- 1Department of Psychiatry, Tianjin Fourth Center Hospital, Tianjin, China

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Wenzhou Seventh Peoples Hospital, Wenzhou, China

- 3Department of Pharmacology, The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, China

- 4Peking University Clinical Research Institute, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China

- 5MECT Center, Sleep Disorder Center, Tianjin Anding Hospital, Tianjin, China

- 6Department of Psychiatry, First Hospital/First Clinical Medical College of Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, China

- 7Inpatient Department of Harbin First Psychiatry Hospital, Harbin, China

- 8Department of Psychiatry, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China

- 9Inpatient Department of Hebei Mental Health Center, Baoding, China

- 10Inpatient Department, Shandong Daizhuang Hospital, Jining, China

- 11Institute of Psychiatry, Jining Medical University, Jinning, China

- 12Department of Psychiatry, Henan Psychiatry Hospital, Xinxiang, China

- 13Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Ministry of Health (Peking University) and National Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders (Peking University Sixth Hospital), Beijing, China

- 14Department of Psychiatry, The First Hospital Affiliated to Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China

- 15Department of Psychiatry, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China

- 16Laboratory of Psychiatric-Neuroimaging-Genetic and Cor-morbidity, Tianjin Mental Health Center of Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin Anding Hospital, Tianjin, China

There has been limited studies examining treatment-induced heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) in women with severe mental illnesses. The aim of this study was to examine HMB prevalence and HMB-associated factors in young women (18–34 years old) diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BP), major depressive disorder (MDD), or schizophrenia (SCZ) who have full insight and normal intelligence. Eighteen-month menstruation histories were recorded with pictorial blood loss assessment chart assessments of HMB. Multivariate analyses were conducted to obtain odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Drug effects on cognition were assessed with the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB). HMB prevalence were: BP, 25.85%; MDD, 18.78%; and SCH, 13.7%. High glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was a strong risk factor for HMB [BP OR, 19.39 (16.60–23.01); MDD OR, 2.69 (4.59–13.78); and SCZ OR, 9.59 (6.14–12.43)]. Additional risk factors included fasting blood sugar, 2-h postprandial blood glucose, and use of the medication valproate [BP: OR, 16.00 (95%CI 12.74–20.22); MDD: OR, 13.88 (95%CI 11.24–17.03); and SCZ OR, 11.35 (95%CI 8.84–19.20)]. Antipsychotic, antidepressant, and electroconvulsive therapy use were minor risk factors. Pharmacotherapy-induced visual learning impairment was associated with HMB [BP: OR, 9.01 (95%CI 3.15–13.44); MDD: OR, 5.99 (95%CI 3.11–9.00); and SCZ: OR, 7.09 (95%CI 2.99–9.20)]. Lithium emerged as a protective factor against HMB [BP: OR, 0.22 (95%CI 0.14–0.40); MDD: OR, 0.30 (95%CI 0.20–0.62); and SCZ: OR, 0.65 (95%CI 0.33–0.90)]. In SCZ patients, hyperlipidemia and high total cholesterol were HMB-associated factors (ORs, 1.87–2.22). Psychiatrist awareness of HMB risk is concerningly low (12/257, 2.28%). In conclusion, prescription of VPA should be cautioned for women with mental illness, especially BP, and lithium may be protective against HMB.

Introduction

There is a relatively high prevalence of serious mental disorders, namely bipolar disorder (BP; lifetime prevalence, 2.4%), major depressive disorder (MDD; lifetime prevalence, 9.9%), and schizophrenia (SCZ, lifetime prevalence, 1%) in young women 18–34 years old (Kennedy et al., 2014; Tondo et al., 2014; Hui Poon et al., 2015; APA, 2016; Barnett, 2018; McIntyre et al., 2020; Howes et al., 2021; Papp et al., 2021; Rybak et al., 2021). Currently, they are treated primarily with antipsychotic agents, mood stabilizers (not a true pharmacological category; Stahl, 2021), antidepressants (Sienaert et al., 2013; Sinclair et al., 2019; Baandrup, 2020; Elias et al., 2021; Seppälä et al., 2021; Borbély et al., 2022), and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (Sinclair et al., 2019; Elias et al., 2021; Trifu et al., 2021).

Most antipsychotics inhibit serotonin reuptake, which can alter functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and thus may alter prolactin secretion and thereby cause menstrual disturbances (Huhn et al., 2019; Solmi et al., 2020), including heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), hypomenorrhea, or amenorrhea (Haddad and Wieck, 2004; Kumar et al., 2013; Besag et al., 2021). Furthermore, HPG axis dysfunction can also cause glucose and lipid metabolism disorders that can lead to excessive weight gain and obesity (An et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2021; Piatoikina et al., 2022). Obesity is associated with dysregulation of adipose tissue functions and aberrations in adipokine secretion that can alter inflammatory responses, endothelial cell functions, and coagulation pathways.

Antipsychotic agents, antidepressant agents, and mood stabilizers have been reported to increase risk of hemorrhage and bleeding (Aranth and Lindberg, 1992; Joffe et al., 2006a; Paavola et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2020). In women with severe mental illness, hemorrhage/bleeding presents mainly as HMB (El-Nashar et al., 2010; Stahl, 2021). HMB, which is defined as excessive regular or irregular menstrual bleeding (>80 ml per cycle) (Reavey et al., 2021b), affects 4% of women without organic pathology (Lethaby et al., 2009; Davies and Kadir, 2017). In mentally ill women, HMB has been reported to be associated with further psychiatric deterioration (Iles and Gath, 1989; Shannon, 1993; Pramodh, 2020; Arias-de la Torre et al., 2021; Padda et al., 2021). HMB in overweight women specifically has been related to metabolic disorders of blood glucose, lipids, and reproductive hormones (Iles and Gath, 1989; Shannon, 1993; Noerpramana, 1997; Pottegård et al., 2018; Pramodh, 2020; Schlaff et al., 2020; Arias-de la Torre et al., 2021; Padda et al., 2021; Pavlidi et al., 2021), all of which can be induced or exacerbated by psychiatric drugs (Iles and Gath, 1989; APA, 1994; Noerpramana, 1997; Meyer, 2002; Reynolds et al., 2007; Muir et al., 2008; Bradley and Gueye, 2016; Bora et al., 2017; Culpepper et al., 2017; Solé et al., 2017; Bekhbat et al., 2018; Pottegård et al., 2018; Calaf et al., 2020; Pramodh, 2020; Schlaff et al., 2020; Jang et al., 2021; Padda et al., 2021; Pavlidi et al., 2021).

Moreover, HMB can impair cognitive ability (Iles and Gath, 1989; Shannon, 1993; APA, 1994; Noerpramana, 1997; Meyer, 2002; Reynolds et al., 2007; Muir et al., 2008; El-Nashar et al., 2010; Bradley and Gueye, 2016; Bora et al., 2017; Culpepper et al., 2017; Solé et al., 2017; Bekhbat et al., 2018; Pottegård et al., 2018; Calaf et al., 2020; Pramodh, 2020; Schlaff et al., 2020; Arias-de la Torre et al., 2021; Jang et al., 2021; Padda et al., 2021; Pavlidi et al., 2021; Stahl, 2021), which may also be directly affected by mental illness and mental illness treatments (Iles and Gath, 1989; Shannon, 1993; APA, 1994; First et al., 1996; Noerpramana, 1997; Meyer, 2002; Reynolds et al., 2007; Muir et al., 2008; El-Nashar et al., 2010; Bradley and Gueye, 2016; Bora et al., 2017; Culpepper et al., 2017; Solé et al., 2017; Bekhbat et al., 2018; Pottegård et al., 2018; Calaf et al., 2020; Pramodh, 2020; Schlaff et al., 2020; Arias-de la Torre et al., 2021; Jang et al., 2021; Padda et al., 2021; Pavlidi et al., 2021; Stahl, 2021). Additionally, HMB may compromise patients’ reproductive potential (Iles and Gath, 1989; Shannon, 1993; APA, 1994; First et al., 1996; Noerpramana, 1997; Meyer, 2002; Reynolds et al., 2007; Muir et al., 2008; Bradley and Gueye, 2016; Bora et al., 2017; Culpepper et al., 2017; Solé et al., 2017; Bekhbat et al., 2018; Pottegård et al., 2018; Calaf et al., 2020; Pramodh, 2020; Schlaff et al., 2020; Arias-de la Torre et al., 2021; Jang et al., 2021; Padda et al., 2021; Pavlidi et al., 2021; Stahl, 2021). Hence, there is a multitude of negatively interacting factors related to HMB that can worsen the prognosis of young women suffering from serious mental disorders.

In the present study, we examined HMB occurrence and HMB-associated factors in young women diagnosed with BP, MDD, or SCZ who were being treated with antipsychotic medications. We conducted a retrospective multi-hospital study across 10 provinces in China. Data acquired for an 18-months target period were subjected to multiple regression analysis to investigate HMB-associated risk and protective factors in patients using therapeutic agents. The main aims of this work were to determine HMB prevalence, to identify HMB-associated associated factors in young women with severe mental illness, and to assess how aware psychiatrists are of HMB risk in this patient population.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

In this retrospective cohort study, we used convenience sampling to recruit participants being treated by 514 psychiatrists (257 senior psychiatrists, i.e., >10 years’ experience with annual research methods training) in outpatient departments at 10 hospitals located in the north, south, east, and west regions of China (across 10 provinces). A group of 10 gynecologists was invited to help assess HMB. The physician recruitment period lasted 2 months (July 1st to 31 August 2021). Recruited doctors furnished detailed information of the samples, including sociodemographic characteristics, diagnosis, menstrual cycle timing history from 1 January 2020 through 31 August 2021, HMB incidence, and cumulative therapeutic agent dosages. Informed consent forms were signed by patients and their guardians prior to data collection. Ethics approval was granted from the ethic committee of Tianjin Fourth Center Hospital of Tianjin Medical University (No. ZC-R-0001).

The patient inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) 18–34-year-old female patient with treatment-resistant BP, treatment-resistant MDD, or treatment-resistant SCZ; 2) first episode; 3) full insight about one’s own mental illness and treatment methods; 4) normal memory ability (to ensure recall of periods in the past 18 months); 5) medical record available to assure the absence of neurological or physical disease comorbidity, any history of menstrual dysfunction, and pharmacotherapies administrated in the prior 18 months; 6) willingness to volunteer participation in this study and provide detailed personal sociodemographic information. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) did not volunteer to participate; 2) cannot recall menstrual history of the past 18 months; 3) history of pregnancy and/or abortion in the past 18 months; 4) neurological illness, physical disease, or substance abuse history in the past 18 months; 5) diagnosis with any other mental disorder (including comorbid anxiety, depression, or personality disorder); 6) no majorly stressful life events in the past 18 months; and 7) no female family member/guardian available to assist with collecting information about the patient’s illness, menstrual status, HMB status, and other needed information. Typically, in Chinese culture, even if a woman has a close relationship with her husband, her mother will continue to manage her care from childhood into adulthood, which worked well for information acquisition in this study.

Procedures

Data Collection

We collected clinical information from one insurance settlement period in China (3 months). Each participating physician collated the following patient information: category of mental illness; total menstrual cycles in the past 18 months; HMB incidence in the past 18 months; total cumulative medication dosage in the past 18 months; glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level; steroid hormone levels; blood sugar levels; blood total cholesterol (TC) levels; blood lipid levels; and body mass index (BMI). BP, MDD, and SCZ definitions were adopted from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Edition IV (First et al., 1996) and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (Birchwood et al., 1994). Mental illness etiology was described based on core symptoms. Blood constituent level data determined closest to the start of the study were used. Each patient’s medical record was consulted for confirming medication dosage accuracy and an absence of neurological and physical disease history in the past 18 months.

Instruments

Patient insight was confirmed with the Birchwood Insight Scale (Beck et al., 2004) and Beck Cognitive Insight Scale (Wang et al., 2015). Normal memory function was confirmed with the Chinese version of the Wechsler memory scale-Fourth edition (Ko et al., 2021).

Total numbers of menstrual times in the past 18 months were recorded and the Pictorial Blood-loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) (Leucht et al., 2003) was used to assess HMB (although PBAC is used extensively to assess HMB at the moment, its validity regarding previous HMB status remains to be verified). Because this study was conducted retrospectively, we brought in gynecologists to show patients and their female guardians HMB on PBAC and guide information collection, including the presence of blood clots on sanitary napkins, how many sanitary napkins were used in one menstrual period, and how to calculate menstrual bleeding. Although previous studies have used more accurate HMB diagnostic criteria, the large sample included in this study precluded the use of such a highly complex procedure. Although our retrospective use of the PBAC represents a limitation, it provided useful information for this study. Eighteen-month cumulative antipsychotic, antidepressant, mood stabilizer, and anxiolytic/sleep aide use were converted to chlorpromazine equivalent (Hayasaka et al., 2015), fluoxetine equivalent (Rossetti and Alvarez, 2021), sodium valproate equivalent (García-Carmona et al., 2021), and diazepam equivalent (Paulzen et al., 2016), respectively.

Obesity was determined based on BMI (Mizuno et al., 2014). Prolactin, estradiol, progesterone, testosterone levels were determined with double-antibody radio-immunoassays. The cut-offs for hyperprolactinemia, high progesterone, and high testosterone were ≥40.0 μg/L (Nikolac Gabaj et al., 2018), ≥97.6 nmol/L, and ≥3.1 nmol/L (Lee et al., 2013), respectively. Fasting and 2-h postprandial blood glucose analyses (Gu et al., 2016) were conducted by a Cobas 6,000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), TC, and blood lipid levels (Nick and Campbell, 2007) were determined with an H-7600 automated biochemical analyzer (Hitachi High-Technologies, Tokyo, Japan).

Pregnancy tests were conducted to exclude pregnant patients from the study (Wang et al., 2015). An HMB self-report scale was used to assess patients’ views of the influence of HMB on their mental illness status. It included the following items and answer point values: 1) did you feel your mental illness symptoms deteriorated from HMB? (yes, 1; no, 0); 2) did the total deteriorated time exceed a month? (yes, 1; no, 0 AND if severe, +3, if moderate +2, if mild +1); 3) did you feel that you were suffering when experiencing HMB? (yes, 1; no, 0); 4) did you feel the total time of your suffering from HMB exceeded a month? (yes, 1; no, 0; severe suffering, +3; moderate suffering, +2; mild suffering, +1); 5) did you feel your life quality in the past 18 months was influenced by your HMB? (severe influence, four; moderate influence, three; mild influence, two; no influence, 0).

Cognition was assessed with the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB), which has a three-domain structure (McCleery et al., 2015; Lo et al., 2016). Specifically, MCCB assessments of processing speed (Trail Making Test, Part A; Symbol Coding; and Category Fluency: Animal Naming), working memory (Letter-Number Span); and verbal learning (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised; HVLT-R) were conducted. Verbal learning was assessed with the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (Schmidt, 1996; Bowie et al., 2018) instead of the HVLT-R in one participant.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were completed in SAS statistical software (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous-variable data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (normally distributed data). Data are compared across groups and within groups over time with analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and repeated measures ANOVAs, respectively. Categorical-variable data are expressed as numbers and percentages. Associations of clinical-demographic characteristics with HMB incidence were evaluated with univariate and multivariate logistic regression models and expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in the overall sample and by diagnosis group. Multivariate logistic models were first developed by adjusting for factors found to be significant in univariate analyses (p < 0.02); final multivariate models were limited to risk factors or confounders that were statistically significant (Nikoloulopoulos, 2012; Hidalgo and Goodman, 2013; Vuong et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2020).

Results

Sample

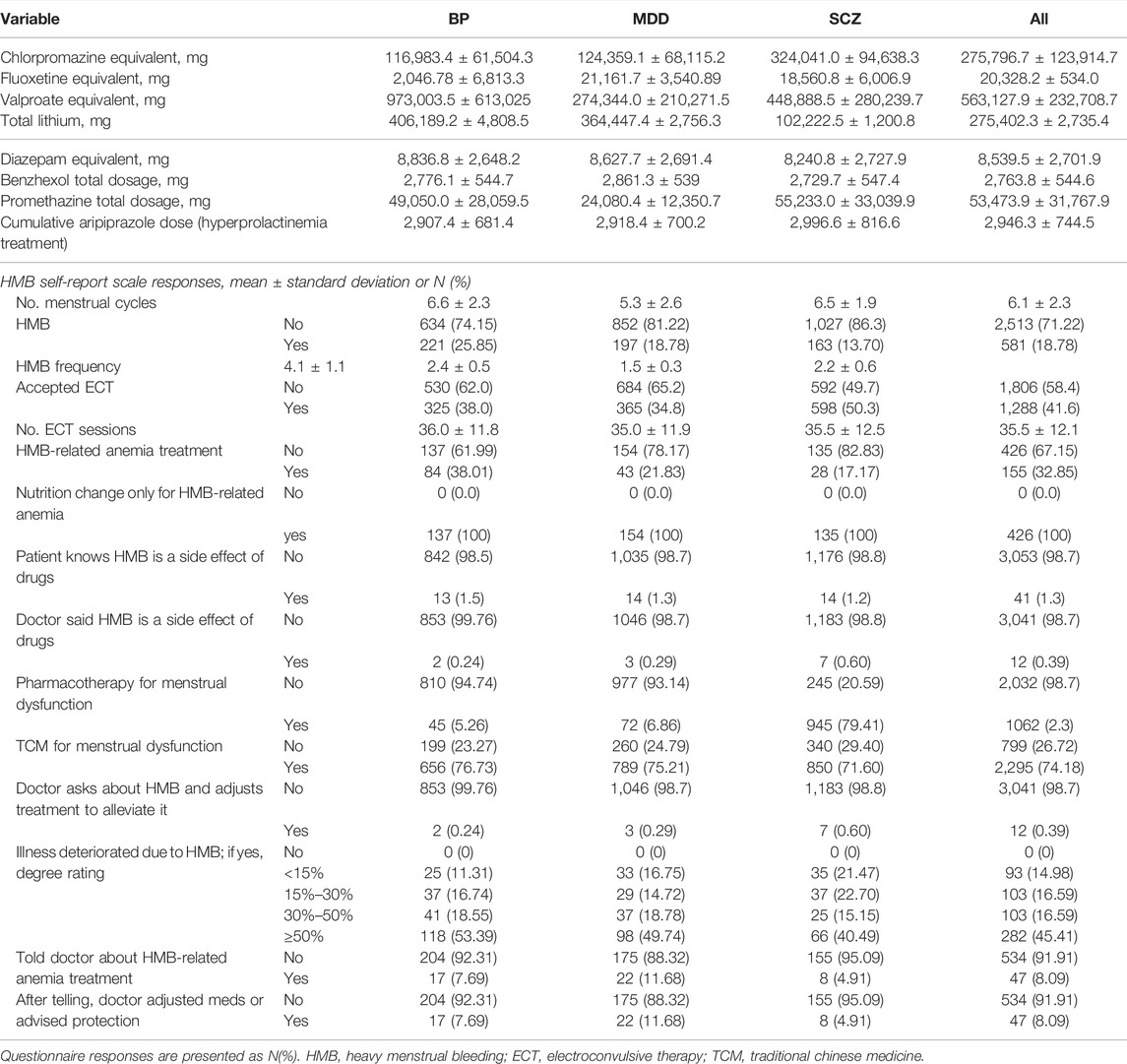

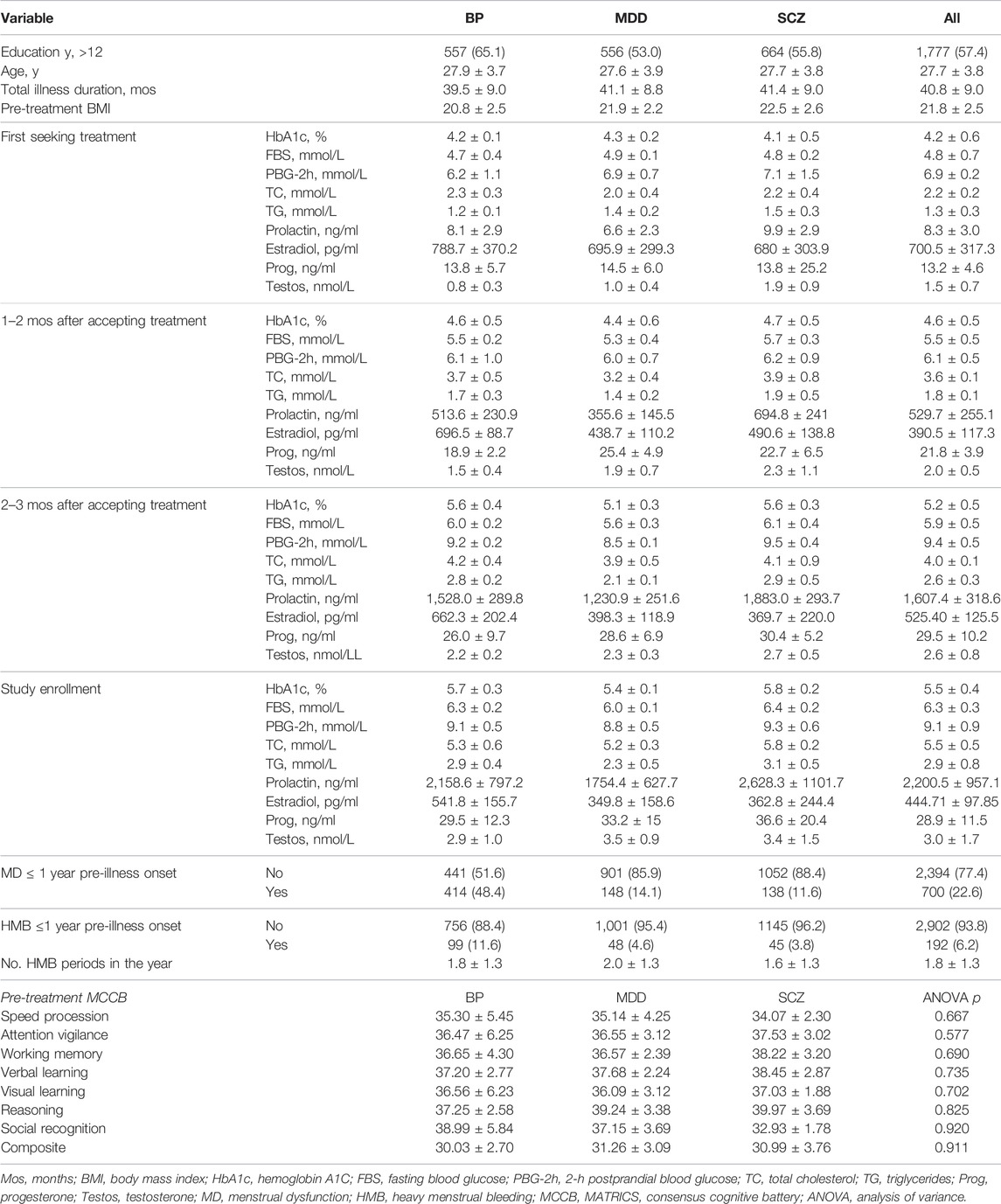

Complete information was obtained 3,094 of 3,500 participants (88.4%) who were recruited to enroll in this study. The final study sample of 3,094 participants, included 855 patients with BP, 1,049 patients with MDD, and 1,190 patients with SCZ. The BP, MDD, and SCZ groups were similar with respect to age, education level, and illness duration. The sample characteristics (as a whole and of each diagnosis group) are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of the total sample (N = 3,094) and the bipolar disorder (BP; N = 855), major depressive disorder (MDD; N = 2,049), and schizophrenia (SCZ; N = 1, 190) groups.

The patients’ treatment histories, including their interactions with their physicians in relation to HMB awareness as indicated on the HMB self-report scale, are summarized in Table 2, respectively. Although the patients indicated that HMB had negative effects on their illness progression and quality of life, few patients had been informed that HMB was a potential secondary adverse reaction to psychiatric medications. Furthermore, when queried, only 12 of the 257 psychiatrists servicing these patients (awareness rate, 2.28%) were aware of the risk.

HMB Prevalence

It was determined that 581/3,094 participants (18.78%) had HMB. Their average frequency of HMB in the past 18 months was 2.2 ± 0.6 menstrual cycles. The HMB prevalence rates by diagnosis group were: BP, 28.85% (221/855); MDD, 18.78% (197/1.49); and SCZ, 13.70% (163/1190). The prevalence rates of HMB in patients with BP and patients with MDD were 2.52-fold and 1.21-fold that in patients with SCZ.

Evolution of Cognitive Functioning

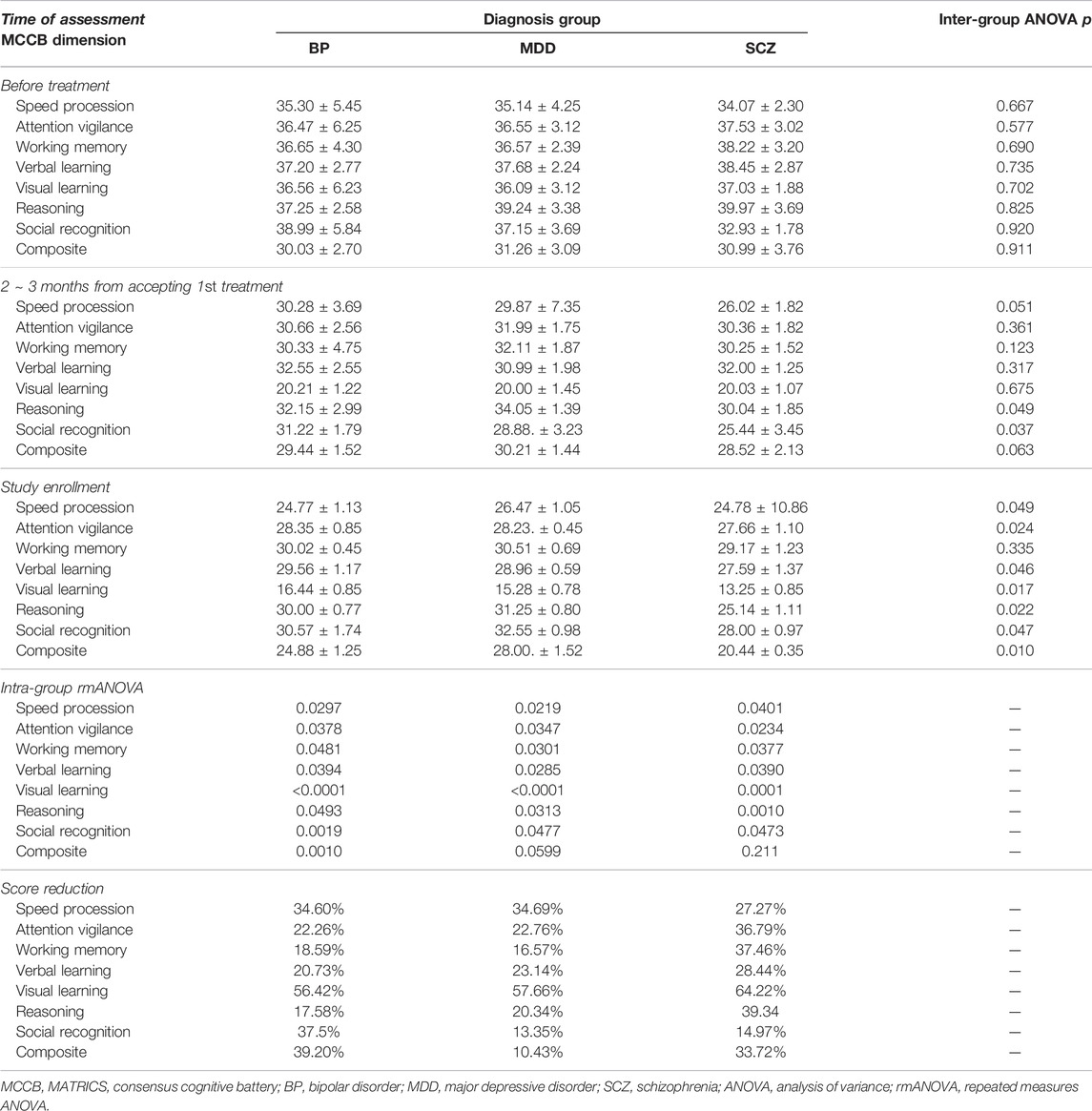

Mean (±standard deviations) of MCCB scores over time are reported in Table 3. Note that no MCCB domain scores differed between the diagnosis groups prior to the patients starting pharmacological treatment, though differences emerged over time, with diagnosis group having a main effect on all MCCB domain scores, except working memory, by the time of the study enrollment assessment. Visual learning was the most heavily impacted domain (see Table 3). Repeated measures ANOVAs showed that all MCCB domain scores changes over time for all groups, though the composite scores changed significantly over time for only the BP group.

TABLE 3. Comparison of MCCB scores before treatment, after 3 months treatment, and at study enrollment.

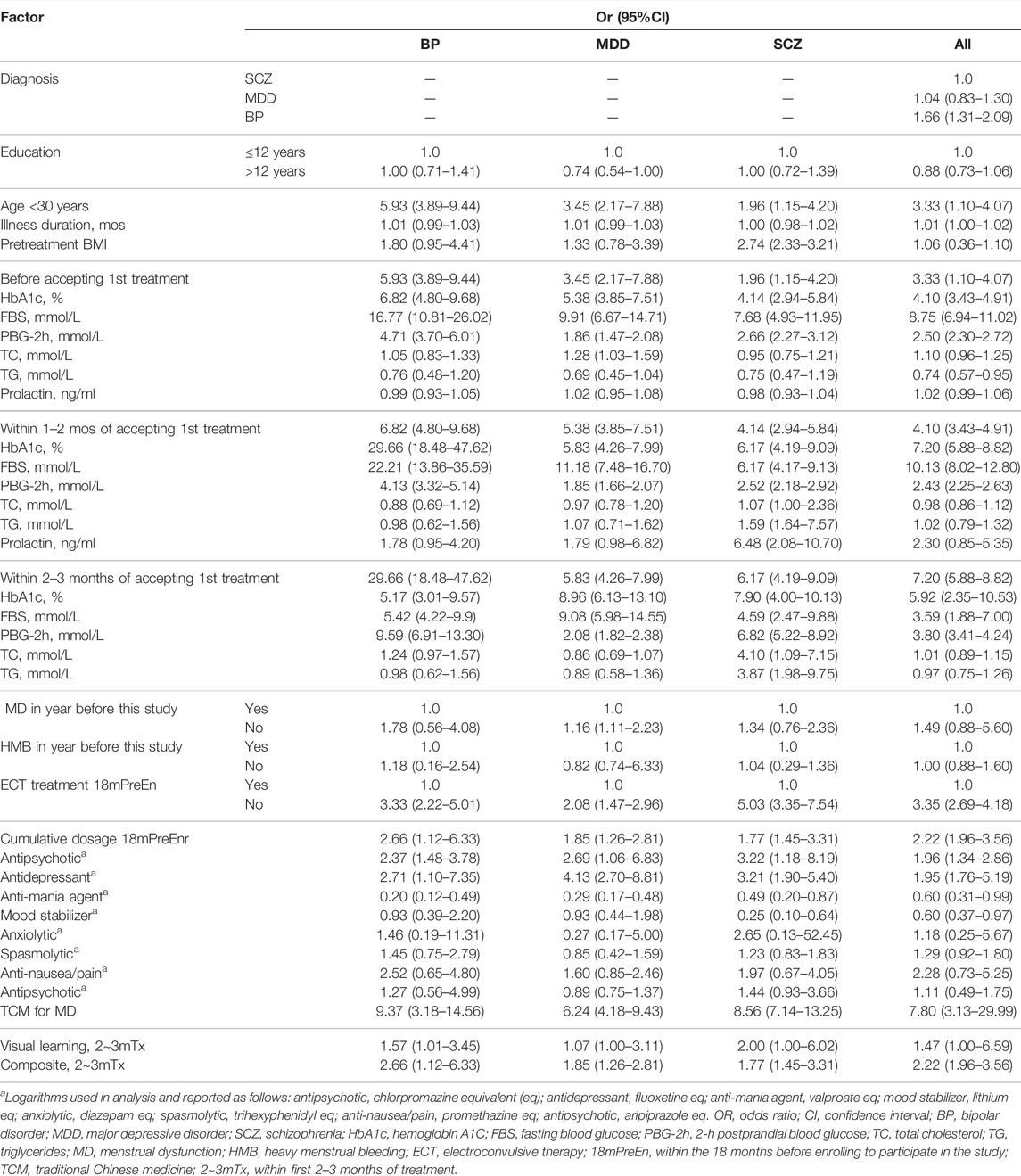

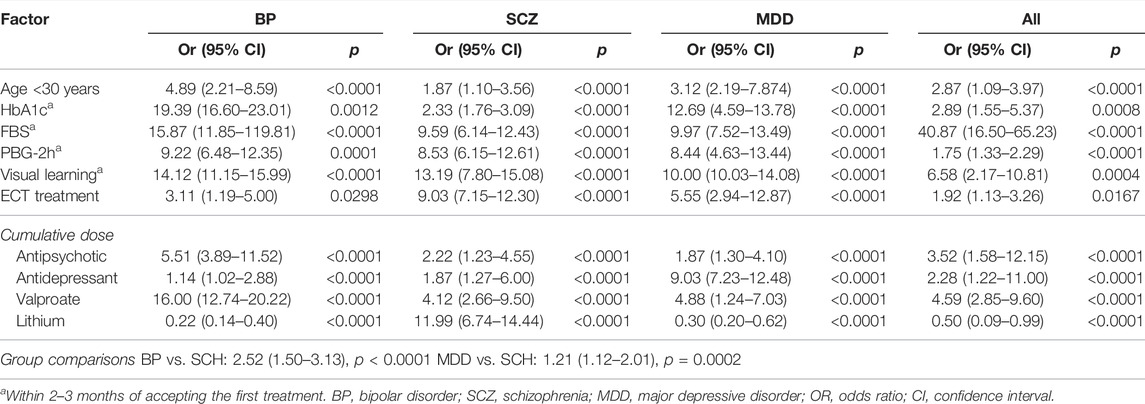

HMB-Associated Factors

As reported in detail in Table 4, univariate analyses indicated that the following variables were associated with HMB (ORs, 1.86–16.77): <30 years old; HbA1c; fasting blood sugar (FBS); and 2-h postprandial blood glucose (PBG-2h). As reported in detail in Table 5, multivariate analysis demonstrated that HMB in BP patients was associated with being younger than 30 years old as well as with visual learning scores, HbA1c levels, FBS, and PBG-2h within 2–3 months after commencing pharmacological treatment. In patients with SCZ, hyperlipidemia and high TC were associated with HMB. Reproductive hormone concentrations did not fluctuate in association with HMB. Notably, HMB was found to be strongly significantly associated with cumulative antidepressant, valproate, and lithium use in the patient sample as a whole and in each diagnosis group (Table 5), with the former two being a risk association (use predicts higher HMB risk) and the latter one being a protective association (use predicts lower HMB risk).

Discussion

This study was the first to our knowledge to examine HMB risk factors in patients with severe mental illness. We found that nearly one in five of the women in our study experienced HMB. Treatment-related HMB was associated with mental illness symptom deterioration in a majority of those patients, with the symptom deterioration being severe for more than half of those affected and 17.17%–38.01% of patients with HMB needing a professional gynecological medical intervention. The destructive influence of HMB in these patients was most prevalent in women diagnosed with BP. Our analyses revealed additional valuable information in multiple areas important for quality of care as elaborated below.

In the present study sample, HMB was more prevalent in patients with BP than in patients with MDD or SCZ. The reasons for this differentiation are not known and worthy of exploring in future studies. We found that high blood sugar levels were associated with HMB risk in patients with BP. Patients with BP had higher rates of menstrual dysfunction in our sample than in several previous studies (Rasgon et al., 2005a; Rasgon et al., 2005b; Konicki et al., 2021). Half of the BP patients with HMB in our sample were diagnosed with menstrual dysfunction before being diagnosed with BP. Meanwhile 38% developed menstrual dysfunction only after starting psychiatric pharmacotherapy, ∼80% of whom experienced menstrual flow increases, including HMB or prolonged bleeding. HMB was particularly prevalent among patients with BP who were taking valproate (Vuong et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2020; Konicki et al., 2021). Serum testosterone increases induced by valproate may contribute to the development of HMB (Bilo and Meo, 2008; Flores-Ramos et al., 2020; Kenna et al., 2009; McAllister-Williams, 2006; O'Donovan et al., 2002; Rasgon et al., 2005b; Zhang et al., 2016). Notably, in 2018, Elboga et al. reported the case of a boy who had manic episode after being given testosterone replacement therapy for hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (Elboga and Sayiner, 2018).

The frequency of HMB periods experienced was found to be influenced by blood sugar levels, cumulative medication dosages, and HbA1c changes emerging within 2–3 months after accepting treatment. Indeed, HbA1c and age (<30 years) were found to be persistent risk factors for treatment-associated HMB across the diagnostic groups. Among patients with SCZ, hyper-prolactin, high TC, high triglyceride levels, and an overweight BMI before treatment were all found to be risk factors for subsequent HMB. It remains to be determined in prospective cohort studies whether blood sugar disturbances are causative of or consequential to HMB. Notwithstanding, these findings indicate that physicians managing the cases of young women with mental illnesses should be attentive to changes in HbA1c and blood sugar, particularly in relation to monitoring cumulative medication dosage and medication phases.

Although patients with menstrual dysfunction of any kind in our study were found to have elevated levels of prolactin, estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, those with HMB per se did not have significantly elevated levels, and the frequency of HMB periods did not correlate with prolactin levels, consistent with previous studies (Lethaby et al., 2015). The need for a gynecological intervention was also not found to be related to prolactin level, neither was it related to estrogen, progesterone, or testosterone levels.

Medication-induced menstrual dysfunction could be due to drug-induced disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (H-P-O) axis, thus altering the estrogen and progesterone cycles that regulate menstruation (Kadir and Davies, 2013; Bradley and Gueye, 2016; James, 2016; Ryan, 2017; Thomas et al., 2020; Ramalho et al., 2021). HMB may follow several months of amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea during which the endometrium could not fall off normally, which can cause endometrial hyperplasia (Kadir and Davies, 2013; Bradley and Gueye, 2016; James, 2016; Thomas et al., 2020; Ramalho et al., 2021). According to this view, HMB may reflect a disorder of estrogen and progesterone secretion, independent of hyper-prolactin. In women with BP, valproate has been reported to induce hyperandrogenism, which leads to oligomenorrhea, consistent with an H-P-O disturbance (Death et al., 2005; Joffe et al., 2006a; Bilo and Meo, 2008; Sidhu et al., 2018). Notwithstanding, pharmacotherapeutic-induced hyper-prolactin reflects a cryptorrhea phenomenon, the effects of which should be elucidated in a prospective cohort study. Psychiatric medications have secondary effects on the hemic system (Dahl, 1986; Krieger et al., 2004; Dietrich-Muszalska and Wachowicz, 2017; Pavlidi et al., 2021), and thus can cause or exacerbate coagulation disorders and abnormal bleeding, which can lead to HMB in women (Yasui-Furukori et al., 2012; Kranz et al., 2021). Although the precise mechanisms underlying these drug effects are unknown, physicians should be screening for HMB in the course of female psychiatric patient monitoring.

Surprisingly, among the cognitive functions followed, impaired visual learning performance emerged as being strongly associated with HMB. The reasons for this association are difficult to speculate about, but certainly worthy of future examination.

Lithium was unique among the analyzed medications in that it seemed to be a protective factor against HMB. Interestingly, lithium has also been shown to be a protective factor against cognitive impairment (Matsunaga et al., 2015; Ochoa, 2022). However, to the best of our knowledge, lithium effects on cognitive performance cannot explain its protective influence on HMB in women with severe mental illnesses.

HMB awareness among psychiatrists was found to be abysmal at 2.28%, particularly given the substantial prevalence of HMB in the patient population served by the surveyed psychiatrists. Common remedies for menstrual dysfunction, including aripiprazole and traditional Chinese medicines, were ineffective for alleviating HMB in our patient sample. Thus, there is an urgent need to alert psychiatrists of this epidemiological information, especially those who treat women with BP.

This study had a number of limitations that warrant discussion. First, it was a retrospective study employing the PABC to assess HMB history. The validity of the PBAC for assessing menstrual bleeding in prior months needs to be confirmed. The patients in this sample were confirmed to have a good memory according to the Wechsler memory scale and used the last menstrual bleeding status as a reference standard.

Second, although our data pointed to blood sugar variables, including HbA1c, as risk factors for HMB. Even HbA1c, which can only reflect blood sugar alterations over the preceding 3 months, cannot reflect 18 months of physiological history. Although our data support the view that HbA1c alterations may trigger HMB (Sharawy et al., 2016; van Baar et al., 2022), the mechanisms of such an effect, if true, remain to be clarified.

Third, although valproate use, theoretically, might explain the observed higher incidence of HMD in BP patients than in the MDD and SCZ groups due to valproate disruption of the H-P-O axis, nearly half of the patients in the MDD and SCZ groups were using valproate as a synergist. In a prior study of patients with SCZ, antipsychotic agents were not significantly related to testosterone or estradiol levels (O'Donovan et al., 2002). Although antidepressants cannot induce testosterone upregulation, testosterone has been reported to have an antidepressive effect by way of its reducing influence on monoamine oxidase A levels 88. Related to this concern, as discussed above, our data do not enable us to disentangle how high blood sugar levels and hyperprolactinemia may influence HMB risk via effects on the H-P-O-axis. Thus, there are as yet to be clarified sophisticated relationships among therapeutic agents and H-P-O axis pathways.

Although obesity has been previously associated with HMB risk (Seif et al., 2015), the present data cannot confirm this putative relationship because antipsychotic medication use itself was associated with increasing BMI in women with SCZ. Additionally, we did not assess HMB prior to mental illness onset. Although we did not find an association between ECT and HMB, a minor portion of our sample received ECT and thus we are not confident in ruling out a possible association.

Notably, the remedies recommended to our patients for menstrual dysfunction, primarily aripiprazole and traditional Chinese medicines did not normalize menstrual function. Indeed, remarkably, every individual in our sample (N = 3,094) reported having irregular menstrual periods. Finally, the results obtained in the present treatment-resistant patient sample may not generalize to treatment response patients; only ∼30% of patients with BP, MDD, or SCZ (beyond this study) are treatment resistant.

Conclusion

The present study yielded five pivotal pieces of clinical reference information. 1) The risk for HMB in young adult women is substantial. 2) Psychiatric medications may induce hyperglycemia and poor visual learning performance within three treatment months, and medication dosage is related to HMB risk. Thus, healthcare providers should be screening for the emergence of HMB and adjust treatment plans accordingly. 3) Women with BP who are treated with valproate are at heightened risk of HMB, suggesting that perhaps valproate therapy should be prescribed less frequently for BP, at least in young women. 4) Lithium is a protective factor against HMB. Finally, 5) psychiatrists’ awareness of HMB risk in women with severe mental illness is extremely low. Hence, there is a need to inform psychiatric clinicians of the need to pay attention to HMB risk.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by ethic committee of Tianjin Fourth Center Hospital of Tianjin Medical University (No. ZC-R-0001). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CJZ, HT, WL, WY, and CZ conceived and designed this study. JS, CZ, XS, and HW contributed to data analysis and interpretation, wrote and revised the manuscript. XM, RL, HY, GC, JS, JZ, ZC, CL, LC, GC, YX, SL, CZ, QL, YZ, SJ, CXL, QZ, LL, LY, JC, and QL contributed to data collection, analysis and interpretation.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871052, 82171503 to CZ); the Key Projects of the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin, China (17JCZDJC35700 to CZ); the Tianjin Health Bureau Foundation (2014KR02 to CJZ; and the Tianjin Science and Technology Bureau (15JCYBJC50800 to HT).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

An, H., Du, X., Huang, X., Qi, L., Jia, Q., Yin, Q., et al. (2018). Obesity, Altered Oxidative Stress, and Clinical Correlates in Chronic Schizophrenia Patients. Transl. Psychiatry 8, 258. doi:10.1038/s41398-018-0303-7

APA (2016). Psychiatric Services in Correctional Facilities. Third Edition. Virginia, US: American Psychiatric Association. 978-970-89042-89464-89043.

APA, American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Virginia, US: American Psychiatric Association.

Aranth, J., and Lindberg, C. (1992). Bleeding, a Side Effect of Fluoxetine. Am. J. Psychiatry 149, 412. doi:10.1176/ajp.149.3.412a

Arias-de la Torre, J., Ronaldson, A., Prina, M., Matcham, F., Pinto Pereira, S. M., and Hatch, S. L. (2021). Depressive Symptoms During Early Adulthood and the Development of Physical Multimorbidity in the UK: An Observational Cohort Study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2, e801–e810. doi:10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00259-2

Baandrup, L. (2020). Polypharmacy in Schizophrenia. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 126, 183–192. doi:10.1111/bcpt.13384

Beck, A. T., Baruch, E., Balter, J. M., Steer, R. A., and Warman, D. M. (2004). A New Instrument for Measuring Insight: The Beck Cognitive Insight Scale. Schizophr. Res. 68, 319–329. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00189-0

Bekhbat, M., Chu, K., Le, N. A., Woolwine, B. J., Haroon, E., Miller, A. H., et al. (2018). Glucose and Lipid-Related Biomarkers and the Antidepressant Response to Infliximab in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 98, 222–229. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.09.004

Besag, F. M. C., Vasey, M. J., and Salim, I. (2021). Is Adjunct Aripiprazole Effective in Treating Hyperprolactinemia Induced by Psychotropic Medication? A Narrative Review. CNS Drugs 35, 507–526. doi:10.1007/s40263-021-00812-1

Bilo, L., and Meo, R. (2008). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Women Using Valproate: a Review. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 24, 562–570. doi:10.1080/09513590802288259

Birchwood, M., Smith, J., Drury, V., Healy, J., Macmillan, F., and Slade, M. (1994). A Self-Report Insight Scale for Psychosis: Reliability, Validity and Sensitivity to Change. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 89, 62–67. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01487.x

Bo, Q., Xing, X., Li, T., Mao, Z., Zhou, F., and Wang, C. (2021). Menstrual Dysfunction in Women with Schizophrenia During Risperidone Maintenance Treatment. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 41, 135–139. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001344

Bora, E., Akdede, B. B., and Alptekin, K. (2017). The Relationship Between Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia and Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Med. 47, 1030–1040. doi:10.1017/S0033291716003366

Borbély, É., Simon, M., Fuchs, E., Wiborg, O., Czéh, B., and Helyes, Z. (2022). Drug Developmental Strategies for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Br. J. Pharmacol. 179, 1146–1186. doi:10.1111/bph.15753

Bowie, R. C., Best, M. W., Depp, C., Mausbach, T. B., Patterson, T. L., Pulver, A. E., et al. (2018). Cognitive and Functional Deficits in Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia as a Function of the Presence and History of Psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 20 (7), 604–613. doi:10.1111/bdi.12654

Bradley, L. D., and Gueye, N. A. (2016). The Medical Management of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Reproductive-Aged Women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 214, 31–44. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.044

Calaf, J., Cancelo, M. J., Andeyro, M., Jiménez, J. M., Perelló, J., Correa, M., et al. (2020). Development and Psychometric Validation of a Screening Questionnaire to Detect Excessive Menstrual Blood Loss that Interferes in Quality of Life: The SAMANTA Questionnaire. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 29, 1021–1031. doi:10.1089/jwh.2018.7446

Chen, H., Wang, X. T., Bo, Q. G., Zhang, D. M., Qi, Z. B., Liu, X., et al. (2017). Menarche, Menstrual Problems and Suicidal Behavior in Chinese Adolescents. J. Affect Disord. 209, 53–58. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.027

Culpepper, L., Lam, R. W., and McIntyre, R. S. (2017). Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Depression: Awareness, Assessment, and Management. J. Clin. Psychiatry 78, 1383–1394. doi:10.4088/JCP.tk16043ah5c

Dahl, S. G. (1986). Plasma Level Monitoring of Antipsychotic Drugs. Clinical Utility. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 11, 36–61. doi:10.2165/00003088-198611010-00003

Davies, J., and Kadir, R. A. (2017). Heavy Menstrual Bleeding: An Update on Management. Thromb. Res. 151 (Suppl. 1), S70–s77. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(17)30072-5

Death, A. K., McGrath, K. C., and Handelsman, D. J. (2005). Valproate Is an Anti-Androgen and Anti-Progestin. Steroids 70, 946–953. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2005.07.003

Dietrich-Muszalska, A., and Wachowicz, B. (2017). Platelet Haemostatic Function in Psychiatric Disorders: Effects of Antidepressants and Antipsychotic Drugs. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 18, 564–574. doi:10.3109/15622975.2016.1155748

El-Nashar, S. A., Hopkins, M. R., Barnes, S. A., Pruthi, R. K., Gebhart, J. B., Cliby, W. A., et al. (2010). Health-Related Quality of Life and Patient Satisfaction after Global Endometrial Ablation for Menorrhagia in Women with Bleeding Disorders: A Follow-Up Survey and Systematic Review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 202, 348. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.032

Elboga, G., and Sayiner, Z. A. (2018). Rare Cause of Manic Period Trigger in Bipolar Mood Disorder: Testosterone Replacement. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, bcr2018225108. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-225108

Elias, A., Thomas, N., and Sackeim, H. A. (2021). Electroconvulsive Therapy in Mania: A Review of 80 Years of Clinical Experience. Am. J. Psychiatry 178, 229–239. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030238

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., and Williams, J. B. W. (1996). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

Flores-Ramos, M., Becerra-Palars, C., Hernández González, C., Chavira, R., Bernal-Santamaría, N., and Martínez Mota, L. (2020). Serum Testosterone Levels in Bipolar and Unipolar Depressed Female Patients and the Role of Medication Status. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 24, 53–58. doi:10.1080/13651501.2019.1680696

Fu, L. H., Schwartz, J., Moy, A., Knaplund, C., Kang, M. J., Schnock, K. O., et al. (2020). Development and Validation of Early Warning Score System: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Biomed. Inf. 105, 103410. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2020.103410

García-Carmona, J. A., Simal-Aguado, J., Campos-Navarro, M. P., Valdivia-Muñoz, F., and Galindo-Tovar, A. (2021). Evaluation of Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics with the Corresponding Oral Formulation in a Cohort of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Real-World Study in Spain. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 36, 18–24. doi:10.1097/yic.0000000000000339

Gu, L., Huang, J., Tan, J., Wei, Q., Jiang, H., Shen, T., et al. (2016). Impact of TLR5 Rs5744174 on Stroke Risk, Gene Expression and on Inflammatory Cytokines, and Lipid Levels in Stroke Patients. Neurol. Sci. 37, 1537–1544. doi:10.1007/s10072-016-2607-9

Haddad, P. M., and Wieck, A. (2004). Antipsychotic-Induced Hyperprolactinaemia: Mechanisms, Clinical Features and Management. Drugs 64, 2291–2314. doi:10.2165/00003495-200464200-00003

Hayasaka, Y., Purgato, M., Magni, L. R., Ogawa, Y., Takeshima, N., Cipriani, A., et al. (2015). Dose Equivalents of Antidepressants: Evidence-Based Recommendations from Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Affect Disord. 180, 179–184. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.021

Hidalgo, B., and Goodman, M. (2013). Multivariate or Multivariable Regression? Am. J. Public Health 103, 39–40. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300897

Howes, O. D., Thase, M. E., and Pillinger, T. (2021). Treatment Resistance in Psychiatry: State of the Art and New Directions. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 58–72. doi:10.1038/s41380-021-01200-3

Huhn, M., Nikolakopoulou, A., Schneider-Thoma, J., Krause, M., Samara, M., Peter, N., et al. (2019). Comparative Efficacy and Tolerability of 32 Oral Antipsychotics for the Acute Treatment of Adults with Multi-Episode Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet 394, 939–951. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31135-3

Hui Poon, S., Sim, K., and Baldessarini, R. J. (2015). Pharmacological Approaches for Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 13, 592–604. doi:10.2174/1570159x13666150630171954

Iles, S., and Gath, D. (1989). Psychological Problems and Uterine Bleeding. Baillieres Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 3, 375–389. doi:10.1016/s0950-3552(89)80028-8

James, A. H. (2016). Heavy Menstrual Bleeding: Work-Up and Management. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2016, 236–242. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.236

Jang, E. H., Lee, J. H., and Kim, S. A. (2021). Acute Valproate Exposure Induces Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Autophagy with FOXO3a Modulation in SH-Sy5y Cells. Cells 10, 2522. doi:10.3390/cells10102522

Joffe, H., Cohen, L. S., Suppes, T., McLaughlin, W. L., Lavori, P., Adams, J. M., et al. (2006a). Valproate Is Associated with New-Onset Oligoamenorrhea with Hyperandrogenism in Women with Bipolar Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 59, 1078–1086. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.017

Joffe, H., Kim, D. R., Foris, J. M., Baldassano, C. F., Gyulai, L., Hwang, C. H., et al. (2006b). Menstrual Dysfunction Prior to Onset of Psychiatric Illness Is Reported More Commonly by Women with Bipolar Disorder Than by Women with Unipolar Depression and Healthy Controls. J. Clin. Psychiatry 67, 297–304. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0218

Kadir, R. A., and Davies, J. (2013). Hemostatic Disorders in Women. J. Thromb. Haemost. 11 (Suppl. 1), 170–179. doi:10.1111/jth.12267

Kenna, H. A., Jiang, B., and Rasgon, N. L. (2009). Reproductive and Metabolic Abnormalities Associated with Bipolar Disorder and its Treatment. Harv Rev. Psychiatry 17, 138–146. doi:10.1080/10673220902899722

Kennedy, J. L., Altar, C. A., Taylor, D. L., Degtiar, I., and Hornberger, J. C. (2014). The Social and Economic Burden of Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 29, 63–76. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e32836508e6

Ko, J. K. Y., Lao, T. T., and Cheung, V. Y. T. (2021). Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart for Evaluating Heavy Menstrual Bleeding in Asian Women. Hong Kong Med. J. 27, 399–404. doi:10.12809/hkmj208743

Konicki, W., Soletic, L. C., Karlis, V., and Aaron, C. (2021). Point-of-Care Pregnancy Testing in Outpatient Sedation Anesthesia: Experience from an Urban Hospital-Based Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinic. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 79, 2444–2447. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2021.05.013

Kranz, G. S., Spies, M., Vraka, C., Kaufmann, U., Klebermass, E. M., Handschuh, P. A., et al. (2021). High-Dose Testosterone Treatment Reduces Monoamine Oxidase A Levels in the Human Brain: A Preliminary Report. Psychoneuroendocrinology 133, 105381. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105381

Krieger, K., Klimke, A., and Henning, U. (2004). Antipsychotic Drugs Influence Transport of the Beta-Adrenergic Antagonist [3H]-Dihydroalprenolol into Neuronal and Blood Cells. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 5, 100–106. doi:10.1080/15622970410029918

Kumar, A., Datta, S. S., Wright, S. D., Furtado, V. A., and Russell, P. S. (2013). Atypical Antipsychotics for Psychosis in Adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 15, Cd009582. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009582.pub2

Lee, J., Kim, M., Chae, H., Kim, Y., Park, H. I., Kim, Y., et al. (2013). Evaluation of Enzymatic BM Test HbA1c on the JCA-Bm6010/C and Comparison with Bio-Rad Variant II Turbo, Tosoh HLC 723 G8, and AutoLab Immunoturbidimetry Assay. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 51, 2201–2208. doi:10.1515/cclm-2013-0238

Lethaby, A., Hickey, M., Garry, R., and Penninx, J. (2009). Endometrial Resection/Ablation Techniques for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. Cd001501 7, CD001501. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001501.pub3

Lethaby, A., Hussain, M., Rishworth, J. R., and Rees, M. C. (2015). Progesterone or Progestogen-Releasing Intrauterine Systems for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 30, Cd002126. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002126.pub3

Leucht, S., Wahlbeck, K., Hamann, J., and Kissling, W. (2003). New Generation Antipsychotics versus Low-Potency Conventional Antipsychotics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 361, 1581–1589. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13306-5

Lo, B. S., Szuhany, K. L., Kredlow, M. A., Wolfe, R., Mueser, K. T., McGurk, S. R., et al. (2016). A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery in Severe Mental Illness. Schizophr. Res. 175 (1–3), 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.03.013

Matsunaga, S., Kishi, T., Annas, P., Basun, H., Hampel, H., and Iwata, N. (2015). Lithium as a Treatment for Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 48, 403–410. doi:10.3233/JAD-150437

McAllister-Williams, R. H. (2006). Relapse Prevention in Bipolar Disorder: A Critical Review of Current Guidelines. J. Psychopharmacol. 20, 12–16. doi:10.1177/1359786806063071

McCleery, A., Green, M. F., Hellemann., G. S., Baade, L. E., Gold, G. M., Keefe, R. S. E., et al. (2015). Latent Structure of Cognition in Schizophrenia: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) Psychol. Med 45 (12), 2657–2666. doi:10.1017/S0033291715000641

McIntyre, R. S., Berk, M., Brietzke, E., Goldstein, B. I., López-Jaramillo, C., Kessing, L. V., et al. (2020). Bipolar Disorders. Lancet 396, 1841–1856. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31544-0

Meyer, J. M. (2002). A Retrospective Comparison of Weight, Lipid, and Glucose Changes Between Risperidone- and Olanzapine-Treated Inpatients: Metabolic Outcomes After 1 Year. J. Clin. Psychiatry 63, 425–433. doi:10.4088/jcp.v63n0509

Mizuno, Y., Suzuki, T., Nakagawa, A., Yoshida, K., Mimura, M., Fleischhacker, W. W., et al. (2014). Pharmacological Strategies to Counteract Antipsychotic-Induced Weight Gain and Metabolic Adverse Effects in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 1385–1403. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbu030

Muir, C. C., Treasurywala, K., McAllister, S., Sutherland, J., Dukas, L., Berger, R. G., et al. (2008). Enzyme Immunoassay of Testosterone, 17beta-Estradiol, and Progesterone in Perspiration and Urine of Preadolescents and Young Adults: Exceptional Levels in Men's Axillary Perspiration. Horm. Metab. Res. 40, 819–826. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1082042

Nick, T. G., and Campbell, K. M. (2007). Logistic Regression. Methods Mol. Biol. 404, 273–301. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-530-5_14

Nikolac Gabaj, N., Miler, M., Vrtarić, A., Hemar, M., Filipi, P., Kocijančić, M., et al. (2018). Precision, Accuracy, Cross Reactivity and Comparability of Serum Indices Measurement on Abbott Architect C8000, Beckman Coulter AU5800 and Roche Cobas 6000 C501 Clinical Chemistry Analyzers. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 56, 776–788. doi:10.1515/cclm-2017-0889

Nikoloulopoulos, A. K. (2012). A Multivariate Logistic Regression. Biostatistics 13, 1–3. doi:10.1093/biostatistics/kxr014

Noerpramana, N. P. (1997). Blood-Lipid Fractions: the Side-Effects and Continuation of Norplant Use. Adv. Contracept. 13, 13–37. doi:10.1023/a:1006512211238

O'Donovan, C., Kusumakar, V., Graves, G. R., and Bird, D. C. (2002). Menstrual Abnormalities and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Women Taking Valproate for Bipolar Mood Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 63, 322–330. doi:10.4088/jcp.v63n0409

Ochoa, E. L. M. (2022). Lithium as a Neuroprotective Agent for Bipolar Disorder: An Overview. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 42, 85–97. doi:10.1007/s10571-021-01129-9

Paavola, J. T., Väntti, N., Junkkari, A., Huttunen, T. J., von Und Zu Fraunberg, M., Koivisto, T., et al. (2019). von Und Zu Fraunberg Antipsychotic Use Among 1144 Patients After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Stroke 50, 1711–1718. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.119.024914

Padda, J., Khalid, K., Hitawala, G., Batra, N., Pokhriyal, S., Mohan, A., et al. (2021). Depression and its Effect on the Menstrual Cycle. Cureus 13, e16532. doi:10.7759/cureus.16532

Papakostas, G. I., Miller, K. K., Petersen, T., Sklarsky, K. G., Hilliker, S. E., Klibanski, A., et al. (2006). Serum Prolactin Levels Among Outpatients with Major Depressive Disorder During the Acute Phase of Treatment with Fluoxetine. J. Clin. Psychiatry 67, 952–957. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0612

Papp, M., Cubala, W. J., Swiecicki, L., Newman-Tancredi, A., and Willner, P. (2021). Perspectives for Therapy of Treatment-Resistant Depression. Br. J. Pharmacol. doi:10.1111/bph.15596

Paulzen, M., Haen, E., Stegmann, B., Hiemke, C., Gründer, G., Lammertz, S. E., et al. (2016). Body Mass Index (BMI) but Not Body Weight Is Associated with Changes in the Metabolism of Risperidone; A Pharmacokinetics-Based Hypothesis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 73, 9–15. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.07.009

Pavlidi, P., Kokras, N., and Dalla, C. (2021). Antidepressants' Effects on Testosterone and Estrogens: What Do We Know? Eur. J. Pharmacol. 899, 173998. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173998

Piatoikina, A. S., Lyakhova, A. A., Semennov, I. V., Zhilyaeva, T. V., Kostina, O. V., Zhukova, E. S., et al. (2022). Association of Antioxidant Deficiency and the Level of Products of Protein and Lipid Peroxidation in Patients with the First Episode of Schizophrenia. J. Mol. Neurosci. 72 (2), 217–225. doi:10.1007/s12031-021-01884-w

Pottegård, A., Lash, T. L., Cronin-Fenton, D., Ahern, T. P., and Damkier, P. (2018). Use of Antipsychotics and Risk of Breast Cancer: A Danish Nationwide Case-Control Study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 84, 2152–2161. doi:10.1111/bcp.13661

Pramodh, S. (2020). Exploration of Lifestyle Choices, Reproductive Health Knowledge, and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) Awareness Among Female Emirati University Students. Int. J. Womens Health 12, 927–938. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S272867

Ramalho, I., Leite, H., and Águas, F. (2021). Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Adolescents: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Acta Med. Port. 34, 291–297. doi:10.20344/amp.12829

Rasgon, N. L., Altshuler, L. L., Fairbanks, L., Elman, S., Bitran, J., Labarca, R., et al. (2005a). Reproductive Function and Risk for PCOS in Women Treated for Bipolar Disorder. Bipolar Disord. 7, 246–259. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00201.x

Rasgon, N. L., Reynolds, M. F., Elman, S., Saad, M., Frye, M. A., Bauer, M., et al. (2005b). Longitudinal Evaluation of Reproductive Function in Women Treated for Bipolar Disorder. J. Affect Disord. 89, 217–225. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.002

Reavey, J. J., Walker, C., Murray, A. A., Brito-Mutunayagam, S., Sweeney, S., Nicol, M., et al. (2021a). Obesity Is Associated with Heavy Menstruation that May Be Due to Delayed Endometrial Repair. J. Endocrinol. 249, 71–82. doi:10.1530/JOE-20-0446

Reavey, J. J., Walker, C., Nicol, M., Murray, A. A., Critchley, H. O. D., Kershaw, L. E., et al. (2021b). Markers of Human Endometrial Hypoxia Can Be Detected In Vivo and Ex Vivo During Physiological Menstruation. Hum. Reprod. 36, 941–950. doi:10.1093/humrep/deaa379

Reynolds, M. F., Sisk, E. C., and Rasgon, N. L. (2007). Valproate and Neuroendocrine Changes in Relation to Women Treated for Epilepsy and Bipolar Disorder: A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 14, 2799–2812. doi:10.2174/092986707782360088

Rossetti, A. O., and Alvarez, V. (2021). Update on the Management of Status Epilepticus. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 34, 172–181. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000899

Ryan, S. A. (2017). The Treatment of Dysmenorrhea. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 64, 331–342. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2016.11.004

Rybak, Y. E., Lai, K. S. P., Ramasubbu, R., Vila-Rodriguez, F., Blumberger, D. M., Chan, P., et al. (2021). Treatment-Resistant Major Depressive Disorder: Canadian Expert Consensus on Definition and Assessment. Depress Anxiety 38, 456–467. doi:10.1002/da.23135

Schlaff, W. D., Ackerman, R. T., Al-Hendy, A., Archer, D. F., Barnhart, K. T., Bradley, L. D., et al. (2020). Elagolix for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding in Women with Uterine Fibroids. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 328–340. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1904351

Schmidt, M. (1996). Rey Auditory and Verbal Learning Test: A Handbook. California.Western Psychological Services.

Seif, M. W., Diamond, K., and Nickkho-Amiry, M. (2015). Obesity and Menstrual Disorders. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 29, 516–527. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.10.010

Seppälä, A., Pylvänäinen, J., Lehtiniemi, H., Hirvonen, N., Corripio, I., Koponen, H., et al. (2021). Predictors of Response to Pharmacological Treatments in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr. Res. 236, 123–134. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2021.08.005

Shannon, M. (1993). An Empathetic Look at Overweight. CCL Fam. Found. 20 (3), 5. doi:10.1016/0892-8967(93)90132-b

Shapley, M., Croft, P. R., McCarney, R., and Lewis, M. (2000). Does Psychological Status Predict the Presentation in Primary Care of Women with a Menstrual Disturbance? Br. J. Gen. Pract. 50, 491–492.

Sharawy, M. H., El-Awady, M. S., Megahed, N., and Gameil, N. M. (2016). The Ergogenic Supplement β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate (HMB) Attenuates Insulin Resistance Through Suppressing GLUT-2 in Rat Liver. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 94, 488–497. doi:10.1139/cjpp-2015-0385

Sidhu, H. S., Srinivasa, R., and Sadhotra, A. (2018). Evaluate the Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs on Reproductive Endocrine System in Newly Diagnosed Female Epileptic Patients Receiving Either Valproate or Lamotrigine Monotherapy: A Prospective Study. Epilepsy Res. 139, 20–27. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.10.016

Sienaert, P., Lambrichts, L., Dols, A., and De Fruyt, J. (2013). Evidence-based Treatment Strategies for Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression: A Systematic Review. Bipolar Disord. 15, 61–69. doi:10.1111/bdi.12026

Sinclair, D. J. M., Zhao, S., Qi, F., Nyakyoma, K., Kwong, J. S. W., and Adams, C. E. (2019). Electroconvulsive Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 45, 730–732. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbz037

Solé, B., Jiménez, E., Torrent, C., Reinares, M., Bonnin, C. D. M., Torres, I., et al. (2017). Cognitive Impairment in Bipolar Disorder: Treatment and Prevention Strategies. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 20, 670–680. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyx032

Solmi, M., Fornaro, M., Ostinelli, E. G., Zangani, C., Croatto, G., Monaco, F., et al. (2020). Safety of 80 Antidepressants, Antipsychotics, Anti-Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Medications and Mood Stabilizers in Children and Adolescents with Psychiatric Disorders: A Large Scale Systematic Meta-Review of 78 Adverse Effects. World Psychiatry 19, 214–232. doi:10.1002/wps.20765

Stahl, S. M. (2021). Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. 5th edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Thomas, W., Downes, K., and Desborough, M. J. R. (2020). Bleeding of Unknown Cause and Unclassified Bleeding Disorders; Diagnosis, Pathophysiology and Management. Haemophilia 26, 946–957. doi:10.1111/hae.14174

Tian, T., Wang, D., Wei, G., Wang, J., Zhou, H., Xu, H., et al. (2021). Prevalence of Obesity and Clinical and Metabolic Correlates in First-Episode Schizophrenia Relative to Healthy Controls. Psychopharmacol. 238 (3), 745–753. doi:10.1007/s00213-020-05727-1

Tondo, L., Vázquez, G. H., and Baldessarini, R. J. (2014). Options for Pharmacological Treatment of Refractory Bipolar Depression. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 16, 431. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0431-y

Trifu, S., Sevcenco, A., Stănescu, M., Drăgoi, A. M., and Cristea, M. B. (2021). Efficacy of Electroconvulsive Therapy as a Potential First-Choice Treatment in Treatment-Resistant Depression (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 22, 1281. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10716

van Baar, A. C. G., Devière, J., Hopkins, D., Crenier, L., Holleman, F., Galvão Neto, M. P., et al. (2022). Durable Metabolic Improvements 2 Years After Duodenal Mucosal Resurfacing (DMR) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (REVITA-1 Study). Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 184, 109194. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109194

Vuong, K., McGeechan, K., Armstrong, B. K., and Cust, A. E. (2014). Risk Prediction Models for Incident Primary Cutaneous Melanoma: A Systematic Review. JAMA Dermatol 150, 434–444. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8890

Walters, J., and Jones, I. (2008). Clinical Questions and Uncertainty-Pprolactin Measurement in Patients with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. J. Psychopharmacol. 22, 82–89. doi:10.1177/0269881107086516

Wang, J., Zou, Y. Z., Cui, J. F., Fan, H. Z., Chen, R., Chen, N., et al. (2015). Revision of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Fourth Edition of Chinese Version (Adult Battery). Chin. Ment. Health J. 29, 53–59. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2015.01.010

Yasui-Furukori, N., Fujii, A., Sugawara, N., Tsuchimine, S., Saito, M., Hashimoto, K., et al. (2012). No Association Between Hormonal Abnormality and Sexual Dysfunction in Japanese Schizophrenia Patients Treated with Antipsychotics. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 27, 82–89. doi:10.1002/hup.1275

Keywords: bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, heavy menstrual bleeding, visual learning, lithium

Citation: Shan J, Tian H, Zhou C, Wang H, Ma X, Li R, Yu H, Chen G, Zhu J, Cai Z, Lin C, Cheng L, Xu Y, Liu S, Zhang C, Luo Q, Zhang Y, Jin S, Liu C, Zhang Q, Lv L, Yang L, Chen J, Li Q, Liu W, Yue W, Song X and Zhuo C (2022) Prevalence of Heavy Menstrual Bleeding and Its Associated Cognitive Risks and Predictive Factors in Women With Severe Mental Disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 13:904908. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.904908

Received: 26 March 2022; Accepted: 13 June 2022;

Published: 13 July 2022.

Edited by:

Francisco Lopez-Munoz, Camilo José Cela University, SpainReviewed by:

Haitham Jahrami, Arabian Gulf University, BahrainMarcin Siwek, Jagiellonian University, Poland

Copyright © 2022 Shan, Tian, Zhou, Wang, Ma, Li, Yu, Chen, Zhu, Cai, Lin, Cheng, Xu, Liu, Zhang, Luo, Zhang, Jin, Liu, Zhang, Lv, Yang, Chen, Li, Liu, Yue, Song and Zhuo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Liu, bG91amlhbnNoaXRqbWhAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Weihua Yue, ZHJ5dWVAYmptdS5lZHUuY24=; Xueqin Song, ZmNjc29uZ3hxQHp6dS5lZHUuY24=; Chuanjun Zhuo, Y2h1YW5qdW56aHVvdGptaEAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Jianmin Shan1,2†

Jianmin Shan1,2† Xiaoyan Ma

Xiaoyan Ma Langlang Cheng

Langlang Cheng Yong Xu

Yong Xu Chuanxin Liu

Chuanxin Liu Jiayue Chen

Jiayue Chen Weihua Yue

Weihua Yue Xueqin Song

Xueqin Song Chuanjun Zhuo

Chuanjun Zhuo