- 1Department of Pharmacy, Personalized Drug Therapy Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Southwestern Chinese Medicine Resources, Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, School of Pharmacy and College of Medical Technology, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, China

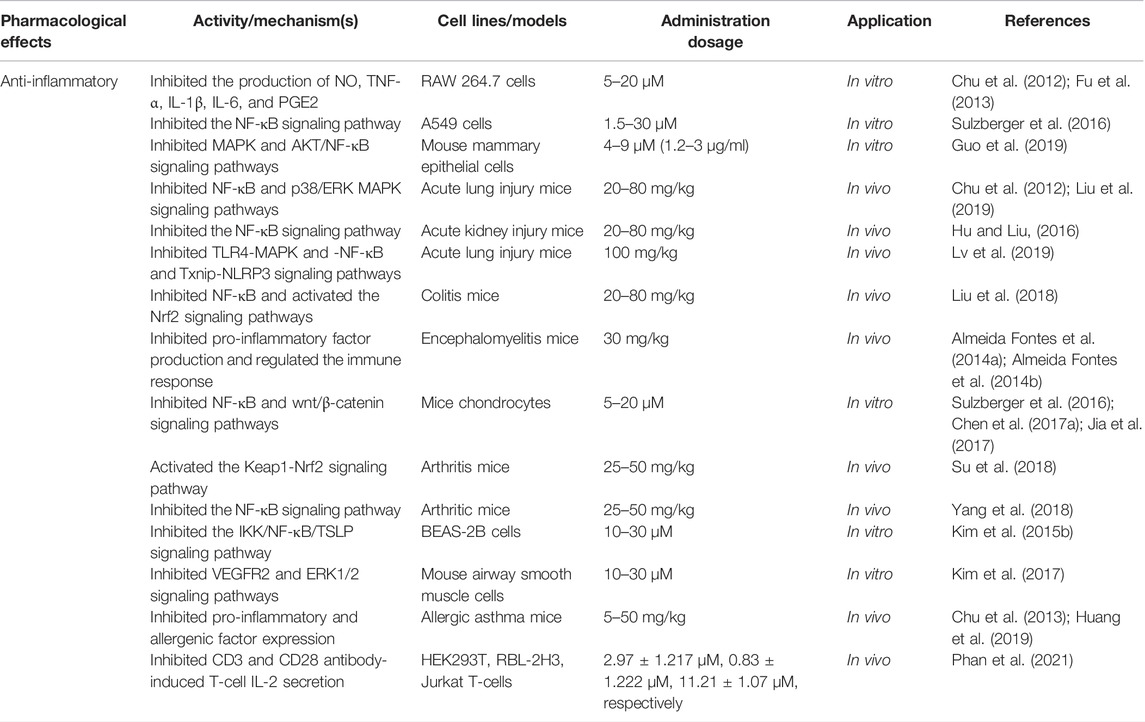

Licochalcone A (LA), a useful and valuable flavonoid, is isolated from Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. and widely used clinically in traditional Chinese medicine. We systematically updated the latest information on the pharmacology of LA over the past decade from several authoritative internet databases, including Web of Science, Elsevier, Europe PMC, Wiley Online Library, and PubMed. A combination of keywords containing “Licochalcone A,” “Flavonoid,” and “Pharmacological Therapy” was used to help ensure a comprehensive review. Collected information demonstrates a wide range of pharmacological properties for LA, including anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-parasitic, bone protection, blood glucose and lipid regulation, neuroprotection, and skin protection. LA activity is mediated through several signaling pathways, such as PI3K/Akt/mTOR, P53, NF-κB, and P38. Caspase-3 apoptosis, MAPK inflammatory, and Nrf2 oxidative stress signaling pathways are also involved with multiple therapeutic targets, such as TNF-α, VEGF, Fas, FasL, PI3K, AKT, and caspases. Recent studies mainly focus on the anticancer properties of LA, which suggests that the pharmacology of other aspects of LA will need additional study. At the end of this review, current challenges and future research directions on LA are discussed. This review is divided into three parts based on the pharmacological effects of LA for the convenience of readers. We anticipate that this review will inspire further research.

Introduction

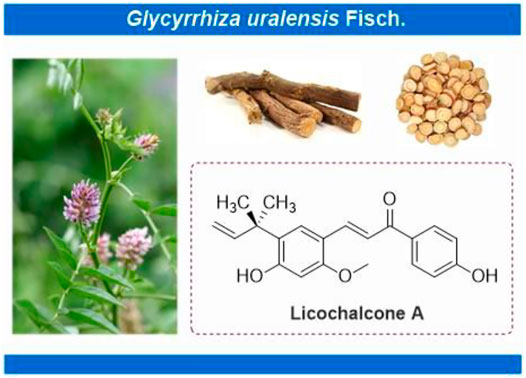

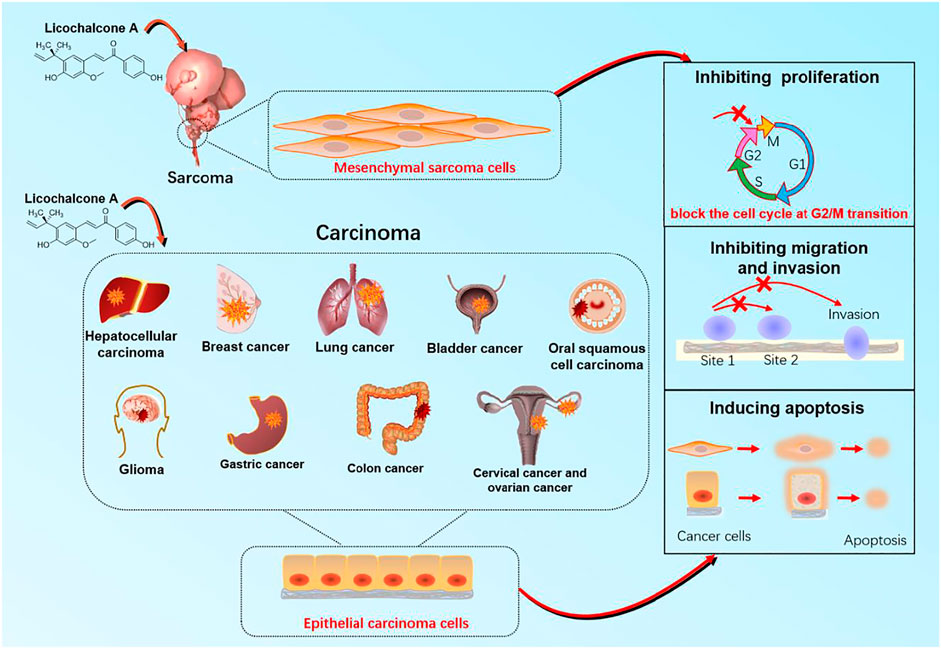

Licochalcone A (LA) (CAS No: 58749-22-7), with a molecular formula of C21H22O4, is a valuable flavonoid primarily extracted from roots of Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. (Figure 1) (Simmler et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). Licorice always functions as an adjuvant drug in traditional Chinese medicine to reduce the toxicity of other medicinal herbs or enhance their pharmacological effects. LA, thus, helps achieve the treatment or prevention of complex diseases (Jiang et al., 2020). Licorice demonstrates unique medicinal properties for clearing heat and toxins in clinical practice. LA has, thus, attracted the attention of pharmacologists worldwide (Jiang et al., 2020). Significant advancements have been witnessed in pharmacological research over the past decades. LA inhibits the proliferation of epithelial carcinoma and mesenchymal sarcoma cells. Examples include hepatocellular carcinoma, breast and colon cancer of epithelial origin, and melanoma of mesenchymal origin (Figure 2). Furthermore, LA demonstrates various pharmacological properties, including anti-inflammation, antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-parasitic, bone protection, neuroprotection, skin protection, and blood glucose and lipid regulation. The significant potential of LA for the treatment and prevention of clinical diseases indicates that an updated review regarding the therapeutic pharmacology of LA is timely. Therefore, we summarize the latest advancements for understanding the pharmacology of LA and explore the potential of this unique bioactive compound for use in the treatment of various diseases. We further provide useful and fundamental information for LA’s rational and secure application. This review is divided into three parts, 1) anticancer activities, 2) anti-inflammation activities, and 3) other pharmacological activities, for the convenience of readers.

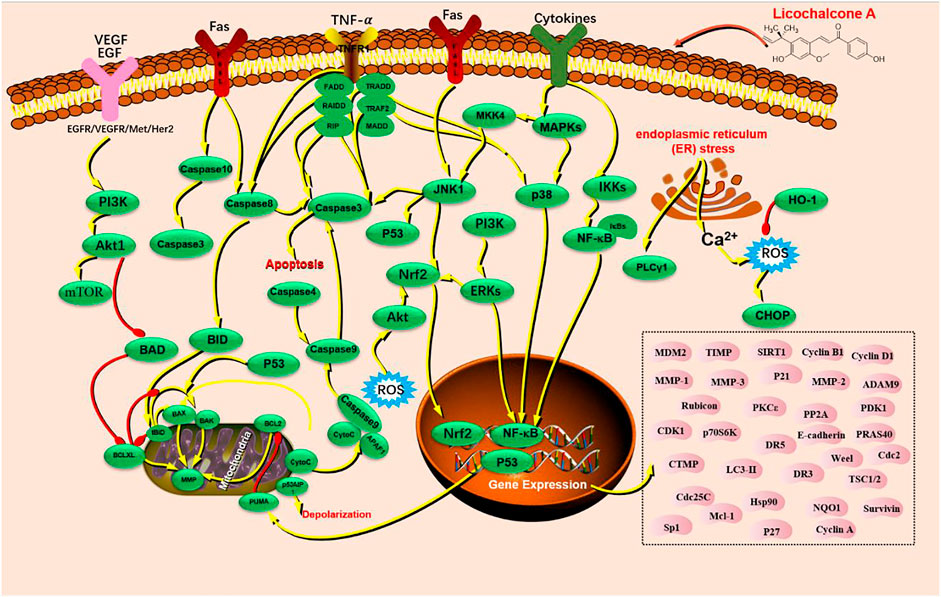

FIGURE 2. The target organ and cellular mechanisms for anticancer effect of licochalcone A with anticancer activity.

Anticancer Properties of LA

Cancers are major malignant diseases worldwide that seriously threaten human health and life. The significant feature of cancer is the rapid growth of abnormal cells that extends beyond their usual boundaries, invade adjoining tissues, and spread to other organs. These processes are termed proliferation, invasion, and migration (Kennedy and Salama, 2020; Siegel et al., 2021). The anticancer activity of LA is mainly associated with epithelial carcinoma and mesenchymal sarcoma cells. Cancers mediated by epithelial carcinoma cells include hepatocellular, glioma, breast, gastric, colon, lung, cervical, ovarian, bladder, and oral squamous cell. Melanoma is primary cancer caused by mesenchymal sarcoma cells (Figure 2). LA is mainly involved in cellular processes such as apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which underlie anticancer activity. LA activity is mediated via several signaling pathways, such as PI3K/Akt/mTOR, P53, NF-κB, and P38. Caspase-3 apoptosis, MAPK inflammatory, and Nrf2 oxidative stress signaling are also involved along with multiple therapeutic targets, including TNF-α, VEGF, Fas, FasL, PI3K, AKT, caspase-3, caspase-4, caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-10, P38, P53, BAX, BAD, BID, JNK1, IL-1β, IL-8, ECM, SOD, IFN-γ, IKK, HO-1, MAPK, and ERK (Figure 3).

Effects of LA on Inducing Apoptosis of Cancer Cells

As an effective pharmacological compound for cancer, LA induces apoptosis in different cancers via multiple pathways, including P13-Akt-mTOR, VEGFR2, c-Met, PLCγ1, MAPT, JNK/p38, and ERK1/2, along with a combination of regulatory targets. For instance, LA induces apoptosis in HepG2 cells (hepatocellular carcinoma cell line) via mitochondrial dysfunction. This activity relies on the upregulation of mRNA expression of targets, such as DR3, DR5, caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-10, Fas, Bad, Bax, Bcl-2, Bak, and PUMA. Downregulation of PKCε, p70S6K, and Akt is also described (Wang J. et al., 2018). Additionally, LA induced ER stress in HepG2 cells to induce apoptosis via activation of receptors of VEGFR2 and c-Met, phosphorylation of phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1), and enhancing cytosolic Ca2+ release from the ER (Choi A. Y. et al., 2014). LA induced MCF-7 cell (breast cancer cell line) apoptosis at different autophagy and intrinsic pathways doses. Doses of 5–50 μM induced autophagy and apoptosis of MCF-7 by inhibiting PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling, thereby increasing caspase-3 activity, decreasing expression of B-cell lymphoma-2, and triggering the release of cytochrome from mitochondria into the cytoplasm (Xue et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019b). Lower doses (5–15 μM) activated intrinsic pathway-mediated apoptosis involving upregulation of Bax expression and PARP cleavage, downregulation of Bcl-2 and Cyclin D1, and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Buso Bortolotto et al., 2017).

As for lung cancer, LA induced apoptosis in A549 lung cancer cells by increasing the expression of apoptotic proteins and decreasing the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (Lin Y. J. et al., 2019). Furthermore, relatively low doses (10–15 μM) induced apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, such as A549 and H460 cells, by inducing ER stress. LA upregulated caspase-3 expression and increased PARP cleavage. CHOP expression was elevated in parallel (Tang et al., 2016; Qiu et al., 2017). Blocking the CHOP-mediated pathway inhibited the expression of downstream apoptotic proteins at a higher dose (40 μM) (Chen et al., 2018). LA significantly activated ERK and p38 in A549 and H460 cells in a time-dependent manner. LA also inhibited the activity of JNK, suppressed the expression of c-IAP1, c-IAP2, XIAP, Survivin, c-FLIPL, and RIP1, and attenuated LA-induced induction of autophagy (Luo et al., 2021). LA also promoted the degradation of EGFR, Met, Her2, and Akt through inactivating EGFR/Met-Akt signaling, resulting in apoptosis of gefitinib-resistant NSCLC cells (H1975) (Seo, 2013). Strikingly, LA was a protein synthesis inhibitor, which reduced both cap-dependent and independent translation. LA may inhibit the phosphorylation of 4EBP1 (Ser 65) and activate the PERK-eIF2α pathway to inhibit PD-L1 translation. Moreover, LA-induced ROS production in lung cancer cells is time-dependent (Yuan et al., 2021). LA thus displays a potential for use in cancer immunotherapy.

LA primarily induced apoptosis in bladder cancer cells through mitochondrial stress combined with ER stress. The former, observed at LA doses of 10–80 μM, induced T24 cells (bladder cancer cell line) apoptosis in a complex fashion. Mitochondrial membrane potential was decreased, and mRNA expression of Apaf-1, caspase-9, and caspase-3 was upregulated. These actions increased PARP cleavage and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and increased intracellular Ca2+ level and ROS production. Detailed mechanisms of this latter activity require more in-depth studies (Yuan et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2016; Hong et al., 2019). LA also induced apoptosis in five gastric cell lines –GES-1, MKN-28, SGC7901, AGS, and MKN-45 (Xiao et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2017). LA induced BGC-823 cell apoptosis through ROS-mediated activation of MAPKs and PI3/AKT signaling at a higher dose (Hao et al., 2015). Hexokinase 2Â (HK2) expression was downregulated at a lower dose, attenuating glycolysis elevation and inducing apoptosis in MKN-45 and SGC7901 cells (Wu J. et al., 2018).

Moreover, LA induced apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma with distinct mechanisms at different doses. In HN22 and HSC4 cells, LA induced apoptosis via downregulating the expression of specificity protein 1 (Sp1), upregulating Bax, Bid, Bcl-xl, caspase-3, and PARP cleavage with doses of 10–40 μM (Cho et al., 2014). In addition, LA induced apoptosis in KB cells, relying on activation of caspase-dependent factor associated suicide ligand (FasL) mediated death receptor pathway. This action induced upregulation of FasL and activation of caspase-8 and -3 along with PARP cleavage (Kim et al., 2014). In SCC-25 cells (oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line), LA (15–296 μM) induced both death receptor and mitochondrial apoptotic pathways via activation of caspase-3 (Zeng et al., 2014). Remarkably, LA showed an excellent ability to induce apoptosis in glioma stem cells (GS-Y01, GS-Y03, U87GS, GS-NCC01, and A172GS) at an attractive dosage (2–12.5 μM) by inducing mitochondrial fragmentation via activating of caspases-3, -8, and -9, combined with reducing mitochondrial membrane potential and inhibiting ATP production in vitro (Kuramoto et al., 2017).

The literature also showed that LA induced apoptosis and autophagy in SiHa (Tsai et al., 2015) and HeLa cervical cancer cells (Szliszka et al., 2012), human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells (HONE-1, NPC-39, and NPC-BM) (Chuang et al., 2019), human pharyngeal squamous carcinoma FaDu cells (Yang et al., 2014; Park et al., 2015), OVCAR-3 and SK-OV-3 ovarian cancer cells (Lee et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013), B16 melanoma cells (Chen et al., 2019), human osteosarcoma 143B cells (Lin R. C. et al., 2019), malignant pleural mesothelioma (MSTO-211H and H28 cells) (Kim K. H. et al., 2015).

Effects of LA on Inhibiting Proliferation of Cancer Cells

Unlimited proliferation is a crucial feature of cancer cells. The pharmacological ability to inhibit proliferation is a crucial aspect of the anticancer effects of LA. Generally, inhibition of cancer cell proliferation reflects blocking the cell cycle at different transition phases via regulating specific mRNAs and protein levels, such as Wee1, P21, Cyclins, MDM2, Survivin, and CDK1. Occasionally, LA acts directly as a selective agonist or inhibitor involving JNK1, Ras homolog, R132C-mutant IDH1, and Sp1.

In detail, numerous studies indicated that LA blocked the cell cycle at the G2/M transition at different doses. For instance, LA blocked the cell cycle in HepG2 cells by increasing the expression of Weel, P21, Cyclin D1, and JNK1 and decreasing the expression of Survivin, Cyclin B1, and CDK1 using doses of 30–70 μM (Wang J. et al., 2018). Similarly, blocking at G2/M in NSCLC cells reflected downregulation of expression of MDM2, Cyclin B1, Cdc2, and Cdc25C at doses of 2.5–80 μM (Qiu et al., 2017). Also, LA stopped the cell cycle in T24 at the G2/M transition by downregulating the expression of Cyclin A, Cyclin B1, Wee1 and upregulating cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 at a dose of 10–60 μM (Jiang et al., 2014; Hong et al., 2019). Cell cycle progression in MKN-28, MKN-45, and AGS cells (gastric cancer and colon cancer cell lines) was similarly blocked via upregulation of expression of retinoblastoma and downregulation of Cyclin A, Cyclin B, and MDM2 at doses of 5–50 μM (Xiao et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2017). Doses of approximately 10–40 μM blocked the U87 glioma cell cycle at G0/G1 and G2/M phases (Lu et al., 2018) and osteosarcoma HOS cells at G2/M transition (Shen et al., 2019). Additionally, LA significantly inhibited the expression of PD-L1 by blocking the interaction between p65 and Ras, thus inhibiting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis (Liu et al., 2021).

LA also inhibits the proliferation of cancer cells directly by interaction with proteins and signaling. LA directly inhibited p38/JNK/ERK signaling in HepG2 cells and inhibited proliferation, and induced apoptosis in parallel (Chen X. et al., 2017). Furthermore, LA activated miR-142-3p to enhance the expression of Ras homolog enriched in the brain (Rheb) and subsequently activated mTOR signaling to inhibit proliferation, attenuate melanin production, and induce apoptosis in A375 and B16 melanoma cells (Barry and Parsons, 2016; Zhang et al., 2020). Another document indicated that LA inhibited Cyclin D1 expression resulting in cell cycle arrest at G1 in MCF-7 cells (Buso Bortolotto et al., 2017). In addition, LA (10–30 μM) also suppressed Sp1 to inhibit proliferation in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (breast cancer cell lines) (Kang et al., 2017). Moreover, in different cell models, LA exhibited distinct oral squamous cell carcinoma mechanisms. In SCC-25 cells, LA inhibited proliferation by blocking the cell cycle at S and G2/M phases (Zeng et al., 2014), while in HN22 and HSC4 cells, proliferation was blocked by inhibiting Sp1 expression and downstream related proteins, including p27, p21, Cyclin D1, Mcl-1 and Survivin (Cho et al., 2014). As a selective inhibitor of R132C-mutant IDH1, LA inhibited the proliferation of sarcoma HT-1080 cells with an acceptable IC50 = 5.176 μM (Hu et al., 2020). Notably, 30 μmol/L LA treatment for 24 h significantly reduced cell viability of Arkansas P1 cells (ARP1) and Ontario Cancer Institute myeloma 5 cells (OCI-MY5) (Bai et al., 2021).

Effects of LA on Inhibiting Migration and Invasion of Cancer Cells

Carcinoma cells own the ability to invade and migrate from their usual location to adjoining tissues and spread to other organs. Thus, inhibition of migration and invasion are essential aspects of anticancer activity. LA downregulated uPA expression in hepatocellular carcinoma by suppressing MKK4/JNK and NF-κB signaling and inhibited invasion and migration of HA22T/VGH and SK-Hep-1 cells (hepatocellular carcinoma cell models) at 5–20 μM (Tsai et al., 2014; Wu M. H. et al., 2018). Furthermore, 5–40 μΜ LA blocked the expression of E-cadherin and vimentin by suppressing MAPK and AKT signaling. This action inhibited invasion and migration in MDA-MB-231 cells (Huang et al., 2019b). Together with the AKT signaling pathway and downstream transcription factors Sp1 expression interruption, LA exhibited the ability to inhibit migration and invasion of A549 and H460 cells at relatively lower doses (2–20 μM) (Huang et al., 2014). LA inhibited oral squamous cell carcinoma proliferation, invasion, and migration via PI3K/AKT signaling (Hao et al., 2019).

Other Aspects of Anticancer Effects

Apart from the therapeutic effects during carcinoma progression, LA also displays other anticancer activities for protecting cellular DNA, impairing pathogenicity, modulating the immune response, suppressing drug resistance, and attenuating vomiting.

As mentioned under Effects of LA on Inducing Apoptosis of Cancer Cells, LA enhanced cytosolic Ca2+ release from ER in HepG2 cells. This action further induced ROS accumulation and increased effective doses of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) (Choi A. Y. et al., 2014), thus improving the efficacy of these anticarcinogens. LA also reduced the efflux of doxorubicin and temozolomide from BCRP-mediated BCRP-MDCKII cells by downregulating the expression of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) (Fan et al., 2019). Based on DEGs and GO and KEGG enrichment, LA showed antitumor activity against HepG2 cells, in which MAPK and FoxO signaling played essential roles (Wang et al., 2021). In gefitinib-resistant non-small cell lung cancer cells (H1975), LA also reduced Hsp90 activity in gefitinib-resistant NSCLC cells (H1975) via binding to the N-terminal ATP binding site of Hsp90 to reduce drug resistance (Seo, 2013).

In addition to reducing drug resistance, low doses of LA (2–10 μM) enhanced the positive correlation between the activation of quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) and Keap1-Nrf2 signaling HepG2-ARE-C8 cells. LA protected cellular DNA from oxidative stress-induced damage and assisted the development of a prevention strategy against cancer (Hajirahimkhan et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015; Wang S. et al., 2018). Also, chemoproteomic profiling analysis suggested that LA could attenuate the pathogenicity of triple-negative breast cancers by inhibiting the production of prostaglandin reductase (Roberts et al., 2017). For bladder cancer, LA inhibited arginine methyltransferase (PRMT) activity in bladder cancer by targeting CARM1, thereby downregulating the expression of an epigenetic modification enzyme (Cheng and Bedford, 2011).

Furthermore, LA exhibited various effects via different mechanisms in vivo. For instance, the administration of LA (40 mg/kg) to C3H/HeN mice bearing UM-UC-3 cells enhanced the activity of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and counts of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T regulatory T cells. Thus, LA might treat bladder cancer by modulating the tumor immune microenvironment (Zhang et al., 2016). Administration of 10 mg/kg of LA attenuated the development of AngII-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm in mice through inhibiting expression of miR-181b, upregulating SIRT1/HO-1 signaling, and suppressing elastin degradation, matrix metalloproteinase and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Hou et al., 2019). Finally, LA inhibited 5-HT3 receptors, which are crucial mediators of nausea. Licorice has been used to treat stomach ulcers, gastrointestinal inflammation, and respiratory diseases (Lee et al., 2008). LA may be involved in regulating peristalsis and digestion to improve symptoms of functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome. In one study, licorice extract exhibited the strongest 5-HT3 inhibition of the tested extracts, and LA was identified as a partial antagonist of 5-HT3 receptors (Herbrechter et al., 2015).

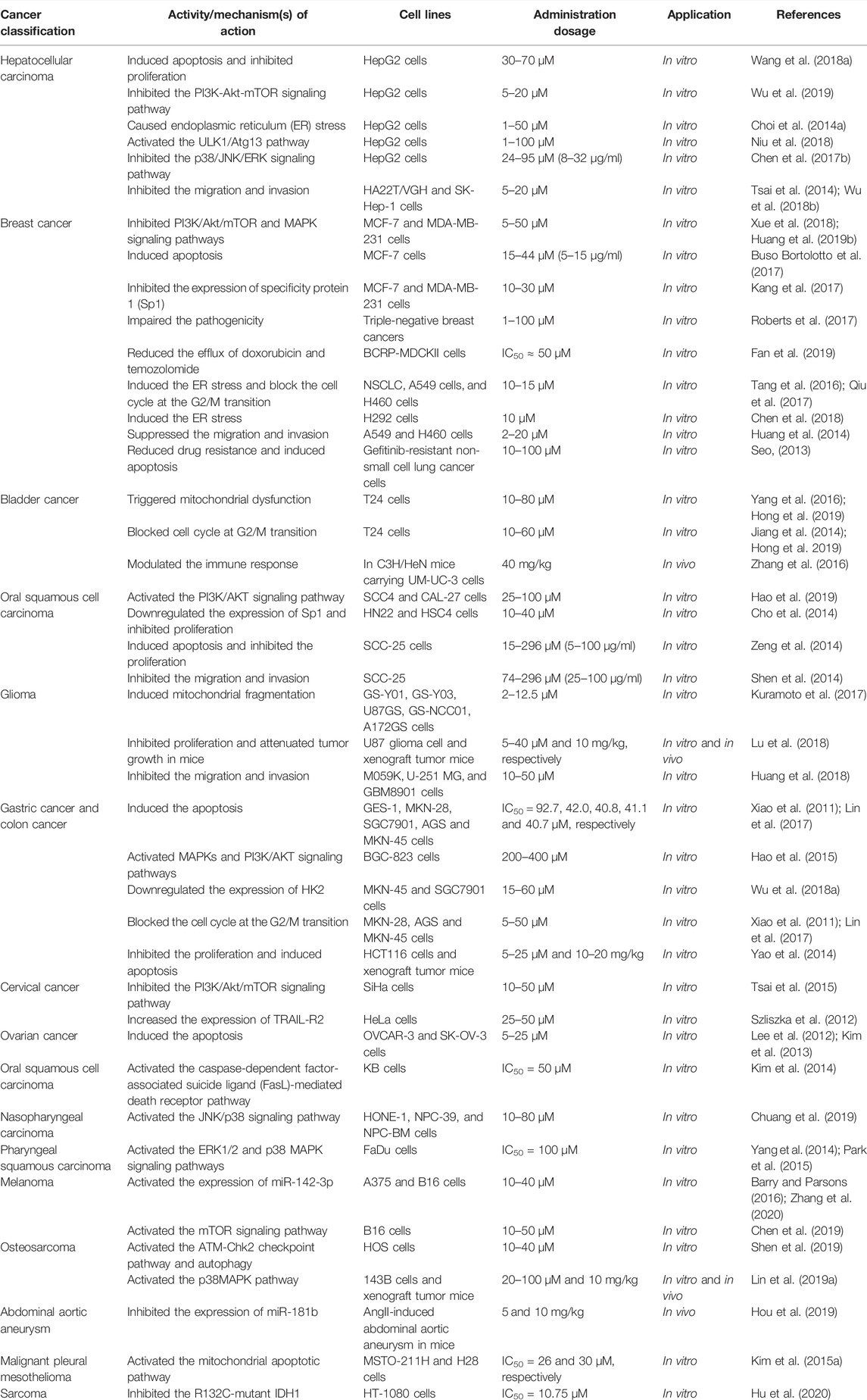

With the literature in hand, we found that LA exhibited significant therapeutic properties in various carcinoma cells via various mechanisms in vivo and in vitro throughout the cancer progression. These properties include direct anticancer effects, such as inducing apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation, invasion, and migration. LA even displays other positive influences while maintaining therapeutic functions for cancers, including reducing drug resistance, impairing pathogenicity, modulating immune responses, and attenuating emesis (Table 1). Above all, LA as an adjunct to existing anticancer drugs may have broad applications. Hence, clinical anticancer research and in-depth investigation of the mechanisms of LA might be an important research direction.

Anti-Inflammation Activities of LA

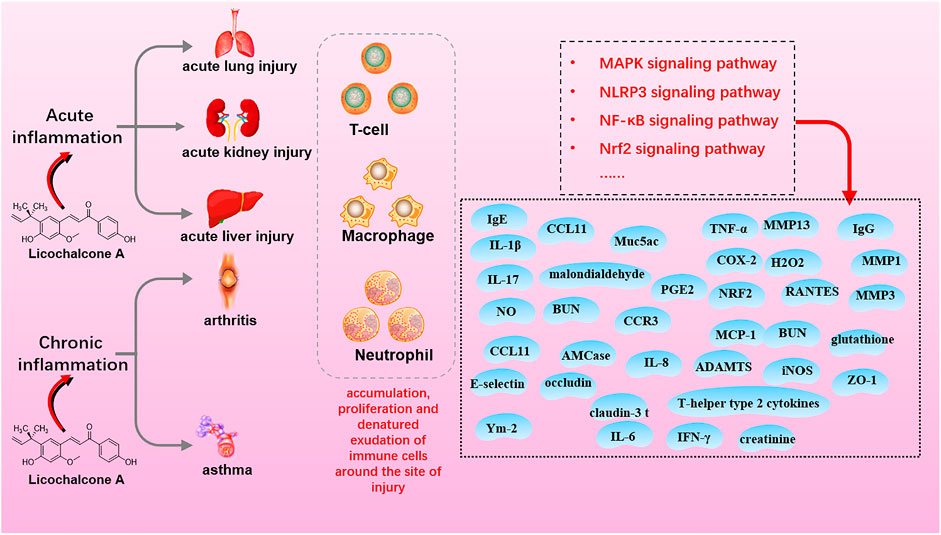

Inflammation is an immune response to biological, physical, or chemical injury and foreign bodies or necrotic tissue. Inflammation is classified as acute or chronic based on the duration and intensity of inflammatory stimuli and mitigation in situ. LA demonstrates anti-inflammatory activity via interaction with MAPK, NF-κB, NLRP3, and Nrf2 signaling in the acute lung, kidney, and liver injury (acute inflammation) and arthritis and asthma (chronic inflammation) (Figure 4; Table 2).

Effects of LA on Acute Inflammation

Acute inflammation is a protective response characterized by the rapid accumulation of immune cells around an injury site. The response features short duration, local edema, and leukocyte emigration. LA exerts anti-inflammatory effects in a dose-dependent manner. LA, 20–80 mg/kg, inhibited NF-κB signaling during treatment of acute inflammation in various mouse models, such as LPS-induced acute lung injury (Chu et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2019), LPS-induced acute kidney injury (Hu and Liu, 2016), and DSS-induced colitis (Liu et al., 2018). In detail, NF-κB and p38/ERK MAPK signaling pathways were inhibited in LPS-induced acute lung injury, and LA decreased the number of inflammatory cells, lung wet-to-dry weight ratio, protein leakage, and myeloperoxidase activity (Chu et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2019). LA also reduced the production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, and serum BUN and creatinine levels via inhibition of LPS-induced NF-κB activation in LPS-induced acute kidney injury (Hu and Liu, 2016). In addition, LA effectively alleviated DSS-induced colitis by downregulating the expression of pro-inflammatory factors and oxidative stress via inhibiting NF-κB and activating Nrf2 signaling (Liu et al., 2018). Additionally, LA (30 mg/kg) improved clinical symptoms of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide-induced mouse encephalomyelitis by inhibiting H2O2, NO, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-17 production and modulating the immune response of Th1 and Th17 cells (Almeida Fontes L. B. et al., 2014; Almeida Fontes LB. et al., 2014). At a higher dose (100 mg/kg), LA attenuated LPS-induced mouse acute liver injury via reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, by inhibiting TLR4-MAPK-NF-κB and Txnip-NLRP3 signaling (Lv et al., 2019).

Furthermore, in vitro studies suggested mechanisms of LA in acute inflammation treatment consistent with in vivo data. LA inhibited the production of NO, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and PGE2 in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages at doses of 5–20 μM (Chu et al., 2012; Fu et al., 2013). In addition, LA blocked MAPK, and AKT/NF-κB signaling increased protein levels of ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-3, and exerted an anti-inflammatory effect on LPS-induced mouse mammary epithelial cells at doses of 4–9 μM (Guo et al., 2019). As for TNF-α-induced A549 cells (acute lung injury model), LA suppressed the inflammatory response in TNF-α-induced A549 cells (acute lung injury model) by inhibiting NF-κB signaling and PGE2 secretion at doses of 1.5–30 μM (Sulzberger et al., 2016).

Effects of LA on Chronic Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is a slow, long-term process that varies by etiology and repair capacity. Acute inflammation tends to develop into chronic inflammation due to the persistence of inflammation or poor repair of damage. The ubiquity of chronic inflammation-mediated diseases has attracted many researchers. Investigation of anti-inflammatory properties of LA on chronic inflammation has used arthritis and asthma models that represent typical chronic inflammation conditions. LA showed anti-inflammation activity on IL-1β-stimulated mouse chondrocytes in arthritis models by a complex mechanism involving inhibition of phosphorylation of NF-κBp65 and IκBαn, decreasing the production of PGE2 and NO, and downregulating the expression of iNOS, COX-2, ADAMTS, MMP1, MMP3, and MMP13 by blocking NF-κB and wnt/β-catenin signaling (Chen WP. et al., 2017).

Conversely, LA (25–50 mg/kg) inhibited secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and upregulation of antioxidant enzyme expression via the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway to reduce inflammation in collagen antibody-induced arthritic mice in vivo (Su et al., 2018). What is more, LA altered the morphology, ultrastructure, and stiffness of synovial fibroblast membranes in mouse rheumatoid arthritis. The agent also decreased paw swelling in antigen-induced mice by inhibiting IκBα phosphorylation and degradation and p65 nuclear translocation and phosphorylation (Yang et al., 2018).

As for asthma models, LA improved symptoms in animal asthma models and slowed the progression of airway inflammation. The study evidenced that LA suppressed the expression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and other pro-inflammatory mediators, such as MCP-1, RANTES, and IL-8, in polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid-induced BEAS-2B cells and primary bronchial epithelial cells with doses of 10–30 μM (Kim SH. et al., 2015) through inhibition of KK/NF-κB/TSLP signaling. LA also inhibited VEGF-induced mouse airway smooth muscle cell proliferation at the above doses via blocking VEGFR2 and ERK1/2 signaling and downregulating the expression of caveolin-1 (Kim et al., 2017). Additionally, LA (5–50 mg/kg) reversed the progression of airway inflammation in OVA-induced allergic asthmatic mice by inhibiting the expression of Ym-2, AMCase, Muc5ac, E-selectin, CCL11, CCR3, and T-helper type 2 cytokines, simultaneously with dynamic regulation of levels of malondialdehyde, IgE, IgG, and glutathione (Chu et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2019a). LA inhibited ORAI1, Kv1.3, and KCa3.1 channels and significantly inhibited the production and secretion of IL-2 in T cells induced by CD3 and CD28 antibodies in vivo. Overall, LA may offer an effective therapeutic strategy for inflammation-related immune diseases (Phan et al., 2021).

Other Pharmacological Effects and Pharmacokinetic Details

LA also exhibits additional pharmacological properties. Activities include antibacterial (Hao et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2015; Michelotto Cantelli et al., 2017), antioxidant (Su et al., 2018), bone protection (Kim et al., 2012; Ming et al., 2014; Shang et al., 2014), anti-parasitic (Yadav et al., 2012; Tadigoppula et al., 2013), neuroprotection (Lee SY. et al., 2018), skin protection (Angelova-Fischer et al., 2014; Angelova-Fischer et al., 2018), regulation of blood glucose and blood lipids (Quan et al., 2012; Quan et al., 2013; Lee HE. et al., 2018). Cellular processes are primarily associated with inflammatory responses, lipid metabolism, and oxidative stress. Signaling pathways involved include NF-κB and sirt-1/AMPK, and Nrf2 oxidative stress (Sulzberger et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018; Lv et al., 2019). In an in vivo pharmacokinetic study after oral administration of LA to SD rats (200 mg/kg), Cmax was 3.31 ± 0.30 μg/ml, AUC0-24 h was 21.83 ± 1.44 μg/ml, T1/2 was 7.21 ± 0.37 h, MRT was 10.26 ± 1.01 h (Zhu et al., 2021). Furthermore, Liu and others found a Cmax of 3.39 ± 0.22 μg/ml, AUC0-24 h of 19.37 ± 0.56 μg/ml, T1/2 value of 7.43 ± 0.51 h, MRT of 11.84 ± 0.67 h, and Tmax of 2 ± 0 h. Meanwhile, LA is rapidly distributed to all tissues, particularly in the liver, kidney, and spleen, within a short time (Choi JS. et al., 2014).

Summary and Perspectives

We found that LA exhibits various beneficial pharmacological properties. First, LA demonstrates promising anticancer activity on epithelial carcinoma and mesenchymal sarcoma cells through apoptosis and ER stress processes. These biological processes involve several signaling pathways, such as PI3K/Akt/mTOR, P53, NF-κB, P38, and caspase-3 apoptosis that in turn involve multiple targets, such as TNF-α, VEGF, Fas, PI3K, AKT, caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-4, caspase-9, and caspase-10. Moreover, LA displays a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities, such as anti-inflammation, antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-plasmodial, and positive blood glucose and lipids regulation. These activities are associated with cellular inflammatory responses, lipid metabolism, and oxidative stress. These processes are regulated by signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, sirt-1/AMPK, and Nrf2 oxidative stress.

Significant progress has been made over the last decade, but several challenges still hamper in-depth mechanism research and clinical trials. First, current studies of LA focus mainly on signaling pathways and proteins or biomolecules at the molecular level. DNA and RNA molecules also play essential roles in developing complex diseases (Michalak et al., 2019; Varshney et al., 2020). Hence, exploration of LA targeting disease-related DNA and RNA fragments could be a promising direction for research in the future. Second, during data collection, we found that LA could counter the intestinal toxicity caused by irinotecan (Song et al., 2021), and LA derivatives and artemisinin demonstrated a synergism that enhanced antimalarial effects (Sharma et al., 2014). Clinical research with drug or other bioactive compound combinations with LA could prove rewarding; this approach is consistent with LA’s role as a guiding medicinal herb in traditional Chinese formulas. Third, the development of computer science and AI technology accelerates the speed of drug discovery (Chan et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019), and well-established organic synthetic technology enables us to rapidly and precisely synthesize desirable molecules derived from bioactive natural compounds (Zhuang et al., 2017; Afanasyev et al., 2019). Suitable modification of LA structure for production of novel derivatives (Boström et al., 2018), or precise connection of LA with a linker and ligand of E3 (ubiquitin ligase) for assembly of proteolysis targeting chimeras (Chamberlain and Hamann, 2019; Burslem and Crews, 2020), could lead to the discovery of LA derivatives with excellent therapeutical properties (Thomford et al., 2018). We hope this review provides an updated and reliable insight into scientific research related to LA.

Author Contributions

M-TL, XL, XX, and H-ML contributed to the conception and design of this study. QH, LX, and H-MJ participated in data collection and performed the statistical analysis. M-TL, QH, LX, and XL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. R-ST, XX, and H-ML contributed to manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82104376); National Key R&D Program (2020YFC2005506); Key R&D Program of Sichuan Science and Technology Department (2022YFS0159 and 2019YFS0514); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M673295 and 2020T130273); The Fundamental Research Funds for Sichuan Provincial Scientific Research Institutes (A-2021N-Z-2); Xinglin Scholar Research Promotion Project of Chengdu University of TCM (YXRC2019004, ZRYY1922, and BSH2020018); and Open Research Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Southwestern Chinese Medicine Resources of Chengdu University of TCM (BSH2020018 and 2020BSH008).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afanasyev, O. I., Kuchuk, E., Usanov, D. L., and Chusov, D. (2019). Reductive Amination in the Synthesis of Pharmaceuticals. Chem. Rev. 119 (23), 11857–11911. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00383

Almeida Fontes, L. B., Dos Santos Dias, D., de Carvalho, L. S., Mesquita, H. L., da Silva Reis, L., Dias, A. T., et al. (2014b). Immunomodulatory Effects of Licochalcone A on Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 66 (6), 886–894. doi:10.1111/jphp.12212

Almeida Fontes, L. B., Aarestrup, B. J. V., Aarestrup, F. M., Da Silva Filho, A. A., and do Amaral Correa, J. O. (2014a). Effects of Licochalcone A on Immunomodulation in a Murine Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Planta Medica 80 (16), 1403. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1394634

Angelova-Fischer, I., Neufang, G., Jung, K., Fischer, T. W., and Zillikens, D. (2014). A Randomized, Investigator-Blinded Efficacy Assessment Study of Stand-Alone Emollient Use in Mild to Moderately Severe Atopic Dermatitis Flares. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol Venereol. 28 (Suppl. 3), 9–15. doi:10.1111/jdv.12479

Angelova-Fischer, I., Rippke, F., Richter, D., Filbry, A., Arrowitz, C., Weber, T., et al. (2018). Stand-alone Emollient Treatment Reduces Flares after Discontinuation of Topical Steroid Treatment in Atopic Dermatitis: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Vehicle-Controlled, Left-Right Comparison Study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 98 (5), 517–523. doi:10.2340/00015555-2882

Bai, H., Zhou, M., Zhou, H., Han, Q., Xu, H., Xu, P., et al. (2021). Licochalcone A Suppresses Sp1 Expression with Potential Anti-myeloma Activity. Cancer Commun. (Lond) 41 (11), 1239–1242. doi:10.1002/cac2.12223

Barry, P., and Parsons, K. G. (2016). Effects of Licochalcone A on M624 Human Melanoma Cell Proliferation. Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc. 251.

Boström, J., Brown, D. G., Young, R. J., and Keserü, G. M. (2018). Expanding the Medicinal Chemistry Synthetic Toolbox. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17 (10), 709–727. doi:10.1038/nrd.2018.116

Burslem, G. M., and Crews, C. M. (2020). Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras as Therapeutics and Tools for Biological Discovery. Cell 181 (1), 102–114. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.031

Buso Bortolotto, L. F., Barbosa, F. R., Silva, G., Bitencourt, T. A., Beleboni, R. O., Baek, S. J., et al. (2017). Cytotoxicity of Trans-chalcone and Licochalcone A against Breast Cancer Cells Is Due to Apoptosis Induction and Cell Cycle Arrest. Biomed. Pharmacother. 85, 425–433. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.047

Chamberlain, P. P., and Hamann, L. G. (2019). Development of Targeted Protein Degradation Therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15 (10), 937–944. doi:10.1038/s41589-019-0362-y

Chan, H. C. S., Shan, H., Dahoun, T., Vogel, H., and Yuan, S. (2019). Advancing Drug Discovery via Artificial Intelligence. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 40 (8), 592–604. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2019.06.004

Chen, G., Ma, Y., Jiang, Z., Feng, Y., Han, Y., Tang, Y., et al. (2018). Lico A Causes ER Stress and Apoptosis via Up-Regulating miR-144-3p in Human Lung Cancer Cell Line H292. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 837. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00837

Chen, R., Lin, K., Chen, M., and Lu, W. (2019). Licochalcone A Inhibits Melanoma Cell Growth and Migration via Arresting Cell Cycle and Suppressing Akt Phosphorylation. Febs Open Bio 9, 328.

Chen, W. P., Hu, Z. N., Jin, L. B., and Wu, L. D. (2017a). Licochalcone A Inhibits MMPs and ADAMTSs via the NF-Κb and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathways in Rat Chondrocytes. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 43 (3), 937–944. doi:10.1159/000481645

Chen, X., Liu, Z., Meng, R., Shi, C., and Guo, N. (2017b). Antioxidative and Anticancer Properties of Licochalcone A from Licorice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 198, 331–337. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2017.01.028

Cheng, D., and Bedford, M. T. (2011). Xenoestrogens Regulate the Activity of Arginine Methyltransferases. Chembiochem 12 (2), 323–329. doi:10.1002/cbic.201000522

Cho, J. J., Chae, J. I., Yoon, G., Kim, K. H., Cho, J. H., Cho, S. S., et al. (2014). Licochalcone A, a Natural Chalconoid Isolated from Glycyrrhiza Inflata Root, Induces Apoptosis via Sp1 and Sp1 Regulatory Proteins in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 45 (2), 667–674. doi:10.3892/ijo.2014.2461

Choi, A. Y., Choi, J. H., Hwang, K. Y., Jeong, Y. J., Choe, W., Yoon, K. S., et al. (2014a). Licochalcone A Induces Apoptosis through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress via a Phospholipase Cγ1-, Ca(2+)-, and Reactive Oxygen Species-dependent Pathway in HepG2 Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Apoptosis 19 (4), 682–697. doi:10.1007/s10495-013-0955-y

Choi, J. S., Choi, J. S., and Choi, D. H. (2014b). Effects of Licochalcone A on the Bioavailability and Pharmacokinetics of Nifedipine in Rats: Possible Role of Intestinal CYP3A4 and P-Gp Inhibition by Licochalcone A. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 35 (7), 382–390. doi:10.1002/bdd.1905

Chu, X., Ci, X., Wei, M., Yang, X., Cao, Q., Guan, M., et al. (2012). Licochalcone A Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Response In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60 (15), 3947–3954. doi:10.1021/jf2051587

Chu, X., Jiang, L., Wei, M., Yang, X., Guan, M., Xie, X., et al. (2013). Attenuation of Allergic Airway Inflammation in a Murine Model of Asthma by Licochalcone A. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 35 (6), 653–661. doi:10.3109/08923973.2013.834929

Chuang, C. Y., Tang, C. M., Ho, H. Y., Hsin, C. H., Weng, C. J., Yang, S. F., et al. (2019). Licochalcone A Induces Apoptotic Cell Death via JNK/p38 Activation in Human Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells. Environ. Toxicol. 34 (7), 853–860. doi:10.1002/tox.22753

Fan, X., Bai, J., Zhao, S., Hu, M., Sun, Y., Wang, B., et al. (2019). Evaluation of Inhibitory Effects of Flavonoids on Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP): From Library Screening to Biological Evaluation to Structure-Activity Relationship. Toxicol Vitro 61, 104642. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2019.104642

Fu, Y., Chen, J., Li, Y. J., Zheng, Y. F., and Li, P. (2013). Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Activities of Six Flavonoids Separated from Licorice. Food Chem. 141 (2), 1063–1071. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.03.089

Guo, W., Liu, B., Yin, Y., Kan, X., Gong, Q., Li, Y., et al. (2019). Licochalcone A Protects the Blood-Milk Barrier Integrity and Relieves the Inflammatory Response in LPS-Induced Mastitis. Front. Immunol. 10, 287. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00287

Hajirahimkhan, A., Simmler, C., Dong, H., Lantvit, D. D., Li, G., Chen, S. N., et al. (2015). Induction of NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) by Glycyrrhiza Species Used for Women's Health: Differential Effects of the Michael Acceptors Isoliquiritigenin and Licochalcone A. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 28 (11), 2130–2141. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00310

Hao, H., Hui, W., Liu, P., Lv, Q., Zeng, X., Jiang, H., et al. (2013). Effect of Licochalcone A on Growth and Properties of Streptococcus Suis. Plos One 8 (7), e67728. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067728

Hao, W., Yuan, X., Yu, L., Gao, C., Sun, X., Wang, D., et al. (2015). Licochalcone A-Induced Human Gastric Cancer BGC-823 Cells Apoptosis by Regulating ROS-Mediated MAPKs and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways. Sci. Rep. 5, 10336. doi:10.1038/srep10336

Hao, Y., Zhang, C., Sun, Y., and Xu, H. (2019). Licochalcone A Inhibits Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion through Regulating the PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 12, 4427–4435. doi:10.2147/ott.S201728

Herbrechter, R., Ziemba, P. M., Hoffmann, K. M., Hatt, H., Werner, M., and Gisselmann, G. (2015). Identification of Glycyrrhiza as the Rikkunshito Constituent with the Highest Antagonistic Potential on Heterologously Expressed 5-HT3A Receptors Due to the Action of Flavonoids. Front. Pharmacol. 6, 130. doi:10.3389/fphar.2015.00130

Hong, S. H., Cha, H. J., Hwang-Bo, H., Kim, M. Y., Kim, S. Y., Ji, S. Y., et al. (2019). Anti-Proliferative and Pro-apoptotic Effects of Licochalcone A through ROS-Mediated Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Human Bladder Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (15). doi:10.3390/ijms20153820

Hou, X., Yang, S., and Zheng, Y. (2019). Licochalcone A Attenuates Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Induced by Angiotensin II via Regulating the miR-181b/SIRT1/HO-1 Signaling. J. Cell Physiol. 234 (5), 7560–7568. doi:10.1002/jcp.27517

Hu, C., Zuo, Y., Liu, J., Xu, H., Liao, W., Dang, Y., et al. (2020). Licochalcone A Suppresses the Proliferation of Sarcoma HT-1080 Cells, as a Selective R132C Mutant IDH1 Inhibitor. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 30 (2), 126825. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126825

Hu, J., and Liu, J. (2016). Licochalcone A Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Kidney Injury by Inhibiting NF-Κb Activation. Inflammation 39 (2), 569–574. doi:10.1007/s10753-015-0281-3

Huang, C. F., Yang, S. F., Chiou, H. L., Hsu, W. H., Hsu, J. C., Liu, C. J., et al. (2018). Licochalcone A Inhibits the Invasive Potential of Human Glioma Cells by Targeting the MEK/ERK and ADAM9 Signaling Pathways. Food Funct. 9 (12), 6196–6204. doi:10.1039/c8fo01643g

Huang, H. C., Tsai, L. L., Tsai, J. P., Hsieh, S. C., Yang, S. F., Hsueh, J. T., et al. (2014). Licochalcone A Inhibits the Migration and Invasion of Human Lung Cancer Cells via Inactivation of the Akt Signaling Pathway with Downregulation of MMP-1/-3 Expression. Tumour Biol. 35 (12), 12139–12149. doi:10.1007/s13277-014-2519-3

Huang, W. C., Liu, C. Y., Shen, S. C., Chen, L. C., Yeh, K. W., Liu, S. H., et al. (2019a). Protective Effects of Licochalcone A Improve Airway Hyper-Responsiveness and Oxidative Stress in a Mouse Model of Asthma. Cells 8 (6). doi:10.3390/cells8060617

Huang, W. C., Su, H. H., Fang, L. W., Wu, S. J., and Liou, C. J. (2019b). Licochalcone A Inhibits Cellular Motility by Suppressing E-Cadherin and MAPK Signaling in Breast Cancer. Cells 8 (3). doi:10.3390/cells8030218

Jia, T., Qiao, J., Guan, D., and Chen, T. (2017). Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Licochalcone A on IL-1β-Stimulated Human Osteoarthritis Chondrocytes. Inflammation 40 (6), 1894–1902. doi:10.1007/s10753-017-0630-5

Jiang, J., Yuan, X., Zhao, H., Yan, X., Sun, X., and Zheng, Q. (2014). Licochalcone A Inhibiting Proliferation of Bladder Cancer T24 Cells by Inducing Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Biomed. Mater Eng. 24 (1), 1019–1025. doi:10.3233/bme-130899

Jiang, M., Zhao, S., Yang, S., Lin, X., He, X., Wei, X., et al. (2020). An "essential Herbal Medicine"-Licorice: A Review of Phytochemicals and its Effects in Combination Preparations. J. Ethnopharmacol. 249, 112439. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.112439

Kang, T. H., Seo, J. H., Oh, H., Yoon, G., Chae, J. I., and Shim, J. H. (2017). Licochalcone A Suppresses Specificity Protein 1 as a Novel Target in Human Breast Cancer Cells. J. Cell Biochem. 118 (12), 4652–4663. doi:10.1002/jcb.26131

Kennedy, L. B., and Salama, A. K. S. (2020). A Review of Cancer Immunotherapy Toxicity. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70 (2), 86–104. doi:10.3322/caac.21596

Kim, J. S., Park, M. R., Lee, S. Y., Kim, D. K., Moon, S. M., Kim, C. S., et al. (2014). Licochalcone A Induces Apoptosis in KB Human Oral Cancer Cells via a Caspase-dependent FasL Signaling Pathway. Oncol. Rep. 31 (2), 755–762. doi:10.3892/or.2013.2929

Kim, K. H., Yoon, G., Cho, J. J., Cho, J. H., Cho, Y. S., Chae, J. I., et al. (2015a). Licochalcone A Induces Apoptosis in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma through Downregulation of Sp1 and Subsequent Activation of Mitochondria-Related Apoptotic Pathway. Int. J. Oncol. 46 (3), 1385–1392. doi:10.3892/ijo.2015.2839

Kim, S. H., Pei, Q. M., Jiang, P., Yang, M., Qian, X. J., and Liu, J. B. (2017). Role of Licochalcone A in VEGF-Induced Proliferation of Human Airway Smooth Muscle Cells: Implications for Asthma. Growth factors. 35 (1), 39–47. doi:10.1080/08977194.2017.1338694

Kim, S. H., Yang, M., Xu, J. G., Yu, X., and Qian, X. J. (2015b). Role of Licochalcone A on Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin Expression: Implications for Asthma. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 240 (1), 26–33. doi:10.1177/1535370214545020

Kim, S. N., Bae, S. J., Kwak, H. B., Min, Y. K., Jung, S. H., Kim, C. H., et al. (2012). In Vitro and In Vivo Osteogenic Activity of Licochalcone A. Amino Acids 42 (4), 1455–1465. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0901-7

Kim, Y. J., Jung, E. B., Myung, S. C., Kim, W., and Lee, C. S. (2013). Licochalcone A Enhances Geldanamycin-Induced Apoptosis through Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Caspase Activation. Pharmacology 92 (1-2), 49–59. doi:10.1159/000351846

Kuramoto, K., Suzuki, S., Sakaki, H., Takeda, H., Sanomachi, T., Seino, S., et al. (2017). Licochalcone A Specifically Induces Cell Death in Glioma Stem Cells via Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Febs Open Bio 7 (6), 835–844. doi:10.1002/2211-5463.12226

Lee, B. H., Pyo, M. K., Lee, J. H., Choi, S. H., Shin, T. J., Lee, S. M., et al. (2008). Differential Regulations of Quercetin and its Glycosides on Ligand-Gated Ion Channels. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31 (4), 611–617. doi:10.1248/bpb.31.611

Lee, C. S., Kwak, S. W., Kim, Y. J., Lee, S. A., Park, E. S., Myung, S. C., et al. (2012). Guanylate Cyclase Activator YC-1 Potentiates Apoptotic Effect of Licochalcone A on Human Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma Cells via Activation of Death Receptor and Mitochondrial Pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 683 (1-3), 54–62. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.03.024

Lee, H. E., Yang, G., Han, S. H., Lee, J. H., An, T. J., Jang, J. K., et al. (2018a). Anti-obesity Potential of Glycyrrhiza Uralensis and Licochalcone A through Induction of Adipocyte Browning. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 503 (3), 2117–2123. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.07.168

Lee, S. Y., Chiu, Y. J., Yang, S. M., Chen, C. M., Huang, C. C., Lee-Chen, G. J., et al. (2018b). Novel Synthetic Chalcone-Coumarin Hybrid for Aβ Aggregation Reduction, Antioxidation, and Neuroprotection. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 24 (12), 1286–1298. doi:10.1111/cns.13058

Li, N., Zhang, P., Wu, H., Wang, J., Liu, F., and Wang, W. (2015). Natural Flavonoids Function as Chemopreventive Agents from Gancao (Glycyrrhiza Inflata Batal). J. Funct. Foods 19, 563–574. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2015.09.045

Lin, R. C., Yang, S. F., Chiou, H. L., Hsieh, S. C., Wen, S. H., Lu, K. H., et al. (2019a). Licochalcone A-Induced Apoptosis through the Activation of p38MAPK Pathway Mediated Mitochondrial Pathways of Apoptosis in Human Osteosarcoma Cells In Vitro and In Vivo. Cells 8 (11). doi:10.3390/cells8111441

Lin, X., Tian, L., Wang, L., Li, W., Xu, Q., and Xiao, X. (2017). Antitumor Effects and the Underlying Mechanism of Licochalcone A Combined with 5-fluorouracil in Gastric Cancer Cells. Oncol. Lett. 13 (3), 1695–1701. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.5614

Lin, Y. J., Liang, W. M., Chen, C. J., Tsang, H., Chiou, J. S., Liu, X., et al. (2019b). Network Analysis and Mechanisms of Action of Chinese Herb-Related Natural Compounds in Lung Cancer Cells. Phytomedicine 58, 152893. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152893

Liu, D., Huo, X., Gao, L., Zhang, J., Ni, H., and Cao, L. (2018). NF-Κb and Nrf2 Pathways Contribute to the Protective Effect of Licochalcone A on Dextran Sulphate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 102, 922–929. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.130

Liu, X., Xing, Y., Li, M., Zhang, Z., Wang, J., Ri, M., et al. (2021). Licochalcone A Inhibits Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis of Colon Cancer Cell by Targeting Programmed Cell Death-Ligand 1 via the NF-Κb and Ras/Raf/MEK Pathways. J. Ethnopharmacol. 273, 113989. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2021.113989

Liu, Y., Hong, Z., Qian, J., Wang, Y., and Wang, S. (2019). Protective Effect of Jie-Geng-Tang against Staphylococcus aureus Induced Acute Lung Injury in Mice and Discovery of its Effective Constituents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 243, 112076. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.112076

Lu, W. J., Wu, G. J., Chen, R. J., Chang, C. C., Lien, L. M., Chiu, C. C., et al. (2018). Licochalcone A Attenuates Glioma Cell Growth In Vitro and In Vivo through Cell Cycle Arrest. Food Funct. 9 (8), 4500–4507. doi:10.1039/c8fo00728d

Luo, W., Sun, R., Chen, X., Li, J., Jiang, J., He, Y., et al. (2020). ERK Activation-Mediated Autophagy Induction Resists Licochalcone A-Induced Anticancer Activities in Lung Cancer Cells In Vitro. Onco Targets Ther. 13, 13437–13450. doi:10.2147/ott.S278268

Lv, H., Yang, H., Wang, Z., Feng, H., Deng, X., Cheng, G., et al. (2019). Nrf2 Signaling and Autophagy Are Complementary in Protecting Lipopolysaccharide/d-Galactosamine-Induced Acute Liver Injury by Licochalcone A. Cell Death Dis. 10, 313. doi:10.1038/s41419-019-1543-z

Michalak, E. M., Burr, M. L., Bannister, A. J., and Dawson, M. A. (2019). The Roles of DNA, RNA and Histone Methylation in Ageing and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20 (10), 573–589. doi:10.1038/s41580-019-0143-1

Michelotto Cantelli, B. A., Bitencourt, T. A., Komoto, T. T., Beleboni, R. O., Marins, M., and Fachin, A. L. (2017). Caffeic Acid and Licochalcone A Interfere with the Glyoxylate Cycle of Trichophyton Rubrum. Biomed. Pharmacother. 96, 1389–1394. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.11.051

Ming, L., Jin, F., Huang, P., Luo, H., Liu, W., Zhang, L., et al. (2014). Licochalcone A Up-Regulates of FasL in Mesenchymal Stem Cells to Strengthen Bone Formation and Increase Bone Mass. Sci. Rep. 4, 7209. doi:10.1038/srep07209

Niu, Q., Zhao, W., Wang, J., Li, C., Yan, T., Lv, W., et al. (2018). LicA Induces Autophagy through ULK1/Atg13 and ROS Pathway in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 41 (5), 2601–2608. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2018.3499

Park, M. R., Kim, S. G., Cho, I. A., Oh, D., Kang, K. R., Lee, S. Y., et al. (2015). Licochalcone-A Induces Intrinsic and Extrinsic Apoptosis via ERK1/2 and P38 Phosphorylation-Mediated TRAIL Expression in Head and Neck Squamous Carcinoma FaDu Cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 77, 34–43. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2014.12.013

Phan, H. T. L., Kim, H. J., Jo, S., Kim, W. K., Namkung, W., and Nam, J. H. (2021). Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Licochalcone A via Regulation of ORAI1 and K+ Channels in T-Lymphocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (19). doi:10.3390/ijms221910847

Qiu, C., Zhang, T., Zhang, W., Zhou, L., Yu, B., Wang, W., et al. (2017). Licochalcone A Inhibits the Proliferation of Human Lung Cancer Cell Lines A549 and H460 by Inducing G2/M Cell Cycle Arrest and ER Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (8). doi:10.3390/ijms18081761

Quan, H. Y., Baek, N. I., and Chung, S. H. (2012). Licochalcone A Prevents Adipocyte Differentiation and Lipogenesis via Suppression of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ and Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein Pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60 (20), 5112–5120. doi:10.1021/jf2050763

Quan, H. Y., Kim, S. J., Kim, D. Y., Jo, H. K., Kim, G. W., and Chung, S. H. (2013). Licochalcone A Regulates Hepatic Lipid Metabolism through Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Fitoterapia 86, 208–216. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2013.03.005

Roberts, L. S., Yan, P., Bateman, L. A., and Nomura, D. K. (2017). Mapping Novel Metabolic Nodes Targeted by Anti-cancer Drugs that Impair Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Pathogenicity. ACS Chem. Biol. 12 (4), 1133–1140. doi:10.1021/acschembio.6b01159

Seo, Y. H. (2013). Discovery of Licochalcone A as a Natural Product Inhibitor of Hsp90 and its Effect on Gefitinib Resistance in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 34 (6), 1917–1920. doi:10.5012/bkcs.2013.34.6.1917

Shang, F., Ming, L., Zhou, Z., Yu, Y., Sun, J., Ding, Y., et al. (2014). The Effect of Licochalcone A on Cell-Aggregates ECM Secretion and Osteogenic Differentiation during Bone Formation in Metaphyseal Defects in Ovariectomized Rats. Biomaterials 35 (9), 2789–2797. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.061

Sharma, N., Mohanakrishnan, D., Sharma, U. K., Kumar, R., RichaSinha, A. K., Sinha, A. K., et al. (2014). Design, Economical Synthesis and Antiplasmodial Evaluation of Vanillin Derived Allylated Chalcones and Their Marked Synergism with Artemisinin against Chloroquine Resistant Strains of Plasmodium Falciparum. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 79, 350–368. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.079

Shen, F., Tang, X., Wang, Y., Yang, Z., Shi, X., Wang, C., et al. (2015). Phenotype and Expression Profile Analysis of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms and Planktonic Cells in Response to Licochalcone A. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99 (1), 359–373. doi:10.1007/s00253-014-6076-x

Shen, H., Zeng, G., Tang, G., Cai, X., Bi, L., Huang, C., et al. (2014). Antimetastatic Effects of Licochalcone A on Oral Cancer via Regulating Metastasis-Associated Proteases. Tumour Biol. 35 (8), 7467–7474. doi:10.1007/s13277-014-1985-y

Shen, T. S., Hsu, Y. K., Huang, Y. F., Chen, H. Y., Hsieh, C. P., and Chen, C. L. (2019). Licochalcone A Suppresses the Proliferation of Osteosarcoma Cells through Autophagy and ATM-Chk2 Activation. Molecules 24 (13). doi:10.3390/molecules24132435

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E., and Jemal, A. (2021). Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 71 (1), 7–33. doi:10.3322/caac.21654

Simmler, C., Lankin, D. C., Nikolić, D., van Breemen, R. B., and Pauli, G. F. (2017). Isolation and Structural Characterization of Dihydrobenzofuran Congeners of Licochalcone A. Fitoterapia 121, 6–15. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2017.06.017

Song, Y.-Q., Guan, X.-Q., Weng, Z.-M., Liu, J.-L., Chen, J., Wang, L., et al. (2021). Discovery of hCES2A Inhibitors from Glycyrrhiza Inflata via Combination of Docking-Based Virtual Screening and Fluorescence-Based Inhibition Assays. Food Funct. 12 (1), 162–176. doi:10.1039/d0fo02140g

Su, X., Li, T., Liu, Z., Huang, Q., Liao, K., Ren, R., et al. (2018). Licochalcone A Activates Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling to Suppress Arthritis via Phosphorylation of P62 at Serine 349. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 115, 471–483. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.12.004

Sulzberger, M., Worthmann, A. C., Holtzmann, U., Buck, B., Jung, K. A., Schoelermann, A. M., et al. (2016). Effective Treatment for Sensitive Skin: 4-T-Butylcyclohexanol and Licochalcone A. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol Venereol. 30 (Suppl. 1), 9–17. doi:10.1111/jdv.13529

Szliszka, E., Jaworska, D., Ksek, M., Czuba, Z. P., and Król, W. (2012). Targeting Death Receptor TRAIL-R2 by Chalcones for TRAIL-Induced Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13 (11), 15343–15359. doi:10.3390/ijms131115343

Tadigoppula, N., Korthikunta, V., Gupta, S., Kancharla, P., Khaliq, T., Soni, A., et al. (2013). Synthesis and Insight into the Structure-Activity Relationships of Chalcones as Antimalarial Agents. J. Med. Chem. 56 (1), 31–45. doi:10.1021/jm300588j

Tang, Z. H., Chen, X., Wang, Z. Y., Chai, K., Wang, Y. F., Xu, X. H., et al. (2016). Induction of C/EBP Homologous Protein-Mediated Apoptosis and Autophagy by Licochalcone A in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 26241. doi:10.1038/srep26241

Thomford, N. E., Senthebane, D. A., Rowe, A., Munro, D., Seele, P., Maroyi, A., et al. (2018). Natural Products for Drug Discovery in the 21st Century: Innovations for Novel Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (6). doi:10.3390/ijms19061578

Tsai, J. P., Hsiao, P. C., Yang, S. F., Hsieh, S. C., Bau, D. T., Ling, C. L., et al. (2014). Licochalcone A Suppresses Migration and Invasion of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells through Downregulation of MKK4/JNK via NF-Κb Mediated Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Expression. Plos One 9 (1), e86537. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086537

Tsai, J. P., Lee, C. H., Ying, T. H., Lin, C. L., Lin, C. L., Hsueh, J. T., et al. (2015). Licochalcone A Induces Autophagy through PI3K/Akt/mTOR Inactivation and Autophagy Suppression Enhances Licochalcone A-Induced Apoptosis of Human Cervical Cancer Cells. Oncotarget 6 (30), 28851–28866. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.4767

Varshney, D., Spiegel, J., Zyner, K., Tannahill, D., and Balasubramanian, S. (2020). The Regulation and Functions of DNA and RNA G-Quadruplexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21 (8), 459–474. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-0236-x

Wang, C., Chen, L., Xu, C., Shi, J., Chen, S., Tan, M., et al. (2020). A Comprehensive Review for Phytochemical, Pharmacological, and Biosynthesis Studies on Glycyrrhiza Spp. Am. J. Chin. Med. 48 (1), 17–45. doi:10.1142/s0192415x20500020

Wang, J., Zhang, Y. S., Thakur, K., Hussain, S. S., Zhang, J. G., Xiao, G. R., et al. (2018a). Licochalcone A from Licorice Root, an Inhibitor of Human Hepatoma Cell Growth via Induction of Cell Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest. Food Chem. Toxicol. 120, 407–417. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2018.07.044

Wang, J., Wei, B., Thakur, K., Wang, C.-Y., Li, K.-X., and Wei, Z.-J. (2021). Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Anti-cancerous Mechanism of Licochalcone A on Human Hepatoma Cell HepG2. Front. Nutr. 8. doi:10.3389/fnut.2021.807574

Wang, S., Dunlap, T. L., Huang, L., Liu, Y., Simmler, C., Lantvit, D. D., et al. (2018b). Evidence for Chemopreventive and Resilience Activity of Licorice: Glycyrrhiza Glabra and G. Inflata Extracts Modulate Estrogen Metabolism in ACI Rats. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 11 (12), 819–830. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.Capr-18-0178

Wu, J., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Sun, Q., Chen, M., Liu, S., et al. (2018a). Licochalcone A Suppresses Hexokinase 2-mediated Tumor Glycolysis in Gastric Cancer via Downregulation of the Akt Signaling Pathway. Oncol. Rep. 39 (3), 1181–1190. doi:10.3892/or.2017.6155

Wu, M. H., Chiu, Y. F., Wu, W. J., Wu, P. L., Lin, C. Y., Lin, C. L., et al. (2018b). Synergistic Antimetastatic Effect of Cotreatment with Licochalcone A and Sorafenib on Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells through the Inactivation of MKK4/JNK and uPA Expression. Environ. Toxicol. 33 (12), 1237–1244. doi:10.1002/tox.22630

Wu, R., Li, X.-Y., Wang, W.-H., Cai, F.-F., Chen, X.-L., Yang, M.-D., et al. (2019). Network Pharmacology-Based Study on the Mechanism of Bushen-Jianpi Decoction in Liver Cancer Treatment. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2019, 1–13. doi:10.1155/2019/3242989

Xiao, X. Y., Hao, M., Yang, X. Y., Ba, Q., Li, M., Ni, S. J., et al. (2011). Licochalcone A Inhibits Growth of Gastric Cancer Cells by Arresting Cell Cycle Progression and Inducing Apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 302 (1), 69–75. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2010.12.016

Xue, L., Zhang, W. J., Fan, Q. X., and Wang, L. X. (2018). Licochalcone A Inhibits PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway Activation and Promotes Autophagy in Breast Cancer Cells. Oncol. Lett. 15 (2), 1869–1873. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.7451

Yadav, N., Dixit, S. K., Bhattacharya, A., Mishra, L. C., Sharma, M., Awasthi, S. K., et al. (2012). Antimalarial Activity of Newly Synthesized Chalcone Derivatives In Vitro. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 80 (2), 340–347. doi:10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01383.x

Yang, F., Su, X., Pi, J., Liao, K., Zhou, H., Sun, Y., et al. (2018). Atomic Force Microscopy Technique Used for Assessment of the Anti-arthritic Effect of Licochalcone A via Suppressing NF-Κb Activation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 103, 1592–1601. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.142

Yang, P., Tuo, L., Wu, Q., and Cao, X. (2014). Licochalcone-A Sensitizes Human Esophageal Carcinoma Cells to TRAIL-Mediated Apoptosis by Proteasomal Degradation of XIAP. Hepatogastroenterology 61 (133), 1229–1234. doi:10.5754/hge14408

Yang, X., Jiang, J., Yang, X., Han, J., and Zheng, Q. (2016). Licochalcone A Induces T24 Bladder Cancer Cell Apoptosis by Increasing Intracellular Calcium Levels. Mol. Med. Rep. 14 (1), 911–919. doi:10.3892/mmr.2016.5334

Yang, X., Wang, Y., Byrne, R., Schneider, G., and Yang, S. (2019). Concepts of Artificial Intelligence for Computer-Assisted Drug Discovery. Chem. Rev. 119 (18), 10520–10594. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00728

Yao, K., Chen, H., Lee, M. H., Li, H., Ma, W., Peng, C., et al. (2014). Licochalcone A, a Natural Inhibitor of C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase 1. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 7 (1), 139–149. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.Capr-13-0117

Yuan, L. W., Jiang, X. M., Xu, Y. L., Huang, M. Y., Chen, Y. C., Yu, W. B., et al. (2021). Licochalcone A Inhibits Interferon-Gamma-Induced Programmed Death-Ligand 1 in Lung Cancer Cells. Phytomedicine 80, 153394. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153394

Yuan, X., Li, D., Zhao, H., Jiang, J., Wang, P., Ma, X., et al. (20132013). Licochalcone A-Induced Human Bladder Cancer T24 Cells Apoptosis Triggered by Mitochondria Dysfunction and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 1–9. doi:10.1155/2013/474272

Zeng, G., Shen, H., Yang, Y., Cai, X., and Xun, W. (2014). Licochalcone A as a Potent Antitumor Agent Suppresses Growth of Human Oral Cancer SCC-25 Cells In Vitro via Caspase-3 Dependent Pathways. Tumour Biol. 35 (7), 6549–6555. doi:10.1007/s13277-014-1877-1

Zhang, Y., Gao, M., Chen, L., Zhou, L., Bian, S., and Lv, Y. (2020). Licochalcone A Restrains Microphthalmia-Associated Transcription Factor Expression and Growth by Activating Autophagy in Melanoma Cells via miR-142-3p/Rheb/mTOR Pathway. Phytother. Res. 34 (2), 349–358. doi:10.1002/ptr.6525

Zhang, Y.-Y., Huang, C.-T., Liu, S.-M., Wang, B., Guo, J., Bai, J.-Q., et al. (2016). Licochalcone A Exerts Antitumor Activity in Bladder Cancer Cell Lines and Mice Models. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 15 (6), 1151–1157. doi:10.4314/tjpr.v15i6.6

Zhu, Z., Liu, J., Yang, Y., Adu-Frimpong, M., Ji, H., Toreniyazov, E., et al. (2021). SMEDDS for Improved Oral Bioavailability and Anti-hyperuricemic Activity of Licochalcone A. J. Microencapsul. 38 (7-8), 459–471. doi:10.1080/02652048.2021.1963341

Keywords: flavonoid, licochalcone A, anticancer, pharmacological therapy, traditional Chinese medicine

Citation: Li M-T, Xie L, Jiang H-M, Huang Q, Tong R-S, Li X, Xie X and Liu H-M (2022) Role of Licochalcone A in Potential Pharmacological Therapy: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 13:878776. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.878776

Received: 18 February 2022; Accepted: 20 April 2022;

Published: 23 May 2022.

Edited by:

Eswar Shankar, The Ohio State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Abhilasha Shourie, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies (MRIIRS), IndiaKirti Kaul, The Ohio State University, United States

Robin Herbrechter, Witten/Herdecke University, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Li, Xie, Jiang, Huang, Tong, Li, Xie and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiang Li, bGl4aWFuZzJAY2R1dGNtLmVkdS5jbg==; Xin Xie, eGlleGluQGNkdXRjbS5lZHUuY24=; Hong-Mei Liu, bGl1aG9uZ21laUB1ZXN0Yy5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share the first authorship

Meng-Ting Li1†

Meng-Ting Li1† Long Xie

Long Xie Rong-Sheng Tong

Rong-Sheng Tong Xiang Li

Xiang Li Xin Xie

Xin Xie Hong-Mei Liu

Hong-Mei Liu