- 1Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, St Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 2Duke Department of Pediatrics, Duke School of Medicine, Durham, NC, United States

- 3Duke Global Health Institute, Durham, NC, United States

- 4Department of Pediatrics, Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH), Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria

- 5Division of Neonatology and Bioethics Center, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO, United States

- 6Department of Pediatrics and Department of Medical Humanities and Bioethics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, MO, United States

- 7College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Worldwide, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest burden of global neonatal mortality (43%) and neonatal mortality rate (NMR): 27 deaths per 1,000 live births. The WHO recognizes palliative care (PC) as an integral, yet underutilized, component of perinatal care for pregnancies at risk of stillbirth or early neonatal death, and for neonates with severe prematurity, birth trauma or congenital anomalies. Despite bearing a disproportionate burden of neonatal mortality, many strategies to care for dying newborns and support their families employed in high-income countries (HICs) are not available in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs). Many institutions and professional societies in LMICs lack guidelines or recommendations to standardize care, and existing guidelines may have limited adherence due to lack of space, equipment, supplies, trained professionals, and high patient load. In this narrative review, we compare perinatal/neonatal PC in HICs and LMICs in sub-Saharan Africa to identify key areas for future, research-informed, interventions that might be tailored to the local sociocultural contexts and propose actionable recommendations for these resource-deprived environments that may support clinical care and inform future professional guideline development.

Introduction

The death of a child is one of the most devastating human experiences, often resulting in profoundly negative long-term physical and psychosocial consequences on parents (1–3). Stillbirth and early neonatal death is uniquely a loss of both the physical and the envisioned life of the infant (4). The consequent maternal grief typically occurs in private, and is often under-recognized or ignored by the community (5).

Worldwide, more than 2.4 million neonatal deaths (6) and 2.6 million stillbirths occur annually, 98% of which are in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) (7). Though neonatal mortality worldwide has substantially improved over the past two decades, it has lagged behind those achieved in under-five children; neonatal mortality still contributes 47% of under-five mortality (6, 7).

In the United States, nearly half (46%) of all deaths in children under 19 years old occur in the first year of life, and two-thirds (66%) of infant deaths occur in the neonatal period (8, 9). Worldwide, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest burden of global neonatal mortality (43%) and neonatal mortality rate (NMR): 27 deaths per 1,000 live births (6). The World Health Organization's Every Newborn Action Plan goal is to achieve a NMR below 12 deaths per 1,000 live births by 2030 (6), but, thus far, only 4/48 (8%) countries have achieved such (10).

Palliative care (PC) is the multidisciplinary prevention or amelioration of pain and other physical, psychosocial or spiritual problems in patients with life-limiting or life-altering conditions and their families with the aim of improving quality of life (11). The WHO recognizes PC as an integral, yet underutilized, component of perinatal care for pregnancies at risk of stillbirth or early neonatal death, and for neonates with severe prematurity, birth trauma or congenital anomalies in both high-income countries (HICs) and LMICs (12). Despite bearing a disproportionate burden of neonatal mortality, many strategies to care for dying newborns and support their families employed in HICs are not available in LMICs. Likewise, many institutions and professional societies in LMICs lack guidelines or recommendations to standardize care, and existing guidelines may have limited adherence due to lack of space, equipment, supplies, trained professionals, and high patient load (13). Gaps in provision of newborn intensive care and opportunities for improvement have been identified in the literature previously (13–16). In this narrative review, we compare perinatal/neonatal PC in HICs and LMICs in sub-Saharan Africa to identify key areas for future, research-informed, interventions that might be tailored to the local sociocultural contexts and propose actionable recommendations for these resource-deprived environments that may support clinical care and inform future professional guideline development.

Neonatal end-of-life care in high income countries

In HICs, it is recommended that compassionate care for patients with life-limiting or life-altering conditions should begin as soon as a relevant diagnosis is made, including prenatally (17, 18). However, referral for prenatal/neonatal PC counseling, or bereavement counselling following perinatal loss remains variable (19–22). Even the training of neonatologists in end-of-life (EOL) care provision remains variable (23).

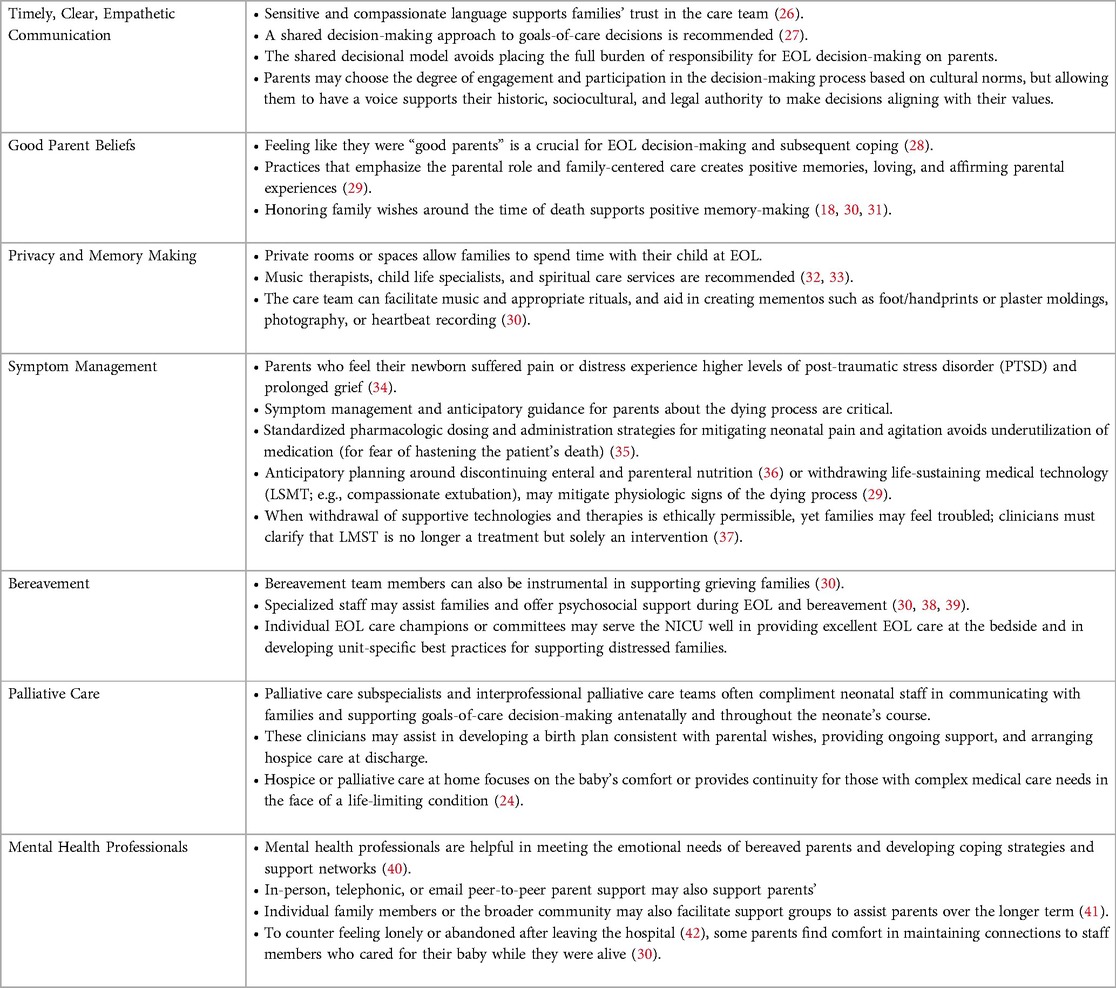

Approaches to EOL care for newborns have been empirically studied in the United States and other HICs. These data increasingly inform the creation of standardized care guidelines, policies, and educational opportunities (24), to ensure high-quality care is delivered to each patient while also addressing the unique needs of every patient and family (25). Findings from this research highlight the importance of timely, clear, and empathetic communication and decision-making (26, 27); supporting good parent beliefs (18, 28–31); privacy and memory-making (30, 32, 33); symptom management (29, 34–37); bereavement (30, 38, 39); and the role of palliative care subspecialists (24) and mental health professionals (30, 40–42) (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of elements of high quality perinatal/neonatal palliative care in high income countries.

Neonatal end-of-life care in low- and middle-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa

Though pediatric PC in LIMCs has witnessed some growth in the past several years, this has largely focused on supporting EOL care for older children with conditions like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and malignancies (15, 43–45). Perinatal-Neonatal PC is poorly described in global resource-constrained settings, with the limited existing literature focused on how cultural and structural factors limit support of mothers who have suffered stillbirths (46–49). In LMICs, differences in the socio-cultural, religious/spiritual and legal environment, with limited and inconsistently available resources limit the applicability of evidence-based approaches derived in HICs. However, there are actionable steps that may address PC needs, improve bedside care and provide opportunity to develop research-informed interventions (50).

Communication around serious news

Physicians practicing in LMICs are faced with considerable challenges and barriers to communicating serious news to parents. Language and cultural barriers impact communication around EOL and bereavement care in sub-Saharan Africa, partly because multiple languages/dialects are spoken in most countries (51–54). Differences in education level, health literacy, and health beliefs between clinicians and parents/families also create challenges in clinical care, particularly in settings where trained medical interpreters do not exist (55, 56). For example, the local word used for “Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)” may not convey that it is an intensive care unit, making it hard for parents to conceptualize the care provided (56). Cultural norms also impede parents' and families' willingness to express that they do not understand medical information being explained to them or to ask questions of healthcare professionals.

Unlike HICs, where ultrasonography, genetic testing, and other prenatal evaluations may identify which newborns are likely to be imperiled or have a poor prognosis, such anticipation is only recently being provided in LMICs with the expanding use of ultrasound (57). Thus, many perinatal/neonatal deaths happen unexpectedly, without adequate preparation and discussion with the family. Even when critical illness is anticipated, without ample resources or clinician training in communication skills, these deaths may still be complicated and distressing for families. Frequently, the counseling for such scenarios may be done by various individual clinicians in the obstetrical or pediatric setting without the full team of physicians who will be involved in the care. Inconsistent messaging or forecasting may result—confusing parents, creating doubt, or leading to mistrust of the clinicians and their prognostication. For example, if a mother is counseled that her newborn will die immediately after birth, but the baby survives for several days, or longer, it is likely to be distressing for both the mother and the family.

Limited communication undermines parents’ trust and cause families to attribute an infant's death to poor medical care (14, 51, 58). Therefore, clinicians, even while providing clear and consistent messaging about the infant's condition and prognosis, must also acknowledge and explain uncertainties. Currently, there are limited published studies offering insight into preferred phrasing or approaches to these conversations (46). Further research exploring how parents wish to be told difficult news about their newborn's diagnosis and prognosis and how best to engage them in goals-of-care discussions and decision-making are needed.

For physicians-in-training, serious news communication may be especially challenging. Currently, while didactics in ethics may be provided, mentorship and training in communication skills may be inadequate. Clinicians may experience anxiety around difficult conversations and parents may misconstrue the doctor as incompetent. Such discomfort, paired with the time constraints of managing a busy newborn service, may lead the clinician to deprioritize these discussions or even avoid them altogether (46).

Availability of Pediatric PC training is limited in sub-Saharan Africa, therefore physicians lack the support of these subspecialists in complex communication and decision-making. However, models utilizing medical and nursing students, and lay community healthcare workers have been described as stop-gap measures (16). Though the World Health Organization (WHO) explicitly recognizes PC as human right to health (11), funding is needed to develop these capabilities in already over-burdened health systems. National health policies should prioritize developing programs that teach interdisciplinary and interprofessional clinicians, including obstetricians, pediatricians/neonatologists, and nurses, communication approaches and bedside perinatal/neonatal PC skills.

Recommendations:

1. Once the risk of serious illness and death is identified, clinicians should involve parents/family in discussions about their infant's diagnosis and prognosis as soon as possible. Parental understanding of their infant’s condition, treatments, and care options available–as well as uncertainty and the limits of medicine–should be supported.

2. All clinicians, but especially doctors, should communicate clearly with parents/family, preferably in their own language, using clear, culturally sensitive terms that they understand. This may require the counselor to spend extra time to explore parental educational and socio-cultural backgrounds and health literacy.

3. Medical Schools and hospitals should provide communication skills training; health workers should be trained periodically in these skills, ideally every 3–5 years.

4. Hospitals and professional societies should recognize and encourage motivated health workers who advocate and practice PC.

5. National-level health policies should prioritize funding for program development around EOL communication skills and care provision and subspecialty trainings in pediatric PC.

6. Perinatal/neonatal PC should be integrated into all existing or new perinatal/neonatal guidelines e.g. Helping Babies Breathe.

Preferences of parents and families for palliative and bereavement care

Due to the varied social, cultural, and resource considerations perinatal palliative care and bereavement interventions designed for HICs may not be applicable for the needs of LMICs (50). Research into parents' preferences in bereavement care, in sub-Saharan Africa is currently limited (46); further investigation is much needed. For example, “memory making”, a cornerstone of perinatal bereavement in HICs (59–62), is less practiced in LMICs (47). HIC studies report that the use of photos, mementos, and spending time sitting with or holding the deceased infant can help create a lasting sense of identity for the deceased (59), mitigate parental psychological distress, and influence the resolution of grief (63, 64). Though evidence-based approaches that are culturally-appropriate and tailored to individual parents in LMICs are sparse, efforts can be made to personalize the end-of-life experience for parents and families. Parents should be asked about any preferences for religious or cultural practices that they desire for their infant, and all reasonable efforts to honor these requests should be made to preserve dignity and respect for the patient and family (13). This could mean engaging religious and traditional leaders considered to be beneficial due to their societal stature, heritage, or clerical stature (47, 50).

Parents in LMICs may hold a wide range of values around the meaningfulness of being present during the death of their newborn. While some parents may align with parents in HICs, where studies suggest that seeing and holding one's deceased baby is helpful (65, 66), others may find holding and caring for their neonate in critical condition traumatizing and painful. They may instead prefer to remember or imagine their child as the beautiful, healthy baby. Parental presence at the death of a newborn is currently contrary to some LMICs normative practice. A Nigerian study revealed that only half of women experiencing stillbirth were allowed to see the body of their infant, and none were given the opportunity to hold the infant, although many would have liked to do so (67). Mothers may be discouraged from holding the child's body or thinking about the baby to shield her from emotional and psychological harm (51, 68). To respect and support the plurality of parents' values and perspectives, they should be offered the opportunity, but not pressured, to be present while their infant passes away and their wishes should be accommodated. Often there are space constraints in the NICU, though if a quiet, calming, private space exists, it should be provided to allow parents the free expression of their emotions. Families choosing to be with their infant as they die may have different preferences about other medical care team members being present with them at this time. If parents so desire, efforts should be made to accommodate this, though the absence of social-workers, peer-parent supporters, and NICU-psychologists may create challenges for busy NICU clinicians. Individual parents may also differ on their preferences for memory-making and bonding, and these preferences may be influenced by cultural norms (47). Opportunities for parents to take photographs of their infants, and, if possible, to retain mementos from the hospitalization such as blankets the baby was wrapped in, clothing or a hat that the child wore may be meaningful and comforting to parents in processing their grief (50). However, care should be taken to ensure that such items are not contaminated with potentially infectious body fluids or fomites.

No studies have investigated parents' perceptions of suffering at end-of-life for newborns in LMICs, though they may have similar experiences to parents in HICs. Cultural adages, such as the Ethiopian saying, “blessed are those who have a comforting death” suggest that, in the absence of evidence, care practices to mitigate symptoms in dying neonates are appropriate. Many premature neonates die due to primary central apnea and progressive hypercapnia and hypoxia, without the subjective feeling of “air hunger,” or visible tachypnea, dyspnea, or agitation (69). For gestationally older newborns or those dying of potentially painful disease processes, sedative or analgesic medications should be provided by intravenous, oral, or intranasal route. These include opiate medications such as morphine, fentanyl, or benzodiazepines such as lorazepam or midazolam (70).

Recommendations:

1. If a newborn's death seems imminent, clinicians should inquire about parents preferences around EOL care and attempt to honor their wishes.

2. Clinicians should ask parents if they wish to be alone with their child at the time of death or if they wish for the medical team or family to be present with them and honor their request.

3. Hospitals should devote a space for EOL care and bereaved parents that is quiet, calming, and private, where possible.

4. Hospitals should consider investing in interprofessional clinician roles, such as social-workers, peer-parent supporters, or psychologists to support parents through the EOL and bereavement processes.

5. Hospitals should foster opportunities for memory-making and offer parents mementos, if desired, of their newborn's time alive in the hospital.

6. Healthcare providers are also negatively impacted by perinatal deaths but often neglected in provision of palliative services; thus, they may also benefit from psychosocial support and debriefing.

Impact of social and cultural traditions and stigmas on parental grief and mental health

Death of a newborn or fetus is distressing for the parents, which may be worsened by feelings of isolation. While some cultures may view the death of a newborn as the same as any other person, in many cultures, neonatal loss may be viewed differently than for older children and adults. For this reason, in communities where there are cultural and societal traditions for the loss of older patients, comparatively little may be done for parents during the loss of their newborn. For example, in some cultures within Ethiopia, the death of the newborn, especially less than 3 days old, is not considered as a death of a person (14, 68). Social gatherings, burial ceremonies and religious activities, which may be meaningful to some bereaved parents to feel supported and cope with their loss, may not be done in others. Similarly, bereaved parents who wish to claim their newborns body for formal burial may be stopped by hospitals or extended family members. As the rite of burial may hold symbolic meaning for grief and closure, being inhibited in claiming the newborn's body may heighten parents' distress. Hospital policies which neither obligate nor prohibit parents' taking of the newborn's body, coupled with clinician counseling that normalizes diverse cultural and religious practices, may support parents' preferences around their newborn's death.

Cultural practices intended to protect bereaved parents may inadvertently heighten their trauma. In many cultures, discussing the death of a newborn may be considered taboo, or even dangerous, if that culture endorses beliefs that doing so could cause future losses (47). The hidden nature of stillbirth and neonatal loss is embedded in the social construction of personhood, a phenomenon seen most commonly in regions with high NMR (47, 71–73) Often, unique practices around newborn death exist to protect the woman from emotional and psychological harm (68) and protect her future fertility (51, 68). Likewise, well-meaning family and friends may reassure parents that they will “have another baby” rather than acknowledge the loss of this child (14). While these contrast what might comfort bereaved parents in HICs, few studies of bereaved parents in these settings have explored whether parents in these cultures perceive these practices to be protective or not (46, 47). However, even in cultures where directly discussing the newborn death is discouraged, friends, neighbors, and community members may provide grief support by caring for the bereaved parent, bringing food, offering prayers, and keeping company so that they are not alone. Perinatal PC intervention development efforts must be aware of cultural variations in beliefs and customs, while recognizing that pregnancy is a highly personal experience (46). Further research into how core elements of HIC bereavement care packages can translate to LMICs and what new, culturally tailored, interventions need to be developed to guide practice is warranted (50).

Fathers also experience negative mental health outcomes and financial losses following a perinatal death (46), yet remain an understudied group both in HICs and LMICs. Reviews from HICs describe men as having less intense and less enduring levels of negative psychological outcomes, but a greater likelihood of engaging in compensatory behaviors such as alcohol use (74, 75), In LMICs, men may feel marginalized since their female partner's grief is often more visible, and their grief may be heightened from having restricted opportunity to engage with their newborn in the hospital while alive (13). Other works have shown that while perinatal loss can create conflict in some couples, it can lead to a greater sense of closeness in others (76).

In many LMICs, cultural norms about appropriate male behavior may prevent fathers from openly grieving following the loss of their child (76). This grief suppression can increase the risk of chronic psychological issues (5). Also, healthcare workers may impair parental grieving perinatal deaths if they fail to show adequate empathy or fail to disclose important information such as the (presumed) cause of death (77).

Recommendations:

1. Health workers should understand and acknowledge the grief of parents who have lost a newborn and support them in the bereavement process.

2. Clinicians should explain the cause of death as much as possible, highlighting, if appropriate, that it was not caused by a mistake or misdeed by the mother or father.

3. Hospitals and institutions should empower and support parents in their wishes regarding their newborn's body after death so that religious or cultural customs may be honored.

4. Hospitals and institutions should create opportunities for ongoing support of bereaved parents through ongoing engagement with caregivers who met their child while alive, similar to bereavement follow-up programs in HICs. They should also engage with local communities to identify and integrate hospital-based bereavement support with culturally-appropriate community-based programs and resources.

Life, death, personhood, and the law

Though there remains an ongoing debate in HICs around the moral status of a fetus and when a fetus achieves personhood (78–80), determining which critically-ill neonates should have intensive therapies offered, mandated, or withheld creates complex, but navigable ethical challenges. Regionalization of neonatal intensive care in HICs promotes justice, ensuring that wherever a newborn is delivered they are entitled to the same care options as at any other center. While disparities in neonatal outcomes remain in the United States (81), these are narrower than outcome disparities between urban and rural settings in sub-Saharan Africa. The availability of population outcome data anchors ethical decision-making; for example, discrete gestational-age based thresholds for offering and obligating resuscitation can be defined for extremely premature delivery. For cases in which population data do not exist, such as for serious congenital anomalies or genetic conditions, frameworks exist for guiding the boundaries of parental discretion (82) and identifying which therapies are impermissible, permissible, and obligatory (83). In HIC, Hospital Ethics Committees may assist if there is conflict between parents and clinicians, or the best interest of the neonate is unclear. Shared decision-making between clinicians and parents is recommended in situations where outcomes are uncertain and the acceptability of the outcomes are based on personal values, such as feelings about quality of life (27, 84). Such considerations may be aspirational in LMICs in view of healthcare capacity, communitarian approaches to decision-making, and cultural norms.

In resource-constrained settings, what is defined as life-limiting or life-altering may be inconsistent across hospitals within the region and country. Instead, a “life-limiting” congenital anomaly with expected early demise is based upon whether the hospital can treat the condition, which can vary from day-to-day within the same hospital based on availability of equipment, supplies, and personnel. Significant disparity in survival remains for extremely premature infants, often referred to as the “90:10 survival gap,” noted between likelihood of survival in HICs:LMICs (85). Over 90% of babies born before 28 weeks gestation survive in HICs but only about 10% of babies in this same gestational age range survive in LMICs. Though outcomes in HICs remain variable at early gestational ages (86–89), guidance from professional organizations bound resuscitation decisions to a somewhat narrow gestational age range (90–92). Regionalization and well-resourced transport systems ensure that critically ill newborns may receive care at centers that are able to meet their needs (93). This is largely not so in many LMICs where there is wide disparity in the resources and expertise for quality care of extreme preterm infants, often necessitating continued adoption of the 28-week cut-off viability age for ethical-legal reasons (94). Frameworks for considering peri-viability resuscitation decision-making in HICs cannot be directly applied in LMICs (95). Often, no national, regional, or institutional guidelines exist to prescribe a standardized approach to these decisions. The WHO defines “late stillbirth” as fetal deaths at ≥1,000 g or ≥28 weeks of completed gestation for the purpose of standardizing data collection for international pregnancy outcome comparison (85). While clinicians practicing in many LMICs may consider 28-weeks as the “official” gestational age below which any infant “should” be considered a stillbirth or miscarriage, the equitable utilization of resources or the determination that a communitarian vs. individualistic notion of the baby's best interests may be unclear (94, 95). Likewise, a paucity of child-protection laws creates ambiguity around where the limits of parental authority lie, and what healthcare decisions for their neonates are “harmful.” Parents are often personally financially responsible for their newborn's care in the hospital, and whether they are able to pay for care may factor into decisions of what therapies are provided (13). These factors necessitate a different approach to ethical reasoning around neonatal resuscitation and end-of-life care decision-making that both supports the best interest of the infant and also respects values held by parents. This is, particularly important in light of cultural feelings around disability stigma and the limited resources available to support the health and well-being of severely impaired survivors. Additional research into where clinicians and parents/families experience ethical challenges in newborn care are needed to guide development of culturally-relevant and context-specific standardized approaches to ensure justice (96). Regionalization and well-resourced transport systems in LMICs may ensure that critically ill newborns may receive care at centers that are able to meet their needs (93, 97), though challenges in implementation remain (13).

Though several sub-Saharan African countries (98) have ratified the African Union's Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa (99) which requires member-states to “protect the reproductive rights of women by authorizing medical abortions…where the continued pregnancy endangers the mental and physical health of the mother or the life of the mother or the fetus,” (99) abortion laws vary widely among countries (100). In many countries, medically-indicated abortion may be legal after serious fetal diagnosis, although access may still be limited by resource-constraints (101, 102), cultural stigma (103–108), and lack of knowledge and awareness of such provisions amongst both providers or patients (102, 109–111). Complex social/cultural/religious factors also influence abortion decisions, often raising ethical dilemmas and moral distresses among clinicians (112–115). Though studies have investigated how pregnant patients seeking abortion consider these decisions (104, 106, 116–121), few have specifically sought the perspectives of patients who have experienced pregnancies complicated by serious fetal conditions (121). Future research exploring the perspectives of these patients when making decisions around pregnancy termination is needed.

Recommendations:

1. Professional societies should collaborate with legislators and government agencies to prepare country-wide guidelines to standardize counseling and care provision for neonatal conditions. These guidelines should take into consideration the resources at different levels of the health system and the local transport/referral system available to escalate care if needed.

2. Healthcare systems should strive to support regionalization of neonatal care, to ensure that critically ill newborns may be transported to centers matching their care needs.

3. Clinicians should identify individual clinical opportunities for parent engagement and shared decision-making when outcomes are uncertain and values-based.

4. Hospitals should develop pediatric ethics committees to address situations where neonatal best-interest and the role of clinicians and parents in decision-making is unclear or conflicts arise.

5. Clinicians providing perinatal PC to pregnant patients with serious antenatal diagnoses, should be familiar with the local laws regarding abortion to better appropriately guide informed parental choice within the full range of legally-available options, while being sensitive to their socio-cultural and religious preferences. Trauma-informed approaches (122) examining one's own values and biases (123), and practicing cultural humility (124), may help clinicians avoid unduly influencing, pressuring, or stigmatizing patients in these already stressful situations (103, 110, 116).

Integrating palliative care and psychosocial support tools into existing healthcare structures

Considerable gaps remain in the provision of perinatal PC globally, though many of these gaps can be addressed (50). While some approaches to improving this care may be readily available and cost effective (e.g., clinician training), others will require systems-level and policy-level actions. Possibly, some PC elements developed in HIC settings may be translatable to LMICs, while others will require considerable adaptation, and others will remain inappropriate. Empirical and qualitative research exploring clinicians' and parents' perceptions of PC provision in LMICs, and how local culture and resources impact this care, are needed. Likely, new approaches to context-specific perinatal/neonatal PC will be developed as the field grows globally. As neonatal care improves in LMICs, overall mortality may be reduced, but complex decision-making around limitations of therapies may become more common and more difficult, particularly when ICU beds, supportive technologies such as ventilators, or other resources remain constrained. To address these anticipated future changes and challenges, guidelines and recommendations to optimize and standardize current practices of perinatal/neonatal PC and bereavement care for parents are greatly needed, though these should be flexible and re-examined frequently to adapt to future changes.

Author contributions

MA: contributed substantially to the initial draft and critically revised the manuscript. SR: co-conceptualized the paper and critically revised the manuscript. PU: critically revised the manuscript. BC: critically revised the manuscript. SD: critically revised the manuscript. BK: critically revised the manuscript. AM: critically revised the manuscript. SK: conceptualized the paper, contributed heavily to the initial draft, critically revised the manuscript through multiple drafts. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Currie ER, Christian BJ, Hinds PS, Perna SJ, Robinson C, Day S, et al. Life after loss: parent bereavement and coping experiences after infant death in the neonatal intensive care unit. Death Stud. (2019) 43:333–42. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2018.1474285

2. Li J, Laursen TM, Precht DH, Olsen J, Mortensen PB. Hospitalization for mental illness among parents after the death of a child. N Engl J Med. (2005) 352:1190–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033160

3. Brooten D, Youngblut JM, Caicedo C, Del Moral T, Cantwell GP, Totapally B. Parents’ acute illnesses, hospitalizations, and medication changes during the difficult first year after infant or child NICU/PICU death. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2018) 35:75–82. doi: 10.1177/1049909116678597

4. Scott J. Stillbirths: breaking the silence of a hidden grief. Lancet. (2011) 377:1386–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60107-4

5. Burden C, Bradley S, Storey C, Ellis A, Heazell AEP, Downe S, et al. From grief, guilt pain and stigma to hope and pride – a systematic review and meta-analysis of mixed-method research of the psychosocial impact of stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0800-8

6. Newborn Mortality. [Newsroom Fact Sheet]. World Health Organization (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/levels-and-trends-in-child-mortality-report-2021#:∼:text=Globally%202.4%20million%20children%20died,in%20child%20survival%20since%201990

7. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, Say L, Chou D, Mathers C, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. (2016) 4:e98–e108. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00275-2

8. Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. NCHS data brief (no. 456): Mortality in the United States, 2021. (2022). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/122516.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2018–2021 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018–2021, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html on Apr 28, 2023 3:31:38 PM.

10. “Mortality rate, neonatal (per 1,000 live births) - sub-Saharan Africa.” Estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, UN DESA Population Division) at childmortality.org. The World Bank, IBRD-IDA (2023). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.NMRT?locations=ZG.

11. WHO. Palliative Care. [Health Topics]. World Health Organization (2020). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/palliative-care

12. World Health Organization. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into paediatrics: A WHO guide for health-care planners, implementers and managers. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018). 87. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274561 (Accessed May 2, 2023).

13. Jebessa S, Litch JA, Senturia K, Hailu T, Kahsay A, Kuti KA, et al. Qualitative assessment of the quality of care for preterm, low birth weight, and sick newborns in Ethiopia. Health Serv Insights. (2021) 14:117863292110251. doi: 10.1177/11786329211025150

14. Rent S, Bakari A, Deribessa S, Abayneh M, Shayo A, Bockarie Y, et al. Provider perceptions on bereavement following newborn death: a qualitative study from Ethiopia and Ghana. J Pediatr. (2023) 254:33–38.e3.doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.10.011

15. Connor S, Sisimayi C, Downing J, King E, Lim Ah Ken P, Yates R, et al. Assessment of the need for palliative care for children in South Africa. Int J Palliat Nurs. (2014) 20:130–4. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.3.130

16. LaVigne AW, Gaolebale B, Maifale-Mburu G, Grover S. Palliative care in Botswana: current state and challenges to further development. Ann Palliat Med. (2018) 7:449–54. doi: 10.21037/apm.2018.07.05

17. Lemmon ME, Bidegain M, Boss RD. Palliative care in neonatal neurology: robust support for infants, families and clinicians. J Perinatol. (2016) 36:331–7. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.188

18. Kenner C, Press J, Ryan D. Recommendations for palliative and bereavement care in the NICU: a family-centered integrative approach. J Perinatol. (2015) 35:S19–23. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.145

19. Marc-Aurele KL, Hull AD, Jones MC, Pretorius DH. A fetal diagnostic center’s referral rate for perinatal palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. (2018) 7:177–85. doi: 10.21037/apm.2017.03.12

20. Marc-Aurele KL, Nelesen R. A five-year review of referrals for perinatal palliative care. J Palliat Med. (2013) 16:1232–6. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0098

21. Kukora S, Gollehon N, Laventhal N. Antenatal palliative care consultation: implications for decision-making and perinatal outcomes in a single-centre experience. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2017) 102:F12–F16. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311027

22. Ellis A, Chebsey C, Storey C, Bradley S, Jackson S, Flenady V, et al. Systematic review to understand and improve care after stillbirth: a review of parents’ and healthcare professionals’ experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16:16. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0806-2

23. Wraight CL, Eickhoff JC, McAdams RM. Gaps in palliative care education among neonatology fellowship trainees. Palliat Med Rep. (2021) 2:212–7. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2021.0011

24. Wool C, Catlin A. Perinatal bereavement and palliative care offered throughout the healthcare system. Ann Palliat Med. (2019) 8:S22–9. doi: 10.21037/apm.2018.11.03

25. Carter BS, Bhatia J. Comfort/palliative care guidelines for neonatal practice: development and implementation in an academic medical center. J Perinatol. (2001) 21:279–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210582

26. Haward MF, Lantos J, Janvier A, For the POST Group. Helping parents Cope in the NICU. Pediatrics. (2020) 145:e20193567. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3567

27. Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, Danis M, White DB. Shared decision making in ICUs: an American college of critical care medicine and American thoracic society policy statement. Crit Care Med. (2016) 44:188–201. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001396

28. Weaver MS, October T, Feudtner C, Hinds PS. “Good-parent beliefs”: research, concept, and clinical practice. Pediatrics. (2020) 145:e20194018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4018

29. Parravicini E. Neonatal palliative care. Curr Opin Pediatr. (2017) 29:135–40. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000464

30. Levick J, Fannon J, Bodemann J, Munch S. NICU bereavement care and follow-up support for families and staff. Adv Neonatal Care. (2017) 17:451–60. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000435

31. Currie ER, Christian BJ, Hinds PS, Perna SJ, Robinson C, Day S, et al. Parent perspectives of neonatal intensive care at the end-of-life. J Pediatr Nurs. (2016) 31:478–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.03.023

32. Falck AJ, Moorthy S, Hussey-Gardner B. Perceptions of palliative care in the NICU. Adv Neonatal Care. (2016) 16:191–200. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000301

33. Baughcum AE, Fortney CA, Winning AM, Shultz EL, Keim MC, Humphrey LM, et al. Perspectives from bereaved parents on improving end of life care in the NICU. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol. (2017) 5:392–403. doi: 10.1037/cpp0000221

34. Clark OE, Fortney CA, Dunnells ZDO, Gerhardt CA, Baughcum AE. Parent perceptions of infant symptoms and suffering and associations with distress among bereaved parents in the NICU. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2021) 62:e20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.02.015

35. Sulmasy DP. “Reinventing” the rule of double effect. In: Steinbock B (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Bioethics (2009; online edn, Oxford Academic), Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press (2009). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199562411.003.0006

36. Hellmann J, Williams C, Ives-Baine L, Shah PS. Withdrawal of artificial nutrition and hydration in the neonatal intensive care unit: parental perspectives. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2013) 98:F21–5. doi: 10.1136/fetalneonatal-2012-301658

37. Committee on Bioethics; Guidelines on Forgoing Life-Sustaining Medical Treatment. Pediatrics. (1994) 93(3):532–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.93.3.532

38. Sieg SE, Bradshaw WT, Blake S. The best interests of infants and families during palliative care at the end of life: a review of the literature. Adv Neonatal Care. (2019) 19:E9–14. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000567

39. Wool C, Parravicini E. The neonatal comfort care program: origin and growth over 10 years. Front Pediatr. (2020) 8:588432. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.588432

40. Baughcum AE, Fortney CA, Winning AM, Dunnells ZDO, Humphrey LM, Gerhardt CA. Healthcare satisfaction and unmet needs among bereaved parents in the NICU. Adv Neonatal Care. (2020) 20:118–26. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000677

41. Hall SL, Ryan DJ, Beatty J, Grubbs L. Recommendations for peer-to-peer support for NICU parents. J Perinatol. (2015) 35(Suppl 1):S9–13. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.143

42. Cortezzo DE, Sanders MR, Brownell EA, Moss K. End-of-life care in the neonatal intensive care unit: experiences of staff and parents. Am J Perinatol. (2015) 32:713–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1395475

43. Sasaki H, Bouesseau M-C, Marston J, Mori R. A scoping review of palliative care for children in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Palliat Care. (2017) 16:60. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0242-8

44. Namisango E, Bhakta N, Wolfe J, McNeil MJ, Powell RA, Kibudde S, et al. Status of palliative oncology care for children and young people in sub-Saharan Africa: a perspective paper on priorities for new frontiers. JCO Glob Oncol. (2021) 7:1395–405. doi: 10.1200/GO.21.00102

45. Amery JM, Rose CJ, Holmes J, Nguyen J, Byarugaba C. The beginnings of children’s palliative care in Africa: evaluation of a children’s palliative care service in Africa. J Palliat Med. (2009) 12:1015–21. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0125

46. Arach AAO, Kiguli J, Nankabirwa V, Nakasujja N, Mukunya D, Musaba MW, et al. “Your heart keeps bleeding”: lived experiences of parents with a perinatal death in Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2022) 22:491. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04788-8

47. Ayebare E, Lavender T, Mweteise J, Nabisere A, Nendela A, Mukhwana R, et al. The impact of cultural beliefs and practices on parents’ experiences of bereavement following stillbirth: a qualitative study in Uganda and Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21:443. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03912-4

48. Mills TA, Ayebare E, Mukhwana R, Mweteise J, Nabisere A, Nendela A, et al. Parents’ experiences of care and support after stillbirth in rural and urban maternity facilities: a qualitative study in Kenya and Uganda. BJOG. (2021) 128:101–9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16413

49. Arach AAO, Nakasujja N, Rujumba J, Mukunya D, Odongkara B, Musaba MW, et al. Cultural beliefs and practices on perinatal death: a qualitative study among the Lango community in Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2023) 23:222. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05550-4

50. Dombrecht L, Chambaere K, Beernaert K, Roets E, De Vilder De Keyser M, De Smet G, et al. Components of perinatal palliative care: an integrative review. Children. (2023) 10:482. doi: 10.3390/children10030482

51. Meyer AC, Opoku C, Gold KJ. “They say I should not think about it:”: a qualitative study exploring the experience of infant loss for bereaved mothers in Kumasi, Ghana. Omega. (2018) 77:267–79. doi: 10.1177/0030222816629165

52. Ganca LL, Gwyther L, Harding R, Meiring M. What are the communication skills and needs of doctors when communicating a poor prognosis to patients and their families? A qualitative study from South Africa. S Afr Med J. (2016) 106:940–4. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i9.10568

53. Lewis EG, Oates LL, Rogathi J, Duinmaijer A, Shayo A, Megiroo S, et al. “We never speak about death.” healthcare professionals’ views on palliative care for inpatients in Tanzania: a qualitative study. Palliat Support Care. (2018) 16:566–79. doi: 10.1017/S1478951517000748

54. Yimer YS, Mohammed SA, Hailu AD. Patient-pharmacist interaction in Ethiopia: systematic review of barriers to communication. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2020) 14:1295–305. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S258914

55. Rent S, Bakari A, Plange-Rhule G, Bockarie Y, Kukora S, Moyer CA. Provider perspectives on Asram in Ghana. J Biosoc Sci. (2023) 54(3):437–49. doi: 10.1017/S0021932021000158

56. Rent S, Kukora SK. More similar than different: discoveries in medical culture when practicing global health at pediatric hospital in Ethiopia. Pediatric Ethicscope. (2021) 33. https://pediatricethicscope.org/article/more-similar-than-different-discoveries-in-medical-culture-when-practicing-global-health-at-pediatric-hospital-in-ethiopia-2/

57. Abawollo HS, Argaw MD, Tsegaye ZT, Beshir IA, Guteta AA, Heyi AF, et al. Institutionalization of limited obstetric ultrasound leading to increased antenatal, skilled delivery, and postnatal service utilization in three regions of Ethiopia: a pre-post study. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0281626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0281626

58. Simwaka ANK, de Kok B, Chilemba W. Women’s perceptions of nurse-midwives’ caring behaviours during perinatal loss in Lilongwe, Malawi: an exploratory study. Malawi Med J. (2014) 26:8–11. PMID: 24959318.24959318

59. Koopmans L, Wilson T, Cacciatore J, Flenady V. Support for mothers, fathers and families after perinatal death. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000452.pub3

60. Thornton R, Nicholson P, Harms L. Being a parent: findings from a grounded theory of memory-making in neonatal end-of-life care. J Pediatr Nurs. (2021) 61:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.03.013

61. Thornton R, Nicholson P, Harms L. Scoping review of memory making in bereavement care for parents after the death of a newborn. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. (2019) 48:351–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2019.02.001

62. Salgado HdO, Andreucci CB, Gomes ACR, Souza JP. The perinatal bereavement project: development and evaluation of supportive guidelines for families experiencing stillbirth and neonatal death in southeast Brazil—a quasi-experimental before-and-after study. Reprod Health. (2021) 18:5. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-01040-4

63. Uren TH, Wastell CA. Attachment and meaning-making in perinatal bereavement. Death Stud. (2002) 26:279–308. doi: 10.1080/074811802753594682

64. Davis G, Wortman CB, Darri C. Searching for meaning in loss: are clinical assumptions correct? Death Stud. (2000) 24:497–540. doi: 10.1080/07481180050121471

65. Gold KJ, Dalton VK, Schwenk TL. Hospital care for parents after perinatal death. Obstet Gynecol. (2007) 109:1156–66. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000259317.55726.df

66. Gravensteen IK, Helgadóttir LB, Jacobsen E-M, Rådestad I, Sandset PM, Ekeberg Ø. Women’s experiences in relation to stillbirth and risk factors for long-term post-traumatic stress symptoms: a retrospective study. BMJ Open. (2013) 3:e003323. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003323

67. Kuti O, Ilesanmi CE. Experiences and needs of Nigerian women after stillbirth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2011) 113:205–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.025

68. Sisay MM, Yirgu R, Gobezayehu AG, Sibley LM. A qualitative study of attitudes and values surrounding stillbirth and neonatal mortality among grandmothers, mothers, and unmarried girls in rural amhara and oromiya regions, Ethiopia: unheard souls in the backyard. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2014) 59:S110–7. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12156

69. Garten L, Von Der Hude K. Palliative care in the delivery room: challenges and recommendations. Children. (2022) 10:15. doi: 10.3390/children10010015

70. Garten L, Bührer C. Pain and distress management in palliative neonatal care. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. (2019) 24:101008. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2019.04.008

71. Jewkes R, Wood K. Competing discourses of vital registration and personhood: perspectives from rural South Africa. Soc Sci Med. (1998) 46:1043–56. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)10036-3

72. Shaw A. Rituals of infant death: defining life and Islamic personhood. Bioethics. (2014) 28:84–95. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12047

73. Kwesiga D, Tawiah C, Imam MA, Tesega AK, Nareeba T, Enuameh YAK, et al. Barriers and enablers to reporting pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes in population-based surveys: EN-INDEPTH study. Popul Health Metrics. (2021) 19:15. doi: 10.1186/s12963-020-00228-x

74. Due C, Chiarolli S, Riggs DW. The impact of pregnancy loss on men’s health and wellbeing: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2017) 17:380. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1560-9

75. Jones K, Robb M, Murphy S, Davies A. New understandings of fathers’ experiences of grief and loss following stillbirth and neonatal death: a scoping review. Midwifery. (2019) 79:102531. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2019.102531

76. Cacciatore J, DeFrain J, Jones KLC, Jones H. Stillbirth and the couple: a gender-based exploration. J Fam Soc Work. (2008) 11:351–72. doi: 10.1080/10522150802451667

77. Onyeka T. Palliative care in Enugu, Nigeria: challenges to a new practice. Indian J Palliat Care. (2011) 17:131. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.84534

78. Miklavcic JJ, Flaman P. Personhood status of the human Zygote, Embryo, Fetus. Linacre Q. (2017) 84:130–44. doi: 10.1080/00243639.2017.1299896

79. Ventura-Juncá P, Santos MJ. The beginning of life of a new human being from the scientific biological perspective and its bioethical implications. Biol Res. (2011) 44:201–7. /S0716-97602011000200013

80. Baker LR. When does a person begin? Soc Philos Policy. (2005) 22:25–48. doi: 10.1017/S0265052505052027

81. Sigurdson K, Mitchell B, Liu J, Morton C, Gould JB, Lee HC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal intensive care: a systematic review. Pediatrics. (2019) 144:e20183114. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3114

82. Wilkinson D, Nair T. Harm is n’t all you need: parental discretion and medical decisions for a child. J Med Ethics. (2016) 42:116–8. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2015-103265

83. Mercurio MR, Cummings CL. Critical decision-making in neonatology and pediatrics: the I-P-O framework. J Perinatol. (2021) 41:173–8. doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-00841-6

84. Kukora SK, Boss RD. Values-based shared decision-making in the antenatal period. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. (2018) 23(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2017.09.003

85. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller A-B, Narwal R, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. (2012) 379:2162–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4

86. Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, Das A, Hintz SR, Stoll BJ, et al. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372:1801–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410689

87. Bonet M, Cuttini M, Piedvache A, Boyle E, Jarreau P, Kollée L, et al. Changes in management policies for extremely preterm births and neonatal outcomes from 2003 to 2012: two population-based studies in ten European regions. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy. (2017) 124:1595–604. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14639

88. Janvier A, Baardsnes J, Hebert M, Newell S, Marlow N. Variation of practice and poor outcomes for extremely low gestation births: ordained before birth? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2017) 102:F470–1. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313332

89. Janvier A, Barrington K, Deschênes M, Couture E, Nadeau S, Lantos J. Relationship between site of training and residents’ attitudes about neonatal resuscitation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2008) 162:532–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.6.532

90. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Bell EF. Noninitiation or withdrawal of intensive care for high-risk newborns. Pediatrics. (2007) 119:401–3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3180

91. Cummings J, Committee On Fetus And Newborn. Antenatal counseling regarding resuscitation and intensive care before 25 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. (2015) 136:588–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2336

92. Madar J, Roehr CC, Ainsworth S, Ersdal H, Morley C, Rüdiger M, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: newborn resuscitation and support of transition of infants at birth. Resuscitation. (2021) 161:291–326. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.014

93. Butterfield LJ. Historical perspectives of neonatal transport. Pediatr Clin North Am. (1993) 40:221–39. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3955(16)38507-8

94. Audu LI, Otuneye A, Mairami AB, Mukhtar-Yola M, Mshelia LJ, Ekhaguere OA. Gestational age-related neonatal survival at a tertiary health institution in Nigeria: the age of fetal viability dilemma. Nig J Paed. (2020) 47:61–7. doi: 10.4314/njp.v47i2.2

95. Rent S, Bakari A, Aynalem Haimanot S, Deribessa SJ, Plange-Rhule G, Bockarie Y, et al. Perspectives on resuscitation decisions at the margin of viability among specialist newborn care providers in Ghana and Ethiopia: a qualitative analysis. BMC Pediatr. (2022) 22:97. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03146-z

96. Ubuane P, Ogunleye A, Solarin A, Diaku-Akinwumi I, Animasahun B, Knackstedt A. Clinical ethical dilemmas and conflicts encountered by paediatricians in Nigeria: a pilot online survey. Ann Cli Sci. (2022) 7:40–3.

97. Okolo A, Okonkwo I, Ideh R. Challenges and opportunities for neonatal respiratory support in Nigeria: a case for regionalisation of care. Nig J Paed. (2016) 43:64. doi: 10.4314/njp.v43i2.1

98. Maputo Protocol Ratification Map. Centre for human rights, university of Pretoria. Available at: https://www.maputoprotocol.up.ac.za/countries/interactive-map (Accessed June 9, 2023).

99. Protocol to the African charter on human and people’s rights on the rights of women in Africa (Maputo Protocol Text). African Union (2003). Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Women/WG/ProtocolontheRightsofWomen.pdf.

100. WHO African Region’s Countries Abortion Health Profiles. World health organization: African region (2021). Available at: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/who-african-regions-countries-abortion-health-profiles.

101. Teffo ME, Rispel LC. “I am all alone”: factors influencing the provision of termination of pregnancy services in two South African provinces. Glob Health Action. (2017) 10:1347369. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1347369

102. Otsin MNA, Taft AJ, Hooker L, Black K. Three delays model applied to prevention of unsafe abortion in Ghana: a qualitative study. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. (2022) 48:e75–80. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200903

103. Bercu C, Jacobson LE, Gebrehanna E, Ramirez AM, Katz AJ, Filippa S, et al. “I was afraid they will be judging me and even deny me the service”: experiences of denial and dissuasion during abortion care in Ethiopia. Front Glob Womens Health. (2022) 3:984386. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2022.984386

104. Makleff S, Wilkins R, Wachsmann H, Gupta D, Wachira M, Bunde W, et al. Exploring stigma and social norms in women’s abortion experiences and their expectations of care. Sex Reprod Health Matters. (2019) 27:1661753. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1661753

105. Mavuso JM-JJ, Macleod CI. Resisting abortion stigma in situ: South African womxn’s and healthcare providers’ accounts of the pre-abortion counselling healthcare encounter. Cult Health Sex. (2020) 22:1299–313. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2019.1674922

106. Ouedraogo R, Kimemia G, Igonya EK, Athero S, Wanjiru S, Bangha M, et al. “They talked to me rudely”. Women perspectives on quality of post-abortion care in public health facilities in Kenya. Reprod Health. (2023) 20:35. doi: 10.1186/s12978-023-01580-5

107. Yegon EK, Kabanya PM, Echoka E, Osur J. Understanding abortion-related stigma and incidence of unsafe abortion: experiences from community members in Machakos and trans Nzoia counties Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. (2016) 24:258. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.258.7567

108. Zia Y, Mugo N, Ngure K, Odoyo J, Casmir E, Ayiera E, et al. Psychosocial experiences of adolescent girls and young women subsequent to an abortion in sub-Saharan Africa and globally: a systematic review. Front Reprod Health. (2021) 3:638013. doi: 10.3389/frph.2021.638013

109. Blystad A, Haukanes H, Tadele G, Moland KM. Reproductive health and the politics of abortion. Int J Equity Health. (2020) 19:39. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-1157-1

110. Mavuso JM-JJ, Macleod CI. Contradictions in women’s experiences of pre-abortion counselling in South Africa: implications for client-centred practice. Nurs Inq. (2020) 27:e12330. doi: 10.1111/nin.12330

111. O’Connell KA, Kebede AT, Menna BM, Woldetensay MT, Fischer SE, Samandari G, et al. Signs of a turning tide in social norms and attitudes toward abortion in Ethiopia: findings from a qualitative study in four regions. Reprod Health. (2022) 19:198. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01240-6

112. Ewnetu DB, Thorsen VC, Solbakk JH, Magelssen M. Still a moral dilemma: how Ethiopian professionals providing abortion come to terms with conflicting norms and demands. BMC Med Ethics. (2020) 21:16. doi: 10.1186/s12910-020-0458-7

113. Ewnetu DB, Thorsen VC, Solbakk JH, Magelssen M. Navigating abortion law dilemmas: experiences and attitudes among Ethiopian health care professionals. BMC Med Ethics. (2021) 22:166. doi: 10.1186/s12910-021-00735-y

114. Magelssen M, Ewnetu DB. Professionals’ experience with conscientious objection to abortion in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: an interview study. Dev World Bioeth. (2021) 21:68–73. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12297

115. Oppong-Darko P, Amponsa-Achiano K, Darj E. “I am ready and willing to provide the service … though my religion frowns on abortion”-Ghanaian midwives’ mixed attitudes to abortion services: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:1501. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121501

116. Katz AJ, Ramirez AM, Bercu C, Filippa S, Dirisu O, Egwuatu I, et al. “I just have to hope that this abortion should go well”: perceptions, fears, and experiences of abortion clients in Nigeria. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0263072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263072

117. Jayaweera RT, Ngui FM, Hall KS, Gerdts C. Women’s experiences with unplanned pregnancy and abortion in Kenya: a qualitative study. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0191412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191412

118. Kebede MT, Hilden PK, Middelthon A-L. The tale of the hearts: deciding on abortion in Ethiopia. Cult Health Sex. (2012) 14:393–405. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.649495

119. Oduro GY, Otsin MNA. “Abortion–it is my own body”: women’s narratives about influences on their abortion decisions in Ghana. Health Care Women Int. (2014) 35:918–36. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.914941

120. Rehnström Loi U, Lindgren M, Faxelid E, Oguttu M, Klingberg-Allvin M. Decision-making preceding induced abortion: a qualitative study of women’s experiences in Kisumu, Kenya. Reprod Health. (2018) 15:166. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0612-6

121. Scott CJ, Futter M, Wonkam A. Prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy: perspectives of South African parents of children with down syndrome. J Community Genet. (2013) 4:87–97. doi: 10.1007/s12687-012-0122-0

122. Sanders MR, Hall SL. Trauma-informed care in the newborn intensive care unit: promoting safety, security and connectedness. J Perinatol. (2018) 38:3–10. doi: 10.1038/jp.2017.124

123. Marcelin JR, Siraj DS, Victor R, Kotadia S, Maldonado YA. The impact of unconscious bias in healthcare: how to recognize and mitigate it. J Infect Dis. (2019) 220:S62–73. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz214

Keywords: perinatal palliative care, sub-saharan Africa, neonatal intensive care, newborn bereavement, neonatal end-of-life care, low-middle-income-countries

Citation: Abayneh M, Rent S, Ubuane PO, Carter BS, Deribessa SJ, Kassa BB, Tekleab AM and Kukora SK (2023) Perinatal palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa: recommendations for practice, future research, and guideline development. Front. Pediatr. 11:1217209. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1217209

Received: 5 May 2023; Accepted: 13 June 2023;

Published: 26 June 2023.

Edited by:

Steven Leuthner, Medical College of Wisconsin, United StatesReviewed by:

Elvira Parravicini, Columbia University, United StatesHercília Guimarães, University of Porto, Portugal

Victoria J. Kain, Griffith University, Australia

Barthélémy Tosello, Aix-Marseille Université, France

© 2023 Abayneh, Rent, Ubuane, Carter, Deribessa, Kassa, Mekonnen Tekleab and Kukora. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stephanie K. Kukora c2trdWtvcmFAY21oLmVkdQ==

Abbreviations LMICs, low-and-middle-income countries; HICs, high-income countries; NMR, neonatal mortality rate; PC, palliative care; EOL, end of life; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; WHO, world health organization; LSMT, life-sustaining medical technology.

Mahlet Abayneh1

Mahlet Abayneh1 Sharla Rent

Sharla Rent Peter Odion Ubuane

Peter Odion Ubuane Brian S. Carter

Brian S. Carter Atnafu Mekonnen Tekleab

Atnafu Mekonnen Tekleab Stephanie K. Kukora

Stephanie K. Kukora