- 1Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2Child Health Evaluative Sciences, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Child Life Program, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

Introduction: Childhood critical illness impacts the entire family of the critically ill patient. Disruptions to usual family rhythms and routines, established relationships, physical relocations or shifts in caregivers, and the uncertainty about the patient's well-being can have significant impacts on siblings and other connected children in the family. Promoting and facilitating family interactions and engaging younger family members in the hospital experience have been shown to reduce patient and family anxiety, enhance family adaptation, and improve child and family outcomes. The critical care team can implement evidence-informed approaches to address and mitigate challenges for families and provide developmentally aligned support to impacted siblings.

Aim: This conceptual paper describes the potential impacts of a critical illness hospitalization on siblings, approaches to supporting siblings, and practical interventions drawn from a synthesis of the current literature and the author's practice experience caring for critically ill children and their families.

Data sources: A traditional review and narrative analysis moderated by the authors and supported by lived experience.

Conclusions: There is a range of impacts of a critical illness hospitalization on siblings and young family members of the patient. Providing consistent, transparent, and supportive child, sibling, and whole family-centered care can improve the experience and outcomes for the child and family.

Introduction

Childhood critical illness affects the entire family unit. This disruption has significant impacts on siblings and other children in the family due to changes in family rhythms and routines, physical relocation, changes in caregivers, and uncertainty of the patient's well-being (1–3). The term “sibling” acknowledges all the children and youth who are part of the patient's relationship systems regardless of their biological or relational connections. All children and youth members of the patient's family or immediate community may benefit from these recommendations (2).

Approaches and interventions to support family members during the critical care experience have evolved to include family presence, emotional care for family members, shared decision-making, and participatory care planning. Parents can contribute to their child's care through multiple avenues including participation in medical rounding and providing direct care to the child (1). Less attention has been paid to integrating siblings of the ill child. The PICU environment and processes are designed for adults. Young family members' needs may not be easily identified and thus siblings may be poorly integrated into the plan of care (4).

Developing systems and approaches to care that promote and nurture family interactions and engage younger family members can have a positive impact on the patient and family (5–7). Sibling-inclusive practices can reduce anxiety for the sibling and parents, enhance family adaptation, and shorten recovery time (8). When the integrity of the whole family is preserved, patients and their families are more satisfied with their care, achieve growth, and may develop skills applicable to future family challenges. In this conceptual paper, we discuss the potential impacts of childhood critical illness hospitalization on siblings. We describe approaches and practical interventions, drawn from the literature and practice experience, that facilitate care for critically ill children, siblings and families.

Impacts of critical hospitalization of a child on siblings

Well siblings of critically ill patients are exposed to many stresses. These stresses may be similar to those experienced by parents and adult family members. For example, they worry about the ill child and experience fear of the unknown. Children also experience challenges unique to being a sibling, for example, disruption to their daily activities and anxiety related to separation from family members and caregivers (1). Siblings can be displaced from familiar environments, their home, school, or community as their families rearrange childcare and home responsibilities. It is common for siblings to feel confusion, jealousy, resentment, and guilt or to blame themselves for the distress they witness (8, 9, 10). Siblings may also experience isolation and feel forgotten by the family, have limited access to their usual coping mechanisms, and may not have the ability to ground their interpretation of events (1, 3). Siblings may create fictional causes or reasons for the illness and project unrealistic or inaccurate understandings about the patient's situation and the resulting disruption to the family (1).

The adults who support siblings can also face pragmatic, emotional, and interpersonal challenges. Parents and family caregivers may experience conflict related to their role and obligations to the patient (11, 12). Families report struggling with separation during hospitalization and experience tension between the needs of the patient and those of other children in the family (13).

Environmental and situational stressors are numerous as well. Parents must adapt to the intensive care environment, deal with overwhelming informational needs, and are required to function in a novel and unanticipated context (14). Parents require energy, support, and resources to navigate the unpredictable and dynamic elements of their child's critical illness (2).

Parents may also feel uncertain about how to best support the well child. How to be a parent in a critical illness situation may not be intuitively understood, and the skills required to do so effectively may be unfamiliar or lacking. Families report a desire to protect their well children at home while also feeling the need to inform and engage them (15). Thus, parents may need guidance and support to address the needs of the well children in the family.

Family perspectives during critical illness are shaped by the context of the child's hospitalization. The individual sociocultural character of the family, along with their goals, expectations, and preferred roles, shapes the needs of the family and its members including siblings (16). By acknowledging these tensions, anticipating needs, and providing validation, the critical care interprofessional team can assist each family to successfully navigate these challenges and ensure all members including siblings are supported.

Principles guiding sibling support

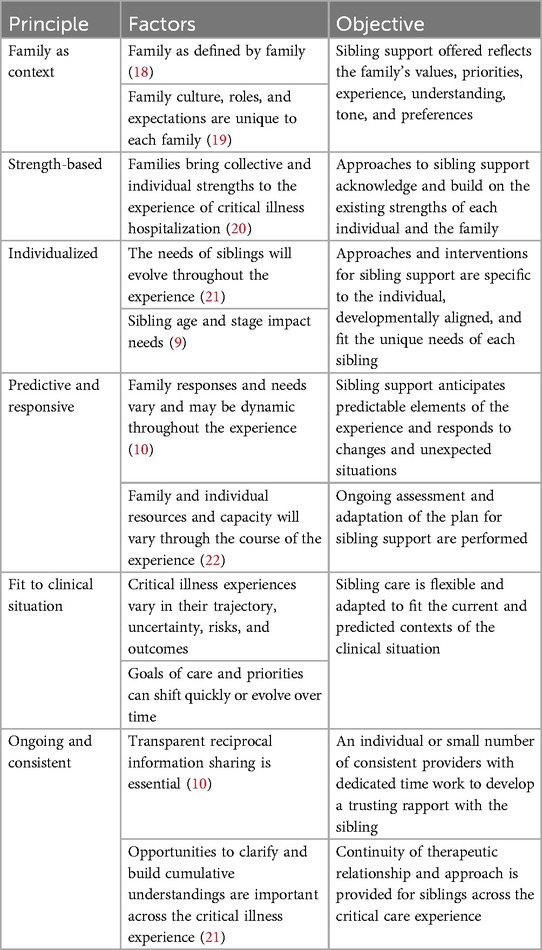

The guiding principles of family-centered care (FCC)—respect and dignity, information sharing, participation, and collaboration—inform approaches to ensuring sibling well-being (17). Interventions addressing sibling needs are therefore strength-based, aligned with principles of FCC, and are intentionally fit to the child and family context while remaining sensitive to the clinical situation. These foundational principles were drawn from an informal traditional search of the current evidence supported by a medical librarian. Selected publications were reviewed by all authors, and principles were developed through consensus.

Sibling support and the initiation of a sibling care plan aligned with these principles can be provided by any knowledgeable members of the healthcare team including social workers, child life specialists, nurses, physicians, developmental specialists, and family experience navigators. Table 1 illustrates the six principles guiding sibling care and the associated objectives for critical care providers.

Goals for sibling support

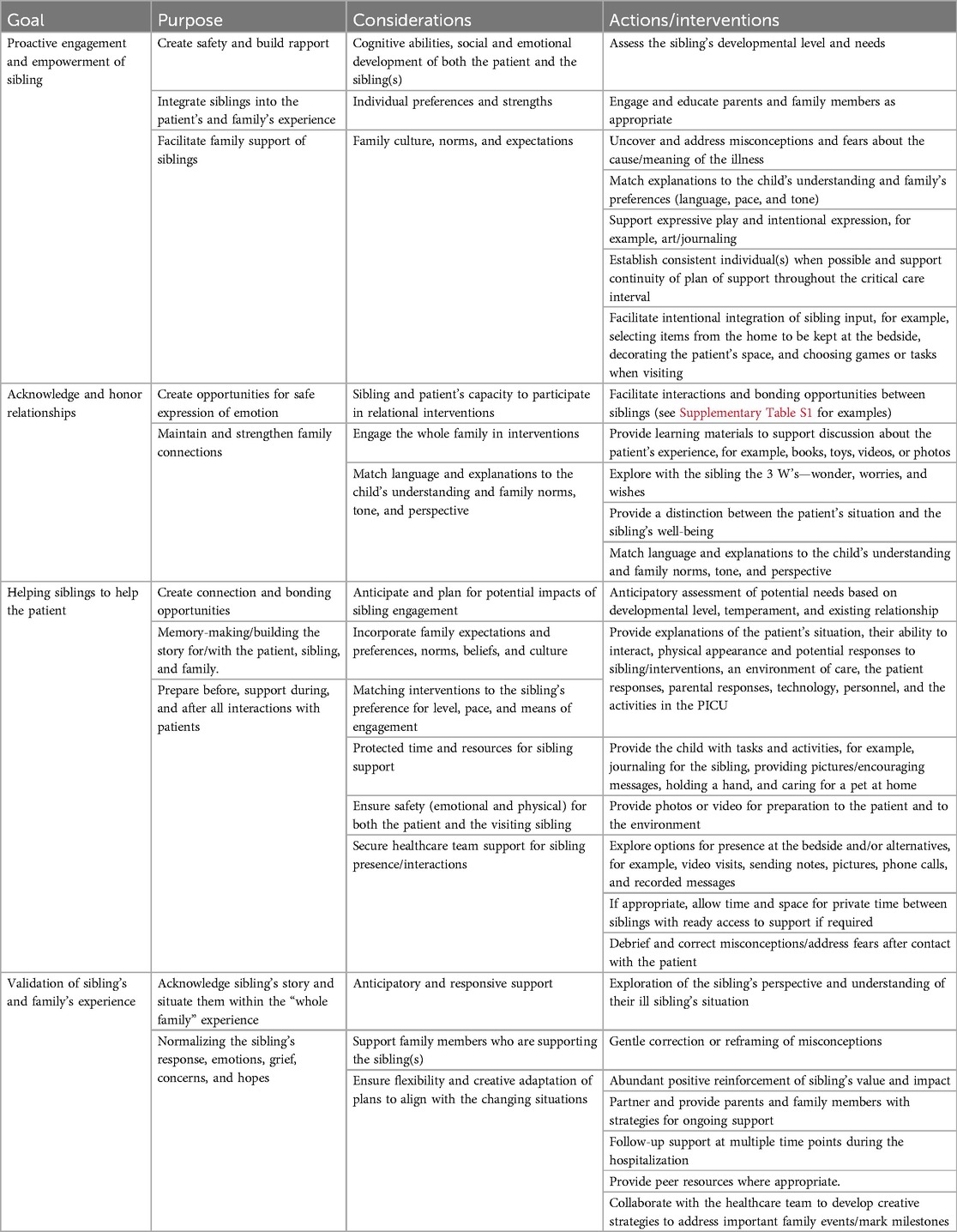

There are several interrelated goals for addressing sibling needs during a child's critical hospitalization. Achieving these goals will mutually benefit the sibling, the family, and the patient. Sibling support aims to (1) facilitate sibling engagement through active exploration and validation of needs, (2) acknowledge and honor relationships, (3) help the sibling to help the patient, and (4) normalize the sibling's responses and the critical care experience. Table 2 illustrates these goals, associated considerations, and examples of potential interventions for each.

Proactive engagement and empowerment of sibling

Every family with a child in critical care should be assessed for child and youth family member needs. Parents might not be aware of their well child's experiences, or know of resources and expertise to support siblings, nor what benefits can be realized. However, parents can provide information about the family’s values and priorities and how to best support the sibling.

To engage siblings, opportunities for safe expression of emotions should be created. To facilitate emotional exploration with siblings, a safe environment is essential. Utilizing a private, child-friendly space is preferred when first meeting and assessing the sibling (23). Accessing parent and other family members’ perspectives on the child's temperament and coping strategies before meeting with the sibling establishes a foundation from which to begin building rapport. If parents and other family participate in conversations with the sibling, attention should be paid to preparing each participant for their role in that conversation. Preparation for these interactions can empower families to fulfill their role in supporting the patient and sibling(s) and will nurture existing family relationships. The extent to which an individual sibling is engaged in the patient's situation depends on the individual sibling's strengths, wishes, and the context of the illness.

Acknowledge and honor relationships

Family connections can be under strain in times of critical illness experience. Acknowledging the connections between siblings helps integrate the well child into the family's story facilitating existing bonds (1). Connecting interventions intended to honor the relationship siblings share are matched to the sibling's and patient's emotional and cognitive capacity (24). Interventions acknowledging the sibling relationship can include the sibling's participation in family/ health care team discussions, being present with the patient, or designing alternative presence pathways. Supplementary Table S1 provides examples of interventions that assist with connection and acknowledging and maintaining sibling relationships.

Helping siblings to help the patient

Assisting the sibling in engaging in the experience of the patient facilitates normalization and strengthens relationships (22). Interventions include soliciting the sibling’s input about the patient's likes and dislikes, active information sharing, spending time with the patient, designing and participating in special events or activities, and helping the patient directly with care and daily activities.

When collaborating with the sibling to help the patient, anticipatory assessment of the sibling's developmental level, temperament, and the existing relationship is essential. Interventions co-designed with the family and the sibling are preferred and these should be matched to the level of participation desired by the sibling. Examples of interventions include journaling for the sibling, providing pictures, sharing messages, selecting music to be played to the patient, or holding the patient's hand.

Options for the sibling to be at the bedside (and/or alternatives) should be explored. If visiting the patient is not possible, remote connections can be made through video visits, sending notes, pictures, phone calls, and recorded messages (25). If the sibling visits in person, thorough preparation for the sibling, family, and the critical care team is recommended. The sights, smells, and sounds of critical care and the plethora of professional care providers that the patient and their family interact with can be overwhelming. Support offered to siblings must prepare them for exposure to the critical care environment. Explanations of the setting, language, people, and equipment that the sibling may encounter are necessary. Siblings should also be prepared for the changed appearance, responses, and behavior of the patient. Viewing photos and videos of the patient and the care space prior to visiting can be helpful.

When facilitating interactions between the sibling and the patient consider exploration of the sibling's “wonders, worries, and wishes” (3 W's). Exploring the three W's prepares the child for their brother's or sister's changed appearance, behaviors, and ability to interact and can minimize any misinterpretation and fears (26). During bedside visits, it is advised that the sibling is provided with a purpose, task, or role to fulfill during the visit. Opportunities to connect siblings with the patient can be time-sensitive depending on the severity of the patient's illness. When possible, identifying and protecting time at the bedside for meaningful interactions between siblings should be considered. If appropriate, allow for a private time between the siblings with ready access to support if required. Create a plan for ending the visit should the situation change. It is essential to also debrief the visit to explore and correct any misconceptions or fears that arise after visiting (9, 27, 28). Helping siblings to help the patient requires the entire healthcare team's support. Frequent communication within the team and flexible, transparent planning are necessary to ensure a positive experience.

Normalize the sibling's responses and the critical care experience for the family

Providing space and safety for the sibling to explore their feelings and open acknowledgment of these feelings as significant and valid provides a sense of normalcy in situations that feel overwhelming. Assisting siblings to understand why they are feeling the way they do helps reduce feelings of isolation and uncertainty. Actively normalizing the experience for siblings is ongoing as change is expected based on the patient's trajectory of illness recovery and the sibling's evolving understanding and engagement.

Educating and providing tools to adult family members to assist them in normalizing the sibling's emotions and concerns will assist in the anticipation of sibling needs and support timely responses as these needs arise. When both the critical care team and the family recognize, normalize, and validate the sibling's feelings the sibling can be an active participant and be present in the family's journey.

Facilitating non-medical activities of importance for the family can contribute to normalizing the experience. These activities can include observances, traditional celebrations, and family milestones. In times of critical childhood illness, the child and family's medical journey is often prioritized. By integrating non medical activities and events significant family occasions are not displaced (6). These events can occur alongside the medical plan of care and send a message of respect for family norms, cultural values, and wishes. Engaging sibling's input in decision-making and planning of family activities further consolidates their key role with their brother or sister. These connections will provide a meaningful opportunity for memory-making for the entire family (1).

Operationalizing sibling support

Engaging with siblings is a continuous and ongoing process. Support for siblings requires the critical care team to recognize the importance of sibling well-being for the patient the sibling and the family. This can be hard to accomplish in the day-to-day activities of critical care. Activity is fast-paced and reactive to dynamic changes in clinical needs, resources, and organizational demands. Often the focus for critical care providers is the patient before them. Parents and adult families enjoy an established role with the team through their caregiving capacity, knowledge about their child, and as decision-makers for their child’s well-being. Siblings do not hold the same position within the day-to-day activities of critical care. They are often out of sight, and critical care providers must proactively reach out to understand how siblings might fit into the experience for the patient and family (2).

Unique factors such as family presence policy restricting children from the bedside and a physical environment that is not designed to accommodate children need to be identified and mitigated to engage siblings fully. If critical care team education is lacking the required knowledge and skills for sibling care will be limited, and the team's ability to recognize need and deliver appropriate interventions will be insufficient.

Uncertainty in terms of best practices and accountability for sibling care can also inhibit a team's ability to achieve the best sibling care (29). Some critical care units may have designated responsibility for sibling care to allied health roles such as social work or child life specialists (30). Sibling care interventions can be delivered by any knowledgeable critical care provider; however, success is best achieved when an overall culture of sibling inclusion is shared by the team and the processes of sibling care are grounded by organization policy.

Breaking sibling care into four pragmatic phases can assist the critical care team in operationalizing sibling support. These phases are (1) explore, (2) plan, (3) activate, and (4) follow through. The sibling support cycle is continuous. The phases of the cycle ground the continued assessment of the clinical context and individualized patient, sibling, and family needs throughout the critical care experience.

In the explore phase, determining if and to what extent the sibling would like to be connected to the patient is important. Options can be presented, and interventions adapted to fit the sibling's preference, capacity, and strengths.

In the plan phase, individualized and context-specific interventions are determined collaboratively with siblings and families. Selected interventions are then fit to the preferences, strengths, clinical context, and expectations of the child, sibling, and family.

The activate phase reflects the time when the sibling support plan is initiated and refined. Each sibling support intervention should be thoughtfully prepared, intentionally flexible in application, and include a purposeful evaluation of its effectiveness.

During the follow-through phase, the focus is on adapting and aligning interventions with the evolving goals for sibling support and modifying interventions in response to changes in the patient or the clinical situation. Attention to transparent communication and thoughtful determination of the next steps are the focus. There is also the opportunity to anticipate and plan for times when sibling needs can be predicted, for example, preparing for the transition to another area of care, changes in the patient's clinical situation (anticipated or unexpected), or changes in the family's situation. Essential in all phases of the cycle is the integration of child, sibling, and family perspectives and ensuring supportive relationships with the health care team.

Conclusion

The critical childhood hospitalization of a brother, sister, or close child family member can disrupt family routines, and relationships and significantly impact the well child. Sibling well-being is essential to patient, sibling, and family adaptation. Providing adequate support for siblings has the potential to reduce family stress, elevate sibling and family well-being, and facilitate whole family adaptation to the patient's health situation (15).

Sibling support interventions need to fit the child, the family, and the illness factors. The impacts of individual interventions and the longer-term outcome for siblings of a critically ill child are not yet fully understood. Increasing critical care provider awareness of the sibling experience, exposing whole family outcomes, and evaluating interventions provided are important next steps in informing our collective understanding of, and ability to address these important needs. Developing mechanisms and skills to deliver consistent, strength-based sibling and family care is essential to facilitate whole family adaptation and support the best outcomes for patients and families.

Author contributions

KD-P: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KO’L: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Amy Zubick, Parent Liaison, Heart Center and Cardiac Critical Care Unit, Hospital for Sick Children, for sharing her insights during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2024.1337491/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Abela KM, Casarez RL, Kaplow J, LoBiondo-Wood G. Siblings’ experience during pediatric intensive care hospitalization. J Pediatr Nurs. (2022) 64:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2022.02.008

2. Biswas M. Impact of critical illness on healthy siblings. Pediatr Nurs. (2022) 48(3):129–35. http://www.ajj.com/services/publication-services

3. Gill MA. Making space for siblings in family-centered care. Pediatr Nurs. (2020) 46(1):48–51. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/making-space-siblings-family-centered-care/docview/2355333589/se-2

4. Wincek JM. Promoting family-centered visitation makes a difference. AACN Clin Issues Crit Care Nurs. (1991) 2(2):293–8. doi: 10.4037/15597768-1991-2015

5. Hartling L, Milne A, Tjosvold L, Wrightson D, Gallivan J, Newton AS. A systematic review of interventions to support siblings of children with chronic illness or disability. J Paediatr Child Health. (2014) 50(10):E26–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01771

6. Rozdilsky JR. Enhancing sibling presence in pediatric ICU. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. (2005) 17(4):451–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2005.07.001

7. Manning J, Pinto N, Rennick J, Colville G, Curley M. Conceptualizing post intensive care syndrome in children—the PICS-p framework. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2018) 19(4):298–300. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001476

8. Keller BP, Abney M, Boles JC. Child life services for siblings of chronically ill children. J Child Life: Psycho Theory Prac. (2023) 4:2. doi: 10.55591/001c.84322

9. Blamires J, Foster M, Rasmussen S, Zgambo M, Mörelius E. The experiences and perceptions of healthy siblings of children with a long-term condition: umbrella review. J Pediatr Nurs. (2024) 77:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2024.03.022

10. Bichard E, Butler AE. Visiting restrictions during COVID-19 pandemic—why are we still excluding siblings? Nurs Crit Care. (2023) 28(5):826–7. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12898

11. Abela KM, Wardell D, Rozmus C, LoBiondo-Wood G. Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: an updated systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs. (2020) 51:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2019.10.013

12. Rennick J. Reestablishing the parental role in a pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr Nurs. (1986) 1(1):40–4. PMID: 3634805.3634805

13. Colville G, Darkins J, Hesketh J, Bennett V, Alcock J, Noyes J. The impact on parents of a child’s admission to intensive care: integration of qualitative findings from a cross-sectional study. Intensive Critical Care Nurse. (2009) 25(2):72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2008.10.002

14. Macdonald ME, Liben S, Carnevale FA, Cohen SR. An office or a bedroom? Challenges for family-centered care in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Child Health Care. (2012) 16(3):237–49. doi: 10.1177/1367493511430678

15. Thompson RH, Bennett KL, Snow ACW. Research in child life. In: Thompson RH, editor. The Handbook of Child Life: A Guide for Pediatric Psychosocial Care. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd (2018). p. 55–103.

16. Carnevale FA. Striving to recapture our previous life: the experience of families with critically ill children. Dynamics Official J Can Association Crit Care Nurs. (1999) 1(1):16–22. PMID: 10347503.

17. Institute for Patient And Family-Centered Care. “About US” Institute For Patient And Family-Centered Care. (2024). Available online at: https://www.ipfcc.org/about/pfcc.html (Accessed June 8, 2024).

18. Wright LM, Leahey M. Calgary family intervention model: one way to think about change. J Marital Fam Ther. (1994) 20(4):381–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1994.tb00128

19. Foster M, Whitehead L, Maybee P. The parents, hospitalized child’s, and critical care providers perceptions and experiences of family-centered care within a pediatric critical care setting: a synthesis of quantitative research. J Fam Nurs. (2015) 22(1):6–73. doi: 10.1177/1074840715618193

20. Gottlieb LN. Strengths-Based Nursing Care: Health and Healing for Person and Family. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co (2013).

21. Tay J, Widger K, Stremler R. Self-reported experiences of siblings of children with life-threatening conditions: a scoping review. J Child Health Care. (2022) 26(4):517–30. doi: 10.1177/13674935211026113

22. Romito B, Jewell J, Jackson M, AAP Committee on Hospital Care; Association of Child Life Professionals. Child life services. Pediatrics. (2021) 147(1):e2020040261. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-040261

23. Beickert K, Mora K. Transforming the pediatric experience: the story of child life. Pediatr Ann. (2017) 46(9):e345–51. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20170810-01

24. Eaton C. Sibling Support Strategies. Toronto: Internal Report, Hospital for Sick Children (2003).

25. Bensink M, Shergold J, Lockwood L, Little M, Irving H, Russell T, et al. Videophone support for an eight-year-old boy undergoing paediatric bone marrow transplantation. J Telemed Telecare. (2006) 12(5):266–8. doi: 10.1258/135763306777889082

26. Sick Kids. Talking to Kids about Serious Illness. The 6 C’s and the 3 W’s. (2023) Retrieved from: www.sickkids.ca

27. Brauchle M, Deffner T, Nydahl P, ICU kids study group. Ten recommendations for child-friendly visiting policies in critical care. Intensive Care Med. (2023) 49(3):341–4. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06974-w

28. Watson RS, Choong K, Colville G, Crow S, Dervan LA, Hopkins RO, et al. Life after critical illness in children–toward an understanding of pediatric post-intensive care syndrome. J Pediatr. (2018) 198:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.084

29. Olivier-D’Avignon M, Dumont S, Valois P, Cohen SR. The needs of siblings of children with a life-threatening illness, part 1: conceptualization and development of a measure. Palliative and Supportive Care. (2017) 15(6):644–64. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516

Keywords: pediatric, child, critical illness, intensive care, child and family-centered care, siblings

Citation: Dryden-Palmer K, Shinewald A and O'Leary K (2024) Supporting siblings during the critical illness hospitalization of a child: learning from experience. Front. Pediatr. 12:1337491. doi: 10.3389/fped.2024.1337491

Received: 13 November 2023; Accepted: 30 July 2024;

Published: 26 August 2024.

Edited by:

Michael Spaeder, University of Virginia, United StatesReviewed by:

Jason Custer, University of Maryland, United StatesVanessa Madrigal, Children’s National Hospital, United States

Copyright: © 2024 Dryden-Palmer, Shinewald and O'Leary. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karen Dryden-Palmer, a2FyZW4uZHJ5ZGVuLXBhbG1lckBzaWNra2lkcy5jYQ==

Karen Dryden-Palmer

Karen Dryden-Palmer Alexis Shinewald

Alexis Shinewald Kimberly O'Leary

Kimberly O'Leary