94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Pediatr., 05 September 2024

Sec. Neonatology

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2024.1425320

This article is part of the Research TopicWhat is new on the Horizon in Neonatology? Recent Advances in Monitoring, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics in Neonatal CareView all 21 articles

Objective: To better understand the experience of parents with neonates with congenital heart diseases (CHD) admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in order to identify challenges faced by parents and discover support strategies helpful in positive coping.

Study design: Prospective cohort study of parents of neonates with CHD. Parents completed a questionnaire with open ended questions regarding their experience and feeling during the hospitalization within one week of the child discharge from the NICU. Krippendorff's content analysis was used to examine data.

Results: Sixty-four parents participated. Three themes were highlighted – Dialectical parental experiences, Suboptimal Parental Experiences and Positive Parental Experiences – describing the state of being and feelings that these parents face. Through this analysis, we were able to develop clinical considerations and identify coping strategies.

Conclusion: The understanding of parental experience and challenges when dealing with their child admitted in the NICU is crucial to identify coping strategies to promote adaptation and enhance the development of positive coping mechanisms.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most frequent type of congenital anomaly accounting for nearly 1 percent of births annually in the United States (1); these may vary in degree of complexity, and depending on the type of malformation, the defect may require immediate medical and/or surgical intervention or a later treatment or sometimes, no treatment is needed, only follow-up is required. However, for most children born with CHD, lifelong monitoring will be required (1). Among other anomalies, CHD has the highest mortality rate, results in the longest hospital stay and subsequent frequent and prolonged hospital visits (2). These are the main explanations behind the unique and well-known psychological health pattern of parents of children with CHD (3). Despite the knowledge that all new parents can be subject to psychological distress (4), parents of babies admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) are known to experience higher levels of stress and an altered parent-child relationships (5–9). Moreover, parents of infants with CHD admitted to Intensive Care Units (10, 11) report experiencing anxiety, stress, and post-traumatic stress disorder present from diagnosis and persistent throughout the entire course of hospitalization (12) regardless of the severity of the heart condition itself (10, 13). Numerous studies have shown that the psychological profile, often referred to as the “emotional rollercoaster”, of parents of children with CHD – depression, anxiety, somatization, hopelessness, guilt, fear, poor quality of life, hypervigilant – is a chronic state, which persists over time (12–16). Impaired parental mental health, if not properly treated, can negatively affect parents’ ability to care for their children and can eventually result in long-term cognitive, health, and behavioral problems in offspring (10, 14, 17, 18). Given the incidence of CHD, psychological distress affects a relatively large number of parents, and can lead to deterioration of the parent-child relationship. However, it has been shown that this increasingly present and persistent challenge in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) can be lessened by the introduction of early palliative care (PC) (11, 19).

Early PC interventions can decrease parental stress, reducing some of the unmet needs of parents and of the whole family while increasing the comfort of the newborn (19–22) but still there is a need to identify specific challenges and coping support mechanisms for parents of neonates with CHD.

The aim of this study were to better understand the experience of parents with neonates affected by CHD and admitted to the NICU in order to identify challenges faced by parents and discover support strategies helpful in positive coping.

The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) checklist was referenced to promote complete and transparent reporting, with an aim to improve rigor and comprehensiveness of the data analysis. While COREQ is specific to interviews and focus groups, and our data were retrieved via a written survey, only select items from the COREQ checklist were addressed as applicable (23).

This is a prospective cohort study of mothers and fathers of neonates with congenital heart disease admitted to the NICU at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) from June 2017 to May 2018. Parents of neonates transferred from other institutions, who did not speak English, or whose neonate was diagnosed with a life-limiting condition or died during the admission were excluded from the study. Approval was obtained by the CUIMC Institutional Review Board (Protocol #AAAR3403).

Parents – both elements of the couple could participate – underwent written informed consent and those who wished to participate received a printed questionnaire asking for demographic information and three open ended questions within one week of infant discharge from the NICU. An initial global question was presented to encourage parents to express their overarching experiences: “What is it like for you to have a child in the NICU?” This item was followed with two additional questions as follows: “What have been the hardest parts of this experience for you?” and “What has helped you cope with having a child in the NICU?”

Krippendorff's content analysis was used to examine data, which is a research technique for the objective and systematic description of the content communicated by participants. Content analysis is context sensitive, allowing the researchers to process data texts that are significant, meaningful, informative and representational to others (24, 25). A strength of content analysis is the opportunity to increase our understanding of phenomena, in this case experiences of parents who have a neonate with a CHD in the NICU. To start, each author worked independently to examine the qualitative content for each of the three research questions. A systematic approach was used in which all authors separately mapped patterns of co-occurring words to identify clusters of common meanings. Author CW then examined the manifest data and fully quantified and coded the textual materials. Figure 1 provides examples of the analyses processes from the original data, known as manifest content, to latent meaning of the data.

These steps were followed by a meeting of all authors in which individual results were compared. A total of three themes emerged and were agreed upon. Six categories were identified by the team members, all of which were identically matched. Authors RS and CW were responsible for cross-tabulating and reexamining the data. During this meeting two additional categories were identified [Mixed and sensory] and two of the originally identified categories were merged [Gratefulness merged into positive parental feelings]. Therefore, three themes and seven distinct categories were identified. The codes within each category were carefully reexamined and when appropriate, were moved to the respective category. The entire team then verified and confirmed the final organization of the data.

A goal of the research team was to create practical clinical applications for the reader if the data support it. As such, the qualitative analysis and responses to the question “What has helped you cope with having a child in the NICU?” will be examined in order to identify specific concerns and needs of parents.

The parents of 44 neonates fulfilled the inclusion criteria. From that, 77 parents consented to participate, and, 64 (83%) submitted a written response. Demographic data are reported in Table 1 and the results are summarized in Table 2.

Parents reported a variety of dialectical experiences when responding to “What is it like for you to have a child in the NICU?” And to “What have been the hardest parts of this experience for you?”. Parents face mixed emotions including happiness over small milestones, awareness and acceptance of their baby's clinical situation, stress, hope and uncertainty.

The psychosocial stressors parents articulated were often paired with positive factors. Several parents noted how their infant's recovery process offset their negative emotions. One parent stated:

“It was quite an emotional rollercoaster. Hands down, the scariest situation I’ve ever been in. It was definitely a battle between staying strong and positive vs. being “realistic” and thinking of the worst. At the same time, it was incredible watching my baby improve/recover.”

and

“Mixed feelings. We are so thankful and happy that our baby made it this far. So, in some ways we are happy to be in a weird and stressful situation”.

The psychosocial stressors parents articulated were often paired with other variables. Parents acknowledged their experiences as “difficult”, “stressful”, “emotionally exhausting and traumatic”, while recognizing their infant was “well taken care of” and pointing out staff attributes, including clinicians’ dedication, experience and knowledge.

“Definitely scary but overall given the circumstances, excellent experience. Felt reassured that we were getting world class care where everyone genuinely cared for the well being of the patient.”

A sense of practicality was also present as parents noted the need to have their infant in the NICU.

“It was a difficult situation. On one side of the equation, I know this was the best place for him to be. A place where he could be monitored and was in the hands of experienced nurses. Yet on the other side of the equation are feelings which caused me to worry.”

Parents reported a variety of suboptimal experiences when responding to “What have been the hardest parts of this experience for you?” The data reported here are culled from this question as well as the first overarching question. Stressors stemmed from several feelings, including sensory encounters and the struggle to balance the demands of an infant in the NICU with other life responsibilities.

Uncertainty and fear were mentioned by many parents as some of the hardest emotional experiences. Stress and worry were also commonly expressed along with other negatively charged words. Examples of parental voice include the following: “Horrible. Stressful. Traumatic, Very Traumatic;” “Stressful, Hurtful and painful not to go home with your baby;” “Fear of the unknown. Length of stay and prognosis for long term.” Exhaustion was also reported by parents.

Some parents (28%) stated the hardest part of their experience was not going home with their baby or leaving their baby behind in the NICU. The separation was described as “heartbreaking” and “painful.” Especially difficult for several parents was “leaving at night” and “Being apart from my baby at night.” Some hospital policies contributed to feelings of separation that led to dissatisfaction.

“Not being “allowed” in the room at times. Not being able to care for my baby at times due to NICU “rules”. Having the baby be taken immediately at birth and not being able to see her four hours—seemed very unnecessary and was very upsetting.”

Some parents felt the NICU environment contributed to a sense of separation.

“Not being comfortable to visit, feeing like there no appropriate place to be peaceful with our baby.”

A difficult component of NICU admission is parents’ limited ability to provide the comfort and care normally given to their infants. Parents yearned to introduce the new baby to its siblings, to feed, clothe and hold the baby. Being unable to parent contributed to suboptimal parental experiences.

“The hardest parts have been not being able to comfort my baby the way I wanted to throughout this experience…not being able to hold him nearly 2 whole weeks after birth. That was awful.”

and

“Feeling helpless and having to leave my baby in the NICU without my wife and I”

and

“The hardest part by far was the inability to hold my child. I felt as if precious bonding time was being lost.”

Both mothers and fathers struggled with not being able to parent.

The sights of the NICU were distressing to many parents who described their NICU experiences as primarily visual. Parents had difficulty “watching our baby go through this” or “watching him endure things such as IVs and the chest tube.” They noted bruises, needle marks and IVs, and verbalized seeing “my swollen baby,” “my baby on ECMO,” and my “baby inhibited on CPAP.” Some parents reported dreading the sights in the NICU such as the monitors, tubes, and wires. One parent stated “Watching him endure things such as IVs an the chest tube” was the hardest part of the NICU experience and another parent reported “Terrible. Caused me to have panic attacks. Dreaded sights and sounds.” These sights and others, such as seeing their “baby in pain” were frequently reported as the hardest part of the NICU experience. The surgical experiences, both preoperative and postoperative, were also “distressing to see.” Furthermore, the sense of hearing also plays a crucial role; in fact, characteristic NICU noises such as monitor beeps have been reported to cause distress.

Seeing other children in the NICU was also reported as one of the hardest things for parents. They commented on “seeing other babies who were sick” and the close proximity of their infant to other babies in the NICU. Hearing the noises from other infants’ monitors was also described.

Parents struggled with balancing an ill child with other responsibilities. Long commutes to the NICU, parking and money were some of the items parents had to balance. Some felt unable to provide adequate support to their partner as shown in this quote: “Balancing home, NICU, work, supporting my wife.” Many families had children at home and struggled with splitting their time and responsibilities. One parent mentioned several challenges, all fraught with guilt: “Extremely difficult, helpless, sad, guilty to leave my baby, yet guilty being away from my older kids at home.” Several families simply stated they had difficulty balancing among home life, relationship with their spouse, finance, and work.

The NICU experience included positive parental experiences. When responding to the question “What has helped you cope with having a child in the NICU?” parents expressed many factors that positively influenced them. Support systems such as family, friends, and the clinical staff were frequently cited. Watching their infant heal and progress contributed to their coping. Parents also used self-help strategies to cope with their circumstances.

Parents voiced several positive feelings when they reflected on their NICU journey. They understood the necessity of a NICU admission, and some stated they were thankful, grateful and fortunate. One parent expressed happiness stating “We are SO thankful and happy that our babies made it this far. So, in some ways we are happy to be in a weird and stressful situation.”

The opportunity to see their child progress and heal contributed to coping and positivity. One parent stated their “sick child was getting better” while another reported that it was “incredible to watch recovery.” Several parents were grateful their child was given a “chance to survive”.

Parents relied on many different supportive relationships. Support from family and the nursing staff were most heavily mentioned (33% and 31% respectively). Spouses expressed appreciation for their partners. Parents voiced appreciation for supportive friends. Seventeen percent of respondents accessed their faith in God and prayer to help them cope.

Parents repeatedly expressed high regard for the clinical team members. Nurses, physicians, and other professionals were considered integral to the provision of quality care. Clinicians were described as “amazing”, “qualified”, “experienced”, “friendly”, and “knowledgeable.” Families felt a sense of relief their baby was in good hands and were “confident in the team.” One parent stated two quality attributes:

“1.) Knowing the nursing staff was exceptional, professional, compassionate, loving, and can take such good care of my baby 2.) Knowing that I was in the best hospital possible to provide exceptional care for my baby.”

Families benefitted from team members who provided comfort to them as parents and to their infant and expressed good care helped them to cope.

Parents provided data that reflect the value of specific clinician behaviors, such as “Consistent presence of nurses over [multiple] days” and “Reassuring nurses and doctors”.

Parents accessed several tools available to support their adaptation. While one parent preferred “taking one moment at a time” others preferred “preparing in advance at pre-diagnosis” and researching the condition. Parents found talking to other mothers, attending hospital support groups, and writing about their feelings useful. Some held a belief their baby would heal. Just being with and holding the baby were considered useful coping strategies.

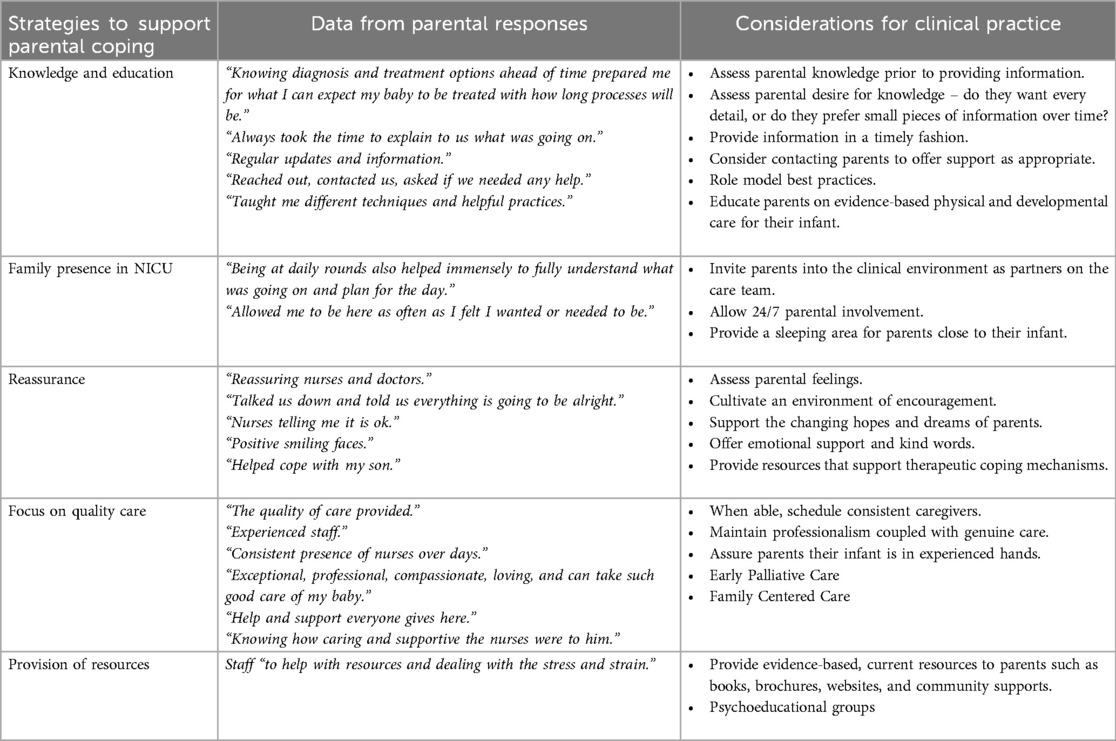

Consideration for clinical practice in order to support parental coping are reported in Table 3.

Table 3. Strategies to support parental coping and considerations for clinical practice based on anwsers to question “what has helped you cope with having a child in the NICU?”.

The main finding of our research is the identification of effective clinical coping strategies drawn from the experiences of parents with children undergoing hospitalization in the NICU due to Congenital Heart Disease (CHD). We have detailed these strategies for supporting parental coping in Table 3, along with qualitative data that underscores their effectiveness and considerations for clinical application. This achievement was made possible by conducting a thorough Krippendorff content analysis.

Theme 1 “Mixed emotions” refers to the different and opposing emotions that parents of CHD children face, consistent with other studies in this population (12–16). Our cohort of patients showed that their psychological asset is characterized by stress, fear, and anxiety. Alongside this vortex of negativity come the positive elements such as hope, acceptance, the joy of seeing their child fighting, getting better and making progress. Indeed, sometimes they expressed sadness and desperateness, other times they felt hopefulness and happiness: their emotions are not linear, they experience ups and down. This rollercoaster of emotions emphasizes how all parents of infants with CHD are at high risk for psychological distress (20, 26). We believe that in caring for these children and thus consequently for their parents, we cannot forget the psychological profile of these parents (27). We emphasize as the main clinical strategy associated to this first theme the continuous assessment of parental feelings and the support in the changing in hopes and dreams of parents. Indeed, health care professionals can have a significant impact on the care of these parents, embracing an individualized approach that supports the unique needs of families at different times (17, 28, 29), reassuring them and adapting care strategies according to either “Suboptimal Parental Experiences” (Theme 2) or to “Positive Parental Experiences” (Theme 3). These two themes identify the two alternating psychological states that are characteristic of the psychological set-up described so far. Thus, Theme 1 is composed of an alternation of Theme 2 and Theme 3, which we will analyze in more detail below.

Theme 2 “Suboptimal Parenting Experiences” is characterized by negative parental feelings. Parental stress appears in our cohort to be mainly due to separation from their child and the subsequent feeling of being unable to parent, which is consistent with prior work (11, 19). Indeed, in this regard, parents emphasized as coping mechanisms the ability to be with their child as much as possible and the need to feel involved in health care decisions. We hold that it is necessary and of utmost importance the opportunity for parents to be with their babies 24/7 by providing a space where they can rest and at the same time be next to their newborn. It is critically important to build a relationship of trust with the care team so that parents feel that they are part of the health care decisions about their child's health, regardless of the infant's medical fragility. Establishing a solid relationship of trust (9) will facilitate a conversation with the healthcare team in order to explore the family's goals, hopes and concerns, allowing them to regain a sense of control. Fundamental is the implementation of early PC. PC is not only effective in treating conditions defined as life-limiting (30–32) or serious illnesses, such as CHD, but it is essential where survival is still a likely outcome (21). PC helps parents regain their sense of parenthood by bonding, holding, touching, feeding and taking care of their child (19, 33, 34). PC has also been shown to decrease anxiety in parents of newborns with CHD and it was also found that PC interventions helped parents with other children suggesting possible help in balancing all their responsibilities (20). Indeed, an additional category we identified in Theme 2 is the one that concerns loss of balance leading to a feeling of guilt, not only about the sick child, but also the siblings, the partner, the difficulty of managing these relationships, finances, and work. In correlation with this, what parents reported as most helpful was the presence of the partner, family members and friends (Theme 3 category support system); thus, our data shows that a family centered care approach is necessary (26, 33, 34).

The last category belonging to Theme 2 is sensory encounters, including the sight of their own child going through a serious and painful journey, the presence of other children suffering and the environment (sounds, monitrs etc) of the NICU. Negative sensory encounters can lead to trauma and post-traumatic stress syndrome (8, 35, 36). For this category, no coping skills were evidenced by the parents, and we consequently could not identify clinical strategies as the suffering described is part of the pathway of the conditions under consideration. Since most diagnoses of CHD are done prenatally, it maybe helpful explaining to the parents what their baby will look like during the NICU admission and at the time of surgery. Pictures can be shown along with explanation of the meaning of wires, tubes, and lines that will be placed on the baby's body. Moreover, a prenatal tour of the NICU may help visualize the reality of the care and the hardware needed to help the baby during the admission.

Theme 3 “Positive parental experiences” is characterized by positive parental feelings arising from three main categories. In the psychosocial category, we identified the positive emotional parental feelings resulting from the acceptance and understanding of the need for hospitalization, their child's progress, and gratitude to the support system. In the support systems we identified the partner, family, faith, and healthcare team. As stated above family and partner are the most cited as coping mechanisms in our sample. The medical care team deserves further consideration as the quality of care reported by the parents interviewed enables the creation and maintenance of a trusting relationship, which is fundamental as reported at the beginning of the discussion. In addition, the key role of the team that was able to support the parents in this journey and help them face the hospitalization and care of their child, as reported in the literature (28, 37), emerged as one of the best coping support mechanisms. Other coping strategies identified in the analysis include self directed (Category g.i – Theme 3), such as journaling to express feelings, as well as participation in support and psychoeducational groups – these strategies have been demonstrated to enhance the quality of life of parents with CHD newborns (27).

Strengths of this study include the extensive sample size analyzed, particularly noteworthy for a qualitative analysis. The Krippendorff content analysis and the method used allows reproducibility of the results. Another strength is that all authors from the interdisciplinary team were involved in the analyses and had unanimous agreement in the categories and coding which limits the risk of bias.

There are some limitations. The study was conducted at a single tertiary care center therefore may not represent patient population of other centers. Similar limitation applies to the demographic distribution. Lastly, the exclusion of non-English speakers and an attrition rate of 17% in responses may result in missing a high-risk subgroups.

Understanding the parents’ experience and the personal, economic, familial, professional, and social (multidimensional) challenges of having a child admitted to the NICU is crucial for identifying coping strategies.

Further studies are needed to develop interventions to alleviate parents’ stress and anxiety and to prove their benefit.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by IRB Columbia University Medical Center. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

FC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data and Statistics on Congenital Heart Defects | CDC (2023). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/heartdefects/data.html (cited March 5, 2024).

2. Golfenshtein N, Hanlon AL, Lozano AJ, Srulovici E, Lisanti AJ, Cui N, et al. Parental post-traumatic stress and healthcare use in infants with Complex cardiac defects. J Pediatr. (2021) 238:241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.06.073

3. Wei H, Roscigno CI, Hanson CC, Swanson KM. Families of children with congenital heart disease: a literature review. Heart Lung. (2015) 44(6):494–511. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.08.005

4. Parfitt Y, Ayers S. Transition to parenthood and mental health in first-time parents. Infant Ment Health J. (2014) 35(3):263–73. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21443

5. Cleveland LM. Parenting in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2008) 37(6):666–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.x

6. Rihan SH, Mohamadeen LM, Zayadneh SA, Hilal FM, Rashid HA, Azzam NM, et al. Parents’ experience of having an infant in the neonatal intensive care unit: a qualitative study. Cureus. (2021) 13(7). doi: 10.7759/cureus.16747

7. Al Maghaireh DF, Abdullah KL, Chan CM, Piaw CY, Al Kawafha MM. Systematic review of qualitative studies exploring parental experiences in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs. (2016) 25(19–20):2745–56. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13259

8. Janvier A, Lantos J, Aschner J, Barrington K, Batton B, Batton D, et al. Stronger and more vulnerable: a balanced view of the impacts of the NICU experience on parents. Pediatrics. (2016) 138(3):e20160655. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0655

9. Hubbard DK, Davis P, Willis T, Raza F, Carter BS, Lantos JD. Trauma-informed care and ethics consultation in the NICU. Semin Perinatol. (2022) 46(3):151527. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151527

10. Doherty N, McCusker CG, Molloy B, Mulholland C, Rooney N, Craig B, et al. Predictors of psychological functioning in mothers and fathers of infants born with severe congenital heart disease. J Reprod Infant Psychol. (2009) 27(4):390–400. doi: 10.1080/02646830903190920

11. Sood E, Karpyn A, Demianczyk AC, Ryan J, Delaplane EA, Neely T, et al. Mothers and fathers experience stress of congenital heart disease differently: recommendations for pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2018) 19(7):626. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001528

12. Woolf-King SE, Arnold E, Weiss S, Teitel D. “There’s no acknowledgement of what this does to people”: a qualitative exploration of mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects. J Clin Nurs. (2018) 27(13–14):2785–94. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14275

13. Landolt MA, Buechel EV, Latal B. Predictors of parental quality of life after child open heart surgery: a 6-month prospective study. J Pediatr. (2011) 158(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.06.03

14. Woolf-King SE, Anger A, Arnold EA, Weiss SJ, Teitel D. Mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. (2017) 6(2):e004862. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004862

15. Lawoko S, Soares JJF. Psychosocial morbidity among parents of children with congenital heart disease: a prospective longitudinal study. Heart Lung. (2006) 35(5):301–14. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.01.004

16. Franck LS, Mcquillan A, Wray J, Grocott MPW, Goldman A. Parent stress levels during children’s hospital recovery after congenital heart surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. (2010) 31(7):961–8. doi: 10.1007/s00246-010-9726-5

17. Gabriel MG, Wakefield CE, Vetsch J, Karpelowsky JS, Darlington ASE, Grant DM, et al. The psychosocial experiences and needs of children undergoing surgery and their parents: a systematic review. J Pediatr Health Care. (2018) 32(2):133–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.08.003

18. Ramchandani PG, Stein A, O’Connor TG, Heron J, Murray L, Evans J. Depression in men in the postnatal period and later child psychopathology: a population cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2008) 47(4):390–8. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816429c2

19. Lisanti AJ, Vittner D, Medoff-Cooper B, Fogel J, Wernovsky G, Butler S. Individualized family centered developmental care: an essential model to address the unique needs of infants with congenital heart disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. (2019) 34(1):85–93. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000546

20. Callahan K, Steinwurtzel R, Brumarie L, Schechter S, Parravicini E. Early palliative care reduces stress in parents of neonates with congenital heart disease: validation of the “baby, attachment, comfort interventions”. J Perinatol. (2019) 39(12):1640–7. doi: 10.1038/s41372-019-0490-y

21. Bertaud S, Llovd DFA, Laddie J, Razavi R. The importance of early involvement of paediatric palliative care for patients with severe congenital heart disease. Arch Dis Child. (2016) 101(10):984–7. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309789

22. Mazwi ML, Henner N, Kirsch R. The role of palliative care in critical congenital heart disease. Semin Perinatol. (2017) 41(2):128–32. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2016.11.006

23. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19(6):349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

24. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. (2019). Available online at: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/content-analysis-4e (cited March 8, 2024).

25. Erlingsson C, Brysiewicz P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr J Emerg Med. (2017) 7(3):93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

26. Diffin J, Spence K, Naranian T, Badawi N, Johnston L. Stress and distress in parents of neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for cardiac surgery. Early Hum Dev. (2016) 103:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.08.002

27. Rodrigues MG, Rodrigues JD, Moreira JA, Clemente F, Dias CC, Azevedo LF, et al. A randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of psychoeducation on the quality of life of parents with children with congenital heart defects—quantitative component. Child Care Health Dev. (2024) 50(1):e13199. doi: 10.1111/cch.13199

28. McMahon E, Chang YS. From surviving to thriving - parental experiences of hospitalised infants with congenital heart disease undergoing cardiac surgery: a qualitative synthesis. J Pediatr Nurs. (2020) 51:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2019.12.010

29. Gómez-Cantarino S, García-Valdivieso I, Moncunill-Martínez E, Yáñez-Araque B, Ugarte Gurrutxaga MI. Developing a family-centered care model in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU): a new vision to manage healthcare. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17(19):7197. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197197

30. McCarthy FT, Kenis A, Parravicini E. Perinatal palliative care: focus on comfort. Front Pediatr. (2023) 11. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1258285

31. Parravicini E. Neonatal palliative care. Curr Opin Pediatr. (2017) 29(2):135–40. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000464

32. Carter BS. Pediatric palliative care in infants and neonates. Children (Basel). (2018) 5(2):21. doi: 10.3390/children5020021

33. Kang TI, Munson D, Hwang J, Feudtner C. Integration of palliative care into the care of children with serious illness. Pediatr Rev. (2014) 35(8):318–26. doi: 10.1542/pir.35-8-318

34. Carter BS, Parravicini E, Benini F, Lago P. Editorial: perinatal palliative care comes of age. Front Pediatr. (2021) 9:709383. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.709383

35. Wei H, Roscigno CI, Swanson KM, Black BP, Hudson-Barr D, Hanson CC. Parents’ experiences of having a child undergoing congenital heart surgery: an emotional rollercoaster from shocking to blessing. Heart Lung. (2016) 45(2):154–60. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.12.007

36. Kim WJ, Lee E, Kim KR, Namkoong K, Park ES, Rha DW. Progress of PTSD symptoms following birth: a prospective study in mothers of high-risk infants. J Perinatol. (2015) 35(8):575–9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.9

Keywords: neonatal intensive & critical care, content analaysis, congenital heart defect (CHD), parents’ experience, coping strategies

Citation: Catapano F, Steinwurtzel R, Parravicini E and Wool C (2024) A qualitative analysis of parents’ experiences while their neonates with congenital heart disease require intensive care. Front. Pediatr. 12:1425320. doi: 10.3389/fped.2024.1425320

Received: 29 April 2024; Accepted: 19 August 2024;

Published: 5 September 2024.

Edited by:

Karel Allegaert, KU Leuven, BelgiumReviewed by:

Jana Pressler, University of Nebraska Medical Center, United StatesCopyright: © 2024 Catapano, Steinwurtzel, Parravicini and Wool. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francesca Catapano, ZnJhbmNlc2NhLmNhdGFwYW5vM0B1bmliby5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.