95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol. , 17 October 2023

Sec. Ethnopharmacology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1230604

This article is part of the Research Topic Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics of Interactions Between Herbal and Clinically Used Medicines View all 4 articles

Objectives: Chronic cough is a frequent condition worldwide that significantly impairs quality of life. Herbal medicine (HM) has been used to treat chronic cough due to the limited effectiveness of conventional medications. This study aimed to summarize and determine the effects of HM on patients with chronic cough.

Methods: A comprehensive search of 11 databases was conducted to find randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) that reported the effects of HM for patients with chronic cough on 16 March 2023. The primary outcome was cough severity, and the secondary outcomes included cough-related quality of life, cough frequency, total effective rate (TER), and cough recurrence rate. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, and the certainty of the evidence for effect estimates was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations tool.

Results: A total of 80 RCTs comprising 7,573 patients were included. When HM was used as an alternative therapy to conventional medication, there were inconsistent results in improving cough severity. However, HM significantly improved cough-related quality of life and TER and significantly lowered the cough recurrence rate compared with conventional medication. When used as an add-on therapy to conventional medication, HM significantly improved cough severity, cough-related quality of life, and TER and significantly lowered the recurrence rate. In addition, HM had a significantly lower incidence of adverse events when used as an add-on or alternative therapy to conventional medication. The subgroup analysis according to age and cause of cough also showed a statistically consistent correlation with the overall results. The certainty of the evidence for the effect of HM was generally moderate to low due to the risk of bias in the included studies.

Conclusion: HM may improve cough severity and cough-related quality of life, and lower the cough recurrence rate and incidence of adverse events in patients with chronic cough. However, due to the high risk of bias and clinical heterogeneity of the included studies, further high-quality placebo-controlled clinical trials should be conducted using a validated and objective assessment tool.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023418736, CRD42023418736.

Chronic cough refers to a cough lasting more than 8 weeks in adults and children over the age of 15 or more than 4 weeks in children under the age of 15 (Chang and Glomb, 2006; Irwin et al., 2006). Chronic cough is a common problem that affects 10% of the general population worldwide (Song et al., 2015), and chronic cough imposes a severe socio-economic burden by directly impacting the quality of life and decreasing productivity (Won et al., 2020; Kubo et al., 2021). The most common causes of chronic cough are upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), asthma, cough variant asthma (CVA), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and eosinophilic bronchitis. Empirical treatments based on common causes through taking the medical history and physical examination have been conducted in clinical settings (Perotin et al., 2018; Kaplan, 2019). However, unexplained or refractory chronic cough, which has an unknown etiology after a thorough investigation and therapeutic trials of common cough-trigger conditions, has been reported in nearly half of all cases of chronic cough (Gibson et al., 2016). Nonspecific chronic cough with no history, symptoms, signs, or laboratory findings is also common (Song et al., 2018). In addition, according to a survey study, a suggested diagnosis for the cough was given in only 53% of the 1,120 patients suffering from chronic cough, and more than 90% reported limited or no effectiveness of conventional medications (Chamberlain et al., 2015).

East Asian traditional medicine (EATM), including herbal medicine (HM), has frequently been used by patients with chronic cough who were difficult to diagnose or were not effectively treated with conventional medication. HM especially has the potential to be a treatment for nonspecific or unexplained chronic cough as well as specific coughs based on the characteristics of multi-components and multi-targets (Wang et al., 2012). Accordingly, clinical trials to evaluate the effects of specific HMs on nonspecific chronic cough are being conducted (Kim et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2023). Although the effects of HM were previously summarized through systematic reviews, these were mainly limited to common causes of chronic cough, such as CVA and UACS (Jiang et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2021). To the best of our knowledge, no study has systematically summarized the effects of HM on chronic cough regardless of the causative disease. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the certainty of evidence by comprehensively synthesizing the effects of HM on chronic cough, regardless of the causative disease and age, to aid the decision-making of clinicians, patients, researchers, and policymakers.

The protocol of this systematic review was registered to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (identifying number: CRD42023418736; registration date: 30 April 2023). There were no deviations from the protocol.

1) Study design: Only parallel-group randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) published in journals were included.

2) Population: Studies involving populations with chronic cough lasting longer than 8 weeks in adults (≥15 years old) or 4 weeks in children (<15 years old) were included (Chang and Glomb, 2006; Irwin et al., 2006), regardless of age, sex, race, and nationality. Studies not describing the cough period were excluded since whether the study met the definition of chronic cough could not be determined.

3) Treatment intervention: Studies using oral HM based on the EATM theory as a monotherapy or add-on therapy to conventional medication for chronic cough were included as a treatment intervention. Studies in which the composition of botanical drugs in HM was not specified were excluded. Conventional medications for chronic cough in this review included any medication used for treating chronic cough in the included studies, such as antitussive expectorants, bronchodilators, and codeine phosphate.

4) Control intervention: Only conventional medication, waitlist, and placebo HM were eligible as a control intervention. Studies using EATM therapies such as HM, acupuncture, and moxibustion as a control intervention were excluded.

5) Outcomes: Only studies reporting at least one of the following primary and secondary outcomes were included. The primary outcome was post-treatment cough severity, measured by methods such as the cough symptom score (CSS), cough visual analog scale (VAS), or simplified cough score (SCS) (Wang et al., 2019). The secondary outcomes included 1) post-treatment cough-related quality of life, measured by methods such as the Leicester cough questionnaire (LCQ), 2) post-treatment cough frequency, 3) total effective rate (TER) based on cough symptom improvement, 4) cough recurrence rate, and 5) incidence of adverse events during the trial period.

6) Others: There were no publication language restrictions.

The following 11 electronic databases were searched for published studies on 16 March 2023: Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang data, Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System, Korean Medical Database, ScienceON, Research Information Sharing Service, and Citation Information by National Institute of Informatics. Reference lists of relevant articles and trial registries, such as ClinicalTrials.gov, were reviewed to identify eligible studies. Search strategies were consulted with experts in respiratory medicine and systematic reviews. The search strategies for all the databases are described in Supplementary Material S1.

The study selection process was independently performed by two authors (BL. and C-YK), and data extraction was independently performed by four authors (BL, C-YK, H-WS, and YK). Any disagreements between them were resolved by discussions with other researchers.

The bibliographic information of the studies identified from the databases or other sources was imported into EndNote 20 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, United States), and the titles and abstracts were reviewed after removing any duplicate studies. Full texts were searched for eligible studies, and the final included studies were confirmed after reviewing the retrieved studies. For the final included studies, the following data were extracted using a pilot-tested Excel form (Excel 365, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States): study characteristics (first author, publication year, publication language, the country where the study was conducted, study setting, and funding source), population (sample size, mean age and cough period, and pattern identification), details of HM (name, dosage form, composition, manufacturing company, and administration period), control intervention, the outcome of interest, results, and adverse events.

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed by Cochrane’s risk of bias tool (Higgins et al., 2011). The risk of selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other biases in the individual studies were rated as “low,” “unclear,” or “high.” Other bias items were evaluated based on statistical or clinical heterogeneity of the baseline characteristics between the treatment and control groups.

All of the included studies were qualitatively analyzed. In cases where at least two studies used the same treatment and control intervention and had the same outcome measure, a meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager software, version 5.4 (Cochrane, London, UK). Continuous data are presented using the mean differences (MDs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), while categorical data are presented using the risk ratio (RR) with their 95% CIs.

Heterogeneity between the studies in terms of effect measures was assessed using the I2 statistic, which expresses the proportion of variability in a meta-analysis that is explained by between-trial heterogeneity rather than by sampling error. The I2 values were calculated as (Q—df)/Q × 100%, where Q is the Cochran’s homogeneity test statistic, and df is the degrees of freedom (the number of trials minus 1) (Higgins and Thompson, 2002; Thorlund et al., 2012). We considered I2 values greater than 50% and 75% to be indicative of substantial and high heterogeneity, respectively. Considering the unavoidable clinical heterogeneity of the HM intervention, such as that caused by botanical drugs content, dose, and administration period, between the included studies, the results were pooled using a random-effect model, which assumes that the true effect could vary from study to study due to the differences among studies (Borenstein et al., 2010).

To interpret the heterogeneity in the meta-analysis results if there was more than one study included in each subgroup, subgroup analyses were conducted according to the age of the participants (children, adults, and both) and the cause of the cough. Through subgroup analysis, the changes in I2 values and consistency with the overall meta-analysis results were examined. To identify the robustness of the meta-analysis result, sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding studies with high risks of bias or outliers. In cases where there were a sufficient number of studies (≥10) included in the meta-analysis, the evidence of publication bias was assessed by the symmetry of the funnel plot and Egger’s test.

The certainty of the evidence for the meta-analysis findings was assessed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Balshem et al., 2011). To evaluate the certainty of the evidence, the risk of bias of the studies included in the analysis; the indirectness, inconsistency, and imprecision of the effect estimate; and the risk of publication bias were evaluated. For each finding, the certainty of the evidence was rated as “High,” “Moderate,” “Low,” or “Very low."

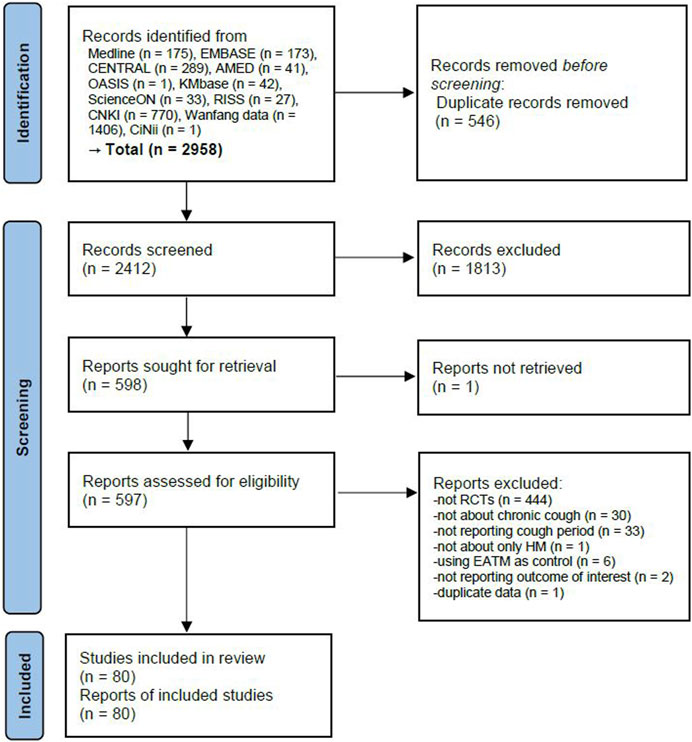

A total of 2,958 articles were identified through the database search. After removing 546 duplicate articles, 1813 articles were excluded through the title and abstract review. As a result, 597 studies underwent full-text review, except for one study where the full text was not retrieved. After the full-text review, 517 studies were excluded for the following reasons: not an RCT (n = 444), not about chronic cough (n = 30), not reporting cough period (n = 33), not about HM (n = 1), using EATM as the control group intervention (n = 6), not reporting the outcome of interest (n = 2), and duplicate data (n = 1) (Supplementary Material S2). Finally, a total of 80 studies involving 7,573 participants were included in this review (Han et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2010; Zhou, 2011; Deng, 2012; Liu and Zhang, 2012; Wang, 2012; Xie et al., 2012; Yang and Yang, 2012; Zhu, 2012; Gan and Zhu, 2013; Lu et al., 2013; Chen, 2014; Cui, 2014; Lin, 2014; Lu and Pan, 2014; Yu et al., 2014; Chen, 2016; Cui et al., 2016; Wang and Zang, 2016; Wang and Zhou, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Fan, 2017; Gao et al., 2017; Ge et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017; Xie, 2017; Xu, 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Zhu, 2017; Li, 2018; Yan et al., 2018; Zhou, 2018; Chen et al., 2019; Li, 2019; Shen and Huang, 2019; Wang and Li, 2019; Wu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019; Gu, 2020; Hui and Dong, 2020; Lai, 2020; Li, 2020; Liu, 2020; Meng et al., 2020; Niu et al., 2020; Sun and Wei, 2020; Tan and Zheng, 2020; Tang et al., 2020; Wang, 2020; Wu and Li, 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Yi and Zheng, 2020; Zhang and Chen, 2020; Zhang H. et al., 2021; Chen, 2021; Chen and Chen, 2021; Diao, 2021; He, 2021; Huang, 2021; Li et al., 2021; Luan et al., 2021; Xia, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Zhao L. et al., 2022; Zhao Y. et al., 2022; Gong, 2022; Guan, 2022; Ji, 2022; Li et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2022; Liu, 2022; Lyu et al., 2022; Song, 2022; Wang and Xu, 2022; Yang et al., 2022; Zhang and Wang, 2022; Zhao and Tuo, 2022; Zhou et al., 2022; Tian, 2023) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. EATM, East Asian traditional medicine; HM, herbal medicine; RCT, randomized controlled clinical trial.

One study was conducted in Korea and published in English (Lyu et al., 2022); the others were conducted in China and published in Chinese. The study setting of one study was a family planning service station (Wang and Zhou, 2016), and the remaining settings were clinics. A total of 21 studies reported funding sources (Shi et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2013; Lu and Pan, 2014; Chen, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2017; Ge et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019; Meng et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2020; Wang, 2020; Wu and Li, 2020; Zhang and Chen, 2020; Zhang H. et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Lyu et al., 2022; Zhang and Wang, 2022; Zhao and Tuo, 2022). A total of 27 studies were conducted on children (Chen et al., 2009; Zhou, 2011; Liu and Zhang, 2012; Yu et al., 2014; Chen, 2016; Cui et al., 2016; Ge et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Li, 2018; Yan et al., 2018; Li, 2019; Shen and Huang, 2019; Niu et al., 2020; Wang, 2020; Zhang and Chen, 2020; Chen and Chen, 2021; Diao, 2021; He, 2021; Li et al., 2021; Luan et al., 2021; Zhao L. et al., 2022; Gong, 2022; Li et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022; Zhao and Tuo, 2022; Tian, 2023), 3 studies included both children and adults (Zhang et al., 2016; Fan, 2017; Wu and Li, 2020), and the remaining 50 studies were conducted on adults. Only 30 studies (37.5%) described a cause for the cough, including post-respiratory infection in 5 studies (Zhou, 2011; Li, 2019; Shen and Huang, 2019; Niu et al., 2020; Diao, 2021); GERD (Deng, 2012; Gao et al., 2017; Lyu et al., 2022), UACS (Chen et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2019; Luan et al., 2021), and unexplained chronic cough (Wang, 2012; Chen, 2014; Zhang et al., 2016) in 3 studies each; and chronic bronchitis (Song, 2022), CVA (Cui et al., 2016), and nonspecific chronic chough (Chen and Chen, 2021) in 1 study each. There were also 13 studies targeting a mixed population, including patients with various causes of the cough (Han et al., 2008; Cui, 2014; Lu and Pan, 2014; Yu et al., 2014; Chen, 2016; Xu, 2017; Zhu, 2017; Lai, 2020; Wang, 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Yi and Zheng, 2020; Li et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). One study was a 3-arm RCT comparing HM plus conventional medication, HM, and conventional medication (Zhang et al., 2016). The remaining studies were 2-arm RCTs, 33 comparing HM and conventional medication (Han et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2010; Deng, 2012; Liu and Zhang, 2012; Wang, 2012; Xie et al., 2012; Yang and Yang, 2012; Zhu, 2012; Lu et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2014; Fan, 2017; Xie, 2017; Zhu, 2017; Li, 2018; Wang and Li, 2019; Gu, 2020; Hui and Dong, 2020; Lai, 2020; Li, 2020; Liu, 2020; Meng et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2020; Wu and Li, 2020; Yi and Zheng, 2020; Zhang H. et al., 2021; Chen, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Liang et al., 2022; Liu, 2022; Lyu et al., 2022; Wang and Xu, 2022; Yang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022), 1 comparing HM and placebo HM (Lyu et al., 2022), and the rest comparing HM plus conventional medication and conventional medication alone (Supplementary Material S3).

In the included studies, various HMs were used, and among them, Zhisou-san or its modified form was used the most frequently (13 studies) (Liu and Zhang, 2012; Chen, 2016; Cui et al., 2016; Li, 2018; Zhou, 2018; Gu, 2020; Lai, 2020; Niu et al., 2020; Huang, 2021; Guan, 2022; Song, 2022; Wang and Xu, 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). A total of 154 botanical drugs were used, and as a result of analyzing the constituent botanical drugs of basic HM, four studies were excluded that used different prescriptions according to the pattern identification (Chen et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2014; Hui and Dong, 2020; Tang et al., 2020). Among them, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. [Fabaceae; Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma] was used the most (61 studies), followed by Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. [Campanulaceae; Platycodonis Radix] (41 studies), Aster tataricus L.f. [Asteraceae; Asteris Radix et Rhizoma] (36 studies), Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino [Araceae; Pinelliae Tuber] (29 studies), Citrus × aurantium f. deliciosa (Ten.) M. Hiroe [Rutaceae; Citri Unshius Pericarpium] (28 studies), Prunus armeniaca L. [Rosaceae; Armeniacae Semen] (27 studies), Poria cocos Wolf [Polyporaceae; Poria Sclerotium] (24 studies), Stemona tuberosa Lour. [Stemonaceae; Stemonae Radix] (22 studies), and Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. [Schisandraceae; Schisandrae Fructus] (20 studies). As for the dosage of HMs, decoction was the most common (68 studies), followed by granule (5 studies) and oral liquid (3 studies). The HM administration duration varied from 1 week to 3 months, with 2 weeks being the most (34 studies), followed by 4 weeks (13 studies), 1 month (9 studies), and 1 week (7 studies). Twelve studies performed follow-ups after the end of the HM administration, and the follow-up period varied from 1 week to 1 year (Supplementary Material S4).

All the studies appropriately generated random sequences using random number tables or dice-throwing methods, and none of the studies mentioned allocation concealment. Except for one study comparing HM and placebo HM (Lyu et al., 2022), no study conducted blinding of the participants and personnel. In addition, only two studies blinded the outcome assessors (Lu et al., 2013; Lyu et al., 2022). Four studies were evaluated as having a high risk of attrition bias by a per-protocol analysis (Chen et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2022; Zhao and Tuo, 2022). All the studies were rated as having a low risk of reporting bias and other biases (Supplementary Material S5).

1) Primary outcome: cough severity

Although there was no significant difference in the SCS total score between the two groups (MD -0.07, 95% CI −0.31 to 0.18, I2 = 0%), each daytime (MD −0.34, 95% CI −0.59 to −0.08, I2 = 91%) or nighttime SCS score (MD −0.38, 95% CI -0.58 to −0.19, I2 = 86%) significantly decreased in the HM group compared with the conventional medication group (Table 1).

2) Secondary outcomes

Cough-related quality of life, assessed by the LCQ total score, and physical, psychological, and social sub-items, were significantly increased after the treatment in the HM group compared with the conventional medication group (total: MD 2.32, 95% CI 0.04 to 4.61, I2 = 96%; physical items: MD 0.63, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.95, I2 = 75%; psychological items: MD 0.58, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.87, I2 = 71%; social items: MD 0.66, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.18, I2 = 88%). In addition, the TER, calculated according to the cough symptom improvement, was significantly higher in the HM group compared with the conventional medication group (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.29, I2 = 35%), regardless of subgroup according to age. The funnel plot for the TER was asymmetric, and the result of the Egger’s test also suggested the risk of publication bias with a p-value of less than 0.05 (Supplementary Material S6). Cough recurrence rate was significantly lower in the HM group (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.51, I2 = 0%) (Table 1).

Eighteen studies comparing HM and conventional medication reported the incidence of adverse events (Han et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2016; Gu, 2020; Hui and Dong, 2020; Lai, 2020; Liu, 2020; Meng et al., 2020; Wu and Li, 2020; Yi and Zheng, 2020; Zhang H. et al., 2021; Chen, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Liang et al., 2022; Wang and Xu, 2022; Yang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). The incidence of adverse events was significantly lower in the HM group compared with the conventional medication group (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.40, I2 = 0%). The funnel plot was symmetric, and the p-value of the Egger’s test was 0.917, suggesting that the risk of publication was low (Supplementary Material S6). When analyzing subgroups according to age, insignificant results were shown between the two groups in children, but adverse events were significantly lower in the HM group in adults and mixed populations (Table 1).

1) Primary outcome: cough severity

Cough severity, evaluated by SCS daytime and nighttime scores, was significantly lower in the HM plus conventional medication group (SCS daytime: MD −0.53, 95% CI −0.67 to −0.39, I2 = 97%; SCS nighttime: MD −0.55, 95% CI −0.69 to −0.41, I2 = 95%), which was consistent with subgroup analyses according to age and cause of cough. In addition, cough severity, assessed by the 0–100 mm cough VAS, also significantly improved in the HM plus conventional medication group (MD −11.69, 95% CI −21.71 to −1.67, I2 = 98%) (Table 1).

2) Secondary outcomes

Cough-related quality of life, assessed by the LCQ, was significantly improved in the HM plus conventional medication group compared with conventional medication alone (physical items: MD 0.88, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.05, I2 = 0%; psychological items: MD 0.62, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.77, I2 = 0%; social items: MD 0.81, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.17, I2 = 71%), and these results were consistent in the subgroup analysis according to age. One study targeted adults with chronic cough due to GERD (Gao et al., 2017). When HM was additionally administered with conventional medication (rabeprazole and mosapride citrate) for 8 weeks, cough severity and quality of life, assessed by the chronic cough impact scale, were significantly improved compared to conventional medication alone (p < 0.01). One study targeted pediatric patients with chronic cough due to UACS (Luan et al., 2021). When HM was additionally administered with conventional medication (budesonide nasal spray) for 12 weeks, cough frequency per day was significantly improved compared to conventional medication alone (p < 0.05).

The TER, according to the cough symptom improvement, was significantly higher in the HM plus conventional medication group (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.21, I2 = 0%). The funnel plot for the TER was asymmetric, and the result of Egger’s test also suggested the risk of publication bias with a p-value of less than 0.05 (Supplementary Material S6). The cough symptom recurrent rate was significantly lower in the HM plus conventional medication group (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.46, I2 = 0%), and the statistical significance was consistent when conducting a subgroup analysis according to age (Table 1).

Seventeen studies comparing HM plus conventional medication and conventional medication alone reported the incidence of adverse events (Chen, 2014; Cui, 2014; Zhang et al., 2016; Ge et al., 2017; Zhou, 2018; Li, 2019; Shen and Huang, 2019; Wu et al., 2019; Tan and Zheng, 2020; Wang, 2020; Chen and Chen, 2021; Li et al., 2021; Luan et al., 2021; Guan, 2022; Li et al., 2022; Song, 2022; Zhang and Wang, 2022), and it was found that adverse events were significantly lower in the HM plus conventional medication group (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.87, I2 = 50%) (Table 1). The funnel plot was symmetric, and the p-value of Egger’s test was 0.433, suggesting the risk of publication was low (Supplementary Material S6).

Only one study compared HM versus placebo HM (Lyu et al., 2022), and therefore, a meta-analysis was not possible. In the study, HM significantly improved cough severity, measured by the cough diary score and cough VAS, and cough-related quality of life, measured by LCQ, compared with the baseline. HM significantly improved daytime and total cough diary score compared to the placebo HM.

The certainty of the evidence for all meta-analysis outcomes comparing HM to conventional medication was moderate to low. The main reason for downgrading was the risk of bias of the included studies, inconsistency, imprecision, and publication bias. The certainty of the evidence for cough severity and cough-related quality of life when comparing HM plus conventional medication and conventional medication alone was moderate, downgraded by the risk of bias of the included studies. In this comparison group, the certainty of the evidence for TER and cough recurrence rate was low, and the certainty of the evidence for adverse event rates was very low (Table 1).

To summarize the effect of HM on chronic cough, 11 databases were comprehensively searched, and a total of 80 relevant articles were included in this meta-analysis. Previous systematic reviews of the effect of HM on chronic cough were conducted on specific causes of chronic cough, such as adult CVA (Chen et al., 2021) or UACS patients (Jiang et al., 2016). A study also synthesized relevant studies on HM up to 2012 without distinction of acute or chronic cough (Wagner et al., 2015). Our study differs from these previous studies in that it updated the effect of HM on chronic cough regardless of the cause of the cough or age.

According to our findings, when HM was used as a monotherapy, there were inconsistent results across rating scales for cough severity. However, compared to conventional medication, HM significantly improved cough-related quality of life and TER and significantly lowered the cough recurrence rate. The certainty of the evidence was mainly low. When HM was used as an add-on therapy with conventional medication, the combination of therapies significantly improved cough severity, cough-related quality of life, and TER and significantly lowered the cough recurrence rate compared to conventional medication alone. The certainty of the evidence was mainly moderate. A subgroup analysis according to age and cause of cough also showed a statistically consistent direction with the overall results. However, only a small number of studies reported the cause of cough. In addition, the HM group had a significantly lower incidence of adverse events than the conventional medication group when HM was used as an add-on or monotherapy.

Cough frequency, one of our secondary outcomes, was evaluated as the number of coughs per day in only one study (Luan et al., 2021), and how the number of coughs was counted was not reported; however, cough frequency significantly improved in the HM group. A cough frequency meter is an objective standard evaluation method of coughing, and a representative example is the Leicester cough monitor (Morice et al., 2007). The correlation between cough frequency using an objective cough frequency meter and subjective cough-related quality of life LCQ scores was reported to be moderate (Birring et al., 2006), suggesting that there is a difference between perceived and actual cough frequency. Therefore, in future clinical trials to evaluate the effect of HM on coughing, subjective questionnaires, and tools to evaluate cough frequency objectively should be used to confirm the effect of HM on actual cough frequency.

Chronic cough has a variety of causes, and more than one disease can cause a complex effect inducing cough. In many cases, there is no specific symptom besides coughing or a definitive test method (Morice et al., 2020). Therefore, many nonspecific chronic coughs are difficult to treat by identifying the cause of the disease in the clinical setting, so empirical treatment is often performed first (Morice et al., 2020). In addition, it has been reported that 10%–40% of patients with chronic cough who visit secondary or tertiary medical institutions have an unexplained cough that does not resolve well despite the best diagnostic tests and treatment efforts (McGarvey, 2013). Accordingly, there is a need for an effective treatment approach for chronic cough that exhibits complex pathophysiology rather than simply a symptom of another disease. We attempted a subgroup analysis of the effect of HM according to the cause of the cough; however, 50 studies (62.5% of the included studies) did not report the cause of the cough. In addition, there was only one study on nonspecific chronic cough and three on unexplained chronic cough. Due to its multi-component and multi-target characteristics, HM has the potential to act effectively on chronic cough from various causes or nonspecific or unexplained chronic coughs. In particular, the effect of Maekmundong-tang (Maimendong-tang in Chinese), one of the HM, on cough hypersensitivity accompanied by chronic cough has been reported through clinical studies (Watanabe et al., 2003; Watanabe et al., 2004). An RCT is also being attempted to explore the effects of Maekmundong-tang on nonspecific chronic cough (Lee et al., 2023). Therefore, in clinical studies evaluating the effect of HM on chronic cough in the future, the cause of the cough should be reported if known, or it should be specified as an explained or nonspecific chronic cough based on the definition in the guideline (Gibson et al., 2016; Song et al., 2018). This specification will also help to explore the therapeutic mechanism of HM for the treatment of cough.

The therapeutic mechanism of HM on chronic cough has been proposed in various ways. Among the included studies, Zhisou-san, or its modified form, was used most frequently, which was reported to be related to inflammation and Th17/Treg immune balance regulation for the treatment of CVA (Guo et al., 2022). In addition, the pulmonary protective effect and antitussive effect of P. grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. [Campanulaceae; Platycodonis Radix] and liquiritin, a flavonoid extracted from G. glabra L. [Fabaceae; Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma], which were used frequently in the included studies, have been reported (Zhang C. et al., 2021; Qin et al., 2022). The antitussive, anti-inflammatory, and expectorant effects of A. tataricus L.f. [Asteraceae; Asteris Radix et Rhizoma] and P. ternata (Thunb.) Makino [Araceae; Pinelliae Tuber] were also reported (Ok et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2015). In addition to the protective effect on the respiratory system, some HMs, including Maekmundong-tang, have been reported to have a therapeutic effect on GERD-induced cough through mechanisms such as relieving airway reflux and hypersensitivity (Lyu et al., 2022). These mechanisms could potentially contribute to the relief of chronic cough caused by GERD. As such, it seems that HM may treat cough due to the synergistic effect of these various botanical drugs, and additional research is needed to derive a clear mechanism.

This study has the following limitations. First, despite attempts at a subgroup analysis according to age and cause of cough, statistical heterogeneity could not be resolved. This difficulty may have been due to clinical heterogeneity, as the included studies used very different types of HM, and the duration of HM administration also varied widely. Second, the risk of bias for the included studies was not optimal, with a particularly high risk of performance and detection bias. There was only one study that evaluated the efficacy of HM compared with placebo HM (Lyu et al., 2022). Therefore, a planned sensitivity analysis excluding studies of low methodological quality was not possible. This also affected the certainty of the evidence, and the certainty of the evidence for the effect of HM was moderate to low.

Nevertheless, this study is the first to comprehensively synthesize the effects of HM regardless of age or cause of cough through a systematic review procedure. In addition, we assessed the risk of publication bias with the symmetry of the funnel plots and Egger’s tests and evaluated the certainty of the evidence with the GRADE method. In the future, clinical trials evaluating the effect of HM should be actively conducted in other countries, such as Korea and Japan, in addition to China, to help generalize and evaluate the effects of HM. In addition, the efficacy of HM compared to placebo HM should be evaluated using a validated and objective assessment tool.

HM as a monotherapy may improve cough severity and cough-related quality of life in patients with chronic cough. In addition, when used as an add-on to conventional medication, HM can significantly improve cough severity and cough-related quality of life. HM as a monotherapy or add-on therapy may lower the cough recurrence rate and incidence of adverse events. However, the certainty of the evidence for the effectiveness of HM was moderate to low due to the risk of bias in the included studies.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conceptualization, BL; methodology, BL and C-YK; formal analysis, BL, C-YK, H-WS, and YK; writing–original draft preparation, BL; writing–review and editing, C-YK, H-WS, YK, K-IK, B-JL, and J-HL; supervision, J-HL; funding acquisition, J-HL. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HF22C0011).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1230604/full#supplementary-material

Balshem, H., Helfand, M., Schünemann, H. J., Oxman, A. D., Kunz, R., Brozek, J., et al. (2011). GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64 (4), 401–406. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015

Birring, S. S., Matos, S., Patel, R. B., Prudon, B., Evans, D. H., and Pavord, I. D. (2006). Cough frequency, cough sensitivity and health status in patients with chronic cough. Respir. Med. 100 (6), 1105–1109. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2005.09.023

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., and Rothstein, H. R. (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1 (2), 97–111. doi:10.1002/jrsm.12

Chamberlain, S. A., Garrod, R., Douiri, A., Masefield, S., Powell, P., Bücher, C., et al. (2015). The impact of chronic cough: a cross-sectional European survey. Lung 193 (3), 401–408. doi:10.1007/s00408-015-9701-2

Chang, A. B., and Glomb, W. B. (2006). Guidelines for evaluating chronic cough in pediatrics: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 129 (1), 260s–283s. doi:10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.260S

Chen, D., and Chen, L. (2021). Clinical effects of the Erchen decoction plus the Xiaoqinglong decoction on chronic cough in children. Clin. J. Chin. Med. 13 (4), 99–101. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-7860.2021.04.035

Chen, H., Cheng, Y., and Yang, L. (2009). Observation on clinical curative effect of integrated traditional Chinese and western medicine in treating chronic cough caused by postnasal drip syndrome in children. Chin. J. Integr. Traditional West. Med. 29 (12), 1135–1136.

Chen, M., Zhou, J., and Wang, Y. (2019). Effect of modified Sanren decoction combined with montelust sodium on chronic cough of type of heat-wetness caused by postnasal drip syndrome and its effect on small airway function and airway hyperresponsiveness. Mod. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 28(33), 3672–3676. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2019.33.006

Chen, Y. B., Shergis, J. L., Wu, Z. H., Guo, X. F., Zhang, A. L., Wu, L., et al. (2021). Herbal Medicine for Adult Patients with Cough Variant Asthma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 5853137. doi:10.1155/2021/5853137

Chen, P. (2014). 58 cases of refractory chronic cough treated with modified Bufei decoction. Jiangxi J. Traditional Chin. Med. 45 (2), 43–44.

Chen, Q. (2016). Clinical observation on 54 cases of children with chronic cough treated with combined therapy of Zhisou san and Western medicine. J. Pediatr. Traditional Chin. Med. 12 (6), 48–51. doi:10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2016.06.17

Chen, X. (2021). Clinical observation on chronic cough treated by Zhisou san combined with modified Sanao decoction. China Health Food (9), 38–39.

Cui, Y., Yu, J., and Zhang, J. (2016). Clinical efficacy analysis of modified Zhisou powder in the treatment of cough variant asthma. China Health Care Nutr. 26 (24), 340–341.

Cui, D. (2014). Breeze Xuan combined western medicine to random parallel control study lung decoction in the treatment of chronic cough. J. Pract. Tradit. Chin. Intern Med. 28 (9), 90–92. doi:10.13729/j.issn.1671-7813.2014.09.43

Deng, J. (2012). Miao medicine combined Zuojin pill treatment of gastroesophageal reflux induced cough randomized control clinical observation. J. Pract. Tradit. Chin. Intern Med. 26 (12), 11–12. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-7813.2012.12(s).06

Diao, M. (2021). Analysis of curative effect of modified Shensu decoction on chronic cough in children with late stage cold. Med. Diet Health 19(5), 26–27.

Fan, Q. (2017). Study on the effect of Zhike Jiangqi decoction in treating 98 cases of chronic cough. J. Clin. Med. Pract. 21 (17), 185–186. doi:10.7619/jcmp.201717066

Gan, Y., and Zhu, L. (2013). Clinical analysis of self-made prescriptions for chronic cough. Med. Forum 17 (22), 2947–2948. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-1721.2013.22.065

Gao, W., Ma, L., Chen, M., Zhong, W., Sun, Q., Li, Y., et al. (2017). Clinical effect of Shumu-Yuntu-Zhike decoction with converntional treatment for the gastroesophageal feflux cough. Int. J. Trad. Chin. Med. 39 (5), 420–423. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4246.2017.05.009

Ge, Y., Li, W., Zhao, Y., and Song, G. (2017). Analysis of efficacy and safety of invigorating-spleen and ventilating-lung therapy combined with budesonide atomized inhalation in the treatment of pediatric chronic cough. World Chin. Med. 12 (8), 1786–1788. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-7202.2017.08.015

Gibson, P., Wang, G., McGarvey, L., Vertigan, A. E., Altman, K. W., and Birring, S. S. (2016). Treatment of Unexplained Chronic Cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 149 (1), 27–44. doi:10.1378/chest.15-1496

Gong, J. (2022). Clinical observation on 40 cases of chronic cough in children with deficiency of lung and spleen qi syndrome adjuvantly treated by modified Shenling Baizhu San combined Yupingfeng San. J. Pediatr. Tradit. Chin. Med. 18 (4), 53–57. doi:10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2022.04.14

Gu, F. (2020). Clinical efficacy of Linggan Wuwei Jiangxin decoction combined with modified Zhisou powder in the treatment of chronic cough. Baojian Wenhui (9), 27–28. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-5217.2020.09.017

Guan, Y. (2022). Clinical observation on Banxia Houpu decoction, modified Zhisou san combined with ambroxol hydrochloride in treating chronic cough. China's Naturop. 30 (17), 90–92. doi:10.19621/j.cnki.11-3555/r.2022.1731

Guo, D. H., Hao, J. P., Li, X. J., Miao, Q., and Zhang, Q. (2022). Exploration in the Mechanism of Zhisou San for the Treatment of Cough Variant Asthma Based on Network Pharmacology. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 1698571. doi:10.1155/2022/1698571

Han, F., Zhang, J., and Liu, M. (2008). 35 cases of chronic cough treated by Manke decoction. Tradit. Chin. Med. Res. 21 (8), 22–24.

He, Y. (2021). Observation on the effect of Bufei Zhike decoction in treating children with chronic cough. Contemp. Med. Symp. 19 (7), 121–123. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-7629.2021.07.073

Higgins, J. P., and Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21 (11), 1539–1558. doi:10.1002/sim.1186

Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., et al. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj 343, d5928. doi:10.1136/bmj.d5928

Huang, S. (2021). Clinical effects of Zhisou powder combined with conventional western medicine in treatment of chronic cough. Med. J. Chin. People's Health 33 (19), 85–87. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-0369.2021.19.029

Hui, L., and Dong, F. (2020). Efficacy and safety of TCM syndrome differentiation in the treatment of chronic cough. Clin. Res. Pract. 5 (23), 152–154. doi:10.19347/j.cnki.2096-1413.202023058

Irwin, R. S., Baumann, M. H., Bolser, D. C., Boulet, L. P., Braman, S. S., Brightling, C. E., et al. (2006). Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 129 (1), 1s–23s. doi:10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S

Ji, T. (2022). Clinical study on Mashe Donghua decoction in the treatment of chronic cough. Guangming J. Chin. Med. 37 (21), 3859–3861. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2022.21.009

Jiang, H., Liu, W., Li, G., Fan, T., and Mao, B. (2016). Chinese Medicinal Herbs in the Treatment of Upper Airway Cough Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Randomized, Controlled Trials. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 22 (3), 38–51.

Kaplan, A. G. (2019). Chronic Cough in Adults: Make the Diagnosis and Make a Difference. Pulm. Ther. 5 (1), 11–21. doi:10.1007/s41030-019-0089-7

Kim, K. I., Shin, S., Kim, K., and Lee, J. (2016). Efficacy and safety of Maekmoondong-tang for chronic dry cough: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 16, 46. doi:10.1186/s12906-016-1028-x

Kubo, T., Tobe, K., Okuyama, K., Kikuchi, M., Chen, Y., Schelfhout, J., et al. (2021). Disease burden and quality of life of patients with chronic cough in Japan: a population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 8 (1). doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000764

Lai, C. (2020). Observation on the effect of Linggan Wuwei Jiangxin decoction combined with modified Zhisou powder in treating chronic cough. Chin J Clin. Ration. Drug Use 13 (14), 52–53. doi:10.15887/j.cnki.13-1389/r.2020.14.028

Lee, B., Park, H. J., Jung, S. Y., Kwon, O. J., Park, Y. C., and Yang, C. (2023). Herbal Medicine Maekmundong-Tang on Patients with Nonspecific Chronic Cough: Study Protocol for a Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20 (5). doi:10.3390/ijerph20054164

Li, J., Lu, H., Shen, F., and Huang, X. (2021). Clinical study on modified Runfei Pingchuan decoction combined with montelukast sodium in the treatment of chronic cough with lung spleen qi deficiency in children. Chin. Archives Traditional Chin. Med. 39 (11), 243–246. doi:10.13193/j.issn.1673-7717.2021.11.058

Li, L., Hu, C., Chen, B., Huang, C., Miao, J., and Chen, F. (2022). Observation on curative effect of bacterial lysate capsule combined with Yupingfeng oral liquid in the treatment of chronic cough in children. Pract. Clin. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 22 (11), 73–75. doi:10.13638/j.issn.1671-4040.2022.11.022

Li, R. (2018). Analysis of 42 cases of infantile chronic cough treated by modification and subtraction of Zhisou powder. Pract. Clin. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 18 (10), 42–44. doi:10.13638/j.issn.1671-4040.2018.10.020

Li, W. (2019). Clinical study on Yangyin Qingfei tang combined with montelukast for chronic cough caused by mycoplasma pneumonia in children. J. New Chin. Med. 51 (1), 70–73. doi:10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2019.01.017

Li, Y. (2020). Analysis of curative effect of Banxia Houpu decoction and Maimendong decoction in treating chronic cough. China Health Vis. 146 (2).

Liang, M. Z., Cheng, H. T., Li, X. J., and Lin, X. J. (2022). Clinical study of Su Jie oral liquid for the treatment of pediatric chronic cough of spleen deficiency and phlegm-damp syndrome type. J. Guangzhou Univ. Traditional Chin. Med. 39 (11), 2554–2557. doi:10.13359/j.cnki.gzxbtcm.2022.11.014

Lin, Y. (2014). Clinical observation of Beiling capsules combined with ambroxol hydrochloride in the treatment of chronic cough. Med. Inf. 27 (6), 188–189. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1006-1959.2014.16.222

Liu, H., and Zhang, L. (2012). Analysis of curative effect of Jiawei Zhisou powder in treating children with chronic cough. Chin. J. Inf. Traditional Chin. Med. 19 (12), 69–70. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1005-5304.2012.12.027

Liu, L. (2020). Efficacy and safety analysis of Linggan Wuwei Jiangxin decoction combined with modified Zhike powder in the treatment of chronic cough. Dajiankang (23), 165–166.

Liu, J. (2022). Clinical effect of modified Chenxia Liujun decoction in the treatment of chronic cough and its impact on quality of life. Chin. Health Care 40 (4), 7–8.

Lu, B. Q., and Pan, X. D. (2014). Effect and mechanism of Ban Xia Xie Xin decoction combined with triple drug therapy of intractable chronic cough. Chin. J. Basic Med. Traditional Chin. Med. 20(8), 1087–1088. doi:10.19945/j.cnki.issn.1006-3250.2014.08.031

Lu, B., Fan, L., and Pan, X. (2013). Clinical research of modified Banxia Xiexin decoction in treating chronic cough. China J. Chin. Med. 28 (8), 1118–1119. doi:10.16368/j.issn.1674-8999.2013.08.009

Luan, L., Yin, Y., and Han, X. (2021). Clinical study on treatment of chronic cough caused by postnasal dripping syndrome with western medicine and Tongqiao Zhike decoction. Contemp. Med. 27 (7), 8–11. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1009-4393.2021.07.003

Lyu, Y. R., Kim, K. I., Yang, C., Jung, S. Y., Kwon, O. J., Jung, H. J., et al. (2022). Efficacy and Safety of Ojeok-San Plus Saengmaek-San for Gastroesophageal Reflux-Induced Chronic Cough: A Pilot, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 787860. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.787860

McGarvey, L. (2013). The difficult-to-treat, therapy-resistant cough: why are current cough treatments not working and what can we do? Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 26 (5), 528–531. doi:10.1016/j.pupt.2013.05.001

Meng, L., Wang, L., Wang, S., and Zhao, J. (2020). Clinical observation on modified Xuanfu Xiama Xiongshaocao decoction in the treatment of chronic cough. Acad. J. Shanghai Univ. Traditional Chin. Med. 34 (3), 18–21. doi:10.16306/j.1008-861x.2020.03.004

Morice, A. H., Fontana, G. A., Belvisi, M. G., Birring, S. S., Chung, K. F., Dicpinigaitis, P. V., et al. (2007). ERS guidelines on the assessment of cough. Eur. Respir. J. 29 (6), 1256–1276. doi:10.1183/09031936.00101006

Morice, A. H., Millqvist, E., Bieksiene, K., Birring, S. S., Dicpinigaitis, P., Domingo Ribas, C., et al. (2020). ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur. Respir. J. 55 (1). doi:10.1183/13993003.01136-2019

Niu, L., Duan, B., Shi, R., and Wu, S. (2020). Efficacy evaluation of Zhisou powder plus montelukast in the treatment of children with chronic cough after mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Clin. Laboratory J. 9 (3), 400.

Ok, I. S., Kim, S. H., Kim, B. K., Lee, J. C., and Lee, Y. C. (2009). Pinellia ternata, Citrus reticulata, and their combinational prescription inhibit eosinophil infiltration and airway hyperresponsiveness by suppressing CCR3+ and Th2 cytokines production in the ovalbumin-induced asthma model. Mediat. Inflamm. 2009, 413270. doi:10.1155/2009/413270

Perotin, J. M., Launois, C., Dewolf, M., Dumazet, A., Dury, S., Lebargy, F., et al. (2018). Managing patients with chronic cough: challenges and solutions. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 14, 1041–1051. doi:10.2147/tcrm.S136036

Qin, J., Chen, J., Peng, F., Sun, C., Lei, Y., Chen, G., et al. (2022). Pharmacological activities and pharmacokinetics of liquiritin: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 293, 115257. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2022.115257

Shen, L., and Huang, Y. (2019). Clinical observation on 40 cases of chronic cough after mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children treated by combined traditional Chinese and western medicine. J. Pediatr. Tradit. Chin. Med. 15 (5), 45–48. doi:10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2019.05.15

Shen, Y., Qian, Y., Ma, W., Wei, L., and Zhang, S. (2017). Clinical study on treatment of chronic cough with Linggan-Wuwei-Jiangxin decoction combined with western medicine. Chin. J. Med. Guide 19 (12), 1337–1339.

Shi, M., Bi, X., and Zhang, W. (2010). Clinical study of Pingjin fang in treating chronic cough. Mod. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 19 (36), 4683–4684. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2010.36.015

Song, W. J., Chang, Y. S., Faruqi, S., Kim, J. Y., Kang, M. G., Kim, S., et al. (2015). The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 45 (5), 1479–1481. doi:10.1183/09031936.00218714

Song, D. J., Song, W. J., Kwon, J. W., Kim, G. W., Kim, M. A., Kim, M. Y., et al. (2018). KAAACI Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Cough in Adults and Children in Korea. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 10 (6), 591–613. doi:10.4168/aair.2018.10.6.591

Song, Y. (2022). Clinical effect and safety evaluation of Linggan Wuwei Jiangxin decoction combined with modified Zhisou powder in the treatment of chronic cough. Orient. Medicat. Diet. 9, 148–149.

Sun, H., and Wei, C. (2020). Efficacy of Runzao Zhisou decoction in treating chronic cough and its effect on serum inflammatory factors. Forum Traditional Chin. Med. 35 (2), 40–42. doi:10.13913/j.cnki.41-1110/r.2020.02.019

Tan, H. Z., and Zheng, Y. F. (2020). Clinical efficacy of reducing the treatment of chronic cough in Xiaochaihu decotion plus or minus. China Mod. Med. 27 (32), 152–154.

Tang, Y., Tu, X., Liu, X., Zhang, J., and Zhou, Y. (2020). A RCT study on the treatment of chronic cough by syndrome differentiating system of five-zang correlation theory. Mod. Tradit. Chin. Med. 40(3), 53–56. doi:10.13424/j.cnki.mtcm.2020.03.015

Thorlund, K., Imberger, G., Johnston, B. C., Walsh, M., Awad, T., Thabane, L., et al. (2012). Evolution of heterogeneity (I2) estimates and their 95% confidence intervals in large meta-analyses. PLoS One 7 (7), e39471. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039471

Tian, Z. (2023). Observation on treatment of 34 cases of infantile chronic cough with lung and spleen deficiency syndrome by Yifei Huatan decoction. Zhejiang J. Traditional Chin. Med. 58 (2), 114–115. doi:10.13633/j.cnki.zjtcm.2023.02.022

Wagner, L., Cramer, H., Klose, P., Lauche, R., Gass, F., Dobos, G., et al. (2015). Herbal Medicine for Cough: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Forsch Komplementmed 22 (6), 359–368. doi:10.1159/000442111

Wang, H., and Li, G. (2019). Observation on curative effect of self-made Qingre Xuanfei Qufeng Liyan recipe in the treatment of chronic cough with wind-cough syndrome. J. Sichuan Traditional Chin. Med. 37 (9), 77–80.

Wang, W., and Xu, Y. (2022). Clinical observation on chronic cough treated by Linggan Wuwei Jiangxin decoction combined with modified Zhisou powder. China Health Care Nutr. 32 (10), 166–168.

Wang, L., and Zang, L. (2016). Observation on curative effect of combination of traditional Chinese and western medicine in treating chronic cough of phlegm-heat accumulation. Shanxi J. Traditional Chin. Med. 32 (2), 29–30.

Wang, L., and Zhou, X. (2016). Observation on curative effect of Linggan Wuwei Jiangxin decoction combined with western medicine in treating chronic cough. J. New Chin. Med. 48 (12), 32–33. doi:10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2016.12.014

Wang, Y., Fan, X., Qu, H., Gao, X., and Cheng, Y. (2012). Strategies and techniques for multi-component drug design from medicinal herbs and traditional Chinese medicine. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 12 (12), 1356–1362. doi:10.2174/156802612801319034

Wang, Z., Wang, M., Wen, S., Yu, L., and Xu, X. (2019). Types and applications of cough-related questionnaires. J. Thorac. Dis. 11 (10), 4379–4388. doi:10.21037/jtd.2019.09.62

Wang, H. (2012). Clinical observation on treating chronic cough with liver-cough syndrome from the liver. Beijing J. Traditional Chin. Med. 31 (7), 531–532. doi:10.16025/j.1674-1307.2012.07.017

Wang, S. (2020). Bufei Zhike decoction in the treatment of children's chronic cough. Acta Chin. Med. 35 (7), 1555–1559. doi:10.16368/j.issn.1674-8999.2020.07.347

Watanabe, N., Cheng, G., and Fukuda, T. (2003). Effects of Bakumondo-to (Mai-Men-Dong-Tang) on cough sensitivity to capsaicin in asthmatic patients with cough hypersensitivity. Arerugi 52 (5), 485–491.

Watanabe, N., Gang, C., and Fukuda, T. (2004). The effects of bakumondo-to (mai-men-dong-tang) on asthmatic and non-asthmatic patients with increased cough sensitivity. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 42 (1), 49–55.

Won, H. K., Lee, J. H., An, J., Sohn, K. H., Kang, M. G., Kang, S. Y., et al. (2020). Impact of Chronic Cough on Health-Related Quality of Life in the Korean Adult General Population: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010-2016. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 12 (6), 964–979. doi:10.4168/aair.2020.12.6.964

Wu, X., and Li, P. (2020). Observation on therapeutic effect of Tongdiao Sanjiao method in treating chronic cough. Shanxi J. Traditional Chin. Med. 36 (9), 50–51. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7156.2020.09.024

Wu, X., Liu, J., Zhang, Q., and Kuang, Y. (2019). Clinical efficacy of Jiawei Zhisou tablets in the treatment of chronic cough. Inn. Mong. J. Traditional Chin. Med. 38 (11), 14–15. doi:10.16040/j.cnki.cn15-1101.2019.11.008

Xia, H. (2021). Analysis of curative effect of self-made Xuanfei Zhisou decoction in adjuvant treatment of chronic cough with wind-evil subduing lung syndrome. Cap. Med. 28 (15), 168–169. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1005-8257.2021.15.087

Xie, J. J., Yang, C. Y., Huang, Y. L., Zeng, X. L., and Lin, G. B. (2012). Clinical observation of radix ophiopogon decoction treatment of chronic cough. Guide China Med. 10 (6), 43–44. doi:10.15912/j.cnki.gocm.2012.06.013

Xie, B. (2017). Clinical effect analysis of traditional Chinese medicine granules in the treatment of chronic cough. Nei Mongol J. Traditional Chin. Med. 36 (16), 41. doi:10.16040/j.cnki.cn15-1101.2017.16.041

Xu, Z. (2017). Clinical study of Bufei tang combined with western medicine for chronic cough in elderly patients. J. New Chin. Med. 49 (3), 41–43. doi:10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2017.03.013

Yan, F., Wei, J., and He, X. (2018). Clinical application and effect evaluation of Yupingfeng powder in treating children with chronic cough. Asia-Pacific Traditioanl Chin. Med. 14 (7), 188–189. doi:10.11954/ytctyy.201807074

Yang, J. L., and Yang, X. (2012). Analysis of clinical curative effect of Jiang Xin Huatan Zhike decoction for 51 patients with chronic cough. J. Pract. Traditional Chin. Intern. Med. 26 (6), 32–33. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-7813.2012.06.17

Yang, H., Wang, X., Wang, J., Chen, W., and Wang, J. (2019). Curative effect of Qingfei Runzao decoction in treating chronic cough of wind-dryness injury to the lung type and its regulatory effect on NGF, IL-4 and IL-17. J. Sichuan Traditional Chin. Med. 37 (10), 83–86.

Yang, Y., Li, R., Yang, M., and Liu, F. (2020). Clinical observation on treatment of chronic cough syndrome of wind-evil subduing the lung with combination of traditional Chinese and western medicine. Yunnan J. Traditional Chin. Med. Materia Medica 41 (9), 50–52. doi:10.16254/j.cnki.53-1120/r.2020.09.017

Yang, Q., Li, J., Zhao, T., Yang, H., and Qiu, J. (2022). Clinical observation on the treatment of children with chronic cough phlegm dampness syndrome by Shan San decoction. China's Naturop. 30 (21), 52–55. doi:10.19621/j.cnki.11-3555/r.2022.2118

Yi, K. C., and Zheng, Y. F. (2020). Clinical effect of Shashen Yuzhu decoction plus minus on the treatment of chronic cough. China Mod. Med. 27 (12), 16–19.

Yu, S., Guan, Z., Cheng, S., and Song, G. (2014). Treating 40 children with chronic cough from the liver. Traditional Chin. Med. Res. 27 (9), 24–26. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-6910.2014.09.11

Yu, P., Cheng, S., Xiang, J., Yu, B., Zhang, M., Zhang, C., et al. (2015). Expectorant, antitussive, anti-inflammatory activities and compositional analysis of Aster tataricus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 164, 328–333. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.036

Zhang, Y., and Chen, K. (2020). Clinical efficacy of Chaihuang Granules combined with tulobuterol in the treatment of children with chronic cough. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 42 (12), 3372–3374. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-1528.2020.12.054

Zhang, M. Y., and Wang, X. H. (2022). Efficacy observation of modified Maxing Shigan decoction and compound methoxyphenamine capsule on chronic cough. Shanxi J. Traditional Chin. Med. 38 (4), 13–15. doi:10.20002/j.issn.1000-7156.2022.04.005

Zhang, L., Hua, J., and Qiao, N. (2016). Clinical study on treating unexplained chronic cough with Xuanfei Pinggan therapy. J. Shaanxi Univ. Chin. Med. 39 (6), 60–62. doi:10.13424/j.cnki.jsctcm.2016.06.019

Zhang, C., Liang, J., Zhou, L., Yuan, E., Zeng, J., Zhu, J., et al. (2021a). Components study on antitussive effect and holistic mechanism of Platycodonis Radix based on spectrum-effect relationship and metabonomics analysis. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 1173, 122680. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2021.122680

Zhang, H., Xu, H., Lu, H., Lu, B., Shu, J., Qian, X., et al. (2021b). A clinical observance on the effect of Ganmai Dazao decoction combined with Zhizichi decoction in the treatment of chronic cough in menopausal women. Jilin J. Chin. Med. 41 (10), 1319–1321. doi:10.13463/j.cnki.jlzyy.2021.10.018

Zhao, Y. L., and Tuo, X. P. (2022). Clinical efficacy of Xuanfei Yunpi decoction in the treatment of children with chronic cough of phlegm dampness accumulating lung type and its effect on inflammatory factors and immune function. Hainan Med. J. 33 (12), 1559–1562. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-6350.2022.12.018

Zhao, L., Wang, X., and Meng, N. (2022a). Observation on curative effect of modified Liujunzi decoction in treating children with chronic cough based on the theory of lung and spleen. Harbin Med. J. 42 (6), 139–141. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-8131.2022.06.060

Zhao, Y., Wang, D., Guo, J., Zhou, M., and Zhao, Y. (2022b). Observation on the effect of budesonide nebulization inhalation combined with Shegan Mahuang decoction in the treatment of chronic cough. Yaowu Yu Linchuang 11, 62–63.

Zhou, X. B., Zhang, H. S., and Li, W. (2017). Clinical observation on the treatment of chronic cough in children with Xuanshenshengma decoction combined with compound oxygen. J. Hunan Norm. Univ. 14 (4), 4–6.

Zhou, M., Lu, J., Feng, C., Wang, X., and Chen, Z. (2021). Effect of Qingganningfei recipe on lung function and serum immunoglobulin level in chronic cough patients with liver fire invading lung. J. Hunan Univ. Chin. Med. 41 (11), 1802–1806. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-070X.2021.11.027

Zhou, M., Lyu, J., Feng, C., Wang, X., and Chen, Z. (2022). Clinical study of Linggan Wuwei Jiangxin decoction combined with Zhisou powder in treatment of young patients with chronic cough with syndrome of cold fluid retention in lung. Shangdong J. Traditional Chin. Med. 41 (12), 1292–1295. doi:10.16295/j.cnki.0257-358x.2022.12.008

Zhou, X. (2011). 42 cases of children with chronic cough caused by mycoplasma pneumonia infection treated by combination of traditional Chinese and western medicine. Jilin Med. J. 32 (36), 7738.

Zhou, F. (2018). Clinical observation on Zhisou san in the treatment of chronic cough. China Contin. Med. Educ. 10 (21), 143–144. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-9308.2018.21.074

Zhu, Y. (2012). Treating chronic cough with Jiajian Shashan Maidong decoction 68 cases. J. Pract. Traditional Chin. Intern. Med. 26 (18), 21–22. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-7813.2012.12.11

Keywords: herbal medicine, chronic cough, cough, systematic review, East Asian traditional medicine

Citation: Lee B, Kwon C-Y, Suh H-W, Kim YJ, Kim K-I, Lee B-J and Lee J-H (2023) Herbal medicine for the treatment of chronic cough: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 14:1230604. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1230604

Received: 29 May 2023; Accepted: 28 September 2023;

Published: 17 October 2023.

Edited by:

Subhash C. Mandal, Government of West Bengal, IndiaReviewed by:

Mruthunjaya Kenganora, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, IndiaCopyright © 2023 Lee, Kwon, Suh, Kim, Kim, Lee and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jun-Hwan Lee, b21kanVuQGtpb20ucmUua3I=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.