- 1Department of Clinical Pharmacy, The First Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University and Shandong Provincial Qianfoshan Hospital, Shandong Engineering and Technology Research Center for Pediatric Drug Development, Shandong Medicine and Health Key Laboratory of Clinical Pharmacy, Jinan, China

- 2Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Key Laboratory of Chemical Biology (Ministry of Education), School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 3Department of Pediatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University and Shandong Provincial Qianfoshan Hospital, Shandong Engineering and Technology Research Center for Pediatric Drug Development, Jinan, China

Objective: The elucidation of CYP2D6 developmental pharmacogenetics in children has improved, however, these findings have been largely limited to studies of Caucasian children. Given the clear differences in CYP2D6 pharmacogenetic profiles in people of different ancestries, there remains an unmet need to better understand the developmental pharmacogenetics in populations of different ancestries. We sought to use loratadine as a substrate drug to evaluate the effects of ontogeny and pharmacogenetics on the developmental pattern of CYP2D6 in Chinese pediatric patients.

Methods: Chinese children receiving loratadine treatment were enrolled in the present study. The metabolite-to-parent ratio (M/P ratio), defined as the molar ratio of desloratadine to loratadine of trough concentrations samples at steady-state condition, was used as a surrogate of CYP2D6 activity. Loratadine and desloratadine were determined by LC/MS/MS method. Variants of CYP2D6 were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction for CYP2D6 *4, *10, *41 and long polymerase chain reaction for CYP2D6 *5.

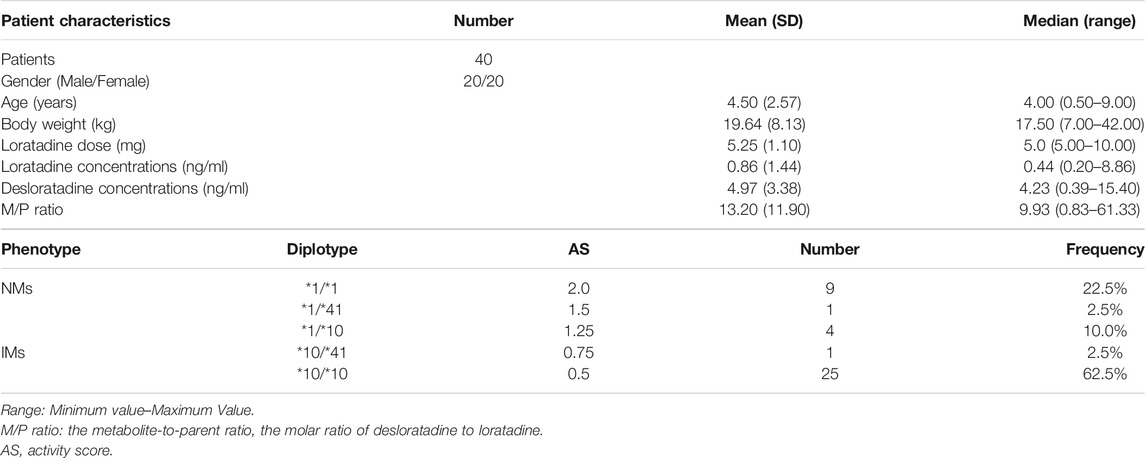

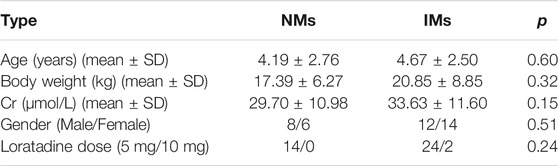

Results: A total of 40 patients were available for final analysis. The mean age was 4.50 (range 0.50–9.00) years and the mean weight was 19.64 (range 7.00–42.00) kg. The M/P ratio was significantly lower in intermediate metabolizers (IMs) compared to normal metabolizers (NMs) (10.18 ± 7.97 vs. 18.80 ± 15.83, p = 0.03). Weight was also found to be significantly associated with M/P ratio (p = 0.03).

Conclusion: The developmental pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6 in Chinese children was evaluated using loratadine as a substrate drug. This study emphasizes the importance of evaluating the developmental pharmacogenetics in populations of different ancestries.

Introduction

Many age-related physiological and biological factors, such as gastric pH, intestinal motility, liver, intestinal enzymes and transporters, can lead to changes in drug disposition during childhood development (Kearns et al., 2003; Hines, 2008). The developmental changes in cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme activity during the growth and development of children has important influences on the differences in age-related drug disposition (de Wildt et al., 2014).

CYP2D6 accounts for about 2% of the total liver CYP content in adults (Shimada et al., 1994), and mediates the metabolism of many drugs, such as analgesics, cardiovascular, antidepressant and antipsychotics (Allegaert et al., 2011). CYP2D6 ontogeny has been published in fetal, pediatric and adult in vitro or in vivo (Ladona et al., 1991; Treluyer et al., 1991; Jacqz-Aigrain et al., 1993; Tateishi et al., 1997; Hu et al., 1998; Kennedy et al., 2004; Allegaert et al., 2005; Blake et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2008; Stevens et al., 2008). However, the interpretation of these data is controversial, previous studies showed that CYP2D6 protein and activity increased in the first month of life, reaching approximately two-thirds of adult levels between 1 month and 5 years of age (Treluyer et al., 1991). Other studies have reported that the levels of CYP2D6 protein were similar between infants who were aged 0–1 compared to individual over 1 year of age (Ladona et al., 1991; Tateishi et al., 1997). Notably, CYP2D6 activity has been detected in children 2 weeks old, consistent with genotype, and remained unchanged at 1 year of age (Blake et al., 2007). Some studies observed that CYP2D6 expression increased sharply in the first year of life considering the maturity level of renal function in the first year (Johnson et al., 2008) and CYP2D6 ontogeny is complete by age of 1 year (Hu et al., 1998; Kennedy et al., 2004; Allegaert et al., 2005). For example, several studies have found that in pediatric populations (age 1–8 years) the CYP2D6 normal metabolizers had already reached adult levels of CYP2D6 enzyme activity (Hu et al., 1998; Kennedy et al., 2004; Allegaert et al., 2005). Further studies are required to explore the age-related developmental pattern of CYP2D6 by ancestry.

In addition to age-related factors, pharmacogenetic polymorphisms further contribute to inter-individual differences in drug response. Pharmacogenetic variants in the CYP2D6 gene can result in increased, decreased, or complete loss of CYP2D6 activity (Allegaert et al., 2005; Allegaert et al., 2008; Stevens et al., 2008). The incidence of specific polymorphisms in CYP2D6 can vary widely in different worldwide ancestries. For example, it has been widely reported that the incidence of CYP2D6*10, which reduces the activity of CYP2D6, is carried by approximately 50% of people with Asian ancestry, but is rare in European populations (Wang et al., 1993; Johansson et al., 1994).

Previous studies on developmental pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6 have been well documented in Caucasian population (Kennedy et al., 2004; Allegaert et al., 2005; Blake et al., 2007), alleles such as CYP2D6*3, CYP2D6*4, and CYP2D6*5 accounts for about 98% of the poor metabolizers (Gaedigk et al., 1999). The elucidation of CYP2D6 developmental pharmacogenetics in these populations has improved. While in Asian population, CYP2D6*3 and *4 are relatively rare, and the high frequency of the CYP2D6*10 allele (Wang et al., 1993; Johansson et al., 1994) may lead to the low CYP2D6 activity in Asian normal metabolizers. Thus, there are still some gaps of knowledge in people with Asian ancestry. Given the clear differences in CYP2D6 pharmacogenetic profiles in people of different ancestries, there remains an unmet need to better understand the developmental pharmacogenetics in populations of different ancestries. We hypothesized that both developmental factors and pharmacogenetics (classify by the CYP2D6 phenotypes) can explain the developmental pattern of CYP2D6 in Chinese children. Therefore, we carried out a developmental pharmacogenetic study of CYP2D6 using loratadine as a substrate drug in Chinese children.

The reasons for choosing loratadine as a substrate drug are as follows:

1) It is often used to treat allergic diseases in Chinese children, such as seasonal allergies and rashes (Clissold et al., 1989).

2) Loratadine is known to be a substrate for CYP2D6 based on previous in vitro studies (Yumibe et al., 1996; Ghosal et al., 2009; Sheludko et al., 2018). CYP2D6 is the enzyme that plays an important role in the pharmacokinetic variability of loratadine in Chinese population. After oral administration, loratadine is absorbed rapidly and undergoes extensive metabolism in the body. One of the main metabolites, desloratadine, is reported to have more pharmacological potencies than loratadine (Geha and Meltzer, 2001; Ramanathan et al., 2007).

3) The significant effects of CYP2D6 polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics of loratadine has been reported in Chinese adults. For example, loratadine exposure was 123.6% higher (p < 0.05) and CL/F decreased by 50.9% (p < 0.01) in CYP2D6 wild type Chinese adults compared to homozygous CYP2D6*10/*10 subjects. Similarly, Loratadine exposure was 75.5% higher (p < 0.05) and CL/F decreased by 35.2% (p < 0.01) in CYP2D6*10 heterozygotes compared to CYP2D6*10/*10 homozygous subjects (Yin et al., 2005).

Methods

Subjects

The study was designed and carried out at Shandong Provincial Qianfoshan Hospital. Patients aged from 6 months to 12 years with allergic disorders such as allergic rhinitis or allergic asthma and underwent routine treatment of loratadine were included in the present study. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committees of the clinical institution (Shandong Provincial Qianfoshan Hospital). Informed-consent forms were obtained from the patients’ parents or guardians before the initiation of the study.

Patients receiving loratadine (10 mg; schering plough, Shanghai, China) as part of routine anti-allergy therapy were eligible to be included in the present study. Patients were excluded if they had co-administrated with known inhibitor of CYP2D6 such as fluoxetine, paroxetine and amiodarone. Loratadine was administered as follows: 10 mg once daily for children

Determination of Loratadine and Its Metabolites

Trough plasma concentrations of loratadine and its main active metabolite desloratadine were determined by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) (Li et al., 2020). After mixed with the internal standard (IS, propranolol) and precipitated with methanol, plasma samples were then separated on a C18 column with a gradient mobile phase consisting of water (containing 0.1% formic acid) and acetonitrile. After centrifuged, 20 µl of the supernatants were injected into the HPLC system. The quantitation of loratadine, desloratadine and IS was performed using MRM mode and the transitions were: 383.1 → 337.1 for loratadine, 311.1 → 259.0 for desloratadine and 260.2 → 116.0 for IS, respectively. The calibration curve ranged from 0.20 to 50 ng/ml for both loratadine and desloratadine. The inter-day and intra-day coefficients of variation (CVs) of controls were both below 9.20%. The accuracy of loratadine and desloratadine were 102.50–109.21% and 101.81–108.83%, respectively. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ, associated inter-day and intra-day CVs) were 0.20 ng/ml for both loratadine and desloratadine.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted with a TIANamp Blood DNA Kit (TianGen Biotech, Beijing, China) from whole blood sample. The single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of CYP2D6*4 (rs3892097), CYP2D6*10 (rs1065852), and CYP2D6*41 (rs28371725) were selected for genotyping, primers and probes were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to identify CYP2D6 alleles on a Fluorescence Quantitative PCR (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States) according to the TaqMan allelic discrimination assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). Long polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods from Hersberger et al. (2000) were employed to detect the CYP2D6∗5 (whole gene deletion).

The consensus CYP2D6 activity score (AS) was used to classify phenotypes according to CPIC and DPWG guidelines (Blake et al., 2007; Gaedigk et al., 2017; Caudle et al., 2020). The patients were divided into two groups NMs (normal metabolizers, 1.25 ≤ AS ≤ 2.25) and IMs (intermediate metabolizers, 0 < AS < 1.25). Patients who did not carry CYP2D6*4, *5, *10, or *41 were assumed to have a CYP2D6 activity score of 2 (CYP2D6*1/*1).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 16.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Inc., NY, United States). The medians and ranges of continuous variables were summarized and linear regression analysis was carried out. Mann-Whitney U test was used to study the effect of the CYP2D6 phenotypes on the M/P ratio (the molar ratio of desloratadine to loratadine). Multiple regression analysis was performed to determine the association of multiple factors such as weight, age and CYP2D6 phenotypes with M/P ratio. Factors that showed to be significant factors of M/P ratio from bivariate analysis (p < 0.05) were selected as candidate covariates in the multivariate test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

Forty-three patients were enrolled in this study. Three of them had loratadine and desloratadine levels below the LLOQ (0.20 ng/ml), these cases were excluded from the study since the data cannot be used to calculate the M/P ratio quantitatively. In final, 40 patients were available for final analysis. The mean (standard deviation) age was 4.50 (2.57, range 0.50–9.00) years and the mean (standard deviation) weight was 19.64 (8.13, range 7.00–42.00) kg. The characteristics of patients and data on CYP2D6 phenotypes are summarized in Table 1. The two groups NMs and IMs are comparable in terms of age, weight, gender, dose, and creatinine clearance rate in Table 2.

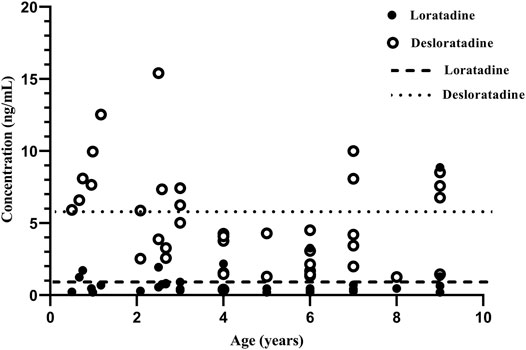

The M/P ratio was significantly associated with CYP2D6 phenotypes. The M/P ratio was significantly lower in intermediate metabolizers (IMs) compared to normal metabolizers (NMs) (10.18 ± 7.97 vs. 18.80 ± 15.83, Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.03) (Figure 1). Weight was also found to be significantly associated with M/P ratio (p = 0.03). There was not a significant association between age and M/P ratio (Figure 2). In final, multiple linear regression analyses revealed distinctive factors included weight and CYP2D6 phenotypes associated with the M/P ratio. These two factors could explain about 19.7% of the interindividual variability in the M/P ratio (R2 = 0.197).

FIGURE 1. Impact of CYP2D6 phenotypes on the M/P ratio of loratadine. The bars are medians, boxes are interquartile range, whiskers represent the min to max. Significant (p = 0.03) difference between NMs and IMs.

FIGURE 2. The relationship between plasma concentration vs. age. The long dotted line is the mean trough plasma concentration of loratadine in steady-state condition in adults. The short dash line is the mean trough plasma concentration of desloratadine in steady-state condition in adults.

Discussion

The developmental pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6 was evaluated for the first time in Chinese children. The impact of CYP2D6 phenotypes on CYP2D6 activity was demonstrated using a substrate drug of loratadine.

Previous studies on pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6 have been well documented in Caucasian population. Several alleles of the CYP2D6 such as CYP2D6*3, CYP2D6*4, CYP2D6*5, and CYP2D6*10 that cause absent or decreased enzyme activity have been reported (Gaedigk et al., 1999). In Caucasian population, CYP2D6*3, CYP2D6*4, and CYP2D6*5 alleles accountes for about 98% of the poor metabolizers (Gaedigk et al., 1999), while in Asian population, CYP2D6*3 and *4 are rarely found, and the frequency of the CYP2D6*5 alleles is about 5% (Wang et al., 1993). Although the frequency of the CYP2D6*2 alleles is high anywhere between 10 and 50% (Gaedigk et al., 2017), CYP2D6*2 is currently considered to be a normal function allele by CPIC and DPWG; however, this function assignment has been challenged and some laboratories report CYP2D6*2 function differently. Function of this allele will be reassessed as additional data become available (Kearns et al., 2003; Hines, 2008). Meanwhile, the CYP2D6*10 allele occurs in approximately 50% of Asian population, but is extremely rare in white population (Wang et al., 1993; Johansson et al., 1994). Therefore it has been postulated that the high frequency of the CYP2D6*10 allele causes the low CYP2D6 activity in Asian normal metabolizers. In this study, the M/P ratio was significantly lower in IMs than those in NMs. These results suggest the CYP2D6 activity is poor in IMs subjects (60.46% subjects were CYP2D6*10/*10 genotypes), which is similar to that reported in adults (Yin et al., 2005). Additionally, similar observations were made in the relationship between the CYP2D6*10 genotype and the pharmacokinetics of haloperidol in Asian subjects (Mihara et al., 1999; Roh et al., 2001). Therefore, our present study suggest that the CYP2D6 polymorphisms with CYP2D6*10/*10 plays an important role in lower the activity of CYP2D6 in Chinese adults and children.

Our results showed no significant association between M/P ratio and age. This may be related to the relatively small sample size. Based on conclusion of most previous research (Kennedy et al., 2004; Allegaert et al., 2005; Blake et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2008; Stevens et al., 2008; de Wildt et al., 2014), the levels of CYP2D6 enzyme activity were similar between children over 1 year of age and adults. For example, in vitro, CYP2D6 enzyme activity is low before birth, but increases to adult levels in the first weeks or months after birth (de Wildt et al., 2014). In vivo, CYP2D6 activity was detectable and consistent with genotype by 2 weeks old, no change was found in the first year after birth (Blake et al., 2007). In pediatric population (range 1.1–8.0 years), CYP2D6 activity was similar with adult level (Kennedy et al., 2004; Allegaert et al., 2005). We compared the trough plasma concentrations of loratadine and desloratadine to adult levels in steady-state condiition (Figure 2). The result is similar to adults (Radwanski et al., 1987). Due to the limited number of patients, there were only four individual aged 6 months to 1 year, and future research should include a larger patient sample population to accurately identify the correlation between age and CYP2D6 pharmacogenetics in Chinese pediatric population.

Our study did not use the “golden” substrate drugs of CYP2D6 (i.e., dextromethorphan and metoprolol) (Frank et al., 2007), as these drugs were rarely used in pediatric routine practice in China. Loratadine was selected in our present study, not only because of its routine use and determinant role of CYP2D6 on its metabolism, but also the ethical reason. Although CYP3A4, CYP2D6, and CYP2C19 are involved in the metabolism of loratadine (Yumibe et al., 1996; Ghosal et al., 2009), the efficiency of loratadine conversion by CYP2D6 was 4.5∼5-fold higher than that of CYP3A4 (Yumibe et al., 1996; Ghosal et al., 2009; Sheludko et al., 2018) and CYP2D6*10 allele accouts for approximately 50% in Asian subjects (Johansson et al., 1994). For CYP3A4, many variant alleles such as CYP3A4*1B, *2, and *3 are absent in Chinese subjects (Walker et al., 1998; Sata et al., 2000; van Schaik et al., 2001). Some Asian-specific alleles such as CYP3A4*4, *5, *18, and *19, have been reported with frequencies of 1–3% (Dai et al., 2001; Hsieh et al., 2001), but the functions of these alleles in vivo are still uncertain (Eiselt et al., 2001). For CYP2C19, the contribution of the formation of the major circulating metabolite desloratadine was minor (Ghosal et al., 2009). Based on current information, the clinical importance of CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms are not likely for the majority of Chinese population. As the loratadine followed a one-compartment elimination, the trough concentrations could be a reliable surrogate of drug exposure and elimination (Yin et al., 2005). Given the unmet need of understanding developmental pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6 in inter-ancestry population, an adaptive substrate drug should be considered in pediatric pharmacology study (Zhao et al., 2018).

Our study collected trough plasma samples to determine the metabolic ratio of loratadine, because the distribution of drug in plasma, tissues and urine was in equilibrium at multiple-dose steady-state. Studies have shown that the effect of age and CYP2D6 activity scores on plasma M/P ratio interindividual variability is similar to that of 24 h urinary M/P ratio (Allegaert et al., 2008). Besides, studies documented that the sensitivity of CYP2D6 activity in vivo was different based on urine metabolic ratio’s to urine pH (Stamer et al., 2003). As the volume and the number of samples that can be taken at once are limited in children, we did not choose the AUC approach in the study. Based on these reasons, we selected the molar ratio of desloratadine to loratadine of trough concentrations samples as a surrogate of CYP2D6 activity.

Our research had some limitations. Firstly, since the primary objective of this study was to describe the developmental pattern of CYP2D6, clinical outcomes were not evaluated. Developmental pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics need to be evaluated in the following studies. Secondly, CYP2D6 gene duplication such as CYP2D6*1xN, *10xN, and *36xN had the lower frequency in Chinese people and these structural variants were not analyzed (Gaedigk et al., 2017). This is a limitation since 10xN and *36xN with decreased function may have some impact in those patients that carry it (Del Tredici et al., 2018). Meanwhile, due to the limited number of patients, we did not found CYP2D6*4, CYP2D6*5 in this population, and future research should include a larger patient sample population to accurately identify the correlation between CYP2D6*5, CYP2D6*41, CYP2D6*10, and gene duplication polymorphisms and CYP2D6 pharmacogenetics in Chinese pediatric population. Thirdly, the unexplained variability in our study is still large, indicating that other covariates contribute to the pharmacokinetics of loratadine. These missing covariates also require further evaluation. In conclusion, the developmental pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6 in Chinese pediatric patients was evaluated using loratadine as a substrate drug. CYP2D6 phenotypes showed independently significant impact on M/P ratio. Our results emphasize the importance of evaluating the developmental pharmacogenetics in populations of different ancestries.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethical committees of the clinical institution (Shandong Provincial Qianfoshan Hospital). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

QL, Y-EW, and KW retrieved data, carried out the initial analyses and drafted the initial manuscript. H-YS, YuZ, YiZ, G-XH, Y-LY, L-QS, and W-QW collected samples, recorded patient information. X-MY and WZ conceptualized, designed and initiated the study. All the authors contributed to write the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding

This study was supported by Young Taishan Scholars Program and Qilu Young Scholars Program of Shandong University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this paper was presented at the European Society for Developmental Perinatal and Paediatric Pharmacology Congress as a poster presentation with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in “Poster Abstracts” in Archives of Disease in Childhood.

References

Allegaert, K., Anderson, B. J., Verbesselt, R., Debeer, A., de Hoon, J., Devlieger, H., et al. (2005). Tramadol Disposition in the Very Young: an Attempt to Assess In Vivo Cytochrome P -450 2D6 Activity. Br. J. Anaesth. 95 (2), 231–239. Epub 2005/06/14. doi:10.1093/bja/aei170 PubMed PMID: 15951326

Allegaert, K., Rochette, A., and Veyckemans, F. (2011). Developmental Pharmacology of Tramadol during Infancy: Ontogeny, Pharmacogenetics and Elimination Clearance. Paediatr. Anaesth. 21 (3), 266–273. Epub 2010/08/21. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03389.x PubMed PMID: 20723094

Allegaert, K., van Schaik, R. H. N., Vermeersch, S., Verbesselt, R., Cossey, V., Vanhole, C., et al. (2008). Postmenstrual Age and CYP2D6 Polymorphisms Determine Tramadol O-Demethylation in Critically Ill Neonates and Infants. Pediatr. Res. 63 (6), 674–679. Epub 2008/03/05. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e31816ff712 PubMed PMID: 18317231

Blake, M. J., Gaedigk, A., Pearce, R. E., Bomgaars, L. R., Christensen, M. L., Stowe, C., et al. (2007). Ontogeny of Dextromethorphan O- and N-Demethylation in the First Year of Life. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 81 (4), 510–516. Epub 2007/02/16. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100101 PubMed PMID: 17301735

Caudle, K. E., Sangkuhl, K., Whirl‐Carrillo, M., Swen, J. J., Haidar, C. E., Klein, T. E., et al. (2020). Standardizing CYP 2D6 Genotype to Phenotype Translation: Consensus Recommendations from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group. Clin. Transl. Sci. 13 (1), 116–124. Epub 2019/10/28. doi:10.1111/cts.12692 PubMed PMID: 31647186; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6951851

Clissold, S. P., Sorkin, E. M., and Goa, K. L. (1989). Loratadine. Drugs 37 (1), 42–57. Epub 1989/01/01. doi:10.2165/00003495-198937010-00003 PubMed PMID: 2523301

Dai, D., Tang, J., Rose, R., Hodgson, E., Bienstock, R. J., Mohrenweiser, H. W., et al. (2001). Identification of Variants of CYP3A4 and Characterization of Their Abilities to Metabolize Testosterone and Chlorpyrifos. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 299 (3), 825–831. PubMed PMID: 11714865

de Wildt, S. N., Tibboel, D., and Leeder, J. S. (2014). Drug Metabolism for the Paediatrician. Arch. Dis. Child. 99 (12), 1137–1142. Epub 2014/09/05. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-305212 PubMed PMID: 25187498

Del Tredici, A. L., Malhotra, A., Dedek, M., Espin, F., Roach, D., Zhu, G.-d., et al. (2018). Frequency of CYP2D6 Alleles Including Structural Variants in the United States. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 305. Epub 2018/04/21. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00305 PubMed PMID: 29674966; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5895772

Eiselt, R., Domanski, T., Zibat, A., Mueller, R., Presecan-Siedel, E., Hustert, E., et al. (2001). Identification and Functional Characterization of Eight CYP3A4 Protein Variants. Pharmacogenetics 11 (5), 447–458. PubMed PMID: 11470997. doi:10.1097/00008571-200107000-00008

Frank, D., Jaehde, U., and Fuhr, U. (2007). Evaluation of Probe Drugs and Pharmacokinetic Metrics for CYP2D6 Phenotyping. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63 (4), 321–333. Epub 2007/02/03. doi:10.1007/s00228-006-0250-8 PubMed PMID: 17273835

Gaedigk, A., Gotschall, R. R., Forbes, N. a. S., Simon, S. D., Kearns, G. L., and Leeder, J. S. (1999). Optimization of Cytochrome P4502D6 (CYP2D6) Phenotype Assignment Using a Genotyping Algorithm Based on Allele Frequency Data. Pharmacogenetics 9 (6), 669–682. Epub 2000/01/14. doi:10.1097/01213011-199912000-00002 PubMed PMID: 10634130

Gaedigk, A., Sangkuhl, K., Whirl-Carrillo, M., Klein, T., and Leeder, J. S. (2017). Prediction of CYP2D6 Phenotype from Genotype across World Populations. Genet. Med. 19 (1), 69–76. Epub 2016/07/09. doi:10.1038/gim.2016.80 PubMed PMID: 27388693; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5292679

Geha, R. S., and Meltzer, E. O. (2001). Desloratadine: A New, Nonsedating, Oral Antihistamine. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 107 (4), 751–762. Epub 2001/04/11. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.114239 PubMed PMID: 11295678

Ghosal, A., Gupta, S., Ramanathan, R., Yuan, Y., Lu, X., Su, A., et al. (2009). Metabolism of Loratadine and Further Characterization of its In Vitro Metabolites. Dml 3 (3), 162–170. Epub 2009/08/26. doi:10.2174/187231209789352067 PubMed PMID: 19702548

Hersberger, M., Marti-Jaun, J., Rentsch, K., and Hänseler, E. (2000). Rapid Detection of the CYP2D6*3, CYP2D6*4, and CYP2D6*6 Alleles by Tetra-Primer PCR and of the CYP2D6*5 Allele by Multiplex Long PCR. Clin. Chem. 46 (8 Pt 1), 1072–1077. PubMed PMID: 10926885. doi:10.1093/clinchem/46.8.1072

Hines, R. N. (2008). The Ontogeny of Drug Metabolism Enzymes and Implications for Adverse Drug Events. Pharmacol. Ther. 118 (2), 250–267. Epub 2008/04/15. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.02.005 PubMed PMID: 18406467

Hsieh, K. P., Lin, Y. Y., Cheng, C. L., Lai, M. L., Lin, M. S., Siest, J. P., et al. (2001). Novel Mutations of CYP3A4 in Chinese. Drug Metab. Dispos. 29 (3), 268–273. PubMed PMID: 11181494

Hu, O. Y., Tang, H. S., Lane, H. Y., Chang, W. H., and Hu, T. M. (1998). Novel Single-point Plasma or Saliva Dextromethorphan Method for Determining CYP2D6 Activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 285 (3), 955–960. Epub 1998/06/17. PubMed PMID: 9618394

Jacqz-Aigrain, E., Funck-Brentano, C., and Cresteil, T. (1993). CYP2D6- and CYP3A-dependent Metabolism of Dextromethorphan in Humans. Pharmacogenetics 3 (4), 197–204. Epub 1993/08/01. doi:10.1097/00008571-199308000-00004 PubMed PMID: 8220439

Johansson, I., Oscarson, M., Yue, Q. Y., Bertilsson, L., Sjöqvist, F., and Ingelman-Sundberg, M. (1994). Genetic Analysis of the Chinese Cytochrome P4502D Locus: Characterization of Variant CYP2D6 Genes Present in Subjects with Diminished Capacity for Debrisoquine Hydroxylation. Mol. Pharmacol. 46 (3), 452–459. Epub 1994/09/01. PubMed PMID: 7935325

Johnson, T., Tucker, G., and Rostami-Hodjegan, A. (2008). Development of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 in the First Year of Life. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 83 (5), 670–671. Epub 2007/11/29. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100327 PubMed PMID: 18043691

Kearns, G. L., Abdel-Rahman, S. M., Alander, S. W., Blowey, D. L., Leeder, J. S., and Kauffman, R. E. (2003). Developmental Pharmacology - Drug Disposition, Action, and Therapy in Infants and Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 349 (12), 1157–1167. Epub 2003/09/19. doi:10.1056/NEJMra035092 PubMed PMID: 13679531

Kennedy, M. J., Abdel-Rahman, S. M., Kashuba, A. D. M., and Leeder, J. S. (2004). Comparison of Various Urine Collection Intervals for Caffeine and Dextromethorphan Phenotyping in Children. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 44 (7), 708–714. Epub 2004/06/17. doi:10.1177/0091270004266624 PubMed PMID: 15199075

Ladona, M., Lindstrom, B., Thyr, C., Dun-Ren, P., and Rane, A. (1991). Differential Foetal Development of the O- and N-Demethylation of Codeine and Dextromethorphan in Man. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 32 (3), 295–302. Epub 1991/09/01. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03902.x PubMed PMID: 1838002; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1368521

Li, Q., Shi, H., Wang, K., Kan, M., Zheng, Y., Hao, G., et al. (2020). Determination of Loratadine and its Active Metabolite in Plasma by Lc/Ms/Ms: An Adapted Method for Children. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 16 (7), 1–6. doi:10.2174/1573412915666190416121233

Mihara, K., Suzuki, A., Kondo, T., Yasui, N., Furukori, H., Nagashima, U., et al. (1999). Effects of the Allele on the Steady-State Plasma Concentrations of Haloperidol and Reduced Haloperidol in Japanese Patients with Schizophrenia. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 65 (3), 291–294. PubMed PMID: 10096261. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70108-6

Radwanski, E., Hilbert, J., Symchowicz, S., and Zampaglione, N. (1987). Loratadine: Multiple-Dose Pharmacokinetics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 27 (7), 530–533. Epub 1987/07/01. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1987.tb03061.x PubMed PMID: 2958516

Ramanathan, R., Reyderman, L., Kulmatycki, K., Su, A.-D., Alvarez, N., Chowdhury, S. K., et al. (2007). Disposition of Loratadine in Healthy Volunteers. Xenobiotica 37 (7), 753–769. Epub 2007/07/11. doi:10.1080/00498250701463317 PubMed PMID: 17620221

Roh, H.-K., Chung, J.-Y., Oh, D.-Y., Park, C.-S., Svensson, J.-O., Dahl, M.-L., et al. (2001). Plasma Concentrations of Haloperidol Are Related to CYP2D6 Genotype at Low, but Not High Doses of Haloperidol in Korean Schizophrenic Patients. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52 (3), 265–271. Epub 2001/09/19. doi:10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01437.x PubMed PMID: 11560558; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2014539

Sata, F., Sapone, A., Elizondo, G., Stocker, P., Miller, V. P., Zheng, W., et al. (2000). CYP3A4 Allelic Variants with Amino Acid Substitutions in Exons 7 and 12: Evidence for an Allelic Variant with Altered Catalytic Activity. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 67 (1), 48–56. PubMed PMID: 10668853. doi:10.1067/mcp.2000.104391

Sheludko, Y. V., Gerasymenko, I. M., and Warzecha, H. (2018). Transient Expression of Human Cytochrome P450s 2D6 and 3A4 in Nicotiana Benthamiana Provides a Possibility for Rapid Substrate Testing and Production of Novel Compounds. Biotechnol. J. 13 (11), 1700696. Epub 2018/04/11. doi:10.1002/biot.201700696 PubMed PMID: 29637719

Shimada, T., Yamazaki, H., Mimura, M., Inui, Y., and Guengerich, F. P. (1994). Interindividual Variations in Human Liver Cytochrome P-450 Enzymes Involved in the Oxidation of Drugs, Carcinogens and Toxic Chemicals: Studies with Liver Microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucasians. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 270 (1), 414–423. Epub 1994/07/01. PubMed PMID: 8035341

Stamer, U. M., Lehnen, K., Hothker, F., Bayerer, B., Wolf, S., Hoeft, A., et al. (2003). Impact of CYP2D6 Genotype on Postoperative Tramadol Analgesia. Pain 105 (1-2), 231–238. PubMed PMID: 14499440. doi:10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00212-4

Stevens, J. C., Marsh, S. A., Zaya, M. J., Regina, K. J., Divakaran, K., Le, M., et al. (2008). Developmental Changes in Human Liver CYP2D6 Expression. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36 (8), 1587–1593. Epub 2008/05/14. doi:10.1124/dmd.108.021873 PubMed PMID: 18474679

Tateishi, T., Nakura, H., Asoh, M., Watanabe, M., Tanaka, M., Kumai, T., et al. (1997). A Comparison of Hepatic Cytochrome P450 Protein Expression between Infancy and Postinfancy. Life Sci. 61 (26), 2567–2574. Epub 1997/01/01. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01011-4 PubMed PMID: 9416779

Treluyer, J.-M., Jacqz-Aigrain, E., Alvarez, F., and Cresteil, T. (1991). Expression of CYP2D6 in Developing Human Liver. Eur. J. Biochem. 202 (2), 583–588. Epub 1991/12/05. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16411.x PubMed PMID: 1722149

van Schaik, R. H. N., de Wildt, S. N., Brosens, R., van Fessem, M., van den Anker, J. N., and Lindemans, J. (2001). The CYP3A4*3 Allele: Is it Really Rare? Clin. Chem. 47 (6), 1104–1106. PubMed PMID: 11375299. doi:10.1093/clinchem/47.6.1104

Vlase, L., Imre, S., Muntean, D., and Leucuta, S. E. (2007). Determination of Loratadine and its Active Metabolite in Human Plasma by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry Detection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 44 (3), 652–657. PubMed PMID: 16962733. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2006.08.013

Walker, A. H., Jaffe, J. M., Gunasegaram, S., Cummings, S. A., Huang, C. S., Chern, H. D., et al. (1998). Characterization of an Allelic Variant in the Nifedipine-specific Element of CYP3A4: Ethnic Distribution and Implications for Prostate Cancer Risk. Mutations in Brief No. 191. Online. Hum. Mutat. 12 (4), 289. PubMed PMID: 10660343

Wang, S.-L., Huang, J.-D., Lai, M.-D., Liu, B.-H., and Lai, M.-L. (1993). Molecular Basis of Genetic Variation in Debrisoquin Hydroxylation in Chinese Subjects: Polymorphism in RFLP and DNA Sequence of CYP2D6. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 53 (4), 410–418. Epub 1993/04/01. doi:10.1038/clpt.1993.44 PubMed PMID: 8097442

Yin, O. Q. P., Shi, X. J., Tomlinson, B., and Chow, M. S. S. (2005). Effect Ofcyp2D6*10Allele on the Pharmacokinetics of Loratadine in Chinese Subjects. Drug Metab. Dispos. 33 (9), 1283–1287. PubMed PMID: 15932952. doi:10.1124/dmd.105.005025

Yumibe, N., Huie, K., Chen, K.-J., Snow, M., Clement, R. P., and Cayen, M. N. (1996). Identification of Human Liver Cytochrome P450 Enzymes that Metabolize the Nonsedating Antihistamine Loratadine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 51 (2), 165–172. Epub 1996/01/26. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(95)02169-8 PubMed PMID: 8615885

Zhao, W., Leroux, S., Biran, V., and Jacqz-Aigrain, E. (2018). Developmental Pharmacogenetics of CYP2C19 in Neonates and Young Infants: Omeprazole as a Probe Drug. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 84 (5), 997–1005. Epub 2018/01/30. doi:10.1111/bcp.13526 PubMed PMID: 29377228; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5903239

Keywords: children, plasma, ontogeny, pharmacogenetics, CYP2D6

Citation: Li Q, Wu Y-E, Wang K, Shi H-Y, Zhou Y, Zheng Y, Hao G-X, Yang Y-L, Su L-Q, Wang W-Q, Yang X-M and Zhao W (2021) Developmental Pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6 in Chinese Children: Loratadine as a Substrate Drug. Front. Pharmacol. 12:657287. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.657287

Received: 22 January 2021; Accepted: 20 May 2021;

Published: 06 July 2021.

Edited by:

Yvonne Lin, University of Washington, United StatesReviewed by:

Jacob Tyler Brown, University of Minnesota, United StatesColin Ross, University of British Columbia, Canada

Copyright © 2021 Li, Wu, Wang, Shi, Zhou, Zheng, Hao, Yang, Su, Wang, Yang and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xin-Mei Yang, eWFuZ3hpbm0xOTg2QDEyNi5jb20=; Wei Zhao, emhhbzR3ZWkyQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Qian Li1†

Qian Li1† Hai-Yan Shi

Hai-Yan Shi Wei Zhao

Wei Zhao