- 1Department of Neonatology, Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, Pune, India

- 2Department of Neonatology, Cloudnine Hospital, Bengaluru, India

- 3Department of Neonatology, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, NSW, Australia

Background: Oral motor stimulation interventions improve oral feeding readiness and earlier full oral feeding in preterm neonates. However, using a structured method may improve the transition time to full oral feeds and feeding efficiency with respect to weight gain and exclusive breastfeeding when compared to an unstructured intervention.

Objective: To compare the effect of Premature Infant Oral Motor Intervention (PIOMI) and routine oromotor stimulation (OMS) on oral feeding readiness.

Methods: Randomised controlled trial conducted in a neonatal intensive care unit between June-December 2022. Preterm neonates, 29+0–33+6 weeks corrected gestational age, were studied. The intervention group received PIOMI and the control group received OMS. Primary outcome: time to oral feeding readiness by Premature Oral Feeding Readiness Assessment Scale (POFRAS) score ≥30. Secondary outcomes: time to full oral feeds, duration of hospitalisation, weight gain, and exclusive breastfeeding rates.

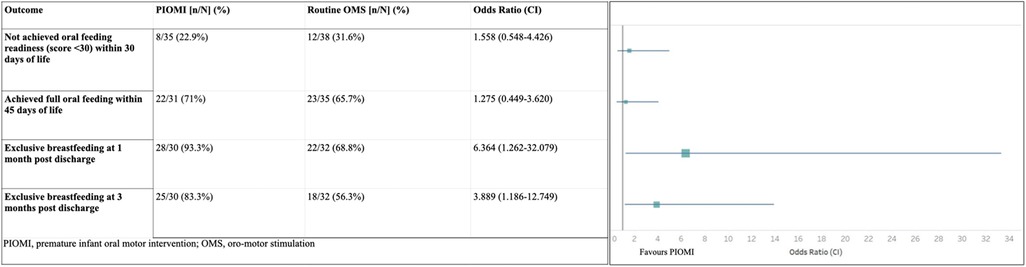

Results: A total of 84 neonates were included and were randomised 42 each in PIOMI and OMS groups. The mean chronological age and time to oral feeding readiness were lower by 4.6 and 2.7 days, respectively, for PIOMI. The transition time to full oral feeds was 2 days lower for PIOMI and the duration of hospitalisation was 8 days lower. The average weight gain was 4.9 g/kg/day more and the exclusive breastfeeding rates at 1 month and 3 months post-discharge were higher by 24.5% and 27%, respectively, for the PIOMI group. The subgroup analysis of study outcomes based on sex and weight for gestational age showed significant weight gain on oral feeds in neonates receiving PIOMI. Similarly, the subgroup analysis based on gestational age favoured the PIOMI group with significantly earlier transition time and weight gain on oral feeds for the neonates >28 weeks of gestational age. The odds of achieving oral feeding readiness by 30 days [OR 1.558 (0.548–4.426)], full oral feeds by 45 days [OR 1.275 (0.449–3.620)], and exclusive breastfeeding at 1 month [OR 6.364 (1.262–32.079)] and 3 months [3.889 (1.186–12.749)] after discharge were higher with PIOMI.

Conclusion: PIOMI is a more effective oromotor stimulation method for earlier and improved oral feeding in preterm neonates.

Clinical trial registration: https://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/pdf_generate.php?trialid=70054&EncHid=34792.72281&modid=1&compid=19','70054det', identifier, CTRI/2022/06/043048.

Introduction

Annually, approximately 15 million neonates are born prematurely (1) with a high risk for oral feeding difficulties due to uncoordinated suck swallow reflexes and poor oral muscle tone (2, 3). Therapies for early attainment of oral feeding are oromotor stimulation (OMS) techniques such as intraoral, perioral stroking and non-nutritive sucking (NNS), Beckman's Oral Motor Intervention (BOMI), and Premature Infant Oral Motor Intervention (PIOMI). PIOMI is a 5-minute 8-step therapy focusing on the lip, jaw, and tongue movements. It simulates the in-utero oral motor experience and has been reported to result in a faster transition to full oral feeds, improved suck strength, and increased breastfeeding rates (4). A study by Arora et al. suggested that PIOMI improves the oromotor skills documented as improved mean Neonatal Oromotor Assessment Scale (NOMAS) scores in preterm neonates (5). As a part of feeding rehabilitation, Ghomi et al. reported the earlier introduction of first oral feeds and shorter hospitalisation with PIOMI (6). A few studies have reported the beneficial effect of PIOMI on feeding efficiency and breastfeeding rates but a statistically significant inference could not be drawn from these (7–9). Hence, conflicting evidence exists for the said outcomes and there is a paucity of data for comparison between structured and unstructured methods of oral motor stimulation. This study was, therefore, designed to test the effectiveness of PIOMI over routine OMS on oral feeding readiness.

Methodology

A single-centre randomised controlled trial was conducted in a tertiary-level neonatal intensive care unit enrolling neonates between June to December 2022. All preterm neonates with birth gestation of <34 weeks and corrected gestational age (CGA) 29+0–33+6 weeks who were free of invasive ventilation and inotropic support were assessed for eligibility. Neonates with a neuromuscular disorder, chromosomal anomaly, or craniofacial malformation were excluded. Any neonate with maternal retroviral disease was excluded from the outcome analysis for exclusive breastfeeding. Written informed consent was taken from parents prior to enrolment. Maternal and neonatal baseline characteristics (mode of delivery, indication of delivery, gestational age, sex, birth weight, and resuscitation details) were recorded. Included neonates were randomised into two groups, namely, PIOMI and routine OMS in a 1:1 ratio by simple randomisation using a computer-generated random number table, and intervention was started after 29+0 weeks CGA.

The baseline Premature Oral Feeding Readiness Assessment Scale (POFRAS) assessment was done before the initiation of intervention by one of the two independent blinded scorers (Supplementary file). The blinding of the study participants and intervention providers could not be done, however, the intervention providers and POFRAS scorers were blinded to each other. Neonates who were randomised to the PIOMI group were administered intervention 15 min before the gavage feed once daily using all aseptic precautions and with gloved fingers if CGA was 29+0–30+6 weeks. This process was continued for 7 days until the next POFRAS assessment. After CGA 31 weeks, PIOMI was similarly performed twice daily. PIOMI was done by the principal investigator who underwent training under the founder of PIOMI prior to the commencement of the study. The other group received OMS from trained nursing staff.

For PIOMI, the neonate was positioned in the midline position with the neck slightly flexed and the chin tucked in. Following this, the neonate underwent one cycle each of cheek C-stretch, lip roll, lip curl/stretch, and gum massage for 30 s each. This was followed by stretching of lateral borders of the tongue/cheek for 15 s and mid-blade of the tongue/palate for 30 s. After this, elicitation of suck was performed for 15 s followed by non-nutritive sucking on the mother's breast (or gloved finger/pacifier if the mother was not available) for 2 min. The entire process lasted 5 min.

The second group received OMS as part of routine care. This was a 15-min, 3-step technique comprising of two finger circular movements in a U-shaped fashion from both ears, followed by O-shaped perioral stimulation and ending with pouting stimulation of the cheeks. This method was done 15 min prior to each gavage feed by a trained nurse.

In both groups, the intervention was suspended if there was sudden heart rate acceleration/deceleration, desaturation, apnoea, hiccupping, yawning, sneezing, frowning, looking away, squirming, frantic/disorganised activity, pushing away of arms and legs or if the neonate became sick in the intervening period and required invasive ventilator support/inotropes. The intervention was resumed after 24 h of resolution of the issue and continued for the subsequent 7 days.

Each POFRAS assessment was done after 7 days of intervention. If the score was <25 in either group, the respective intervention was repeated for another 7 days and POFRAS was reassessed. If the score was 25–29 in either group, the respective intervention was repeated for another 3 days and POFRAS was reassessed. Oral feeds were started after POFRAS ≥30. Upon tolerance, feeds were increased gradually to full oral feeds. Exclusive breastfeeding was assessed at 1 month and 3 months post-discharge in both groups. Exclusive breastfeeding was defined as feeding the infant only breastmilk from his or her mother until the time of assessment and no other solids or liquids except for drops or syrups containing vitamins, minerals, supplements, or medicines.

The primary outcome measure was time to oral feed readiness and secondary outcome measures were transition time to full oral feeds, duration of hospital stay, weight gain, and exclusive breastfeeding rate post-discharge.

The study conformed to the reporting checklist criteria for randomised trial based on the CONSORT guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Data was entered in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) and analysed using IBM SPSS statistical software version 25. Continuous variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (inter-quartile range), depending on the distribution of the data. Categorical variables were expressed using frequencies and percentages. For qualitative data variables, the Chi-square test was used and for quantitative data variables, two independent sample t and median tests were used. P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Kaplan–Meier probability analysis curves were used for the establishment of oral feeds. An odds ratio analysis was performed for outcomes related to oral feeding and exclusive breastfeeding. Intention to treat and per protocol analysis was done for exclusive breastfeeding rates. For the outcomes related to the progression of feeds and weight, a subgroup analysis was conducted for sex, gestational age, and weight for gestational age. The inter-observer variability was calculated to be 0.933 (Cronbach's alpha) between the two independent blinded scorers on 20 subjects prior to the commencement of the study. The sample size calculated for statistical significance as per the feeding outcome of a previous study (5) was 42 with 21 in each group.

Results

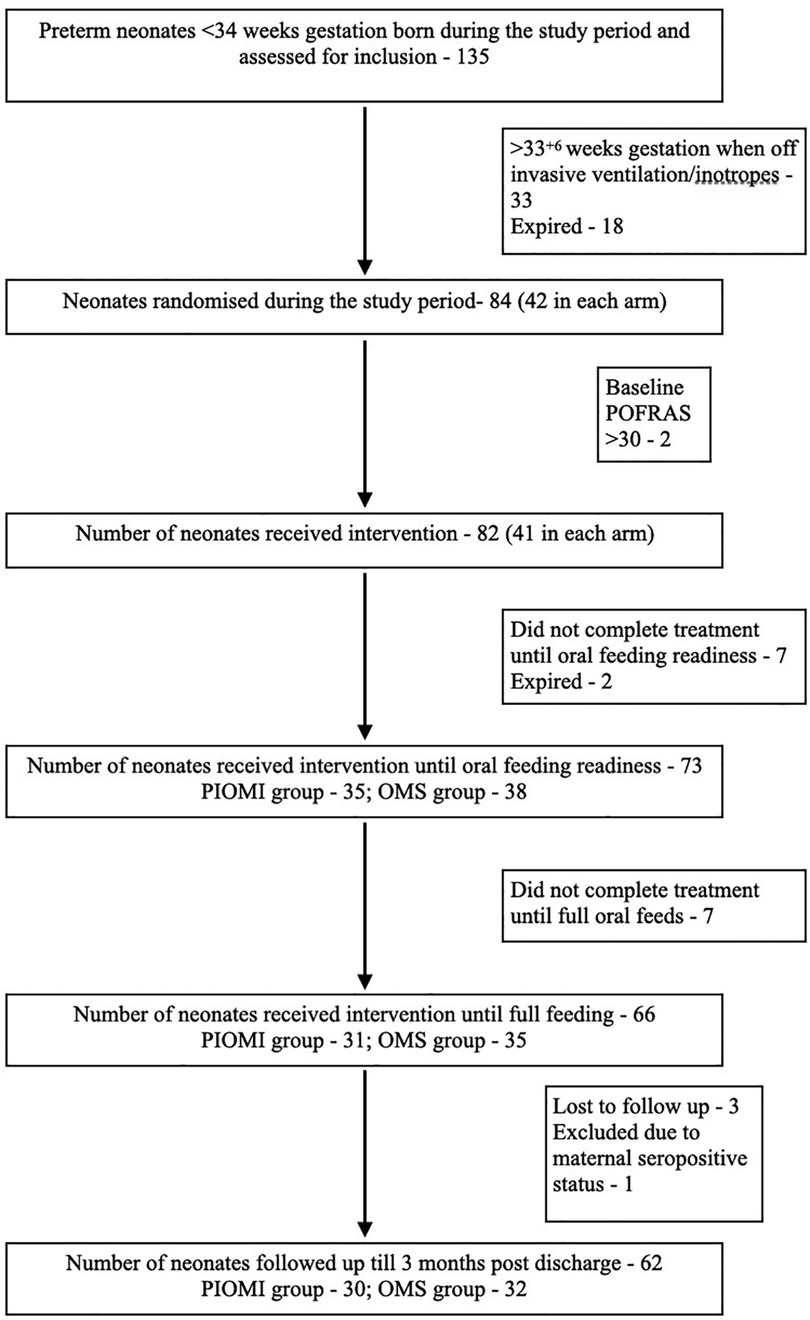

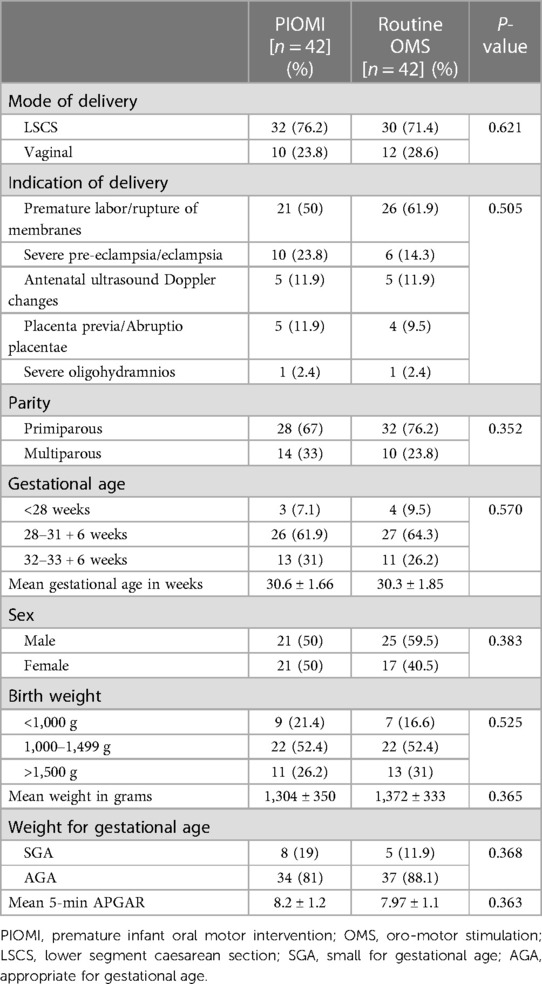

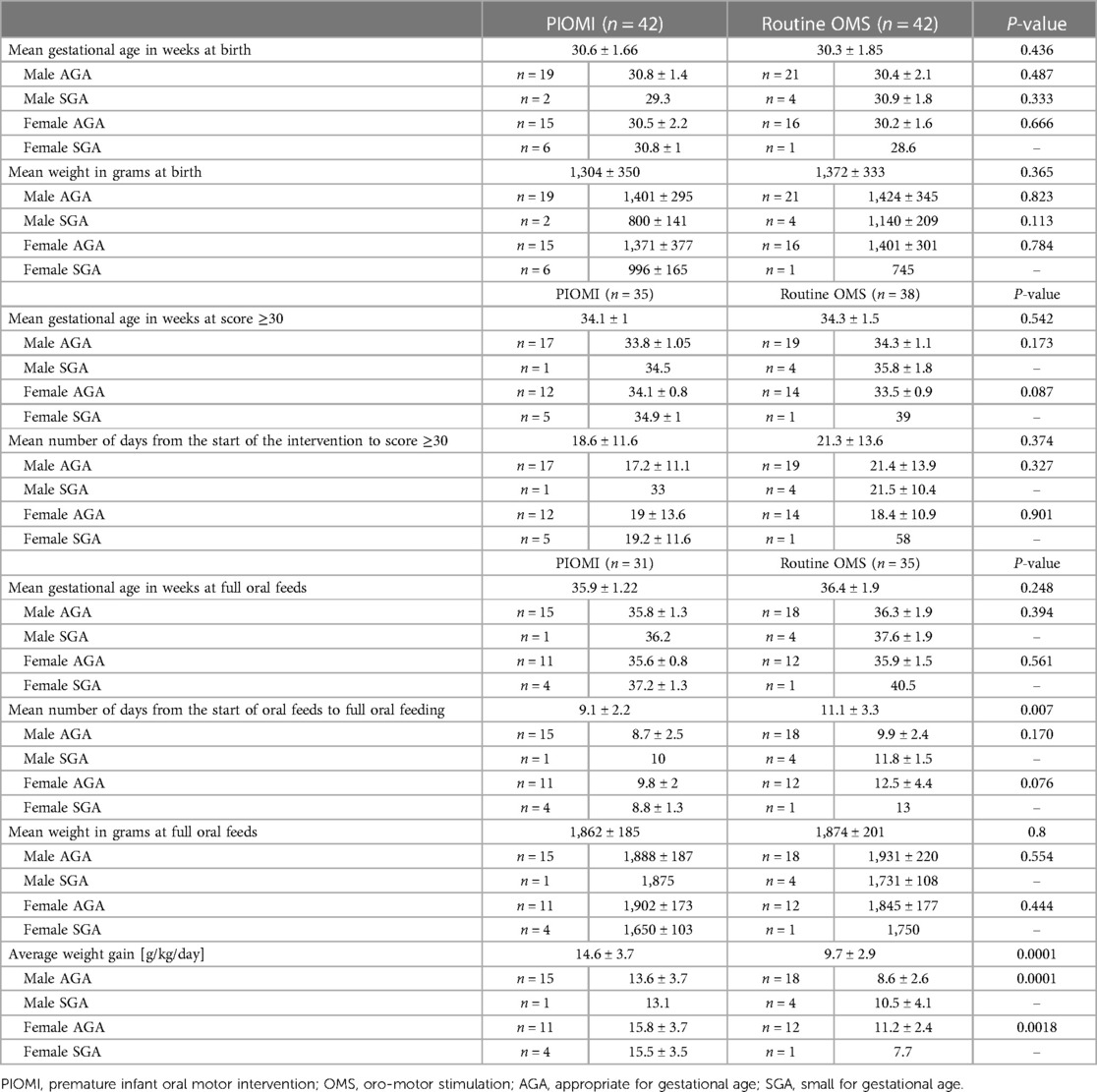

The study included 84 neonates divided into two groups of 42 each to receive either PIOMI or routine OMS. The study flowchart is described in Figure 1. At birth, the mean gestational age (GA) of the neonates in the PIOMI and OMS groups was 30.6 and 30.3 weeks, respectively, and the mean birthweight was 1,304 and 1,372 g, respectively. The maternal and neonatal characteristics were comparable for both groups (Table 1).

The mean CGA in both groups at the start of intervention was 31.4 weeks (P- 0.851) and the mean birthweight was 1,245 and 1,323 g (P- 0.256), respectively, for PIOMI and OMS.

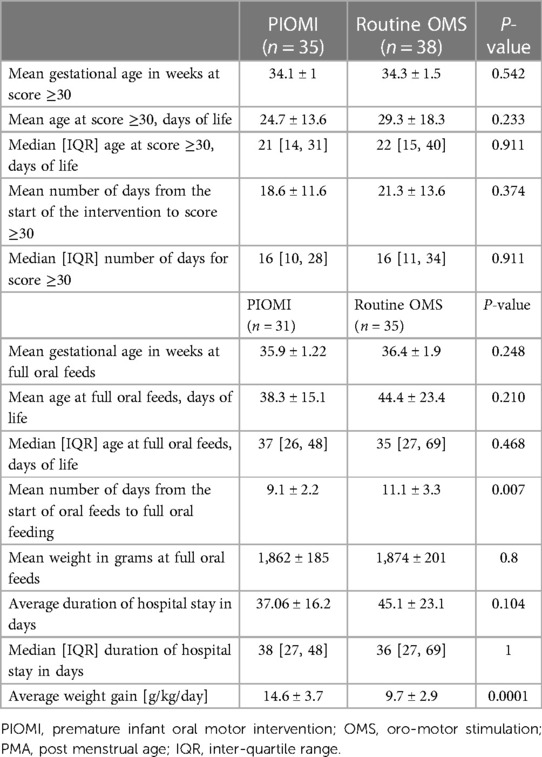

Although the CGA at POFRAS score ≥30 was similar for both groups, the chronological age was lower by 4.6 days for the PIOMI group (P- > 0.05) and these neonates achieved oral feeding readiness 2.7 days earlier (P- > 0.05) (Table 2). This primary outcome was assessed for 73 neonates who completed treatment until oral feeding readiness was achieved.

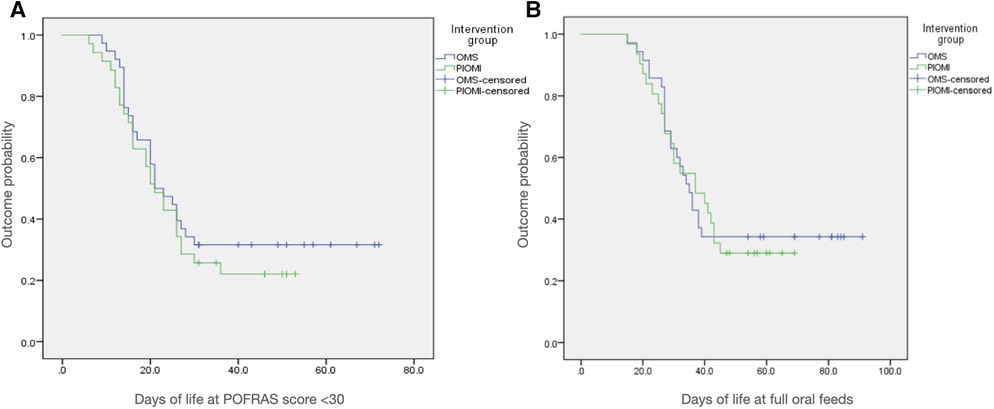

As per Kaplan–Meier analysis, the probability of not achieving oral feeding readiness by 30 days of life (DOL) was lower for the PIOMI group (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier analysis curves for the probability of (A) not achieving oral feeding readiness by 30 days of life and (B) not achieving full oral feeds by 45 days of life.

Out of 66 neonates followed until discharge, the CGA at full oral feeds was 35.9 and 36.4 weeks, respectively, for PIOMI and OMS (P- > 0.05). The age for full oral feeds was 6.1 DOL lower, the transition time from initiation to full oral feeds was 2 days less, and the duration of hospitalisation was 8 days less for the PIOMI group (P- > 0.05). The average weight gain was higher by 4.9 g/kg/day with PIOMI (P- < 0.05) (Table 2).

As per Kaplan–Meier analysis, the probability of not achieving full oral feeds by 45 DOL was lower for the PIOMI group (Figure 2B).

A subgroup analysis for the progression of feeding characteristics of the study sample from birth till the achievement of full oral feeds was done for sex and weight for gestational age (Table 3). A statistically significant result could only be achieved for average weight gain from initiation to achievement of full oral feeds.

Table 3. Progression of feeding characteristics of the study sample from birth till achievement of full feeds based on sex and weight for gestational age.

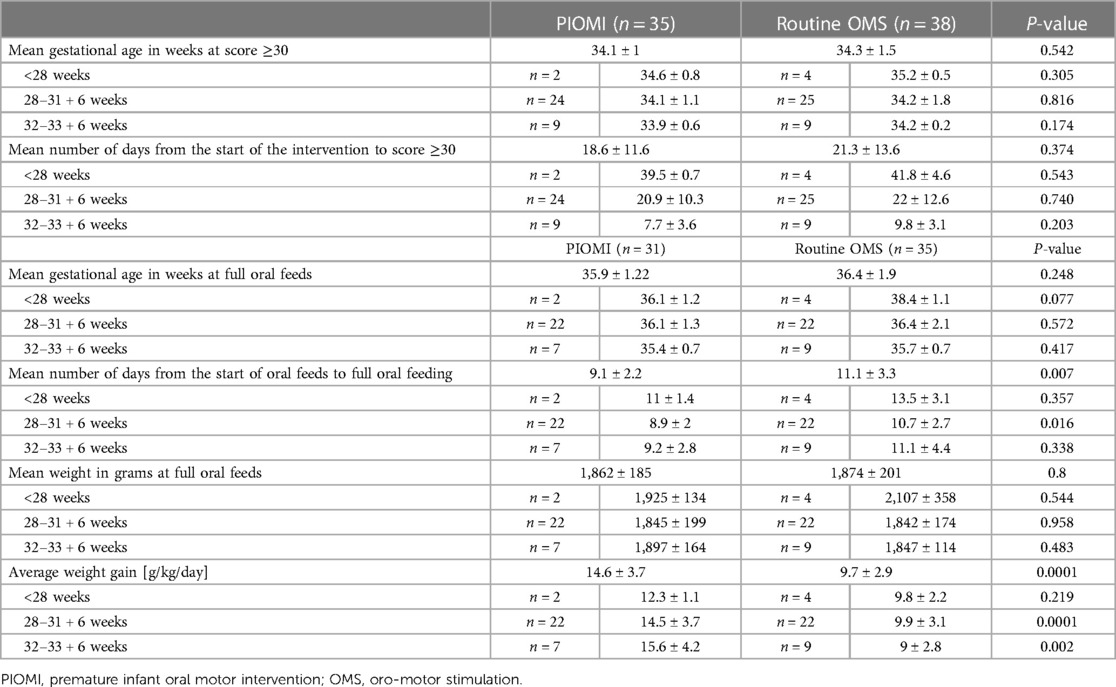

The subgroup analysis for the feeding characteristics based on gestational age (Table 4) favoured the PIOMI group, however, a statistically significant inference could only be drawn for transition to full oral feeds for neonates 28+0–31+6 weeks gestation and average weight gain on oral feeds for neonates >28 weeks gestational age.

Table 4. Progression of feeding characteristics of the study sample from birth till achievement of full feeds based on gestational age.

A total of 62 neonates were assessed for breastfeeding till 3 months post-discharge. The exclusive breastfeeding rate was higher by 24.5% (P- 0.015) at 1-month post-discharge in the PIOMI group (per protocol analysis) and by 14.37% (P- 0.185) (per intention to treat analysis). At 3 months post-discharge, 27% (P- 0.022) more neonates in the PIOMI group were on exclusive breastfeeding (per protocol analysis) and 16.6% (P- 0.128) (per intention to treat analysis).

Although not statistically significant, the odds of achieving oral feeding readiness and establishment of full oral feeds were higher in the PIOMI group. The odds of exclusive breastfeeding at 1 and 3 months post-discharge were significantly higher in the PIOMI group as compared to OMS (Figure 3).

Discussion

In this study comparing the effect of two methods of oromotor stimulation on readiness for oral feeding in preterm neonates, we did not find a significant difference. We, however, noted the significantly earlier transition from initiation to full oral feeds, better weight gain, and post-discharge breastfeeding rates in the structured method of oromotor stimulation (PIOMI).

Our study had comparable baseline characteristics with the previous studies (5, 8, 10). Most of the neonates in both groups were of GA 28+0–31+6 weeks with a birthweight ranging from 1,000 to 1,499 g, which was appropriate for GA. However, as opposed to the previous studies (5, 8, 10), in which, intervention was started after attaining a pre-specified gavage feeding volume, in our study, the neonates were included as soon as they were clinically and hemodynamically stable and a minimum feeding volume was not considered necessary for beginning the intervention. Furthermore, most of the previous studies compared PIOMI to routine care where the control groups had not received any form of oral motor stimulation.

Both the intervention groups achieved oral feeding readiness at a similar CGA and a trend for lower chronological age for oral feeding readiness was noted with PIOMI but this was not statistically significant. The probability of achieving oral feeding readiness by 30 DOL was higher with PIOMI.

Similar to our observation, Sumarni et al. (11) evaluated oral feeding readiness by POFRAS score before and after administration of 7 days of oral motor stimulation and observed that the neonates receiving PIOMI had a higher increment in post-POFRAS scores but the result was not statistically significant. Variability in statistical significance has also been observed for this outcome in other studies, most of which did not utilise any feeding readiness assessment tool (8, 10, 12).

The lower CGA and chronological age for achieving full oral feeds for the PIOMI group was not statistically significant, however, a significantly faster transition to full oral feeding was observed with PIOMI. The probability of achieving full oral feeds by 45 DOL was also higher with PIOMI. Some of the previous studies have also suggested a shorter transition time to full oral feeds using PIOMI (5, 6, 10, 13, 14). The difference in the days to independent oral feeding as compared to the present study could be attributed to variable methodology.

Neonates in the PIOMI group in our study could be discharged 8 days earlier. Similarly, Arora et al. (5) reported that neonates receiving PIOMI could be discharged earlier as compared to sham intervention (P > 0.05). Some of the other studies have observed a statistically significant reduction in the duration of stay with PIOMI, however, the control groups in these studies had not received any form of oral motor stimulation (4, 6, 8, 12, 14–16).

Although the difference between the groups for oral feeding readiness, full oral feeding, and duration of hospitalisation was not statistically significant, each day saved in terms of clinical management has a significant implication on the expenditure for the affected family and the healthcare system. Earlier initiation and achievement of oral feeds will help to establish the emotional bond between the mother-infant dyad and enhance the mother's confidence in feeding and taking care of the neonate. Decreased duration of hospitalisation would reduce the financial burden on the family, especially in a low-middle income setting. Additionally, this will have a profound effect on the available health resources and the economics of the health structure.

The neonates receiving PIOMI had significantly higher weight gain on oral feeds in our study. A similar observation was noted in the study by Thakkar et al. (10). This may indirectly be indicative of better oral feeding efficiency and milk volume transferred in each feed, as has been suggested by some previous studies (7, 10, 17) in favour of PIOMI. However, overall the results have been variable (6, 8). This could be attributed to not following a feeding readiness assessment scale across the previous studies, which may have subjectively altered the judgement of feeding efficiency.

While the subgroup analysis as per sex, weight for gestational age, and gestational age did not reveal statistically significant differences for all study outcomes, it favoured the PIOMI group, particularly the neonates >28 weeks gestation. The results of individual analyses, however, need interpretation, taking into account the small sample size.

The exclusive breastfeeding rates in the present study were significantly higher after discharge in the neonates who had received PIOMI per protocol (p < 0.05). The OR analysis of the same also favored PIOMI, with statistical significance. This finding supports that PIOMI improves the feeding efficiency in preterm neonates (7, 10, 17). Sasmal et al. (8) observed higher breastfeeding rates with PIOMI at 1 month after discharge. Skaaning et al. (9) evaluated the effect of a parent-administered PIOMI-based oral motor stimulation method. Both studies, however, could not establish a significant impact on exclusive breastfeeding with PIOMI. This could be speculated to lower sample size (8), variable methodology, and caregiver-dependent method of PIOMI.

The abovementioned observations suggest that although a structured form of oral motor stimulation may not have resulted in statistically significant differences in initiation and attainment of oral feeds, its effects on improving oral feeding efficiency and exclusive breastfeeding rates are evident.

Our study has several strengths. More than the required number of participants were recruited to achieve statistical power. Both structured and unstructured methods of oral motor stimulation were compared in the present study, thereby, assessing the overall effect of various methods of oral motor stimulation utilised in clinical settings. Additionally, the intervention was started as soon as the neonate was hemodynamically stable, as has been suggested by Lessen et al. (4). The oral feeding was established as per validated scoring systems and not based on subjective assessment. However, the study is not devoid of limitations. It is a single-centre study and, therefore, the findings may not be generalizable. Although the intervention providers were blinded to the weekly POFRAS assessment and scores, the blinding of study participants at the time of providing intervention could not be achieved. The allocation concealment for randomisation was also not performed. Data on maternal education and socio-economic status was not collected, which may have been significant attributing factors for exclusive breastfeeding.

Conclusion

The neonates receiving PIOMI showed higher weight gain and exclusive breastfeeding rate post-discharge. This suggests improvement in feeding efficiency with a structured intervention. Although a statistically significant difference could not be derived for all outcomes, it may still offer clinical benefit for the patient and the treating facility. We, thus, recommend PIOMI to be more effective for improved oral feeding in preterm neonates 29+0–33+6 weeks GA. However, multicentric trials with larger sample sizes would be necessary to further strengthen the recommendation.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Ethics Committee, Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be) University Medical College. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

PS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. NM: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AK: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. RG: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. AV: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. NN: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PS: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the participating neonates and their parents, especially the mothers for being compliant, the nurses who performed the oromotor stimulation without which the study could not have been possible, and the health institution for allowing us to carry out the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2023.1296863/full#supplementary-material

References

1. WHO. Global nutrition targets 2025: Low birth weight policy brief (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.5). Geneva: World Health Organization (2014).

2. Lau C. Development of suck and swallow mechanisms in infants. Ann Nutr Metab. (2015) 66(5):7–14. doi: 10.1159/000381361

3. Lau C. Development of infant oral feeding skills: what do we know? Am J Clin Nutr. (2016) 103(2):616S–21S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.109603

4. Lessen BS. Effect of the premature infant oral motor intervention on feeding progression and length of stay in preterm infants. Adv Neonatal Care. (2011) 11:129–39. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e3182115a2a

5. Arora K, Goel S, Manerkar S, Konde N, Panchal H, Hegde D, et al. Prefeeding oromotor stimulation program for improving oromotor function in preterm infants—a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. (2018) 55(8):675–8. doi: 10.1007/s13312-018-1357-6

6. Ghomi H, Yadegari F, Soleimani F, Knoll B, Noroozi M, Mazouri A. The effects of premature infant oral motor intervention (PIOMI) on oral feeding of preterm infants: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2019) 120:202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.02.005

7. Lessen Knoll BS, Daramas T, Drake V. Randomized controlled trial of a prefeeding oral motor therapy and its effect on feeding improvement in a Thai NICU. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2019) 48(2):176–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2019.01.003

8. Sasmal S, Shetty AP, Saha B, Knoll B, Mukherjee S. Effect of prefeeding oromotor stimulation on oral feeding performance of preterm neonates during hospitalization and at corrected one month of age at a tertiary neonatal care unit of India: a randomized controlled trial. J Neonatol. (2023) 37(2):149–58. doi: 10.1177/09732179221143185

9. Skaaning D, Carlsen E, Brødsgaard A, Kyhnaeb A, Pedersen M, Ravn S, et al. Randomised oral stimulation and exclusive breastfeeding duration in healthy premature infants. Acta Paediatr. (2020) 109(10):2017–24. doi: 10.1111/apa.15174

10. Thakkar PA, Rohit HR, Ranjan Das R, Thakkar UP, Singh A. Effect of oral stimulation on feeding performance and weight gain in preterm neonates: a randomised controlled trial. Paediatr Int Child Health. (2018) 38(3):181–6. doi: 10.1080/20469047.2018.1435172

11. Sumarni S, Sutini T, Hariyanto R. Differences in effectiveness of the premature infant oral motor intervention (PIOMI) and oromotor stimulation (OMS) on feeding readiness. Health Sci J Indones. (2021) 11(01):29–34. doi: 10.33221/jiiki.v11i01.943

12. Mahmoodi N, Lessen B, Keykha R, Jalalodini A, Ghaljaei F. Theeffect of oral motor intervention on oral feeding readiness and feeding progression in preterm infants. Iran J Neonatol. (2019) 10(3):58–63. doi: 10.22038/ijn.2019.34620.1515

13. Bandyopadhyay T, Maria A, Vallamkonda N. Pre-feeding premature infant oral motor intervention (PIOMI) for transition from gavage to oral feeding: a randomised controlled trial. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. (2023) 16(2):361–7. doi: 10.3233/PRM-210132

14. Thabet AM, Sayed ZA. Effectiveness of the premature infant oral motor intervention on feeding performance, duration of hospital stay, and weight of preterm neonates in neonatal intensive care unit: results from a randomized controlled trial. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. (2021) 40(4):257–65. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000475

15. Mahmoodi N, Zareii K, Mohagheghi P, Eimani M, Rezaei-Pour M. Evaluation of the effect of the oral motor interventions on reducing hospital stay in preterm infants. Bihdad. (2013) 2(3):163–6. doi: 10.18869/acadpub.aums.2.3.163

16. Guler S, Cigdem Z, Lessen Knoll BS, Ortabag T, Yakut Y. Effect of the premature infant oral motor intervention on sucking capacity in preterm infants in Turkey: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Neonatal Care. (2022) 22(6):E196–206. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000001036

17. Rearkyai S, Daramus T, Kongsaktrakul C. Effect of oral stimulation on feeding efficiency in preterm infants. Thai Pediatr J. (2014) 21(3):17–23. Available at: https://www.piomi.com/_files/ugd/3400b9_8a861020ed9b44c89ee560e372aec730.pdf

Keywords: neonate, oral motor stimulation, prematurity, oral feeding readiness, exclusive breastfeeding

Citation: Singh P, Malshe N, Kallimath A, Garegrat R, Verma A, Nagar N, Maheshwari R and Suryawanshi P (2023) Randomised controlled trial to compare the effect of PIOMI (structured) and routine oromotor (unstructured) stimulation in improving readiness for oral feeding in preterm neonates. Front. Pediatr. 11:1296863. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1296863

Received: 19 September 2023; Accepted: 23 October 2023;

Published: 16 November 2023.

Edited by:

Tina Marye Slusher, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United StatesReviewed by:

Beverly Curtis, Keystone Health, United StatesMargaret Nakakeeto, Ministry of Health, Uganda

© 2023 Singh, Malshe, Kallimath, Garegrat, Verma, Nagar, Maheshwari and Suryawanshi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pradeep Suryawanshi ZHJwcmFkZWVwc3VyeWF3YW5zaGlAZ21haWwuY29t

Abbreviations PIOMI, premature infant oral motor intervention; OMS, oromotor stimulation; POFRAS, premature oral feeding readiness assessment scale; CGA, corrected gestational age; DOL, days of life.

Pari Singh

Pari Singh Nandini Malshe

Nandini Malshe Aditya Kallimath1

Aditya Kallimath1 Pradeep Suryawanshi

Pradeep Suryawanshi