- 1Department of Plant Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 2Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Southern Area Development Project Lakki Marwat (Ministry of Planning and Development Department KPK), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

- 3Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 4Department of Biological Sciences and Chemistry, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Nizwa, Nizwa, Oman

- 5Department of Chemistry, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Abbottabad, Pakistan

- 6UoN Chair of Oman Medicinal Plants and Marine Products, University of Nizwa, Nizwa, Oman

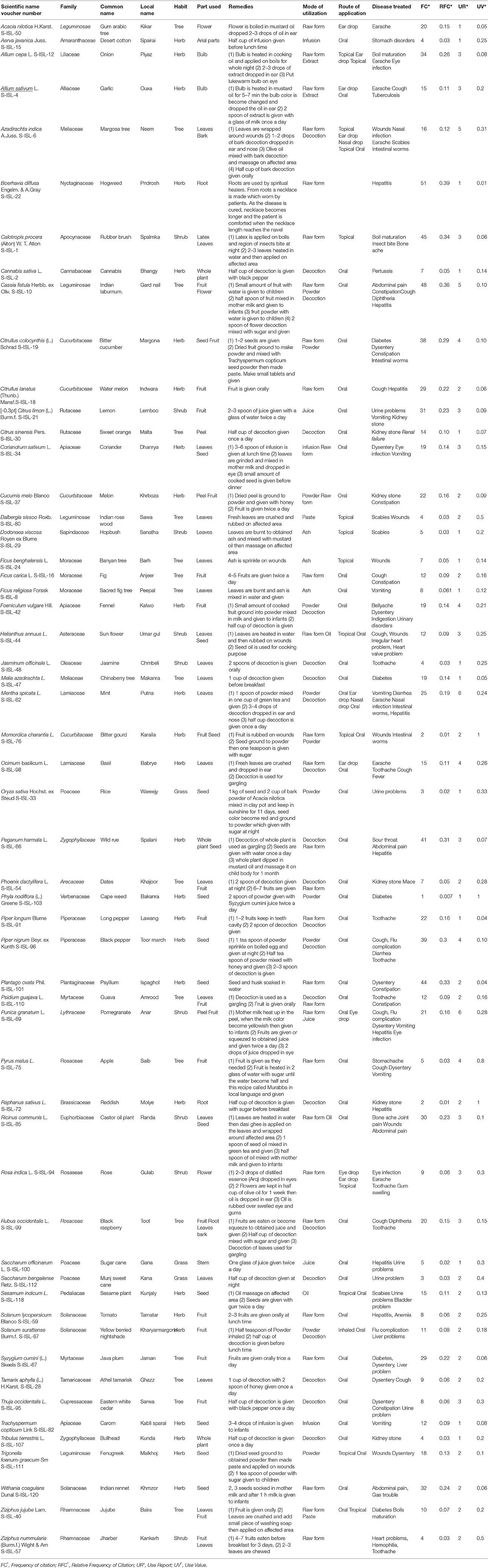

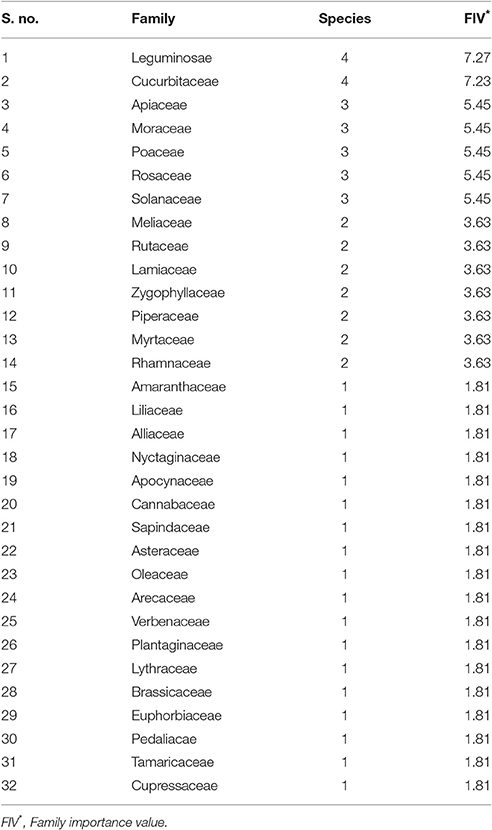

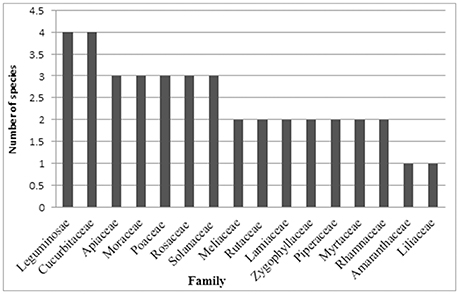

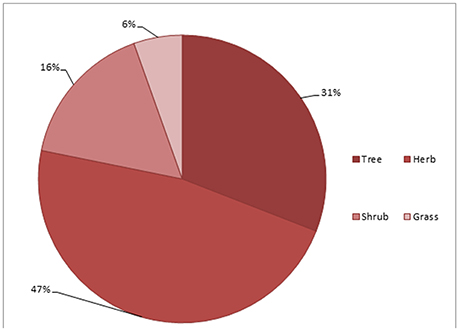

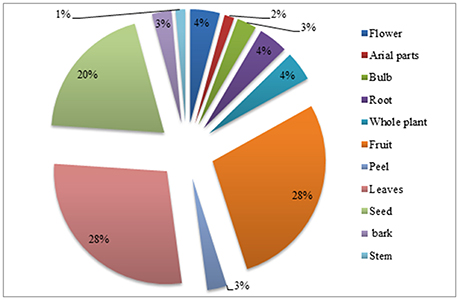

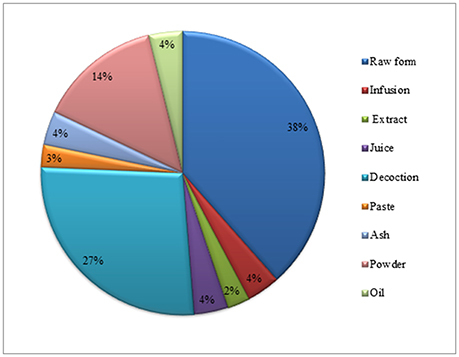

Medicinal plants are important treasures for the treatment of different types of diseases. Current study provides significant ethnopharmacological information, both qualitative and quantitative on medical plants related to children disorders from district Bannu, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province of Pakistan. The information gathered was quantitatively analyzed using informant consensus factor, relative frequency of citation and use value method to establish a baseline data for more comprehensive investigations of bioactive compounds of indigenous medicinal plants specifically related to children disorders. To best of our knowledge it is first attempt to document ethno-botanical information of medicinal plants using quantitative approaches. Total of 130 informants were interviewed using questionnaire conducted during 2014–2016 to identify the preparations and uses of the medicinal plants for children diseases treatment. A total of 55 species of flowering plants belonging to 49 genera and 32 families were used as ethno-medicines in the study area. The largest number of specie belong to Leguminosae and Cucurbitaceae families (4 species each) followed by Apiaceae, Moraceae, Poaceae, Rosaceae, and Solanaceae (3 species each). In addition leaves and fruits are most used parts (28%), herbs are most used life form (47%), decoction method were used for administration (27%), and oral ingestion was the main used route of application (68.5%). The highest use value was reported for species Momordica charantia and Raphnus sativus (1 for each) and highest Informant Consensus Factor was observed for cardiovascular and rheumatic diseases categories (0.5 for each). Most of the species in the present study were used to cure gastrointestinal diseases (39 species). The results of present study revealed the importance of medicinal plant species and their significant role in the health care of the inhabitants in the present area. The people of Bannu own high traditional knowledge related to children diseases. In conclusion we recommend giving priority for further phytochemical investigation to plants that scored highest FIC, UV values, as such values could be considered as good indicator of prospective plants for discovering new drugs and attract future generations toward traditional healing practices.

Introduction

Children are the most susceptible to various types of viral diseases and infectious due to low immune system. There are many important diseases which are common in children worldwide such as gastrointestinal, respiratory, urinary, kidney disorders, liver, ear nose throat disease (ENT), eye infection, and dental anomalies. Immune system diseases as a result of nutrition deficiency are the key element for child diseases. Evidence of the epidemic nature of diarrhea and malnutrition in children can be found in research from the Indian subcontinent, Asia, Africa, and South America. For example, in rural Bangladesh, the occurrence of diarrheal illness under the age of 5 years has been approximated to be 12.8 days per 100 child-days, which indicates that each child spent 46 days per year with diarrhea (Black et al., 1982). Other studies from Indian villages in children under 5 years of age showed varied incidences of 0.7 episodes per child per year (Bhan et al., 1986) to 2.2 episodes per child per year (Oyejide and Fagbami, 1988). Most of the plant species are used for the treatment of anemia, malaria and diarrhea among children in different parts of the world. The nutrition supplements plants are mostly used in children diseases management such as Acacia seyal Delile, Albizia coriaria Welw., Dicliptera laxata C.B.Clarke, Kalanchoe densiflora Rolfe, Persea Americana Mill. and Vernonia amygdalina Delile having different micronutrients and macronutrients except phosphorus and sodium. In different countries acute gastroenteritis causes dehydration in different aged children's and the main agents of acute gastroenteritis were Norovirus and Rotavirus. Norovirus was the most detected agent in infants and young children (24 months of age) (Bicer et al., 2012). Of the estimated total of 190 million underweight children, about 120 million live in the four most populated Asian countries, which are China, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh (UNICEF, 1993). In Pakistan, infants under 1 year old are extremely susceptible to morbidity and mortality from diarrhea; the reported death rate is 200,000 annually (Dialogue on Diarrhea, 1989).

It is well documented that herbal medicine provide a promising source of anti-diarrheal drugs and potentially valuable antimicrobial plant compounds or their extracts preferably display activity against a wide range of microorganisms (Gram et al., 2002). The commonest avoidable, cause of infant deaths are the respiratory disease (Jones, 1997). In the rural communities, wounds arising from bruises, cuts and scratches are sometimes untreated at the initial stages, which is also common problem. In most cases such wounds become septic and inflamed before they are brought to the attention of parents, who might treat such wounds in a traditional way using plant materials or seek the advice of an herbalist (Grierson and Afolayan, 1999). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 4 billion people in developing countries not only believe in the healing properties of plant species but also use them regularly (Rai et al., 2000).

Khan et al. (2013, 2015) studied the ethno-botany of the Bannu District, but their study was not specific to a particular disease. Moreover, the data was not quantitative analyzed for a particular disease. There are gaps in ethno-botanical knowledge in this region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Pakistan that have to be explored. Therefore, there was a need to explore the remaining territory in this district, using a quantitative approach for a particular disease. The present study aimed (i) to investigate and document plant species that are used for the treatment and prevention of various health problems related to child diseases; (ii) to document traditional recipes from medicinal plants, including methods of preparation, dosage, and modes of administration; (iii) to select candidate medicinal plant species of high priority for phytochemical and pharmacological analyses in our subsequent studies; and (iv) to inform the community about the diversity and conservation of medicinal plants.

Materials and Methods

Description of the Study Area

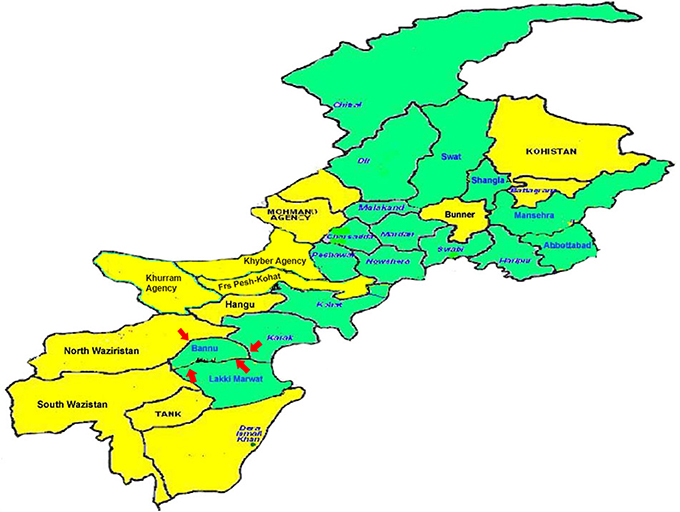

Bannu city is situated 32°16′N and 33°5′N and between 70°23′E and 71°16′E at an altitude of 371 m above sea level with an area of 1,670 square miles. It borders North Waziristan to the northwest, Karak to the northeast, Lakki Marwat to the southeast, and South Waziristan to the southwest. The population is 100% ethnic Pashtun. The main tribes are: Bannuchi, Wazir, Mehsud, Dawar, Marwat, and Bangash.

The district forms a basin drained by the Kurram River and Gambila River (Tochi River) which originating from the hills of Waziristan. The Kurram River, the larger of the two rivers, enters the district from the northwest, near the town of Bannu. From there, it runs first south-east, then south into Lakki Marwat. The Gambila River enters the district about 6 miles (9.7 km) south of the Kurram and flows in the same direction into Lakki Marwat, where the rivers eventually merge (http://kpktribune.com/index.php/en/district-bannu; Figure 1).

Field Interviews

Before starting the ethno-botanical study, contacts were made with various offices (District administration, tourism, culture, and agriculture development, traditional healers and health affairs) to seek permission and to carry out the study. The present study was conducted from March 2014 to March 2016. A total of 130 informants were interviewed (110 females, 20 males) using questionnaire to obtain indigenous knowledge of children diseases in Bannu. The informants were divided into different age groups i.e., 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, and above 60 years old. The ethnobotanical data was collected from 13 different villages of district i.e., Shamshi khel, Jandu khel, Sada khel, Shabaz azmat khel, Ismail khel, Surani, Booza khel, Mosa khel, Landidak, Bazar ahmad khan, Goriwala, Mandan, Khojari. Questionnaire (Medicinal Plants Datasheet; Supplementary Table 1) was mainly focused on the ethnobotanical claims and traditional believes of native communities and nearby people. The record questionnaires used included two sections. Section 1 dealt with personal information including age, gender, and educational background. Section 2 was about their practice including the following information: (1) the vernacular name of the plants, (2) plants part/s used for therapeutic value, (3) the way of preparation of various recipes, (4) nature of plant material, (5) relative abundance at the area, (6) habitat of the plant species, (7) mode of application, and (8) medicinal uses of particular plant. Interviews were performed in the local language (Banuchi dialect and Wazirwola). Research articles, books and relevant web pages were also studied with the aim to accumulate data of phytochemical compounds present in the plants.

Collection, Identification, and Deposition of Medicinal Plants

Ethnobotanical data was collected in four seasons (spring, autumn, summer, winter) frequent field visits. In the current study medicinal plants reported by the local informants were identified by vernacular names and collected in the field. Photographs were clipped of the spot and tag the specimen with local name. These specimens were later identified by Taxonomist Dr. Muhammad Zafar, Dr. Mushtaq Ahmad, and Dr. Mir Ajab Khan Department of Plant Sciences Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. The plant name and family has been validated through The International Plant Name Index (IPNI). The collected plant specimens were dried and preserved processed as per routine herbarium techniques recommended by Jain and Rao (1977). The Voucher specimens of each plant were deposited in the herbarium of Department of Plant sciences Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. Plant habit consisted of species characteristics such as herb, shrub and trees that were gathered from the available literature (Ali and Qaiser, 2011; Table 2).

Ailment Categories

Based on the information obtained from the informants and non-specialist informants, all the reported ailments were characterized into 14 children categories. These categories includes treating gastrointestinal diseases, respiratory disorders, cardiovascular diseases, rheumatic diseases, ear nose throat (ENT), eye infection, dermatological problems, liver disorders, urinary problems, antidote, dental problems, kidney problems, fever and circulatory diseases.

Data Analysis

The ethno-botanical data were analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet (2010). The species were listed in alphabetical order by scientific name, family, common name, local name, habit, plants part/s used, remedies, mode of utilization, route of application, diseases treated. The data collected through informants were analyzed using different quantitative indices like Use value (UV), Factor of informant consensus (FIC), and Relative frequency of citation (RFC).

Use Value (UV)

The relative importance of a locally known species is calculated by use value (Phillips et al., 1994). UV = ΣUi/ni, Where “Ui” is the number of use-reports cited by each informant for a given species and “ni” is the total number of informants which interviewed for a specific plant species. The Use values are high when there are many use-reports for a plant, which indicate the important plants. When there is few use reports, the Use values approach zero (0). UV does not differentiate whether a plant is used for a single or multiple purposes (Musa et al., 2011).

Factor of Informant Consensus (FIC)

Factor of informant consensus (FIC) was used to test the homogeneity of knowledge of medicinal plants. Before analysis, ailments were broadly classified into various categories. According to Heinrich et al. (1998) the FIC was calculated as FIC = Nur – Nt/Nur – 1. FIC values are low (near 0), if plants are selected randomly or there is no exchange of information about their use among local informants. FIC approaches (1) when there is a well-defined selection criterion in the community and/or the information is exchanged between informants (Sharma et al., 2012).

Frequency Citation (FC) and Relative Frequency Citation (RFC)

The FC of the species of plants used in the present study was calculated using the formula: Fc = (Number of times particular species was mentioned/total number of times that all species were mentioned) × 100. The relative frequency citation (RFC) index was calculated as described earlier (Tardio and Pardo-De-Santayana, 2008), using the following formula: RFC = FC/N (0 < RFC < 1). This index is obtained by dividing the number of informants citing a useful species FC or frequency of citation by the total number of informants in the survey (N). RFC value varies from 0 (when nobody refers to a plant as a useful one) to 1(when all the informants mention it as useful).

Results

Demographic Data of Local Inhabitants

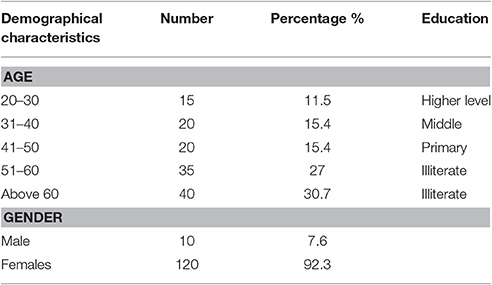

Total 130 interviews including 110 females and 10 males were conducted in the present study for children diseases. The informants were divided into five different age groups starting from 20 to 60+ years. Most of the informants were females (age 60 years and above) as children disorders information are mostly confined to women in the study area. In these informants 57.7% were illiterate (Tables 1, 2).

Most used Families and their Family Importance Value (FIV)

The present study reported the uses of 55 plant species belonging to 49 genera and 32 different families that are commonly used by local inhabitants to treat various children diseases (Table 2). The largest number of specie belong to Leguminosae and Cucurbitaceae families (4 species each) followed by Apiaceae, Moraceae, Poaceae, Rosaceae, and Solanaceae (3 species each), Meliaceae, Rutaceae, Lamiaceae, Zygophyllaceae, Piperaceae, Myrtaceae, and Rhamnaceae (2 species each), and the remaining 18 families were represented by one plant species each (Table 3; Figure 2). The highest number of medicinal plant species from these families may be due to their wider distribution and richness in the study area. The present study supported Kadir et al. (2012) who reported Leguminosae family as the dominant family (Table 3; Figure 2).

Life Form of Plants Used in Children Diseases

Herbs (47%) were the primary source of indigenous medicine among 55 species, followed by trees (31%), shrubs (16%), and grasses (6%) (Figure 3). Herbs were mostly used by local inhabitants due to greater availability and access of such herbaceous plants in the study area (Figure 3).

Plant Parts Used in Herbal Medicines

In different parts of these plants numerous secondary metabolites were present that are very important that fight against plant's pathological stress and can be used by local peoples to cure variety of diseases (Croteau et al., 2000; Shah et al., 2013, 2014a,b). Fruit and leaves were the most frequently used parts (28%), followed by seeds (20%), flower, whole plant, root (4% each), bark, peel, bulb (3% each) and stem, arial parts correspond to 3% each (Figure 4). Thus, fruit and leaves were largely used in the study area. There were no specific documented literatures on children diseases; therefore generally available ethno-botanical literature was used for comparison. The results supported the previous studies by Mahishi et al. (2005), Abo et al. (2008), González et al. (2010), Telefo et al. (2011), and Kadir et al. (2012) that leaves were dominant part used. Collection of leaves and then using them as medication is easy as compared to flowers, fruits and roots (Giday et al., 2009; Telefo et al., 2011). The digging out roots might be the cause of loss of the plant and putting the species in a susceptible condition (Figure 4) (Poffenberger et al., 1992; Martínez et al., 2000; Zheng and Xing, 2009; Rehecho et al., 2011).

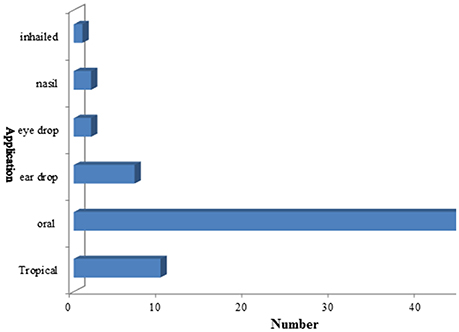

Mode of Utilization and Route of Application of Medicinal Plants

Herbal preparations were used in different forms like decoction, powder, extract, juice, infusion, paste, raw form, and cooked. Raw form utilization of these herbal plants for child diseases were the most common method (38%), followed by decoction (27%), powder (14%), oil, ash, infusion, and juice (4% each), paste (3%), and extract (2%) (Figure 5). The main route of application for herbal therapies was oral (68.5%), followed by the topical (14%), ear drop (10%), eye drop, nasal (3.5% each), and inhaled remedies (1.5%) (Figure 6). Oral mode of administration is preferred route all over the world (Figures 5, 6).

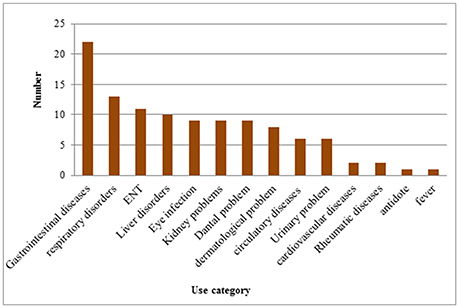

Use Categories in Children Diseases

Local inhabitants used medicinal plants species to cure different ailments. These ailments were grouped into 14 broad disease categories including gastrointestinal diseases, respiratory disorders, ear nose throat (ENT), liver disorders, eye infection, kidney problems, dental problem, dermatological problem, antidote, circulatory diseases, fever, urinary problem, cardiovascular diseases and rheumatic diseases. In the study area the highest number of plant species were used in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases (39 species) followed by respiratory disorders (16 species), ear nose throat (ENT) (13 species), liver disorders (11 species), eye infection, kidney and dental problem (10 species), dermatological problem (9 species), circulatory and urinary problem (7 species), cardiovascular and rheumatic diseases (3 species) and antidote (1 species) (Figure 7; Table 4). Ethno pharmacological studies have shown that in most parts of the world, the gastrointestinal disorder is the first use category (Heinrich et al., 1998; Miraldi et al., 2001; Ghorbani, 2005; Ghorbani et al., 2011; Mosaddegh et al., 2012). In the study area due to poor dietary environments and risky drinking water, gastrointestinal is one of the most common problem. The present study strongly agreed with the previous result of Bibi et al. (2014) and Sadeghi et al. (2014) that reported gastrointestinal and respiratory disorders as dominant problems in their studies. Ullah et al. (2013) showed a similar study in district Wana province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan using medicinal plants for the cure of gastrointestinal complaints (Figure 7).

Use Value of Medicinal Plants

The highest use value reported in the present study was 1, and the lowest value was 0.01 (Table 2). The highest use value were reported for Momordica charantia and Raphnus sativus (2 use report/use-value 1 for each), Phyla nodiflora (1 use report/use-value 1), Pyrus malus (4 use report/use-value 0.8), Dalbergia sissoo and Ziziphus nummularia (2 use report/use-value 0.5) for each, Saccharum officinarum (2 use report/use-value 0.4), Thuja occidentalis (3 use report/use-value 0.37), Rosa indica (3 use report/use-value 0.33), Oryza sativa and Saccharum bengalense (1 use report/use-value 0.33 for each) Azadirachta indica (5 use report/use-value 0.31), Punica granatum (6 use report/use-value 0.28), and smallest use values were reported for Acacia nilotica (1 use report/use-value 0.05), Plantago ovata (2 use report/use-value 0.04), Piper longum (1 use report/use-value 0.04), Boerhavia diffusa (1 use report/use-value 0.01). The high use values of plants might be attributable to their wide distribution, making these plants the, first selection for treatment. The present study is the first report of quantitative ethno-botanical data on children disease from Pakistan and to best of our knowledge no efforts have been carried out to document the medicinal flora specifically in this regard globally.

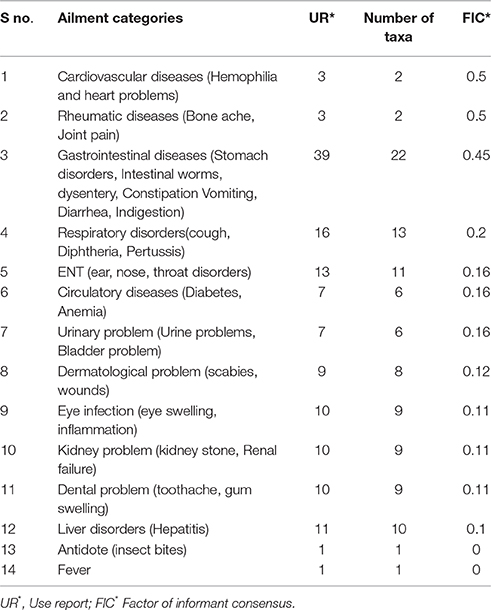

Factor of Informant Consensus (FIC)

The Factor of informant consensus (FIC) of medicinal plants in the present study ranges from (0–0.05) (Table 2). Cardiovascular and Rheumatic diseases have highest FIC values (0.5 for each). The second highest value was observed for gastrointestinal diseases (0.45), Respiratory disorders, ear nose throat (ENT) and circulatory diseases (0.16 for each). The zero FIC value was observed for antidote and fever (Table 4). As there was no previous record therefore for quantitative data comparison were used from the available ethno botanical literature of medicinal plants. Present study does not support the results of Ullah et al. (2014) and Bibi et al. (2014) reporting highest FIC value for respiratory problems and antidote while 0.45 gastrointestinal diseases in the present study, respectively. Furthermore, Ullah et al. (2014) also reported exact same FIC value for gastrointestinal diseases (0.45) during ethno-botanical survey of medicinal plants in Lakki Marwat.

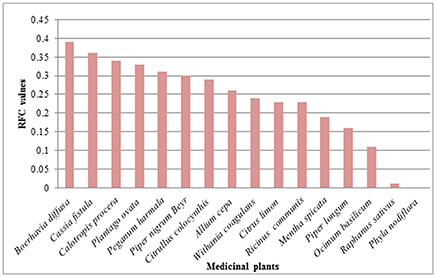

Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) and Use Reports (UR)

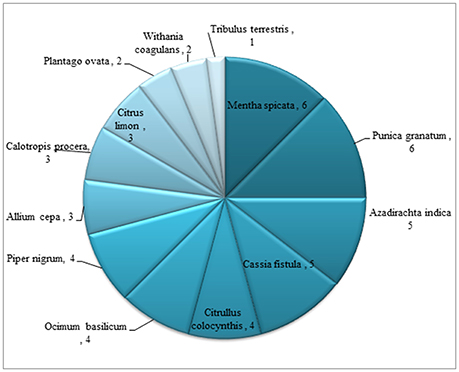

RFC value varied from 0 to 0.39 in the present study. Maximum RFC value was calculated for species Boerhavia diffusa (0.39) followed by Cassia fistula (0.36), Calotropis procera (0.34), Plantago ovata (0.33), Peganum harmala (0.31), Piper nigrum (0.30), Citrullus colocynthis (0.29), Allium cepa (0.26), Withania coagulans (0.24), Citrus limon and Ricinus communis (0.23 for each), Mentha spicata (0.19), Piper longum (0.16), Ocimum basilicum (0.11), Raphanus sativus (0.01) and Phyla nodiflora had zero RFC value (Figure 8; Table 2). Highest RFC values showed that these species are the most popular medicinal plants agreed by the majority of the informants as they are the most popular plants in District Bannu. Species Mentha spicata and Punica granatum has highest use report value (6 for each) followed by Azadirachta indica and Cassia fistula (5 each), Citrullus colocynthis, Ocimum basilicum and Piper nigrum (4 for each), Allium cepa, Calotropis procera and Citrus limon (3 for each), Plantago ovata, Withania coagulans (2 for each) and Tribulus terrestris has 1 use report value (Figures 8, 9).

Discussion

Medicinal Plants and Their Potential in Present Study

In children diseases the highest use report in the present study were documented for Punica granatum, Mentha spicata (6), Azadirachta indica. (5), Foeniculum vulgare, Cassia fistula, Pyrus malus and Piper nigrum, Ocimum basilicum (4 for each), Calotropis procera, Rosa indica, Allium sativum, Allium cepa, Ricinus communis, Citrus limon, and Peganum harmala, (3 for each), Withania coagulans, Ziziphus jujube and Plantago ovata (2 for each). These plants were also reported by others groups for other various human disorders. Withania coagulans is used as a blood purifier in hepatic disorders, dermatological problems, dyspepsia, diabetes, and flatulent colic (Panhwar and Abro, 2007), and as a diuretic, for stomach ache and refrigerant (Ullah et al., 2010). Calotropis procera is used for backache, skin infections, piles, rheumatism, asthma, cough, and snake, dog, and scorpion bites (Saqib et al., 2014) while it has been used for toothache, abscesses and joint pain by Bhatia et al. (2014). The latex of Calotropis procera is also used to cure eczema, snake bites, ringworms, and abdominal cramps, to soften the affected area, and wound healing (Marwat et al., 2008; Abbasi et al., 2010). Plantago ovata is mostly used for the treatment of jaundice (Rashid et al., 2012), spermatorrhea, constipation (Marwat et al., 2008), dysentery, diarrhea (Sharma and Kumar, 2007) and hyperacidity (Islam et al., 2011). Allium cepa is important for prevention of heart diseases, boils maturation and insect bite, Allium sativum, mostly used for prevention of heart diseases, carminative, boils maturation, earache, Citrus limon used against fungal infections of skin (Ullah et al., 2014). Sesamum indicum used for constipation (Noumi and Yomi, 2001). Cucumis melo for constipation (Qureshi, 2012). Foeniculum vulgare is used for anemia, jaundice, liver inflammation, Piper nigrum for abdominal pain, and Ziziphus jujube for cough (Abbasi et al., 2010). Ricinus communis is mostly used for constipation and sedative (Alam et al., 2011).

Medicinal Plant Use Knowledge in the Area

The results of the present study show that the older informants prevails more knowledge than younger ones. The female informants (aged 50 or 60) possessed higher knowledge of medicinal plants used for children's health care. This is not surprising because certain abilities such as medicinal plants knowledge are developed over a life time. A large part of the traditional knowledge is embedded in practices that the people involved in Pfeiffer and Butz (2005) and Guimbo et al. (2011), for example, in rural Niger, female knew more about edible plants than male because they have concern and responsibility for daily food production, whereas men have a better knowledge of fodder and construction (Guimbo et al., 2011). In the present study few plants such as Areca catechu and Myristica fragrans were not grown in the study area therefore they were purchased from market.

Threats to Medicinal Plants in the Study Area

In the study area many medicinal plants are used and the use of traditional plant knowledge is abundant. The role of medicinal plants in the primary healthcare of the villagers has been reduced because of easier access to modern medicines and changes in their lifestyle. A similar condition was also observed within Huai Labaoya and Samoon Mai Village in Nan Province (Srithi et al., 2009). In Vietnam the development of nurseries for the spread of plants by seeds and stem cuttings on a community level was also effectively practiced (Khanh et al., 2000). Majority of the local people are illiterate especially in the rural areas of the district and the earning sources are only agriculture and livestock. Some of the local inhabitants collect medicinal plants and sell them to the local herb sellers in very low-price and these species are imported to the pharmaceutical companies. Urbanization, over grazing, and uprooting of medicinal plants are severe threats in the study area. These threats increase the risk of plants extinction, therefore proper management strategies should be adopted for a strict control over their protection and safety. The cultivation of medicinal plants and viable use of wild flora should be promoted in the area; thus might help in improving the socioeconomic condition of the local inhabitants.

Conclusion

The present study provides valuable information about medicinal plants used by local informants to cure children diseases in District Bannu, KPK, Pakistan. 55 medicinal plant species belonging to 49 genera and 32 families were used in the present study. It was first attempt to document ethno-botanical information using quantitative approaches on specific diseases in the study area. The leaves and fruits were mostly used parts (28%), herbs were the most used life form (47%), decoction was the way of administration (27%) and oral ingestion was the main way of application (68.5%) used in herbal medication. The quantitative approaches such as Factor of informant consensus (FIC), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), and Use Report (UV) were used in the present study. In children diseases highest use values and FIC values were reported for Momordica charantia, Raphnus sativus (1 for each) and Cardiovascular, Rheumatic diseases (0.5 for each), respectively. The results represent useful and long-lasting information about medicinal plants, which may preserve indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants and attract future generations toward traditional healing practices. Due to present study, plants that scored highest FIC, UV values, could be considered as good indicator of prospective plants for discovering new drugs. However there is a gradual loss of traditional knowledge in new generation. Thus it is felt important to document and reconstitute the remainders of the ancient medical practices, which exist in the study area as well as other parts of the region and preserve this knowledge for future generations. The traditional medicine used in the region lacks physiotherapeutic evidence. It is necessary to perform phytochemical and pharmacological studies to explore the potential of such plants herbal drug discovery.

Author Contributions

SS carried out the study and wrote the manuscript; SA, MU, MA, MAh, JH, FM, UF, and AK designed the experiments, did sampling and supervised the work; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to offer an articulate gratitude for Dr. Mir Ajab Khan Department of Plant sciences Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad who will be always shining star in the sky of success. All the authors gratefully acknowledge family and local peoples for providing their valuable information help in plant collection and hospitality as well.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2017.00430/full#supplementary-material

References

Abbasi, A. M., Khan, M. A., Ahmad, M., Zafar, M., Jahan, S., and Sultana, S. (2010). Ethnopharmacological application of medicinal plants to cure skin diseases and in folk cosmetics among the tribal communities of North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 128, 322–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.052

Abo, K. A., Fred-Jaiyesimi, A. A., and Jaiyesimi, A. E. A. (2008). Ethnobotanical studies of medicinal plants used in the management of diabetes mellitus in South Western Nigeria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 115, 67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.09.005

Alam, N., Shinwari, Z. K., Ilyas, M., and Ullah, Z. (2011). Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants of Chagharzai valley, District Buner, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 43, 773–780.

Ali, H., and Qaiser, M. (2011). Contribution to the red List of pakistan: a case study of the narrow endemic Silene longisepala (Caryophyllaceae). Oryx 45, 522–527. doi: 10.1017/S003060531000102X

Bhan, M. K., Arora, N. K., Ghani, O. P., Ramachandran, K., Khoshoo, V., and Bhandari, N. (1986). Major factors in diarrhea related mortality among children. Ind. J. Med. Res. 83, 9–12.

Bhatia, H., Sharma, Y. P., Manhas, R. K., and Kumar, K. (2014). Ethnomedicinal plants used by the villagers of district Udhampur, J&K, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 151, 1005–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.017

Bibi, T., Ahmad, M., Tareen, R. B., Tareen, N. M., Jabeen, R., Rehman, S. U., et al. (2014). Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in district Mastung of Balochistan province-Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 157, 79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.08.042

Bicer, S., Col, D., Kucuk, O., Erdag, G., Giray, T., Vitrinel, A., et al. (2012). Is there any difference between the symptomatology and clinical findings of viral agents that caused dehydration? Arch. Dis. Child. 97:A258. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302724.0901

Black, R. E., Brown, K. H., Becker, S., and Yunus, M. (1982). Longitudinal studies of infectious diseases and physical growth of children in rural Bangladesh, I. Patterns of morbidity. Am. J. Epidemiol. 115, 305–314. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113307

Croteau, R., Kutchan, T. M., and Lewis, N. G. (2000). Secondary Metabolites. Biochem Mol Biol Plants. 7, 1250–1318.

Ghorbani, A. (2005). Studies on pharmaceutical ethnobotany in the region of Turkmen Sahra, north of Iran (Part 1): general results. J. Ethnopharmacol. 102, 58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.035

Ghorbani, A., Langenberger, G., Feng, L., and Sauerborn, J. (2011). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants utilised by Hani ethnicity in Naban River Watershed National Nature Reserve, Yunnan, China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 134, 651–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.011

Giday, M., Asfaw, Z., and Woldu, Z. (2009). Medicinal plants of the Meinit ethnic group of Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 124, 513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.009

González, J. A., García-Barriuso, M., and Amich, F. (2010). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants traditionally used in the Arribes del Duero, western Spain. J. Ethnopharmacol. 131, 343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.022

Gram, L. R., Rasch, M., Bruhn, J. B., Christensen, A. B., and Givskov, M. (2002). Food spoilage- interactions between food spoilage bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 78, 79–97. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00233-7

Grierson, D. S., and Afolayan, A. J. (1999). An ethnobotanical study of plants used for the treatment of wounds in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 67, 327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00082-3

Guimbo, I. D., Muller, J., and Larwanou, M. (2011). Ethnobotanical knowledge of men, women and children in rural niger : a mixed- methods approach. Ethnobot. Res. App. 9, 235–242. doi: 10.17348/era.9.0.235-242

Heinrich, M., Ankli, A., Frei, B., Weimann, C., and Sticher, O. (1998). Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers' consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 47, 1859–1871. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00181-6

Islam, N., Afroz, R., Sadat, A. F. M. N., Seraj, S., Jahan, F. I., Islam, F., et al. (2011). A survey of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal practitioners in three villages of Jessore District, Bangladesh. Am. Eur. J. Sustain. Agric. 5, 219–225.

Jain, S. K., and Rao, R. R. (1977). A Handbook of Field and Herbarium Methods. New Delhi: Today and Tomorrow Printers and Publishers.

Jones, O. D. (1997). Evolutionary analysis in law: an introduction and application to child abuse. N.C. Cent. Rev. 75:1117.

Kadir, M. F., Sayeed, M. S. B., and Mia, M. M. K. (2012). Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used by indigenous and tribal people in Rangamati, Bangladesh. J. Ethnopharmacol. 144, 627–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.10.003

Khan, R. U., Mehmood, S., Khan, S. U., and Jaffar, F. (2013). Ethnobotanical study of food value Flora of District Bannu Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. J. Med. Plants. Stud. 1, 93–106.

Khan, R. U., Mehmood, S., Muhammad, A., Mussarat, S., and Khan, S. U. (2015). Medicinal plants from Flora of Bannu used traditionally by North West Pakistan's women to cure gynecological disorders. Am. Eur. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 15, 553–559. doi: 10.5829/idosi.aejaes.2015.15.4.12575

Khanh, T. C., On, T. V., Tien, D. D., and Jackson, P. W. (2000). “Domestication of wild-sourced and useful native plants at community level in the Tam Dao National Park Buffer Zone,” in The Project of Conservation and Unsustainable Use of Useful Plants Resources in Tam Dao National Park, Tam Dao National Park.

Mahishi, P., Srinivasa, B. H., and Shivanna, M. B. (2005). Medicinal plant wealth of local communities in some villages in Shimoga District of Karnataka, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 98, 307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.035

Martínez, J. V., Bernal, Y., Henry, A., and Cáceres, A. (2000). Fundamentos de agrotecnología de cultivo de plantas medicinales iberoamericanas. RCPM 5:125.

Marwat, S. K., Khan, M. A., and Ahmad, M. (2008). Ethnophytomedicines for treatment of various dieases in D. I. Khan District. SJA 24, 293–303.

Miraldi, E., Ferri, S., and Mostaghimi, V. (2001). Botanical drugs and preparations in the traditional medicine of West Azerbaijan (Iran). J. Ethnopharmacol. 75, 77–87. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00381-0

Mosaddegh, M., Naghibi, F., Moazzeni, H., Pirani, A., and Esmaeili, S. (2012). Ethnobotanical survey of herbal remedies traditionally used in Kohghiluyeh va Boyer Ahmad province of Iran. J. Ethnopharmacol. 141, 80–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.02.004

Musa, M. S., Abdelrasool, F. E., Elsheikh, E. A., Ahmed, L. A. M. N., Mahmoud, A. L. E., and Yagi, S. M. (2011). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Blue Nile State, South- eastern Sudan. J. Med. Plants 5, 4287–4297.

Noumi, E., and Yomi, A. (2001). Medicinal plants used for intestinal diseases in Mbalmayo Region, Central Province, Cameroon. Fitoterapia 72, 246–254. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(00)00288-4

Oyejide, C. A., and Fagbami, A. H. (1988). An epidemiological study of rotavirus diarrhea in a cohort of Nigerian infants. II. Incidence of diarrhea in first two years of life. Int. J. Epidemiol. 17, 908–911. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.4.908

Panhwar, A. Q., and Abro, H. (2007). Ethnobotanical studies of Mahal Kohistan (Khirthar national park). Pak. J. Bot. 39, 2301–2315.

Pfeiffer, J. M., and Butz, R. J. (2005). Assessing cultural and ecological variation in ethnobiological research: the importance of gender. J. Ethnopharmacol. 25, 240–278. doi: 10.2993/0278-0771(2005)25[240:acaevi]2.0.co;2

Phillips, O., Gentry, A. H., Renyel, C., Wilkin, P., and Galvez-Durand, B. (1994). Quantitative ethnobotany and amazonian conservation. Conserv. Biol. 8, 225–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1994.08010225.x

Poffenberger, M., McGean, B., Khare, A., and Campbell, J. (1992). Field Method Manual, vol. II. Community Forest Economy and Use Pattern: Participatory and Rural Appraisal (PRA) Methods in South Gujarat India. New Delhi: Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development.

Qureshi, R. (2012). Medicinal flora of hingol national park, Baluchistan, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 44, 725–732.

Rai, L. K., Prasad, P., and Sharma, E. (2000). Conservation threats to some important medicinal plants of the Sikkim Himalaya. Biol. Conserv. 93, 27–33. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(99)00116-0

Rashid, M., Rafique, F. B., Debnath, N., Rahman, A., Zerin, S. Z., Harun-ar-Rashid, et al. (2012). Medicinal plants and formulations of a community of the tonchongya tribe in Bandarban District Of Bangladesh. Am. Eur. J. Sustain. Agric. 6, 292–298.

Rehecho, S., Uriarte-Pueyo, I., Calvo, J., Vivas, L. A., and Calvom, M. I. (2011). Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants in Nor-Yauyos, a part of the Landscape Reserve Nor-Yauyos-Cochas, Peru. J. Ethnopharmacol. 133, 75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.09.006

Sadeghi, Z., Kuhestani, K., Abdollahi, V., and Mahmood, A. (2014). Ethnopharmacological studies of indigenous medicinal plants of Saravan region, Baluchistan, Iran. J. Ethnopharmacol. 153, 111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.01.007

Saqib, Z., Mahmood, A., Malik, R. N., Mahmood, A., Syed, J. H., and Ahmad, T. (2014). Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants in Kotli Sattian, Rawalpindi district, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 151, 820–828. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.034

Shah, G. M., Jamal, Z., and Hussain, M. (2013). Phytotherapy among the rural women of district Abbotabad. Pak. J. Bot. 45, 253–261.

Shah, N. A., Khan, M. R., and Nadhman, A. (2014b). Antileishmanial, toxicity, and phytochemical evaluation of medicinal plants collected from Pakistan. BioMed Res. Int. 10–16. doi: 10.1155/2014/384204

Shah, N. A., Khan, M. R., Naz, K., and Khan, M. A. (2014a). Antioxidant potential, DNA protection, and HPLC-DAD analysis of neglected medicinal jurinea dolomiaea roots. Biomed Res. Int. 2014:726241. doi: 10.1155/2014/726241

Sharma, R., Manhas, R. K., and Magotra, R. (2012). Ethnoveterinary remedies of diseases among milk yielding animals in Kathua, Jammu and Kashmir, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 141, 265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.02.027

Srithi, K., Balslev, H., Wangpakapattanawong, P., Srisanga, P., and Trisonthi, C. (2009). Medicinal plant knowledge and its erosion among the Mien (Yao) in northern Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 123, 335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.02.035

Tardio, J., and Pardo-De-Santayana, M. (2008). Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ. Bot. 62, 24–39. doi: 10.1007/s12231-007-9004-5

Telefo, P. B., Lienou, L. L., Yemele, M. D., Lemfack, M. C., Mouokeu, C., Goka, C. S., et al. (2011). Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for the treatment of female infertility in Baham, Cameroon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 136, 178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.036

Ullah, M., Khan, M. U., Mahmood, A., Malik, R. N., Hussain, M., Wazir, S. M., et al. (2013). An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Wana district south Waziristan agency, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 150, 918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.032

Ullah, R., Hussain, Z., Iqbal, Z., Hussain, J., Khan, F. U., Khanm, N., et al. (2010). Traditional uses of medicinal plants in Darra Adam Khel NWFP Pakistan. J. Med. Plants Res. 4, 1815–1821.

Ullah, S., Khan, M. R., Shah, N. A., Shah, S. A., Majid, M., and Farooq, M. A. (2014). Ethnomedicinal plant use value in the Lakki Marwat District of Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 158, 412–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.048

Keywords: Bannu, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), ethnomedicinal plants, children disorders, use value, factor of informant consensus (FIC)

Citation: Shaheen S, Abbas S, Hussain J, Mabood F, Umair M, Ali M, Ahmad M, Zafar M, Farooq U and Khan A (2017) Knowledge of Medicinal Plants for Children Diseases in the Environs of District Bannu, Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa (KPK). Front. Pharmacol. 8:430. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00430

Received: 29 January 2017; Accepted: 15 June 2017;

Published: 17 July 2017.

Edited by:

Luc Pieters, University of Antwerp, BelgiumReviewed by:

Adnan Amin, Gomal University, PakistanElena Gonzalez Burgos, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2017 Shaheen, Abbas, Hussain, Mabood, Umair, Ali, Ahmad, Zafar, Farooq and Khan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Javid Hussain, javidhej@unizwa.edu.om

Muhammad Zafar, catlacatla@hotmail.com

Ajmal Khan, ajmalkhan@ciit.net.pk

Shabnam Shaheen1,2

Shabnam Shaheen1,2 Safdar Abbas

Safdar Abbas Muhammad Umair

Muhammad Umair Umar Farooq

Umar Farooq Ajmal Khan

Ajmal Khan