- 1Department of Pediatric Cardiac Center, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

- 2Departments of Medicine and Physiology, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, United States

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China

- 4State Key Laboratory of Vascular Homeostasis and Remodeling, Peking University, Beijing, China

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a fatal disease caused by progressive pulmonary vascular remodeling (PVR). Currently, the mechanisms underlying the occurrence and progression of PVR remain unclear, and effective therapeutic approaches to reverse PVR and PH are lacking. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the endogenous sulfur dioxide (SO2)/aspartate transaminase system has emerged as a novel research focus in the fields of PH and PVR. As a gaseous signaling molecule, SO2 metabolism is tightly regulated in the pulmonary vasculature and is associated with the development of PH as it is involved in the regulation of pathological and physiological activities, such as pulmonary vascular cellular inflammation, proliferation and collagen metabolism, to exert a protective effect against PH. In this review, we present an overview of the studies conducted to date that have provided a theoretical basis for the development of SO2-related drug to inhibit or reverse PVR and effectively treat PH-related diseases.

1 Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is an abnormal hemodynamic state with a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) > 20 mmHg at rest, as measured by right heart catheterization (Simonneau et al., 2019). The progressive structural changes in pulmonary vasculature are the underlying cause of its life-threatening nature. With the increasing global aging population and extended survival of individuals with congenital heart and lung mal-formations, approximately 1% of the world’s population is affected by PH (Mandras et al., 2020). Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms of PH development and identifying effective strategies to prevent or reverse pulmonary vascular remodeling (PVR) are crucial topics in cardio-pulmonary vascular research. Previous studies have revealed that pulmonary vascular structural alterations are intricately regulated by various factors, including pulmonary arterial forward flow, vasoactive substances (endothelin [ET]/endostatin, nitric oxide [NO], hormones, vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor [TGF]) and genetic factors (Haworth and Reid, 1977; Benza et al., 2015; Liang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2022; Eichstaedt et al., 2023). These factors can exert differential effects at different levels and degrees on the pathological processes of endothelial cell (EC) and smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation, migration and differentiation within the pulmonary vasculature. However, the precise mechanisms underlying the development of PH remain poorly understood.

In 2008, Du and Jin et al. (Du et al., 2008) reported the existence of an endogenous sulfur dioxide (SO2) and aspartate transaminase (AAT) pathway in rat blood vessels. This discovery expanded the research of the gasotransmitter family (NO, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide [H2S] and SO2) in the field of PH, in which the SO2 pathway became a novel finding (Jin et al., 2008; Tian et al., 2008). SO2 has the biological characteristics of gasotransmitters, including sustained production, rapid diffusion, a short half-life, an ability to pass through cell membranes freely and more. Furthermore, it exerts various biological effects on the cardiovascular system and regulates pathological and physiological activities, such as cellular inflammation, apoptosis, proliferation, and collagen metabolism (Yu et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). In recent years, the in-depth research on endogenous SO2 in the vascular system has provided novel insights into the mechanisms underlying the development of PH. This review summarizes the current progress in the study of SO2 and PH.

2 Metabolism and distribution of SO2 in pulmonary vasculature

The pulmonary vascular wall consists of three layers: the intima, media, and adventitia which are primarily composed of ECs, SMCs and fibroblasts respectively (Huertas et al., 2020). Additionally, perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT), a specialized type of fat tissue, surrounds the adventitia of pulmonary blood vessels and is primarily composed of adipocytes. Furthermore, circulating cells like mast cells (MCs) and monocytes/macrophages can cross the pulmonary vascular wall, and previous studies have shown that these cells can produce various vasoactive substances that maintain the pulmonary vascular homeostasis (Breitling et al., 2017; Tinajero and Gotlieb, 2020; Hudson and Farkas, 2021; Li et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022). Recent studies have revealed that endogenous SO2 production occurs continuously in these cell populations (Liu et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021).

2.1 Synthetic metabolic pathways of SO2

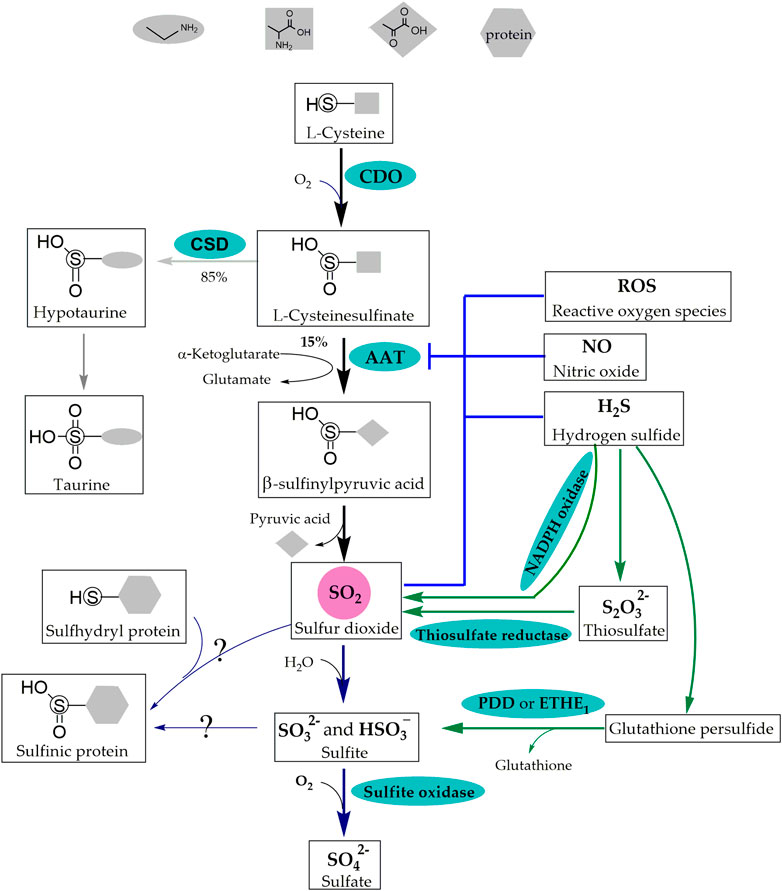

The endogenous production of SO2 can occur through two pathways: the sulfur-containing amino acid metabolic pathway and the conversion of H2S; the sulfur-containing amino acid (primarily including methionine, cysteine, and homocysteine [Hcy]) pathway has been extensively studied and is considered as the primary source of SO2 (Figure 1). This pathway has been identified in various cell types within the pulmonary vascular wall, such as ECs, SMCs and fibroblasts (Liu et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2021).

FIGURE 1. Synthetic Metabolic and Catabolic Pathways of SO2. The sulfur-containing amino acid metabolic pathway and the conversion of H2S are the two pathways of endogenous SO2 production. CDO catalyzes L-cysteine to generate L-cysteinesulfinate, 15% of which is transformed into β-sulfinylpyruvate through AAT that is inhibited by ROS, NO, H2S and SO2. β-Sulfinylpyruvate then decomposes naturally into pyruvate and SO2 in the sulfur-containing amino acid metabolic pathway. In addition, NADPH oxidase, thiosulfate reductase and PDO or ETHE1 are involved in the conversion of H2S into SO2. Molecular SO2 is rapidly converted to HSO3− and SO32-, which further transform into SO42- by sulfite oxidase or form -S (=O)-OH in protein containing thiol groups. SO2: sulfur dioxide; H2S: hydrogen sulfide; CDO: cysteine dioxygenase; AAT: aspartate aminotransferase; ROS: reactive oxygen species; NO: nitric oxide; NADPH: nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate; PDO or ETHE1: persulfide dioxygenase; HSO3− and SO32−: sulfite; SO42−: sulfate; -S (=O)-OH: sulfinic acid groups. CSD: cysteinesulfinate decarboxylase; S2O32−: thiosulfate.

2.1.1 Generation of endogenous SO2 via the sulfur-containing amino acid metabolic pathway

In the cytoplasm, L-cysteine derived from dietary intake or synthesized via transsulfuration is converted into L-cysteinesulfinate by the catalytic action of cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) (Yamaguchi et al., 1973; Kohashi et al., 1978). Subsequently, 15% of the L-cysteinesulfinate is further transformed into β-sulfinylpyruvate through AAT, which possesses cysteine sulfinic acid transaminase (CSA-T) activity. Finally, β-sulfinylpyruvate decomposes naturally into pyruvate and SO2 (Singer and Kearney, 1956; Yagi et al., 1979; Griffith, 1983; Stipanuk, 2020).

AAT is the key rate-limiting enzyme in the endogenous generation of SO2 and has two isoenzymes, AAT1 and AAT2. Immunohistochemical localization in rat brain tissue revealed that AAT1 and AAT2 were localized in the cytoplasm and mitochondria, respectively (Recasens et al., 1980; Recasens and Delaunoy, 1981).

Studies on the regulation of AAT activity and expression have revealed a competitive relationship between cysteinesulfinate decarboxylase (CSD) and AAT. Approximately 85% of L-cysteinesulfinate undergoes decarboxylation by CSD to produce taurine. Treatment with β--methylene-DL-aspartate, an irreversible inhibitor of CSD, resulted in an approximately three-fold increase in AAT transamination; however, changes in the levels of SO2 were not detected (Griffith, 1983).

Negative feedback inhibition is the most common regulatory mechanism in organisms. Song et al. (2020) reported that SO2 did not affect the protein expression of AAT1 but significantly inhibited AAT activity in purified porcine AAT1 protein. Further investigation revealed that SO2 inhibited AAT activity in ECs by sub-sulfinylation at the Cys192 site of AAT1.

There is a close interconnection between gasotransmitter molecules. In regard, Zhang et al. (2018) performed in vitro experiments using the human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) line EAhy926, primary HUVECs, primary rat pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs), and purified AAT protein from porcine heart. They discovered that the knockdown of cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) resulted in a decrease in endogenous H2S level accompanied by an increase in EC-derived SO2 level and AAT enzyme activity. However, it did not affect the expression of AAT1 and AAT2 and the alterations in the SO2/AAT pathway could be reversed by H2S donor. Mechanistic studies revealed that H2S inactivated AAT1/2 via cysteine modification to inhibit endogenous SO2 generation. In 2021, Song et al. (2020) reported that in L-NAME-induced hypertensive mice, plasma NO level was reduced, whereas SO2 level was elevated in L-NAME-induced hypertensive mice. Furthermore, in a coculture system of human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) and human aortic smooth muscle cells (HASMCs), the HAEC-derived NO did not affect AAT1 protein expression but decreased AAT1 activity in HASMCs, consequently inhibiting HASMC-derived SO2 production. Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry demonstrated that NO inhibited AAT1 activity by S-nitrosylation at the Cys192 site of purified AAT1 protein. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) modulate the activities of various enzymes through redox modification. In vitro experiments with vascular SMCs showed that the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine and antioxidant glutathione (GSH) significantly abolished the downregulation of the SO2/AAT pathway induced by ET-1 stimulation (Tian et al., 2020), suggesting that ROS inhibited the endogenous SO2/AAT pathway.

2.1.2 Endogenous generation of SO2 via H2S transformation

H2S transformation into SO2 occurs in three ways: 1) nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NADPH oxidase) participates in an oxidative stress reaction, which converts H2S into SO2. This process was observed in activated neutrophils (Mitsuhashi et al., 2005); 2) H2S generates thiosulfate in a non-enzymatic reaction and cytoplasmic thiosulfate reductase catalyzes the conversion of thiosulfate (S2O32-) to SO2 (Kamoun, 2004; Cao et al., 2019); 3) mitochondrial persulfide dioxygenase (PDO or ETHE1) catalyzes the conversion of non-enzymatically generated glutathione persulfide (GSSH) derived from H2S into sulfite (SO32-) and glutathione (GSH) (Hildebrandt and Grieshaber, 2008; Kabil et al., 2018; Stipanuk, 2020).

2.2 Catabolic pathways of SO2

In 1995, Ji et al. (1995) reported that the concentration of SO32− in normal human serum, as detected by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), was significantly low, ranging from 0 to 9.85 μM. Subsequently, the research group headed by Du and Jin were the first to report the presence of SO32− (3.27 ± 0.21 µmol/[gprotein]) in rat pulmonary vascular tissue (Du et al., 2008). The findings of previous studies have thus indicted that in body fluids, a larger proportion of molecular SO2 is rapidly converted to its hydrated form (HSO3− and SO32−), which is further converted to sulfate (SO42−) under the catalytic action of sulfite oxidase (Figure 1) (Singer and Kearney, 1956). SO42- is then excreted through the kidneys to maintain the metabolic homeostasis of sulfur-containing amino acids in the body (Stipanuk, 2020). However, recent research has reported that the lifetime of gasotransmitters may be much longer than those previously estimated (Elrod et al., 2008; Bahadoran et al., 2020). Furthermore, body fluid contains significant amounts of protein, such as plasma albumin and functional proteins containing thiol groups. The application of exogenous SO2 donor indicated that SO32− could react with functional proteins containing thiol groups to form proteins containing sulfinic acid groups (-S [ = O]-OH); however, the enzymes involved in this reaction have not been investigated (Chen et al., 2017). These findings suggest that molecular SO2, SO32− and proteins containing “-S (=O)-OH” in body fluid may function as a whole.

2.3 Distribution of SO2 in the pulmonary circulation

Considering that SO32− may be the primary form of endogenous SO2 in the pulmonary circulation, current researchers primarily focus on detecting SO32− using HPLC for the analysis of lung tissues or fluorescence probe-based detection in cultured pulmonary vascular cells to indicate the level of SO2 (Du et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). However, given that SO2 fluorescent probe cannot be used to measure SO32- in tissues (Huang et al., 2022), the distribution of SO2 in the vessels of animal tissues was indirectly assessed via in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence to detect the mRNA and protein expression of the key enzyme AAT, which indirectly reflected the differential distribution of SO2 in the vasculature (Du et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2021).

2.3.1 Tissue distribution

In adult rat cardiac tissue, the mRNA, protein expression and activity of AAT1 and AAT2 were significantly higher than those in the lung tissue. In contrast, however, the concentration and production rate of SO2 in the heart were not significantly higher than those in the lung, suggesting that tissue SO2 content did not exhibit a simple linear relationship with AAT expression and activity (Luo et al., 2011). This in turn provides evidence to indicate that tissue SO2 content may be subject to more stringent regulation or alternatively, is influenced by circulating SO2. Du et al. (2008) investigated the endogenous production of SO2 and the expression of AAT mRNA in different rat vascular tissues, providing initial evidence of the existence of endogenous SO2 within the vascular system. Indirect analysis of endogenous SO2 level in different rat vascular tissues was performed by measuring HSO3− and SO32− content using HPLC. The results showed that the aortic tissue exhibited the highest level of endogenous SO2 among the rat vascular tissues, followed by the pulmonary, mesenteric, tail and renal arteries. Notably, the relationship between the AAT activity and SO2 content was non-linear. Using a colorimetric method to determine AAT activity, Du and Jin et al. (Du et al., 2008) reported that AAT activity was the highest in the renal artery, followed by the tail, mesenteric, pulmonary and aorta arteries. However, given the limitations of the SO2 detection methods and the diversity of SO2 chemical forms, these results indicating changes in AAT activity in different vascular tissues may not necessarily reflect the actual changes in SO2 content. In recent research, SO2 content in adipose tissue was measured using HPLC and the localization and qualitative expressions of the mRNA and protein of AAT1 and AAT2 were investigated. These results demonstrated the presence of the SO2/AAT pathway in various adipose tissues of rats, including the PVAT and perirenal, epididymal, subcutaneous, and brown adipose tissues (Zhang et al., 2016).

2.3.2 Cellular distribution

Previous studies focusing on the distribution of SO2 in vascular tissues revealed a predominant distribution of AAT1 and AAT2 mRNA in ECs and SMCs near the intima in the rat aorta by in situ hybridization (Du et al., 2008). Subsequently, immunofluorescence analysis of mouse lung tissue sections showed that the highest expression of AAT1 protein was in PAECs. Furthermore, the detection of HSO3− and SO32- using SO2 probe indicated the endogenous production of SO2 in human PAECs (HPAECs) (Liu et al., 2021). The presence of the endogenous SO2/AAT pathway in pulmonary vascular SMCs and fibroblasts involved in PVR was demonstrated by HPLC, SO2 probes, and Western blot experiments (Liu et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016).

Additionally, the endogenous SO2/AAT pathway is present in cell types that those are closely associated with PVR, such as perivascular adipocytes, MCs and macrophages. Analysis using HPLC and Western blot demonstrated the presence of endogenous SO2/AAT1 pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Zhang et al., 2016). Zhu et al. (2020) detected the endogenous production of SO2 in mouse macrophages using HPLC and SO2 probe; moreover, Western blot analysis confirmed the mouse macrophage-derived protein expression of AAT2. Latterly Zhang et al. (2021) reported the existence of endogenous SO2/AAT1 pathway in human MCs in vitro.

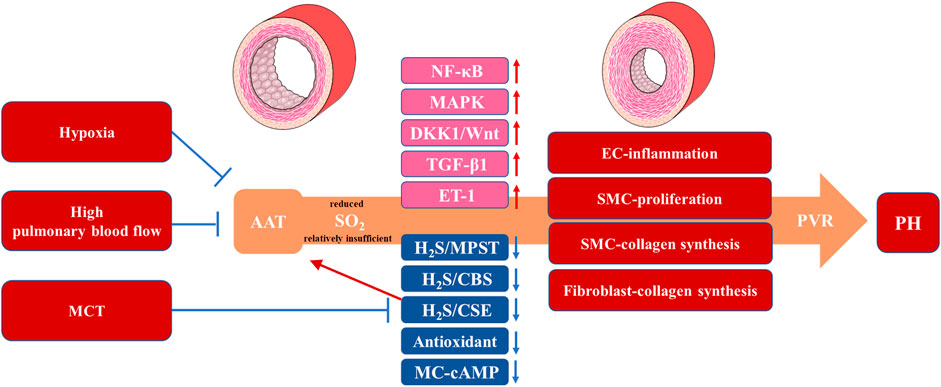

3 Metabolic changes of SO2 in PH

Pulmonary arterial pressure gradually decreases after birth. Factors, such as respiration, lung expansion and the closure of ductus arteriosus, contribute to a decline by approximately 50% in pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary arterial pressure. This results in increased pulmonary blood flow, which contributes to the dilation of pulmonary blood vessels and a progressive increase in the number of pulmonary arterioles. Consequently, the luminal diameter of the pulmonary arterioles expands and the vessel walls become thin leading to a sustained decrease in pulmonary arterial pressure (Hislop, 2002). However, ventricular septal defects, pulmonary developmental abnormalities, abnormal lung development or inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can impede or reverse the decline in pulmonary arterial pressure through constriction of pulmonary blood vessels, reduction in the number of pulmonary vessels and PVR (Bonafiglia et al., 2022; Golovenko et al., 2022; Kovacs et al., 2022). As the gasotransmitter family has gained increasing attention and recognition in PVR research, the first member, NO has been successfully applied in the clinical treatment of PH (Ziegler et al., 1998; Creagh-Brown et al., 2009) and the novel gasotransmitter SO2 has recently garnered increasing focus on its metabolic changes in PH (Figure 2) (Jin et al., 2008; Luo et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2022).

FIGURE 2. The Metabolic Changes and Protective Roles of SO2 in Animal PH Models. Animal experimental results suggest a reduced or relatively insufficient endogenous SO2 production mediated by AAT under hypoxia, high pulmonary blood flow and MCT, which promotes or suppresses signaling pathways (NF-κB, MAPK, DKK1/Wnt, TGF-β1, H2S/MPST/CBS/CSE and MC-cAMP) and vasoactive substances (ET-1 and antioxidant) associated with the pathological progress in EC-inflammation, SMC-proliferation, SMC-collagen synthesis and fibroblast-collagen synthesis. These pathological processes cause PVR manifesting as a thickening of the pulmonary vascular wall and PH with an mPAP >20 mmHg. SO2: sulfur dioxide; PH: pulmonary hypertension; AAT: aspartate aminotransferase; MCT: monocrotaline; H2S: hydrogen sulfide; 3-MPST: 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MPST); CBS: cystathionine β-synthase; CSE: cystathionine γ-lyase; MC: mast cell; ET-1: endothelin-1; EC: endothelial cell; SMC: smooth muscle cell; PVR: pulmonary vascular remodeling; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure.

3.1 Metabolism of SO2 in clinical PH

Limited research has been conducted on endogenous SO2 in clinical PH and has been restricted to children with congenital heart disease-associated PH (CHD-PH). In 2014, Yang et al. (2014) conducted a prospective cohort study to investigate the relationship between plasma SO2 level and pulmonary arterial pressure in children with CHD-PH. On the basis of HPLC analysis, they discovered that in children with left-to-right shunt CHD, the measured levels of SO32- in the control, CHD without PH, CHD with mild PH and CHD with moderate-to-severe PH groups were 10.6 ± 2.4, 8.9 ± 2.3, 7.3 ± 2.9 and 4.3 ± 2.1 μM, respectively. These values were consistent with the serum concentration of HSO3− and SO32- reported by Ji et al. (1995), which ranged from 0 to 9.85 μM in healthy individuals. Pearson’s correlation analysis showed a negative correlation between SO2 level and pulmonary arterial pressure in all CHD groups. Across all four groups, there was a negative correlation between SO2 and Hcy levels. These results suggested a decrease in endogenous SO2 level in children with CHD-PH and the degree of SO2 downregulation may reflect the severity of CHD-PH to some extent. An elevated Hcy level indicated a close association between reduced SO2 and the Hcy-SO2/AAT pathway, a metabolic pathway for sulfur-containing amino acids. A nationwide study has reported a linear correlation between serum AAT and age in Middle Eastern children and adolescents (Kelishadi et al., 2012). However, Li et al. (2018) revealed that the reference range for serum AAT based on adult standards did not apply to adolescents and established the reference ranges for serum AAT in Chinese adolescent boys and girls as 12.8–40.2 U/L and 10.4–32.5 U/L, respectively, to guide clinical practice. However, research on the association between human AAT and PH has not yet been published.

3.2 SO2 metabolism in experimental PH models

Because of the difficulty in obtaining lung tissue specimens from patients with PH in clinical settings, researchers have predominantly utilized various animal models to investigate changes in the SO2/AAT pathway during the development of PH. Consistent with the clinical observation of PH, significant changes in the endogenous SO2/AAT pathway have been observed in monocrotaline (MCT), hypoxia and high pulmonary blood flow induced PH models.

Jin et al. (2008) were the first to investigate the metabolic changes in the endogenous SO2/AAT pathway in the MCT-induced rat PH model. The results showed that compared to the control group, MCT-treated rats exhibited significantly increased mPAP and right ventricle/(left ventricle + septum) ratio, accompanied by elevated SO2 content, AAT activity, and AAT1 and AAT2 mRNA expression in the lung tissue. Subsequently, Yu et al. (2016) reported a significant increase in AAT1 protein expression but no significant change in AAT2 protein expression in the lung tissue of MCT-induced rat PH models, suggesting that MCT primarily induced the upregulation of the endogenous SO2/AAT1 pathway in the lung tissue. How did MCT induce the upregulation of the SO2/AAT1 pathway. Combining previous studies confirming the inhibition of H2S generation in rat lung tissues and HPAECs by MCT (Feng et al., 2017), Jin and Du et al. (Zhang et al., 2018) found that a deficiency in endogenous H2S caused by the knockdown of CSE in rat primary PAECs increased endogenous SO2 level and enhanced the enzymatic activity of AAT without affecting the expression of AAT1 and AAT2. Furthermore, H2S donor reversed the increase in endogenous SO2 content and AAT activity induced by CSE knockdown. In addition, H2S donor directly inhibited the activity of purified AAT1 protein, which was reversed by the thiol-reducing agent dithiothreitol. Collectively, the studies above suggested that MCT initially reduced H2S level in rat PAECs, consequently weakening the inhibitory effect of H2S on the cysteine modification of AAT1 protein, thereby leading to increased AAT activity and SO2 content in PAECs. However, the mechanism underlying the increase in AAT1 protein expression remains unclear; this may be associated with the different experimental periods between animal studies and cell experiments.

In studies on hypoxia-induced PH, (Tian et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010) detected significant decreases in SO2 content, AAT1 and AAT2 mRNA levels, and AAT activity in the plasma and lung tissue of rats with hypoxia-induced PH compared with those in the control group. In mouse hypoxia-induced PH and hypoxic HPAEC models, the downregulation of the SO2/AAT1 pathway in mouse lung tissues and PAECs was observed using HPLC and SO2 probe to detect SO2 concentration, and immunofluorescence and Western blot to evaluate PAEC-derived AAT1 expression (Liu et al., 2021). However, the specific mechanisms underlying hypoxia-induced downregulation of SO2/AAT1 pathway remain unclear.

The high pulmonary blood flow model is used to simulate the development of CHD- PH, and in this regard, Luo et al. (2013) found that compared with the sham group, rats in the shunt group exhibited a significant increase in pulmonary artery systolic pressure, accompanied by a significant decrease in SO2 concentration, AAT activity and AAT2 protein and mRNA expression levels in the lung tissue. Subsequently, Liu et al. (2016) reported that there were significant reductions in SO2 concentration, AAT activity and AAT1 protein expression in a mechanical stretch model of pulmonary artery fibroblasts (PAFs), indicating that excessive pulmonary artery dilation caused by high pulmonary blood flow contributed to the downregulation of the SO2/AAT pathway in high pulmonary blood flow-induced rat PH models.

4 Protective roles of SO2 in PH

PH is a prevalent and life-threatening disease characterized by PVR, involving PAEC dysfunction, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell (PASMC) and PAF proliferation and collagen accumulation in the pulmonary arteries (Christou and Khalil, 2022; Milara et al., 2022; Veith et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Previous studies have reported that an imbalance in various vasoactive small molecules, including gasotransmitters, plays a crucial role in PVR progression (Klinger et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2022; Turhan et al., 2022). Additionally, as a newly discovered gasotransmitter, SO2 is involved in the regulation of pathophysiological processes in the pulmonary vasculature and aorta (Supplementary Table S1), such as vascular cell inflammation, apoptosis, proliferation, and collagen metabolism (Yu et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). There is a growing body of literature comprising studies that have examined the protective role of SO2 in animal PH models using exogenous SO2 donor or genetically modified mice (Figure 2).

4.1 Hypoxia-induced PH models

Varying degrees of hypoxia occurs in the lungs of patients with PH caused by COPD, connective tissue disease or other conditions. Hypoxia is the most significant pathogenic factor contributing to PVR and the development of PH (Stenmark et al., 2006). Therefore, researchers frequently employ the principle of hypoxia to develop animal PH models.

Tian et al. (2008) investigated the effect of SO2 on PVR in a rat model of hypoxia-induced PH. They discovered that exogenous SO2 donor could suppress the elevation of mPAP induced by hypoxia and improve changes in the relative medial thickness of muscular arteries and the ultrastructure of PAECs and SMCs. Subsequently, the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the inhibition of PVR by endogenous and exogenous SO2 in the rat model of hypoxia-induced PH were explored by Chen and Sun independently. By focusing on the interaction among sulfur-containing gasotransmitters, Chen et al. (2011) discovered that providing exogenous SO2 donor upregulated the expression of the H2S-generating enzyme CSE in the pulmonary artery intima and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MPST) protein in the pulmonary artery media, leading to increased H2S production and indirectly alleviating hypoxia-induced PH. Sun et al. (2010) first employed L-aspartate-β-hydroxamate (HDX) to inhibit endogenous SO2 production and demonstrated that HDX exacerbated hypoxia-induced elevation of pulmonary arterial pressure and PVR. The molecular mechanisms involved included inflammation-related factor ICAM-1 and the NF-κB signaling pathway in PAECs, proliferating cell nuclear antigen and the MAPK (Raf-1/MEK-1/ERK) signaling pathway in PASMCs, and ET-1 and collagen metabolism in the lung tissue. Furthermore, the administration of exogenous SO2 donor mitigated the aforementioned hypoxia-induced molecular changes, which were consistent with the findings of Tian et al. (Tian et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010).

After our previous study revealed an association between SO2, ICAM-1 and the NF-κB signaling pathway in hypoxia-induced PAEC inflammation (Sun et al., 2010), we further employed transgenic technology to enhance endogenous SO2 generation in mouse PAECs. The results showed that, similar to the effects of exogenous SO2, endogenous SO2 generated by PAECs significantly suppressed the expression of ICAM-1, an inflammation-related factor, in mice with hypoxia-induced PH. At the cellular level, inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway attenuated the expression of ICAM-1 and MCP-1 induced by SO2 reduction in HPAECs (Liu et al., 2021). Therefore, our findings demonstrated that the NF-κB signaling pathway mediated the inhibitory effect of SO2 on the abnormal inflammatory response of PAECs in the development of hypoxia-induced PVR and PH.

Studies on the effects of SO2 on PASMC proliferation and collagen metabolism in the context of hypoxia have implicated not only the MAPK signaling pathway involved, but also the Wnt and NF-κB signaling pathways. Members of the Wnt signaling pathway, including Wnt7b, Sfrp2, and Dkk1, participate in vascular cell survival, proliferation, migration and morphogenesis, and Dkk1 inhibits the Wnt signaling (Clevers and Nusse, 2012). In 2018, Luo et al. (Luo et al., 2018) investigated the mechanisms by which SO2 inhibits hypoxia-induced PVR. Through RNA-seq analysis of mRNA expression profiles in mouse normal and hypoxic pulmonary arteries, 509 differentially expressed mRNAs were identified. The results obtained in both RNA-seq and PCR analyses provided evidence to indicate the significant downregulation of Wnt7b, Sfrp2 and Cacna1f mRNA expression and a significant upregulation of Dkk1 mRNA expression in the pulmonary arteries of the hypoxic PH group. Interestingly, SO2 upregulated Wnt7b, Sfrp2, and Cacna1f mRNA levels and downregulated Dkk1 mRNA level in the pulmonary arteries under hypoxia. Further research confirmed that SO2 inhibited hypoxia-induced PASMC migration. To date, the NF-κB signaling pathway has been extensively studied and is involved in the regulation of various cellular processes, including proliferation, inflammation, differentiation and apoptosis (Oeckinghaus et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2017). Using a mouse model of hypoxic PH, we observed that EC-derived SO2 significantly suppressed Ki-67 and collagen I expression in PASMCs. Furthermore, blockade of the NF-κB signaling pathway abolished the effect of SO2 reduction on the overexpression of Ki-67 and collagen I in human PASMCs (Liu et al., 2021). These findings suggested that the inhibitory effects of SO2 on PASMC proliferation, migration and collagen metabolism were associated with the Dkk1/Wnt and NF-κB signaling pathways in hypoxia-induced PVR.

In 2020, Zhang (Zhang et al., 2021) first identified the endogenous SO2/AAT1 pathway in MCs. To further investigate whether cAMP mediates the inhibitory effect of endogenous SO2 on MC degranulation, researchers used the PDE inhibitor IBMX or the AC activator forskolin to increase cAMP level in MCs and discovered that IBMX and forskolin successfully terminated MC degranulation induced by AAT1 knockdown. Additionally, in hypoxia-stimulated MCs, AAT1 protein expression and SO2 production were significantly downregulated, resulting in the activation of MC degranulation. However, AAT1 overexpression, which increased endogenous SO2 levels, inhibited MC degranulation, and this inhibitory effect was disrupted by the cAMP synthesis inhibitor SQ22536. The results from animal experiments supported these findings and showed that the mRNA and protein expression of AAT1 significantly decreased in rat lung tissue under hypoxia. Treatment with SO2 donor increased cAMP level in the lung tissue of hypoxic rats and reduced the accumulation and degranulation of MCs around the pulmonary arteries. These studies suggested that SO2 acted as an endogenous stabilizer of MCs by upregulating the cAMP pathway to inhibit MC degranulation. Given the significant role of MC degranulation in pulmonary vascular inflammation and PVR, inhibition of MC degranulation may be an essential mechanism by which MC-derived SO2 suppresses hypoxia-induced PVR.

4.2 High pulmonary blood flow-induced CHD-PH model

The endogenous SO2 system is involved in the development of PH induced by high pulmonary blood flow. Luo et al. investigated the role of the SO2/AAT2 pathway in the pathogenesis of PH induced by high pulmonary blood flow in 2013. The study revealed that administering SO2 donor alleviated the elevation in pulmonary arterial pressure caused by high pulmonary blood flow and reduced the degree of pulmonary arterial muscularization. Additionally, SO2 donor increased the production of H2S in rat lung tissue, upregulated the protein and mRNA expressions of CSE, and increased 3-MPST and cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) mRNA levels (Luo et al., 2013). These results suggested that SO2 reduced PH induced by high pulmonary blood flow and exerted a protective effect against pulmonary vascular pathology, which was associated with the upregulation of the endogenous H2S pathway.

Liu et al. (2016) investigated the role of the endogenous SO2/AAT1 pathway in collagen synthesis in the fibroblasts of rats with high pulmonary blood flow-induced PH. These results demonstrated that reduced endogenous SO2 level promoted collagen accumulation in the lung tissues of rats with shunt-induced PH. Further mechanistic studies revealed that endogenous SO2 inhibited the activation of the TGF-β1 signaling pathway in PAFs, consequently suppressing pulmonary vascular collagen synthesis. In a model of mechanical stretching-induced PAF collagen synthesis, AAT1 overexpression increased endogenous SO2 production and inhibited TGF-β1 expression and Smad2/3 phosphorylation. Conversely, AAT1 knockdown simulated the effects of mechanical stretching, leading to increased TGF-β1 expression and Smad2/3 phosphorylation. Additionally, the use of the TGF-β1/Smad2/3 signaling pathway inhibitor SB431542 eliminated the excessive accumulation of collagen I and collagen III induced by AAT1 knockdown, mechanical stretch or a combination of both. Furthermore, in a rat model of pulmonary vascular collagen accumulation induced by high pulmonary blood flow, supplementation with SO2 donor inhibited the activation of TGF-β1/Smad2/3 signaling pathway and alleviated excessive collagen deposition in the lung tissue of rats with shunt-induced PH. These findings indicated that the endogenous SO2/AAT1 pathway could inhibit the activation of the TGF-β1/Smad2/3 signaling pathway to suppress the abnormal collagen accumulation induced by mechanical stretching in PAFs.

4.3 MCT-induced PH model

Endogenous SO2 exerts an inhibitory effect on MCT-induced redox injury and collagen synthesis in the lung tissue, thereby antagonizing MCT-induced PH formation. In 2008, Jin et al. (2008) investigated the regulatory role of endogenous SO2 in a rat model of MCT-induced PH and administered HDX to inhibit the upregulation of the SO2/AAT1/2 pathway induced by MCT. The results showed that compared to the MCT group, rats treated with MCT + HDX exhibited significantly increased mPAP and PVR and a significant decrease in lung tissue antioxidant substances. However, intervention with SO2 donor significantly reduced PVR in rats and increased the levels of antioxidant substances in the lung tissue. These findings suggest that endogenous SO2 enhanced the antioxidant capacity of lung tissue and inhibited MCT-induced PVR and PH. In 2016, Yu et al. (Yu et al., 2016) investigated the role of endogenous SO2 in MCT-induced pulmonary vascular collagen synthesis and revealed that the inhibition of endogenous SO2 generation in the lung tissue by HDX further aggravated MCT-induced collagen synthesis in rat pulmonary vessels. Conversely, supplementation with SO2 donor suppressed MCT-stimulated collagen synthesis and increased collagen degradation to alleviate pulmonary vascular collagen remodeling.

Mechanistic insights revealed that SO2 donor downregulated the expression of TGF-β1 induced by MCT in pulmonary arteries and alleviated pulmonary vascular collagen remodeling, suggesting the involvement of TGF-β1-related signaling pathways in the protective effect of SO2. Further investigations using cultured PAFs stimulated with TGF-β1 have shed light on the mechanisms underlying the effects of AAT1 overexpression in promoting an increased endogenous SO2 level and preventing the activation of the TGF-β/TβRI/Smad2/3 signaling pathway, as well as abnormal collagen synthesis in PAFs. Conversely, in TGF-β1-treated PAFs, AAT1 knockdown reduced endogenous SO2 level, exacerbated Smad2/3 phosphorylation, and collagen I and collagen III deposition (Yu et al., 2016). These results supported the notion that endogenous SO2 inhibited the activation of the TGF-β/TβRI/Smad2/3 signaling pathway in PAFs, thereby suppressing MCT-induced collagen synthesis in rat pulmonary arteries.

5 Significance and prospects of SO2 in PH

Taken together, insufficient endogenous production of SO2 has been recognized as an important pathogenic mechanism underlying PH and PVR. The SO2/AAT pathway serves as a crucial endogenous regulatory pathway in PAECs, PASMCs, PAFs, macrophages, MCs and other cell types. Moreover, molecular SO2, HSO3−, SO32− and proteins containing -S (=O)-OH in body fluids may act as a whole controlled by a complex and incompletely elucidated metabolic regulatory network (Chen et al., 2017; Song et al., 2020; Stipanuk, 2020; Huang et al., 2022). The degree of downregulation of HSO3− and SO32− can partly reflect the severity of CHD-PH (Yang et al., 2014). Supplementation with SO2 donor in animal models of PH induced by hypoxia, monocrotaline or high pulmonary blood flow significantly inhibited PVR by attenuating inflammation, proliferation and collagen dysregulation in the pulmonary vascular wall; thus, preventing the development of PH (Jin et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2013).

Previous clinical treatment strategies for PH have primarily focused on the excessive vasoconstriction of pulmonary blood vessels. However, the structural damage to blood vessels limits the efficacy of vasodilator drugs (Shah et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the successful application of NO, the first gaseous signaling molecule used in the treatment of PH, provides a positive reference for the treatment of clinical PH with SO2 (Yu et al., 2019). To date, there have been few assessments of the therapeutic effects of SO2 on clinical PH and the limitations of its clinical application. Given the strong and pungent odor of SO2 gas, along with its unsafe storage, high price, and inconvenient portability, the most commonly used SO2 donor is a mixture of HSO3− and SO32−. However, the emergence of SO2 prodrugs that can simulate the slow release of endogenous SO2 in vivo and can bound lipid nanoparticles targeting the lungs, would make it possible to enhance the pulmonary specificity and stability of SO2 protection against vascular remodeling through inhaled prodrugs, and to avoid the side effects of systemic hypotension (Wang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). In addition, the development of small molecule activators for SO2 synthase also has broad prospects. In general, considering that molecular SO2, HSO3−, SO32− and proteins containing -S (=O)-OH may act together as a whole, further exploration of the regulatory role and mechanisms of SO2 in PH and PVR, and the development of SO2 prodrugs holds the potential to utilize SO2-related medications to inhibit or reverse PVR and would improve the clinical treatment efficacy and quality of life for patients with PH-related diseases.

Author contributions

XL: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing–review and editing. HZ: Writing–review and editing. HZ: Writing–review and editing. HJ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. YH: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Science and Technology Development Fund of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, grant number AZYZR202203.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1282403/full#supplementary-material

References

Bahadoran, Z., Carlström, M., Mirmiran, P., and Ghasemi, A. (2020). Nitric oxide: to be or not to be an endocrine hormone? Acta physiol. Oxf. Engl. 229 (1), e13443. doi:10.1111/apha.13443

Benza, R. L., Gomberg-Maitland, M., Demarco, T., Frost, A. E., Torbicki, A., Langleben, D., et al. (2015). Endothelin-1 pathway polymorphisms and outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. care Med. 192 (11), 1345–1354. doi:10.1164/rccm.201501-0196OC

Bonafiglia, Q. A., Zhou, Y. Q., Hou, G., Saha, R., Hsu, Y. R., Burke-Kleinman, J., et al. (2022). Deficiency in DDR1 induces pulmonary hypertension and impaired alveolar development. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 67 (5), 562–573. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2022-0124OC

Breitling, S., Hui, Z., Zabini, D., Hu, Y., Hoffmann, J., Goldenberg, N. M., et al. (2017). The mast cell-B cell axis in lung vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. physiology Lung Cell. Mol. physiology 312 (5), L710–L21. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00311.2016

Cao, X., Ding, L., Xie, Z. Z., Yang, Y., Whiteman, M., Moore, P. K., et al. (2019). A review of hydrogen sulfide synthesis, metabolism, and measurement: is modulation of hydrogen sulfide a novel therapeutic for cancer? Antioxidants redox Signal. 31 (1), 1–38. doi:10.1089/ars.2017.7058

Chen, J., Rodriguez, M., Miao, J., Liao, J., Jain, P. P., Zhao, M., et al. (2022). Mechanosensitive channel Piezo1 is required for pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am. J. physiology Lung Cell. Mol. physiology 322 (5), L737–L760. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00447.2021

Chen, S., Huang, Y., Liu, Z., Yu, W., Zhang, H., Li, K., et al. (2017). Sulphur dioxide suppresses inflammatory response by sulphenylating NF-κB p65 at Cys(38) in a rat model of acute lung injury. Clin. Sci. Lond. Engl. 1979) 131 (21), 2655–2670. doi:10.1042/CS20170274

Chen, S. Y., Jin, H. F., Sun, Y., Tian, Y., Tang, C. S., and Du, J. B. (2011). Impact of sulfur dioxide on hydrogen sulfide/cystathionine-γ-lyase and hydrogen sulfide/mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase pathways in the pathogenesis of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats. Zhonghua er ke za zhi = Chin. J. Pediatr. 49 (12), 890–894. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2011.12.003

Christou, H., and Khalil, R. A. (2022). Mechanisms of pulmonary vascular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension and implications for novel therapies. Am. J. physiology Heart circulatory physiology 322 (5), H702–H724. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00021.2022

Clevers, H., and Nusse, R. (2012). Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 149 (6), 1192–1205. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012

Creagh-Brown, B. C., Griffiths, M. J., and Evans, T. W. (2009). Bench-to-bedside review: inhaled nitric oxide therapy in adults. Crit. care (London, Engl. 13 (3), 221. doi:10.1186/cc7734

Du, S. X., Jin, H. F., Bu, D. F., Zhao, X., Geng, B., Tang, C. S., et al. (2008). Endogenously generated sulfur dioxide and its vasorelaxant effect in rats. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 29 (8), 923–930. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00845.x

Eichstaedt, C. A., Belge, C., Chung, W. K., Gräf, S., Grünig, E., Montani, D., et al. (2023). Genetic counselling and testing in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a consensus statement on behalf of the International Consortium for Genetic Studies in PAH. Eur. Respir. J. 61 (2), 2201471. doi:10.1183/13993003.01471-2022

Elrod, J. W., Calvert, J. W., Gundewar, S., Bryan, N. S., and Lefer, D. J. (2008). Nitric oxide promotes distant organ protection: evidence for an endocrine role of nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 (32), 11430–11435. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800700105

Feng, S., Chen, S., Yu, W., Zhang, D., Zhang, C., Tang, C., et al. (2017). H2S inhibits pulmonary arterial endothelial cell inflammation in rats with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Laboratory investigation; a J. Tech. methods pathology 97 (3), 268–278. doi:10.1038/labinvest.2016.129

Golovenko, O., Lazorhyshynets, V., Prokopovych, L., Truba, Y., DiSessa, T., and Novick, W. (2022). Early and long-term results of ventricular septal defect repair in children with severe pulmonary hypertension and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance by the double or traditional patch technique. Eur. J. cardio-thoracic Surg. official J. Eur. Assoc. Cardio-thoracic Surg. 62 (2), ezac347. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezac347

Griffith, O. W. (1983). Cysteinesulfinate metabolism. altered partitioning between transamination and decarboxylation following administration of beta-methyleneaspartate. J. Biol. Chem. 258 (3), 1591–1598. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)33025-4

Haworth, S. G., and Reid, L. (1977). Quantitative structural study of pulmonary circulation in the newborn with pulmonary atresia. Thorax 32 (2), 129–133. doi:10.1136/thx.32.2.129

Hildebrandt, T. M., and Grieshaber, M. K. (2008). Three enzymatic activities catalyze the oxidation of sulfide to thiosulfate in mammalian and invertebrate mitochondria. FEBS J. 275 (13), 3352–3361. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06482.x

Hislop, A. A. (2002). Airway and blood vessel interaction during lung development. J. Anat. 201 (4), 325–334. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00097.x

Huang, Y., Tang, C., Du, J., and Jin, H. (2016). Endogenous sulfur dioxide: a new member of gasotransmitter family in the cardiovascular system. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 8961951. doi:10.1155/2016/8961951

Huang, Y., Zhang, H., Lv, B., Tang, C., Du, J., and Jin, H. (2021). Endogenous sulfur dioxide is a new gasotransmitter with promising therapeutic potential in cardiovascular system. Sci. Bull. 66 (16), 1604–1607. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2021.04.003

Huang, Y., Zhang, H., Lv, B., Tang, C., Du, J., and Jin, H. (2022). Sulfur dioxide: endogenous generation, biological effects, detection, and therapeutic potential. Antioxidants redox Signal. 36 (4-6), 256–274. doi:10.1089/ars.2021.0213

Hudson, J., and Farkas, L. (2021). Epigenetic regulation of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (22), 12098. doi:10.3390/ijms222212098

Huertas, A., Tu, L., Humbert, M., and Guignabert, C. (2020). Chronic inflammation within the vascular wall in pulmonary arterial hypertension: more than a spectator. Cardiovasc. Res. 116 (5), 885–893. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvz308

Ji, A. J., Savon, S. R., and Jacobsen, D. W. (1995). Determination of total serum sulfite by HPLC with fluorescence detection. Clin. Chem. 41 (61), 897–903. doi:10.1093/clinchem/41.6.897

Jin, H. F., Du, S. X., Zhao, X., Wei, H. L., Wang, Y. F., Liang, Y. F., et al. (2008). Effects of endogenous sulfur dioxide on monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 29 (10), 1157–1166. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00864.x

Kabil, O., Motl, N., Strack, M., Seravalli, J., Metzler-Nolte, N., and Banerjee, R. (2018). Mechanism-based inhibition of human persulfide dioxygenase by γ-glutamyl-homocysteinyl-glycine. J. Biol. Chem. 293 (32), 12429–12439. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA118.004096

Kamoun, P. (2004). Endogenous production of hydrogen sulfide in mammals. Amino acids 26 (3), 243–254. doi:10.1007/s00726-004-0072-x

Kelishadi, R., Abtahi, S. H., Qorbani, M., Heshmat, R., Esmaeil Motlagh, M., Taslimi, M., et al. (2012). First national report on aminotransaminases' percentiles in children of the Middle East and north africa (MENA): the CASPIAN-III study. Hepat. Mon. 12 (11), e7711. doi:10.5812/hepatmon.7711

Klinger, J. R., Abman, S. H., and Gladwin, M. T. (2013). Nitric oxide deficiency and endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. care Med. 188 (6), 639–646. doi:10.1164/rccm.201304-0686PP

Kohashi, N., Yamaguchi, K., Hosokawa, Y., Kori, Y., Fujii, O., and Ueda, I. (1978). Dietary control of cysteine dioxygenase in rat liver. J. Biochem. 84 (1), 159–168. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132104

Kovacs, G., Avian, A., Bachmaier, G., Troester, N., Tornyos, A., Douschan, P., et al. (2022). Severe pulmonary hypertension in COPD: impact on survival and diagnostic approach. Chest 162 (1), 202–212. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2022.01.031

Li, B., Manan, R. S., Liang, S. Q., Gordon, A., Jiang, A., Varley, A., et al. (2023). Combinatorial design of nanoparticles for pulmonary mRNA delivery and genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1038/s41587-023-01679-x

Li, M., Riddle, S., Kumar, S., Poczobutt, J., McKeon, B. A., Frid, M. G., et al. (2021). Microenvironmental regulation of macrophage transcriptomic and metabolomic profiles in pulmonary hypertension. Front. Immunol. 12, 640718. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.640718

Li, Y., Mussa, A. E., Tang, A., Xiang, Z., and Mo, X. (2018). Establishing reference intervals for ALT, AST, UR, Cr, and UA in apparently healthy Chinese adolescents. Clin. Biochem. 53, 72–76. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.01.019

Li, Y., Qu, J., Zhang, P., and Zhang, Z. (2020). Reduction-responsive sulfur dioxide polymer prodrug nanoparticles loaded with irinotecan for combination osteosarcoma therapy. Nanotechnology 31 (45), 455101. doi:10.1088/1361-6528/aba783

Liang, S., Yegambaram, M., Wang, T., Wang, J., Black, S. M., and Tang, H. (2022). Mitochondrial metabolism, redox, and calcium homeostasis in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Biomedicines 10 (2), 341. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10020341

Liu, J., Yu, W., Liu, Y., Chen, S., Huang, Y., Li, X., et al. (2016). Mechanical stretching stimulates collagen synthesis via down-regulating SO2/AAT1 pathway. Sci. Rep. 6, 21112. doi:10.1038/srep21112

Liu, X., Zhang, S., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Song, J., Sun, C., et al. (2021). Endothelial cell-derived SO2 controls endothelial cell inflammation, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and collagen synthesis to inhibit hypoxic pulmonary vascular remodelling. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 5577634. doi:10.1155/2021/5577634

Luo, L., Chen, S., Jin, H., Tang, C., and Du, J. (2011). Endogenous generation of sulfur dioxide in rat tissues. Biochem. biophysical Res. Commun. 415 (1), 61–67. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.012

Luo, L., Hong, X., Diao, B., Chen, S., and Hei, M. (2018). Sulfur dioxide attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arteriolar remodeling via Dkk1/Wnt signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 106, 692–698. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.017

Luo, L., Liu, D., Tang, C., Du, J., Liu, A. D., Holmberg, L., et al. (2013). Sulfur dioxide upregulates the inhibited endogenous hydrogen sulfide pathway in rats with pulmonary hypertension induced by high pulmonary blood flow. Biochem. biophysical Res. Commun. 433 (4), 519–525. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.014

Mandras, S. A., Mehta, H. S., and Vaidya, A. (2020). Pulmonary hypertension: a brief guide for clinicians. Mayo Clin. Proc. 95 (9), 1978–1988. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.039

Milara, J., Roger, I., Montero, P., Artigues, E., Escrivá, J., and Cortijo, J. (2022). IL-11 system participates in pulmonary artery remodeling and hypertension in pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 23 (1), 313. doi:10.1186/s12931-022-02241-0

Mitsuhashi, H., Yamashita, S., Ikeuchi, H., Kuroiwa, T., Kaneko, Y., Hiromura, K., et al. (2005). Oxidative stress-dependent conversion of hydrogen sulfide to sulfite by activated neutrophils. Shock (Augusta, Ga) 24 (6), 529–534. doi:10.1097/01.shk.0000183393.83272.de

Oeckinghaus, A., Hayden, M. S., and Ghosh, S. (2011). Crosstalk in NF-κB signaling pathways. Nat. Immunol. 12 (8), 695–708. doi:10.1038/ni.2065

Recasens, M., Benezra, R., Basset, P., and Mandel, P. (1980). Cysteine sulfinate aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase isoenzymes of rat brain. Purification, characterization, and further evidence for identity. Biochemistry 19 (20), 4583–4589. doi:10.1021/bi00561a007

Recasens, M., and Delaunoy, J. P. (1981). Immunological properties and immunohistochemical localization of cysteine sulfinate or aspartate aminotransferase-isoenzymes in rat CNS. Brain Res. 205 (2), 351–361. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(81)90345-0

Shah, A. J., Beckmann, T., Vorla, M., and Kalra, D. K. (2023). New drugs and therapies in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (6), 5850. doi:10.3390/ijms24065850

Shi, X., Gao, Y., Song, L., Zhao, P., Zhang, Y., Ding, Y., et al. (2020). Sulfur dioxide derivatives produce antidepressant- and anxiolytic-like effects in mice. Neuropharmacology 176, 108252. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108252

Simonneau, G., Montani, D., Celermajer, D. S., Denton, C. P., Gatzoulis, M. A., Krowka, M., et al. (2019). Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 53 (1), 1801913. doi:10.1183/13993003.01913-2018

Singer, T. P., and Kearney, E. B. (1956). Intermediary metabolism of L-cysteinesulfinic acid in animal tissues. Archives Biochem. biophysics 61 (2), 397–409. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(56)90363-0

Song, Y., Peng, H., Bu, D., Ding, X., Yang, F., Zhu, Z., et al. (2020). Corrigendum to "Negative auto-regulation of sulfur dioxide generation in vascular endothelial cells: AAT1 S-sulfenylation" [Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 525 (1) (2020) 231-237]. Biochem. biophysical Res. Commun. 526, 1177–1178. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.04.015

Song, Y., Song, J., Zhu, Z., Peng, H., Ding, X., Yang, F., et al. (2021). Compensatory role of endogenous sulfur dioxide in nitric oxide deficiency-induced hypertension. Redox Biol. 48, 102192. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2021.102192

Stenmark, K. R., Fagan, K. A., and Frid, M. G. (2006). Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Circulation Res. 99 (7), 675–691. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000243584.45145.3f

Stipanuk, M. H. (2020). Metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids: how the body copes with excess methionine, cysteine, and sulfide. J. Nutr. 150 (1), 2494S–505s. doi:10.1093/jn/nxaa094

Sun, Y., Tang, C., Jin, H., and Du, J. (2022). Implications of hydrogen sulfide in development of pulmonary hypertension. Biomolecules 12 (6), 772. doi:10.3390/biom12060772

Sun, Y., Tian, Y., Prabha, M., Liu, D., Chen, S., Zhang, R., et al. (2010). Effects of sulfur dioxide on hypoxic pulmonary vascular structural remodeling. Laboratory investigation; a J. Tech. methods pathology 90 (1), 68–82. doi:10.1038/labinvest.2009.102

Tian, X., Zhang, Q., Huang, Y., Chen, S., Tang, C., Sun, Y., et al. (2020). Endothelin-1 downregulates sulfur dioxide/aspartate aminotransferase pathway via reactive oxygen species to promote the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 9367673. doi:10.1155/2020/9367673

Tian, Y., Tang, X. Y., Jin, H. F., Tang, C. S., and Du, J. B. (2008). Effect of sulfur dioxide on pulmonary vascular structure of hypoxic pulmonary hypertensive rats. Zhonghua er ke za zhi = Chin. J. Pediatr. 46 (9), 675–679. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2008.09.110

Tinajero, M. G., and Gotlieb, A. I. (2020). Recent developments in vascular adventitial pathobiology: the dynamic adventitia as a complex regulator of vascular disease. Am. J. pathology 190 (3), 520–534. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.10.021

Turhan, K., Alan, E., Yetik-Anacak, G., and Sevin, G. (2022). H2S releasing sodium sulfide protects against pulmonary hypertension by improving vascular responses in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 931, 175182. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.175182

Veith, C., Vartürk-Özcan, I., Wujak, M., Hadzic, S., Wu, C. Y., Knoepp, F., et al. (2022). SPARC, a novel regulator of vascular cell function in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 145 (12), 916–933. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057001

Wang, W., and Wang, B. (2018). SO2 donors and prodrugs, and their possible applications: a review. Front. Chem. 6, 559. doi:10.3389/fchem.2018.00559

Yagi, T., Kagamiyama, H., and Nozaki, M. (1979). Cysteine sulfinate transamination activity of aspartate aminotransferases. Biochem. biophysical Res. Commun. 90 (2), 447–452. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(79)91255-5

Yamaguchi, K., Sakakibara, S., Asamizu, J., and Ueda, I. (1973). Induction and activation of cysteine oxidase of rat liver. II. The measurement of cysteine metabolism in vivo and the activation of in vivo activity of cysteine oxidase. Biochimica biophysica acta 297 (1), 48–59. doi:10.1016/0304-4165(73)90048-2

Yang, R., Yang, Y., Dong, X., Wu, X., and Wei, Y. (2014). Correlation between endogenous sulfur dioxide and homocysteine in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Zhonghua er ke za zhi = Chin. J. Pediatr. 52 (8), 625–629. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2014.08.016

Yu, B., Ichinose, F., Bloch, D. B., and Zapol, W. M. (2019). Inhaled nitric oxide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 176 (2), 246–255. doi:10.1111/bph.14512

Yu, B., Yuan, Z., Yang, X., and Wang, B. (2020). Prodrugs of persulfides, sulfur dioxide, and carbon disulfide: important tools for studying sulfur signaling at various oxidation states. Antioxidants redox Signal. 33 (14), 1046–1059. doi:10.1089/ars.2019.7880

Yu, W., Liu, D., Liang, C., Ochs, T., Chen, S., Chen, S., et al. (2016). Sulfur dioxide protects against collagen accumulation in pulmonary artery in association with downregulation of the transforming growth factor β1/smad pathway in pulmonary hypertensive rats. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5 (10), e003910. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.003910

Zhang, D., Wang, X., Tian, X., Zhang, L., Yang, G., Tao, Y., et al. (2018). The increased endogenous sulfur dioxide acts as a compensatory mechanism for the downregulated endogenous hydrogen sulfide pathway in the endothelial cell inflammation. Front. Immunol. 9, 882. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00882

Zhang, H., Huang, Y., Bu, D., Chen, S., Tang, C., Wang, G., et al. (2016). Endogenous sulfur dioxide is a novel adipocyte-derived inflammatory inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 6, 27026. doi:10.1038/srep27026

Zhang, L., Jin, H., Song, Y., Chen, S. Y., Wang, Y., Sun, Y., et al. (2021). Endogenous sulfur dioxide is a novel inhibitor of hypoxia-induced mast cell degranulation. J. Adv. Res. 29, 55–65. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2020.08.017

Zhang, Q., Lenardo, M. J., and Baltimore, D. (2017). 30 Years of NF-κB: a blossoming of relevance to human pathobiology. Cell. 168 (1-2), 37–57. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.012

Zhang, Y., Hernandez, M., Gower, J., Winicki, N., Morataya, X., Alvarez, S., et al. (2022). JAGGED-NOTCH3 signaling in vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci. Transl. Med. 14 (643), eabl5471. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abl5471

Zhou, W., Liu, K., Zeng, L., He, J., Gao, X., Gu, X., et al. (2022). Targeting VEGF-A/VEGFR2 Y949 signaling-mediated vascular permeability alleviates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 146 (24), 1855–1881. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061900

Zhu, Y., Shu, D., Gong, X., Lu, M., Feng, Q., Zeng, X. B., et al. (2022). Platelet-derived TGF (transforming growth factor)-β1 enhances the aerobic glycolysis of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells by PKM2 (pyruvate kinase muscle isoform 2) upregulation. Hypertens. (Dallas, Tex 1979) 79 (5), 932–945. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18684

Zhu, Z., Zhang, L., Chen, Q., Li, K., Yu, X., Tang, C., et al. (2020). Macrophage-derived sulfur dioxide is a novel inflammation regulator. Biochem. biophysical Res. Commun. 524 (4), 916–922. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.02.013

Keywords: pulmonary hypertension, sulfur dioxide, aspartate transaminase, pulmonary vascular remodeling, gaseous signaling molecule

Citation: Liu X, Zhou H, Zhang H, Jin H and He Y (2023) Advances in the research of sulfur dioxide and pulmonary hypertension. Front. Pharmacol. 14:1282403. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1282403

Received: 24 August 2023; Accepted: 02 October 2023;

Published: 12 October 2023.

Edited by:

Mahmoud El-Mas, Alexandria University, EgyptReviewed by:

Yuqin Chen, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, ChinaPatrick Crosswhite, Gonzaga University, United States

Yunbin Xiao, Hunan Children’s Hospital, China

Copyright © 2023 Liu, Zhou, Zhang, Jin and He. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongfang Jin, amluaG9uZ2Zhbmc1MUAxMjYuY29t; Yan He, aHliaWNxQHFxLmNvbQ==

Xin Liu

Xin Liu He Zhou

He Zhou Hongsheng Zhang1

Hongsheng Zhang1 Hongfang Jin

Hongfang Jin