94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol. , 05 May 2023

Sec. Neuropharmacology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1185277

This article is part of the Research Topic Therapies for Brain Injury View all 7 articles

Noha O. Mansour1

Noha O. Mansour1 Mohamed Hassan Elnaem2,3*

Mohamed Hassan Elnaem2,3* Doaa H. Abdelaziz4

Doaa H. Abdelaziz4 Muna Barakat5,6

Muna Barakat5,6 Inderpal Singh Dehele7

Inderpal Singh Dehele7 Mahmoud E. Elrggal8

Mahmoud E. Elrggal8 Mahmoud S. Abdallah9

Mahmoud S. Abdallah9Objectives: Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the top causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The review aimed to discuss and summarize the current evidence on the effectiveness of adjuvant neuroprotective treatments in terms of their effect on brain injury biomarkers in TBI patients.

Methods: To identify relevant studies, four scholarly databases, including PubMed, Cochrane, Scopus, and Google Scholar, were systematically searched using predefined search terms. English-language randomized controlled clinical trials reporting changes in brain injury biomarkers, namely, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP), ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal esterase L1 (UCHL1) and/or S100 beta (S100 ß), were included. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.

Results: A total of eleven studies with eight different therapeutic options were investigated; of them, tetracyclines, metformin, and memantine were discovered to be promising choices that could improve neurological outcomes in TBI patients. The most utilized serum biomarkers were NSE and S100 ß followed by GFAP, while none of the included studies quantified UCHL1. The heterogeneity in injury severity categories and measurement timing may affect the overall evaluation of the clinical efficacy of potential therapies. Therefore, unified measurement protocols are highly warranted to inform clinical decisions.

Conclusion: Few therapeutic options showed promising results as an adjuvant to standard care in patients with TBI. Several considerations for future work must be directed towards standardizing monitoring biomarkers. Investigating the pharmacotherapy effectiveness using a multimodal biomarker panel is needed. Finally, employing stratified randomization in future clinical trials concerning potential confounders, including age, trauma severity levels, and type, is crucial to inform clinical decisions.

Clinical Trial Registration: [https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/dis], identifier [CRD42022316327].

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally (Dewan et al., 2018). Annually, an estimated 50–60 million new cases are reported. Survivors typically suffer from post-traumatic challenges ranging from neurological and psychosocial issues to permanent disabilities (Quaglio et al., 2017). Neural damage post-brain trauma falls into two categories: primary insult, which is directly caused by mechanical forces in the initial injury and delayed secondary insult, which results from a subsequent cascade of cellular and biochemical events (Ng and Lee, 2019). The primary pathophysiology of secondary injury is still lacking; however, mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptotic cell death are mechanistically assumed to be the primary contributors (Ray et al., 2002). Oxidative stress (Khatri et al., 2018) and neuroinflammation (Simon et al., 2017) also play an important role in this process. Brain edema and the resulting elevated intracranial pressure are major contributors to the adverse prognosis in patients with brain trauma. Therefore, early preventive strategies against secondary brain injury are crucial for improving the clinical outcomes of those patients (Jha et al., 2019).

Current management relies on immediate interventions to stabilize patients, such as decompressive craniectomy (Hawryluk et al., 2020), nutrition management (Vella et al., 2017), or prophylactic hypothermia (Chen et al., 2019), but their benefits did not presume to reduce the secondary neural damage. So far, no pharmacotherapy could modulate the primary insult. Nevertheless, therapeutic interventions in the acute phase have focused on restricting the cellular cascade of secondary insults. Numerous clinical studies have searched for early adjunctive treatments to prevent further neuronal damage and improve functional recovery (Langham et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2015; Synnot et al., 2018). The clinical trials failure has been linked to the absence of central biomarkers for medication monitoring, TBI heterogeneity, and the limited translatability of TBI preclinical studies (Wang et al., 2018).

The pathophysiologic processes of TBI involve axonal injury, neuronal cell body injury, and microglia responses. To monitor these different processes, thus far, a panel of biomarkers has been recognized. Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) is a neuronal acute injury biomarker. It is one of the most clinically used biomarkers to monitor the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions (Yokobori et al., 2013). Enolase is a key enzyme of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, two vital metabolic pathways for cellular functions. Neuron-specific enolase is expressed abundantly in neuronal cell bodies. In intact neurons, NSE is not normally secreted in extracellular fluids; however, when neurons are damaged, NSE is upregulated to maintain homeostasis. Higher NSE levels can be detected in the serum in patients with neuronal injury. This extracellular release is caused partly by leakage from injured neurons. The upregulation of NSE also contributes to this elevation to initiate repair mechanisms. Therefore, NSE directly assesses functional damage to neurons (Cheng et al., 2014). The lack of brain specificity is a major limitation of NSE. Neuron-specific enolase is abundant in RBCs, which may produce false positive results. (Graham et al., 2016). Higher NSE concentrations (>20 μg/L) were found to be associated with higher mortality rates in patients with moderate and severe brain injuries (Cheng et al., 2014).

S-100β protein, the β subunit of a calcium-binding protein produced by astrocytes, is one of the most well-characterized biomarkers of TBI. Increased S-100β serum levels after brain injury were linked to glial damage. S-100β protein peaks early in the first 6 h, and a second peak, more sensitive to neuronal injury severity, occurs after 48 h post-injury (Slavoaca et al., 2020). High serum levels of S-100β had significant correlation with injury severity and prognosis; levels ranging from 1.38 μg/L to 10.5 μg/L and from 2.16 μg/L to 14.0 μg/L were connected with 100% specificity for mortality and a Glasgow outcome score (GOS) ≤3 respectively (Mercier et al., 2013).

Glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) is a key intermediate filament-III protein uniquely found in astrocytes, one of the glial cells. It strengthens the cytoskeleton structure for glial cells and supports the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (Abdelhak et al., 2022). The primary strength of GFAP as a brain injury biomarker is brain specificity; it is only found within the CNS (Graham et al., 2016). Like S-100β protein, high serum levels of GFAP are quickly detected in the first 24 h post-injury (Slavoaca et al., 2020).

Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCHL1) is a cysteine protease predominately expressed in neuronal cell bodies. Due to its specific expression in brain tissue, high serum levels of UCHL1 have been used as a marker of neuronal cell body injury.

Several neuroprotective agents have been evaluated regarding their modulating effects on brain injury biomarkers. Yet, the evidence remains inconclusive. Recent reviews of potential neuroprotective candidates relied on evaluating their effects on the widely used GOS and/or its extended version, GOS-E (Begemann et al., 2020; Liu M. et al., 2020; Solla and Paiva, 2021). There have been many criticisms of their subjectivity in measuring recovery from TBI (Shukla et al., 2011). These scales rely on self-assessment or assessment of a caregiver rather than quantifiable measurements of disability (Iyer et al., 2009). The quantitative outcome measures would be beneficial, although these may be more expensive and time-consuming to implement(Ma et al., 2016). Other reports evaluated the survival benefits and the incidence of unfavorable neurological outcomes. Despite their importance, these measures could be confounded by factors such as injury severity level (Okidi et al., 2020) and age (Hukkelhoven et al., 2003). Based on the clinical utility of brain injury biomarkers and their ability to inform therapeutic decision-making in patients with central trauma, this review aimed to comprehensively discuss and summarize the available evidence from randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) that evaluated novel options in terms of their effects on acute injury biomarkers to bridge the knowledge gap and allow new therapy development.

This systematic review’s findings were reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline.

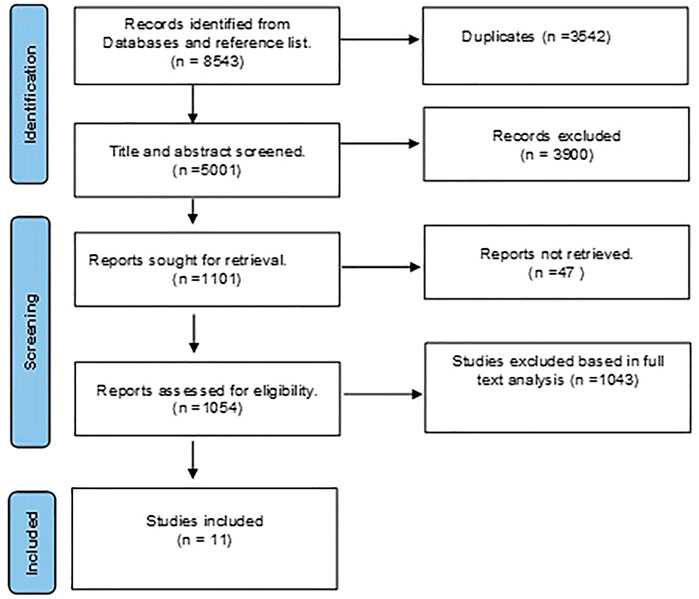

The study protocol was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews PROSPERO registry (registration number: CRD42022316327). A systematic search was conducted on four major electronic databases: PubMed, Cochrane, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Clinical trials published till March 2022 were included (Figure 1). The following terms were searched: “head trauma”, “traumatic brain injury”, “brain trauma”, “neuron-specific enolase”, NSE, “Glial fibrillary acidic protein”, GFAP, “S100β", UCHL, “Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase”, and “brain injury biomarkers”. To retrieve relevant trials, registries such as ClinicalTrials.gov were searched for trials undertaken in TBI patients. The search was limited to trials investigating the additive effects of any pharmacotherapy on potentially modulating injury biomarkers in those patients. To increase the likelihood of finding additional relevant papers, the reference lists of the retrieved articles as well as the “related articles” feature in PubMed, were reviewed. A manual search of reference lists for all related reviews was also conducted. Simvastatin, cilostazol, N-acetyl cysteine, and melatonin were searched manually based on their previously reported neuroprotective properties in TBI (Begemann et al., 2020).

FIGURE 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metanalysis (PRISMA) flowchart for eligible studies selection process.

Original studies published on pharmacotherapeutic options in TBI patients were eligible for inclusion. For inclusion eligibility, the records were separately examined by two authors (MHE and NOM). A third author (DHA) was brought in to settle any disputes, and all decisions were reached by consensus. Eligible studies were obtained in full text to be included, and their methodological quality were evaluated.

Data from the selected studies were extracted using a standardized form. The following basic information was extracted from the RCTs: name of the lead author, year of publication, site, study design (randomization, blinding), sample size, patient population (age; severity of injury according to GCS scores), interventions (type of pharmacological agent; dosing regimen), outcomes (monitored biomarkers, time of sampling), main results, and conclusions.

Studies and trials meeting the following criteria were included:

• Study design: RCTs published in the full-text version.

• Population: patients with a clinical diagnosis of TBI or diffuse axonal injury (DAI) regardless of severity.

• Interventions: pharmacological agent with neuroprotective effects (such as delayed neuroinflammation, neuronal cell death, and neurological Dysfunction). Agents could be administered in any regimen initiated immediately in the acute phase of TBI.

• Comparators: active comparator, placebo or no drugs

• Outcomes: The change in an acute brain injury biomarker.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

• Studies evaluated non-pharmacological drug therapy such as decompressive craniectomy, therapeutic hypothermia, and nutritional supplements.

• Assessing the efficacy of adjuvant treatment based on functional and/or clinical outcomes such as GOS, GOS-E, and mortality.

• Studies in polytrauma patients or the presence of accompanying other neurodegenerative diseases.

• Studies of interventions implemented in the post-acute and chronic phases.

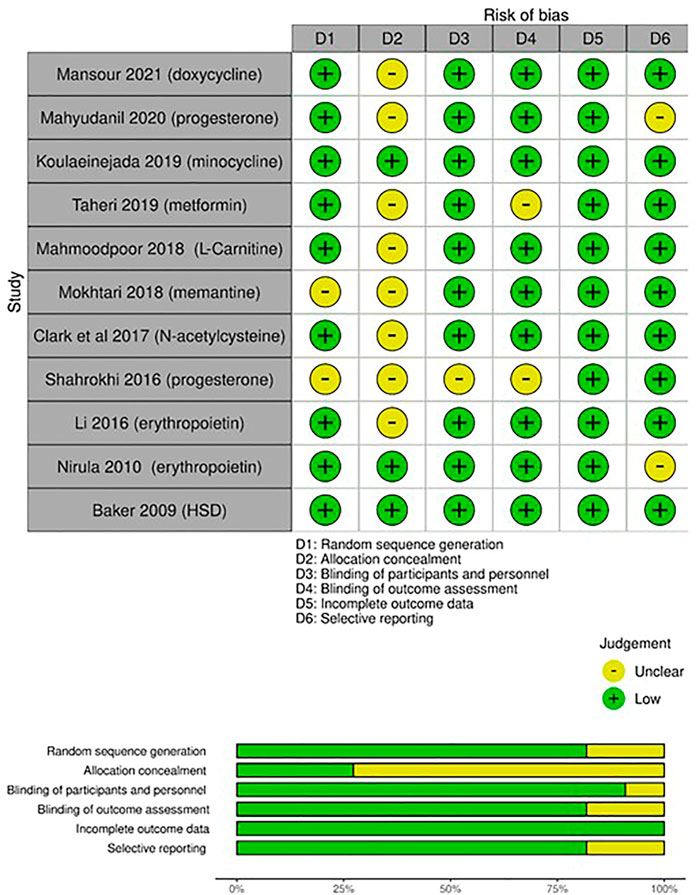

Each RCT’s level of evidence was assessed using the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias (RoB) tool to identify any potential bias risks (Higgins and Altman, 2008). Two authors independently assessed the included studies’ methodological quality using this approach. A third author was consulted in case of disagreement concerning the risk of bias. The following items were evaluated:

Methods used to generate the sequence.

Assessment of whether intervention allocations could have been foreseen before or during enrollment. Accurate reporting of the technique utilized to mask the allocation sequence was evaluated.

Description of procedures taken to blind trial patients and investigators from knowledge of allocated study intervention.

Description of procedures to mask outcome assessors from knowledge of allocated study intervention

Describe the accuracy of the outcome information for each primary outcome, considering attrition and analytical exclusions.

Assessment of the possibility of selective outcome reporting by the authors.

Each of the aforementioned items was assigned a low, high, or unclear risk level. To assess selection bias, randomization sequence generation and allocation concealment were used. Blinding participants and/or investigators represented the risk of performance bias. Blinding outcome assessors represented the risk of detection bias, and each trial’s reporting bias was assessed using incomplete outcome data.

A total of 8543 studies were discovered during the primary scholarly search. We eliminated 3542 duplicate studies using EndNote. The remaining studies were reviewed, and 1054 qualified for full-text analysis. As a result, 1043 studies were eliminated because they failed to meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, eleven studies that evaluated different pharmacotherapeutic agents on the prespecified biomarkers in TBI patients were incorporated into this review (Figure 1).

Table 1 illustrates an overview of the summary of the studies based on trial design, study population, and conclusions. Erythropoietin, progesterone, and tetracyclines (two studies each); N-acetyl cysteine, fluid therapy; metformin, L-carnitine, and memantine (one each). All the included studies were single-center studies distributed as follows: Iran (n = 4), unspecified (n = 2), Egypt (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), China (n = 1), Indonesia (n = 1), and United States (n = 1). The review included eleven RCTs. Most studies included small sample sizes ranging from 14 to 159 patients. Regarding injury severity, the GCS was used to classify TBI subjects as severe (GCS ≤8), moderate (GCS 9–12), and mild (GCS 13–15) in all reports (Wang et al., 2018). Seven RCTs enrolled patients in one category of TBI severity (6 RCTs in patients with severe injury (Baker et al., 2009; Li et al., 2016; Clark et al., 2017; Mahmoodpoor et al., 2018; Taheri et al., 2019; Mahyudanil et al., 2020); and 1 RCT in patients with moderate injury (Mokhtari et al., 2018)). Four articles reported data that applied to multiple severity categories (Nirula et al., 2010; Shahrokhi et al., 2016; Koulaeinejad et al., 2019; Mansour et al., 2021).

All included studies measured biomarkers in the serum of the patients. The most commonly used biomarker (n = 9) was NSE (Baker et al., 2009; Nirula et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016; Shahrokhi et al., 2016; Clark et al., 2017; Mahmoodpoor et al., 2018; Mokhtari et al., 2018; Koulaeinejad et al., 2019; Mansour et al., 2021), followed by S100 ß (n = 6) (Baker et al., 2009; Nirula et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016; Koulaeinejad et al., 2019; Taheri et al., 2019; Mahyudanil et al., 2020). Glial fibrillary acid protein was monitored in two studies (Clark et al., 2017; Taheri et al., 2019). None of the included studies quantified UCHL1. Five of the included RCTs reported change over time only in one acute injury biomarker, six studies reported changes in two biomarkers, and none of the included articles monitored more than biomarkers. Commercially available enzyme-linked immunoassay analysis kits assessed serum biomarkers in ten studies, while monoclonal immunoluminometric assay was used only once. Studies greatly varied in terms of the number and timing of follow-up measurements. Repeated longitudinal assay of biomarkers levels was detected in all included studies. The time frame of the assay greatly varied between studies. The assay timing started on day one (randomization day) and was followed thereafter by serial measurements for up to 3 months. Detailed description of biomarker measurement in each study is depicted in Table 1.

The Cochrane RoB assessment tool was used to evaluate the quality of the RCTs. The quality of included RCTs and the RoB per item are presented in Figure 2. Methods used for random sequence generation were detailed in more than 80% of the included studies. Nonetheless, there was a lack of adequate description of the methods used to conceal the allocation sequence in about 75% of the included studies. Thus, a high risk of selection bias may be presumed. Differences in the care received by the intervention and control groups were minimized in most of the included studies by properly describing the masking procedures. Low risk of detection bias was noted among the included RCTs. Most of the included studies had risks of undermining the validity mainly due to small sample sizes and lack of description of methods of estimating sample size and power.

FIGURE 2. Risk of bias assessment (RoB) according to the Cochrane RoB tool for randomized controlled trials (RCTs): risk of bias per item for each study; risk of bias per item presented as percentages across all included RCTs.

This research investigated whether brain injury biomarkers may be normalized in TBI patients by using drugs that have neuroprotective properties. S100B and NSE were the biomarkers that were mostly monitored, followed by GFAP. Similar findings have been reported by Marzano et al., who summarized the recent findings in the medical literature about the diagnostic and prognostic value of brain injury biomarkers in the pediatric population with TBI (Marzano et al., 2022). Eleven studies were summarized for qualitative analysis to understand better how current literature supports the effectiveness of early adjunctive pharmacotherapy, including tetracyclines, progesterone, erythropoietin, metformin, L-carnitine, resuscitation fluid, and memantine.

The merits of tetracyclines as neuroprotective agents have been previously recognized in a variety of neurodegenerative conditions, including Parkinson’s disease (Santa-Cecília et al., 2019), Alzheimer’s disease (Balducci et al., 2018), and multiple sclerosis (Minagar et al., 2008). Our findings included two studies that examined the short-term effectiveness of additional tetracyclines in TBI patients: doxycycline and minocycline. Both agents were used in regular, approved doses (100 mg BID). Consistent results and promising effects in terms of the impact on the brain injury biomarkers have been reported in both RCTs. According to Mansour et al., NSE levels were significantly lowered in patients assigned to the doxycycline group compared to those assigned to the placebo (12.81 ng/mL versus 16.43 ng/mL (p = 0.003). Additionally, significant larger proportion of patients had normalized NSE levels with early doxycycline administration (≤12 ng/mL) (45% in doxycycline group vs 25% in Placebo) (Mansour et al., 2021). Likewise, Koulaeinejad et al. noted a marked reduction in NSE from baseline to day 5 with early minocycline administration (p = 0.01) (Koulaeinejad et al., 2019). The exact molecular mechanism behind the neuroprotective effects of tetracyclines is still unclear. However, it is reasonable to suggest that inhibition of apoptosis (Elewa et al., 2006), repair of the blood-brain barrier (Plane et al., 2010; Malek et al., 2020), and the neuro-anti-inflammatory actions (Elewa et al., 2006) (Chaves Filho et al., 2021) are thought to be the main contributing factors to the reported benefit. These findings provide a sufficient basis for further investigations. Nevertheless, both studies were limited by the small sample size and the pilot study design. Randomizing patients with moderate and severe brain trauma limits data generalizability to those with mild TBI. Larger clinical trials, with stratified randomization according to severity, are crucial to informing the drug development process better. In addition, the promises shown in the acute phase of TBI encourage prolonged administration to modulate functional recovery and mortality.

Erythropoietin, a multi-functional cytokine released in the kidney and CNS, has been proposed as a potential neuroprotective agent (Schober et al., 2018). Erythropoietin has been shown to be effective against several early mediators of secondary brain injury in preclinical studies, mainly via reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhancing the anti-inflammatory cytokines in brain tissue (Zhou et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2021). Besides, preserving brain oxygenation by erythropoietin is involved in its anti-oxidative and glial protective actions in patients with TBI (Lee et al., 2019). These aforementioned properties might contribute to the erythropoietin-induced neuroprotective effects. Supporting the previous preclinical data, our results included one RCT (n = 159) with a positive outcome. In this study, Li et al. reported the effectiveness of low-dose erythropoietin in patients with severe TBI. Lower levels of NSE and S100ß were detected in patients who were randomized to receive erythropoietin (administered in five doses (100 units/kg) for 12 days) compared to the control (Li et al., 2016).

Conversely, another earlier study pilot study (n = 16) by Nirula et al. (Nirula et al., 2010) failed to demonstrate similar efficacy with erythropoietin use (40,000 Units IV within 6 h) on the same biomarkers. The discrepancy in the reported outcomes across the two RCTs included in the present review could be explained by the differences in sample size, dosing regimen, and severity of neuronal injury among recruited patients. Two meta-analyses recently concluded that early use of erythropoietin lowered the mortality risk (Lee et al., 2019; Liu C. et al., 2020). Nonetheless, no difference was found concerning the enhancement of neurological outcomes. The dose and timing of erythropoietin injections varied considerably across the reviewed studies in the previous reviews. Given the cost, more research is required to define the merits of erythropoietin use in this particular clinical indication.

Steroid hormones are produced mainly by adrenal glands and gonads and control the function of several target organs, including the brain. In addition, some steroids are de novo synthesized glial cells called “neuro-steroids. Circulating progesterone passes the blood-brain barrier owing to its lipophilic properties. It is also a neurosteroid locally synthesized by the glial cells in the brain tissue. Growing evidence from reviews of experimental research in animal models indicates that progesterone has a neuroprotectant effect. These benefits might be explained by reducing brain edema (Wang et al., 2013), blood-brain barrier stabilizing effect (Si et al., 2014), and reduction of the inflammatory response post-trauma (Chen et al., 2008; Lei et al., 2014). However, evidence about the effects of progesterone on brain injury biomarkers is scarce. Only two small-scale studies examined the impact of progesterone on NSE and reported negative results. Due to the small sample size, these findings should be interpreted cautiously. According to a Cochrane review of three RCTs, the neurologic prognosis of TBI patients may be enhanced with progesterone. Nevertheless, this evidence is still insufficient, and further multicenter trials are required (Ma et al., 2016)

Microglia, the CNS macrophages, are involved in neurodegenerative disease pathogenesis. Microglial cells become activated within minutes of brain injury. Once activated, microglia secrets pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins, TNF-α, and free radicals (Ramlackhansingh et al., 2011). Suppressing the pro-inflammatory microglial cells has been recently targeted to attenuate the rate of inflammation and consequent neurological deficit in animal models (DiBona et al., 2021; Bourget et al., 2022). Apart from suppressing microglial activation, a growing body of evidence proves that metformin neuroprotective effects are attributable to AMP-activated protein kinase activation (Rahimi et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). The efficacy of metformin therapy was investigated in one RCT. Administration of 1 g metformin BID for 5 days. Analysis of the S100ß level revealed statistically significant decreases in values toward normal levels in the intervention group. Contrarily, the dynamics of serum GFAP levels in the two study groups were not statistically different at all study time points. Safety data reported that metformin is tolerable, with no events of hypoglycemia or lactic acidosis reported in study participants. Considering the possible disease-modifying effects on the pharmacokinetics of metformin in patients with severe TBI. Taheri et al. showed that the intervention group needed a longer time to reach its maximum metformin concentration than healthy subjects (Taheri et al., 2019). Thus, the time required to reach the site of action in the CNS may be prolonged. Future larger studies of metformin use with prokinetic agents might augment the shown benefit.

The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors are linked to neuronal cell death through different mechanisms, including excitotoxicity and apoptosis. Activation of glutamate receptors increases calcium influx, resulting in neuronal apoptosis. On the other hand, significant glutamate release results in magnesium loss in the glutamate receptor’s ion channel. Consequently, neuronal cells depolarize, swell, and necrotize (Khan et al., 2021). Preclinical models indicate that glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity is pivotal in the secondary injury cascade. Mokhtari et al. investigated the effect of NMDA receptor blocking via memantine (30 mg BID for 7 days) in moderate TBI patients (Mokhtari et al., 2018). A promising neuroprotective effect was reported with early memantine use (within the first 24 h post-injury). Serum NSE levels in the memantine group were significantly lower than in the control group from day 0 to day seven (p = 0.009). This effect was linked to a significant daily improvement in the patient’s GCS scores.

N-acetyl l-cysteine, a sulfur-containing amino acid, replenishes glutathione and may lessen subsequent brain damage. Reliable preclinical data showed a strong association between N-acetyl cysteine administration and improved neurological outcomes. Preventing sequelae from induced TBI was mainly illustrated by counteracting the increased oxidative stress, promoting redox-controlled cell signaling, and reducing immuno-inflammatory reactions post-trauma (Bhatti et al., 2018). The effectiveness of N-acetyl cysteine has been evaluated in different neurodegenerative diseases (Tardiolo et al., 2018). Despite n-acetyl cysteine’s low blood-brain barrier permeability, its actions as neuroprotectants when combined with probenecid have been investigated in a pediatric placebo-controlled trial (Clark et al., 2017). The serum levels of neuro-injury biomarkers in the participants did not differ after administration of n-acetyl cysteine, compared with a control group. Given the dearth of studies, conclusive results could not be elucidated. Further research is needed. Its amide derivative, N-acetylcysteine amide, has increased BBB permeability, implying increased CNS bioavailability (Matthiesen et al., 2021). However, it has not been clinically investigated in brain trauma patients.

Despite the availability of several pharmacotherapeutic options, TBI management is still challenging, and many areas of uncertainty persist. The section highlights four main selected issues in the current studies. Also, recommendations that help address these issues in upcoming clinical studies are underlined to guide the development of evidence-based recommendations. Table 2 presents a summary of these pitfalls and the relevant recommendations to be considered in future research.

The timing of blood samples for biomarkers is unlikely to be crucial in some neurodegenerative diseases (Zetterberg and Bendlin, 2021). On the contrary, sampling timing is critical in TBI (Bogoslovsky et al., 2016; Thelin et al., 2017). So far, there are only a few kinetic studies of blood biomarkers after TBI. Moreover, trials with primary endpoints rely on monitoring response to therapy based on biomarkers levels require a protocolized algorithm that directs sampling based on each biomarker’s kinetics. This would lessen the effect of variances on the reported outcome.

Type and severity of injury: In mild TBI, patients might have no or minimal disruption of the blood-brain barrier, while it occurs with moderate or severe brain injury in about 40% of the cases (Saw et al., 2014; Hier et al., 2021). This conceivably affects levels of biomarkers that enter the peripheral blood. Further research should carefully consider the severity of injury to enhance the external validity of their findings.

Renal functions: some biomarkers are renally eliminated, and kidney dysfunction can prolong the elimination half-life in the blood and elevate biomarker blood levels (Hier et al., 2021).

Exploring the potential benefits of the promising agents reported in the current review, such as metformin and tetracyclines, on other emerging novel biomarkers, neurofilament light chain protein (NF-L) (Halbgebauer et al., 2022), and Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) (Wang et al., 2021).

There are several promising agents for future clinical research, as follows:

• High-dose vitamin D offered neuroprotective effects in patients with moderate ischemic stroke (Hesami et al., 2022). Similar action might be expected in patients with TBI.

• Melatonin has anti-apoptotic, brain edema-reducing, and anti-inflammatory effects (Seifman et al., 2014; Lorente, 2017).

• Nicotinamides’ early administration reduced apoptosis and prevented blood-brain barrier damage, yet potential benefits are not clinically examined (Jacquens et al., 2022).

This review provides the latest and comprehensive update for all pharmacotherapeutic choices for early adjuvant therapy in patients with traumatic brain injury. We reported the impact of these therapies on commonly reported brain injury biomarkers. We have also highlighted common issues encountered in the evidence synthesis process and the relevant recommendations for future work in the same area.

Nevertheless, this work has several limitations. First, it did not address delayed axonal injury demyelination markers biomarkers such as neurofilament light chain (NF-L) and myelin basic protein (MBP). The small number of the included studies represents another notable limitation. The heterogeneity in injury severity categories, and measurement timing may affect the overall evaluation of the clinical efficacy of potential therapies.

This review integrates for the first-time comprehensive evidence on the impact of early adjuvant neuroprotective pharmacological interventions on serum levels of brain injury biomarkers inpatients with brain trauma. The use of multi-modal approach to explore combining different biomarkers is needed in future clinical trials. A unified measurement protocol is highly warranted to inform clinical decisions. Employing stratified randomization concerning potential confounderssuch as age, trauma severity levels, and type are crucial in future investigations.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conceptualization, NM, MHE, and MA; methodology, NM, MHE, and DA; validation MB, DA, and MA; writing—original draft preparation, MHE and NM; writing—review and editing, MB; MA, MEE, ISD and DA, all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation of the Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through project number IFP22UQU4320605DSR178.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abdelhak, A., Foschi, M., Abu-Rumeileh, S., Yue, J. K., D'Anna, L., Huss, A., et al. (2022). Blood GFAP as an emerging biomarker in brain and spinal cord disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 18 (3), 158–172. doi:10.1038/s41582-021-00616-3

Baker, A. J., Rhind, S. G., Morrison, L. J., Black, S., Crnko, N. T., Shek, P. N., et al. (2009). Resuscitation with hypertonic saline-dextran reduces serum biomarker levels and correlates with outcome in severe traumatic brain injury patients. J. Neurotrauma 26 (8), 1227–1240. doi:10.1089/neu.2008.0868

Balducci, C., Santamaria, G., La Vitola, P., Brandi, E., Grandi, F., Viscomi, A. R., et al. (2018). Doxycycline counteracts neuroinflammation restoring memory in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Neurobiol. Aging 70, 128–139. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.06.002

Begemann, M., Leon, M., van der Horn, H. J., van der Naalt, J., and Sommer, I. (2020). Drugs with anti-inflammatory effects to improve outcome of traumatic brain injury: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 16179. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-73227-5

Bhatti, J., Nascimento, B., Akhtar, U., Rhind, S. G., Tien, H., Nathens, A., et al. (2018). Systematic review of human and animal studies examining the efficacy and safety of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) in traumatic brain injury: Impact on neurofunctional outcome and biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation. Front. Neurology 8, 744. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00744

Bogoslovsky, T., Gill, J., Jeromin, A., Davis, C., and Diaz-Arrastia, R. (2016). Fluid biomarkers of traumatic brain injury and intended context of use. Diagn. (Basel) 6 (4), 37. doi:10.3390/diagnostics6040037

Bourget, C., Adams, K. V., and Morshead, C. M. (2022). Reduced microglia activation following metformin administration or microglia ablation is sufficient to prevent functional deficits in a mouse model of neonatal stroke. J. Neuroinflammation 19 (1), 146. doi:10.1186/s12974-022-02487-x

Chaves Filho, A. J. M., Gonçalves, F., Mottin, M., Andrade, C. H., Fonseca, S. N. S., and Macedo, D. S. (2021). Repurposing of tetracyclines for COVID-19 neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations: A valid option to control SARS-CoV-2-associated neuroinflammation? J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 16 (2), 213–218. doi:10.1007/s11481-021-09986-3

Chen, G., Shi, J. X., Qi, M., Wang, H. X., and Hang, C. H. (2008). Effects of progesterone on intestinal inflammatory response, mucosa structure alterations, and apoptosis following traumatic brain injury in male rats. J. Surg. Res. 147 (1), 92–98. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2007.05.029

Chen, H., Wu, F., Yang, P., Shao, J., Chen, Q., and Zheng, R. (2019). A meta-analysis of the effects of therapeutic hypothermia in adult patients with traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care 23 (1), 396. doi:10.1186/s13054-019-2667-3

Cheng, F., Yuan, Q., Yang, J., Wang, W., and Liu, H. (2014). The prognostic value of serum neuron-specific enolase in traumatic brain injury: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 9 (9), e106680. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106680

Clark, R. S. B., Empey, P. E., Bayır, H., Rosario, B. L., Poloyac, S. M., Kochanek, P. M., et al. (2017). Phase I randomized clinical trial of N-acetylcysteine in combination with an adjuvant probenecid for treatment of severe traumatic brain injury in children. PLoS One 12 (7), e0180280. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180280

Dewan, M. C., Rattani, A., Gupta, S., Baticulon, R. E., Hung, Y. C., Punchak, M., et al. (2018). Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 130, 1080–1097. doi:10.3171/2017.10.jns17352

DiBona, V. L., Shah, M. K., Krause, K. J., Zhu, W., Voglewede, M. M., Smith, D. M., et al. (2021). Metformin reduces neuroinflammation and improves cognitive functions after traumatic brain injury. Neurosci. Res. 172, 99–109. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2021.05.007

Elewa, H. F., Hilali, H., Hess, D. C., Machado, L. S., and Fagan, S. C. (2006). Minocycline for short-term neuroprotection. Pharmacotherapy 26 (4), 515–521. doi:10.1592/phco.26.4.515

Graham, E. M., Burd, I., Everett, A. D., and Northington, F. J. (2016). Blood biomarkers for evaluation of perinatal encephalopathy. Front. Pharmacol. 7, 196. doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00196

Halbgebauer, R., Halbgebauer, S., Oeckl, P., Steinacker, P., Weihe, E., Schafer, M. K., et al. (2022). Neurochemical monitoring of traumatic brain injury by the combined analysis of plasma beta-synuclein, NfL, and GFAP in polytraumatized patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (17), 9639. doi:10.3390/ijms23179639

Hawryluk, G., Rubiano Escobar, A., Totten, A., O'Reilly, C., Ullman, J., Bratton, S., et al. (2020). Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury: 2020 update of the decompressive craniectomy recommendations. Neurosurgery 87, 427–434. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyaa278

Hesami, O., Iranshahi, S., Shahamati, S. Z., Sistanizd, M., Pourheidar, E., and Hassanpour, R. (2022). The evaluation of the neuroprotective effect of a single high-dose vitamin D(3) in patients with moderate ischemic stroke. Stroke Res. Treat. 2022, 8955660. doi:10.1155/2022/8955660

Hier, D. B., Obafemi-Ajayi, T., Thimgan, M. S., Olbricht, G. R., Azizi, S., Allen, B., et al. (2021). Blood biomarkers for mild traumatic brain injury: A selective review of unresolved issues. Biomark. Res. 9 (1), 70. doi:10.1186/s40364-021-00325-5

Higgins, J. P., and Altman, D. G. (2008). “Assessing risk of bias in included studies,” in Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, 187–241.

Hukkelhoven, C. W., Steyerberg, E. W., Rampen, A. J., Farace, E., Habbema, J. D., Marshall, L. F., et al. (2003). Patient age and outcome following severe traumatic brain injury: An analysis of 5600 patients. J. Neurosurg. 99 (4), 666–673. doi:10.3171/jns.2003.99.4.0666

Iyer, V. N., Mandrekar, J. N., Danielson, R. D., Zubkov, A. Y., Elmer, J. L., and Wijdicks, E. F. M. (2009). Validity of the FOUR score coma scale in the medical intensive care unit. Mayo Clin. Proc. 84 (8), 694–701. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60519-3

Jacquens, A., Needham, E. J., Zanier, E. R., Degos, V., Gressens, P., and Menon, D. (2022). Neuro-inflammation modulation and post-traumatic brain injury lesions: From bench to bed-side. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (19), 11193. doi:10.3390/ijms231911193

Jha, R. M., Kochanek, P. M., and Simard, J. M. (2019). Pathophysiology and treatment of cerebral edema in traumatic brain injury. Neuropharmacology 145, 230–246. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.08.004

Khan, S., Ali, A. S., Kadir, B., Ahmed, Z., and Di Pietro, V. (2021). Effects of memantine in patients with traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Trauma Care 1 (1), 1–14. doi:10.12968/hmed.2021.0467

Khatri, N., Thakur, M., Pareek, V., Kumar, S., Sharma, S., and Datusalia, A. K. (2018). Oxidative stress: Major threat in traumatic brain injury. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 17 (9), 689–695. doi:10.2174/1871527317666180627120501

Koulaeinejad, N., Haddadi, K., Ehteshami, S., Shafizad, M., Salehifar, E., Emadian, O., et al. (2019). Effects of minocycline on neurological outcomes in patients with acute traumatic brain injury: A pilot study. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 18 (2), 1086–1096. doi:10.22037/ijpr.2019.1100677

Langham, J., Goldfrad, C., Teasdale, G., Shaw, D., and Rowan, K. (2003). Calcium channel blockers for acute traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003 (4), CD000565. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000565

Lee, J., Cho, Y., Choi, K. S., Kim, W., Jang, B. H., Shin, H., et al. (2019). Efficacy and safety of erythropoietin in patients with traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 37 (6), 1101–1107. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.08.072

Lei, B., Mace, B., Dawson, H. N., Warner, D. S., Laskowitz, D. T., and James, M. L. (2014). Anti-inflammatory effects of progesterone in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated BV-2 microglia. PLoS One 9 (7), e103969. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103969

Li, Z. M., Xiao, Y. L., Zhu, J. X., Geng, F. Y., Guo, C. J., Chong, Z. L., et al. (2016). Recombinant human erythropoietin improves functional recovery in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: A randomized, double blind and controlled clinical trial. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 150, 80–83. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.09.001

Liu, C., Huang, C., Xie, J., Li, H., Hong, M., Chen, X., et al. (2020a). Potential efficacy of erythropoietin on reducing the risk of mortality in patients with traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 7563868. doi:10.1155/2020/7563868

Liu, M., Wang, A. J., Chen, Y., Zhao, G., Jiang, Z., Wang, X., et al. (2020b). Efficacy and safety of erythropoietin for traumatic brain injury. BMC Neurol. 20 (1), 399. doi:10.1186/s12883-020-01958-z

Lorente, L. (2017). Biomarkers associated with the outcome of traumatic brain injury patients. Brain Sci. 7 (11), 142. doi:10.3390/brainsci7110142

Lu, J., Gary, K. W., Neimeier, J. P., Ward, J., and Lapane, K. L. (2012). Randomized controlled trials in adult traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 26 (13-14), 1523–1548. doi:10.3109/02699052.2012.722257

Ma, J., Huang, S., Qin, S., You, C., and Zeng, Y. (2016). Progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12 (12), Cd008409. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008409.pub4

Mahmoodpoor, A., Shokouhi, G., Hamishehkar, H., Soleimanpour, H., Sanaie, S., Porhomayon, J., et al. (2018). A pilot trial of l-carnitine in patients with traumatic brain injury: Effects on biomarkers of injury. J. Crit. Care 45, 128–132. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.01.029

Mahyudanil, M., Bajamal, A. H., Sembiring, R. J., and Dharmajaya, R. (2020). The effect of progesterone therapy in severe traumatic brain injury patients on serum levels of s-100β, interleukin 6, and aquaporin-4. Open Access Macedonian J. Med. Sci. 8, 236–244. doi:10.3889/OAMJMS.2020.3974

Malek, A. J., Robinson, B. D., Hitt, A. R., Shaver, C. N., Tharakan, B., and Isbell, C. L. (2020). Doxycycline improves traumatic brain injury outcomes in a murine survival model. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 89 (3), 435–440. doi:10.1097/ta.0000000000002801

Mansour, N. O., Shama, M. A., and Werida, R. H. (2021). The effect of doxycycline on neuron-specific enolase in patients with traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 12, 20406223211024362. doi:10.1177/20406223211024362

Marzano, L. A. S., Batista, J. P. T., de Abreu Arruda, M., de Freitas Cardoso, M. G., de Barros, J. L. V. M., Moreira, J. M., et al. (2022). Traumatic brain injury biomarkers in pediatric patients: A systematic review. Neurosurg. Rev. 45 (1), 167–197. doi:10.1007/s10143-021-01588-0

Matthiesen, I., Voulgaris, D., Nikolakopoulou, P., Winkler, T. E., and Herland, A. (2021). Continuous monitoring reveals protective effects of N-acetylcysteine amide on an isogenic microphysiological model of the neurovascular unit. Small 17 (32), 2101785. doi:10.1002/smll.202101785

Mercier, E., Boutin, A., Lauzier, F., Fergusson, D. A., Simard, J.-F., Zarychanski, R., et al. (2013). Predictive value of S-100β protein for prognosis in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Br. Med. J. 346, f1757. doi:10.1136/bmj.f1757

Minagar, A., Alexander, J. S., Schwendimann, R. N., Kelley, R. E., Gonzalez-Toledo, E., Jimenez, J. J., et al. (2008). Combination therapy with interferon beta-1a and doxycycline in multiple sclerosis: An open-label trial. Archives Neurology 65 (2), 199–204. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2007.41

Mokhtari, M., Nayeb-Aghaei, H., Kouchek, M., Miri, M. M., Goharani, R., Amoozandeh, A., et al. (2018). Effect of memantine on serum levels of neuron-specific enolase and on the Glasgow coma scale in patients with moderate traumatic brain injury. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 58 (1), 42–47. doi:10.1002/jcph.980

Ng, S. Y., and Lee, A. Y. W. (2019). Traumatic brain injuries: Pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13, 528. doi:10.3389/fncel.2019.00528

Nirula, R., Diaz-Arrastia, R., Brasel, K., Weigelt, J. A., and Waxman, K. (2010). Safety and efficacy of erythropoietin in traumatic brain injury patients: A pilot randomized trial. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2010, 209848. doi:10.1155/2010/209848

Okidi, R., Ogwang, D. M., Okello, T. R., Ezati, D., Kyegombe, W., Nyeko, D., et al. (2020). Factors affecting mortality after traumatic brain injury in a resource-poor setting. BJS open 4 (2), 320–325. doi:10.1002/bjs5.50243

Plane, J. M., Shen, Y., Pleasure, D. E., and Deng, W. (2010). Prospects for minocycline neuroprotection. Archives Neurology 67 (12), 1442–1448. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.191

Quaglio, G., Gallucci, M., Brand, H., Dawood, A., and Cobello, F. (2017). Traumatic brain injury: A priority for public health policy. Lancet Neurol. 16 (12), 951–952. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30370-8

Rahimi, S., Ferdowsi, A., and Siahposht-Khachaki, A. (2020). Neuroprotective effects of metformin on traumatic brain injury in rats is associated with the AMP-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Metab. Brain Dis. 35 (7), 1135–1144. doi:10.1007/s11011-020-00594-3

Ramlackhansingh, A. F., Brooks, D. J., Greenwood, R. J., Bose, S. K., Turkheimer, F. E., Kinnunen, K. M., et al. (2011). Inflammation after trauma: Microglial activation and traumatic brain injury. Ann. Neurology 70 (3), 374–383. doi:10.1002/ana.22455

Ray, S. K., Dixon, C. E., and Banik, N. L. (2002). Molecular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of traumatic brain injury. Histol. Histopathol. 17 (4), 1137–1152. doi:10.14670/hh-17.1137

Santa-Cecília, F. V., Leite, C. A., Del-Bel, E., and Raisman-Vozari, R. (2019). The neuroprotective effect of doxycycline on neurodegenerative diseases. Neurotox. Res. 35 (4), 981–986. doi:10.1007/s12640-019-00015-z

Saw, M. M., Chamberlain, J., Barr, M., Morgan, M. P., Burnett, J. R., and Ho, K. M. (2014). Differential disruption of blood-brain barrier in severe traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care 20 (2), 209–216. doi:10.1007/s12028-013-9933-z

Schober, M. E., Requena, D. F., and Rodesch, C. K. (2018). EPO improved neurologic outcome in rat pups late after traumatic brain injury. Brain Dev. 40 (5), 367–375. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2018.01.003

Seifman, M. A., Gomes, K., Nguyen, P. N., Bailey, M., Rosenfeld, J. V., Cooper, D. J., et al. (2014). Measurement of serum melatonin in intensive care unit patients: Changes in traumatic brain injury, trauma, and medical conditions. Front. Neurology 5, 237. doi:10.3389/fneur.2014.00237

Shahrokhi, N., Soltani, Z., Khaksari, M., Karamouzian, S., Mofid, B., and Asadikaram, G. (2016). The serum changes of neuron-specific enolase and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in patients with diffuse axonal injury following progesterone administration: A randomized clinical trial. Arch. Trauma Res. 5 (3), e37005. doi:10.5812/atr.37005

Shukla, D., Devi, B. I., and Agrawal, A. (2011). Outcome measures for traumatic brain injury. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 113 (6), 435–441. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.02.013

Si, D., Li, J., Liu, J., Wang, X., Wei, Z., Tian, Q., et al. (2014). Progesterone protects blood-brain barrier function and improves neurological outcome following traumatic brain injury in rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 8 (3), 1010–1014. doi:10.3892/etm.2014.1840

Silva, I., Alípio, C., Pinto, R., and Mateus, V. (2021). Potential anti-inflammatory effect of erythropoietin in non-clinical studies in vivo: A systematic review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 139, 111558. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111558

Simon, D. W., McGeachy, M. J., Bayır, H., Clark, R. S. B., Loane, D. J., and Kochanek, P. M. (2017). The far-reaching scope of neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 13 (3), 171–191. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2017.13

Slavoaca, D., Muresanu, D., Birle, C., Rosu, O. V., Chirila, I., Dobra, I., et al. (2020). Biomarkers in traumatic brain injury: New concepts. Neurol. Sci. 41 (8), 2033–2044. doi:10.1007/s10072-019-04238-y

Solla, D. J. F., and Paiva, W. S. (2021). “Erythropoietin, progesterone, and amantadine in the management of traumatic brain injury: Current evidence,” in Traumatic brain injury: Science, practice, evidence and ethics. Editors S. Honeybul, and A. G. Kolias (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 179–185.

Synnot, A., Bragge, P., Lunny, C., Menon, D., Clavisi, O., Pattuwage, L., et al. (2018). The currency, completeness and quality of systematic reviews of acute management of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: A comprehensive evidence map. PLoS One 13 (6), e0198676. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198676

Taheri, A., Emami, M., Asadipour, E., Kasirzadeh, S., Rouini, M. R., Najafi, A., et al. (2019). A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of metformin in severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. 266 (8), 1988–1997. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09366-1

Tardiolo, G., Bramanti, P., and Mazzon, E. (2018). Overview on the effects of N-acetylcysteine in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 23 (12), 3305. doi:10.3390/molecules23123305

Thelin, E. P., Zeiler, F. A., Ercole, A., Mondello, S., Büki, A., Bellander, B. M., et al. (2017). Serial sampling of serum protein biomarkers for monitoring human traumatic brain injury dynamics: A systematic review. Front. Neurol. 8, 300. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00300

Vella, M. A., Crandall, M. L., and Patel, M. B. (2017). Acute management of traumatic brain injury. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 97 (5), 1015–1030. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2017.06.003

Wang, K. K. W., Kobeissy, F. H., Shakkour, Z., and Tyndall, J. A. (2021). Thorough overview of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 and glial fibrillary acidic protein as tandem biomarkers recently cleared by US Food and Drug Administration for the evaluation of intracranial injuries among patients with traumatic brain injury. Acute Med. Surg. 8 (1), e622. doi:10.1002/ams2.622

Wang, K. K., Yang, Z., Zhu, T., Shi, Y., Rubenstein, R., Tyndall, J. A., et al. (2018). An update on diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for traumatic brain injury. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn 18 (2), 165–180. doi:10.1080/14737159.2018.1428089

Wang, X., Zhang, J., Yang, Y., Dong, W., Wang, F., Wang, L., et al. (2013). Progesterone attenuates cerebral edema in neonatal rats with hypoxic-ischemic brain damage by inhibiting the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and aquaporin-4. Exp. Ther. Med. 6 (1), 263–267. doi:10.3892/etm.2013.1116

Yokobori, S., Hosein, K., Burks, S., Sharma, I., Gajavelli, S., and Bullock, R. (2013). Biomarkers for the clinical differential diagnosis in traumatic brain injury-a systematic review. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 19 (8), 556–565. doi:10.1111/cns.12127

Zeng, Y., Zhang, Y., Ma, J., and Xu, J. (2015). Progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 10 (10), e0140624. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140624

Zetterberg, H., and Bendlin, B. B. (2021). Biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease—Preparing for a new era of disease-modifying therapies. Mol. Psychiatry 26 (1), 296–308. doi:10.1038/s41380-020-0721-9

Zhang, Y., Zhang, T., Li, Y., Guo, Y., Liu, B., Tian, Y., et al. (2022). Metformin attenuates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats via AMPK-dependent mitophagy. Exp. Neurol. 353, 114055. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2022.114055

Zhou, L. Y., Chen, X. Q., Yu, B. B., Pan, M. X., Fang, L., Li, J., et al. (2022). The effect of metformin on ameliorating neurological function deficits and tissue damage in rats following spinal cord injury: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Neurosci. 16, 946879. doi:10.3389/fnins.2022.946879

Keywords: neuron-specific enolase, biomarkers, S100 ß, NSE, GFAP, UCHL1, memantine, metformin

Citation: Mansour NO, Elnaem MH, Abdelaziz DH, Barakat M, Dehele IS, Elrggal ME and Abdallah MS (2023) Effects of early adjunctive pharmacotherapy on serum levels of brain injury biomarkers in patients with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review of randomized controlled studies. Front. Pharmacol. 14:1185277. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1185277

Received: 13 March 2023; Accepted: 14 April 2023;

Published: 05 May 2023.

Edited by:

Marzia Soligo, National Research Council (CNR), ItalyReviewed by:

Shawn G. Rhind, Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC), CanadaCopyright © 2023 Mansour, Elnaem, Abdelaziz, Barakat, Dehele, Elrggal and Abdallah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohamed Hassan Elnaem, ZHJtZWxuYWVtQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==, bS5lbG5hZW1AdWxzdGVyLmFjLnVr;

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.