- 1Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, Saga, Japan

- 2Clinical Research Center, Saga University Hospital, Saga, Japan

Background: Developmental disorders and high Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection rates have been reported. This study aimed to examine the prevalence of H. pylori in a special needs school where all students had developmental disorders in Japan.

Methods: In 2017, third-grade junior high school and second- and third-grade high school students attending a special needs school with developmental disorders were enrolled. Participants of Saga Prefecture's H. pylori test and treat project, which comprised third-grade junior high school students not from special needs school, were assigned to the control group.

Results: In the control group, H. pylori positive results were 3.18% (228/7,164) students. Similarly, in developmental disorder group, H. pylori positive results were 6.80% (13/191) students. For the developmental disorder and control groups, this present examination sensitivity was 7.03% (13/185), specificity was 96.76% (6,815/7,043), positive predictive value was 5.39% (13/241), negative predictive value was 97.54% (6,815/6,987), Likelihood ratio of a positive result 2.17 and Odds ratio was 2.26 (95% confidence interval: 1.27–4.03, p = 0.005).

Conclusion: The prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly higher in adolescents with developmental disorders than in typically developing adolescents.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infects the human gastric mucosa and causes gastritis and gastric cancer (1, 2). H. pylori infection also affects aspects of stomach function, such as gastric acid secretion, which causes changes in the stomach environment and intestinal microbiome (3, 4).

The global H. pylori incidence in children varies significantly, from 2.5% in Japan to 34.6% in Ethiopia (5), and it is greatly affected by economic power and living environment of the country (6). The primary modes of transmission are thought to be fecal-oral and oral-oral, but some indirect evidence has also been published for transmission via drinking water and other environmental sources (7). The patterns of spreading of H. pylori under conditions of high prevalence differ from those in developed countries (8).

Due to the suspicion of an association between H. pylori infection in early life and neurodevelopmental problems (9, 10), studies have been conducted overseas to determine the association between them, but there are no data for Japan (11). Therefore, the current study

aimed to examine the incidence of H. pylori infection in Japan in patients with developmental disorders in comparison with the control group and to discuss the association between H. pylori and developmental disorders.

Methods and Materials

Study Design and Subjects

Saga Prefecture is one of the local governments in Japan, and its population is about 830,000. There are 108 junior high schools (including eight special needs schools), with a total of ~8,500 students in the third grade. In the spring of 2016, we initiated a program for screening and treatment of H. pylori infection in all third-grade junior high school students, including special needs schools, in Saga Prefecture (approved by the institutional review board of Saga University Hospital [approval number: 2015-12-19]) (12). In 2017, third-grade junior high school students of special needs school with a developmental disorder, including intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and learning disabilities, were eligible for participation. Similarly, in addition to the Saga Prefecture project, second- and third-grade high school students of special needs school with a developmental disorder were also enrolled (developmental disorder group). The control group comprised third-grade junior high school students not from a special needs school in the Saga Prefecture project.

Testing for H. pylori

After obtaining written informed consent from each student and his or her guardian, urine samples were screened for the presence of anti–H. pylori immunoglobulin G antibody by immunochromatography (RAPIRAN® Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the urinary test have been reported to be 89 and 93%, respectively (13, 14). Students who screened positive on the urine antibody test also received an H. pylori stool antigen detection kit (Testmate Rapid Pylori Antigen® Wakamoto Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to check for the presence or absence of H. pylori infection (15). In the present study, students positive for both H. pylori urinary antibody and fecal H. pylori antigen tests were defined as H. pylori infection. Students negative for H. pylori urinary antibody test were defined as H. pylori non-infection.

Statistical Analysis

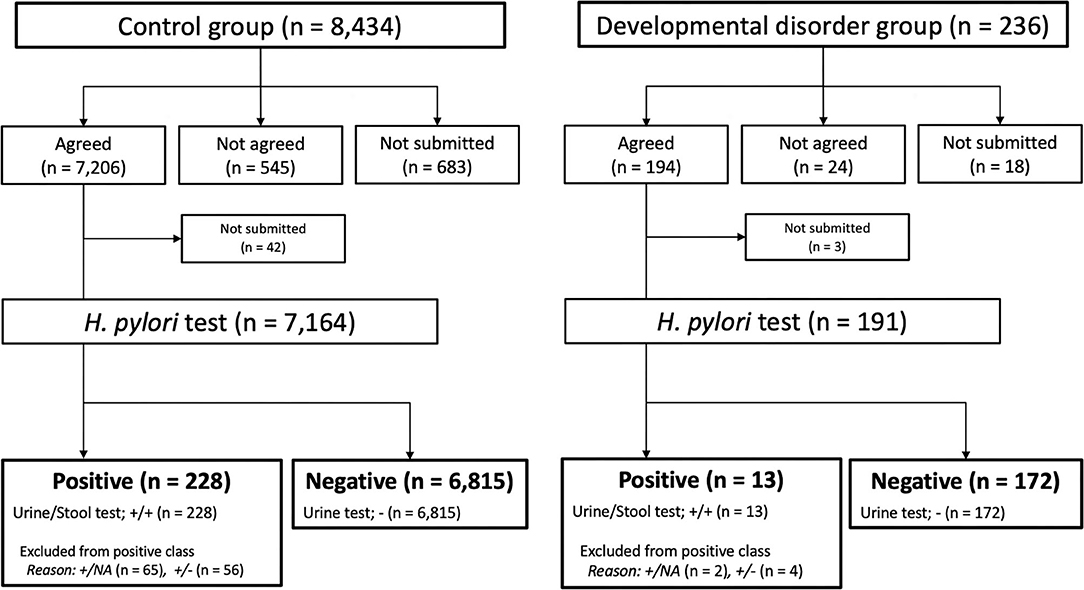

For the developmental disorder group and the control group, the comparative statistical analyses were conducted with contingency tables that summarized the results of the test classifiers examined. After the H. Pylori tests were examined, the patients were classified as follows: the positive was defined urine (+) and stool (+) test patients (=H. pylori infection patients), and the negative was defined urine (-) test patients (=H. pylori non-infection patients) (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Participant's flowchart and Helicobacter pylori test results. H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; NA, not available.

The parameters were estimated and shown as sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, the likelihood ratio of a positive result, and the odds ratio. And chi-square tests were applied. Statistical software JMP version 15.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used. All p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Student Characteristics

Figure 1 summarizes the flowchart for the participants in both the control group and the developmental disorders group. There was no sex bias between the two groups. Among the 8,434 students in the control group, 7,206 agreed to participate in the Saga Prefecture project, and 7,164 received urine H. pylori antibody tests. Among the 236 students in the developmental disorders group, 194 agreed to participate in both the Saga Prefecture project and our study, and 191 received urine H. pylori antibody tests.

Test for H. pylori Infection Rate

Figure 1 shows the results of the urine H. pylori antibody and fecal H. pylori antigen tests in both groups. In the control group, positive results were 3.18% (228/7,164) students, 121 students with fecal H. pylori antigen tests negative or not implemented were excluded from the positive results. Negative results were 95.13% (6,815/7,164) students. Similarly, in developmental disorder group, positive results were 6.80% (13/191) students, 6 students with fecal H. pylori antigen tests negative or not implemented were excluded from the positive results. Negative results accounted for 90.05% (172/191) of the students.

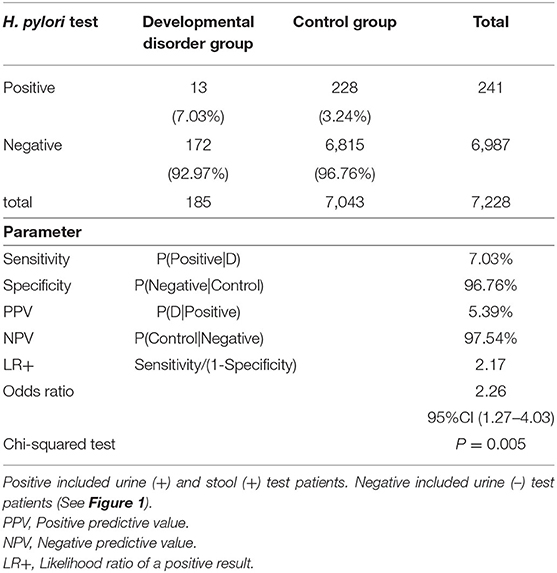

Table 1 shows test results for the H. pylori infection rate between both groups. For the developmental disorder and control groups, this present examination sensitivity was 7.03% (13/185), specificity was 96.76% (6,815/7,043), positive predictive value was 5.39% (13/241), negative predictive value was 97.54% (6,815/6,987), the likelihood ratio of a positive result 2.17 and Odds ratio was 2.26 (95% confidence interval: 1.27–4.03, p = 0.005). The developmental disorder group was approximately twice as likely to show positive results for H. pylori infection as the control group.

Table 1. Test for Helicobacter pylori infection rate between the control group and developmental disorders group.

Discussion

This study showed that the prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly higher in adolescents with developmental disorders than in typically developing adolescents in Japan.

Kitchens et al. reviewed the association between H. pylori and intellectual and developmental disabilities overseas (11). However, the papers they cited did not include Japanese data, and there was a possibility that various biases existed due to the large age range of the subjects. Our study is the first report that includes Japanese data. Because the age range was limited to adolescence, the number of subjects was large, and the subjects in both groups were living in the same area; thus, confounding factors seemed to be small in our study.

The reasons for the high incidence of H. pylori infection in adolescents with developmental disorders are unknown. Kitchens et al. reported that maladaptive behaviors exhibited by individuals who have intellectual disabilities and developmental disabilities can be considered as risk factors for H. pylori infection (11). Maladaptive behaviors exhibited by individuals who have developmental disorders can be considered as risk factors for H. pylori infection because H. pylori has been cultivated from vomitus, saliva, and feces (16).

Morad et al. concluded that residential living with shared living quarters and eating in the same utensils contributed to the risk factors for H. pylori infection in people with intellectual disabilities and developmental disabilities (17). Lambert et al. determined that the most important factor for H. pylori infection was the duration of institutionalization (18). In Japan, schools for children with disabilities often have dormitories that house students with developmental disorders. Group life may have an effect on increasing the infection rate of H. pylori, regardless of the presence of developmental disorders. Unfortunately, this study could not investigate whether they had lived in groups.

Karachallou et al. reported that H. pylori infection in early life may be an important risk factor for poor neurodevelopment (18). Several epidemiological studies reported that H. pylori-infected family members are the risk factor for pediatric infection with H. pylori (19, 20). Osaki et al. reported that mother-to-child transmission of H. pylori was demonstrated in 80% of patients while assessing the genomic profiles of H. pylori isolates from family members by multi-locus sequence typing (21).

Our study demonstrates higher rates of H. pylori infection among adolescents with developmental disorders. However, we should be cautious in discussing causative associations between developmental disorders and H. pylori infection. In Japan, the incidence of H. pylori infection declines with each generation (22), and this is true even among the young generation (12). On the other hand, developmental disorders have been increasing annually in Japan (23). These two facts are contradictory and may be grounds for denying the association between H. pylori infection and developmental disorders.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, the control group could have included students with developmental disorders, as we did not have any ways to check their medical or medication history in the control group. Second, background factors, such as life history, that could be risk factors for H. pylori infection could not be compared between the two groups. Similarly, we were not able to compare the number of family members the number of people living together in the institutions, and economic status between the two groups. Third, the criterion chosen for screening of H. pylori infection was a urinary antibody test (which is not a gold standard test). There is an established screening program for kidney diseases in Japan (including Saga Prefecture) targeting third-grade students in junior high schools. Given the full inclusivity of students during this test through simple urine examination, we used the established system to obtain urine samples to screen for H. pylori infection. Only students positive for H. pylori urinary antibody test underwent a secondary test, fecal H. pylori antigen test. There was a possibility that false negatives were included as some students defined as negative for H. pylori infection.

In conclusion, H. pylori infection rates were found to be significantly higher in adolescents with developmental disorders than in typically developing adolescents in Japanese. Future Basic and clinical studies are needed to elucidate the direct relationship between H. pylori infection and developmental disorders.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The ethical aspects of this study were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Saga University Hospital (approval number: 2016-12-03). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

TK and MM conceptualized, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript. TK collected the data. AT performed statistical analyses. MM critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

Funding

This study was supported by public grants from the Government of Saga Prefecture.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Kozue Kakiuchi, Ms. Tomomi Ito, and Ms. Hiromi Beppu for project support. We also thank Enago Co., Ltd (https://www.enago.jp) for proofreading this manuscript.

Abbreviations

H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori.

References

1. Suzuki H, Mori H. World trends for H. pylori eradication therapy and gastric cancer prevention strategy by H. pylori test-and-treat. J Gastroenterol. (2018) 53:354–61. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1407-1

2. Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. (2001) 345:784–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999

3. Llorca L, Perez-Perez G, Urruzuno P, Martinez MJ, Iizumi T, Gao Z, et al. Characterization of the gastric microbiota in a pediatric population according to Helicobacter pylori status. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2017) 36:173–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001383

4. Oh B, Kim BS, Kim JW, Kim JS, Koh SJ, Kim BG, et al. The effect of probiotics on gut microbiota during the helicobacter pylori eradication: randomized controlled trial. Helicobacter. (2016) 21:165–74. doi: 10.1111/hel.12270

5. Mišak Z, Hojsak I, Homan M. Review: Helicobacter pylori in pediatrics. Helicobacter. (2019) 24:e12639. doi: 10.1111/hel.12639

6. Zebala Torrres B, Luceno Y, Lagomarcino AJ, Orellance-Manzano A, George S, Torres JP, et al. Review: prevalence and dynamics of Helicobacter pylori infection during childhood. Helicobacter. (2017) 22:e12399. doi: 10.1111/hel.12399

7. Schwarz S, Morelli G, Kusecek B, Manica A, Balloux F, Owen RJ, et al. Horizontal versus familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Pathog. (2008) 4:e1000180. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000180

8. Yucel O. Prevention of Helicobacter pylori infection in childhood. World J Gastroenterol. (2014) 20:10348–54. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10348

9. Karachaliou M, Chatzi L, Michel A, Kyriklaki A, Kampouri M, Koutra K, et al. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and childhood neurodevelopment, the rhea birth cohort in Crete, Greece. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. (2017) 31:374–84. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12374

10. Lee A. Early influences and childhood development. Does helicobacter play a role? Helicobacter. (2007) 12(Suppl. 2):69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00567.x

11. Kitchens DH, Binkley CJ, Wallace DL, Darling D. Helicobacter pylori infection in people who are intellectually and developmentally disabled: a review. Spec Care Dentist. (2007) 27:127–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2007.tb00334.x

12. Kakiuchi T, Matsuo M, Endo H, Nakayama A, Sato K, Takamori A, et al. A Helicobacter pylori screening and treatment program to eliminate gastric cancer among junior high school students in Saga Prefecture: a preliminary report. J Gastroenterol. (2019) 54:699–707. doi: 10.1007/s00535-019-01559-9

13. Okuda M, Kamiya S, Journala M, Kikuchi S, Osaki T, Hiwatani T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of urine-based kits for detection of Helicobacter pylori antibody in children. Pediatr Int. (2013) 55:337–41. doi: 10.1111/ped.12057

14. Yamamoto T, Ishii T, Kawakami T, Sase Y, Horikawa C, Aoki N, et al. Reliability of urinary tests for antibody to Helicobacter pylori in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. World J Gastroenterol. (2005) 11:412–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.412

15. Shimoyama T. Stool antigen tests for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. (2013) 19:8188–91. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8188

16. Parsonnet J, Shmuely H, Haggerty T. Fecal and oral shedding of Helicobacter pylori from healthy infected adults. JAMA. (1999) 282:2240–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2240

17. Morad M, Merrick J, Nasri Y. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in people with intellectual disability in a residential care centre in Israel. J Intellect Disabil Res. (2002) 46:141–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2002.00382.x

18. Lambert JR, Lin SK, Sievert W, Nicholson L, Schembri M, Guest C. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori antibodies in an institutionalized population: evidence for person-to-person transmission. Am J Gastroenterol. (1995) 90:2167–71.

19. Goodman KJ, Correa P. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori among siblings. Lancet. (2000) 355:358–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05273-3

20. Vincent P, Gottrand F, Pernes P, Husson MO, Lecomte-Houcke M, Turck D, et al. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in cohabiting children. Epidemiology of a cluster, with special emphasis on molecular typing. Gut. (1994) 35:313–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.313

21. Osaki T, Konno M, Yonezawa H, Hojo F, Zaman C, Takahashi M, et al. Analysis of intra-familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese families. J Med Microbiol. (2015) 64:67–73. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.080507-0

22. Miyamoto R, Okuda M, Lin Y, Murotani K, Okumura A, Kikuchi S. Rapidly decreasing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori among Japanese children and adolescents. J Infect Chemother. (2019) 25:526–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.02.016

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, developmental disorders, adolescents, special needs schools, Japan

Citation: Kakiuchi T, Takamori A and Matsuo M (2021) High Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Special Needs Schools in Japan. Front. Pediatr. 9:697200. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.697200

Received: 19 April 2021; Accepted: 03 June 2021;

Published: 08 July 2021.

Edited by:

Ana Isabel Lopes, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Matjaž Homan, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, SloveniaDoina Anca Plesca, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania

Copyright © 2021 Kakiuchi, Takamori and Matsuo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Toshihiko Kakiuchi, a2FraXVjaHRAY2Muc2FnYS11LmFjLmpw

Toshihiko Kakiuchi

Toshihiko Kakiuchi Ayako Takamori

Ayako Takamori Muneaki Matsuo

Muneaki Matsuo