., 1988). After the status of ATRα monotherapy in APL treatment was established, ATRA in combination with chemotherapy for APL became the mainstream regimen, and ATRA in combination with chemotherapy reduces the relapse rate of patients, and patients on maintenance therapy with ATRA achieve significantly better survival (Fenaux et al., 1999). Arsenic trioxide (ATO, As2O3), a chemical derived from the ancient Chinese poison arsenic, was identified in the 1990s for the treatment of APL. High concentrations of ATO induced apoptosis in APL cells, while low concentrations induced differentiation, and ATO induced apoptosis in NB4 cells through the downregulation of Bcl-2 expression and regulation of the PML-RAR alpha/PML protein (Chen et al., 1996; Zhao et al., 2001). A clinical trial divided APL patients into ATRA + ATO versus ATRA + chemotherapy groups; ATRA + ATO enrolled 77 patients, all of whom achieved complete remission, and ATRA + ATO enrolled 79, 95% of whom achieved complete remission. With a median follow-up of 34.4 months, the 2-year event-free survival rate was 97% in the ATRA + ATO group and 86% in the ATRA + chemotherapy group. ATRA + ATO was associated with less hematologic toxicity and fewer infections than ATRA + chemotherapy (Lo-Coco et al., 2013). ATRA + ATO is a viable treatment with a high cure rate, low recurrence rate, no difference in survival, and a low incidence of liver toxicity compared to ATRA + idarubicin (Burnett et al., 2015). Kutny MA used an ATRA + ATO-based regimen to treat pediatric APL patients. The 2-year event-free survivalrate was 98.0% and the overall survival rate was 99.0% in patients with standard-risk APL, and 96.4% and 100% in patients with high-risk APL; the regimen was associated with a shorter duration of treatment, fewer days of hospitalization, and less exposure to anthracyclines and intrathecal chemotherapy (Kutny et al., 2022). Abaza Y et al. (Abaza et al., 2017) treated APL with ATRA + ATO and combined gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) in high-risk patients and in low-risk patients who developed leukocytosis during induction. A total of 187 patients were treated, including 54 high-risk and 133 low-risk patients. The complete remission rate was 96%, the mortality rate on induction therapy was 4%, and there were only 7 relapses. There is no doubt that ATRA + ATO for APL is one of the most successful protocols studied in recent years, bringing an AL with severe bleeding and high mortality to a curable state.

4.3 Non-APL acute myeloid leukemia

ATRA has significantly improved the prognosis of APL patients, and its study in non-APL AML is so extensive that scientists are eager to find new breakthroughs. But ATRA alone does not work well, and more research is focusing on combinations. An inhibitor of MEK, trametinib, in combination with ATRA restored the sensitivity of ATRA-resistant AML cell lines to ATRA by enhancing the protein levels of STAT3 and phosphorylation of Akt or JNK, and STAT3, PI3K, and JNK inhibitors all inhibited trametinib + ATRA induced cell differentiation in AML cell lines (Lu et al., 2021). ATRA inhibits translation and protein synthesis in AML cells, and the genes regulated by ATRA are mainly concentrated in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, and ATRA + PI3K/AKT inhibitor induces a large number of apoptotic cells and greatly inhibits cloning of AML cells (Wang K. et al., 2022). ATRA treatment of differentiation-responsive AML cells induces persistent inhibition of BCL-2, while first upregulating and then decreasing the level of MCL-1. ATRA activates p90RSK and inactivates GSK3β, and increases the translation and stability of MCL-1 to raise its level. sorafenib reverses the activation of p90RSK and the inactivation of GSK3β, blocks the increase of MCL-1, and maintains the decrease of BCL-2 level, thus enhancing apoptosis in non-APL AML cell lines (Wang et al., 2016). Low dose midostaurin (0.25–0.5 μM) + ATRA induced cell differentiation, whereas high dose midostaurin (0.25–0.5 μM) + ATRA led to apoptosis in FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) AML cell line, and apoptosis induced by high dose midostaurin + ATRA was dependent on caspase-3/7. Low dose midostaurin + ATRA inhibited the activation of Akt, leading to dephosphorylation of RAF S259, activation of RAF/MEK/ERK, and upregulation of the protein levels of C/EBPβ, C/EBPε, and PU.1, which resulted in an increase in cell differentiation (Lu et al., 2022). Nucleophosmin-1 (NPM1) mutations in AML not only dislocate NPM1 from the nucleolus but also disorganize the PML nucleosome, ATRA in combination with ATO synergistically induces proteasomal degradation of NPM1 mutations in AML cell lines or primary samples leading to differentiation and apoptosis, and downregulation of the NPM1 mutant by ATRA + ATO also enhances the therapeutic response of AML cells to doxorubicin (El Hajj et al., 2015; Martelli et al., 2015). Targeted ferroptosis contribute to ATPR-induced AML cell differentiation, ATPR induces ferroptosis in a dose-dependent manner, and ATPR-induced ferroptosis is regulated by autophagy through iron homeostasis, especially Nrf2 (Du et al., 2020). Both cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) depletion and CDK2 pharmacological inhibitors significantly sensitize AML cell lines to ATRA-induced cell differentiation (Shao et al., 2020). It has also been found that HIF2α blockade in cooperation with ATRA triggers AML cell differentiation (Magliulo et al., 2023). One of the causes of resistance to ATRA in non-APL AML is the aberrant acetylation of the acetyltransferase general control non-depressible 5 (GCN5) via histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9ac) residues, and GCN5 also maintains the expression of stemness and leukemia-associated genes (Kahl et al., 2019). Inhibition of GCN5 increases the therapeutic response to ATRA, and concomitant inhibition of the lysine demethylase 1 (LSD1) enhances this response, leading to differentiation of most non-APL AMLs (Kahl et al., 2019). ATRA in combination with tranylcypromine (TCP), which inhibits LSD1, induces AML cell differentiation. A phase I/II clinical trial studied TCP/ATRA for relapsed/refractory AML with an overall response rate of 20%, median survival of 3.3 months, and 1-year survival of 22% in 18 patients, and they observed elevated levels of lysine 4 of histone H3 (H3K4me1) and lysine 4 residue on histone 3 (H3k4me2) in some of the treated patients (Wass et al., 2021). A meta-analysis found that chemotherapy + ATRA did not improve patients’ overall survival compared to chemotherapy alone (Küley-Bagheri et al., 2018). AML patients with adverse genetic features such as complex, monosomal karyotypes and TP53 lesions have a very poor prognosis, and DAC + ATRA has a synergistic antileukemic effect, increasing response rates and prolonging overall survival (Meier et al., 2022). CAR-T therapies are currently less effective in AML, but ATRA increases the expression of CD38 on the cell surface of AML cells, thereby increasing the efficacy of CD38-CAR-T for AML (Yoshida et al., 2016). The use of ATRA as maintenance therapy for AML in children has comparable efficacy to the use of cytarabine (Li J. et al., 2023).

The basic research and clinical trials of ATRA in the treatment of non-APL AML are relatively numerous, and the basic research is mainly oriented to the combination of drugs, which can play a synergistic role in inducing AML cell apoptosis and cell differentiation. The efficacy of previous clinical trials has not been too encouraging, but the efficacy of the combination of new drugs (e.g., CDK2 inhibitors, daratumumab, midostaurin, etc.) and ATRA in the treatment of non-APL AML still deserves to be further investigated.

4.4 Lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia

CD38-CART inhibits the growth of CD38-overexpressing mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM), NK/T-cell lymphoma (NKTCL), multiple myeloma (MM), and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) in vitro, and ATRA enhances a wide range of CD38-low expressing cancer cells’ CD38 expression and increases the therapeutic efficacy of daratumumab (CD38-targeting antibody) and CD38-CART (Wang X. et al., 2022). Primary exudative lymphoma (PEL) is a lymphoma that often expresses CD38, but despite high CD38 expression, daratumumab does not induce complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) in PEL but increases antibody-dependent cell-mediated cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), and ATRA and pomalidomide significantly increase the CD38 levels in low CD38-expressing PEL cell lines, which in turn increases daratumumab-induced ADCC, and daratumumab in combination with ATRA or pomalidomide is a potential therapeutic option for PEL (Shrestha et al., 2023). Stauffer RG used nanodisks to target drug delivery to tumor cells, and they found that the combination of curcumin-nanodisks and ATRA-nanodisks significantly enhanced the bioactivity of these drugs against MCL and follicular lymphoma cells (Stauffer et al., 2015). Many T-ALL cells express CD38 on their surface, and treatment of T-ALL cells with ATRA increases CD38 expression, which further enhances antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) in macrophages and ADCC, especially when using daratumumab-IgA2 (Baumann et al., 2022). ATRA-treated Ink4-Arf deletion (Arf−/−) BCR-ABL ALL cells showed increased apoptosis, fewer S-phase cells, and more G0/G1-phase cells, and ATRA reduced BCR-ABL ALL cell viability by signaling through the retinoid X receptor (Annu et al., 2020).

The primary mechanism of action of ATRA in the treatment of lymphoid system tumors is to increase the expression of CD38 on the surface of tumor cells, thereby increasing the efficacy of daratumumab or CD38-CART.

4.5 Multiple myeloma

A hypersialylated tumor cell surface contributes to aberrant cell migration and drug resistance, and hypersialylation has also been associated with evasion of natural killer (NK) cell-mediated immunosurveillance (Daly et al., 2022). Desialylation with sialylase and sialyltransferase inhibitor (SIA) greatly enhanced NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity against MM cells. MM cells with low CD38 expression elicited potent NK cytotoxic responses after treatment with ATRA, SIA and daratumumab (Daly et al., 2022). ATRA enhances CD38 expression, thereby increasing the efficacy of CD38-CART (Nijhof et al., 2015; Wang X. et al., 2022; Sharma et al., 2024). However, inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC) 6 antagonized the upregulation of CD38 expression by IFN-α and ATRA in MM cells (Bat-Erdene et al., 2019). While ATRA-induced CD38 upregulation on MM target cells can also induce CD38 levels on CD38 wild-type NK cells, ATRA-induced CD38 upregulation in MM may be counteracted by increased NK cell fratricide and impaired NK cell function, thereby reducing the overall efficacy of daratumumab, whereas deleting the CD38 level on NK cells expanded ex vivo using the CRISPR/Cas9 system could mitigate this situation (Naeimi et al., 2020). A clinical trial investigating the efficacy of ATRA + daratumumab in daratumumab-refractory MM found an overall response rate of 5%, with the majority of patients (66%) having stable disease (Frerichs et al., 2021). ATRA temporarily increased CD38 expression on immune cell subsets, but the clinical efficacy of the combination was suboptimal, probably because ATRA also concomitantly increased CD38 expression on NK cells, whereas daratumumab killed CD38-positive NK cells, reducing the daratumumab-mediated ADCC effect and leading to decreased efficacy (Naeimi et al., 2020; Frerichs et al., 2021). ATRA upregulates CD38 in MM cells in a nonlinear manner, and this upregulation is dependent on the t (4; 14) translocation. Whereas t (4; 14) translocation-induced NSD2 was positively correlated with ATRA-induced CD38 expression levels, NSD2 interacted with the ATRA receptor RARα to protect it from degradation (Peng et al., 2023). Knockdown of NSD2 attenuates MM sensitivity to ATRA-induced CD38 upregulation. ATRA enhances the efficacy of CD38-CAR T cells against NSD2-high MM cells both in vitro and in vivo (Peng et al., 2023). ATRA treatment leads to an increase in BCMA transcript and protein expression in MM cell lines and primary MM cells and enhances the efficacy of BCMA-CART, and co-treatment of MM cells with ATRA and the γ-secretase inhibitor, crenigacestat, further increases BCMA expression and enhances the efficacy of BCMA-CART (García-Guerrero et al., 2023). ATRA enhanced the sensitivity of MM cells to carfilzomib-induced cytotoxicity and re-sensitized carfilzomib-resistant MM cells to carfilzomib (Wang Q. et al., 2022). Mechanistically, ATRA mainly activated the retinoic acid receptor (RAR)γ and interferon-β response pathways to upregulate the expression of IRF1, which initiated the transcription of OAS1, which synthesized 2–5A upon binding to carfilzomib-induced double-stranded RNA and led to degradation of the cellular RNA by RNase L and cell death, and the selective RARγ agonist BMS961 could also re-sensitize MM cells to carfilzomib in vitro (Wang Q. et al., 2022).

ATRA alone has no effect on MM cells, and the mechanism of action of ATRA in MM is mainly to increase the expression of CD38 and increase the efficacy of CD38-CART, especially in MM cells with high NSD2 expression. ATRA + daratumumab, however, did not increase efficacy in patients with daratumumab-resistant MM. ATRA also increased BCMA expression, which increased the efficacy of BCMA-CART. ATRA also enhanced the sensitivity of MM cells to carfilzomib-induced cytotoxicity and re-sensitized carfilzomib-resistant MM cells to carfilzomib.

5 Combination therapy

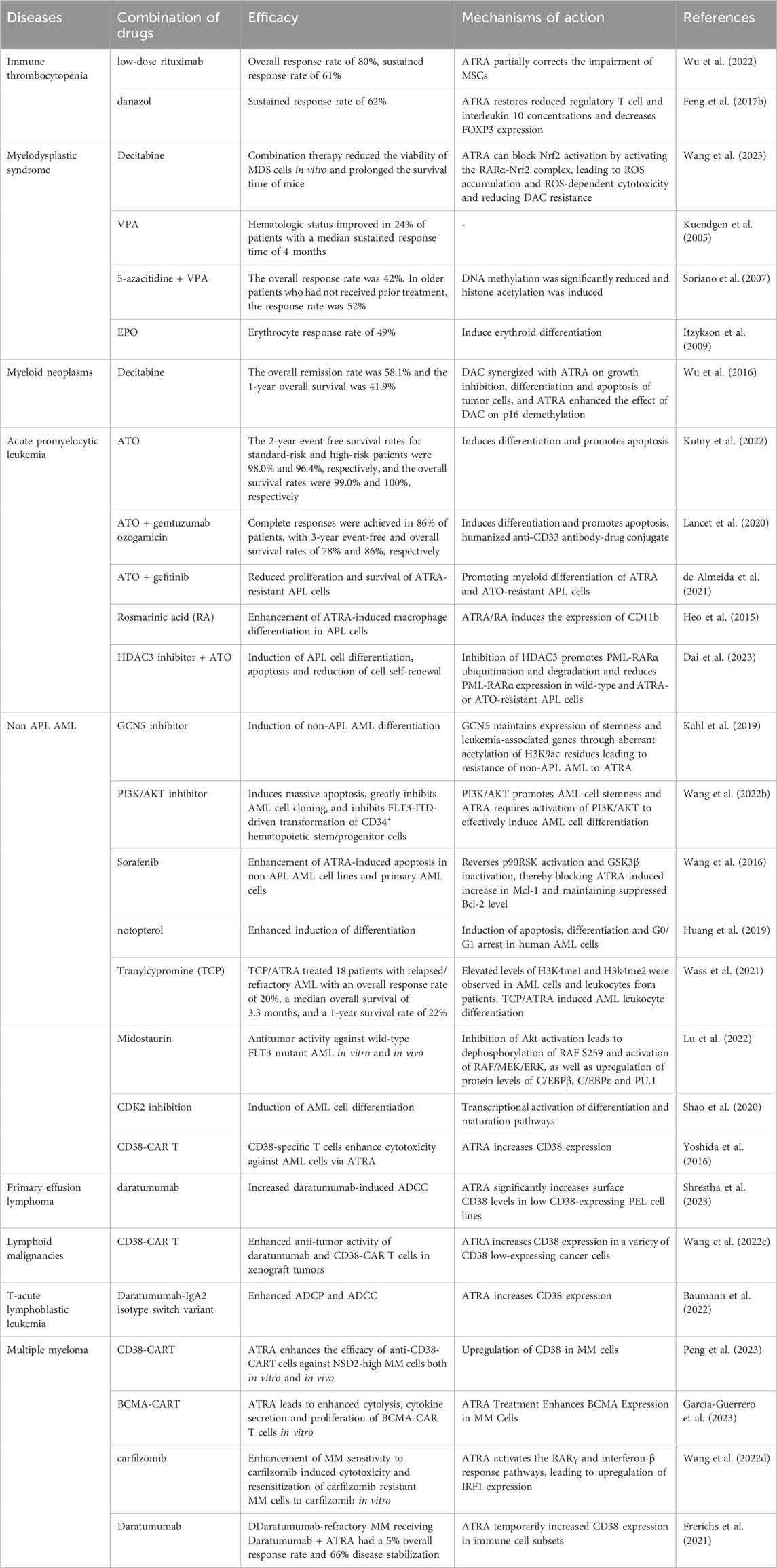

ATRA plays a very important role in the treatment of APL, but the combination with ATO can still further improve the efficacy. The treatment of ATRA in hematologic diseases is mainly based on the use of combination drugs. Here we summarize the efficacy, mechanism of action of ATRA in combination with other drugs in hematologic diseases (Table 1).

6 Ongoing clinical trials

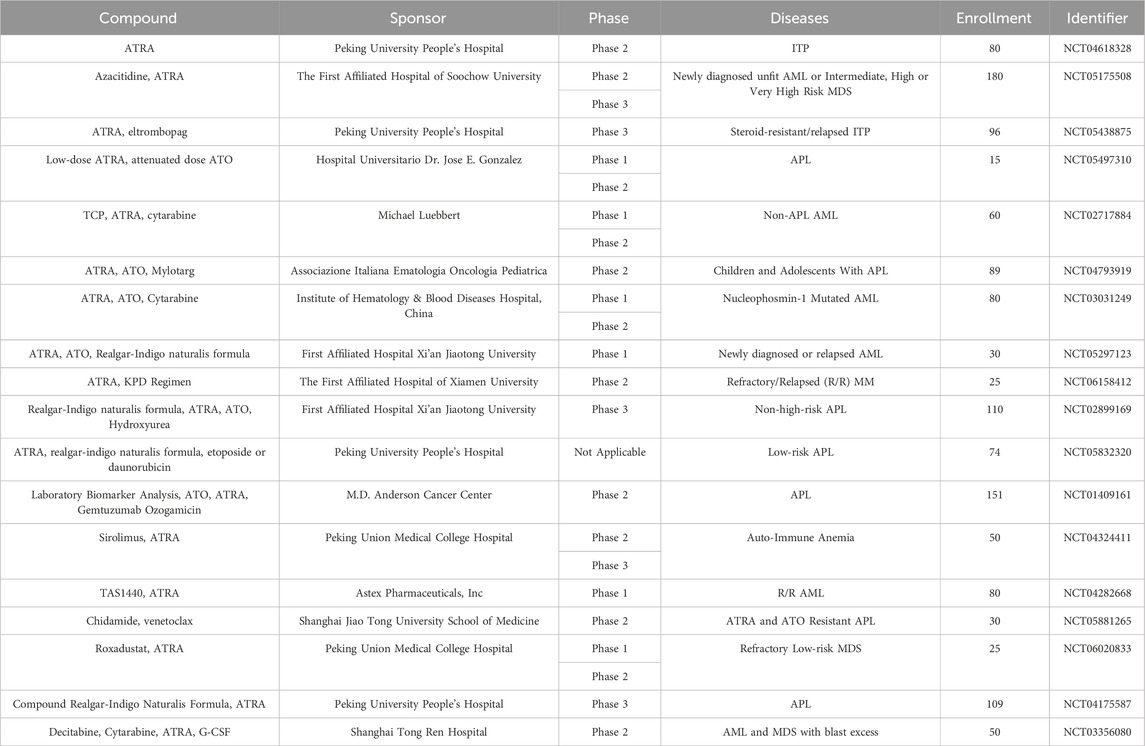

All drugs and therapeutic regimens require clinical trials to evaluate their safety and efficacy before they can be applied to the clinic on a large scale. Previously, we have presented the results of some clinical trials of ATRA in MDS, APL, ITP and MM, some clinical trials showed that ATRA has a good prospect of application, and some clinical trials showed that ATRA does not have better efficacy. Next we summarize the ongoing clinical trials of ATRA in hematologic disorders (Table 2).

Table 2. Ongoing clinical trials of ATRA in hematologic disorders (from www.clinicaltrials.gov, Data obtained on 10 March 2024).

We find that there are still many ongoing clinical studies of ATRA, including lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, skin diseases, and more. In the hematologic system, there are 7 in APL, 4 in non-APL AML, 3 in MDS, 2 in ITP, 1 in auto-immune anemia, and 1 in MM. All of these studies were combined drug treatments.

7 Conclusion

ATRA is an ancient and miraculous drug, which was first used for the treatment of a number of skin diseases, and later applied in the treatment of tumors, central nervous system diseases, metabolic diseases and so on. ATRA acts by inducing autophagy signaling pathway, angiogenesis, cell differentiation, apoptosis, and immune function. In the hematologic system, ATRA was the first cell differentiation drug approved for the treatment of APL, and ATRA has worked wonders to transform APL from a disease with a very high mortality rate to the most efficacious AML. With various studies, ATRA has been gradually applied in the treatment of ITP, AA, MDS, MM, lymphatic system diseases, and non-APL AML. Particularly in ITP, as a disease prone to recurrent relapses, the addition of ATRA can significantly improve initial and long-term responses in relapse-refractory patients and can reduce relapse rates. In MM, MDS and non-APL AML, the effect of ATRA drug therapy seems to be less obvious, but recent studies have found that ATRA can increase the expression of CD38 and BCMA in tumor cells, which improves the efficacy of daratumumab, CD38-CART, and BCMA-CART, which is encouraging news. There are still many ongoing clinical trials of ATRA in hematologic diseases, and it is believed that ATRA will be more widely used in hematologic diseases in the future.

Author contributions

YC: Writing–original draft. XT: Writing–original draft. RL: Writing–original draft. ZZ: Writing–original draft. TM: Funding acquisition, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The present study was supported by grants from Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (2022NSFSC1595).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abaza, Y., Kantarjian, H., Garcia-Manero, G., Estey, E., Borthakur, G., Jabbour, E., et al. (2017). Long-term outcome of acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans-retinoic acid, arsenic trioxide, and gemtuzumab. Blood 129 (10), 1275–1283. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-09-736686

Abbasi, A., Hosseinpourfeizi, M., and Safaralizadeh, R. (2022). All-trans retinoic acid-mediated miR-30a up-regulation suppresses autophagy and sensitizes gastric cancer cells to cisplatin. Life Sci. 307, 120884. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120884

Amirzargar, M. R., Shahriyary, F., Shahidi, M., Kooshari, A., Vafajoo, M., Nekouian, R., et al. (2023). Angiogenesis, coagulation, and fibrinolytic markers in acute promyelocytic leukemia (NB4): an evaluation of melatonin effects. J. pineal Res. 75 (3), e12901. doi:10.1111/jpi.12901

Annu, K., Cline, C., Yasuda, K., Ganguly, S., Pesch, A., Cooper, B., et al. (2020). Role of vitamins A and D in BCR-ABL arf(-/-) acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 2359. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-59101-4

Bat-Erdene, A., Nakamura, S., Oda, A., Iwasa, M., Teramachi, J., Ashtar, M., et al. (2019). Class 1 HDAC and HDAC6 inhibition inversely regulates CD38 induction in myeloma cells via interferon-α and ATRA. Br. J. Haematol. 185 (5), 969–974. doi:10.1111/bjh.15673

Bauer, R., Udonta, F., Wroblewski, M., Ben-Batalla, I., Santos, I. M., Taverna, F., et al. (2018). Blockade of myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion with all-trans retinoic acid increases the efficacy of antiangiogenic therapy. Cancer Res. 78 (12), 3220–3232. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3415

Baumann, N., Arndt, C., Petersen, J., Lustig, M., Rösner, T., Klausz, K., et al. (2022). Myeloid checkpoint blockade improves killing of T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells by an IgA2 variant of daratumumab. Front. Immunol. 13, 949140. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.949140

Benjamin, D. N., O’Donovan, T. R., Laursen, K. B., Orfali, N., Cahill, M. R., Mongan, N. P., et al. (2022). All-trans-retinoic acid combined with valproic acid can promote differentiation in myeloid leukemia cells by an autophagy dependent mechanism. Front. Oncol. 12, 848517. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.848517

Bi, G., Liang, J., Bian, Y., Shan, G., Besskaya, V., Wang, Q., et al. (2023). The immunomodulatory role of all-trans retinoic acid in tumor microenvironment. Clin. Exp. Med. 23 (3), 591–606. doi:10.1007/s10238-022-00860-x

Bobal, P., Lastovickova, M., and Bobalova, J. (2021). The role of ATRA, natural ligand of retinoic acid receptors, on EMT-related proteins in breast cancer: minireview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (24), 13345. doi:10.3390/ijms222413345

Borges, G. S. M., Lima, F. A., Carneiro, G., Goulart, G. A. C., and Ferreira, L. A. M. (2021). All-trans retinoic acid in anticancer therapy: how nanotechnology can enhance its efficacy and resolve its drawbacks. Expert Opin. drug Deliv. 18 (10), 1335–1354. doi:10.1080/17425247.2021.1919619

Brigger, D., Proikas-Cezanne, T., and Tschan, M. P. (2014). WIPI-dependent autophagy during neutrophil differentiation of NB4 acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cell death Dis. 5 (7), e1315. doi:10.1038/cddis.2014.261

Brigger, D., Schläfli, A. M., Garattini, E., and Tschan, M. P. (2015). Activation of RARα induces autophagy in SKBR3 breast cancer cells and depletion of key autophagy genes enhances ATRA toxicity. Cell death Dis. 6 (8), e1861. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.236

Brown, C. C., Esterhazy, D., Sarde, A., London, M., Pullabhatla, V., Osma-Garcia, I., et al. (2015). Retinoic acid is essential for Th1 cell lineage stability and prevents transition to a Th17 cell program. Immunity 42 (3), 499–511. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.003

Brown, G. (2023). Deregulation of all-trans retinoic acid signaling and development in cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (15), 12089. doi:10.3390/ijms241512089

Burnett, A. K., Milligan, D., Prentice, A. G., Goldstone, A. H., McMullin, M. F., Hills, R. K., et al. (2007). A comparison of low-dose cytarabine and hydroxyurea with or without all-trans retinoic acid for acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome in patients not considered fit for intensive treatment. Cancer 109 (6), 1114–1124. doi:10.1002/cncr.22496

Burnett, A. K., Russell, N. H., Hills, R. K., Bowen, D., Kell, J., Knapper, S., et al. (2015). Arsenic trioxide and all-trans retinoic acid treatment for acute promyelocytic leukaemia in all risk groups (AML17): results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16 (13), 1295–1305. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00193-X

Busada, J. T., and Geyer, C. B. (2016). The role of retinoic acid (RA) in spermatogonial differentiation. Biol. reproduction 94 (1), 10. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.115.135145

Buschner, G., Feuerecker, B., Spinner, S., Seidl, C., and Essler, M. (2021). Differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells with ATRA reduces (18)F-FDG uptake and increases sensitivity towards ABT-737-induced apoptosis. Leukemia lymphoma 62 (3), 630–639. doi:10.1080/10428194.2020.1839648

Campione, E., Gaziano, R., Doldo, E., Marino, D., Falconi, M., Iacovelli, F., et al. (2021). Antifungal effect of all-trans retinoic acid against Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro and in a pulmonary aspergillosis in vivo model. Antimicrob. agents Chemother. 65 (3), e01874. doi:10.1128/AAC.01874-20

Chen, G. Q., Zhu, J., Shi, X. G., Ni, J. H., Zhong, H. J., Si, G. Y., et al. (1996). In vitro studies on cellular and molecular mechanisms of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia: as2O3 induces NB4 cell apoptosis with downregulation of Bcl-2 expression and modulation of PML-RAR alpha/PML proteins. Blood 88 (3), 1052–1061. doi:10.1182/blood.v88.3.1052.bloodjournal8831052

Chen, L., Cui, Y. B., Si, Y. L., Su, W. D., Wang, X. C., Pang, H., et al. (2017). Lentivirus-mediated RIG-I knockdown relieves cell proliferation inhibition, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in ATRA-induced NB4 cells via the AKT-FOXO3A signaling pathway in vitro. Mol. Med. Rep. 16 (3), 2556–2562. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.6858

Coleman, M. M., Basdeo, S. A., Coleman, A. M., Cheallaigh, C. N., Peral de Castro, C., McLaughlin, A. M., et al. (2018). All-trans retinoic acid augments autophagy during intracellular bacterial infection. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 59 (5), 548–556. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2017-0382OC

Cosio, T., Di Prete, M., Gaziano, R., Lanna, C., Orlandi, A., Di Francesco, P., et al. (2021). Trifarotene: a current review and perspectives in dermatology. Biomedicines 9 (3), 237. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9030237

Czarnewski, P., Das, S., Parigi, S. M., and Villablanca, E. J. (2017). Retinoic acid and its role in modulating intestinal innate immunity. Nutrients 9 (1), 68. doi:10.3390/nu9010068

Dai, B., Wang, F., Wang, Y., Zhu, J., Li, Y., Zhang, T., et al. (2023). Targeting HDAC3 to overcome the resistance to ATRA or arsenic in acute promyelocytic leukemia through ubiquitination and degradation of PML-RARα. Cell death Differ. 30 (5), 1320–1333. doi:10.1038/s41418-023-01139-8

Dai, L., Zhang, R., Wang, Z., Bai, X., Zhu, M., et al. (2016). Efficacy of immunomodulatory therapy with all-trans retinoid acid in adult patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Thrombosis Res. 140, 73–80. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2016.02.013

Daly, J., Sarkar, S., Natoni, A., Stark, J. C., Riley, N. M., Bertozzi, C. R., et al. (2022). Targeting hypersialylation in multiple myeloma represents a novel approach to enhance NK cell-mediated tumor responses. Blood Adv. 6 (11), 3352–3366. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006805

de Almeida, L. Y., Pereira-Martins, D. A., Weinhäuser, I., Ortiz, C., Cândido, L. A., Lange, A. P., et al. (2021). The combination of gefitinib with ATRA and ATO induces myeloid differentiation in acute promyelocytic leukemia resistant cells. Front. Oncol. 11, 686445. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.686445

Debnath, J., Gammoh, N., and Ryan, K. M. (2023). Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24 (8), 560–575. doi:10.1038/s41580-023-00585-z

di Masi, A., Leboffe, L., De Marinis, E., Pagano, F., Cicconi, L., Rochette-Egly, C., et al. (2015). Retinoic acid receptors: from molecular mechanisms to cancer therapy. Mol. aspects Med. 41, 1–115. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2014.12.003

Ding, M., Weng, X. Q., Sheng, Y., Wu, J., Liang, C., and Cai, X. (2018). Dasatinib synergizes with ATRA to trigger granulocytic differentiation in ATRA resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia cell lines via Lyn inhibition-mediated activation of RAF-1/MEK/ERK. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Industrial Biol. Res. Assoc. 119, 464–478. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2017.10.053

Du, Y., Bao, J., Zhang, M. J., Li, L. L., Xu, X. L., Chen, H., et al. (2020). Targeting ferroptosis contributes to ATPR-induced AML differentiation via ROS-autophagy-lysosomal pathway. Gene 755, 144889. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2020.144889

Du, Y., Li, L. L., Chen, H., Wang, C., Qian, X. W., Feng, Y. B., et al. (2018). A novel all-trans retinoic acid derivative inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of myelodysplastic syndromes cell line SKM-1 cells via up-regulating p53. Int. Immunopharmacol. 65, 561–570. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2018.10.041

El Hajj, H., Dassouki, Z., Berthier, C., Raffoux, E., Ades, L., Legrand, O., et al. (2015). Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide trigger degradation of mutated NPM1, resulting in apoptosis of AML cells. Blood 125 (22), 3447–3454. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-612416

Erkelens, M. N., and Mebius, R. E. (2017). Retinoic acid and immune homeostasis: a balancing act. Trends Immunol. 38 (3), 168–180. doi:10.1016/j.it.2016.12.006

Fenaux, P., Chastang, C., Chevret, S., Sanz, M., Dombret, H., Archimbaud, E., et al. (1999). A randomized comparison of all transretinoic acid (ATRA) followed by chemotherapy and ATRA plus chemotherapy and the role of maintenance therapy in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 94 (4), 1192–1200. doi:10.1182/blood.v94.4.1192

Feng, F. E., Feng, R., Wang, M., Zhang, J. M., Jiang, H., Jiang, Q., et al. (2017b). Oral all-trans retinoic acid plus danazol versus danazol as second-line treatment in adults with primary immune thrombocytopenia: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 4 (10), e487–e496. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30170-9

Feng, Q., Xu, M., Yu, Y. Y., Hou, Y., Mi, X., Sun, Y. X., et al. (2017a). High-dose dexamethasone or all-trans-retinoic acid restores the balance of macrophages towards M2 in immune thrombocytopenia. J. thrombosis haemostasis JTH 15 (9), 1845–1858. doi:10.1111/jth.13767

Frerichs, K. A., Minnema, M. C., Levin, M. D., Broijl, A., Bos, G. M. J., Kersten, M. J., et al. (2021). Efficacy and safety of daratumumab combined with all-trans retinoic acid in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 5 (23), 5128–5139. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005220

García-Guerrero, E., Rodríguez-Lobato, L. G., Sierro-Martínez, B., Danhof, S., Bates, S., Frenz, S., et al. (2023). All-trans retinoic acid works synergistically with the γ-secretase inhibitor crenigacestat to augment BCMA on multiple myeloma and the efficacy of BCMA-CAR T cells. Haematologica 108 (2), 568–580. doi:10.3324/haematol.2022.281339

Guarrera, L., Kurosaki, M., Garattini, S. K., Gianni’, M., Fasola, G., Rossit, L., et al. (2023). Anti-tumor activity of all-trans retinoic acid in gastric-cancer: gene-networks and molecular mechanisms. J. Exp. Clin. cancer Res. CR 42 (1), 298. doi:10.1186/s13046-023-02869-w

Hao, X., Zhong, X., and Sun, X. (2021). The effects of all-trans retinoic acid on immune cells and its formulation design for vaccines. AAPS J. 23 (2), 32. doi:10.1208/s12248-021-00565-1

Heo, S. K., Noh, E. K., Yoon, D. J., Jo, J. C., Koh, S., Baek, J. H., et al. (2015). Rosmarinic acid potentiates ATRA-induced macrophage differentiation in acute promyelocytic leukemia NB4 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 747, 36–44. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.10.064

Hu, P., van Dam, A. M., Wang, Y., Lucassen, P. J., and Zhou, J. N. (2020). Retinoic acid and depressive disorders: evidence and possible neurobiological mechanisms. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 112, 376–391. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.02.013

Huang, M. E., Ye, Y. C., Chen, S. R., Chai, J. R., Lu, J. X., Zhoa, L., et al. (1988). Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 72 (2), 567–572. doi:10.1182/blood.v72.2.567.bloodjournal722567

Huang, Q., Wang, L., Ran, Q., Wang, J., Wang, C., He, H., et al. (2019). Notopterol-induced apoptosis and differentiation in human acute myeloid leukemia HL-60 cells. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 13, 1927–1940. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S189969

Isakson, P., Bjørås, M., Bøe, S. O., and Simonsen, A. (2010). Autophagy contributes to therapy-induced degradation of the PML/RARA oncoprotein. Blood 116 (13), 2324–2331. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-01-261040

Isla-Magrané, H., Zufiaurre-Seijo, M., García-Arumí, J., and Duarri, A. (2022). All-trans retinoic acid modulates pigmentation, neuroretinal maturation, and corneal transparency in human multiocular organoids. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 13 (1), 376. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-03053-1

Itzykson, R., Ayari, S., Vassilief, D., Berger, E., Slama, B., Vey, N., et al. (2009). Is there a role for all-trans retinoic acid in combination with recombinant erythropoetin in myelodysplastic syndromes? A report on 59 cases. Leukemia 23 (4), 673–678. doi:10.1038/leu.2008.362

Jin, J., Britschgi, A., Schläfli, A. M., Humbert, M., Shan-Krauer, D., Batliner, J., et al. (2018). Low autophagy (ATG) gene expression is associated with an immature AML blast cell phenotype and can Be restored during AML differentiation therapy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 1482795. doi:10.1155/2018/1482795

Kahl, M., Brioli, A., Bens, M., Perner, F., Kresinsky, A., Schnetzke, U., et al. (2019). The acetyltransferase GCN5 maintains ATRA-resistance in non-APL AML. Leukemia 33 (11), 2628–2639. doi:10.1038/s41375-019-0581-y

Kalisz, M., Chmielowska, M., Martyńska, L., Domańska, A., Bik, W., and Litwiniuk, A. (2021). All-trans-retinoic acid ameliorates atherosclerosis, promotes perivascular adipose tissue browning, and increases adiponectin production in Apo-E mice. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 4451. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83939-x

Kedishvili, N. Y. (2013). Enzymology of retinoic acid biosynthesis and degradation. J. lipid Res. 54 (7), 1744–1760. doi:10.1194/jlr.R037028

Kim, Y., Jeung, H. K., Cheong, J. W., Song, J., Bae, S. H., Lee, J. I., et al. (2020). All-trans retinoic acid synergizes with enasidenib to induce differentiation of IDH2-mutant acute myeloid leukemia cells. Yonsei Med. J. 61 (9), 762–773. doi:10.3349/ymj.2020.61.9.762

Klionsky, D. J., Petroni, G., Amaravadi, R. K., Baehrecke, E. H., Ballabio, A., Boya, P., et al. (2021). Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO J. 40 (19), e108863. doi:10.15252/embj.2021108863

Kuendgen, A., Knipp, S., Fox, F., Strupp, C., Hildebrandt, B., Steidl, C., et al. (2005). Results of a phase 2 study of valproic acid alone or in combination with all-trans retinoic acid in 75 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 84 (Suppl. 1), 61–66. doi:10.1007/s00277-005-0026-8

Kuendgen, A., Strupp, C., Aivado, M., Bernhardt, A., Hildebrandt, B., Haas, R., et al. (2004). Treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes with valproic acid alone or in combination with all-trans retinoic acid. Blood 104 (5), 1266–1269. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-12-4333

Küley-Bagheri, Y., Kreuzer, K. A., Monsef, I., Lübbert, M., and Skoetz, N. (2018). Effects of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) in addition to chemotherapy for adults with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) (non-acute promyelocytic leukaemia (non-APL)). Cochrane database Syst. Rev. 8 (8), Cd011960. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011960.pub2

Kutny, M. A., Alonzo, T. A., Abla, O., Rajpurkar, M., Gerbing, R. B., Wang, Y. C., et al. (2022). Assessment of arsenic trioxide and all-trans retinoic acid for the treatment of pediatric acute promyelocytic leukemia: a report from the children’s oncology group AAML1331 trial. JAMA Oncol. 8 (1), 79–87. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.5206

Lancet, J. E., Moseley, A. B., Coutre, S. E., DeAngelo, D. J., Othus, M., Tallman, M. S., et al. (2020). A phase 2 study of ATRA, arsenic trioxide, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin in patients with high-risk APL (SWOG 0535). Blood Adv. 4 (8), 1683–1689. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001278

Li, J., Gao, J., Liu, A., Liu, W., Xiong, H., Liang, C., et al. (2023b). Homoharringtonine-based induction regimen improved the remission rate and survival rate in Chinese childhood AML: a report from the CCLG-AML 2015 protocol study. J. Clin. Oncol. official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 41 (31), 4881–4892. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.02836

Li, N., Lu, Y., Li, D., Zheng, X., Lian, J., Li, S., et al. (2017). All-trans retinoic acid suppresses the angiopoietin-Tie2 pathway and inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PloS one 12 (4), e0174555. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174555

Li, S., Deng, G., Su, J., Wang, K., Wang, C., Li, L., et al. (2021). A novel all-trans retinoic acid derivative regulates cell cycle and differentiation of myelodysplastic syndrome cells by USO1. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 906, 174199. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174199

Li, X., Luo, X., Chen, S., Chen, J., Deng, X., Zhong, J., et al. (2023a). All-trans-retinoic acid inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma progression by targeting myeloid-derived suppressor cells and inhibiting angiogenesis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 121, 110413. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110413

Liang, C., Guo, S., and Yang, L. (2014). Effects of all-trans retinoic acid on VEGF and HIF-1α expression in glioma cells under normoxia and hypoxia and its anti-angiogenic effect in an intracerebral glioma model. Mol. Med. Rep. 10 (5), 2713–2719. doi:10.3892/mmr.2014.2543

Liang, C., Qiao, G., Liu, Y., Tian, L., Hui, N., Li, J., et al. (2021). Overview of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) and its analogues: structures, activities, and mechanisms in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 220, 113451. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113451

Liu, W. J., Zhang, T., Guo, Q. L., Liu, C. Y., and Bai, Y. Q. (2016). Effect of ATRA on the expression of HOXA5 gene in K562 cells and its relationship with cell cycle and apoptosis. Mol. Med. Rep. 13 (5), 4221–4228. doi:10.3892/mmr.2016.5086

Lo-Coco, F., Avvisati, G., Vignetti, M., Thiede, C., Orlando, S. M., Iacobelli, S., et al. (2013). Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 369 (2), 111–121. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1300874

Lu, H., Li, Z. Y., Ding, M., Liang, C., Weng, X. Q., Sheng, Y., et al. (2021). Trametinib enhances ATRA-induced differentiation in AML cells. Leukemia lymphoma 62 (14), 3361–3372. doi:10.1080/10428194.2021.1961231

Lu, H., Weng, X. Q., Sheng, Y., Wu, J., Xi, H. M., and Cai, X. (2022). Combination of midostaurin and ATRA exerts dose-dependent dual effects on acute myeloid leukemia cells with wild type FLT3. BMC cancer 22 (1), 749. doi:10.1186/s12885-022-09828-2

Ma, Z. L., Ding, Y. L., Jing, J., Du, L. N., Zhang, X. Y., Liu, H. M., et al. (2022). ATRA promotes PD-L1 expression to control gastric cancer immune surveillance. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 920, 174822. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.174822

Magliulo, D., Simoni, M., Caserta, C., Fracassi, C., Belluschi, S., Giannetti, K., et al. (2023). The transcription factor HIF2α partakes in the differentiation block of acute myeloid leukemia. EMBO Mol. Med. 15 (11), e17810. doi:10.15252/emmm.202317810

Martelli, M. P., Gionfriddo, I., Mezzasoma, F., Milano, F., Pierangeli, S., Mulas, F., et al. (2015). Arsenic trioxide and all-trans retinoic acid target NPM1 mutant oncoprotein levels and induce apoptosis in NPM1-mutated AML cells. Blood 125 (22), 3455–3465. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-11-611459

Meier, R., Greve, G., Zimmer, D., Bresser, H., Berberich, B., Langova, R., et al. (2022). The antileukemic activity of decitabine upon PML/RARA-negative AML blasts is supported by all-trans retinoic acid: in vitro and in vivo evidence for cooperation. Blood cancer J. 12 (8), 122. doi:10.1038/s41408-022-00715-4

Moosavi, M. A., and Djavaheri-Mergny, M. (2019). Autophagy: new insights into mechanisms of action and resistance of treatment in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (14), 3559. doi:10.3390/ijms20143559

Naeimi, K. M., Nagai, Y., Elmas, E., de Souza Fernandes Pereira, M., Ali, S. A., Imus, P. H., et al. (2020). CD38 deletion of human primary NK cells eliminates daratumumab-induced fratricide and boosts their effector activity. Blood 136 (21), 2416–2427. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006200

Nervi, C., Ferrara, F. F., Fanelli, M., Rippo, M. R., Tomassini, B., Ferrucci, P. F., et al. (1998). Caspases mediate retinoic acid-induced degradation of the acute promyelocytic leukemia PML/RARalpha fusion protein. Blood 92 (7), 2244–2251.

Ni, X., Hu, G., and Cai, X. (2019). The success and the challenge of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of cancer. Crit. Rev. food Sci. Nutr. 59 (Suppl. 1), S71–S80. doi:10.1080/10408398.2018.1509201

Niapour, N., Niapour, A., Sheikhkanloui, M. H., Amani, M., Salehi, H., Najafzadeh, N., et al. (2015). All trans retinoic acid modulates peripheral nerve fibroblasts viability and apoptosis. Tissue & Cell 47 (1), 61–65. doi:10.1016/j.tice.2014.11.004

Nijhof, I. S., Groen, R. W., Lokhorst, H. M., van Kessel, B., Bloem, A. C., van Velzen, J., et al. (2015). Upregulation of CD38 expression on multiple myeloma cells by all-trans retinoic acid improves the efficacy of daratumumab. Leukemia 29 (10), 2039–2049. doi:10.1038/leu.2015.123

Peng, Z., Wang, J., Guo, J., Li, X., Wang, S., Xie, Y., et al. (2023). All-trans retinoic acid improves NSD2-mediated RARα phase separation and efficacy of anti-CD38 CAR T-cell therapy in multiple myeloma. J. Immunother. cancer 11 (3), e006325. doi:10.1136/jitc-2022-006325

Pilatrino, C., Cilloni, D., Messa, E., Morotti, A., Giugliano, E., Pautasso, M., et al. (2005). Increase in platelet count in older, poor-risk patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome treated with valproic acid and all-trans retinoic acid. Cancer 104 (1), 101–109. doi:10.1002/cncr.21132

Pourjafar, M., Saidijam, M., Mansouri, K., Ghasemibasir, H., Karimi Dermani, F., and Najafi, R. (2017). All-trans retinoic acid preconditioning enhances proliferation, angiogenesis and migration of mesenchymal stem cell in vitro and enhances wound repair in vivo. Cell Prolif. 50 (1), e12315. doi:10.1111/cpr.12315

Sakamoto, H., Koya, T., Tsukioka, K., Shima, K., Watanabe, S., Kagamu, H., et al. (2015). The effects of all-trans retinoic acid on the induction of oral tolerance in a murine model of bronchial asthma. Int. archives allergy Immunol. 167 (3), 167–176. doi:10.1159/000437326

Shao, X., Xiang, S., Fu, H., Chen, Y., Xu, A., Liu, Y., et al. (2020). CDK2 suppression synergizes with all-trans-retinoic acid to overcome the myeloid differentiation blockade of AML cells. Pharmacol. Res. 151, 104545. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104545

Sharma, A. K., Gupta, K., Mishra, A., Lofland, G., Marsh, I., Kumar, D., et al. (2024). CD38-Specific gallium-68 labeled peptide radiotracer enables pharmacodynamic monitoring in multiple myeloma with PET. Adv. Sci. Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Ger. 11, e2308617. doi:10.1002/advs.202308617

Shrestha, P., Astter, Y., Davis, D. A., Zhou, T., Yuan, C. M., Ramaswami, R., et al. (2023). Daratumumab induces cell-mediated cytotoxicity of primary effusion lymphoma and is active against refractory disease. Oncoimmunology 12 (1), 2163784. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2022.2163784

Soriano, A. O., Yang, H., Faderl, S., Estrov, Z., Giles, F., Ravandi, F., et al. (2007). Safety and clinical activity of the combination of 5-azacytidine, valproic acid, and all-trans retinoic acid in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 110 (7), 2302–2308. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-03-078576

Stasi, R., Brunetti, M., Terzoli, E., and Amadori, S. (2002). Sustained response to recombinant human erythropoietin and intermittent all-trans retinoic acid in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 99 (5), 1578–1584. doi:10.1182/blood.v99.5.1578

Stauffer, R. G., Mohammad, M., and Singh, A. T. (2015). Novel nanoscale delivery particles encapsulated with anticancer drugs, all-trans retinoic acid or curcumin, enhance apoptosis in lymphoma cells predominantly expressing CD20 antigen. Anticancer Res. 35 (12), 6425–6429.

Szymański, Ł., Skopek, R., Palusińska, M., Schenk, T., Stengel, S., Lewicki, S., et al. (2020). Retinoic acid and its derivatives in skin. Cells 9 (12), 2660. doi:10.3390/cells9122660

Tang, D., Liu, S., Sun, H., Qin, X., Zhou, N., Zheng, W., et al. (2020). All-trans-retinoic acid shifts Th1 towards Th2 cell differentiation by targeting NFAT1 signalling to ameliorate immune-mediated aplastic anaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 191 (5), 906–919. doi:10.1111/bjh.16871

Trivedi, G., Inoue, D., and Zhang, L. (2021). Targeting low-risk myelodysplastic syndrome with novel therapeutic strategies. Trends Mol. Med. 27 (10), 990–999. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2021.06.013

Wang, H. Y., Gong, S., Li, G. H., Yao, Y. Z., Zheng, Y. S., Lu, X. H., et al. (2022a). An effective and chemotherapy-free strategy of all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia in all risk groups (APL15 trial). Blood cancer J. 12 (11), 158. doi:10.1038/s41408-022-00753-y

Wang, K., Ou, Z., Deng, G., Li, S., Su, J., Xu, Y., et al. (2022b). The translational landscape revealed the sequential treatment containing ATRA plus PI3K/AKT inhibitors as an efficient strategy for AML therapy. Pharmaceutics 14 (11), 2329. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14112329

Wang, L., Zhang, Q., Ye, L., Ye, X., Yang, W., Zhang, H., et al. (2023). All-trans retinoic acid enhances the cytotoxic effect of decitabine on myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukaemia by activating the RARα-Nrf2 complex. Br. J. cancer 128 (4), 691–701. doi:10.1038/s41416-022-02074-0

Wang, Q., Lin, Z., Wang, Z., Xian, M., Xiao, L., et al. (2022d). RARγ activation sensitizes human myeloma cells to carfilzomib treatment through the OAS-RNase L innate immune pathway. Blood 139 (1), 59–72. doi:10.1182/blood.2020009856

Wang, R., Xia, L., Gabrilove, J., Waxman, S., and Jing, Y. (2016). Sorafenib inhibition of mcl-1 accelerates ATRA-induced apoptosis in differentiation-responsive AML cells. Clin. cancer Res. official J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 22 (5), 1211–1221. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0663

Wang, X., Yu, X., Li, W., Neeli, P., Liu, M., Li, L., et al. (2022c). Expanding anti-CD38 immunotherapy for lymphoid malignancies. J. Exp. Clin. cancer Res. CR 41 (1), 210. doi:10.1186/s13046-022-02421-2

Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Su, Y., Wang, C., Liu, X., et al. (2020). miRNA-98-5p targeting IGF2BP1 induces mesenchymal stem cell apoptosis by modulating PI3K/Akt and p53 in immune thrombocytopenia. Mol. Ther. Nucleic acids 20, 764–776. doi:10.1016/j.omtn.2020.04.013

Wang, Z. Y., and Chen, Z. (2000). Differentiation and apoptosis induction therapy in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 1, 101–106. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(00)00017-6

Wass, M., Göllner, S., Besenbeck, B., Schlenk, R. F., Mundmann, P., Göthert, J. R., et al. (2021). A proof of concept phase I/II pilot trial of LSD1 inhibition by tranylcypromine combined with ATRA in refractory/relapsed AML patients not eligible for intensive therapy. Leukemia 35 (3), 701–711. doi:10.1038/s41375-020-0892-z

Weng, X. Q., Sheng, Y., Ge, D. Z., Wu, J., Shi, L., and Cai, X. (2016). RAF-1/MEK/ERK pathway regulates ATRA-induced differentiation in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells through C/EBPβ, C/EBPε and PU.1. Leukemia Res. 45, 68–74. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2016.03.008

Wu, J., Gao, Z. Y., Cui, D. M., Li, H. H., and Zeng, J. W. (2020). All-trans retinoic acid increases ARPE-19 cell apoptosis via activation of reactive oxygen species and endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 13 (9), 1345–1350. doi:10.18240/ijo.2020.09.01

Wu, W., Lin, Y., Xiang, L., Dong, W., Hua, X., Ling, Y., et al. (2016). Low-dose decitabine plus all-trans retinoic acid in patients with myeloid neoplasms ineligible for intensive chemotherapy. Ann. Hematol. 95 (7), 1051–1057. doi:10.1007/s00277-016-2681-3

Wu, Y. J., Liu, H., Zeng, Q. Z., Wang, J. W., Wang, W. S., et al. (2022). All-trans retinoic acid plus low-dose rituximab vs low-dose rituximab in corticosteroid-resistant or relapsed ITP. Blood 139 (3), 333–342. doi:10.1182/blood.2021013393

Xu, L. L., Fu, H. X., Zhang, J. M., Feng, F. E., Wang, Q. M., Zhu, X. L., et al. (2017). Impaired function of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from immune thrombocytopenia patients in inducing regulatory dendritic cell differentiation through the notch-1/jagged-1 signaling pathway. Stem cells Dev. 26 (22), 1648–1661. doi:10.1089/scd.2017.0078

Yang, J., Zhao, L., Wang, W., and Wu, Y. (2023). All-trans retinoic acid added to treatment of primary immune thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Hematol. 102 (7), 1695–1704. doi:10.1007/s00277-023-05263-w

Yilmaz, M., Kantarjian, H., and Ravandi, F. (2021). Acute promyelocytic leukemia current treatment algorithms. Blood cancer J. 11 (6), 123. doi:10.1038/s41408-021-00514-3

Yoshida, T., Mihara, K., Takei, Y., Yanagihara, K., Kubo, T., Bhattacharyya, J., et al. (2016). All-trans retinoic acid enhances cytotoxic effect of T cells with an anti-CD38 chimeric antigen receptor in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 5 (12), e116. doi:10.1038/cti.2016.73

Young, N. S. (2018). Aplastic anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 379 (17), 1643–1656. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1413485

Yu, Z., Xie, X., Su, X., Lv, H., Song, S., Liu, C., et al. (2022). ATRA-mediated-crosstalk between stellate cells and Kupffer cells inhibits autophagy and promotes NLRP3 activation in acute liver injury. Cell. Signal. 93, 110304. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2022.110304

Zhang, W., Zhou, F., Cao, X., Cheng, Y., He, A., Liu, J., et al. (2006). Successful treatment of primary refractory anemia with a combination regimen of all-trans retinoic acid, calcitriol, and androgen. Leukemia Res. 30 (8), 935–942. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2005.11.017

Zhao, W. L., Chen, S. J., Shen, Y., Xu, L., Cai, X., Chen, G. Q., et al. (2001). Treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with arsenic trioxide: clinical and basic studies. Leukemia lymphoma 42 (6), 1265–1273. doi:10.3109/10428190109097751

Keywords: all-trans retinoic acid, differentiation, acute promyelocytic leukemia, immune thrombocytopenia, CD38, clinical trials

Citation: Chen Y, Tong X, Lu R, Zhang Z and Ma T (2024) All-trans retinoic acid in hematologic disorders: not just acute promyelocytic leukemia. Front. Pharmacol. 15:1404092. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1404092

Received: 20 March 2024; Accepted: 11 June 2024;

Published: 04 July 2024.

Edited by:

Andrei Leitao, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Elena Campione, University of Rome Tor Vergata, ItalyMartin Petkovich, Queen’s University, Canada

Copyright © 2024 Chen, Tong, Lu, Zhang and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tao Ma, bWF0YW8xOTkwQHN3bXUuZWR1LmNu

Yan Chen1

Yan Chen1 Tao Ma

Tao Ma