94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Pharmacol., 13 December 2022

Sec. Drug Metabolism and Transport

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1065130

This article is part of the Research TopicDrug-Drug Interactions in PharmacologyView all 14 articles

Zhiheng Yu1†

Zhiheng Yu1† Zihan Lei2,3†

Zihan Lei2,3† Xueting Yao4†

Xueting Yao4† Hengbang Wang5†

Hengbang Wang5† Miao Zhang3

Miao Zhang3 Zhe Hou3

Zhe Hou3 Yafen Li2,3

Yafen Li2,3 Yangyu Zhao6

Yangyu Zhao6 Haiyan Li7

Haiyan Li7 Dongyang Liu4*

Dongyang Liu4* Yifan Zhai5*

Yifan Zhai5*Olverembatinib (HQP1351) is a third-generation BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) (including T315I-mutant disease), exhibits drug-drug interaction (DDI) potential through cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP1A2, and CYP2B6. A physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model was constructed based on physicochemical and in vitro parameters, as well as clinical data to predict 1) potential DDIs between olverembatinib and CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 inhibitors or inducers 2), effects of olverembatinib on the exposure of CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 substrates, and 3) pharmacokinetics in patients with liver function injury. The PBPK model successfully described observed plasma concentrations of olverembatinib from healthy subjects and patients with CML after a single administration, and predicted olverembatinib exposure increases when co-administered with itraconazole (strong CYP3A4 inhibitor) and decreases with rifampicin (strong CYP3A4 inducer), which were validated by observed data. The predicted results suggest that 1) strong, moderate, and mild CYP3A4 inhibitors (which have some overlap with CYP2C9 inhibitors) may increase olverembatinib exposure by approximately 2.39-, 1.80- to 2.39-, and 1.08-fold, respectively; strong, and moderate CYP3A4 inducers may decrease olverembatinib exposure by approximately 0.29-, and 0.35- to 0.56-fold, respectively 2); olverembatinib, as a “perpetrator,” would have no or limited impact on CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 enzyme activity 3); systemic exposure of olverembatinib in liver function injury with Child-Pugh A, B, C may increase by 1.22-, 1.79-, and 2.13-fold, respectively. These simulations inform DDI risk for olverembatinib as either a “victim” or “perpetrator”.

Olverembatinib (HQP1351) is a third-generation BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) (Ren et al., 2013). In 2020, the China National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) Center for New Drug Evaluation designated olverembatinib as a potential breakthrough therapy for treatment of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that is resistant and/or intolerant to first- and second-generation TKI therapies (Center for Drug Evaluation, 1211). Shortly afterward, the NMPA approved conditional marketing authorization for olverembatinib (breakthrough therapy designation, 1211) at a dose of 40 mg orally every other day (QOD). Olverembatinib is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an orphan drug to treat CML, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and acute myeloid leukemia (Orphan Drug Designations and Approvals).

Olverembatinib binds tightly to the ATP-binding sites of native BCR-ABL1 and multiple BCR-ABL1 mutants, including the most refractory (“gatekeeper”) mutant T315I, and potently suppresses proliferation of leukemia cells expressing BCR-ABL1 (Ren et al., 2013). Compared with third-generation TKI inhibitor ponatinib, olverembatinib exhibited equivalent or more potent antiproliferative activity in both imatinib-resistant and imatinib-sensitive gastrointestinal stromal tumor cell lines (Liu et al., 2019). Clinical trials of olverembatinib have demonstrated preliminary safety and effectiveness in patients with T315I-mutated CML in the chronic phase (CML-CP) and accelerated phase (CML-AP). When administered at 40 mg QOD for 28 consecutive days per cycle over 24 months, olverembatinib elicited a major cytogenetic response (MCyR) in 79.3% patients with CML-CP (n = 121 without MCyR at baseline) and a major hematologic response (MaHR) in 78.4% patients with CML-AP (n = 37) without MaHR at baseline (Jiang et al., 2022).

Clinical pharmacokinetic data (data on file) have shown that olverembatinib is rapidly absorbed and slowly eliminated after oral administration in fasting and fed patients with CML. The median time to reach peak plasma concentration (Tmax) for olverembatinib is 6 h, with a mean apparent terminal elimination half-life (t1/2) of 32.7 h. There is no significant food effect; the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time 0 to infinity (AUC0-∞) ratio of fed to fasting is 1.28 and 1.17, respectively. After administration of a single radiolabeled dose of olverembatinib (30 mg) in healthy subjects, 87.68% of the dose was recovered in feces within 216 h, and 1.57% was recovered in urine within 96 h. About 23.95% of the cleared drug was unchanged in feces and 0.02% eliminated as the parent drug in urine.

Cytochrome P450 (CYP3A4 and CYP2C9)-mediated metabolism is a major clearance pathway. In the parlance of drug-drug interaction (DDI) studies, the “perpetrator” is the medication that affects the pharmacokinetics of another agent, whereas the “victim” is the medication whose pharmacokinetics are affected by the perpetrator. An olverembatinib clinical DDI study (data on file) showed that coadministration with itraconazole, a substrate for and inhibitor of CYP3A4, increased olverembatinib Cmax by 1.74-fold and increased area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) by 2.63-fold. On the other hand, coadministration with CYP3A4 inducer rifampicin decreased the olverembatinib maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) by 0.36-fold and 0.24-fold, respectively. However, the potential for DDI between olverembatinib and other CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers was not evaluated in DDI clinical trials. The DDI risk of olverembatinib in combine with CYP2C9 inhibitors or inducers was also not evaluated. Moreover, olverembatinib inhibits CYP2C9 and CYP2C19, and induces CYP1A2, CYP2B6, and CYP2C9, in vitro. The effect of olverembatinib as a perpetrator was also not evaluated in previous clinical DDI studies.

Increasingly, physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling applications have been used to facilitate the design of DDI studies, evaluate DDI potential in lieu of dedicated clinical studies in new drug applications (Zhao et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2015; Shebley et al., 2018). PBPK models that have been validated with clinical data have been increasingly used to predict the DDI potential for untested scenarios. To fully assess DDI risk, evaluate pharmacokinetic changes in patients with liver function injury, the primary objective of this study was to develop and verify a PBPK model for a comprehensive assessment of its clinical DDI and pharmacokinetics profiles in patients with liver function injury.

We formulated a overall strategy for qualification of the olverembatinib model and prediction of DDI (Figure 1). An olverembatinib PBPK model was constructed to simulate the plasma concentration-time profiles of olverembatinib after single-dose administration in healthy volunteers and patients with CML. To evaluate the ability of the model to predict DDI associated with olverembatinib, we conducted clinical DDI studies with strong CYP3A inhibitor and antifungal agent itraconazole and strong CYP3A inducer rifampicin to further verify the base PBPK model. Prespecified acceptance criteria (0.5–2.0-fold of observed values) were used to guide model construction and validation.

All clinical pharmacokinetic data included in the modeling were obtained from three clinical studies (Supplementary Table S1). These studies were conducted in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, as well as the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review boards or equivalent ethics committees approved the study protocols, and all study participants provided written informed consent before any study-related procedures.

In the first study, on food effects, 12 Chinese patients with CML were randomly divided into two groups (A and B) and the experiments divided into two periods. In period 1, subjects in group A received 30 mg of oral olverembatinib under fasting conditions, while subjects in group B received the same oral dose 30 min after a high-fat meal. After a seven- day washout period, subjects in both groups took the drug interchangeably in period 2 (NCT03882281).

The second study was a single-center, open-label, single-dose phase 1 trial to investigate the absorption, metabolism, and excretion of [14C]olverembatinib after a single oral 30 mg (100 µCi) dose in six healthy Chinese male subjects (NCT04126707). The third study was a phase 1, two-part trial designed to evaluate the interaction of olverembatinib and CYP3A4 perpetrators in healthy American subjects (n = 32). For uninhibited periods, subjects received one oral 20 mg dose of olverembatinib on Day 1. After a 3-day washout period, they were pretreated with 200 mg of oral itraconazole once daily for 4 days to inhibit CYP3A4 (Days 5–8). On Day 9, subjects received single oral 20-mg doses of olverembatinib and itraconazole, or itraconazole alone on Days 10 through12. For uninduced periods, subjects received one oral 40 mg dose of olverembatinib on Day 1. After a 3-day washout, subjects were pretreated with 600 mg of oral rifampicin once daily for 7 days to induce CYP3A4 (Days 5–11). On Day 12, they received single oral doses of olverembatinib at 40 mg and rifampicin at 600 mg, as well as rifampicin alone on Days 13 through15. Blood samples were collected immediately before and after drug administration at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h.

A minimal PBPK model with a first-order absorption model was used to construct the olverembatinib PBPK model, including model input parameters (Table 1). The first-order absorption model has different absorption rate constants (ka) and fraction available from dosage form (fa) to simulate absorption processes in fasting and fed states. The effective permeability of olverembatinib in the human jejunum was based on built-in predictive in silico tools (Sun et al., 2002) within the simulator and in vitro Caco-2 cell permeability data with correction by reference drugs (β-adrenoceptor blockers atenolol and propranolol). Caco-2 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma) cells are used to model the intestinal epithelial barrier. The Simcyp (Version 19.0, Certara Inc., Sheffield, UK) minimal PBPK, which treats all organs other than the intestine and liver as a single compartment (Rowland Yeo et al., 2010), was selected, along with a single adjusting compartment (SAC) distribution model. The SAC is a nonphysiologic compartment that permits adjustment to the drug concentration profile in the systemic compartment (Ke et al., 2016).

Final values of the apparent volume of SAC (Vsac), as well as the rate constants from systemic compartment to SAC (Kin) and from SAC compartment to the systemic compartment (Kout), were optimized based on observed pharmacokinetic data. The volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) was predicted from the steady-state tissue: plasma partition coefficient (Kp) calculated using mechanistic tissue distribution equations (Rodgers et al., 2005; Rodgers and Rowland, 2006). Intrinsic clearance values of 0.200 μL/min/pmol and 0.022 μL/min/pmol were assigned for CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, respectively, based on an in vitro human recombinant CYP isoenzyme study. Intersystem extrapolation factors for CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 were optimized based on clinical metabolism and excretion data in a mass balance study (NCT04126707). The mean value of renal clearance was confirmed by a phase 1 dose escalation study in 12 Chinese patients who received 50 mg of oral olverembatinib on Day 1.

Olverembatinib exhibits CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 inhibition and CYP1A2, CYP2B6 and CYP2C9 induction in vitro. The concentration of olverembatinib that supports half-maximum inhibition (Ki) was calculated using Eq. 1.

Where IC50 signifies the half-maximum inhibitory concentration; S, the concentration of P450 marker substrate; and Km, the Michaelis constant within the Michaelis-Menten equation, which is in turn used to characterize substrate-enzyme binding kinetics.

As a CYP2C9 probe substrate, the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac (2.5 µM) was incubated with human liver microsomes, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, and olverembatinib to obtain the IC50. The Michaelis constant (Km) of CYP2C9 incubated with diclofenac was obtained from reported data (Lee et al., 2014). Methods used to calculate the Ki of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 were similar. The maximum fold induction (Indmax) and half-maximum fold induction concentration (IndC50) values of olverembatinib on CYP1A2, CYP2B6, and CYP2C9 were calculated by plotting mRNA fold induction versus olverembatinib concentration after in vitro incubation with human hepatocytes.

The olverembatinib PBPK model was constructed and validated using Simcyp. Default virtual population models of healthy White and Chinese volunteers were used, except for demographic data noted in each clinical study. For model construction and validation, the virtual trials used in each simulation were based on corresponding doses used in each of the clinical studies (Supplementary Table S1). The constructed PBPK model was validated by comparing the predicted model and observed pharmacokinetic parameters and/or plasma concentration profiles. The PBPK model predictive performance was preliminarily evaluated by overlaying the observed concentration-time profile with the model-predicted profile and 90% predictive interval. The quantitative assessment was conducted by pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax and AUC), as represented by the ratio of the predicted to the observed value. The model performance success criterion was acceptable if it fell within the 0.5- to 2.0-fold range.

A food effect study (NCT03882281) was conducted in Chinese patients with CML, for whom there was no CML population library in Simcyp. As a result, a “Sim-Chinese healthy volunteers” simulated population was used for model verification under the assumption of equivalent pharmacokinetics in patients with CML and healthy volunteers.

After validation, the PBPK model was used to simulate untested clinical DDI scenarios for olverembatinib as either a victim or perpetrator (Zhang et al., 2022). As a victim, olverembatinib pharmacokinetics were simulated after coadministration with CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 perpetrators according to a prespecified dose scheme (Table 2). Substrate pharmacokinetics of CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP1A2, CYP2B6, and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) were simulated after coadministration with olverembatinib (as a perpetrator), also according to a protocol-based dose scheme (Table 2).

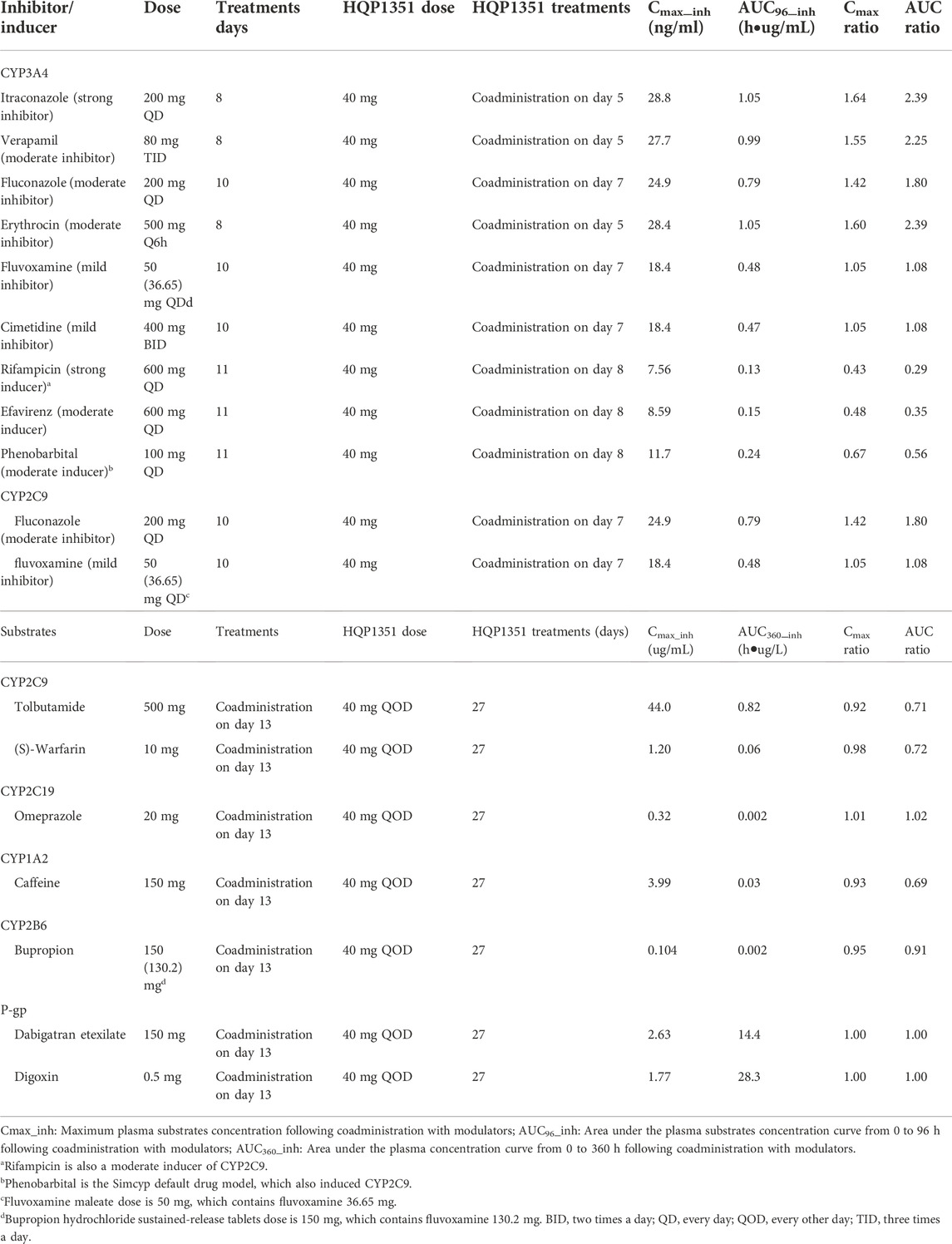

TABLE 2. Simulated Cmax and AUC ratios of olverembatinib (HQP1351) as victim in the presence and absence of CYP modulators and simulated Cmax and AUC of CYP substrates when olverembatinib as CYP modulators.

To evaluate the effect of liver function on olverembatinib pharmacokinetics, we performed the simulation in virtual patients with liver function injury classified as mild (A), moderate (B) and severe (C) by the Child-Pugh (CP) classification, including a prespecified dose scheme (Table 3. Ten virtual trials were simulated for each scenario to assess interstudy variability, and 10 subjects (aged 20–50 years and 50% female) participated in each simulated trial. All DDI model simulations were conducted with the virtual “Sim-Chinese healthy volunteers” population except for a P-gp-mediated DDI simulation, which was conducted with the representative population “Sim-Chinese healthy volunteers” population. All liver cirrhosis simulations were conducted with the default virtual population “Sim-Healthy volunteers, “Sim-Cirrhosis CP-A, “Sim-Cirrhosis CP-B,” and “Sim-Cirrhosis CP-C″ populations. Except for olverembatinib, all compound files in Simcyp V.19 default were used.

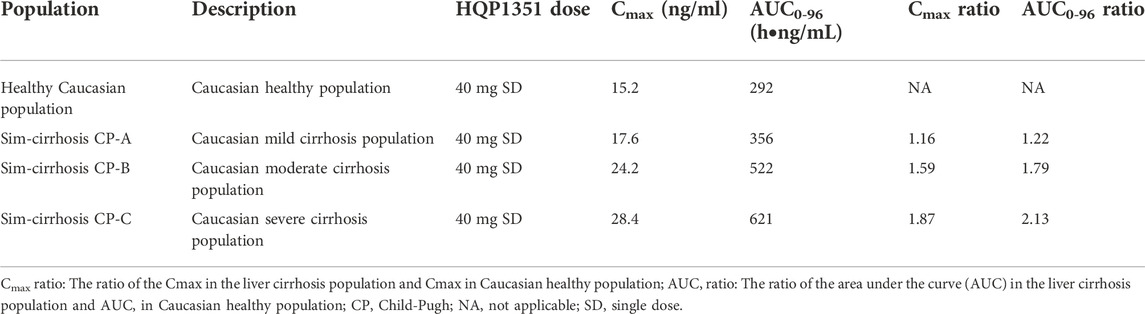

TABLE 3. Simulated Cmax and AUC0-96 of olverembatinib (HQP1351) in different liver cirrhosis populations.

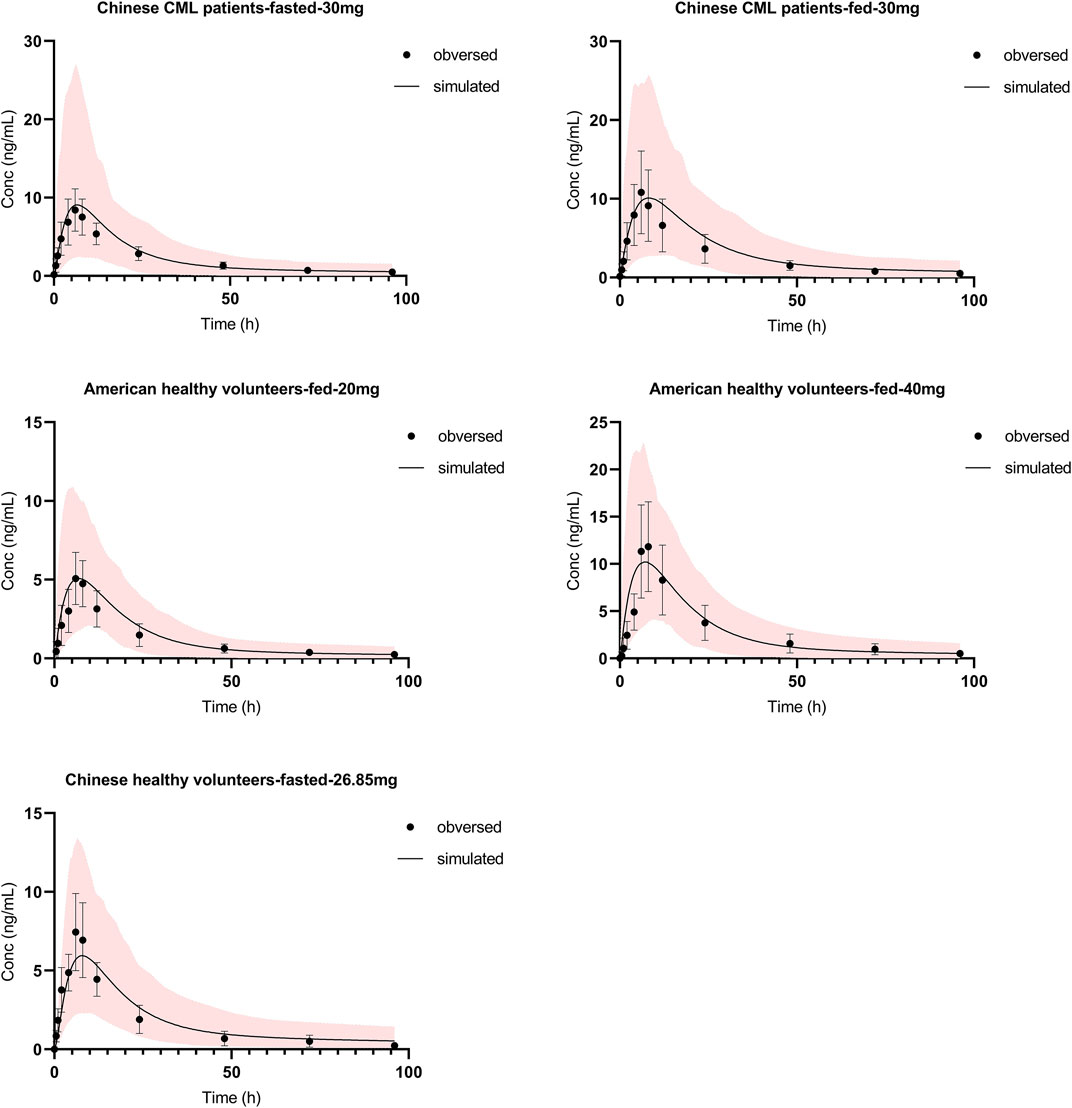

Absorption and distribution behaviors of olverembatinib were effectively predicted using first-order absorption kinetics with a minimal PBPK model. Using the same dose regimen as in dosed patients, a simulation was performed. The predicted plasma concentration profiles after single oral 30 mg doses (fasting or fed) were consistent with observed profiles in Chinese patients with CML in the food effect study (Figure 2). Cmax ratios (predicted/observed) in fasting and fed conditions were 1.13 and 1.02, respectively. AUC ratios (predicted/observed) in fasting and fed conditions were 0.95 and 1.12, respectively. Similarly, predicted concentration profiles after a single oral dose of 20 or 40 mg were consistent with those observed data in healthy American volunteers. The Cmax and AUC ratio (predicted/observed) ranges were 0.88–1.06 and 0.88 to 1.03, respectively. In the mass balance study, the observed olverembatinib concentration in healthy Chinese volunteers were within the prediction interval. The Cmax and AUC ratios (predicted/observed) were 0.76 and 1.12, respectively.

FIGURE 2. Olverembatinib PBPK model verification. Observed (mean and standard deviation, dots and bar) and simulated (solid lines) mean plasma concentration-time profiles of olverembatinib in different populations following single oral doses of olverembatinib (30, 20, 40 or 26.85 mg). The shaded area is the 5–95% range in concentrations from 1,000 simulated healthy Chinese or American adult subjects.

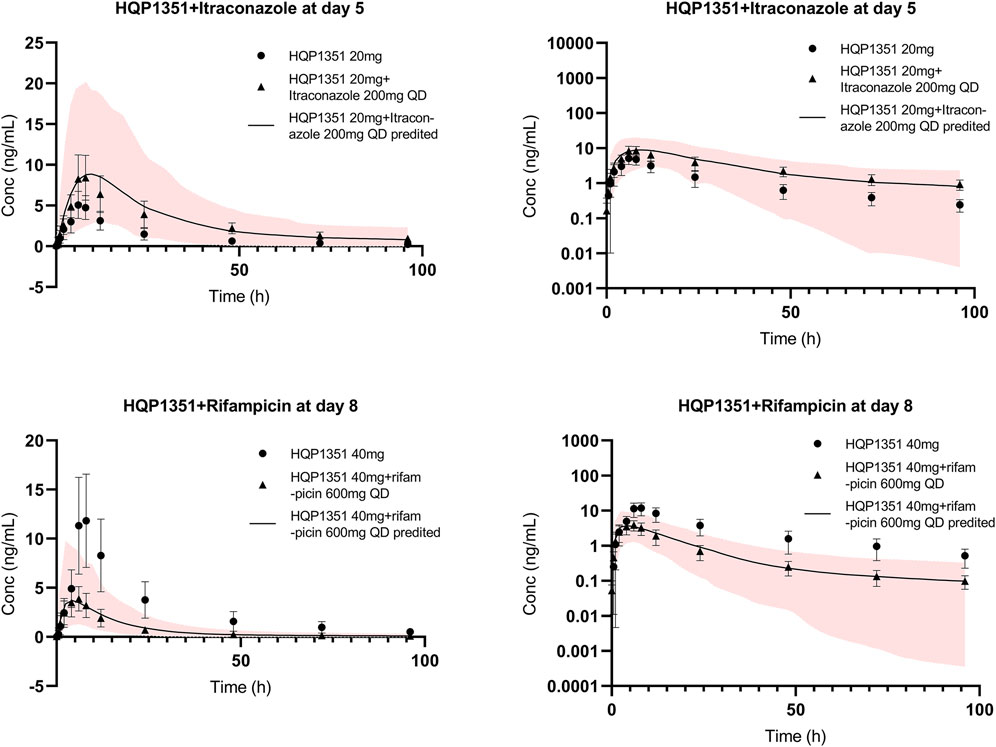

The applicability of the PBPK model to assess the magnitude of drug interactions between olverembatinib and CYP3A4 perpetrators was verified. The model simulated the concentration-time profiles of 20 mg of olverembatinib administered with CYP3A4 inhibitor itraconazole in the clinical DDI study (Figure 3). Itraconazole’s effect on olverembatinib was simulated in profiles for changes in Cmax and AUC (Supplementary Table S3). The observed Cmax and AUC ratios of olverembatinib in the presence or absence of itraconazole were 1.74 and 2.63, respectively. The corresponding PBPK model predicted C max and AUC ratios of 1.69 and 2.22, respectively, which were consistent with observed values in the clinical DDI study.

FIGURE 3. Further verification of olverembatinib PBPK model. Observed (mean and standard deviation, dots for single dose, triangle for coadministration and bar) and simulated (solid lines for coadministration) mean plasma concentration-time profiles of olverembatinib in healthy American volunteers following oral doses of olverembatinib (left panels = linear scale; right panels = semi-log scale). The shaded area is the 5%–95% range in concentrations from 1,000 simulated healthy American adult subjects.

The effect of CYP3A4 inducer rifampicin on olverembatinib was demonstrated by simulating the pharmacokinetic profiles of the TKI when coadministered with the antibiotic. The simulation was acceptable when compared with the observed concentration-time profiles of olverembatinib among healthy American volunteers in the rifampicin DDI study (Figure 3). Observed Cmax and AUC ratios of olverembatinib in the presence and absence of rifampicin were 0.36 and 0.24, respectively, compared to predicted ratios of 0.38 and 0.27, respectively. The PBPK model-predicted mean Cmax and AUC ratios of olverembatinib (at 40 mg) with or without rifampicin were less than 1.5 times the observed values (Supplementary Table S3).

The constructed PBPK model was used to simulate other untested clinical DDI scenarios for olverembatinib during coadministration with CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 inhibitors and inducers in healthy Chinese volunteers. Simulated olverembatinib pharmacokinetic parameters and corresponding ratios with and without coadministration of CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 modulators are outlined (Table 2).

PBPK simulations indicated that olverembatinib AUC0–96h (area under the plasma drug concentration-time curve from 0 to 96 h) may increase by approximately 2.39- and by 1.80- to 2.39-fold during coadministration with strong and moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors, respectively. Simulations suggested that the strong and moderate CYP3A4 inducers may decrease the AUC0–96h of olverembatinib by 0.29- and 0.56- to 0.35-fold, respectively. Based on the PBPK model simulations, predicted ratios of olverembatinib AUC0–96h in the presence or absence of moderate and mild CYP2C9 inhibitors were 1.80 and 1.08, respectively.

To assess the potential effects of olverembatinib on the pharmacokinetics of CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP1A2, CYP2B6, and CYP3A4 substrate drugs, the predicted pharmacokinetic parameters and mean Cmax and AUC ratios of substrate drugs with or without olverembatinib were simulated (Table 2).

Tolbutamide (which interferes with binding of anticoagulant warfarin enantiomers) and (S)-warfarin are substrates of CYP2C9. PBPK simulations indicate that tolbutamide and (S)-warfarin AUC0–360h (area under the plasma drug concentration-time curve from 0 to 360 h) may decrease by approximately 0.71- and 0.72-fold, respectively during coadministration with olverembatinib. Similarly, simulations suggested that olverembatinib may increase the AUC0–360h of CYP2C19 substrate and proton pump inhibitor omeprazole by 1.02-fold and decrease the AUC0–360h of CYP1A2 substrate of caffeine (anaesthetic) and CYP2B6 substrate and antidepressant bupropion by 0.69- and 0.91-fold, respectively.

As a DDI perpetrator, olverembatinib has no or limited impact on the enzyme activity of CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP1A2, or CYP2B6. Finally, we assessed the potential effects of olverembatinib on the pharmacokinetics of P-gp substrates dabigatran etexilate (low-molecular-weight prodrug of the direct thrombin inhibitor) and the cardiac glycoside digoxin. The AUC0–360h ratio for dabigatran etexilate or digoxin in the presence or absence of olverembatinib was 1.0 each.

In this simulation, we used a liver cirrhosis population model based on Caucasian people. The ratio of the AUC in liver cirrhosis and healthy populations was assumed to be equal in both Caucasian and Chinese people. PBPK simulations indicated that predicted ratios of olverembatinib AUC0–96h among patients in cirrhosis CP-A, CP-B, and CP-C, relative to healthy volunteers, were 1.22, 1.79, and 2.13, respectively. For Cmax, the model-predicted ratios in patients with CP-A, CP-B, and CP-C cirrhosis, relative to healthy volunteers, were 1.16, 1.59, and 1.87, respectively (Table 3).

This study developed a model-based approach for comprehensive evaluation of olverembatinib DDI profiles, including evaluation of its potential as a victim of CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 and as a perpetrator for CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP1A2, CYP2B6, and P-gp substrates. PBPK modeling was used to assess metabolic DDI risks as part of the clinical pharmacology strategy for the development of olverembatinib. Robustness of the current PBPK model was demonstrated by the similarity of model predictions with observed clinical data after a single dose of olverembatinib across various drug interaction pathways. Because hepatic metabolism is the principal pathway governing elimination of olverembatinib, the effect of liver function injury on exposure to olverembatinib was evaluated by simulating pharmacokinetic profiles in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Olverembatinib is metabolized by multiple CYP isozymes, with higher relative contributions with CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 (60.0% and 21.6%; data from human liver microsome study). The clinical DDI study indicated that the AUC of olverembatinib (20 or 40 mg single dose) increased 2.61-fold (or by 163%) after itraconazole treatment (200 mg daily [QD]) and decreased 0.24-fold (or by 76%) after rifampicin administration. In addition, a PBPK modeling simulation demonstrated that a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor increased olverembatinib AUC by 139%. Moderate and mild CYP3A4 inhibitors (some of which overlap as CYP2C9 inhibitors) increased olverembatinib exposures by 80%–139% and 8%, respectively.

Strong and moderate CYP3A4 inducers (some of which overlap as CYP2C9 inducers) decreased olverembatinib exposure by 44%–71%. In our study, moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor and antibiotic erythromycin was administered at a higher-than-routine dose (500 mg every 6 h) and hence showed an inhibitory effect similar to that with strong CYP3A4 inhibitor itraconazole. After adjustment of the erythromycin dose to 500 mg 3 times a day, the mean Cmax and AUC0-t ratios for olverembatinib in the presence or absence of erythrocin were 1.60 and 2.39, respectively. Both CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 were inhibited by fluconazole and antidepressant fluvoxamine and induced by rifampicin and the barbiturate phenobarbital. Olverembatinib exposures changed significantly after coadministration with these drugs. Based on the clinical DDI study and predictions of the PBPK model, coadministration of olverembatinib with strong and moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers is not recommended.

In vitro studies suggested that olverembatinib is a weak CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 inhibitor, and a weak CYP1A2, CYP2B6 and CYP2C9 inducer. The PBPK model was used to evaluate the DDI potential of olverembatinib and CYP/P-gp substrates. Olverembatinib decreased tolbutamide and (S)-warfarin (CYP2C9 substrates), caffeine (CYP1A2 substrate), and bupropion (CYP2B6 substrate) exposures by 28%–29%, 31%, and 9%, respectively. Olverembatinib increased omeprazole (CYP2C19 substrate) exposure by 2% but did not change exposures of dabigatran etexilate and digoxin (P-gp substrates). As a DDI perpetrator, olverembatinib had no or limited impact on activities of CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and P-gp.

In addition, olverembatinib is neither a substrate nor inhibitor of OATP1B1 (organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1), OATP1B3 (organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B3), OAT1 (organic anion transporter 1), OAT3 (organic anion transporter 3), OCT2 (organic cation transporter 2), MATE1 (multidrug and toxin extrusion 1), or MATE2K (multidrug and toxin extrusion 2). Olverembatinib also showed no obvious in vivo inhibition on P-gp and BCRP (breast cancer resistance protein) and exerted a negligible perpetrator effect on substrates of common CYP enzymes and transporters. However, these findings will need to be further validated by additional clinical studies.

Hepatic elimination is an important mechanism that regulates overall clearance of olverembatinib. In the current simulation, we show that respective exposures of olverembatinib in Caucasian populations with mild, moderate, and severe cirrhosis were 22%, 79%, and 113% higher than in healthy volunteers. Because no clinical data were obtained before this study, the olverembatinib pharmacokinetic assessment in liver function injury populations was not validated. The simulation results indicate that patients with mild liver injury can receive the same dose of olverembatinib as those with normal liver function. An appropriate dose adjustment should be considered for patients with moderate liver injury by weighing the benefits and risks. However, in patients with severe cirrhosis, olverembatinib is not recommended. Additional clinical studies in patients with liver cirrhosis are needed to optimize the dose regimen.

A limitation of this study is that the transporters mediated disposition was not integrated in PBPK model since olverembatinib is a substrate of P-gp, BCRP (breast cancer resistance protein). The effects of transporters expressed on the gut and liver have not been investigated.

Besides, the B/P ratio was obtained from healthy volunteer blood, however, in patients with CML, too many myeloid cells become granulocytes (red blood cells, platelets and several white blood cell types). So, red blood cell count might change B/P ratio in CML patients. The B/P ratio of olverembatinib in CML patients need a further study. Furthermore, the model simulation for liver cirrhosis patients was not validated by clinical data. We believe that further research is needed on this point.

A robust PBPK model of olverembatinib was constructed and validated to predict CYP3A4-and CYP2C9-mediated drug interactions. The validated PBPK model was utilized to forecast DDI risks where no clinical data were available. Simulations suggested that no dose adjustment for olverembatinib is required when the TKI is coadministered with mild CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 inhibitors. With moderate and strong CYP3A4 or CYP2C9 inhibitors and inducers, coadministration is not recommended. Dose adjustment might be not needed in light liver cirrhosis patients with CP-A. Moderated liver cirrhosis patients should use olverembatinib with caution and are suggested to monitor liver function. But the severe liver cirrhosis patients are not suggested to use olverembatinib.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by 1) Frontage Clinical Services, Inc. 2) Medical ethics committee of peking university people’s hospital. 3) Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The animal study was reviewed and approved by Shanghai Medicilon Inc.

ZY performed the PBPK modeling and simulation and conducted statistical and graphical analysis. ZL drafted this manuscript and was responsible for article revision. HW and YZ provided funding and supervised this study. MZ and ZH assisted the PBPK modeling and simulation and quality control. YL assisted the paper quality control. HW contributed the in vivo and in vitro data of olverembatinib. HL and YZ supervised the study. XY guided the modeling operation and optimization, and prepared original draft. DL conceived the study conceptualization and methodology.

The research was funded by Guangzhou Healthquest Pharma Co., Ltd and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (No. INV-007625).

We thank Ashutosh K. Pathak, MD, PhD, MBA, FRCP (Edin.), Stephen W. Gutkin, Paul O. Fletcher, PhD, and Ndiya Ogba, PhD, with Guangzhou Healthquest for providing editorial assistance and substantive input in manuscript preparation. This study and its report were supported by Guangzhou Healthquest Pharma group Corp Ltd. (Hong Kong).

Authors HW and YZ were employed by the company Guangzhou Healthquest Pharma Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022.1065130/full#supplementary-material

breakthrough therapy designation. NMPA [Available at: https://www.cde.org.cn/main/xxgk/listpage/da6efd086c099b7fc949121166f0130c.

Center for Drug Evaluation, NMPA. Breakthrough therapy designation. Available at: https://www.cde.org.cn/main/xxgk/listpage/da6efd086c099b7fc949121166f0130c

Jiang, Q., Li, Z., Qin, Y., Li, W., Xu, N., Liu, B., et al. (2022). Olverembatinib (HQP1351), a well-tolerated and effective tyrosine kinase inhibitor for patients with T315I-mutated chronic myeloid leukemia: Results of an open-label, multicenter phase 1/2 trial. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15 (1), 113. doi:10.1186/s13045-022-01334-z

Jones, H. M., Chen, Y., Gibson, C., Heimbach, T., Parrott, N., Peters, S. A., et al. (2015). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling in drug discovery and development: A pharmaceutical industry perspective. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 97 (3), 247–262. doi:10.1002/cpt.37

Ke, A., Barter, Z., Rowland-Yeo, K., and Almond, L. (2016). Towards a best practice approach in PBPK modeling: Case example of developing a unified efavirenz model accounting for induction of CYPs 3A4 and 2B6. CPT. Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 5 (7), 367–376. doi:10.1002/psp4.12088

Lee, M. Y., Borgiani, P., Johansson, I., Oteri, F., Mkrtchian, S., Falconi, M., et al. (2014). High warfarin sensitivity in carriers of CYP2C9*35 is determined by the impaired interaction with P450 oxidoreductase. Pharmacogenomics J. 14 (4), 343–349. doi:10.1038/tpj.2013.41

Liu, X., Wang, G., Yan, X., Qiu, H., Min, P., Wu, M., et al. (2019). Preclinical development of HQP1351, a multikinase inhibitor targeting a broad spectrum of mutant KIT kinases, for the treatment of imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cell Biosci. 9, 88. doi:10.1186/s13578-019-0351-6

Orphan Drug Designations and Approvals. FDA [Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd/listResult.cfm.

Ren, X., Pan, X., Zhang, Z., Wang, D., Lu, X., Li, Y., et al. (2013). Identification of GZD824 as an orally bioavailable inhibitor that targets phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated breakpoint cluster region-Abelson (Bcr-Abl) kinase and overcomes clinically acquired mutation-induced resistance against imatinib. J. Med. Chem. 56 (3), 879–894. doi:10.1021/jm301581y

Rodgers, T., Leahy, D., and Rowland, M. (2005). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling 1: Predicting the tissue distribution of moderate-to-strong bases. J. Pharm. Sci. 94 (6), 1259–1276. doi:10.1002/jps.20322

Rodgers, T., and Rowland, M. (2006). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling 2: Predicting the tissue distribution of acids, very weak bases, neutrals and zwitterions. J. Pharm. Sci. 95 (6), 1238–1257. doi:10.1002/jps.20502

Rowland Yeo, K., Jamei, M., Yang, J., Tucker, G. T., and Rostami-Hodjegan, A. (2010). Physiologically based mechanistic modelling to predict complex drug-drug interactions involving simultaneous competitive and time-dependent enzyme inhibition by parent compound and its metabolite in both liver and gut - the effect of diltiazem on the time-course of exposure to triazolam. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 39 (5), 298–309. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2009.12.002

Shebley, M., Sandhu, P., Emami Riedmaier, A., Jamei, M., Narayanan, R., Patel, A., et al. (2018). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model qualification and reporting procedures for regulatory submissions: A consortium perspective. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 104 (1), 88–110. doi:10.1002/cpt.1013

Sun, D., Lennernas, H., Welage, L. S., Barnett, J. L., Landowski, C. P., Foster, D., et al. (2002). Comparison of human duodenum and Caco-2 gene expression profiles for 12, 000 gene sequences tags and correlation with permeability of 26 drugs. Pharm. Res. 19 (10), 1400–1416. doi:10.1023/a:1020483911355

Troutman, M. D., and Thakker, D. R. (2003). Efflux ratio cannot assess P-glycoprotein-mediated attenuation of absorptive transport: Asymmetric effect of P-glycoprotein on absorptive and secretory transport across caco-2 cell monolayers. Pharm. Res. 20 (8), 1200–1209. doi:10.1023/a:1025049014674

Yang, S., Qiu, Z., Zhang, Q., Chen, J., and Chen, X. (2014). Inhibitory effects of calf thymus DNA on metabolism activity of CYP450 enzyme in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 29 (6), 475–481. doi:10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-13-RG-131

Zhang, M., Yu, Z., Yao, X., Lei, Z., Zhao, K., Wang, W., et al. (2022). Prediction of pyrotinib exposure based on physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model and endogenous biomarker. Front. pharmacol. 13, 972411. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.972411

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukemia, cytochrome P450, drug-drug interactions, modeling, physiologically based pharmacokinetics, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Citation: Yu Z, Lei Z, Yao X, Wang H, Zhang M, Hou Z, Li Y, Zhao Y, Li H, Liu D and Zhai Y (2022) Potential drug-drug interaction of olverembatinib (HQP1351) using physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. Front. Pharmacol. 13:1065130. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1065130

Received: 09 October 2022; Accepted: 23 November 2022;

Published: 13 December 2022.

Edited by:

Simona Pichini, National Institute of Health (ISS), ItalyReviewed by:

Jinping Gu, Zhejiang University of Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Yu, Lei, Yao, Wang, Zhang, Hou, Li, Zhao, Li, Liu and Zhai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dongyang Liu, bGl1ZG9uZ3lhbmdAdmlwLnNpbmEuY29t; Yifan Zhai, eXpoYWlAYXNjZW50YWdlLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.