95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

STUDY PROTOCOL article

Front. Pediatr. , 31 March 2025

Sec. Pediatric Obesity

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2025.1450324

This article is part of the Research Topic Novel Approaches to Diet, Exercise, and Drugs in Childhood Obesity and Metabolic Diseases View all 5 articles

Alessandra Vincenti1*

Alessandra Vincenti1* Valeria Calcaterra2,3

Valeria Calcaterra2,3 Sara Santero1

Sara Santero1 Giulia Viroli1

Giulia Viroli1 Ilaria Di Napoli1

Ilaria Di Napoli1 Ginevra Biino4

Ginevra Biino4 Luca Daconto5

Luca Daconto5 Mariaclaudia Cusumano5

Mariaclaudia Cusumano5 Gianvincenzo Zuccotti3,6

Gianvincenzo Zuccotti3,6 Hellas Cena1,7

Hellas Cena1,7

Introduction: Paediatric obesity has been described by the World Health Organization as one of the most serious health challenges of the 21st century. Over the past four decades, the number of children and adolescents with obesity has increased between 10 and 12-fold worldwide.

Methods: Childhood obesity is a complex and multifactorial outcome which can be attributed to factors such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, lifestyle and eating habits. Beside personal-children-related factors, maternal (education, food knowledge, income) and environmental ones (food environment's features and accessibility) have been proven but their influences are still worth discussion. The cross-sectional study of the “FACILITY: feeding the family—the intergenerational approach to fight obesity” project aims at estimating children prevalence of overweight and obesity and assessing the impacts of lifestyle and of socio-economic-cultural and environmental factors on overweight and obesity.

Results: Due to the current importance of developing multidisciplinary mother-child centred prevention programs, FACILITY cross-sectional study will investigate maternal and child socio-cultural, economic, environmental, health and lifestyle-related risk factors for the development of obesity.

Discussion: The knowledge gained will provide the basis to develop a “primordial prevention program” to early tackle childhood obesity.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier (NCT06179381).

The Global Strategy for Women's, Children's, and Adolescents' Health (2016–2030) (1) plays a central role in the objective 3, Health and Well-being of the Agenda for Sustainable Development (2) for a future world in which every woman, child, and adolescent realises their rights to physical and mental health and well-being, in every setting (3). Obesity is defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that poses a risk to health, due to an energy imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure (4, 5). The reasons for this imbalance are complex and multifactorial (6). Health and nutritional status, lifestyle habits, biological features, environmental and socio-economic factors are nested within the family context, which in turn is nested within the community and the wider socio-geographical and cultural background (7).

Paediatric obesity has been described by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century (8). Over the past four decades, the number of children and adolescents with obesity has increased between 10 and 12-fold worldwide (9–11), with a rising prevalence among socially disadvantaged groups from low socio-economic backgrounds (11–13). In Italy, the prevalence of overweight and obesity for children aged 6–9 years is 29.8%, with the percentage of overweight and obesity around 20.4% and 9.4%, respectively (4).

Obesity prevention is recognized as the most feasible option for curbing the paediatric obesity epidemic (14). Most childhood obesity prevention programs have focused on school-aged children and have not proven so far to be effective in reversing the rising rates of childhood obesity (7). Indeed, by primary school entry, about 1 in 5 school-aged children were affected by obesity (15), suggesting that a prime opportunity to prevent childhood obesity has been missed (7). Thus, the prevention program should start very early, during and even before pregnancy and be shaped on mother-child dyads (16).

Maternal health is critical for healthy child growth and development (17). Indeed, maternal factors [i.e., Body Mass Index (BMI)], combined with an unhealthy family background (i.e., unhealthy eating habits and sedentary behaviour), strongly determine the lifestyle and nutrition behaviour of the child, predisposing him/her to the development of overweight or obesity (7, 18–20).

Along with the previously mentioned factors, socio-economic status (SES) has also been identified as a determinant for later obesity (11). Indeed, children with lower SES families have a steeper weight gain trajectory from birth with higher risk of obesity in adulthood (12, 21). Furthermore, children in poverty are more likely to become adults with lower SES and less wealth to pass on to future generations, in a vicious cycle, clearly acknowledging that obesity is increasingly related to poverty and is likely to be passed onto subsequent generations (22). Moreover, factors related to the socio-spatial environment play a key role in obesity (16, 23–25). For instance, the lack of healthy food availability, affordability and accessibility (e.g., food desert) has been positively linked to obesity. High neighbourhood walkability has been found to be associated with decreased prevalence of overweight and obesity, as well as the proximity to recreational facilities, parks, playgrounds, etc. have all been reported to be facilitators of physical activity (22, 26).

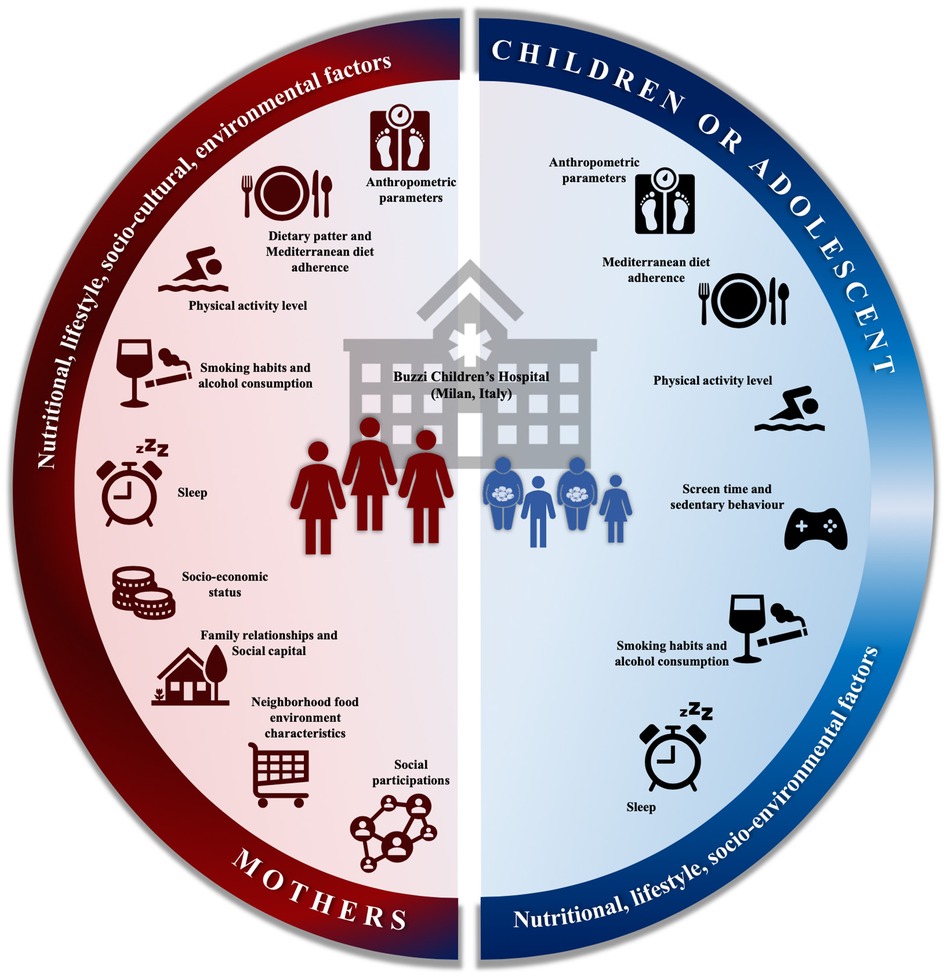

The overall aim of the FACILITY (feeding the aamily—the intergenerational approach to fight obesity) project is to identify determinants for early onset of childhood obesity considering both maternal and children risk factors in a sample of mother-child dyads attending a paediatric outpatient clinic of the Buzzi Children's Hospital in Milan, Italy. More in detail, the cross-sectional study aims at (i) estimating the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the target population, thus, providing updated estimates in the Milan area, a useful data for the planning of public health interventions; (ii) assessing the impacts of lifestyle and of socio-economic-cultural and environmental factors on overweight and obesity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Graphical representation of FACILITY (feeding the family—the intergenerational approach to fight obesity) cross-sectional study. Understanding health and socio-economic-cultural maternal-child risk factors will enable the development of more effective public health policies for the prevention of childhood obesity to be drawn up in the future, according to the specific cultural and health needs of the target population.

To address FACILITY's purposes, 269 mother-child dyads will be consecutively enrolled at the paediatric outpatient clinic of the Buzzi Children's Hospital in Milan, Italy. The enrollment will last from February 2024 until December 2025.

Eligible dyads according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria will be involved in the study.

- Inclusion criteria:

- For mothers: (i) age ≥18 years old, (ii) admission to the Department of Paediatrics, Buzzi Children's Hospital, (iii) ability to sign the informed consent.

- For children/adolescents: (i) age between 2 and 18 years old, (ii) admission to the Department of Paediatrics, Buzzi Children's Hospital, (iii) informed consent signed by parents/local guardians.

- Exclusion criteria:

- For mothers: (i) inability to understand the Italian and English language, (ii) refusal to sign the informed consent.

- For children/adolescents: (i) presence of endocrine disorders (i.e., hypothyroidism, hypercortisolism, growth hormone deficiency), central nervous system damage (i.e., hypothalamic-pituitary damage because of surgery or trauma), genetic diseases either monogenic (i.e., leptin deficiency, MC4R mutation) or pleiotropic genetic syndromes (Prader-Willi, Bardet-Biedl), (ii) informed consent not written and signed by parents/local guardians.

Moreover, if mothers return to the paediatric outpatient clinic with another child, the latter will also be enrolled if the inclusion criteria of the study are met. Written informed consent will be obtained from the parent or legal guardians. Variables will be collected by a trained research team (clinicians, registered dietitians, paediatricians, biologists).

A full list of the variables collected in the cross-sectional study is reported in Table 1. The clinical research team will collect the information of participants by consulting the patient's electronic/paper medical records and through validated questionnaires and structured interviews involving mothers at the enrollment. Structured interview characteristics are reported in Supplementary Table S1.

Socio-demographic features will be collected with a structured interview. In detail, mother's age, marital status (marry/cohabitant, divorced/separated, widow, single), ethnicity (Caucasian, Black, Medioriental, Asiatic, Hispanic), nationality, education level (none, elementary, middle school, high school, degree), number of people in the household, number of children, number of years in Italy (if not Italian), residential address.

Socio-economic and socio-cultural characteristics will be collected through structured interviews. Information on household income, job/work and housing status (surface; owned, rented, sub-rented, social housing, guest, other) will be collected to detect socio-economic status.

Family relationships will be derived from the Child-Parent relationship scale-Short Form (CPRS-SF), a 15-item questionnaire assessing mothers' perception of their relationship with their son or daughter (46, 47). The Personal Social Capital Scale (PSCS-8) short form will be used to assess maternal durable and trustworthy social connections (48). Maternal social participation will be investigated through a structured interview to explore type (i.e., religious, recreational, cultural and, political) and frequency of activities.

Environmental factors that may influence nutrition, physical activity and lifestyle will be considered through the collection of geo-data on the characteristics of the food environment (e.g., the built environment, proximity to recreational/sport facilities, parks) and the transport infrastructure (e.g., walkability) (35, 49).

Maternal and children/adolescent medical history will be explored through a structured interview (i.e., medical issues which includes all diseases and illnesses currently being treated and those which have had any residual effects on the mother and children/adolescent's health, medication history, surgical history and family medical history with potential indicators of predisposition to disease).

Anthropometric measures of mothers will be collected using standardised procedures (27–29), weight (kg) will be measured with a calibrated weighing scale wearing underpants only (accuracy ± 100 g), height (cm) by a fixed stadiometer with a vertical backboard and a moveable headboard (accuracy ± 1 mm) and waist circumference (cm) will be measured with an elastic tape.

Height (cm) and weight (kg) will be collected also for children/adolescents. Briefly, standing height will be measured as previously described and according to standard procedures (28, 29). Recumbent length will be assessed for children who still are unable to stand up (29). Body weight of unclothed children/adolescents will be collected using a balanced weight scale (accuracy ± 100 g), following standardised procedures (29). WHO child growth standards will be used to diagnose overweight (BMI Z-score >1) or obesity (BMI Z-score ≥2) (50). Infant growth curves from the paediatric booklet will be requested to evaluate the time (year) of the adiposity rebound. The presence of an early adiposity rebound (EAR) will be identified when the lowest BMI during child growth occurs at an age <5 years old (30, 31) and children/adolescents will be categorised into early or non-early adiposity rebound (AR). Waist circumference (cm) will be collected in children/adolescents using standardised procedures (29).

For mothers, Mediterranean dietary adherence will be explored using the 9-item MEDI-LITE questionnaire (32, 33). The questionnaire investigates the frequency of consumption of nine classes of food (i) fruit, (ii) vegetables, (iii) cereal grains, (iv) legumes, (v) fish and fish products, (vi) meat and meat products, (vii) dairy products, (viii) alcohol intake, and (ix) olive oil. The score obtained from the questionnaire ranges from 0 to 18, where the highest value corresponds to the highest MD adherence (33). Moreover, a structured interview will be also used to evaluate self-perception of the current diet, to investigate any dietary restrictions (i.e., carbohydrates, fat, meat, fish, eggs, dairy, gluten, lactose) or consumption of traditional food/dishes.

For children, Mediterranean dietary adherence will be assessed with the KIDMED (Diet Quality Index for Children and Adolescents) questionnaire (34). The KIDMED is a 16-item tool used for the evaluation of consumption of fruit, fruit juice, vegetables, fish, pulses, cereals, nuts, olive oil and yoghurts or cheese. KIDMED also explores fast-foods, commercial bakery goods and pastries, sweets and candy consumption, as well as eating behaviours (i.e., skipping breakfast). In addition, for children, a structured interview of two items will assess the endorsement of any of the following binge eating symptoms (i) sneaking, hiding, or hoarding food, (ii) eating in the absence of hunger. These questions have been selected in previous trials with the aim to examine the prevalence of overeating symptoms in overweight or obesity affected children and adolescents (51–53).

Maternal physical activity will be assessed by the short form (7 items) of a validated country-language-specific questionnaire [International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ—SF)] (36). The questionnaire provides an estimate of the metabolic equivalent of task (MET-min) per week, which is calculated as follows: METs = MET level × minutes of activity × events per week. Physical activity level will be classified according to METs into sedentary (total METs <699), moderate (total METs between 700 and 2,519), and high (total METs >2,520) (37, 54).

For children aged 2–14 years old, physical activity habits will be explored through a structured interview, differentiating questions according to the different age groups (3–4 years, 5–14 years) as suggested by WHO guidelines for physical activity (38, 39).

For adolescents aged 15–17 years old, the Italian version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (IPAQ-A) will be used to investigate time spent in physical activities in different settings (i) school-related physical activity, (ii) housework, house maintenance and gardening, (iii) transportation, (iv) recreation, sport, and leisure-time physical activity (40, 41). The quantity of physical activity will be calculated by multiplying the energy expenditure required (MET) and the amount of time spent (min) in a week for each activity. Moderate intensity will be weighed in absolute terms as 4 METs, vigorous intensity defined as 8 METs and walking as 3.3 MET.

Children's sedentary screen time behaviours will be also assessed through a structured interview, differentiating the use of screens (i.e., TV, other devices such as smartphone, computer, tablet, touch screen, and game console) at home and school for both weekdays and weekends. Total screen exposure results will be compared to WHO guidelines (38, 39).

For mothers and adolescents (12–18 years old) interviews will be used to assess smoking habits and alcohol intake. Concerning smoking habits usage of traditional tobacco cigarettes (manufactured or hand-rolled cigarettes), electronic cigarettes or heated tobacco products (HTP) will be evaluated. Participants will be then categorised as follows (i) never smoker, (ii) past smoker (i.e., current non-smoker), (iii) current smoker.

According to the frequency of alcohol intake, the respondents will be segmented in three categories (i) abstainers [i.e., subjects who do not drink alcohol, zero Units of Alcohol (U.A.)], (ii) occasional drinkers (i.e., subjects who drink less than 1 U.A./week), (iii) daily drinkers (i.e., subjects who regularly drink alcohol, more than 1 U.A./week). According to the Italian “Linee Guida per una sana alimentazione” (42) 1 U.A. equals 12 g of pure alcohol contained in a small glass of red/white/rosé wine (125 ml, alcohol by volume 12%), one can of double malt beer (330 ml, ABV 4.6%), or a small shot of hard liquor (40 ml, ABV 40%).

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (43, 44) will be used to explore sleep quality of mothers. The PSQI is a 9-item questionnaire assessing 7 sub-dimensions of sleep (i.e., subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication and daytime dysfunction).

For children, sleep quality will be assessed through a structured interview regarding sleep and wake-up times, sleep regularity, average number of hours of sleep per night, difficulty falling asleep and daytime sleepiness. Results will be compared to WHO guidelines (39, 45).

Participants' data will be collected in both electronic and paper form and sent by authorised study personnel to an electronic database protected by a password. Each individual participant and their data will be identified with a unique study identification number (pseudo-anonymization of data), which will prevent any direct identification. The unique identifier will be used from that point forward on all relevant documentation. The Coordinator Centre (Laboratory of Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition) will be responsible for the data storage in a locked and secured location. Laboratory of Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition and Buzzi Children's Hospital will be responsible for data entry and quality.

In the cross-sectional study, sample size has been determined considering a prevalence of overweight and obesity in the target population of 17% and 4%, respectively (55). Considering a 95% level of confidence and 5% precision, 217 individuals for overweight and 52 for obesity prevalence estimates are required, for a total sample size of 269 mother-child dyads.

Enrolled subjects will be described with reference to all the collected variables by means of standard descriptive statistics. Prevalence of overweight and obesity will be estimated along with 95% confidence intervals. In order to assess the impacts of lifestyle and socio-economic, cultural, and environmental factors on overweight and obesity, logistic regression will be adopted. Overweight and obesity in children, as binary variables, will be the response in two separate logistic models, where socio-economic, cultural, and environmental factors, among all collected data, will be the independent variables. Indeed, performing different analyses according to the BMI status (overweight/obesity) will capture different health correlations, since the greater severity of overweight and obesity usually corresponds to an unhealthy lifestyle, and to a low SES (12, 21). Analyses will also be adjusted for potential confounders like age, sex or any other variable identifiable as such among the collected data.

Furthermore, if sample size allows, subgroups analysis by ethnicity (Caucasian or non-Caucasian) will be performed since it likely results in different cultural habits, impacting nutrition and other lifestyle factors (56, 57).

Missing data will be handled with multiple imputation.

The cross-sectional study of the FACILITY project aimed at evaluating potential risk factors associated with the onset of childhood obesity through a comprehensive analysis of maternal and children/adolescent health, lifestyle, economic, social and environmental variables.

Obesity is defined by WHO as a complex disease with physical, social and psychological dimensions, resulting in serious health and economic consequences (5, 8). Previous studies have shown positive associations between unhealthy child lifestyle, such as adherence to a Western dietary pattern, poor sleep and sedentary behaviour, and obesity development (18). However, excessive weight gain occurs across the life cycle. Indeed, children born from mothers who are overweight or obese at the time of conception have a higher risk of obesity compared to children born from mothers with normal weight, creating intergenerational cycles of obesity (12, 18, 22, 58). Family-based behavioural treatments have been identified as one of the main interventions for an effective childhood obesity prevention and treatment, underlying the importance of the family habits for the shape of child's lifestyle behaviour (59). In addition, environmental and maternal cultural influences on child's weight are unique topics, which are only recently investigated (12, 60–62). However, scientific literature often provides partial and sometimes contradictory findings regarding the association of many of the individual and socio-cultural factors on obesity (63–67). Therefore, new researches that combine different factors are needed, with a focus on family lifestyle, health, environment and socio-cultural variables (56). In this scenario, the FACILITY project aims to provide evidence on the association between individual, family and socio-economic and cultural factors, and excessive body weight during childhood and adolescence. Thus, the study may fill the gap between the interplay of social-cultural and health domains in the Italian context, since to the authors' knowledge no studies on maternal and infant socio-economic variables have been published in Italy (68–73). The cross-sectional study of the FACILITY project has numerous strengths. First, it evaluates a broad range of risk factors across socio-economic, cultural, health, and lifestyle dimensions. Second, the age range is broad (i.e., 2–18), potentially allowing the assessment of all-age children and adolescents. Often, studies focus on one specific age class, therefore the first exploratory analysis will capture the differences in risk factors manifestations. Third, it will use visual inspection of BMI-for-age plots, which is the gold standard for defining timing of AR. Also, maternal and infant anthropometric variables will be measured by qualified medical professionals.

Nevertheless, the cross-sectional phase of the FACILITY project has few limitations. First, due to the observational study design of the two study phases, a direct cause-and-effect relationship between the examined variables and overweight, obesity, and EAR can not be ascribed. Second, FACILITY focuses on mother-child dyads, excluding fathers from the analysis, although several evidence is highlighting the role of the triads for the child's development into adulthood (74, 75). Third, due to the specificity of the setting (single outpatient clinic in a North-Italian hospital), the results obtained from this study will not be generalizable to the entire Italian population. While children attending the outpatient clinic may have different health conditions and socio-economic backgrounds, it should be noted that visits are offered free of charge, which limits the participation of families with higher incomes who might prefer private healthcare settings, potentially leading to the underrepresentation of these groups. Moreover, the study will be conducted at a specific clinic, which may not reflect the diversity of healthcare settings across different regions of Italy, thus reducing the generalizability of the results to the national level.

Besides, the sampling frame may introduce a bias due to the non-random method of participant selection. Since children will be consecutively enrolled at the outpatient clinic, the sample may not be fully representative of the broader pediatric population. The recruitment method could result in a non-homogeneous distribution of age groups, as some age ranges may be more likely to attend the clinic due to specific health concerns.

Fourth, some of the outcome measures rely on parental reports and the use of structured interviews may lead to interviewer bias. Whenever possible, the authors have selected validated questionnaires, however, to date no validated tools to capture the mother's diet and her cultural influences exist. Therefore, structured interviews have been developed by the research team, which may mean that real lifestyle habits of the mothers and children would not be properly assessed due to the lack of validation of the interviews. Fifth, the authors recognize the lack of evaluation of additional potentially interesting variables correlated to childhood obesity (e.g., body composition, metabolic syndrome, food insecurity, screen time during mealtimes, family meals or shared meals).

In conclusion, the cross-sectional study of the FACILITY project aims to shed light on the intricate web of lifestyle-related, social, economic, cultural, and environmental risk factors contributing to the early onset of obesity during childhood and adolescence within mother-child dyads. The study stands poised to offer updated, comprehensive data and a potential blueprint for action to Italian policymakers and healthcare professionals, with the goal of mitigating the childhood obesity epidemic. Given the elevated incidence of obesity and unwholesome habits among vulnerable demographics, particularly women and children from underprivileged backgrounds, it becomes imperative to tailor childhood obesity prevention policies to their needs, thereby addressing the decrement in the age of obesity onset. It is also critical to adapt current Caucasian-centric prevention strategic policies to more effectively serve the Italian population, ensuring they consider the diverse social, economic, and cultural factors that influence the health of future generations. This study underscores the importance of extending the focus beyond traditional approaches, advocating for policies that reflect the nuances of ethnic diversity and their bearing on child health outcomes.

The FACILITY project encapsulates an articulate response to an urgent public health matter, proffering a multi-dimensional analysis whose extrapolation could lead to transformative public health solutions. It robustly adheres to a methodological framework capable of shedding lights on complex interactions, and the need for expanding its demographic inclusivity and enriching the dataset with information about paternal influence is admitted in the study. If carefully followed up on, these projects will improve our knowledge of the phenomena and create an even more effective approach to addressing childhood obesity. Consequently, the project anticipates offering invaluable lessons on the intergenerational dynamics at play, fostering an evidence-based foundation upon which to construct more culturally responsive and equitable public health policies.

The FACILITY study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico Territoriale Lombardia 1) on 6 November 2023 (approval code: CET 120-2023, version 3, December 06, 2023). The study will be conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines, to International Guidelines and to current Clinical Trial laws.

The study protocol was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT06179381). If modifications in the original protocol will be required, additional amendments will be demanded to the Ethic Committee. In this scenario, the approved related information will be updated on clinicaltrial.gov.

To ensure a greater scientific rigour, the authors followed the SPIRIT and STROBE-NUTR guidelines for study protocols reporting (76, 77).

The study design and results will be publicly available at the OnFoods website (www.onfoods.it, info@onfoods.it) in line with the transparency policy. The results of the FACILITY study will be published in indexed scientific journals, regardless of whether they are positive, negative, or inconclusive at the end of the study. Participants' data will be published anonymously.

The studies involving humans were approved by Comitato Etico Territoriale Lombardia 1. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

AV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VC: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SS: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GV: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ID: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GB: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. LD: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. GZ: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Project funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.3—Call for tender No. 341 of 15 March 2022 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU. Award Number: Project code PE00000003, Concession Decree No. 1550 of 11 October 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP F13C22001210007, Project title “ON Foods—Research and innovation network on food and nutrition Sustainability, Safety and Security—Working ON Foods”. The ONFOODS project considers the food system framework, which encompasses food production, food supply chains, food environments, food habits, and consumer food choices, including related nutritional, environmental, and socioeconomic outcomes. OnFoods addresses this challenge by acting through the coordinated activities of 7 Spokes, each of which focuses on a defined issue: indeed, the FACILITY study belongs to the Spoke 6, aimed at “tackling malnutrition”.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2025.1450324/full#supplementary-material

1. Jolivet RR, Moran AC, O’Connor M, Chou D, Bhardwaj N, Newby H, et al. Ending preventable maternal mortality: phase II of a multi-step process to develop a monitoring framework, 2016–2030. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2018) 18(1):258. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1763-8

2. United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015). Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (Accessed June 14, 2024).

3. WHO, UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF, UNWomen, The World Bank Group. Survive, Thrive, Transform. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health: 2018 report on progress towards 2030 targets (2018). Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/EWECGSMonitoringReport2018_en.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2024).

4. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight (2024). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (Accessed June 14, 2024).

5. Jebeile H, Kelly AS, O'Malley G, Baur LA. Obesity in children and adolescents: epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2022) 10(5):351–65. doi: 10.1016/s2213-8587(22)00047-x

6. Kumar S, Kelly AS. Review of childhood obesity. Mayo Clin Proc. (2017) 92(2):251–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.09.017

7. Birch LL, Ventura AK. Preventing childhood obesity: what works? Int J Obes (2005). (2009) 33(S1):S74–81. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.22

8. World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases: Childhood overweight and obesity (2020). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/noncommunicable-diseases-childhood-overweight-and-obesity (Accessed June 14, 2024).

9. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. (2017) 390(10113):2627–42. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32129-3

10. Haddad L, Achadi E, Bendech MA, Ahuja A, Bhatia K, Bhutta Z, et al. The global nutrition report 2014: actions and accountability to accelerate the world’s progress on nutrition. J Nutr. (2015) 145(4):663–71. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.206078

11. World Health Organization. European Regional Obesity Report (2022). Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/353747/9789289057738-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed June 14, 2024).

12. Cameron AJ, Spence AC, Laws R, Hesketh KD, Lioret S, Campbell KJ. A review of the relationship between socioeconomic position and the early-life predictors of obesity. Curr Obes Rep. (2015) 4(3):350–62. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0168-5

13. Lauria L, Spinelli A, Cairella G, Censi L, Nardone P, Buoncristiano M, 2012 Group OKkio alla SALUTE. Dietary habits among children aged 8–9 years in Italy. Ann Ist Super Sanità. (2015) 51(4):371–81. doi: 10.4415/ANN_15_04_20

14. Romanelli R, Cecchi N, Carbone MG, Dinardo M, Gaudino G, Miraglia del Giudice E, et al. Pediatric obesity: prevention is better than care. Ital J Pediatr. (2020) 46(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s13052-020-00868-7

15. Center for Disease Prevention and Control. Obesity (2022). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/obesity/index.htm (Accessed June 14, 2024).

16. Raspini B, Porri D, De Giuseppe R, Chieppa M, Liso M, Cerbo RM, et al. Prenatal and postnatal determinants in shaping offspring’s microbiome in the first 1000 days: study protocol and preliminary results at one month of life. Ital J Pediatr. (2020) 46(1). doi: 10.1186/s13052-020-0794-8

17. Pietrobelli A, Agosti M, The MeNu Group. Nutrition in the first 1000 days: ten practices to minimize obesity emerging from published science. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14(12):1491. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121491

18. Koning M, Hoekstra T, de Jong E, Visscher TLS, Seidell JC, Renders CM. Identifying developmental trajectories of body mass index in childhood using latent class growth (mixture) modelling: associations with dietary, sedentary and physical activity behaviors: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16(1):1128. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3757-7

19. Rousham EK, Goudet S, Markey O, Griffiths P, Boxer B, Carroll C, et al. Unhealthy food and beverage consumption in children and risk of overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Nutr (Bethesda, Md.). (2022) 13(5):1669–96. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmac032

20. Geserick M, Vogel M, Gausche R, Lipek T, Spielau U, Keller E, et al. Acceleration of BMI in early childhood and risk of sustained obesity. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379(14):1303–12. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1803527

21. Costa de Oliveira Forkert E, de Moraes ACF, Carvalho HB, Kafatos A, Manios Y, Sjöström M, et al. Abdominal obesity and its association with socioeconomic factors among adolescents from different living environments. Pediatr Obes. (2017) 12(2):110–9. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12116

22. Cheng TL, Johnson SB, Goodman E. Breaking the intergenerational cycle of disadvantage: the three generation approach. Pediatrics. (2016) 137(6):e20152467. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2467

23. Nicolaidis S. Environment and obesity. Metab Clin Exp. (2019) 100(153942):153942. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.07.006

24. Lee A, Cardel M, Donahoo WT. Social and environmental factors influencing obesity. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc. (2000).

25. Booth KM, Pinkston MM, Poston WSC. Obesity and the built environment. J Am Diet Assoc. (2005) 105(5):110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.045

26. European Economic and Social Committee. Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘Measures to reduce child obesity’ (2023). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52023AE0880 (Accessed June 14, 2024).

27. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, Jastreboff AM, et al. American Association of clinical endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. (2016) 22:1–203. doi: 10.4158/ep161365.gl

28. Lohman TG. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books (1988).

29. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Anthropometry procedure manual (2017). Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2017-2018/manuals/2017_Anthropometry_Procedures_Manual.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2024).

30. Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Bellisle F, Sempé M, Guilloud-Bataille M, Patois E. Adiposity rebound in children: a simple indicator for predicting obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. (1984) 39(1):129–35. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/39.1.129

31. Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Maillot M, Bellisle F. Early adiposity rebound: causes and consequences for obesity in children and adults. Int J Obes. (2006) 30(S4):S11–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803514

32. Sofi F, Macchi C, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Mediterranean diet and health status: an updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr. (2014) 17(12):2769–82. doi: 10.1017/s1368980013003169

33. Sofi F, Dinu M, Pagliai G, Marcucci R, Casini A. Validation of a literature-based adherence score to Mediterranean diet: the MEDI-LITE score. Int J Food Sci Nutr. (2017) 68(6):757–62. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2017.1287884

34. Serra-Majem L, Ribas L, Ngo J, Ortega RM, García A, Pérez-Rodrigo C, et al. Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean diet quality index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. (2004) 7(7):931–5. doi: 10.1079/phn2004556

35. Coulson JC, Fox KR, Lawlor DA, Trayers T. Residents’ diverse perspectives of the impact of neighbourhood renewal on quality of life and physical activity engagement: improvements but unresolved issues. Health Place. (2011) 17(1):300–10. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.003

36. International Physical Activity Questionnaire. (2022). Available at: https://sites.google.com/view/ipaq/home?authuser=0 (Accessed June 14, 2024).

37. Mannocci A, Masala D, Mei D, Tribuzio AM, Villari P, La Torre G. International physical activity questionnaire: validation and assessment in an Italian sample. Ital J Public Health. (2010) 7:369–76. doi: 10.2427/5694

38. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World health organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. (2020) 54(24):1451–62. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

39. World Health Organization. Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age. Geneva. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (2019).

40. Hagströmer M, Bergman P, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Manios Y, et al. Concurrent validity of a modified version of the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ-A) in European adolescents: the HELENA study. Int J Obes. (2008) 32(S5):S42–8. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.182

41. Mannocci A, Masala D, Mei D, Tribuzio AM, Villari P, La Torre G. International physical activity questionnaire for adolescents (IPAQ A): reliability of an Italian version. Minerva Pediatr. (2021) 73(5):383–90. doi: 10.23736/s2724-5276.16.04727-7

42. Centro di Ricerca Alimentare e Nutrizione. Linea Guida per una Sana alimentazione (2018). Available at: https://www.crea.gov.it/documents/59764/0/LINEE-GUIDA+DEFINITIVO.pdf/28670db4-154c-0ecc-d187-1ee9db3b1c65?t=1576850671654 (Accessed June 14, 2024).

43. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

44. Curcio G, Tempesta D, Scarlata S, Marzano C, Moroni F, Rossini PM, et al. Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI). Neurol Sci. (2013) 34(4):511–9. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1085-y

45. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D'Ambrosio C, Hall WA, Kotagal S, Lloyd RM, et al. Consensus statement of the American academy of sleep medicine on the recommended amount of sleep for healthy children: methodology and discussion. J Clin Sleep Med. (2016) 12(11):1549–61. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6288

46. Driscoll K, Pianta RC. Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of conflict and closeness in parent-child relationships during early childhood. J Early Child Infant Psychol. (2011) 7:1–24.

47. Rinaldi T, Castelli I, Palena N, Greco A, Pianta R, Marchetti A, et al. The representation of child–parent relation: validation of the Italian version of the child–parent relationship scale (CPRS-I). Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1194644. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1194644

48. Wang P, Chen X, Gong J, Jacques-Tiura AJ. Reliability and validity of the personal social capital scale 16 and personal social capital scale 8: two short instruments for survey studies. Soc Indic Res. (2014) 119(2):1133–48. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0540-3

49. Schoeppe S, Braubach M, WHO Regional Office for Europe. Tackling obesity by creating healthy residential environments (2007). Available at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/107834 (Accessed June 14, 2024).

50. World Health Organization. Child growth standards (2006). Available at: Available at: https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/standards (Accessed April 24 2024).

51. Sonneville KR, Horton NJ, Micali N, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Solmi F, et al. Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: does loss of control matter? JAMA Pediatr. (2013) 167(2):149. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.12

52. Harshman SG, Castro I, Perkins M, Luo M, Barrett Mueller K, Cena H, et al. Pediatric weight management interventions improve prevalence of overeating behaviors. Int J Obes. (2022) 46(3):630–6. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00989-x

53. Fiechtner L, Fonte ML, Castro I, Gerber M, Horan C, Sharifi M, et al. Determinants of binge eating symptoms in children with overweight/obesity. Childhood Obesity. (2018) 14(8):510–7. doi: 10.1089/chi.2017.0311

54. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BARBARAE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2003) 35(8):1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000078924.61453.fb

55. Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Okkio alla salute. Indagine nazionale 2019: i dati nazionali (2019). Available at: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/okkioallasalute/indagine-2019-dati (Accessed June 14, 2024).

56. Isong IA, Rao SR, Bind M-A, Avendaño M, Kawachi I, Richmond TK. Racial and ethnic disparities in early childhood obesity. Pediatrics. (2018) 141(1):e20170865. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0865

57. Jamerson T, Sylvester R, Jiang Q, Corriveau N, DuRussel-Weston J, Kline-Rogers E, et al. Differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors and health behaviors between black and non-black students participating in a school-based health promotion program. Am J Health Promot. (2017) 31(4):318–24. doi: 10.1177/0890117116674666

58. Parsons TJ, Power C, Logan S, Summerbell CD. Childhood predictors of adult obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. (1999) 23(Suppl 8):S1–107.10641588

59. Valerio G, Maffeis C, Saggese G, Ambruzzi MA, Balsamo A, Bellone S, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of pediatric obesity: consensus position statement of the Italian society for pediatric endocrinology and diabetology and the Italian society of pediatrics. Ital J Pediatr. (2018) 44(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0525-6

60. Jia P, Dai S, Rohli KE, Rohli RV, Ma Y, Yu C, et al. Natural environment and childhood obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. (2021) 22(S1):e13097. doi: 10.1111/obr.13097

61. LeCroy MN, Kim RS, Stevens J, Hanna DB, Isasi CR. Identifying key determinants of childhood obesity: a narrative review of machine learning studies. Child Obes. (2021) 17(3):153–9. doi: 10.1089/chi.2020.0324

62. Hemmingsson E. Early childhood obesity risk factors: socioeconomic adversity, family dysfunction, offspring distress, and junk food self-medication. Curr Obes Rep. (2018) 7(2):204–9. doi: 10.1007/s13679-018-0310-2

63. Larqué E, Labayen I, Flodmark C-E, Lissau I, Czernin S, Moreno LA, et al. From conception to infancy—early risk factors for childhood obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2019) 15(8):456–78. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0219-1

64. Ziauddeen N, Roderick PJ, Macklon NS, Alwan NA. Predicting childhood overweight and obesity using maternal and early life risk factors: a systematic review. Obes Rev. (2018) 19:302–12. doi: 10.1111/obr.12640

65. Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, Yang M, Glazebrook CP. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child. (2012) 97(12):1019–26. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302263

66. Poorolajal J, Sahraei F, Mohamdadi Y, Doosti-Irani A, Moradi L. Behavioral factors influencing childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract. (2020) 14(2):109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2020.03.002

67. Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM. Risk factors for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 days. Am J Prev Med. (2016) 50(6):761–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.012

68. Bagordo F, De Donno A, Grassi T, Guido M, Devoti G, Ceretti E, et al. Lifestyles and socio-cultural factors among children aged 6–8 years from five Italian towns: the MAPEC_LIFE study cohort. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17(1):233. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4142-x

69. Delbosq S, Velasco V, Vercesi C, Vecchio LP. Adolescents’ nutrition: the role of health literacy, family and socio-demographic variables. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(23):15719. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192315719

70. Bracale R, Milani Marin LE, Russo V, Zavarrone E, Ferrara E, Balzaretti C, et al. Family lifestyle and childhood obesity in an urban city of northern Italy. Eat Weight Disord. (2015) 20(3):363–70. doi: 10.1007/s40519-015-0179-y

71. Paduano S, Greco A, Borsari L, Salvia C, Tancredi S, Pinca J, et al. Physical and sedentary activities and childhood overweight/obesity: a cross-sectional study among first-year children of primary schools in Modena, Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(6):3221. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063221

72. Sanmarchi F, Esposito F, Marini S, Masini A, Scrimaglia S, Capodici A, et al. Children’s and families’ determinants of health-related behaviors in an Italian primary school sample: the ’seven days for my health’ project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(1):460. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010460

73. Pellegrino A, Bacci S, Guido F, Zoppi A, Toncelli L, Stefani L, et al. Interaction between geographical areas and family environment of dietary habits, physical activity, nutritional knowledge and obesity of adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20(2):1157. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021157

74. Allport BS, Johnson S, Aqil A, Labrique AB, Nelson T, Angela KC, et al. Promoting father involvement for child and family health. Acad Pediatr. (2018) 18(7):746–53. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.03.011

75. Versele V, Dieberger A, van Poppel M, Van De Maele K, Deliens T, Aerenhouts D, et al. The influence of parental body composition and lifestyle on offspring growth trajectories. Pediatr Obes. (2022) 17(10):1–14. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12929

76. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche PC, Krleža-Jerić K, et al. SPIRIT 2013 Statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. (2013) 158(3):200. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583

Keywords: paediatric obesity, healthy lifestyle, risk factors, mothers, environment, low socioeconomic status

Citation: Vincenti A, Calcaterra V, Santero S, Viroli G, Di Napoli I, Biino G, Daconto L, Cusumano M, Zuccotti G and Cena H (2025) FACILITY: feeding the family—the intergenerational approach to fight obesity, a cross-sectional study protocol. Front. Pediatr. 13:1450324. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1450324

Received: 11 September 2024; Accepted: 17 March 2025;

Published: 31 March 2025.

Edited by:

Sen Li, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, ChinaReviewed by:

Debora Porri, University of Messina, ItalyCopyright: © 2025 Vincenti, Calcaterra, Santero, Viroli, Di Napoli, Biino, Daconto, Cusumano, Zuccotti and Cena. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alessandra Vincenti, YWxlc3NhbmRyYS52aW5jZW50aUB1bmlwdi5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.