94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol. , 12 January 2023

Sec. Ethnopharmacology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1029949

This article is part of the Research Topic Safety and Toxicity Profiling of Herbal Drugs View all 6 articles

Background: Chronic pruritus (CP) is a common and aggravating symptom associated with skin and systemic diseases. Although clinical reports suggest that Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) is safe and effective in Chronic pruritus treatment, evidence to prove it is lacking. Therefore, in this review, we evaluated the therapeutic effects and safety of Chinese herbal medicine for the treatment of Chronic pruritus.

Methods: Nine databases were searched for relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from the inception of the database to 20 April 2022. The randomized controlled trials that compared the treatment of Chinese herbal medicine or a combination of Chinese herbal medicine and conventional western medicine treatment (WM) with western medicine treatment intervention for patients with Chronic pruritus were selected. We evaluated the effects of treatment with Chinese herbal medicine on the degree of pruritus, the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score, response rate, recurrence rate, and incidence of adverse events in patients with Chronic pruritus. The risk of bias in each trial was evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. The RevMan software (version 5.3) was used for performing meta-analyses to determine the comparative effects.

Results: Twenty-four randomized controlled trials were included, compared with placebo, moderate-quality evidence from one study showed that Chinese herbal medicine was associated with reduced visual analogue scale (VAS) (MD: −2.08; 95% CI = −2.34 to −1.82). Compared with western medicine treatment, low-to moderate-quality evidence from 8 studies indicated that Chinese herbal medicine was associated with reduced visual analogue scale, 4 studies indicated that Chinese herbal medicine was associated with reduced Dermatology Life Quality Index (MD = −1.80, 95% CI = −2.98 to −.62), and 7 studies indicated that Chinese herbal medicine was associated with improved Effective rate (RR: 1.26; 95% CI = 1.19–1.34). Compared with combination of Chinese herbal medicine and western medicine treatment, 16 studies indicated that Chinese herbal medicine was associated with reduced visual analogue scale, 4 studies indicated that Chinese herbal medicine was associated with reduced Dermatology Life Quality Index (MD = −2.37, 95% CI = −2.61 to −2.13), and 13 studies indicated that Chinese herbal medicine was associated with improved Effective rate (RR: 1.28; 95% CI = 1.21–1.36). No significant difference in the occurrence of adverse events in using Chinese herbal medicine or western medicine treatment was reported.

Conclusion: The efficacy of Chinese herbal medicine used with or without western medicine treatment was better than western medicine treatment in treating chronic pruritus. However, only a few good studies are available regarding Chronic pruritus, and thus, high-quality studies are necessary to validate the conclusions of this study.

Chronic pruritus (CP) is an unpleasant sensation that induces an urge to scratch and lasts for at least 6 weeks (Rajagopalan et al., 2017; Villa-Arango et al., 2019). It is often accompanied by skin diseases [e.g., psoriasis, atopic dermatitis (AD), and lichen planus] and systemic diseases (e.g., end-stage renal disease, diabetes, hypothyroidism, chronic hepatobiliary disease, and malignancy) (Twycross et al., 2003; Ständer et al., 2007; Olek-Hrab et al., 2016; Weisshaar et al., 2019). Several population-based studies have suggested that one in five individuals in the general population experience CP at least once in their lifetime, with a 12-month incidence of 7% (Matterne et al., 2011). The prevalence of CP in the general adult population is approximately 13.5% (Rajagopalan et al., 2017). In patient populations, the incidence of CP varies depending on its underlying etiology, ranging from 25% in hemodialysis patients (Weiss et al., 2016) to 100% in patients with skin conditions, such as urticaria and AD (Szepietowski et al., 2002; Szepietowski et al., 2004). CP can lead to sleep disturbance, fatigue, inability to work, anxiety, and depression, resulting in a considerable decline in health-related quality of life (Schneider et al., 2006; Steinke et al., 2018; Stumpf et al., 2018; Schneider et al., 2022). Additionally, CP imposes a significant burden on society by increasing healthcare costs and posing treatment challenges.

The cause of CP is extremely complicated and includes dermatological, systemic, neurological, psychiatric, mixed, or unknown factors (Kretzmer et al., 2008; Matterne et al., 2013; Shive et al., 2013; Hay et al., 2014; Pereira et al., 2016). CP is a challenging condition to manage due to its extremely complicated aetiology. The treatment of CP mainly includes the treatment of the underlying disease and topical treatment. Conventional western medicine treatment (WM) (Andrade et al., 2020) includes emollient creams, cooling lotions, topical corticosteroids, topical antidepressants, systemic antihistamines, systemic antidepressants, systemic anticonvulsants, and phototherapy, as well as, symptomatic and supportive care. However, the commonly (Hay et al., 2014) used treatment methods have limited efficacy and might be associated with significant side effects. Therefore, patients often experience severe, long-term itching without improvement, which exacerbates the negative effects on the quality of life and psychosomatic responses (Dalgard et al., 2020). Therefore, alternative strategies for treating CP need to be investigated.

Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) is an essential part of monotherapy or substitute supplementary treatment of CP and has been used in China for many years. The treatment of itching by administering CHM (mainly orally), CHM fumigation, external washing, acupoint therapy, etc., can effectively relieve itching. Many clinical and experimental studies have confirmed the effectiveness of CHM in the treatment of CP (Bedi and Shenefelt, 2002; Xue et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2021). For example, Qinzhuliangxue decoction has anti-inflammatory effects, and it increases the threshold of pruritus caused by histamine phosphate, which is effective in treating CP caused by specific eczema (Ma et al., 2020). Turmeric has anti-inflammatory and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein–lowering effects and can be used for treating uremic pruritus (Pakfetrat et al., 2014). Animal experiments have shown that administering Huanglian Jiedu decoction can treat AD by regulating the antigen presentation function of dendritic cells, weakening T-lymphocyte activation, and subsequently exerting anti-inflammatory and anti-pruritus effects (Xu et al., 2021). Although several studies have treated CP with CHM or a combination of CHM and WM, systematic analyses and evidence synthesis of CHM treatment on CP are limited. Therefore, new evidence-synthesis methods need to be developed in this field. In this systematic review, we summarized and evaluated studies on the efficacy and safety of using CHM for monotherapy or adjuvant therapy in the treatment of CP to promote its clinical application.

The review protocol was registered on the International Platform for the Registration of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Schemes (INPLASY202260103), and it is presented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement (Liberati et al., 2009).

Nine electronic databases were searched for relevant studies from the date of the inception of the database to 20 April 2022. The databases searched were PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane, Chinese Biological Medicine, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, the Chinese Scientific Journal Database, the Wanfang database, and Clinical Trials.gov. Publications of all languages were accepted. Relevant studies were retrieved using Medical Subject Heading terms or keywords combined with free text words, such as chronic pruritus, pruritus, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), Chinese herbal medicine, randomized control, and random. These keywords were modified according to the needs of different databases. The PubMed search strategies are shown in Table 1.

We evaluated the efficacy and safety of CHM for treating CP. The inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows: (Rajagopalan et al., 2017) a randomized controlled trial (RCT) was performed with or without blinding; (Villa-Arango et al., 2019) the participants were diagnosed with chronic systemic pruritus (pruritus duration >6 weeks) (Ständer et al., 2007); (Ständer et al., 2007) the participants were not restricted to a specific age group, gender, race, disease duration, or concomitant disease; (Weisshaar et al., 2019) the experimental group was treated with oral, external, or a combination of oral and external CHM, irrespective of the medicinal form used (e.g., proprietary Chinese medicine, Chinese herbal decoction, granules, capsules, tablets, pills, or injections), whereas, the control group was treated with a placebo or conventional Western medicine (WM); (Olek-Hrab et al., 2016) the pruritus index (using the visual analogue scale [VAS] (Furue et al., 2013)) was reported in the study.

The exclusion criteria for the studies were as follows: (Rajagopalan et al., 2017) the participants were not diagnosed with CP, or the study did not mention that the duration of pruritus was >6 weeks; (Villa-Arango et al., 2019) the RCT did not use the VAS to assess pruritus; (Ständer et al., 2007) the control group was administered other TCM interventions (such as CHM, acupuncture, or massage) other than WM. The studies were screened based on the selection criteria by two independent reviewers (WJ and CYH), and a third reviewer (WXB) resolved any discrepancy that might have occurred between the assessments of the two reviewers.

The main outcome measure was the pruritus index evaluated using VAS. VAS consists of a 10-cm line indicated with points 0 to 10 (0 = no itching, 10 = worst imaginable itching) on which patients indicate pruritus intensity by marking the point that corresponds to the severity of their pruritus (Furue et al., 2013). Secondary outcomes included the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score (Finlay and Khan, 1994), effective rate, recurrence rate, and adverse effect rate.

After retrieving the articles, the documents were managed, and duplicates were removed using the document management software Endnote X9. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, two reviewers (WJ and CYH) independently screened the titles and abstracts to select relevant studies, and then, they screened the full texts for the final selection. Additionally, the name of the authors, the year of publication, sample size, the sex and age of the participants, details of the intervention, outcome measures, and adverse reactions were independently extracted by two reviewers (WJ and CYH) using a pre-defined data collection form. Then, the extracted data were cross-checked for accuracy by two other reviewers (HJL and YXW). In case information in the included articles was not clear, one of the reviewers (HJL) contacted the authors of the specific study through telephone or email for clarification. The included articles were evaluated by two reviewers (WJ and CYH) using ROB2.0. The six dimensions included random isolation process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result, and overall bias. If disagreement occurred between the reviewers, discussions were held with the two other reviewers (XYH and WW) to arrive at a consensus.

Cochrane systematic review software Review Manager 5.3 and Stata 14.0 were used to analyze the data statistically. The quality of evidence was summarized and graded using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology. A table was created to summarize the results using the GRADE profiler 3.6.1 software. Risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate dichotomous data, continuous data, mean difference (MD), and standard mean difference. A fixed-effects model was used if the data were homogeneous (Cochrane Q, p > .1, I2 < 50%), and a random-effects model was used if the data were heterogeneous. p-values <.05 were considered to be statistically significant. When a certain level of heterogeneity was observed, and we had sufficient studies, subgroup analyses were performed to account for the heterogeneity. Funnel plots were used to assess publication bias when at least 10 trials were available.

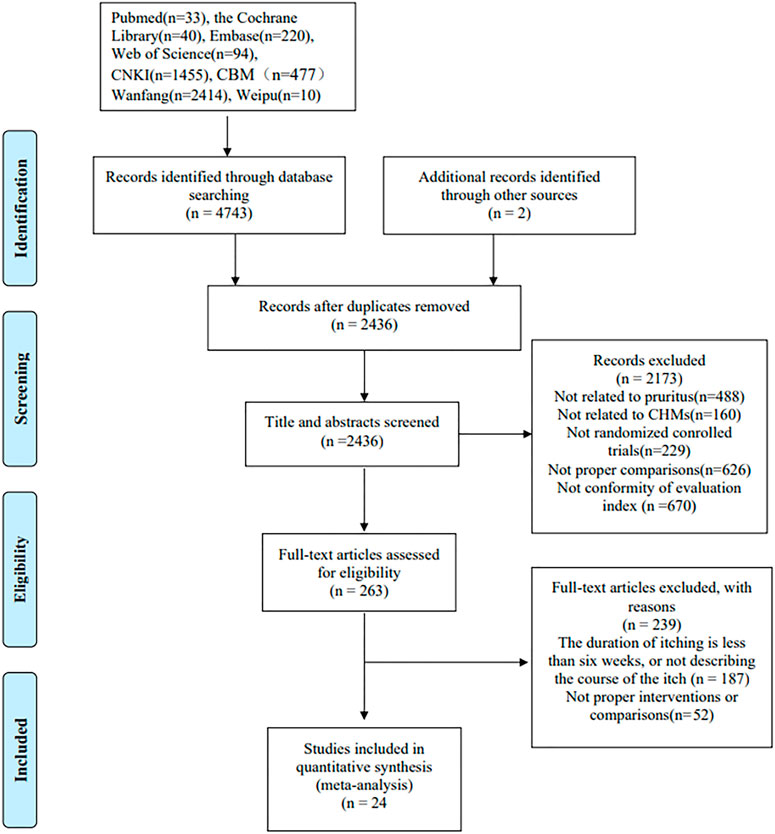

Following our search strategy, 4,745 articles were initially identified, and 2,436 articles were selected after removing duplicates. After initially screening the titles and abstracts for inclusion and exclusion criteria, 2,173 articles were excluded. The remaining 263 studies were thoroughly reviewed, and 239 articles were removed for various reasons. Finally, 24 eligible RCTs (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Mehrbani et al., 2015; Wei and Li, 2017; Yine and Li, 2017; Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Hu and Feng, 2018; Liu, 2018; Ma, 2018; Qi, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Zhang, 2018; Hanhua Cao et al., 2019; Li, 2019; Liu, 2019; QIi, 2019; Qing Wu et al., 2020; Rui Tao et al., 2020; Xinwei Guo et al., 2020; Yu, 2020; Bin Zhao, 2021; Lan, 2021; Liu, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) consisting of 2,313 participants were included in the meta-analysis. The study selection process is presented in Figure 1, the characteristics of the included trials are presented in Table 2, and the characteristics of the included TCM are presented in Table 3; Supplementary Table S1.

FIGURE 1. A flow diagram of the study selection process. CNKI, China National Knowledge Infrastructure; CBM, Chinese Biological Medicine; CHM, Chinese herbal medicine.

All studies were published between 2007 and 2022. The number of participants in the studies varied from 42 to 300, and the treatment duration varied from 14 to 60 days. The participants had different types of disease along with CP. Among the 24 studies, the experimental groups of eight studies (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Wei and Li, 2017; Liu, 2018; Qi, 2018; Liu, 2019; Rui Tao et al., 2020; Xinwei Guo et al., 2020; Yu, 2020) used CHM treatment, of which 5 (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Wei and Li, 2017; Liu, 2018; Rui Tao et al., 2020; Yu, 2020) had a treatment period of ≤4 weeks and three studies (Qi, 2018; Liu, 2019; Xinwei Guo et al., 2020) had a treatment period of >4 weeks. The experimental groups of 16 studies (Mehrbani et al., 2015; Yine and Li, 2017; Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Hu and Feng, 2018; Ma, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Zhang, 2018; Hanhua Cao et al., 2019; Li, 2019; QIi, 2019; Qing Wu et al., 2020; Bin Zhao, 2021; Lan, 2021; Liu, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) used a combination of CHM and WM treatment, of which four (Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Zhang, 2018; Hanhua Cao et al., 2019; Lan, 2021) used CHM externally, one (Qing Wu et al., 2020) used CHM internally and externally, and 11 (Mehrbani et al., 2015; Yine and Li, 2017; Hu and Feng, 2018; Ma, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Li, 2019; QIi, 2019; Bin Zhao, 2021; Liu, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) used CHM orally. Among the control groups, one (Mehrbani et al., 2015) study used a placebo, and the remaining 23 used WM (Table 2). Regarding outcomes, all 24 studies reported pruritus indicators using the VAS scores, and eight studies (Wei and Li, 2017; Yine and Li, 2017; Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Liu, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Liu, 2019; Xinwei Guo et al., 2020; Bin Zhao, 2021) reported DLQI scores. Additionally, 20 studies (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Wei and Li, 2017; Yine and Li, 2017; Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Liu, 2018; Ma, 2018; Qi, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Zhang, 2018; Hanhua Cao et al., 2019; Li, 2019; Liu, 2019; Qing Wu et al., 2020; Rui Tao et al., 2020; Yu, 2020; Bin Zhao, 2021; Lan, 2021; Liu, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) reported total effective rates, and 13 studies (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Mehrbani et al., 2015; Yine and Li, 2017; Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Hu and Feng, 2018; Qi, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Liu, 2019; Qing Wu et al., 2020; Rui Tao et al., 2020; Xinwei Guo et al., 2020; Liu, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) reported the occurrence of adverse reactions.

The risk of article bias is presented in Figures 2, 3. Only one article (Mehrbani et al., 2015) explicitly mentioned the use of blindness. As other studies did not report participant/person blind or outcome measurement, both performance bias and detection bias in other studies were judged as unclear. In 23 studies (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Wei and Li, 2017; Yine and Li, 2017; Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Hu and Feng, 2018; Liu, 2018; Ma, 2018; Qi, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Zhang, 2018; Hanhua Cao et al., 2019; Li, 2019; Liu, 2019; QIi, 2019; Qing Wu et al., 2020; Rui Tao et al., 2020; Xinwei Guo et al., 2020; Yu, 2020; Bin Zhao, 2021; Lan, 2021; Liu, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021), the risk of bias was considered medium due to the lack of explicit reference to allocation concealment. In four studies (Mehrbani et al., 2015; Wei and Li, 2017; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Zhang, 2018), subjects dropped out of the study. The authors explained the reasons for the dropout, but they still considered a potential risk of bias. The judgment of unclear risk of bias was given to all studies for reporting bias, as none of the studies had study protocols and did not provide sufficient information for further assessment. Information such as the source of funding, sample size calculation, and trial registration was also insufficient to assess other potential biases in the included studies.

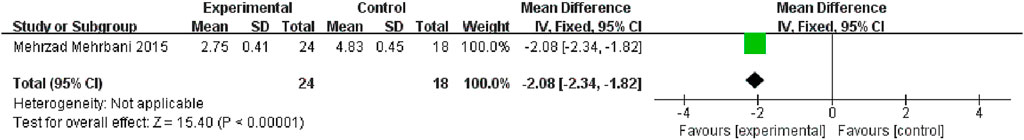

Only one study (Mehrbani et al., 2015) compared CHM with placebo; the CHM and placebo groups had a significant difference in pruritus, as determined by a fixed-effects model (n = 42, MD: −2.08; 95% CI = −2.34 to −1.82; p < .00001; Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. The results of the meta-analysis for the effect of traditional Chinese medicine and placebo on pruritus.

In four trials, the experimental groups were administered oral CHM, and the control groups were administered WM. A subgroup analysis of treatment duration showed that two studies (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Rui Tao et al., 2020) had treatment durations <4 weeks (p = .85, I2 = 0%) and two studies (Qi, 2018; Xinwei Guo et al., 2020) had treatment durations >4 weeks (p = .42, I2 = 0%). The TCM and WM groups had significant differences in pruritus, as determined by a fixed-effects model (n = 135, MD = −1.20, 95% CI = −1.63 to −.77, p < .00001; n = 194, MD = −1.80, 95% CI = −2.23 to −1.37, p < .00001; Figure 5A).

FIGURE 5. The results of the meta-analysis for the effect of traditional Chinese medicine versus Western medicine on pruritus. (A) Oral CHM treatment; (B) External treatment with CHM; (C) Oral and external treatment with CHM.

In one trial (Yu, 2020), the experimental group was administered CHM externally, and the control group was administered WM. The TCM and WM groups had significant differences in pruritus, as determined by a fixed-effects model (n = 320, MD = −.89 95% CI = −1.16 to −.62, p < .00001; Figure 5B).

Three trials compared oral and external CHM treatment with WM. A subgroup analysis of treatment duration showed that two studies (Wei and Li, 2017; Liu, 2018) had treatment durations <4 weeks (p = .87, I2 = 0%) and one study (Liu, 2019) had treatment duration >4 weeks (p < .00001). A fixed-effects model showed that the TCM and WM groups had a significant difference in pruritus after treatment (n = 210, MD = −.85, 95% CI = −1.02 to −.68, p < .00001; n = 110, MD = −2.20, 95% CI = −2.26 to −1.76, p < .00001; Figure 5C).

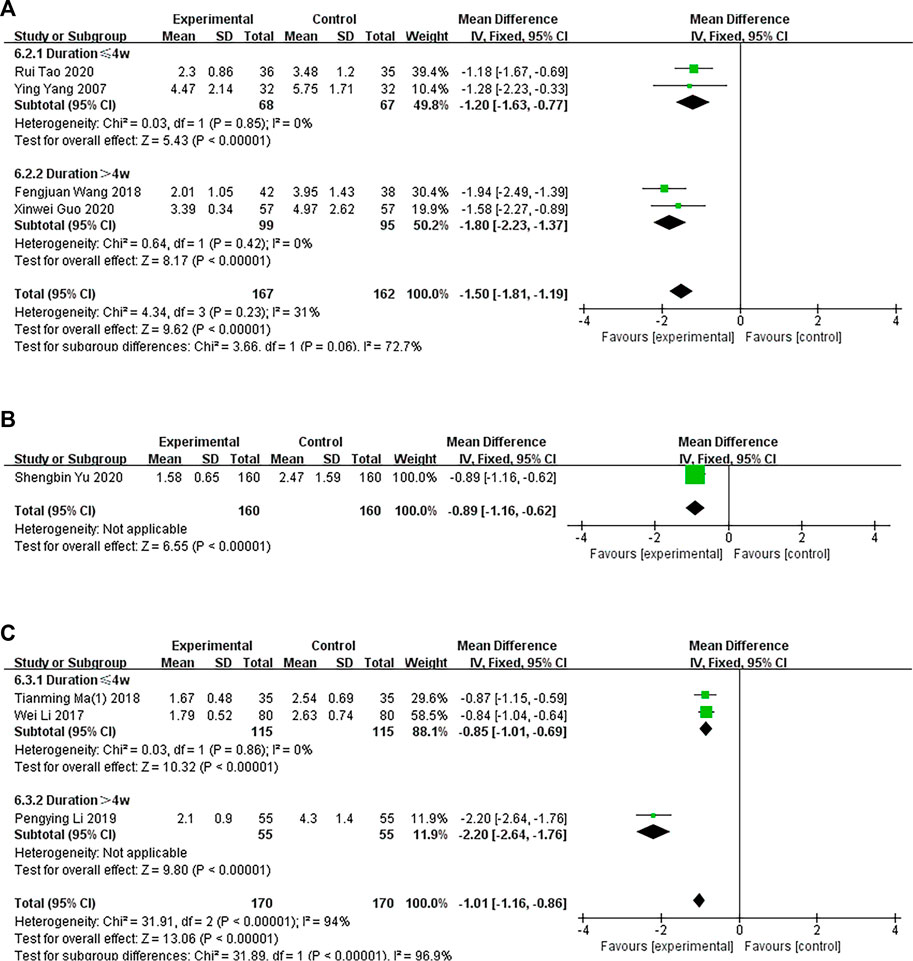

In 11 studies, the experimental group was treated with oral CHM and WM, and the control group was treated with WM. A subgroup analysis of treatment duration showed that the treatment duration was <4 weeks in seven studies (Hu and Feng, 2018; Ma, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Li, 2019; Bin Zhao, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) (p < .0001, I2 = 97%) and >4 weeks in three studies (Yine and Li, 2017; QIi, 2019; Liu, 2021) (p < .0001, I2 = 91%), suggesting some heterogeneity. A random-effects model showed a significant difference between the groups (n = 583, MD = −1.02, 95% CI = −1.49 to −.54, p < .0001; n = 354, MD = −.80, 95% CI = −1.32 to −.29, p = .002; Figure 6A). The funnel plot was asymmetrical, indicating publication bias (Supplementary Figure S1).

FIGURE 6. The results of the meta-analysis for the effect of the combination of Chinese herbal medicine and Western medicine versus Western medicine on pruritus. (A) Oral CHM treatment; (B) External treatment with CHM; (C) Oral and external treatment with CHM.

In four studies, the intervention group received external treatment with CHM and WM, whereas, the control group received WM treatment only. A subgroup analysis of treatment duration showed that the treatment duration was <4 weeks in two studies (Zhang, 2018; Lan, 2021) (p = .43, I2 = 0%) and >4 weeks in two studies (Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Hanhua Cao et al., 2019) (p < .00001, I2 = 98%), suggesting some heterogeneity. A random-effects model showed a significant difference between the groups (n = 96, MD = −1.76, 95% CI = −2.08 to −1.44, p < .00001; n = 166, MD = −1.66, 95% CI = −2.95 to −.38, p = .01; Figure 6B). However, the combined analysis showed significant statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared = 51.82; degrees of freedom = 3; I2 = 94%). The cause of heterogeneity was difficult to analyze due to the small number of studies. This might be because the scoring process is subjective.

In one study (Qing Wu et al., 2020), the experimental group was administered oral and external treatment with CHM and WM and the control group was administered WM. A fixed-effects model showed significant difference in pruritus between the groups after treatment (n = 78, MD = −1.15, 95% CI = −1.37 to −.93, p < .0000; Figure 6C).

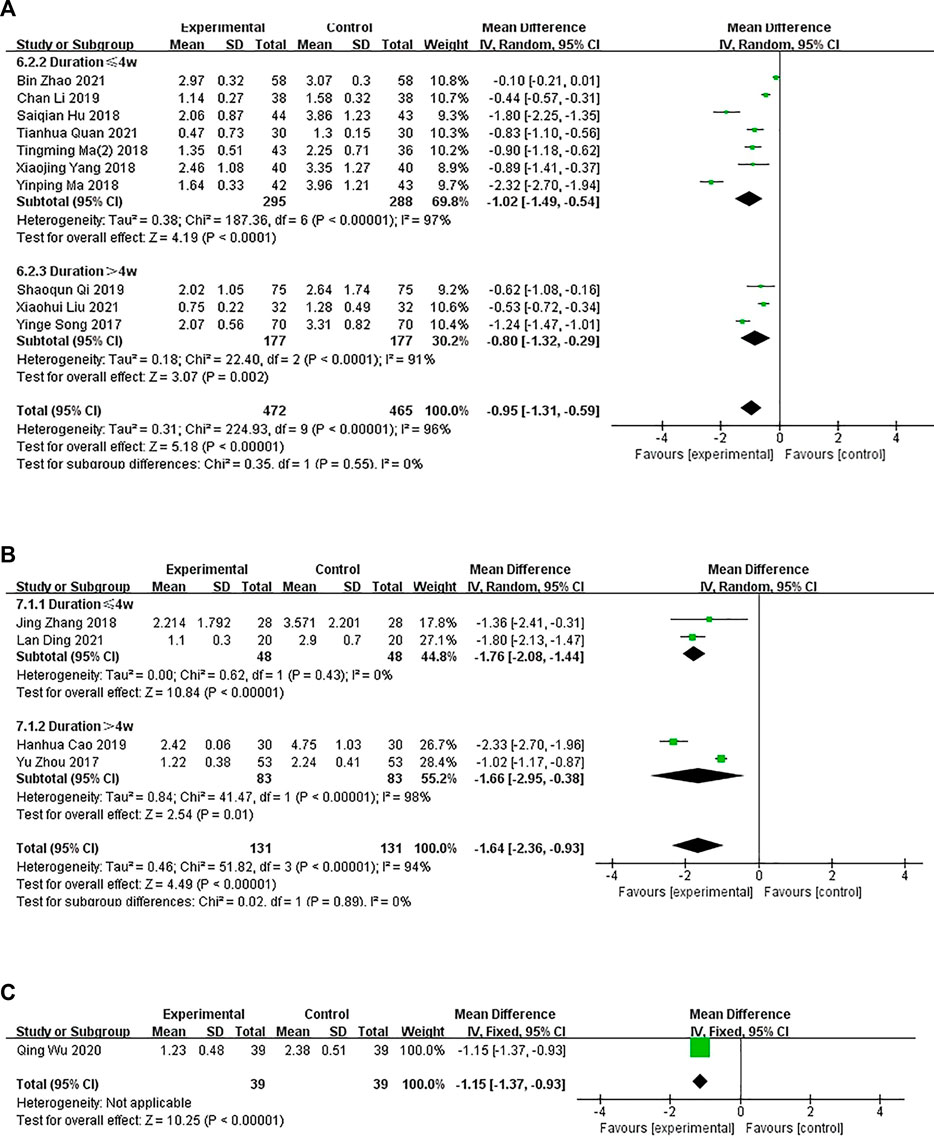

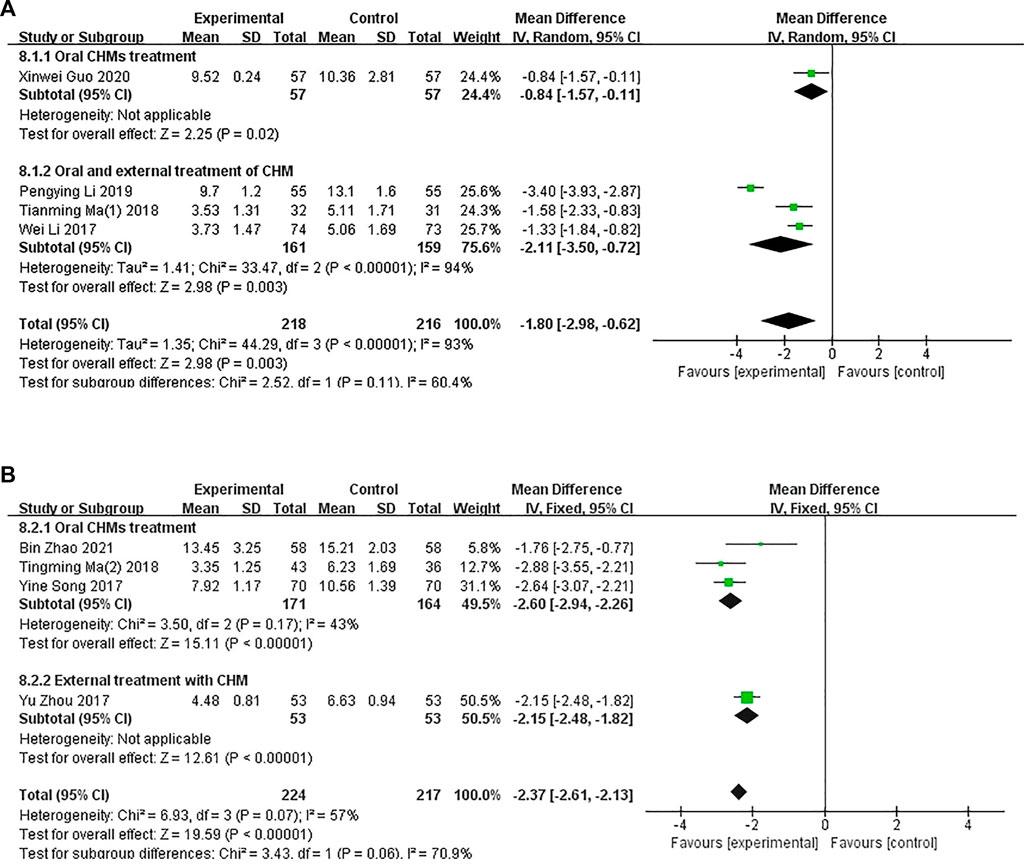

In four studies involving 434 patients, the DLQI was applied to assess the quality of life of patients with CP. A subgroup analysis showed that one (Xinwei Guo et al., 2020) study compared the administration of oral CHM with WM (p = .02), and three studies (Wei and Li, 2017; Liu, 2018; Liu, 2019) compared the administration of oral and external CHM treatment with WM (p < .00001, I2 = 94%). The pooled analysis showed that the DLQI scores of patients in the CHM groups were lower than those of patients in the control groups (MD = −1.80, 95% CI = −2.98 to −.62, p = .003 < .05; Figure 7A).

FIGURE 7. The results of the meta-analysis for the effect of Chinese herbal medicine or a combination of CHM and Western medicine (WM) versus WM on the Dermatology Life Quality Index score. (A) CHM versus WM; (B) Combination of CHM and WM versus WM.

A combination of CHM and WM was used in four studies (Figure 7B). A subgroup analysis was conducted to determine the differences in the methods of administration. Three studies (Yine and Li, 2017; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Bin Zhao, 2021) compared the administration of oral CHM with WM (p = .17, I2 = 43%), and one study (Yu Zhou et al., 2017) compared the administration of oral and external CHM treatment with WM treatment (p < .00001). The pooled analysis showed that the DLQI scores of patients in the CHM and WM groups were significantly lower than those of patients in the control groups (MD = −2.37, 95% CI = −2.61 to −2.13, p < .00001).

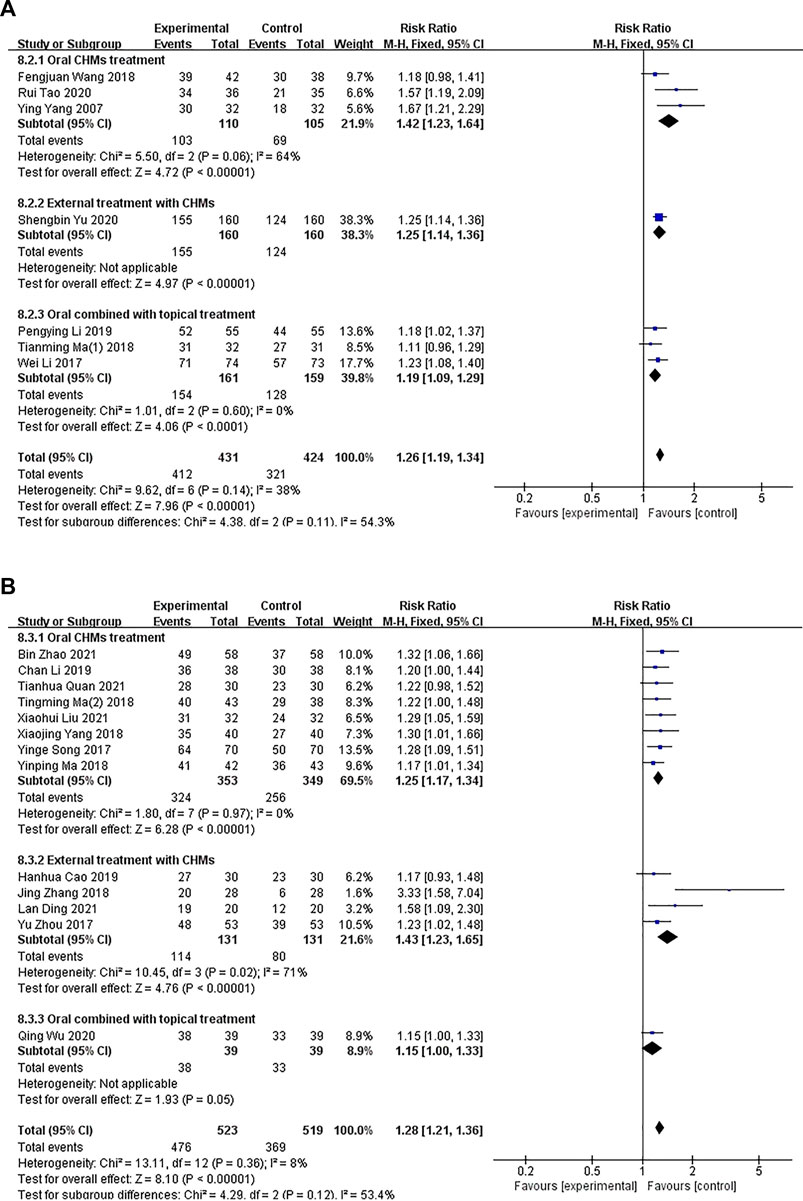

In total, 20 studies (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Wei and Li, 2017; Yine and Li, 2017; Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Liu, 2018; Ma, 2018; Qi, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Zhang, 2018; Hanhua Cao et al., 2019; Li, 2019; Liu, 2019; Qing Wu et al., 2020; Rui Tao et al., 2020; Yu, 2020; Bin Zhao, 2021; Lan, 2021; Liu, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) consisting of 1,895 patients reported the effective rate. Among them, seven studies compared CHM with WM (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Wei and Li, 2017; Liu, 2018; Qi, 2018; Liu, 2019; Rui Tao et al., 2020; Yu, 2020), and 13 studies compared a combination of CHM and WM with the same WM (Yine and Li, 2017; Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Ma, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Zhang, 2018; Hanhua Cao et al., 2019; Li, 2019; Qing Wu et al., 2020; Bin Zhao, 2021; Lan, 2021; Liu, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021).

Seven studies compared CHM with WM (p = .14, I2 = 38%), and a fixed-effects model was used to perform the meta-analysis. A subgroup analysis was conducted to determine the differences in the methods of administration. Three studies (Ying Yang et al., 2006; Qi, 2018; Rui Tao et al., 2020) compared the administration of oral CHM with WM (I2 = 64%, RR: 1.42; 95% CI = 1.23–1.64, p < .00001), one study (Yu, 2020) compared the administration of external CHM with WM (RR: 1.25; 95% CI = 1.14–1.36), p < .00001), and three studies (Wei and Li, 2017; Liu, 2018; Liu, 2019) compared the administration of oral and external CHM treatment with WM (I2 = 0%, RR: 1.19; 95% CI = 1.09–1.29; p < .0001). The results of the meta-analysis showed that the effective rate of patients in the CHM groups was higher than those of patients in the control groups (Figure 8A).

FIGURE 8. The results of the meta-analysis for the effect of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) or a combination of CHM and Western medicine (WM) versus WM on the effective rate. (A) CHM versus WM; (B) CHM versus WM.

In total, 13 studies compared a combination of CHM and WM with WM (p = .36, I2 = 8%). A fixed-effects model was used for conducting the meta-analysis. A subgroup analysis was conducted to examine the differences in the administration methods used. Eight studies (Yine and Li, 2017; Ma, 2018; Tianming Ma and Liu, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Li, 2019; Bin Zhao, 2021; Liu, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) compared the administration of oral CHM and WM with WM (I2 = 0%, RR: 1.25; 95% CI = 1.17–1.34, p < .00001), four studies (Yu Zhou et al., 2017; Zhang, 2018; Hanhua Cao et al., 2019; Lan, 2021) compared the administration of external CHM and WM with WM (I2 = 71%, RR: 1.43; 95% CI = 1.23–1.65, p < .00001), and one study (Qing Wu et al., 2020) compared the administration of oral and external CHM and WM with WM (RR: 1.15; 95% CI = 1.00–1.33; p = .05). The results of the meta-analysis showed a significant difference in the effective rate between the groups when the administration method of CHM was oral or external (p < .00001), but no significant difference was observed between the groups when a combination of oral and external methods of CHM administration was performed (p = .05; Figure 8B).

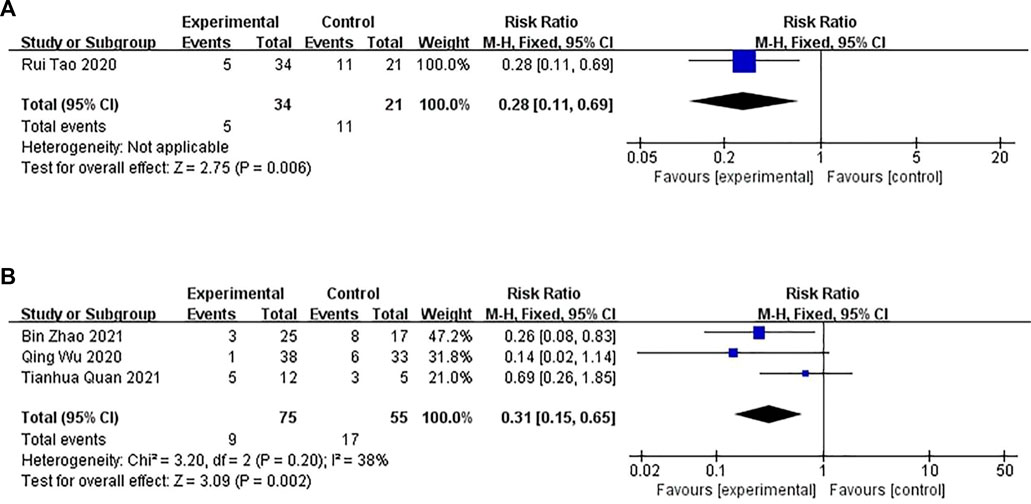

Four studies (Qing Wu et al., 2020; Rui Tao et al., 2020; Bin Zhao, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) consisting of 185 patients reported the recurrence rate. Among them, one study (Rui Tao et al., 2020) compared CHM with WM, where the patients were followed up for 3 months after treatment. Three studies compared a combination of CHM and WM with the same WM, in which, two studies (Bin Zhao, 2021; Tianhua Quan et al., 2021) had a follow-up for 1 month after treatment, and one study (Qing Wu et al., 2020) had a follow-up for 3 months after treatment.

A fixed-effects model was used for conducting the meta-analysis of the studies that compared CHM with WM. Significant differences were observed in the recurrence rate between the CHM and WM groups (n = 55, RR: .28; 95% CI = .11–.69; p = .006 < .01; Figure 9A).

FIGURE 9. The results of the meta-analysis for the effect of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) or a combination of CHM and Western medicine (WM) versus WM on the recurrence rate. (A) CHM versus WM; (B) Combination of CHM and WM versus WM.

Three studies compared the combination of CHM and WM versus WM (p = .20, I2 = 38%). A fixed-effects model was used for conducting the meta-analysis. The recurrence rate between the combination of CHM and WM groups differed significantly (n = 130, RR: .31; 95% CI = .15–.65; p = .002 < .01; Figure 9B).

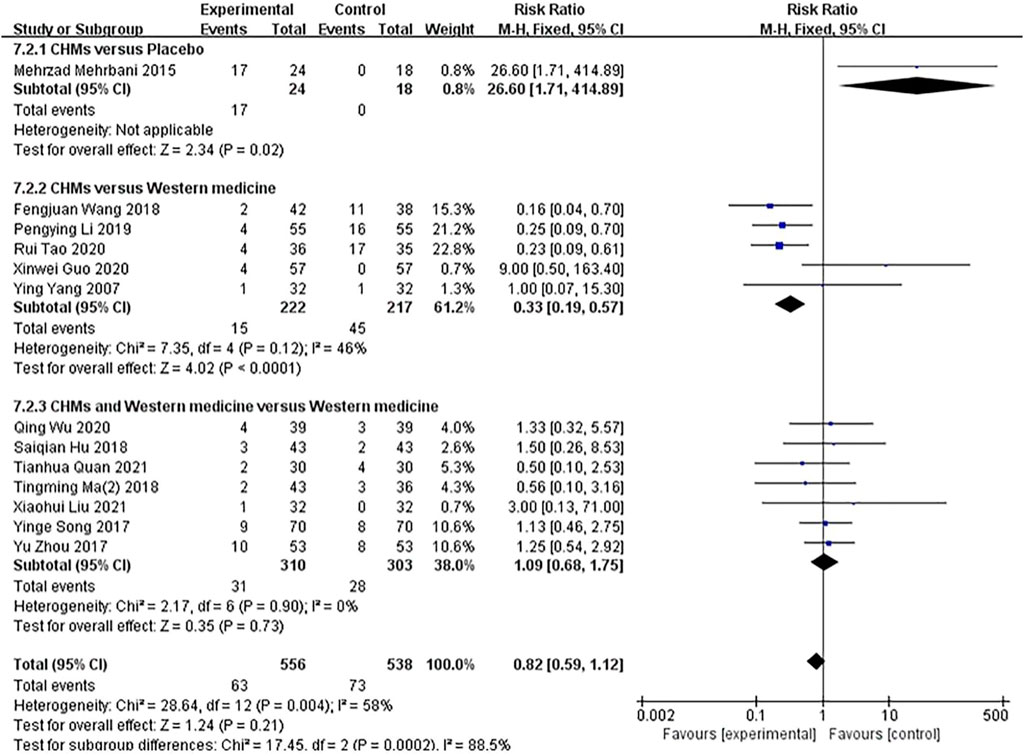

In total, 13 studies conducted with 1,094 patients reported adverse events (AEs). One study compared CHM with a placebo, and the AEs of the CHM group included anorexia and gastrointestinal discomfort (such as indigestion). Five studies compared the combination of CHM with WM. AEs in the CHM groups included dryness of the mouth, insomnia, nausea, headache, dizziness, and gastrointestinal side effects (such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, stomach discomfort, and loss of appetite). Seven studies compared the combination of CHM and WM with the same WM and reported AEs, including rash, fatigue, insomnia, gastrointestinal side effects, headache, and dizziness. No serious adverse reactions were observed.

A subgroup analysis of treatment methods showed that in one study, the incidence of adverse reactions was reported in the CHM group compared with the placebo group (p = .02), and a fixed-effects model showed no significant difference between the groups (n = 42, RR = 26.60, 95% CI = 1.71–414.89, p = .02). Five studies compared CHM with WM (p = .12, I2 = 46%), and a fixed-effects model showed that the rate of adverse effects on patients in the CHM groups was higher than that on the participants in the control groups (n = 439 RR = .33, 95% CI = .19–.57, p < 0,001). Seven studies compared the combination of CHM and WM with WM (p = .90, I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effects model showed that the incidence of adverse reactions between the groups was not significantly different (n = 613, RR = 1.09, 95% CI = .68–1.75, p = .73; Figure 10).

FIGURE 10. The results of the meta-analysis for the effect of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) or a combination of CHM and Western medicine (WM) versus WM on the rate of adverse effects.

The GRADE quality of evidence was evaluated for each outcome. The quality of evidence for pruritus, the DLQI score, and the recurrence rate were low or very low; the quality of evidence for the effective rate was high, and the quality of evidence for the rate of adverse effects was moderate (Table 4).

Several herbs were included in the 24 studies evaluated. The top 15 most frequently used herbs were used more than six times and included Divaricate Saposhniovia Root, Liquorice root, Light yellow Sophora Root, Chinese Angelica, Paeonia lactiflora, Densefruit Pittany Root-bark, Wolfiporia cocos, Fine leaf Schizonepeta Herb, Szechuan Lovage Rhizome, Rehmannia Glutinosa, Fructus Kochiae, Common Cnidium Fruit, Cicada Slough, Large head Atractylodes Rh, and Dan-Shen root (Table 5).

Many studies have shown that CHM is effective in treating CP; however, no available treatment method meets the requirements of evidence-based medicine. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses contribute to the development of evidence-based medicine and are the best source of clinical evidence [15]. We conducted a systematic review of RCTs on CHM for CP. In this systematic review, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of CHM (or a combination of CHM and WM) in treating CP. We included 24 RCTs, with 2,288 patients. The results showed that CHM (or a combination of CHM and WM) was significantly more effective than WM in improving pruritus degree, the DLQI score, the effective rate, and the recurrence rate of CP.

We found that the treatment of CP by administering CHM significantly improved the degree of pruritus compared to the placebo. CHM had a more significant effect than WM on the improvement of the degree of pruritus, the DLQI score, and the effective rate in CP. Subgroup analysis was conducted on the groups of participants who were treated via different drug administration methods and treatment courses. The results showed that oral administration was the most effective, followed by a combination of oral and external treatment. The effect of the treatment on reducing itching improved with the increase in the duration of treatment. These results showed that performing monotherapy with CHM can improve the symptoms of CP patients. Regarding the comparison of the combination of CHM and WM with WM, the meta-analysis showed that CHM combined with WM in CP treatment is significantly more effective in improving the degree of pruritus, the DLQI score, the effective rate, and the recurrence rate. The combination of CHM and WM was the most effective when topically applied. These results indicated that CHM as an adjunctive therapy can improve the symptoms of CP patients.

Regarding the effect of the patient recurrence rate, the disease recurrence rate in the CHM and combination of CHM and WM treatment groups was lower than that in the WM treatment group. Thirteen studies that investigated the safety of CHM treatment reported AEs, including dryness of the mouth, insomnia, nausea, dizziness, rash, fatigue, gastrointestinal side effects, headache, and dizziness. The results of the meta-analysis for the effect of the AEs showed no significant difference in the incidence of AEs between the CHM and placebo groups, between the CHM and WM groups, and between the combination of CHM and WM and WM-only groups. This indicated that CHM might be recommended for treating patients with CP.

This meta-analysis revealed that CHM is safe and might be used for monotherapy or adjuvant therapy to improve pruritus and the DLQI score of patients with CP. A descriptive analysis based on included RCTs indicated a great diversity in the detailed composition of the herbs in the CHM prescribed for patients with CP. We found that among the CHM included in the studies, Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz. ex Ledeb.) Schischk, Glycyrrhiza glabra L, Sophora flavescens Aiton, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Paeonia lactiflora Pall, Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz, Smilax glabra Roxb, Sesamum indicum L, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong,” Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC, Bassia scoparia L.) A.J. Scott, Cnidium monnieri L.) Cusson, Tabernaemontana divaricata L.) R. Br. ex Roem. and Schult, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge were frequently used as the most effective prescriptions for treating chronic itching. These findings should be further considered when formulating commonly used CHM for CP treatment.

This study had several limitations: (Rajagopalan et al., 2017) The number and sample size of the included studies were relatively small, which affected the reliability of the conclusions (Villa-Arango et al., 2019) Among the included studies, 11 studies did not report allocation concealment, only one study conducted blinded trials, and the trials in the other studies were not blinded; thus, a certain risk of bias existed (Ständer et al., 2007) The evaluation standard of the degree of itching was single and highly subjective, and the risk of deviation was high (Weisshaar et al., 2019) The formulation composition, dosage, administration method, and CHM treatment duration in RCTs varied widely across studies. Clinical heterogeneity compromised the validity of our findings. The publication bias caused by all the studies being published in China might have partly exaggerated the efficacy of CHM.

Using CHM for monotherapy or adjuvant therapy is effective in treating CP, and this review provides existing evidence that might help to shape the design of future trials. Although double‒blinded trials may be difficult due to the nature of CHM treatment, study investigators should consider alternative strategies to minimize the risk of performance bias. The trials could have also at least blinded the individuals who assessed the trial outcomes. After incorporating these methodologic precautions, study investigators should acknowledge the potential biases arising from the lack of blinding, and address them appropriately in the limitations of their study. For example, the use of the CONSORT 2017 Chinese Herbal Prescription Expansion (Cheng et al., 2017) to report the results of RCTs involving herbal interventions, the use of the CONSORT 2010 Statement (Piaggio et al., 2012), and the RCT design protocol used to study CHM [18] to establish and report RCTs for CHM treatment. Although the findings of this systematic review suggested that the use of CHM treatment might be relatively safe in patients with CP, further studies are needed to confirm our findings. Bian et al. (Bian et al., 2010) established a standard format for reporting adverse drug reactions in CHM, which might improve the ways to report adverse drug reactions. Regardless, both study investigators and authors should ensure a strict methodology and proper reporting, to reduce potential biases in trials evaluating the effectiveness of herbal medicine for the treatment of CP. Additionally, the effectiveness of TCM depends on accurately differentiating and treating the syndrome. Therefore, drug prescriptions must be distinguished based on different syndromes of diseases. When evaluating the therapeutic effects of CHM treatment, syndrome differentiation and treatment should be accurately conducted, and individualized TCM prescriptions should be formulated to treat specific diseases. For example, a study (Bensoussan et al., 1998) showed that the administration of personalized CHM for treating irritable bowel syndrome had better effects than a generic hypnotic prescription. Therefore, appropriate drugs prepared from common herbs should be administered in clinical practice based on specific disease syndromes to improve the efficacy of CHM in treating CP.

This meta-analysis and systematic review of 24 RCTs consisted of 2,288 patients. Low certainty evidence suggested that CHM used with or without WM, compared with WM, might have significantly better effects on alleviating pruritus, increasing DLQI scores, and improving the effective rate in patients with CP in clinical practice. Administering CHM did not increase the risk of adverse events. However, more high-quality RCTs are needed to confirm the effectiveness and adverse events of CHM in the treatment of CP.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

JW designed the study. JW, YC, XY, JH, YX, WW, and XW performed the study, including literature search, data selection and extraction, quality assessment, and data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors of this review were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973857), Key Laboratory of Sports Medicine in Sichuan Province, and Key Laboratory of the State General Administration of Sports (2022-A041), the Sichuan Provincial Central Government Guided Local Science and Technology Development Project 2022ZYD0103.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer QF declared a shared affiliation, with no collaboration, with one of the authors YX to the handling editor at the time of the review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022.1029949/full#supplementary-material

CP, chronic pruritus; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, risk ratio; MD, mean difference; VAS, visual analogue scale; CHM, Chinese herbal medicine; WM, conventional western medicine treatment; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; AE, adverse event; AD, atopic dermatitis; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment; Development, and Evaluation; CI, confidence interval; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

Andrade, A., Kuah, C. Y., Martin-Lopez, J. E., Chua, S., Shpadaruk, V., Sanclemente, G., et al. (2020). Interventions for chronic pruritus of unknown origin. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1 (1), 013128. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013128.pub2

Bedi, M. K., and Shenefelt, P. D. (2002). Herbal therapy in dermatology. Arch. Dermatol 138 (2), 232–242. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.2.232

Bensoussan, A., Talley, N. J., Hing, M., Menzies, R., Guo, A., Ngu, M., et al. (1998). Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with Chinese herbal medicine: A randomized controlled trial. Jama 280 (18), 1585–1589. doi:10.1001/jama.280.18.1585

Bian, Z. X., Tian, H. Y., Gao, L., Shang, H. C., Wu, T. X., Li, Y. P., et al. (2010). Improving reporting of adverse events and adverse drug reactions following injections of Chinese materia medica. J. Evid. Based Med. 3 (1), 5–10. doi:10.1111/j.1756-5391.2010.01055.x

Bin Zhao, L. L. (2021). Clinical effect of self-made Xiaoxun decoction combined with desloratadine citrate disodium tablets in the treatment of chronic urticaria. Clin. Med. Res. Pract. 6 (24), 148–150. (in Chinese). doi:10.19347/j.cnki.2096.1413.202124049

Cheng, C. W., Wu, T. X., Shang, H. C., Li, Y. P., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., et al. (2017). CONSORT extension for Chinese herbal medicine formulas 2017: Recommendations, explanation, and elaboration. Ann. Intern Med. 167 (2), 112–121. doi:10.7326/m16-2977

Dalgard, F. J., Svensson, Å., Halvorsen, J. A., Gieler, U., Schut, C., Tomas-Aragones, L., et al. (2020). Itch and mental health in dermatological patients across europe: A cross-sectional study in 13 countries. J. Invest. Dermatol 140 (3), 568–573. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.034

Finlay, A. Y., and Khan, G. K. (1994). Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin. Exp. Dermatol 19 (3), 210–216. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x

Furue, M., Ebata, T., Ikoma, A., Takeuchi, S., Kataoka, Y., Takamori, K., et al. (2013). Verbalizing extremes of the visual analogue scale for pruritus: A consensus statement. Acta Derm. Venereol. 93 (2), 214–215. doi:10.2340/00015555-1446

Hanhua Cao, Y. X., Xu, Jingjing, Longju, M., and Ma, Jinqiang (2019). Chinese herbal fumigation combined with gabapentin and hemoperfusion has effect on pruritus in hemodialysis patients. J. NEW Chin. Med. 51 (10), 211–213. (in Chinese). doi:10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2019.10.060

Hay, R. J., Johns, N. E., Williams, H. C., Bolliger, I. W., Dellavalle, R. P., Margolis, D. J., et al. (2014). The global burden of skin disease in 2010: An analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J. Invest. Dermatol 134 (6), 1527–1534. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.446

Hu, S., and Feng, Y. (2018). Clinical observation on 44 cases of senile skin pruritus treated by traditional Chinese medicine. Dermatology Venereol. 40 (02), 239–240. (in Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002.1310.2018.02.051

Kretzmer, G. E., Gelkopf, M., Kretzmer, G., and Melamed, Y. (2008). Idiopathic pruritus in psychiatric inpatients: An explorative study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 30 (4), 344–348. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.03.006

Lan, Ding J. T. (2021). Effect of self - made yangxue qufeng external washing prescription on skin pruritus of blood deficiency and wind dryness type in hemodialysis patients. Health World 20, 146–147. (in Chinese).

Li, C. (2019). Clinical observation of xiaoyang decoction combined with loratadine in the treatment of chronic urticaria. J. Pract. TRADITIONAL Chin. Med. 35 (05), 560–561. (in Chinese).

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Bmj 339, 2700. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2700

Liu, P. L. L. F. H. (2019). Therapeutic effect of traditional Chinese medicine No. 2 prescription combined with jianpi Jiedu decoction on spleen deficiency and spleen syndrome of common spleen and expression of T lymphocytes in peripheral blood. Chin. ARCHIVES TRADITIONAL Chin. Med. 37 (11), 2609–2613. (in Chinese). doi:10.13193/j.issn.1673.7717.2019.11.010

Liu, T. M. X. H. G. (2018). Clinical study of Chinese herbal washing externally and drinking internally on blood deficiency - wind dryness syndrome of neurodermatitis. Hebei J. TCM 40 (3), 344–347. (in Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002.2619.2018.03.005

Liu, X. (2021). Effects of Danggui Sini decoction on psoriasis patients with blood Deficiency and windcold type. Med. J. Chin. People's Health 33 (21), 90–92. (in Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.16720369.2021.21.033

Lu, P. H., Tai, Y. C., Yu, M. C., Lin, I. H., and Kuo, K. L. (2021). Western and complementary alternative medicine treatment of uremic pruritus: A literature review. Tzu Chi Med. J. 33 (4), 350. doi:10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_151_20

Ma, T., Chai, Y., Li, S., Sun, X., Wang, Y., Xu, R., et al. (2020). Efficacy and safety of Qinzhuliangxue decoction for treating atopic eczema: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Palliat. Med. 9 (3), 870–882. doi:10.21037/apm.2020.04.17

Ma, Y. (2018). Clinical effect of self-made yangxue zhiyang decoction combined with compound flumetasone ointment in treating chronic eczema and its effect on the levels of immune response factors. China Pharm. 27 (07), 42. (in Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.10064931.2018.07.013

Matterne, U., Apfelbacher, C. J., Vogelgsang, L., Loerbroks, A., and Weisshaar, E. (2013). Incidence and determinants of chronic pruritus: A population-based cohort study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 93 (5), 532–537. doi:10.2340/00015555-1572

Matterne, U., Apfelbacher, C. J., Loerbroks, A., Schwarzer, T., Büttner, M., Ofenloch, R., et al. (2011). Prevalence, correlates and characteristics of chronic pruritus: A population-based cross-sectional study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 91 (6), 674–679. doi:10.2340/00015555-1159

Mehrbani, M., Choopani, R., Fekri, A., Mehrabani, M., Mosaddegh, M., and Mehrabani, M. (2015). The efficacy of whey associated with dodder seed extract on moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Ethnopharmacol. 172, 325–332. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.003

Olek-Hrab, K., Hrab, M., Szyfter-Harris, J., and Adamski, Z. (2016). Pruritus in selected dermatoses. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 20 (17), 3628–3641.

Pakfetrat, M., Basiri, F., Malekmakan, L., and Roozbeh, J. (2014). Effects of turmeric on uremic pruritus in end stage renal disease patients: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. J. Nephrol. 27 (2), 203–207. doi:10.1007/s40620-014-0039-2

Pereira, M. P., Mühl, S., Pogatzki-Zahn, E. M., Agelopoulos, K., and Ständer, S. (2016). Intraepidermal nerve fiber density: Diagnostic and therapeutic relevance in the management of chronic pruritus: A review. Dermatol Ther. (Heidelb) 6 (4), 509–517. doi:10.1007/s13555-016-0146-1

Piaggio, G., Elbourne, D. R., Pocock, S. J., Evans, S. J., and Altman, D. G. (2012). Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: Extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. Jama 308 (24), 2594–2604. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.87802

Qi, F. W. Z. (2018). Effect of using jianpi qushi decoction in the treatment of spleen deficiency and dampness accumulation type eczema and its effect on immune function. J. Sichuan Traditional Chin. Med. 36 (06), 178–181. (in Chinese).

Qii, S. (2019). Analysis of therapeutic effect on eczema by using jianpi huashi decoction combined with hydrocortisone butyrate cream. Chin. J. Aesthetic Med. 28 (07), 127–130. (in Chinese). doi:10.15909/j.cnki.cn611347/r.003167

Qing Wu, H. J., Wang, Xingxing, Ma, Xiaohong, and Yan, Xiaoning (2020). Clinical effect of oral administration and external application of Qingre Liangxue decoction in the treatm entofpsoriasis. Clin. Med. Res. Pract. 5 (29), 142–144. (in Chinese). doi:10.19347/j.cnki.20961413.202029053

Rajagopalan, M., Saraswat, A., Godse, K., Shankar, D. S., Kandhari, S., Shenoi, S. D., et al. (2017). Diagnosis and management of chronic pruritus: An expert consensus review. Indian J. Dermatol 62 (1), 7–17. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.198036

Rui Tao, S. Y., Lu, You, Lan, Zhai, Wang, Yingli, and Zhao, Lei (2020). Clinical study on jiangtang huoxue prescription combined with xiaofeng powder in treatment of diabetes with chronic eczema. Chin. J. Inf. TCM 27 (06), 34–37. (in Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.10055304.202001224

Schneider, G., Ständer, S., Kahnert, S., Pereira, M. P., Mess, C., Huck, V., et al. (2022). Biological and psychosocial factors associated with the persistence of pruritus symptoms: Protocol for a prospective, exploratory observational study in Germany (individual project of the interdisciplinary SOMACROSS research unit [RU 5211]). BMJ Open 12 (7), e060811. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-060811

Schneider, G., Driesch, G., Heuft, G., Evers, S., Luger, T. A., and Ständer, S. (2006). Psychosomatic cofactors and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic itch. Clin. Exp. Dermatol 31 (6), 762–767. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02211.x

Shive, M., Linos, E., Berger, T., Wehner, M., and Chren, M. M. (2013). Itch as a patient-reported symptom in ambulatory care visits in the United States. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 69 (4), 550. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.029

Ständer, S., Weisshaar, E., Mettang, T., Szepietowski, J. C., Carstens, E., Ikoma, A., et al. (2007). Clinical classification of itch: A position paper of the international forum for the study of itch. Acta Derm. Venereol. 87 (4), 291–294. doi:10.2340/00015555-0305

Steinke, S., Zeidler, C., Riepe, C., Bruland, P., Soto-Rey, I., Storck, M., et al. (2018). Humanistic burden of chronic pruritus in patients with inflammatory dermatoses: Results of the European academy of dermatology and venereology network on assessment of severity and burden of pruritus (PruNet) cross-sectional trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 79 (3), 457–463. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.044

Stumpf, A., Schneider, G., and Ständer, S. (2018). Psychosomatic and psychiatric disorders and psychologic factors in pruritus. Clin. Dermatol 36 (6), 704–708. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.015

Szepietowski, J. C., Reich, A., and Wiśnicka, B. (2002). Itching in patients suffering from psoriasis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 10 (4), 221–226.

Szepietowski, J. C., Reich, A., and Wisnicka, B. (2004). Pruritus and psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol 151 (6), 1284. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06299.x

Tianhua Quan, X. L., Chen, Yue, Yu, Yahua, and Liu, Huanqiang (2021). Clinical effect observation of Pingwei Xiaozhen Decoction combined with olopatadine hydrochloride tablets in the treatment of chronic urticaria with syndrome of damp-heat in hydrochloride tablets in the treatment of chronic urticaria with syndrome of damp-heat in stomach and intestinestomach and intestine. Jilin J. Chin. Med. 41 (07), 841–845. (in Chinese). doi:10.13463/j.cnki.jlzyy.2021.07.001

Tianming Ma, X. H., and Liu, Guijun (2018). Clinical observation of kushen fafeng pill in treating adult mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. Hebei J. TCM 40 (11), 1671–1674. (in Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002.2619.2018.11.016

Twycross, R., Greaves, M. W., Handwerker, H., Jones, E. A., Libretto, S. E., Szepietowski, J. C., et al. (2003). Itch: Scratching more than the surface. Qjm 96 (1), 7–26. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg002

Villa-Arango, A. M., Velásquez-Lopera, M. M., and Cardona, R. (2019). Chronic pruritus. Rev. Alerg. Mex. 66 (1), 85–98. doi:10.29262/ram.v66i1.345

Wei, L. I. F. Z., and Li, Yuanwen (2017). Clinical effect of qingshi zhiyang ointment combined with modified xiaofeng zhiyang decoction in treating neurodermatitis. Chin. J. Exp. Traditional Med. Formulae 23 (21), 194–199. (in Chinese). doi:10.13422/j.cnki.syfjx.2017210194

Weiss, M., Mettang, T., Tschulena, U., and Weisshaar, E. (2016). Health-related quality of life in haemodialysis patients suffering from chronic itch: Results from GEHIS (German epidemiology haemodialysis itch study). Qual. Life Res. 25 (12), 3097–3106. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1340-4

Weisshaar, E., Szepietowski, J. C., Dalgard, F. J., Garcovich, S., Gieler, U., Giménez-Arnau, A. M., et al. (2019). European S2k guideline on chronic pruritus. Acta Derm. Venereol. 99 (5), 469–506. doi:10.2340/00015555-3164

Xinwei Guo, G. L., Li, Ping, Wang, Yan, and Sun, Liyun (2020). Clinical observation of Modified Chushi Weiling Decoction in the treatment of atopic derm atitis with spleen deficiency and dampness deposition syndrome. Chin. J. Traditional Chin. Med. 35 (01), 458–460. (in Chinese).

Xu, Y., Chen, S., Zhang, L., Chen, G., and Chen, J. (2021). The anti-inflammatory and anti-pruritus mechanisms of huanglian Jiedu decoction in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 735295. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.735295

Xue, W., Zhao, Y., Yuan, M., and Zhao, Z. (2019). Chinese herbal bath therapy for the treatment of uremic pruritus: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 19 (1), 103. doi:10.1186/s12906-019-2513-9

Yang, Xiaojing, Zhu, Youjin, Su, Hua, Ma, Lei, Zhou, Xiangzhao, and An, Guozhi (2018). Effect of white tiger soup combined with desloratadine and dexamethasone in the treatment of contact allergic dermatitis. Mod. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 27 (03), 253–255+9. (in Chinese).

Yine, Song, and Li, Feng (2017). Clinical effect of Yangxue Tongluo decoction in the treatment of plaque psoriasis and its influence on the levels of IL-6, TNF-α and VEGF. Mod. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 26 (21), 2298–2301. (in Chinese).

Ying Yang, Y. W., Yang, Yufeng, Guo, Zhibin, and Zhang, Shangbin (2006). Effect of jianpi zhiyang granule on serum IgE level in patients with atopic dermatitis. Chin. ARCHIVES TRADITIONAL Chin. Med. 24 (3), 472–473. (in Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672.0709.2007.03.002

Yu, S. (2020). Observation on the curative effect of traditional Chinese medicine fumigation in the Treatment of adult Chronic Eczema. Dermatology Venereol. 42 (01), 109–111. (in Chinese).

Yu Zhou, M. Y., Bai, Xinping, Gao, Ying, Han, Han, and Guan, Huiwen (2017). NB-UVB phototherapy combined with decoction bath of self-made prescription for cooling blood and relieving itching for psoriasis vulgaris and its effect on hemorheolog. Mod. J. Integr. Traditional Chin. West. Med. 26 (27), 3023–3026. (in Chinese).

Keywords: Chinese herbal medicine (CHM), chronic pruritus (CP), pruritus degree, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation: Wang J, Chen Y, Yang X, Huang J, Xu Y, Wei W and Wu X (2023) Efficacy and safety of Chinese herbal medicine in the treatment of chronic pruritus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Pharmacol. 13:1029949. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1029949

Received: 28 August 2022; Accepted: 29 December 2022;

Published: 12 January 2023.

Edited by:

David Adeiza Otohinoyi, Louisiana State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Qinwei Fu, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Wang, Chen, Yang, Huang, Xu, Wei and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xianbo Wu, Y2R1dGNtd3VAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.