- 1School of Information and Control Engineering, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, Shandong, China

- 2College of Computer science and Technology, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, Shandong, China

Accurate identification of Drug Target Interactions (DTIs) is of great significance for understanding the mechanism of drug treatment and discovering new drugs for disease treatment. Currently, computational methods of DTIs prediction that combine drug and target multi-source data can effectively reduce the cost and time of drug development. However, in multi-source data processing, the contribution of different source data to DTIs is often not considered. Therefore, how to make full use of the contribution of different source data to predict DTIs for efficient fusion is the key to improving the prediction accuracy of DTIs. In this paper, considering the contribution of different source data to DTIs prediction, a DTIs prediction approach based on an effective fusion of drug and target multi-source data is proposed, named EFMSDTI. EFMSDTI first builds 15 similarity networks based on multi-source information networks classified as topological and semantic graphs of drugs and targets according to their biological characteristics. Then, the multi-networks are fused by selective and entropy weighting based on similarity network fusion (SNF) according to their contribution to DTIs prediction. The deep neural networks model learns the embedding of low-dimensional vectors of drugs and targets. Finally, the LightGBM algorithm based on Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) is used to complete DTIs prediction. Experimental results show that EFMSDTI has better performance (AUROC and AUPR are 0.982) than several state-of-the-art algorithms. Also, it has a good effect on analyzing the top 1000 prediction results, while 990 of the first 1000DTIs were confirmed. Code and data are available at https://github.com/meng-jie/EFMSDTI.

1 Introduction

The accurate prediction of DTIs is worth that improves the speed and accuracy of new drug discovery. Although the traditional experimental methods have made some progress in DTIs identification, it is a costly, time-consuming process with a high failure rate (Whitebread et al., 2005; Avorn, 2015; Zhao et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019). With the popularity of artificial intelligence concepts and technologies such as machine learning, more and more researchers are applying machine learning to predict DTIs, dramatically accelerating the new drug development process and revolutionizing the traditional drug development process. It provides accurate drug candidates for drug discovery, further reducing the cost and time of drug discovery. Currently, many researchers have focused on DTI prediction and achieved remarkable achievements through machine learning and deep learning (Li et al., 2016; Ezzat et al., 2019; Abbasi et al., 2020; Bagherian et al., 2021).

Over recent years, a substantial number of computational methods have been developed for predicting drug discovery (Zhu et al., 2005; Sousa et al., 2006; Keiser et al., 2007; Bleakley and Yamanishi, 2009; Buza and Peška, 2017; Luo et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2018; Olayan et al., 2018; Wan et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020a; Tang et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020; An and Yu, 2021; Chu et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021; Zong et al., 2021). Target-based (Sousa et al., 2006), ligand similarity-based (Keiser et al., 2007) and machine learning-based (Zhu et al., 2005) methods are the three main-stream in prediction methods. However, obtaining the 3D structure of the protein is very time-consuming, making it difficult to use the target-based approach on a genome-wide scale. Similarly, the ligand-based target prediction usually depends on the structural characteristics of known target ligands. However, the number of known ligands from a single data source for the target protein is insufficient, and the prediction results of ligand-based methods may become unreliable. Currently, with the increasing availability of public data sets, the prediction of DTIs based on machine learning methods has been widely proposed and applied in recent years (Bleakley and Yamanishi, 2009). Moreover, huge amounts of multi-source data are being used to study the properties of drugs and targets to predict DTIs (Tao et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022).

In the calculation strategy of DTIs prediction, multiple drug and target data sources are often considered. Multi-source data of drugs and targets contain their inherent features and network topology information based on other attributes such as drug side effects. It is found that topology and semantic information often play different roles in the prediction task by analyzing the topological structure and feature graphs using the attention mechanism (Wang et al., 2020b). Tang et al. (2020) provided a marginalized denoising model to predict DTIs by calculating the similarities of target protein sequences and drug chemical structure. Chu et al. (2021) developed DTI-CDF model to predict DTIs through integrating target protein sequences and three drug side effects datasets. It uses multiple data sources to analyze drugs and targets. However, only the side effect and target protein sequences of drugs were considered, and other information about drugs and targets, such as the molecular structure of drugs and disease target correlation, was not considered, which may lose part of the information of drugs targets, resulting in inaccurate DTIs prediction. Olayan et al. (2018) proposed DDR model based on multi-source data of drug and target. It contains eight drug similarity networks and eight target similarity networks, which consider both topology and semantic in-formation. Although the fusion of multi-source data is considered, the contribution of different data sources is not considered. Zeng et al. (2020) proposed deepDTnet model based on multi-source data to predict DTIs. The feature vectors of drugs and tar-gets were learned and spliced for multi-source data of drugs and targets. They treated data from different sources equally, but different data often play different roles in DTIs prediction. An et al. proposed NEDTP model based on network embedding framework (An and Yu, 2021). They applied a random walk to extract the information of each node in the network and learn it as a low-dimensional vector. Finally, the GBDT model was constructed to complete the classification task. Although they consider how to extract and merge multi-source data, they learned the embedding features of drugs and targets by treating random walking paths through different networks equally, without fully considering the contributions of different data sources. Therefore, effectively fusing multi-source data is a challenge for accurately identifying DTIs through considering the topological and semantic information of multi-source data and exploring the weight of different networks. Yan et al. (2019) proposed MKLC-BiRW model to predict DTIs. Although they integrated multi-source heterogeneous data based on the kernel idea of KronrLS-MKL algorithm, they did not comprehensively organize the related data of drugs and targets.

In this paper, we propose a framework named EFMSDTIs to predict DTIs based on the effective fusion of multi-source data. Specifically, EFMSDTI constructed similarity networks of multi-source drugs and targets from heterogeneous data, including the biological characteristics, molecular structure, biological function of drugs and targets. By classifying the different source data of drugs and targets, the drug and target similarity network is divided into the semantic graphs and topology graphs. We propose a selection and weighted entropy fusion algorithm based on SNF (Wang et al., 2014) for the semantic and topology graphs. Network embedding algorithm extracts low-dimensional features of drugs and targets. Finally, the features of drugs and targets learned were input into the prediction model to improve the prediction accuracy of DTIs. The results show that EFMSDTI has better performance over several state-of-art algorithms by classifying the data and treating the classified data with different weights during fusion.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Overview of the EFMSDTI method

Considering the contribution of different source data to DTIs prediction, a framework called EFMSDTI is proposed to predict DTIs. In Figure 1, firstly, multi-source data of drugs and targets can be fused (including selective fusion and weighted fusion) or spliced by classifying multi-source data of them (see Results). For original data, it includes the topological graph (such as Drug-drug, Drug-disease, Drug-side Effect, Target-target, and Target-disease) and semantic graph (such as Drug similarities and Target similarities). According to the biological characteristics of the drug or target, drug or target related networks are divided into several categories, respectively. When there are multiple networks in a category, whether to fuse them into one network is determined according to the contribution of them to DTI prediction. Secondly, the networks are embedded to obtain the low-dimensional representations of drugs and targets based on the Deep neural Networks model for Graph Representations (DNGR) (Shaosheng et al., 2016), respectively. Finally, LightGBM (Qi, 2017) is used to predict the potential DTIs. EFMSDTI has the advantage that a selective weighted fusion algorithm based on similarity fusion is proposed according to the contribution of different source data to DTIs prediction. The aim is to explore an optimal scheme for predicting DTIs by classifying drugs and targets from multiple data sources according to their topology and semantic graphs.

FIGURE 1. EFMSDTI framework of predicting DTIs. EFMSDTI constructs 15 drug-related networks and target-related networks from heterogeneous multi-source data. Based on the contribution of the class network, the drug and target networks are fused or spliced after the network embedding. Through selective and weighted fusion based on SNF and extract low-dimensional vector of drugs and targets, then features are input into the LightGBM to predict DTIs. Among them, drug-related networks are DDI (Drug-drug), DD (Drug-disease), DSE (Drug-sideEffect), SDC (Chemical similarities), SDATC (ATC similarities), SDP (Drug targets sequence similarities), SDMF (molecular function similarities), SDCC (cellular component similarities) and SDBP (biological process similarities), target-related networks are TTI (Target-target-interaction), TD (Target-disease), STP (Target sequence similarities), STMF (molecular function similarities), STCC (cellular component similarities) and STBP (biological process similarities).

2.2 Data source

The drug and target are collected from the DrugBank database (v4.3) (Wishart et al., 2017), the Therapeutic Target Database (Yang et al., 2016), and the PharmGKB database (Hernandez-Boussard et al., 2008). Specifically, bioactivity data for drug–target pairs are collected from ChEMBL (v20) (Gaulton et al., 2012), BindingDB (Liu et al., 2007), and IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014). A total of 4978 DTIs are used to build a drug-target interaction network by 732 FDA-approved drugs and 1915 unique human targets (proteins), which include nine different data describing drugs and six data describing targets which refer to Zeng’s work (Zeng et al., 2020). The goal is to analyze the properties of drugs and targets from as many aspects and perspectives as possible in order to improve the prediction accuracy of DTIs.

2.2.1 Drug-related networks

For drugs, there are nine drug-related networks: (i) drug-drug interaction (DDI), (ii) drug-disease (DD), (iii) drug side-effect (DSE), (iv) chemical similarity (SDC), (v) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) (Cheng et al., 2013) similarity (SDATC), (vi) protein sequence similarity (SDP), (vii) Go (SDGO) molecular function similarity (SDMF), (viii) Go cellular component similarity (STCC), (ix) Go biological process similarity (STBP). Where (ii) and (iii) calculate their similarity through the Jaccard coefficient.

2.2.2 Target-related networks

For targets, there are six target-related networks: (i) target-target interaction (TTI), (ii) target-disease (TD), (iii) target protein sequence similarity (STP), (iv) Go (STGO) molecular function similarity (STMF), (v) Go cellular component similarity (STCC), (vi) Go biological process similarity (STBP). Where (ii) calculates its similarity through the Jaccard coefficient.

2.2.3 Drug-target interaction network

The drug-target interaction network is described by a bipartite graph

2.3 Biometric classification of networks from multiple information

In order to facilitate and effectively evaluate the contribution of different source data to DTI prediction, we divide them into topology and semantic graphs according to the information described by the network manually. Take drugs for example, the drug-drug similarity network, which is obtained through the association of various drugs, is considered as a topological graph; and drug-drug similarity networks based on drug attributes, such as drug molecular structure and drug classification, are considered as semantic graphs. Therefore, the association networks, including DDI, DSE, DD, TTI and TD, are the topology graphs of drugs and targets. The similarity networks between drugs (or targets) calculated based on multi-attribute information of drugs (or targets) are considered semantic graphs.

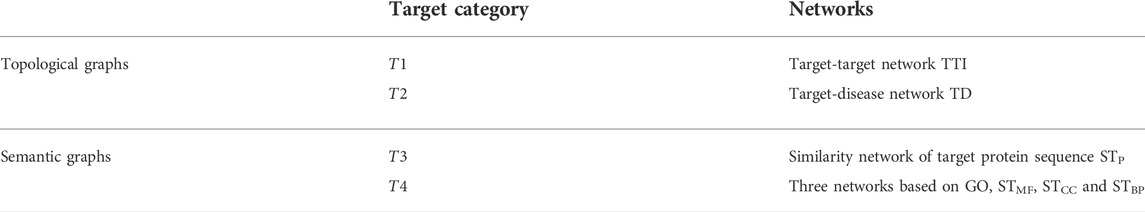

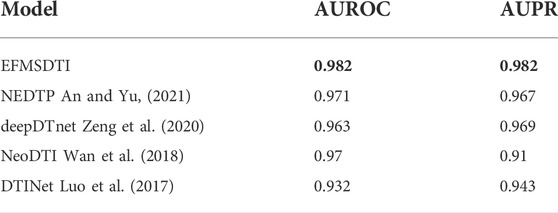

2.3.1 Target classification

The target-related networks contain two types of graphs: one is the topological graphs of the target, including the TTI and the TD, and the other is the semantic graphs of the target, including the STP and the STGO. The above topology and semantic graphs are further subdivided according to the described topology information and semantic similarity:

• The first category

• The second category

• The third category

• The fourth category

2.3.2 Drug classification

For drugs, the topological graphs include DDI, DD and DSE, the semantic graphs are SDC, SDATC, SDP and SDGO. The network corresponding to the topology and semantic graphs of target are further subdivided into six categories:

• The first category

• The second category

• The third category

• The fourth category

• The fifth category

• The sixth category

2.4 Selection and weighted fusion networks based on similarity network fusion

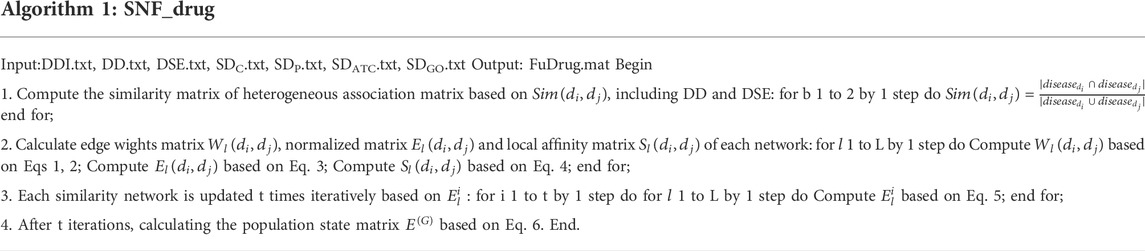

In order to fuse different categories of multi-source data more effectively, we use fusion and splicing methods respectively to achieve drug and target feature representation according to the contribution of the different networks to DTI prediction. Among them, the fusion method of multiple networks in this paper is based on SNF algorithm. The SNF solves a multi-source problem by constructing networks of samples (e.g., drug) for each data type and then efficiently fusing these into one network. The procedure of the algorithm is shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3. The process of six classes of drug networks by using SNF algorithm is described in algorithm 1.

Suppose that there are

where

where

To compute the fused matrix from multiple types of measurements, we need to project multiple data types into the same space. Thus, all data types are normalized by calculating matrix

where the matrix

Considering that different drugs tend to have different numbers of neighbors, K nearest neighbors (KNN) is used to measure local affinity as:

where

After calculating similarity matrixes and local affinity matrixes of drugs under different source data, we iteratively update similarity matrixes as follows:

Finally, we get state matrix

According to the contribution of multi-source data of drugs and targets to DTIs prediction, we will adopt three different strategies for data fusion. Detailed description is as follows.

2.4.1 Selective fusion

Considering the high-noise nature of multi-source data, we measure the contribution of each data source to DTIs prediction. In order to avoid the data with low contribution mixing with high noise in the process of data fusion and affecting the prediction accuracy, the data sources with low contribution are deleted (see Results), and the remaining drug and target data are fused using SNF respectively.

2.4.2 Weighted fusion based on entropy

The drug or target similarity network calculated by each data source often contains different information. Thus, we compute the nodes’ average entropy to determine each network’s information. For any matrix

where

We take entropy as the weight and update

2.4.3 Selective and weighted fusion

Combine the two strategies above, the data are filtered which is based on the feedback of the classification networks’ combined results in Supplementary Table S1 (see Supplementary Material), then similar networks are updated though weighting entropy value of networks.

2.5 Low dimensional vectors for learning node features

In this paper, DNGR model is used to learn node features from multi-source networks. It consists of three parts, including random surfing, calculation of Positive Pointwise Mutual Information (PPMI) matrix and feature reduction by Stacked Denoising Auto Encoder (SDAE).

2.5.1 Random surfing

The random surfing model motivated by the PageRank model used for ranking tasks. The nodes in the network are randomly ordered. For a node, there is a transition matrix

where

2.5.2 Positive pointwise mutual information matrix

In random surfing process, the probabilistic co-occurrence matrix

where

2.5.3 Stacked denoising auto encoder

Finally, the PPMI matrix is used as the input feature

where

2.6 Drug target interactions prediction based on LightGBM

LightGBM which is an efficient implementation of Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (Friedman, 2001) (GBDT) is proposed by Microsoft. GBDT is a decision tree-based algorithm, it contains multiple based classifiers. The based classifier of each layer is based on the residual of the training data of the based classifier of the previous layer. According to the residual of a layer, the gradient is calculated to fit the regression tree. Finally, using the principle of addition model, all the trained based classifier are added and integrated into the final decision. Compared to the traditional GBDT model, LightGBM improves the efficiency of training data and the accuracy of DTIs prediction.

3 Results

3.1 Performance analysis of drug target prediction based on combined multiple networks

In order to measure the DTIs prediction effects of different drugs and target data sources of different classes, pairwise combinations of different drug data and target data are conducted to calculate the DTIs prediction performance. If a type of network contains more than one, we have two ways to learn the features of nodes in the net-work: 1) Multiple networks are fused using SNF, and low-dimensional representations of nodes of the fused network are learned using DNGR; 2) Low-dimensional representations of nodes of each network are learned using DNGR, and then the features of nodes are spliced for multiple networks.

*

Considering that the category networks of drugs

(1)

(2) Fused networks that combine multiple networks in

FIGURE 2. Comparison of DTI prediction accuracy (AUROC) under different drug and target data combinations. It describes the DTIs prediction of six categories of drugs and four categories of targets combinations. (A) The DTIs prediction of drugs

Therefore, in the subsequent analysis, fusion and splicing methods are used for

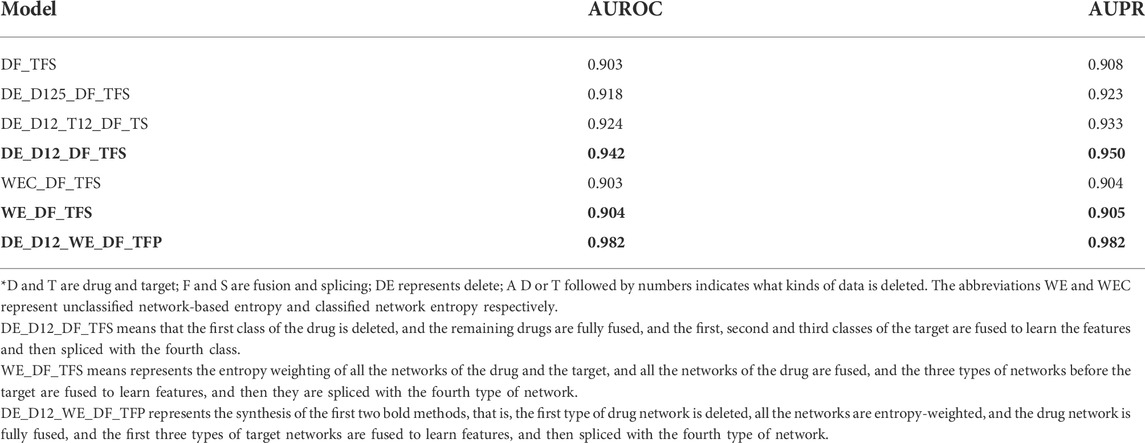

3.2 Comparison of drug target interactions prediction performance under different fusion methods

Through the comprehensive analysis of Figure 2, we can see that the AUROC is lower based on

According to the above results, we complete network fusion with different strategies. For high noise data, different filtering or weighting strategies are used and ablation experiments are performed. Then low-dimensional feature vectors of drugs and targets are learned based on DNGR. Finally, LightGBM was used to obtain a good prediction effect based on selective and weighted strategy, that is, AUROC and AUPR were 0.982.

3.2.1 Selective fusion

To reduce the effect of high noise, we simply filter

TABLE 4. Prediction performance of selective fusion. For ease of description, abbreviations in the model are expressed as follows.

3.2.2 Weighted entropy fusion

Considering the fact that different data sources may provide different contributions to DTIs prediction, simple deletion may cause information loss, so a weighted fusion of different data sources is carried out. In weighted fusion, we use entropy to evaluate the weighted value of each network during fusion (see Materials and methods). For calculating the entropy of networks, we consider two cases: One is the unclassified networks, and the other is the classified networks. The unclassified networks calculate the entropy of each network by SoftMax, normalized all values of the entropy, and weighted every network before fusing. For the classified network, the difference is that the normalization is based on the classified networks, that is, two or more networks in the classified network contains have to be multiplied by the same weight value. We can see that there is little difference between the two methods of weighted fusion. However, compared with directly deleting the data with low predictive performance, the method based on weighted fusion is significantly lower than the method based on selective fusion.

3.2.3 Selective weighted fusion

Combining the advantages of selection and weighting strategies, a selective and weighted entropy fusion strategy is used. After deleting

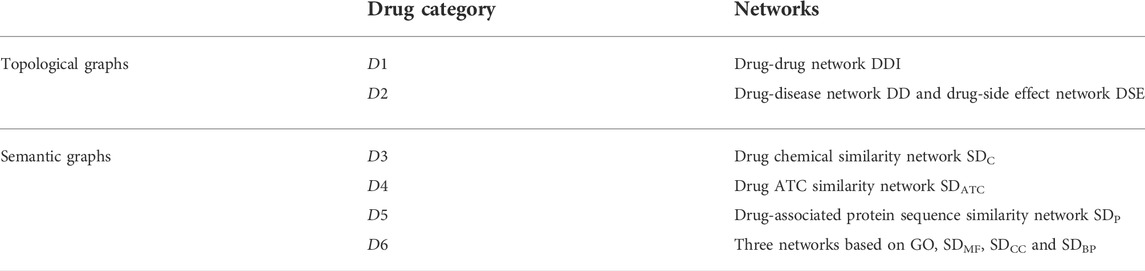

3.3 High performance of EFMSDTI

Based on the ablation experimental, the strategy of selective weighted fusion is used to predict DTIs, named EFMSDTI. To evaluate the performance of EFMSDTI, four previous state-of-the-art methods are used for comparison. In a 5-fold cross-validation, 20% of the positive and negative samples are randomly selected as the test set, and 80% of the drug-target pairs are used as the training set. As the Table 5, EFMSDTI, which has the highest AUROC and AUPR, outperforms four previous state-of-the-art methods: NEFTP, NeoDTI, deepDTnet, DTINet. A brief description of these methods is as follows:

3.3.1 NEFTP

A heterogeneous network embedding framework for predicting similarity-based drug-target interactions was performed, which builds a similarity network based on 15 heterogeneous information networks, and applies a random walk to extract the information of nodes in the network and learns low-dimensional vectors. Finally, the classifier predicts DTIs (An and Yu, 2021). It learns node features by treating the random walk paths of different networks equally, but the contributions of different networks are different.

3.3.2 NeoDTI

Integration of neighbor information from a heterogeneous network for discovering new drug-target interactions develop a new nonlinear end-to-end learning model (Wan et al., 2018). The model integrates various information from heterogeneous network data and automatically learns representations that preserve drug and target topologies to facilitate DTI prediction.It focuses on the topological information of drugs and targets, and the collection of feature information is not enough, only drug structure similarity and target sequence similarity. But the characteristic information of drug and target is not limited to these two.

3.3.3 deepDTnet

Target identification among known drugs by deep learning from heterogeneous networks (Zeng et al., 2020) was implemented, which collects 15 information networks to learn the feature vectors of each node in each network, and inputs the PU prediction model to predict DTIs after splicing 15 feature vectors. Similarly, the model treats multi-source data equally, but the contribution of each information network is different.

3.3.4 DTINet

A network integration approach for drug-target interaction prediction and computational drug repositioning from heterogeneous information was implemented, which integrates multi-network information and learns node features through compact feature learning algorithm, and finally inputs DTIs in PU learning. Although it integrates multi-network information, it does not consider the in-depth study of multi-network information fusion.

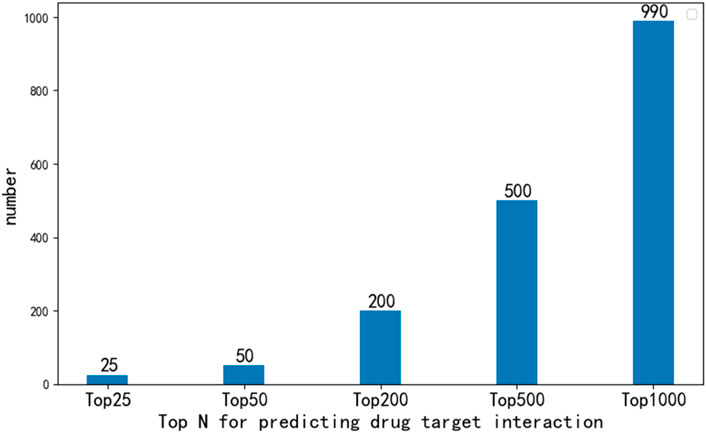

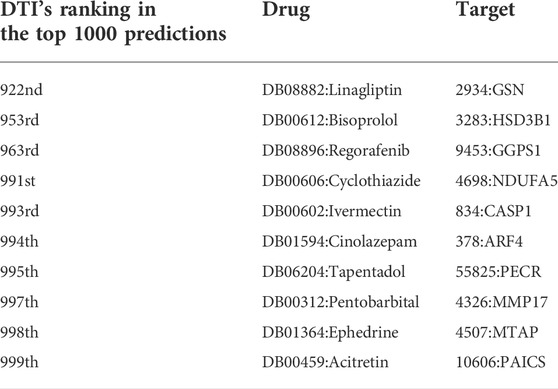

3.4 Validation of the top-ranked predictions

In order to further analyze the performance of EFMSDTI method to identify DTIs, the top-ranked predictions are verified. We select the top 1000 prediction DTIs for each fold, and merge the 5-folds by averaging. The top 1000 prediction DTIs are analyzed in our analysis. As shown in Figure 3, 990 of the top 1000 DTIs are known DTIs. The top 25, 50, 200 and 500 prediction results are known DTIs. Based on the predicted score of the model, the drug-target pairs that do not interact in known DTIs are considered to be novel DTIs according to rank of the predicted value in the top 1000 samples. Ten DTIs in the first 1000 prediction results that are not verified in Table 6.

There were 10 sets of drug-target interactions in the first 1000 prediction results that were not verified in Table 6. These DTIs are considered to be potential drug-target interaction. Diseases can be treated with certain drugs, and these drugs are related to the disease. We’re going to test it from different angles. Disease can be caused by the abnormal expression of certain proteins, so this protein is associated with disease. As a result, drugs and targets that share the same disease are thought to be more likely to interact (An and Yu, 2021). The pair of bisoprolol (drug) and HSD3B1 (target) was one of the novel DTIs identified. The HSD3B1 is related to Hypertensive disease and other diseases. Bisoprolol also appears to have effect on this disease: Hypertensive disease. There is also support for drug-target interactions in the database. Ivermectin and caspase-1 (CASP1) was one of the novel DTIs identified. The target prediction module of drug in CHEMBL database was confirmed to be related to caspase-1 (Bosc et al., 2019).

4 Discussion

By analyzing and comparing the results of several experiments, we continuously adjust and optimize the prediction model. The results are analyzed and explained, and the optimal model, named EFMSDTI, is obtained based on the currently used data set. The procedure of EFMSDTI is the selective weighted fusing data, extracting the low-dimensional features of drugs and targets, and predicting DTIs using the LightGBM framework. The AUROC value of our final prediction result reached 0.982, which has better performance than several state-of-the-art algorithms.

DTIs prediction requires more accurate analysis of multi-source data of drugs and targets. Multi-source data can improve more comprehensive information than a single data. However, at the same time, multiple data sources may also bring some noise, so the data processing of multiple-source data is essential. Therefore, considering the contribution of different data, an effective fusion method named EFMSDTI is proposed. The result of the comprehensive analysis shows a higher performance of EFMSDTI. Moreover, through the concept of class network, we also found a new angle of the fusion method. In this paper, we use the popular fusion strategies and entropy-based weighted method to improve the prediction accuracy. The multi-source data used in this paper included nine sources for the drugs and six for the targets. According to current studies (Wan et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2020), data sources for drugs and targets are not limited to this, such as drug-induced gene expression profiles, drug pathways profiles, and so on. In the future, more data sources for drugs and targets will be studied to complement the rich-ness of drugs and targets with multiple networks, and to further confirm our strategy’s robustness. The fused network uses the graph embedding method of DNGR to extract high-quality low-dimensional features in this paper. Currently, there are many other methods to extract features, which may also improve the model’s prediction accuracy.

In this paper, we manually decide the weighted measure according to the test result metric AUROC, which has certain empiricism and is not a perfect weighting for the results. At present, the most popular mechanism is called attention mechanism, which uses machine self-learning to adjust the weighted value of features during the learning process. The mechanism of self-learning by results will also be the content of future research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YZ conceived the idea and prepared the experimental data. MW and YZ debugged the code, conducted the experiments, interpreted the results and wrote and edited the manuscript. SW and WC advised the study and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61902430, 61873281, 61972226).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following teachers for their guidance and help in writing the manuscript and completing the experiment. At the same time, many thanks to editors and reviewers for their suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022.1009996/full#supplementary-material

References

Abbasi, K., Razzaghi, P., Poso, A., Ghanbari-Ara, S., and Masoudi-Nejad, A. (2020). Deep learning in drug target interaction prediction: Current and future perspectives. Curr. Med. Chem. 28, 2100–2113. doi:10.2174/0929867327666200907141016

An, Q., and Yu, L. (2021). A heterogeneous network embedding framework for predicting similarity-based drug-target interactions. Brief. Bioinform. 22, bbab275. doi:10.1093/bib/bbab275

Avorn, J. (2015). The $2.6 billion pill--methodologic and policy considerations. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 1877–1879. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1500848

Bagherian, M., Sabeti, E., Wang, K., Sartor, M. A., Nikolovska-Coleska, Z., and Najarian, K. (2021). Machine learning approaches and databases for prediction of drug-target interaction: A survey paper. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 247–269. doi:10.1093/bib/bbz157

Bleakley, K., and Yamanishi, Y. (2009). Supervised prediction of drug-target interactions using bipartite local models. Bioinformatics 25, 2397–2403. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp433

Bosc, N., Atkinson, F., Felix, E., Gaulton, A., Hersey, A., and Leach, A. R. (2019). Large scale comparison of QSAR and conformal prediction methods and their applications in drug discovery. J. Cheminform. 11, 4–16. doi:10.1186/s13321-018-0325-4

Bullinaria, J. A., and Levy, J. P. (2007). Extracting semantic representations from word co-occurrence statistics: A computational study. Behav. Res. Methods 39 (3), 510–526. doi:10.3758/bf03193020

Buza, K., and Peška, L. (2017). Drug–target interaction prediction with Bipartite Local Models and hubness-aware regression. Neurocomputing 260, 284–293. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2017.04.055

Cheng, F., Desai, R. J., Handy, D. E., Wang, R., Loscalzo, J., Barabasi, A. L., et al. (2018). Network-based approach to prediction and population-based validation of in silico drug repurposing. Nat. Commun. 9, 2691–2712. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05116-5

Cheng, F., Li, W., Wu, Z., Wang, X., Zhang, C., Li, J., et al. (2013). Prediction of polypharmacological profiles of drugs by the integration of chemical, side effect, and therapeutic space. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 53, 753–762. doi:10.1021/ci400010x

Chu, Y., Kaushik, A. C., Wang, X., Wang, W., Zhang, Y., Shan, X., et al. (2021). DTI-CDF: A cascade deep forest model towards the prediction of drug-target interactions based on hybrid features. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 451–462. doi:10.1093/bib/bbz152

Ezzat, A., Wu, M., Li, X. L., and Kwoh, C. K. (2019). Computational prediction of drug-target interactions using chemogenomic approaches: An empirical survey. Brief. Bioinform. 20, 1337–1357. doi:10.1093/bib/bby002

Friedman, J. H. (2001). Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232. doi:10.1214/aos/1013203451

Gaulton, A., Bellis, L. J., Bento, A. P., Chambers, J., Davies, M., Hersey, A., et al. (2012). ChEMBL: A large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1100–D1107. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr777

Hernandez-Boussard, T., Whirl-Carrillo, M., Hebert, J. M., Gong, L., Owen, R., Gong, M., et al. (2008). The pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics knowledge base: Accentuating the knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D913–D918. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm1009

Keiser, M. J., Roth, B. L., Armbruster, B. N., Ernsberger, P., Irwin, J. J., and Shoichet, B. K. (2007). Relating protein pharmacology by ligand chemistry. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 197–206. doi:10.1038/nbt1284

Li, J., Zheng, S., Chen, B., Butte, A. J., Swamidass, S. J., and Lu, Z. (2016). A survey of current trends in computational drug repositioning. Brief. Bioinform. 17, 2–12. doi:10.1093/bib/bbv020

Liu, J., Lian, X., Liu, F., Yan, X., Shi, Z., Cheng, L., et al. (2019). Identification of novel key targets and candidate drugs in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Curr. Bioinform. 14, 328–337. doi:10.2174/1574893614666191127101836

Liu, T., Lin, Y., Wen, X., Jorissen, R. N., and Gilson, M. K. (2007). BindingDB: A web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D198–D201. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl999

Luo, Y., Zhao, X., Zhou, J., Yang, J., Zhang, Y., Kuang, W., et al. (2017). A network integration approach for drug-target interaction prediction and computational drug repositioning from heterogeneous information. Nat. Commun. 8, 573. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00680-8

Olayan, R. S., Ashoor, H., and Bajic, V. B. (2018). Ddr: Efficient computational method to predict drug-target interactions using graph mining and machine learning approaches. Bioinformatics 34, 1164–1173. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btx731

Pawson, A. J., Sharman, J. L., Benson, H. E., Faccenda, E., Alexander, S. P., Buneman, O. P., et al. (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: An expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D1098–D1106. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1143

Qi, M. (2017). LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 3149–3157. doi:10.5555/3294996.3295074

Shaosheng, C., Lu, W., and Xu, Q. (2016). Deep neural networks for learning graph representations. national conference on artificial intelligence. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 30 (1), 1145–1152. doi:10.1609/aaai.v30i1.10179

Smith, T. F., and Waterman, M. S. (1981). Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 147, 195–197. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5

Sousa, S. F., Fernandes, P. A., and Ramos, M. J. (2006). Protein-ligand docking: Current status and future challenges. Proteins 65, 15–26. doi:10.1002/prot.21082

Tang, C., Zhong, C., Chen, D., and Wang, J. (2020). Drug-target interactions prediction using marginalized denoising model on heterogeneous networks. BMC Bioinforma. 21, 330. doi:10.1186/s12859-020-03662-8

Tao, S., Xz, A., Mao, D. B., Rp, C., Sw, A., and Gan, W. A. (2022). DeepFusion: A deep learning based multi-scale feature fusion method for predicting drug-target interactions. Methods 204, 269–277. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2022.02.007

Wan, F., Hong, L., Xiao, A., Tao, J., and Zeng, J. (2018). NeoDTI: Neural integration of neighbor information from a heterogeneous network for discovering new drug-target interactions. Bioinformatics 35, 104–111. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty543

Wang, B., Mezlini, A. M., Demir, F., Fiume, M., Tu, Z., Brudno, M., et al. (2014). Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nat. Methods 11, 333–337. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2810

Wang, G., Zhang, X., Pan, Z., Rodriguez Paton, A., Wang, S., Song, T., et al. (2022). Multi-TransDTI: Transformer for drug-target interaction prediction based on simple universal dictionaries with multi-view strategy. Biomolecules 12, 644. doi:10.3390/biom12050644

Wang, J. Z., Du, Z., Payattakool, R., Yu, P. S., and Chen, C. F. (2007). A new method to measure the semantic similarity of GO terms. Bioinformatics 23, 1274–1281. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm087

Wang, X., Zhu, M., Bo, D., Cui, P., Shi, C., and Pei, J. (2020) Adaptive multi-channel graph convolutional networks, arXiv. 1243–1253.

Wang, Y. B., You, Z. H., Yang, S., Yi, H. C., Chen, Z. H., and Zheng, K. (2020). A deep learning-based method for drug-target interaction prediction based on long short-term memory neural network. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 20, 49. doi:10.1186/s12911-020-1052-0

Whitebread, S., Hamon, J., Bojanic, D., and Urban, L. (2005). Keynote review: In vitro safety pharmacology profiling: An essential tool for successful drug development. Drug Discov. Today 10, 1421–1433. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03632-9

Wishart, D. S., Feunang, Y. D., Guo, A. C., Lo, E. J., Marcu, A., Grant, J. R., et al. (2017). DrugBank 5.0: A major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1074–D1082. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx1037

Yan, X. Y., Yin, P. W., Wu, X. M., and Han, J. X. (2021). Prediction of the drug-drug interaction types with the unified embedding features from drug similarity networks. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 794205. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.794205

Yan, X. Y., Zhang, S. W., and He, C. R. (2019). Prediction of drug-target interaction by integrating diverse heterogeneous information source with multiple kernel learning and clustering methods. Comput. Biol. Chem. 78, 460–467. doi:10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.11.028

Yang, H., Qin, C., Li, Y. H., Tao, L., Zhou, J., Yu, C. Y., et al. (2016). Therapeutic target database update 2016: Enriched resource for bench to clinical drug target and targeted pathway information. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D1069–D1074. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv1230

Zeng, X., Zhu, S., Liu, X., Zhou, Y., Nussinov, R., and Cheng, F. (2019). deepDR: a network-based deep learning approach to in silico drug repositioning. Bioinformatics 35, 5191–5198. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz418

Zeng, X., Zhu, S., Lu, W., Liu, Z., Huang, J., Zhou, Y., et al. (2020). Target identification among known drugs by deep learning from heterogeneous networks. Chem. Sci. 11, 1775–1797. doi:10.1039/c9sc04336e

Zhao, X., Chen, L., and Lu, J. (2018). A similarity-based method for prediction of drug side effects with heterogeneous information. Math. Biosci. 306, 136–144. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2018.09.010

Zhu, S., Yasushi, O., Gozoh, T., and Hiroshi, M. (2005). A probabilistic model for mining implicit 'chemical compound–gene' relations from literature. Bioinformatics 2, ii245–ii251. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1141

Keywords: drug-target prediction, multi-source data, topology and semantic graph, similarity network fusion, selective and weighted fusion

Citation: Zhang Y, Wu M, Wang S and Chen W (2022) EFMSDTI: Drug-target interaction prediction based on an efficient fusion of multi-source data. Front. Pharmacol. 13:1009996. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1009996

Received: 02 August 2022; Accepted: 29 August 2022;

Published: 23 September 2022.

Edited by:

Xun Wang, China University of Petroleum, Huadong, ChinaReviewed by:

Yansen Su, Anhui University, ChinaJin-Xing Liu, Qufu Normal University, China

Xiao-Ying Yan, Xi’an Shiyou University, China

Copyright © 2022 Zhang, Wu, Wang and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuanyuan Zhang, eXl6aGFuZzEyMTdAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Yuanyuan Zhang

Yuanyuan Zhang Mengjie Wu

Mengjie Wu Shudong Wang

Shudong Wang Wei Chen1

Wei Chen1