- 1Pediatric Clinic, Pietro Barilla Children's Hospital, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

- 2Unit of Emergency Pediatrics, Department of Human Pathology in Adult and Developmental Age “Gaetano Barresi,” University of Messina, Policlinico “G. Martino,” Messina, Italy

- 3Unit of Neuropsychiatry of Children and Adolescents, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale (AUSL) Parma, Parma, Italy

- 4Academic Department of Pediatrics (DPUO), Research Unit of Congenital and Perinatal Infections, Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital, Rome, Italy

- 5Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy

Background: Previous studies have shown that during COVID-19 pandemic, mainly due to the imposed lockdown, significant psychological problems had emerged in a significant part of the population, including older children and adolescents. School closure, leading to significant social isolation, was considered one of the most important reasons for pediatric mental health problems. However, how knowledge of COVID-19 related problems, modification of lifestyle and age, gender and severity of COVID-19 pandemic had influenced psychological problems of older children and adolescents has not been detailed. To evaluate these variables, a survey was carried out in Italy.

Methods: This cross-sectional survey was carried out by means of an anonymous online questionnaire administered to 2,996 students of secondary and high schools living in Italian Regions with different COVID-19 epidemiology.

Results: A total of 2,064 adolescent students (62.8% females; mean age, 15.4 ± 2.1 years), completed and returned the questionnaire. Most of enrolled students showed good knowledge of COVID-19-related problems. School closure was associated with significant modifications of lifestyle and the development of substantial psychological problems in all the study groups, including students living in Regions with lower COVID-19 incidence. However, in some cases, some differences, were evidenced. Sadness was significantly more frequent in females (84%) than males (68.2%; p < 0.001) and in the 14–19-year-old age group than the 11–13-year-old age group (79.2% vs. 70.2%; p < 0.001). Missing the school community was a significantly more common cause of sadness in girls (26.5% vs. 16.8%; p < 0.001), in southern Italy (26.45% vs. 20.2%; p < 0.01) and in the 14–19-year-old group (24.2% vs. 14.7%; p < 0.001). The multivariate regression analysis showed that male gender was a protective factor against negative feelings (p < 0.01), leading to a decrease of 0.63 points in the total negative feelings index. Having a family member or an acquaintance with COVID-19 increased the negative feelings index by 0.1 points (p < 0.05).

Conclusions: This study shows that school closures because of the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak was associated with significant lifestyle changes in all the students, regardless of age and gender. Despite some differences in some subgroups, the study confirms that school closure can cause relevant mental health problems in older children and adolescents. This must be considered as a reason for the maintenance of all school activities, although in full compliance with the measures to contain the spread of the pandemic.

Background

Several studies have shown that severe infectious disease outbreaks affecting multiple countries and communities can impact not only physical but also psychological health (1–3). Although positive changes and cognitive restructuring were described in some cases, generally, a series of negative consequences was evidenced. Development of anxiety, fear, somatic symptoms, sleep disturbance, depression, feelings of anger and irritability, grief and loss, post-traumatic stress, and stigmatization due to severe infection disease outbreaks have been repeatedly reported in a significant part of the population. A cross-sectional study carried out in Singapore 16 weeks after the first national outbreak of SARS showed that 22.9 and 25.8% of 415 individuals visiting community health care services had suffered or were suffering from SARS-related psychiatric or posttraumatic morbidities, respectively (4). Similar or even higher rates of acute and long-term psychosocial effects at the individual, community, and international levels were demonstrated during and after the 2009 influenza pandemic and Ebola epidemic (5, 6).

As expected, the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been accompanied by the development of significant psychological problems in a considerable part of the population; however, the incidence and type of psychological reactions have varied significantly according to the characteristics of the involved population and the incidence rate of the disease in the geographic area where the problem has been studied (7, 8). The most vulnerable groups seem to be health-care workers, homeless people, migrant workers, pregnant women, and people who were already mentally ill. Moreover, it has been suggested that other vulnerable populations, such as people leaving in remote or rural areas who face barriers in accessing health care and those living in lower socioeconomic conditions, may develop relevant psychological problems (9). The same seems true for older children and adolescents, who, mainly due to school closures, remain socially isolated and may lose access to all the health services that are delivered via schools, including mental health services (10).

Italy was deeply affected by the present COVID-19 pandemic, but there were differences in the effects between the northern and southern regions. On August 25, 2020, 261,174 laboratory-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) cases and 35,445 deaths were reported to the Ministry of Health in Italy, among which more than 70% were diagnosed in the northern regions (11). Since March 8, school closures until the end of the school year have been recommended in Italy, and lessons have been performed via tele-teaching (11). The impact of school closure in Italian students has not been previously evaluated. In particular, it is not known whether impact on lifestyle and mental health was different in younger compared to older students, in males compared to females and in children living in Regions with different COVID-9 epidemiology. This knowledge seems essential to understand which measures must be put in place in Italy to reduce potential health problems related to COVID-19 among older children and adolescents that do not attend school to limit SARS-CoV-2 diffusion. To make a contribution in this regard a study was performed.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

This was a cross-sectional survey with the main aim to evaluate whether school closure during COVID-19 pandemic had caused in older children and adolescents significant modifications of the current lifestyle potentially associated with the development of significant psychological problems. Moreover, the role of some variables (knowledge of COVID-19 characteristics, age, gender, type of school, incidence of COVID-19 in the region where the student was living and presence of one or more relatives among SARS-CoV-2 infected subjects) in the development of psychological problems was tentatively evaluated. To collect data and ensure the confidentiality and reliability of the data an anonymous online questionnaire developed by pediatricians, infectious diseases specialists, child neuropsychiatrists and psychologists was used. Google Forms® was used to collect information from users. The questionnaire was disseminated through schools and private channels. The personal that were data collected were age, sex, type of school and region of residence. Participants accessed the questionnaire through a web link. Data collection took place for a period of <2 weeks (8–21 April 2020) 1 month after the beginning of school closures because of the COVID-19 lockdown. The privacy policy was approved by the Data Protection Office of the University of Parma. Expedited ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Parma, which conforms to the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki, 4 weeks after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic. Both parents and students had to provide their written consent.

The online survey was first disseminated to the parents of students of 2 secondary and 3 high schools with different educational orientations located in Parma. The schools were chosen among those with the highest number of students after the school administrators and the teachers had given their consent to allow the study to be carried out. With the teachers it was established that, on the day of the distribution of the questionnaire, they would explain to the students the meaning of the questionnaire and would clarify any doubts about its completion. To have information on the impact of the pandemic on students who lived in geographical areas less affected by the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the teachers at Parma schools were encouraged to contact some colleagues from Southern Regions, explain the importance of the survey and obtain the cooperation for the distribution of the questionnaire to their students. A total of 7 schools sited in Italian Regions other than Emilia-Romagna, the Region where Parma is sited, was involved in the study. The dissemination of the questionnaire took place in the same way as in Parma. The online form comprised six parts: (1) an introductory part addressed to parents that requested that they accept the privacy policy; (2) an introductory part aimed at students; and (3–6) the questionnaire parts. The authors drew from the measurement instruments of studies on the psychological impacts of SARS and influenza outbreaks that were mainly devoted to the evidence of the development of depression and anxiety (12, 13) and included additional questions related to the COVID-19 outbreak. The structured questionnaire (Table 1) consisted of questions covering several areas: (1) demographic data and school locations, (2) knowledge and concerns about COVID-19, (3) additional information related to COVID-19, (4) the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak, and (5) mental health status.

Statistical Analysis

The continuous variable “age” was characterized as the mean ± standard deviation, and the categorical variables (gender, region of residence, type of school, age group, and frequency) for each item were characterized by frequencies and percentages. The age groups considered in the analysis were 11–13 and 14–19 years old. The Wilcoxon rank–sum test was used to compare the difference in age between groups. The chi–square test or Fisher's exact test, when the frequency was ≤5, was performed to compare the frequency of answers for each question between groups. The same tests were used to compare the difference in the frequency of a single response between groups. For better assessing impact of pandemic on psychological status of enrolled children a negative feeling index was developed. It was calculated as the sum of the following dichotomous variables: presence of fear, restless, sadness, and variation in the hours of sleep, considered 0 for absence and 1 for presence. A multivariate regression model to assess the association between the negative feelings index and a series of variables, such as age in years, sex, and personal experience of at least one relative or acquaintance with COVID-19. All statistical analyses were performed by using Stata Statistical Software: Release 12 (College Station, TX, USA).

Results

General Characteristics of the Study Population

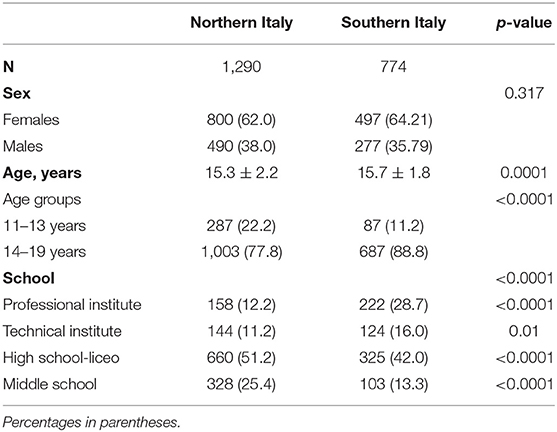

Table 2 summarizes the general characteristics of the study population. A total of 2,064 students (62.8% females; mean age, 15.4 ± 2.1 years), 69% of those initially included in the study, completed and returned the questionnaire. Subjects who did not return the questionnaire were equally distributed among northern and southern students, without differences regarding age, gender and type of school. Among those who returned the questionnaire, 1,290 (62.5%) were residents in northern Italian regions, mainly Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna, while 774 (37.5%) lived in southern regions, mainly Sicily and Puglia. In both northern and southern Italy, females represented approximately two-thirds of the studied population. However, individuals aged 14–19 years and those who were attending high school were significantly more numerous in the northern regions than in the southern regions, where subjects aged 11–13 years and those attending professional and technical schools were more numerous.

Knowledge of Covid-19

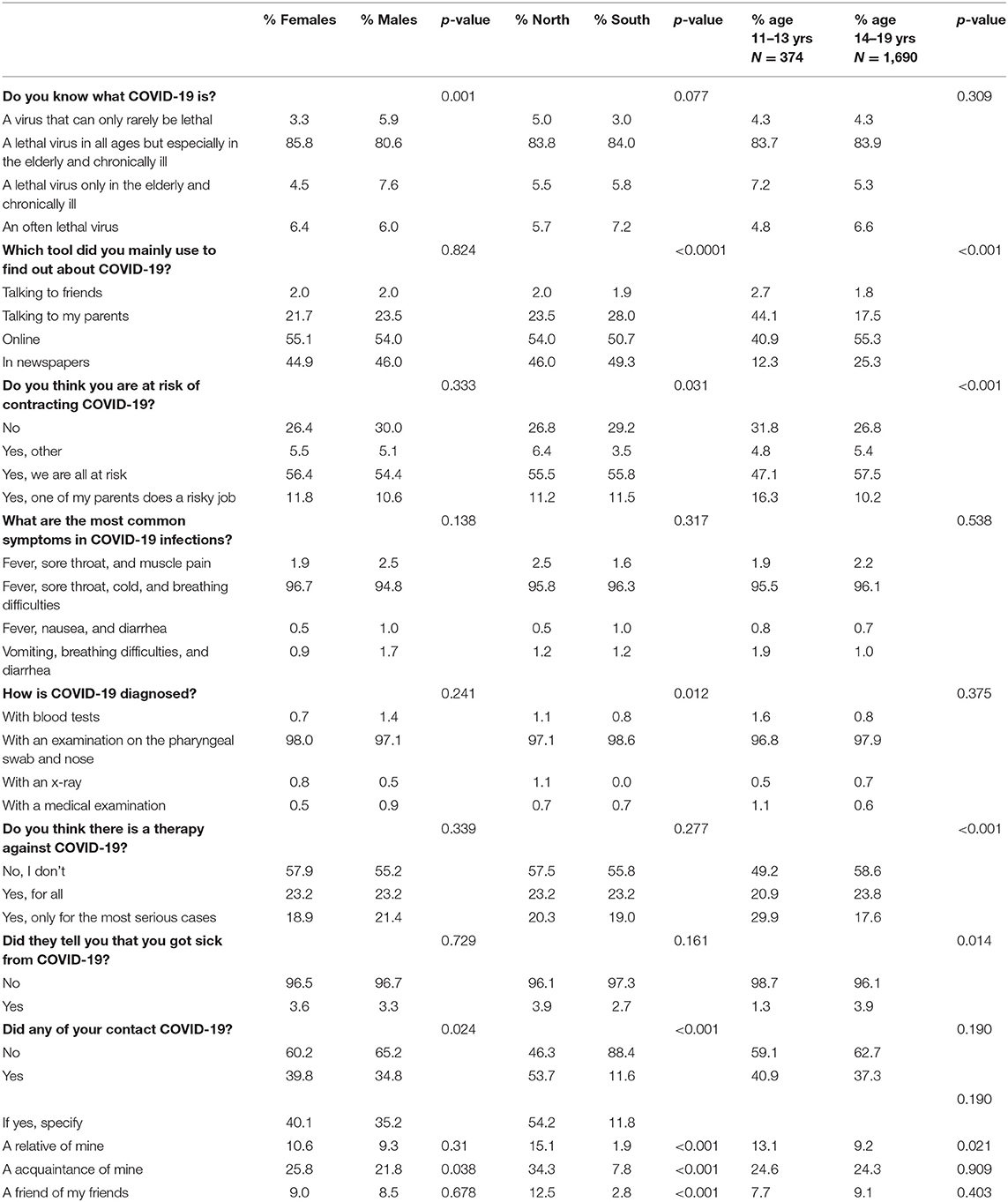

Table 3 summarizes knowledge about Covid-19 in the study population according to gender, area of residence and age. Most students evidenced the high lethality and lack of effective therapy of COVID-19. The lethality of COVID-19 was significantly more frequently highlighted by females than males (p < 0.01), while the lack of an effective therapy for the disease was more frequently reported by older students (58.6 vs. 49.2%; p < 0.001), Knowledge about symptoms and diagnosis of COVID-19, and personal risk of infection was generally good, without significant differences according to sex, age, type of school, and geographic area of origin. Mass media were largely used by all the students to access information on COVID-19. However, while mass media were the most frequently used tools by older students, parents were the source of information most frequently consulted by children under 13 years of age. Personal experience with a relative or an acquaintance affected by COVID-19 was significantly more frequently reported by northern students than by southern students (53.7 vs. 11.6%; p < 0.001).

Table 3. Knowledge about COVID-19 in the study population according to gender, area of residence, and age.

Lifestyle

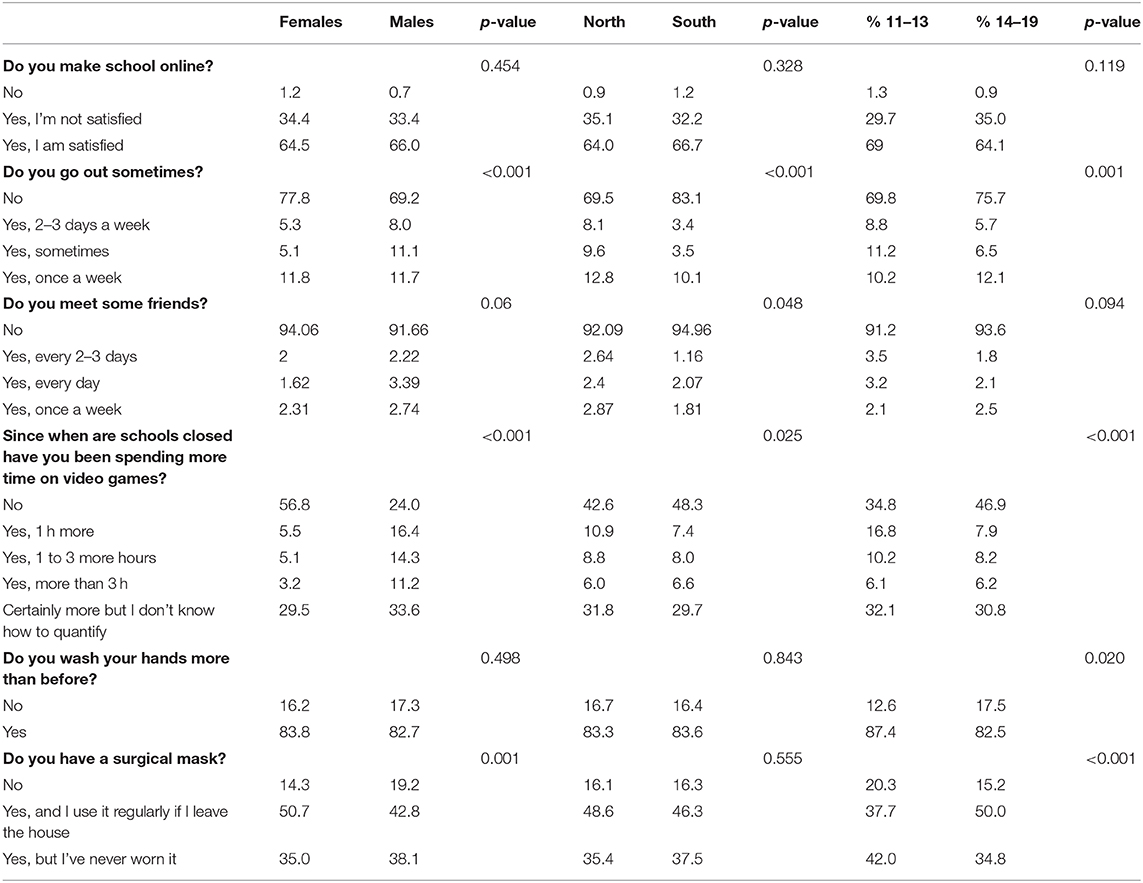

Table 4 summarizes the questionnaire results about lifestyle during pandemic period. Of the total sample, 65% said they were satisfied with doing school online, without significant differences between the groups. Regarding leaving home, 74.6% said they did not go out, while 11.8% went out only once a week. Among those who responded “I don't go out,” there were statistically significant differences by gender, age group, and region with females, older children, and subjects living in the Southern Regions the subjects with the greater tendency to remain at home. For a greater use of video games than before, a significantly higher frequency was found in males (76%) and the 11–13-year age group (65%) than in females (43%) and the 14–19-year age group (53%).

Table 4. Psychological impact of school closure because of COVID-19 lock-down in the study population according to gender, area of residence, and age.

No differences between groups were found for the question about “washing my hands more than before” except for by age group: 87.4% of the 11–13-year group and 82.5% of the 14–19-year group reported washing their hand more than before (p < 0.01). Differences were found for the habit of using the surgical mask between males and females and the two age groups, with males and older adolescents using face masks less than females and younger adolescents (p < 0.001). However, no differences were evidenced among Northern and Southern students.

Psychological Impact of Covid-19

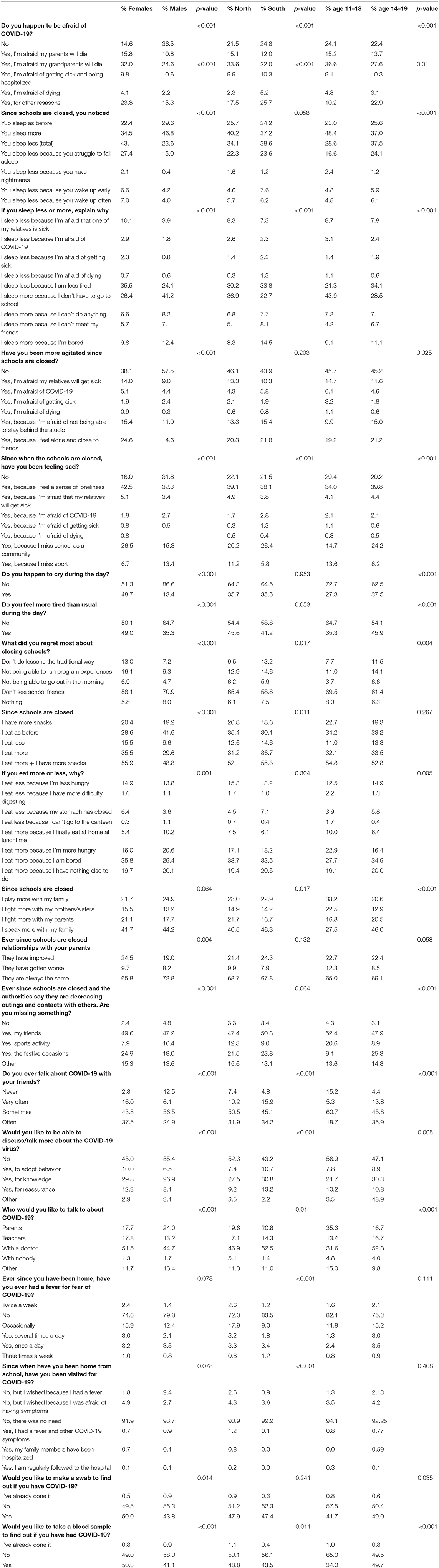

Table 5 shows the psychological impact of school closures due to the COVID-19 lockdown in the study population. As shown, problems were evidenced in all the study groups, although with greater frequency among females, and students living in the regions with greater incidence of COVID-19. This was clearly evidenced when fear of Covid-19 was considered. This was reported in 85.4% of females and in 63.5% of males (p < 0.001). Moreover, fear of losing grandparents was more common in the northern regions (33.6%) than in the southern regions (22%) (p < 0.001) and in the 11–13-year age group (36.6%) than the 14–19-year age group (27.6%; p < 0.001). The feeling of sadness was significantly more frequent in females (84%) than in males (68.2%) (p < 0.001) and in the 14–19-year age group (79.2%) (p < 0.001). Loneliness was identified as the primary cause of sadness in all groups (ranging from 32.3% of males to 42.5% of females). Missing the school community was a significantly more common cause of sadness in girls (26.5% vs. 16.8%; p < 0.001), in the southern regions (26.45% vs. 20.2%; p < 0.01) and in the 14–19-year-old group (24.2% vs. 14.7%; p < 0.001). In addition, 48.7% of females reported crying during the day (13.4% in males; p < 0.001). A sense of fatigue was more frequent in females than in males (p < 0.05) and in the 14–19-year age group than in the 11–13-year age group (p < 0.001). No differences were found between northern and southern Italy. Similarly, a sense of agitation was more frequent in females than males (61.9% vs. 42.5%; p < 0.001). The ability to see classmates was the aspect that was most commonly missed by adolescents during school closures regardless of gender, age group, or geographic location.

Table 5. Questionnaire results about lifestyles during school closure because of COVID-19 lockdown in the study population according to gender, area of residence, and age.

Since schools had been closed, males reported sleeping more than before (46.8%), while 43.1% of females stated they slept less than before (p < 0.001). An analysis of these data by age group showed that the younger students (11–13 years) were more likely than older students to report sleeping more than before school closures (p < 0.001). Difficulty falling asleep was the most frequent reason for sleeping less among the groups. A lack of interaction with schoolmates/friends was the main reason for displeasure in all groups, with significant differences between males and females (70.9% vs. 58.1%; p < 0.001), between students in the northern and southern regions (65.4% vs. 58.8%; p < 0.01) and between age groups (11–13 years, 69.5%; 14–19 years, 61.4%; p < 0.01). A lack of sports activity was significantly more frequent in the 11–13-year age group (20.6% vs. 8.9%) and in males (16.4% vs. 7.9%; p < 0.001).

Most of the subjects reported eating more during the quarantine period, with a statistically significant difference between males and females (48.8 vs. 55.9%; p < 0.01). Of particular interest were the data concerning the relationship with parents: 68.4% of the sample declared that their relationships had remained the same, 24.5% of the females reported that their relationships had improved (compared to 19.0% of the males; p < 0.01). In addition, most of the teenagers said that they spoke more with their parents (42.6%), with a higher percentage of students in norther than southern Italy (46.3 vs. 40.5%; p < 0.05) and a higher percentage of students in the 14–19-year age group than the 11–13-year age group (46.0 vs. 27.5%; p < 0.01) reporting this change.

When asked if they talked about Covid-19 with friends, 50.1% of the students from the southern regions reported doing so often or very often (vs. 42.1% of the students from the northern regions). The responses to the question asking who students would like to talk about the virus, similar percentages were found between regions: 52.5% of southern students said they would like to speak with a doctor (vs. 46.9% of northern students).

To understand the degree of fear that teenagers experienced, we asked them whether they had taken their temperature during the quarantine and, if so, how many times. The resulting data were: 6.2% of the females and 5.6% of the males said they had taken their temperature once or several times a day. However, approximately 52% of the sample replied that they did not want to undergo a swab test (51.7%) or provide a blood sample (52.3%) to determine if they had–or had previously had–the virus.

A global evaluation of all these findings through the feeling index showed that school closure impact on mental health was slightly greater in females and in subjects living in the Northern Regions possibly due to the greater clinical relevance of COVID-19 in these areas and the greater personal experience with a relative or an acquaintance affected by this disease. The multivariate regression analysis showed that male sex was a protective factor against negative feelings (p < 0.01), leading to a decrease of 0.63 points in the total negative feelings index. Having a family member or an acquaintance with COVID-19 increased the negative feelings index by 0.1 points (p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, most students who completed the administered questionnaire showed good knowledge of the epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic characteristics of COVID-19, as well as of disease risks, regardless of sex, age, location, and type of school. Only the source of information was slightly different in younger students than the older ones. Younger students preferred to consult with parents, while older students drew most of their knowledge on COVID-19 from mass media, likely due to the increased autonomy of adolescents with age (14). Teenagers' good knowledge of COVID-19 even in Italian Regions where diffusion of COVID-19 was relatively low is not surprising, as the outbreak of the pandemic has had profound impact on all aspects of people's everyday lives, mainly because of the very restrictive preventive measures put in place by most governments, including the closure of factories, commercial activities and schools (14). All these findings have had very wide resonance in the mass media and it is highly likely that they have been repeatedly discussed within families mainly because of the organization of the distance learning (15). Adolescents were therefore widely informed about COVID-19 and the evolution of the pandemic. Moreover, with school closures and the need to be compliant with recommendations by authorities, teenagers in most countries have personally experienced several conditions that have made them aware of the medical, social, and economic consequences of COVID-19 (16).

Modifications of lifestyle were also clearly evidenced in the population that participated in the study, but with slight differences according to sex, age, and location. In general, they seem related to both school closure that prevented socialization and the good knowledge of the danger of COVID-19 which led to a good acceptance of the health authority recommendations for COVID-19 spread containment (17, 18). However, adherence to some of these, such as frequent hand washing and use of masks, was greater among females than among males. This seems to confirm what has been repeatedly reported in more complex studies, i.e., that girls are more compliant than boys with the requests and demands of parents, teachers, and other authorities (19).

This study shows that school closures because of the COVID-19 lockdown have several negative psychological consequences among adolescents, even when they have not been infected with SARS-CoV-2. As expected, negative feeling was more common among subject living in northern regions where children and adolescents have had more frequent opportunities to see directly the clinical significance of COVID-19. Impaired mental health in conditions such as those due to COVID-19 pandemic has been previously shown by several studies evidencing that home confinement of children and adolescents cause uncertainty and anxiety which is ascribable to disruption in education, physical activities and socialization (20). Results quite similar to those of this study have been recently reported by Zhou et al. (12), who surveyed 8,079 Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak and reported symptoms of depression, anxiety and combined depression and anxiety in 43, 37, and 31% of the adolescents, respectively. As found in this study, in the previous study psychological symptoms were significantly more common among females. The prevalence of mental disorders among females is not surprising because, independent of the pandemic outbreak, anxiety, and depressive symptoms are generally more common among women, even in the adolescent period (13). On the other hand, questions included in the questionnaire were focused on the evidence of internalizing symptoms that are generally more common among females and not on externalizing problems such as rule–breaking actions and aggressive behavior, that are more frequently diagnosed in males (19). However, the incidence of psychological problems in the studied population was also significant among males, highlighting that all adolescents may suffer from psychological problems when facing unexpected dangerous events. In addition, adolescence is a crucial period of life characterized by multiple physical, emotional, and social changes that expose the individual to several risk factors for the development of mental health problems. Up to 20% of adolescents suffer from mental disabilities, mainly depression and anxiety (21, 22), and it is not surprising that the emergence of a stressful event such as a pandemic outbreak would make these conditions even more evident, particularly when the event is associated with school closures that reduce social connections and access to mental health services. A study carried out in the UK (13) involving more than 2100 adolescents with mental problems showed that most of them (83%) had experienced a worsening of their mental conditions. More than a quarter of enrolled subjects reported that they were no longer able to access mental health support.

At the beginning of the pandemic, considering previous experience with influenza (23), children and adolescents were considered among the major populations responsible for SARS-CoV-2 transmission; thus, to reduce risks, any type of school was closed in most of the countries. However, this decision was thoroughly discussed by many experts for several reasons (24). Although the actual role of pediatric patients as a cause of SARS-CoV-2 diffusion was not precisely defined, the possibility could not be excluded that adolescents could have a significant role in this regard (25); however, school closures could cause a number of social, mental, economic and nutritional problems that are even greater than those due to the infection. Our data on the psychological impact of school closures in children and adolescents because of COVID-19 lockdown highlight that school closures should be avoided and that school system infrastructure, the number of employees and their education on infectious disease prevention should be improved to ensure safe school attendance.

This study has several limitations. The sample size was small, and it is possible that it may not represent the Italian population of older children and adolescents due to the recruitment method and because of differential internet access. The use of the online tool limits access to persons who can use this technology, whereas in Italy, particularly in the Southern Regions, many students do not have adequate connection and personal computer. Moreover, collected data only refer to the first period of COVID-19 pandemic and it is possible that after a longer lockdown the impact of the pandemic could have been different. Finally, the study does not define whether lifestyle and mental health problems are simply due to school closure or the hard lockdown simultaneously decided by authorities.

Conclusions

Data collected with this study can be useful to show that school closures can cause substantial emotional uncertainty among adolescents and subjects living in geographic areas with high incidence of COVID-19 cases. This indicates the relevance of a strict monitoring of mental health of older children and adolescents during school closure and the need for schools to be reopened as soon as possible accordingly with the evolution of the pandemic.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Parma, Parma, Italy. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

SE designed the study, participated in data analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NG participated in enrolment and data entry. AS evaluated the psychological results. CN and AA performed data entry and statistical analysis. PM participated in data entry and performed the literature review. NC gave a substantial scientific contribution. NP co-wrote the first draft of the manuscript and made substantial scientific contributions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by a research grant from Academic Department of Pediatrics (DPUO), Research Unit of Congenital and Perinatal Infections, Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital, Rome, Italy.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Sim K, Huak Chan Y, Chong PN, Chua HC, Wen Soon S. Psychosocial and coping responses within the community health care setting towards a national outbreak of an infectious disease. J Psychosom Res. (2010) 68:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.004

2. Hsieh KY, Kao WT, Li DJ, Lu WC, Tsai KY, Chen WJ, et al. Mental health in biological disasters: from SARS to COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2020). doi: 10.1177/0020764020944200. [Epub ahead of print].

3. Gale SD, Berrett AN, Erickson LD, Brown BL, Hedges DW. Association between virus exposure and depression in US adults. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 261:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.037

4. Chew QH, Wei KC, Vasoo S, Chua HC, Sim K. Narrative synthesis of psychological and coping responses towards emerging infectious disease outbreaks in the general population: practical considerations for the COVID-19 pandemic. Singapore Med J. (2020) 61:350–6. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2020046

5. Shigemura J, Harada N, Tanichi M, Nagamine M, Shimizu K, Katsuda Y, et al. Rumor-related and exclusive behavior coverage in internet news reports following the 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreak in Japan. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2015) 9:459–63. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.57

6. Van Bortel T, Basnayake A, Wurie F, Jambai M, Koroma AS, Muana AT, et al. Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at individual, community and international levels. Bull World Health Organ. (2016) 94:210–4. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.158543

7. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate Psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:E1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

8. Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102092. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092

9. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

10. Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. (2020) 174:819–20. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

11. Ministero della Salute. Nuovo Coronavirus. Covid-19, I Casi in Italia il 26 Aprile Ore 18. (2020). Available online at: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?area=nuovoCoronavirus&id=5351&lingua=italiano&menu=vuoto (accessed August 25, 2020).

12. Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, Guo ZC, Wang JQ, Chen JC, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 29:749–58. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4

13. Putwain DW. Test anxiety in UK schoolchildren: prevalence and demographic patterns. Br J Educ Psychol. (2007) 77:579–93. doi: 10.1348/000709906X161704

14. Murphy DA, Greenwell L, Resell J, Brecht ML, Schuster MA. Early and middle adolescents' autonomy development. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2008) 13:253–76. doi: 10.1177/1359104507088346

15. BBC. Coronavirus: The World in Lockdown in Maps and Charts. BBC (2020). Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52103747 (accessed May 5, 2020).

16. Schmitt DP, Long AE, McPhearson A, O'Brien K, Remmert B, Shah SH. Personality and gender differences in global perspective. Int J Psychol. (2017) 52 (Suppl 1):45–56. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12265

17. Armitage R, Nellums LB. Considering inequalities in the school closure response to COVID-19. Lancet Glob Health. (2020) 8:e644. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30116-9

18. Jiao WY, Wang LN, Liu J, Fang SF, Jiao FY, Pettoello-Mantovani M, et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr. (2020) 221:264–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013

19. Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Kramer MD, Krueger RF, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, et al. Gender differences and developmental change in externalizing disorders from late adolescence to early adulthood: a longitudinal twin study. J Abnorm Psychol. (2007) 116:433–47. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.433

20. Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. (2011) 378:1515–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1

21. Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, Gluzman S, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the world health organization's world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry. (2007) 6:168–76.

22. Youngminds. Youngminds.org.uk. Coronavirus: Impact on Young People With Mental Health Needs. (2020). Available online at: https://youngminds.org.uk/media/3708/coronavirus-report_march2020.pdf

23. Principi N, Esposito S. Influenza vaccine use to protect healthy children: a debated topic. Vaccine. (2018) 36:5391–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.016

24. Esposito S, Zona S, Vergine G, Fantini M, Marchetti F, Stella M, et al. How to manage children if a second wave of COVID-19 occurs. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. (2020) 24:1116–8. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0543

Keywords: adolescent, COVID-19, mask, psychological problems, SARS-CoV-2, school

Citation: Esposito S, Giannitto N, Squarcia A, Neglia C, Argentiero A, Minichetti P, Cotugno N and Principi N (2021) Development of Psychological Problems Among Adolescents During School Closures Because of the COVID-19 Lockdown Phase in Italy: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Pediatr. 8:628072. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.628072

Received: 10 November 2020; Accepted: 24 December 2020;

Published: 22 January 2021.

Edited by:

Dimitri Van der Linden, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, BelgiumReviewed by:

Delphine Jacobs, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, BelgiumDirk Van West, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Hayez Jean-yves, Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium

Copyright © 2021 Esposito, Giannitto, Squarcia, Neglia, Argentiero, Minichetti, Cotugno and Principi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susanna Esposito, c3VzYW5uYS5lc3Bvc2l0b0B1bmltaS5pdA==

Susanna Esposito

Susanna Esposito Nino Giannitto2

Nino Giannitto2 Cosimo Neglia

Cosimo Neglia Alberto Argentiero

Alberto Argentiero Nicola Cotugno

Nicola Cotugno Nicola Principi

Nicola Principi