- 1School of Pharmacy, Key Laboratory of Hui Ethnic Medicine Modernization, Ministry of Education, Ningxia Medical University, Yinchuan, China

- 2Meishan Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Meishan, China

- 3Research Institute of Integrated TCM and Western Medicine, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, China

The Cymbopogon genus belongs to the Andropoganeae family of the family Poaceae, which is famous for its high essential oil concentration. Cymbopogon possesses a diverse set of characteristics that supports its applications in cosmetic, pharmaceuticals and phytotherapy. The purpose of this review is to summarize and connect the evidence supporting the use of phytotherapy, phytomedicine, phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology, toxicology, pharmacological activities, and quality control of the Cymbopogon species and their extracts. To ensure the successful completion of this review, data and studies relating to this review were strategically searched and obtained from scientific databases like PubMed, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, ScienceDirect, and Elsevier. Approximately 120 acceptable reviews, original research articles, and other observational studies were included and incorporated for further analysis. Studies showed that the genus Cymbopogon mainly contained flavonoids and phenolic compounds, which were the pivotal pharmacological active ingredients. When combined with the complex β-cyclodextrin, phytochemicals such as citronellal have been shown to have their own mechanism of action in inhibiting the descending pain pathway. Another mechanism of action described in this review is that of geraniol and citral phytochemicals, which have rose and lemon-like scents and can be exploited in soaps, detergents, mouthwash, cosmetics, and other products. Many other pharmacological effects, such as anti-protozoal, anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer have been discussed sequentially, along with how and which phytochemicals are responsible for the observed effect. Cymbopogon species have proven to be extremely valuable, with many applications. Its phytotherapy is proven to be due to its rich phytochemicals, obtained from different parts of the plant like leaves, roots, aerial parts, rhizomes, and even its essential oils. For herbs of Cymbopogon genus as a characteristic plant therapy, significant research is required to ensure their efficacy and safety for a variety of ailments.

Introduction

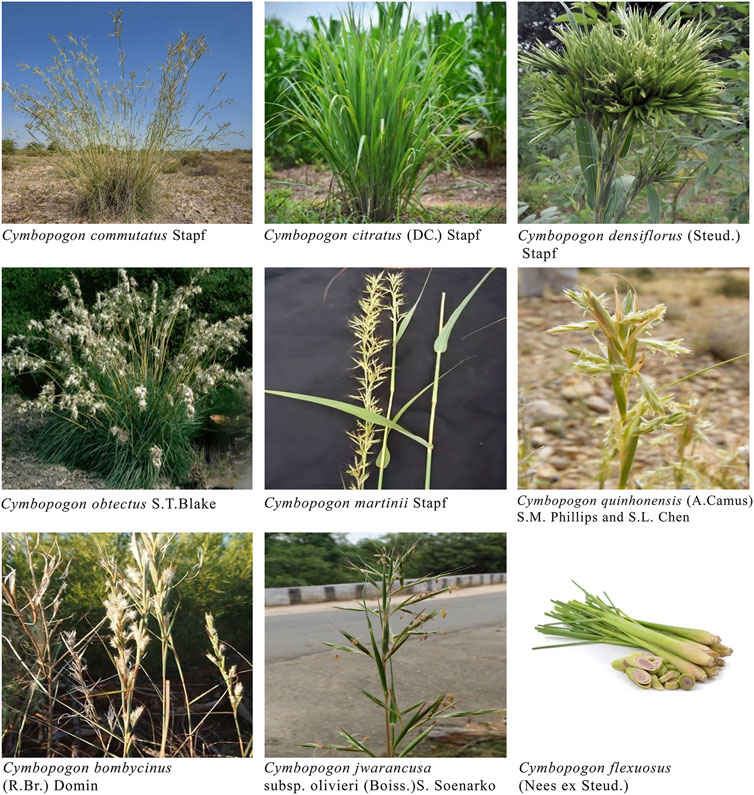

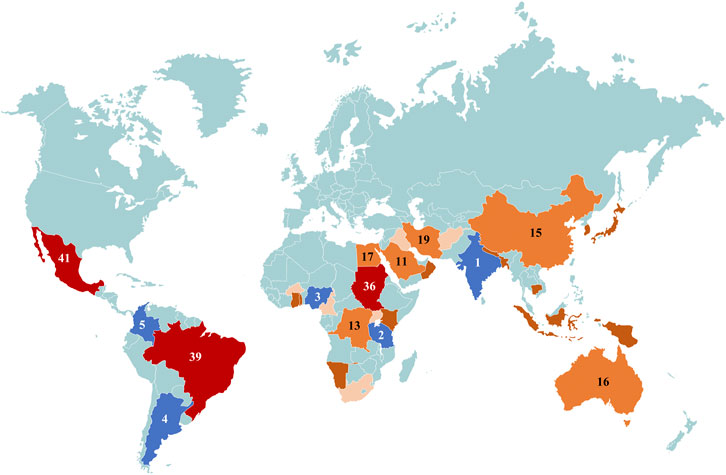

Cymbopogon is a genus with a lot of names, such as lemongrass, barbed wire grass, silky heads, Cochin grass, Malabar grass, oily heads, citronella grass, or fever grass. This grass species is widely distributed in more than 40 countries in the world (as shown in Figure 1) and is native to Asia, Africa, Australia, and tropical islands (Soenarko 1977; Toungos 2019). Cymbopogon is diverse in terms of names, species, and uses, with almost all of them being aromatic. It consists of 144 species, some of which include Cymbopogon nardus (L.) Rendle (C. nardus), Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf (C. citratus), Cymbopogon giganteus Chiov (C. giganteus), Cymbopogon flexuosus (Nees ex Steud.) W. Watson (C. flexuous), Cymbopogon martini (Roxb.) W. Watson (C. martinii), Cymbopogon schoenanthus subsp. proximus (Hochst. ex A. Rich.) Maire & Weiller (C. schoenanthus), etc. (Table 1 and Figure 2). The distribution of these species is astonishing as some of the same species can be found in different countries, but there no conclusive evidence to indicate whether or not their chemical composition is exactly the same. For example, C. citratus can be found in Bangladesh, Brazil, Tanzania, Ghana, Guadeloupe, French West Indies, Kenya, Mauritius, Argentina, Thailand, Uganda, Nigeria, India, Mexico, Singapore, Togo, Trinidad, etc. C. nardus can be hunted in Uganda, Brazil, Mauritius, Thailand, etc. While C. giganteus can be found in Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Madagascar, etc. And C. jwarancusa can be found in Iran, Pakistan, etc (Jirovetz et al., 2007; Karami et al., 2021). The distribution of Cymbopogon species from different countries across the world is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. The distribution of Cymbopogon species from different countries across the world, with more than 10 species found in countries like India, China, Australia and countries found in East Africa.

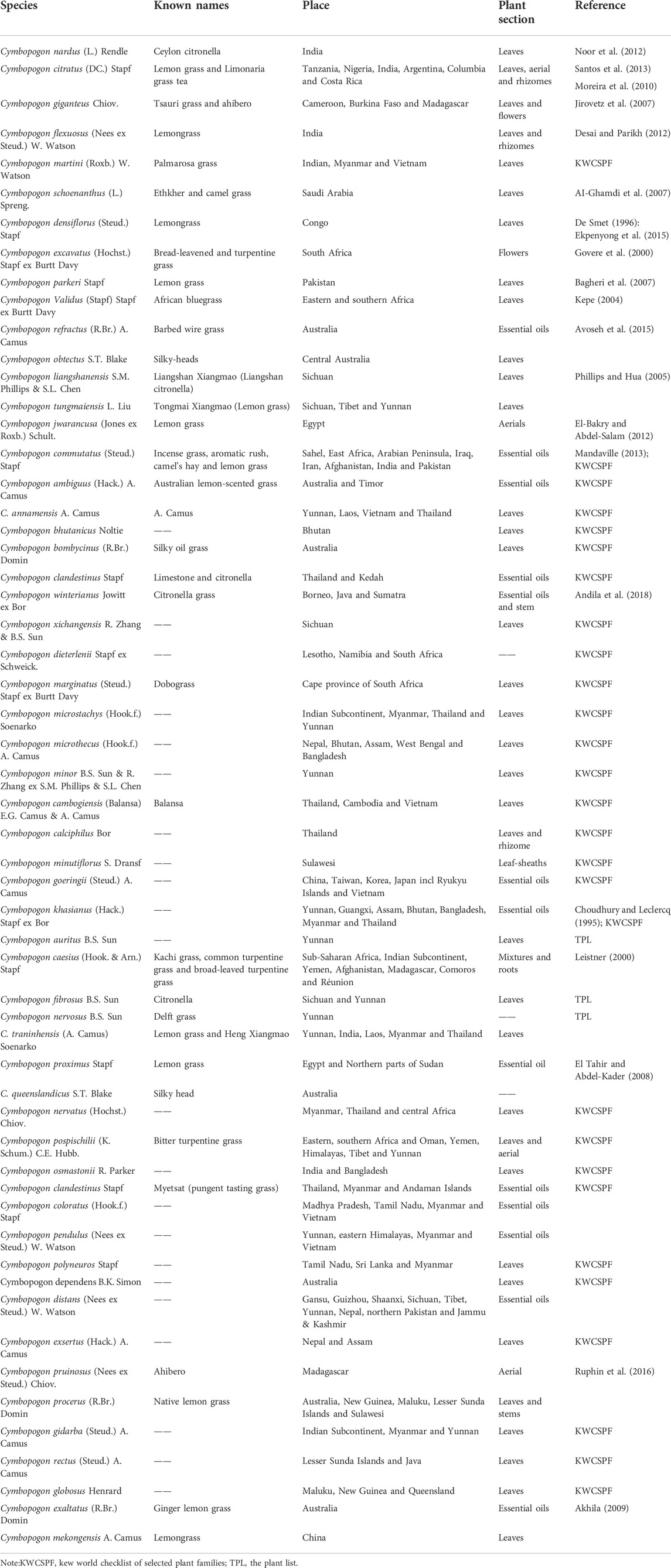

TABLE 1. Cymbopogon species and sections of the plant or essential oil are used for traditional, medicinal, and economic use.

The ethnopharmacology of Cymbopogon species has been shown to possess a diverse set of characteristics that supports their traditionally applications in cosmetic, pharmaceuticals, insect repellants, insecticides, and perfumery, mainly due to their high level of essential oils (Khanuja et al., 2005; Aibinu et al., 2007). Several findings have confirmed the nutritional value of Cymbopogon species as well as their therapeutic and pharmacological properties. Many countries in the world use this species as an herbal remedy on urinary tract infection, detoxication effects on the kidney and liver, bone diseases, hypertension, hypercholesteremia, stomach ulcers, weight loss and indigestion (Takaisi-Kikuni et al., 2000; Jirovetz et al., 2007; Francisco et al., 2011; Kpoviessi et al., 2014; Karami et al., 2021). When it comes to dosage, in countries like Tanzania, it is believed that patients with stomach ulcers can have a cup of tea of this herb half an hour before eating in the morning, afternoon, and evening. In diabetic patients, you boil the lemongrass leaves and add ginger powder and take them before dinner. The doses and how it is consumed vary in other countries, as some consume it as tea or decoction with different dosages. C. citratus is one of the most extensively employed species in the world, with pharmacological effects such as anti-inflammatory, antitrypanosomal, and stomach discomfort treatments (Francisco et al., 2011; Kpoviessi et al., 2014). Other species with antimicrobial effects include C. giganteus (Jirovetz et al., 2007), C. pendulus and C. winterianus as antifungals (Pandey et al., 1996; Oliveira-Verbel et al., 2011), C. flexuosus as a chemo preventive (Sharma et al., 2009), C. densiflorus Stapf as an antibacterial (Takaisi-Kikuni et al., 2000).

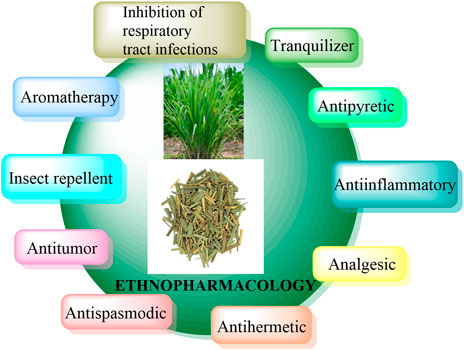

Ethnopharmacology and traditional significance

Cymbopogon species has diverse uses in different countries, contributing to the discovery of traditional medicines and commercial applications. On continents like Asia, South America, and Africa, the Cymbopogon leaves have been traditionally utilized as tea or decoction. Different parts of the Cymbopogon plant embrace key bioactive chemicals which determine the anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, anti-dyspeptic, and anti-fever actions, antispasmodic, analgesic, antipyretic, tranquilizer, anti-hermetic, and diuretic characteristics of the plant (Ademuyiwa et al., 2015; Bayala et al., 2018). In Tanzania, lemongrass tea is utilized as an anti-fever to reduce fever and is used by women to ease dysmenorrhea. The tea is also believed to clean the fallopian tubes, which facilitates easier blood flow. In Singapore, C. citratus is employed to alleviate paronychia, cold and flu symptoms, bug bites, sore and itchy throats, flatulence, indigestion, and cancer prevention (Siew et al., 2014). Interestingly, several countries also choose C. citratus as an insect repellent against mosquitos, house flies, and fleas (Boaduo et al., 2014). In India, C. flexuosus is generally accepted to treat fever, rheumatism, and cancers (Sureshkumar et al., 2017). It has been argued that the aerial parts of Cymbopogon jwarancusa (Jones ex Roxb.) Schult (C. jwarancusa) are panacea for respiratory tract infections, while its root decoction has been demonstrated to exert superior roles on dyspepsia, typhoid, and fever in children (Kadir et al., 2014). In Gabon, the crushed leaves of Cymbopogon densiflorus (Steud.) Stapf (C. densiflorus) are recognized as a treatment for rheumatism, while its flowerhead is smoked in a pipe as a remedy for bronchial discomfort and asthma in Malawi and Congo. The aerial part and root of Cymbopogon distans (Nees ex Steud.) W. Watson (C. distans) are ingeniously utilized as carminatives to prevent heart disease in Pakistan (Ullah et al., 2014). The majority of Cymbopogon essential oils are consumed in aromatherapy because of their therapeutic benefits, which aid in body rejuvenation. It can also be found in a variety of items, including perfumes, local soaps, and candles (Dutta et al., 2016). In several Asian and African countries, the leaf has been shown to have some snake and reptile repellent functions. Figure 3 summarizes some of the ethnopharmacology observed in Cymbopogon species.

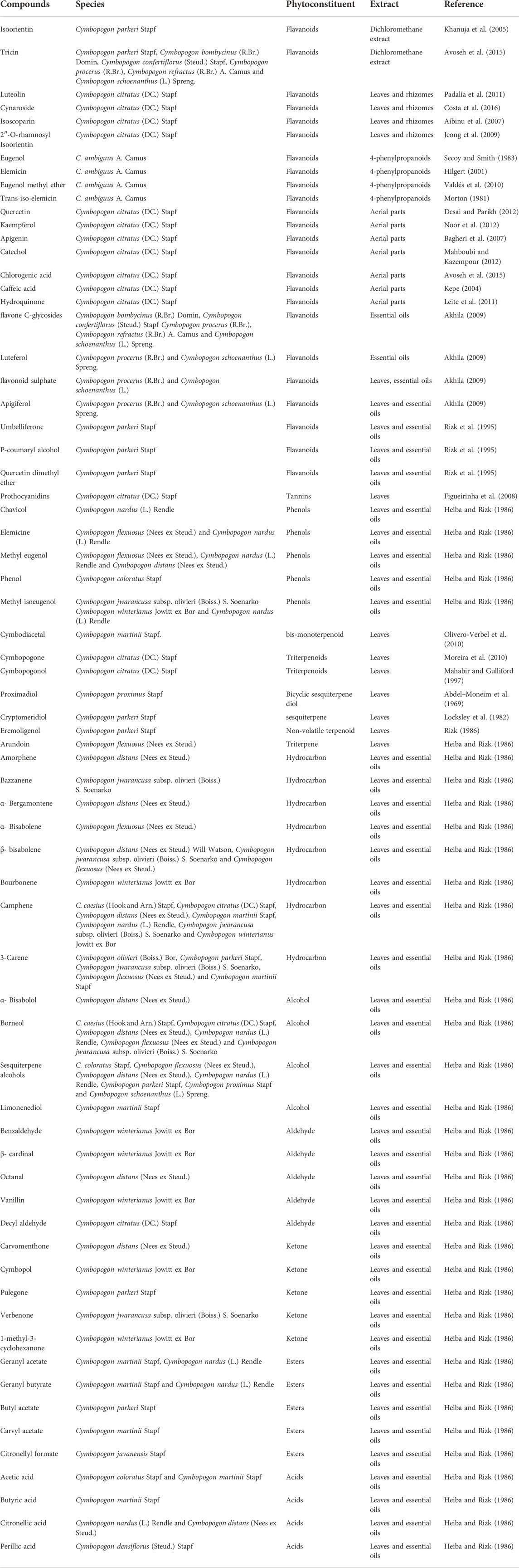

Phytochemistry

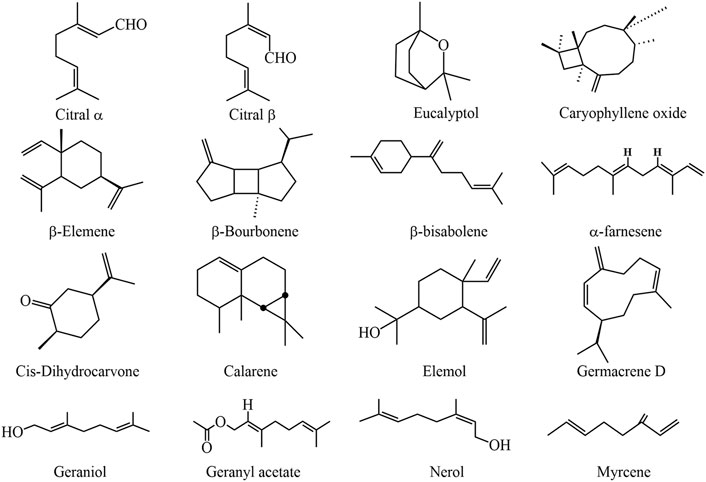

The presence of phytochemicals in medicinal herbs may be linked to their therapeutic potential. Many chemical compounds have been isolated from Cymbopogon species, including hydrocarbons, alcohols, ketones, esters, phenols (flavonoids, tannins), volatile and non-volatile terpenoids, acids, carotenoids, and other miscellaneous compounds (Table 2 and Table 3). Among which, essential oils, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenols, and tannins are the major phytoconstituents as shown in Figure 4 (Rahim et al., 2013; Avoseh et al., 2015). The chemical composition of essential oil is mainly composed of monoterpenes, monoterpenoids, sesquiterpenes, sesquiterpenoids (Figure 5), and a few fatty alcohols like 1-Octanol and 4-Nonanol (Piaru et al., 2012; Oladeji et al., 2019).

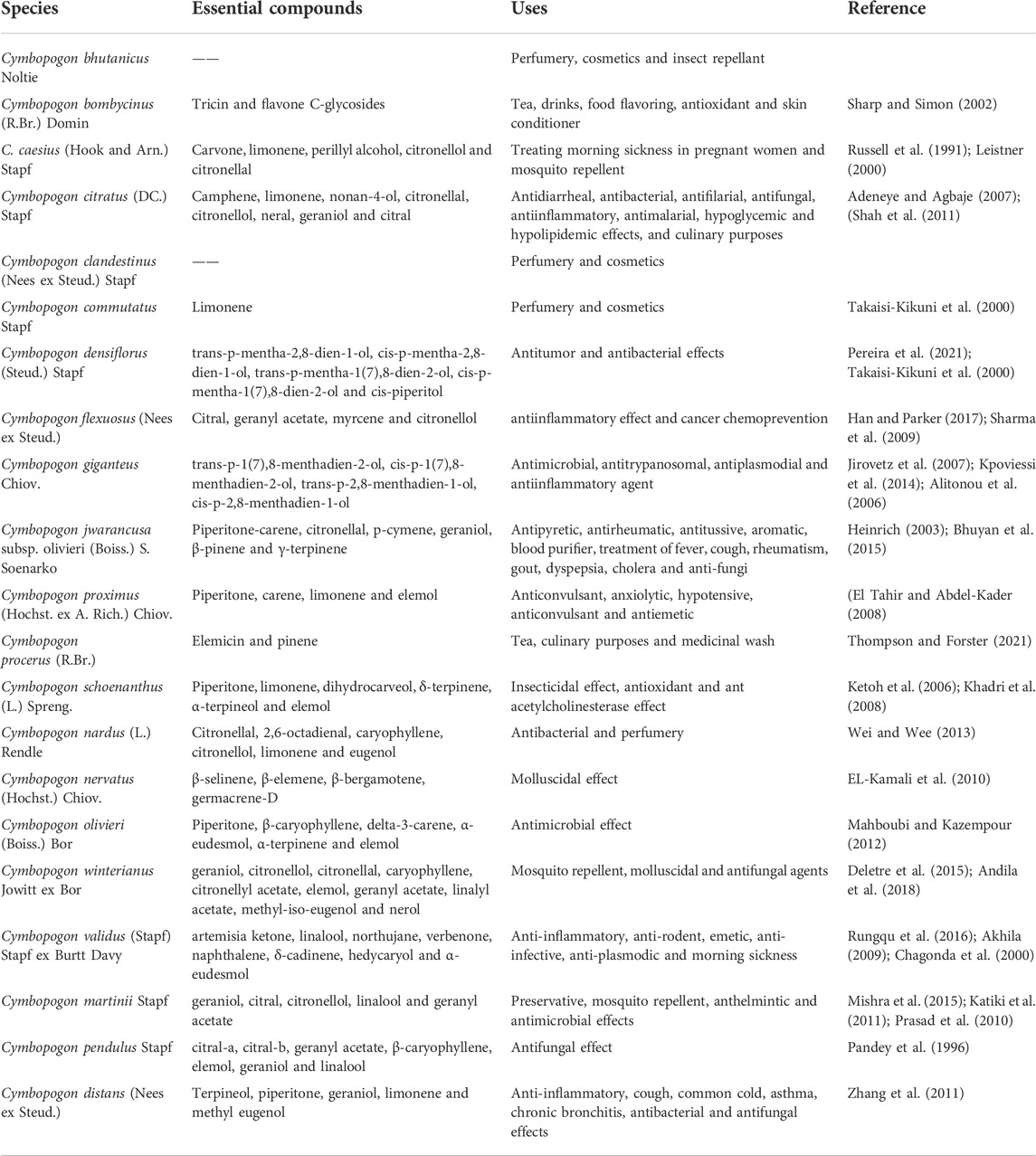

TABLE 3. Major components observed in some Cymbopogon species and their medicinal, traditional and economic uses.

FIGURE 5. The chemical structures of Cymbopogon essential oils. They include monoterpenes such as citral α, citral β, nerol, geraniol, myrcene, limonene, geranyl acetate and citronellal. Monoterpenoids: Cis-dihydrocarvone, eucalyptol. sesquiterpenes: α-farnesene, β-bisabolene, germacrene D, β-elemene, caryophyllene oxide, calarene. Monoterpene ketone: Piperitone. Sesquiterpenoids: Elemol and β-bourbonene.

Cymbopogon terpenoids

a) Non-volatile terpenoids: C. martinii produces cymbodiacetal (Olivero-Verbel et al., 2010), a new bis-monoterpenoid, whereas C. citratus leaves yield the triterpenoids cymbopogone (Moreira et al., 2010) and cymbopogonol (Mahabir and Gulliford 1997), both of which manifest as non-volatile. b) Volatile terpenoids: Volatile terpenoids are abundant in the Cymbopogon genus of different species, some of which include citral, geraniol, citronellol, piperitone, and elemin.

Flavonoids

Antioxidant characteristics were found in this family of compounds. Isoorientin and tricin were extracted from a dichloromethane extract and the whole plant of C. parkeri (Rizk et al., 1995), and their muscular relaxation activity had been determined (Rizk et al., 1986). Other flavonoid compounds like cynaroside, luteolin, isoscoparin, and 20-O-rhamnosyl isoorientin were isolated from the leaves and rhizomes of C. citrates, while apigenin, kaempferol, caffeic acid, catechol, quercetin, chlorogenic acid, hydroquinone, and elemicin were identified from the aerial parts of C. citratus (Asif and Khodadadi, 2013; Roriz et al., 2014).

Tannins

C. citratus is a Cymbopogon specie whose tannin content is heavily exploited. The species from Portugal and fractionated extracts contained about 10 mg of hydrolysable tannins (prothocyanidins) (Figueirinha et al., 2008), whereas C. citratus from Nigeria embraced about 0.6 percent tannins. Some studies have also proven the content of condensed tannins in C. nardus (Gebashe et al., 2020).

Phenol

In a particular study, total soluble phenolic content was obtained in methanolic root extracts of C. nardus, wherein it was shown that its content ranged from 4.2 to 30.9 mg GAE/g DW (milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per g). p-coumaric, ferulic, and chlorogenic acids are some of the phenolic acids isolated from the roots of C. nardus (Gebashe et al., 2020).

Essential oils

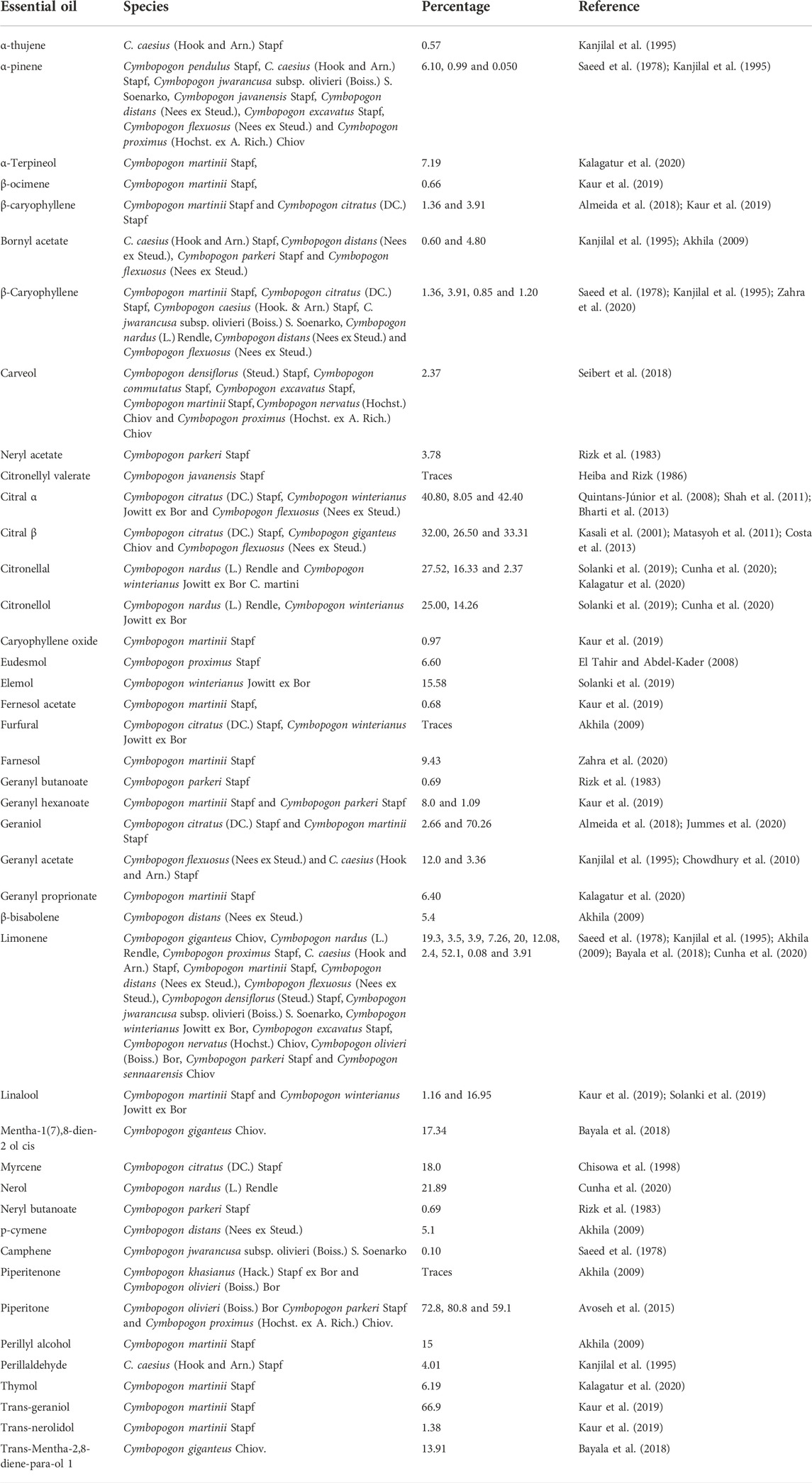

Cymbopogon essential oils are widely used in the fragrance, cosmetic, food, and flavor industries. Pain alleviation and blood sugar regulation are some of the biological effects of the oil (Dikshit 1984). The famous Cymbopogon essential oils include lemongrass oils (obtained from C. flexuosus, C. citratus, and C. pendulus), citronella oils (obtained from C. winterianus and C. nardus), palmarosa and ginger grass oils (obtained from C. martinii) (Husain 1994). Other Cymbopogon species known to produce essential oils are C. schoenanthus (camel grass), C. caesius (inchi/kachi grass), C. afronardus, C. clandestinus, C. coloratus, C. exaltatus, C. goeringii, C. giganteus, C. jwarancusa, C. polyneuros, C. procerus, C. proximus, C. rectus, C. sennaarensis, C. stipulatus, and C. virgatus (Akhila 2009). Geraniol and citral are two major constituents of the essential oil that, due to their specific rose and lemon-like aromas, are the preferred raw material for the commercial production of flavors, cosmetics, and fragrances in soaps and detergents (Ganjewala and Luthra 2010). Citral-containing species includes C. flexuosus, C. martinii, C. citratus, C. pendulus, and Cymbopogon schoenanthus. While geraniol-containing species covers in C. flexuosus, C. jwarancusa, C. martinii, C. citratus, C. pendulus, C. winterianus, C. nardus, C. caesius, C. coloratus, C. parkeri, etc. Table 4 summarizes some of the essential oils found in Cymbopogon species.

Mineral contents

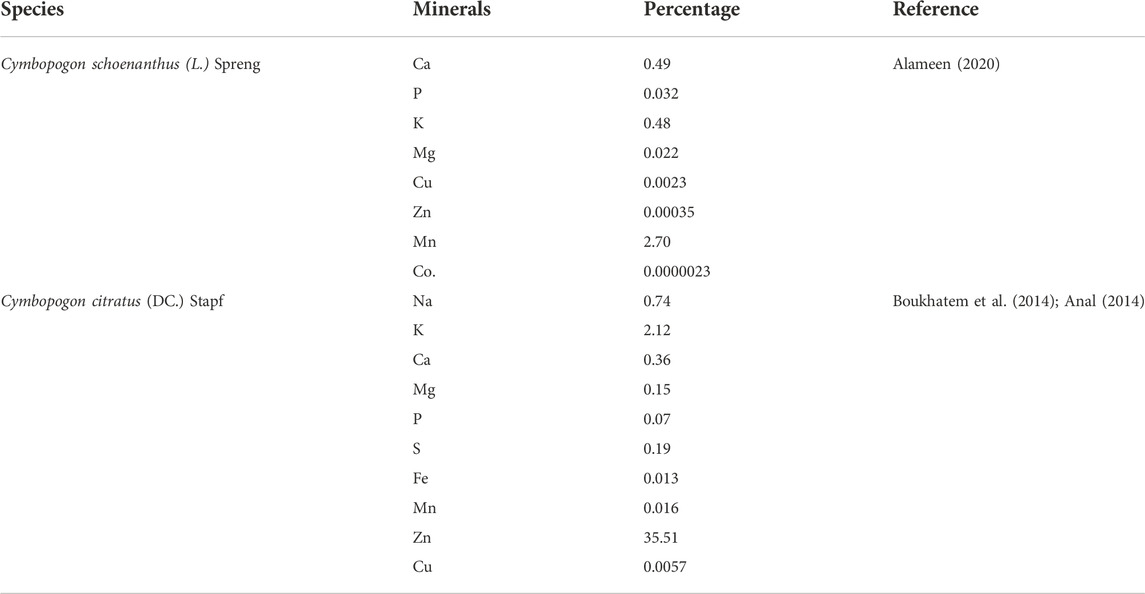

In a study performed on Cymbopogon citratus, some of the reported essential mineral constituents were potassium (K), sodium (Na), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), phytate and phosphorus (P) (Boukhatem et al., 2014). Other minerals that can be found in C. citratus include chromium (Cr), nickel (Ni), copper (Cu), arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb) (Anal 2014). Essential minerals found in Cymbopogon schonenanthus include Ca, P, K, Mg, Cu, Zn, Mn and cobalt (Co.) (Alameen 2020). The percentage of mineral content was calculated at a concentration of (mg/100 g) while in other reports the content was converted from (parts per million) ppm to percentage (as shown in Table 5).

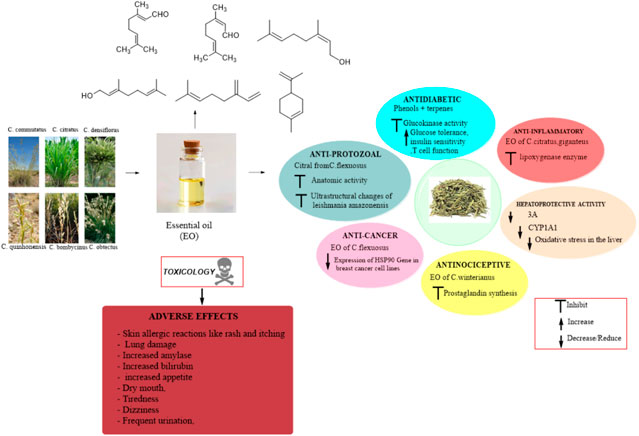

Pharmacology

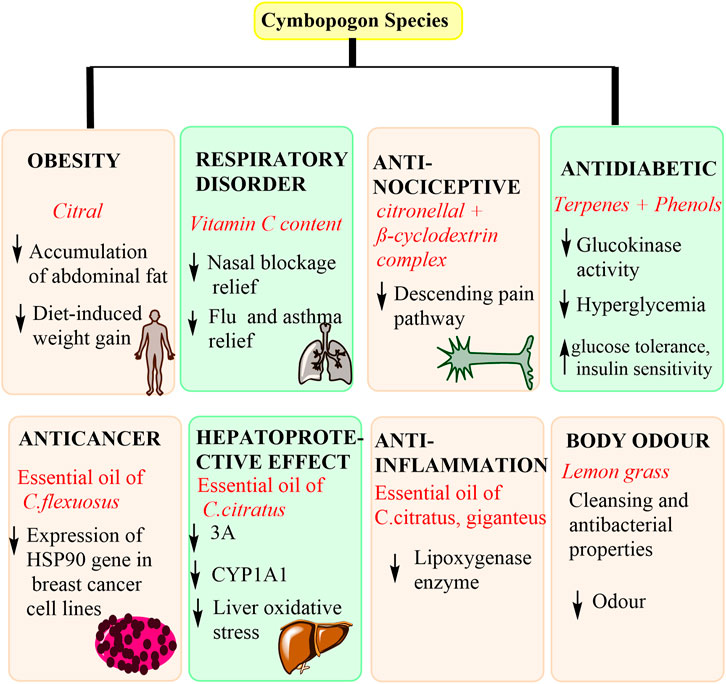

Most of the pharmacological investigations have been conducted based on the components present. These components have led to the discovery of different pharmacological effects, which are proved by the mechanism of action discovered. Figure 6 highlights some of the mechanisms of action observed in Cymbopogon species.

Antiprotozoal effect

Citral is the major component of C. citratus and C. flexuosus essential oils. According to some findings, myrcene and citral have been discovered to have an antileishmanial effect on different species like Leishmania infantum, Leishmania tropica, and Leishmania major (Ganjewala et al., 2012). Citral, on the other hand, has been shown to exert anti-trypanosoma cruzi activity (Cardoso and Soares 2010) and to inhibit the anatomic and ultrastructural changes of Leishmania amazonensis without cytotoxicity (Santin et al., 2009). In other studies, Entamoeba histolytica was shown to be active in broth culture from cymbopogon essential oil (Dutta et al., 2016).

Anti-bacterial and antifungal effect

C. citratus has been used to isolate, characterize, and analyze essential oils like citral (geranial) and citral (neral), which have been shown to be antibacterial chemicals that are active against both gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms (Soares et al., 2013). Bacterial infections like meningitis, pneumonia, impetigo, cellulitis, folliculitis and food poisoning have been treated traditionally by this herb (Ntulume et al., 2019). C. jwarancusa oil can distinctly inhibit the growth of various bacteria like Klebsiella pneumoniae, Citrobacter, Proteus mirabilis, Salmonella enteric sertyphi, and Shigella flexneri species (Prasad et al., 2014). Marvelously, myrcene has been shown to have low antibacterial activity but is very active when combined with other essential oils (Orafidiya 1993; Wannissorn et al., 2005). While the essential oil of C. martinii is reported to possess magnificent antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, S. pyagens, E. coli, and Corynebacterium ovis (Chouhan et al., 2017).

Cymbopogon oil has been affirmed to be one of the most effective anti-dermatophytes medications. Examples of dermatophytes treated by this herb include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, T. rubrum, Epidermophyton floccosum, and Microsporum gypseum (Wannissorn et al., 1996). Cymbopogon essential oils have also been corroborated to possess prominent resistance to pathogenic fungal stimulus that cause problems with mycotoxins released during grain storage and restrain filamentous fungus development by yeast cells, which has been reported to have antagonistic and synergistic effects on food storage (Nguefack et al., 2012; Kpoviessi et al., 2014). Coincidently, C. jwarancusa is proven to be extremely efficient against Fusarium oxyporium sp–lini (Dutta, Munda et al., 2016). Conformably, C. citratus can suppress fungal infections like athlete’s foot, ringworm, jock itch, yeast infections, and keratinophilic fungi (Abe et al., 2003).

Anti-cancer effect

In different studies, the essential oils of C. densiflorus and C. flexuosus were analyzed to see if they had antitumor effects. Evidence suggested that C. flexuosus oil triggered apoptosis in human leukemia cell lines (HL-60 cells) in vitro and a murine sarcoma inoculated with S-180 tumor cells in vivo. Amazedly, the greatest effect was seen on the human cancer lines of colon, liver, cervix, and neuroblastoma. The oil treatment of C. densiflorus is suggested to have antitumor effects on TP53 wild-type and mutated bladder cancer cells. These results indicate that C. flexuosus and C. densiflorus oils could be a reasonable alternative for novel antineoplastic drugs (Sharma et al., 2009; Pereira et al., 2021).

Anti-inflammatory effect

Chronic inflammation is a major worldwide health problem that has been associated with life-threatening conditions like cancer (Colotta et al., 2009). Cymbopogon’s ethnopharmacological studies have confirmed citral to have anti-inflammatory properties. The essential oil of C. flexuosus, which has high citral content, has been announced to substantially reduce numerous inflammatory biomarkers in human skin cells and conspicuously subdue chemical agents-induced skin inflammation both topically and orally in a mouse model (Han and Parker 2017). Currently, it has been widely used as an ingredient in lotions and ointments to treat topical inflammation (de Cassis da Silveira e Sa et al., 2013; Boukhatem et al., 2014).

Antimalarial and antitrypanosomal effect

The essential oils of C. giganteus, C. citratus, C. nardus, and C. schoenanthus have been shown to have an effect against Trypanosoma brucei brucei and Plasmodium falciparum. Some secondary metabolites like citral (3, 7-dimethyl-2, 6-octadienal), myrcene, and citronellal were referred to as antimalarial compounds when compared to chloroquine, as they were found to decrease Plasmodium’s growth by 86.6 percent (Melariri 2010; Arrey Tarkang et al., 2014; Kpoviessi et al., 2014). While, elemicin was declared to be present in 53.7 percent of C. pendulus essential oil. This compound is an essential starting material for the synthesis of the antimalarial drug trimethoxy prim. In another study, the ethanol extracts of C. citratus essential oil were shown to ameliorate the antioxidant state of oxidative stress-related malaria effects (Tchoumbougnang et al., 2005; Akono Ntonga et al., 2014).

Antidiabetic effect

C. nardus is indicated to be efficient in maintaining blood glucose levels despite a lack of details on its mode of action (Widiputri et al., 2019). Studies have revealed the antidiabetic potency of C. citratus at dosage rates of 400 and 800 mg, by decreasing the levels of insulin (p < 0.001), glucose (p < 0.001) and triglycerides (p < 0.001) (Bharti et al., 2013). Another report on the effect of lemongrass tea (mainly containing phenolics and terpenes) in a type 2 diabetes rat model suggested that the inhibition of glucokinase activity attributed to its antidiabetic effect, which resulted in enhancement of hyperglycemia, glucose tolerance ability, insulin sensitivity, T-cell functions, and dyslipidemia (Garba et al., 2020).

Anti-obesity and antihypertensive effect

Cymbopogon leaves have been commonly consumed as tea to manage glucose, lipid, and fat levels in the blood serum, which may help to prevent obesity and hypertension (Shah et al., 2011). An experiment conducted with an aqueous extract of C. citratus showed a decrease in fasting plasma, glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoproteins, and very low-density lipoprotein while raising the plasma high-density lipoprotein level of rats with no effect on the plasma triglyceride levels (Adeneye and Agbaje 2007). Similarly, C. nardus could also console obesity by downregulating adipogenic and lipogenic genes (Ruangaram and Kato 2022). The evidence also suggested that Cymbopogon could reduce blood pressure and maintain blood glucose by secreting insulin (hyperinsulinemia) (Shimono et al., 2010).

Antinociceptive effect

Cymbopogon has long been used as a traditional medicine to relieve pain and anxiety in living beings (Ademuyiwa et al., 2015). Citronellal, a monoterpene observed in several Cymbopogon species, demonstrated the inhibition of descending pain pathways with anti-hyperalgesic actions that lasted longer when forming a β-cyclodextrin complex (Santos et al., 2016). While the essential leaf oil of C. winterianus exhibits antinociceptive effects through the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis (Leite et al., 2010).

Insecticidal activity

Pathogens and insects have been controlled using essential oils from different Cymbopogon species, for example, piperitone from C. schoenanthus is proven to be a strong repellant against Crematogaster spp (Bowers et al., 1993) and Callosobruchus maculatus (Ketoh et al., 2006). The essential oils of C. citratus, C. nardus, and C. martini are reported to be extremely efficient against anopheline mosquitos, Anopheles culicifacies, Anopheles quinquefasciatus (Ansari and Razdan 1995), and Aedes aegypt by the essential oil of C. flexuosus (Osmani and Sighamony 1980).

Anti-HIV effect

In HIV/AIDS patients, citronella oil extracted from C. citratus leaves was reported to heal oral thrush caused by Candida albicans in 1–5 days (Wright et al., 2009).

Perfumery

Most Cymbopogon species could produce a lot of essential oils that are aromatic, hence their extensive use in perfumery and the fragrance industry. Known as natural fragrance, Java citronella oil is used for the extraction of aromatic isolates, which has been added to several products due to their basic aromas. In East Indian perfumery, lemongrass oil from C. pendulus is the primary source. For C. winterianus oil, it provides scent and good odor to low-cost items such as sprays, disinfectants, and polishes. Palmarosa oil from C. martinii is extensively used in soaps more than any other oil due to its rose-like prominent and lasting odor, which can also be found in some mouth fresheners (Guenther and Althausen, 1948; Opdyke 1975). Other oils that can be used in perfuming soaps and scenting cosmetics include the essential oil of C. caesius, ginger grass oil, Palmarosa oil, C. winterianus oil, Java citronella oil, etc.

Toxicology

Generally, Cymbopogon is safe when consumed orally, topically, or used as aromatherapy. However, there are some factors, like heavy metal contamination from the soil, interaction of Cymbopogon with some drugs, and wrong consumption that can cause an undesirable effect (Ekpenyong et al., 2015a). According to some studies, citronella oil derived from the species C. afronardus, C. nardus, C. validus, and C. winterianus, is one of the ingredients in insect repellents and is applied topically to prevent mosquito bites. However, some adverse effects have aroused public concern. This includes skin reactions or irritation in some people, lung damage prior to its inhalation, and some reports of child poisoning after ingesting citronella oil-contained insect repellent (RxList 2021a, November 6). Other negative effects documented prior to the use of lemon grass include skin allergies when used directly on the skin, toxic alveolitis when inhaled, an elevation in amylase, and bilirubin (RxList 2021b, February 9). Relevant findings suggest that toxicological biomarkers and genotoxicity of C. citratus essential oil have a low toxicity level but are suitable and safe in long-term treatment at doses up to 100 mg/kg (Bidinotto et al., 2011). Although the United States has classified lemongrass as relatively safe., it is not recommended for use during pregnancy and breast-feeding, considering its stimulation to uterine and menstrual flow (Nimenibo-Uadia and Nwosu, 2020).

Quality control

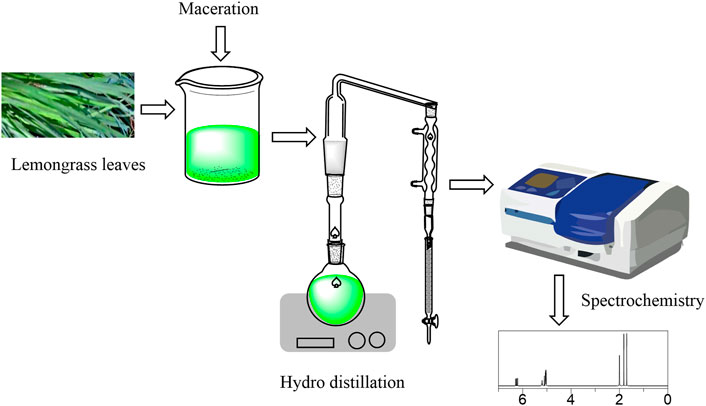

Quality control is important for medicinal herbs as it helps in identifying the herb, discovering the active and minimal components, and becoming acquainted with the extraction, separation, or isolation process of the herb (Wang et al., 2019). Figure 7 summarizes this process of Cymbopogon genus. This was conducive to assure the safety of the herb, its ethnopharmacology, and its pharmacological effects.

FIGURE 7. Plant collection, extraction, isolation, and analysis of constituents in Cymbopogon genus.

Plant collection

Fresh plant leaves are obtained and then washed rigorously with either distilled water or normal saline. The leaves are then ground into fine powder with the aid of an electric blender and then stored at room temperature.

Extraction process

Via the maceration technique, several grams of powdered plant leaves are extracted with a litre of methanol in a stopped bottle overnight while being stirred periodically. And the sample is sieved and then filtered using filter paper. After that, several grams of plant leaves are simmered in a conical flask with 500 ml of double-distilled water for 1 h. The decoction is cooled for 3 h and then filtered using a piece of clean, sterile, white cotton cloth. The extract/filtrate is then concentrated to interesting concentrations using a rotary evaporator at a specific temperature, and stored in an airtight container and kept in the freezer until further use. The concentrate can then be used to prepare different concentrations (mg/ml) of the extract using distilled water (Adeneye and Agbaje, 2007; Elekofehinti et al., 2020).

Isolation process

Isolation of essential oils is done via hydrodistillation, where several grams of plant leaves are steam distilled for 3 h in a modified Clevenger-type apparatus. The essential oils are stored in a sealed vial at a specific temperature and the yields are calculated referring to the following formula: Yield (%) = (Oil (ml))/(Plant (g)) × 100 (Kpoviessi et al., 2014; Tavares et al., 2015; Mendes Hacke et al., 2020). The yields are based on the volume of water, the size of the leaves, and the extraction time (Thakker et al., 2016).

Physicochemical and spectroscopic techniques

The basic physical and chemical properties of a substance are known as physicochemical properties. This includes color, boiling temperature, refraction index, density, volatility, water solubility, and flammability. According to the research done on Cymbopogon citratus, an Atago ND R5000 refractometer (Osaka, Japan) was used to measure the refractive index of oil, according to the 921.08 AOAC (2000) method. The density was evaluated according to the 985.19 AOAC (2000) method using a 2 ml pycnometer. The density and refractive index are in the range (ρ = 0.848–0.949 g/ml; IR = 1.332–1.482). A yellow hue was detected using a Color Guard 05 colorimeter in transmittance mode when measuring the color parameters (Paviani et al., 2006; Essien et al., 2008; Tovar et al., 2011; del Carmen Vázquez-Briones et al., 2015). Spectroscopic techniques are precise analytical methods used to discover the structures of atoms, molecules, and unknown chemical compositions in Cymbopogon genus. Some of the techniques used to discover Cymbopogon essential oils and constituents include gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, fourier transform infrared spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance, differential scanning calorimetry, and scanning electron microscopy (Fortuna et al., 2011; del Carmen Vázquez-Briones et al., 2015; da Silva Martins et al., 2021).

Discussion

The use of traditional medicines is widespread and dates back a long time before the increase in technology and knowledge that we have now (Wang et al., 2019 and, 2022). Cymbopogon species can also be termed as medicinal plants due to their many reported medical benefits, which mostly ascribe to their essential oils and the whole parts of the plant in general. Most Cymbopogon species are declared relatively safe to consume, except for some like C. winterianus, C. schoenanthus, C. pendulus, and obtectus, whose edible uses are unknown but are known to be used for medicinal purposes, perfumery products, cosmetics and household insecticides. Traditionally, the use of these species varies from simply being consumed as tea, drinks, or food flavoring. Medically, they have been argued to exhibit: a) anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, anti-dyspeptic, and anti-fever actions; b) antispasmodic, analgesic, antipyretic, tranquilizer, anti-hermetic, and diuretic anti-fever; c) ease dysmenorrhea; d) detoxication effects on the kidney and liver. The dosage used traditionally is not standard nor scientifically approved. However, it is believed in most countries that one tea cup of lemongrass daily can strengthen individual’s immunity. Clinically, citral, the main component in lemongrass, together with its other components, is thought to have anticancer ability and reduce the risk of various developing cancers by attacking the cancer cells or by boosting the immunity system. On the other hand, some cancer patients are given lemongrass tea after going through rounds of chemotherapy or radiation for relief. A study manifested that C. citratus tea can help get rid of gastric ulcers or even reduce the risk of gastric ulcers obtained from synthetic drugs like aspirin (Fernandes et al., 2012). Evidence also documented that drinking lemon grass tea every day for a month boosted the red blood cell count by increasing the amount of hemoglobin concentration, which was attributed to its superior antioxidant properties (Ekpenyong et al., 2015b).

Furthermore, many investigations have been dedicated to exploring the phytochemistry, phytotherapy and pharmacology of Cymbopogon species. In one of the studies, it has been reported that a dichloromethane extract of C. ambiguous was demonstrated to have antiplatelet activity, which is believed to be highly because of its eugenol content (Uddin et al., 2011). Another study substantiated that the methanolic extract of C. citratus can achieve a dose-dependent relaxant activity through endothelial vasoconstriction via the nitric oxide pathway (Pereira et al., 2013). As to adverse effects, it is generally safe to consume some of the Cymbopogon species, but several adverse effects have been reported by oral or topical administration. Adverse effects observed orally include fatigue, dry mouth, excessive urination, and vertigo. Noteworthily, lemongrass essential oil might harm the mucous membranes in the stomach and liver when excessive and unrestrained use. When applied topically, skin reactions or irritation can be observed. It is also advisable to avoid taking it with drugs that are glutathione-S-transferase substrates and cytochrome p450 substrates to prevent any risk of increased side effects of these drugs. Moreover, pregnant and breast-feeding mothers can also avoid consuming lemongrass tea, citronella oil and its related products, so as to prevent its effects on infant development (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center 2020, February 14).

Conclusion and future prospects

Cymbopogon species are very fascinating, diverse, and rich in every sense, from their simple traditional uses like culinary and tea. Of which some of the species like C. nardus are not edible due to their unpleasant nature, while some remain unknown as to whether they are edible or not. To their medicinal uses, the robust pharmacological activity is mainly attributed to their richness in essential oils, such as monoterpenes, monoterpenoids, sesquiterpenes, sesquiterpenoids, and certain fatty alcohols. This genus is widespread throughout the world, with species like C. giganteus and C. densiflorus found in tropical Africa, C. nardus in eastern Africa, C. caesius in southern and eastern Africa, C. martinii, C. flexuosus, C. distans, and C. coloratus in eastern Asia, among others, all of which have unique medicinal and commercial benefits. Lastly, more research is needed to improve the ones that are known and to reveal those with little knowledge. Researchers can come up with more essential products that can be made using natural ingredients to replace those manufactured with harsh chemicals, which cause a lot of side effects and negative health factors. In addition, the drug dosage and mode of drugs traditionally given to people should be effectively tested, and this will aid in the increase of certified medicinal drugs and enhanced pharmacological effects in the future. Meanwhile, the exact clinical efficacy and potential organ toxicity of some species or active ingredients also need to be further elucidated.

Author contributions

QZ and XW designed this review and revised the final manuscript. JT and QY collected the data, sorted out the figures and tables, and wrote the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82160816, 81660700 and 82104533), the Ningxia National Natural Science Foundation (2020AAC02017), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M683273) and the Science & Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2021YJ0175).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdel-Moneim, F. M., Ahmed, Z. F., Fayez, M. B., and Ghaleb, H. (1969). Constituents of local plants. XIV. The antispasmodic principle in Cymbopogon proximus. Planta Med. 17, 209–216. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1099848

Abe, S., Sato, Y., Inoue, S., Ishibashi, H., Maruyama, N., Takizawa, T., et al. (2003). Anti-Candida albicans activity of essential oils including Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) oil and its component, citral. Nippon. Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 44, 285–291. doi:10.3314/jjmm.44.285

Ademuyiwa, A. J., Elliot, S. O., Olamide, O. Y., Omoyemi, A. A., and Funmi, O. S. (2015). The effects of Cymbopogon citratus (lemon grass) on the blood sugar level, lipid profiles and hormonal profiles of Wistar albino rats. Am. J. Toxicol. 1, 8–18.

Adeneye, A. A., and Agbaje, E. O. (2007). Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of fresh leaf aqueous extract of Cymbopogon citratus Stapf. in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 112, 440–444. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.03.034

Ai-Ghamdi, S. S., Ai-Ghamdi, A. A., and Shammah, A. A. (2007). Inhibition of calcium oxalate nephrotoxicity with Cymbopogon schoenanthus (Al-Ethkher). Drug Metab. Lett. 1, 241–244. doi:10.2174/187231207783221420

Aibinu, I., Adenipekun, T., Adelowotan, T., Ogunsanya, T., and Odugbemi, T. (2007). Evaluation of the antimicrobial properties of different parts of Citrus aurantifolia (lime fruit) as used locally. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 4, 185–190.

Akono Ntonga, P., Baldovini, N., Mouray, E., Mambu, L., Belong, P., and Grellier, P. (2014). Activity of Ocimum basilicum, Ocimum canum, and Cymbopogon citratus essential oils against Plasmodium falciparum and mature-stage larvae of Anopheles funestus s. s. Parasite 21, 33. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014033

Alameen, S. M. A. (2020). “Chemical characterization of marhabaib (cymbopgon) leaves, spikes and their essential oil (doctoral dissertation, Sudan university of science and technology),” (Sudan: Sudan University of Science and Technology College of Graduate Studies). master’s thesis.

Alitonou, G. A., Avlessi, F., Sohounhloue, D. K., Agnaniet, H., Bessiere, J. M., and Menut, C. (2006). Investigations on the essential oil of Cymbopogon giganteus from Benin for its potential use as an anti-inflammatory agent. Int. J. Aromather. 16, 37–41. doi:10.1016/j.ijat.2006.01.001

Almeida, K. B., Araujo, J. L., Cavalcanti, J. F., Romanos, M. T. V., Mourão, S. C., Amaral, A. C. F., et al. (2018). In vitro release and anti-herpetic activity of Cymbopogon citratus volatile oil-loaded nanogel. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 28, 495–502. doi:10.1016/j.bjp.2018.05.007

Anal, J. M. (2014). Trace and essential elements analysis in Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) stapf samples by graphite furnace-atomic absorption spectroscopy and its health concern. J. Toxicol. 2014, 690758. doi:10.1155/2014/690758

Andila, P. S., Hendra, I. P. A., Wardani, P. K., Tirta, I. G., Sutomo, S., and Fardenan, D. (2018). The phytochemistry of Cymbopogon winterianus essential oil from Lombok Island, Indonesia and its antifungal activity against phytopathogenic fungi. Nusant. Biosci. 10, 232–239. doi:10.13057/NUSBIOSCI/N100406

Ansari, M. A., and Razdan, R. K. (1995). Relative efficacy of various oils in repelling mosquitoes. Indian J. Malariol. 32, 104–111.

Arrey Tarkang, P., Franzoi, K. D., Lee, S., Lee, E., Vivarelli, D., Freitas-Junior, L., et al. (2014). In vitro antiplasmodial activities and synergistic combinations of differential solvent extracts of the polyherbal product, Nefang. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 835013. doi:10.1155/2014/835013

Asif, A., and Khodadadi, E. (2013). Medicinal uses and chemistry of flavonoid contents of some common edible tropical plants. J. Paramedical Sci. 4, 119–138. doi:10.22037/JPS.V4I3.4648

Avoseh, O., Oyedeji, O., Rungqu, P., Nkeh-Chungag, B., and Oyedeji, A. (2015). Cymbopogon species; ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and the pharmacological importance. Molecules 20, 7438–7453. doi:10.3390/molecules20057438

Bagheri, R., Mohamadi, S., Abkar, A., and Fazlollahi, A. (2007). Essential oil compositions of Cymbopogon parkeri STAPF from Iran. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 10, 3485–3486. doi:10.3923/pjbs.2007.3485.3486

Bayala, B., Bassole, I. H. N., Maqdasy, S., Baron, S., Simpore, J., and Lobaccaro, J. A. (2018). Cymbopogon citratus and Cymbopogon giganteus essential oils have cytotoxic effects on tumor cell cultures. Identification of citral as a new putative anti-proliferative molecule. Biochimie 153, 162–170. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2018.02.013

Bharti, S., Kumar, A., Prakash, O., Krishnan, S., and Gupta, A. (2013). Essential oil of Cymbopogon Citratus against diabetes: Validation by in vivo experiments and computational studies. J. Bioanal. Biomed. 5, 194–203. doi:10.4172/1948-593X.1000098

Bhuyan, P. D., Tamuli, P., and Boruah, P. (2015). In-vitro efficacy of certain essential oils and plant extracts against three major pathogens of jatropha curcas L. Am. J. Plant Sci. 6, 362–365. doi:10.4236/ajps.2015.62041

Bidinotto, L. T., Costa, C. A., Salvadori, D. M., Costa, M., Rodrigues, M. A., and Barbisan, L. F. (2011). Protective effects of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus STAPF) essential oil on DNA damage and carcinogenesis in female Balb/C mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 31, 536–544. doi:10.1002/jat.1593

Boaduo, N. K., Katerere, D., Eloff, J. N., and Naidoo, V. (2014). Evaluation of six plant species used traditionally in the treatment and control of diabetes mellitus in South Africa using in vitro methods. Pharm. Biol. 52, 756–761. doi:10.3109/13880209.2013.869828

Boukhatem, M. N., Ferhat, M. A., Kameli, A., Saidi, F., and Kebir, H. T. (2014). Lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil as a potent anti-inflammatory and antifungal drugs. Libyan J. Med. 9, 25431. doi:10.3402/ljm.v9.25431

Bowers, W. S., Ortego, F., You, X., and Evans, P. H. (1993). Insect repellents from the Chinese prickly ash Zanthoxylum bungeanum. J. Nat. Prod. 56, 935–938. doi:10.1021/np50096a019

Cardoso, J., and Soares, M. J. (2010). In vitro effects of citral on Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclogenesis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 105, 1026–1032. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762010000800012

Chagonda, L. S., Makanda, C., and Jean〤laude, C. (2000). The essential oils of wild and cultivated cymbopogon validus (stapf) stapf ex burtt davy and elionurus muticus (spreng.) kunth from Zimbabwe. Flavour. Frag. J. 15, 100–104. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(200003/04)15:2<100::AID-FFJ874>3.0.CO;2-Y

Chisowa, E. H., Hall, D. R., and Farman, D. I. (1998). Volatile constituents of the essential oil of Cymbopogon citratus Stapf grown in Zambia. Flavour. Frag. J. 13, 29–30. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(199801/02)13:1<29::AID-FFJ682>3.0.CO;2-S

Choudhury, S. N., and Leclercq, P. (1995). Essential oil of Cymbopogon khasianus (Munro ex hack.) Bor from northeastern India. J. Essent. Oil Res. 7, 555–556. doi:10.1080/10412905.1995.9698585

Chouhan, S., Sharma, K., and Guleria, S. (2017). Antimicrobial activity of some essential oils-present status and future perspectives. Medicines 4, 58. doi:10.3390/medicines4030058

Chowdhury, S. R., Tandon, P., and Chowdhury, A. R. (2010). Chemical composition of the essential oil of cymbopogon flexuosus (Steud) wats. growing in kumaon region. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 13, 588–593. doi:10.1080/0972060X.2010.10643867

Colotta, F., Allavena, P., Sica, A., Garlanda, C., and Mantovani, A. (2009). Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis 30, 1073–1081. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgp127

Costa, A. V., Pinheiro, P. F., Rondelli, V. M., de Queiroz, V. T., Tuler, A. C., Brito, K. B., et al. (2013). Cymbopogon citratus (poaceae) essential oil on frankliniella schultzei (thysanoptera: Thripidae) and Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Biosci. J. 29, 1840–1847.

Costa, G., Ferreira, J. P., Vitorino, C., Pina, M. E., Sousa, J. J., Figueiredo, I. V., et al. (2016). Polyphenols from Cymbopogon citratus leaves as topical anti-inflammatory agents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 178, 222–228. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.016

Cunha, B. G., Duque, C., Caiaffa, K. S., Massunari, L., Catanoze, I. A., Dos Santos, D. M., et al. (2020). Cytotoxicity and antimicrobial effects of citronella oil (Cymbopogon nardus) and commercial mouthwashes on S. aureus and C. albicans biofilms in prosthetic materials. Arch. Oral Biol. 109, 104577. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2019.104577

de Cássia da Silveira e Sá, R., Andrade, L. N., and De Sousa, D. P. (2013). A review on anti-inflammatory activity of monoterpenes. Molecules 18, 1227–1254. doi:10.3390/molecules18011227

De Smet, P. A. (1996). Some ethnopharmacological notes on African hallucinogens. J. Ethnopharmacol. 50, 141–146. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(95)01337-7

Deletre, E., Chandre, F., Williams, L., Duménil, C., Menut, C., and Martin, T. (2015). Electrophysiological and behavioral characterization of bioactive compounds of the Thymus vulgaris, Cymbopogon winterianus, Cuminum cyminum and Cinnamomum zeylanicum essential oils against Anopheles gambiae and prospects for their use as bednet treatments. Parasit. Vectors 8, 316. doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0934-y

Desai, M. A., and Parikh, J. (2012). Microwave assisted extraction of essential oil from cymbopogon flexuosus (Steud.) wats.: a parametric and comparative study. Sep. Sci. Technol. 47, 1963–1970. doi:10.1080/01496395.2012.659785

Dikshit, A. (1984). Antifungal action of some essential oils against animal pathogens. Fitoterapia 55, 171–176.

Dutta, S., Munda, S., Lal, M., and Bhattacharyya, P. (2016). A short review on chemical composition, therapeutic use and enzyme inhibition activities of Cymbopogon species. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 9, 1–9. doi:10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i46/87046

Ekpenyong, C. E., Akpan, E., and Nyoh, A. (2015a). Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and biological activities of Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf extracts. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 13, 321–337. doi:10.1016/S1875-5364(15)30023-6

Ekpenyong, C. E., Daniel, N. E., and Antai, A. B. (2015b). Bioactive natural constituents from lemongrass tea and erythropoiesis boosting effects: potential use in prevention and treatment of anemia. J. Med. Food 18, 118–127. doi:10.1089/jmf.2013.0184

El Tahir, K., and Abdel-Kader, M. S. (2008). Chemical and pharmacological study of Cymbopogon proximus volatile oil. Res. J. Med. Plant 2, 53–60. doi:10.17311/rjmp.2008.53.60

El-Bakry, A. A., and Abdel-Salam, A. M. (2012). Regeneration from embryogenic callus and suspension cultures of the wild medicinal plant Cymbopogon schoenanthus. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 11, 10098–10107. doi:10.5897/AJB12.331

EL-Kamali, H. H., EL-Nour, R. O., and Khalid, S. A. (2010). Molluscicidal activity of the essential oils of Cymbopogon nervatus leaves and Boswellia papyrifera resins. Curr. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 2, 139–142.

Elekofehinti, O. O., Onunkun, A. T., and Olaleye, T. M. (2020). Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf mitigates ER-stress induced by streptozotocin in rats via down-regulation of GRP78 and up-regulation of Nrf2 signaling. J. Ethnopharmacol. 262, 113130. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.113130

Essien, E. P., Essien, J. P., Ita, B. N., and Ebong, G. A. (2008). Physicochemical properties and fungitoxicity of the essential oil of Citrus medica L. against groundnut storage fungi. Turk. J. Bot. 32, 161–164.

Fernandes, C., De Souza, H., De Oliveria, G., Costa, J., Kerntopf, M., and Campos, A. (2012). Investigation of the mechanisms underlying the gastroprotective effect of Cymbopogon citratus essential oil. J. Young Pharm. 4, 28–32. doi:10.4103/0975-1483.93578

Figueirinha, A., Paranhos, A., Pérez-Alonso, J. J., Santos-Buelga, C., and Batista, M. T. (2008). Cymbopogon citratus leaves: Characterization of flavonoids by HPLC–PDA–ESI/MS/MS and an approach to their potential as a source of bioactive polyphenols. Food Chem. x. 110 (3), 718–728. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.045

Fortuna, A. M., Juárez, Z. N., Bach, H., Nematallah, A., Av-Gay, Y., Sánchez-Arreola, E., et al. (2011). Antimicrobial activities of sesquiterpene lactones and inositol derivatives from Hymenoxys robusta. Phytochemistry 72, 2413–2418. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.09.001

Francisco, V., Figueirinha, A., Neves, B. M., García-Rodríguez, C., Lopes, M. C., Cruz, M. T., et al. (2011). Cymbopogon citratus as source of new and safe anti-inflammatory drugs: bio-guided assay using lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 133, 818–827. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.018

Ganjewala, D., Gupta, A. K., and Muhury, R. (2012). An update on bioactive potential of a monoterpene aldehyde citral. J. Biol. Act. Prod. Nat. 2, 186–199. doi:10.1080/22311866.2012.10719126

Ganjewala, D., and Luthra, R. (2010). Essential oil biosynthesis and regulation in the genus Cymbopogon. Nat. Prod. Commun. 5, 1934578X1000500–72. doi:10.1177/1934578X1000500137

Garba, H. A., Mohammed, A., Ibrahim, M. A., and Shuaibu, M. N. (2020). Effect of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus Stapf) tea in a type 2 diabetes rat model. Clin. Phytosci. 6, 19–10. doi:10.1186/s40816-020-00167-y

Gebashe, F., Aremu, A. O., Gruz, J., Finnie, J. F., and Van Staden, J. (2020). Phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activity of grasses used in South African traditional medicine. Plants (Basel) 9, 371. doi:10.3390/plants9030371

Govere, J., Durrheim, D. N., Baker, L., Hunt, R., and Coetzee, M. (2000). Efficacy of three insect repellents against the malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis. Med. Vet. Entomol. 14, 441–444. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00261.x

Han, X., and Parker, T. L. (2017). Lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus) essential oil demonstrated anti-inflammatory effect in pre-inflamed human dermal fibroblasts. Biochim. Open 4, 107–111. doi:10.1016/j.biopen.2017.03.004

Heiba, H. I., and Rizk, A. M. (1986). Constituents of cymbopogon species. Qatar. Univ. Sci. Bull. 6, 53–75.

Heinrich, M. (2003). Plants and people of Nepal-narayan P. Manandhar with the assistance of sanjay manandhar. Portland, OR, USA: Timber Press, 599. US $69.95 (hardcover), ISBN 0-88192-527-6.

Hilgert, N. I. (2001). Plants used in home medicine in the Zenta River basin, Northwest Argentina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 76, 11–34. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00190-8

Husain, A. (1994). Essential oil plants and their cultivation. Lucknow: Central institute of medicinal and aromatic plants.

Jeong, M. R., Park, P. B., Kim, D. H., Jang, Y. S., Jeong, H. S., and Choi, S. H. (2009). Essential oil prepared from Cymbopogon citrates exerted an antimicrobial activity against plant pathogenic and medical microorganisms. Mycobiology 37, 48–52. doi:10.4489/MYCO.2009.37.1.048

Jirovetz, L., Buchbauer, G., Eller, G., Ngassoum, M. B., and Maponmetsem, P. M. (2007). Composition and antimicrobial activity of Cymbopogon giganteus (Hochst.) chiov. essential flower, leaf and stem oils from Cameroon. J. Essent. Oil Res. 19, 485–489. doi:10.1080/10412905.2007.9699959

Jummes, B., Sganzerla, W. G., da Rosa, C. G., Noronha, C. M., Nunes, M. R., Barreto, P., et al. (2020). Antioxidant and antimicrobial poly-ε-caprolactone nanoparticles loaded with Cymbopogon martinii essential oil. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 23, 101499. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101499

Kadir, M. F., Bin Sayeed, M. S., Setu, N. I., Mostafa, A., and Mia, M. M. (2014). Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used by traditional health practitioners in Thanchi, Bandarban Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. J. Ethnopharmacol. 155, 495–508. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.05.043

Kalagatur, N. K., Gurunathan, S., Kamasani, J. R., Gunti, L., Kadirvelu, K., Mohan, C. D., et al. (2020). Inhibitory effect of C. zeylanicum, C. longa, O. basilicum, Z. officinale, and C. martini essential oils on growth and ochratoxin A content of A. ochraceous and P. verrucosum in maize grains. Biotechnol. Rep. (Amst). 27, e00490. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2020.e00490

Kanjilal, P. B., Pathak, M. G., Singh, R. S., and Ghosh, A. C. (1995). Volatile Constituents of the Essential Oil of Cymbopogon caesius (Nees ex Hook, et Arn.) Stapf. J. Essent. Oil Res. 7, 437–439. doi:10.1080/10412905.1995.9698557

Karami, S., Yargholi, A., Sadati Lamardi, S. N., Soleymani, S., Shirbeigi, L., and Rahimi, R. (2021). A review of ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Cymbopogon species. Res. J. Pharmacogn. 8, 83–112. doi:10.22127/RJP.2021.275223.1682

Kasali, A. A., Oyedeji, A. O., and Ashilokun, A. O. (2001). Volatile leaf oil constituents of Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf. Flavour Fragr. J. 16, 377–378. doi:10.1002/ffj.1019

Katiki, L. M., Chagas, A. C., Bizzo, H. R., Ferreira, J. F., and Amarante, A. F. (2011). Anthelmintic activity of Cymbopogon martinii, Cymbopogon schoenanthus and Mentha piperita essential oils evaluated in four different in vitro tests. Vet. Parasitol. 183, 103–108. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.001

Kaur, G., Arya, S. K., Singh, B., Singh, S., Dhar, Y. V., Verma, P. C., et al. (2019). Transcriptome analysis of the palmarosa Cymbopogon martinii inflorescence with emphasis on genes involved in essential oil biosynthesis. Ind. Crops Prod. 140, 111602. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111602

Kepe, T. (2004). Land restitution and biodiversity conservation in South Africa: the case of mkambati, eastern cape Province. Can. J. Afr. Stud./Revue Can. des Etudes Afr. 38, 688–704. doi:10.2307/4107262

Ketoh, G. K., Koumaglo, H. K., Glitho, I. A., and Huignard, J. (2006). Comparative effects of Cymbopogon schoenanthus essential oil and piperitone on Callosobruchus maculatus development. Fitoterapia 77, 506–510. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2006.05.031

Khadri, A., Serralheiro, M. L. M., Nogueira, J. M. F., Neffati, M., Smiti, S., and Araújo, M. E. M. (2008). Antioxidant and antiacetylcholinesterase activities of essential oils from Cymbopogon schoenanthus L. Spreng. Determination of chemical composition by GC–mass spectrometry and 13C NMR. Food Chem. x. 109, 630–637. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.12.070

Khanuja, S. P., Shasany, A. K., Pawar, A., Lal, R. K., Darokar, M. P., Naqvi, A. A., et al. (2005). Essential oil constituents and RAPD markers to establish species relationship in Cymbopogon Spreng. (Poaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 33, 171–186. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2004.06.011

Kpoviessi, S., Bero, J., Agbani, P., Gbaguidi, F., Kpadonou-Kpoviessi, B., Sinsin, B., et al. (2014). Chemical composition, cytotoxicity and in vitro antitrypanosomal and antiplasmodial activity of the essential oils of four Cymbopogon species from Benin. J. Ethnopharmacol. 151, 652–659. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.027

Leistner, O. A. (2000). Seed plants of southern Africa: families and genera. New York: Southern African Botanical Diversity Network.

Leite, B. L., Bonfim, R. R., Antoniolli, A. R., Thomazzi, S. M., Araújo, A. A., Blank, A. F., et al. (2010). Assessment of antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of Cymbopogon winterianus leaf essential oil. Pharm. Biol. 48, 1164–1169. doi:10.3109/13880200903280000

Leite, B. L., Souza, T. T., Antoniolli, A. R., Guimarãee, A. G., Siqueira, R. S., Quintans, J. S. S., et al. (2011). Volatile constituents and behavioral change induced by Cymbopogon winterianus leaf essential oil in rodents. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10, 8312–8319. doi:10.5897/AJB10.509

Locksley, H., Fayez, M., Radwan, A., Chari, V., Cordell, G., and Wagner, H. (1982). Constituents of local plants. Planta Med. 45, 20–22. doi:10.1055/s-2007-971233

Mahabir, D., and Gulliford, M. C. (1997). Use of medicinal plants for diabetes in Trinidad and Tobago. Rev. Panam. Salud. Publica. 1, 174–179. doi:10.1590/s1020-49891997000300002

Mahboubi, M., and Kazempour, N. (2012). Biochemical activities of Iranian Cymbopogon olivieri (Boiss) Bor. essential oil. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 74, 356–360. doi:10.4103/0250-474X.107071

Martins, W., de Araújo, J., Feitosa, B. F., Oliveira, J. R., Kotzebue, L., Agostini, D., et al. (2021). Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus DC. Stapf) essential oil microparticles: Development, characterization, and antioxidant potential. Food Chem. 355, 129644. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129644

Matasyoh, J. C., Wagara, I. N., Nakavuma, J. L., and Kiburai, A. M. (2011). Chemical composition of Cymbopogon citratus essential oil and its effect on mycotoxigenic Aspergillus species. Afr. J. Food Sci. 5, 138–142. doi:10.5897/AJFS.9000046

Melariri, P. E. (2010). The therapeutic effectiveness of some local Nigerian plants used in the treatment of malaria. Cape town: University of Cape Town. dissertation.

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. (2020). Lemongrass. Available at: https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/lemongrass [Accessed July 11, 2022].

Mendes Hacke, A. C., Miyoshi, E., Marques, J. A., and Pereira, R. P. (2020). Anxiolytic properties of Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) stapf extract, essential oil and its constituents in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Ethnopharmacol. 260, 113036. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.113036

Mishra, P. K., Prakash, B., Kedia, A., Dwivedy, A., Dubey, N. K., and Ahmad, S. (2015). Efficacy of Caesulia axillaris, Cymbopogon khasans and Cymbopogon martinii essential oils as plant based preservatives against degradation of raw materials of Andrographis paniculata by fungal spoilage. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr 104, 244–250. doi:10.1016/J.IBIOD.2015.06.015

Moreira, F. V., Bastos, J. F., Blank, A. F., Alves, P. B., and Santos, M. R. (2010). Chemical composition and cardiovascular effects induced by the essential oil of Cymbopogon citratus DC. Stapf, Poaceae, in rats. Rev. bras. Farmacogn. 20, 904–909. doi:10.1590/S0102-695X2010005000012

Morton, J. F. (1981). Atlas of medicinal plants of Middle America: Bahamas to yucatan. Springfield: Charles C Thomas.

Nguefack, J., Tamgue, O., Dongmo, J. L., Dakole, C., Leth, V., Vismer, H., et al. (2012). Synergistic action between fractions of essential oils from Cymbopogon citratus, Ocimum gratissimum and Thymus vulgaris against Penicillium expansum. Food control. 23, 377–383. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.08.002

Nimenibo-Uadia, R., and Nwosu, E. O. (2020). Phytochemical, proximate and mineral elements composition of lemongrass (cymbopogon citratus (DC) stapf) grown in ekosodin, Benin city, Nigeria. Niger. J. Pharm. Appl. Sci. Res. 9, 52–56.

Noor, S., Latip, H., Lakim, M. Z., Syahirah, A., and Bakar, A. (2012). “The potential of citronella grass, cymbopogon nardus as biopesticide against plutella xylostella faculty of plantation and agrotechnology, universiti teknologi MARA, 40450 shah alam,” in Proceedings of the UMT 11th International Annual Symposium on Sustainability Science and Management, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia, 9-11 July, 7438–7453.20

Ntulume, I., Victoria, N., Adam, A. S., and Aliero, A. A. (2019). Evaluation of antibacterial activity of cymbopogon citratus ethanolic leaf crude extract against Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from kampala international university teaching hospital western campus, Uganda. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol. 7, 31–38. doi:10.3126/ijasbt.v7i1.22326

Oladeji, O. S., Adelowo, F. E., Ayodele, D. T., and Odelade, K. A. (2019). Phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of cymbopogon citratus: A review. Sci. Afr. 6, e00137. doi:10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00137

Olivero-Verbel, J., Nerio, L. S., and Stashenko, E. E. (2010). Bioactivity against Tribolium castaneum Herbst (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) of Cymbopogon citratus and Eucalyptus citriodora essential oils grown in Colombia. Pest Manag. Sci. 66, 664–668. doi:10.1002/ps.1927

Opdyke, D. L. J. (1975). Monographs on fragrance raw materials. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 13, 449–457. doi:10.1016/s0015-6264(75)80165-9

Orafidiya, L. O. (1993). The effect of autoxidation of lemon-grass oil on its antibacterial activity. Phytother. Res. 7, 269–271. doi:10.1002/ptr.2650070315

Osmani, Z., and Sighamony, S. (1980). Effects of certain essential oils in mortality and metamorphosis of Aedes aegypti. Pesticides 14, 15–16.

Padalia, R. C., Verma, R. S., Chanotiya, C. S., and Yadav, A. (2011). Chemical fingerprinting of the fragrance volatiles of nineteen Indian cultivars of cymbopogon spreng. (Poaceae). Rec. Nat. Prod. 5, 290–299.

Pandey, M. C., Sharma, J. R., and Dikshit, A. (1996). Antifungal evaluation of the essential oil ofCymbopogon pendulus (nees ex Steud.) wats. cv. Praman. Flavour. Fragr. J. 11, 257–260. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-1026(199607)11:4<257::aid-ffj576>3.0.co;2-5(199607)11:43.0.CO

Paviani, L., Pergher, S., and Dariva, C. (2006). Application of molecular sieves in the fractionation of lemongrass oil from high-pressure carbon dioxide extraction. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 23, 219–225. doi:10.1590/S0104-66322006000200009

Pereira, G. L. D. C., Almeida, T. C., Seibert, J. B., Amparo, T. R., Soares, R. D. O. A., Rodrigues, I. V., et al. (2021). Antitumor effect of Cymbopogon densiflorus (Linneu) essential oil in bladder cancer cells. Nat. Prod. Res. 35, 5238–5242. doi:10.1080/14786419.2020.1747453

Pereira, S. L., Marques, A. M., Sudo, R. T., Kaplan, M. A., and Zapata-Sudo, G. (2013). Vasodilator activity of the essential oil from aerial parts of Pectis brevipedunculata and its main constituent citral in rat aorta. Molecules 18, 3072–3085. doi:10.3390/molecules18033072

Phillips, S, M., and Hua, P. (2005). Notes on grasses (Poaceae) for the flora of China, V. New species in Cymbopogon. Novon 15, 471–473. doi:10.2307/3393496

Piaru, S. P., Perumal, S., Cai, L. W., Mahmud, R., Majid, A. M. S. A., Ismail, S., et al. (2012). Chemical composition, anti-angiogenic and cytotoxicity activities of the essential oils of Cymbopogan citratus (lemon grass) against colorectal and breast carcinoma cell lines. J. Essent. Oil Res. 24, 453–459. doi:10.1080/10412905.2012.703496

Prasad, C., Singh, D., Shukla, O., and Singh, U. J. T. P. I. (2014). Cymbopogon jwarancusa-an important medicinal plant: A review. TPI 3, 13–19.

Prasad, C. S., Shukla, R., Kumar, A., and Dubey, N. K. (2010). In vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of essential oils of Cymbopogon martini and Chenopodium ambrosioides and their synergism against dermatophytes. Mycoses 53, 123–129. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01676.x

Quintans-Júnior, L. J., Souza, T. T., Leite, B. S., Lessa, N. M., Bonjardim, L. R., Santos, M. R., et al. (2008). Phythochemical screening and anticonvulsant activity of Cymbopogon winterianus Jowitt (Poaceae) leaf essential oil in rodents. Phytomedicine 15, 619–624. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2007.09.018

Rahim, S. M., Taha, E. M., Mubark, Z. M., Aziz, S. S., Simon, K. D., and Mazlan, A. G. (2013). Protective effect of Cymbopogon citratus on hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in the reproductive system of male rats. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 59, 329–336. doi:10.3109/19396368.2013.827268

Rizk, A. M., Hammouda, F. M., Ismail, S. I., Kamel, A. S., and Rimpler, H. (1995). Constituents of plants growing in Qatar part xxvii: Flavonoids of Cymbopogon parkeri. Qatar. Univ. Sci. J. 15, 33–35.

Rizk, A. M., Heiba, H. I., Sandra, P., Mashaly, M., and Bicchi, C. (1983). Constituents of plants growing in qatar: V. Constituents of the volatile oil of cymbopogon parkeri. J. Chromatogr. A 279, 145–150. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(01)93612-X

Rizk, A. M., Rimpler, H., Ghaleb, H., and Heiba, H. I. (1986). Constituents of plants growing in Qatar IX. The antispasmodic components ofCymbopogon parkeriStapf.ParkeriStapf. Park. Stapf. Int. J. Crud. Drug. Res. 24, 69–74. doi:10.3109/13880208609083309

Rizk, A. M. (1986). The phytochemistry of the flora of Qatar. Doha, State of Qatar: Scientific and Applied Research Centre, University of Qatar.

Roriz, C. L., Barros, L., Carvalho, A. M., Santos-Buelga, C., and Ferreira, I. (2014). Pterospartum tridentatum, Gomphrena globosa and cymbopogon citratus: A phytochemical study focused on antioxidant compounds. Food Res. Int. 62, 684–693. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2014.04.036

Ruangaram, W., and Kato, E. (2022). “The mechanistic study on the effect of Acacia concinna and cymbopogon nardus on lipid metabolism,” in Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of Food, Agriculture, and Natural Resource (IC-FANRES 2021), May 6, 22–26. doi:10.2991/absr.k.220101.004

Rungqu, P., Oyedeji, O., Nkeh-Chungag, B., Songca, S., Oluwafemi, O., and Oyedeji, A. (2016). Anti-inflammatory activity of the essential oils of cymbopogon validus (stapf) stapf ex burtt davy from eastern cape, South Africa. Asian pac. J. Trop. Med. 9, 426–431. doi:10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.03.031

Ruphin, F. P., Barthelemy, F., Guy, R., Oscar, R. A., Adolphe, R., Charles, A., et al. (2016). Vasodilator effects of cymbopogon pruinosus (poaceae) from madagascar on isolated rat thoracic aorta and structural elucidation of its two bioactive compounds. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 5, 46–55.

Russell, G. G., Watson, L., Koekemoer, M., Smook, L., Barker, N., Anderson, H., et al. (1991). Grasses of Southern Africa: An identification manual with keys, descriptions, distributions, classification, and automated identification and information retrieval from computerized data (Memoirs of the Botanical Survey of South Africa No. 58/Memoirs van die Botaniese Opname van Suid-Afrika No. 58). Lucknow: National Botanic Gardens, Botanical Research Institute.

RxList. Citronella oil (2021a). Available at: https://www.rxlist.com/citronella_oil/supplements.htm [Accessed July 15, 2022].

RxList. Lemongrass (2021b). Available at: https://www.rxlist.com/consumer_lemongrass/drugs-condition.htm [Accessed July 15, 2022].

Saeed, T., Sandra, P. J., and Verzele, M. (1978). Constituents of the essential oil of Cymbopogon jawarancusa. Phytochemistry 17, 1433–1434. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(00)94606-5

Santin, M. R., dos Santos, A. O., Nakamura, C. V., Dias Filho, B. P., Ferreira, I. C., and Ueda-Nakamura, T. (2009). In vitro activity of the essential oil of Cymbopogon citratus and its major component (citral) on Leishmania amazonensis. Parasitol. Res. 105, 1489–1496. doi:10.1007/s00436-009-1578-7

Santos, G., Brum, R., Castro, H., Gonçalves., C. G., and Fidelis, R. R. (2013). Effect of essential oils of medicinal plants on leaf blotch in Tanzania grass. Rev. Cienc. Agron. 44, 587–593. doi:10.1590/S1806-66902013000300022

Santos, P. L., Brito, R. G., Oliveira, M. A., Quintans, J. S. S., Guimaraes, A. G., Santos, M. R., et al. (2016). Docking, characterization and investigation of β-cyclodextrin complexed with citronellal, a monoterpene present in the essential oil of Cymbopogon species, as an anti-hyperalgesic agent in chronic muscle pain model. Phytomedicine 23, 948–957. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2016.06.007

Secoy, D. M., and Smith, A. E. (1983). Use of plants in control of agricultural and domestic pests. Econ. Bot. 37, 28–57. doi:10.1007/BF02859304

Seibert, J. B., Rodrigues, I. V., Carneiro, S. P., Amparo, T. R., Lanza, J. S., Frézard, F. J. G., et al. (2018). Seasonality study of essential oil from leaves of Cymbopogon densiflorus and nanoemulsion development with antioxidant activity. Flavour Fragr. J. 34, 5–14. doi:10.1002/ffj.3472

Shah, G., Shri, R., Panchal, V., Sharma, N., Singh, B., and Mann, A. S. (2011). Scientific basis for the therapeutic use of Cymbopogon citratus, stapf (Lemon grass). J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2, 3–8. doi:10.4103/2231-4040.79796

Sharma, P. R., Mondhe, D. M., Muthiah, S., Pal, H. C., Shahi, A. K., Saxena, A. K., et al. (2009). Anticancer activity of an essential oil from Cymbopogon flexuosus. Chem. Biol. Interact. 179, 160–168. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2008.12.004

Sharp, D., and Simon, B. K. (2002). AusGrass: grasses of Australia. Canberra: Australian Biological Resources Study.

Shimono, K., Oka, H., Suzuki, M., Senda, K., and Komai, S. (2010). Aromatic antihypertensive agent, and method for lowering blood pressure in mammals. U.S. Patent No 12/773 (Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office), 534.

Siew, Y. Y., Zareisedehizadeh, S., Seetoh, W. G., Neo, S. Y., Tan, C. H., and Koh, H. L. (2014). Ethnobotanical survey of usage of fresh medicinal plants in Singapore. J. Ethnopharmacol. 155, 1450–1466. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.07.024

Soares, M. O., Alves, R. C., Pires, P. C., Oliveira, M., and Vinha, A. F. (2013). Angolan Cymbopogon citratus used for therapeutic benefits: Nutritional composition and influence of solvents in phytochemicals content and antioxidant activity of leaf extracts. Food Chem. Toxicol. 60, 413–418. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.07.064

Solanki, K. P., Desai, M. A., and Parikh, J. K. (2019). Microwave intensified extraction: a holistic approach for extraction of citronella oil and phenolic compounds. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process Intensif. 146, 107694. doi:10.1016/j.cep.2019.107694

Sureshkumar, J., Silambarasan, R., and Ayyanar, M. (2017). An ethnopharmacological analysis of medicinal plants used by the Adiyan community in Wayanad district of Kerala, India. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 12, 60–73. doi:10.1016/j.eujim.2017.04.006

Takaisi-Kikuni, N. B., Tshilanda, D., and Babady, B. (2000). Antibacterial activity of the essential oil of Cymbopogon densiflorus. Fitoterapia 71, 69–71. doi:10.1016/s0367-326x(99)00097-0

Tavares, F., Costa, G., Francisco, V., Liberal, J., Figueirinha, A., Lopes, M. C., et al. (2015). Cymbopogon citratus industrial waste as a potential source of bioactive compounds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 95, 2652–2659. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6999

Tchoumbougnang, F., Zollo, P., Dagne, E., and Mekonnen, Y. (2005). In vivo antimalarial activity of essential oils from Cymbopogon citratus and Ocimum gratissimum on mice infected with Plasmodium berghei. Planta Med. 71, 20–23. doi:10.1055/s-2005-837745

Thakker, M. R., Parikh, J. K., and Desai, M. A. (2016). Isolation of essential oil from the leaves of cymbopogon martinii using hydrodistillation: Effect on yield of essential oil, yield of geraniol and antimicrobial activity. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 19, 1943–1956. doi:10.1080/0972060X.2016.1231087

Thompson, E. J., and Forster, P. I. (2021). Cymbopogon procerus (R. Br.) domin, the correct name for schizachyrium mitchelliana BK simon (poacaeae: Andropogoneae), and lectotypification of andropogon exaltatus R. Br. Austrobaileya 11, 41–44.

Toungos, M. D. (2019). Lemongrass (Cymbopogon, L. Spreng) valuable grass but underutilized in Northern Nigeria. Int. J. Innov. Food Nutr. Sustain. Agric. 7, 6–14.

Tovar, L. P., Pinto, G., Wolf-Maciel, M. R., Batistella, C. B., and Maciel-Filho, R. (2011). Short-Path-Distillation process of lemongrass essential oil: Physicochemical characterization and assessment quality of the distillate and the residue products. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 50, 8185–8194. doi:10.1021/ie101503n

Uddin, S. J., Grice, I. D., and Tiralongo, E. (2011). Cytotoxic effects of Bangladeshi medicinal plant extracts. Evid. Based. Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 578092–578097. doi:10.1093/ecam/nep111

Ullah, S., Rashid Khan, M., Ali Shah, N., Afzal Shah, S., Majid, M., and Asad Farooq, M. (2014). Ethnomedicinal plant use value in the lakki marwat district of Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 158, 412–422. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.048

Valdés, A. F., Martínez, J. M., Lizama, R. S., Gaitén, Y. G., Rodríguez, D. A., and Payrol, J. A. (2010). In vitro antimalarial activity and cytotoxicity of some selected Cuban medicinal plants. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 52, 197–201. doi:10.1590/s0036-46652010000400006

Vazquez-Briones, M., Hernandez, L. R., and Guerrero-Beltran, J. A. (2015). Physicochemical and antioxidant properties of Cymbopogon citratus essential oil. J. Food Res. 4, 36–45. doi:10.5539/jfr.v4n3p36

Wang, X. B., Hou, Y., Li, Q. Y., Li, X. H., Wang, W. X., Ai, X. P., et al. (2019). Rhodiola crenulata attenuates apoptosis and mitochondrial energy metabolism disorder in rats with hypobaric hypoxia-induced brain injury by regulating the HIF-1α/microRNA 210/ISCU1/2(COX10) signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 241, 111801. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.03.028

Wang, X. B., Tang, Y., Xie, N., Bai, J. R., Jiang, S. N., Zhang, Y., et al. (2022). Salidroside, a phenyl ethanol glycoside from Rhodiola crenulata, orchestrates hypoxic mitochondrial dynamics homeostasis by stimulating Sirt1/p53/Drp1 signaling. J. Ethnopharmacol. 293, 115278. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2022.115278

Wannissorn, B., Jarikasem, S., Siriwangchai, T., and Thubthimthed, S. (2005). Antibacterial properties of essential oils from Thai medicinal plants. Fitoterapia 76, 233–236. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2004.12.009

Wannissorn, B., and Soontorntanasart, T. (1996). Antifungal activity of lemon grass oil and lemon grass oil cream. Phytother. Res. 10, 551–554. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199611)10:7<551::AID-PTR1908>3.0.CO;2-Q

Wei, L. S., and Wee, W. (2013). Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Cymbopogon nardus citronella essential oil against systemic bacteria of aquatic animals. Iran. J. Microbiol. 5, 147–152. doi:10.1080/08856559.1928.10532132

Widiputri, D. I., Gunawan-Puteri, M. D., and Kartawiria, I. S. (2019). Benchmarking study of cymbopogon citratus and C. nardus for its development of functional food ingredient for anti-diabetic treatment. iconiet 2, 109–114. doi:10.33555/iconiet.v2i2.20

Wright, S. C., Maree, J. E., and Sibanyoni, M. (2009). Treatment of oral thrush in HIV/AIDS patients with lemon juice and lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratus) and gentian violet. Phytomedicine 16, 118–124. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2008.07.015

Zahra, A. A., Hartati, R., and Fidrianny, I. (2020). Review of the chemical properties, pharmacological properties, and development studies of cymbopogon sp. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 11, 10341–10350. doi:10.33263/BRIAC113.1034110350

Keywords: Cymbopogon, phytomedicine, phytochemistry, essential oils, pharmacological activity

Citation: Tibenda JJ, Yi Q, Wang X and Zhao Q (2022) Review of phytomedicine, phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacological activities of Cymbopogon genus. Front. Pharmacol. 13:997918. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.997918

Received: 19 July 2022; Accepted: 01 August 2022;

Published: 29 August 2022.

Edited by:

Alejandro Urzua, University of Santiago, ChileReviewed by:

Deming Liu, Chongqing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, ChinaZhang Guoxin, Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, China

Copyright © 2022 Tibenda, Yi, Wang and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaobo Wang, Vml0YURyd2FuZ0BjZHV0Y20uZWR1LmNu; Qipeng Zhao, emhxcDYyM0AxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jonnea Japhet Tibenda

Jonnea Japhet Tibenda Qiong Yi

Qiong Yi Xiaobo Wang

Xiaobo Wang Qipeng Zhao

Qipeng Zhao