- 1The Graduate School, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

- 2Biology Department, School of Health Science Professions, St. Dominic College of Asia, City of Bacoor, Philippines

- 3Department of Plant Systematics, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany

- 4College of Science and Research Center for the Natural and Applied Sciences, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

The Panay Bukidnon is a group of indigenous peoples living in the interior highlands of Panay Island in Western Visayas, Philippines. Little is known about their ethnobotanical knowledge due to limited written records, and no recent research has been conducted on the medicinal plants they used in ethnomedicine. This study aims to document the medicinal plants used by the indigenous Panay Bukidnon in Lambunao, Iloilo, Panay Island. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 75 key informants from June 2020 to September 2021 to determine the therapeutic use of medicinal plants in traditional medicine. A total of 131 medicinal plant species distributed in 121 genera and 57 families were used to address 91 diseases in 16 different uses or disease categories. The family Fabaceae was best represented with 13 species, followed by Lamiaceae with nine species and Poaceae with eight species. The leaf was the most frequently used plant part and decoction was the most preferred form of preparation. To evaluate the plant importance, use value (UV), relative frequency citation (RFC), relative important index (RI), informant consensus factor (ICF), and fidelity level (FL) were used. Curcuma longa L. had the highest UV (0.79), Artemisia vulgaris L. had the highest RFC value (0.57), and Annona muricata L. had the highest RI value (0.88). Diseases and symptoms or signs involving the respiratory system and injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes recorded the highest ICF value (0.80). Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC. and Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M. King & H. Rob were the most relevant and agreed species for the former and latter disease categories, respectively. C. odorata had the highest FL value (100%) and was the most preferred medicinal plant used for cuts and wounds. The results of this study serve as a medium for preserving cultural heritage, ethnopharmacological bases for further drug research and discovery, and preserving biological diversity.

Introduction

About 370–500 million indigenous peoples live in 90 countries worldwide, making up 5% of the global population. They represent 5,000 distinct and diverse cultures, but they also account for 15% of the extremely poor and deprived communities from social services and economic resources (United Nations Development Programme, 2019).

In the Philippines, there are 110 ethnolinguistic groups with more than 14 million people spread across the archipelago, with the highest population in Mindanao (63%), followed by Luzon (32%) and Visayas (3%) (National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, 2011), who occupy around 13 million hectares (ha) (45%) of the national land territory (National Economic Development Agency, 2017). The Bukidnon is the major indigenous group in the Central and Western Visayas in terms of population size, followed by the Ati/Ata (Negritoes). In Panay Island in Western Visayas, the Bukidnon population is about 112,000. The province of Iloilo is one of the four provinces in Panay Island, together with Aklan, Antique, and Capiz. It has the highest Bukidnon population with 62,245 individuals (National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, 2019). Bukidnon, which literally translates to the “mountain people,” were once coastal dwellers, but due to the piratical raids from Mindanao and political suppressions during the reign of the Spanish government, they moved to the hinterlands of the island (Magos, 2004). This was depicted in their epic tradition of chanting called Sugidanon (Magos, 1999). To distinguish the Bukidnon in Panay from the other Bukidnon groups in Mindanao, Negros, and other neighboring islands, the “Panay” is added (Gowey, 2016). Other authors used Mundo (Beyer, 1917), Monteses “mountaineer” (Ealdama, 1938), Sulod or Sulodnon “enclosed by the mountains” (Jocano, 1968; German, 2010), Tumandok “native of the place” (Talledo, 2004), and Bukidnon (Smith, 1915; Magos, 1999) to designate the Panay Bukidnon people.

The Panay Bukidnon primarily utilized the forest resources, rivers, and streams for their food and livelihood. They also engaged in slash and burn farming and building boats to transport their goods to the lowlands. In the 1970s, when logging activities were prohibited by the Philippine government, they shifted to other means of living, including farming various crops (Magos, 1999). Their social organization is relatively similar to the lowlanders. Their community membership pattern is composed of the baylan/babaylan, mirku (herb doctor), parangkutun (advisor), and the husay (arbiter). The baylan is considered the most important status in society and regarded with high respect. The baylan is the one who communicates with the spiritual world, interprets dreams, and handles religious performances. He or she may also administer herb medicine to the sick and practice folk medicine and physical therapy. Their language is Kiniray-a, a dialect that is similar to Ilonggo/Hiligaynon. Today the Panay Bukidnon settled in the interior “barangays” (villages) of at least 24 municipalities of the four provinces of Panay (Provincial Planning Development Office, 2018; National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, 2020) and most of their communities are located in the mountainous areas of the Central Panay Mountain Range.

Iloilo province is situated in the southeastern part of Panay Island in Western Visayas. It is geographically located at the center of the archipelago, and it is known as the “Heart of the Philippines.” Its excellent port facility and strategic location made the province the center of trade during the 1890s when the sugar industry was booming and it was once given the title of “Queen City of the South.” It is also known for the “Dinagyang Festival,” one of the most spectacular religious and cultural celebrations in the country in honor of Senior Sto. Nino (Child Jesus) (Province of Iloilo, 2015). The province has a total land area of 491,940 ha, 24% of which is classified as forestland, while 76% is classified as alienable and disposable land (Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 2019).

Several ethnobotanical surveys in Panay Island have been conducted on the Ati (Negritoes) indigenous groups (Madulid et al., 1989; Ong and Kim, 2015; Cordero et al., 2020; Cordero and Alejandro, 2021), but there is no study focused exhaustively on the medicinal plants used by the Panay Bukidnon in ethnomedicine. Nevertheless, several plants were listed with medicinal purposes in the anthropological case studies documented in the interior barangays of Tapaz, Capiz in Central Panay in 1945–1959 (Jocano, 1968). Given the absence of recent research about the ethnobotanical knowledge of Panay Bukidnon, it is therefore urgent to document this indigenous knowledge before it is forgotten. The documentation of traditional knowledge will serve as a medium for preserving cultural heritage, ethnopharmacological bases of drug research and discovery, and preserving biological diversity. Thus, this study is the first attempt to extensively survey the ethnobotanical knowledge in one of the indigenous Panay Bukidnon communities in the province of Iloilo in Panay Island, Western Visayas, Philippines.

Materials and Methods

Study Area and Permits

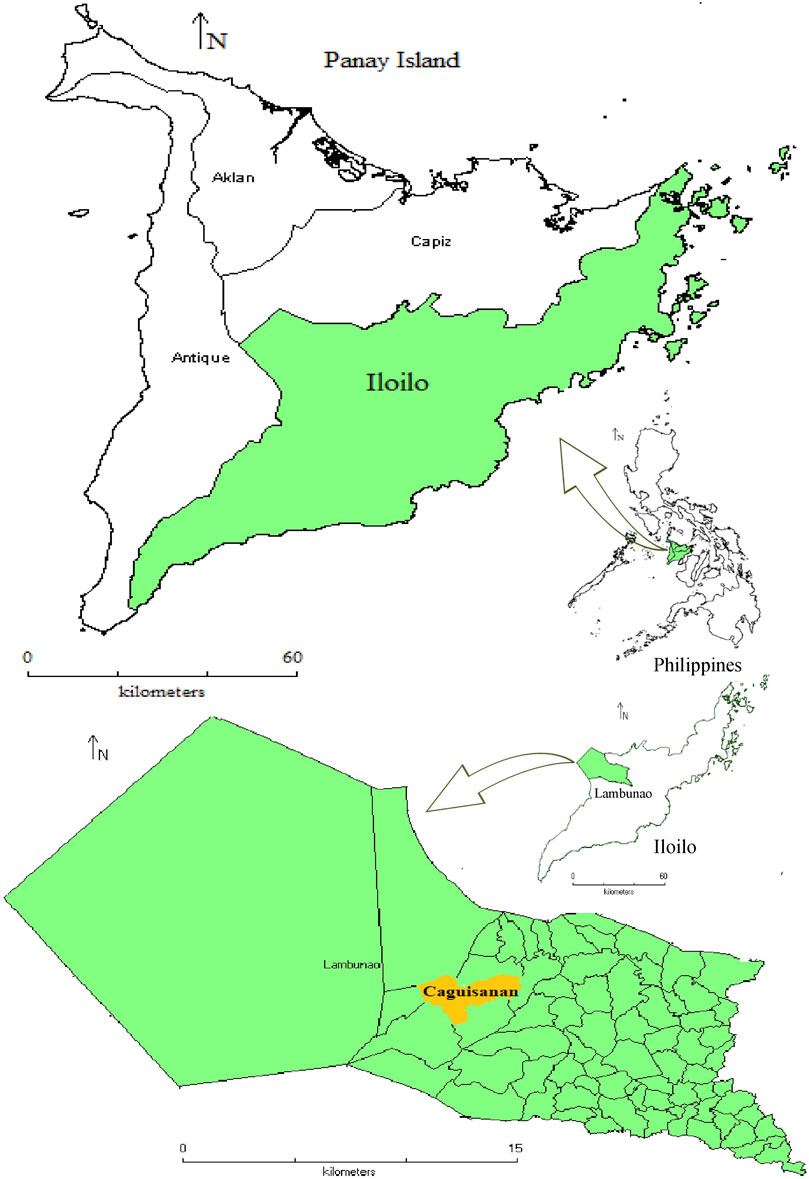

The town of Lambunao is a first-class municipality in the third district of Iloilo province, with a population of 81,236 individuals as of May 2020 (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2021). It is the largest municipality in the province in terms of land area (40, 709 ha), about 26.12% of which are forestlands, and the rest are alienable and disposable land. It is bounded by the municipalities of Calinog in the North, Duenas and Pototan in the East, Janiuay and Badiangan in the South, and Janiuay and Valderrama, Antique, in the west (Figure 1). It is a mountainous municipality and has the highest elevation (194 m a.s.l.) in the province. The climate of the area has two pronounced seasons: dry from the months of November to April and wet for the rest of the year. Seven out of its 73 barangays are inhabited by the Panay Bukidnon people. Brgy. Caguisanan, which lies between 11°05′37.6″N and 11°04′42.3″N latitude and 122°24′26.6″E 122°26′51.6″E longitude, has a land area of about 5.20 km2. According to the recent survey, it is one of the seven indigenous Panay Bukidnon barangays with a population of 1,842 in 394 households. The main source of livelihood in the barangay is farming of various crops such as rice, banana, corn, and other vegetables. Some of the younger generations are professionals working in various private and government sectors and some are working as overseas Filipino workers abroad. The landscape of the study site is dominated by hills and mountains with scattered rice terraces, grasslands, and patch forests.

Certification Precondition was acquired from the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP)-Region VI/VII and the researchers have satisfactorily complied with the requirements for securing the Indigenous Knowledge and Systems Practices (IKSPs) and Customary Laws (CLs). It was issued in compliance with Section 59 of the Republic Act No. 8371 “The Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) of 1997.” Several meetings were conducted: Pre-FPIC (Free and Prior Informed Consent) Conference; Disclosure Conference with the Indigenous Peoples (IP) Community and Presentation of Application; Community Decision Meeting; Memorandum of Agreement Preparation and Signing; and Output Validation Meeting. A Wildlife Gratuitous Permit was issued by the Department of Natural Resources Region (DENR) VI before conducting the study.

Data Collection

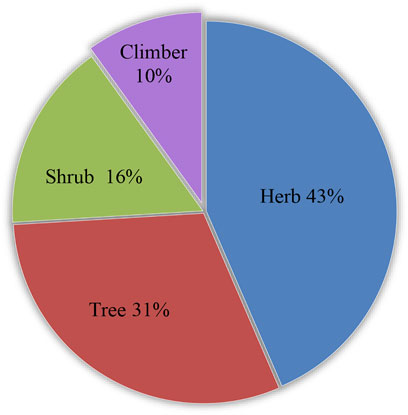

Fieldworks and interviews were conducted from June 2020 to September 2021. Interviews were carried out using semi-structured questionnaires, ethically reviewed, and approved (Supplementary Material S1). A purposive sampling technique was used, and the principal key informants were determined during the community decision meeting in the presence of the NCIP officers, barangay officials, IP leader, and council of elders. The informants were composed of the tribal leader, council of elders, herb doctors (mirku/surhano/albularyo), midwife (paltera), and other members of the community who have indigenous knowledge of using medicinal plants in treating and addressing health problems and conditions. A total of 75 informants, 31 males and 44 females, aged between 24 and 89 years old, were interviewed at their own convenience in their community during the study. Questions regarding personal information and the medicinal plants they used when they experienced any health-related problems were asked during the surveys. The information about the demographic profile of the participants, such as age, gender, civil status, educational attainment, and occupation, is shown in Table 1. The plant part used, mode of preparation, and administration were also recorded during the interviews. A focus group discussion was conducted with the 10 members of the council of elders to verify the acquired data among the informants during the output validation meeting. The meeting was facilitated by the NCIP officers, IP leader, and Brgy. Captain.

Plant Collection and Identification

Collecting medicinal plant samples was carried out with the help of the informants, if available in their immediate surroundings or their home gardens right after the interview. Some field collections were assisted by the informants who have the knowledge of the location of some plants that were not available in the home gardens. Plants were also photographed for documentation purposes. Voucher specimens were prepared using three to five branches with preferably reproductive parts (flowers and fruits), inserted in newspapers, and positioned in a way that best represents the plant in the wild. The plants were poisoned with a generous amount of denatured alcohol in polyethylene bags. Poisoned specimens were then transferred to a new newspaper and placed in a presser. Pressed and dried plant specimens were then mounted on herbarium sheets with proper documentation labels. Voucher specimens were accessioned and deposited in the Herbarium of the Northwestern University Luzon (HNUL). Identification of the collected medicinal plants was made using different online databases such as Co’s Digital Flora of the Philippines, (https://www.philippineplants.org/), Phytoimages (http://www.phytoimages.siu.edu), Stuartxchange (http://www.stuartxchange.org/), and Plants of the World Online (http://plantsoftheworldonline.org/), then verified by Mr. Danilo Tandang, a botanist at the Philippine National Museum Herbarium and Mr. Michael Calaramo of the Herbarium of Northwestern University Luzon (HNUL). For the validation of the family and scientific names, Tropicos (Tropicos, 2021), World Flora Online (World Flora Online, 2021), and International Plant Names Index (International Plant Names Index, 2021) were used. To identify the geographical distribution and endemicity of the medicinal plants, Co’s Digital Flora of the Philippines (Pelser et al., 2011) and Plants of the World Online (Plants of the World Online, 2021) were used.

Data Analyses

There were five values used to quantify the plant importance: use value (UV), relative frequency of citation (RFC), relative importance index (RI), informant consensus factor (ICF), and fidelity level (FL). The UV was calculated to determine the relative importance of the medicinal plant species using the following formula:

Results

Medicinal Plants Characteristics

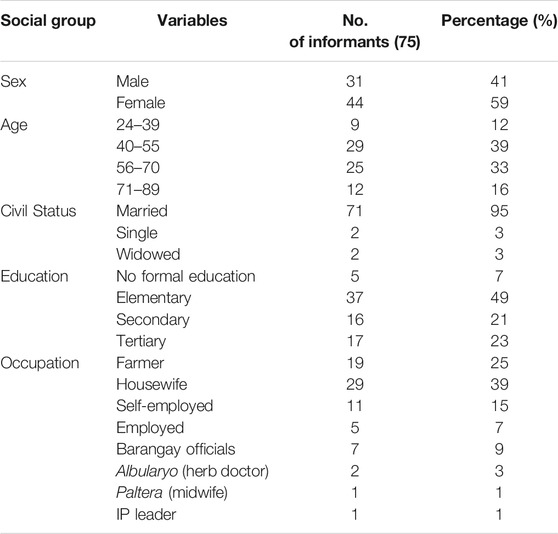

The present study documented a total of 131 medicinal plant species distributed in 121 genera and 57 families. The family Fabaceae was best represented with 13 species, followed by Lamiaceae with nine species and Poaceae with eight species (Figure 2). Fabaceae are used to treat 28 diseases in 13 different use or disease categories, Lamiaceae in 24 diseases in ten disease categories, and Poaceae in 21 diseases in 12 disease categories.

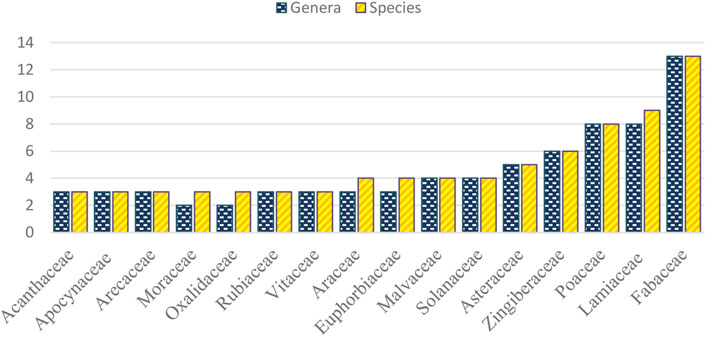

The medicinal plants recorded possess different growth forms such as herbs (43%), trees (31%), shrubs (16%), and climbers (10%) (Figure 3). The plants were collected within the vicinity of the barangay mostly cultivated in the informant’s home gardens or backyards that serve as ornamentals and vegetables and used for medicinal purposes; some were cultivated as crops in the farmland; some were grown on the riverbanks and forest; others do grow as weeds pervasively around the community. Of all the 131 medicinal plants listed, 91 species were collected as cultivated plants and 40 species were collected in the wild. Out of 127 plants identified up to the species level, 78 species are not native (introduced, naturalized, cultivated) in the Philippines and 49 species are native. Three species (Areca catechu L., Musa textilis Née, and Mussaenda philippica A. Rich.) of the native plants are considered endemic and their occurrence is widespread in the country. Information about the plant growth habit, collection sites, and geographical distribution and endemicity are found in = Supplementary Table S1.

The medicinal plant details are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. The scientific, local, and family names are also listed along with the plant part used, disease or purpose, quantity, mode of preparation, the form of administration, adverse or side effects, use value, relative frequency citation, and relative importance index.

Plant Part Used and Mode of Preparation and Administration

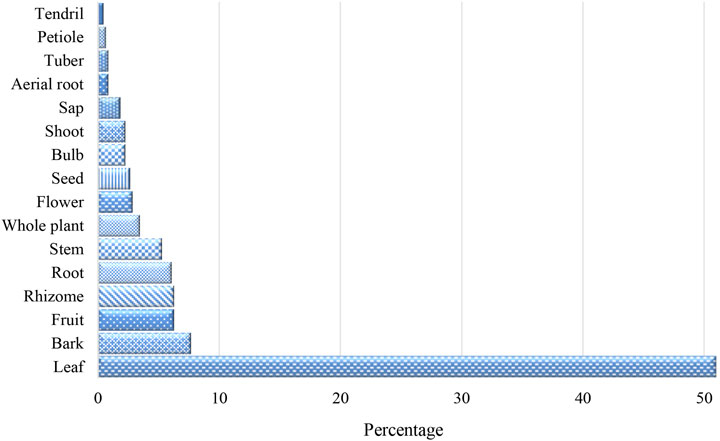

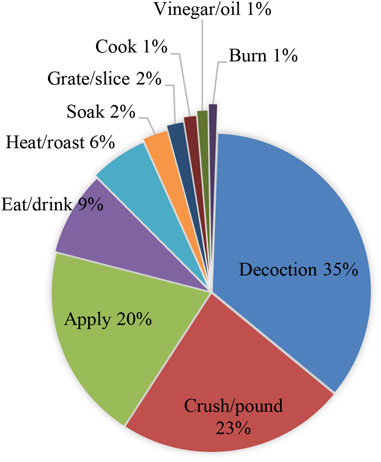

Sixteen different medicinal plant parts were used to address 94 diseases and health-related conditions documented in this study. The most frequently used plant parts for the preparation of the remedy were leaf (51%), followed by bark (8%), fruit (6%), and rhizome (6%) (Figure 4). Root, stem, whole plant, flower, seed, bulb, shoot, sap, and aerial root were also used but less frequently. The least utilized plant parts were tuber, petiole, and tendril. There were ten different ways to prepare the medicinal plants and the most common forms were decoction (35%), followed by crushing or pounding (23%) and direct application (20%) (Figure 5). Eat/chew/drink, heat/roast, soak in water, and grate/slice were also practiced. The least forms of preparation were cooking, processing into vinegar or oil, and burning for smoke or ash. The plant parts used and the mode of preparation of the medicinal plants depend on the ailments to be addressed and to whom they will be administered. Occasionally, some of the preparations include animal parts and products such as blood, egg, beeswax (kabulay), slaked lime (apog), minerals like salt, and chemicals like kerosene but in minute amounts. Sugar or breastmilk was also added to reduce or mask the bitterness of plant extracts to be taken orally by infants and children.

More than half of the medicinal plant preparations (52%) recorded were administered externally or topically by applying plant parts directly on the body, rubbing plant extracts, bathing, and burning for smoke and ash. The rest were taken orally (48%) by drinking decoction, eating, chewing, drinking extracts or liquids and used as a mouthwash.

Quantity and Dosage

The quantity of the medicinal plants used is influenced by the guided cultural and religious beliefs of the Panay Bukidnon and should be prepared or administered in odd numbers (3, 5, or 7). For example, in treating headaches, three different medicinal plants such as Pseuderanthemum carruthersii (Seem.) Guillaumin (3, 5, or 7 leaves depending on the leaf size), Curcuma longa L. (7 thinly sliced rhizomes), and Zingiber officinale Roscoe (7 thinly sliced rhizomes) were applied on the forehead. The frequency of the administration was dependent on the disease to be treated. For decoction, it was often administered by drinking a full glass to be taken twice or thrice a day or as a replacement for water intake. The detailed quantity and frequency of administration of medicinal plants are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Use Value and Relative Frequency of Citation

The use value was used to evaluate the relative importance of the medicinal plants: high values indicate high use report, while relative frequency citation determined the usefulness of the plant by high FC or being mentioned by all the informants.

The top three medicinal plants with the highest use value were Curcuma longa L. (0.79), Blumea balsamifera (L.) DC. (0.64), and Artemisia vulgaris L. (0.59) (Table 2). C. longa is used to treat 13 diseases in nine disease categories and recorded a high use report in suppressing fever, headache, and sinda. It is usually prepared with two or four medicinal plants. The preparation and mode of administration for headache and fever were the same and with few modifications for sinda. C. longa is also used for muscle pain, stomachache, bloated stomach, tooth decay, typhus, typhoid fever, memory loss, cancer, cuts/wounds, and tetanus. It is cultivated in the informant’s home gardens for medicinal purposes.

B. balsamifera was used to treat nine conditions or purposes under eight different disease categories and is widely known to cure cough, used in postpartum care and recovery, and relieved headache. It is also used for muscle pain, bloated stomach/gas pain, goiter, urinary tract infection (UTI), vomiting blood, and inaswang. It was collected growing in the farmland, but some informants also cultivated it in their backyards.

A. vulgaris was used to treat seven ailments in six disease categories and is the best-known therapy for cough, fever, headache, and body pains. It is also used for the remedy of chest pain, fracture, and hearing problems. It is grown in the home gardens as medicinal plants for future use. Seven medicinal plants were recorded with only one use report and FC for each species: Cheilocostus speciosus (J.Koenig) C.D.Specht, Luffa aegyptiaca Mill., Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels, Lygodium circinnatum (Burm. f.) Sw., Solanum melongena L., Nauclea orientalis (L.) L., and Leea guineensis G. Don, which garnered the lowest value for UV (0.01) and RFC (0.01).

Medicinal plants with the highest RFC were Artemisia vulgaris (0.57), followed by Curcuma longa (0.47) and Blumea balsamifera (0.44) (Table 2). Out of the 75 informants who participated in the survey, A. vulgaris had the highest informant citation or FC.

Relative Importance Index

The RI was used to assess the relative importance of the medicinal plants by use or disease categories. A high value indicates that a particular medicinal plant species is most frequently cited as useful with a high number of use categories or having multiple uses. The top three plants with the highest RI values were Annona muricata L. (0.88), C. longa (0.87), and B. balsamifera (0.80) (Table 2). A. muricata is used in 11 different use or disease categories: diseases of the genitourinary system; neoplasms; diseases of the circulatory system and blood or blood-forming organs; endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases; diseases and symptoms or signs involving the respiratory system; diseases and symptoms or signs involving the nervous system; diseases and symptoms or signs involving the digestive system or abdomen; infectious and parasitic diseases; diseases and symptoms or signs involving the skin; diseases and symptoms or signs of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue; and other cultural uses. It is used to address 13 diseases or purposes and recorded the high use report in treating UTI, cancer, and hypertension by drinking the leaf decoction or soaking the young leaves in warm water and drink or by just eating a medium sliced fruit three times a day. A. muricata is also used for the remedy of high uric acid, pneumonia, dizziness, intestinal cleansing, kidney trouble, itchy throat, amoebiasis, lump, arthritis, and doklong. C. longa was used in nine categories: injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes; neoplasms; diseases and symptoms or signs involving the nervous system; general symptoms and signs; diseases and symptoms or signs involving the digestive system or abdomen; infectious and parasitic diseases; diseases and symptoms or signs of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue; mental or behavioral symptoms, signs, or clinical findings; other cultural uses. B. balsamifera is used in eight disease categories: diseases and symptoms or signs involving the digestive system or abdomen; endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases; diseases of the genitourinary system; diseases and symptoms or signs of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue; diseases and symptoms or signs involving the nervous system; diseases and symptoms or signs involving the respiratory system; pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium; other cultural uses. The top ten medicinal plants with the highest use value, relative frequency citation, and relative importance index are shown in Table 2.

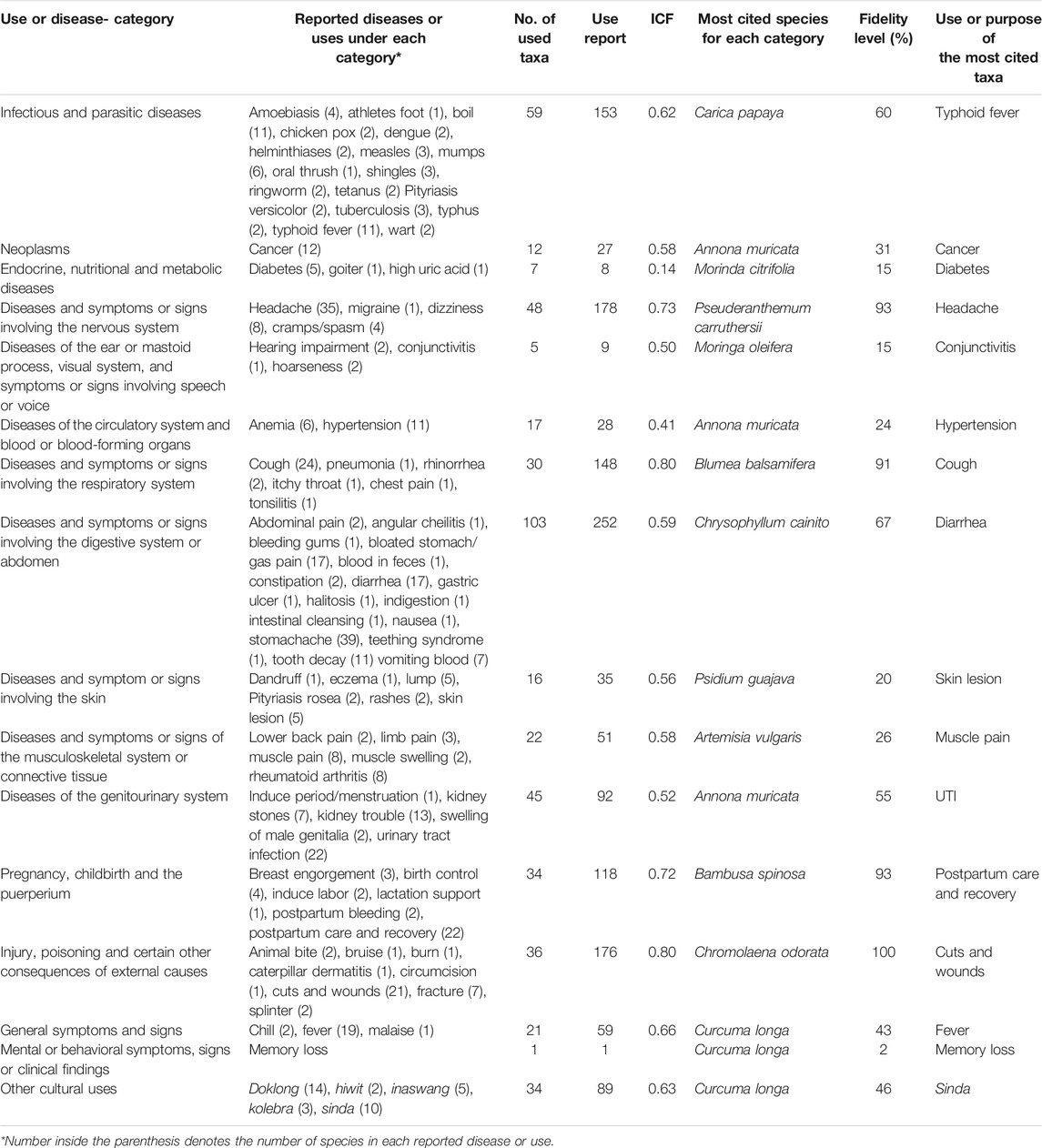

Informant Consensus Factor

There were 91 diseases and purposes in 16 different use or disease categories recorded in this study (Table 3). ICF was used to evaluate the consensus in the medicinal plant information among the informants. High ICF values indicate one or few medicinal plants mentioned by a high number of informants within a particular disease category, and low values indicate that more species are being used and the informants differ in their preference on which plant to use. The highest ICF value (0.80) was in the diseases and symptoms or signs involving the respiratory system and in injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes. The diseases and symptoms or signs involving the respiratory system were cough, pneumonia, rhinorrhea, itchy throat, chest pain, and tonsillitis. B. balsamifera had the highest use report within the category and was frequently used plant for treating cough by consuming the young leaves or by drinking leaf or root decoction or by rubbing leaf extract on the head of the afflicted ones. A high proportion of informants mentioned and agreed upon the use of B. balsamifera in treating cough within the category. Injuries, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes recorded, such as animal bite, bruise, burn, caterpillar dermatitis, circumcision, cuts and wounds, fracture, and splinter, were the reported purposes or medical uses. Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M.King & H. Rob. had the highest use report within the category and was the most preferred medicinal plant used to treat cuts/wounds by applying crushed leaves on the affected area. The next highest value was in the diseases and symptoms or signs involving the nervous system (0.73) with headache, migraine, and dizziness as the reported medical condition. Pseuderanthemum carruthersii had the highest use report and was widely used for treating headaches by applying leaves on the forehead alone or with C. longa and Z. officinale. The lowest ICF value was recorded in mental disorder (0.00) with memory loss as the reported condition and Curcuma longa was used for the treatment.

Fidelity Level

The FL was used to determine the relative importance of a medicinal plant within each category. Medicinal plants with the highest FL values were Chromolaena odorata (100%), Bambusa spinosa Roxb. (93%), and Pseuderanthemum carruthersii (93%) (Table 3). C. odorata is exclusively used to treat cuts and wounds and can be seen growing invasively along the paths and roadsides in the community. B. spinosa recorded the highest use report for postpartum care and recovery under the pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium category. It is preferably used and highly suggested by many informants for postpartum care and recovery therapy. Decoction of at least three up to ten different medicinal plants was used for drinking (1–2 glasses), body steaming, and bathing to be performed nine days after a mother gave birth. B. spinosa has also been used to treat cancer, UTI, and kidney stones but with only one citation recorded for each ailment P. carruthersii has the highest use report and is the most preferred medicinal plant for relieving headaches under the diseases and symptoms or signs involving the nervous system. The lowest FL value was recorded for C. longa in treating memory loss under the mental disorder category with only one informant mentioned for its curative effect.

Comparing Different Indices

Table 2 shows the top 10 medicinal plants with the highest UV, RFC, and RI values. High UV and RFC values indicate the high number of use reports and frequency citations (FC) from the informants, while high RI values consider the multiplicity of uses or the high number of uses in different disease categories. This implies that medicinal plants with high UV, RFC, and RI values are the most important and valued medicinal plants in the community. There are a few considerable differences in species ranking yielded by the three indices set out in Table 2. The ranks of the first three species (C. longa, Blumea balsamifera, and Artemisia vulgaris) are nearly the same in all indices except in RI where Annona muricata had the highest value but ranked 4th in UV and only 9th in RFC. C. longa, B. balsamifera, and A. vulgaris had the highest use reports and FC from the informants and only next to A. muricata in terms of multiple uses in different disease categories. A. muricata had the highest number of uses or purposes in different disease categories (11 disease categories); however, its use reports and FC are not quite as high as those of the first three species mentioned above. A. muricata is the most frequently used medicinal plant in a wide range of diseases (13 diseases). Another noticeable difference is the inclusion of Moringa oleifera Lam. and Carica papaya L. in the RI index, which are not shown in the top ten species with high UV and RFC values. M. oleifera ranks 12th in UV and 13th in RFC, while C. papaya ranks 17th in UV and 14th in RFC (values are not shown in Table 2 but available in Supplementary Table S2). Their UV and RFC values are not quite as high, but they have multiple uses in different disease categories. Low UV, RFC, and RI values indicate a low number of use reports, FC, and have one or few uses in disease categories. For example, Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) has low UV (0.04), RFC (0.03), and RI (0.07) values, indicates low use report (2) and FC (2 informants), and is only used in one disease category (diseases and symptoms or signs involving the digestive system or abdomen). This implies that A. paniculata is a less important and less preferred medicinal plant species in the Panay Bukidnon community. On the other hand, Table 3 shows the use or disease categories and ICF and FL values. High ICF values are considered the most culturally relevant medicinal plants and the agreement of its use within a disease category in the community, while FL highlights the most preferred species for a particular disease. Medicinal plants with the high ICF values were Blumea balsamifera (0.80), Chromolaena odorata (0.80), and Pseuderanthemum carruthersii (0.73) and these species are highly agreed upon by most informants for the therapy of diseases in their respective disease categories. Medicinal plants with high FL values were C. odorata (100%), P. carruthersii (93%), and Bambusa spinosa (93%) and these are the most preferred species to a particular disease in each disease category. Though B. spinosa is not included in the top medicinal plants with high UV, RFC, and RI values, its curative effect for postpartum care and recovery is preferred by a high proportion of informants. Medicinal plants with high UV, RFC, RI, ICF, and FL values are the most culturally important, relevant, preferred, and agreed on species in the Panay Bukidnon communities.

Cultural Important Medicinal Plants

Indigenous peoples are strongly tied with their spiritual beliefs and practices. Interestingly, up to date, the Panay Bukidnon still believe that some of the illnesses and diseases are caused by spirits, supernatural beings, and sorcery. Some diseases were mentioned that were caused by aswang (witch), hiwit (sorcery), sinda (charm of spirits) and some health conditions like doklong and kolebra with more complicated and sometimes unexplained symptoms. Sinda is a condition with symptoms like dizziness and fever caused by spirits or supernatural beings, while kolebra has symptoms like chills, stomachache, nausea, shortness of breath, and paleness. Doklong is somewhat similar to “relapse” and sometimes accompanied by other symptoms like headache, muscle pain, and weakness. For inaswang, five medicinal plants were recorded for the therapy and a cultivar of Alocasia is frequently used by applying the heated leaf to the stomach area. For the treatment of hiwit, a species of Amomum is used by rubbing the stem extract on the body or by crushing the stem with the inner bark of Pipturus arborescens (Link) C.B. Rob. and taking the extract orally. Curcuma longa is the most used medicinal plant used to cure sinda by rubbing the rhizome’s extract on the head or applying the sliced rhizome along with other plants on the forehead. Jatropha curcas L. is frequently used as a remedy for kolebra by drinking the extract of the inner bark and for doklong, drinking the leaf decoction of Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr. alone or with other medicinal plants is the most preferred.

Medicinal Plants Used to Strengthen Immunity Against Infection and for Potential COVID-19 Therapy

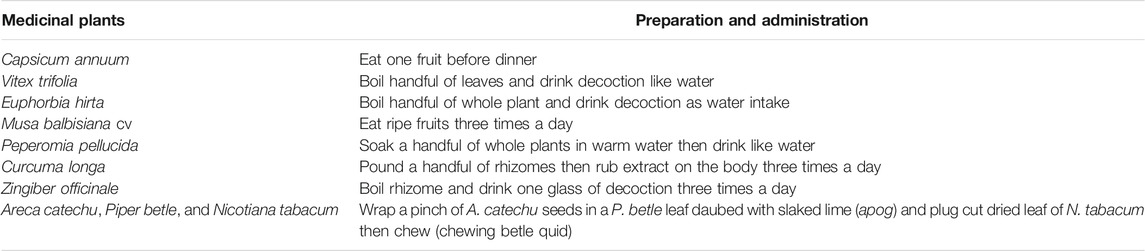

With the current situation of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in the country and the resurgences of the infection waves, communities in the far-flung areas tend to explore different medical plants as an alternative for potential therapy while waiting for the vaccine. There were ten medicinal plants mentioned by the council of elders that they used to boost their immunity against COVID-19 infection (Table 4). If someone is suspected of having a COVID-19 infection or exhibits symptoms related to COVID-19, they use the available medicinal plants (Table 2) available to alleviate their condition. Medicinal plants such as Curcuma longa, Zingiber officinale, Capsicum annuum L., and Peperomia pellucida (L.) Kunth are traditionally used by the Panay Bukidnon to treat fever, headache, cough, and body pains which were also the symptoms of COVID-19 and influenza. They also believed that chewing betel quid which is composed of Areca catechu L., Piper betle L., Nicotiana tabacum L., and slaked lime (apog) can help them fight the infection and help them feel substantially better.

Comparative Review of the Medicinal Plants With Other Ethnobotanical Studies

The anthropological study conducted in the Panay Bukidnon communities in the Province of Capiz in the 1950s recorded a total of 54 medicinal plant species and 21 of which are cited in this current ethnobotanical study. An additional 109 taxa were documented to the medicinal flora used by the Panay Bukidnon in Panay Island from this present study.

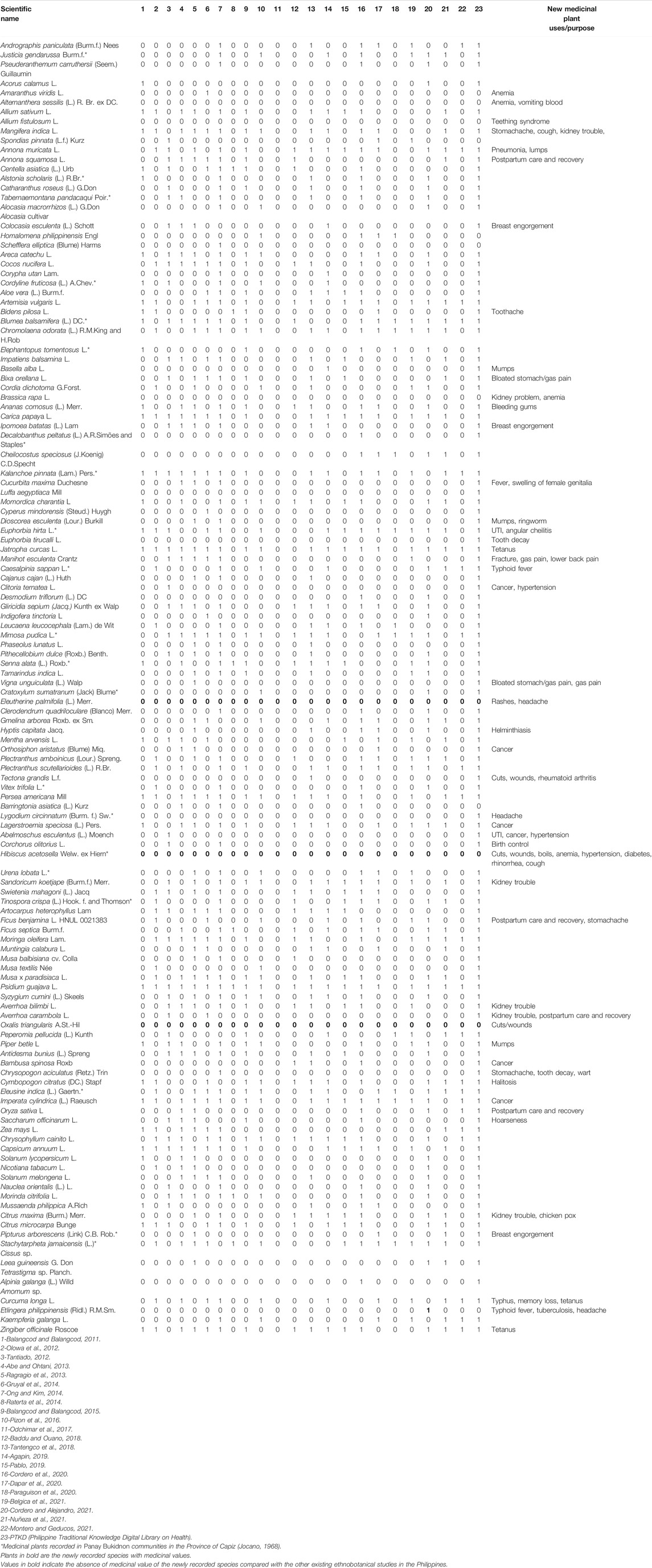

To identify the new medicinal plants and plant use, a comprehensive comparison was performed with 22 ethnobotanical studies published from 2011 up to the present and with one online database. Only the scientific names and their synonyms were used for the comparative review; local names were not considered because they are arbitrary within different cultures and dialects. Of the 127 medicinal plants identified up to the species level, three species (Eleutherine palmifolia (L.) Merr., Hibiscus acetosella Welw. ex Hiern, and Oxalis triangularis A.St.-Hil.) show some novel medicinal uses that were not documented in other existing ethnobotanical studies conducted in the country. These medicinal plant species are not native to the Philippines. E. palmifolia is used for the therapy of rashes and headaches. Its red bulb is the preferred plant part for the treatment. It is usually used as an ornamental plant grown in the home gardens and community center. H. acetosella is used to cure cuts/wounds, boils, anemia, hypertension, diabetes, rhinorrhea, and cough. Filipinos also used this medicinal plant as a vegetable and normally use it to “sour” the dishes. With its deep red-purple foliage, it is also served as an ornamental plant. O. triangularis is used to treat cuts/wounds by the Panay Bukidnon and serves as a hanging ornamental plant for its striking deep maroon trifoliate leaves. Forty-seven medicinal plants were recorded to have an additional therapeutic use or purpose not mentioned in the other previous ethnobotanical studies, while 80 species have the same medicinal values as mentioned in the existing literature. Some of the additional uses or purposes of the medicinal plants that are rarely listed in other studies are angular cheilitis, breast engorgement, and promoting teething in toddlers. The detailed information about the comparative review of the medicinal plants and the additional plant uses is shown in Table 5.

TABLE 5. Comparative presence-absence matrix of the medicinal plants used by the Panay Bukidnon with other ethnobotanical studies.

Discussion

The documentation of 131 medicinal plant species used in the indigenous health care practices showed the extensive usage of Panay Bukidnon ethnobotanical knowledge and indicative importance for their rich cultural heritage. The families of Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, and Poaceae were represented with a high number of medicinal plant species. Fabaceae as the most preferred medicinal plant family used by the Panay Bukidnon is parallel to the other folkloric studies conducted in Western Visayas (Madulid et al., 1989; Tantiado 2012; Ong and Kim, 2014; Cordero and Alejandro, 2021) and other indigenous communities in the country (Ragragio et al., 2013; Obico and Ragrario, 2014; Tangtengco et al., 2018; Pablo, 2019). Fabaceae is highly used by the Panay Bukidnon to treat infectious and parasitic diseases and diseases and symptoms or signs involving the digestive system or abdomen. The family constitutes phytochemicals that have antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and insecticidal activities (Wanda et al., 2015).

The use of leaves as the most preferred medicinal plant part to address medical conditions is comparable to other ethnobotanical surveys conducted throughout the archipelago (Balangcod and Balangcod, 2011; Olowa et al., 2012; Abe and Ohtani, 2013; Gruyal et al., 2014; Ong and Kim, 2014; Raterta et al., 2014; Balangcod and Balangcod, 2015; Pizon et al., 2016; Odchimar et al., 2017; Baddu and Ouano, 2018; Tantengco et al., 2018; Agapin, 2019; Pablo, 2019; Cordero et al., 2020; Dapar et al., 2020; Belgica et al., 2021; Cordero and Alejandro, 2021; Madjos and Ramos, 2021; Montero and Geducos, 2021; Nuñeza et al., 2021). As a tropical country, leaves are always available for most plant species at all seasons and are readily accessible in case of emergencies. The collection of leaves is more sustainable than gathering other plant parts such as barks and roots that can cause damaging effects and even mortality to a plant if harvested in large quantities. Leaves contain the highest secondary metabolites with an antimicrobial effect (Chanda and Kaneria, 2011), antioxidant property, antibiotic activity, and antidiabetic potential compared with other plant parts (Jain et al., 2019).

Decoction is the most common form of preparation and preferably to be taken orally and occasionally used for body steaming, bathing, and washing. It is also an evident form of preparation in other indigenous communities in the country (Balangcod and Balangcod, 2015; Pizon et al., 2016; Odchimar et al., 2017; Baddu and Ouano, 2018; Tantengco et al., 2018; Cordero et al., 2020; Cordero and Alejandro, 2021; Madjos and Ramos, 2021; Nuñeza et al., 2021). Decoction is done with the use of one medicinal plant species or in a combination of two or more. The Panay Bukidnon are culturally used to combine three, five, or seven (colloquially known as pito-pito) different medicinal plants for higher efficacy. Each plant constitutes phytochemical compounds and is sometimes present in small quantities and inadequate to achieve desirable therapeutic effects. To yield better results and effectiveness, the combination of different medicinal plants demonstrates the synergistic effects. Some bioactive chemicals work significantly when combined with other plants rather than used singly (Parasuraman et al., 2014).

Curcuma longa recorded the highest use value and is used as therapy for headache, fever, body pain, stomachache, bloated stomach, tooth decay, typhus, typhoid fever, anti-tetanus, memory loss, cancer, and sinda. The rhizome’s extract is usually used for the treatment. It is also used by other indigenous groups in the country for diarrhea, abdominal pain, flatulence, arthritis, and hypertension by the Higaonon tribe in Iligan City (Olowa et al., 2012); arthritis, cough, and cuts and wounds by the Ivatan tribe in Batan Island (Abe and Ohtani, 2013); fever, burn, dizziness, and abdominal pain by the Ati tribe in Guimaras Island (Ong and Kim, 2014); arthritis by the Subanen tribe in Zamboanga del Sur (Pizon et al., 2016); flatulence, headache, numbness, rheumatism, stomachache, and vomiting by the Aetas tribe in Bataan (Pablo, 2019); cancer by the Manobo tribe in Bukidnon (Pucot et al., 2019); skin eruptions and gastric pain by the Ati tribe in Aklan (Cordero et al., 2020); ten different diseases by the Manobo tribe in Agusan del Sur (Dapar et al., 2020); myoma, hepatitis, relapse, sore eyes, and stye by the eight ethnolinguistic groups in Zamboanga Peninsula (Madjos and Ramos, 2021); bruise and boils by the Mamanwa tribe in Surigao del Norte and Agusan del Norte (Nuñeza et al., 2021). In India, the use of C. longa dates back to 4,000 years ago not only as a culinary spice but also for religious and medicinal importance. It contains bioactive compounds that have antioxidant, antimutagenic, antimicrobial, antimutagenic, antimicrobial, antifungal, anticancer, and other countless medicinal uses (Prasad and Aggarwal, 2011).

Artemisia vulgaris has the highest relative frequency citation. It is a cosmopolitan weed and is available nearly everywhere. It thus does not surprise that it is commonly used for cough, fever, headache, body pains, chest pain, fracture, and hearing problems. Other ethnobotanical surveys mentioned its efficacy against cough and scabies by the Kalanguya tribe in Ifugao (Balangcod and Balangcod, 2011); stomachache (Olowa et al., 2012); sore eyes, ear infection, and cough by the Ayta tribes in Pampanga (Ragragio et al., 2013); cough with phlegm, fever, abdominal pain, body pains, and headache (Ong and Kim, 2014); colds by the Talaandig tribe in Bukidnon (Odchimar et al., 2017); dysmenorrhea by the Y’Apayaos in Cagayan arthritis (Baddu and Ouano, 2018); fever, sore throat, colds, cough, and phlegm Ayta in Bataan (Tantengco et al., 2018); fever, headache, dizziness, stomachache, bloated stomach, and cough (Cordero et al., 2020); 11 different folkloric uses (Madjos and Ramos, 2021); cough and gas pain (Cordero and Alejandro, 2021); fever, cough, and cough with phlegm (Nuñeza et al., 2021). In medieval times, it was known as the “mother of herbs” due to its beneficial effects. Studies have been conducted worldwide for its antioxidant, bronchodilatory, hepatoprotective analgesic, antihypertensive, estrogenic, cytotoxic, antifungal and antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergenic, antimalarial, and anthelmintic activities (Ekiert et al., 2020). Artemisia, per se, is an extremely important plant genus, pharmacologically as well as economically. A. annua L. makes the most important example, famous for its many pharmacologically active substances but especially for Artemisin (Tu, 2011), an effective remedy against malaria.

Annona muricata, an important, widely grown fruit tree, has the highest relative importance index value (0.88) and is used to treat 13 diseases in 11 different use or disease categories. It recorded the high use report for treating UTI, cancer, and hypertension by drinking the leaf decoction or eating just the ripe fruit. It is also used by the Panay Bukidnon for high uric level, pneumonia, dizziness, intestinal cleansing, kidney trouble, doklong, itchy throat, amoebiasis, lump, and arthritis. In traditional medicine across the country, it is also used for the treatment of diarrhea (Olowa et al., 2012); dermatological diseases (Tantiado, 2012); fever, insect repellent, headache, and stomachache (Ragragio et al., 2013); tetanus (Pizon et al., 2016); gastrointestinal cleansing and tumors (Odchimar et al., 2017); fever and arthritis (Baddu and Ouano, 2018); stomachache and dizziness (Tantengco et al., 2018); diabetes, high blood, stomachache, UTI, and vertigo (Pablo, 2019); cancer (Agapin, 2019); 12 different diseases (Dapar et al., 2020); kidney problems, urinary tract infection, goiter, and anthelmintic (Cordero et al., 2020); at least 16 medical problems (Madjos and Ramos, 2021); cuts and wounds, stomach ulcer, intestinal cleansing, UTI, cough, and cancer (Cordero et al., 2020); cancer (Montero and Geducos, 2021); cough, wound, asthma, and UTI (Nuñeza et al., 2021); cancer, stomach acidity, hypertension, and cough (Belgica et al., 2021). Phytochemical constituents investigated on A. muricata exhibited antiarthritic, anticancer, anticonvulsant, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antihypertensive, antiparasitic, antiplasmodial, cytotoxic, gastroprotective, and wound healing activity (Moghadamtousi et al., 2015; Coria-Téllez et al., 2018).

The highest ICF value is in the diseases of the respiratory system category and Blumea balsamifera is the most frequently used medicinal plant to treat cough. A high number of informants agreed on the effectiveness of B. balsamifera against the diseases on the respiratory system, particularly for treating cough in the community. However, this therapeutic claim must be seriously considered for further pharmacological investigations to determine its efficacy. B. balsamifera is one of the ten medicinal plants endorsed by the Philippine Department of Health (DOH) as part of basic healthcare and clinically proven to have diuretic and antiurolithiasis properties. It is manufactured in the country for national distribution and marketing by the National Drug Formulary (World Health Organization, 1998). It also contains compounds (monoterpenes, diterpenes, sesquiterpenes) that have antitumor, antioxidant, antimicrobial and anti-inflammation, antiplasmodial, antityrosinase, wound healing, anti-obesity, disease and insect resistance, and hepatoprotective effects and radical scavenging activities (Pang et al., 2014).

The medicinal plant with the highest FL was the Chromolaena odorata under the injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes category. All informants who cited C. odorata preferred to use it as first aid for cuts and wounds. This suggests that C. odorata might contain valuable bioactive compounds with pharmacological effects for cuts and wounds that must be proven scientifically. Several ethnobotanical studies also recorded the use of C. odorata for cuts and wounds in the country (Olowa et al., 2012; Ong and Kim, 2014; Pizon et al., 2016; Odchimar et al., 2017; Tantengco et al., 2018; Cordero et al., 2020; Dapar et al., 2020; Belgica et al., 2021; Cordero and Alejandro 2021; Madjos and Ramos, 2021). The leaves of C. odorata are rich in flavonoids and have the highest concentration of allelochemicals. They have antimalarial, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, analgesic, antipyretic, antioxidant, anticancer, and wound healing properties (Vijayaraghavan et al., 2017).

Traditional medical practices in the indigenous groups in the Philippines are generally influenced by their cultural, spiritual, and religious beliefs of supernatural beings. Curcuma longa is the most preferred medicinal plant administered by the Panay Bukidnon to a sick person with conditions caused by unseen beings. In Hindu worship rights, C. longa has been used for offerings and magic (Velayudhan et al., 2012).

Plant-based compounds have been in constant use since ancient times for any emerging disease. There were several bioactive compounds extracted from medicinal plants with promising antiviral properties against the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) (Adhikari et al., 2020). In Thailand, 60 medicinal plant species were used to treat mild symptoms of COVID-19 (Phumthum et al., 2021). In Nepal, there were also 60 medicinal plants used (Khadka et al., 2021) and 23 plants in Morroco (El Alami et al., 2020) for potential COVID-19 therapy and Zingiber officinale is one of the common species used. In Bangladesh, phytochemicals extracted from Calotropis gigantea exhibited positive inhibitory effects against the COVID-19 virus (Dutta et al., 2021), as well as the alkaloids and terpenoids isolated from plants of African origin (Gyebi et al., 2021). Curcumin from C. longa also showed promising effects against the virus (Adhikari et al., 2020).

In the Philippines, the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) has been conducted clinical trials and explored the therapeutic effects of the virgin coconut oil (VCO), Euphorbia hirta (tawa-tawa), and Vitex trifolia (lagundi) for their potential efficacy against COVID-19 infection (Arayata, 2021). In the recent updates published in the Global Media Arts (GMA) news articles, clinical trials for V. trifolia and E. hirta have been proven to decrease mild-to-moderate symptoms of COVID-19. Mild-to-moderate symptoms of 172 random COVID-19 patients disappeared within 3–5 days after taking a 1,950 mg capsule of E. hirta thrice a day for ten days as a food supplement. V. trifolia also showed a positive result in decreasing mild symptoms of COVID-19. Community trials of VCO as an adjuvant for mild symptoms of COVID-19 patients showed a positive result in decreasing the virus count by 60–90%. A clinical trial of VCO on mild and severe symptoms of COVID-19 conducted in Philippine General Hospital is still ongoing (Global Media Arts News, 2021a; Global Media Arts News, 2021b).

V. trifolia, C. longa, Z. officinale, Capsicum annuum, E. hirta, and Peperomia pellucida were used by the Panay Bukidnon as an alternative medicine to strengthen their immunity and they have claimed that these species can alleviate the symptoms of the COVID-19 infection. They used these plants traditionally to treat fever, headache, cough, and body pains, which were also the common indications of COVID-19. Further pharmacological research and investigations are highly suggested for these medicinal plants to explore their potential uses and therapeutic effects against COVID-19 infection especially for Zingiber officinale, Capsicum annuum, and Peperomia pellucida species. The Panay Bukidnon also believed that chewing betel quid could give them the strength to fight the virus. Chewing betel quid has been a customary practice of Filipinos since the pre-Spanish colonial period throughout the Philippines. It is part of the social undertakings and ceremonies and is believed to increase stamina, good health, and longevity (Valdes, 2004). In India, the practice of chewing betel dates back to around 75 AD and it is known for centuries for its therapeutic properties (Toprani and Patel 2013). A review was conducted on the synergistic prophylaxis effects of Piper betle and gold ash can hypothetically limit and manage the COVID-19 infection (Sharma and Malik, 2020).

For the comparative review performed on the medicinal plants with other ethnobotanical studies conducted in the country, three species (Eleutherine palmifolia, Hibiscus acetosella, and Oxalis triangularis) showed no record of medicinal value in the previous studies. E. palmifolia is used by the Dayaks in Indonesia to treat a variety of diseases such as diabetes, cancer, hypertension, stroke, and sexual disorders and as a galactagogue. Bioactive compounds from this species contain various pharmacological activities such as antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antidiabetic (Kamarudin et al., 2021). H. acetosella is used as therapy for anemia in Southern Uganda (Ssegawa and Kasenene, 2007) and its phenolic compounds exhibit antioxidant and antibacterial properties (Lyu et al., 2020). Limited literature is available for O. triangularis, but its medicinal uses include remedies for fever, UTI, mouth sores, cuts, rashes, and skin infections (Arakelyan and Arakelyan, 2020). The comparison of the medicinal plants and their uses was performed with five ethnobotanical studies that were previously conducted in the rural and urban communities and villages (Tantiado, 2012; Gruyal et al., 2014; Agapin, 2019; Belgica et al., 2021; Montero and Geducos, 2021), 17 studies conducted in the IP communities (Balangcod and Balangcod, 2011; Olowa et al., 2012; Abe and Ohtani, 2013; Ragragio et al., 2013; Ong and Kim, 2014; Raterta et al., 2014; Balangcod and Balangcod, 2015; Pizon et al., 2016; Odchimar et al., 2017; Baddu and Ouano, 2018; Tantengco et al., 2018; Pablo, 2019; Cordero et al., 2020; Dapar et al., 2020; Paraguison et al., 2020; Cordero and Alejandro, 2021; Nuñeza et al., 2021) all over the country, and one online database: the Philippine Traditional Knowledge Digital Library on Health (Philippine Traditional Knowledge Digital Library on Health, 2021). The PTKDL is an electronic library that documented 16,690 enumerations of medicinal plant preparations and 66 healing rituals and practices mentioned by 509 traditional healers in 43 different research sites in the country (World Health Organization, 2019). The database (https://www.tkdlph.com/) recorded about 1,200 medicinal plants used by the local and indigenous communities from different ethnobotanical studies, lexicographic and linguistic texts, and current researches conducted in selected indigenous communities nationwide.

Conclusion

The ethnobotanical use of many different plant species is an important predominating practice in the Philippines. It is an integral part of Filipino custom and tradition and has been culturally accepted for ages. The results of this ethnobotanical documentation of 131 medicinal plants used in addressing 91 diseases across 16 different disease categories portray the strong dependence of the Panay Bukidnon in the medicinal flora in their area. This could be attributed to the great distance of the study site to the town and the health centers or well-functioning hospitals. The most culturally relevant and important species recorded in this study in terms of UV, RFC, RI, ICF, and FL are Curcuma longa, Blumea balsamifera, Artemisia vulgaris, Annona muricata, and Chromolaena odorata, respectively. The efficacy and effectivity of the therapeutic claims of these species must be further pharmacologically investigated and validated. These species have been used for centuries by many people worldwide and have proven to cure a myriad of diseases. The comparative study of the medicinal plants with other ethnobotanical studies revealed some novel and additional therapeutic uses that are valuable to the immense body of traditional knowledge and practices in the country. The traditional knowledge and practices from indigenous peoples add more treatment opportunities for potential therapy of pre-existing and novel diseases. The indigenous knowledge on the medicinal plants used by the Panay Bukidnon is passed from one generation to the other mostly in oral forms with the influence of their religious and cultural beliefs. Furthermore, it is urgent to document the indigenous knowledge before it is forgotten because of environmental and social challenges such as species extinction, climate change, acculturation, modernization, availability and accessibility of prescribed medicines, and lack of interest of the younger generations. The results of this study also serve as a medium for preserving cultural heritage, ethnopharmacological bases for further drug research and discovery, and preserving biological diversity. The ethnobotanical study on the Panay Bukidnon communities in Panay Island is limited by the expensive and lengthy process of acquiring government permits and by the fact that some communities are infested by leftists (New People’s Army) that could risk the safety of researchers and there are no access roads in the upland areas. Lastly, it is strongly recommended to conduct further comprehensive surveys on other Panay Bukidnon communities in other provinces of the Panay Island and to conduct pharmacological studies and investigations on the important medicinal plants, especially the ones that have high ICF and FL values for potential drug development and formulation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Graduate School–Ethics Review Committee, University of Santo Tomas. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CSC processed and acquired the necessary government permits, conducted the field works, and drafted the manuscript. All authors designed the study, GJDA and UM supervised, reviewed, and made the final revision of the manuscript.

Funding

The research had partial funding from the scholarship of the first author from the Commission on Higher Education K-12 Transition Program (CHED K-12) and the Digital Cooperation Fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation awarded to GJDA and UM.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors are forever grateful to the Panay Bukidnon IP leader, the council of elders, members, and Brgy. officials of Brgy. Caguisanan, Lamunao, Iloilo; DENR Region VI for the Wildlife Gratuitous Permit; NCIP Iloilo-Guimaras Service Center officers for facilitating the community meetings; NCIP Region VI/VII for the issuance of the Certification Precondition. Heartfelt gratitude is also given to the Ethics Review Committee of the University of Santo Tomas Graduate School, Danilo Tandang of the Philippine National Museum, and Michael Calaramo of the Herbarium of the Northwestern University Luzon. CSC would like to thank CHED K-12 for her scholarship. GJDA and UM acknowledge the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for the Digital Cooperation Fellowship.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2021.790567/full#supplementary-material

References

Abe, R., and Ohtani, K. (2013). An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants and Traditional Therapies on Batan Island, the Philippines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 145, 554–565. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.029

Adhikari, B., Marasini, B. P., Rayamajhee, B., Bhattarai, B. R., Lamichhane, G., Khadayat, K., et al. (2020). Potential Roles of Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Viral Diseases Focusing on COVID-19: A Review. Phytother. Res. 5, 1298–1312. doi:10.1002/ptr.6893

Agapin, J. S. F. (2019). Medicinal Plants Used by Traditional Healers in Pagadian City, Zamboanga del Sur, Philippines. Philipp. J. Sci. 149, 83–89. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3625332

Arakelyan, S. S., and Arakelyan, H. S. (2020). Beauty for Health – Oxalis Triangularis. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340829095_Beauty_For_Health_-Oxalis_Triangularis (Accessed November 5, 2021).

Arayata, M. C. (2021). PH Researchers Study Herbal Plants' Benefit in Fight vs. Covid-19. Philippine News Agency. Available at: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1104955 (Accessed September 03, 2021).

Baddu, V., and Ouano, N. (2018). Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used by the Y’Apayaos of Sta. Praxedes in the Province of Cagayan, Philippines. Mindanao J. Sci. Technol. 16, 128–153.

Balangcod, T., and Balangcod, A. K. (2011). Ethnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among the Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, Philippines. Indian J. Tradit Knowl. 10, 227–238.

Balangcod, T., and Balangcod, A. K. (2015). Ethnomedicinal Plants in Bayabas, Sablan, Benguet Province, Luzon, Philippines. E J. Biol. 11, 63–73.

Belgica, T. H., Suba, M., and Alejandro, G. J. (2021). Quantitative Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal flora Used by Local Inhabitants in Selected Barangay of Malinao, Albay, Philippines. Biodiversitas 22, 2711–2721. doi:10.13057/biodiv/d220720

Beyer, O. H. (1917). Population of the Philippine islands in 1916 (población de las islas Filipinas en 1916) prepared under the direction of, preparado bajo la dirección de H. Otley Beyer. Manila, Philippines: Philippine Education Co. Inc.

Chanda, S., and Kaneria, M. (2011). in Indian Nutraceutical Plant Leaves as a Potential Source of Natural Antimicrobial Agents in Science against Microbial Pathogens: Communicating Current Research and Technological Advances. Editor M. Vilas (Badajoz, Spain: Formatex Research Center), 1251–1259.

Cordero, C., and Alejandro, G. J. D. (2021). Medicinal Plants Used by the Indigenous Ati Tribe in Tobias Fornier, Antique, Philippines. Biodiversitas 22, 521–536. doi:10.13057/biodiv/d220203

Cordero, C., Ligsay, A., and Alejandro, G. (2020). Ethnobotanical Documentation of Medicinal Plants Used by the Ati Tribe in Malay, Aklan, Philippines. J. Complement. Med. Res. 11, 170–198. doi:10.5455/jcmr.2020.11.01.20

Coria-Téllez, A. V., Montalvo-GónzalezYahia, E. E. M., and Obledo-Vázquez, E. N. (2018). Annona Muricata: A Comprehensive Review on its Traditional Medicinal Uses, Phytochemicals, Pharmacological Activities, Mechanisms of Action and Toxicity. Arab. J. Chem. 11, 662–691. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.01.004

Dapar, M. L. G., Alejandro, G. J. D., Meve, U., and Liede-Schumann, S. (2020). Quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation and molecular confirmation of medicinal plants used by the Manobo tribe of Agusan del Sur, Philippines. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed 16, 14. doi:10.1186/s13002-020-00363-7

Department of Environment and Natural Resources (2019). Regional Profile: Historical Background of the Region. DENR Region. Available at: https://r6.denr.gov.ph/index.php/about-us/regional-profile (Accessed September 02, 2021).

Dutta, M., Nezam, M., Chowdhury, S., Rakib, A., Paul, A., Sami, S. A., et al. (2021). Appraisals of the Bangladeshi Medicinal Plant Calotropis Gigantea Used by Folk Medicine Practitioners in the Management of COVID-19: A Biochemical and Computational Approach. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 625391. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2021.625391

Ekiert, H., Pajor, J., Klin, P., Rzepiela, A., Ślesak, H., and Szopa, A. (2020). Significance of Artemisia Vulgaris L. (Common Mugwort) in the History of Medicine and its Possible Contemporary Applications Substantiated by Phytochemical and Pharmacological Studies. Molecules 25, 4415. doi:10.3390/molecules25194415

El Alami, A., Fattah, A., and Chait, A. (2020). Medicinal Plants Used for the Prevention Purposes during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Morocco. J. Anal. Sci. Appl. Biotechnol. 2, 4–11. doi:10.48402/IMIST.PRSM/jasab-v2i1.21056

Friedman, J., Yaniv, Z., Dafni, A., and Palewitch, D. (1986). A Preliminary Classification of the Healing Potential of Medicinal Plants, Based on a Rational Analysis of an Ethnopharmacological Field Survey Among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 16, 275–287. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(86)90094-2

German, M. A. (2010). (Re)searching Identity in the highlands of Central Panay. Quezon City, Philippines: Ugnayang Pang-Aghamtao, Inc. Vol. 19, 20–37.

Global Media Arts News (2021a). DOST Exec Bares Positive Results of Lagundi, Tawa-Tawa Trials. Available at: https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/scitech/science/807308/dost-exec-bares-positive-results-of-lagundi-tawa-tawa-trials/story/(Accessed October 30, 2021).

Global Media Arts News (2021b). VCO Trials Show Big Drop in Virus Count of Mild COVID-19 Cases. Available at: https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/scitech/science/807310/vco-trials-show-big-drop-in-virus-count-in-mild-covid-19-cases/story/(Accessed October 30, 2021).

Gowey, D. (2016). Palawod, Pa-Iraya: A Synthesis of Panay Bukidnon Inland Migration Models. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/29928804/Palawod_Pairaya_A_Synthesis_of_Panay_Bukidnon_Inland_Migration_Models (Accessed September 03, 2021).

Gruyal, G., del Rosario, R., and Palmes, N. (2014). Ethnomedicinal Plants Used by Residents in Northern Surigao del Sur,Philippines. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res. 2014 2, 1–5. doi:10.4172/2329-6836.1000140

Tantengco, O. A. G., Condes, M. L. C., Estadilla, H. H. T., and Ragragio, E. M. (2018). Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants Used by Ayta Communities in Dinalupihan, Bataan, Philippines. Pharmacog. J. 10, 859–870. doi:10.5530/pj.2018.5.145

Gyebi, G. A., Ogunro, O. B., Adegunloye, A. P., Ogunyemi, O. M., and Afolabi, S. O. (2021). Potential Inhibitors of Coronavirus 3-chymotrypsin-like Protease (3CLpro): an In Silico Screening of Alkaloids and Terpenoids from African Medicinal Plants. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 39, 1–13. doi:10.1080/07391102.2020.1764868

Heinrich, M., Ankli, A., Frei, B., Weimann, C., and Sticher, O. (1998). Medicinal Plants in Mexico: Healers' Consensus and Cultural Importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 47, 1859–1871. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00181-6

International Plant Names Index (2021). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries and Australian National Botanic Gardens. Available at: http://www.ipni.org (Accessed September 04, 2021).

Jain, C., Khatan, S., and Vijayvergia, R. (2019). Bioactivity of Secondary Metabolites of Various Plants: a Review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 10, 494–504. doi:10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.10(2).494-04

Jocano, L. (1968). Sulud Society. A Study in the Kinship System and Social Organization of a Mountain People of Central Panay. Diliman. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Kamarudin, A. A., Sayuti, N. H., Saad, N., Razak, N. A. A., and Esa, N. M. (2021). Eleutherine Bulbosa (Mill.) Urb. Bulb: Review of the Pharmacological Activities and its Prospects for Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6747. doi:10.3390/ijms22136747

Khadka, D., Dhamala, M. K., Li, F., Aryal, P. C., Magar, P. R., Bhatta, S., et al. (2021). The Use of Medicinal Plants to Prevent COVID-19 in Nepal. Ijms 22, 26. doi:10.1186/s13002-021-00449-w

Lyu, J. I., Ryu, J., Jin, C. H., Kim, D. G., Kim, J. M., Seo, K. S., et al. (2020). Phenolic Compounds in Extracts of Hibiscus acetosella (Cranberry Hibiscus) and Their Antioxidant and Antibacterial Properties. Molecules 25 (18), 4190. doi:10.3390/molecules25184190

Madjos, G., and Ramos, K. (2021). Ethnobotany, Systematic Review and Field Mapping on Folkloric Medicinal Plants in the Zamboanga Peninsula, Mindanao, Philippines. J. Complement. Med. .Res. 12. doi:10.5455/jcmr.2021.12.01.05

Madulid, D. A., Gaerlan, F. J. M., Romero, E. M., and Agoo, E. M. G. (1989). Ethnopharmacological Study of the Ati Tribe in Nagpana, Barotac Viejo, Iloilo. Acta Manil 38, 25–40.

Magos, A. (2004). Balay Turun-An: An Experience in Implementing Indigenous Education in Central Panay, 13. Quezon City, Philippines: Ugnayang Pang-Aghamtao, Inc., Vol. 19, 95–102.

Magos, A. (1999). Sea Episodes in the Sugidanon (Epic) and Boat-Buildng Tradition in Central Panay, Philippines. Danyag (UP Visayas Journal of the Social Sciences and the Humanities) 4, 5–29.

Moghadamtousi, S. Z., Fadaeinasab, M., Nikzad, S., Mohan, G., Ali, H. M., and Kadir, H. A. (2015). Annona Muricata (Annonaceae): A Review of its Traditional Uses, Isolated Acetogenins and Biological Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 15625–15658. doi:10.3390/ijms160715625

Montero, J. C., and Geducos, D. T. (2021). Ethnomedicinal plants used by the local folks in two selected villages of San Miguel and Surigao del Sur, villages of San Miguel, Surigao del Sur, Mindanao, Philippines. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 17, 193–212.

National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (2019). Community Population (Census) Province of Antique and Aklan. San Jose Buenavista, Antique: National Commission on Indigenous Peoples Antique/Aklan Community Service Center.

National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (2011). Indigenous Peoples MasterPlan (2012-2016). Available at: https://www.ombudsman.gov.ph/UNDP4/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Indigenous-Peoples-Master-Plan-2012-2016.pdf (Accessed August 21, 2021).

National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (2020). Region VI Statistical Report 2020. Available at: https://www.ncipro67.com.ph/statistics-corner/(Accessed September 01, 2021).

National Economic Development Agency (2017). Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022. Available at: http://pdp.neda.gov.ph/(Accessed August 02, 2021).

Nuneza, O., Rodriguez, B., and Nasiad, J. G. (2021). Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by the Mamanwa tribe of Surigao del Norte and Agusan del Norte, Mindanao, Philippines. Biodiversitas 22, 3284–3296. doi:10.13057/biodiv/d220634

Obico, J. J. A., and Ragrario, E. M. (2014). A Survey of Plants Used as Repellants against Hematophagous Insects by the Ayta People of Porac, Pampanga Province. Phil. Sci. Lett. 7, 179–186.

Odchimar, N. M., Nuñeza, O., Uy, M., and Senarath, W. T. P. S. (2017). Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants Used by the Talaandig Tribe in Brgy. Lilingayon, Valencia City, Bukidnon, Philippines. Asian J. Biol. Life Sci. 6, 358–364.

Olowa, L., Torres, M. A., Aranico, E., and Demayo, C. (2012). Medicinal Plants Used by the Higaonon Tribe of Rogongon, Iligan City, Mindanao, Philippines. Adv. Environ. Biol. 6, 1442–1449. doi:10.3923/erj.2012.164.174

Ong, H. G., and Kim, Y.-D. (2015). Herbal Therapies and Social-Health Policies: Indigenous Ati Negrito Women's Dilemma and Reproductive Healthcare Transitions in the Philippines. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 1–13. doi:10.1155/2015/491209

Ong, H. G., and Kim, Y. D. (2014). Quantitative Ethnobotanical Study of the Medicinal Plants Used by the Ati Negrito Indigenous Group in Guimaras Island, Philippines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 157, 228–242. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.015

Pablo, C. G. (2019). Botika Sa Kalikasan: Medicinal Plants Used by Aetas of Sitio Parapal Hermosa Bataan, Philippines. J. Soc. Health 2, 101–127.

Pang, Y., Wang, D., Fan, Z., Chen, X., Yu, F., Hu, X., et al. (2014). Blumea Balsamifera--a Phytochemical and Pharmacological Review. Molecules 19, 9453–9477. doi:10.3390/molecules19079453

Paraguison, L. D. R., Tandang, D. N., and Alejandro, G. J. D. (2021). Medicinal Plants Used by the Manobo Tribe of Prosperidad, Agusan Del Sur, Philippinesan Ethnobotanical Survey. Ajbls 9, 326–333. doi:10.5530/ajbls.2020.9.49

Parasuraman, S., Thing, G. S., and Dhanaraj, S. A. (2014). Polyherbal Formulation: Concept of Ayurveda. Pharmacogn. Rev. 8, 73–80. doi:10.4103/0973-7847.134229

Pelser, P. B., Barcelona, J. F., and Nickrent, D. L. (2011). Co’s Digital Flora of the Philippines. Available at: www.philippineplants.org (Accessed September 02, 2020).

Philippine Statistics Authority (2021). 2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH) Population Counts Declared Official by the President. Available at: https://psa.gov.ph/content/2020-census-population-and-housing-2020-cph-population-counts-declared-official-president (Accessed November 11, 2021).

Philippine Traditional Knowledge Digital Library on Health (2021). Philippine Plants and Natural Products Used Traditionally. Available at: https://www.tkdlph.com/index.php/ct-menu-item-3/ct-menu-item-7 (Accessed October 30, 2021).

Phillips, O., and Gentry, A. H. (1993). The Useful Plants of Tambopata, Peru: I. Statistical Hypotheses Tests with a New Quantitative Technique. Econ. Bot. 47, 15–32. doi:10.1007/bf02862203

Phumthum, M., Nguanchoo, V., and Balslev, H. (2021). Medicinal Plants Used for Treating Mild Covid-19 Symptoms Among Thai Karen and Hmong. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 699897. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.699897

Pizon, J. R. L., Nuneza, O. M., Uy, M. M., and Senarath, W. T. P. S. K. (2016). Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants Used by the Subanen Tribe of Lapuyan, Zamboanga del Sur. Bull. Env. Pharmacol. Life Sci. 5, 53–67.

Plants of the World Online (2021). Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available at: http://plantsoftheworldonline.org/(Accessed September 03, 2021).

Prasad, S., and Aggarwal, B. B. (2011). “Turmeric, the Golden Spice: From Traditional Medicine to Modern Medicine,” in Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. Editors I. F. F. Benzie, and S. Wachtel-Galor (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis).

Province of Iloilo (2015). About Iloilo. Available at: https://www.iloilo.gov.ph/about-iloilo (Accessed September 01, 2021).

Provincial Planning Development Office (2018). Iloilo Provincial Annual Profile. Available at: https://www.iloilo.gov.ph/iloilo-provincial-annual-profile (Accessed August 20, 2021).

Pucot, J. R., Manting, M. M. E., and Demayo, C. G. (2019). Ethnobotanical Plants Used by Selected Indigenous Peoples of Mindanao, the Philippines as Cancer Therapeutics. Pharmacophore 10, 61–69.

Ragragio, E., Zayas, C. N., and Obico, J. J. A. (2013). Useful Plants of Selected Ayta Communities from Porac, Pampanga, Twenty Years after the Eruption of Mt. Pinatubo. Philipp. J. Sci. 142, 169–181.

Raterta, R., de Guzman, G. Q., and Alejandro, G. J. D. (2014). Assessment, Inventory and Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Batan and Sabtang Island (Batanes Group of Islands, Philippines). Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 2, 147–154.

Sharma, S., and Malik, J. (2020). Synergistic Prophylaxis on COVID-19 by Nature Golden Heart (Piper Betle) & Swarna Bhasma. Asian J. Res. Dermat. Sci. 3, 21–27.

Smith, W. (1915). Notes on the Geology of Panay. From the Division of Mines. Manila, Philippines: Bureau of Science.

Ssegawa, P., and Kasenene, J. M. (2007). Medicinal Plant Diversity and Uses in the Sango bay Area, Southern Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol 113 (3), 521–540. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.014

Talledo, T. (2004). Construction of Identity in Central Panay: A Critical Examination of the Ethnographic Subject in the Works of Jocano and Magos. Asian Stud. 40, 111–123.

Tantiado, R. (2012). Survey on Ethnopharmacology of Medicinal Plants in Iloilo, Philippines. Inter. J. Bio-sci. Bio-tech. 4, 11–26.

Tardío, J., and Pardo-De-Santayana, M. (2008). Cultural Importance Indices: a Comparative Analysis Based on the Useful Wild Plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain)1. Econ. Bot. 62, 24–39. doi:10.1007/s12231-007-9004-5

Toprani, R., and Patel, D. (2013). Betel Leaf: Revisiting the Benefits of an Ancient Indian Herb. South. Asian J. Cancer 2, 140–141. doi:10.4103/2278-330X.114120

Tropicos (2021). Missouri Botanical Garden. Available at: https://tropicos.org (Accessed September 02, 2021).

Tu, Y. (2011). The Discovery of Artemisinin (Qinghaosu) and Gifts from Chinese Medicine. Nat. Med. 17, 1217–1220. doi:10.1038/nm.2471

United Nations Development Programme (2019). 10 Things to Know about Indigenous Peoples. Available at: https://stories.undp.org/10-things-we-all-should-know-about-indigenous-people (Accessed August 06, 2021).

Velayudhan, K. C., Dikshit, N., and Nizar, M. A. (2012). Ethnobotany of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa L.). Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 11, 607–614.

Vijayaraghavan, K., Rajkumar, J., Bukhari, S. N., Al-Sayed, B., and Seyed, M. A. (2017). Chromolaena Odorata: A Neglected weed with a Wide Spectrum of Pharmacological Activities (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 15, 1007–1016. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.6133

Wanda, J. M., Gamo, F., and Njamen, D. (2015). “Medicinal Plants of the Family of Fabaceae Used to Treat Various Ailments in Fabaceae,” in Classification, Nutrient Composition and Health Benefits Series. Editor W. Garza (NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.).

World Flora Online (2021). World Flora Online. Available at: http://www.worldfloraonline.org/(Accessed September 02, 2021).

World Health Organization (2021). ICD-11 International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. Available at: https://icd.who.int/en (Accessed September 03, 2021).

World Health Organization (2019). WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine. Available at: https://www.who.int/traditionalcomplementary-integrative medicine/Who Global Report On TraditionalAndComplementaryMedicine2019.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed October 28, 2021).

Keywords: ethnobotany, ethnomedicine, Panay Bukidnon, Panay Island, Philippines

Citation: Cordero CS, Meve U and Alejandro GJD (2022) Ethnobotanical Documentation of Medicinal Plants Used by the Indigenous Panay Bukidnon in Lambunao, Iloilo, Philippines. Front. Pharmacol. 12:790567. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.790567

Received: 06 October 2021; Accepted: 18 November 2021;

Published: 10 January 2022.

Edited by:

Alessandra Durazzo, Council for Agricultural Research and Economics, ItalyReviewed by:

Bahar Gürdal, Istanbul University, TurkeyEmin Ugurlu, Bursa Technical University, Turkey

Wajid Rashid, Beijing Normal University, China

Esezah Kakudidi, Makerere University, Uganda

Mohammad Sadat-Hosseini, University of Jiroft, Iran

Copyright © 2022 Cordero, Meve and Alejandro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cecilia Salugta Cordero, Y2VjaWxpYS5jb3JkZXJvQHNkY2EuZWR1LnBo

Cecilia Salugta Cordero

Cecilia Salugta Cordero Ulrich Meve

Ulrich Meve Grecebio Jonathan Duran Alejandro

Grecebio Jonathan Duran Alejandro