95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Pediatr. , 04 September 2024

Sec. Pediatric Immunology

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2024.1446779

Amy S. Paller1,2*

Amy S. Paller1,2* Jonathan I. Silverberg3

Jonathan I. Silverberg3 Mercedes E. Gonzalez4,5

Mercedes E. Gonzalez4,5 Lynda C. Schneider6

Lynda C. Schneider6 Robert Sidbury7

Robert Sidbury7 Zhen Chen8

Zhen Chen8 Ashish Bansal8

Ashish Bansal8 Zhixiao Wang8

Zhixiao Wang8 Randy Prescilla9

Randy Prescilla9

Background: Moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) often has a profound impact on the quality of life of young children and their caregivers. One of the most burdensome symptoms reported by patients is skin pain.

Methods: This post hoc analysis focuses on the impact of dupilumab treatment on skin pain in young children using data from the LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B (NCT03346434), a 16-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study in 162 children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD receiving dupilumab or placebo, plus topical corticosteroids (TCS). Analyses were performed on the full analysis set and subgroups of patients who did not achieve an Investigator's Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (IGA >1 subgroup), or who did not achieve a 75% improvement from baseline in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (<EASI-75 subgroup), at week 16 (patients who did not achieve the primary or key secondary endpoints in LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B).

Results: At week 16, change from baseline in the skin pain NRS was significantly greater in the dupilumab group vs. the placebo group (−3.93 vs. −0.62, p < 0.0001) and significantly more patients receiving dupilumab vs. placebo achieved a clinically meaningful improvement at week 16 (47.2% vs. 10.8%, p < .0001). Similar results between dupilumab vs. placebo were seen in the two subgroups IGA >1 and <EASI-75.

Conclusions: This analysis showed rapid, clinically meaningful, and statistically significant improvements in skin pain in patients treated with dupilumab plus TCS vs. placebo plus TCS.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory systemic disease with an estimated prevalence of 12% in children younger than age 6 years (1). The most burdensome symptoms reported by patients are itch (pruritus) and skin pain, which can negatively impact the quality of life of both affected children and their caregivers and families (2, 3).

In contrast to itch, skin pain is less well-characterized in children with AD. However, its importance is increasingly being recognized when evaluating the burden of AD (4–7). A recent study investigating the burden and characteristics of skin pain among children with AD reported that nearly half the infants and children with AD had caregiver-reported skin pain, which was reported to be more intense with more severe disease (8). Furthermore, greater intensity of skin pain was associated with an overall worse quality of life (8).

Patient-reported outcomes can provide an important complement to clinician-reported outcomes in both clinical trials and daily clinical practice. The use of observer-reported outcomes (ObsROs) is supported when a patient (for example, a young child) is unable to provide a reliable and valid self-reported response about their own health experiences (9, 10). The caregiver-reported skin pain Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) is a validated ObsRO tool for the assessment of skin pain severity in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD (11).

Phase 3 trials in children, adolescents, and adults with AD demonstrated that treatment with dupilumab, compared with placebo, leads to substantial improvements in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life, with an acceptable safety profile (12–16).

In the LIBERTY AD PRE-SCHOOL part B study (NCT03346434), a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial, dupilumab administered with concomitant low-potency topical corticosteroids (TCS) significantly improved AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD (16).

This study evaluated the impact of treatment with dupilumab plus low-potency TCS on skin pain in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD who had been included in the LIBERTY AD PRE-SCHOOL part B study.

This was a post hoc analysis of data from LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B (NCT03346434), a 16-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of dupilumab plus TCS in patients aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD that was inadequately controlled with topical therapies (16).

The full study design and primary analysis of LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B has been reported previously (16). Briefly, patients included were aged 6 months to 5 years at screening, with moderate-to-severe AD according to the consensus criteria of the American Academy of Dermatology (17) and a documented recent history (within 6 months before the screening visit) of inadequate response to topical AD medication. At screening, patients had an Investigators’ Global Assessment (IGA) score ≥3, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) ≥16, body surface area (BSA) affected by AD ≥10%, and worst scratch/itch NRS score ≥4.

The primary and key secondary endpoints of LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B were the proportion of patients achieving an IGA score of 0/1 (clear/almost clear skin) at week 16 and the proportion of patients achieving at least a 75% improvement from baseline in EASI (EASI-75) at week 16, respectively.

LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. Local institutional review boards or ethics committees at each trial center oversaw trial conduct and documentation, and reviewed and approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian for each study participant.

Patients received subcutaneous dupilumab every 4 weeks (200 mg for baseline bodyweight ≥5 to <15 kg; 300 mg for baseline bodyweight ≥15 to <30 kg) or matched placebo, with a standardized daily regimen of low-potency TCS (hydrocortisone acetate 1% cream). In-clinic visits were planned at baseline, week 1, week 2, and week 4, then monthly through week 16, with weekly telephone visits between clinic visits. The validated caregiver-reported skin pain NRS was used to evaluate patients’ AD-related skin pain during the previous 24 h on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain possible). A 2-to-4-point improvement in skin pain NRS is considered to be clinically meaningful in children aged 6 months to 5 years (11).

Analyses were performed in the full analysis set (FAS), which included all randomized patients, and in the subgroups of patients who did not achieve an IGA score of 0 or 1 (IGA >1) at week 16, or who did not achieve EASI-75 at week 16 (<EASI-75), (i.e., patients who did not achieve the primary or key secondary endpoints in LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B).

Least squares (LS) mean change from baseline in skin pain NRS was analyzed using analysis of covariance, with treatment group, stratification factors, and relevant baseline measurements included in the model. Patients with missing values at week 16 due to rescue treatment, withdrawn consent, adverse events (AEs), or lack of efficacy (as deemed by the investigator) were imputed by worst observation carried forward. Missing values due to other reasons were imputed using multiple imputation.

The proportion of patients with ≥4-point improvement from baseline in skin pain NRS was analyzed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test after adjustment for randomization strata. Patients with missing values at week 16 due to use of rescue treatment, withdrawn consent, AEs, or lack of efficacy (as deemed by the investigator) were considered to be non-responders. Missing data due to any other reasons, including COVID-19, were imputed using multiple imputation.

Safety outcomes were assessed in the safety analysis set (SAS), which included all patients who received any study drug, and in the IGA >1 and <EASI-75 subgroups. Safety outcomes included proportions of patients with ≥1 treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE), ≥1 serious TEAE, TEAEs leading to permanent study withdrawal, and patients with use of ≥1 rescue medication.

Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was calculated for dupilumab vs. placebo; all p-values were regarded as nominal, with the exception of change from baseline in skin pain NRS at week 16, which was a pre-specified secondary endpoint in LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA) or higher.

162 patients were included in the FAS (83 dupilumab plus TCS; 79 placebo plus TCS) (Table 1). In the dupilumab and placebo groups, 60 and 76 patients, respectively, did not achieve an IGA score <1 at week 16 and were included in the IGA >1 subgroup. 39 and 71 patients, for dupilumab and placebo, respectively, did not achieve EASI-75 and were included in the <EASI-75 subgroup. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were balanced between the treatment groups and the IGA >1 and <EASI-75 subgroups.

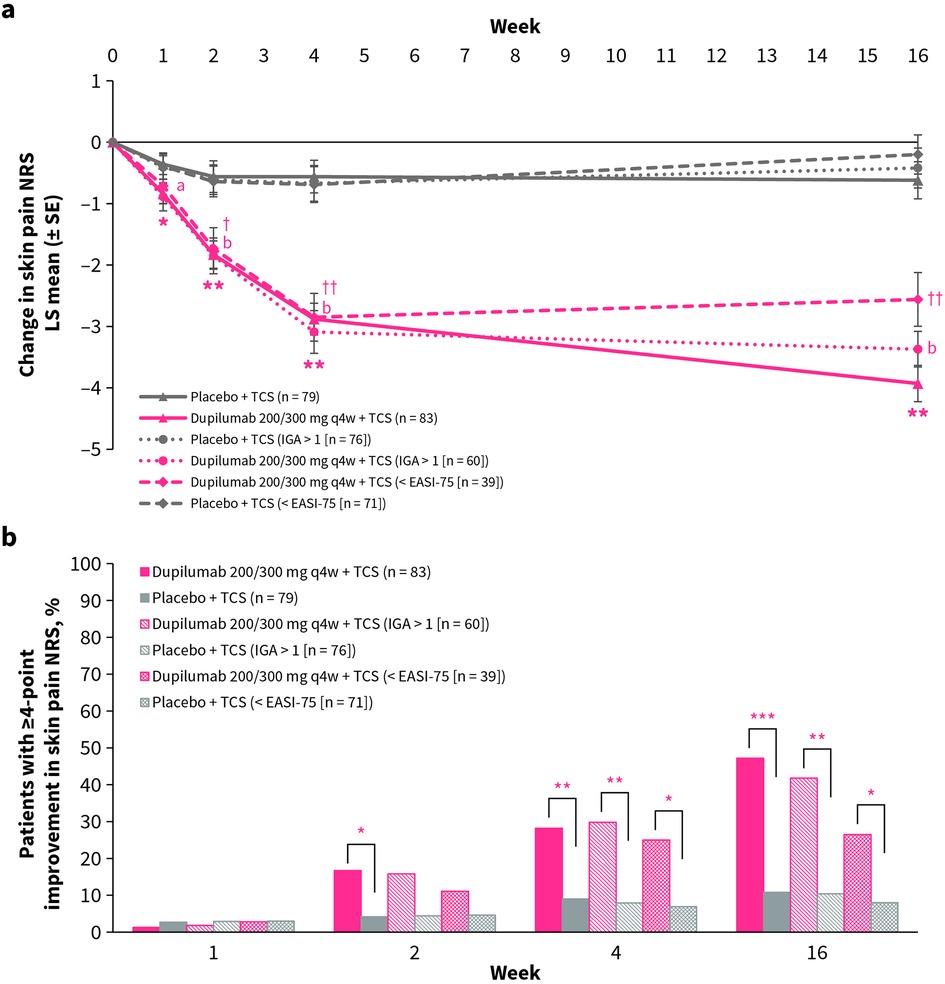

At week 16, LS mean change from baseline in skin pain NRS was significantly greater in the dupilumab group compared with the placebo group (−3.93 vs. −0.62, p < 0.0001, respectively), with a significant benefit for dupilumab compared with placebo evident from week 1 onward (Figure 1a). In the subgroup of patients with IGA >1 (60 in the dupilumab group; 76 in the placebo group) and in the subgroup of patients with <EASI-75 (39 in the dupilumab group; 71 in the placebo group) at week 16, a significant benefit for dupilumab compared with placebo was seen from week 2 onward, maintained through week 16 (−3.37 vs. −0.42 and −2.56 vs. −0.20, respectively, both p < 0.0001; Figure 1a).

Figure 1. (a) LS mean change from baseline in skin pain NRS over time for dupilumab vs. placebo. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.0001 (FAS); ap < 0.05, bp < 0.0001 (IGA >1); †p < 0.01, ††p < 0.0001 (<EASI-75). (b) Proportion of patients with ≥4-point improvement in skin pain NRS over time for dupilumab vs. placebo. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001. EASI-75, 75% improvement from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator's Global Assessment; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; q4w, every 4 weeks; SE, standard error; TCS, topical corticosteroids.

At week 16, the proportion of patients with ≥4-point improvement from baseline in skin pain NRS was significantly greater in the dupilumab group compared with the placebo group (47.2% vs. 10.8%, p < 0.0001, respectively), with a significant benefit for dupilumab compared with placebo being evident from week 1 onward (Figure 1b). In the subgroup of patients with IGA >1 and the subgroup of patients with <EASI-75 at week 16, a significant benefit for dupilumab compared with placebo was seen from week 4 until week 16 (41.8% vs. 10.4% and 26.5% vs. 8.0% respectively, both p < 0.05; Figure 1b).

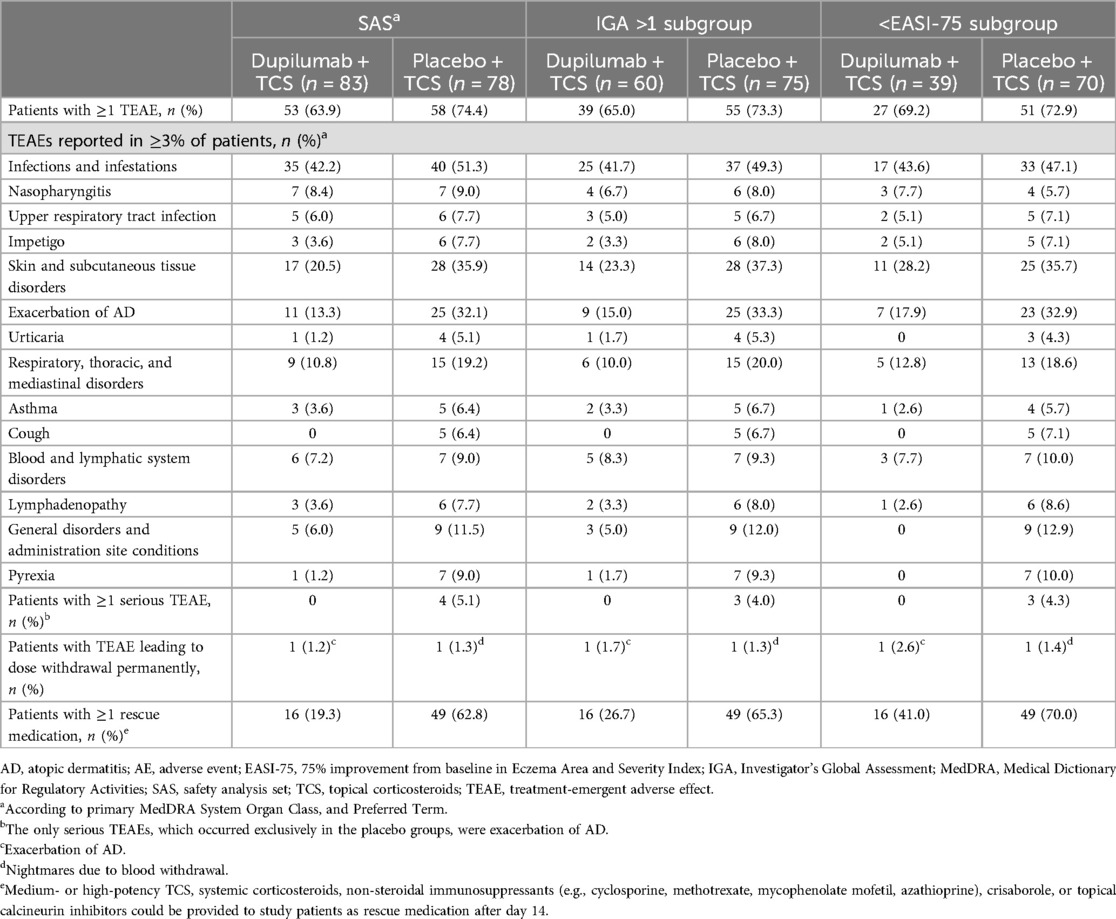

The primary analysis of the LIBERTY AD PRE-SCHOOL part B study reported that dupilumab was generally well tolerated, with an acceptable safety profile (16). Safety outcomes for patients in the SAS and the IGA >1 and <EASI-75 subgroups were comparable (Table 2) (16, 18). In the SAS and in both subgroups, the proportion of patients with ≥1 TEAE and the use of ≥1 rescue medication was lower in the dupilumab groups compared with the placebo groups (Table 2) (16, 18). Serious TEAEs (exacerbation of AD) only occurred in the placebo groups, and there was only one occurrence of TEAEs leading to permanent withdrawal in both the dupilumab and placebo groups (Table 2) (16, 18).

Table 2. Number of patients with AEs reported in the safety analysis set16 and IGA >118 and >EASI-75 subgroups, at week 16.

Skin pain is a symptom frequently reported by patients and is increasingly being recognized when evaluating the burden of AD (4–8). While associated with reduced quality of life, skin pain is not well characterized in children (8). Recently, the importance of exploring pain in AD as an independent symptom has been underscored by the fourth international consensus meeting to harmonize core outcome measures for atopic eczema/dermatitis clinical trials (the HOME initiative) (19).

In children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD, dupilumab treatment with concomitant low-potency TCS compared with placebo plus TCS provided rapid and significant improvements in caregiver-reported skin pain, with improvements sustained over 16 weeks. Dupilumab plus TCS also provided a rapid and clinically meaningful response of at least a 4-point improvement in skin pain NRS scores in significantly more patients treated with dupilumab compared with placebo, sustained over 16 weeks. Significant benefits for dupilumab compared with placebo were seen in the FAS, and in the subgroup of patients with IGA >1 and the subgroup of patients with <EASI-75 at week 16. These results confirm and extend earlier findings demonstrating the efficacy of dupilumab treatment in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD (16) and are in line with previously reported results for adults with moderate-to-severe AD (20).

The clinician-reported endpoints, achievement of IGA 0/1 or EASI-75, are valuable measures that are widely used in clinical trials to define an optimal response to therapy. However, these endpoints do not capture the impact from the patients’ perspective, including of treatment for skin pain (19). This analysis shows significant and potentially clinically meaningful improvements in caregiver-reported skin pain in the dupilumab-treated subgroups, even in patients who did not achieve IGA 0/1 or EASI-75 at week 16.

This analysis provides support that includes the use of tools, such as the skin pain NRS, to capture the caregiver and/or patient perspective of the benefits of therapy may provide a more holistic view of treatment response. Considering the multidimensional nature of AD, assessing skin pain could be of value to prescribing physicians in their routine clinical practice. However, it should be noted that it may be challenging for caregivers to assess skin pain and distinguish it from itch, especially in young, non-verbal children (21).

Strengths of this study include the randomized, placebo-controlled study design. Limitations of the study include the relatively small number of children in the youngest age range (6 months to <2 years), the short (16-week) study duration, and the post hoc nature of this analysis including nominal p-values.

In conclusion, dupilumab treatment with concomitant low-potency TCS provided clinically meaningful and rapid, statistically significant improvements vs. placebo in skin pain in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the indication has been approved by a regulatory body, if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to https://vivli.org/.

The studies involving humans were approved by local institutional review boards or ethics committees. LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. Local institutional review boards or ethics committees at each trial center oversaw trial conduct and documentation, and reviewed and approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian for each study participant.

ASP: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JIS: Validation, Writing – review & editing. MEG: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LCS: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RS: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZC: Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZW: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RP: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research and publication were sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Research sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. [LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B (NCT03346434)]. Medical writing/editorial assistance was provided by Liselotte van Delden, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., according to Good Publication Practice guidelines. The authors would like to thank Dr JP Thyssen (Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Bispebjerg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) for his contributions to the manuscript. The authors extend their thanks to the children and their caregivers who participated in the clinical trial.

ASP: AbbVie, Applied Pharma Research, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Krystal Biotech, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Timber, UCB – investigator; AbbVie, Abeona Therapeutics, Apogee Therapeutics, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Aslan Pharmaceuticals, BioCryst, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Incyte, Johnson & Johnson, Krystal Biotech, LEO Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Nektar Therapeutics, Primus, Procter & Gamble, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Seanergy, TWI Biotech, UCB – consultant; AbbVie, Abeona Therapeutics, Galderma – data and safety monitoring boards. JIS: AbbVie, AnaptysBio, Alamar Biosciences, Aldena Therapeutics, Amgen, AOBiome, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Arena, Asana BioSciences, Aslan Pharmaceuticals, BiomX, Biosion, Bodewell, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Castle Biosciences, Celgene, Connect Biopharma, CorEvitas, Dermavant, Dermira, DermTech, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Glenmark, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Optum, Pfizer, PuriCore, RAPT Therapeutics, Recludix Pharma, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Shaperon, Target RWE, Union therapeutics, UpToDate – consultant and/or advisory board member; AbbVie, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi – speaker; Galderma, Incyte, Pfizer – grants. MEG: AbbVie, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Amgen, Anterogen, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Krystal Biotech, Neilsen Biosciences, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi – investigator; Abeona Therapeutics, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Alphyn Biologics, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Krystal Biotech, Verrica Pharmaceuticals – consultant; AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Krystal Biotech, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Verrica Pharmaceuticals – speakers bureau. LCS: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. – investigator; Pfizer – grant; AbbVie, Division of Allergy, Immunology, and Transplantation (DAIT)/National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), LEO Pharma, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Triveni Bio – advisory boards. RS: Castle Biosciences, Galderma, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., UCB – investigator; Beiersdorf – speaker; Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Dermavent, LEO Pharma, Lilly – consultant. ZC, AB, ZW: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. – employees of and shareholders in the company. RP: Sanofi – employee of and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AD, atopic dermatitis; AE, adverse event; BSA, body surface area; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; EASI-75, 75% improvement from baseline in EASI; FAS, full analysis set; IGA, Investigator's Global Assessment; LS, least squares; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; ObsRO, observer-reported outcome; q4w, every 4 weeks; SAS, safety analysis set; SCORAD, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; TCS, topical corticosteroids; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

1. Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, Simpson EL, Weidinger S, Mina-Osorio P, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2021) 126(4):417–28.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.02033421555

2. Brenninkmeijer EEA, Legierse CM, Sillevis Smitt JH, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA, Bos JD. The course of life of patients with childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. (2009) 26(1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00745.x19250399

3. Yang EJ, Beck KM, Sekhon S, Bhutani T, Koo J. The impact of pediatric atopic dermatitis on families: a review. Pediatr Dermatol. (2019) 36(1):66–71. doi: 10.1111/pde.1372730556595

4. von Kobyletzki LB, Thomas KS, Schmitt J, Chalmers JR, Deckert S, Aoki V, et al. What factors are important to patients when assessing treatment response: an international cross-sectional survey. Acta Derm Venereol. (2017) 97(1):86–90. doi: 10.2340/00015555-248027305646

5. Fuxench ZCC. Pain in atopic dermatitis: it’s time we addressed this symptom further. Br J Dermatol. (2020) 182(6):1326–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.1878531956992

6. Ständer S, Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Thyssen JP, Kabashima K, Ball SG, et al. Clinical relevance of skin pain in atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. (2020) 19(10):921–6. doi: 10.36849/JDD.2020.5498

7. Misery L, Belloni Fortina A, El Hachem M, Chernyshov P, von Kobyletzki L, Heratizadeh A, et al. A position paper on the management of itch and pain in atopic dermatitis from the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis (ISAD)/Oriented Patient-Education Network in Dermatology (OPENED) task force. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2021) 35(4):787–96. doi: 10.1111/jdv.1691633090558

8. Cheng BT, Paller AS, Griffith JW, Silverberg JI, Fishbein AB. Burden and characteristics of skin pain among children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2022) 10(4):1104–6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.12.01234954412

9. Matza LS, Patrick DL, Riley AW, Alexander JJ, Rajmil L, Pleil AM, et al. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: report of the ISPOR PRO good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force. Value Health. (2013) 16(4):461–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.00423796280

10. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Patient-Focused Drug Development: Selecting, Developing, or Modifying Fit-for-Purpose Clinical Outcome Assessments (2022). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-focused-drug-development-selecting-developing-or-modifying-fit-purpose-clinical-outcome (Accessed August 27, 2024).

11. Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Marron SE, Clark M, Harris N, Kosa K, et al. Skin pain and sleep quality numeric rating scales for children aged 6 months to 5 years with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2024). doi: 10.1111/jdv.20199.38943435 [Epub ahead of print]

12. Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 investigators. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375(24):2335–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa161002027690741

13. Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2017) 389(10086):2287–303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-128478972

14. Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Boguniewicz M, Sher L, Gooderham MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. (2020) 156(1):44–56. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.333631693077

15. Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, Wollenberg A, Cork MJ, Arkwright PD, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2020) 83(5):1282–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.05432574587

16. Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, Cork MJ, Wollenberg A, Arkwright PD, et al. Participating investigators. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2022) 400(10356):908–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01539-236116481

17. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2014) 70(2):338–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.01024290431

18. Cork MJ, Lockshin B, Pinter A, Chen Z, Shumel B, Prescilla R. Clinically meaningful responses to dupilumab among children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis who did not achieve clear or almost clear skin according to the Investigator’s Global Assessment: a post hoc analysis of a phase 3 trial. Acta Derm Venereol. (2024) 104:adv13467. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v104.1346738348724

19. Chalmers JR, Simpson E, Apfelbacher CJ, Thomas KS, von Kobyletzki L, Schmitt J, et al. Report from the fourth international consensus meeting to harmonize core outcome measures for atopic eczema/dermatitis clinical trials (HOME initiative). Br J Dermatol. (2016) 175(1):69–79. doi: 10.1111/bjd.1477327436240

20. Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Cork MJ, de Bruin-Weller M, Yosipovitch G, et al. Dupilumab significantly modulates pain and discomfort in patients with atopic dermatitis: a post hoc analysis of 5 randomized clinical trials. Dermatitis. (2021) 32(1S):S81–91. doi: 10.1097/DER.000000000000069833165005

Keywords: children, atopic dermatitis, skin pain, efficacy, dupilumab

Citation: Paller AS, Silverberg JI, Gonzalez ME, Schneider LC, Sidbury R, Chen Z, Bansal A, Wang Z and Prescilla R (2024) Dupilumab treatment reduces caregiver-reported skin pain in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis aged 6 months to 5 years. Front. Pediatr. 12:1446779. doi: 10.3389/fped.2024.1446779

Received: 10 June 2024; Accepted: 19 August 2024;

Published: 4 September 2024.

Edited by:

Viviana Moschese, University of Rome Tor Vergata, ItalyReviewed by:

Mara Giavina-Bianchi, Albert Einstein Israelite Hospital, BrazilCopyright: © 2024 Paller, Silverberg, Gonzalez, Schneider, Sidbury, Chen, Bansal, Wang and Prescilla. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amy S. Paller, YXBhbGxlckBub3J0aHdlc3Rlcm4uZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.