- 1Zuckerman Mind Brain and Behavior Institute, Jerome L. Greene Science Center, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

- 2Department of Dermatology, Columbia University Medical Center, Saint Nicholas Avenue, New York, NY, United States

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a highly prevalent and complex condition arising from chemotherapy cancer treatments. Currently, there are no treatment or prevention options in the clinic. CIPN accompanies pain-related sensory functions starting from the hands and feet. Studies focusing on neurons in vitro and in vivo models significantly advanced our understanding of CIPN pathological mechanisms. However, given the direct toxicity shown in both neurons and non-neuronal cells, effective in vivo or in vitro models that allow the investigation of neurons in their local environment are required. No single model can provide a complete solution for the required investigation, therefore, utilizing a multi-model approach would allow complementary advantages of different models and robustly validate findings before further translation. This review aims first to summarize approaches and insights from CIPN in vivo models utilizing small model organisms. We will focus on Drosophila melanogaster CIPN models that are genetically amenable and accessible to study neuronal interactions with the local environment in vivo. Second, we will discuss how these findings could be tested in physiologically relevant vertebrate models. We will focus on in vitro approaches using human cells and summarize the current understanding of engineering approaches that may allow the investigation of pathological changes in neurons and the skin environment.

Introduction

The discovery and optimization of chemotherapy has significantly contributed to an increase in survival for cancer patients in recent decades (1, 2). Despite the increasing discovery of alternative treatment options in cancer treatment, chemotherapy remains a major first-line therapy for most cancer patients (3–6). With increasing survival rates, adverse sequelae of chemotherapeutic treatment are a significant burden to patients, caregivers, and society (7). Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is one of the major side effects of chemotherapy, affecting up to over 60% of patients in short-term and long-term, more than 2 years after cessation of treatment (8–13). CIPN is predominantly sensory, but motor and autonomic symptoms are also reported. Symptoms include pain-related sensory dysfunction, starting in the hands or feet. CIPN severely reduces patients' quality of life in the long term and can adversely affect patients' survival by limiting required chemotherapy treatment (8, 14). Despite active investigation, the underlying pathological mechanisms are still unclear, and treatment or prevention strategies are unavailable in the clinic (8–10, 15, 16).

The most commonly used chemotherapeutic agents can be classified into six different groups: taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel), platinum-based antineoplastics (oxaliplatin, cisplatin, carboplatin), proteosome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib), vinca alkaloids (vincristine, vinblastine, vinorelbine), epothilones (ixabepilone), and immunomodulatory drugs (thalidomide, pomalidomide, lenalidomide) (17, 18). Mechanisms of how these chemotherapeutic agents induce apoptosis of cancer cells are reviewed elsewhere (17, 18). As these chemotherapeutic agents target diverse cellular pathways, agent-specific and common symptoms are reported. Cumulative doses are strongly correlated with CIPN severity (19). Common symptoms affecting somatosensation include paresthesia (abnormal sensation) such as tingling and pins and needles, numbness, and pain, which usually start from the hands and feet and may accompany mild motor neuropathy (19, 20). In addition, diverse pain-related symptoms are reported, including allodynia, hyper or hypoalgesia, burning or shooting pain, or pain that may be more painful than original cancer (20, 21). Of these patients, ~30% of patients develop pain (21, 22). Currently, there are no prevention or approved treatment options in the clinic, and the clinical intervention is limited to symptomatic relief provided by opioid analgesics, antidepressants, or anticonvulsants (11, 23, 24). Duloxetine is the only approved option for CIPN, and clinical trials have shown to reduce the pain severity in a subpopulation of affected patients (25, 26). Other options include gabapentin, with limited efficacy, while it is an effective option for other types of peripheral neuropathy (17). Sex-specific sensitivity of CIPN is debatable, however, females showed a higher risk for the development and severity in rodent models (27–29).

Extensive studies were performed to elucidate underlying pathological mechanisms, identify biomarkers, develop standard clinical assessments, and identify and validate cellular and genetic targets that may prevent or reverse CIPN (17, 30, 31). Many promising results from these preclinical studies exist, yet no treatments are currently approved for use in the clinic. An incomplete understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms may underlie these unmet needs (8–11). As sensory neurons are primary targets of many chemotherapeutics, many studies have focused on neuron intrinsic mechanisms underlying CIPN pathology. These studies reported transcriptional changes in DRGs, structural changes in axons, and their terminals within the epidermal layer. Notably, a strong correlation was shown between intraepidermal nerve fiber density (nociceptive neuron terminals residing in the epidermis) and the CIPN severity in both patients and animal models (32). However, nerve fiber density does not correlate with painful symptoms (33–36). These studies have identified several common pathological features from various types of chemotherapeutics. Common features include length-dependent axon degeneration, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, epidermal cell and the extracellular matrix (ECM) degeneration, and immune activation (10, 15, 37–41). Neuron-intrinsic pathways mediating survival (41–47) and transcriptional and translational changes (48–52) have also been demonstrated as critical mechanisms of CIPN pathology.

Chemotherapeutics can also directly affect neighboring non-neuronal cells. Recent studies highlight the importance of neuronal interactions with their environment in both peripheral and central environments involving the immune system, Schwann cells, and epidermal layers of the skin (10, 53–65). Insights from these studies point to the importance of studying neuronal toxicity in the context of the local environment, yet how neurons interact with non-neuronal cells is only beginning to be understood and mostly unknown in the context of CIPN. To understand intercellular mechanisms, in vivo models or in vitro models that allow manipulation and monitoring of multiple cell types are required. Several recent CIPN studies have demonstrated Drosophila melanogaster as a simple and genetically tractable in vivo model that could fill knowledge gaps with conserved CIPN phenotypes and examples with successful translation to other mammalian models (42, 43, 66–72). Utilizing full advantages of Drosophila models as a part of multi-model approaches with physiologically relevant vertebrate models, such as rodent models or human engineered skin models, may provide significant insights into a deeper understanding of CIPN pathology.

Experimental Approaches to Study CIPN Mechanisms

Previous research on CIPN has primarily been conducted in vitro and in vivo using rodents (73), with the initial study of CIPN in rats in 1992 using cisplatin, a platinum-based chemotherapeutic (74). A recent systematic analysis of the literature on CIPN models discovered that, of 183 different models, 12 species were used, and 85.2% of these studies were conducted in rodents (73). The study then ranked the models in their efficacy in representing CIPN, as evaluated by assessing mechanical allodynia, thermal hyper and hypoalgesia, histological damage to the peripheral nervous system, and functional neurophysiological changes (73). The most efficacious models were determined to be rats and mice; however, the study also recognized that more research is needed in other potentially effective models, including Drosophila and zebrafish, which showed a consistent efficacy in driving CIPN phenotypes using paclitaxel, cisplatin, and bortezomib (65, 73, 75).

Rodent in vivo models of CIPN are typically adult mouse and rat models injected with chemotherapeutics via intraperitoneal or intravenous injections, mimicking chemotherapeutic treatment for patients to recapitulate pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics (73, 76). Typical readouts of these models include genomic changes in DRGs, axon and axon terminal (intraepidermal nerve fiber), electrophysiological, and behavioral changes. While CIPN affects all sensory modalities, these animal models focus on investigating the changes in nociception and measure pain phenotypes in response to noxious stimuli of different modalities: mechanical, thermal, and cold stimuli (76). Although rodent studies significantly facilitated our understanding of CIPN pathology, more studies demonstrated molecular differences between human and rodent DRGs (77), which is predicted as a roadblock to effective translation. Accordingly, efforts are made to understand how insights gained from rodent models can be effectively translated into humans. More recently, human models utilizing induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) approaches (78–80) were also used in the field, and limited non-human primate models (73) have been used to validate findings from small animal models.

Non-mammalian in vivo models, Drosophila, zebrafish, and C. elegans provide advantages in genetics and live monitoring of neuron phenotypes and the surrounding environment (75). While sensory neurons in non-mammalian models have several differences from mammalian counterparts, these models are advantageous and complementary to mammalian models. Several studies from Drosophila and zebrafish have been validated in rodent models [reviewed in (75)], however, their efficacies have not yet been tested in humans. Considering the knowledge gaps in CIPN pathology on how cellular environment (both cancer and cancer-free) influence neuronal health, these simple models may serve as effective tools for advancing our understanding of CIPN pathology and identifying candidates for CIPN treatment.

For in vitro studies, rodent primary sensory neurons (embryonic and adult), immortalized sensory neurons, non-neuronal cells, and cells and tissues from other non-conventional models, including Aplysia and squid, were used (15, 81, 82). To address the limitation of in vitro approaches, several studies deployed co-culture models to investigate inter-cellular mechanisms in CIPN (83–86). Additionally, studies that used compartment culture extended our understanding of an axon-specific vulnerability of the sensory neurons. Several in vitro studies using compartmentalized cultures demonstrated that axon terminals, rather than cell bodies, are sensitive to paclitaxel toxicity (45, 87, 88). These studies consistently showed a reduction in axon length only after the paclitaxel addition in the axon compartment, highlighting that paclitaxel induces axon degeneration through local mechanisms in the sensory neuron's peripheral environment. A combination of co-culture and compartment culture approaches may be useful in future studies to simulate cellular interactions of axon terminals and non-neuronal cells.

Drosophila Models of CIPN

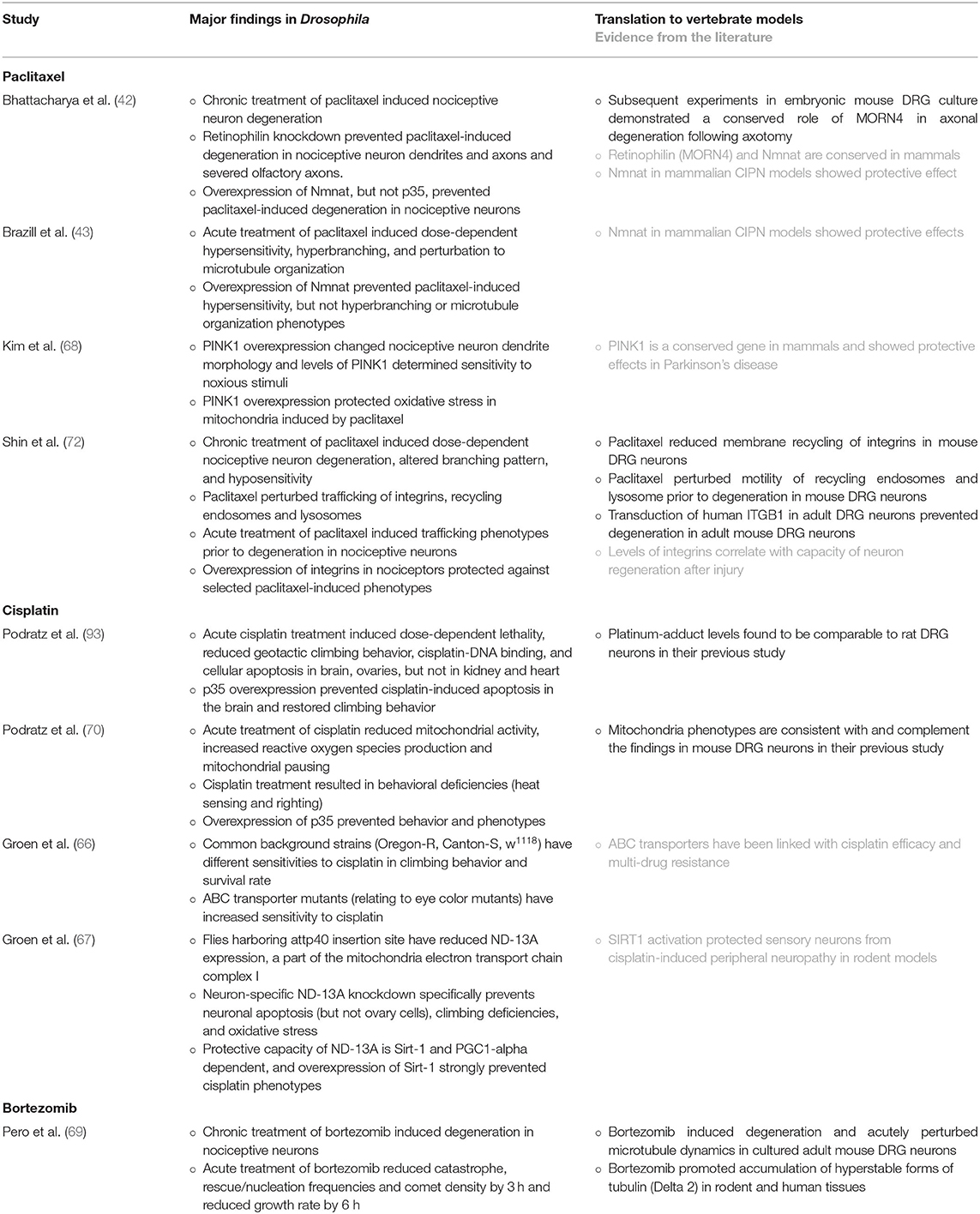

There are only handful of Drosophila CIPN studies so far, however, the use of chemotherapeutics in Drosophila models for studying cancer has been well established in the field (89–91), with over 400 articles in PubMed at the time of writing this review. A PubMed search on “Drosophila AND CIPN” resulted in 9 articles, including seven primary articles. The second search using “Drosophila AND neuron AND (paclitaxel OR vincristine OR bortezomib OR cisplatin)” resulted in 9 additional articles. Three of these studies from the second search were relevant (70, 71, 92) and included in this review. An additional manual search revealed another article in cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy (93). Overall, Drosophila CIPN studies focused on three common chemotherapeutics, paclitaxel (42, 43, 72, 94), cisplatin (66, 67, 70, 71, 92), and bortezomib (69). Three of these studies (42, 69, 72) used Drosophila as a part of multi-model studies. Other studies have discussed conserved mechanisms shown in other mammalian CIPN studies in the literature (43, 66–68, 70, 71) (Table 1).

Sensory Neurons and Their Extracellular Environment in Drosophila

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) of larval Drosophila consists of somatosensory neurons of different modalities, stereotypically localized along the basal surface of the epidermis (95). The PNS of Drosophila is organized segmentally and sensory and motor neurons are organized in a stereotyped pattern. Sensory neurons are categorized into two groups, type I neurons with ciliated monopolar dendrites and type II neurons with multiple dendrites. Multiple dendritic (md) neurons are further categorized into three subtypes: tracheal dendrite (md-td), bipolar dendrite (md-bd), and dendritic arborization (md-da) neurons (96, 97). Md-da neurons display class-specific morphologies in their innervation along the body wall (97). Classes I-IV md-da neurons have different sensory modalities, proprioception (cI), touch (II, III), cold nociception (III), mechanical and thermal nociception (IV) (98–101). Of particular interest to CIPN studies are class IV nociceptive neurons, highly branched somatosensory neurons that innervate the epidermis, running between the muscles of the body wall and the epithelium using intricate space-filling arbors (97, 98). Major differences between Drosophila and mammalian sensory neurons include location of cell bodies (43) and microtubule orientations in dendrites, which are sensory neuron terminals in the periphery, analogous to vertebrate sensory afferents in the dermal and epidermal layers (102).

Despite these differences, Drosophila nociceptive neurons share key features with their mammalian counterparts, such as naked nerve endings contacting the epidermis and ongoing terminal and substrate remodeling in mature stages (98, 103–107). Similarly, the Drosophila immune system is comprised of an evolutionarily conserved innate immune system with specialized immune cells analogous to vertebrate macrophages (108–111). They likewise surround nociceptive neurons and become robustly activated following wasp attack and injury (108–110, 112, 113), homologous to skin-residing macrophages, which actively patrol local nerves and are required for nerve regeneration after injury (114). Thus, Drosophila may serve as an effective system to unravel the complex cellular and molecular basis of interactions between nociceptive neurons and extrinsic factors and the relevance to sensory pathology.

Drosophila as a Model to Study Peripheral Neuropathy

Human genes related to pain, TRPV, TRPA1, TRPM2, PIEZO1, PIEZO2, and ASIC3, are conserved in Drosophila (115, 116). Many Drosophila studies have significantly contributed to our understanding of pain and neurodegeneration. For example, Drosophila models identified the first transient receptor potential (Trp) channel (117) and enabled discovery of conserved axon death pathway involving Toll receptor adaptor Sarm (sterile α/Armadillo/Toll-Interleukin receptor homology domain protein) (118), a key candidate for CIPN prevention (44–47).

The advantages of Drosophila melanogaster models include genetic amenability, a shorter life cycle, and a large number of offspring (119). Widely available genetic approaches that specifically mark and manipulate nociceptive neurons are powerful tools for understanding cellular and intracellular changes (120). For example, the promoter region isolated from pickpocket (ppk) gene, which encodes a degenerin/epithelial sodium channel subunit, is often used for specific labeling and manipulation of class IV neurons (121, 122). Using binary systems such as Gal4-UAS and LexA-LexAOp systems (123), potential genes of interest can be either knocked down or overexpressed using readily available transgenic lines. Because 60–75 % of human disease-related genes are predicted to have orthologs in Drosophila (124, 125), abundant Drosophila toolkits provide effective approaches to study genes that are responsible for nociception and peripheral neuropathy.

The functional role of class IV neurons was first demonstrated by identification of TrpA1 homologue painless (126) and subsequent demonstration of nocifensive behavior in response to noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli (98). Damage to these nociceptors is linked to sensory dysfunction based on nociceptive behavioral studies in Drosophila models and corresponding changes in unmyelinated nociceptive sensory endings in response to chemotherapy treatment (42, 43, 68, 72). Behavioral nociceptive assays conducted in the field typically evaluate nocifensive behavior, analogous to stimulus-evoked responses in rodent models using Von Frey test (mechanical nociception) or the Hargreaves test (thermal nociception). In response to noxious thermal or mechanical stimuli, Drosophila larvae show a stereotyped behavioral response including C shape bending followed by lateral rolling behavior and fast crawling (98, 126). Other behavioral studies have assessed sensory-motor circuit function by evaluating geotactic climbing behavior and righting behavior (the ability to flip back onto the ventral side following placement on the dorsal side) (70, 71, 93).

CIPN Study Design and Readouts in Drosophila Models

Drosophila CIPN models found similar degenerative phenotypes to mammalian models in response to treatments with the commonly prescribed drug paclitaxel and bortezomib (42, 69, 72). In addition, Drosophila models of CIPN also demonstrate comparable pathological progression in terms of the dose and duration dependence of hyposensitivity (72) or hypersensitivity (43, 70) in response to noxious thermal stimuli (43, 70, 72).

Studies investigating CIPN in Drosophila have so far mainly focused on understanding chemotherapy-induced changes of neurons in vivo. This includes investigating morphological changes, chemotherapeutic-induced intracellular phenotypes in mitochondria and endosomes, and, in some studies, correlating these with behavioral changes (42, 43, 68–72). Leveraging a deep understanding of nociceptive neuron morphology in Drosophila, studies have characterized specific changes in branch pattern, dynamics, and degeneration (43, 72), adding to our understanding of mechanisms of neuronal changes in CIPN pathology. Both chronic (42, 69, 72) and acute treatments (43, 66, 68–72) have been conducted to assess short and long-term toxicity of chemotherapeutics. As shown in other mammalian studies, Drosophila CIPN models also showed dose-dependent phenotypes in nociceptive behavior and sensory neuron morphology (43, 66, 70–72).

Due to transparent body that allows live imaging and extensive understanding of nociceptive neuron development, maintenance, and a stereotyped nocifensive behavior, Drosophila larval sensory neurons have been a preferred CIPN model over adult flies in the field. Therefore, potential target genes and pathways identified in the model should be validated in adult models, such as adult mouse in vitro and in vivo models. In Drosophila models, chemotherapeutic agents had been fed on an ad libitum basis, an experimental design that conforms with constant feeding behavior (127) at larval stage and was also proved to be effective in adult models. While physiological concentrations of chemotherapeutics are unknown, studies have consistently reported dose-dependent phenotypes suggesting that the drug delivery is effective. Future studies quantifying tissue concentration of chemotherapeutics in these feeding paradigms will further facilitate translation of Drosophila studies.

Potential CIPN Mechanisms Identified in Drosophila Models

Paclitaxel-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Models

Paclitaxel is one of the most commonly used chemotherapeutic agents, frequently used to treat solid tumors, including breast, ovarian, lung, gastric, and head and neck cancers (15, 128, 129). Paclitaxel binds to β-tubulin in the tubulin polymer along the lumen of microtubules, suppressing dynamics and promoting tubulin polymerization (130–132). Up to 80% of patients treated with paclitaxel develop peripheral neuropathy and a subset of these patients have neuropathic symptoms in the long term (133). Mechanisms of CIPN arising from paclitaxel have been extensively studied, however, unifying pathological mechanisms are debatable, and definitive answers to PIPN mechanisms that can be translated into reliable methods for clinical interventions are unavailable.

The paclitaxel-induced neurotoxicity model in Drosophila started from the work of Bhattacharya and colleagues (42). The study used paclitaxel treatment as a method for neuronal injury and found that paclitaxel treatment results in axonal swelling and fragmentation without apoptosis. This study hypothesized that loss-of-function of a gene in the axonal degeneration pathway would delay or prevent degeneration of neurons following an injury and conducted RNAi screen. The screen consisted of 490 genes with enzymatic functions and known to function in the nervous system using pan-neuronal driver. Consequently, the screen identified MORN (membrane occupation and recognition nexus), encoded by retinophilin, a gene previously reported to function in the retina and store-operated calcium release leading to phagocytosis in macrophages in Drosophila (134–136). Additionally, they discovered that paclitaxel-induced degeneration of dendrites and axons could be prevented by overexpression of Nmnat (nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase) or the knockdown of MAP3K Wallenda, orthologous to DLK in mammals. The study further showed that the knockdown of mouse ortholog of retinophilin, MORN4, prevented axonal degeneration following axotomy of embryonic mouse DRG neurons, suggesting conservation of protective capacity in mammalian system. This study highlights the utility of Drosophila model as an in vivo screening system in identifying conserved genes that may harbor therapeutic potential for CIPN treatment.

Severe degeneration of distal and proximal axons shown in the above study (42) likely represent late pathological stages of CIPN. Another study by Brazill and colleagues complemented the initial paclitaxel study by modifying paclitaxel feeding regimen including lower dosages (10–30 μM) and shorter treatment time (up to 48 h) (43). This approach enabled characterizing early pathological changes by paclitaxel. The authors observed an increased density in nerve endings, instead of severe degeneration following paclitaxel treatment. The branch phenotypes were correlated with decreased dynamics of nerve endings, particularly resulting in inhibition of dendrite terminal retraction. The study further identified disrupted neuron-specific microtubule associated proteins, MAP1B/Futsch, providing a potential molecular mechanism underlying changed dynamics of dendrite terminals. These morphological changes were accompanied by hypersensitivity to thermal noxious stimuli in a dose-dependent manner. This study further demonstrated that overexpression of the neuronal maintenance factor, Nmnat, mitigates hypersensitivity without affecting hyperbraching or Futsch disruption (43). This may indicate uncoupling of “form and function” whereby function is selectively mediated by NMNAT (43). Alternatively, it could indicate a partial protection of neuropathic phenotype by Nmnat overexpression and may require further behavioral testing of additional types of sensory dysfunction such as allodynia to delineate underlying mechanism.

Another study investigated the therapeutic potential of a conserved gene involved in mitochondria quality control in a Drosophila CIPN model (68). A mitochondrial Serine/Threonine kinase, PINK1 (Phosphatase and tensin homologue-induced putative kinase 1), has been shown as a molecular sensor for mitochondrial damage and shown to be involved in key steps in mitochondria quality control (137, 138). PINK1 mutations cause early-onset autosomal recessive Parkinson's disease, whereas its expression protects against various toxic insults in models of Parkinson's disease (137). Kim and colleagues (68) found that ectopic PINK1 expression prevented an increase in mitophagy-related oxidative stress in Drosophila class IV neurons upon paclitaxel treatment. In parallel, PINK1 levels determined the morphology and thermal sensitivity of cIV neurons, suggesting that PINK1 may be a critical component of cIV neuron development and maintenance. As knockdown of PINK1 specifically reduced branching and thermal sensitivity but not the baseline levels of mitophagy, this finding suggests that PINK1 has dual roles in nociceptive neuron health and maintenance.

A recent study reported cellular mechanisms of paclitaxel toxicity mediated by endocytic recycling pathway and identified cell surface receptors integrins as a conserved gene that prevents CIPN pathology (72). This study employed a complementary approach combining two established CIPN models, Drosophila sensory neurons and primary DRG mouse neuron cultures. The authors found that chronic treatment of Drosophila larvae with paclitaxel (10–20 μM) resulted in degeneration and morphological alteration of the branching patterns of nociceptive neurons. As the altered branching patterns resembled phenotypes when neuron-substrate interactions are perturbed, this study further investigated the potential protective capacity of integrins, key cell surface receptors known to maintain interactions between neurons and the ECM (106, 107). Upon overexpression of integrins in nociceptive neurons, both degeneration and branching pattern phenotypes were significantly reduced. These morphological changes corresponded to reduced nociceptive responses to noxious thermal stimuli, which was also prevented by cell-specific overexpression of integrins. Given the critical role of integrins in development and maintenance mediated through interactions with the extracellular environment (106, 107), this strongly points to the importance of neuron-substrate relationships in neuronal health and function in CIPN. Furthermore, this study proposed endosomal changes underlying paclitaxel-induced changes in nociceptive neurons. Paclitaxel treatment reduced endosome-mediated trafficking of integrins. Super-resolution and live imaging of animals with acute and chronic paclitaxel treatment revealed that impaired recycling pathways involved in integrin membrane trafficking preceded morphological degeneration. Using mouse DRG neurons, the study further validated that endocytic changes precede axon degeneration and that integrin overexpression of human integrin beta-subunit 1 (a major beta subunit of integrin heterodimers in mammals) effectively prevented degeneration following paclitaxel treatment. Because surface expression of integrins is required in neuronal interactions with epidermis and the ECM, these results highlight the importance of neuron-substrate interaction in CIPN pathology that is controlled by endocytic recycling pathways of cell surface proteins.

Cisplatin-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Models

Cisplatin is a platinum-based drug that binds to mitochondrial and nuclear DNA and creates intra-strand cross-links forming platinum-DNA adducts. Accumulation of these adducts causes DNA damage and leads to apoptosis. Similar to paclitaxel, it is used to treat solid cancers such as lung, breast, ovarian, and colon cancers; however, unlike paclitaxel, its effect is not cell cycle-specific. Cisplatin is notably toxic to neurons (17). Cisplatin can adversely affect sensory nervous system, by causing apoptosis of somatosensory neurons and hair cells, leading to permanent sensory loss (17) and ototoxicity (92, 139).

A series of studies from the Windebank lab have pioneered Drosophila larval and adult models of cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy (66, 67, 70, 71, 93). The initial study in the lab used adult fly model to study the effect of cisplatin in neurons in the central nervous system and geotactic climbing behavior (93). The authors found that acute feeding of cisplatin (10–200 μg/mL) dose-dependently caused lethality and climbing defects, which was prevented by overexpression of p35, a pan-caspase inhibitor and anti-apoptotic protein. The group further demonstrated that cisplatin also causes similar toxicity in the larval model (70). Larval Drosophila fed with 10 and 25 μg/mL cisplatin showed a deficit in both motor and sensory behaviors: hypersensitivity to heat and attenuated motor-proprioceptive behavior. P35 overexpression also ameliorated these larval behavior phenotypes, suggesting that p35 may be an attractive target for cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy. This investigation further identified cisplatin-induced mitochondrial phenotypes in Drosophila motor neurons, following from their earlier study in a rodent CIPN model that demonstrated cisplatin-induced mitochondrial damage in DRG neurons (140). Using Drosophila as an in vivo model to study mitochondrial function and axon transport, the study demonstrated specific mitochondrial defects by cisplatin treatment: cisplatin reduced mitochondrial activity and mitochondrial membrane potential, whereas it increased reactive oxygen species production and mitochondrial pausing (70). As cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy is predominantly sensory, future studies investigating sensory neuron phenotypes in Drosophila would provide additional insights into pathological mechanisms of cisplatin-induced toxicity.

Susceptibility of different strains to platinum-based drugs have been reported in rodent models, which may explain patient-specific susceptibility to these drugs (141, 142). To provide underlying mechanisms, two additional studies utilized different Drosophila strains to examine and investigate potential genetic markers for CIPN susceptibility (66, 67). These studies identified ABC transporter (linked with a common control Drosophila strain w1118) and ND-13A, a component of the mitochondria electron transport chain complex I (linked with a transposable element insertion site attp40 in some Drosophila transgenic lines). Consistent with the results from rodent studies, these studies provide critical information for effective experimental designs for CIPN studies and whether these strains confer different susceptibilities to other chemotherapeutic drugs should be investigated in future. Furthermore, these studies highlight the utility of Drosophila CIPN models to uncover novel genes responsible for patient susceptibility and treatment target pathways in CIPN.

Bortezomib-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Model

Bortezomib is a type of proteosome inhibitor used routinely to treat multiple myeloma, mantle-cell lymphoma, and amyloidosis. Inhibition of proteosome activity leads to the misfolded protein accumulation and apoptosis of cancer cells (143). Up to 80% of newly-diagnosed patients with bortezomib treatment develop peripheral neuropathy, however, in the majority of cases, Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy can be resolved by drug cessation or dose reduction (144).

Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy mechanisms have not yet been extensively studied in Drosophila; however, the Drosophila model was employed in a multi-model study consisting of mouse, rat, zebrafish, Drosophila, and human (69). Consistent with other models in the study, Drosophila larvae fed with bortezomib showed degeneration of nociceptive neuron terminals after chronic treatment and perturbation of microtubule dynamics after acute treatment. As an in vivo model amenable for live imaging in an intact animal, the Drosophila model provided a complementary result to in vitro rodent models and human tissues, corroborating the underlying mechanisms of bortezomib toxicity via microtubule stabilization (69).

Limitations and Future Potentials of Drosophila CIPN Models

Although not yet widely used, studies using Drosophila CIPN models proved to be relevant and useful in discovering potential treatment targets and underlying pathological mechanisms. Like rodent models, Drosophila CIPN models have so far primarily focused on neuron intrinsic mechanisms. Drosophila models provide established platforms to investigate neuronal interactions with their extracellular environment, particularly with epidermal cells and the ECM. Given the importance of neuronal interactions with epidermal keratinocytes in nociception, the Drosophila model will provide a simple in vivo model to inform how these inter-cellular interactions contribute to pathological progression of CIPN. Another area of interest may be combining the wealth of cancer studies in Drosophila into CIPN investigation. While cancer-bearing models would provide highly relevant microenvironment for studying CIPN mechanisms and validate safety and efficacy of CIPN treatment targets, it is challenging to generate vertebrate models that combine cancer and pain models. As an invertebrate system, Drosophila cancer models may provide an opportunity to investigate CIPN mechanisms in a relevant cancer environment. As shown in several studies in the field, future Drosophila CIPN studies should be designed in consideration with future or parallel rodent and human studies, preferably as a part of multi-model study to effectively demonstrate conserved mechanisms for CIPN pathology and contribute to prevention and treatment of CIPN.

Possibilities of Utilizing Human-Engineered Skin Models in Understanding CIPN

Although animal models have provided many valuable insights into understanding CIPN pathology, CIPN models that capture human genetics and physiology would add significant advantages for clinical translation. There is no effective human model for studying CIPN to investigate neuropathic mechanisms in the context of their local environment. Utilizing human-engineered skin models may fill the knowledge gap to validate and further examine CIPN pathological mechanisms.

Introduction to Human-Engineered Skin Models

The field of skin bioengineering has advanced significantly over the past several decades, offering physiologically-relevant models of human skin in different cellular and structural complexities (145). These advanced tissue-engineered skin (TES) models represent the 3D skin microenvironment and cellular diversity of human skin more closely compared to 2D cell cultures while still offering a large variety of molecular and cellular readouts. TES models are composed of different skin cell types self-assembled or reconstructed within a 3D hydrogel, typically collagen type I. Given that sensory terminals innervate the skin, CIPN research may significantly benefit from bioengineered human skin that emulates its native environment. The bioengineered 3D innervated skin models are expected to provide insights about the human relevance of findings obtained using animal models or simplified 2D models. Furthermore, through the capability of adjusting the complexity of bioengineered skin, this approach will provide an efficient model system to dissect the interactions of sensory neurons with different skin cell types.

There is a variety of commercially available full-thickness 3D skin models, which are typically composed of dermal fibroblasts and terminally differentiated layers of keratinocytes. The human skin is much more complex with more than 50 different cell types and several appendages, such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands. While our knowledge of the interactions between nociceptor sensory endings and the diverse cellular makeup in skin is limited, we are starting to understand interactions between the keratinocytes and nociceptive neurons (146, 147). For example, recent work suggested a determining role of specific epidermal cell populations on sensory neuron patterning and axonal growth. A recent study showed that a KRT17-positive subpopulation of keratinocytes residing in the follicular and interfollicular epidermis is required and sufficient for touch-sensitive sensory neuron patterning in mouse touch-domes (148). Arborization of neuronal axons is also mediated by various signal inputs in the extracellular space, including positive and negative ECM cues in the skin. Specialized ECM proteins play pivotal roles in axonal branching and patterning (149). For instance, EGFL6, a specialized ECM protein deposited by the epidermal stem cells in hair follicles influences the terminal anatomy of mechanosensory endings in the hair follicles (150). A growing number of studies show the interactions of sensory neurons with various skin cell types, such as endothelial cells, immune cells, and Schwann cells, during skin regeneration and inflammation. However, how skin cells play a role in the pathological progression of CIPN is mostly unknown. Therefore, the recapitulation of the cellular diversity in TES models is important to develop a physiologically-relevant CIPN model and understand pain-related sensory function.

Since Bell et al. introduced the first full-thickness TES in 1981 (151) with dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes, there has been a substantial effort in incorporating other dermal and epidermal cell types. These include blood (152) and lymphatic endothelial cells (153) forming vascular networks, melanocytes producing pigmentation (154), and adipocytes generating the adipose-containing hypodermis compartment (155). In addition, there has been a significant interest in adding different immune cell types, such as macrophages, Langerhan cells, disease-specific effector T cells, dendritic cells, and neutrophils, into TES to generate immune-competent skin models (156). Moreover, skin appendages, i.e., hair follicles (157) and sweat glands (158), have recently been successfully integrated into TES, further increasing the functional and structural relevance of these models.

The current TES models are based on a reverse-engineering approach. Each primary or iPSC-derived cell type is expanded in vitro separately and then reconstructed in 3D for spontaneous self-organization of cells or assisted organization using engineered patterns to recapitulate cell-cell interactions. Therefore, it becomes technically challenging to include more and more skin cell types and components to eventually achieve an in vivo level complexity. However, in their current form, where several types of skin cells are included (fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells) together with nociceptors, they can still be invaluable models to dissect the interactions of nociceptors with multiple cell types in the context of CIPN and skin microenvironment. Given the spatial relationship between nociceptive neurons and the epidermis, such models are expected to serve as an effective platform for studying the neuron-ECM-epidermis interactions in a 3D environment with conserved physiological relevance to human skin.

Recent iPSC-derived skin organoids may address some of the challenges in TES regarding cellular diversity (159). The skin organoids approach mimics skin morphogenesis and simultaneously generates many skin cell lineages, including melanocytes, adipocytes, and hair follicles. In addition, it can generate specialized cell types, such as Merkel cells of the touch-dome, which cannot be incorporated into reconstructed TES models due to the difficulties of expanding these cells in vitro. Moreover, the presence of neurons and sensory neurons was demonstrated in skin organoids which may enable studying skin mechanosensation and pain. However, it is not yet known which subpopulations of sensory neurons exist in these organoids or whether they are mature enough to represent skin innervation and function. Nevertheless, despite its current limitations, the skin organoid is an exciting new approach that has the potential to be integrated into CIPN research in the future.

Innervated TES Models

The proof-of-concept for incorporating sensory neurons into 3D skin has been demonstrated by several studies. Earlier studies integrated rat neurons isolated from dorsal root ganglia (DRG) into explanted human skin in a co-culture system (160). Later studies successfully innervated tissue-engineered skin with sensory neurons isolated from the mouse, rat, or porcine DRG or human iPSC-derived sensory neurons (161).

Roggenkamp et al. developed several 3D co-culture models with animal DRG sensory neurons and human fibroblast and keratinocytes from both healthy and diseased donors. In an early study (162), they seeded porcine DRG neurons embedded in collagen type I gel on a polyester/propylene matrix scaffold, and then added human TES composed of healthy dermal FBs and KCs. After 12 days of culture, neurites were observable in the dermal component with thin nerve endings ascending toward the epidermis resembling innervation in vivo. Using similar co-culture setup with skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes isolated from individuals with type II diabetes, the same group showed diabetic TES reduces porcine neurite outgrowth due to decreased levels of neurotrophic factors, illustrating the hypo-innervation in type II diabetes (163). In another disease model, they further showed that skin cells from atopic dermatitis patients promote neurite outgrowth in TES compared to healthy skin cells (164). These models demonstrated the capability to induce neurite outgrowth of sensory neurons in TES as a readout to assess disease-specific innervation mechanisms.

Another group induced mouse DRG ingrowth in TES and further tested the sensing functionality of the innervated model through topical application of capsaicin. The DRG neurons responded to capsaicin treatment by changes in Ca2+ influx. This study is significant in terms of showing neuronal functionality in TES (165).

A series of important papers from François Berthod's group broadened our understanding of the mechanism underlying the innervation of TES. In an early 2003 study (166), they used a collagen sponge populated with dermal fibroblasts and endothelial cells and highlighted that NGF is critical for neurite growth but not for the survival of mouse DRG neurons. In a separate study, they included mouse Schwann cells isolated into TES and showed that Schwann cells enhance the innervation process and can myelinate the DRG neurons in TES (167). This study is particularly important to show the proof-of-concept for sensory neuron myelination, a determining factor in achieving sensory function in TES. In two subsequent studies, the group implemented their approach, with slight modifications in the TES model, for aging (168) and wound healing applications (169). Their studies highlighted the importance of nerve-skin interactions demonstrating more efficient wound closure in the presence of sensory neurons through secretion of neuropeptide substance P.

The sourcing of human-derived DRGs has been a problem and recently been partially addressed by leveraging iPSC technology. By differentiating iPSCs into sensory neurons and Schwann cells, a fully human innervated engineered skin construct was made (170). After 18 days of co-culture with the skin construct, iPSC-derived neurons formed a network of neurites reaching up to the epidermis, but strikingly only when combined with Schwann cells. These neurons released neuropeptides upon stimulation, demonstrating some level of functionality. Another recent study differentiated itch sensory neuron-like cells (ISNLCs) from iPSCs and reported that these cells displayed action potentials in response to itch-specific stimuli (171). ISNLCs expressed receptors for cytokines IL-4/IL-13, which contributed to their activation. They subsequently integrated the ISNLCs into TES as a proof of principle.

As an alternative to the iPSC-derived neurons, another group utilized human-induced neural stem cells (hiNSCs) directly reprogrammed from dermal fibroblasts to innervate their skin constructs (172). The model includes a hypodermis containing patient-derived lipoaspirates and immune cells. The epidermal and dermal components are made with a novel collagen-silk gel that is then placed on top of the hypodermis. The primary focus of this study was to generate a TES that could recapitulate the neuro-immuno-cutaneous system. They found patient-specific variations in the release of cytokines in the presence of patient-derived adipose tissue, highlighting the importance of patient-specific modeling. The study did not include morphological validation of innervation and neuron organization. Although hiNSCs expressed several sensory neuron markers, the sensory neuron-specific identity and function of these cells are yet to be determined.

Co-culturing neurons in TES has also been shown to be influential on epidermal cells. Epidermal thickness and density have been reported to be higher, and the apoptosis of keratinocytes to be lower in innervated TES (160). Neurons induced keratinocyte proliferation and increased epidermal thickness via a neuropeptide, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) (162). Likewise, keratinocytes and fibroblasts were shown to regulate skin innervation via neurotrophic factors, NGF (170). These complex reciprocal interactions highlight the importance of incorporating innervation in TES to study skin physiology and pathology. Notably, such neuropeptides and neurotrophic factors, including CGRP and NGF, are closely correlated with CIPN pathology, yet how they contribute to neuron-skin crosstalk is largely unknown. These innervated models provide platforms to study how neuron-skin interactions could drive CIPN pathology. Emulating key aspects of a neuron's native environment, these models have the potential to advance in vitro drug screening models for future CIPN studies.

Limitations and Future Potentials of TES for CIPN Studies

All TES models reported so far use similar innervation approaches where the vertical neurite growth and branching in the dermis were stimulated by adding growth factors into the culture medium or inclusion of other cells, such as Schwann cells. This process, unfortunately, results in a spontaneous and uncontrolled innervation. To achieve a physiologically relevant and truly functional innervated TES model, it is imperative to control the level and type of innervation. Given layer-specific targeting of sensory neurons of different modalities in the epidermis and dermis, it is also important to guide these nerves to their final end-organ, e.g., different epidermal layers vs. papillary dermis. Moreover, most of the studies discussed above do not know which subtypes of sensory neurons innervate the skin, and their function still requires validation as the innervation does not necessarily lead to sensation. In the future, with advanced biofabrication techniques such as 3D-bioprinting and novel and tunable biomaterials, it may be possible to spatially control and guide the innervation process in TES to achieve function. There is also a need to produce robust differentiation protocols to derive and characterize each specific subpopulation of sensory neurons from iPSCs to achieve a physiologically relevant model of skin sensation.

Although the iPSC-derived skin organoids approach addresses the issue of cellular diversity in TES, several issues remain, including spontaneous differentiation and cyst-like organization of cells, leading to partial anatomical relevance, e.g., inside-out morphology where the epidermis is inaccessible as it is located in the interior of the organoid. In addition, the dermis of these organoids is neural-crest derived and thus mimics the craniofacial skin, as opposed to the other sites of the human dermis, which are mesoderm-derived. With the emerging engineering approaches in the organoid field, such as cell and ECM micropatterning, some of these limitations may soon be addressed. Future studies should include validation of the level of maturation of the sensory neurons in these embryonic models to serve as a model for CIPN.

Conclusion

To advance our understanding of CIPN pathology that could lead to effective prevention and treatment options in the clinic, future studies should consider characterizing neuronal changes in the context of their local environment. Given that surrounding non-neuronal cells are dynamically maintained and actively crosstalk with sensory neurons, experimental platforms that recapitulate neurons' local environment and could monitor real-time changes would be ideal. Currently, no single experimental model could fulfill such conditions. Yet, a combination of several models could provide significant insights and robust validation of pathological mechanisms that often fall short by using a single model approach. Together with existing rodent models of CIPN, simple in vivo animal models and simplified human 3D models reviewed here could provide complementary advantages that allow characterization of inter-cellular and cell-type-specific mechanisms of CIPN pathology with clear functional readouts. These models also have the potential to simulate the cancer microenvironment that would further validate the efficacy and safety of potential targets for CIPN prevention and treatment.

Author Contributions

GS conceived the manuscript, drafted the first outline of the paper, wrote sections Introduction, Experimental Approaches to Study CIPN Mechanisms, Drosophila Models of CIPN (Sensory Neurons and Their Extracellular Environment in Drosophila, Drosophila as a Model to Study Peripheral Neuropathy, and CIPN Study Design and Readouts in Drosophila Models), and Conclusion, and edited and revised all sections in the manuscript. HA wrote section Possibilities of Utilizing Human-Engineered Skin Models in Understanding CIPN. MS wrote the draft of section Drosophila Models of CIPN (Potential CIPN Mechanisms Identified in Drosophila Models) and assisted with the PubMed search. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

GS was supported by Thompson Family Foundation Initiative for Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy and Sensory Neuroscience at Columbia University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Luke Hammond, Wesley Grueber, and Abby Wood for constructive feedback on this manuscript.

References

1. Favoriti P, Carbone G, Greco M, Pirozzi F, Pirozzi RE, Corcione F. Worldwide burden of colorectal cancer: a review. Updates Surg. (2016) 68:7–11. doi: 10.1007/s13304-016-0359-y

2. Jemal A, Center MM. DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends Cancer. Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2010) 19:1893–907. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0437

3. Ledermann JA. First-line treatment of ovarian cancer: questions and controversies to address. Ther Adv Med Oncol. (2018) 10:1758835918768232. doi: 10.1177/1758835918768232

4. Saini KS, Twelves C. Determining lines of therapy in patients with solid cancers: a proposed new systematic and comprehensive framework. Br J Cancer. (2021) 125:155–63. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01319-8

5. Sculier JP, Moro-Sibilot D. First- and second-line therapy for advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir J. (2009) 33:915–30. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00132008

6. Verma S, Clemons M. First-line treatment options for patients with HER-2 negative metastatic breast cancer: the impact of modern adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncologist. (2007) 12:785–97. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-785

7. Pike CT, Birnbaum HG, Muehlenbein CE, Pohl GM, Natale RB. Costs and workloss burden of patients with chemotherapy-associated peripheral neuropathy in breast ovarian head and neck and nonsmall cell lung cancer. Chemother Res Pract. (2012) 2012:913848. doi: 10.1155/2012/913848

8. Cavaletti G, Marmiroli P. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurol. (2010) 6:657–66. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.160

9. Chua KC, Kroetz DL. Genetic advances uncover mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2017) 101:450–2. doi: 10.1002/cpt.590

10. Lisse TS, Middleton LJ, Pellegrini AD, Martin PB, Spaulding EL, Lopes O. Paclitaxel-induced epithelial damage and ectopic MMP-13 expression promotes neurotoxicity in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:E2189–98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525096113

11. Ma J, Kavelaars A, Dougherty PM, Heijnen CJ. Beyond symptomatic relief for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: targeting the source. Cancer. (2018) 124:2289–98. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31248

12. Molassiotis A, Cheng HL, Lopez V, Au JSK, Chan A, Bandla A. Are we mis-estimating chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy? Analysis of assessment methodologies from a prospective, multinational, longitudinal cohort study of patients receiving neurotoxic chemotherapy BMC Cancer. (2019) 19:132. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5302-4

13. Seretny M, Currie GL, Sena ES, Ramnarine S, Grant R., MacLeod MR, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and predictors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. (2014) 155:2461–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.020

14. Mizrahi LiT, Goldstein D, Kiernan D, Park MC. Chemotherapy and peripheral neuropathy. Neurol Sci. (2021) 42:4109–21. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05576-6

15. Gornstein E, Schwarz TL. Paradox of paclitaxel neurotoxicity: Mechanisms and unanswered questions. Neuropharmacology. (2013) 2014:175–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.016

16. Loprinzi CL, Lacchetti C, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G, Chauhan C, Hertz DL. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:3325–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01399

17. Ibrahim EY. Ehrlich BE of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A review of recent findings. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2020) 145:102831. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.102831

18. Starobova H, Vetter I. Pathophysiology of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Front Mol Neurosci. (2017) 10:174. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00174

19. Lee JJ, Swain SM. Peripheral neuropathy induced by microtubule-stabilizing agents. J Clin Oncol. (2006) 24:1633–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0543

20. Han Y, Smith MT. Pathobiology of cancer chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). Front Pharmacol. (2013) 4:156. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00156

21. Iuliis De, Taglieri F, Salerno L, Lanza G, Scarpa R, Taxane induced S. Neuropathy in patients affected by breast cancer: literature review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2015) 96:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.04.011

22. Ventzel L, Jensen AB, Jensen AR, Jensen TS, Finnerup NB. Chemotherapy-induced pain and neuropathy: a prospective study in patients treated with adjuvant oxaliplatin or docetaxel. Pain. (2016) 157:560–8. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000404

23. Majithia N, Temkin SM, Ruddy KJ, Beutler AS, Hershman DL, Loprinzi CL. National cancer institute-supported chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy trials: outcomes and lessons. Support Care Cancer. (2016) 24:1439–47. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-3063-4

24. Shah A, Hoffman EM, Mauermann ML, Loprinzi CL, Windebank AJ, Klein CJ. Incidence and disease burden of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in a population-based cohort. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2018) 89:636–41. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317215

25. Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, Lavoie Smith EM, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. (2014) 32:1941–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914

26. Smith EM, Pang H, Cirrincione C, Fleishman S, Paskett ED, Ahles T. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2013) 309:1359–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2813

27. Ferrari LF, Araldi D, Green PG, Levine JD. Marked sexual dimorphism in neuroendocrine mechanisms for the exacerbation of paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy by stress. Pain. (2020) 161:865–74. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001798

28. Hwang BY, Kim ES, Kim CH, Kwon JY, Kim HK. Gender differences in paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain behavior and analgesic response in rats. Korean J Anesthesiol. (2012) 62:66–72. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2012.62.1.66

29. Graan de, Elens AJ, Sprowl L, Sparreboom JA, Friberg A, van der Holt LEB, et al. CYP3A4*22 genotype and systemic exposure affect paclitaxel-induced neurotoxicity. Clin Cancer Res. (2013) 19:3316–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3786

30. Diaz PL, Furfari A, Wan BA, Lam H, Charames G, Drost L. Predictive biomarkers of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a review. Biomark Med. (2018) 12:907–16. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2017-0427

31. Park SB, Alberti P, Kolb NA, Gewandter JS, Schenone A, Argyriou AA. Overview and critical revision of clinical assessment tools in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. J Peripher Nerv Syst. (2019) 24 (Suppl. 2):S13–25.doi: 10.1111/jns.12333

32. Mangus LM, Rao DB, Ebenezer GJ. Intraepidermal nerve fiber analysis in human patients and animal models of peripheral neuropathy: a comparative review. Toxicol Pathol. (2020) 48:59–70. doi: 10.1177/0192623319855969

33. Joint Task Force of the “EFNS” and the PNS. European federation of neurological societies/peripheral nerve society guideline on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. Report of a joint task force of the european federation of neurological societies and the peripheral nerve society. J Peripher Nerv Syst. (2010) 15:79–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2010.00269.x

34. Koskinen MJ, Kautio AL, Haanpaa ML, Haapasalo HK, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Saarto T. Intraepidermal nerve fibre density in cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. (2011)31:4413–6.

35. Piscosquito G, Provitera V, Mozzillo S, Caporaso G, Borreca I, Stancanelli A. The analysis of epidermal nerve fibre spatial distribution improves the diagnostic yield of skin biopsy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. (2021) 47:210–7. doi: 10.1111/nan.12651

36. Schley M, Bayram A, Rukwied R, Dusch M, Konrad C, Benrath J. Skin innervation at different depths correlates with small fibre function but not with pain in neuropathic pain patients. Eur J Pain. (2012) 16:1414–25. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00157.x

37. Chen EI, Crew KD, Trivedi M, Awad D, Maurer M, Kalinsky K. Identifying Predictors of Taxane-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Using Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics Technology. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0145816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145816

38. Bennett GJ, Liu GK, Xiao WH, Jin HW, Siau C. Terminal arbor degeneration - a novel lesion produced by the antineoplastic agent paclitaxel. Eur J Neurosci. (2011) 33:1667–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07652

39. Fumagalli G, Monza L, Cavaletti G, Rigolio R, Meregalli C. Neuroinflammatory process involved in different preclinical models of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:626687. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.626687

40. Wang MS, Davis AA, Culver DG, Glass JD. WldS mice are resistant to paclitaxel (taxol) neuropathy. Ann Neurol. (2002) 52:442–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.10300

41. Argyriou AA, Koltzenburg M, Polychronopoulos P, Papapetropoulos S, Kalofonos HP. Peripheral nerve damage associated with administration of taxanes in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2008) 66:218–28. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.01.008

42. Bhattacharya MR, Gerdts J, Naylor SA, Royse EX, Ebstein SY, Sasaki Y, et al. model of toxic neuropathy in Drosophila reveals a role for MORN4 in promoting axonal degeneration. J Neurosci. (2012) 32:5054–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4951-11.2012

43. Brazill JM, Cruz B, Zhu Y, Zhai RG. Nmnat mitigates sensory dysfunction in a Drosophila model of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Dis Model Mech. (2018) 11:dmm032938. doi: 10.1242/dmm.032938

44. Bosanac T, Hughes RO, Engber T, Devraj R, Brearley A, Danker K. Pharmacological SARM1 inhibition protects axon structure and function in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Brain. (2021) 144:3226–38. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab184

45. Pazyra-Murphy LiY, Avizonis MF, de Sa Tavares Russo D, Tang M, Chen SCY et al. Sarm1 activation produces cADPR to increase intra-axonal Ca++ and promote axon degeneration in PIPN. J Cell Biol. 2022, 221. (2). doi: 10.1083/jcb.202106080

46. Geisler S, Doan RA, Strickland A, Huang X, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A. Prevention of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy by genetic deletion of SARM1 in mice. Brain. (2016) 139:3092–108. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww251

47. Gould SA, White M, Wilbrey AL, Por E, Coleman MP, Adalbert R. Protection against oxaliplatin-induced mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity in Sarm1 (-/-) mice. Exp Neurol. (2021) 338:113607. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113607

48. Kober KM, Olshen A, Conley YP, Schumacher M, Topp K, Smoot B. Expression of mitochondrial dysfunction-related genes and pathways in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in breast cancer survivors. Mol Pain. (2018) 14:1744806918816462. doi: 10.1177/1744806918816462

49. Kober KM, Schumacher M, Conley YP, Topp K, Mazor M, Hammer MJ. Signaling pathways and gene co-expression modules associated with cytoskeleton and axon morphology in breast cancer survivors with chronic paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Mol Pain. (2019) 15:1744806919878088. doi: 10.1177/1744806919878088

50. Yin LiY, Liu C, Nie B, Wang H, Zeng JD et al. Transcriptome profiling of long noncoding RNAs and mRNAs in spinal cord of a rat model of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy identifies potential mechanisms mediating neuroinflammation and pain. J Neuroinflammation. (2021) 18:48. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02098-y

51. Starobova H, Mueller A, Deuis JR, Carter DA, Vetter I. Inflammatory and neuropathic gene expression signatures of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy induced by vincristine, cisplatin, and oxaliplatin in C57BL/6J Mice. J Pain. (2020) 21:182–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.06.008

52. Megat S, Ray PR, Moy JK, Lou TF, Barragan-Iglesias P. Li Y. Nociceptor translational profiling reveals the ragulator-rag GTPase complex as a critical generator of neuropathic. Pain J Neurosci. (2019) 39:393–411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2661-18.2018

53. Huang ZZ, Liu LiD, Cui CC, Zhu Y, Zhang HQWW, et al. CX3CL1-mediated macrophage activation contributed to paclitaxel-induced DRG neuronal apoptosis and painful peripheral neuropathy. Brain Behav Immun. (2014) 40:155–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.03.014

54. Kiguchi N, Maeda T, Kobayashi Y, Kondo T, Ozaki M, Kishioka S. The critical role of invading peripheral macrophage-derived interleukin-6 in vincristine-induced mechanical allodynia in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. (2008) 592:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.07.008

55. Liu C, Luan S., OuYang H, Huang Z, Wu S, Ma C, et al. Upregulation of CCL2 via ATF3/c-Jun interaction mediated the bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy. Brain Behav Immun. (2016) 53:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.11.004

56. Liu CC, Lu N, Cui Y, Yang T, Zhao ZQ, Xin WJ. Prevention of paclitaxel-induced allodynia by minocycline: effect on loss of peripheral nerve fibers and infiltration of macrophages in rats. Mol Pain. (2010) 6:76. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-76

57. Makker PG, Duffy SS, Lees JG, Perera CJ, Tonkin RS, Butovsky O. Characterisation of Immune and Neuroinflammatory Changes Associated with Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0170814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170814

58. Meregalli C, Marjanovic I, Scali C, Monza L, Spinoni N, Galliani C. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins reduce nerve macrophage infiltration and the severity of bortezomib-induced peripheral neurotoxicity in rats. J Neuroinflammation. (2018) 15:232. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1270-x

59. Montague K, Malcangio M. The therapeutic potential of monocyte/macrophage manipulation in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced painful neuropathy. Front Mol Neurosci. (2017) 10:397. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00397

60. Peters CM, Jimenez-Andrade JM, Jonas BM, Sevcik MA, Koewler NJ, Ghilardi JR. Intravenous paclitaxel administration in the rat induces a peripheral sensory neuropathy characterized by macrophage infiltration and injury to sensory neurons and their supporting cells. Exp Neurol. (2007) 203:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.07.022

61. Shepherd AJ, Copits BA, Mickle AD, Karlsson P, Kadunganattil S, Haroutounian S. Angiotensin II Triggers Peripheral Macrophage-to-Sensory Neuron Redox Crosstalk to Elicit Pain. J Neurosci. (2018) 38:7032–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3542-17.2018

62. Starobova H, Monteleone M, Adolphe C, Batoon L, Sandrock CJ, Tay B. Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy is driven by canonical NLRP3 activation and IL-4 ≤ release. J Exp Med. (2021) 218:5. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201452

63. Starobova H, Mueller A, Allavena R, Lohman R, Sweet MJ, Vetter I. Minocycline prevents the development of mechanical allodynia in mouse models of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy. Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:653. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00653

64. Zhang H, de Carvalho-Barbosa LiY, Kavelaars M, Heijnen A, Albrecht CJPJ et al. Dorsal root ganglion infiltration by macrophages contributes to paclitaxel chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Pain. (2016) 17:775–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.02.011

65. Eldridge S, Guo L, Hamre J. 3rd. A comparative review of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in vivo and in vitro models. Toxicol Pathol. (2020) 48:190–201. doi: 10.1177/0192623319861937

66. Groen CM, Podratz JL, Pathoulas J, Staff N, Windebank AJ. Genetic reduction of mitochondria complex I subunits is protective against cisplatin-induced neurotoxicity in drosophila. J Neurosci. (2022) 42:922–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1479-20.2021

67. Groen CM, Podratz JL, Treb K, Windebank AJ. Drosophila strain specific response to cisplatin neurotoxicity. Fly (Austin). (2019) 12:174–82. doi: 10.1080/19336934.2019.1565257

68. Kim YY, Yoon JH, Um JH, Jeong DJ, Shin DJ, Hong YB. PINK1 alleviates thermal hypersensitivity in a paclitaxel-induced Drosophila model of peripheral neuropathy. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0239126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239126

69. Pero ME, Meregalli C, Qu X, Shin GJ, Kumar A, Shorey M. Pathogenic role of delta 2 tubulin in bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2021) 118:e2012685118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012685118

70. Podratz JL, Lee H, Knorr P, Koehler S, Forsythe S, Lambrecht K. Cisplatin induces mitochondrial deficits in drosophila larval segmental nerve. Neurobiol Dis. (2017) 97:60–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.10.003

71. Podratz JL, Staff NP, Boesche JB, Giorno NJ, Hainy ME, Herring SA. An automated climbing apparatus to measure chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Fly (Austin). (2013) 7 187–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.24789

72. Shin GJ-e, Pero ME, Hammond LA, Burgos A, Kumar A, Galindo SE, et al. Integrins protect sensory neurons in models of paclitaxel-induced peripheral sensory neuropathy. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 118, e2006050118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006050118

73. Gadgil S, Ergün M, van den Heuvel SA, van der Wal SE, Scheffer GJ, Hooijmans CRA. Systematic summary and comparison of animal models for chemotherapy induced (peripheral) neuropathy (CIPN). PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0221787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221787

74. Cavaletti G, Tredici G, Marmiroli P, Petruccioli MG, Barajon I, Fabbrica D. Morphometric study of the sensory neuron and peripheral nerve changes induced by chronic cisplatin (DDP) administration in rats. Acta Neuropathol. (1992) 84:364–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00227662

75. Cirrincione AM, Rieger S. Analyzing chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in vivo using non-mammalian animal models. Exp Neurol. (2020) 23:113090. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113090

76. Marmiroli P, Scuteri A, Cornblath DR, Cavaletti G. Pain in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. J Peripher Nerv Syst. (2017) 22:156–61. doi: 10.1111/jns.12226

77. Rostock C, Schrenk-Siemens K, Pohle J, Siemens J. Human vs. mouse nociceptors—similarities and differences. Neuroscience. (2018) 387:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.11.047

78. Schinke C, Fernandez Vallone V, Ivanov A, Peng Y, Kortvelyessy P, Nolte L. Modeling chemotherapy induced neurotoxicity with human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) -derived sensory neurons. Neurobiol Dis. (2021) 155:105391. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2021.105391

79. Wheeler HE, Wing C, Delaney SM, Komatsu M, Dolan ME. Modeling chemotherapeutic neurotoxicity with human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neuronal cells. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0118020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118020

80. Wainger BJ, Buttermore ED, Oliveira JT, Mellin C, Lee S, Saber WA. Modeling pain in vitro using nociceptor neurons reprogrammed from fibroblasts. Nat Neurosci. (2015) 18:17–24. doi: 10.1038/nn.3886

81. Cetinkaya-Fisgin A, Luan X, Reed N, Jeong YE, Oh BC, Hoke A. Cisplatin induced neurotoxicity is mediated by Sarm1 and calpain activation. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:21889. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78896-w

82. Brewer JR, Morrison G, Dolan ME, Fleming GF. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: current status and progress. Gynecol Oncol. (2016) 140:176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.11.011

83. Kelley MR, Wikel JH, Guo C, Pollok KE, Bailey BJ, Wireman R. Identification and characterization of new chemical entities targeting apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2016) 359:300–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.235283

84. Imai S, Koyanagi M, Azimi Z, Nakazato Y, Matsumoto M, Ogihara T. Taxanes and platinum derivatives impair Schwann cells via distinct mechanisms. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:5947. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05784-1

85. Singh SK, Krukowski K, Laumet GO, Weis D, Alexander JF, Heijnen CJ. CD8+ T cell-derived IL-13 increases macrophage IL-10 to resolve neuropathic pain. JCI Insight. (2022) 7:e154194. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.154194

86. Domoto R, Sekiguchi F, Kamaguchi R, Iemura M, Yamanishi H, Tsubota M. Role of neuron-derived ATP in paclitaxel-induced HMGB1 release from macrophages and peripheral neuropathy. J Pharmacol Sci. (2022) 148:156–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2021.11.003

87. Yang IH, Siddique R, Hosmane S, Thakor N, Hoke A. Compartmentalized microfluidic culture platform to study mechanism of paclitaxel-induced axonal degeneration. Exp Neurol. (2009) 218:124–8. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.017

88. Gornstein EL, Schwarz TL. Mechanisms of paclitaxel are local to the distal axon and independent of transport defects. Exp Neurol. (2017) 288:153–66. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.11.015

89. Mirzoyan Z, Sollazzo M, Allocca M, Valenza AM, Grifoni D, Bellosta P. Drosophila melanogaster: a model organism to study. Cancer Front Genet. (2019) 10:51. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00051

90. Villegas SN. One hundred years of drosophila cancer research: no longer in solitude. Dis Model Mech. (2019) 12:dmm039032. doi: 10.1242/dmm.039032

91. Potter CJ, Turenchalk GS, Xu T. Drosophila in cancer research. An expanding role Trends. Genet. (2000) 16:33–9. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01878-8

92. Fernandez-Hernandez I, Marsh EB, Bonaguidi MA. Mechanosensory neuron regeneration in adult drosophila. Development. (2021) 148:dev187534. doi: 10.1242/dev.187534

93. Podratz JL, Staff NP, Froemel D, Wallner A, Wabnig F, Bieber AJ. Drosophila melanogaster: a new model to study cisplatin-induced neurotoxicity. Neurobiol Dis. (2011) 43:330–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.03.022

94. Hamoudi Z, Khuong TM, Cole T, Neely GG. A fruit fly model for studying paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy and hyperalgesia. F1000Res. (2018) 7:99. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.13581.2

95. Singhania A, Grueber WB. Development of the embryonic and larval peripheral nervous system of drosophila. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. (2014) 3:193–210. doi: 10.1002/wdev.135

96. Bodmer R, Jan YN. Morphological differentiation of the embryonic peripheral neurons in drosophila. Rouxs Arch Dev Biol. (1987) 196:69–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00402027

97. Grueber WB, Jan LY, Jan YN. Tiling of the drosophila epidermis by multidendritic sensory neurons. Development. (2002) 129:2867–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.2867

98. Hwang RY, Zhong L, Xu Y, Johnson T, Zhang F, Deisseroth K. Nociceptive neurons protect Drosophila larvae from parasitoid wasps. Curr Biol. (2007) 17:2105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.029

99. Tsubouchi A, Caldwell JC, Tracey WD. Dendritic filopodia, Ripped Pocket, NOMPC, and NMDARs contribute to the sense of touch in Drosophila larvae. Curr Biol. (2012) 22:2124–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.019

100. Turner HN, Armengol K, Patel AA, Himmel NJ, Sullivan L, Iyer SC. The TRP channels Pkd2, nompc, and trpm act in cold-sensing neurons to mediate unique aversive behaviors to noxious cold in drosophila. Curr Biol. (2016) 26:3116–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.038

101. Yan Z, Zhang W, He Y, Gorczyca D, Xiang Y, Cheng LE. Drosophila NOMPC is a mechanotransduction channel subunit for gentle-touch sensation. Nature. (2013) 493:221–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11685

102. Stone MC, Roegiers F, Rolls MM. Microtubules have opposite orientation in axons and dendrites of drosophila neurons. Mol Biol Cell. (2008) 19:4122–9. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-10-1079

103. Hall DH, Treinin M. How does morphology relate to function in sensory arbors? Trends. Neurosci. (2011) 34:443–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.07.004

104. Poe AR, Tang LF, Wang B, Sapar LiY, Han ML, Dendritic C. Space-filling requires a neuronal type-specific extracellular permissive signal in drosophila. P Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017)114:E8062–E71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707467114

105. Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy WR, Walk D. Morphological features of nerves in skin biopsies. J Neurol Sci. (2006) 242:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.11.010

106. Kim ME, Shrestha BR, Blazeski R, Mason CA, Grueber WB. Integrins establish dendrite-substrate relationships that promote dendritic self-avoidance and patterning in drosophila sensory neurons. Neuron. (2012) 73:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.033

107. HanC Wang D, Soba P, Zhu S, Lin X, Jan LY. Integrins regulate repulsion-mediated dendritic patterning of drosophila sensory neurons by restricting dendrites in a 2D space. Neuron. (2012) 73:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.036

108. Anderl I, Vesala L, Ihalainen TO, Vanha-Aho LM, Ando I, Ramet M. Transdifferentiation and proliferation in two distinct hemocyte lineages in drosophila melanogaster larvae after wasp infection. PLoS PATHOG. (2016) 12:e1005746. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005746

109. Shin M, Cha N, Koranteng F, Cho B, Shim J. Subpopulation of macrophage-like plasmatocytes attenuates systemic growth via JAK/STAT in the drosophila fat body. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:63. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00063

110. Tattikota SG, Cho B, Liu Y, Hu Y, Barrera V, Steinbaugh MJ. A single-cell survey of drosophila blood. Elife. (2020) 9:e54818. doi: 10.7554/eLife.54818

111. Weavers H, Evans IR, Martin P, Wood W. Corpse engulfment generates a molecular memory that primes the macrophage inflammatory response. Cell. (2016) 165:1658–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.049

112. Makhijani K, Alexander B, Rao D, Petraki S, Herboso L, Kukar K. Regulation of drosophila hematopoietic sites by activin-beta from active sensory neurons. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:15990. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15990

113. Makhijani K, Alexander B, Tanaka T, Rulifson E, Bruckner K. The peripheral nervous system supports blood cell homing and survival in the drosophila iarva. Development. (2011) 138:5379–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.067322

114. Kolter J, Feuerstein R, Zeis P, Hagemeyer N, Paterson N., d'Errico P, et al. A subset of skin macrophages contributes to the surveillance and regeneration of local nerves. Immunity. (2019) 50:1482–97. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.05.009

115. Fowler MA, Montell CD. Channels and animal behavior. Life Sci. (2013) 92:394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.07.029

116. He J, Li B, Han S, Zhang Y, Liu K, Yi S. Drosophila as a model to study the mechanism of nociception. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:854124. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.854124

117. Cosens DJ, Manning A. Abnormal electroretinogram from a Drosophila mutant. Nature. (1969) 224:285–7. doi: 10.1038/224285a0

118. Osterloh JM, Yang J, Rooney TM, Fox AN, Adalbert R, Powell EH. dSarm/Sarm1 is required for activation of an injury-induced axon death pathway. Science. (2012) 337:481–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1223899

119. Bussmann J, Storkebaum E. Molecular pathogenesis of peripheral neuropathies: insights from drosophila models. Curr Opin Genet Dev. (2017) 44:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.01.011

120. Im SH, Galko MJ. Pokes, sunburn, and hot sauce: drosophila as an emerging model for the biology of nociception. Dev Dyn. (2012) 241:16–26. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22737

121. Ainsley JA, Pettus JM, Bosenko D, Gerstein CE, Zinkevich N, Anderson MG. Enhanced locomotion caused by loss of the drosophila DEG/ENaC protein pickpocket1. Curr Biol. (2003) 13:1557–63. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00596-7

122. Grueber WB, Ye B, Moore AW, Jan LY, Jan YN. Dendrites of distinct classes of drosophila sensory neurons show different capacities for homotypic repulsion. Curr Biol. (2003) 13:618–26. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00207-0

123. del Valle Rodriguez A, Didiano D, Desplan C. Power tools for gene expression and clonal analysis in drosophila. Nat Methods. (2011) 9:47–55. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1800

124. Rubin GM, Yandell MD, Wortman JR, Gabor Miklos GL, Nelson CR, Hariharan IK. Comparative genomics of the eukaryotes. Science. (2000) 287:2204–15. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2204