94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Pediatr., 21 April 2017

Sec. Pediatric Pulmonology

Volume 5 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2017.00072

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Parallel March of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood: a Multi-Perspective ApproachView all 19 articles

This review updates the relationship between the adherence to Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) assessed by questionnaire and asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic eczema in childhood. It deals with the effect of MedDiet in children on asthma/wheeze, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis/eczema, and also with the effect of MedDiet consumption by the mother during pregnancy on the inception of asthma/wheeze and allergic diseases in the offspring. Adherence to MedDiet by children themselves seems to have a protective effect on asthma/wheezing symptoms after adjustment for confounders, although the effect is doubtful on lung function and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. By contrast, the vast majority of the studies showed no significant effect of MedDiet on preventing atopic eczema, rhinitis, or atopy. Finally, studies on adherence to MedDiet by the mother during pregnancy showed some protective effect on asthma/wheeze symptoms in the offspring only during the first year of life, but not afterward. Very few studies have shown a protective effect on wheezing, current sneeze, and atopy, and none on eczema. Randomized control trials on the effect of the adherence to MedDiet to prevent (by maternal consumption during pregnancy) or improve (by child consumption) the clinical control of asthma/wheezing, allergic rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis are needed.

Diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic eczema have increased in the last decades, and the highest incidence seems to occur among children (1). One of the explanations of that increase from the environmental pint of view relates to changes in diet (2). The main components of the modern diet are foods which have been highly processed, modified, stored, and transported over great distances. Furthermore, some reports show a trend to consume higher amounts of saturated fats, such as burgers, and sugar such as soft drinks (3). By contrast, the traditional diet is produced and marketed locally and is eaten shortly after harvesting (4).

One of these traditional diets is the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet). The term MedDiet refers to dietary patterns in the Mediterranean region. MedDiet is characterized by a high intake of fruits and vegetables, bread and whole grain cereals, legumes, and nuts; low-to-moderate consumption of dairy products and eggs; and limited amounts of meat and poultry. This diet is low in saturated fatty acids and rich in antioxidants, carbohydrates, and fiber. It also has a high content of monounsaturated fatty acids and n − 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), mainly derived from olive oil (from fish in some areas) (5).

In the last decade, several epidemiological studies have reported a protective effect of MedDiet on asthma, rhinitis, and atopic eczema, while others did not find any protective effect of this diet on those conditions. Therefore, before nutritional therapy could be included in guidelines devoted to preventing the inception of asthma and allergic diseases in childhood, or to improving the clinical course of those diseases, it is necessary to have a complete view of the current evidence from epidemiological studies. Then, it is time to perform randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

The aim of the present review is to update the evidence on whether the adherence to MedDiet has some effect on asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic eczema in childhood.

We conducted an electronic literature search using Medline/PubMed and EMBASE in September 2016 and extended back to 1960. The terms used to search both in titles and in abstracts were “(((Mediterranean Diet)) AND ((asthma OR wheezing)) OR ((allergic rhinitis)) OR ((atopic dermatitis OR atopic eczema)) AND ((children))).” Only original studies with human subjects were included. No restriction was made for publication language or publishing status. Also, cross-referencing from the articles found was used to complete the search.

A total of 46 studies were retrieved electronically. Among those, 24 studies were excluded for the following reasons: reviews (n = 9), editorials (n = 6), systematic reviews (n = 4), no inclusion of MedDiet (n = 1), adult population (n = 2), different outcome (n = 1), and clinical trial design (n = 1). Therefore, 22 original studies were included in the present review. All were observational studies (cross-sectional, cohort, or case–control studies) and assessed the adherence to MedDiet by dietary information collected using food frequency questionnaires and scoring MedDiet by means of different scores.

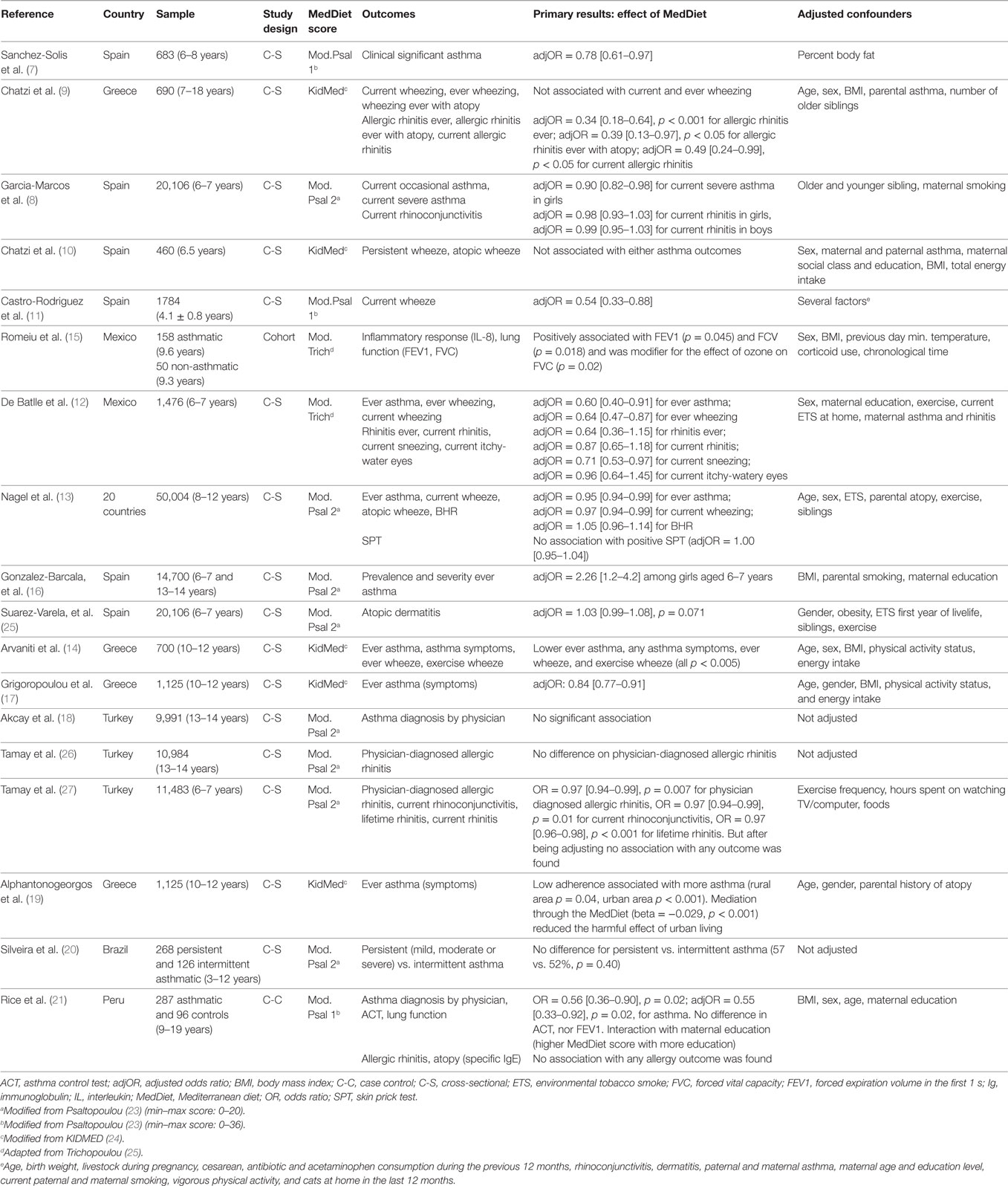

Fifteen studies were retrieved (Table 1) on this topic. We previously reported (6) eight of these studies (7–14) in a systematic review with a meta-analysis. In that review on 39,804 children, we found a negative association of “current wheezing” with the highest tertile of MedDiet score adherence (OR 0.85 [0.75–0.98]; p = 0.02). This result was driven by Mediterranean centers (0.79 [0.66–0.94], p = 0.009). A similar figure was found for “current severe wheeze” (OR 0.82 [0.55–1.22], p = 0.330 for all centers; and OR: 0.66 [0.48–0.90], p = 0.008 for Mediterranean centers). Mediterranean centers were centers <100 km from the Mediterranean coast.

Table 1. Summary of studies reporting the association between adherence to MedDiet and asthma/wheezing, allergic rhinitis, and dermatitis/eczema in children.

However, seven studies, most of them recently published, were not included in the aforementioned review (6). Two studies were performed in Greece (17, 19), and one in each of the following countries: Mexico (15), Spain (16), Turkey (18), Brazil (20), and Peru (21). In three studies, adherence to MedDiet was significantly associated with lower asthma symptoms (17, 19, 21). Additionally, adherence to MedDiet was significantly associated with improved lung function in one study (15), but not in another one (21). By contrast, one study (16) showed higher asthma prevalence among girls with higher adherence to MedDiet. In two studies (18, 20), no significant effect of MedDiet was found. Interestingly, an inverse mediating effect of MedDiet was observed for the urban environment–asthma relation (standardized beta = −0.029, p < 0.001), while physical activity had no significant contribution, adjusted for several confounders (19). A direct interaction of MedDiet with maternal education was found in one of the studies (21).

With respect to the association between MedDiet consumption and allergic rhinitis and/or atopic dermatitis, 8 studies were retrieved (Table 1). Two studies were carried out in each of Spain (8, 25) and Turkey (26, 27), one was worldwide (13), and one in each of the following countries: Greece (9), Peru (21), and Mexico (12). High adherence to MedDiet was significantly protective for allergic rhinitis and atopy in only one study (9) as measured by skin prick test (SPT). However, no effect on allergic rhinitis was demonstrated in the other four studies (8, 21, 26, 27). Moreover, no significant effect of MedDiet was demonstrated on atopic dermatitis (25), nor on atopic sensitization as defined either by specific IgE (21) or by SPT (13).

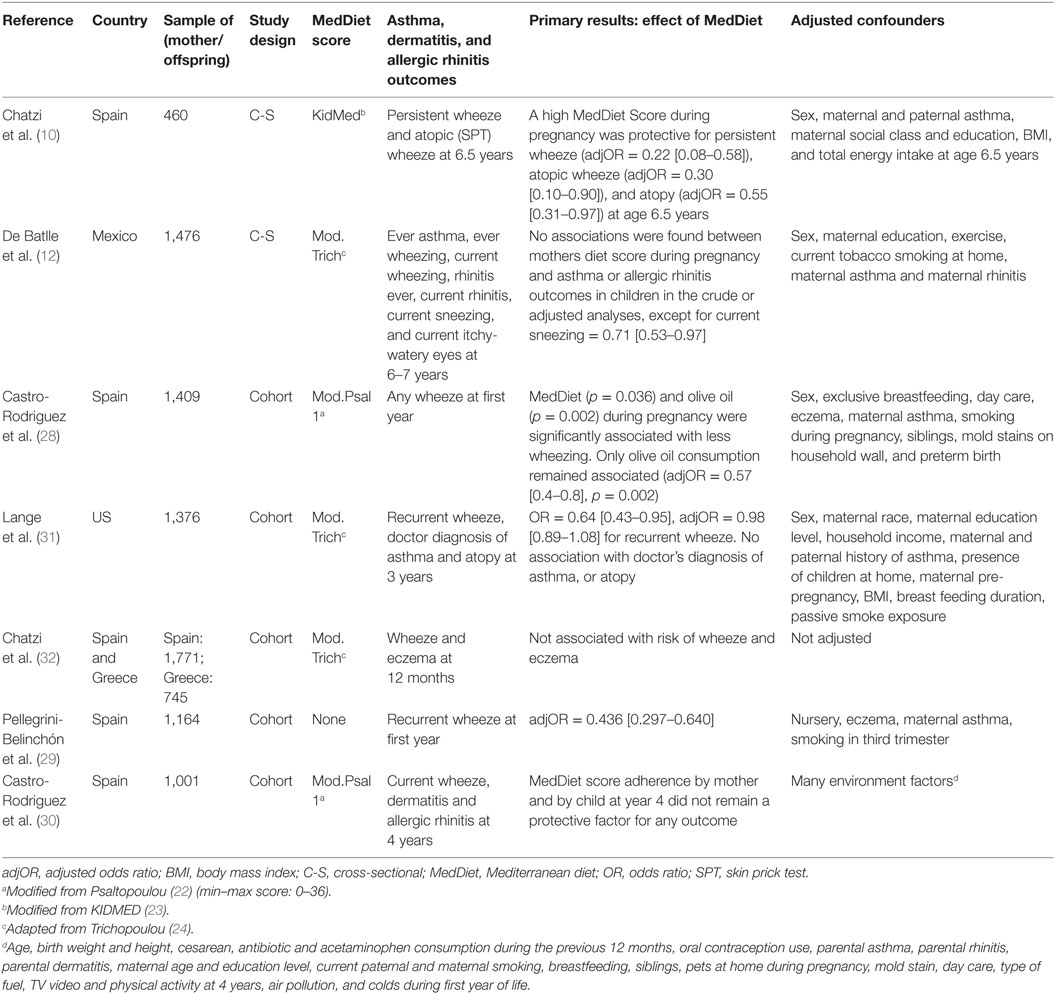

Seven studies that explore this effect were retrieved (Table 2). Four studies were done in Spain (10, 28–30), one in Mexico (12), one in the US (31), and one in Greece/Spain (32). In all of them, the outcome was asthma/wheeze. In three studies, atopic eczema/atopy was included (30–32), and in two studies, rhinitis was also included (12, 30). The offspring were surveyed at different times. In three studies, it was during the first year of life (28, 29, 32), at 3 years in one study (31), at 4 years in another one (30), and at 6.5 years of life in the others (10, 12).

Table 2. Summary of studies reporting the association between adherence to MedDiet during pregnancy and asthma/wheezing/allergic disease in offspring.

Adherence to MedDiet by the mother had a protective effect on wheeze during the first year of life in the offspring in one study (29), and this effect disappeared after adjusting for confounders in another study (28). In three studies (30–32), the effect of maternal MedDiet had no significant effect on wheeze. When combined maternal and child adherence to MedDiet was analyzed, only one study showed a protective effect on persistent and atopic wheezing, and atopy by SPT at 6.5 years of age (10). However, another study did not find any such association (30). Regarding atopic eczema and allergic rhinitis, adherence to MedDiet by the mother had no significant protective effect in the majority of the studies, except for one (12) in which maternal MedDiet consumption was protective for current sneeze in the offspring at 6–7 years of age.

In summary, adherence to MedDiet by children themselves seems to have a protective effect on asthma/wheezing symptoms after adjusting for confounders, but the effect is doubtful on lung function and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. By contrast, the vast majority of the studies showed no significant effect of MedDiet on preventing allergic diseases (atopic eczema, rhinitis, or atopy). Finally, studies on adherence to MedDiet by the mother during pregnancy showed some protective effect on asthma/wheeze symptoms in the offspring only during their first year of life, but not after. Only very few studies showed a protective effect on wheezing, current sneeze, and atopy. No study has shown any protective effect on atopic dermatitis.

The results of the protective effect of MedDiet on asthma/wheezing symptoms in children found in the present review expand the results reported in systematic reviews with meta-analyses previously carried out by our group (6) and by others (33). The present report also confirms the protective effect of MedDiet consumption by the mother on asthma or allergic diseases in their offspring, as was described in a different review published by our group (34) and by others (35, 36), suggesting some epigenetic effect of diet. However, no systematic review on the effect of MedDiet on other allergic diseases, i.e., rhinitis or atopic eczema has been previously published. In the present study, no effect was shown in seven out of eight studies.

In the past decades, one of the most important environmental changes worldwide has been that of diet patterns. Due to changes in dietary fat intake (by increasing n − 6 PUFAs and decreasing n − 3 PUFAs), through an increased production of prostaglandin (PG) E2 might have contributed to the increase in the prevalence of asthma (37). PGE2 suppresses T-helper (Th) 1 and increases Th2 phenotype, thus reducing IFN-gamma. Th2 phenotype, in which there is an increase of IgE isotype switching, is associated with asthma and atopic diseases. On the other hand, diets low in antioxidants may have increased the susceptibility to develop asthma (38). In this case, the proposed mechanism involves the decline of lung antioxidant defenses, resulting in increased oxidant-induced airway damage.

Several of those studies reported on the beneficial effect of single foods rich in n − 3 PUFA or antioxidants on asthma or allergic diseases. A meta-analysis concluded that increased consumption of vegetables and fruits, zinc, and vitamins A, D, and E, is related to lower prevalence of asthma and wheeze in children and adolescents (36). However, most of the studies included in that meta-analysis fail to account for the interactions between nutrients (39). Yet, since our normal eating behavior is to follow certain diet patterns that contain many specific foods, it seems reasonable to put the focus on food patterns or diets.

Mediterranean diet is rich in both antioxidants and cis-monounsaturated fatty acids. Moreover, cereals (whole grain) are rich in vitamin D, phenolic acids, and phytic acid. Moreover, fruits, vegetables, and legumes are rich in vitamins C and E, carotenoids, selenium, and flavonoids (5). Additionally, olive oil for cooking and dressing salads is an important part of MedDiet. The main active components of olive oil are oleic acid, phenolic derivatives (hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol, oleuropein, and ligstroside), and squalene, all of which have been found to exhibit a marked antioxidant activity. Also, oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol (its hydrolysis product) are among the most potent antioxidants (40). One study has shown that, after a multivariate analysis, olive oil consumption by the mother during pregnancy, but not MedDiet, remained as a protective factor (aOR = 0.57 [0.4–0.9]) for wheezing during the first year of life in the offspring (28). Therefore, it seems reasonable to think that a higher adherence to MedDiet or olive oil may have some protective effects on asthma and allergic diseases in childhood. The ability of this diet to counteract oxidative stress might have an effect on asthma inception (41).

All studies included in the present review were observational (cross-sectional, cohort, and case–control) studies. All but one of them used three different MedDiet scores: one modified from Psaltopoulou (22), one modified from KIDMED (23), and another one adapted from Trichopoulou (24). Seventeen studies come from Mediterranean countries (nine from Spain, five from Greece, and three from Turkey). While these observational studies have reported potentially beneficial associations with MedDiet on asthma/wheezing, it is unknown whether an intervention to promote the MedDiet could reduce the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases in children.

Currently, there are no RCTs testing the hypothesis that adherence to MedDiet could decrease the risk of asthma and allergic disease in children. One pilot RCT in pregnant Scottish women at high risk of having asthmatic or allergic offspring is ongoing (42). It aims are to establish recruitment, retention, and acceptability of the dietary intervention and to assess the likely impact of the intervention on adherence to a MedDiet during pregnancy through seeking a reduction in the incidence of asthma and allergic problems (42). In adults, only one 12-week open-label trial was published (43). In that small study, 38 asthmatic adults were randomized to receive either 41 h of dietician services or only 2 h of services, or just one dietician session and recipes (control). The study achieved its primary outcome of altering the eating habits of participants in the high-intensity intervention toward a MedDiet pattern. The study had not enough power to detect clinical endpoints; however, non-significant improvements in asthma-related quality of life, asthma control, or spirometry were observed in the intervention groups (43).

Adherence to MedDiet by children seems to have a protective effect on asthma/wheezing symptoms, but not on allergic rhinitis, eczema, or atopy. Adherence to MedDiet by the mother during pregnancy might have some protective effect on asthma/wheeze symptoms in the offspring only during their first year of life, and few studies have shown some protective effect on current sneeze and atopy, but none on eczema. Randomized control trials on MedDiet adherence to test the real usefulness on primary prevention (by maternal consumption during pregnancy) or on clinical improvement (by patient consumption) of asthma/wheezing, allergic rhinitis, and dermatitis in childhood are needed.

JC-R contributed to the study concept, literature search, data collection, and manuscript writing. LG-M contributed to the literature search, data collection, and manuscript writing.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

No sponsorship from institutions or the pharmaceutical industry was provided to conduct this study. This work was supported by grant #1141195 from Fondecyt-Chile, to JC-R.

1. Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet (2006) 368(9537):733–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0

2. Arvaniti F, Priftis KN, Panagiotakos DB. Dietary habits and asthma: a review. Allergy Asthma Proc (2010) 31(2):e1–10. doi:10.2500/aap.2010.31.3314

3. Popkin BM, Haines PS, Siega-Riz AM. Dietary patterns and trends in the United States: the UNC-CH approach. Appetite (1999) 32(1):8–14. doi:10.1006/appe.1998.0190

4. Devereux G. The increase in the prevalence of asthma and allergy: food for thought. Nat Rev Immunol (2006) 6(11):869–74. doi:10.1038/nri1958

5. Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P. Healthy traditional Mediterranean diet: an expression of culture, history, and lifestyle. Nutr Rev (1997) 55(11 Pt 1):383–9. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01578.x

6. Garcia-Marcos L, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Weinmayr G, Panagiotakos DB, Priftis KN, Nagel G. Influence of Mediterranean diet on asthma in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol (2013) 24(4):330–8. doi:10.1111/pai.12071

7. Sanchez-Solis M, Valverde-Molina J, Pastor MD. Mediterranean diet is a protective factor for asthma in children 6–8 years old. Eur Respir J (2006) 50(Suppl):850s.

8. Garcia-Marcos L, Canflanca IM, Garrido JB, Varela AL, Garcia-Hernandez G, Guillen-Grima F, et al. Relationship of asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis with obesity, exercise and Mediterranean diet in Spanish schoolchildren. Thorax (2007) 62(6):503–8. doi:10.1136/thx.2006.060020

9. Chatzi L, Apostolaki G, Bibakis I, Skypala I, Bibaki-Liakou V, Tzanakis N, et al. Protective effect of fruits, vegetables, and the Mediterranean diet on asthma and allergies among children in Crete. Thorax (2007) 62(8):677–83. doi:10.1136/thx.2006.069419

10. Chatzi L, Torrent M, Romieu I, Garcia-Esteban R, Ferrer C, Vioque J, et al. Mediterranean diet in pregnancy is protective for wheeze and atopy in childhood. Thorax (2008) 63:507–13. doi:10.1136/thx.2007.081745

11. Castro-Rodriguez JA, Garcia-Marcos L, Alfonseda Rojas JD, Valverde-Molina J, Sanchez-Solis M. Mediterranean diet as a protective factor for wheezing in preschool children. J Pediatr (2008) 152(6):823–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.01.003

12. De Batlle J, Garcia-Aymerich J, Barraza-Villarreal A, Anto JM, Romieu I. Mediterranean diet is associated with reduced asthma and rhinitis in Mexican children. Allergy (2008) 63(10):1310–6. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01722.x

13. Nagel G, Weinmayr G, Kleiner A, Garcia-Marcos L, Strachan DP. Effect of diet on asthma and allergic sensitisation in the International Study on Allergies and Asthma in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase Two. Thorax (2010) 65(6):516–22. doi:10.1136/thx.2009.128256

14. Arvaniti F, Priftis KN, Papadimitriou A, Papadopoulos M, Roma E, Kapsokefalou M, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean type of diet is associated with lower prevalence of asthma symptoms, among 10–12 years old children: the PANACEA study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol (2011) 22(3):283–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01113.x

15. Romieu I, Barraza-Villarreal A, Escamilla-Nunez C, Texcalac-Sangrador JL, Hernandez-Cadena L, Díaz-Sánchez D, et al. Dietary intake, lung function and airway inflammation in Mexico city school children exposed to air pollutants. Respir Res (2009) 10(1):122. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-10-122

16. Gonzalez-Barcala FJ, Pertega S, Bamonde L, Garnelo L, Perez Castro T, Sampedro M, et al. Mediterranean diet and asthma in Spanish school children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol (2010) 21(7):1021–7. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01080.x

17. Grigoropoulou D, Priftis KN, Yannakoulia M, Papadimitriou A, Anthracopoulos MB, Yfanti K, et al. Urban environment adherence to the Mediterranean diet and prevalence of asthma symptoms among 10- to 12-year-old children: the Physical Activity, Nutrition, and Allergies in Children Examined in Athens study. Allergy Asthma Proc (2011) 32(5):351–8. doi:10.2500/aap.2011.32.3463

18. Akcay A, Tamay Z, Hocaoglu AB, Ergin A, Guler N. Risk factors affecting asthma prevalence in adolescents living in Istanbul, Turkey. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) (2014) 42(5):449–58. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2013.05.005

19. Alphantonogeorgos G, Panagiotakos DB, Grigoropoulou D, Yfanti K, Papoutsakis C, Papadimitriou A, et al. Investigating the associations between Mediterranean diet, physical activity and living environment with childhood asthma using path analysis. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets (2014) 14(3):226–33. doi:10.2174/1871530314666140826102514

20. Silveira DH, Zhang L, Prietsch SO, Vecchi AA, Susin LR. Association between dietary habits and asthma severity in children. Indian Pediatr (2015) 52(1):25–30. doi:10.1007/s13312-015-0561-x

21. Rice JL, Romero KM, Galvez Davila RM, Meza CT, Bilderback A, Williams DL, et al. Association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and asthma in Peruvian children. Lung (2015) 193(6):893–9. doi:10.1007/s00408-015-9792-9

22. Psaltopoulou T, Naska A, Orfanos P, Trichopoulos D, Mountokalakis T, Trichopoulou A. Olive oil, the Mediterranean diet, and arterial blood pressure: the Greek European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Am J Clin Nutr (2004) 80(4):1012–8.

23. Serra-Majem L, Ribas L, Ngo J, Ortega RM, García A, Pérez-Rodrigo C, et al. Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean diet quality index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr (2004) 7(7):931–5. doi:10.1079/PHN2004556

24. Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med (2003) 348(26):2599–608. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa025039

25. Suárez-Varela MM, Alvarez LG, Kogan MD, Ferreira JC, Martínez Gimeno A, Aguinaga Ontoso I, et al. Diet and prevalence of atopic eczema in 6 to 7-year-old schoolchildren in Spain: ISAAC phase III. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol (2010) 20(6):469–75.

26. Tamay Z, Akcay A, Ergin A, Guler N. Effects of dietary habits and risk factors on allergic rhinitis prevalence among Turkish adolescents. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol (2013) 77(9):1416–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.05.014

27. Tamay Z, Akcay A, Ergin A, Güler N. Dietary habits and prevalence of allergic rhinitis in 6 to 7-year-old schoolchildren in Turkey. Allergol Int (2014) 63(4):553–62. doi:10.2332/allergolint.13-OA-0661

28. Castro-Rodriguez JA, Garcia-Marcos L, Sanchez-Solis M, Pérez-Fernández V, Martinez-Torres A, Mallol J. Olive oil during pregnancy is associated with reduced wheezing during the first year of life of the offspring. Pediatr Pulmonol (2010) 45(4):395–402. doi:10.1002/ppul.21205

29. Pellegrini-Belinchón J, Lorente-Toledano F, Galindo-Villardón P, González-Carvajal I, Martín-Martín J, Mallol J, et al. Factors associated to recurrent wheezing in infants under one year of age in the province of Salamanca, Spain: is intervention possible? A predictive model. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) (2016) 44(5):393–9. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2015.09.001

30. Castro-Rodriguez JA, Ramirez-Hernandez M, Padilla O, Pacheco-Gonzalez RM, Pérez-Fernández V, Garcia-Marcos L. Effect of foods and Mediterranean diet during pregnancy and first years of life on wheezing, rhinitis and dermatitis in preschoolers. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) (2016) 44(5):400–9. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2015.12.002

31. Lange NE, Rifas-Shiman SL, Camargo CA Jr, Gold DR, Gillman MW, Litonjua AA. Maternal dietary pattern during pregnancy is not associated with recurrent wheeze in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2010) 126(2):.e1–4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.009

32. Chatzi L, Garcia R, Roumeliotaki T, Basterrechea M, Begiristain H, Iñiguez C, et al. Mediterranean diet adherence during pregnancy and risk of wheeze and eczema in the first year of life: INMA (Spain) and RHEA (Greece) mother-child cohort studies. Br J Nutr (2013) 110(11):2058–68. doi:10.1017/S0007114513001426

33. Lv N, Xiao L, Ma J. Dietary pattern, and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Asthma Allergy (2014) 7:105–21. doi:10.2147/JAA.S49960

34. Beckhaus AA, Garcia-Marcos L, Forno E, Pacheco-Gonzalez RM, Celedón JC, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Maternal nutrition during pregnancy and risk of asthma, wheeze, and atopic diseases during childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy (2015) 70(12):1588–604. doi:10.1111/all.12729

35. Nurmatov U, Devereux G, Sheikh A. Nutrients and foods for the primary prevention of asthma and allergy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2011) 127(3):.e1–30. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.001

36. Netting MJ, Middleton PF, Makrides M. Does maternal diet during pregnancy and lactation affect outcomes in offspring? A systematic review of food-based approaches. Nutrition (2014) 30(11–12):1225–41. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2014.02.015

37. Black PN, Sharpe S. Dietary fat and asthma: is there a connection? Eur Respir J (1997) 10(1):6–12. doi:10.1183/09031936.97.10010006

38. Seaton A, Godden DJ, Brown K. Increase in asthma: a more toxic environment or a more susceptible population? Thorax (1994) 49(2):171–4. doi:10.1136/thx.49.2.171

39. Jacobs DR Jr, Steffen LM. Nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns as exposures in research: a framework for food synergy. Am J Clin Nutr (2003) 78(3 Suppl):508S–13S.

40. Owen RW, Giacosa A, Hull WE, Haubner R, Würtele G, Spiegelhalder B, et al. Olive-oil consumption and health: the possible role of antioxidants. Lancet Oncol (2000) 1:107–12. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00015-2

41. Vardavas CI, Papadaki A, Saris WH, Kafatos AG. Does adherence to the Mediterranean diet modify the impact of smoking on health? Public Health (2009) 123:459–60. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2009.02.001

42. Sewell DA, Hammersley VS, Devereux G, Robertson A, Stoddart A, Weir C, et al. Investigating the effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet in pregnant women for the primary prevention of asthma and allergy in high-risk infants: protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials (2013) 14:173. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-14-173

Keywords: allergic rhinitis, asthma, children, dermatitis, Mediterranean diet, review, wheezing

Citation: Castro-Rodriguez JA and Garcia-Marcos L (2017) What Are the Effects of a Mediterranean Diet on Allergies and Asthma in Children? Front. Pediatr. 5:72. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00072

Received: 18 November 2016; Accepted: 24 March 2017;

Published: 21 April 2017

Edited by:

Philip Keith Pattemore, University of Otago, New ZealandReviewed by:

Sneha Deena Varkki, Christian Medical College & Hospital, IndiaCopyright: © 2017 Castro-Rodriguez and Garcia-Marcos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, amFjYXN0cm8xN0Bob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.