95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Pharmacol. , 30 November 2016

Sec. Experimental Pharmacology and Drug Discovery

Volume 7 - 2016 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00449

This article is part of the Research Topic Precision Medicine: an Approach of Multiple Targeted Therapy in Cancer View all 15 articles

We have recently generated a novel medulloblastoma (MB) mouse model with activation of the Shh pathway and lacking the MB suppressor Tis21 (Patched1+/−/Tis21KO). Its main phenotype is a defect of migration of the cerebellar granule precursor cells (GCPs). By genomic analysis of GCPs in vivo, we identified as drug target and major responsible of this defect the down-regulation of the promigratory chemokine Cxcl3. Consequently, the GCPs remain longer in the cerebellum proliferative area, and the MB frequency is enhanced. Here, we further analyzed the genes deregulated in a Tis21-dependent manner (Patched1+/−/Tis21 wild-type vs. Ptch1+/−/Tis21 knockout), among which are a number of down-regulated tumor inhibitors and up-regulated tumor facilitators, focusing on pathways potentially involved in the tumorigenesis and on putative new drug targets. The data analysis using bioinformatic tools revealed: (i) a link between the Shh signaling and the Tis21-dependent impairment of the GCPs migration, through a Shh-dependent deregulation of the clathrin-mediated chemotaxis operating in the primary cilium through the Cxcl3-Cxcr2 axis; (ii) a possible lineage shift of Shh-type GCPs toward retinal precursor phenotype, i.e., the neural cell type involved in group 3 MB; (iii) the identification of a subset of putative drug targets for MB, involved, among the others, in the regulation of Hippo signaling and centrosome assembly. Finally, our findings define also the role of Tis21 in the regulation of gene expression, through epigenetic and RNA processing mechanisms, influencing the fate of the GCPs.

About 30% of medulloblastomas (MBs), the pediatric tumor of the cerebellum, originates from the granule neuron precursor cells (GCPs) located in the external granular layer (EGL), at the surface of the developing cerebellum, in consequence of hyperactivation of the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) pathway (Kadin et al., 1970; Schüller et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008; Gibson et al., 2010; Northcott et al., 2012). Other MB subtypes may originate from neural precursors of the cerebellar embryonic anlage, different from GCPs and dependent on Wnt signaling, or from GCPs with activation of different pathways (group 3), or also from neural precursors of unknown origin (group 4; Northcott et al., 2012). GCPs intensely proliferate postnatally in the EGL, before exiting the cell cycle and migrating inward to form the mature internal granular layer (IGL; Hatten, 1999). GCPs in the EGL are forced to divide by the proliferative molecule Shh, secreted by Purkinje neurons (Dahmane and Ruiz i Altaba, 1999; Wallace, 1999; Wechsler-Reya and Scott, 1999). It is believed that the prolonged mitotic activity of the GCPs, consequent to hyperactivation of the Shh pathway, makes them potential targets of transforming insults (Wang and Zoghbi, 2001).

We have previously shown that mice lacking one allele of Ptch1, which develop MB with low frequency as result of the activation of the Shh pathway (Hahn et al., 1998), when crossed with mice knockout for the MB suppressor Tis21 develop MB with very high frequency (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a,b). We identified as responsible for this effect a defect of migration of the GCPs that, remaining for a longer period in the EGL under the proliferative influence of Shh, developed tumor more frequently. Whole-genome analyses of expression and function indicated that the key molecule responsible for the lack of migration of GCPs is the chemokine Cxcl3 (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a). Together with Cxcl3, we identified other 187 gene sequences, 163 of which have a functional product, whose expression in double mutant Ptch1 heterozygous/Tis21 knockout mice was modified, relative to Ptch1 heterozygous mice in Tis21 wild-type background (single mutants; Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a). The set of genes whose expression significantly differs in the comparison Ptch1+/−/Tis21 wild-type vs. Ptch1+/−/Tis21KO will be hereafter defined as Set A (Figure 1).

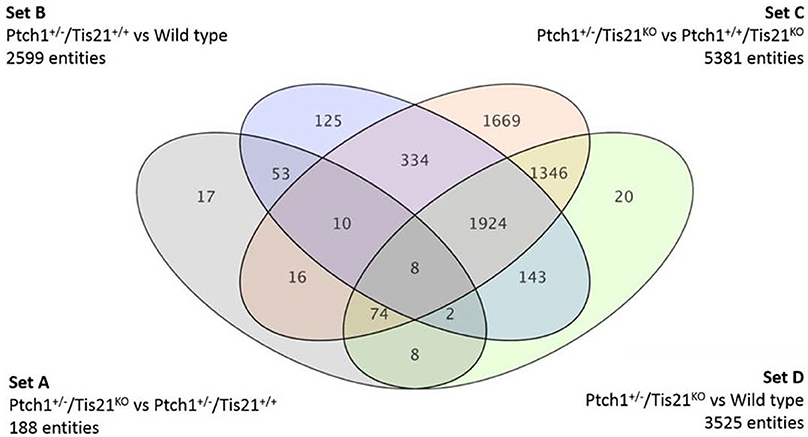

Figure 1. A Venn diagram showing four genotype pairwise comparisons and the intersection of their differentially expressed gene/sequences set A–D. Set A corresponds to the pairwise comparison Ptch1+/−/Tis21KO vs. Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+; Set B refers to Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+ vs. wild type; Set C concerns Ptch1+/−/Tis21KO vs. Ptch1+/+/Tis21KO; Set D represents the double-knockout contribution in background wild type.

Here, we aimed to expand the functional investigation of the previous whole-genome analysis of gene expression alterations occurring at the onset of tumorigenesis in the GCPs, in order to further examine the set of genes whose expression is modified in Ptch1 heterozygous/Tis21 knockout double mutant mice relative to Ptch1 heterozygous/Tis21 wild-type mice (Set A).

Given that Tis21 mutation has a strong tumorigenic effect in Ptch1 heterozygous background, with a high increase of MB frequency, we assumed that the transcriptional changes occurring in the Set A of 163 genes after Tis21 ablation in Ptch1 background were at the origin of the increased tumorigenicity observed. These genes, referred to as Tis21-dependent—given that their expression is by definition modified by the ablation of Tis21 in Ptch1 heterozygous background—will be divided in up-regulated and down-regulated, relative to Ptch1 heterozygous/Tis21 wild-type mice. It is worth noting that among the genes in Set A whose expression is down-regulated abound those with tumor-inhibitory activity (e.g., Pag1, PadI4, Lats2, and Cxcl3), while among the up-regulated genes are present tumor facilitators (e.g., Rab18, Dek).

Phenotypically, our genomic data refer to GCPs at a very early pre-neoplastic stage, having been isolated from 7 day-old mice, i.e., when the neoplastic lesions have not yet emerged.

The data analyzed interestingly lead to: (i) a link between the Shh signaling and the impairment of the GCPs migration, through a Shh-dependent deregulation of the receptor-mediated endocytosis pathway; (ii) a possible lineage shift of Shh-type GCPs toward retinal precursor phenotype/toward the neural cell type involved in group 3 MB; (iii) the identification of a subset of putative drug targets for MB involved in the regulation of cell cycle, Pdgf, Rapamycin target protein 1 and Hippo signaling pathways. Finally, our findings indicate a role of Tis21 in the regulation of gene expression, through epigenetic and RNA processing mechanisms.

Genome-wide expression study design and experimental procedures, of GCPs isolated from the EGL of P7, mice were previously performed with Whole Mouse Genome Microarrays (Agilent Technologies), as described in Farioli-Vecchioli et al. (2012a). GCPs were isolated from Ptch1 heterozygous/Tis21 knockout double mutant and Ptch1 heterozygous/Tis21 wild-type mice of either sex (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a). In order to extract the mRNA from GCPs for microarray analysis, for each of the four genotypes were used 4 replicates of GCPs isolated from 3-4 mice each, for a total of about 64 mice (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a). The experiments and all animal procedures were completed in accordance with the current European (directive 2010/63/EU) Ethical Committee guidelines and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Italian Ministry of Health (authorized protocol number 14/2009 dated 14/12/2009, expiry date 14/12/2012, according to Law Decree 116/92). Experiments performed after 14/12/2012 are authorized by the Ethical Committee of the Italian Ministry of Health by protocols 307/2013-B and 193/2015-PR expiring 30/03/2020.

Raw data from microarrays experiments were processed and analyzed using GeneSpringGX 12.5 (Agilent Technologies), as already described (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a). Pathway enrichment analysis of Set B and Set D genes was performed with MetaCore™ by Thomson Reuters (Ekins et al., 2007). Pathways with corrected enrichment p-value p < 0.05 were considered significant. MetaCore™ integrated software for functional analysis and its manually curated database have also been used for functional annotation of Tis21-dependent Set A genes, together with DAVID Bioinformatics Resources version 6.7 public database by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NIH) (Huang da et al., 2009a,b), Mouse Genome Database (MGD) by The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine (Blake et al., 2014), Cerebellar Development Transcriptome Data Base (CDT-DB) by NIJC, RIKEN-BSI, Japan (Sato et al., 2008) and Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) by the UniProt Consortium (Consortium, 2014).

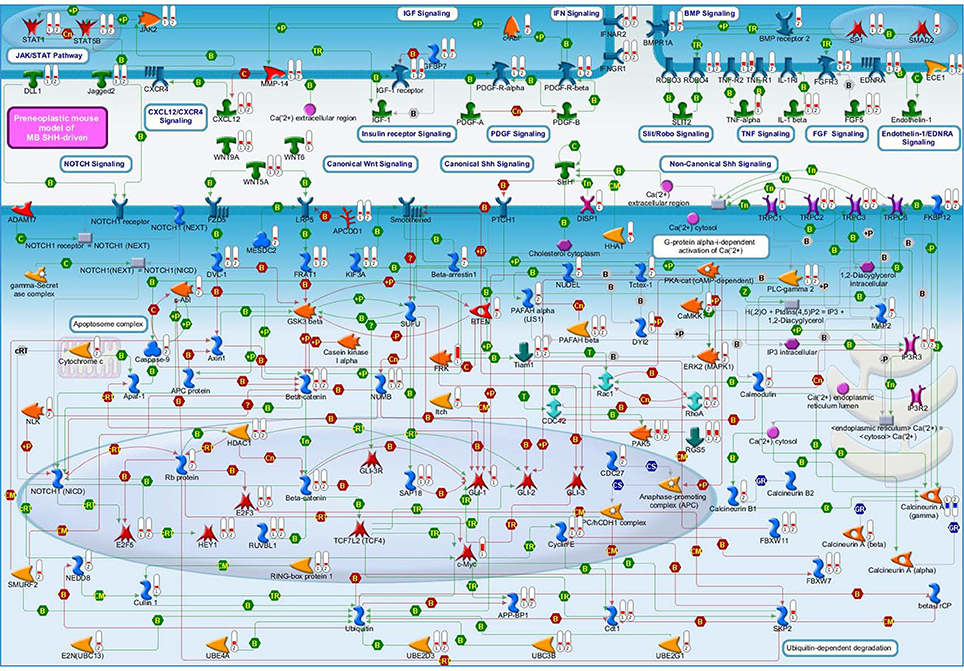

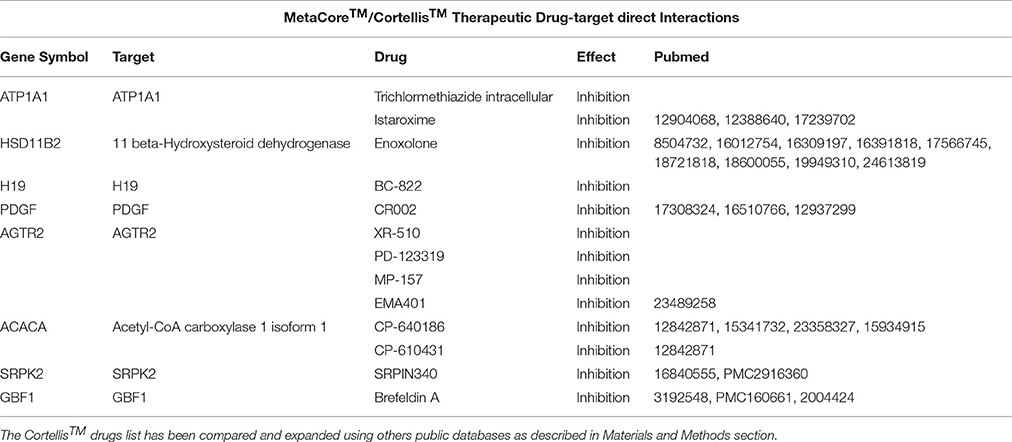

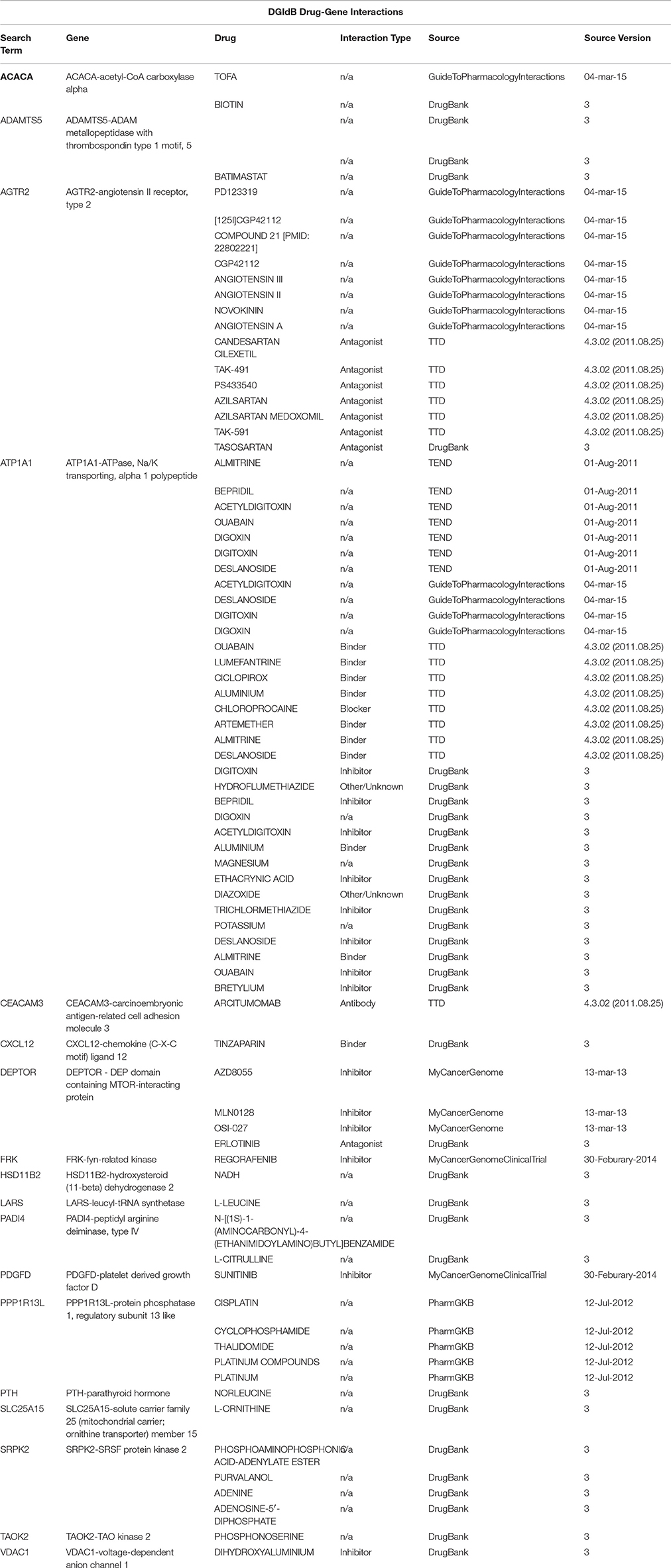

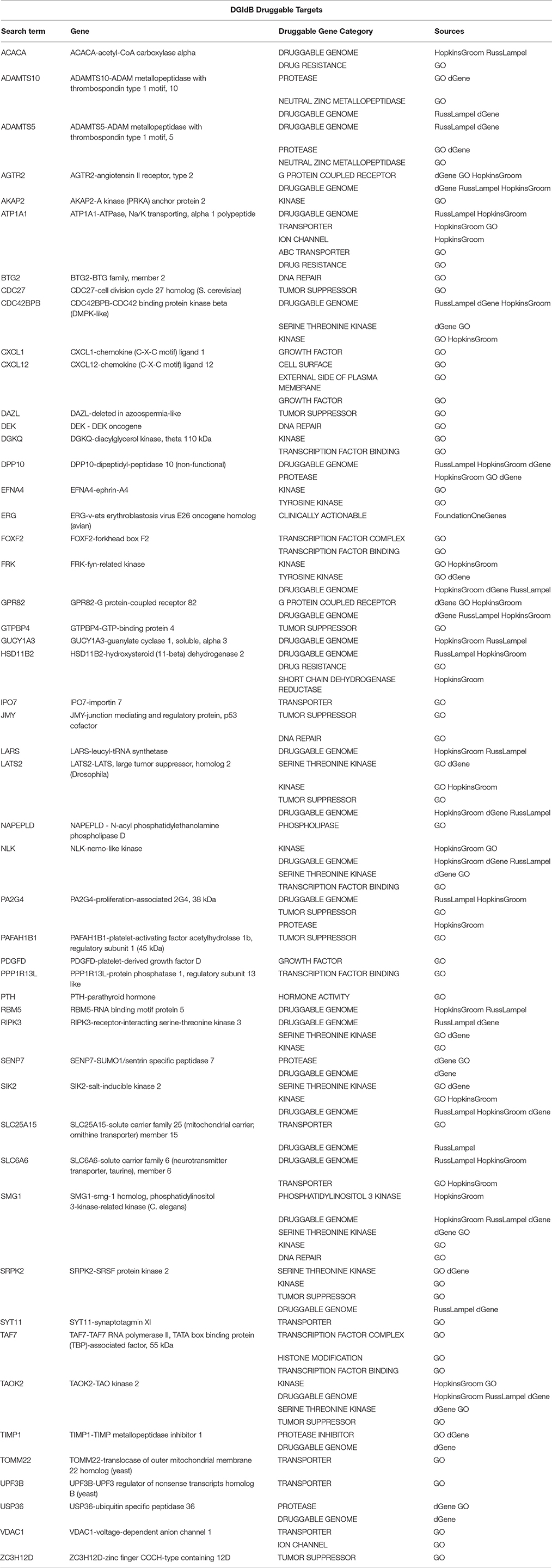

To identify potential drug targets among the Set A differentially expressed genes, we have used the drug target selection tool via gene list analysis by MetaCore™ (Thomson Reuters) (Ekins et al., 2007) and Thomson Reuters Cortellis Drug Viewer tool (also available on MetaCore™ platform) via pathway analysis. The search has been performed among human primary/direct (Table 3) and secondary/indirect (Table 4) drug targets (see OrthoDB Kriventseva et al., 2015, for the comparison between human and mouse orthologs). The drugs have been taken into account for their targets and not for their use, so not only anti-neoplastic agents are listed in Tables 3–6. Cortellis™ drugs results were compared with records contained in public databases such as DrugBank version 4.2 (Knox et al., 2011; Law et al., 2014), PubChem Compound by NIH (Bolton et al., 2010) and Naturally Occurring Plant based Anticancerous Compound-Activity-Target (Mangal et al., 2013). Finally, to further annotate Set A list genes with respect to known drug-gene interactions and potential druggability, in both mouse and human, we have used the search tools on The Drug Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb) (Griffith et al., 2013) via gene list (Figure 3, Tables 4, 5).

By using oligonucleotide microarrays, we monitored the transcriptomic profiles belonging to GCPs isolated at postnatal day 7 (P7), i.e., cells under the proliferative and tumorigenic influence of Shh deregulated signaling in EGL. When expression profiles of genes from either Ptch1 heterozygous GCPs in Tis21 wild-type background (Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+) or double mutant (Ptch1+/−/Tis21KO) GCPs were compared with the control wild-type (Ptch1+/+/Tis21+/+), a consistent subset of genes showed a significant change in expression level, i.e., 2599 in Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+ (Figure 1 Set B) and 3525 in Ptch1+/−/Tis21KO (Figure 1 Set D). Instead, the contribution of Ptch1+/− in Tis21 Knockout background was exemplified by 5381 differentially expressed genes (Figure 1 Set C; Ptch1+/−/Tis21KO vs. Ptch1+/+/Tis21KO).

Here we analyze and discuss mainly those genes that were differentially expressed in the pairwise comparison Ptch1+/−/Tis21KO vs. Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+ (Set A; Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1), to identify the contribution by Tis21 in Ptch1 heterozygous background. These genes are critical as they underlie the great increase of MB frequency observed in Ptch1 heterozygous mice ablated of Tis21 (Ptch1+/−/Tis21KO), relative to Ptch1 heterozygous mice in a wild-type background (Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+). Tis21-dependent mechanisms underlying the onset of Shh-type MB in GCPs during pre-neoplastic development involve a set of 188 sequences (Figure 1 Set A). Among them, about 170 encode for proteins with a known function. In particular, 13 genes belonging to a subset of set A (Figure 1) showed a change of expression that was influenced exclusively by the ablation of Tis21: Tigar, Dsc2, Padi4, Serbp1, Lnx1, Pag1, Olfr670, Mcemp1, Cldn22, Slc25a15, Pth, Pdgfd and Cxcl3.

The validation of some of these genes has already been performed by quantitative real-time PCR (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a).

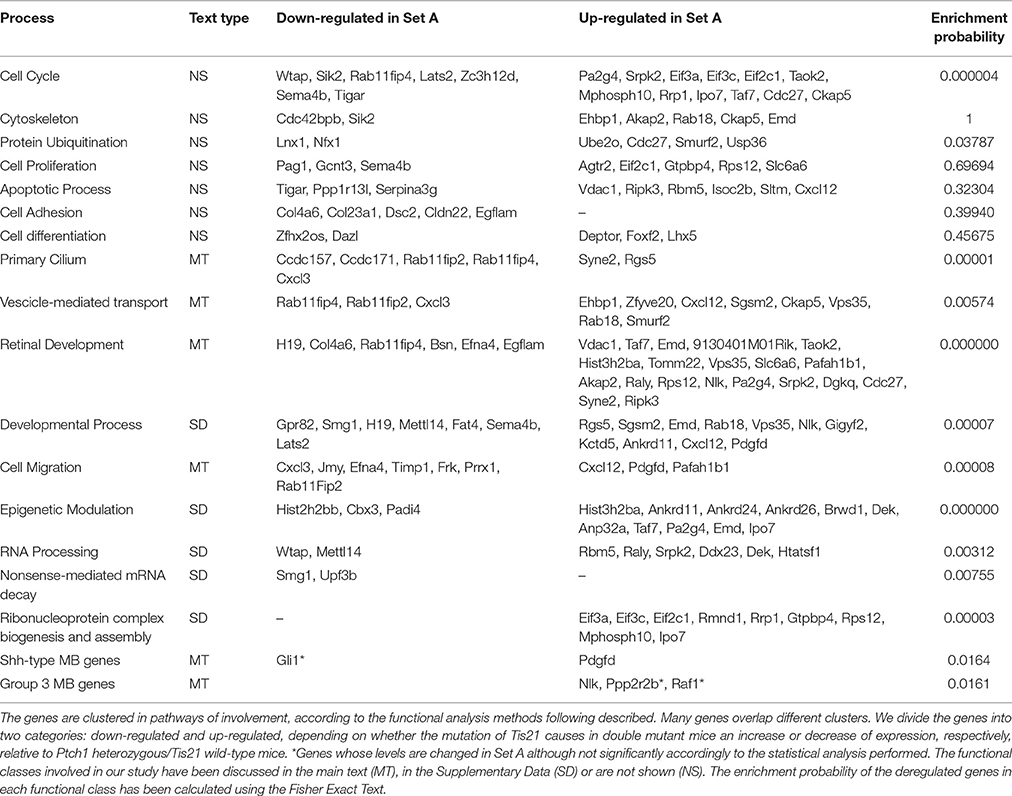

Deregulated genes in our pre-neoplastic model mainly belong to developmental pathways that affect different cellular processes such as cell cycle regulation, proliferation, cell adhesion, cytoskeleton remodeling, apoptosis, survival and differentiation (Table 1). In particular, genes belonging to developmental signaling cascades, differentially expressed in our Shh-deregulated model, depend on the Ptch1 mutation contribution as inferred by set B vs. set D data analysis (Figure 2). As well known in the literature, in fact, developmental cascades, when deregulated, acquire oncogenic effect. Neuronal development and tumorigenesis rely on cell communication via identical signaling pathways, resulting in a complex signaling network that creates a breeding ground for tumor-initiating events (Peifer and Polakis, 2000; Schwartz and Ginsberg, 2002; Clark et al., 2007; Katoh, 2007; Neth et al., 2007; Guo and Wang, 2009; Rodini et al., 2010; Mimeault and Batra, 2011; Roussel and Hatten, 2011; Akhurst and Hata, 2012; Manoranjan et al., 2012).

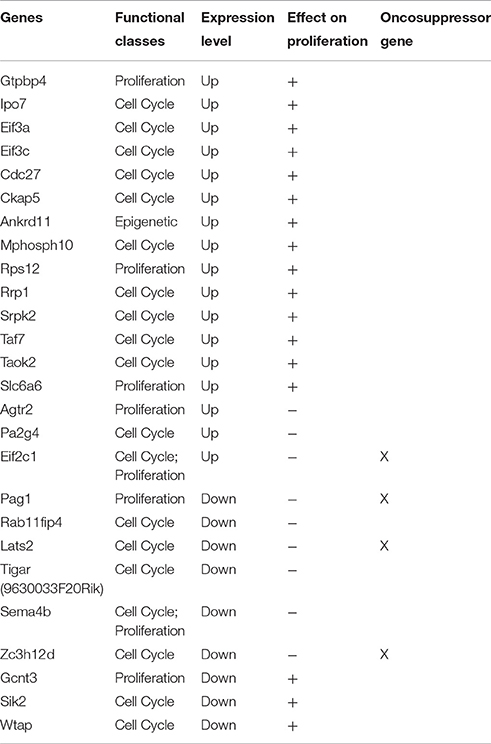

Table 1. The most informative deregulated genes belonging to the Set A and associated with the influence of Tis21 gene in background Ptch1 heterozygous (GCPs at P7).

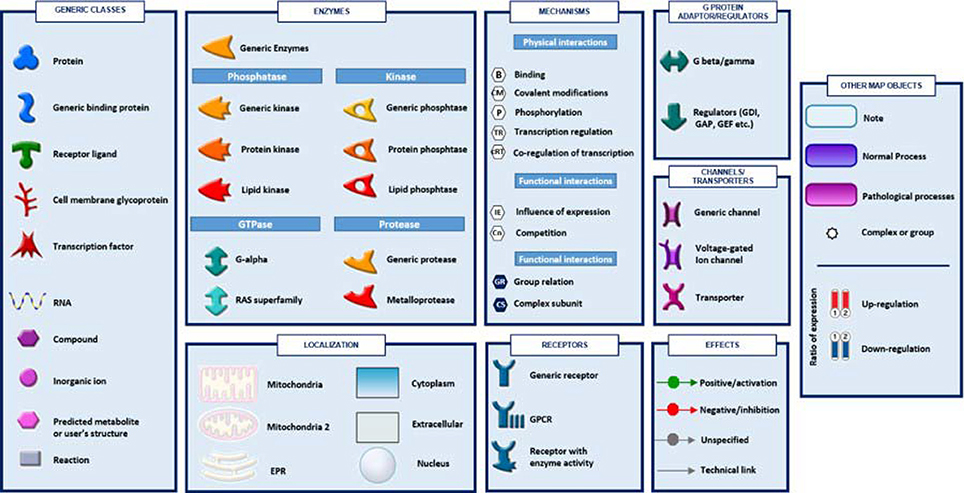

Figure 2. A molecular overview of our Shh-deregulated mouse model, characterized by the genetic disruption of hedgehog signaling resulting from a heterozygous mutation in the negative regulators Ptch1, whose effects are enhanced by the homozygous deletion of the Tis21 tumor suppressor gene. The figure shows the proteins mainly involved in neural developmental pathways, encoded by the differentially expressed genes of set B and set D and shown in their subcellular compartments. Each differentially expressed pathway object is labeled with a thermometer that indicates the gene expression changes: downward thermometers have a blue color and indicate down-regulated expression, whereas upward thermometers have a red color and indicate up-regulated expression. The thermometer number 1 is related to the pairwise comparison Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+ vs. wild type Set B, while the thermometer number 2 is related to the pairwise comparison Ptch1+/−/Tis21−/− vs. wild type Set D. Signaling cross-talks between developmental pathways involved in pre-neoplastic GCPs development are initiated by different growth factors and cytokines, the most part of which interacts with G-protein coupled receptors. This is supported by a strong up-regulation of many members of heterotrimeric G-proteins, their target molecules and regulators (data not shown in figure). Among those reported in literature as involved in MB (Roussel and Hatten, 2011), developmental signaling pathways appear to be up-reregulated in our experimental data, according to the far fewer percentages of negative signature genes (Chen et al., 2013) and the over-representation of WNT and axonal guidance genes present in human MB Shh-type (Northcott et al., 2011). Interestingly, a β-Catenin-Gli1 balanced interaction has been recently reported to regulate Shh-driven MB tumor growth in Ptch1 heterozygous mice in vitro (Zinke et al., 2015), while Sox7, a transcription factor that is known to reduce Wnt/β-Catenin stimulated transcription in a dose-dependent manner (Takash et al., 2001), is up-regulated in Set B and Tis21 ablation enhances its up-regulation in Set D (data not shown in figure). Furthermore, Smo-dependent non-canonical Shh pathways (Jenkins, 2009), which have been reported to modulate cytoskeleton-dependent processes and fluctuation of Ca2+ through the plasma membrane in mammalian neurons (Brennan et al., 2012) and suggested in possible association with MB (Briscoe and Therond, 2013), are put in light here for the first time as related to the MB Shh-type mouse model. Evidences of a deregulated Slit-Robo pathway, which is implicated in neuronal migration (Wong et al., 2001; Marillat et al., 2004), are present in our data with the up-regulation of the axon guidance receptor Robo4. The ligand of Robo4, Slit2, has been linked to the inhibition of MB cell invasion (Werbowetski-Ogilvie et al., 2006). Proteins belonging to the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of GCPs cell cycle regulators [24] have their genes up-regulated in our model, in particular a number of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and some constituents of the SCF (Skip1, Cullin1, F-box)-E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Among them, a substrate recognition component of the SCF-type E3 ubiquitin ligase, the F-box protein Fbw7, which has been linked to a premature migration of GCPs in conditional Fbw7-knockout mice [30]. An up-regulation genes coding for proteins involved in palmitoylation (i.e., HHAT) and transport of Shh (i.e., DISP1) is noticed in in Set D, where Ptch1 sterol-sensing domain seems to control Smoothened activity through Ptch1 vesicular trafficking [34]. Retinoblastoma-associated protein (Rb), as well as its downstream effectors E2F3 and E2F5, has its correspondent gene up-regulated in set D, where the deregulation of the Rb/E2F tumor suppressor complex in MB Shh-driven has been already associated to the E2F1-dependent regulation of lipogenic enzymes in primary cerebellar granule neuron precursors (Bhatia et al., 2011). Figure 4 below shows the set of symbols whereby network objects and interactions between objects are indicated in this figure.

At the same time, Tis21 ablation is responsible for the delayed migration of pre-neoplastic precursors outside the EGL, which corresponds to a delayed cell differentiation and represents the key step for MB Shh-type formation. In fact, where GCPs proliferate for a prolonged period in EGL, they became the target of neoplastic transforming insults (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a,b).

Moreover, we have noticed evidence for the involvement of the primary cilium in our GCPs pre-neoplastic model, mainly in Set B but also in Set A data (Figure 3), and also evidence of Smo-dependent non-canonical Shh pathways. A link between Shh signaling at primary cilium and clathrin-mediated endocytotic trafficking/cytoskeletal remodeling will also be discussed.

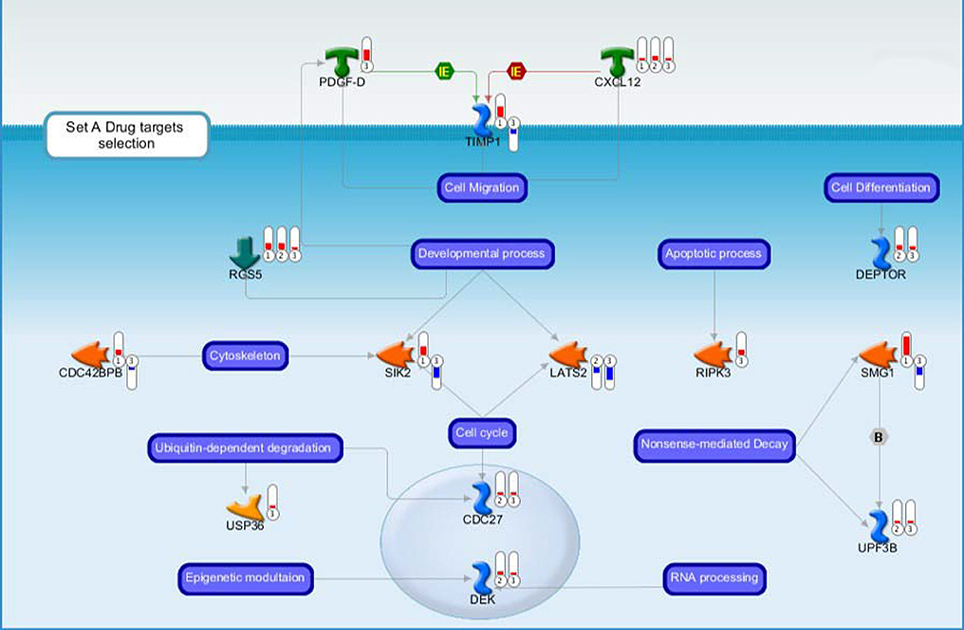

Figure 3. Drug targets belonging to the Set A discussed in the main text. Each gene product is labeled with a thermometer indicating the gene expression changes: downward thermometers have a blue color showing down-regulated expression, whereas upward thermometers have a red color showing up-regulated expression. The most part of the figure objects are deregulated also in other two pair comparisons. For this reason, the thermometer number 1 is related to the pairwise comparison Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+ vs. wild type or Set B, the thermometer number 2 is related to the pairwise comparison Ptch1+/−/Tis21−/− vs. wild type or Set D, while the thermometer number 3 is related to the pairwise comparison Ptch1+/−/Tis21KO vs. Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+ or Set A. See Figure 4 for the set of symbols, objects and interactions between objects indicated in this figure.

Figure 4. The figure shows symbols, objects and interactions between objects indicated in Figures 2, 3.

Another observation is related to the mitogen role of Shh signaling, not only in the developing cerebellum but also in the neuronal tube and overall in the retinal cell specification. In fact, a large number of deregulated genes in our Set A are also involved in the delayed differentiation of retinal cell types. Notably, it has been previously shown a parallelism between MB and retinal development; in fact, the analysis of cell populations in MB-derived from GCPs (particularly the group 3) suggests the occurrence of a potential aberrant trans-lineage differentiation into retinal neuronal precursors (Kool et al., 2008; Hooper et al., 2014). Here, given the large number of genes comprised in set A that is deregulated during the retinal cell development, we want to focus our attention on the timing of exit from the cell cycle, a crucial step in retinal cell development and differentiation, which is under the influence of Shh signaling, as it occurs in the development of MB Shh-type (Dyer, 2004). These considerations will be taken into account for a parallel comparison with our model data.

Finally, a fine regulation at RNA processing, ribosomes and vesicle trafficking level but also an epigenetic modulation were noticed in set A deregulated genes (Table 1). In the following paragraphs, we will discuss the most informative deregulated coding genes belonging to the set A according to their functional clusters (Figure 3 and Table 1), the most of which overlap different clusters. Among them, there is a large number of already known genes as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. In doing this, we have also taken into account the genes which are deregulated in consequence of the Ptch1 heterozygous.

Primary cilia are sensory non-motile microtubule-based organelles (Lee and Gleeson, 2010) protruding from the surface of GCPs in the EGL at early post-natal stages (Del Cerro and Snider, 1972), whose requirement for Shh-induced expansion and cerebellar development has been proved using mutants of genes involved in the ciliary formation and maintenance (Chizhikov et al., 2007; Spassky et al., 2008). Among them, the genetic ablation of primary cilia by removing Kif3a (which encodes the microtubule plus end-directed kinesin motor 3A protein), blocked MB formation driven by a constitutively active Smoothened protein (Han et al., 2009). Therefore, Kif3a down-regulation blocks MB Shh-type formation in a primary cilia-dependent manner; moreover, its activity is not required for GCPs differentiation (Chizhikov et al., 2007). In our model, we observe that Kif3a is up-regulated in Ptch1 heterozygous mice, irrespective of the presence or absence of Tis21, which is therefore not involved in the Kif3a-dependent phenotype (Figure 2). This is consistent with the finding that Kif3a is required for the proliferation of the GCPs (Chizhikov et al., 2007) and with our observation that Tis21 in cerebellum regulates the migration of the GCPs but not their proliferation, while the opposite occurs for Ptch1.

Nevertheless, in our model, several genes encoding for the coiled-coil domain containing proteins are deregulated in Set A, and thus are dependent on Tis21, i.e., Ccdc157 and Ccdc171 (Table 1). One-fourth of the deregulated genes in Set A corresponds to coiled-coils proteins (data not shown), whose highly versatile protein folding motif is related to different biological processes, from subcellular infrastructure maintenance to trafficking control (Burkhard et al., 2001; Rose et al., 2005) and cilia-related (McClintock et al., 2008; Munro, 2011). A coiled-coil containing protein is also Rab11 family-interacting protein 4 encoded by Rab11fip4 (Muto et al., 2006, 2007), whose role in our model will be discussed more in detail in other paragraphs together with the functional product of Rab11fip2, and their wide implication in Shh signaling at primary cilium as a protein involved in microtubule-based vesicle trafficking. Another protein, Nesprin-2 encoded by Syne2, is known to mediate centrosome migration and is essential for early ciliogenesis and formation of the primary cilia by the interaction with the coiled-coil domain of Meckelin protein (Dawe et al., 2009). Notably, Ccdc157, Ccdc171, Rab11fip2, and Rab11fip4 are significantly down-regulated in Set A, while Syne2 is up-regulated. Also a novel repressor of hedgehog signaling, whose gene Rgs5 is up-regulated in set A, has been proven to be present with Smo in primary cilia (Mahoney et al., 2013). This would suggest that Tis21-dependent tumorigenesis in a (proliferation-independent) way involves ciliogenesis. This latter may be also enhanced by Syne2 after Tis21 ablation.

Evidences of direct involvement of Shh signaling on the increase of Ca2+ levels (Ca2+ spikes) have been shown at the primary cilium of chicken embryonic spinal neurons. In this system has been observed that Shh (a recombinant N-terminal molecule) may recruit second messengers (i.e., calcium—Ca2+—and inositol triphosphate) by a non-canonical pathway, through the activation of the Smoothened protein, which translocates to the cilium and becomes activated by phosphorylation at its C-terminal from a G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (Riobo et al., 2006; Belgacem and Borodinsky, 2011; Brennan et al., 2012). Belgacem and Borodinsky (2011) proposed a model in which the primary cilium acts as a subcellular compartment for Shh signaling allowing the spatiotemporal integration of the second messengers through a Smoothened-dependent recruitment of Gi proteins and Phospholipase C that in turn increases inositol triphosphate levels. The opening of Inositol triphosphate receptors-operated stores and the following activation of Transient receptor potential cation channel 1 (Trpc1) results in an increased Ca2+ spike activity. This model could fit with our data (Figure 3) in which Plc-gamma2, Ip3r3, Trpc1, Trpc2, and Trpc3 are up-regulated in Ptch1 heterozygous mice (but independently from Tis21). Notably, this is the first time that such regulation is observed directly in a mouse model of Shh-type MB, as it had been previously only suggested (Briscoe and Therond, 2013). Furthermore, the authors suggested that the Smoothened-dependent Ca2+ spike activity is necessary for Shh-induced differentiation of spinal postmitotic neuron. Moreover, the role of second messenger signaling in the regulation of cerebellar granule cell migration has been studied in different mouse models (Komuro et al., 2015), which highlighted the direct evidence of the role of Ca2+ signaling in granule cell turning and modulation of their migration rate. The revision of these studies, performed by Komuro et al. (2015), suggested the role of Ca2+ as potential therapeutic target for some deficits in granule cell migration since its downstream effectors control the assembly and disassembly of cytoskeletal elements.

In the last years, the discovery of the role of the primary cilium in Shh signaling captured the attention of the scientific community, leading to test a large number of molecules that modulate SMO cilial translocation acting on different therapeutic potential targets in different types of cancer among which MB (Amakye et al., 2013). Loss of cilia in cancer has been suggested to be responsible for an insensitivity of cancer cells to environmental repressive signals, based in part on derangement of cell cycle checkpoints governed by cilia and centrosomes (Plotnikova et al., 2008). The importance of the role of cilia in Shh-driven medulloblastoma allografts derived from Ptch1+/−P53−/− mice has been shown using a Shh antagonist, i.e., arsenic trioxide (a therapeutic agent for acute promyelocytic leukemia), which inhibits the growth of tumor through the prevention of Shh ciliary accumulation and the reduction of the stability of the Gli2 transcriptional effector (Kim et al., 2010).

Other genes deregulated in Set A are involved in endocytic trafficking clathrin-dependent (Figure 5), and a certain number is related to cytoskeletal remodeling and primary cilium that could be very interesting for their implications for target therapy.

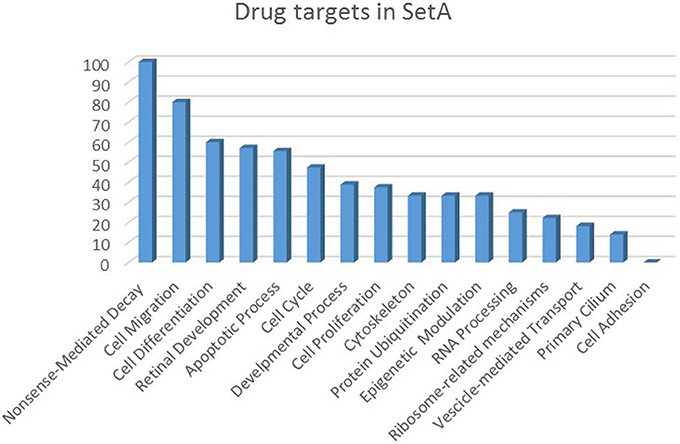

Figure 5. Drug targets percentage per functional class of the Set A deregulated genes. The drug targets identified in Set A are showed as percentage with respect to the functional classes to which they belong.

The clathrin-dependent endocytic mechanism is a receptor-mediated endocytosis type, which involves clathrin-coated vesicles, early endosomes, microtubule-based vesicle trafficking, lysosomes and recycling transport vesicles in its pathway (Le Roy and Wrana, 2005). Evidences of a deregulated clathrin-mediated endocytosis pattern have been reported for MB group 4 during early human neurogenesis (Hooper et al., 2014), and detected in our Set B (data not shown) as well as in Set A, where a large number of deregulated genes belongs to this signaling: Rab11fip4 (Horgan and McCaffrey, 2009), Ehbp1 (Guilherme et al., 2004), Rab11fip2 (Fan et al., 2004), Zfyve20 (de Renzis et al., 2002; Naslavsky et al., 2004), Cxcl12 (Fan et al., 2004; Teicher and Fricker, 2010; Zhu et al., 2012), Sgsm2 (Yang et al., 2007), Ckap5 (Foraker et al., 2012), Vps35 (Foraker et al., 2012), and Rab18 (Foraker et al., 2012).

Rab11fip4 is known to interact with Rab11 (a Rab GTPase involved in the regulation of intracellular membrane trafficking), which in turn interacts with Rab-coupling protein, a protein involved in the formation of lamellipodia, which facilitates invasive cancer cell migration (Kelly et al., 2012). Ehbp1 gene product is involved in actin reorganization coupled to endocytosis clathrin-mediated (Guilherme et al., 2004). Zfyve20 is known to regulate structure, sorting, endocytic/recycling pathway of the early endosomal compartment by the interaction with Rab4 and Rab5 (de Renzis et al., 2002; Naslavsky et al., 2004). Vps35, among other genes involved in intracellular membrane trafficking, is deregulated in Set A. It encodes for the vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 35, a component of the trimeric cargo-selective retromer complex, required for the efficient endosome-to-Golgi recycling of many membrane proteins among which Wntless. It is also known to regulate endosomal tubule dynamics (Harbour et al., 2010; Berwick and Harvey, 2014). The oncogene Rab18 is required for normal ER structure and the regulation of endocytic traffic (Lütcke et al., 1994; Gerondopoulos et al., 2014). This Rab GTPasi is also known as a MB antigen (Behrends et al., 2003). Interestingly, Rab18 has been localized at lipid droplets (LDs) level (Martin et al., 2005), and its overexpression causes close apposition of LDs to membrane cisternae connected to the rough ER (LD-associated membrane or LAM) (Ozeki et al., 2005). Indeed, de novo lipid synthesis has been found in certain highly proliferative and aggressive tumors such as MB Shh-type, suggesting that the Shh-E2F1-FASN axis regulating de novo lipid synthesis in cancers could be used as therapeutic target in hedgehog-dependent tumors (Bhatia et al., 2011). Remarkably, Rab11fip2 encodes for a Rab11 family-interacting protein 2, which directly interacts with the actin-based myosin Vb motor protein regulating Cxcr2 recycling and receptor-mediated chemotaxis; hence, Rab11fip2 links Rab11 to molecular motor proteins and cell migration (Jones et al., 2006; Horgan and McCaffrey, 2009). Moreover, the passage of the internalized Cxcr2 through the Rab11-recycling system appears to have a key role in the physiological response to a chemokine that follows to the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles; in fact, Rab11 family-interacting protein 2 can form a complex with AP-2 that is a major clathrin adaptor complex in cells (Cullis et al., 2002; Fan et al., 2004; Le Roy and Wrana, 2005). Furthermore, the Rab11 involvement into the regulation of vesicular trafficking during primary ciliogenesis has been already put in light (Knödler et al., 2010; Hsiao et al., 2012). A consequence of the above findings, indicating an interaction between Cxcr2 and the clathrin pathway, is that, since Cxcl3 binds the Cxcr2 receptor (Zlotnik et al., 2006), we can infer that this chemokine receptor-mediated chemotaxis mechanism is clathrin-dependent and linked through Rab11fip2 to the primary cilium, in which the Shh signaling takes part. Other evidence of an involvement of Rab11fips and Shh signaling derives from Rab11fip4 (see the retina development section). This protein seems to be involved in the regulation of the membrane trafficking system through interaction with other small GTPases, among which could be Ras-related protein Rab-23, and in the negative regulation of Shh signaling at the primary cilium (Muto et al., 2007; Hsiao et al., 2012).

All this points to an important link between Shh signaling, operating through the primary cilium, and GCPs impaired cell migration, through a clathrin-Cxcl3-Cxcr2-mediated chemotaxis and microtubule-based endocytic vesicle recycling trafficking. Furthermore, the findings of a study about the role of endosomes around mother centriole appendages, and their Rab11-dependent recycling activity that requires centrosome-associated endosome proteins (Hehnly et al., 2012), seem to be in line with our data (see drug target section). Interestingly, they showed that (i) the appendages of the mother centriole and recycling endosomes are in intimate contact, as first evidence for a novel centrosome-anchored molecular pathway and regulation of endosome recycling; (ii) there is a structural association between the endosome and the centrosome with new and unexpected implications for recycling endosome functions, such us that one related to cilia formation; (iii) it is also possible that Rab11, and other endosome-associated molecules bound to the centrosome, may play dual roles in endosome and centrosome function (Hehnly et al., 2012).

In mice, retinal development occurs between E11.5 and P8, as uncommitted neuroblasts leave the cell cycle and commit to retinal cell fates (Mu et al., 2001). Thanks to mice models, it is known that aberrant proliferation during the development of the neural tube, of cerebellum and retina, leads to embryonal and early postnatal tumors (Dyer, 2004). The potent mitogen Shh positively controls the proliferation of their neuronal precursor cells (Martí and Bovolenta, 2002). In particular, Shh signaling plays a pivotal role in regulating the proliferation of retinal progenitor cells (RPCs) and the differentiation of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) during vertebrate retinal development, acting in a cell-specific manner; namely, in mouse Shh is required as positive regulator of RPCs proliferation and as negative regulator of RGCs production, by inhibiting cell-cycle exit (Wang et al., 2005; Wallace, 2008).

A further molecular target which may be responsible for the regulation of retinal cell proliferation and hence for cancer cell proliferation was suggested to be Rb; in fact, the levels of Rb protein appear critical for the development of retinal tumors (Sicinski et al., 1995). The rationale for this is that Rb, when active, inhibits the cycle at the G1 checkpoint, prior to cell differentiation, whereas its inactivation, exerted by phosphorylation from cyclinD1/CDK4, is known to start the cell cycle progression. Thus, high levels of Rb may be more difficult to inactivate and vice-versa, thus critically linking the Rb-dependent developmental regulation of proliferation during neurogenesis to cancer cell proliferation for certain types of tissues (Sicinski et al., 1995). Indeed, in our model we observe that in GCPs heterozygous for Ptch1 (set B: Ptch1+/−/Tis21+/+ vs. Ptch1+/+/Tis21+/+) cyclin D1 expression does not change while Rb does increase. This suggests that in Shh-driven neoplastic GCPs the increase of Rb protein is compensatory.

In the case of MB, a parallel between developmental neurobiology and oncology was suggested for the proliferating progenitor cells of the retina and cerebellar granule neurons, where the failure to exit the cell cycle leads to aberrant cell proliferation during development in mice (Romer and Curran, 2004). Notably, MB-types Cluster D and E (also referred to as groups 4 and 3, respectively) have been found to be marked by a deregulated expression of retinal photoreceptor genes suggesting a distinct origin (i.e., non-cerebellar) from stem cells during the embryonic development, with respect to MB Shh-type in human (Kool et al., 2008).

In this context, concerning the contribution of Tis21 deletion to the MB development, in Set A we noticed a great number of deregulated genes that have been previously described as involved in retinal development. This comparison could be useful to suggest some common mechanisms related to the progenitor cells cell-cycle exit failure. A consistent subset of Set A genes has been previously described as being involved in cellular expression patterns of mouse early retinal development; these gene were previously recognized by analyzing the outer retinal neuroblastic layer, which in early developmental stages consists almost entirely of mitotic progenitor cells: Vdac1, Taf7, Emd, 9130401M01Rik, Taok2, Hist3h2ba, Tomm22, Vps35, H19, Slc6a6, Pafah1b1, Akap2, Raly, Rps12, Nlk, Pa2g4 and Srpk2 (Blackshaw et al., 2004). These genes are all up-regulated in Set A except for H19. Furthermore, a number of other genes that were identified in other studies as being involved in retinal development, are down-regulated in set A: Col4a6 (Bai et al., 2009), Rab11fip4 (Muto et al., 2007), Bsn (Dick et al., 2003), Efna4 (Marcus et al., 1996; Poliakov et al., 2004; Triplett and Feldheim, 2012), Egflam (whose product is also known as Pikachurin) (Omori et al., 2012); conversely, other retinal genes up-regulated in set A are: Dgkq (Pilz et al., 1995), Cdc27 (Leung et al., 2008), Syne2 (Yu et al., 2011), Slc6a6 (Vinnakota et al., 1997; Warskulat et al., 2007), Ripk3 (Trichonas et al., 2010).

The genes listed above belong to different functional clusters, and some of them will be discussed more in detail in their paragraph of pertinence. Interestingly, the mouse Rab11fip4, whose product regulates the Rab GTPases and is predominantly expressed in the developing neural tissues, among which retina, acts as regulator of RPCs cell-cycle exit and their subsequent differentiation (Muto et al., 2007). Rab11fip4 seems to be involved in the regulation of membrane trafficking system through interaction with other small GTPases and in the negative regulation of Shh signaling (Muto et al., 2007). Moreover, the Syne2 gene product is known to mediate nuclear migration during mammalian retinal development connecting the nucleus with dynein/dynactin and kinesin proteins (Yu et al., 2011).

This comparison is in line with the evidence that progenitors from the developing cerebral cortex, cerebellum and retina share a common expression program, suggesting a common evolutionary origin of the different progenitors cells (Livesey et al., 2004), and implying a possible common differentiation program. Our data suggest that this developmental process, possibly at the steps of migration and differentiation, is regulated by Tis21.

The migration of the GCPs is known to be induced by responses to local environmental cues. However, the alterations of migratory behavior may also depend on intrinsic programs (Komuro et al., 2013). In our study, we observed in Set A the differential expression of a great number of genes belonging to migration, cell adhesion and differentiation mechanisms. Among the genes implicated in migration seven are down-regulated after ablation of Tis21 in Shh-activated background, namely, Cxcl3, Jmy, Efna4, Timp1, Frk, Prrx1, and Rab11fip2, and three are up-regulated: Cxcl12, Pdgfd, and Pafah1b.

Cxcl3 is a chemokine known to have chemotactic activity for neutrophils (Wuyts et al., 1999). Chemotaxis but also angiogenesis seems to be activated by the interaction with its receptor (Addison et al., 2000; Zlotnik et al., 2006). In our previously published data, Cxcl3 has been identified as a gene whose transcription is regulated positively by Tis21 (which directly associates to the Cxcl3 promoter), suggesting that the evident role played in vivo by Tis21 as inducer of the migration of the GCPs out of the EGL might occur through its functional product; this implies Cxcl3 as a new pharmacological target for medulloblastoma therapy, also considering that MB lesions were reduced using this chemokine as treatment (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a,b). Recently, the anti-cancer role of this chemokine has also been recognized for non-small lung cancer, mediated by the activity of interleukin-27 (Airoldi et al., 2015). Jmy, a junction mediating and regulatory protein, is known to induce cell motility by promoting actin assembly and regulating cadherins in the cytoplasm; in DNA damage conditions it undergoes nuclear accumulation, where acts as p53-cofactor promoting apoptosis (Shikama et al., 1999; Coutts et al., 2007; Zuchero et al., 2009). Together, these findings suggest that the ability of Jmy to regulate actin and cadherin, by coordinating cell motility with the p53 response, could underlie a common pathway (Coutts et al., 2009). Furthermore, actin assembly has been found to regulate the nuclear import of Jmy in response to DNA damage (Zuchero et al., 2012). Thus, an abnormal activity and/or localization of Jmy could contribute to tumor invasion, thus making this gene as a potential tumor therapeutic target (Wang, 2010). In theory, the down-regulation of Jmy may contribute to enhance the rate of MB in our mouse model, possibly by controlling the migration of the GCPs as shown for Cxcl3. Regarding Efna4, this gene encodes for the EphrinA4 protein that has been linked with the migration of neuronal cells during development (Poliakov et al., 2004). A recent study showed that EphrinA4 and the Ephrin type-B receptor 4 are almost exclusively expressed in Shh MBs, while other Ephrins are expressed in non–Shh MBs; furthermore, a strategy of overexpression and silencing, applied specifically to EphrinB1, showed its ability to control the migration of MB cell lines (McKinney et al., 2015). Further evidence of the migration-promoting activity of EphrinA4 has been observed in human glioma cells, where it acts by accelerating a canonical FGFR signaling pathway (Fukai et al., 2008). Timp1 protein product is a metalloproteinase inhibitor known to be involved in cell adhesion and migration of human neural stem cells (hNSCs). In fact, through its cell surface receptor CD63, TIMP-1 activates β1 integrin, FAK (focal adhesion kinase) and the PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase) signal transduction pathway, resulting in the migration of hNSCs (Lee et al., 2014). Due to its chemoattractant properties, TIMP-1 has been identified in the same study as a therapeutic target for human glioma. The Frk gene product is a Src kinase known as Tyrosine-protein kinase FRK, which controls the migration and invasion of human glioma cells by regulating JNK/c-Jun signaling (Zhou et al., 2012). Moreover, the Tyrosine-protein kinase FRK acts as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer by regulating the stability of PTEN, as the loss of Rak (i.e., Frk) induced tumorigenicity in immortalized normal mammary epithelial cells (Yim et al., 2009). In mouse brain, Pten is known to be expressed starting at approximately postnatal day 0 (Lachyankar et al., 2000) and has also been correlated with the regulation of neuronal precursor cell migration (Li et al., 2002). In Set B Pten is up-regulated. The paired-related homeobox transcription factor 1, which is encoded by Prrx1, is an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) inducer in embryos, where this process is required for the formation of tissues for which cells originate far from their final destination (Ocaña et al., 2012). EMT is modified and exploited by cancer cells for metastatic dissemination and also in cancer cells. In particular, the loss of Prrx1 has been related to the ability of cancer cells to acquire tumor-initiating abilities concomitantly with stem cells properties (Ocaña et al., 2012). Furthermore, paired-related homeobox transcription factor 1 has been found to promote tenascin-C–dependent fibroblast migration when its expression was induced by Focal adhesion kinase 1 (McKean et al., 2003). Fak is up-regulated in both Set B and Set D. Very interesting is the down-regulation of Rab11fip2, whose role in the endocytic recycling pathway has been linked to cell migration (Jones et al., 2006) as previously discussed (Section Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis Mechanisms, Microtubule-Based Vesicle Recycling and Intracellular Membrane Trafficking).

Among the genes up-regulated in Set A related to migration there is Cxcl12, which encodes for a deeply studied chemokine involved in different mechanisms in cancer development and metastatic invasion (Duda et al., 2011; Hattermann and Mentlein, 2013), but also described as involved in the migration of neuronal cells through both its receptor, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 and Atypical chemokine receptor 3 (Tiveron and Cremer, 2008; Memi et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013). Cxcl12 appears to exert an action opposite to Cxcl3, as it promotes the localization of the GCPs to the EGL by chemoattraction, being released from meninges (Klein et al., 2001; Zhu et al., 2002). Thus, the upregulation of Cxcl12, consequent to the ablation of Tis21, synergizes with the downregulation of Cxcl3 in preventing the migration of the GCPs from the EGL. Notably, the chemoattraction of cerebellar granule cells by Cxcl12, whose receptor C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 is coupled to a G protein, is selectively inhibited by the soluble EphB receptor; this inhibition is blocked by a truncated PDZ-RGS3 lacking the RGS domain, which activates the G-proteins. Therefore, this points to the existence of a pathway connecting B ephrins and Cxcl12 to the regulation of G protein–coupled chemoattraction, and leads to a model for regulation of migration in cerebellar development (Lu et al., 2001). In this regard, in our model (Set A) we have detected not only a down-regulation of Efna4, which is a cell surface GPI-bound ligand for Eph receptors, but also the up-regulation of a regulator of heterotrimeric G protein signaling, i.e., Rgs5. Therefore, in our model the decrease of Cxcl3 and Efna4 and the increase of Cxcl12 after ablation of Tis21 in Ptch1 heterozygous mice would synergize in impairing the migration of GCPs from the EGL. As mentioned above, the increase of Cxcl12 in the Tis21-null EGL GCPs would prevent their migration by chemoattraction (Zhu et al., 2002). Moreover, the PDGFR pathway members have been recently studied in correlations with MB Shh-driven and MB cell migration, and an upregulation of PDGFRA (receptor for PDGF-A), PDGF-D (ligand for PDGFRB) and Cxcl12 has been observed in Shh-type MB (vs. non Shh MBs). In particular, the activation of the PDGFR pathway has been shown to activate the Cxcl12 receptor (i.e., CXCR4, via inhibition of GRK6) and thus cell migration (Yuan et al., 2013). A relevant caveat of that study is that the direction of cell migration, relative to the EGL, was not assessed, having the analysis been conducted only in vitro (Yuan et al., 2013). In our model, we noticed an up-regulation of Pdgfd and Cxcl12 genes in Set A, while both Pdgfra and Pdgfrb and also Cxcl12 are up-regulated in Set B and D (see Figure 3). This indicates that the heterozygosity of Ptch1 is in itself a condition inducing the expression of both the Cxcr4 and Pdgfr pathways, and that the additional ablation of Tis21 further enhances their activation. Finally, Pafah1b1, up-regulated in Set A, encodes for Lis1, a microtubule regulator that is required for correct neuronal migration during development (Hippenmeyer et al., 2010; Escamez et al., 2012).

The transcriptional reprogramming of the epigenetic patterns is among the causes of tumorigenesis. Nowadays, the epigenetic regulation of transcription and genome organization in MB Shh-type pathogenesis is extensively studied (Batora et al., 2014; Hovestadt et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2014). We have previously provided a first functional genomic analysis of epigenetically regulated genes or interacting proteins for our mouse model Tis21 KO, identified in background either Ptch1 heterozygous or wild-type (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012b). We also have recently shown that the Tis21 protein binds to histone deacetylases (HDAC1/4/9) in GCPs, where they are required for the Tis21-dependent inhibition of cyclin D1 expression (Micheli et al., 2016). In the present analysis, a great number of genes encoding proteins involved in epigenetic regulation appear to be deregulated in Set A (three down-regulated and 12 up-regulated). They mostly belong to the category of the Histone modification rather than to the Chromatin remodeling one (Table 2), which categories are described in (Arrowsmith et al., 2012; Plass et al., 2013). Our data are in line with those previously published highlighting a great number of deregulated or mutated histone modifiers involved in medulloblastoma (Northcott et al., 2012) and their importance as oncogenes or as tumor suppressors (Cohen et al., 2011). Furthermore, we highlight also the deregulation of five Histone modifier Regulators, up-regulated in Set A, namely: Emd (Berk et al., 2013), Anp32a (Seo et al., 2001; Fan et al., 2006; Kular et al., 2009), Taf7 (Gegonne et al., 2001, 2013; Kloet et al., 2012), Pag2g4 (Zhang et al., 2003), Ipo7 (Jäkel et al., 1999; Mühlhäusser et al., 2001). A detailed description of Set A genes involved in epigenetic modulation is presented in Supplementary Data, at section “Epigenetic modulation.”

The increasing recognition of the heterogeneity of molecular basis underlying cancer allows the identification and development of molecularly targeted agents and their transfer to the patients (Rask-Andersen et al., 2011; Saletta et al., 2014). Here we provide a drug target identification through the genomic analysis of deregulated MB Shh-type Tis21 knockout-dependent genes in Set A and, where possible, the identification of potentially druggable targets (Figure 3, Tables 3–5), performed using the methods described in the appropriate section. This analysis has given as a result 20 primary, 31 secondary, 53 druggable targets and 18 gene targets among Set A elements (Tables 3–6). Their distribution within the functional classes is showed in Figure 5. and the putative drug targets identified in SetA, here discussed, are shown in Figure 3.

Table 3. A list containing the direct targets and their drugs obtained using MetaCore™ (i.e., ATP1A1) and Cortellis™ db.

Table 5. A drug-target interactions list and the correspondent source of information obtained using the Search Drug-Target Interactions tool on DGIdb, where a drug-gene interaction is a known interaction between a known drug compound and a target gene.

Table 6. A sub-list of Set A genes with the correspondent selected druggable gene category and source of information obtained using the Search Druggable Gene Categories tool on DGIdb, where a druggable gene category is a group of genes that are thought to be potentially druggable by various methods of prediction.

Among the Set A genes showing a change of expression influenced exclusively by the ablation of Tis21, there is Pdgfd that has been discussed in developmental (see Supplemtary Data) and migration processes as up-regulated gene. Since the overactivity of PDGF signaling can drive tumorigenesis (Pietras et al., 2003), and since PDGF-D in particular has been found to be a potent transforming and angiogenic growth factor (Li et al., 2003) highly expressed in Shh-type medulloblastoma (Yuan et al., 2013), we propose targeting PDGF-D as therapeutic strategy for medulloblastoma Shh-type, as already studied in other tumors (Heldin, 2013). Another very interesting drug target could be the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related kinase Smg1, which here has been discussed in developmental and nonsense-mediated decay processes (Supplementary Material) as down-regulated in Set A (up-regulated in Set D). This protein seems to act antagonistically with mTOR signaling (González-Estévez et al., 2012; Du et al., 2014), and this is in functional synergy with the up-regulation in Set A of Deptor, which negatively regulates mTOR signaling (Beauchamp and Platanias, 2013). Also Deptor is one of the druggable target identified in our study. Taken together, these findings seem to support the importance of mTOR pathway and its upstream PDGF signaling in the pathogenesis of medulloblastoma (Mohan et al., 2012).

Other two druggable targets are regulators of cell cycle and developmental processes: Sik2 and Lats2. The functional product of Sik2 is localized at the centrosome where its absence leads to a delay of G1/S transition (Ahmed et al., 2010), while Lats2 encodes for a centrosomal protein (a serin threonin kinase) whose loss leads to centrosome fragmentation (Yabuta et al., 2007), also involved in the regulation of cell cycle G1/S checkpoint, for its relevance to MB tumorigenesis due to its influence in the reduction of expression of cyclin-D1 and N-CoR (Park et al., 2012; Lit et al., 2013). The deregulation of centrosome and cilia biogenesis have been already described in different human diseases, in particular, in cancer where a derangement of cell cycle checkpoints is governed by cilia and centrosomes (Plotnikova et al., 2008; Nigg and Raff, 2009; Bettencourt-Dias et al., 2011). In addition to that, Sik2 has been characterized as negative regulator of Hippo signaling in Drosophila (Wehr et al., 2013). In our data, other two regulators of Hippo signaling appear to be down-regulated after ablation of Tis21, Lats2, and Fat4 that we discuss for their role in the developmental process (Supplementary Data); both act also as tumor suppressors. This evidence supports the involvement of Hippo signaling (Roussel and Hatten, 2011) and centrosome assembly in the pathogenesis of MB.

Another putative drug target belonging to developmental processes, Rgs5, encodes for an endogenous repressor of Shh signaling and has been proposed in a recent study as potential therapeutic target in Hh-mediated diseases. In fact, it was shown that (i) Rgs5 inhibits the Shh-mediated signaling by activating the GTP-bound Gαi downstream of Smo and (ii) a physical complex between Rgs5 with Smo is present in primary cilia (Mahoney et al., 2013).

The apoptosis is not the only form of cellular death in which the deregulated genes in Set A are involved. In fact, the Ripk3 functional product, a receptor-interacting protein kinase 3, has been reported to contribute to both apoptotic and necroptotic cell death, depending on target availability (Cook et al., 2014; Vanden Berghe et al., 2014). Since many anti-cancer drugs are inducers of apoptosis, the induction of RIP3-dependent necrosis is an attractive strategy to circumvent apoptosis resistance of cancer cells (Moriwaki and Chan, 2013) that is currently under investigation (Moriwaki et al., 2015). As Ripk3 expression is induced after knockout of Tis21 in Shh-activated background, we may hypothesize that Ripk3 plays in our model a tumor suppressor role.

The therapeutic advantage of targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system has already being successfully investigated with proteasomal inhibitors in Shh-type MB with in vivo preclinical studies (Ohshima-Hosoyama et al., 2011) and in a preliminary study with personalized targeted therapy for pediatric brain tumors among which MB (Wolff et al., 2012). However, the targeting of specific enzymes regulating the ubiquitylation process, e.g., SKP2, a SCF ubiquitin ligase, up-regulated in Set D (Figure 3), has been recently proposed as a more specific approach than the previous one (Hede et al., 2014). Two genes belonging to the ubiquitin-dependent degradation processes are up-regulated in Set A and have been identified in this study as putative drug target: Ups36 and Cdc27. Usp36, encoding for a deubiquitinating enzyme (Quesada et al., 2004), has been detected as overexpresed in human ovarian cancer compared to normal ovaries (Li et al., 2008). An Usp36 homolog, recently detected in Drosophila stem cells, has been linked to the deubiquitylation of histone H2B and to the silencing of key differentiation genes, including genes target of Notch (Buszczak et al., 2009). Whereas the anaphase-promoting complex component Cdc27 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase able to control cell cycle progression at the G1 to S transition, and also to induce the non-proteolytic disassembly of the spindle checkpoint during mitosis (Jin et al., 2008; Manchado et al., 2010; Pawar et al., 2010). For these reasons, Cdc27 functional product has been identified as a molecular target of the curcumin-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in Shh-type MB (Lee and Langhans, 2012). The therapeutic properties of this natural substance were already shown in Shh-driven MB models, highlighting its ability to inhibit the Shh signaling, to reduce the level of β-catenin and to inhibit HDAC4 (Elamin et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011). Thus, the up-regulation of Cdc27 after ablation of Tis21 may be a tumorigenic factor.

Of interest as drug target among the genes belonging to the migration processes is Timp1. Its signal trasduction pathway results in the migration of hNSCs, showing chemoattractant properties and being identified in the same study as a therapeutic target for human glioma (Lee et al., 2014). Here we suggest the same prospective use of Timp1 in MB Shh-type.

The Cdc42bpb produces a Rho GTPase activated serine/threonine kinase, which, by regulating the (non-muscle) cytoskeletal actomyosin, influences cell shape and promotes motility and migration (Tan et al., 2008, 2011), thus acting also as a key regulator of tumor cell invasion. Cdc42bpb is therefore an interesting drug target (Heikkila et al., 2011; Unbekandt et al., 2014). It's down-regulation in our Set A data is in line with the GCPs migration failure, consistently with the deregulation of others migration regulators discussed above.

Genes involved in the RNA processing are Smg1 and Upf3b, respectively down- and up-regulated in Set A. Interestingly, both genes encode for proteins involved in alternative splicing (AS) coupled with Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) mechanism by which NMD controls transcript abundance by regulating AS; in fact, the SURF complex, which includes the SMG1–UPF1–eRF1–eRF3 proteins, forms a bridge between the ribosome and the downstream exon-junction complex (EJC) associated with UPF3b and UPF2 (Chamieh et al., 2008; McIlwain et al., 2010). Moreover, Smg1 has been showed to be involved in the predisposition to tumor formation and inflammation in Smg1 heterozygous mice; this mouse model presents elevated basal tissue and serum cytokine levels—indicating low-level inflammation—and can progress to chronic inflammation or enhanced cancer development. Therefore, this is a model of inflammation-enhanced cancer development (Roberts et al., 2013), also suggesting that Smg1 is a tumor suppressor (Du et al., 2014). To our knowledge, the possibility to target inflammation through Smg1 has never been applied to medulloblastoma until now. Furthermore, in our data Il1b, for example, is up-regulated in Set D and B (See Figure 2); also Cxcl12 is up-regulated in Set D, B, and also in Set A, as mentioned previously, while Cxcl3 is down-regulated in Set A. It is also worth noting the existence of an anticoagulant inhibitor of CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, the Tinzaparin, as well as other heparinoids that have been studied in brest cancer models for their heparinoid-mediated inhibition of chemotaxis activity (Harvey et al., 2007; Mellor et al., 2007). As Cxcl12 favors the localization of the GCPs to the EGL by chemoattraction, an inhibitor of Cxcl12 might achieve an opposite effect, similar to the promigratory effect exerted by Cxcl3.

During cerebellar development, Shh is expressed in Purkinje cells and regulates the proliferation of GCPs acting as mitogen (Dahmane and Ruiz i Altaba, 1999; Wallace, 1999; Wechsler-Reya and Scott, 1999). GPCs undergo a prolonged mitotic activity in the EGL during the early postnatal period in the mouse. After this intense proliferative phase, around the second postnatal week in mouse, GPCs exit the cell cycle and migrate radially to the IGL, along the Bergmann glia. During this inward migration, differentiation of post-mitotic GPCs takes place, allowing the mature granule neurons to expand the IGL, where they extend dendrites (Dyer, 2004; Rodini et al., 2010; Wang and Wechsler-Reya, 2014). As a consequence of a hyperactivation of the Shh pathway occurring in the Ptch1+/− MB mouse model, the prolonged mitotic activity of GCPs makes them potential targets for transforming insults, leading to MB (Wang and Zoghbi, 2001).

Mutations in Ptch1 occur in sporadic human MB and promote the tumor in Ptch1 heterozygous mouse models at a rate of approximately 8% within 12 weeks of age and up to 30% between 12 and 25 weeks of age (Goodrich et al., 1997). As previously described (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a), the ablation of Tis21 in our mouse model strikingly enhances, from 25 to 80%, the incidence of MB spontaneously occurring in Ptch1 heterozygous mice. We observe that the whole balance between division, differentiation and death is disrupted in Ptch1 heterozygous GCPs lacking Tis21, leading to an increase in tumor incidence (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a). In particular, Tis21 seems to act on the timing of migration of GPCs from EGL to IGL, causing an extended period of localization in the proliferative region, decrease of differentiation and increase of apoptosis (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a,b). These cellular changes are mirrored in gene expression changes occurring in Set A, shown in Table 1. We observe that the most significant enrichments of genes whose expression is altered in Set A, fall in the functional pathways of developmental signaling, retinal development, cell migration, epigenetic modulation, and primary cilium-related activities. We will summarize some consideration on these functions and also about the ubiquitin-dependent degradation (Table 1), in relation to the possible drug targets available.

We have shown that no change in the proliferation of GCPs occurs after ablation of Tis21 (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a). Moreover, in a recent study, we have demonstrated that the proliferation of the GCPs is not ruled by Tis21 but by the family-related gene Btg1 (Ceccarelli et al., 2015). Indeed, if we analyze the type of expression changes occurring in the whole array of genes of Set A that either directly or indirectly regulate the proliferation and/or the cell cycle of the GCPs (Table 7) we find that there is upregulation as well downregulation of genes that affect either positively or negatively this process, evidently resulting in no net change of proliferation of the GCPs. Nonetheless, the defect of migration of the Tis21-null GCPs forces them to stay a longer period in the EGL under the control of Shh influence, possibly leading to different types of alterations in cell division, including the control of centrosome assembly (see below).

Table 7. The table shows a sub-set of Set A deregulated genes which can influence proliferation in a direct or indirect manner.

We have shown a link between the Shh signaling, operating through the primary cilium, and the impairment of cell migration, i.e., the main phenotype observed in Ptch+/−/Tis21KO mice [17]. In fact, the primary cilium, as mentioned above, is a sensory non-motile microtubule-based organelle which acts as a subcellular compartment for Shh signaling through a Smoothened-dependent recruitment of Gi proteins (Belgacem and Borodinsky, 2011). These include the Rab11 family, which impacts on cell motility, and whose components Fip4 and Fip2 are down-regulated in Set A. Remarkably, Rab11Fip2 interacts with the myosin Vb motor protein (Horgan and McCaffrey, 2009) that regulates the recycling of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 2, the receptor of Cxcl3, and the receptor-mediated chemotaxis, as confirmed by Raman et al. (2014). As we have pointed out previously, Cxcl3 induces the migration of GCPs out of the EGL and its decrease in Set A is at the origin of the increase of tumorigenesis in Tis21 KO model (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012a). All this points to a link between the decrease of the Cxcl3-Cxcr2 function in Set A and the clathrin-mediated chemotaxis and microtubule-based migration. Such type of reasoning could be extended to the whole set of coiled coil molecules present in the cilium whose expression is altered in Set A, further suggesting that the ablation of Tis21 in Set A could trigger an impairment of GCPs migration acting at more than one level.

Another interesting connection is with the cilium-based GTPase Rab11Fip4; in fact, since Rab11Fip4 induces Gli3 (Muto et al., 2007) which is a negative regulator of Shh signaling, the ablation of Tis21, by down-regulating Rab11fip4, may enhance the Shh pathway activity, thus conferring more penetrance to the Shh stimulus. Moreover, the presence of cilia is in itself necessary for the development of Shh-type MB, and the formation of cilia might be enhanced by the upregulation in Set A of Syne2 (Chizhikov et al., 2007).

We also noticed several deregulated genes in Set A related to an evident deregulation of centrosome assembly (Akap2, Syne2, Ckap5, Sik2, Emd, and Lats2). Since the basal bodies, microtubule-based structures, are required for the formation of cilia (also non-motile ones) but also for the pericentriolar material at the core of the centrosome (Nigg and Raff, 2009), our results could confirm the previously reported evidences of a deregulation of centrosome and cilia biogenesis that have been described in different types of cancer, where a derangement of cell cycle checkpoints is governed by cilia and centrosomes (Plotnikova et al., 2008; Nigg and Raff, 2009; Bettencourt-Dias et al., 2011).

In reference to set B (comparison of Ptch1 heterozygous mice vs. wild-type, thus without involvement of Tis21) our attention was captured by mechanisms that could regulate cell cycle machinery in a primary cilia-dependent fashion. These are suggestive of a possible involvement of Smo-dependent non-canonical Shh-pathways, namely concerning our data showing for the first time that Plc-gamma2, Ip3r3, Trpc1, Trpc2, and Trpc3 are up-regulated in Ptch1 heterozygous mice. These genes belong to the described Smo-dependent non-canonical Shh pathways (Figure 3) that have been reported to modulate cytoskeleton-dependent processes (Jenkins, 2009) and Ca2+ spikes (Brennan et al., 2012). In particular, a model in which the subcellular compartment (i.e., primary cilium) for Shh signaling allows the spatiotemporal integration of second messengers has been proposed (Belgacem and Borodinsky, 2011), and the role of Ca2+ signaling in granule cell turning and in modulation of their migration rate has been suggested as potential therapeutic target for some deficits in granule cell migration, since its downstream effectors control the assembly and disassembly of cytoskeletal elements (Komuro et al., 2015).

The presence of the key components of the Shh pathway in cilia has been assessed, as well as the anterograde and retrograde traffic regulating its signaling (Goetz and Anderson, 2010). We have taken in consideration the role of primary cilia in GCPs, where their presence has been assessed in the EGL at early post-natal stages (Del Cerro and Snider, 1972), as well as their requirement for Shh-induced expansion and cerebellar development (Chizhikov et al., 2007; Spassky et al., 2008). Exploring this scenario, in our MB mouse model we have highlighted some other cilia-related protein targets modified in Set B—but not in Set A—such as Tctex-1, identified as a novel “checkpoint” for G1-S transition controlling ciliary resorption, cell cycle S-phase entry and fate of neural progenitors of developing neocortex (Li et al., 2011; Sung and Li, 2011).

An intriguing observation concerns the fact that three genes in Set A whose expression is significantly modified - namely, Nlk, Raf1, and Ppp2r2b—are markers for group 3 medulloblastoma (Kool et al., 2008; Gibson et al., 2010; Northcott et al., 2011, 2012c; Taylor et al., 2012; Hooper et al., 2014). Moreover, Nlk is among the genes of Set A modified in retinal development, and it has been suggested that cerebellar and retinal progenitor cells have common evolutionary origin [76]. It is also worth noting that, according to references (Kool et al., 2008; Hooper et al., 2014), among the markers for group 3 MB there are many genes involved in retinal development; in our Set A many genes as well are involved in this process, Nlk being common. Additionally, in Set A there are at least two genes whose expression is modified, Gli1 and Pdgfd, which are markers of Shh-type medulloblastoma (Kool et al., 2008; Gibson et al., 2010; Northcott et al., 2011, 2012c; Taylor et al., 2012; Hooper et al., 2014). Hence, the ablation of Tis21 causes changes in the Ptch1 heterozygous Shh-type model of two Shh-type MB marker genes (increased expression) and of three group 3 MB marker genes (Table 1). As a whole, these data may suggest the possibility that the ablation of Tis21, by altering the expression of important Shh marker genes such Pdgfd and Gli1, may increase the penetrance of the Shh-type tumor phenotype, but also the possibility of a shift of the Shh phenotype toward the group 3 MB. A possible shift toward group 3, associated with retinal development control, may underlie the intriguing novel concept that the inactivation of a gene—in this case Tis21, which is known to be required for the terminal differentiation of neural stem cells (Micheli et al., 2015)—may favor in Shh-activated GCPs a lineage shift toward other neural cell types involved in group 3 MB onset. Further analyses will be necessary to clarify this possibility.

A further correlation concerns the up-regulation of Deptor in Set A: this gene has been remarkably associated with reduced differentiation and increase of regenerative potential of pluripotent stem cells (Agrawal et al., 2014). Deptor functional product also inhibits the TOR pathway, whose activation results in a more penetrant phenotype in Shh-type MB, with enhanced survival of cancer stem cells (Beauchamp and Platanias, 2013). Thus, we can further suppose that the ablation of Tis21 enhances the stem cell character of the Shh–activated GCPs as a preliminary step to possible lineage shifts.

The most significant enrichment in Set A is probably observed for genes that regulate transcription epigenetically. We have previously performed a functional genomic analysis where we identified more than 30 genes altered by the Tis21 KO genotype relative to Tis21 wild-type, (in background either Ptch1 wild-type or heterozygous) and involved in epigenetic control, being regulated by DNA methylation or histone deacetylation, or being able to associate with HDAC1 or HDAC4 (Farioli-Vecchioli et al., 2012b). We limited the present analysis within Set A to genes acting as histone modifier and their regulators or involved in chromatin remodeling, finding several of the first class and one of the second. Among them, is relevant PadI4, which by demethylating histones may act as a tumor suppressor (Tanikawa et al., 2012); thus, its down-regulation in Set A could enhance tumorigenesis. Remarkable is also the series of histone modification editors ANKRDs, whose genes are down-regulated in SetA. Among the chromatin modifiers, we find Dek, up-regulated in Set A and also up-regulated in group 4 MB (Hooper et al., 2014), which is a known oncogene that can confer stem cell-like qualities and is thus potentially enhancing the probability of cancer (Privette Vinnedge et al., 2013). Altogether, the alteration in Set A of genes involved in histone modification and chromatin remodeling fits with the idea that the ablation of Tis21 may reduce in the Tis21-null GCPs the restraint toward a lineage shift, as exposed in the previous section.

The role of Tis21 in the cell proliferation control has been recently associated in human cells to RNA deadenylation, by which it influences mRNA poly(A) tail shortening (Stupfler et al., 2016). Nevertheless, in Set A we detect the deregulation of genes related to AS or to NMD, but not to mRNA deadenylation.

This is a very interesting topic for therapy, that will need preclinical experimental studies for evaluation. Among the Set A genes that could be targeted by a drug, are worth mentioning: (i) the inhibitor of Pdgfd (ligand for Pdgfrb), since the activation of the PDGFR pathway has been shown to activate the Cxcl12 receptor; (ii) the possibility to enhance the activity of the tumor suppressor phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related kinase Smg1, whose ablation favors inflammation and cancer development. This could also be obtained by negatively targeting mTOR, which is antagonistic to Smg1 (possibly also by enhancing Deptor activity, which negatively regulates mTOR signaling). Moreover, as mentioned above, the intracerebellar administration of Cxcl3 functional product, by controlling the timing of migration of pre-neoplastic pGCPS, may have therapeutic effects that still need to be fully tested in vivo. Since these genes are deregulated in a Shh-type MB whose frequency is enhanced by Tis21 ablation, and since Tis21 has been shown to be down-regulated in human MBs (mainly Shh-type), it is plausible a benefit using Cxcl3 in MB therapy of at least the Shh-type.

GG analyzed the data; SC, FT designed the experiments; GG, FT wrote the paper; MC, LM carried out experimental work; GG, FT, and SC are responsible for accuracy and integrity of any part of the work.

This work was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance (Project FaReBio) to FT, the CNR Project DSB.AD004.094 to FT, and by the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research grant CTN01_00177_817708 to SC. MC is recipient of fellowships from the Italian Foundation for Cancer Research (FIRC; year 2014) and from Fondazione Santa Lucia (year 2015), while GG is recipient of the fellowship from the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research grant CTN01_00177_817708 (2014–2015).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

However, a patent was filed by the National Research Council on the possible use of the chemokine Cxcl3 in medulloblastoma therapy. No financial exploitation of the patent has occurred.

We acknowledge Cristina Calì, Alfia Corsino, Maria Patrizia D'Angelo, and Francesco Marino for their administrative and technical support. We also appreciate the contribution of Maria Guarnaccia to the first release of the manuscript and figures.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2016.00449/full#supplementary-material

Addison, C. L., Daniel, T. O., Burdick, M. D., Liu, H., Ehlert, J. E., Xue, Y. Y., et al. (2000). The CXC chemokine receptor 2, CXCR2, is the putative receptor for ELR+ CXC chemokine-induced angiogenic activity. J. Immunol. 165, 5269–5277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5269

Agrawal, P., Reynolds, J., Chew, S., Lamba, D. A., and Hughes, R. E. (2014). DEPTOR is a stemness factor that regulates pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 31818–31826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.565838

Ahmed, A. A., Lu, Z., Jennings, N. B., Etemadmoghadam, D., Capalbo, L., Jacamo, R. O., et al. (2010). SIK2 is a centrosome kinase required for bipolar mitotic spindle formation that provides a potential target for therapy in ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell 18, 109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.06.018

Airoldi, I., Tupone, M. G., Esposito, S., Russo, M. V., Barbarito, G., Cipollone, G., et al. (2015). Interleukin-27 re-educates intratumoral myeloid cells and down-regulates stemness genes in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 6, 3694–3708. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2797

Akhurst, R. J., and Hata, A. (2012). Targeting the TGFβ signalling pathway in disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 790–811. doi: 10.1038/nrd3810

Amakye, D., Jagani, Z., and Dorsch, M. (2013). Unraveling the therapeutic potential of the Hedgehog pathway in cancer. Nat. Med. 19, 1410–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.3389

Arney, K. L., and Fisher, A. G. (2004). Epigenetic aspects of differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 117(Pt 19), 4355–4363. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01390

Arrowsmith, C. H., Bountra, C., Fish, P. V., Lee, K., and Schapira, M. (2012). Epigenetic protein families: a new frontier for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 384–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd3674

Bai, S. W., Herrera-Abreu, M. T., Rohn, J. L., Racine, V., Tajadura, V., Suryavanshi, N., et al. (2011). Identification and characterization of a set of conserved and new regulators of cytoskeletal organization, cell morphology and migration. BMC Biol. 9:54. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-54

Bai, X., Dilworth, D. J., Weng, Y. C., and Gould, D. B. (2009). Developmental distribution of collagen IV isoforms and relevance to ocular diseases. Matrix Biol. 28, 194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.02.004

Batora, N. V., Sturm, D., Jones, D. T., Kool, M., Pfister, S. M., and Northcott, P. A. (2014). Transitioning from genotypes to epigenotypes: why the time has come for medulloblastoma epigenomics. Neuroscience 264, 171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.030

Beauchamp, E. M., and Platanias, L. C. (2013). The evolution of the TOR pathway and its role in cancer. Oncogene 32, 3923–3932. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.567

Behrends, U., Schneider, I., Rössler, S., Frauenknecht, H., Golbeck, A., Lechner, B., et al. (2003). Novel tumor antigens identified by autologous antibody screening of childhood medulloblastoma cDNA libraries. Int. J. Cancer 106, 244–251. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11208

Belgacem, Y. H., and Borodinsky, L. N. (2011). Sonic hedgehog signaling is decoded by calcium spike activity in the developing spinal cord. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 4482–4487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018217108

Berk, J. M., Tifft, K. E., and Wilson, K. L. (2013). The nuclear envelope LEM-domain protein emerin. Nucleus 4, 298–314. doi: 10.4161/nucl.25751

Berwick, D. C., and Harvey, K. (2014). The regulation and deregulation of Wnt signaling by PARK genes in health and disease. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 3–12. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjt037

Bettencourt-Dias, M., Hildebrandt, F., Pellman, D., Woods, G., and Godinho, S. A. (2011). Centrosomes and cilia in human disease. Trends Genet. 27, 307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.004

Bhatia, B., Hsieh, M., Kenney, A. M., and Nahlé, Z. (2011). Mitogenic Sonic hedgehog signaling drives E2F1-dependent lipogenesis in progenitor cells and medulloblastoma. Oncogene 30, 410–422. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.454

Blackshaw, S., Harpavat, S., Trimarchi, J., Cai, L., Huang, H., Kuo, W. P., et al. (2004). Genomic analysis of mouse retinal development. PLoS Biol. 2:E247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020247

Blake, J. A., Bult, C. J., Eppig, J. T., Kadin, J. A., and Richardson, J. E. (2014). The Mouse Genome Database: integration of and access to knowledge about the laboratory mouse. Nucleic Acids Res 42, D810–D817. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1225

Bolton, E. E., Wang, Y. L., Thiessen, P. A., and Bryant, S. H. (2010). PubChem: integrated platform of small molecules and biological activities. Annu. Rep. Comput. Chem. 4, 217–241. doi: 10.1016/S1574-1400(08)00012-1

Brennan, D., Chen, X., Cheng, L., Mahoney, M., and Riobo, N. A. (2012). Noncanonical Hedgehog signaling. Vitam. Horm. 88, 55–72. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394622-5.00003-1

Briscoe, J., and Thérond, P. P. (2013). The mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling and its roles in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 416–429. doi: 10.1038/nrm3598