- Center for Novel Target and Therapeutic Intervention, Institute of Life Sciences, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China

The cytochrome P450 (CYP) ω-hydroxylases are a subfamily of CYP enzymes. While CYPs are the main metabolic enzymes that mediate the oxidation reactions of many endogenous and exogenous compounds in the human body, CYP ω-hydroxylases mediate the metabolism of multiple fatty acids and their metabolites via the addition of a hydroxyl group to the ω- or (ω-1)-C atom of the substrates. The substrates of CYP ω-hydroxylases include but not limited to arachidonic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins. The CYP ω-hydroxylases-mediated metabolites, such as 20-hyroxyleicosatrienoic acid (20-HETE), 19-HETE, 20-hydroxyl leukotriene B4 (20-OH-LTB4), and many ω-hydroxylated prostaglandins, have pleiotropic effects in inflammation and many inflammation-associated diseases. Here we reviewed the classification, tissue distribution of CYP ω-hydroxylases and the role of their hydroxylated metabolites in inflammation-associated diseases. We described up-regulation of CYP ω-hydroxylases may be a pathogenic mechanism of many inflammation-associated diseases and thus CYP ω-hydroxylases may be a therapeutic target for these diseases. CYP ω-hydroxylases-mediated eicosanods play important roles in inflammation as pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory mediators, participating in the process stimulated by cytokines and/or the process stimulating the production of multiple cytokines. However, most previous studies focused on 20-HETE,and further studies are needed for the function and mechanisms of other CYP ω-hydroxylases-mediated eicosanoids. We believe that our studies of CYP ω-hydroxylases and their associated eicosanoids will advance the translational and clinal use of CYP ω-hydroxylases inhibitors and activators in many diseases.

Introduction

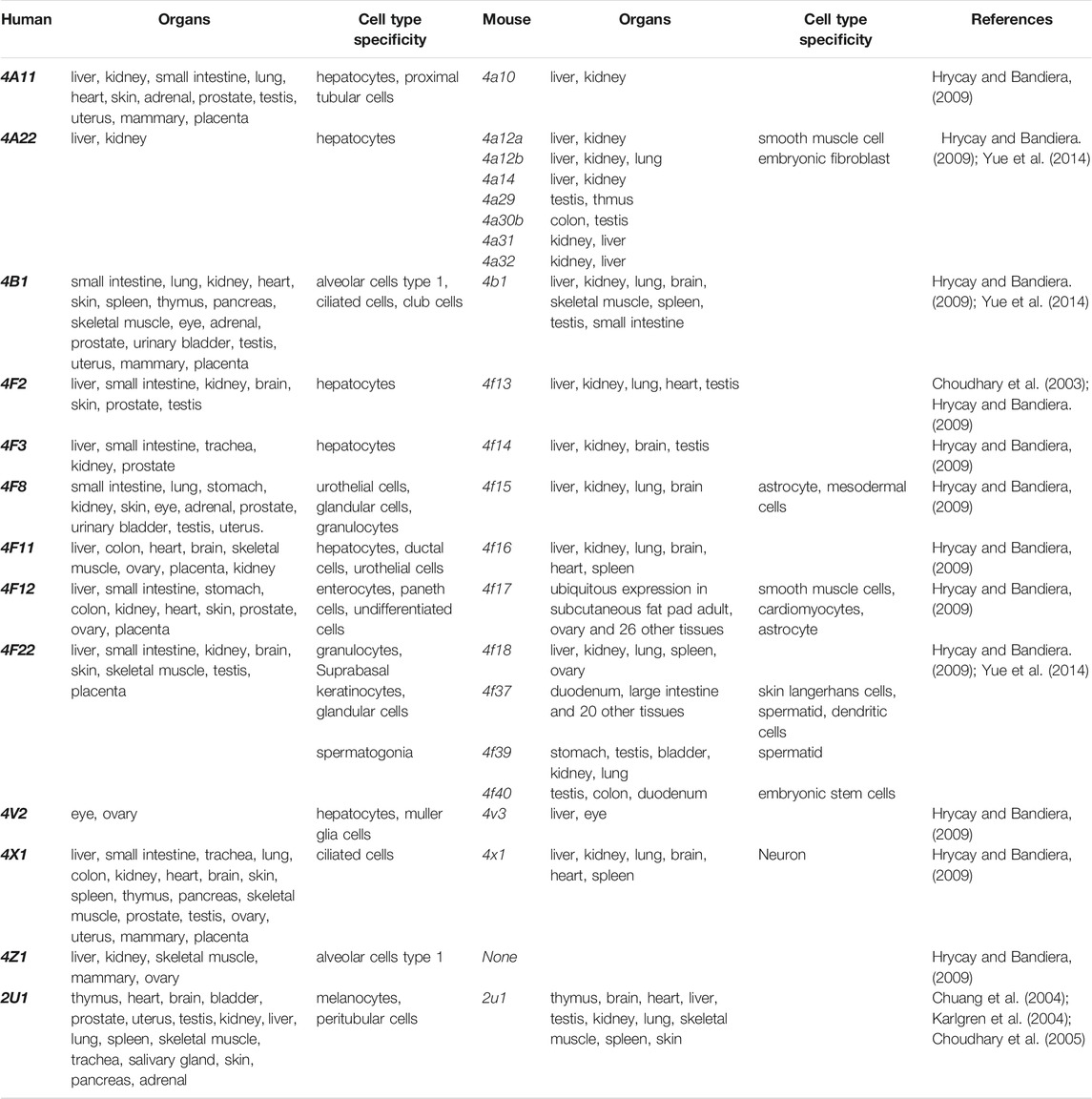

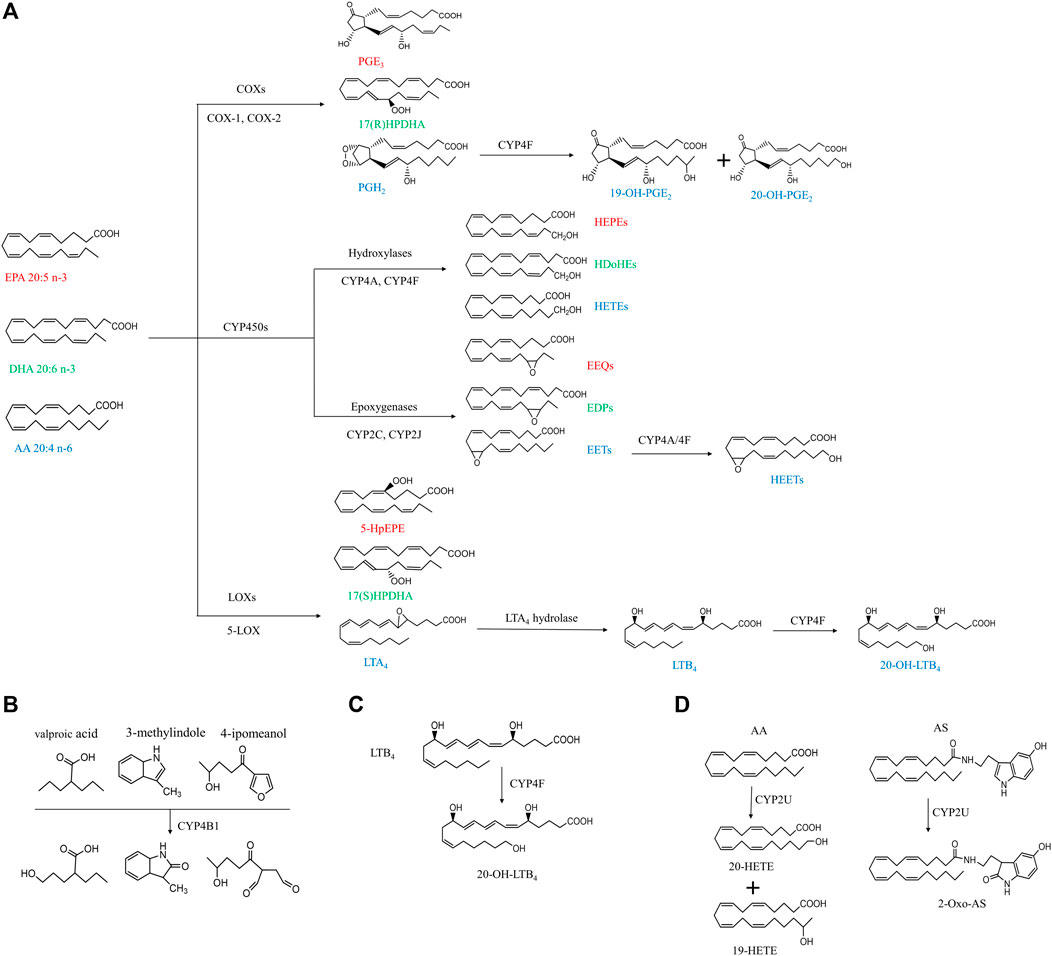

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, discovered in the early 1960s, are a superfamily of heme containing membrane bound monoxygenases which is available in microorganisms, plants, animals, and humans (Guengerich et al., 2016; Elfaki et al., 2018). About 300,000 CYP sequences have been collected from public and private sources (Nelson, 2018). The common reactions catalyzed by CYPs include hydroxylation, heteroatom oxygenation and release, epoxidation, and oxidation of double, triple, or aromatic π-bonds (Guengerich, 2001; McIntosh et al., 2014; Ortiz de Montellano, 2019). Mammalian CYP enzymes are distributed in a variety of tissues and organs of organisms, and play a core role in cell metabolism to maintain cell homeostasis mainly by mediating the metabolism of a large number of xenobiotic and endobiotic molecules, including but not limited to drugs, industrial toxins, steroids, cholic acid, and fatty acids through regio-, chemo- and stereospecific oxidation, peroxidation and reduction (Urlacher and Girhard, 2012; Manikandan and Nagini, 2018). There are 57 CYP genes and 58 pseudogenes in human and are divided into 18 families and 43 subfamilies (Waring, 2020), which are mainly present in the kidney, small intestine and liver tissues (Elfaki et al., 2018). The CYP ω-hydroxylases, are a group of subfamilies of CYPs that mediate the metabolism of multiple fatty acids via the addition of a hydroxyl group to the ω- or (ω-1)-C atom of the substrates. This includes polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as arachidonic acid (AA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and their derivatives (Figure 1). Those metabolites derived from AA, EPA and DHA are the members of eicosanoids and function as inflammatory mediators, which play an important role in the occurrence and progression of many pathological conditions like cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes (Westphal et al., 2011; Schunck et al., 2018; Colombero et al., 2020). This article reviews the activity and expression changes of CYP ω-hydroxylase in inflammation-related diseases, and the enzyme-mediated metabolites, such as 20-HETE, which trigger the downstream signaling pathway and induce more pathological changes.

FIGURE 1. Simplified cascade of CYP ω-hydroxylases-mediated substrates and associated metabolites. The compounds with the same color indicate they are derived from the same substrates. AA, arachidonic acid; AS, N-arachidonoylserine; COX, cyclooxygenase; CYP, cytochrome P450; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EET, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; EEQ, epoxyeicosatetreaenoic acid; EDPs, epoxydocosapentaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; HEPEs, hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid; HEETs, hydroxyepoxyeicosatrienoic acids; HPDHA, hydroperoxydocosahexaenoic acid; HpEPE, hydroperoxyeicosapentaenoic acid; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; HDoHE, hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid; LOX, lipoxygenase; LTA4, leukotriene A4; LTB4, leukotriene B4; PGH2, prostaglandin H2; PGE3, prostaglandin E3.

Metabolism of n-3 and n-6 PUFAs

As shown in Figure 1, PUFAs can undergo three main enzymatic pathways: cyclooxygenase (COXs), CYP and lipoxygenase (LOXs). COXs convert EPA, DHA and AA into PGH2, PGE3, prostaglandin E3 (PGE3), 17(R)-hydroperoxydocosahexaenoic acid (17(R)HPDHA) and prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) (Smith and Song, 2002; Johnson et al., 2015). PGH2 can be further hydroxylated by CYP4F8 to 19-OH-PGH2. Human have six different kinds of LOXs (5-LOX, 12-LOX, 12/15-LOX, 15-LOX type 2, 12(R)-LOX, and epidermal LOX), and 5-LOX is a key enzyme in leukotriene biosynthesis in health and disease (Rådmark et al., 2015). EPA, DHA and AA can be metabolized by 5-LOX to 5-hydroperoxyeicosapentaenoic acid (5-HpEPE), 17(S)HPDHA and leukotriene A4 (LTA4), respectively. The metabolism by CYP pathways has been described in detail in our previous review and will not be included here (Luo and Liu, 2020).

Classification, Tissue Distribution, and Biological Characteristics of Cytochrome P450 omega hydroxylases

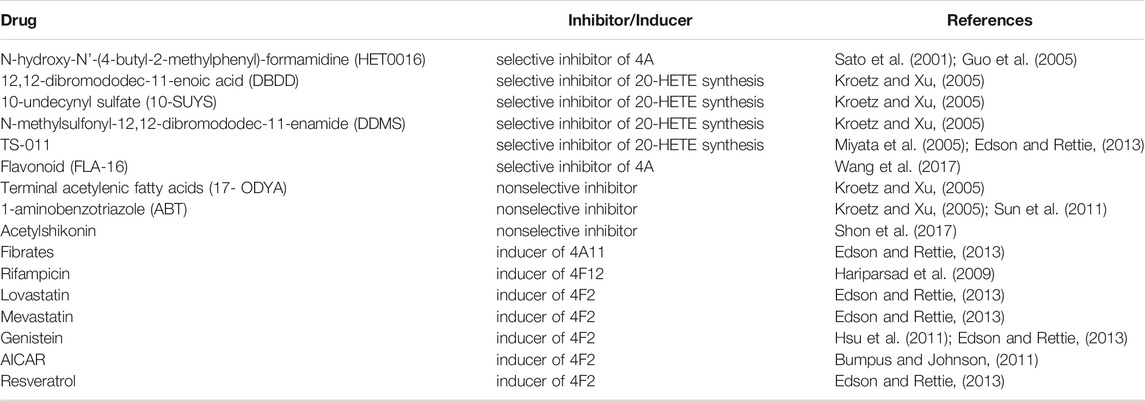

The human CYP enzymes that catalyze ω-hydroxylation of fatty acids include CYP4A, CYP4B, CYP4F, and CYP2U1 (Chuang et al., 2004; Hardwick, 2008) (Table1). These CYP enzymes can hydroxylate saturated fatty acids, branched fatty acids, unsaturated fatty acids, and some eicosanoids (Figure 1).

The CYP4A subfamilies are found in mammals, including human, rat, and mice, and are mainly expressed in the liver and kidney (Simpson, 1997). The mouse Cyp4a subfamily includes Cyp4a10, Cyp4a1a, Cyp4a12b, and Cyp4a14. In mice, Cyp4a mRNA expression levels in the liver and kidney are regulated by sex hormones and/or growth hormones (Zhang and Klaassen, 2013). In human, there are two highly homologous CYP4A genes (CYP4A11 and CYP4A22) located on chromosome 1, and showed 96% sequence identity (Bellamine et al., 2003; Savas et al., 2003; Hsu et al., 2007). However, rat CYP4 has four members (genes Cyp4a1, Cyp4a2, Cyp4a3, and Cyp4a8). CYP4A subfamily proteins metabolize arachidonic acid to produce 19-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (19-HETE) and 20-HETE, playing an important role in lipid homeostasis related to fatty acids and eicosanoic acids. Several studies have shown that CYP4A11 contributes about 13 and 33% to the formation of 20-HETE by ω-hydroxylation of arachidonic acid in the human liver and kidney (Powell et al., 1998; Lasker et al., 2000). The functions of the CYP4A22 have not been elucidated fully.

The tissue distribution of CYP4B1 varies widely among species. Cyp4b1 was originally discovered from the rabbit lung in the mid-1970s (Arinç and Philpot, 1976). In mice, Cyp4b1 expression is predominantly present in the brain, lung, and small intestine, while low in the spleen, testis, liver, and skeletal muscle (Baer and Rettie, 2006). Human CYP4B1 is mainly found in lung microsomes, accounting for 70% of the total, and remaining parts in the heart, skeletal muscle, kidneys, and prostate glands (Choudhary et al., 2005). CYP4B1 is specialized in the ω-hydroxylation of short-chain fatty acids and the metabolism of exogenous compounds including valproic acid, 3-methylindole, 4-ipomeanol, 3-methoxy-4-aminoazobenzene, and many aromatic amines (Figure 1B) (Baer and Rettie, 2006). The tissue specificity, genetic polymorphisms, and metabolic capabilities of human CYP4B1 are still under investigation because of the difficulty in allogeneic expression of the human CYP4B1 gene.

Human has seven CYP4F enzymes encoded by six different genes in the CYP4F gene cluster (19p13.1) on chromosome 19. CYP4F2 enzyme, also known as leukotriene B4 (LTB4) omega-hydroxylase, is located on chromosome 19 p13.11. CYP4F2 is approximately 20 kbp, consisting of 13 exons and 12 introns encoding 520 amino acids (Kikuta et al., 1999). It is mainly distributed in tissues and organs such as liver, kidney, lung, white blood cells, and particularly endoplasmic reticulum (Hsu et al., 2007; Hirani et al., 2008). CYP4F2 is a monooxygenase that catalyzes many reactions, including drug metabolism, the synthesis and metabolism of lipids, steroids, and cholesterol. It can affect the metabolism of AA and catalyze LTB4., a metabolite of AA mediated by (5-LOX), serving as the main ω-hydroxylase of AA and LTB4. Eun et al. found that the mRNA expression levels of CYP4F2 and CYP4F12 in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues were significantly lower than those in normal liver tissues, which was closely related to the overall survival rate of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (Eun et al., 2018). CYP4F3, an unusual human CYP gene, was initially identified as the ω-oxidase that catalyzes LTB4 in human neutrophils (Shak and Goldstein, 1984; Kikuta et al., 1993; Christmas et al., 2001). Christmas et al. subsequently identified an alternative splice form of CYP4F3 in the liver and specified two subtypes, CYP4F3A and CYP4F3B (Christmas et al., 2001). CYP4F3A is expressed in neutrophils but not in the liver and has a very high affinity to LTB4. In contrast, CYP4F3B is mainly expressed in the human liver and kidney, but not in myeloid cells, which is more active in the hydroxylation of AA and other ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) than in hydroxylating LTB4 (Fer et al., 2008). In rat, Cyp4f6 converts LTB4 to form 19- and 18-hydroxy-LTB4 with an apparent K(m) of 26 M and Cyp4f5 converts LTB4 predominantly to 18-hydroxy-LTB4 with an apparent K(m) of 9.7 M (Figure 1C). CYP4F5 and CYP4F6 are active in the lung and to some extent in the brain, kidney and testis. CYP4F5 and CYP4F6, due to their ability to metabolize LTB4, may play an important role in regulating the inflammatory response in these organs (Bylund et al., 2003).

Human CYP4V2 protein is expressed in eye, ovary, and liver (Li et al., 2004), while mouse Cyp4v3 is mainly detected in the liver and retina (Jenkins et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006). Human CYP4X1 is very widely expressed transcriptionally in adult human tissues, predominantly in skeletal muscle, trachea, and aorta (Hsu et al., 2007). Al-Anizy et al. reported that Cyp4x1 was a major CYP protein in mouse brain (Al-Anizy et al., 2006). CYP4Z1 gene is a unique CYP4 gene in human, and no orthologous gene has been found in mice at present. CYP4Z1 is mainly distributed in human liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, testis, and mammary, and is highly expressed in breast cancer, and a regulator of tumor angiogenesis and growth of breast cancer (Yu et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2016; Nunna et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). The substrates of CYP4Z1 and associated metabolism have not been fully understood.

CYP2U1 is an “orphan” enzyme which was originally identified as a member of CYP2 subfamily by Chuang et al. (2004) and Karlgren et al. (2004). To date, the CYP2U1 gene, the only reported member of the CYP2U subfamily, is over 18 kb long and located on chromosome 4q25 (Devos et al., 2010). Human CYP2U1 shares 89 and 83% amino acid sequence identity with rat and mouse Cyp2u1, respectively (Dhers et al., 2017). Studies have shown that human CYP2U1 mRNA is expressed predominantly in thymus and cerebellum, and similar findings were observed in rat and mice (Chuang et al., 2004; Karlgren et al., 2004; Dhers et al., 2017). However, human CYP2U1 protein was only detected in brain, platelets and megakaryocytic Dami cells (Dhers et al., 2017). Likewise, in rat Cyp2u1 protein was also present only in the cerebellum and thymus (Karlgren et al., 2004). CYP2U1 showed hydroxylase activity for fatty acids and N-arachidonoylserine (AS) (Figure 1D) (Dhers et al., 2017). Although CYP2U1 has been shown to be involved in some diseases such as breast cancer and hereditary spastic paraplegia, the biological role is still largely unknown (Luo et al., 2020). The cell-specific distribution of CYP ω-hydrolases is key to the local pro-inflammatory effects observed across various diseases. While a systemic study of the cell-specific distribution of these enzymes was lacked, CYP4A, CYP4F, and CYP4B1 have been frequently investigated in epithelial cells, endothelial cells, platelet and immunocytes (Table 1) (Kikuta et al., 2002; Kikuta et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2019).

Orthologous Cytochrome P450 ω-hydroxylase Genes in Human and Mice

Many different species share homology of genes. Generally, two genes are homologous genes when their sequence similarities are over 80%. Homologous sequences can be further divided into two types: orthology and paralogy (Koonin, 2005). A recent study showed that 84% of mouse-human orthologous genes have been conservatively evolved in the expression profiles (Hrycay and Bandiera, 2009). Thirty six pairs of orthologous CYP genes have been found to perform similar or identical functions in human and mice, which facilitates to study the functions of human CYPs by using murine models (Nelson et al., 2004). The CYP ω-hydroxylase orthologous genes in human and mice are shown in Table1.

Effects of Gender on Cytochrome P450 ω-hydroxylase

The expression of CYP ω-hydroxylases has gender differences. Cyp4a10 is expressed in both male and female mice, while Cyp4a12a is male-specific and regulated by androgen, and Cyp4a14 is strongly expressed in female mice (Wu et al., 2013). Cyp4a14 (−/−) mice have been found to exhibit male-specific hypertension. Whereas administration of androgens to male or female rat or mice results in hypertension (Holla et al., 2001). Both 20-HETE and androgens have been found to be strongly associated with hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases (Reckelhoff, 2005; Ward et al., 2005). However, the connection and potential mechanism between Both 20-HETE and androgens have not been clarified.

Cytochrome P450 ω-hydroxylases and Inflammation

CYP4A, CYP4B, CYP4F, and CYP2U1 are the subfamilies of CYP ω-hydroxylases that catalyze the hydroxylation of AA, other medium- and long-chain fatty acids, and the derivatives of fatty acids like LTB4, EETs, and prostaglandins. The CYP ω-hydroxylases-mediated metabolites derived from above-mentioned substrates, particularly 20-HETE, have been shown to play a vital role in inflammatory diseases. Here, we discuss the role of CYP ω-hydroxylases in inflammation.

Recent studies have shown that inflammation could significantly decrease the expression of CYP monooxygenases in the heart, kidney, and liver, while increase the expression of CYP ω-hydroxylases. As a result, CYP ω-hydroxylase mediated conversion of the corresponding metabolites of EETs were decreased, while 20-HETE was increased. These changes may participate in the onset and progression of various diseases through inflammatory response (Anwar-mohamed et al., 2010). In an in-vivo study, salidroside can facilitate reprogramming of CYP4A-mediated arachidonic acid metabolism in macrophages in the treatment of monosodium urate crystal-induced gouty arthritis. The study reported that salidroside could reduce the production of inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-1β by down-regulating CYP4A to polarize macrophages away from the M1 phenotype, and ameliorate inflammation (Liu et al., 2019). Ashkar et al. found that retinoic acid induces corneal epithelial CYP4B1 gene expression and stimulates the synthesis of inflammatory 12-hydroxyeicosanoic acid (Ashkar et al., 2004).

In a rodent model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory infection and injury, the mRNA expressions of Cyp4f4 and Cyp4f5 were decreased by 50 and 40%, respectively, in the liver, while the concentrations of leukotrienes and prostaglandins were increased. When Cyp4f was up-regulated, leukotrienes and prostaglandin mediators were decreased, thus alleviating inflammation (Cui et al., 2003). The decrease in leukotrienes and prostaglandins caused by upregulation of Cyp4f may be accounted for the metabolic shunting among CYPs, COXs, and LOXs, and/or Cyp4f-mediated metabolism of leukotrienes and prostaglandins. In addition, Kalsotra et al. reported that in a rat model of traumatic brain injury, inflammatory cells in the airway and alveolar space migrated extensively, and further secondary damage could be relieved by reducing LTB4 via activating LTB4 decomposition by induced CYP4Fs, which opened up new possibilities for the treatment of post-traumatic pulmonary inflammation (Kalsotra et al., 2007b). CYP4F2, the major LTB4 hydroxylase expressed in human liver, may play an important role in regulating the circulation and liver levels of LTB4 (Johnson et al., 2015). In addition to LTB4, it was also found that lipoxin A4 (LXA4) and hydroxyeicosanoic acid in rodent hepatocytes could be degraded via the ω-hydroxylation by recombinant CYP4Fs. Proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, induce CYP4Fs via STAT3 signaling. The anti-inflammatory factor IL-10 inhibits the expression of CYP4F (Kalsotra et al., 2007a).

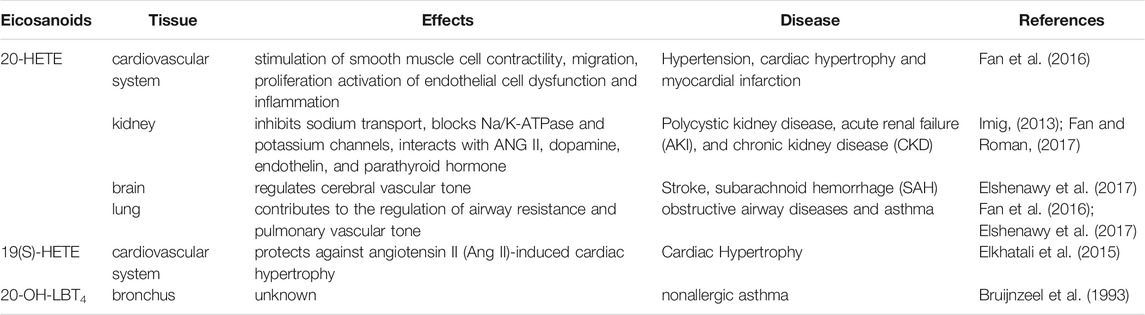

With the continuous innovation and development of biotechnology, research tools of chemical synthesis and gene editing continue to expand, research efficiency of CYP ω-hydroxylase is greatly improved. The associations of CYP ω-hydroxylases with pathogenesis of diseases are gradually discovered. Currently, activators and inhibitors of CYP ω-hydroxylase isomers, and CYP ω-hydroxylase knockout (KO) and transgenic mice are gradually being utilized in many studies. Tables 2, 3 summarizes the commonly used inhibitors and inducers of CYP ω-hydroxylase and CYP ω-hydroxylase KO and transgenic mice models.

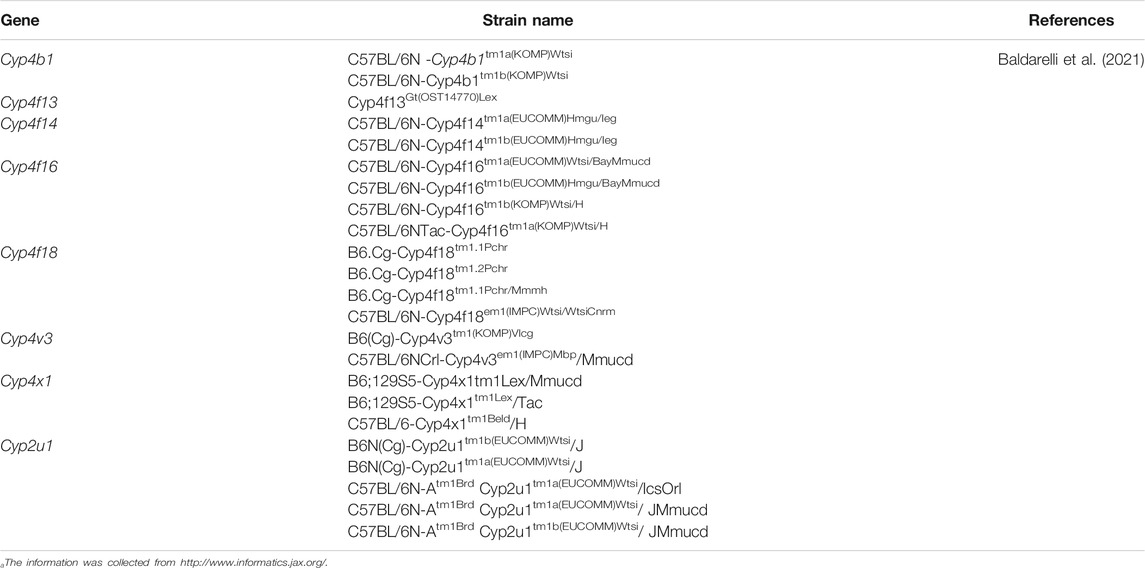

TABLE 3. CYP ω-hydroxylase KO and transgenic mouse modela.

The Roles of Cytochrome P450 ω-Hydroxylase-mediated Eicosanoids in Inflammation-Associated Diseases

Eiconanoids have different modulating inflammation effects on cardiovascular system, brain, liver, and lung during pathological condition. Here, we summarized the effects of eiconanoids on inflammatory diseases in different tissues (Table 4). When these organs are damaged by inflammation caused by a variety of pathogenic factors, excessive inflammatory mediators including eicosanoids will be released locally, which can mediate the inflammatory reactions in local tissues (Wallace, 2019; Yao and Narumiya, 2019; Calder, 2020).

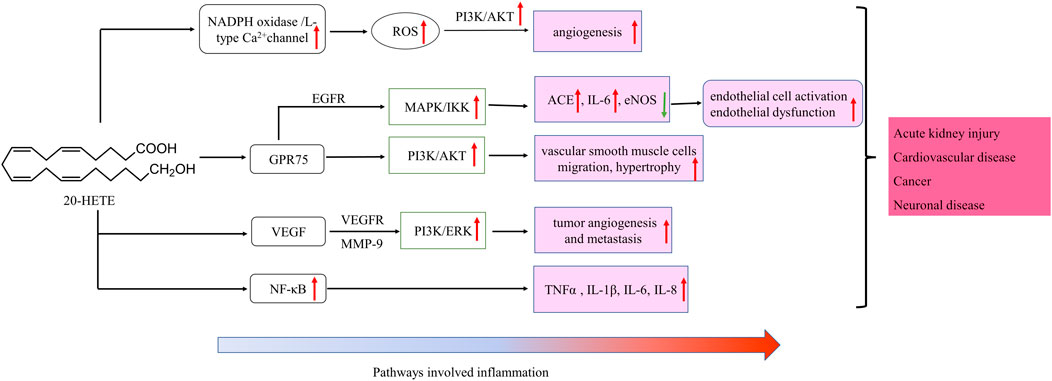

20-HETE is the major metabolite of arachidonic acid mediated by CYP ω-hydroxylase, which plays an important role in the regulation of cardiovascular disease, renal function disorder, carcinogenic condition, and other inflammatory diseases. CYP4A11 and CYP4F2 are the primary enzymes that mediate the formation of 20-HETE in human liver and kidney microsomes (Lasker et al., 2000). Vascular inflammation plays an important role in the occurrence of many diseases, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, and vascular remodeling. 20-HETE can promote vascular inflammation by increasing adhesion molecules and inflammatory cytokines due to endothelial cell activation (Hoopes et al., 2015). 20-HETE can activate nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and stimulate the production of inflammatory cytokines in human endothelial cells (Ishizuka et al., 2008). Recent studies have proved that 20-HETE could bind to the G-protein coupled receptor 75 (GPR75) to promote c-Src-mediated-EGFR and trigger the downstream MAPK pathway to induce ACE expression and endothelial dysfunction in human endothelial cells (Garcia et al., 2017; Pascale et al., 2021). 20-HETE/GPR75 also triggered PI3K/AKT pathway to promote vascular smooth muscle cells migration, hypertrophy. Moreover, 20-HETE/GPR75 is involved in the activation of intracellular signaling in prostate cancer cells, leading to the more aggressive phenotypic differentiation of PC-3 cells (Cárdenas et al., 2020). In endothelial cells, 20-HETE can promote reactive oxygen species (ROS) production through NADPH oxidase to activate the L-type Ca2+channel (Medhora et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2010; Bou-Fakhredin et al., 2021). In the ischemia-reperfusion injury, inhibition of 20-HETE synthesis reduced oxidative stress and the expression of vascular TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 (Regner et al., 2009; Hoff et al., 2011). In addition, Han et al. found that the use of 20-HETE synthesis inhibitor HET0016 to inhibit the synthesis of 20-HETE can reduce the volume of brain injury and neurological deficit, alleviating neuronal death, ROS production, gelation activity, and inflammatory reaction, which indicates that inhibition of 20-HETE synthesis protects brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage without inhibiting angiogenesis (Han et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2021). Inhibition of 20-HETE production can also attenuate kidney injury in a rodent model of acute kidney injury (AKI) induced by ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) (Hoff et al., 2011; Hoff et al., 2019). 20-HETE promotes tumor angiogenesis and metastasis by upregulation of VEGF and MMP-9 via PI3K and ERK1/2 signaling in the human NSCLC cells (Yu et al., 2011). Increased expression of CYP4A and CYP4F enzymes in human cancer tissues and the use of 20-HETE inhibitors and antagonists in the treatment of cancer have been reported (Amet et al., 1998).

In humans, 19-HETE is mainly synthesized by the CYP2C19 and CYP2E1 pathways, with less synthesis by the CYP ω-hydroxylase pathway (Shoieb et al., 2019). In normal physiology, 19-HETE can function as an endogenous antagonist of 20-HETE in mediating renal vasoconstriction by blocking the vasoconstriction of renal arterioles caused by 20-HETE (Shoieb et al., 2019). It has been reported that CYP-mediated 19-HETE has a strong correlation with cardiovascular events and can act as a prognostic marker for patients with acute coronary syndrome (Shoieb et al., 2019). It should be noted that 19-HETE was usually investigated as a racemic mixture, however, 19(S)-HETE was reported more active than 19(R)-HETE against Ang II-cell hypertrophy (Shoieb and El-Kadi, 2018). In the heart, 19-HETE is the major subterminal HETE formed in the cardiac tissue of rat, which not only plays a protective role in cardiac hypertrophy, but also participates in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney diseases (Kajiwara et al., 2013; El-Sherbeni and El-Kadi, 2014; Shoieb et al., 2019).

Cytochrome P450 ω-Hydroxylase-mediated Products of LTB4

LTB4 is an inflammatory mediator involved in inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, asthma and Alzheimer’s disease, which can be metabolized by CYP4F2, CYP4F3A and CYP4F3B to form 20-OH-LTB4 (Kalsotra and Strobel, 2006) (Lorenzetti et al., 2019) (Brain and Williams, 1990; Wang et al., 2008). LTB4 is converted by CYP4F to the more polar 20-OH-LTB4 in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) (Soberman et al., 1988). However, 20-OH-LTB4 expressed similar functional activity to LTB4, and similar binding characteristics with human PMN to LTB4. This indicated that the arachidonic acid metabolite oxidized at ω-site of LTB4 may be a more important inflammatory factor than LTB4 (Clancy et al., 1984). Analysis of peritoneal metabolites in patients with purulent peritonitis or non-performatives appendicitis revealed that 20-OH-LTB4 might be involved in the pathophysiological mechanisms of suppurative inflammation (Kikawa et al., 1986). A recent study showed that 20-OH-LTB4 might function as a potential biomarker for the diagnosis and risk assessment of intracerebral hemorrhage stroke (ICH) to distinguish the patients with ICH from healthy people and the patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS). This finding provides a new strategy for the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of ICH (Zhang et al., 2021). In mouse myeloid cells, Cyp4f18 (the functional orthologue of human PMN CYP4F3A) catalyzes the conversion of LTB4 to 19-OH-LTB4. Inhibition of Cyp4f18 led to a 220% increase in the PMN chemotaxis to LTB4 in mice (Christmas et al., 2006). While the ω-hydroxylated products of LTB4 play different physiological roles in some diseases, the mechanisms in inflammation are still unclear, which needs further study.

Cytochrome P450 ω-Hydroxylase-mediated Products of Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid

In vivo, EETs are not only hydrolyzed by sEH and mEH, but also metabolized by CYP ω-hydroxylases. EETs are one of the best endogenous substrates for rat Cyp4a subtypes so far. 8(9)-, 11(12)- and 14(15)-EET could be metabolized by rat Cyp4a into corresponding 19- and 20-hydroxylated EET (HEET) (Cowart et al., 2002). Cyp4a1 showed a higher affinity for 8(9)-EET, while Cyp4a2, Cyp4a3, and Cyp4a8 have a higher hydroxylase activity for 11 (12)-EET (Cowart et al., 2002). ω-HEETs could also serve as endogenous PPARα ligands (Muller et al., 2004). Muller et al. reported that CYP-dependent production of EET/HEET might be an anti-inflammatory index (Muller et al., 2004). However, there is no evidence to show the functions of ω-hydroxylation of EET in humans (Xu et al., 2011).

Cytochrome P450 ω-Hydroxylase-mediated Products of Prostaglandins

Since 1971, a series of studies have identified the Cyp4a hydroxylase family from multiple organs in rabbit and mouse liver (Kikuta et al., 2002). These enzymes catalyze the hydroxylation of multiple prostaglandins (PGE1, PGE2, PGF2, PGD2, PGA1, and PGA2) as well as ω- and (ω-1)-hydroxylation of palmitate. In humans, CYP4A11 can hydroxylate three PGH2 analogs (U51605, U44069, U46619), although it cannot hydroxylate PGH2 (Oliw et al., 2001). Moreover, PGH2 could be converted by CYP4F8 into 19(R)-OH-PGH2 in prostate, seminal vesicles, and several extrahepatic tissues (Oliw et al., 1988; Hardwick, 2008). PGE2 is closely related to the production of cytokines in antigen presenting cells and plays an important role in the stage of inflammatory regression, while 19(R)-OH-PGE2 is an agonist of PGE2 receptor (Serhan et al., 2007). At present, PGs have been studied extensively but little is known about the function of their hydroxylated products, and further studies are required to determine the function in various tissues and species.

Cytochrome P450 ω-Hydroxylase-mediated Eicosanoids and Cytokines

CYP ω-hydroxylase-mediated eicosanoids are also involved in the regulation of cytokines, especially 20-HETE in cardiovascular inflammation has been widely studied. Cheng et al. found that 20-HETE could mediate the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) uncoupling and endothelial dysfunction through activating tyrosine kinase, MAPK and IKK in bovine aortic endothelial cells (Cheng et al., 2010). In addition, 20-HETE can also stimulate NF-κB and MAPK/ERK to increase protein expression levels of IL-8 and adhesion molecule ICAM, leading to endothelial cell activation (Ishizuka et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2010). In the spontaneously hypertensive rat model, the inhibition of 20-HETE by HET006 (CYP ω-hydroxylase inhibitor) could significantly reduce oxidative stress and the mRNA expression of TNFα and IL-1β, and the NF-κB activation (Toth et al., 2013). Cheng et al. developed a new constitutively stimulated 20-HETE biosynthesis mouse model, the Tie2-CYP4F2-Tr mouse. By activating the NADPH oxidase and VEGF pathway, the model has the phenotypic characteristics of oxidative stress, increased expression of NADPH oxidase and IL-6, and increased cell proliferation and angiogenesis, which can be used to further study the physiopathological effect of 20-HETE in the cardiovascular system (Cheng et al., 2014).

Conclusion

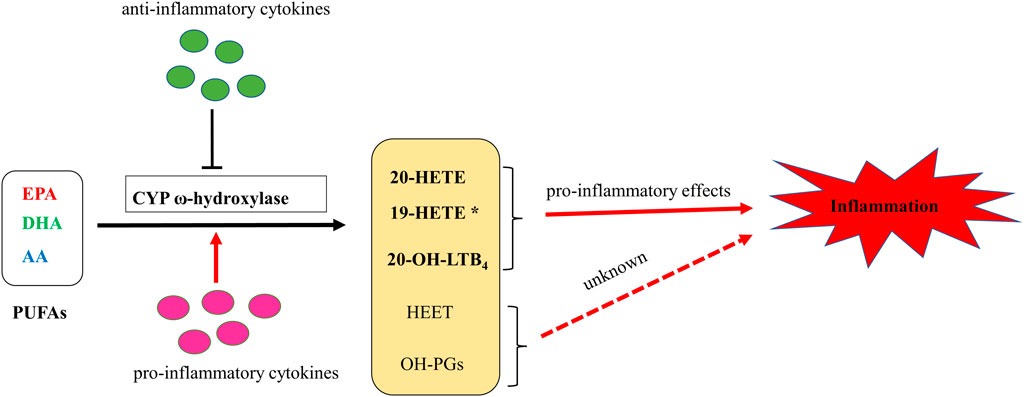

CYP ω-hydroxylase and metabolite have been reported to play an important role in the inflammatory process (Figure 2). In a variety of inflammatory diseases, the activity of CYP ω-hydroxylase is regulated by inflammatory factors. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, can increase CYP ω-hydroxylase activity, whereas anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 can inhibit CTP hydroxylase expression. Therefore, the production of metabolites of these hydroxylases are affected accordingly. At present, a large number of studies showed that 20-HETE could modulate inflammatory processes (Figure 3). However, little is known about the role of other CYP hydroxylated products in inflammation. 20-HETE can increase the production of adhesion molecules and inflammatory cytokines as well as ROS level through the activation of NF-κB, MAPK pathway, and NADPH oxidase, to activate endothelial cell activation, promote cell proliferation and regulate endothelial dysfunction. The accumulation of inflammatory factors will also affect the activity of CYP ω-hydroxylases to promote the metabolism of eicosanoids and form a positive feedback regulation, further affecting the progress of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, inflammation and other diseases. Elucidation of the effects of inflammation and infection on the metabolism of CYP hydroxylase and eicosanoids and the relationship between specific cytokines and their mediated of CYP enzymes will help in-depth understanding about the pathogenesis of many diseases and update therapeutic strategies. However, due to the complexity of the cytokines involved in the inflammatory process and their signaling pathways, there has not been a consensus on its potential mechanism. Regulation of the expression or activity of CYP ω-hydroxylase may play a role in the treatment of inflammatory diseases. For the translational and clinical research of CYP-ω-hydroxylase, inducers and inhibitors of CYP-ω- hydroxylase may be novel therapeutic strategies for many clinical inflammatory diseases. In addition, CYP-ω-hydroxyase also could be used as the marker for the diagnosis of related difficult and complicated diseases, improving the existing diagnostic methods. Therefore, more researches are needed to further clarify the mechanism of CYP ω-hydroxylase to advance the translational and clinical studies of CYP ω-hydroxylases.

FIGURE 2. A putative schematic diagram of molecular mechanisms of CYP ω-hydroxylases-mediated eicosanoids on inflammation. * 19-HETE may take a pro-inflammatory role in chronic kidney disease. However, it may also act as an anti-inflammatory mediator since it antagonized 20-HETE-induced inflammation. In addition, 19(S)-HETE was reported to be more active than 19(R)-HETE against Ang II-cell hypertrophy.

FIGURE 3. Schematic of signaling cascades involving 20-HETE in inflammation disease. ↑: up-regulation; ↓: down-regulation. IL, interleukin; LOX, MAPK/ERK, the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor, VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-Kinases.

Author Contributions

K-DN and J-YL designed the paper frame; K-DN wrote the draft; J-YL critically revised and finalized the paper. K-DN and J-YL approved the final version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Al-Anizy, M., Horley, N. J., Kuo, C. W., Gillett, L. C., Laughton, C. A., Kendall, D., et al. (2006). Cytochrome P450 Cyp4x1 Is a Major P450 Protein in Mouse Brain. Febs j 273 (5), 936–947. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05119.x

Amet, Y., Adas, F., and Nanji, A. A. (1998). Fatty Acid omega- and (omega-1)-hydroxylation in Experimental Alcoholic Liver Disease: Relationship to Different Dietary Fatty Acids. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 22 (7), 1493–1500. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03941.x

Anwar-mohamed, A., Zordoky, B. N., Aboutabl, M. E., and El-Kadi, A. O. (2010). Alteration of Cardiac Cytochrome P450-Mediated Arachidonic Acid Metabolism in Response to Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Systemic Inflammation. Pharmacol. Res. 61 (5), 410–418. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2009.12.015

Arinç, E., and Philpot, M. (1976). Preparation and Properties of Partially Purified Pulmonary Cytochrome P-450 from Rabbits. J. Biol. Chem. 251 (11), 3213–3220. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(17)33425-7

Ashkar, S., Mesentsev, A., Zhang, W. X., Mastyugin, V., Dunn, M. W., and Laniado-Schwartzman, M. (2004). Retinoic Acid Induces Corneal Epithelial CYP4B1 Gene Expression and Stimulates the Synthesis of Inflammatory 12-hydroxyeicosanoids. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 20 (1), 65–74. doi:10.1089/108076804772745473

Baer, B. R., and Rettie, A. E. (2006). CYP4B1: an Enigmatic P450 at the Interface between Xenobiotic and Endobiotic Metabolism. Drug Metab. Rev. 38 (3), 451–476. doi:10.1080/03602530600688503

Baldarelli, R. M., Smith, C. M., Finger, J. H., Hayamizu, T. F., McCright, I. J., Xu, J., et al. (2021). The Mouse Gene Expression Database (GXD): 2021 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 (D1), D924–d931. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa914

Bellamine, A., Wang, Y., Waterman, M. R., Gainer, J. V., Dawson, E. P., Brown, N. J., et al. (2003). Characterization of the CYP4A11 Gene, a Second CYP4A Gene in Humans. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 409 (1), 221–227. doi:10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00545-3

Bou-Fakhredin, R., Dia, B., Ghadieh, H. E., Rivella, S., Cappellini, M. D., Eid, A. A., et al. (2021). CYP450 Mediates Reactive Oxygen Species Production in a Mouse Model of β-Thalassemia through an Increase in 20-HETE Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (3), 1106. doi:10.3390/ijms22031106

Brain, S. D., and Williams, T. J. (1990). Leukotrienes and Inflammation. Pharmacol. Ther. 46 (1), 57–66. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(90)90035-z

Bruijnzeel, P., Storz, E., van der Donk, E., and Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C. (1993). Skin Eosinophilia in Patients with Allergic Asthma, Patients with Nonallergic Asthma, and Healthy Controls. II: 20-Hydroxy-Leukotriene B4 Is a Potent In Vivo and In Vitro Eosinophil Chemotactic Factor in Nonallergic Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 91 (2), 634–642. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(93)90269-l

Bumpus, N. N., and Johnson, E. F. (2011). 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxyamide-ribonucleoside (AICAR)-stimulated Hepatic Expression of Cyp4a10, Cyp4a14, Cyp4a31, and Other Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α-responsive Mouse Genes Is AICAR 5'-monophosphate-dependent and AMP-Activated Protein Kinase-independent. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 339 (3), 886–895. doi:10.1124/jpet.111.184242

Bylund, J., Harder, A. G., Maier, K. G., Roman, R. J., and Harder, D. R. (2003). Leukotriene B4 omega-side Chain Hydroxylation by CYP4F5 and CYP4F6. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 412 (1), 34–41. doi:10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00030-4

Cárdenas, S., Colombero, C., Panelo, L., Dakarapu, R., Falck, J. R., Costas, M. A., et al. (2020). GPR75 Receptor Mediates 20-HETE-Signaling and Metastatic Features of Androgen-Insensitive Prostate Cancer Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cel Biol Lipids 1865 (2), 158573. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.158573

Chen, L., Tang, S., Zhang, F. F., Garcia, V., Falck, J. R., Schwartzman, M. L., et al. (2019). CYP4A/20-HETE Regulates Ischemia-Induced Neovascularization via its Actions on Endothelial Progenitor and Preexisting Endothelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 316 (6), H1468–h1479. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00690.2018

Cheng, J., Edin, M. L., Hoopes, S. L., Li, H., Bradbury, J. A., Graves, J. P., et al. (2014). Vascular Characterization of Mice with Endothelial Expression of Cytochrome P450 4F2. Faseb j 28 (7), 2915–2931. doi:10.1096/fj.13-241927

Cheng, J., Wu, C. C., Gotlinger, K. H., Zhang, F., Falck, J. R., Narsimhaswamy, D., et al. (2010). 20-hydroxy-5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic Acid Mediates Endothelial Dysfunction via IkappaB Kinase-dependent Endothelial Nitric-Oxide Synthase Uncoupling. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 332 (1), 57–65. doi:10.1124/jpet.109.159863

Choudhary, D., Jansson, I., Schenkman, J. B., Sarfarazi, M., and Stoilov, I. (2003). Comparative Expression Profiling of 40 Mouse Cytochrome P450 Genes in Embryonic and Adult Tissues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 414 (1), 91–100. doi:10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00174-7

Choudhary, D., Jansson, I., Stoilov, I., Sarfarazi, M., and Schenkman, J. B. (2005). Expression Patterns of Mouse and Human CYP Orthologs (Families 1-4) during Development and in Different Adult Tissues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 436 (1), 50–61. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2005.02.001

Christmas, P., Jones, J. P., Patten, C. J., Rock, D. A., Zheng, Y., Cheng, S. M., et al. (2001). Alternative Splicing Determines the Function of CYP4F3 by Switching Substrate Specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (41), 38166–38172. doi:10.1074/jbc.M104818200

Christmas, P., Tolentino, K., Primo, V., Berry, K. Z., Murphy, R. C., Chen, M., et al. (2006). Cytochrome P-450 4F18 Is the Leukotriene B4 omega-1/omega-2 Hydroxylase in Mouse Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes: Identification as the Functional Orthologue of Human Polymorphonuclear Leukocyte CYP4F3A in the Down-Regulation of Responses to LTB4. J. Biol. Chem. 281 (11), 7189–7196. doi:10.1074/jbc.M513101200

Chuang, S. S., Helvig, C., Taimi, M., Ramshaw, H. A., Collop, A. H., Amad, M., et al. (2004). CYP2U1, a Novel Human Thymus- and Brain-specific Cytochrome P450, Catalyzes omega- and (omega-1)-hydroxylation of Fatty Acids. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (8), 6305–6314. doi:10.1074/jbc.M311830200

Clancy, R. M., Dahinden, C. A., and Hugli, T. E. (1984). Oxidation of Leukotrienes at the omega End: Demonstration of a Receptor for the 20-hydroxy Derivative of Leukotriene B4 on Human Neutrophils and Implications for the Analysis of Leukotriene Receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 81 (18), 5729–5733. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.18.5729

Colombero, C., Cárdenas, S., Venara, M., Martin, A., Pennisi, P., Barontini, M., et al. (2020). Cytochrome 450 Metabolites of Arachidonic Acid (20-HETE, 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET) Promote Pheochromocytoma Cell Growth and Tumor Associated Angiogenesis. Biochimie 171-172, 147–157. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2020.02.014

Cowart, L. A., Wei, S., Hsu, M. H., Johnson, E. F., Krishna, M. U., Falck, J. R., et al. (2002). The CYP4A Isoforms Hydroxylate Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids to Form High Affinity Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 277 (38), 35105–35112. doi:10.1074/jbc.M201575200

Cui, W., Wu, X., Shi, Y., Guo, W., Luo, J., Liu, H., et al. (2021). 20-HETE Synthesis Inhibition Attenuates Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neuronal Apoptosis via the SIRT1/PGC-1α Pathway: A Translational Study. Cell Prolif 54 (2), e12964. doi:10.1111/cpr.12964

Cui, X., Kalsotra, A., Robida, A. M., Matzilevich, D., Moore, A. N., Boehme, C. L., et al. (2003). Expression of Cytochromes P450 4F4 and 4F5 in Infection and Injury Models of Inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1619 (3), 325–331. doi:10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00491-9

Devos, A., Lino Cardenas, C. L., Glowacki, F., Engels, A., Lo-Guidice, J. M., Chevalier, D., et al. (2010). Genetic Polymorphism of CYP2U1, a Cytochrome P450 Involved in Fatty Acids Hydroxylation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 83 (2), 105–110. doi:10.1016/j.plefa.2010.06.005

Dhers, L., Ducassou, L., Boucher, J. L., and Mansuy, D. (2017). Cytochrome P450 2U1, a Very peculiar Member of the Human P450s Family. Cell Mol Life Sci 74 (10), 1859–1869. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2443-3

Edson, K. Z., and Rettie, A. E. (2013). CYP4 Enzymes as Potential Drug Targets: Focus on Enzyme Multiplicity, Inducers and Inhibitors, and Therapeutic Modulation of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid (20-HETE) Synthase and Fatty Acid ω-hydroxylase Activities. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 13 (12), 1429–1440. doi:10.2174/15680266113139990110

El-Sherbeni, A. A., and El-Kadi, A. O. (2014). Alterations in Cytochrome P450-Derived Arachidonic Acid Metabolism during Pressure Overload-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 87 (3), 456–466. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.015

Elfaki, I., Mir, R., Almutairi, F. M., and Duhier, F. M. A. (2018). Cytochrome P450: Polymorphisms and Roles in Cancer, Diabetes and Atherosclerosis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 19 (8), 2057–2070. doi:10.22034/apjcp.2018.19.8.2057

Elkhatali, S., El-Sherbeni, A. A., Elshenawy, O. H., Abdelhamid, G., and El-Kadi, A. O. (2015). 19-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid and Isoniazid Protect against Angiotensin II-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 289 (3), 550–559. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2015.10.003

Elshenawy, O. H., Shoieb, S. M., Mohamed, A., and El-Kadi, A. O. (2017). Clinical Implications of 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid in the Kidney, Liver, Lung and Brain: An Emerging Therapeutic Target. Pharmaceutics 9 (1), 9. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics9010009

Eun, H. S., Cho, S. Y., Lee, B. S., Seong, I. O., and Kim, K. H. (2018). Profiling Cytochrome P450 Family 4 Gene Expression in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 18 (6), 4865–4876. doi:10.3892/mmr.2018.9526

Fan, F., Ge, Y., Lv, W., Elliott, M. R., Muroya, Y., Hirata, T., et al. (2016). Molecular Mechanisms and Cell Signaling of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid in Vascular Pathophysiology. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed. 21, 1427–1463. doi:10.2741/4465

Fan, F., and Roman, R. J. (2017). Effect of Cytochrome P450 Metabolites of Arachidonic Acid in Nephrology. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28 (10), 2845–2855. doi:10.1681/asn.2017030252

Fer, M., Corcos, L., Dréano, Y., Plée-Gautier, E., Salaün, J. P., Berthou, F., et al. (2008). Cytochromes P450 from Family 4 Are the Main omega Hydroxylating Enzymes in Humans: CYP4F3B Is the Prominent Player in PUFA Metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 49 (11), 2379–2389. doi:10.1194/jlr.M800199-JLR200

Garcia, V., Gilani, A., Shkolnik, B., Pandey, V., Zhang, F. F., Dakarapu, R., et al. (2017). 20-HETE Signals through G-Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR75 (Gq) to Affect Vascular Function and Trigger Hypertension. Circ. Res. 120 (11), 1776–1788. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310525

Guengerich, F. P. (2001). Common and Uncommon Cytochrome P450 Reactions Related to Metabolism and Chemical Toxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14 (6), 611–650. doi:10.1021/tx0002583

Guengerich, F. P., Waterman, M. R., and Egli, M. (2016). Recent Structural Insights into Cytochrome P450 Function. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 37 (8), 625–640. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2016.05.006

Guo, M., Roman, R. J., Falck, J. R., Edwards, P. A., and Scicli, A. G. (2005). Human U251 Glioma Cell Proliferation Is Suppressed by HET0016 [N-Hydroxy-N'-(4-Butyl-2-Methylphenyl)formamidine], a Selective Inhibitor of CYP4A. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 315 (2), 526–533. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.088567

Han, X., Zhao, X., Lan, X., Li, Q., Gao, Y., Liu, X., et al. (2019). 20-HETE Synthesis Inhibition Promotes Cerebral protection after Intracerebral Hemorrhage without Inhibiting Angiogenesis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 39 (8), 1531–1543. doi:10.1177/0271678X18762645

Hardwick, J. P. (2008). Cytochrome P450 omega Hydroxylase (CYP4) Function in Fatty Acid Metabolism and Metabolic Diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 75 (12), 2263–2275. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2008.03.004

Hariparsad, N., Chu, X., Yabut, J., Labhart, P., Hartley, D. P., Dai, X., et al. (2009). Identification of Pregnane-X Receptor Target Genes and Coactivator and Corepressor Binding to Promoter Elements in Human Hepatocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 (4), 1160–1173. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn1047

Hirani, V., Yarovoy, A., Kozeska, A., Magnusson, R. P., and Lasker, J. M. (2008). Expression of CYP4F2 in Human Liver and Kidney: Assessment Using Targeted Peptide Antibodies. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 478 (1), 59–68. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2008.06.025

Hoff, U., Bubalo, G., Fechner, M., Blum, M., Zhu, Y., Pohlmann, A., et al. (2019). A Synthetic Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid Analogue Prevents the Initiation of Ischemic Acute Kidney Injury. Acta Physiol. (Oxf) 227 (2), e13297. doi:10.1111/apha.13297

Hoff, U., Lukitsch, I., Chaykovska, L., Ladwig, M., Arnold, C., Manthati, V. L., et al. (2011). Inhibition of 20-HETE Synthesis and Action Protects the Kidney from Ischemia/reperfusion Injury. Kidney Int. 79 (1), 57–65. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.377

Holla, V. R., Adas, F., Imig, J. D., Zhao, X., Price, E., Olsen, N., et al. (2001). Alterations in the Regulation of Androgen-Sensitive Cyp 4a Monooxygenases Cause Hypertension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 98 (9), 5211–5216. doi:10.1073/pnas.081627898

Hoopes, S. L., Garcia, V., Edin, M. L., Schwartzman, M. L., and Zeldin, D. C. (2015). Vascular Actions of 20-HETE. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 120, 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2015.03.002

Hrycay, E. G., and Bandiera, S. M. (2009). Expression, Function and Regulation of Mouse Cytochrome P450 Enzymes: Comparison with Human P450 Enzymes. Curr. Drug Metab. 10 (10), 1151–1183. doi:10.2174/138920009790820138

Hsu, M. H., Savas, U., Griffin, K. J., and Johnson, E. F. (2007). Human Cytochrome P450 Family 4 Enzymes: Function, Genetic Variation and Regulation. Drug Metab. Rev. 39 (2-3), 515–538. doi:10.1080/03602530701468573

Hsu, M. H., Savas, U., Lasker, J. M., and Johnson, E. F. (2011). Genistein, Resveratrol, and 5-Aminoimidazole-4-Carboxamide-1-β-D-Ribofuranoside Induce Cytochrome P450 4F2 Expression through an AMP-Activated Protein Kinase-dependent Pathway. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 337 (1), 125–136. doi:10.1124/jpet.110.175851

Imig, J. D. (2013). Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids, 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid, and Renal Microvascular Function. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 104-105, 2–7. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2013.01.002

Ishizuka, T., Cheng, J., Singh, H., Vitto, M. D., Manthati, V. L., Falck, J. R., et al. (2008). 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid Stimulates Nuclear Factor-kappaB Activation and the Production of Inflammatory Cytokines in Human Endothelial Cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 324 (1), 103–110. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.130336

Jenkins, R. E., Kitteringham, N. R., Hunter, C. L., Webb, S., Hunt, T. J., Elsby, R., et al. (2006). Relative and Absolute Quantitative Expression Profiling of Cytochromes P450 Using Isotope-Coded Affinity Tags. Proteomics 6 (6), 1934–1947. doi:10.1002/pmic.200500432

Johnson, A. L., Edson, K. Z., Totah, R. A., and Rettie, A. E. (2015). Cytochrome P450 ω-Hydroxylases in Inflammation and Cancer. Adv. Pharmacol. 74, 223–262. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2015.05.002

Kajiwara, A., Saruwatari, J., Kita, A., Kamihashi, R., Miyagawa, H., Sakata, M., et al. (2013). Sex Differences in the Effect of Cytochrome P450 2C19 Polymorphisms on the Risk of Diabetic Retinopathy: a Retrospective Longitudinal Study in Japanese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Pharmacogenet Genomics 23 (12), 717–720. doi:10.1097/fpc.0000000000000009

Kalsotra, A., Anakk, S., Brommer, C. L., Kikuta, Y., Morgan, E. T., and Strobel, H. W. (2007a). Catalytic Characterization and Cytokine Mediated Regulation of Cytochrome P450 4Fs in Rat Hepatocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 461 (1), 104–112. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.027

Kalsotra, A., and Strobel, H. W. (2006). Cytochrome P450 4F Subfamily: at the Crossroads of Eicosanoid and Drug Metabolism. Pharmacol. Ther. 112 (3), 589–611. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.03.008

Kalsotra, A., Zhao, J., Anakk, S., Dash, P. K., and Strobel, H. W. (2007b). Brain Trauma Leads to Enhanced Lung Inflammation and Injury: Evidence for Role of P4504Fs in Resolution. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27 (5), 963–974. doi:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600396

Karlgren, M., Backlund, M., Johansson, I., Oscarson, M., and Ingelman-Sundberg, M. (2004). Characterization and Tissue Distribution of a Novel Human Cytochrome P450-Cyp2u1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 315 (3), 679–685. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.110

Kikawa, Y., Shigematsu, Y., and Sudo, M. (1986). Leukotriene B4 and 20-OH-LTB4 in Purulent Peritoneal Exudates Demonstrated by GC-MS. Prostaglandins Leukot. Med. 23 (1), 85–94. doi:10.1016/0262-1746(86)90080-6

Kikuta, Y., Kusunose, E., Endo, K., Yamamoto, S., Sogawa, K., Fujii-Kuriyama, Y., et al. (1993). A Novel Form of Cytochrome P-450 Family 4 in Human Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes. cDNA Cloning and Expression of Leukotriene B4 omega-hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 268 (13), 9376–9380. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)98360-2

Kikuta, Y., Kusunose, E., and Kusunose, M. (2002). Prostaglandin and Leukotriene omega-hydroxylases. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 68-69, 345–362. doi:10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00039-4

Kikuta, Y., Miyauchi, Y., Kusunose, E., and Kusunose, M. (1999). Expression and Molecular Cloning of Human Liver Leukotriene B4 omega-hydroxylase (CYP4F2) Gene. DNA Cel Biol 18 (9), 723–730. doi:10.1089/104454999315006

Kikuta, Y., Yamashita, Y., Kashiwagi, S., Tani, K., Okada, K., and Nakata, K. (2004). Expression and Induction of CYP4F Subfamily in Human Leukocytes and HL60 Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1683 (1-3), 7–15. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.03.007

Koonin, E. V. (2005). Orthologs, Paralogs, and Evolutionary Genomics. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39, 309–338. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.114725

Kroetz, D. L., and Xu, F. (2005). Regulation and Inhibition of Arachidonic Acid omega-hydroxylases and 20-HETE Formation. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 45, 413–438. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.100045

Lasker, J. M., Chen, W. B., Wolf, I., Bloswick, B. P., Wilson, P. D., and Powell, P. K. (2000). Formation of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid, a Vasoactive and Natriuretic Eicosanoid, in Human Kidney. Role of Cyp4F2 and Cyp4A11. J. Biol. Chem. 275 (6), 4118–4126. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.6.4118

Li, A., Jiao, X., Munier, F. L., Schorderet, D. F., Yao, W., Iwata, F., et al. (2004). Bietti Crystalline Corneoretinal Dystrophy Is Caused by Mutations in the Novel Gene CYP4V2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 (5), 817–826. doi:10.1086/383228

Li, J., Li, D., Tie, C., Wu, J., Wu, Q., and Li, Q. (2015). Cisplatin-mediated Cytotoxicity through Inducing CYP4A 11 Expression in Human Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells. J. Toxicol. Sci. 40 (6), 895–900. doi:10.2131/jts.40.895

Liu, J., Wang, J., Huang, Q., Higdon, J., Magdaleno, S., Curran, T., et al. (2006). Gene Expression Profiles of Mouse Retinas during the Second and Third Postnatal Weeks. Brain Res. 1098 (1), 113–125. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.086

Liu, Y., Tang, H., Liu, X., Chen, H., Feng, N., Zhang, J., et al. (2019). Frontline Science: Reprogramming COX-2, 5-LOX, and CYP4A-Mediated Arachidonic Acid Metabolism in Macrophages by Salidroside Alleviates Gouty Arthritis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 105 (1), 11–24. doi:10.1002/JLB.3HI0518-193R

Lorenzetti, F., Vera, M. C., Ceballos, M. P., Ronco, M. T., Pisani, G. B., Monti, J. A., et al. (2019). Participation of 5-lipoxygenase and LTB4 in Liver Regeneration after Partial Hepatectomy. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 18176. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54652-7

Luo, B., Chen, C., Wu, X., Yan, D., Chen, F., Yu, X., et al. (2020). Cytochrome P450 2U1 Is a Novel Independent Prognostic Biomarker in Breast Cancer Patients. Front. Oncol. 10, 1379. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.01379

Luo, Y., and Liu, J. Y. (2020). Pleiotropic Functions of Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase-Derived Eicosanoids in Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 580897. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.580897

Manikandan, P., and Nagini, S. (2018). Cytochrome P450 Structure, Function and Clinical Significance: A Review. Curr. Drug Targets 19 (1), 38–54. doi:10.2174/1389450118666170125144557

McIntosh, J. A., Farwell, C. C., and Arnold, F. H. (2014). Expanding P450 Catalytic Reaction Space through Evolution and Engineering. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 19, 126–134. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.02.001

Medhora, M., Chen, Y., Gruenloh, S., Harland, D., Bodiga, S., Zielonka, J., et al. (2008). 20-HETE Increases Superoxide Production and Activates NAPDH Oxidase in Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cel Mol Physiol 294 (5), L902–L911. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00278.2007

Miyata, N., Seki, T., Tanaka, Y., Omura, T., Taniguchi, K., Doi, M., et al. (2005). Beneficial Effects of a New 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid Synthesis Inhibitor, TS-011 [N-(3-chloro-4-morpholin-4-yl) Phenyl-N'-Hydroxyimido Formamide], on Hemorrhagic and Ischemic Stroke. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314 (1), 77–85. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.083964

Muller, D. N., Theuer, J., Shagdarsuren, E., Kaergel, E., Honeck, H., Park, J. K., et al. (2004). A Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Alpha Activator Induces Renal CYP2C23 Activity and Protects from Angiotensin II-Induced Renal Injury. Am. J. Pathol. 164 (2), 521–532. doi:10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63142-2

Nelson, D. R. (2018). Cytochrome P450 Diversity in the Tree of Life. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom 1866 (1), 141–154. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.05.003

Nelson, D. R., Zeldin, D. C., Hoffman, S. M., Maltais, L. J., Wain, H. M., and Nebert, D. W. (2004). Comparison of Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Genes from the Mouse and Human Genomes, Including Nomenclature Recommendations for Genes, Pseudogenes and Alternative-Splice Variants. Pharmacogenetics 14 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1097/00008571-200401000-00001

Nunna, V., Jalal, N., and Bureik, M. (2017). Anti-CYP4Z1 Autoantibodies Detected in Breast Cancer Patients. Cell Mol Immunol 14 (6), 572–574. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.21

Oliw, E. H., Kinn, A. C., and Kvist, U. (1988). Biochemical Characterization of Prostaglandin 19-hydroxylase of Seminal Vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 263 (15), 7222–7227. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)68631-4

Oliw, E. H., Stark, K., and Bylund, J. (2001). Oxidation of Prostaglandin H(2) and Prostaglandin H(2) Analogues by Human Cytochromes P450: Analysis of omega-side Chain Hydroxy Metabolites and Four Steroisomers of 5-hydroxyprostaglandin I(1) by Mass Spectrometry. Biochem. Pharmacol. 62 (4), 407–415. doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00683-9

Ortiz de Montellano, P. R. (2019). Acetylenes: Cytochrome P450 Oxidation and Mechanism-Based Enzyme Inactivation. Drug Metab. Rev. 51 (2), 162–177. doi:10.1080/03602532.2019.1632891

Pascale, J. V., Park, E. J., Adebesin, A. M., Falck, J. R., Schwartzman, M. L., and Garcia, V. (2021). Uncovering the Signalling, Structure and Function of the 20‐HETE‐GPR75 Pairing: Identifying the Chemokine CCL5 as a Negative Regulator of GPR75. Br. J. Pharmacol. 178, 3813–3828. doi:10.1111/bph.15525

Powell, P. K., Wolf, I., Jin, R., and Lasker, J. M. (1998). Metabolism of Arachidonic Acid to 20-hydroxy-5,8,11, 14-eicosatetraenoic Acid by P450 Enzymes in Human Liver: Involvement of CYP4F2 and CYP4A11. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 285 (3), 1327–1336.

Rådmark, O., Werz, O., Steinhilber, D., and Samuelsson, B. (2015). 5-Lipoxygenase, a Key Enzyme for Leukotriene Biosynthesis in Health and Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1851 (4), 331–339. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.08.012

Reckelhoff, J. F. (2005). Sex Steroids, Cardiovascular Disease, and Hypertension: Unanswered Questions and Some Speculations. Hypertension 45 (2), 170–174. doi:10.1161/01.Hyp.0000151825.36598.36

Regner, K. R., Zuk, A., Van Why, S. K., Shames, B. D., Ryan, R. P., Falck, J. R., et al. (2009). Protective Effect of 20-HETE Analogues in Experimental Renal Ischemia Reperfusion Injury. Kidney Int. 75 (5), 511–517. doi:10.1038/ki.2008.600

Sato, M., Ishii, T., Kobayashi-Matsunaga, Y., Amada, H., Taniguchi, K., Miyata, N., et al. (2001). Discovery of a N'-hydroxyphenylformamidine Derivative HET0016 as a Potent and Selective 20-HETE Synthase Inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 11 (23), 2993–2995. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00614-x

Savas, U., Hsu, M. H., and Johnson, E. F. (2003). Differential Regulation of Human CYP4A Genes by Peroxisome Proliferators and Dexamethasone. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 409 (1), 212–220. doi:10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00499-x

Schunck, W. H., Konkel, A., Fischer, R., and Weylandt, K. H. (2018). Therapeutic Potential of omega-3 Fatty Acid-Derived Epoxyeicosanoids in Cardiovascular and Inflammatory Diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 183, 177–204. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.10.016

Serhan, C. N., Brain, S. D., Buckley, C. D., Gilroy, D. W., Haslett, C., O'Neill, L. A., et al. (2007). Resolution of Inflammation: State of the Art, Definitions and Terms. Faseb j 21 (2), 325–332. doi:10.1096/fj.06-7227rev

Shak, S., and Goldstein, I. M. (1984). Omega-oxidation Is the Major Pathway for the Catabolism of Leukotriene B4 in Human Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 259 (16), 10181–10187. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)90946-4

Shoieb, S. M., and El-Kadi, A. O. S. (2018). S-enantiomer of 19-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid Preferentially Protects against Angiotensin II-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy. Drug Metab. Dispos 46 (8), 1157–1168. doi:10.1124/dmd.118.082073

Shoieb, S. M., El-Sherbeni, A. A., and El-Kadi, A. O. S. (2019). Subterminal Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acids: Crucial Lipid Mediators in normal Physiology and Disease States. Chem. Biol. Interact 299, 140–150. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2018.12.004

Shon, J. C., Phuc, N. M., Kim, W. C., Heo, J. K., Wu, Z., Lee, H., et al. (2017). Acetylshikonin Is a Novel Non-selective Cytochrome P450 Inhibitor. Biopharm. Drug Dispos 38 (9), 553–556. doi:10.1002/bdd.2101

Simpson, A. E. (1997). The Cytochrome P450 4 (CYP4) Family. Gen. Pharmacol. 28 (3), 351–359. doi:10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00246-7

Smith, W. L., and Song, I. (2002). The Enzymology of Prostaglandin Endoperoxide H Synthases-1 and -2. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 68-69, 115–128. doi:10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00025-4

Soberman, R. J., Sutyak, J. P., Okita, R. T., Wendelborn, D. F., Roberts, L. J., Austen, K. F., et al. (1988). The Identification and Formation of 20-aldehyde Leukotriene B4. J. Biol. Chem. 263 (17), 7996–8002. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)68432-7

Sun, Q., Harper, T. W., Dierks, E. A., Zhang, L., Chang, S., Rodrigues, A. D., et al. (2011). 1-Aminobenzotriazole, a Known Cytochrome P450 Inhibitor, Is a Substrate and Inhibitor of N-Acetyltransferase. Drug Metab. Dispos 39 (9), 1674–1679. doi:10.1124/dmd.111.039834

Toth, P., Csiszar, A., Sosnowska, D., Tucsek, Z., Cseplo, P., Springo, Z., et al. (2013). Treatment with the Cytochrome P450 ω-hydroxylase Inhibitor HET0016 Attenuates Cerebrovascular Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Improves Vasomotor Function in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 168 (8), 1878–1888. doi:10.1111/bph.12079

Urlacher, V. B., and Girhard, M. (2012). Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenases: an Update on Perspectives for Synthetic Application. Trends Biotechnol. 30 (1), 26–36. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.06.012

Wallace, J. L. (2019). Eicosanoids in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Br. J. Pharmacol. 176 (8), 1000–1008. doi:10.1111/bph.14178

Wang, B., Zheng, L., Chou, J., Li, C., Zhang, Y., Meng, X., et al. (2016). CYP4Z1 3'UTR Represses Migration of Human Breast Cancer Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 478 (2), 900–907. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.048

Wang, C., Li, Y., Chen, H., Zhang, J., Zhang, J., Qin, T., et al. (2017). Inhibition of CYP4A by a Novel Flavonoid FLA-16 Prolongs Survival and Normalizes Tumor Vasculature in Glioma. Cancer Lett. 402, 131–141. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2017.05.030

Wang, Y., Zhao, J., Kalsotra, A., Turman, C. M., Grill, R. J., Dash, P. K., et al. (2008). CYP4Fs Expression in Rat Brain Correlates with Changes in LTB4 Levels after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 25 (10), 1187–1194. doi:10.1089/neu.2008.0542

Ward, N. C., Puddey, I. B., Hodgson, J. M., Beilin, L. J., and Croft, K. D. (2005). Urinary 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid Excretion Is Associated with Oxidative Stress in Hypertensive Subjects. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38 (8), 1032–1036. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.024

Waring, R. H. (2020). Cytochrome P450: Genotype to Phenotype. Xenobiotica 50 (1), 9–18. doi:10.1080/00498254.2019.1648911

Westphal, C., Konkel, A., and Schunck, W. H. (2011). CYP-eicosanoids--a New Link between omega-3 Fatty Acids and Cardiac Disease?. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 96 (1-4), 99–108. doi:10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2011.09.001

Wu, C. C., Mei, S., Cheng, J., Ding, Y., Weidenhammer, A., Garcia, V., et al. (2013). Androgen-sensitive Hypertension Associates with Upregulated Vascular CYP4A12-20-HETE Synthase. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24 (8), 1288–1296. doi:10.1681/asn.2012070714

Xu, X., Zhang, X. A., and Wang, D. W. (2011). The Roles of CYP450 Epoxygenases and Metabolites, Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids, in Cardiovascular and Malignant Diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 63 (8), 597–609. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.006

Yang, X., Hutter, M., Goh, W. W. B., and Bureik, M. (2017). CYP4Z1 - A Human Cytochrome P450 Enzyme that Might Hold the Key to Curing Breast Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 23 (14), 2060–2064. doi:10.2174/1381612823666170207150156

Yao, C., and Narumiya, S. (2019). Prostaglandin-cytokine Crosstalk in Chronic Inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 176 (3), 337–354. doi:10.1111/bph.14530

Yu, W., Chai, H., Li, Y., Zhao, H., Xie, X., Zheng, H., et al. (2012). Increased Expression of CYP4Z1 Promotes Tumor Angiogenesis and Growth in Human Breast Cancer. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 264 (1), 73–83. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2012.07.019

Yu, W., Chen, L., Yang, Y. Q., Falck, J. R., Guo, A. M., Li, Y., et al. (2011). Cytochrome P450 ω-hydroxylase Promotes Angiogenesis and Metastasis by Upregulation of VEGF and MMP-9 in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 68 (3), 619–629. doi:10.1007/s00280-010-1521-8

Yue, F., Cheng, Y., Breschi, A., Vierstra, J., Wu, W., Ryba, T., et al. (2014). A Comparative Encyclopedia of DNA Elements in the Mouse Genome. Nature 515 (7527), 355–364. doi:10.1038/nature13992

Zeng, Q., Han, Y., Bao, Y., Li, W., Li, X., Shen, X., et al. (2010). 20-HETE Increases NADPH Oxidase-Derived ROS Production and Stimulates the L-type Ca2+ Channel via a PKC-dependent Mechanism in Cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 299 (4), H1109–H1117. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00067.2010

Zhang, J., Su, X., Qi, A., Liu, L., Zhang, L., Zhong, Y., et al. (2021). Metabolomic Profiling of Fatty Acid Biomarkers for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Stroke. Talanta 222, 121679. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121679

Zhang, Y., and Klaassen, C. D. (2013). Hormonal Regulation of Cyp4a Isoforms in Mouse Liver and Kidney. Xenobiotica 43 (12), 1055–1063. doi:10.3109/00498254.2013.797622

Glossary

AA arachidonic acid

ACE angiotensin converting enzyme

COX cyclooxygenase

CYP cytochrome P450

DHA docosahexaenoic acid

DHET dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid

DiHOME dihydroxyoctadecenoic acid

EDPs epoxydocosapentaenoic acid

EEQ epoxyeicosatetreaenoic acid

EET epoxyeicosatrienoic acid

EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor

EPA eicosapentaenoic acid

HDoHE hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid

HEETs hydroxyepoxyeicosatrienoic acids

HEPEs hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid

HETE hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

HPDHA hydroperoxydocosahexaenoic acid

HPEPE hydroperoxy-eicosapentaenoic acid

IL nterleukin

LOX lipoxygenase

LPS ipopolysaccharide

LTA4 eukotriene A4

LTB4 leukotriene B4

LXs Lipoxin

MAPK/ERK the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase

NF-α tumor necrosis factor alpha,

NF-κB nuclear factor-kappa B

PGE3 prostaglandin E3

PGH2 prostaglandin H2

PI3K phosphoinositide 3-Kinases.

PLA2 phospholipase A2

PPAR peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

PUFA polyunsaturated fatty acid

ROS reactive oxygen species

sEH soluble epoxide hydrolaseT

VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

Keywords: cytochrome P450, omega hydroxylase, eicosanoids, inflammation, cardiovascular disease

Citation: Ni K-D and Liu J-Y (2021) The Functions of Cytochrome P450 ω-hydroxylases and the Associated Eicosanoids in Inflammation-Related Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 12:716801. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.716801

Received: 29 May 2021; Accepted: 01 September 2021;

Published: 14 September 2021.

Edited by:

Emanuela Ricciotti, Universfity of Pennsylvania, United StatesReviewed by:

Victor Garcia, New York Medical College, United StatesYogan Khatri, Cayman Chemical Company, United States

John D Imig, Medical College of Wisconsin, United States

Copyright © 2021 Ni and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jun-Yan Liu, anlsaXVAY3FtdS5lZHUuY24=

†ORCID:Jun-Yan Liuorcid.org/0000-0002-3018-0335

Kai-Di Ni

Kai-Di Ni Jun-Yan Liu

Jun-Yan Liu