94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol., 23 September 2022

Sec. Neuropharmacology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1017129

This article is part of the Research TopicInterplay Between Chronic Pain and Affective-Cognitive Alterations: Shared Neural Mechanisms, Circuits, and TreatmentView all 10 articles

Background: Fibromyalgia is a chronic neurological condition characterized by widespread pain. The effectiveness of current pharmacological treatments is limited. However, several medications have been approved for phase IV trials in order to evaluate them.

Aim: To identify and provide details of drugs that have been tested in completed phase IV clinical trials for fibromyalgia management in adults, including the primary endpoints and treatment outcomes. This article was submitted to Neuropharmacology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pharmacology.

Method: Publicly available and relevant phase IV trials registered at ClinicalTrials.gov were analyzed. The uses of the trialed drugs for fibromyalgia were reviewed.

Results: As of 8 August 2022, a total of 1,263 phase IV clinical trials were identified, of which 121 were related to fibromyalgia. From these, 10 clinical trials met the inclusion criteria for the current study. The drugs used in phase IV trials are milnacipran, duloxetine, pregabalin, a combination of tramadol and acetaminophen, and armodafinil. The effectiveness of the current pharmacological treatments is apparently limited.

Conclusion: Due to its complexity and association with other functional pain syndromes, treatment options for fibromyalgia only are limited and they are designed to alleviate the symptoms rather than to alter the pathological pathway of the condition itself. Pain management specialists have numerous pharmacologic options available for the management of fibromyalgia.

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a complex condition affecting a person’s sensory processing system and it has a significant morbidity rate (Clauw, 2009; Sumpton and Moulin, 2014). Like other functional pain syndromes, fibromyalgia shows symptoms without pathologic findings. It is characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain accompanied by anxiety, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and sleep disruption (Neumann and Buskila, 2003; Arnold et al., 2008; Häuser et al., 2015; Andrade et al., 2020). Other symptoms associated with fibromyalgia include tension headaches, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, irritable bowel syndrome, and depression; these ultimately lead to a decline in patients’ quality of life (Silver and Wallace, 2002; Ayouni et al., 2019; Santos et al., 2019). Some patients report morning stiffness and gastrointestinal irritation. Several asymptomatic conditions can also develop in fibromyalgia patients, such as osteoarthritis, hyperparathyroidism, degenerative disk disease, and calcifications (Maria De Freitas Trindade Costa et al., 2016; Maugars et al., 2021). The condition is reported in more women than in men (Yunus, 2001).

Clinically, the presence of fibromyalgia has been linked to an increased response to almost any type of stimulus, including hot, cold, electrical stimulation, photosensitivity, and sometimes the brightness of light or the volume of auditory tones. These all contribute to enhanced pain sensitivity and they induce persistent pain (Geisser et al., 2008; Becker and Schweinhardt, 2012; Martenson et al., 2016). The widespread pain experienced by individuals with fibromyalgia has been attributed to primarily central mechanisms such as central sensitization at the spinal level and abnormal pain processing in the brain (Desmeules et al., 2003; Cagnie et al., 2014). Although the exact cause of fibromyalgia is not fully understood, biological factors, mechanical/physical trauma or injury, genetic factors, and psychosocial stressors have been held responsible for the painful condition (Sommer et al., 2008; Amsterdam and Buskila, 2021). The disease is well known for the abnormal pain sensitivity that it causes, along with abnormal neurotransmitter levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), abnormal activation of cerebral pain-processing areas, and abnormal peripheral pain and sensory thresholds (Larson et al., 2000; Staud and Domingo, 2001; Staud, 2002). These could be treatment targets for some drugs.

Despite its pathophysiological complexity, fibromyalgia may present with several comorbidities that worsen the sensation. Interestingly, the factors contributing to the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia may also exist with other functional pain syndromes such as functional abdominal pain syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and TMJ disorder (Shaver, 2008; Yunus, 2012; Johnson and Makai, 2018). This co-existence leads to further complexity for clinicians.

Research advances are increasingly focusing on the development of analgesics and pain management medications that can be used for fibromyalgia. In this context, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, norepinephrine inhibitors, skeletal muscle relaxants, anti-epileptic agents, and anesthetics have been mainly investigated (Sarzi-Puttini et al., 2008; Häuser et al., 2009). Other targets for pain alleviation include the inhibition of excitatory neurotransmitters, substance P, and glutamate (Sarchielli et al., 2007; Owen, 2008; Guymer and Littlejohn, 2021). The aim of treatment for fibromyalgia is often to reduce pain-related symptoms. However, there is no specific pathophysiological therapeutic target.

Fibromyalgia is a chronic, life-long condition, and it has no known etiology and no single cure. The multidisciplinary approach with medications, physiotherapy, psychologic, and other modalities provides the best chance of improved outcomes without promoting polypharmacy (Menzies et al., 2017; Oliveira Júnior and Ramos, 2019). Caution is advised when designing a treatment plan in fibromyalgia.

A considerable amount of literature has listed different pharmacological treatments used as adjunct medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, e.g., fluoxetine (Lawson, 2002; Häuser et al., 2015; Walitt et al., 2015); skeletal muscle relaxants, e.g., cyclobenzaprine (Tofferi et al., 2004); tramadol (Russell et al., 2000; Goldenberg et al., 2004); clonazepam (Corrigan et al., 2012); lidocaine (Abeles et al., 2007). Moreover, caffeine is used as a non-selective antagonism of adenosine receptors which reduce pain processing (Scott et al., 2017). Most of the above-mentioned drugs are used to induce sleep, reduce the symptoms of depression and anxiety and/or minimize fatigue. However, drugs that are US FDA approved specifically for fibromyalgia include milnacipran, duloxetine, and pregabalin.

This review focuses on medications that have been tested in phase IV clinical trials only. It identifies and summarizes the drugs that have been trialed for fibromyalgia and it provides an overview of phase IV clinical trials that assess a pharmacological treatment of fibromyalgia in adults. The drugs found to be used in phase IV trials on fibromyalgia are milnacipran, duloxetine, pregabalin, the combination of tramadol and acetaminophen, and armodafinil.

Several studies have revealed that not only pharmacological treatments are available for fibromyalgia, but that non-pharmacological options could also help patients with this condition. For patients with chronic pain, a number of non-pharmacological options, including physical and aerobic exercises and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), have shown promising results as standalone, adjunctive treatments (Hassett and Williams, 2011; Nüesch et al., 2013). A study conducted by Bernik et al. (2013) concluded that pharmacotherapy and CBT therapy should preferably be provided to all patients with fibromyalgia.

Moreover, studies suggest that psychological support is essential for patients with fibromyalgia due to the many negative emotions that can accompany the condition. Psychological treatments include mindfulness meditation, stress management and coping mechanisms, e.g., sleep hygiene and relaxation techniques improved pain perception and minimized pain symptoms (Hassett and Gevirtz, 2009; Aman et al., 2018). Indeed, complementary treatments including frequent movement, electroacupuncture, acupuncture, and chiropractor therapy are effective as adjuvant therapies to all patients with fibromyalgia (Sarac and Gur, 2005; Zheng and Faber, 2005; Martin et al., 2006; Ablin et al., 2013).

ClinicalTrials.gov was searched to identify trials relevant to this review. ClinicalTrials.gov is an online database, effectively a public registry of clinical trials conducted in 221 countries; it contains information about medical studies with human volunteers. This review evaluated drugs used in fibromyalgia and it examined entries related to pharmacological fibromyalgia studies. See the following section for the parameters used in the search. Articles were screened independently by two reviewers and assessed for risk of bias. Data from 1,263 clinical trials were downloaded from ClinicalTrials.gov on 08/08/2022. After excluding trials that involved the treatment of other complications or were not at phase IV, 10 clinical trials remained as eligible for the review. The inclusion criteria were: 1) primary focus on fibromyalgia; 2) completed studies; 3) for patients of adult age (18–64 years old), and 4) results were available.

The data were extracted manually and downloaded from ClinicalTrials.gov, covering the following:

• Interventions: Details of interventional (clinical trial).

• Conditions: The medical condition treated was selected as “Fibromyalgia.”

• Trial design: Phase IV only.

The trials’ results were extracted manually from the results reported in the registry. The primary outcomes, number of participants, timeframe and results were collected.

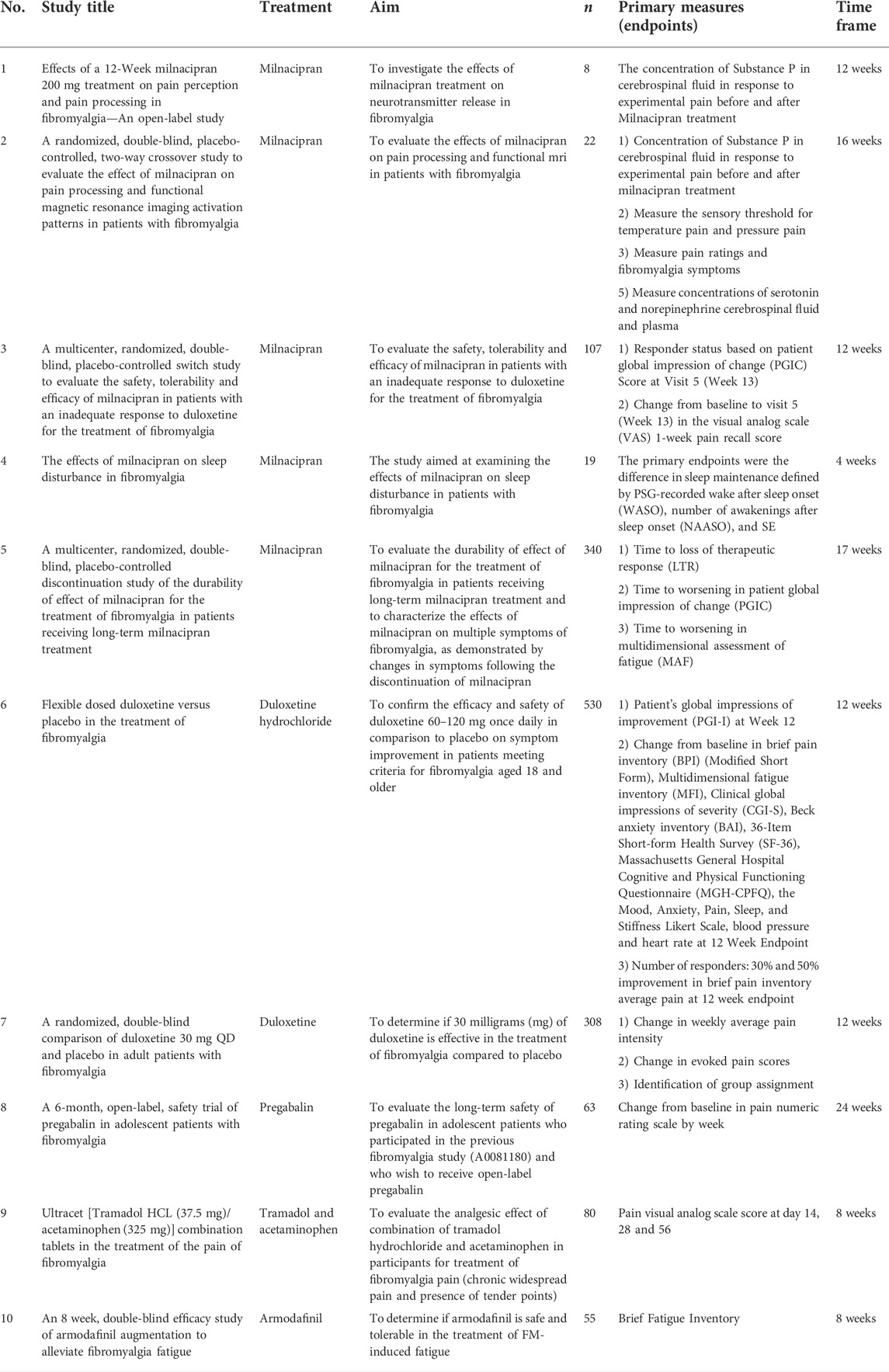

The drugs used in the phase IV trials are milnacipran, duloxetine, pregabalin, a combination of tramadol and acetaminophen, and armodafinil. Interestingly, five out of the ten clinical trials were used to evaluate the role of milnacipran in fibromyalgia. The official title of the trial, the intervention, aims, primary measures (endpoints) and timeframe are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1. (Data from https://clinicaltrials.gov, updated on 08-08-2022).

Milnacipran is a non-tricyclic compound that inhibits the re-uptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine (Yoshida et al., 2004; Häuser et al., 2015). As a result, serotonin and norepinephrine levels are increased and disorders resulting from a lack of these neurotransmitters are improved. This leads to a reduction in symptoms, including pain, fatigue, and cognitive deficits. A three-fold greater selectivity for norepinephrine inhibition is found with milnacipran than for serotonin inhibition (Palmer et al., 2010; Raouf et al., 2017). The drug is approved by the US Food and Drug Authority (FDA) exclusively for fibromyalgia. Milnacipran is believed to inhibit some excitatory neurotransmitters such as substance P, which may result in the reduction of pain severity. It is recommended for the treatment of various chronic pain syndromes (Elliott et al., 2009; Kyle et al., 2010). It can also be effective for fibromyalgia patients with coexisting depression (Ormseth et al., 2010). A drug evaluation paper concluded that milnacipran gives modest pain relief in fibromyalgia patients and is best used as part of a multidisciplinary treatment strategy (Bernstein et al., 2013). The results of another study showed that milnacipran significantly reduced pain scores, helped patients to achieve lower mean global impression scores, and significantly increased response rates, regardless of the depressive symptoms at baseline (Arnold et al., 2012). Milnacipran has some major but rare side effects such as worsening suicide risk and causing liver damage (Montgomery and Briley, 2010; Park and Ishino, 2013). Moreover, some common side effects include gastrointestinal upset and urinary disorders (Tignol et al., 1998; Levin, 2016). Interestingly, milnacipran does not inhibit the cytochrome P 450 system, which reduces the chances of possible interactions with other drugs (Pae et al., 2009; Paris et al., 2009). The five studies that have used milnacipran in phase IV trials to treat fibromyalgia are shown in Table 1.

Duloxetine is a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) (Westanmo et al., 2005; JS et al., 2019). Pre-clinical studies show that duloxetine can alleviate diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, fatigue, pain and other related symptoms (Wernicke et al., 2006). It has also been found to significantly reduce pain and improve functioning in patients with chronic low back pain (Skljarevski et al., 2010). In patients with fibromyalgia, duloxetine improved average pain severity and self-reported improvement (Chappell et al., 2008). It has also been found to be effective in the long-term treatment of fibromyalgia (Mease et al., 2010). The study by Mease et al. (2010) reported that dry mouth and nausea were the most reported side effect, but duloxetine is generally safe and well tolerated, including in older patients and those with concomitant illnesses (Wernicke et al., 2005). It is preferably avoided in patients with hepatic insufficiency.

Pregabalin, the first of the three medications that have gained US FDA approval for fibromyalgia, is an α2 δ ligand that acts by binding the α2 δ subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels (Micó and Prieto, 2012). This leads to a decrease in calcium influx at nerve terminals, with a consequential modulation in excitatory neurotransmitter release pain-related neurotransmitters, including glutamate and substance P (Tanabe et al., 2008; Alles et al., 2020). Studies have also suggested that pain associated with major depressive disorder can be reduced with pregabalin (Showraki, 2007; Stein et al., 2008; Frampton, 2014). Previous studies concluded that pregabalin was generally well tolerated in the long-term treatment of anxiety disorders (Feltner et al., 2008; Montgomery et al., 2013). Generally, pregabalin is safe and well tolerated (Durkin et al., 2010). However, number of uncomfortable side effects have been reported with pregabalin, although these tend to be transient and dose dependent (Zin et al., 2010; Toth, 2014). Only a single clinical trial was available at phase IV as shown in Table 1.

Tramadol is a centrally acting, fully synthetic opioid and one of the most commonly used central nervous system analgesics (Leppert, 2009; Duehmke et al., 2017). It is an effective and well tolerated agent that is taken to reduce pain (Minami et al., 2015; Nakhaee et al., 2021). Tramadol can be used as a second-line treatment for more resistant cases in fibromyalgia patients and it has a positive effect on fibromyalgia pain (Maclean and Schwartz, 2015; Pereira Da Rocha et al., 2020). On the other hand, acetaminophen is a central analgesic drug that is mediated through the activation of descending serotonergic pathways (Pickering et al., 2008; Jozwiak-Bebenista and Nowak, 2014). Only one single clinical trial was available at phase IV as shown in Table 1. In fibromyalgia, a combination of tramadol and acetaminophen was effective for the treatment of fibromyalgia pain without any serious adverse effects (Bennett et al., 2003).

Armodafinil is the R-enantiomer of racemic modafinil, a wakefulness-promoting medication, that primarily affects the areas of the brain involved in controlling wakefulness (Hirshkowitz et al., 2007; Garnock-Jones et al., 2009). The mechanism of action of armodafinil is not completely understood. It is mainly used for the treatment of excessive sleepiness associated with narcolepsy, and obstructive sleep apnea (Lankford, 2008; Schwartz et al., 2010). The potential role of stimulants such as armodafinil is often to manage the fatigue that is a common symptom of fibromyalgia. It has been used to improve menopause-related fatigue (Meyer et al., 2016) and sarcoidosis-associated fatigue (Lower et al., 2013). However, only a single clinical trial was available at phase IV for fibromyalgia management. The study concluded that there was no significant difference in any effectiveness outcome (Thomas et al., 2010).

Fibromyalgia is a chronic, life-long condition with no single cure. There is no one treatment that can treat all the symptoms of fibromyalgia since the condition has many symptoms. Pain severity, global severity and physical functioning are significantly and negatively influenced by fibromyalgia. Also, psychological factors such as anxiety, stress, and depression exacerbate the condition. The treatments being assessed in the 10 trials reviewed here aimed to improve several health parameters, including physical fitness, work and other functional activities, and mental health. This review focused on medication that was tested in phase IV clinical trials only. The drugs used in phase IV trials for fibromyalgia are milnacipran, duloxetine, pregabalin, a combination of tramadol and acetaminophen, and armodafinil. The US FDA has approved three drugs to treat fibromyalgia: milnacipran, duloxetine and pregabalin, as shown in Table 2. Of these milnacipran is exclusively for the management of fibromyalgia. Both milnacipran and duloxetine act as selective serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors. A considerable amount of research concluded that patients with fibromyalgia have abnormally low levels of serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine in their brains, which leads to serious side effects including the worsening of fibromyalgia status. Serotonin regulates numerous bodily functions. In adult patients with fibromyalgia, milnacipran, duloxetine and pregabalin were associated with significant improvements in pain and other symptoms. One of the considerations that should be included in future investigations is the combined therapy of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments to manage fibromyalgia symptoms. Further clinical trials investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments used for fibromyalgia are warranted.

The findings from the review suggest that the drugs most commonly used for fibromyalgia that can be considered first-line options are milnacipran, duloxetine, and pregabalin. The number of trials for fibromyalgia are extremely limited Pharmacological options can be employed to provide patients with a better quality of life. Despite years of investigation of pharmacological treatments for fibromyalgia, non-pharmacological treatments show promise for future investigation.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abeles, A. M., Pillinger, M. H., Solitar, B. M., and Abeles, M. (2007). Narrative review: The pathophysiology of fibromyalgia. Ann. Intern. Med. 146, 726–734. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00006

Ablin, J., Fitzcharles, M. A., Buskila, D., Shir, Y., Sommer, C., and Häuser, W. (2013). Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: Recommendations of recent evidence-based interdisciplinary guidelines with special emphasis on complementary and alternative therapies. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2013, 1–7. doi:10.1155/2013/485272

Alles, S. R. A., Cain, S. M., and Snutch, T. P. (2020). Pregabalin as a pain therapeutic: Beyond calcium channels. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 14, 83. doi:10.3389/FNCEL.2020.00083/BIBTEX

Aman, M. M., Jason Yong, R., Kaye, A. D., and Urman, R. D. (2018). Evidence-Based non-pharmacological therapies for fibromyalgia. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 22, 33. doi:10.1007/S11916-018-0688-2

Amsterdam, D., and Buskila, D. (2021). Etiology and triggers in the development of fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia Syndr., 17–31. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78638-0_3

Andrade, A., Vilarino, G. T., Sieczkowska, S. M., Coimbra, D. R., Bevilacqua, G. G., and Steffens, R. de A. K. (2020). The relationship between sleep quality and fibromyalgia symptoms. J. Health Psychol. 25, 1176–1186. doi:10.1177/1359105317751615

Arnold, L. M., Crofford, L. J., Mease, P. J., Burgess, S. M., Palmer, S. C., Abetz, L., et al. (2008). Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Educ. Couns. 73, 114–120. doi:10.1016/J.PEC.2008.06.005

Arnold, L. M., Palmer, R. H., Gendreau, R. M., and Chen, W. (2012). Relationships among pain, depressed mood, and global status in fibromyalgia patients: Post hoc analyses of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of milnacipran. Psychosomatics 53, 371–379. doi:10.1016/J.PSYM.2012.02.005

Ayouni, I., Chebbi, R., Hela, Z., and Dhidah, M. (2019). Comorbidity between fibromyalgia and temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 128, 33–42. doi:10.1016/J.OOOO.2019.02.023

Becker, S., and Schweinhardt, P. (2012). Dysfunctional neurotransmitter systems in fibromyalgia, their role in central stress circuitry and pharmacological actions on these systems. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 1–10. doi:10.1155/2012/741746

Bennett, R. M., Kamin, M., Karim, R., and Rosenthal, N. (2003). Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the treatment of fibromyalgia pain: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am. J. Med. 114, 537–545. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00116-5

Bernik, M., Sampaio, T. P. A., and Gandarela, L. (2013). Fibromyalgia comorbid with anxiety disorders and depression: Combined medical and psychological treatment. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 17, 358–359. doi:10.1007/S11916-013-0358-3

Bernstein, C. D., Albrecht, K. L., and Marcus, D. A. (2013). Milnacipran for fibromyalgia: A useful addition to the treatment armamentarium. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 14, 905–916. doi: doi:10.1517/14656566.2013.779670

Briley, S., and Briley, M. (2010). Editorial foreword - milnacipran: Recent findings in depression. Ndt 6, 1. doi:10.2147/NDT.S11773

Cagnie, B., Coppieters, I., Denecker, S., Six, J., Danneels, L., and Meeus, M. (2014). Central sensitization in fibromyalgia? A systematic review on structural and functional brain mri. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 44, 68–75. doi:10.1016/J.SEMARTHRIT.2014.01.001

Chappell, A. S., Bradley, L. A., Wiltse, C., Detke, M. J., D'Souza, D. N., and Spaeth, M. (2008). A six-month double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of duloxetine for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 1, 91–102. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S3979

Clauw, D. J. (2009). Fibromyalgia: An overview. Am. J. Med. 122, S3. S3–S13. doi:10.1016/J.AMJMED.2009.09.006

Corrigan, R., Derry, S., Wiffen, P. J., and Moore, R. A. (2012). Clonazepam for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adultsCochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, CD009486. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009486.pub2

Costa, J., Ranzolin, A., da Costa Neto, C., Marques, C., Duarte, L., Branco, A. L., et al. (2016). High frequency of asymptomatic hyperparathyroidism in patients with fibromyalgia: Random association or misdiagnosis? Rev. Bras. Reumatol. Engl. Ed. 56, 391–397. doi:10.1016/J.RBRE.2016.03.008

da Rocha, A., Mizzaci, C. C., Nunes Pinto, A. C., da Silva Vieira, N., Civile, A., Trevisani, S., et al. (2020). Tramadol for management of fibromyalgia pain and symptoms: Systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 74, e13455. doi:10.1111/IJCP.13455

Desmeules, J. A., Cedraschi, C., Rapiti, E., Baumgartner, E., Finckh, A., Cohen, P., et al. (2003). Neurophysiologic evidence for a central sensitization in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 48, 1420–1429. doi:10.1002/ART.10893

Duehmke, R. M., Derry, S., Wiffen, P. J., Bell, R. F., Aldington, D., and Moore, R. A. (2017). Tramadol for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. 6, CD003726. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003726.PUB4/MEDIA

Durkin, B., Page, C., and Glass, P. (2010). Pregabalin for the treatment of postsurgical pain. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 11, 2751–2758. doi: doi:10.1517/14656566.2010.526106

Elliott, M. B., Barr, A. E., and Barbe, M. F. (2009). Spinal substance P and neurokinin-1 increase with high repetition reaching. Neurosci. Lett. 454, 33–37. doi:10.1016/J.NEULET.2009.01.037

Feltner, D., Wittchen, H. U., Kavoussi, R., Brock, J., Baldinetti, F., and Pande, A. C. (2008). Long-term efficacy of pregabalin in generalized anxiety disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 23, 18–28. doi:10.1097/YIC.0B013E3282F0F0D7

Frampton, J. E. (2014). Pregabalin: A review of its use in adults with generalized anxiety disorder. CNS Drugs 28, 835–854. doi:10.1007/S40263-014-0192-0/TABLES/7

Garnock-Jones, K. P., Dhillon, S., and Scott, L. J. (2009). Armodafinil. CNS Drugs 23, 793–803. doi:10.2165/11203290-000000000-00000/FIGURES/3

Geisser, M. E., Glass, J. M., Rajcevska, L. D., Clauw, D. J., Williams, D. A., Kileny, P. R., et al. (2008). A psychophysical study of auditory and pressure sensitivity in patients with fibromyalgia and healthy controls. J. Pain 9, 417–422. doi:10.1016/J.JPAIN.2007.12.006

Goldenberg, D. L., Burckhardt, C., and Crofford, L. (2004). Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA 292, 2388–2395. doi:10.1001/JAMA.292.19.2388

Guymer, E., and Littlejohn, G. (2021). Pharmacological treatment of fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia Syndr., 33–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78638-0_4

Hassett, A. L., and Gevirtz, R. N. (2009). Nonpharmacologic treatment for fibromyalgia: Patient education, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation techniques, and complementary and alternative medicine. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 35, 393–407. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.003

Hassett, A. L., and Williams, D. A. (2011). Non-pharmacological treatment of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 25, 299–309. doi:10.1016/J.BERH.2011.01.005

Häuser, W., Ablin, J., Fitzcharles, M. A., Littlejohn, G., Luciano, J. V., Usui, C., et al. (2015). Fibromyalgia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 1, 15022. doi:10.1038/NRDP.2015.22

Häuser, W., Bernardy, K., Üçeyler, N., and Sommer, C. (2009). Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants. JAMA 301, 198–209. doi:10.1001/JAMA.2008.944

Hirshkowitz, M., Black, J. E., Wesnes, K., Niebler, G., Arora, S., and Roth, T. (2007). Adjunct armodafinil improves wakefulness and memory in obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Respir. Med. 101, 616–627. doi:10.1016/J.RMED.2006.06.007

Hsu, D., Bc, S., and M, M. (2010). Duloxetine. Duloxetine. Essence Analg. Analg., 353–356. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511841378.087

Johnson, C. M., and Makai, G. E. H. (2018). Fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome in female pelvic pain. Semin. Reprod. Med. 36, 136–142. doi:10.1055/S-0038-1676090/ID/JR001133-44

Jozwiak-Bebenista, M., and Nowak, J. Z. (2014). Paracetamol: Mechanism of action, applications and safety concern. Acta Pol. Pharm. 71, 11–23. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/med/24779190?utm_medium=email&utm_source=transaction&client=bot&client=bot&client=bot.

Kyle, J. A., Dugan, B. D. A., and Testerman, K. K. (2010). Milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia. Ann. Pharmacother. 44, 1422–1429. doi:10.1345/aph.1P218

Lankford, D. A. (2008). Armodafinil: A new treatment for excessive sleepiness. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 17, 565–573. doi:10.1517/13543784.17.4.565

Larson, A. A., Giovengo, S. L., Russell, I. J., and Michalek, J. E. (2000). Changes in the concentrations of amino acids in the cerebrospinal fluid that correlate with pain in patients with fibromyalgia: Implications for nitric oxide pathways. Pain 87, 201–211. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00284-0

Lawson, K. (2002). Tricyclic antidepressants and fibromyalgia: What is the mechanism of action? Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 11, 1437–1445. doi:10.1517/13543784.11.10.1437

Leppert, W. (2009). Tramadol as an analgesic for mild to moderate cancer pain. Pharmacol. Rep. 61, 978–992. doi:10.1016/S1734-1140(09)70159-8

Levin, A. (2016). Low-dose buprenorphine may Be first treatment step. Pn 51, 1. doi:10.1176/APPI.PN.2016.2A22

Lower, E. E., Malhotra, A., Surdulescu, V., and Baughman, R. P. (2013). Armodafinil for sarcoidosis-associated fatigue: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 45, 159–169. doi:10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2012.02.016

MacLean, A. J. B., and Schwartz, T. L. (2015). Tramadol for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Expert Rev. Neurother. 15, 469–475. doi:10.1586/14737175.2015.1034693

Martenson, M. E., Halawa, O. I., Tonsfeldt, K. J., Maxwell, C. A., Hammack, N., Mist, S. D., et al. (2016). A possible neural mechanism for photosensitivity in chronic pain. Pain 157, 868–878. doi:10.1097/J.PAIN.0000000000000450

Martin, D. P., Sletten, C. D., Williams, B. A., and Berger, I. H. (2006). Improvement in fibromyalgia symptoms with acupuncture: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin. Proc. 81, 749–757. doi:10.4065/81.6.749

Maugars, Y., Berthelot, J. M., Le Goff, B., and Darrieutort-Laffite, C. (2021). Fibromyalgia and associated disorders: From pain to chronic suffering, from subjective hypersensitivity to hypersensitivity syndrome. Front. Med. 8, 948. doi:10.3389/FMED.2021.666914/XML

Mease, P. J., Russell, I. J., Kajdasz, D. K., Wiltse, C. G., Detke, M. J., Wohlreich, M. M., et al. (2010). Long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of duloxetine in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 39, 454–464. doi:10.1016/J.SEMARTHRIT.2008.11.001

Menzies, V., Thacker, L. R., Mayer, S. D., Young, A. M., Evans, S., and Barstow, L. (2017). Polypharmacy, opioid use, and fibromyalgia: A secondary analysis of clinical trial data. Biol. Res. Nurs. 19, 97–105. doi:10.1177/1099800416657636

Meyer, F., Freeman, M. P., Petrillo, L., Barsky, M., Galvan, T., Kim, S., et al. (2016). Armodafinil for fatigue associated with menopause: An open-label trial. Menopause 23, 209–214. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000505

Micó, J. A., and Prieto, R. (2012). Elucidating the mechanism of action of pregabalin: α 2δ as a therapeutic target in anxiety. CNS Drugs 26, 637–648. doi:10.2165/11634510-000000000-00000/FIGURES/TAB2

Minami, K., Ogata, J., and Uezono, Y. (2015). What is the main mechanism of tramadol? Naunyn. Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol. 388, 999–1007. doi:10.1007/S00210-015-1167-5/TABLES/4

Montgomery, S., Emir, B., Haswell, H., and Prieto, R. (2013). Long-term treatment of anxiety disorders with pregabalin: A 1 year open-label study of safety and tolerability. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 29, 1223–1230. doi:10.1185/03007995.2013.820694

Nakhaee, S., Hoyte, C., Dart, R. C., Askari, M., Lamarine, R. J., and Mehrpour, O. (2021). A review on tramadol toxicity: Mechanism of action, clinical presentation, and treatment. Forensic Toxicol. 39, 293–310. doi:10.1007/S11419-020-00569-0

Neumann, L., and Buskila, D. (2003). Epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 7 (7), 362–368. doi:10.1007/S11916-003-0035-Z

Nüesch, E., Häuser, W., Bernardy, K., Barth, J., and Jüni, P. (2013). Comparative efficacy of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions in fibromyalgia syndrome: Network meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 955–962. doi:10.1136/ANNRHEUMDIS-2011-201249

Oliveira Júnior, J. O. de, and Ramos, J. V. C. (2019). Adherence to fibromyalgia treatment: Challenges and impact on the quality of life. BrJP 2, 81–87. doi:10.5935/2595-0118.20190015

Ormseth, M. J., Eyler, A. E., Hammonds, C. L., and Boomershine, C. S. (2010). Milnacipran for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome. J. Pain Res. 3, 15–24. doi:10.2147/JPR.S7883

Owen, R. T. (2008). Milnacipran hydrochloride: Its efficacy, safety and tolerability profile in fibromyalgia syndrome. Drugs Today (Barc) 44, 653–660. doi:10.1358/DOT.2008.44.9.1256003

Pae, C. U., Marks, D. M., Shah, M., Han, C., Ham, B. J., Patkar, A. A., et al. (2009). Milnacipran: Beyond a role of antidepressant. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 32, 355–363. doi:10.1097/WNF.0B013E3181AC155B

Palmer, R. H., Periclou, A., and Banerjee, P. (2010). Milnacipran: A selective serotonin and norepinephrine dual reuptake inhibitor for the management of fibromyalgia. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2, 201–220. doi:10.1177/1759720X10372551

Paris, B. L., Ogilvie, B. W., Scheinkoenig, J. A., Ndikum-Moffor, F., Gibson, R., and Parkinson, A. (2009). In vitro inhibition and induction of human liver cytochrome P450 enzymes by milnacipran. Drug Metab. Dispos. 37, 2045–2054. doi:10.1124/DMD.109.028274

Park, H. S., and Ishino, R. (2013). Liver injury associated with antidepressants. Curr. Drug Saf. 8, 207–223. doi:10.2174/1574886311308030011

Pickering, G., Estève, V., Loriot, M. A., Eschalier, A., and Dubray, C. (2008). Acetaminophen reinforces descending inhibitory pain pathways. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 84, 47–51. doi:10.1038/SJ.CLPT.6100403

Raouf, M., Glogowski, A. J., Bettinger, J. J., and Fudin, J. (2017). Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and the influence of binding affinity (Ki) on analgesia. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 42, 513–517. doi:10.1111/JCPT.12534

Russell, J., Kamin, M., Bennett, R. M., Schnitzer, T. J., Green, J. A., and Katz, W. A. (2000). Efficacy of tramadol in treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 6, 250–257. doi:10.1097/00124743-200010000-00004

Santos, C. E. M., Rodrigues, V. P., De Oliveira, I. C. V., De Assis, D. S. F. R., De Oliveira, M. M., and Conti, C. F. (2019). Morphological changes in the temporomandibular joints in women with fibromyalgia and myofascial pain: A case series. Cranio. 39:440–444. doi:10.1080/08869634.2019.1650215

Sarac, A., and Gur, A. (2005). Complementary and alternative medical therapies in fibromyalgia. Curr. Pharm. Des. 12, 47–57. doi:10.2174/138161206775193262

Sarchielli, P., Di Filippo, M., Nardi, K., and Calabresi, P. (2007). Sensitization, glutamate, and the link between migraine and fibromyalgia. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 11, 343–351. doi:10.1007/S11916-007-0216-2

Sarzi-Puttini, P., Buskila, D., Carrabba, M., Doria, A., and Atzeni, F. (2008). Treatment strategy in fibromyalgia syndrome: Where are we now? Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 37, 353–365. doi:10.1016/J.SEMARTHRIT.2007.08.008

Schwartz, J. R., Roth, T., and Drake, C. (2010). Armodafinil in the treatment of sleep/wake disorders. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 6, 417–427. doi:10.2147/NDT.S3004

Schwartz, L. S., Siddiqui, U. A., Raza, S., and Morell, M. (2010). Armodafinil for fibromyalgia fatigue. Ann. Pharmacother. 44, 1347–1348. doi:10.1345/APH.1M736

Scott, J. R., Hassett, A. L., Brummett, C. M., Harris, R. E., Clauw, D. J., and Harte, S. E. (2017). Caffeine as an opioid analgesic adjuvant in fibromyalgia. J. Pain Res. 10, 1801–1809. doi:10.2147/JPR.S134421

Shaver, J. L. F. (2008). Sleep disturbed by chronic pain in fibromyalgia, irritable bowel, and chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Sleep. Med. Clin. 3, 47–60. doi:10.1016/J.JSMC.2007.10.007

Showraki, M. (2007). Pregabalin in the treatment of depression. J. Psychopharmacol. 21, 883–884. doi:10.1177/0269881107078496

Silver, D. S., and Wallace, D. J. (2002). The management of fibromyalgia-associated syndromes. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 28, 405–417. doi:10.1016/S0889-857X(02)00003-0

Skljarevski, V., Desaiah, D., Liu-Seifert, H., Zhang, Q., Chappell, A. S., Detke, M. J., et al. (2010). Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 35, E578–E585. doi:10.1097/BRS.0B013E3181D3CEF6

Sommer, C., Häuser, W., Gerhold, K., Joraschky, P., Petzke, F., Tölle, T., et al. (2008). Etiology and pathophysiology of fibromyalgia syndrome and chronic widespread pain. Schmerz 22, 267–282. doi:10.1007/S00482-008-0672-6

Staud, R., and Domingo, M. A. (2001). Evidence for abnormal pain processing in fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain Med. 2, 208–215. doi:10.1046/J.1526-4637.2001.01030.X

Staud, R. (2002). Evidence of involvement of central neural mechanisms in generating fibromyalgia pain. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 4 (4), 299–305. doi:10.1007/S11926-002-0038-5

Stein, D. J., Baldwin, D. S., Baldinetti, F., and Mandel, F. (2008). Efficacy of pregabalin in depressive symptoms associated with generalized anxiety disorder: A pooled analysis of 6 studies. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18, 422–430. doi:10.1016/J.EURONEURO.2008.01.004

Sumpton, J. E., and Moulin, D. E. (2014). Fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 119, 513–527. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-4086-3.00033-3

Tanabe, M., Takasu, K., Takeuchi, Y., and Ono, H. (2008). Pain relief by gabapentin and pregabalin via supraspinal mechanisms after peripheral nerve injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 86, 3258–3264. doi:10.1002/JNR.21786

Tignol, J., Pujol-Domenech, J., Chartres, J. P., Léger, J. M., Plétan, Y., Tonelli, I., et al. (1998). Double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of milnacipran and imipramine in elderly patients with major depressive episode. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 97, 157–165. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0447.1998.TB09980.X

Tofferi, J. K., Jackson, J. L., and O'Malley, P. G. (2004). Treatment of fibromyalgia with cyclobenzaprine: A meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 51, 9–13. doi:10.1002/ART.20076

Toth, C. (2014). Pregabalin: Latest safety evidence and clinical implications for the management of neuropathic pain. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 5, 38–56. doi:10.1177/2042098613505614

Walitt, B., Urrútia, G., Nishishinya, M. B., Cantrell, S. E., and Häuser, W. (2015). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane database Syst. Rev. 2015:CD011735. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011735

Wernicke, J. F., Gahimer, J., Yalcin, I., Wulster-Radcliffe, M., and Viktrup, L. (2005). Safety and adverse event profile of duloxetine. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 4(6):987–993. doi: doi:10.1517/14740338.4.6.987

Wernicke, J. F., Pritchett, Y. L., D'Souza, D. N., Waninger, A., Tran, P., Iyengar, S., et al. (2006). A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine in diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Neurology 67, 1411–1420. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000240225.04000.1A

Westanmo, A. D., Gayken, J., and Haight, R. (2005). Duloxetine: A balanced and selective norepinephrine- and serotonin-reuptake inhibitor. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 62, 2481–2490. doi:10.2146/AJHP050006

Yoshida, K., Takahashi, H., Higuchi, H., Kamata, M., Ito, K. I., Sato, K., et al. (2004)., 161, 1575–1580. doi:10.1176/APPI.AJP.161.9.1575/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/N29F3Prediction of antidepressant response to milnacipran by norepinephrine transporter gene polymorphismsAm. J. Psychiatry

Yunus, M. B. (2012). The prevalence of fibromyalgia in other chronic pain conditions. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 1–8. doi:10.1155/2012/584573

Yunus, M. B. (2001). The role of gender in fibromyalgia syndrome. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 3, 128–134. doi:10.1007/S11926-001-0008-3

Zheng, L., and Faber, K. (2005). Review of the Chinese medical approach to the management of fibromyalgia. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 9 (9), 307–312. doi:10.1007/S11916-005-0004-9

Zin, C. S., O'Callaghann, L. M., Smithln, J. P., Moore, S. B., Smith, M. T., and Moore, B. J. (2010). A randomized, controlled trial of oxycodone versus placebo in patients with PostHerpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy treated with pregabalin. J. Pain 11, 462–471. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2009.09.003

Keywords: fibromyalgia, pain, clinical trials, neuroscience, phase IV

Citation: Alorfi NM (2022) Pharmacological treatments of fibromyalgia in adults; overview of phase IV clinical trials. Front. Pharmacol. 13:1017129. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1017129

Received: 11 August 2022; Accepted: 09 September 2022;

Published: 23 September 2022.

Edited by:

Francisco Lopez-Munoz, Camilo José Cela University, SpainCopyright © 2022 Alorfi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nasser M. Alorfi, bm1vcmZpQHVxdS5lZHUuc2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.