- 1School of Stomatology, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Affiliated Foshan Maternity & Child Healthcare Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 3Department of Medical Genetics, Experimental Education, Administration Center, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 4Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Single Cell Technology and Application, Guangzhou, China

- 5Department of Fetal Medicine and Prenatal Diagnosis, Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

Background: FERM domain-containing protein 4A (FRMD4A) is a scaffolding protein previously proposed to be critical in the regulation of cell polarity in neurons and implicated in human intellectual development.

Case Presentation: We report a case of a 3-year-old boy with corpus callosum anomaly, relative macrocephaly, ataxia, and unexplained global developmental delay. Here, compound heterozygous missense mutations in the FRMD4A gene [c.1830G>A, p.(Met610Ile) and c.2973G>C, p.(Gln991His)] were identified in the proband, and subsequent familial segregation showed that each parent had transmitted a mutation.

Conclusions: Our results have confirmed the associations of mutations in the FRMD4A gene with intellectual development and indicated that for patients with unexplained global developmental delay, the FRMD4A gene should be included in the analysis of whole exome sequencing data, which can contribute to the identification of more patients affected by this severe phenotypic spectrum.

Introduction

Global developmental delay (GDD) and intellectual disability (ID), which constitutes 3% of the pediatric population (1, 2), influences the physical and mental health of patients and their lives, bringing about heavy burdens for families and societies. Because the etiological diagnoses of GDD and ID overlap, the investigations leading up to a definitive diagnosis for these two diseases are naturally similar. Early detection and diagnosis are very important to the initiation of rehabilitative treatment as soon as possible. Genetic defects are responsible for the development of intellectual impairment in ~25% of patients, resulting in structural and/or functional defects of the central nervous system (3).

A previous study has described a family with a homozygous mutation in the FRMD4A gene, which resulted in a syndrome of congenital microcephaly, intellectual disability, and dysmorphism (4). In addition, FRMD4A polymorphisms have been suggested to be a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (5). We now report a novel compound heterozygous mutation in the FRMD4A gene in a child who has a GDD, ID, and corpus callosum anomaly.

Case Presentation

Clinical Examination

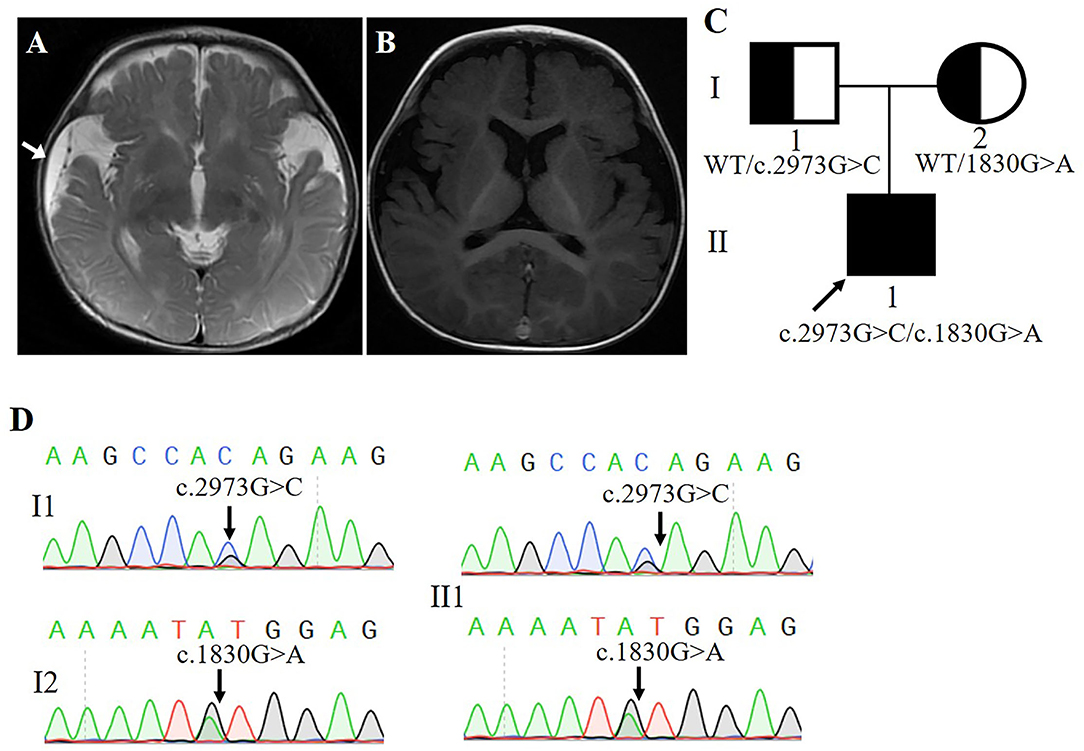

Our subject was a 3-year-old boy born at 36 weeks' gestation and the first child of healthy non-consanguineous Chinese parents. His birth weight was 3,600 g. At 6 months of age, his head circumference was 48.3 cm (+0.3 SD). At 11 months of age, his head circumference was 51 cm (+0.35 SD). The clinical examination results showed that the patient often had straightening of bilateral lower limbs, lasting for several seconds, and the frequency was uncertain, which was suggestive of non-epileptic seizure, with low muscular tension in his limbs. Skull magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of diffusion-weighted images (DWI) of the genu of corpus callosum and the splenium of corpus callosum presented abnormal high-signal shadow, slightly decreased cerebral white matter, and right frontal-temporal-parietal subdural effusion (Figure 1A). MRI re-examination disclosed a widened extracerebral space of bilateral temporal and parietal lobes (Figure 1B). The history and clinical examination findings were suggestive of either a genetic or a brain development abnormality.

Figure 1. (A,B) Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient's head (Arrow points to area of subdural effusion). (C) Poband (II-1) is shown. The squares represent the proband, and his father. The circle represents the mother. (D) Sanger sequencing showing two alleles of the proband and his parents, respectively.

Molecular Investigation

Blood samples were collected and sent for genetic testing and molecular studies after obtaining informed written consent from the parents. The pedigree was drawn after obtaining detailed family information (Figure 1C).

Whole-exome sequencing results showed that two previously unreported missense mutations in the FRMD4A gene (NM_018027), namely, c.1830G>A, p.(Met610Ile) in exon 20, and c. 2973G>C, p.(Gln991His) in exon 23 were found to be the cause of brain development abnormality in the proband of the family (Table 1). Sanger sequencing showed that the patient inherited the p.(Gln991His) mutation from his father and the p.(Met610Ile) mutation from his mother, consistent with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance (Figure 1D). These mutations were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing analysis. The primers used for this test were as follows: forward 1, 5′-CTTGTCTTGGCAACTGGGGA-3′ and reverse 1, 5′-GCGCTGCCTGAGATTTCCTA-3′; and forward 2, 5′-GCCACACTGAAAATGCCCTG and reverse 2, 5′-ACAGCAGATCATGGGGCTTC-3′.

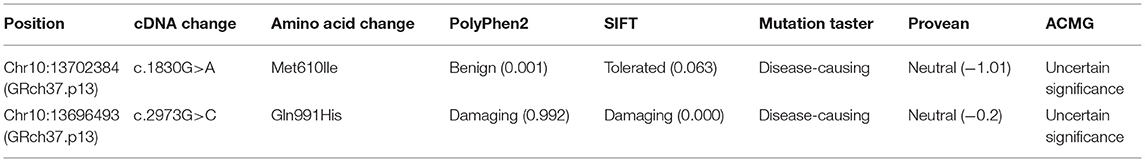

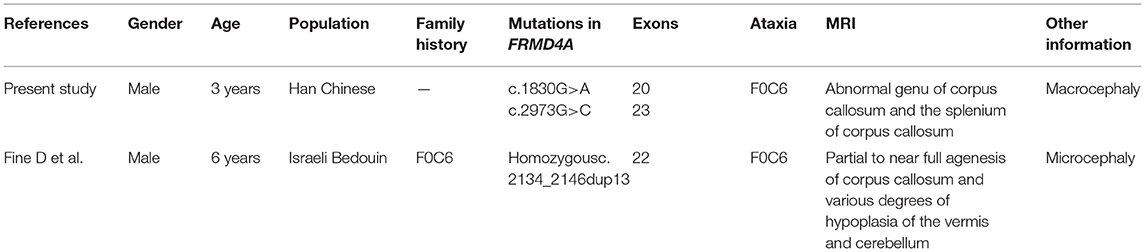

The p.(Met610Ile) mutation of the FRMD4A gene was predicted to be probably benign according to PolyPhen-2, SIFT, and Provean (Table 1), and this mutation was novel as it had not been previously reported and it was not present in dbSNP, HGMD, or Exome Variant Server. The p.(Gln991His) mutation of the FRMD4A gene was predicted to affect the features of the protein and to be disease-causing according to PolyPhen-2, SIFT, and Mutation Taster (Table 1). We also compared the clinical characteristics caused by mutations at different sites of he FRMD4A (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of the clinical features of the present study and published case associated with FRMD4A mutation.

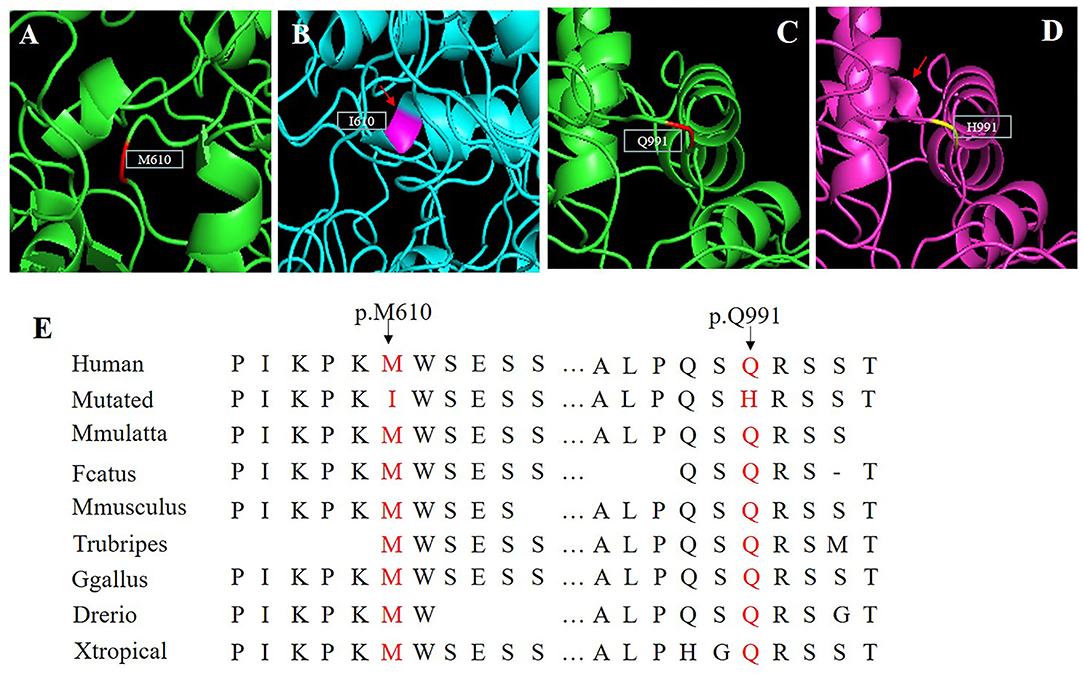

A 3D model was constructed for the structural analysis of WT/MUT FRMD4A proteins to determine the pathogenicity of mutant FRMD4A according to I-TASSER. When amino acid 610 was changed to isoleucine, the side chains of FRMD4A also changed, and they tended to be longer than those of a structure in which amino acid 610 was methionine (Figures 2A,B). The mutated H911 protein had a different side chain than the wild-type protein as a result of an amide glutamine being substituted for a basic amino acid histidine (Figures 2C,D). Both p.(Met610Ile) and p.(Gln991His) mutations of the FRMD4A gene consisted of highly conserved amino acid residues among different species (Figure 2E), indicating their structural and functional importance. Therefore, the compound heterozygous mutations were predicted to affect the amino acid side chain. This might have disrupted FRMD4A function as well as interactions with other molecules and residues.

Figure 2. (A–D) Protein molecular models of wild type (upper) and FRMD4A mutations (lower) by I-TASSER. (E) Conservation analysis of the abnormal variation. Results indicate that both Met610 and Gln991 in the FRMD4A protein are highly conserved between different species.

Discussion and Conclusion

We described a young boy with a syndrome of global developmental delay, intellectual disability, relative macrocephaly, and non-epileptic seizure. In fact, many studies on global developmental delay and intellectual disability are usually accompanied by macrocephaly (6–8). However, no other mutations assumed to be consistent with the autosomal recessive inheritance pattern of the family were identified by whole-exome sequencing, except a new compound heterozygous mutation of the FRMD4A gene. Remarkably, by contrast, previously described patients with the FRMD4A mutation presented microcephaly (4), not macrocephaly. This different clinical feature represents a possible novel phenotypic trait involving the FRMD4A mutation. Although the phenotype characteristic of head circumference was inconstant, we conclude that the association of epilepsy, intellectual disability/global developmental delay and ataxia is a recurrent clinical pattern in cases with FRMD4A mutations. To our knowledge, our patient is only the second case of the syndrome caused by the FRMD4A mutation in the literature (4), and the first case reported compound heterozygosity.

The FRMD4A protein, a member of the FERM superfamily, is localized in the cytoplasm and the cytoskeleton, where it binds molecules in the undercoat of the cell-to-cell adherens junction (9). The protein encoded by the FRMD4A gene is involved in cell structure, transport, and signal transduction, and it plays a role in the regulation of cell polarity in epithelial cells and neurons (10, 11). In addition, FRMD4A is expressed in many tissues, with higher levels in the brain (12, 13). More importantly, the relationship between the FRMD4A protein and the brain is not only reflected in the syndrome of microcephaly and intellectual disability caused by its mutation (4), but also in the phenotypes that are observed in carriers of its genomic copy number mutations that increase the risk of schizophrenia (14). Interestingly, other studies have reported that FRMD4A mutations are regarded as a genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease in that they can disrupt tau secretion by activating cytohesin–Arf6 signaling (5, 11).

In epithelial cells, FRMD4A was demonstrated to act as a scaffolding protein, regulating cell polarity by connecting the Par3–Par6–aPKCζ complex to Arf6 signaling through cytohesin-1 (10). Par polarity complex signaling plays an important role in neuronal polarization (15) but also in membrane trafficking, including vesicular secretion (16). The fact that FRMD4A binds to both Par3 and the ARF6 guanine nucleotide exchange factor (cytohesin-1) suggests that FRMD4A mediates their interaction and that the Par3–FRMD4A–cytohesin-1 complex ensures accurate activation of the ARF6 protein (17). On the other hand, in HEK293t cells, FRMD4A, a genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease, modulates cellular release of tau through cytohesins and Arf6 (11).

In summary, a compound heterozygote in the FRMD4A gene was identified in a 3-year-old male patient with a severe neurological phenotype of unique dysmorphism, and a novel missense mutation was suspected. The results were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The source of mutations was investigated by two-generation pedigree analysis. The current results broaden the spectrum of FRMD4A mutations responsible for the neurological phenotype, and they have important implications for molecular diagnosis, treatment, and genetic counseling in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Foshan Maternity & Child Healthcare Hospital to Southern Medical University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

XY, XG, XZ, YL, JL, TY, and XH contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the clinical data. YP, FH, JZ, BW, and FX designed and performed the molecular analysis of the patient and patient's parents. All the authors contributed with the draft of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171713, 31970558 and 81870755), Foshan Science and Technology Bureau (2020001003953), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2020A1515010308), and Project of Foshan Genetic Disease Precision Diagnosis Engineering Technology Research Center (2020001003953).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their family members for consenting to this research.

References

1. Belanger SA, Caron J. Evaluation of the child with global developmental delay and intellectual disability. Paed Child Healt Can. (2018) 23:403–10. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxy093

2. Moeschler JB, Shevell M. Comprehensive evaluation of the child with intellectual disability or global developmental delays. Pediatrics. (2014) 134:E903–18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1839

3. Johnson CP, Walker WO Jr, Palomo-González SA, Curry CJ. Mental retardation: diagnosis, management, and family support. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2006) 36:126–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.02.004

4. Fine D, Flusser H, Markus B, Shorer Z, Gradstein L, Khateeb S, et al. A syndrome of congenital microcephaly, intellectual disability and dysmorphism with a homozygous mutation in FRMD4A. Eur J Hum Genet. (2015) 23:1729–34. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.241

5. Lambert JC, Grenier-Boley B, Harold D, Zelenika D, Chouraki V, Kamatani Y, et al. Genome-wide haplotype association study identifies the FRMD4A gene as a risk locus for Alzheimer's disease. Mol Psychiatr. (2013) 18:461–70. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.14

6. Assoum M, Bruel AL, Crenshaw ML, Delanne J, Wentzensen IM, McWalter K, et al. Novel KIAA1033/WASHC4 mutations in three patients with syndromic intellectual disability and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A. (2020) 182:792–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61487

7. Pajusalu S, Reimand T, Ounap K. Novel homozygous mutation in KPTN gene causing a familial intellectual disability-macrocephaly syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. (2015) 167:1913–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37105

8. Domingues FS, Konig E, Schwienbacher C, Volpato CB, Picard A, Cantaloni C, et al. Compound heterozygous SZT2 mutations in two siblings with early-onset epilepsy, intellectual disability and macrocephaly. Seizure Eur J Epilep. (2019) 66:81–5. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.12.021

9. Tepass U. FERM proteins in animal morphogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. (2009) 19:357–67. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.05.006

10. Ikenouchi J, Umeda M. FRMD4A regulates epithelial polarity by connecting Arf6 activation with the PAR complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:748–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908423107

11. Yan X, Nykanen NP, Brunello CA, Haapasalo A, Hiltunen M, Uronen RL, et al. FRMD4A-cytohesin signaling modulates the cellular release of tau. J Cell Sci. (2016) 129:2003–15. doi: 10.1242/jcs.180745

12. Zhu XW, Zhou B, Pattni R, Gleason K, Tan CF, Kalinowski A, et al. Machine learning reveals bilateral distribution of somatic L1 insertions in human neurons and glia. Nat Neurosci. (2021) 24:186–96. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00767-4

13. Shaheen R, Alkuraya FS, Maddirevula S, Ewida N, Alsahli S, Abdel-Salam GMH, et al. Genomic and phenotypic delineation of congenital microcephaly. Genet Med. (2019) 21:545–52. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0140-3

14. Rees E, Walters JTR, Georgieva L, Isles AR, Chambert KD, Richards AL, et al. Analysis of copy number variations at 15 schizophrenia-associated loci. Brit J Psychiat. (2014) 204:108–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131052

15. Insolera R, Chen S, Shi SH. Par proteins and neuronal polarity. Dev Neurobiol. (2011) 71:483–94. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20867

16. Balklava Z, Pant S, Fares H, Grant BD. Genome-wide analysis identifies a general requirement for polarity proteins in endocytic traffic. Nat Cell Biol. (2007) 9:1066–73. doi: 10.1038/ncb1627

Keywords: global developmental delay (GDD), compound heterozygous missense mutations, corpus callosum anomaly, FRMD4A, intellectual disability

Citation: Pan Y, Guo X, Zhou X, Liu Y, Lian J, Yang T, Huang X, He F, Zhang J, Wu B, Xiong F and Yang X (2021) Case Report: A Novel Compound Heterozygous Mutation of the FRMD4A Gene Identified in a Chinese Family With Global Developmental Delay, Intellectual Disability, and Ataxia. Front. Pediatr. 9:775488. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.775488

Received: 14 September 2021; Accepted: 20 October 2021;

Published: 17 November 2021.

Edited by:

Anna Maria Lavezzi, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Charles Marques Loureco, University of São Paulo Ribeirão Preto, BrazilAmjad Khan, Université de Strasbourg, France

Copyright © 2021 Pan, Guo, Zhou, Liu, Lian, Yang, Huang, He, Zhang, Wu, Xiong and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Buling Wu, YnVsaW5nd3VAc211LmVkdS5jbg==; Fu Xiong, eGlvbmdmdUBzbXUuZWR1LmNu; Xingkun Yang, ZnN5YW5neGtAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

Yuhua Pan

Yuhua Pan Xiaoling Guo

Xiaoling Guo Xiaoqiang Zhou

Xiaoqiang Zhou Yue Liu2

Yue Liu2 Tingting Yang

Tingting Yang Xiang Huang

Xiang Huang Fei He

Fei He Jian Zhang

Jian Zhang Fu Xiong

Fu Xiong Xingkun Yang

Xingkun Yang