- 1Saint-Petersburg Institute of Pharmacy, Kuzmolovsky, Russia

- 2All Russian Research Institute Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (VILAR), Moscow, Russia

- 3Research Cluster Biodiversity and Medicines, Centre for Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy, UCL School of Pharmacy, University of London, London, United Kingdom

Historically Russia can be regarded as a “herbophilious” society. For centuries the multinational population of Russia has used plants in daily diet and for self-medication. The specificity of dietary uptake of medicinal plants (especially those in the unique and highly developed Russian herbal medical tradition) has remained mostly unknown in other regions. Based on 11th edition of the State Pharmacopoeia of the USSR, we selected 70 wild plant species which have been used in food by local Russian populations. Empirical searches were conducted via the Russian-wide applied online database E-library.ru, library catalogs of public libraries in St-Petersburg, the databases Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and search engine Google Scholar. The large majority of species included in Russian Pharmacopoeia are used as food by local population, however, aerial parts are more widely used for food. In this review, we summarize data on medicinal species published in Russia and other countries that are included in the Russian Pharmacopoeia and have being used in food for a long time. Consequently, the Russian Pharmacopoeia is an important source of information on plant species used traditionally at the interface of food and medicine. At the same time, there are the so-called “functional foods”, which denotes foods that not only serves to provide nutrition but also can be a source for prevention and cure of various diseases. This review highlights the potential of wild species of Russia monographed in its pharmacopeia for further developing new functional foods and—through the lens of their incorporation into the pharmacopeia—showcases the species' importance in Russia.

Introduction

Until today over 7000 species have been recorded to be edible (Lim, 2012) and for many of these specific health benefits have been claimed, with, however, generally only limited pharmacological evidence for such claims. Only a small share of these is used on a large, extensive scale. Wild and cultivated food plants may have medicinal, nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and health benefits. Plants are excellent sources of active phytochemicals with importance in the prevention of different diseases. Herbal medicinal products are going recognition for the treatment and prophylaxis of different diseases. Direct nutritional benefits of such plants are often known only to a limited extend. Herbal infusions will add small quantities of essential micronutrients and vitamins to the daily intake. For sick or malnourished individuals this may contribute to restoring the balance between nutrients and thereby improve or sustain health (Lim, 2012).

Blurring of the food and medicine interface is a common theme across multiple contexts and cultures (Heinrich, 2016). The association between food and disease is widely recognized as the bedrock of preventive nutrition. Throughout the ages, and at least since the proclamation “let food be your medicine, let medicine be your food” which has been attributed to Hippocrates' (ca. 480–377 BC), physicians recognized the impact of food on human health. The question of the continuum between food and medicine is of great interest to (ethno-)pharmacologists (Etkin and Ross, 1982; Leonti, 2012; Valussi and Scire, 2012; Jennings et al., 2014; Alarcón et al., 2015).

In many countries medicinal plants are widely used as dietary supplements, in daily foods and as functional foods, with the aim of promoting health. In Eastern cultures food and medicine are seen to come from the same source. Their use is based on the same fundamental theories, and they are equally important in maintaining and improving health and for preventing and curing diseases, as well as facilitating rehabilitation. In China, Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia, medicinal plants are widely used both daily foods (cereals, vegetables, and fruits) and functional foods, for replacement and medical purposes (Shi et al., 2011). The last few decades has seen the introduction to Europe of a wide range of species used in other continents, including from South Africa e.g. rooibos (Aspalathus linearis (Burm.f.) R.Dahlgren) and to a lesser extent honey bush tea (Cyclopia sp.) or Hoodia gordonii (Masson) Sweet ex Decne. to regulate the appetite. Also some exotic fruits, such as acerola (Malpighia glabra L.) from South America, rich in vitamin C are now marketed as food supplements (Franz et al., 2011).

In the early history of Western biomedicine, diet figured prominently in the prevention of diseases and therapeutics. The history of biomedicine customarily is traced to Greece and the Hyppocratic Corpus, some 60 medical texts dating to the fifth to fourth centuries BCE. Diet regulation was the most prominent element in all the Hippocratic texts (Etkin, 2006). Due to its location between East and West Russian tradition of medicine and diet has accumulated and adopted approaches that originated in Europe and Asia. The Greek influence on Russian medicine is of particular relevance in this context (Shikov et al., 2014a).

Russia in the past and present can be regarded as a “herbophilious” society. The term “herbophilia” was used by Łuczaj (2008) for such cultures, in which medicinal and food plant species are often used and highly prized. Approximately 58% of the Russian population was reported to use phytopharmaceuticals as a form of treatment (Shikov et al., 2011) including wild plants. Plants are an integral part of Russian everyday life. A large number of species of green vegetables are used in agricultural communities, particularly those in which food shortages are frequent. Due to the harsh climatic conditions coupled with poor crop harvests Russian peasants were educated on how to survive by relying on wild plants (Kovaleva, 1972).

Wild food plants became highest priority in the USSR during the Second World War most notably during the siege of Leningrad (1941–1944). In 1942 a special manual about most important wild food plants of the Leningrad region was published and distributed to the army and civilians. The scientists from V.L. Komarov Botanical Institute described thirty seven common herbs and two edible lichens, their nutritional and functional properties, specificity of harvesting, and food processing (Tikhomirov, 1942).

As a result of socio-economic changes after the Second World War, the active role of wild plants gradually diminished in regular diet. However, some species are still gathered and made into food products by small companies. Wild berry harvesting is very popular especial among of rural populations. The practice of preparing jam, compotes, and home made liqueurs from wild berries has been passed down by housewives from generation to generation (Grigorieva, 2008).

A wide choice of herbal medicines or botanicals has provided increasing opportunities for both the development and marketing of herbal food products, dietary supplements, and functional foods.

Wild species were selected for food application by humans not only because of their pleasant taste and aroma, but some pharmacological effects were considered as well (Gammerman and Grom, 1976). Herbal medicine products have become popular over the past decade and they are widely used for the treatment and prevention of various diseases. However, safety and efficacy of herbal medicine should be confirmed. Utilization of knowledge about positive pharmacological effects of edible plants included in in a pharmacopeia is one of probably safe and effective way for development of functional products with new beneficial effects (Kunakova et al., 2011).

Searching for new food supplements is essential. Systematic explorations of pharmacopoeial plants are one particularly relevant opportunity in Eastern Europe, especially in those areas which, for historical reasons, remain relatively isolated. The use and importance of Russian medicinal plants remains largely unknown in the West. The aim of this review is to summarize data about species that are referenced in the Russian Pharmacopoeia and about their health food value with a primary focus on literature published in Russian.

Overview of Species from the Russian Pharmacopoeia Used as Foods

For centuries the multinational population of Russia has used plants in daily diet and for self-medication. The beneficial effects of plants were carefully collected by “knowledgeable experts” (znahar = “знахарь”in Russian) and recorded in chronicles and manuscripts. In 1778, Russia was among the first countries to implement a national pharmacopeia: The Pharmacopoeia Rossica in St. Petersburg. This work contains 770 monographs, of which 316 texts are on herbal medicinal preparations (Shikov et al., 2014a).

Since 1990, the Russian Federation has followed the State Pharmacopoeia of the USSR (1990) 11th edition. This Pharmacopeia includes 83 individual monographs for plants describing 119 species. There are 26 Rosaceae, 12 Compositae (syn. Asteraceae), eight Lamiaceae, six Polygonaceae, four each of the Apiaceae, Betulaceae, Ericaceae, and Malvaceae species, three representatives each of the Solanaceae, Leguminosae (Fabaceae), and Plantaginaceae, two species each of the Adoxaceae (Caprifoliaceae), Asparagaceae (Liliaceae, s.l), Araliaceae Fagaceae, Gentianaceae, Hypericaceae, Laminariaceae, Pinaceae, Rhamnaceae, and Violaceae, and one member each of the Acoraceae (Araceae), Brassicaceae, Caprifoliaceae (Valerianaceae), Crassulaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Cupressaceae, Equisetaceae, Hymenochaetaceae, Linaceae, Menyanthaceae, Myrtaceae, Papaveraceae, poaceae, Polemoniaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rubiaceae, Saxifragaceae, Schisandraceae, and Urticaceae, respectively.

In the most of monographs, just one species is described as a source of plant material. However, 13 species are approved for Fructus rosae, 11 species are approved for Fructus crataegi, two species are approved for Herba hyperici, Fructus alni, Herba violae etc. Different parts are described for Viburnum opulus L. (Cortex viburni as diuretic and Fructus viburni as diaphoretic and anti-inflammatory) and Crataegus (Flos crataegi−13 species and Fructus crataegi−11 species for cardiovascular problems).

The large majority of species included in the Russian Pharmacopoeia (98 out of 119) are known to have been used as food by local population in Russia. For a majority of species, the part of plant used in food and as a medicine is the same. For example, the aerial parts of Origanum vulgare L., Thymus serpyllum L., Leonurus cardiaca L., are used as a medicine and as a food. Acorns and leaves of Quercus robur L. and Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl. are used in food, while oak bark is used as a medicine. Fruits and bark of Viburnum opulus L. are used as medicine, with only the fruits being edible. Roots and rhizomes of Acorus calamus L., Taraxacum campylodes G.E.Haglund (syn. Taraxacum officinale L.), and Aralia elata (Miq.) Seem. are used as a medicine while young sprouts, leaves, flowers and fruits are used in food. The aerial parts of Equisetum arvense L. are used in medicine, while its cone-bearing shoots and black nodules attached to the roots are eaten raw in spring.

In general, considering all 98 edible plant species in the Russian Pharmacopoeia 11th edition, a higher number of plant parts are used in nutrition as compared to medicine. In the context of this article, the term “wild medicinal plants” referrings mainly to non-cultivated species. Twenty one plants including Calendula officinalis L., Eucalyptus viminalis Labill., Pimpinella anisum L., Zea mays L., and some others do not occur in Russia outside of cultivation and are excluded from this review. All poisonous and toxic species are not used in food as such as the species belonging to the Solanaceae (Atropa belladonna L., Datura stramonium L., Hyoscyamus niger L.), Asparagaceae (Convallaria majalis L., Convallaria keiskei Miq.), Rhamnaceae (Frangula alnus Mill., Rhamnus cathartica L.), Ranunculaceae (Adonis vernalis L.), Papaveraceae (Chelidonium majus L.) and some species from the newly circumscribed Plantaginaceae (Digitalis purpurea L., Digitalis grandiflora Mill.).

Consumer and marketing studies invariably showed that taste, as opposed to perceived nutrition or health value is the key influence on food selection (Drewnowski and Gomez-Carneros, 2000). Sensitized to the astringent taste of tannins or some bitter poisons, humans reject foods that are perceived to be excessively astringent or bitter. Polemonium caeruleum L. (Polemoniaceae), Rubia tinctorum L. (Rubiaceae), Alnus incana (L.) Moench and Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn. (Betulaceae) are not considered to be edible due to their taste, as well as Gnaphalium uliginosum L. and Bidens tripartita L. (Asteraceae) which, however, are without any strong taste.

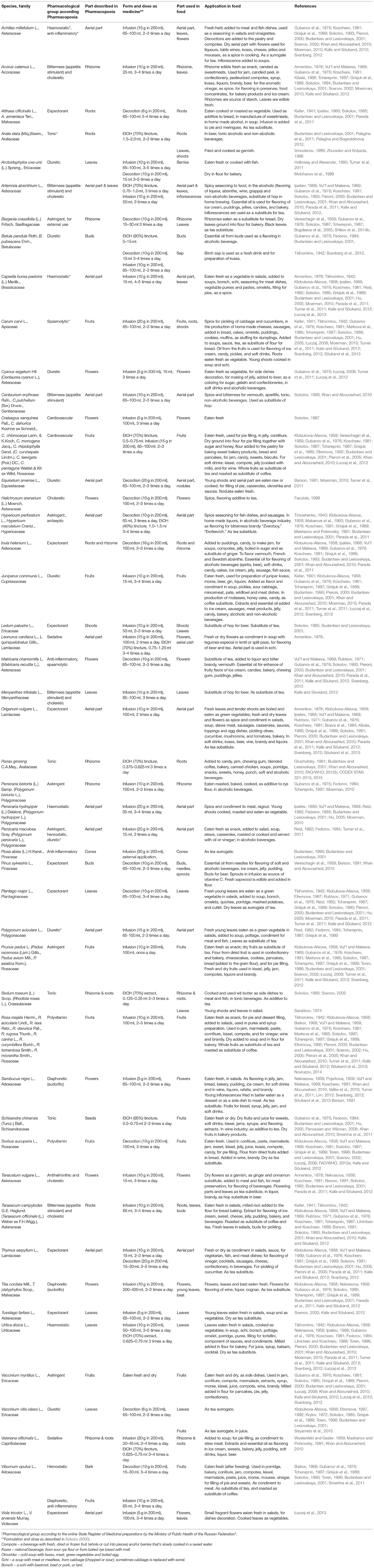

Edible wild species included in the Russian Pharmacopoeia have a wide range of uses: expectorant, diuretic, astringent, haemostatic, bitterness and choleretic, anti-inflammatory, diaphoretic, tonic, sedative, spasmolytic, polyvitamin, cardiovascular, and antihelminthic (Table 1).

Plants with expectorant properties alleviate the symptoms of patients in certain stages of bronchitis or tracheitis. Beneficial expectorant effects are mentioned for nine edible wild species. Certain edible species (nine species) are natural diuretics. Astringent species (eight species) provide not only specific taste for wine, tea, and other beverages due to high tannins content, but are effective in stopping the flow of blood or other secretions, and resolve diarrhea. Bitterness and choleretic herbs (seven species) are useful for development of functional foods with digestion-enhancing properties. The haemostatic effects of herbs (six species) are often due to mechanisms such as tannin astringency rather than enhancement of coagulation, although there are a few haemostatic herbs have been shown to reduce clotting times and have inhibitory effects on the Platelet Aggregation Factor. Four species included in the Russian Pharmacopoeia are used for their anti-inflammatory action. In the last decades, so-called natural anti-inflammatory diets have gained popularity (Sears, 2015). Diaphoretic herbs (four species) induce involuntary perspiration and thus reduce fever, promote circulation, relieve muscle tension, aching joints, and inflammatory skin conditions. These herbs are used as well to relieve diarrhea, dysentery, kidney nephritis, liver, urinary, and gall bladder. Tonic herbs (four species) as supplement to food are consumed throughout the world on a daily basis to promote radiant health and are included in many beverages. Motherwort and valerian provide mild sedative effects. The species with spasmolytic effects (two species) are noticeable as components of diets for treatment of gastro-intestinal ailments.

Hawthorn berries and flowers are useful for the creation of functional products with cardiovascular properties. Antihelmintic properties of tansy are complementary to its choleretic effects. The well documented anxiolytic effect of L. cardiaca L. may lead to the development of antistress functional food products. Increased access to information through systematic evaluation of medicinal plants and its nutritional properties will support the generation of ideas for functional food with new value added properties.

Underground parts like roots, shoots and leafy greens, berries and other fleshy fruits, seeds, and other species commonly yield wild-harvested foods, a practice which is based on specialized cultural knowledge of their harvesting, preparation, cooking and other forms of processing.

Edible Wild Plants–Approaches and Methods for Assessing Uses and Evidence

Based on the State Pharmacopoeia of the USSR, we selected seventy wild species that are used as food in Russia and systematically searched the scientific literature (published between 1878-2016) for data using the Russia-wide applied online database E-library.ru, library catalogs of public libraries in St-Petersburg, the databases Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and search engine Google Scholar. The primary search criterion was a food application of medicinal plants.

Edible wild plants include food categories familiar to everyone: green vegetables and potherbs, wild berries and fruits, beverages, tea and coffee substitutes, seasonings and spices, sweets, bread surrogates, plants used for preserves. Family names of the species are based on www.theplantlist.org database with the names in the Russian Pharmacopoeia given in brackets (Table 1). Also included are the applications in food.

Green Vegetables and Potherbs

This category includes the majority of examined plants. Especially in the spring or at the beginning of their growing season, many wild species produce tender, edible leaves and shoots, and flowers at the beginning of flowering. Some, like shepherd's-purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik.), cornflower (Cyanus segetum Hill., syn. Centaurea cyanus L.), and broadleaf plantain (Plantago major L.) can be eaten raw, after being peeled from soil (Sokolov, 1985, 1990; Tcherepnin, 1987; Grisjuk et al., 1989; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001; Turner et al., 2011), whereas others, like stinging nettles (Urtica dioica L.) must be steamed or cooked in some way (Litvintsev and Koscheev, 1988; Fedorov, 1984; Toren, 1996). These plants are used for salads, added to soups, borsch, omelets, cooked and used as a garnish.

Many edible greens emerging right after the melting of snow are particularly important for their vitamin C content in the spring and traditionally have been used to prevent and alleviate scurvy. In particularly, soup and borsch with nettles are popular not only among rural but also many urban people (Gubanov et al., 1976; Koscheev, 1981; Tcherepnin, 1987; Litvintsev and Koscheev, 1988).

Tonic properties of shoots of aralia (Aralia elata (Miq.)Seem.) were recognized by Ussuri aborigines (Far East). Young shots no more than 20 cm are cooked and served as garnish (Izmodenov, 1989).

Wild Berries and Fruits

Presumably, wild berries and fruits are the most favored group of edible medicinal plants in Russia, and today probably used most frequently. The wild fruits most commonly collected in Russia include bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.), hawthorn (Crataegus spp.), and rose hips (Rosa spp.) (Gubanov et al., 1976; Koscheev, 1981; Sokolov, 1987; Tcherepnin, 1987; Grisjuk et al., 1989; Efremova, 1992; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001; Soenov, 2002; Łuczaj et al., 2012; Sõukand et al., 2013; Novruzov, 2014). All of them are consumed fresh, but some are also preserved for the winter by making jams, marmalade or pasteurized compotes (Turova and Sapozhnikova, 1989). Furthermore, they are used to make beverages. Some berries are popular among all groups of the population (like bilberry), other species that once were used as a valuable food source in some regions of Russia have seen that food use diminished because of the bitter or astringent taste as such as guelder rose (Viburnum opulus L.), bird cherry (Prunus padus L.), and rowan (Sorbus aucuparia L.) (Baikov, 1968; Rubtsov, 1971; Gubanov et al., 1976; Sokolov, 1985, 1990; Tcherepnin, 1987; Grisjuk et al., 1989; Toren, 1996; Smertina et al., 2011). The berries and seeds of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Bail. were eaten by Nanai (Goldes or Samagir) hunters from Far Eastern Russia since “it gives forces to follow a sable all the day without food” and were acclaimed as a tonic, to improve night vision and to reduce hunger, thirst and exhaustion (Panossian and Wikman, 2008).

Beverage

Aerial parts, leaves or flowers are used mainly for making beverages, while the underground parts are used rarely. Aromatic plants belonging to the Asteraceae and Lamiaceae are used to sweeten or to flavor alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages: yarrow (Achillea millefolium L.), tansy (Tanacetum vulgare L.), and oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) (Timoshenko, 1940; Wustenfeld and Gesler, 1959; Koscheev, 1981; Berson, 1991; Sokolov, 1991; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001; Soenov, 2002; Kalle and Sõukand, 2012; Sõukand et al., 2013). Juicy fruits of species belonging to the Rosaceae (rowan and bird cherry) are used often for coloring of alcoholic beverages and giving a more pronounced flavor. The fruits of these plants are used both in home made alcoholic beverages as well as in wine- and brewing industry for the production of liqueurs, bitters, wines, and beers (Wustenfeld and Gesler, 1959; Gubanov et al., 1976; Koscheev, 1981; Tcherepnin, 1987; Toren, 1996; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001). Making liqueurs out of rowan berries seems to be an old habit that has been in vogue in Russia (Timoshenko, 1940). The aroma is an important attribute of refreshing soft drinks (kvass, lemonade, and fruit morse), which are popular in the summer season.

Tonic properties of ginseng and aralia were recorded in the Far Eastern Russia by hunters and their roots were regularly added to alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages, and balsams (Grushvitsky, 1961; Zhuravlev and Kolyada, 1996; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001; Palagina et al., 2011; Palagina and Bogoutdinova, 2012).

Birch (Betula pendula Roth., and B. pubescens Ehrh.) sap has been gathered all over Russia and was usually seen as a refreshing drink (Fedorov, 1984; Tcherepnin, 1987; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001). Today, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine and Belarus are the only countries where the gathering and use of birch sap has remained an important. Large birch forests, low population density and the incorporation of sap into the former Soviet economic system facilitated this (Svanberg et al., 2012). Birch sap was utilized the diverse ways as described by the Russian ethnographer Zelenin (1927). It was drunk fresh, but also fermented by adding malt, wax, beans or rye bread.

Tea and Coffee Substitutes

After water, tea is the second most-consumed beverage worldwide (Keating et al., 2015). Although the English term “tea” generally denotes an infusion made of the leaves of Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze, many herbal teas, which usually are mono- or polyherbal formulations made from (medicinal) plant(s), are available worldwide. Historically in Russia such herbal teas often made from local species were widespread. Samovar and tea-drinking are an indispensable element of Russian culture. With C. sinensis not being available or affordable to the vast majority of population, local surrogates/substitutes of tea have been used for centuries. The best known tea surrogates were prepared from fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium L.) and, in Siberia - Bergenia spp. (Tcherepnin, 1987; Pohlebkin, 1998; Shikov et al., 2006, 2014b; Sõukand et al., 2013). Prior to the introduction of oriental (black or green) tea in Europe, E. angustifolium was esteemed as the “original Russian tea” and used widely throughout Russia and beyond (Litvintsev and Koscheev, 1988; Sõukand et al., 2013). However, this botanical drug is not in the Russian Pharmacopoeia. Extracts of black and fermented leaves of B. crassifolia are reported as appetite and energy intake suppressants (Shikov et al., 2012). Other species that are used as substitutes for tea in Russia belong to different families. First of all they are expected to bring delicious flavor, taste and nice color to the tea. Marsh Labrador tea (Ledum palustre L.), thyme (Thymus serpyllum L.), wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.), are highly aromatic. Aerial parts of Saint John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L.), oregano, thyme, leaves of lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.), flowers of linden (Tilia cordata Mill. and T. platyphyllos Scop.) are among the most popular components of herbal teas in Russia (Krylov, 1972; Koscheev, 1981; Sokolov, 1985; Grisjuk et al., 1989; Efremova, 1992; Kalle and Sõukand, 2012). Dry fruits of rose hips, hawthorn, and rowan are used as substitutes of tea (Gubanov et al., 1976; Tcherepnin, 1987; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001). Ethnobotanical data also lists dried and roasted rhizomes of dandelion (Taraxacum campylodes G.E. Haglund), dry seeds of guelder rose, roasted fruits of hawthorn, and fruits of R. canina L.as coffee substitutes (Klobukova-Alisova, 1958; Vul'f and Maleeva, 1969; Koscheev, 1981; Sokolov, 1990, 1993).

Seasoning, Spices

Aromatic herbs are very important part of local gastronomy, especial for seasoning and as spices in southern Russia. In particular, sweet flag (A. calamus L.), valerian (Valeriana officinalis L.), elecampane (Inula helenium L.) roots and rhizomes, juniper (Juniperus communis L.), and caraway (Carum carvi L.) fruits, dwarf everlast (Helichrysum arenarium (L.) Moench) and tansy flowers, yarrow, oregano, thyme, and artemisia aerial parts are normally used as aroma and flavor enhancer or digestives (Sokolov, 1988, 1994; Berson, 1991; Mashanov and Pokrovsky, 1991). These species are used both in culinary preparations at home: they are added to the soups and main dishes, salads, meats, bakery, as well as in the food industry in the production of sausages, confectionery and bakery products.

Sweets

The Russian make a kind of sweet flag and elecampane candied peel by boiling the transverse root slices in syrup, and drying (Gubanov et al., 1976; Koscheev, 1981; Berson, 1991). Candied fruits of hawthorn, bird cherry, guelder rose are used as sweetness (Gubanov et al., 1976; Koscheev, 1981; Tcherepnin, 1987; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001).

Bread Surrogates

In the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century flour and products like bread derived from it were the main foods for Russian peasants. Consequently, every an extended period of bad weather resulting in crop failure resulted in large-scale famines. This explains why a vast variety of plant parts was used for filling bread, including roots, fruits, leaves, and barks. Roots and rhizomes of some plants are known to be good sources of starch and carbohydrates. Powdered roots of Persicaria bistorta (L.) Samp. were added to the rye flour for baking bread (Rubtsov, 1971; Fedorov, 1984; Tcherepnin, 1987). Bergenia rhizomes were eaten as a substitute for bread (Vereschagin et al., 1959; Tcherepnin, 1987). Flour from black leaves of bergenia is used for cookies (Bugdaeva et al., 2005). Roots of sweet flag were used as source of starch (Berson, 1991). Whole or crushed caraway seeds, dried and ground into flour fruits of hawthorn, bird cherry, rowan, guelder rose were added to the pastry when baking bread and sweet bakery (cakes and pancakes) (Gubanov et al., 1976; Koscheev, 1981; Tcherepnin, 1987; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001).

In the middle of nineteenth century, fruits of guelder rose (Viburnum opulus) were popular in Tver province of Russia as ingredients for making “kulaga,” a porridge based on malt flour. Guelder rose fruits tenderized with flour and honey were “a tasty cuisine and refined taste for urban residents, not excluding the nobility” (Toren, 1996). Residents of Pskov province received the nickname “kalinniki” because they cooked a delicious porridge with guelder rose (“kalina” in Russian) berries and licorice flour, which was sold at the bazaar (Toren, 1996).

Despite the fact that today wild bread additives have almost completely disappeared from the European diet (Łuczaj et al., 2012), in Russia some local bakeries produce bread and buns with nettle, hawthorn, and dog rose.

Species Used in Preserves

Home made preserves have a long tradition in Russia because of the long and severe cold season. There are many canning recipes in every household for foods which have been handed down from generation to generation. Plants used for preserves can be divided into two large groups. Fresh juicy berries of rose hips, guelder rose, rowan, bird cherry, and bilberry are widely used in jam, comfiture, and marmalade. All these berries are useful for filling pies (Klobukova-Alisova, 1958; Baikov, 1968; Gubanov et al., 1976; Sokolov, 1985, 1990; Budantsev and Lesiovskaya, 2001; Soenov, 2002). The second group includes species used as spices and condiments for pickling and salting of cabbage, cucumbers, tomatoes and other vegetables, as well as mushrooms: caraway, juniper, and thyme (Rubtsov, 1971; Gubanov et al., 1976; Koscheev, 1981; Tcherepnin, 1987; Litvintsev and Koscheev, 1988; Grisjuk et al., 1989; Sõukand et al., 2013).

Conclusions

This review focuses on botanical drugs with a monograph in the Russian Pharmacopoeia 11th edition and their potential as untapped resources beyond their strictly medical uses. In general, the Soviet period was characterized by the country being closed not only from a political point of view, but also scientifically. Most commonly, research output was only available in Russian and not translated into English dramatically restricting its availability to the international community. Here such information published in Russian was evaluated focusing on medicinal species from the Russian (Soviet) Pharmacopoeia and used as a food. This highlights the importance of the Russian Pharmacopoeia as a source of information on plant species used traditionally at the interface of food and medicine.

Clearly our approach has the limitation of only focusing on species included in the pharmacopeia and, consequently, local or endemic species are mostly excluded. However, in the context of developing high value products with potential health benefits priority needs to be given to species which are widely available and not at risk of being overexploited if the demand increases.

The evidence for the individual species varies, and while we do not claim that their use could be, based on the current data, evidence-based, the review provides a basis for further research and development.

“Functional food” are foods that not only serve to provide nutrition but also can be a source for prevention and cure of various diseases. This review highlights the potential of wild Russian species monographed in its pharmacopeia for further developing new functional foods and—through the lens of their incorporation into the pharmacopeia—showcases the species' importance in Russia.

Author Contributions

AS, AT, OP, and VM have written the first draft of the manuscript. AS, OP, and MH revised and improved the various drafts and revisions. All authors have seen and agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. Online State Register of Medicinal preparations by the Ministry of Public Health of the Russian Federation, http://grls.rosminzdrav.ru/GRLS.aspx (accessed Aug 2017).

References

Alarcón, R., Pardo-de-Santayana, M., Priestley, C., Morales, R., and Heinrich, M. (2015). Medicinal and local food plants in the south of Alava (Basque Country, Spain). J. Ethnopharmacol. 176, 207–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.10.022

Annenkov, N. I. (1878). Botanical Dictionary. Reference Book for Botanist, Villagers, Horticulturists, Foresters, Chemists, Doctors, Droggists, Travelers about Russia and All the Countryfolk. St-Petersburg: Typography of the Imperial Academy of Sciences.

Baikov, G. K. (1968). “Wild fruit and berries plants from mountain forest areas of the South Urals,” in Wild and Introduced Useful Plants in Bashkiria, Vol. 2. Kazan: Kazan University publishing.

Boeva, A., Noninska, L., and Tzanowa, M. (1984). Podprawkite kato Chrana I Lekarstwo (Species as Food and Medicine). Sofia: Medizina i fiskultura.

Budantsev, A. L. (1996). Plant Resources of Russia and Neighboring Countries: Part I – Families Lycopodiaceae-Ephedraceae, Part II – Supplement, Vol. 1–7. St-Petersburg: Mir i semja−95. Nauka.

Budantsev, A. L., and Lesiovskaya, E. E. (2001). Wild Useful Plants of Russia. St-Petersburg: Izdatelstvo SPCPA.

Bugdaeva, N. P., Dambaev, B. D., and Esheeva, V. (2005). Methods of use of Bergenia crassifolia leaves in food industry. Mod. High Technol. 4:62.

CODEX STAN 321-2015 (2015). Standard for Ginseng Products. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCODEX%2BSTAN%2B321-2015%252FCXS_321e_2015.pdf

Drewnowski, A., and Gomez-Carneros, C. (2000). Bitter taste, phytonutrients, and the consumer: a review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 72, 1424–1435.

Efremova, N. A. (1967). Medicinal Plants of Kamchatka and the Commander Islands. Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky: Far East book publishing.

Efremova, N. A. (1992). Cherished Grass. Wild and Cultivated Plants of the North-Eastern Part of Russia and Their Therapeutic Properties. Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky: Kamshat.

Etkin, N. (2006). Edible Medicines. An Ethnopharmacology of Food. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

Etkin, N. L., and Ross, P. J. (1982). Food as medicine and medicine as food: an adaptive framework for the interpretation of plant utilization among the Hausa of northern Nigeria. Soc. Sci. Med. 16, 1559–1573. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90167-8

Facciola, S. (1998). Cornucopia II: A Source Book of Edible Plants. Vista, CA: Kampong Publications.

Fedorov, A. A. (1984). Plant Resources of USSR. Flowering Plants, its Chemical Composition, Application. Families Magnoliaceae-Limoniaceae. Leningrad: Nauka.

FAO/WHO (2012a). JOINT FAO/WHO FOOD STANDARDS PROGRAMME CODEX ALIMENTARIUS COMMISSION, 35th Session. Geneva.

FAO/WHO (2012b). JOINT FAO/WHO FOOD STANDARDS PROGRAMME CODEX COMMITTEE ON PROCESSED FRUITS AND VEGETABLES, 26th Session. Montego Bay.

Franz, C., Chizzola, R., Novak, J., and Sponza, S. (2011). Botanical species being used for manufacturing plant food supplements (PFS) and related products in the EU member states and selected third countries. Food Funct. 2, 720–730. doi: 10.1039/c1fo10130g

Grisjuk, N. M., Grinchak, I. L., and Elin, E. Y. (1989). Wild Food, Industrial and Honey Bee Plants of Ukraine. Kiev: Urozhaj.

Gubanov, I. A., Krylova, I. L., and Tikhonova, V. L. (1976). Wild Valuable Plants of USSR. Moscow: Mysl.

Heinrich, M. (2016). “Food-herbal medicine interface,” in Encyclopedia of Food and Health, eds L. Trugo, P. Finglas, and B. Caballero (Oxford: Elsevier), 94–98.

Holloway, P. S., and Alexander, G. (1990). Ethnobotany of the Fort Yukon Region, Alaska. Econ. Bot. 44, 214–225. doi: 10.1007/BF02860487

Izmodenov, A. G. (1989). Forest Samobranka. Honey, Vegetables and Juices Ussuri Forests. Khabarovsk: Khabarovsk Book Publishers.

Jennings, H. M., Merrell, J., Thompson, J. L., and Heinrich, M. (2014). Food or medicine? The food-medicine interface in households in Sylhet. J. Ethnopharmacol. 167, 97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.011

Kalle, R., and Sõukand, R. (2012). Historical ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants of Estonia (1770s-1960s). Acta Soc. Bot. Polon. 81, 271–281. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.033

Keating, B., Lindstrom, A., Lynch, M. E., and Blumenthal, M. (2015). Sales of tea & herbal tea increase 3.6% in United States in 2014. HerbalGram 105, 59–67.

Khan, I. A., and Abourashed, E. A. (2010). Leung's Encyclopedia of Common Natural Ingredients: Used in Food, Drugs and Cosmetics, 3rd Edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Klobukova-Alisova, E. N. (1958). Wild Useful and Harmful Plants of Bashkiria. Moscow; Leningrad: Academy of Science of USSR.

Kunakova, R. V., Zainullin, R. A., Abramova, L. M., and Anischenko, O. E. (2011). Food and Medicinal Plants in Functional Food Products. Ufa: Gilem.

Leonti, M. (2012). The co-evolutionary perspective of the food-medicine continuum and wild gathered and cultivated vegetables. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 59, 1295–1302. doi: 10.1007/s10722-012-9894-7

Lim, T. K. (2012). Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants, Vol. 1, Fruits. Dordrecht; Heidelberg; London, New York, NY: Springer.

Litvintsev, A. N., and Koscheev, A. K. (1988). Greens on the Table. Irkutsk: East Siberian Book Publishing House.

Łuczaj, Ł. (2008). Archival data on wild food plants used in Poland in 1948. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 4:4. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-4

Łuczaj, Ł., Fressel, N., and Perković, S. (2013). Wild food plants used in the villages of the Lake Vrana Nature Park (northern Dalmatia, Croatia). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 82, 275–281. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2013.036

Łuczaj, Ł., Pieroni, A., Tardío, J., Pardo-de-Santayana, M., Sõukand, R., Svanberg, I., and Kalle, R. (2012). Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe: the disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 81, 359–370. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.031

Makarova, T. I., Surzhin, S. N., Pavlova, U. G., and Sergeeva, T. V. (1960). The Use of Domestic Spices in Fishing Industry, Vol. 5. Leningrad: Trudy BIN RAN USSR, Raw Plant Material.

Markova, L. P., Belenovskaya, L. M., and Nadezhdina, T. P. (1985). Wild Useful Plants of Flora of Mongolian People's Republic. Leningrad: Nauka.

Moerman, D. E. (2010). Native American Food Plants: An Ethnobotanical Dictionary. Portland; London: Timber Press.

Molchanov, G. I., Molchanova, L. P., Gulko, N. M., Molchanov, A. G., and Suchkov, I. F. (1989). Edible Curative Plants of Caucasus. Rostov on Don: Rostov University Publisher.

Nekrasova, V. L. (1958). The History of the Study of Wild Plant Resources in the USSR, Vol. 1. Moscow: Academy of science of USSR.

Novruzov, A. R. (2014). Contents and dynamics of accumulation of the ascorbic acid in fruits of Rosa canina L. Khimija Rastitel'nogo Syr'ja 3, 221–226. doi: 10.14258/jcprm.1403221

Palagina, M. V., and Bogoutdinova, A. A. (2012). Application of Spikenard Extracts in Production of New Kinds of Non-Alcoholic Beer. News Far East. Fed. Univ. Econ. Manag. 2, 122–126.

Palagina, M. V., Teltevskaya, O. P., and Boyarova, M. D. (2011). Characterization of Plant Extracts of the Family Araliaceae and Their Possible Applications in Technology Spirits. News Far East. Fed. Univ. Econ. Manag. 1, 88–92.

Panossian, A., and Wikman, G. (2008). Pharmacology of Schisandra chinensis Bail.: an overview of Russian research and uses in medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 118, 183–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.04.020

Parada, M., Carrió, E., and Vallès, J. (2011). Ethnobotany of food plants in the Alt Emporda region (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 84, 11–25.

Pieroni, A. (2000). Medicinal plants and food medicines in the folk traditions of the upper Lucca Province, Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 70, 235–273. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00207-X

Pieroni, A., Nebel, S., Santoro, R. F., and Heinrich, M. (2005). Food for two seasons: culinary uses of non-cultivated local vegetables and mushrooms in a south Italian village. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 56, 245–272. doi: 10.1080/09637480500146564

Pojarkova, A. I. (1958). “Elderberry - Sambucus L,” in Flora of USSR, ed B. K. Shishkin (Moscow-Leningrad: Academy of science of USSR). 422–442.

Reid, B. E. (1982). Famine Foods of the Chiu-huang Pen-ts' ao. Southern Materials Centre. Taipei: INC.

Rubtsov, N. I. (1971). “Wild useful plants of Crimea,” in Proceedings of Nikitsky Botanical Garden, Vol. XLIX. Yalta.

Sears, B. (2015). Anti-inflammatory diets. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 34, 14–21. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2015.1080105

Shi, J., Ho, C. T., and Shahidi, F. (eds.). (2011). Functional Foods of the East. Boca Raton, FL; London; New York, NY: CRC Press.

Shikov, A. N., Poltanov, E. A., Dorman, H. D., Makarov, V. G., Tikhonov, V. P., and Hiltunen, R. (2006). Chemical composition and in vitro antioxidant evaluation of commercial water-soluble willow herb (Epilobium angustifolium L.) extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 3617–3624. doi: 10.1021/jf052606i

Shikov, A. N., Pozharitskaya, O. N., Kamenev, I., Yu, and Makarov, V. G. (2011). Arznei und Gewurzpflanzen in Russland. Z. Arzn. Gewurzpflanzen 16, 135–137.

Shikov, A. N., Pozharitskaya, O. N., Makarov, V. G., Wagner, H., Verpoorte, R., and Heinrich, M. (2014a). Medicinal plants of the Russian pharmacopoeia, history and applications. J. Ethnopharmacol. 154, 481–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.007

Shikov, A. N., Pozharitskaya, O. N., Makarova, M. N., Kovaleva, M. A., Laakso, I., Dorman, H. J. D., et al. (2012). Effect of Bergenia crassifolia L. extracts on weight gain and feeding behavior of rats with high-caloric diet- induced obesity. Phytomedicine 19, 1250–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.09.019

Shikov, A. N., Pozharitskaya, O. N., Makarova, M. N., Makarov, V. G., and Wagner, H. (2014b). Bergenia crassifolia (L.) Fritsch–pharmacology and phytochemistry. Phytomedicine 21, 1534–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.06.009

Smertina, E. S., Fedyanina, L. N., Kalenik, T. K., Kushnerova, N. F., and Vigerina, N. S. (2011). Application of wild plants in bakery products of functional purpose. News Far East. Fed. Univ. Econ. Manag. 3, 129–133.

Soenov, V. I. (2002). Gathering of Plant Food in Altai. Antiques of Altai, 9. Available online at: http://e-lib.gasu.ru/da/archive/2002/09/02.html (Accessed Aug 2017).

Sokolov, P. D. (1985). Plant Resources of USSR. Flowering Plants, Its Chemical Composition, Application. Families Paeoniaceae-Thymelaeaceae. Leningrad: Nauka.

Sokolov, P. D. (1987). Plant Resources of USSR. Flowering Plants, Its Chemical Composition, Application. Families Hydrangeaceae-Haloragaceae. Leningrad: Nauka.

Sokolov, P. D. (1988). Plant Resources of USSR. Flowering Plants, Its Chemical Composition, Application. Families Rutaceae-Elaegnaceae. Leningrad: Nauka.

Sokolov, P. D. (1990). Plant Resources of USSR. Flowering Plants, its Chemical Composition, Application. Families Caprifoliaceae-Plantaginaceae. Leningrad: Nauka.

Sokolov, P. D. (1991). Plant Resources of USSR. Flowering Plants, Its Chemical Composition, Application. Families Hippuridaceae-Lobeliaceae. St-Petersburg: Nauka.

Sokolov, P. D. (1993). Plant Resources of USSR. Flowering Plants, Its Chemical Composition, Application. Family Asteraceae. St-Petersburg: Nauka.

Sokolov, P. D. (1994). Plant Resources of Russia and Neighboring Countries: Flowering Plants, Its Chemical Composition, Application. Families Butomaceae-Typhaceae. St-Petersburg: Nauka

Sõukand, R., Quave, C. L., Pieroni, A., Pardo-de-Santayana, M., Tardío, J., Kalle, R., et al. (2013). Plants used for making recreational tea in Europe: a review based on specific research sites. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 9:58. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-58

State Pharmacopoeia of the USSR (1990). State Pharmacopoeia of the USSR, 11th Edn., Part 2. Moscow: Medicina.

Stryamets, N., Elbakidze, M., Ceuterick, M., Angelstam, P., and Axelsson, R. (2015). From economic survival to recreation: contemporary uses of wild food and medicine in rural Sweden, Ukraine and NW Russia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 11:53. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0036-0

Svanberg, I. (2012). The use of wild plants as food in pre-industrial Sweden. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 81, 317–327. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.039

Svanberg, I., Sõukand, R., Luczaj, L., Kalle, R., Zyryanova, O., Dénes, A., et al. (2012). Uses of tree saps in northern and eastern parts of Europe. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 81, 343–357. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.036

Tikhomirov, B. A. (1942). The Cardinal Wild Food Plants of the Leningrad Region. Leningrad: Leningrad Newspaper-Magazine and Book Publisher.

Turner, N. J., Łuczaj, Ł. J., Migliorini, P., Pieroni, A., Dreon, A. L., Sacchetti, L. E., et al. (2011). Edible and tended wild plants, traditional ecological knowledge and agroecology. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 30, 198–225. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2011.554492

Turova, A. D., and Sapozhnikova, E. N. (1989). Medicinal Plants of USSR and Their Applications. Moscow: Medizina.

Vallès, J., Bonet, M. A., Garnatje, T., Muntanè, J. O. A. N., Parada, M., and Rigat, M. (2010). Sambucus nigra L. in Catalonia (Iberian Peninsula). Under. Underexpl. Hortic. Crops 5, 393–424.

Valussi, M., and Scire, A. S. (2012). Quantitative ethnobotany and traditional functional foods. Nutrafoods 11, 85–93. doi: 10.1007/s13749-012-0032-0

Keywords: medicinal plants, traditional use, functional food, health benefits, Russian Federation

Citation: Shikov AN, Tsitsilin AN, Pozharitskaya ON, Makarov VG and Heinrich M (2017) Traditional and Current Food Use of Wild Plants Listed in the Russian Pharmacopoeia. Front. Pharmacol. 8:841. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00841

Received: 28 August 2017; Accepted: 03 November 2017;

Published: 21 November 2017.

Edited by:

Atanas G. Atanasov, Institute of Genetics and Animal Breeding (PAN), PolandReviewed by:

Fawzi Mohamad Mahomoodally, University of Mauritius, MauritiusStefan Gafner, American Botanical Council, United States

Copyright © 2017 Shikov, Tsitsilin, Pozharitskaya, Makarov and Heinrich. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexander N. Shikov, YWxleHM3OUBtYWlsLnJ1

Alexander N. Shikov

Alexander N. Shikov Andrey N. Tsitsilin

Andrey N. Tsitsilin Olga N. Pozharitskaya

Olga N. Pozharitskaya Valery G. Makarov1

Valery G. Makarov1 Michael Heinrich

Michael Heinrich