- 1Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 2Section of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 3School of Nursing, Trinity Western University, Langley, BC, Canada

- 4Canchild Centre for Childhood Disability Research, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 5Azrrieli Accelerator, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 6Department of Psychology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 7Independent Researcher, Squamish, BC, Canada

- 8Division of Neonatology, Research Center, Unité d’éthique Clinique, Bureau du Partenariat Patients-Familles-Soignants, CHU Sainte-Justine, Montréal, QC, Canada

- 9Department of Pediatrics, Bureau de l’éthique clinique (BEC), Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada

- 10School of Nursing, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Background: Trust is a foundation of the therapeutic relationship and is associated with important patient outcomes. Building trust between parents of children with medical complexity (CMC) and physicians during inpatient care is complicated by lack of relational continuity, cumulative (sometimes negative) parent experiences and the need to adjust roles and expectations to accommodate parental expertise. This study's objective was to describe how parents of CMC conceptualize trust with physicians within the pediatric inpatient setting and to provide recommendations for building trust in these relationships.

Methods: Interviews with 16 parents of CMC were completed and analyzed using interpretive description methodology.

Results: The research team identified one overarching meta theme regarding factors that influence trust development: situational awareness is needed to inform personalized care of children and families. There were also six major themes: (1) ensuring that the focus is on the child and family, (2) respecting both parent and physician expertise, (3) collaborating effectively, (4) maintaining a flow of communication, (5) acknowledging the impact of personal attributes, and (6) recognizing issues related to the healthcare system.

Discussion: Many elements that facilitated trust development were also components of patient- and family-centered care. Parents in this study approached trust with inpatient physicians as something that needs to be earned and reciprocated. To gain the trust of parents of CMC, inpatient physicians should personalize medical care to address the needs of each child and should explore the perceptions, expertise, and previous experiences of their parents.

1 Introduction

Research and professional consensus support the view that trust is foundational to effective therapeutic encounters (1) and is associated with important outcomes including patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment, clinical outcomes, and patient self-reported health (2, 3). This view is consistent in the adult (1, 2, 4–8) and pediatric context (3, 6, 9, 10), as well as in the inpatient and outpatient settings. Establishment of a trusting relationship is a core component of patient- and family-centered care and provides meaning and importance to the patient-physician relationship (1). Trust between adult patients and physicians has been defined as a physician acting as an advocate for the best interest of their patient, showing genuine concern, and treating their patients with respect and dignity (4). Trust is rooted in vulnerability and safety: the more vulnerable the patient, the higher the likelihood for either trust or mistrust (1, 4). When adult patients trust their physician, they feel less vulnerable, physicians feel more effective, and patient-physician communication quality increases (5, 7). When trust does not develop, or is eroded, patients and families can experience anxiety, frustration, second-guessing of key medical decisions, and broken patient-physician relationships, while physicians are unable to provide the optimal care that patients and their families need (6). Finally, in recent decades, where patient trust of both individual physicians and institutions has eroded, lower levels of trust present an impetus to ensure that patients receive clear communication and meaningful inclusion in decisions about their health (5, 7, 8).

In the pediatric healthcare context, trust has important nuances and implications for medical care. Development of trust in the pediatric setting is further complicated by the triadic relationship involving the child, parents/caregivers (herein referred to as parents) and physician (6). Sisk and Baker developed a model of interpersonal trust in pediatrics that posits that families initially trust physicians based on perceptions of competence but that trust increases when the physician demonstrates they are trustworthy through relationship-building (6). Physicians’ actions determine this relation-based trust as parents interpret the physicians’ actions in a continuous cycle. Other studies have endorsed the value of ongoing relationships in building and maintaining trust between physicians and parents (9, 10) as well as repairing and re-establishing trust in previously difficult relationships (11). Existing pediatric research has focused mainly on trust in the context of longitudinal outpatient relationships with primary care physicians or specialists (12, 13). Currently, medical literature does not include studies that explore the process of establishing trust between parents and physicians in the pediatric inpatient setting. The inpatient setting is less likely to include longitudinal patient-parent-physician relationships and may increase patients’ and parents’ stress and vulnerability; these setting-specific factors could produce fundamental differences in how trust is built between parents and pediatric physicians.

Children with Medical Complexity (CMC) are one of the fastest-growing inpatient populations in pediatrics (14). They have multiple chronic conditions, high health care utilization, and medical technology dependence (15). Similar to adult patients with chronic disease (16), parents of CMC expect trusting relationships with physicians ideally to be reciprocal, as opposed to the traditional view of the patient or parent as trustor and physician as trustee (2, 13, 17). In the setting of complex and chronic diseases, physicians are often compelled to place trust in the competence of patients/parents and the expertise they bring through their lived experiences. CMC are more likely than other patients to have experienced medical errors and uncertainty in management, including delayed diagnoses (18–20); all of these adverse experiences have the potential to erode trust (21, 22). For parents of CMC, physicians’ medical expertise may be insufficient to inspire implicit trust, since parents of patients with complex and/or rare diagnoses may have more condition-specific knowledge than do physicians (23–26). CMC also tend to experience frequent hospitalizations, which often involve discontinuous relationships with inpatient physicians, which may impact the ability of CMC and their parents to develop trust in physicians (27, 28).

The aim of this study was to investigate how parents of CMC conceptualize trust in the triadic parent-CMC-physician relationship in the inpatient setting. No studies to date have specifically explored the development of trust between parents of CMC and inpatient physicians. The needs and experiences of parents of CMC are unique and important due to their child's frequent hospitalizations, their own child-specific expertise, as well as historical and contextual factors that may prove challenging for trust formation. This study seeks to understand trust development in the inpatient setting from the perspective of parents of CMC, with the goal of enhancing understanding of how to promote trusting relationships between parents and physicians in general.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

We used interpretive description methodology to structure this study, which involved collection of firsthand accounts from parents of CMC about the factors that influenced their development of trust in their child's inpatient physicians (29, 30). Interpretive description is an inductive qualitative analytic approach that helps to understand human experiences that are both constructed and contextual in nature. This approach aids in the identification of patterns and themes within data and fosters development of broad understandings that can directly inform clinical practice (30). Another feature of this methodology is a heightened awareness of “outliers” which are perspectives that might otherwise be missed in a thematic analysis if mentioned by only one participant (31).

2.2 Setting and recruiting

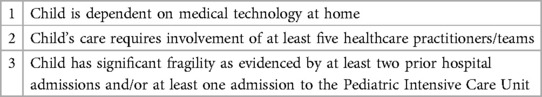

Parents of CMC who were hospitalized on inpatient care units at the Alberta Children's Hospital (ACH) were recruited to the study. Inpatient care units at the ACH are overnight units that do not include emergency care, intensive care, or oncology. All interviews were conducted in English. Parents of children who met all inclusion criteria for CMC, and were older than six months, were eligible to participate. The definition of CMC was adopted from Complex Care Kids Ontario in Table 1 (full criteria in Supplementary Material S1) (32).

Parents were recruited through a co-occurring prospective Research Ethics Board-approved study investigating the development of post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in parents of CMC (hereafter referred to as the PTSS Study). This study was conducted in an inpatient setting. Only parents who had completed the PTSS Study were recruited. (See Supplementary Material S2 for recruitment process for PTSS study). Parents’ responses demonstrated a range of scores on survey instruments completed for the PTSS Study including the Post-traumatic Stress Checklist and the Pediatric Trust in Physician Scale, reflecting a broad range of stress, trauma and trust levels. The scores on these surveys for the PTSS study were not a condition for inclusion in the Trust Study nor were they included in any analysis for the Trust Study. Forty-three parents consented to be contacted for future research and were invited to participate in this study (hereafter referred to as the Trust Study). Written consent was obtained at enrollment.

2.3 Data collection

Two senior researchers conducted one-on-one semi-structured virtual interviews with participants that lasted 45–60 min, scheduled between June 2022 and August 2023. Interviews for the Trust Study took place between 68 and 323 days after the CMC patient discharge date from the original PTSS Study. Using secure Zoom videoconferencing, interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed and redacted for identifying information.

A semi-structured interview guide was used for questioning (see Supplementary Materials S3). Participants were asked about: (a) their child's most recent hospitalization (where they enrolled in the PTSS study) and their level of trust with the physicians they encountered during that hospitalization; (b) previous positive and negative trust experiences when their child had been hospitalized prior to the most recent hospitalization; (c) advice they would give to physicians and also to other parents about building trust; (d) their reflections about whether physicians trust them.

The interviews approached the topic of inpatient physician trust with few preconceived notions, encouraging participants to talk about their views and experiences openly. “Inpatient physician” referred to any physician who was involved in the child's medical care while hospitalized, including post-graduate trainees (residents or fellows). While the interviewer asked participants to focus on their experiences when their child was hospitalized and comment on trust of inpatient physicians, participants sometimes related stories about community or emergency room physicians, or nurses, to give further examples or contextualize discussion. These comments were also incorporated into the thematic analysis.

Each senior researcher conducting the interviews was aware of their positionality, which refers to the identity of the researcher in relation to the participant, including personal characteristics such as gender and socioeconomic status as well as past experiences and context (33). Researchers reflected on potential biases that could affect data collection or interpretation. Both interviewers had experience conducting interviews with individuals who have medical complexity and/or disability. Interviewers attempted to make participants feel comfortable despite potential perceived power or knowledge differentials. The tone of these interviews was conversational to encourage participants to feel comfortable and open up about their parenting experiences and thoughts about trust. Interviewers incorporated breaks when needed and offered supportive and sympathetic words if participants became emotional. Participants were also reminded that they could choose to leave the study at any time without the need for explanation and could skip any questions that they felt uncomfortable answering.

Recruitment ended when all eligible parents had received an email invitation and reminder to participate. Interpretive description methodology cautions that assumptions about theoretical saturation should be made carefully. New perspectives and ideas could always arise with more data gathering; however, the research team felt confident that many of the same themes were being discussed in later interviews thus indicating a reasonable consistency within the accounts had been reached (29, 34).

2.4 Data analysis

Two senior researchers conducted the interviews and, along with the study's primary investigator (PI), created research memos from each interview. Analytic research memoing is a process of making sense and refining thoughts that develop into ideas as the researcher encounters the data (30). Memoing facilitates the organization of data, visualization of important connections, and conceptualization of themes (30, 30). A core analysis team, including the principal investigator, two senior researchers (who conducted the interviews), and a parent-partner then debriefed the interviews and memos. Creating research memos and continuously reflecting on the data coding process allowed researchers to develop comprehensive thematic groupings that stayed consistent with the participants’ data. Core analysis team members also brought different perspectives to these debriefing discussions, including clinical and personal experiences, that provided deeper understanding and guarded against researcher bias. Interpretive description methodology encourages researchers to practice reflexivity—researcher self-awareness and self-evaluation—during the research process. This practice encourages researchers to consciously examine their own biases and perspectives to prevent these biases from unduly influencing the research process (35).

A senior researcher conducted in-depth coding of all interviews with NVivo software. Two researchers inductively developed the initial coding scheme using the first five interviews. One researcher then completed the coding and continued to refine and apply the coding structure to the remaining transcripts. The core analysis team regularly reviewed the coding process as it evolved. This detailed inductive coding process allowed researchers to see a developing list of themes based on positive and negative practices that participants felt could help promote or inhibit triadic trust relationships with physicians (see Supplementary Materials S4).

All study participants were invited to participate in a member checking process where they were asked for feedback on a preliminary description of the themes. Five participants responded to the request with two supporting the thematic analysis as presented, and three providing further thoughtful comments that were incorporated into the final interpretive description analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Participant characteristics

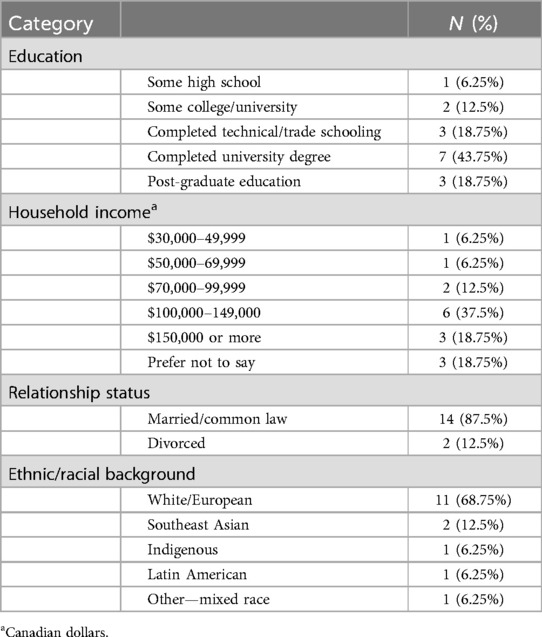

Sixteen parents of unique patients consented to participate in the study with an acceptance rate of 37%. Each participant also completed a short demographic survey before the interview. Thirteen female (81.25%) and three male (18.75%) parents of CMC (herein “parents” or “participants”) were interviewed with an average age of 39 years and a range of 26–57 years old. Table 2 summarizes the demographic features of participants.

3.2 Meta-theme: need for situational awareness and personalization of care

The themes derived from the multi-step analysis illustrate how to create a foundation for trust from the perspectives of parents of CMC. Factors that influence parent-physician trust span many important aspects of the physician-parent-child encounter and relationship. Trust is a fluid feature in relationships—it develops on a continuum that can deepen and strengthen with positive encounters or weaken or break with negative ones. Every parent was at a different stage of how trusting they could be with an inpatient physician or physicians in general. Throughout the interviews, parents spoke about an overarching theme: the need for situational awareness and personalization in building trust.

Evident as a running theme across of all the interviews was the need for physicians to have “situational awareness” to gain the trust of parents of CMC. Situational awareness can be viewed as a deliberate conscious knowledge of the different elements and circumstances in a clinical situation (36). From parents’ perspectives, this knowledge and understanding related to the child, the parent, their collective history, and the context of the clinical situation. To facilitate trust in these often highly challenging encounters, parents felt this knowledge must then be translated into a personalization of the physician's approach.

Pertaining to situational awareness, parents expected physicians to appreciate the unique, and often rare, nature of their child's condition. When parents were concerned that physicians were failing to incorporate this child-specific knowledge into their clinical decisions, this concern impeded the formation of trust.

“I think a lot of the failures that we've had is because it was a cookie cutter approach, applied to a situation that was way more complex. If you were just to breeze by it, you'd be like, ‘Oh, it’s just this.’ But if you actually took the time and you asked the right questions, you would not have applied a cookie cutter approach” (P11).

Some parents also pointed out that physicians need to tailor their interactions to children of different ages and stages, especially older or more mature children, to gain their trust.

“And what was better for [child name] based on her style, which is slow and steady, let her think about things. […] And if you say to her, ‘Well, should we do this today?’ Her first answer is, ‘No.’ So Dr. A figured her out pretty quick and asked what’s the best way to deal with her” (P7).

Parents of CMC had varied needs and desires relating to physicians, managing the healthcare encounter, and building trust. Although all parents wanted the focus to be directed to their child, some appreciated attention and acknowledgement from inpatient physicians relating to their own health, coping, and contributions.

“They'd ask about how work was or whatever […] just taking that extra little bit of time and discussing something else […] I mean, your brain, you're running on little to no sleep for periods of time. It’s not your best self, right there. So yeah, when they ask that, it definitely helps reduce stress. And it’s not just talking about your sick kid the whole time” (P5).

Some parents reported a need for inpatient physicians to understand the context of the clinical encounter to enable trust-building. Many parents recognized that they were often “not at their best” during these hospital admissions. They desired inpatient physicians to appreciate the effects of stress, burnout, sleep deprivation, and fear on their interactions. Other parents preferred to have the physician focus completely on their child's needs indicating that not all parents expected to have an emotional connection with the inpatient physician or care team.

“I don't tend to need emotional counseling from a physician just because that’s not what they're there for. That’s not what I need them for. If I'm upset about [child name], I have my wife, I have other supports that I'll rely on” (P6).

There was variability in how parents of CMC felt that communication between parent and physicians ought to take place. For example, some parents in this study acknowledged their own expertise as “medical moms and dads” and felt that they should be treated differently than parents of non-CMC.

“I had never met him before this. So yeah, he kind of picked up right away that I was a more medical mom and that he could use more jargon with me and that he could speak more freely. I've not seen him talk to other patients, obviously, but I liked that” (P9).

Many parents in this study felt that inpatient physicians’ ability to tailor communication to meet their needs and preferences was integral to building trust and supporting the parent-physician relationship. One parent related how a simple but effective communication tool was helpful in promoting trust for her:

“I really liked […] the board on the wall, which has opportunities for parents to write things. And doctors will come in, they'll put their name for the day, here’s our goal, here’s what we need to accomplish today […] and sees, ‘Oh, this parent has left me something. They've got a question.’ Or they said, ‘Hey, this thing needs to still be done. Don't forget.’ I think that those are also ways to show, ‘I trust you by sharing this knowledge and hopefully you trust me back by sharing more knowledge’” (P16).

Many parents of CMC revealed how specific past experiences—particularly negative experiences and trauma—influenced their ability to be trusting. Events such as medical errors, missed diagnoses, and hurtful or unsafe past experiences clearly hindered trust development. Some parents also referenced these past events to justify their own approaches and behaviours in the clinical encounter.

“To be perfectly honest, ever since [child name]’s been born, doctors have messed things up. So, I always have that underlying. I'm always very clear and I repeat things several times and I'm always asking questions. I'm not like that chill mom, that’s just like, ‘Oh, they're going to do their job.’ I feel like I have to be on it all the time. […] Because there’s been a lot of things that have been missed over the past two years” (P11).

A few parents felt obligated to never leave their child's side during hospitalization because of previous medical errors, concern for their child, or perceived neglect of their child.

Finally, some parents of CMC reported the importance of developing their own situational awareness about the hospital environment, including system-specific factors such as the constraints of the hospital environment and inpatient physicians’ working conditions, as well as more person-specific factors such as inpatient physicians’ individual stressors and personality traits. During the interviews, several parents reflected about their own role and behaviour at the hospital. One parent suggested treating the hospital “like a workplace” by showing respect for staff and for the hospital environment (P9); another parent acknowledged that the health care providers caring for children are also under a lot of stress.

“We treat our team as humans, not just as somebody there in a medical role. You know, we make sure that we're really conscious to pay attention to names…you know, to speak, and to talk kindly, to listen too, and remember that every single one of our medical team has a family or a partner that they go home to every night” (P10).

3.3 Summary of themes

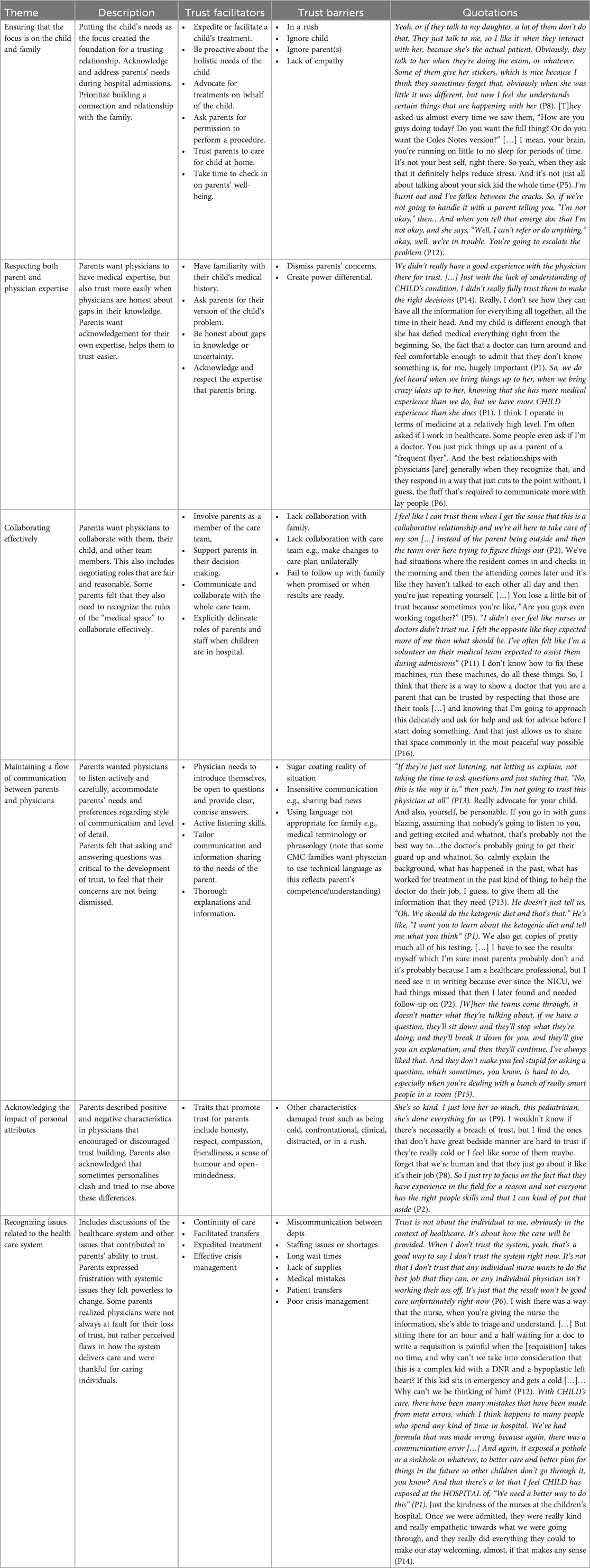

In addition to the overarching theme for the need for situational awareness and personalization of care, responses from parents evoked six themes that relate to trust development, which are outlined in Table 3 along with illustrative quotations.

3.3.1 Theme #1: ensuring that the focus is on the child and family

All parents in the study wanted their child's needs to be the central focus during hospitalization. In addition, many parents felt that forming trust also required that physicians (whether inpatient or outpatient physicians) acknowledged and gained understanding of the needs and experiences of parents themselves. However, not all parents of CMC felt that they needed this acknowledgement or attention from inpatient physicians to develop trust. This approach, focused on the child and family, was supported when physicians prioritized building a connection, an undertaking that was made easier if there was continuity of care. Parents valued continuous relationships with physicians across encounters as this continuity facilitated awareness, familiarity and understanding of the child and parent.

3.3.2 Theme #2: respecting both parent and physician expertise

In the therapeutic encounter, physicians bring medical expertise and parents bring child-specific expertise. Parents feel that both need to be respected in order for trust to develop. Parents described how they had a baseline level of trust for all physicians given their medical knowledge and training, but this was sometimes called into question when inpatient physicians lacked knowledge about their child's complex and/or rare condition. In other instances, medical mistakes or disagreements over treatment plans also caused parents to doubt physician knowledge and expertise. Paradoxically, many participants felt they trusted more easily when a physician was honest about their level of knowledge or admitted gaps in their understanding. Parents also brought considerable hard-won expertise from their own inquiry, day-to-day care of their child, and repeated hospitalizations. Some parents felt that this intimate and experience-based understanding of their child made them different from parents who do not have CMC. Every participant reported that when physicians acknowledged and respected parents’ expertise about their child, they were able to feel more trusting towards inpatient physicians.

3.3.3 Theme #3: collaborating effectively

Parents indicated that the ability to collaborate effectively was another key element for building trust with inpatient physicians. When physicians took an inclusive approach to providing medical care with emphasis on shared decision-making with parents of CMC (as well as CMC themselves when maturity and cognitive ability allowed), parents felt that their expertise was validated by physicians and that this practice supported trust-building. However, some parents pointed out that the stress of decision-making and negotiating the various roles needed to care for a child in hospital can cause friction or misunderstanding; effective collaboration must include clarifying these roles and expectations between parents of CMC and an interdisciplinary medical team. Some parents felt that the medical teams’ expectations of them were excessive, unreasonable or unsupportive. Parents also expected physicians to collaborate effectively with others (including trainees, nurses and other physicians); when this collaboration did not happen, trust was negatively impacted. One participant pointed out that parents also need to be respectful and cognizant of medical spaces that have their own rules, to be able to collaborate effectively with the child's medical team.

3.3.4 Theme #4: maintaining a flow of communication

Another consistent message from parents was that maintaining a flow of communication is central to developing trust with inpatient physicians. Many participants felt that active listening skills were critical as parents had experienced not being heard when their child was hospitalized. Parents appreciated when physicians accommodated parents’ preferred communication style (e.g., written, verbal, and diagrammatic) and need for information. Many parents spoke about the importance of being able to ask questions of their child's inpatient physicians and their appreciation of being invited to do so. When physicians encouraged parents to ask questions, parents believed that their concerns would be thoughtfully addressed. Parents also pointed out that non-verbal cues, such as sitting down as a signal of not being in a rush, can promote trust. Some participants acknowledged that how parents communicate is also very important, can affect how successful they will be in advocating for their child, and can influence whether inpatient physicians trust parents of CMC.

3.3.5 Theme #5: acknowledging the impact of personal attributes

Parents of CMC recognized the impact of personal attributes and felt that building trust was easier with inpatient physicians who had characteristics such as honesty, compassion, open-mindedness, friendliness, and humor. Sharing personal stories also helped to “humanize” physicians, allowing parents to trust these physicians more easily. Parents also identified characteristics that discouraged the formation of trust and described these inpatient physicians as “cold,” “distracted,” or “rushed,” or as having a more “clinical” approach.” Parents acknowledged that sometimes personalities clash and that “no one is perfect.” Some parents were understanding that inpatient physicians experience stressors that can test their ability to be positive or kind. These parents were willing to accept that inpatient physicians are “doing their best” and felt that this attitude was helpful in trust-formation.

Many parents in the study reflected on the impact of their own personal traits on the trust-building process. For example, parents of CMC exhibited variable levels of confidence in terms of how they navigate hospitalizations with their child. Confidence affected whether a parent asked for a second opinion, reported disrespectful treatment from a physician, or could recover from a broken trust experience. Some parents were fiercely proud of being tough “medical moms” who kept meticulous track of their child's medical history and had lived through medical trauma. Other parents were worried that their stress responses could result in them being labeled as difficult, using words like “crazy” to describe themselves. Finally, several parents pointed out the importance of being “personable” and calm when advocating for their child.

3.3.6 Theme #6: recognizing issues related to the healthcare system

Parents of CMC asserted that issues related to the healthcare system affected trust development in the inpatient setting, with some factors being conducive to trust-building and others having a detrimental effect on this process. Systemic shortcomings such as staffing issues, lack of equipment, suboptimal crisis management (e.g., during Covid-19 pandemic), and inefficient interactions between departments (e.g., when patients are transferred from one unit to another) were the kinds of issues that resulted in a loss of trust in the “system” and those employed within it. Some parents pointed out gaps in family and parent services in the pediatric healthcare system (e.g., lack of availability of parent mental health support during hospitalization) and how these shortcomings could also decrease trust in the system. Parents also recognized that many of the systemic issues that affect parent-physician trust are difficult to fix. Although many participants shared their frustrations with the healthcare system, they also offered suggestions for how to improve it.

4 Discussion

4.1 Trust as an outcome of patient- and family-centered care

This study revealed numerous themes that are critical to relationship-building and trust-building between parents of CMC and their child's inpatient physicians. Parents felt that parent-physician trust-building in the inpatient setting required that the physician demonstrate a clear focus on the child and family as well as good communication skills. They also desired respect for their own expertise alongside the respect they felt for the physician's knowledge and experience. Collaboration between parents and all members of the inpatient healthcare team, evidenced by mutual respect and role negotiation, helped establish parental trust in inpatient physicians. Parents appreciated that certain characteristics and behaviours of themselves and inpatient physicians could facilitate or hinder the development of trust; understanding these differences allowed some parents to tolerate some traits and behaviors that otherwise might have impaired the relationship. Finally, systemic factors also influenced the trust that developed between parents and physicians.

These elements of trust-building are reflected in other pediatric populations and settings. Notably, a study by De Lemos et al. (27) also emphasized several parent-identified trust facilitators, including physician communication (clarity and frequency), collaboration both with parents and within the healthcare team, and parental involvement in decision-making (27). However, in that study's broad population of children with acute and chronic conditions, the need to integrate parent and physician expertise and to develop situational awareness were not identified as important facilitators. In a study on one subpopulation of CMC, children with Trisomy 13 and Trisomy 18 (also CMC), Janvier et al. discuss the need for personalization (23). In Janvier et al's study, personalization of information to the child and respecting different decision-making preferences was a key theme in the facilitation of trust. Although not specific to trust, a study in a pediatric oncology population (11) identified problems with connection and understanding as a core issue in difficult therapeutic relationships with low levels of trust.

Many of these themes align strongly with the principles of patient- and family-centered care (PFCC). PFCC is an approach to the planning, delivery and evaluation of healthcare that is grounded in collaboration and partnership with patients, families, and healthcare providers, recognizing the centrality of family in a child's life (37). The core concepts of PFCC that matched the major themes of trust-building that we identified in this study include: (a) Respect and Dignity (listening to patient and family perspectives and incorporating these perspectives into management); (b) Information sharing (sharing information that is timely and accurate); (c) Participation (shared decision-making); and (d) Collaboration (among patients, families, healthcare providers and leaders) (38, 39). Since adherence to these principles is endorsed as a means of facilitating the provision of high-quality care, it is not surprising that parents also identified these as critical to developing trust with physicians. Our findings reinforce and expand upon the value of the PFCC principles by emphasizing their role in developing trusting relationships between parents of CMC and inpatient physicians. Trust, one might say, is an outcome of applying PFCC.

Parents of CMC hold essential knowledge and expertise in their child's condition, their history, and unique insights into the care of their child. Learned via day-to-day experience, this parental expertise is inherently different from that of physicians and is especially valuable to the medical care of their child. This child-specific knowledge allows parents to collaborate at a different level than parents who are naïve to the healthcare system or whose children have conditions with clear diagnoses and management guidelines. At the same time, this personal experience often includes traumatic experiences in healthcare, including occasions of broken trust and medical errors, which may impact their ability to form trust in future therapeutic relationships. Several parents shared how many aspects of caring for their child can also be very traumatizing, such as performing painful medical procedures (P9), witnessing painful procedures when their child is hospitalized (P1, P2, P4, P5, P13), dealing with unexpected diagnoses (all participants), or facing life-or-death decisions about their child (P1, P3, P4, P13). Other studies have also shown that this intensity of involvement in the inpatient setting comes with high levels of pressure and responsibility for parents (40, 41). Considering that CMC can be amongst the most challenging of patient populations (42), it follows that families of CMC might also be most in need of PFCC. Inpatient physicians can better treat CMC and support their parents by navigating the line between necessary parental involvement and overwhelming parental responsibility when their child is hospitalized.

Many examples from the research interviews in this study illustrate how parents of CMC highly value the concepts inherent to PFCC. The needs of CMC patients and families also illustrate the benefits of PFCC. For example, information needs to not just be “shared”; rather communication needs to be precise, considerate, and transparent. For CMC and their parents, patient- and family-centered communication requires that physicians know how best to interact with a child with severe developmental delays, to prepare children and families emotionally for difficult or painful procedures, and to discuss decisions with life-and-death implications respectfully with CMC and their parents. Combining the concept of PFCC with an individualized care approach ensures that inpatient physicians do not make assumptions about parents of CMCs’ skills and feelings. Providing PFCC improves the likelihood that all patients and families receive individualized management in an environment that facilitates trust-building with their physicians.

4.2 Critical trust and the guarded alliance

One could posit that building trust between physicians and CMC and their parents is an undisputed requirement for optimal management of medical problems. Even so, for parents of CMC to have implicit trust in inpatient physicians may not be in the child's best interest. In this study, most parents of CMC approached trust as something to be earned and reciprocated. Parents were often wary of relationships with new physicians, whether because of past negative experiences or their need to be vigilant about their child's medical care. Parents of CMC also operate within a system where lower levels of trust and higher expectations for patient-centered care are increasingly the norm (7, 8). Thorne and Robinson coined the term “guarded alliance” to describe the final stage of trust development amongst patients with chronic illness, their families, and healthcare providers (43). In their study on adults with chronic illness, Thorne and Robinson described three stages of how trust evolves over time: naïve trust, disenchantment, and guarded alliance (43). In the last stage, patients had various reactions to their positive or negative healthcare experiences that shaped their ability to trust—ranging from hero worship, to resignation, to consumerism, to team playing. The latter, most beneficial outcome is a healthcare provider-patient relationship based on reciprocal trust (16). Parents of CMC also exhibited many different stages of trust. Similar to Thorne and Robinson's paper, most parents felt that their definition of trust required both parties—inpatient physicians and parents of CMC—to work towards establishing a trusting therapeutic relationship. Parents of CMC felt that inpatient physicians that take the time to understand parents’ past experiences, acknowledge parents’ struggles, and trust parents’ perspectives demonstrate their trustworthiness by showing care and respect for parents. Parents of CMC who can acknowledge (and forgive) inpatient physician fallibility were better at building trust and demonstrated a sense of self-awareness regarding whether they were trustworthy themselves.

4.3 Personalizing care to build trust

Importantly, parents of CMC did not have identical perspectives on trust-facilitating approaches which is captured in the overarching meta-theme of situational awareness and personalization of care. The concept of “personalized care” is complementary but distinct to that of “personalized medicine.” The latter focuses on screening, prevention, and treatment plans that are tailored to an individual's biological or environmental risk factors (44). In contrast, personalization of care (45, 46) reflects the control patients can exert over the way their care is delivered. This concept overlaps with the tenets of PFCC (incorporation of the patient's and family's preferences and values) and culturally competent care (consideration of the patient's and family's culture and preferred language). For the parents of CMC in this study, the concept of personalized care was expanded to include situational awareness, which incorporated historical, situational, and systemic considerations. In essence, situational awareness in the clinical encounter implies gathering thorough information about the child and their family, using this information to interpret or predict their needs, and incorporating this information into the health care provider's approach (47).

One novel concept that we uncovered through this study was that personalization of care involves not only incorporating patient values into a medical decision or plan of treatment but also adapting the therapeutic relationship itself to meet the individual needs of patients and families. This practice can be challenging for physicians, who are often taught standardized and translatable skills that can be used across clinical encounters (48, 49). Although training in specific skills undoubtedly has an important place in the practice of medicine, a standardized and rigid approach is likely not sufficient for working with CMC and their parents. Instead of a “best practice” for building trust with CMC and their parents, physicians must assume a position of flexibility and incorporate an individualized approach for each unique patient and family. By incorporating awareness of critical elements (such as patients’ and parents’ preferences for support and communication, and recognition of traumatic stress related to previous experiences in medicine), physicians have the best chance of achieving trust and the guarded alliance.

5 Limitations

Convenience sampling recruited participants from a separate study addressing post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in parents of CMC. Participants in the PTSS Study were not limited to those who had experienced PTSS. Thus, this recruitment strategy was not expected to significantly influence the outcomes of this study. Within a qualitative study, we cannot account for differences in important demographic and clinical characteristics among participants (such as child age, number of previous admissions and language preferences). As such, these results may not be generalizable to all hospitalized CMC. Significant inter-relatedness in content was found between interviews, but these data still may not represent the full breadth of experience of the diverse population of hospitalized CMC and their parents. The study sample was also not demographically diverse as participants were mostly white, wealthy, female, married, English-speaking and Canadian. Although the interviews asked directly about experiences with inpatient physicians, some participants shared experiences from other settings and with other types of professionals. For example, participants mentioned interactions in the emergency department or with a medical trainee or nurse. Although these topics are outside the scope of this study, we felt it was important to allow participants to share these events, which were obviously very significant to them. These comments were not explicitly excluded from our analysis and could thereby have influenced our results.

6 Conclusion

This study provided a qualitative examination of trust development between parents of CMC and inpatient physicians using a methodology that focused on practical applications and translation into “real world” clinical encounters. Physicians require sophisticated skills in order to tailor their clinical approach to meet the needs of each CMC and their family; the physician must be able to personalize their communication style, decision-making, and support so that it is appropriate for each unique scenario. Directed training for physicians and medical trainees would include how to implement trust-building behaviours, suggested by study participants, within the six themes related to trust development (Table 3) such as expediting treatment for CMC, taking time to check on parents’ well-being, being honest about gaps in knowledge, delineating care roles between parents of CMC and medical team, tailoring communication for parents of CMC, and managing crises promptly. This study raised several issues that warrant further study including the challenge of mending broken trust, which represents a particularly noteworthy opportunity for improvement given that every parent of CMC in this study reported a previous instance of compromised trust. In their model of interpersonal trust in pediatrics, Sisk and Baker point out that rebuilding broken trust is difficult and uncomfortable for physicians, requiring skills in conflict resolution and specialized communications training (6). A second phase of this study is ongoing and is focused on physicians’ perspectives, which may provide further insight into the strategies that facilitate the development of physician-patient-parent trust. Triangulation of this study with the physician study will support the development of a toolkit that physicians can use as they work to build trust with CMC and their parents.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TD: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AW: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. LM: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RM: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. MN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. CB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – review & editing. IJ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AJ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ST: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research team was awarded funding from Norman Saunders Complex Care Initiative at the Hospital for Sick Children Foundation in Toronto, ON, Canada.

Acknowledgments

The research team wishes to acknowledge the contributions and expertise of the parents who participated in this study and the generous support of funding through the Norman Saunders Complex Care Initiative.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2024.1443869/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ACH, Alberta Children's Hospital; CMC, children with medical complexity; PFCC, patient- and family-centered care; PTSS, post-traumatic stress symptoms.

References

1. Hall M, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra A. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured and does it matter? Milbank Q. (2001) 79(4):613–39. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223

2. Robinson CA. Trust, health care relationships, and chronic illness: a theoretical coalescence. Glob Qual Nurs Res. (2016) 3:2333393616664823. doi: 10.1177/2333393616664823

3. Swedlund MP, Schumacher JB, Young HN, Cox ED. Effective communication style and physician-family relationships on satisfaction with pediatric chronic disease care. Health Commun. (2011) 27(5):498–505. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.616632

4. Hillen MA, de Haes HCJM, Smets EMA. Cancer patients’ trust in their physician—a review. Psychooncology. (2011) 20(3):227–41. doi: 10.1002/pon.1745

5. Lee TH, McGlynn EA, Safran DG. A framework for increasing trust between patients and the organizations that care for them. JAMA. (2019) 321(6):539–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19186

6. Sisk B, Baker JN. A model of interpersonal trust, credibility, and relationship maintenance. Pediatrics. (2019) 144(6):e20191319. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1319

7. Rowe R, Calnan M. Trust relations in health care–the new agenda. Eur J Public Health. (2006) 16(1):4–6. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl004

8. Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Hero JO. Public trust in physicians–U.S. medicine in international perspective. N Engl J Med. (2014) 371(17):1570–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1407373

9. MacKay L, Benzies K, Raffin Bouchal S, Barnard C. Parental and health care professionals’ experiences caring for medically fragile infants on pediatric inpatient units. Child Health Care. (2021) 51(2):119–38. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2021.1973900

10. Horn IB, Mitchell SJ, Wang J, Joseph JG, Wissow LS. African-American parents’ trust in their child’s primary care provider. Acad Pediatr. (2012) 12(5):399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.06.003

11. Mack JW, Kang TI. Care experiences that foster trust between parents and physicians of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2020) 67(11):e28399. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28399

12. Moseley KL, Clark SJ, Gebremariam A, Sternthal MJ, Kemper AR. Parents’ trust in their child’s physician: using an adapted trust in physician scale. Ambul Pediatr. (2006) 6(1):58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2005.08.001

13. Gregory ME, Nyein LP, Scarborough S, Huerta TR, McAlearney AS. Examining the dimensionality of trust in the inpatient setting: exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. J Gen Intern Med. (2021) 37(5):1108–14. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06928-w

14. Berry JG, Hall M, Neff J, Goodman D, Cohen E, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity and medicaid: spending and cost savings. Health Aff. (2014) 33(12):2199–206. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0828

15. Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Bhagat SKM, Simon TD, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. (2011) 127(3):529–38. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0910

16. Thorne SE, Robinson CA. Reciprocal trust in health care relationships. J Adv Nurs. (1988) 13(6):782–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1988.tb00570.x

17. Gómez-Zúñiga B, Pulido Moyano R, Pousada Fernández M, García Oliva A, Armayones Ruiz M. The experience of parents of children with rare diseases when communicating with healthcare professionals: towards an integrative theory of trust. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2019) 14(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1134-1

18. Matlow AG, Baker GR, Flintoft V, Cochrane D, Coffey M, Cohen E, et al. Adverse events among children in Canadian hospitals: the Canadian paediatric adverse events study. Cmaj. (2012) 184(13):E709–18. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.112153

19. Stockwell DC, Landrigan CP, Toomey SL, Loren SS, Jang J, Quinn JA, et al. Adverse events in hospitalized pediatric patients. Pediatrics. (2018) 142(2):e20173360. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3360

20. Blaine K, Wright J, Pinkham A, O'Neill M, Wilkerson S, Rogers J, et al. Medication order errors at hospital admission among children with medical complexity. J Patient Saf. (2022) 18(1):e156–62. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000719

21. Anderson M, Elliott EJ, Zurynski YA. Australian families living with rare disease: experiences of diagnosis, health services use and needs for psychosocial support. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2013) 8:22. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-22

22. Baumbusch J, Mayer S, Sloan-Yip I. Alone in a crowd? Parents of children with rare diseases’ experiences of navigating the healthcare system. J Genet Couns. (2019) 28(1):80–90. doi: 10.1007/s10897-018-0294-9

23. Janvier A, Farlow B, Barrington KJ, Bourque CJ, Brazg T, Wilfond B. Building trust and improving communication with parents of children with trisomy 13 and 18: a mixed-methods study. Palliat Med. (2020) 34(6):262–71. doi: 10.1177/0269216319860662

24. Currie G, Szabo J. ‘It would be much easier if we were just quiet and disappeared’: parents silenced in the experience of caring for children with rare diseases. Health Expect. (2019) 22(6):1251–9. doi: 10.1111/hex.12958

25. Bogetz JF, Trowbridge A, Lewis H, Shipman KJ, Jonas D, Hauer J, et al. Parents are the experts: a qualitative study of the experiences of parents of children with severe neurological impairment during decision-making. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2021) 62(6):1117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.06.011

26. de Geeter KI, Poppes P, Vlaskamp C. Parents as experts: the position of parents of children with profound multiple disabilities. Child Care Health Dev. (2002) 28(6):443–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00294.x

27. DeLemos D, Chen M, Romer A, Brydon K, Kastner K, Anthony B, et al. Building trust through communication in the intensive care unit: HICCC. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2010) 11(3):378–84. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b8088b

28. Blödt S, Müller-Nordhorn J, Seifert G, Holmberg C. Trust, medical expertise and humaneness: a qualitative study on people with cancer’ satisfaction with medical care. Health Expect. (2021) 24(2):317–26. doi: 10.1111/hex.13171

29. Thorne S. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice. New York, NY: Routledge (2016).

30. Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O'Flynn-Magee K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int J Qual Methods. (2004) 3(1):1–1. doi: 10.1177/160940690400300101

31. McPherson G, Thorne S. Exploiting exceptions to enhance interpretive qualitative health research: insights from a study of cancer communication. Int J Qual Methods. (2006) 5(2):73–86. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500210

32. Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health. (2019). Available online at: https://www.pcmch.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/NEW-Updated-CCKO-operational-definition-Jan-2019.pdf (Accessed September 16, 2024).

33. Bayeck RY. Positionality: the interplay of space, context and identity. Int J Quale Methods. (2022) 21:16094069221114745. doi: 10.1177/16094069221114745

34. Thorne S. The great saturation debate: what the “S word” means and doesn’t mean in qualitative research reporting. CJNR. (2020) 52(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/0844562119898554

35. Berge R. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res. (2015) 15(2):219–34. doi: 10.1177/1468794112468475

36. Feller S, Feller L, Bhayat A, Feller G, Khammissa RAG, Vally ZI. Situational awareness in the context of clinical practice. Healthcare (Basel). (2023) 11(23):3098. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11233098

37. Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. (2012) 129(2):394–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084

38. Park M, Giap TT, Lee M, Jeong H, Jeong M, Go Y. Patient- and family-centered care interventions for improving the quality of health care: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. (2018) 87:69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.07.006

39. Johnson BH, Abraham MR. Partnering with Patients, Residents, and Families: A Resource for Leaders of Hospitals, Ambulatory Care Settings, and Long-Term Care Communities. Bethesda, MD: Institute for Patient-and Family-Centered Care (2012). doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-063619

40. Page BF, Hinton L, Harrop E, Vincent C. The challenges of caring for children who require complex medical care at home: ‘the go between for everyone is the parent and as the parent that’s an awful lot of responsibility’. Health Expect. (2020) 23(5):1144–54. doi: 10.1111/hex.13092

41. Spiers G, Beresford B. “It goes against the grain”: a qualitative study of the experiences of parents’ administering distressing health-care procedures for their child at home. Health Expect. (2017) 20(5):920–8. doi: 10.1111/hex.12532

42. Russell CJ, Simon TD. Care of children with medical complexity in the hospital setting. Pediatr Ann. (2014) 43(7):e157–62. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20140619-09

43. Thorne SE, Robinson CA. Guarded alliance: health care relationships in chronic illness. Image J Nurs Sch. (1989) 21(3):153–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1989.tb00122.x

44. Park M, Lasko P, Tamblyn R. Canadian Institutes of Health Research Personalized Medicine Signature Initiative 2010–2013. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institutes of Health Research (2014). Available online at: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/irsc-cihr/MR4-21-2013-eng.pdf

45. Personalised Care Institute. (2024). Available online at: https://www.personalisedcareinstitute.org.uk/what-is-personalised-care-2/ (Accessed September 16, 2024).

46. Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, Ryan S, Shepperd S, Perera R. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 2015(3):CD010523. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010523.pub2

47. Toner ES. Creating situational awareness: a systems approach. In: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, editor. Medical Surge Capacity: Workshop Summary. Washington: National Academies Press (2009). p. 123–33.

48. King A, Hoppe RB. “Best practice” for patient-centered communication: a narrative review. J Grad Med Educ. (2013) 5(3):385–93. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00072.1

Keywords: trust, medical complexity, parents, relationship, patient- and family-centered care, physician, hospital, pediatrics

Citation: Dewan T, Whiteley A, MacKay LJ, Martens R, Noel M, Barnard C, Jordan I, Janvier A and Thorne S (2024) Trust of inpatient physicians among parents of children with medical complexity: a qualitative study. Front. Pediatr. 12:1443869. doi: 10.3389/fped.2024.1443869

Received: 4 June 2024; Accepted: 30 August 2024;

Published: 27 September 2024.

Edited by:

Joe Kossowsky, Boston Children's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United StatesReviewed by:

J. Carolyn Graff, University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC), United StatesDavid Rappaport, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, United States Mariah Burch, Emory University School of Medicine, United States, in collaboration with reviewer DR

Copyright: © 2024 Dewan, Whiteley, Mackay, Martens, Noel, Barnard, Jordan, Janvier and Thorne. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tammie Dewan, dGFtbWllLmRld2FuQHVjYWxnYXJ5LmNh

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Tammie Dewan

Tammie Dewan Andrea Whiteley

Andrea Whiteley Lyndsay Jerusha MacKay

Lyndsay Jerusha MacKay Rachel Martens

Rachel Martens Melanie Noel

Melanie Noel Chantelle Barnard1,2

Chantelle Barnard1,2 Isabel Jordan

Isabel Jordan