- 1School of Nursing, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of Nursing, Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, Shanghai, China

- 3Fudan University Center for Evidence-based Nursing: A Joanna Briggs Institute Center of Excellence, Shanghai, China

- 4Rory Meyers College of Nursing, New York University, New York, NY, United States

- 5Department of Infectious Disease, National Clinical Research Center for Infectious Diseases, Shenzhen Third People’s Hospital, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

- 6Faculty of Medicine, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

Objectives: With the prolongation of life span and increasing incidence of comorbidities, polypharmacy has become a challenge for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH). This review aimed to identify barriers and facilitators to maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence in people living with HIV/AIDS.

Methods: Nine electronic databases were searched for studies from 1996 to October 2021. Studies were included if they were conducted with adults living with HIV/AIDS and reported barriers and facilitators to maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence. This review presents a conceptual framework model to help understand the barriers and facilitators.

Results: Twenty-nine studies were included. The majority of publications were observational studies. Eighty specific factors were identified and further divided into five categories, including individual factors, treatment-related factors, condition-related factors, healthcare provider-related factors, and socioeconomic factors, based on the multidimensional adherence model (MAM).

Conclusion: Eighty factors associated with polypharmacy adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS were identified and grouped into five major categories. Healthcare providers can make decisions based on the five categories of relevant factors described in this paper when developing interventions to enhance polypharmacy adherence. It is recommended that medications be evaluated separately and that an overall medication evaluation be conducted at the same time to prevent inappropriate polypharmacy use.

1 Introduction

As a result of the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy (ART), the average life expectancy of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) has been greatly extended (Ghosn et al., 2018). However, due to various reasons, such as weakened immunity and aging, PLWH often have concomitant diseases and symptoms (Zhu et al., 2019). PLWH need to take a variety of medications for other diseases and conditions, in addition to ART drugs, resulting in long-term use of multiple medications (Gallardo-Anciano et al., 2019).

Polypharmacy is becoming an increasingly concerning issue in PLWH, especially among older PLWH (Guaraldi et al., 2018). There is no standard definition for polypharmacy in PLWH. Danjuma et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review and found that there were 36 definitions for polypharmacy in PLWH, most of which defined polypharmacy as the concomitant use of five or more medications, and most of which excluded ART medications. David and colleagues defined polypharmacy as the use of non-HIV drugs in addition to antiretroviral drugs (Back and Marzolini, 2020). Although the definition of polypharmacy is not unified, it is clear that polypharmacy relates to both the types of drugs used and the number of tablets.

Polypharmacy not only results in a heavy pill burden for PLWH and increases the complexity of medication regimens but also increases the risk of drug–drug interactions and hospitalization (El Moussaoui et al., 2020). Studies have shown that complex treatment regimens (Manzano-García et al., 2018), a heavy pill burden (Yager et al., 2017), and medication side effects (Krentz and Gill, 2016) are associated with lower polypharmacy adherence in PLWH. In addition, PLWH with polypharmacy often have multiple comorbidities, which aggravate the patient’s condition and psychological burden, resulting in decreased polypharmacy adherence (Manzano-García et al., 2018; Gervasoni et al., 2019). Most previous studies have reported adherence to ART medications and non-ART medications separately in PLWH with polypharmacy. Only one study from the United States reported overall medication adherence, showing that only 50% of PLWH achieved 85% adherence to multiple different medications (Zelnick et al., 2021). Non-compliance with medication can prevent patients from achieving good outcomes and increase hospitalization and mortality rates (Altice et al., 2019).

Over the past three decades, most studies on medication adherence in PLWH have focused on ART medication use while ignoring concomitant non-ART medication use, which is increasingly important and prevalent in PLWH (Paramesha and Chacko, 2021). Some studies have explored barriers and facilitators to maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence, but these studies focused on different factors and reached different conclusions. This scoping review aimed to identify barriers and facilitators to maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence in PLWH and develop conceptual models of polypharmacy adherence. This may be useful for the clinical development of effective intervention strategies.

2 Methods

2.1 Data sources and search strategy

A comprehensive three-step search strategy was adopted to identify relevant literature. First, a limited search was conducted in the PubMed/Medline and WanFang databases (Chinese). Second, a comprehensive search was conducted using the following electronic databases and gray literature sources: PubMed/Medline, Embase (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), Web of Science, Cochrane Library (Wiley), ProQuest Dissertations, WanFang database (Chinese), CNKI (Chinese), and SinoMed (Chinese). The search time frame was set from January 1996 to October 2021. The starting point was 1996 due to the timing of the wide application of ART in PLWH. The search strategy was tailored to the specific requirements of each database. The search strategy for all databases is available in Supplementary File S1. Finally, a manual search of the references of the included studies was performed.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they 1) aimed to explore barriers and facilitators associated with polypharmacy adherence in HIV-infected people; 2) were conducted with adults living with HIV/AIDS aged over 18 years old; and 3) were published in English or Chinese. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies were considered. Literature reviews and systematic reviews were excluded. Studies were excluded if they reported only comorbidities and not concomitant medications. Studies that included populations other than PLWH or populations with comorbid HIV infection were included if outcomes were reported separately for the subgroup with HIV infection. Studies that included populations under 18 years old were included if outcomes were reported for populations over 18 years old. We defined polypharmacy as the simultaneous use of two or more different types of medications (including or not including ART drugs) in line with the literature review results and medication characteristics of PLWH. Therefore, we further excluded studies that reported “multiple pill adherence” based only on the number of drugs, which was defined as the number of pills taken as prescribed, regardless of the types of medications.

2.3 Study selection

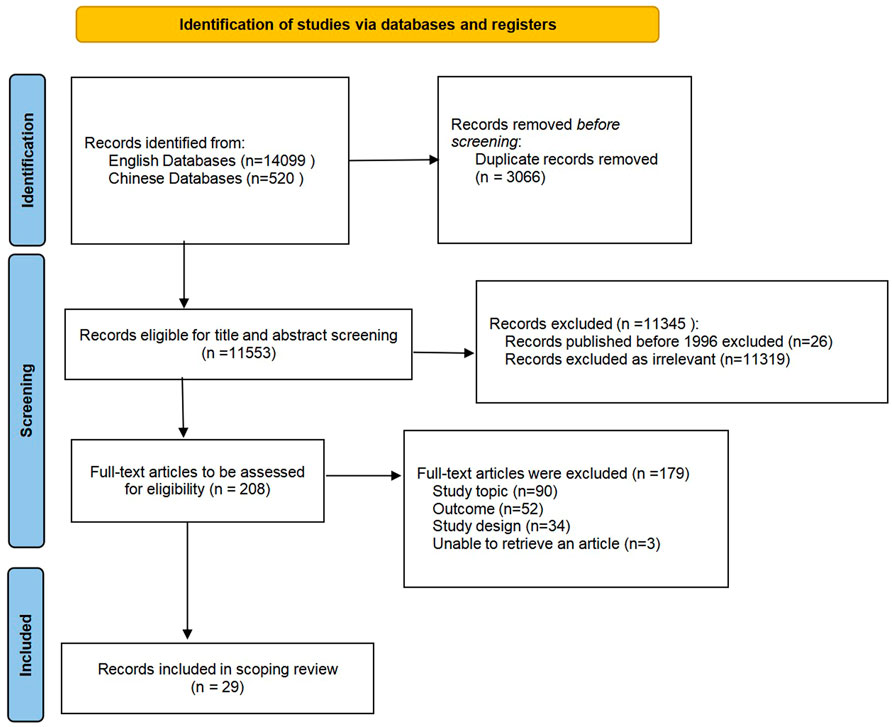

All citations were imported into Endnote X9 software (Thomson Corporation, United States), and duplicates were removed. A two-stage screening process was used to assess the relevance of studies identified in the search. First, two reviewers (JH and JY) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts according to the eligibility criteria. Second, the full texts of studies selected by both reviewers were procured for subsequent screening. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between reviewers or with the involvement of a third reviewer (ZZ). We used a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram (Figure 1) to present the search process.

2.4 Data extraction

One reviewer (JH) extracted and summarized data from the included studies, and two reviewers checked the data for accuracy (XL and MS). The collected information included the following: author, publication year, sample size, county of origin, study design, age, sex, study settings, measures of medication adherence, the threshold for measurement, barriers and facilitators associated with polypharmacy adherence, and other key findings. In addition, information regarding the effectiveness of the interventions was extracted.

2.5 Data analysis

The descriptive statistics are reported in tabular form. The barriers and facilitators from the quantitative study results were labeled with effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals. Regarding factors from the qualitative study and the discussion and summary of the quantitative study, only the relevant factors are listed.

The barriers and facilitators identified in this scoping review were based on the multidimensional adherence model (MAM) organized by the World Health Organization (WHO). The MAM is used to examine treatment adherence from multiple and holistic perspectives and is the most appropriate model for determining medication adherence (Aldan et al., 2022). The MAM framework comprises individual factors, treatment-related factors, condition-related factors, healthcare provider-related factors, and socioeconomic factors (Goh et al., 2017). We also classified all factors into four categories (Ghosn et al., 2018): barriers to maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence (Zhu et al., 2019); facilitators to maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence (Gallardo-Anciano et al., 2019); inconsistent factors; and (Guaraldi et al., 2018) non-associated factors. Identified interventions were classified into the four categories described above depending on the outcome of their effect. Although some factors did not show a significant correlation in the studies related to polypharmacy compliance in PLWH, they may also be potential non-compliance correlation factors, and further studies may be needed to explore the correlation; therefore, factors with no significant association found in the literature were also included. Our scoping review was conducted following the JBI methodology for scoping reviews and the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Peters et al., 2015; Tricco et al., 2018).

3 Results

3.1 Study identification

Figure 1 shows the study identification and selection process. A total of 14,619 records were retrieved from the electronic databases. After duplicates were removed, a total of 11,553 records remained for the screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts. Ultimately, 29 studies were deemed eligible and included in the scoping review.

3.2 Characteristics of the included studies

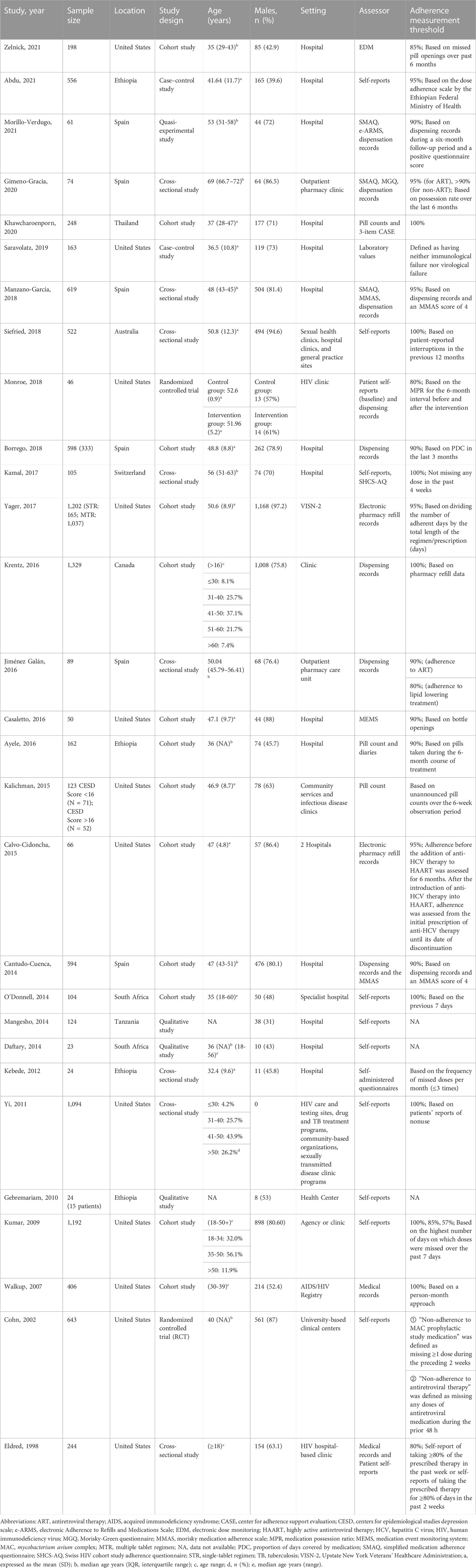

The characteristics of the 29 included studies are summarized in Table 1. There were 23 observational studies. The included studies were conducted in a wide range of locations, including five continents and nine countries. Most studies were conducted in North America (n = 13), followed by Europe (n = 7), Africa (n = 7), Oceania (n = 1), and Asia (n = 1).

The twenty-nine included studies enrolled a total of 10,744 participants (6,932 male and 3,812 female participants). The average sample size was 370, ranging from 23 to 1,329 (Daftary et al., 2014; Krentz and Gill, 2016). Of the 22 studies that reported the mean or median ages of the included population, only one included people with an average age over 65 years (Gimeno-Gracia and Sanchez-Rubio-Ferrandez, 2020), and the rest included people with median ages between 32.4 and 56 years (Kebede and Wabe, 2012; Kamal et al., 2018). Most studies were conducted in hospitals (n = 17), followed by HIV or infectious disease clinics (n = 4), agencies or communities (n = 3), multiple settings (n = 3), and outpatient pharmacy clinics (n = 2).

Polypharmacy adherence was measured by participant self-reports (n = 19), medication possession ratios (MPRs) calculated using electronic medical records or pharmacy dispensing records (n = 12), pill counts (n = 3), electronic monitoring using medication event monitoring systems (MEMS) (n = 2) and laboratory values (n = 1), as detailed in Table 1. Participants’ self-reported measurements of compliance referred to the use of questionnaire measurements, including the Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ), the Morisky-Green questionnaire/Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS), a self-developed questionnaire, and diaries (Ayele et al., 2016). Three qualitative studies obtained compliance outcomes through focus group interviews and in-depth individual interviews (Gebremariam et al., 2010; Daftary et al., 2014; Mangesho et al., 2014).

3.3 Barriers and facilitators

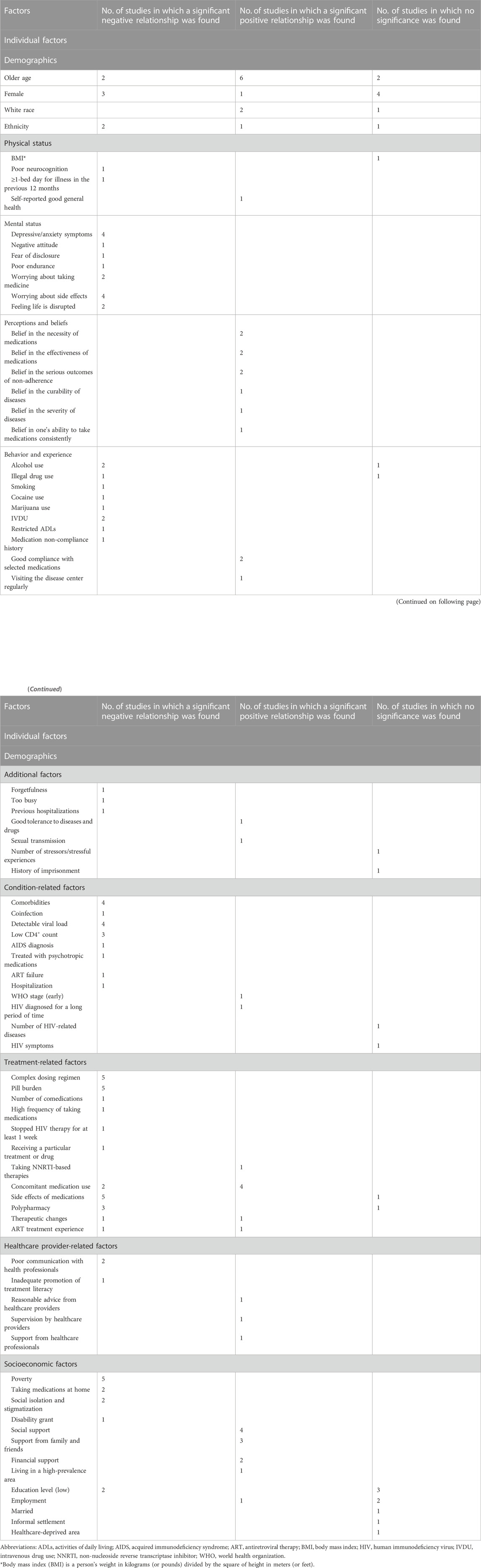

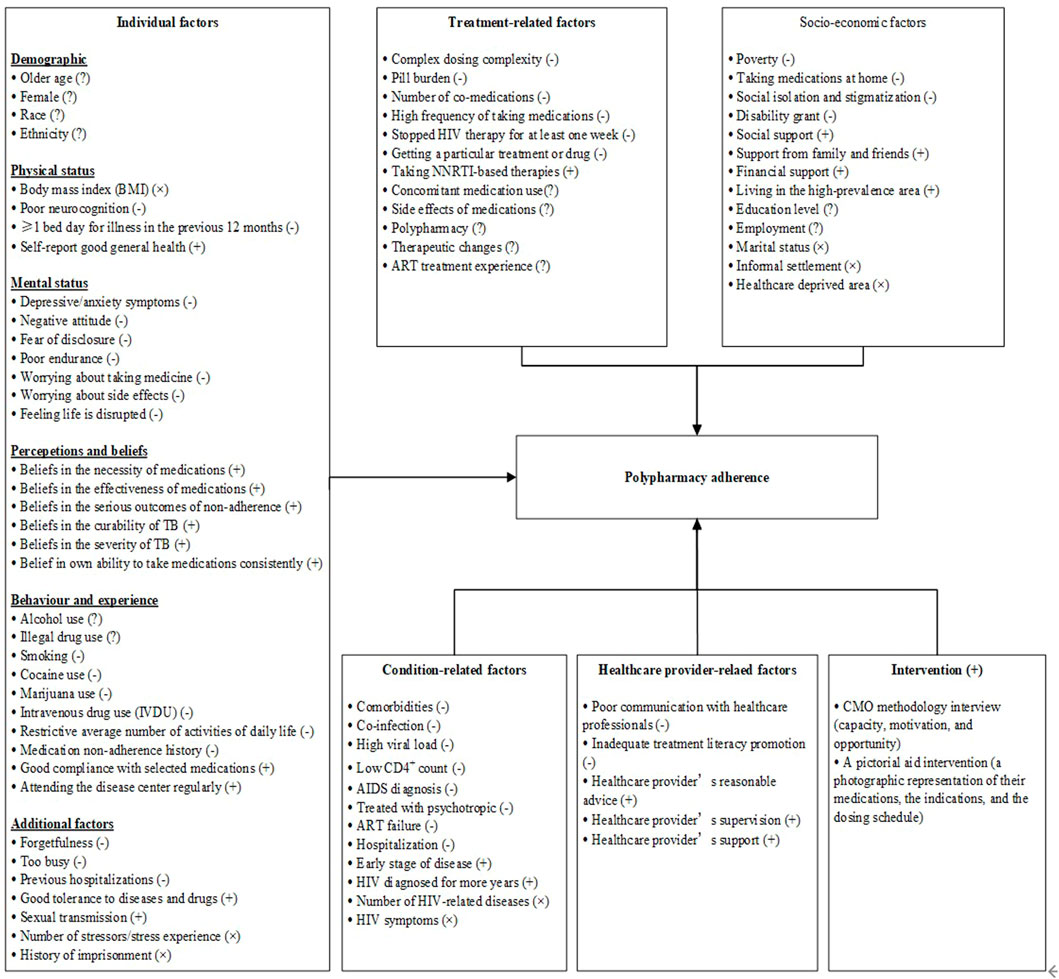

A total of 80 reviewed factors (see Supplementary Table S1) were grouped into five categories: individual factors, condition-related factors, treatment-related factors, health provider-related factors, and socioeconomic factors. Furthermore, we divided factors of compliance with polypharmacy adherence in PLWH into four categories, namely, barriers (−), facilitators (+), inconsistent factors (?), and not significantly associated factors (×), as detailed in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2. A multidimensional model for barriers and facilitators to maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence.

3.3.1 Individual factors

Individual factors were the most important factors affecting polypharmacy adherence in PLWH, as most barriers, facilitators, and inconsistent factors fell into this category. A total of thirty-eight factors from twenty-one studies were grouped into this category and could be further grouped into six subcategories (demographics, physical status, mental status, perceptions and beliefs, behavior habits, and additional factors), as detailed in Table 2.

Four factors, including age, sex, ethnicity, and race, fell into the demographics subcategory. Twelve studies reported inconsistent results regarding the relationships between demographics and polypharmacy adherence. The most complex relationship was between age and polypharmacy adherence. One study (O’Donnell et al., 2014) in South Africa showed that younger age was associated with good polypharmacy adherence (OR = 2.95; 95% CI = 0.65–13.42; p < 0.001). Another study (Gimeno-Gracia and Sanchez-Rubio-Ferrandez, 2020) in Spain reported a similar result. However, five cohort studies and one randomized controlled trial (RCT) in the United States (Cohn et al., 2002; Walkup et al., 2008; Kumar and Encinosa, 2009; Kalichman et al., 2015; Casaletto et al., 2016) and Canada (Krentz and Gill, 2016) found that older age was associated with better polypharmacy adherence (OR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.05–2.10; p = 0.05). According to the study conducted by Zelnick et al.( 2021), the relationship between age and compliance was not significant (OR: 0.76; 95% CI = 0.32–1.77; p = 0.52). Different age groups have different barriers to and facilitators of polypharmacy adherence. Therefore, when evaluating barriers to polypharmacy adherence, healthcare providers should not use age as a predictor but consider the barriers that patients in a particular age group may face and the actual situation.

Mental status was an important barrier to polypharmacy adherence at the individual factor level because the number of barriers identified in this category was the highest. Seven barriers were identified in the mental status subcategory. These barriers were reported in eight studies from the United States (Cohn et al., 2002; Kumar and Encinosa, 2009; Yi et al., 2011; Kalichman et al., 2015; Casaletto et al., 2016), Switzerland (Kamal et al., 2018), Tanzania (Mangesho et al., 2014), and Ethiopia (Gebremariam et al., 2010).

The perceptions and beliefs of PLWH were major facilitators of polypharmacy adherence at the individual factor level, with the most facilitators identified in this subcategory. Six factors that had positive associations with polypharmacy adherence were identified in this subcategory. Seven studies in the United States (Eldred et al., 1998; Cohn et al., 2002; Kalichman et al., 2015), Switzerland (Kamal et al., 2018), Tanzania (Mangesho et al., 2014), South Africa (Daftary et al., 2014), and Ethiopia (Gebremariam et al., 2010) identified six facilitators.

3.3.2 Condition-related factors

A total of thirteen factors were identified from ten studies in the condition-related factors category, including nine negative factors, two positive factors, and two irrelevant factors; these factors are presented in Table 2.

The most common factors hindering the maintenance of a high level of polypharmacy adherence were comorbidities or coinfections (n = 5), a detectable viral load (n = 4), and a lower CD4+ count (n = 3).

The influence of comorbidities on polypharmacy adherence lies mainly in the number, type, and severity of comorbidities (Krentz and Gill, 2016; Borrego et al., 2018; Manzano-García et al., 2018; Gimeno-Gracia and Sanchez-Rubio-Ferrandez, 2020). Most studies showed that comorbidities could lead to a decrease in adherence to one or more medications, especially for patients with psychiatric disorders (Walkup et al., 2008; Kumar and Encinosa, 2009). Although Encinosa and colleagues found that the number of HIV-related diseases for which medicine was taken was not associated with polypharmacy adherence, they acknowledged the impact of non-HIV comorbidities on adherence (Kumar and Encinosa, 2009). The severity of comorbidities and the perceptions of disease in PLWH will affect their judgment when receiving treatment, leading to different attitudes toward treatments for different diseases, thus causing them to give priority to some medications over others. Gebremariam et al. (2010) showed that in Ethiopia, HIV-TB coinfection caused decreased polypharmacy adherence, as some PLWH stopped TB treatment and continued ART after weighing the benefits and costs associated with the disease.

Early-stage HIV and having an HIV diagnosis for a longer period of time were facilitators of maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence (Kalichman et al., 2015; Abdu and Walelgn, 2021). Kalichman et al. showed that in Ethiopia, having been diagnosed with HIV for a longer period of time was associated with greater adherence to both ART (r: 0.20; p ≤ 0.01) and psychotropic therapy (r: 0.30; p ≤ 0.05) among PLWH (Kalichman et al., 2015).

The numbers of HIV-related diseases and HIV symptoms were not found to be significantly associated with polypharmacy adherence in two separate studies (Kumar and Encinosa, 2009; Kalichman et al., 2015). Kalichman et al. (2015) found no significant association between HIV symptoms and adherence to ART (r: 0.01; p > 0.06) and psychiatric medications (r: 0.10; p > 0.06) in PLWH in the United States.

3.3.3 Treatment-related factors

A total of twelve factors in the treatment-related factors category were identified from twenty-one studies, including six negative factors, one positive factor, and five inconsistent factors, as shown in Table 2.

The most common treatment-related factors that hindered a high level of polypharmacy adherence were complex dosing regimens (Kumar and Encinosa, 2009; Daftary et al., 2014; Jimenez Galan et al., 2016; Manzano-García et al., 2018; Gimeno-Gracia and Sanchez-Rubio-Ferrandez, 2020) and pill burden (Cohn et al., 2002; Gebremariam et al., 2010; Daftary et al., 2014; Mangesho et al., 2014; Yager et al., 2017).

Only one facilitator was identified under this category. Cantudo-Cuenca and colleagues found that PLWH undergoing non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-based therapy presented better adherence levels with the concurrent use of comedications (31.3% vs. 41.9%. p = 0.01) (Cantudo-Cuenca et al., 2014).

Five factors with inconsistent findings were identified under this category. Of these factors, the most controversial factor was the concomitant use of medications (Walkup et al., 2008; Kumar and Encinosa, 2009; Calvo-Cidoncha et al., 2015; Ayele et al., 2016; Saravolatz et al., 2019; Abdu and Walelgn, 2021). Calvo-Cidoncha et al. (2015) and Abdu and Walelgn (2021) found that the addition of anti-HCV and anti-tuberculosis therapies to ART reduced the compliance of PLWH undergoing ART. However, three studies showed that the use of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antipsychotics could improve polypharmacy compliance in PLWH with spiritual diseases (Walkup et al., 2008; Kumar and Encinosa, 2009; Saravolatz et al., 2019). Ayele et al. (2016) also found a similar result.

The second most common factor with inconsistent findings in this category was the side effects of medications. The side effects of medications, including drug–drug interactions and adverse drug reactions, were found to be barriers to maintaining high levels of polypharmacy adherence in five studies in Spain (Cantudo-Cuenca et al., 2014; Gimeno-Gracia and Sanchez-Rubio-Ferrandez, 2020), Canada (Krentz and Gill, 2016), South Africa (Daftary et al., 2014), and Ethiopia (Gebremariam et al., 2010). Kalichman et al. (2015) showed that medication side effects had no statistically significant correlation with adherence to ART (r: 0.01; p > 0.06) or psychiatric disorders (r: 0.12; p > 0.06) in PLWH. However, we feel this may be the exception rather than the rule, as most other studies have found that medication side effects were associated with non-compliance.

The third most common factor with inconsistent findings was polypharmacy. A study conducted in Spain by Gimeno-Gracia and Sanchez-Rubio-Ferrandez (2020) found that polypharmacy (defined as the simultaneous use of six or more medications) was a barrier to compliance. Studies conducted by Krentz and Gill (2016) in Canada and by Cantudo-Cuenca et al. (2014) in Spain showed consistent results, although they defined polypharmacy as the simultaneous use of five or more different types of medications daily. Another study conducted in Thailand, which defined polypharmacy as the simultaneous use of five or more non-ART drugs, showed no significant association between polypharmacy and poor adherence (Khawcharoenporn and Tanslaruk, 2020).

3.3.4 Healthcare provider-related factors

Five factors in this category were identified from three qualitative studies and are shown in Table 2. Poor communication with healthcare providers and inadequate promotion of treatment literacy were barriers to maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence in PLWH (Gebremariam et al., 2010; Daftary et al., 2014). Reasonable advice, supervision, and support from healthcare providers were facilitators of maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence in PLWH (Gebremariam et al., 2010; Daftary et al., 2014; Mangesho et al., 2014).

3.3.5 Socioeconomic factors

As shown in Table 2, thirteen factors from eighteen studies were identified in this category, including four barriers, four facilitators, two inconsistent factors, and three factors that were not significantly related.

Zelnick and colleagues found that PLWH who received a disability grant at baseline were less likely to maintain a high level of polypharmacy adherence than those who did not receive a disability grant (OR: 3.76; 95% CI = 1.20–11.86; p = 0.02) (Zelnick et al., 2021). However, we believe that the PLWH who received disability grants were disabled and thus had lower polypharmacy adherence rather than poor adherence due to receiving the grant. This is because one study showed that financial constraints reduce adherence to polypharmacy (Siefried et al., 2018).

Yi et al. (2011) found that some government-funded programs and agencies, such as the AIDS Drug Assistance Program, Medicare, and Medicaid, could promote polypharmacy adherence in the United States.

Education level and employment were two factors in this category with inconsistent results. Two studies found that a high level of education was associated with better polypharmacy adherence (Daftary et al., 2014; O’Donnell et al., 2014). However, three studies in the United States showed no significant association between education level and polypharmacy adherence (Yi et al., 2011; Kalichman et al., 2015; Zelnick et al., 2021).

3.3.6 Effect of interventions on polypharmacy adherence

In addition to the five categories mentioned above, two other interventions were effective in promoting polypharmacy adherence in PLWH. Monroe et al. (2018) found that a pictorial aid intervention (a photographic representation of the medications, indications, and dosing schedule) could improve polypharmacy adherence in PLWH compared with a standard clinic visit discharge medication list. Morillo-Verdugo and colleagues (Morillo-Verdugo et al., 2021) found that a pharmaceutical care intervention based on the capacity, motivation, and opportunity (CMO) methodology could improve primary and secondary adherence to concomitant medications and ART in PLWH.

4 Discussion

Similar to previous studies, personal factors play an important role in medication adherence in PLWH (Vervoort et al., 2007). Understanding past and current compliance of PLWH with other treatments can help predict their medication adherence in the case of polypharmacy. Additionally, interventions to improve the knowledge and motivation of PLWH to take their medications will promote compliance with multiple medications (Monroe et al., 2018; Morillo-Verdugo et al., 2021). The difference is that adherence to different medications may be different even among the same PLWH. Compliance with ART tends to be higher than that with concomitant medications in PLWH (Daftary et al., 2014; Kamal et al., 2018; O'Donnell et al., 2014; Kalichman et al., 2015). Therefore, when assessing the adherence of PLWH, healthcare professionals need to focus on individual patient factors and assess their adherence to different medications.

However, even within the same PLWH, the barriers and facilitators that affect adherence to different treatment medications are not identical. Yager et al. (2017) showed that the use of single-tablet regimens (STRs) was associated with optimal adherence to ART medications but was not directly associated with adherence to non-ART medications. Yi et al. (2011) showed that AIDS Drug Assistant Program (ADAP) enrollment had a better effect on ART medication adherence than on hypertensive medication adherence. Therefore, when assessing barriers to polypharmacy adherence in PLWH, it is necessary to evaluate the adherence to each prescribed drug individually as well as to all drugs collectively.

We found that unlike in PLWH undergoing only ART or the general population, in patients with polypharmacy, non-ART medications affect adherence to ART drug therapy and vice versa (Monroe et al., 2018; Siefried et al., 2018). The factors influencing adherence to polypharmacy in HIV-infected patients are more complex than those in the general population. Previous studies have found that concomitant medication use decreases patient medication adherence, but this study reported inconsistent factors (Mills et al., 2006; Vervoort et al., 2007). The effect of polypharmacy and concomitant medication use on medication compliance depends on the type, quantity, and regimen of the medications (Kumar and Encinosa, 2009; Manzano-García et al., 2018). On the one hand, several studies have shown that the use of antidepressant and anti-anxiety drugs significantly increased the compliance of PLWH taking ART and psychotropic medications (Walkup et al., 2008; Kumar and Encinosa, 2009; Kalichman et al., 2015; Saravolatz et al., 2019). On the other hand, the use of multidrug therapy or concomitant drugs can hinder compliance by increasing the complexity of the medication regimen, pill burden, and risk of drug–drug interactions in PLWH (Calvo-Cidoncha et al., 2015; Abdu and Walelgn, 2021). For example, a study conducted in the United States by Calvo-Calvo-Cidoncha et al. (2015) showed that the addition of anti-hepatitis C (HCV) virus therapy to ART reduced compliance with ART drugs because the addition of anti-HCV therapy greatly increased the complexity of the overall medication regimen. Medications should be evaluated separately, and an overall medication evaluation should be conducted simultaneously to prevent inappropriate polypharmacy use from reducing polypharmacy adherence.

To our knowledge, this review is the first comprehensive synthesis of studies exploring factors associated with polypharmacy adherence in PLWH. This model can help healthcare providers and caregivers of PLWH predict polypharmacy adherence from many aspects, thus helping them provide appropriate interventions at reasonable times. Therapeutic decisions at the hospital, community and administrative levels regarding the medication burden of PLWH should be more nuanced, considering both treatment factors and individual affordability and compliance with the medication burden. However, the conclusions and significance of different studies vary greatly from region to region, so medical workers in different regions should consider the application of various interventions based on the actual local situation.

Although this is the first review of all factors affecting polypharmacy adherence in PLWH, there are still several limitations. First, a weakness of this study is that it was a scoping review and not a meta-analysis of the effects of various barriers and facilitators. It is difficult to determine the degree of influence of different factors due to the small number of studies and considerable heterogeneity among studies. Second, it is difficult to set a prescribed compliance threshold for the integration of all included studies, and instead, we used the optimal compliance thresholds of the individual studies. Third, we excluded studies of patients under the age of 18 years when searching the literature, which may have resulted in missing data from some of the studies that included adults.

Several points should be noted when interpreting our results. Most studies only focus on specific comorbidities or concomitant medication use in PLWH, so there is no overall situation of polypharmacy in PLWH. The included studies only focused on certain chronic complications or coinfections and lacked research on the overall combined treatment of PLWH. This gives researchers and health providers a hint that the creation of a comorbidity network to better understand comorbidities and polypharmacy in PLWH may be possible (Zhu et al., 2021). The lack of a consistent definition of polypharmacy introduces difficulties in identifying the relevant factors not only to research but also to users. Future research needs to focus on developing a unified, relevant definition of polypharmacy. Most of the studies included in this review were observational studies, and there is a lack of research on interventions in PLWH.

5 Conclusion

Eighty factors associated with polypharmacy adherence among PLWH were identified and grouped into five major categories, including individual factors, treatment-related factors, condition-related factors, healthcare provider-related factors, and socioeconomic factors. Healthcare providers can make decisions based on the five categories of relevant factors described in this paper when developing interventions to enhance polypharmacy adherence in PLWH. We recommend evaluating medications separately and conducting an overall evaluation of medications at the same time to prevent inappropriate polypharmacy use that could decrease polypharmacy adherence. Hospital-, community- and administrative-level therapeutic decision-making regarding the medication burden of PLWH should be more nuanced, taking treatment factors and individual affordability and polypharmacy adherence into consideration.

Author contributions

JH, ZZ, and HL developed the initial concept for the manuscript, designed the review, performed the literature search, led inclusion decisions and data abstraction, created figures and tables, interpreted the literature and led the writing of the manuscript. MS, XL, and JY participated in inclusion decisions, data abstraction and the revision of the manuscript. LZ participated in writing and the revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Sailing Program (grant number 20YF1401800), China Medical Board Open Competition Program (grant number #20-372), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72104051), and Medical Innovation Research Special Project of the Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan Program (grant number 20MC1920100).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1013688/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdu, M., and Walelgn, B. (2021). Determinant factors for adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adult HIV patients at dessie referral hospital, South wollo, northeast Ethiopia: A case-control study. AIDS Res. Ther. 18 (1), 39. doi:10.1186/s12981-021-00365-9

Aldan, G., Helvaci, A., Ozdemir, L., Satar, S., and Ergun, P. (2022). Multidimensional factors affecting medication adherence among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 31 (9-10), 1202–1215. doi:10.1111/jocn.15976

Altice, F., Evuarherhe, O., Shina, S., Carter, G., and Beaubrun, A. C. (2019). Adherence to HIV treatment regimens: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence 13, 475–490. doi:10.2147/PPA.S192735

Ayele, H. T., van Mourik, M. S. M., and Bonten, M. J. M. (2016). Predictors of adherence to isoniazid preventive therapy in people living with HIV in Ethiopia. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 20 (10), 1342–1347. doi:10.5588/ijtld.15.0805

Back, D., and Marzolini, C. (2020). The challenge of HIV treatment in an era of polypharmacy. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 23 (2), e25449. doi:10.1002/jia2.25449

Borrego, Y., Gomez-Fernandez, E., Jimenez, R., Cantudo, R., Almeida-Gonzalez, C. V., and Morillo, R. (2018). Predictors of primary non-adherence to concomitant chronic treatment in HIV-infected patients with antiretroviral therapy. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 25 (3), 127–131. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-001000

Calvo-Cidoncha, E., Gonzalez-Bueno, J., Almeida-Gonzalez, C. V., and Morillo-Verdugo, R. (2015). Influence of treatment complexity on adherence and incidence of blips in HIV/HCV coinfected patients. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 21 (2), 153–157. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.2.153

Cantudo-Cuenca, M. R., Jiménez-Galán, R., Almeida-Gonzalez, C. V., and Morillo-Verdugo, R. (2014). Concurrent use of comedications reduces adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 20 (8), 844–850. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.8.844

Casaletto, K. B., Kwan, S., Montoya, J. L., Obermeit, L. C., Gouaux, B., Poquette, A., et al. (2016). Predictors of psychotropic medication adherence among HIV+ individuals living with bipolar disorder. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 51 (1), 69–83. doi:10.1177/0091217415621267

Cohn, S. E., Kammann, E., Williams, P., Currier, J. S., and Chesney, M. A. (2002). Association of adherence to Mycobacterium avium complex prophylaxis and antiretroviral therapy with clinical outcomes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34 (8), 1129–1136. doi:10.1086/339542

Daftary, A., Padayatchi, N., and O'Donnell, M. (2014). Preferential adherence to antiretroviral therapy over tuberculosis treatment: A qualitative study of drug-resistant TB/HIV co-infected patients in South Africa. Glob. Public Health 9 (9), 1107–1116. doi:10.1080/17441692.2014.934266

Danjuma, M. I., Khan, S., Wahbeh, F., Naseralallah, L. M., and Elzouki, A. (2020) What is polypharmacy in people living with HIV/AIDS? A systematic review. Version: 1. Aids res ther

El Moussaoui, M., Lambert, I., Maes, N., Sauvage, A-S., Frippiat, F., Meuris, C., et al. (2020). Evolution of drug interactions with antiretroviral medication in people with HIV. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 7, ofaa416. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaa416

Eldred, L. J., Wu, A. W., Chaisson, R. E., and Moore, R. D. (1998). Adherence to antiretroviral and Pneumocystis prophylaxis in HIV disease. J. Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 18 (2), 117–125. doi:10.1097/00042560-199806010-00003

Gallardo-Anciano, J., Gonzalez-Perez, Y., Calvo-Araguete, M. E., and Blanco-Ramos, J. R. Aging with HIV: Optimising pharmacotherapy beyond interactions. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2019;26. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2019-eahpconf.232

Gebremariam, M. K., Bjune, G. A., and Frich, J. C. (2010). Barriers and facilitators of adherence to TB treatment in patients on concomitant TB and HIV treatment: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 10, 651. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-651

Gervasoni, C., Formenti, T., and Cattaneo, D. (2019). Management of polypharmacy and drug–drug interactions in HIV patients: A 2-year experience of a multidisciplinary outpatient clinic. AIDS Rev. 21 (1), 40–49. doi:10.24875/AIDSRev.19000035

Ghosn, J., Taiwo, B., Seedat, S., Autran, B., and KatlamaLancet, C. H. I. V. (2018). Lancet 392 (10148), 685–697. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31311-4

Gimeno-Gracia, M., and Sanchez-Rubio-Ferrandez, J. (2020). Prevalence of polypharmacy and pharmacotherapy complexity in elderly people living with HIV in Spain. POINT study. Farm Hosp. 44 (4), 127–134. doi:10.7399/fh.11367

Goh, X. T., Tan, Y. B., Thirumoorthy, T., and Kwan, Y. H. (2017). A systematic review of factors that influence treatment adherence in paediatric oncology patients. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 42 (1), 1–7. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12441

Guaraldi, G., Malagoli, A., Calcagno, A., Mussi, C., Celesia, B. M., Carli, F., et al. (2018). The increasing burden and complexity of multi-morbidity and polypharmacy in geriatric HIV patients: A cross sectional study of people aged 65-74 years and more than 75 years. BMC Geriatr. 18 (1), 99. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0789-0

Jimenez Galan, R., Montes Escalante, I. M., and Morillo Verdugo, R. (2016). Influence of pharmacotherapy complexity on compliance with the therapeutic objectives for HIV+ patients on antiretroviral treatment concomitant with therapy for dyslipidemia. INCOFAR Project. Farm Hosp. 40 (2), 90–96. doi:10.7399/fh.2016.40.2.9932

Kalichman, S. C., Pellowski, J., Kegler, C., Cherry, C., and Kalichman, M. O. (2015). Medication adherence in people dually treated for HIV infection and mental health conditions: Test of the medications beliefs framework. J. Behav. Med. 38 (4), 632–641. doi:10.1007/s10865-015-9633-6

Kamal, S., Bugnon, O., Cavassini, M., and Schneider, M. P. (2018). HIV-infected patients' beliefs about their chronic co-treatments in comparison with their combined antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 19 (1), 49–58. doi:10.1111/hiv.12542

Kebede, A., and Wabe, N. T. (2012). Medication adherence and its determinants among patients on concomitant tuberculosis and antiretroviral therapy in Southwest Ethiopia. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 4 (2), 67–71. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.93376

Khawcharoenporn, T., and Tanslaruk, V. (2020). Does polypharmacy affect treatment outcomes of people living with HIV starting antiretroviral therapy? Int. J. STD AIDS 31 (12), 1195–1201. doi:10.1177/0956462420949798

Krentz, H. B., and Gill, M. J. (2016). The Impact of non-antiretroviral polypharmacy on the continuity of antiretroviral therapy (ART) among HIV patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS 30 (1), 11–17. doi:10.1089/apc.2015.0199

Kumar, V., and Encinosa, W. (2009). Effects of antidepressant treatment on antiretroviral regimen adherence among depressed HIV-infected patients. Psychiatr. Q. 80 (3), 131–141. doi:10.1007/s11126-009-9100-z

Mangesho, P. E., Reynolds, J., Lemnge, M., Vestergaard, L. S., and Chandler, C. I. R. (2014). Every drug goes to treat its own disease. " - a qualitative study of perceptions and experiences of taking antiretrovirals concomitantly with antimalarials among those affected by HIV and malaria in Tanzania. Malar. J. 13, 491. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-13-491

Manzano-García, M., Pérez-Guerrero, C., Alvarez de Sotomayor Paz, M., Robustillo-Cortes, M. d. L. A., and Almeida-Gonzalez, C. V. (2018). Identification of the medication regimen complexity index as an associated factor of nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment in HIV positive patients. Ann. Pharmacother. 52 (9), 862–867. doi:10.1177/1060028018766908

Mills, E. J., Nachega, J. B., Bangsberg, D. R., Singh, S., Rachlis, B., Wu, P., et al. (2006). Adherence to HAART: A systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 3 (11), e438. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438

Monroe, A. K., Pena, J. S., Moore, R. D., Chander, G., Riekert, K. A., Eakin, M. N., et al. (2018). Randomized controlled trial of a pictorial aid intervention for medication adherence among HIV-positive patients with comorbid diabetes or hypertension. AIDS Care 30 (2), 199–206. doi:10.1080/09540121.2017.1360993

Morillo-Verdugo, R., Velez-Diaz-Pallares, M., Garcia-Valdecasas, M. F-P., Fernandez-Espinola, S., Ferrandez, J. S-R., and Navarro-Ruiz, A. (2021). Grupo Trabajo Proyecto P. Application of the CMO methodology to the improvement of primary adherence to concomitant medication in people living with-HIV. The PRICMO Project. Farm Hosp. 45 (5), 247–252. doi:10.7399/fh.11673

O'Donnell, M. R., Wolf, A., Werner, L., Horsburgh, C. R., and Padayatchi, N. (2014). Adherence in the treatment of patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV in South Africa: A prospective cohort study. J. Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 67 (1), 22–29. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000221

Paramesha, A. E., and Chacko, L. K. (2021) A qualitative study to identify the perceptions of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV. Indian J Community Med. 2021;46(1):45–50. doi:10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_164_20

Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., and Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 13 (3), 141–146. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Saravolatz, S., Szpunar, S., and Johnson, L. (2019). The association of psychiatric medication use with adherence in patients with HIV. AIDS Care 31 (8), 988–993. doi:10.1080/09540121.2019.1612011

Siefried, K. J., Mao, L., Cysique, L. A., Rule, J., Giles, M. L., Smith, D. E., et al. (2018). Concomitant medication polypharmacy, interactions and imperfect adherence are common in Australian adults on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 32 (1), 35–48. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000001685

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern Med. 169 (7), 467–473. doi:10.7326/M18-0850

Vervoort, S. C., Borleffs, J. C., Hoepelman, A. I., and Grypdonck, M. H. (2007). Adherence in antiretroviral therapy: A review of qualitative studies. AIDS 21 (3), 271–281. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011cb20

Walkup, J., Wei, W., Sambamoorthi, U., and Crystal, S. (2008). Antidepressant treatment and adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among patients with AIDS and diagnosed depression. Psychiatr. Q. 79 (1), 43–53. doi:10.1007/s11126-007-9055-x

Yager, J., Faragon, J., McGuey, L., Hoye-Simek, A., Hecox, Z., Sullivan, S., et al. (2017). Relationship between single tablet antiretroviral regimen and adherence to antiretroviral and non-antiretroviral medications among veterans' affairs patients with human immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Patient Care STDS 31 (9), 370–376. doi:10.1089/apc.2017.0081

Yi, T., Cocohoba, J., Cohen, M., Anastos, K., DeHovitz, J. A., Kono, N., et al. (2011). The impact of the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) on use of highly active antiretroviral and antihypertensive therapy among HIV-infected women. J. Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 56 (3), 253–262. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820a9d04

Zelnick, J. R., Daftary, A., Hwang, C., Labar, A. S., Boodhram, R., Maharaj, B., et al. (2021). Electronic dose monitoring identifies a high-risk subpopulation in the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73 (7), e1901–e1910. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1557

Zhu, Z., Wen, H., Yang, Z., Han, S., Fu, Y., Zhang, L., et al. (2021) Evolving symptom networks in relation to HIV-positive duration among people living with HIV: A network analysis. Inter J. Infect. Dis. 108:503–509. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.05.084supplementary materials supplementary file 1: Search strategies and results

Keywords: HIV, aids, polypharmacy, adherence, scoping review

Citation: He J, Zhu Z, Sun M, Liu X, Yu J, Zhang L and Lu H (2023) Barriers and facilitators to maintaining a high level of polypharmacy adherence in people living with HIV: A scoping review. Front. Pharmacol. 14:1013688. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1013688

Received: 07 August 2022; Accepted: 21 February 2023;

Published: 02 March 2023.

Edited by:

Sue Twine, National Research Council Canada (NRC), CanadaReviewed by:

Veeranoot Nissapatorn, Walailak University, ThailandDaniela Oliveira de Melo, Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil

Copyright © 2023 He, Zhu, Sun, Liu, Yu, Zhang and Lu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongzhou Lu, bHVob25nemhvdUBmdWRhbi5lZHUuY24=; Zheng Zhu, emhlbmd6aHVAZnVkYW4uZWR1LmNu

Jiamin He

Jiamin He Zheng Zhu

Zheng Zhu Meiyan Sun2

Meiyan Sun2 Xiaoning Liu

Xiaoning Liu Hongzhou Lu

Hongzhou Lu