- 1Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research Program, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2Western Australian Center for Rural Health, University of Western Australia, Geraldton, WA, Australia

- 3North Queensland Persistent Pain Management Service, Townsville Hospital and Health Service, Townsville, QLD, Australia

- 4Centre for Business and Economics of Health, Faculty of Business, St Lucia, QLD, Australia

- 5Tess Cramond Pain and Research Centre, Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 6School of Psychology and Counselling, Faculty of Health, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 7Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Division, Cultural Capability Services, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 8Persistent Pain Clinic, Metro South Hospital and Health Service, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Background: Pain management requires a multidisciplinary approach and a collaborative relationship between patient-provider in which communication is crucial. This study examines the communication experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Hospital Liaison Officers (ATSIHLOs), to improve understanding of how pain is managed in and through patient-health professional communication.

Methods: This qualitative study involved a purposive sample of patients attending three persistent pain clinics and ATSIHLOs working in two hospitals in Queensland, Australia. Focus groups and in-depth interviews explored the communication experiences of patients managing pain and ATSIHLOs supporting patients with pain. This study adopted a descriptive phenomenological methodology, as described by Colaizzi (1978). Relevant statements (patient and ATSIHLOs quotes) about the phenomenon were extracted from the transcripts to formulate meanings. The formulated meanings were subsequently sorted into thematic clusters and then integrated into themes. The themes were then incorporated into a concise description of the phenomenon of communication within pain management. Findings were validated by participants.

Results: A total of 21 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants were involved in this study. Exploration of the communication experiences of patients and ATSIHLOs revealed overlapping themes of important barriers to and enablers of communication that affected access to care while managing pain. Acknowledging historical and cultural factors were particularly important to build trust between patients and health professionals. Some patients reported feeling stigmatized for identifying as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, while others were reluctant to disclose their background for fear of not having the same opportunity for treatment. Differences in the expression of pain and the difficulty to use standard pain measurement scales were identified. Communication was described as more than the content delivered, it is visual and emotional expressed through body language, voice intonation, language and the speed of the conversation.

Conclusion: Communication can significantly affect access to pain management services. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients highlighted the burden of emotional pain caused by historical factors, negative stereotypes and the fear of discrimination. Pain management services and their health professionals need to acknowledge how these factors impact patients trust and care.

Introduction

Pain management aims to control patients’ pain or their responses to pain using multidisciplinary approaches in collaborative relationships with patients, to achieve self-efficacy and improve quality of life (1). Pain can cause physical disability, depression and lower quality of life (2, 3). Chronic or persistent pain can be an impetus for patients to seek health care (4). Because pain is a subjective and biopsychosocial phenomenon, effective pain management relies on effective communication between patients and health practitioners (5). Effective communication underpins fundamental aspects of pain care, including pain assessment, establishing management goals, and implementing treatment plans and follow-ups (6).

Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the burden of musculoskeletal pain conditions is 1.4 times higher than that of the non-Indigenous population. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are at a higher risk of disabling musculoskeletal pain due to a high prevalence of health, lifestyle and psychological risk factors for pain. These factors result in significant disparities in pain management outcomes (7, 8). For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, there are many barriers to access care, including geographical isolation, social-economic disadvantages, and poor experiences with health care (9, 10). The determinants of health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are a result of the impact of colonisation in their communities and culture (11). The destruction of culture with significant disempowerment and marginalisation had a widespread effect on the physical and mental health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (12). Poverty and racism have been associated with adverse health outcomes and discrimination (unjust treatment) that can occur at any stage of the lifespan (13). A recent nationwide study involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders people found that 58.5% of participants reported experiencing discrimination. Discrimination was significantly associated with diverse impacts on social and emotional wellbeing, culture and identity, health behaviour, and health outcomes. Moreover, these impacts were greatest amongst those reporting moderate-high levels of discrimination (14). This association between discrimination and health outcomes is important in the context of differences in life expectancies between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and non-Indigenous Australians highlighting the need to address discrimination as part of reducing this gap (15).

Ineffective communication is also a major barrier for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to access health care to manage their pain (5, 16). A study exploring communication experiences in pain management of Aboriginal people in two rural communities found that participants experienced discrimination from health care providers which consequently deterred people from seeking care for their pain (17). It has also been found that there is a lack of awareness and an acceptance of a deficient cross-cultural communication as the norm (18, 19). The extent of miscommunication and the potential health impact for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients is often not well understood by either health care providers or patients (20). A review of the needs of Aboriginal people with musculoskeletal pain demonstrated that focussing on improving patients' experiences of care, in particular with regards to patient-provider communication, is a crucial part of increasing access to care, by ensuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can trust pain providers (8).

To understand the role of communication in detail, this study was designed to examine the communication experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients managing persistent pain and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Hospital Liaison Officers (ATSIHLO) who support these patients, aiming to identify how communication affected patients’ pain management and their communication preferences.

Methods

Study design

The present study is part of the first phase of a multi-centre interventional feasibility study to improve communication between health professionals and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients accessing persistent pain management services in Queensland, Australia. Details of the study protocol have been previously described (21).

The current study reports an analysis of the communication experiences of patients managing pain and of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Hospital Liaison Officers supporting patients managing pain. The findings of the health professionals' perspectives of communication needs and training preferences have been previously published (22).

Study participants and settings

A purposive sampling approach was used in the study. A service-based researcher (AC, JPK, MT and MB) at each study site identified potential participants. One participant group were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients attending three (2 metropolitan and one regional) of the five publicly-funded adult persistent pain services in Queensland. A second participant group were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Hospital Liaison Officers (ATSIHLOs) working at two study sites (one metropolitan and one regional).

The persistent pain clinics are hospital-based, providing outpatient and inpatient care for people with complex pain who require a multidisciplinary approach to management. According to services audit data, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients represent between 4%–8% of the total number of patients supported by the three services involved in this study. The ATSIHLOs are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in hospitals. Their role is to support and advocate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients and/or their families and act as a cultural broker between the patient/their family and health care services.

Access to the persistent pain clinics and multidisciplinary clinical interactions

The persistent pain clinics provide tailored care to patients within a biopsychosocial framework. These services aim to rehabilitate and promote self-management. Access to these services depends upon a referral usually from a general practitioner (GP). After patients are referred to the pain clinic, they are assessed according to clinical urgency following the Clinical Prioritisation Criteria (CPC): category 1 (urgent appointment within 30 days), category 2 (appointment within 90 days) and category 3 (appointment within 365 days). The first clinical interaction will involve the patient assessment by a specialist pain physician, sometimes joined by another member of the multidisciplinary team (e.g., physiotherapist, nurse, and psychologist). This interaction may take 1–2 h and options for treatment and pain management will be discussed. A patient may require adjustments to the medication, allied health assessments (e.g., physiotherapy, psychology and occupational therapy), group therapy or surgical procedures. Individual management paths vary greatly but at minimum, patients will be supported during a limited timeframe (approximately 12 months) and will be encouraged to take an active role in learning self-management strategies that address their pain.

Data generation

Patients were initially invited to participate in a focus group. For patients who were unable to attend the focus group, in-depth interviews were offered. Patients' and ATSIHLOs data were generated through focus groups or in-depth interviews during the period of October-December 2020. An interview guide was used to ensure the interviews explored the communication experiences of patients managing pain and the experiences of ATSIHLOs working at the study sites supporting these patients. The focus groups were facilitated by an Aboriginal researchers (GP, JI), supported by an Aboriginal research assistant (KH or MT) and two non-Indigenous researchers (CMB and CJ). The in-depth interviews were conducted by two Aboriginal interviewers (MT and KH) and supported by a non-Indigenous researcher (CMB). The focus groups and in-depth interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and imported to Microsoft Excel. Separately, the interviewers (CMB, MT and KH) used the Microsoft Excel files for analysis.

Data analysis

This study adopted a descriptive phenomenological methodology, as described by Colaizzi (1978) (23, 24), to explore the lived experience of communication within pain management at three pain clinics. Colaizzi's method includes seven distinctive steps, six of them with an extensive description of the phenomenon under study (familiarisation, identifying significant statements, formulating meanings, clustering themes, developing an exhaustive description, and producing a fundamental structure) and a final step of validating findings from the participants who provided the data. The data generated through the focus groups and interviews with participants were reviewed several times by two researchers (CMB, KH). Each researcher independently created a table comprised of relevant statements (patient quotes). These statements were subsequently formulated into meanings and then grouped into thematic clusters. The researchers discussed their findings before identifying the main themes from the data. Each researcher then used the identified themes to develop several descriptions about the findings. These exhaustive descriptions were then revised and condensed until a final concise statement was reached. This statement was then sent to two participants from each group (i.e., patients and ATSIHLOs) for validation.

Researchers' characteristics and reflexivity

The research team was composed of researchers from diverse academic disciplines, including medicine, nursing, psychology and physiotherapy. The team includes both, non-clinician researchers (8) and clinicians-researchers (5). The team is also comprised of researchers from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Five of the authors are of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background and all the remaining authors are non-Indigenous. The research team composition promoted reflexivity across the research process, by including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander as well as non-Indigenous perspectives, clinical and non-clinical perspectives, and multidisciplinary perspectives.

Results

Participants' characteristics

Although the communication experiences reported here were all related to pain management, these experiences were not limited to persistent pain clinic services. Participants chose to describe their communication experiences across various settings such as emergency departments, general practice appointments, aged-care, or inpatient hospital care.

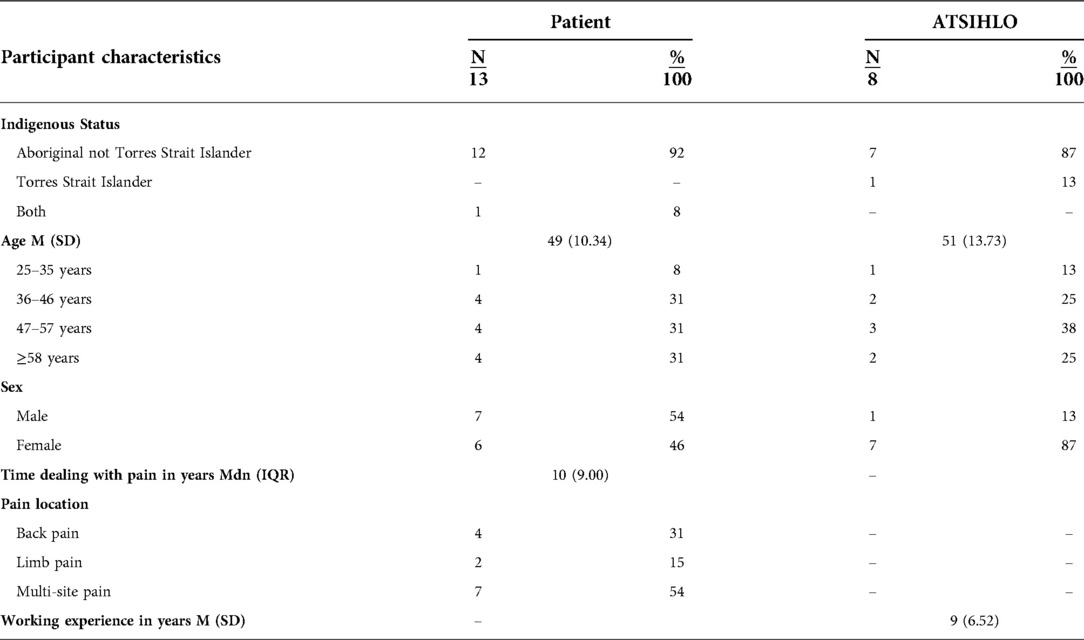

A total of 21 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants, 13 patients and 8 ATSIHLOs, were involved in this study. Participants were similar in their demographic characteristics.

Patients participated in one focus group (N = 3) and in-depth interviews (N = 10). Patients were more frequently Aboriginal (92%) than Torres Strait Islander, aged on average 49 years (SD = 10.34) and more than half were males (54%) (Table 1). Patients lived with pain for a median time of 10 years (range 4–55 years) and more than half (54%) were managing multi-site pain issues.

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics, patients time dealing with pain and Aboriginal and Torres Hospital Liaison Officers working experience.

The ATSIHLOs participated in a focus group (n = 6) and in-depth interviews (N = 2). A high proportion of ATSIHLOs were Aboriginal (87%), on average 51 years (SD = 13.73) and were working on average 9 years (SD = 6.52) in this role.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander hospital liaison officers' experiences and perceptions of communication: identified themes

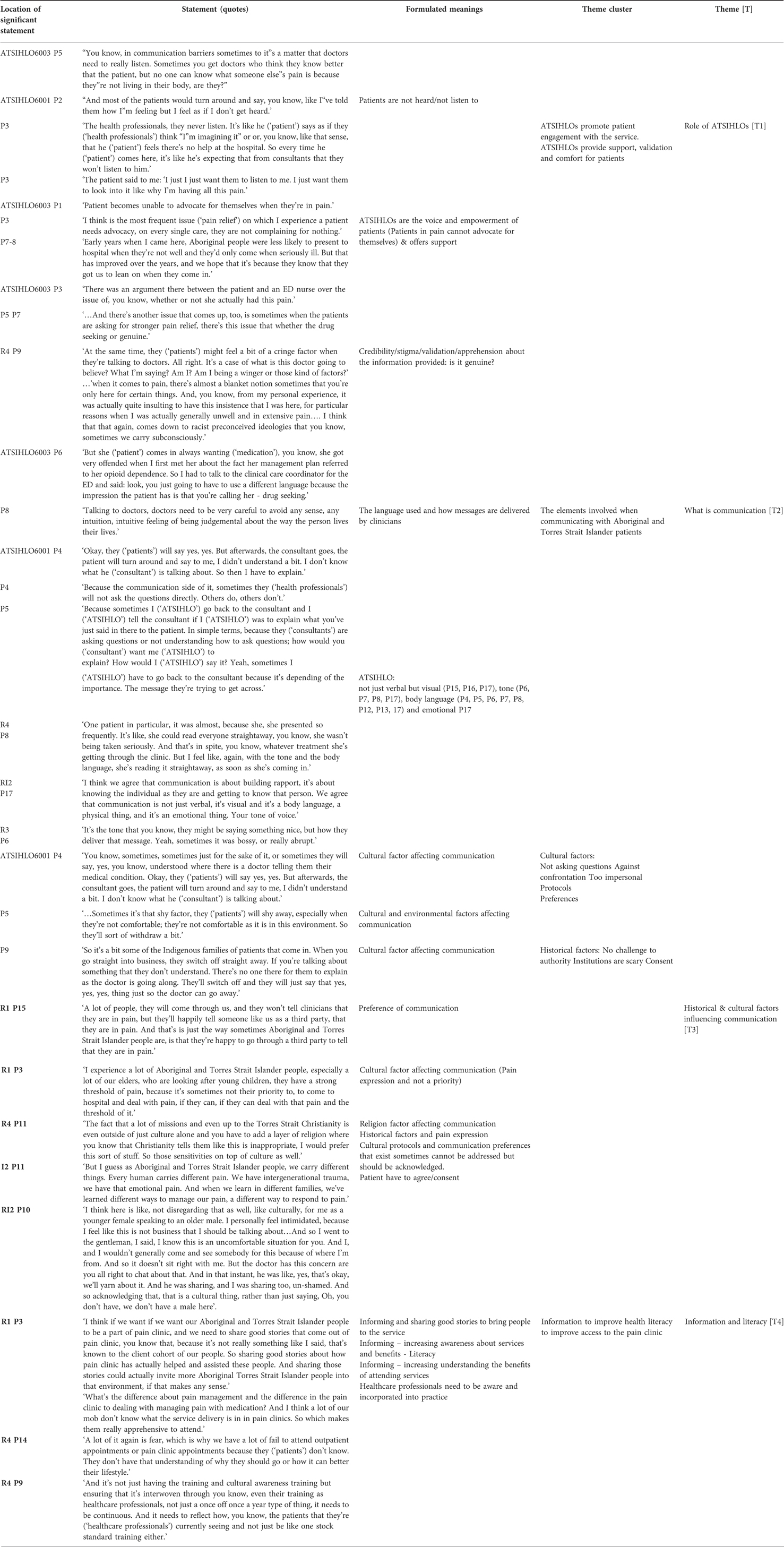

Table 2 shows the process of formulating meanings and clusters of the data derived from focus groups and interviews with ATSIHLOs. Through this process four themes and nine subthemes were identified. Theme 1 was clustered around “the role of ATSIHLOs” and had three subthemes: a) patients are not heard, b) ATSIHLO are the voice, support and empowerment of patients, and c) information credibility. In theme 2, “what is communication”, participants described their perception of communication and had two subthemes: (a) language and delivery of the message, and (b) elements of communication. Theme 3, was clustered around “historical and cultural factors influencing communication” and had three subthemes: (a) cultural factors; (b) historical factors (c) communication preferences; Theme 4, was clustered on “information and literacy” and had two subthemes: (a) sharing good stories and (b) increasing awareness about services. Supplementary Appendix S1 contains a final exhaustive description of ATSIHLOs’ experiences of communication that is based on the analysis of data generated for this study.

Table 2. Process of formulating meanings and clusters for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander hospital liaison officers (ATSIHLOs).

Condensed fundamental structure of the ATSIHLOs lived experience of communication within pain management

The ATSIHLOs identified that the way information is delivered to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients can significantly impact their engagement with treatment plans and health services. Patients may disengage from a conversation if the language is too complex, impersonal or perceived as judgemental about the way a person lives their life. Communication between patients and health professionals was described as being very visual, because patients are very attentive to health professionals’ vocal intonation and non-vocal conduct, which is perceived as communicating “emotion”. ATSIHLOs highlighted the importance of health professionals be aware that they sometimes unconsciously or unintentionally give cues that imply judgement about the way people live their lives (e.g., body language or leading questions) [T2].

ATSIHLOs reflected on the fact that many patients do not have high literacy levels and consequently have limited understanding of how health services operate and what support they can offer. ATSIHLOs emphasised the importance of promoting the positive results achieved by the pain management services with patients and families to encourage people to seek care. ATSIHLOs recommended that to improve communication between patients and health professionals it is not enough for health professionals be aware of the existence of an ATSIHLO but actually offer this support service to patients. This would help to provide a supportive environment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients [T4].

Furthermore to provide a supportive environment ATSIHLO mentioned two very strong perceptions related to information and acknowledgement of cultural protocols: the need for acknowledgement of cultural differences and demonstration of respect to cultural protocols (e.g., related to gender of the patient and health professionals); and patient consent. For example, health professionals should acknowledge to patients that they are aware of the cultural protocol with regards to gender and age group, and in a situation of absence of a health professional of the same gender or age group, confirm with the patients, that they would still be agreeable to proceed with the assessments in this situation. This would demonstrate acknowledgement and respect to cultural protocols [T3].

Exploration of the communication experiences of ATSIHLOs revealed the important role these professionals have while supporting patients in managing pain. ATSIHLOs are pivotal in reducing tensions and increasing the trust between the patient-clinician. ATSIHLOs identified that of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, those living with persistent pain would be the most likely to require ATSIHLOs support. Patients in pain experience vulnerability, are unable to advocate for themselves and feel that they are not heard. There is frequently a tension from patients trying to have their pain validated but feeling that health professionals do not believe their experience of pain [T1].

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patient's experiences and perceptions of communication: identified themes

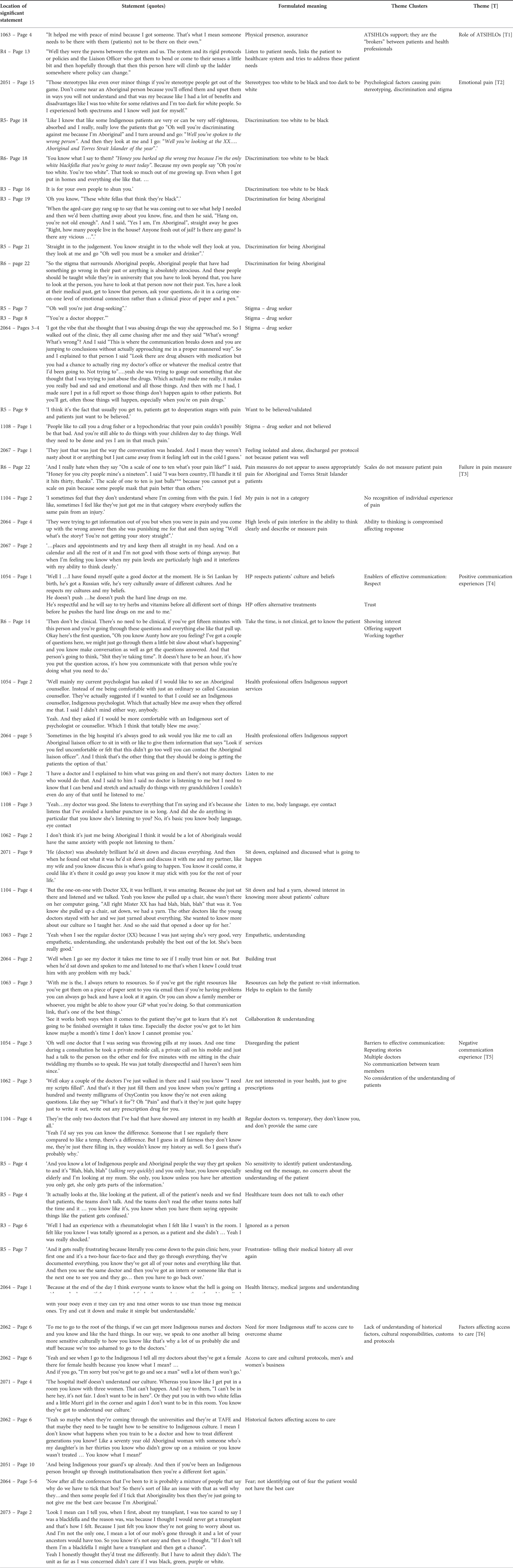

Table 3 presents the process of formulating meanings and clusters of the data derived from focus groups and interviews with patients. Six themes and 15 sub-themes were identified: (i) ATSIHLOs' role of providing assurance through their physical presence and listening to patients' needs; (ii) emotional pain: caused by stereotypes, discrimination, feeling alone and not being believed; (iii) pain measures: scales are not appropriate to measure my pain; (iv) positive experiences of communication: trust, the health professionals know me, being able to identify, explain what was going to happen; (v) negative experiences of communication: throwing pills on issues, no alternative treatment, disregard or ignored as a person, no sensitivity to patient understanding and health literacy; and (vi) factors affecting access to care: need for more Indigenous staff, access to care and respect to cultural protocols, fear of identifying as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person. Supplementary Appendix S2 contains a final exhaustive description of patients' experiences of communication that is based on the analysis of data generated for this study.

Table 3. Process of formulating meanings and clusters for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.

Condensed fundamental structure of the patients lived experience of communication within pain management

Patients managing pain described their experience as of vulnerability, recounting their stories and searching for the cause of their persistent pain. In this search, patients sought for care in several services and communicated with many health professionals. This journey challenged patients to understand how they were approached by health professionals, assessed and supported. Patients confirmed the “broker” role of ATSIHLOs in breaking down communication barriers and linking patients to the service. The simple fact of having the presence of an ATSIHLO gave some patients the assurance of a safer environment [T1].

Patients described that their physical pain would sometimes be secondary to family and community commitments and responsibilities. Being in pain affected patients' response to assessments, and sometimes they felt their responses did not align with the expectation of the health professional. This would cause tension, mistrust and a feeling that patients were not heard by health professionals. Patients described feeling emotional pain for being discriminated and stigmatised. This included discrimination on the basis of being an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person. Conversations would change just by the fact that the patient disclosed their background and questions would be directed to issues with drugs and alcohol misuse, and incarceration. For some, it also included discrimination on the basis of not having a stereotypical physical appearance of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person (e.g., fair skin). Lack of acceptance of patients' Indigeneity, fear of less opportunities for care and a stigma of being seen as a “drug seeker”, combined with the shame of sometimes not disclosing their Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background, caused significant emotional pain to patients. Patients' trust that health professionals would help in the management of their pain was increased when patients felt heard. In these situations, patients felt respected and would disclose more details about themselves [T2].

Positive communication experiences were reported when the health professional invested more time exploring patients' cultural background and beliefs, recommended alternative treatments (e.g., vitamins, traditional or herbal treatments) and offered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander support services (ATSIHLOs or community services) [T4].

In contrast to the positive experiences that were reported, patients perceived that their pain management would be compromised when health professionals would not communicate with them, and would continuously prescribe medication without verifying how the patients were feeling. These health professionals were perceived as “throwing pills on issues” and disregarding the patients' health. This affected patients' ability to physically function, to work and to be active [T5].

Factors such as increasing the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff, patient age, health literacy and cultural protocols (e.g., men's and women's business) should be observed during consultations to improve communication. This was especially relevant to elderly patients living in a more traditional cultural environment, who felt extremely challenged to manage pain and navigate an environment that does not recognize their protocols and customs with regards to age, gender and role in society as an Elder [T6].

Discussion

This study explored patients' and ATSIHLOs' communication experiences across different settings of the healthcare system while managing pain or supporting patients with pain. Although previous studies have explored communication and barriers to management of pain among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients (5, 17), this study describes the phenomenon of patients' preferences for communication and ways communication affected their pain management. The main findings of the study is that effective communication for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients in the pain management depends fundamentally on trust, based on the understanding of the impact of emotional pain caused by historical factors, stereotyping and discrimination, and by acknowledging cultural protocols. It is well understood that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander understandings of health are typically broader than those held by non-Indigenous Australians and this holistic understanding is not well accommodated by mainstream healthcare services. The current study identifies important factors for holistically treating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients (25). Some of these findings are specific to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients experiencing pain, while others may be transferrable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients more generally.

Trust is built when patients feel that the health professionals know them or that they want to know about them. When health professionals actively listen and learn about the patient, that patient is more likely to trust them. In this context, actively listening often requires understanding the factors underpinning the extent to which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders engage with health services (e.g., historical factors, racism/discrimination, and protocols around gender).

Patient perceptions of not being heard or believed and consequently feeling that they have ongoing untreated pain with results that were below their expectations are findings shared by other studies amongst non-Indigenous participants living with persistent pain (26, 27). However, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients this situation appears to be aggravated by the perception of persistent disregard of them as individuals. This perception links back to the historical events of colonisation and struggle for recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity (28). Further, some of the frustration of not being heard reported by patients may be caused by the complex and subjective nature of pain (29). Health professionals argue that many persistent pain conditions are of non-specific origin, are difficult to differentiate given the diagnostic criteria and diagnosis based heavily on exclusion (30). Additionally, pain may be dismissed or overlooked as someone else's responsibility. Health professionals, especially in primary care, may have time constraints during standard consultations and pain management may be an “add-on” to assessing and managing other chronic diseases. Specialists outside pain medicine may feel it is not their area of expertise. The multidimensional nature of persistent pain and challenges in managing it in generalist health care settings are barriers to optimal pain care (26).

Particular to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients managing pain is the frustration and emotional pain caused by historical discrimination, stereotypes and stigma. Patients reported enduring emotional pain during some interactions with health professionals and support services. Some of the emotional pain resulted from stereotypes about what the physical appearance of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person should be. Patients with fair skin reported being questioned and not being accepted as being Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. According to Paradies (13) racism can be expressed through stereotypes (cognition), prejudice (emotions) or discrimination (behaviours). The questioning of patients Indigeneity due to their skin colour made patients feel that did not belong and for some, resulted in considerable psychological distress. Research on Aboriginal mental health and wellbeing highlights the importance of a strong connection to culture and pride about Aboriginal identity (31). A positive cultural identity can impact on the individual sense of belonging, social support and self-confidence (32). Another cause of emotional pain for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients was the fear of discrimination. Patients described an intense internal conflict between deciding to disclose their Indigeneity, and face the risk of not receiving the same treatment as other patients, or feeling guilty for not acknowledging their background. Some patients reported that there was an instant change in the conversation prompted by their background disclosure which caused them significant psychological distress.

Discrimination or stereotype threat has been found to impair performance by inducing psychological distress, poorer mental health and decreased life satisfaction (33). Persistent exposure to stereotype threat may result in avoidance or withdrawal from the threatening situation. The process begins with patient awareness that they belong to a group negatively stereotyped, making them more vigilant for cues that confirm the negative stereotype. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people discrimination was found to be associated with negative outcomes in physical and emotional well-being, and was similar when discrimination was attributed to Indigeneity (i.e., racial discrimination) or when discrimination was not attributed to Indigeneity. However, attribution to Indigeneity was more frequently reported by people experiencing moderate-high compared to low levels of discrimination (90.6% vs. 63.5%, respectively) (14). While the costs of racism and discrimination have been well documented, it remains less clear in the Australian context what predicts attitudes and behaviours that affect negatively the outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders people (34, 35). Implicit prejudice (“unintentional”) appears to cause more damage than deliberate prejudice given that discrimination is experienced in a variety of contexts (e.g., labour market, criminal justice, and housing).34With regards to pain, there was a variation of attribution when examining the association between discrimination and outcome (14). Attribution is difficult, as individuals may have multiple characteristics for which they may be disadvantaged (e.g., race, gender, age, and socio-economic status) and the interaction of these characteristics influence the type of experiences an individual has and inequalities (36). Further research is required to better understand why a divergent pattern emerged for pain.

Discrimination and stereotypes can also affect communication. When the communication between patients and health professionals is not perceived as respectful and pleasant, patient health outcomes will most likely be impacted (37). An Australian longitudinal study exploring the health system navigation by marginalized groups (i.e., people living in rural or remote areas, sexuality and/or gender diverse, refugee, homeless, and/or Aboriginal) identified that participants perceived and experienced multiple forms of discrimination impacting on their access to care and contributing for further marginalization. Many participants reported that health professionals failed to understand how multiple disadvantage could affect their ability to navigate through the health system. The participants also indicated that access to information to improve health literacy, reduce stigma about seeking support and help in the decision making process could mitigate the impact of discrimination and stereotypes (38). Good communication between patient-provider can promote adherence to lifestyle changes, appropriate medical treatment and improve the reported experience of care (39, 40).

In this study, some patients acknowledged that their fears were unfounded and that they felt empowered by disclosing their background and were fully supported by health professionals.

With regards to pain measure, patients in this study reported being locked into a category that would not reflect their individual experience of pain. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients historical factors related to colonization, institutionalization and separation contributes to a significant burden of emotional pain making the physical pain sometimes less important (17) and more difficult to measure with standard measurement tools (41). A literature review investigating the pain expression among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples found that health professionals' expectations of pain expression based on predominantly Caucasian experiences may affect the interpretation of observations (16). For example, some patients would present verbal and non-verbal silence in response to pain (42). Family and community responsibilities will mostly prevail above patients own health concerns and knowledge about the pain experience and the design of culturally-relevant scales for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people essential (41).

Among the enablers of communication and improvement in pain management, patients and ATSIHLOs agreed that demonstrating understanding and acknowledging cultural differences and protocols were imperative to establish trust and a collaborative relationship between health professionals and patients. An empathetic and culturally sensitive approach could reduce tension and instigate a conversation about what is relevant to the patient and not be dictated exclusively by a clinical agenda. Most of the participants agreed that when they felt listened to, they could trust the health professional. Respect for some cultural protocols regarding age and gender, e.g., men's and women's business, were mentioned by many patients. Recognising the importance of integrating cultural knowledge and contextualising this to the clinical setting, the current study informs a communication intervention designed to enhance capacity in culturally competent care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients with pain (21).

Conclusion

Communication can significantly affect access to pain management services. Although some of the communication experiences in pain management are common to most patients, there are specific issues for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients highlighted the burden of emotional pain caused by historical factors, negative stereotypes and the fear of discrimination. Health professionals who provide pain management services need to acknowledge how these factors impact patients and their trust. A model of care that combines greater cultural understanding and fosters trust and respect between patient and health professional could mitigate emotional pain and enable pain management services that are more patient–centred and improve access and effectiveness of service.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by a Queensland Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number 63949) and endorsed by ethics committees at the three participating study sites. All participants provided their written informed consent to be involved in the study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, CMB, SE, SB, RM, MB, JI, PG, JK, IL and GP; Data curation, CMB, AC, MB, JK, CJ, KH and MT; Formal analysis, CMB, KH, MT, SE, SB, RM, AC, IL; Funding acquisition, MB, PG, DW, IL and GP; Methodology, CMB, SE, SB, RM, AC, MB, JI, JK, DW, IL and GP; Project administration, CMB and GP; Resources, JI, PG, CJ, IL, KH and MT; Supervision, MB, PG and JK; Validation, SE, SB, JI and IL; Writing – original draft, CMB, SE and IL; Writing – review & editing, CMB, SE, SB, RM, AC, MB, JI, PG, JK, DW, CJ, IL, KH, MT, and GP. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by Brisbane Diamantina Health partners (BDHP) – Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF): Rapid Applied Research Translation (RART) Grant Opportunity.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank the participants and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Liaison Hospital Officers from the study sites who were essential for the conduct of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpain.2022.1041968/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. Takai Y, Yamamoto-Mitani N, Abe Y, Suzuki M. Literature review of pain management for people with chronic pain. Jpn J Nurs Sci. (2015) 12(3):167–83. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12065

2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020. Chronic pain in Australia. Cat. no. PHE 267. Canberra: AIHW.

3. Henderson JV, Harrison CM, Britt HC, Bayram CF, Miller GC. Prevalence, causes, severity, impact, and management of chronic pain in Australian general practice patients. Pain Med. (2013) 14(9):1346–61. doi: 10.1111/pme.12195

4. Loeser JD, Melzack R. Pain: an overview. Lancet. (1999) 353(9164):1607–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01311-2

5. Lin I, Green C, Bessarab D. Improving musculoskeletal pain care for Australia's First peoples: better communication as a first step. J Physiother. (2019) 65(4):183–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2019.08.008

6. Henry SG, Matthias MS. Patient-Clinician communication about pain: a conceptual model and narrative review. Pain Med. (2018) 19(11):2154–65. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny003

7. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017. The burden of musculoskeletal conditions in Australia: a detailed analysis of the Australian burden of disease study 2011. Australian Burden of Disease Study series no. 13. BOD 14. Canberra: AIHW.

8. Lin IB, Bunzli S, Mak DB, Green C, Goucke R, Coffin J, et al. Unmet needs of aboriginal Australians with musculoskeletal pain: a mixed-method systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). (2018) 70(9):1335–47. doi: 10.1002/acr.23493

9. Aspin C, Brown N, Jowsey T, Yen L, Leeder S. Strategic approaches to enhanced health service delivery for aboriginal and torres strait islander people with chronic illness: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2012) 12:143. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-143

10. Durey A, Thompson SC, Wood M. Time to bring down the twin towers in poor aboriginal hospital care: addressing institutional racism and misunderstandings in communication. Intern Med J. (2011) 42(1):17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02628.x

11. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2022. Determinants of health for Indigenous Australians.

12. Parker R. Part 1: history and contexts. In: Purdie N, Dudgeon P, Walker R, editors. Working together: Aboriginal and torres strait islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Canberra: Canberra Commonwealth of Australia (2010), p. 3–69.

13. Paradies YC. Defining, conceptualizing and characterizing racism in health research. Crit Pub Health. (2006) 16(2):143–57. doi: 10.1080/09581590600828881

14. Thurber KA, Colonna E, Jones R, Gee GC, Priest N, Cohen R, et al. Prevalence of everyday discrimination and relation with wellbeing among aboriginal and torres strait islander adults in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(12):6577. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126577

15. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and torres strait islander health performance framework 2020 summary report. Cat. no. IHPF 2. Canberra: AIHW (2020).

16. Arthur L, Rolan P. A systematic review of western medicine's Understanding of pain experience, expression, assessment, and management for Australian aboriginal and torres strait islander peoples. Pain Rep. (2019) 4(6):e764. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000764

17. Strong J, Nielsen M, Williams M, Huggins J, Sussex R. Quiet about pain: experiences of aboriginal people in two rural communities. Aust J Rural Health. (2015) 23(3):181–4. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12185

18. Amery R. Recognising the communication gap in indigenous health care. MJA. (2017) 207(1):13–5. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00042 28659103

19. Burnette L, Kickett M. “You are just a puppet”: australian aboriginal people's Experience of disempowerment when undergoing treatment for end-stage renal disease. Ren Soc Aust J. (2009) 5(3):113–8.

20. Lowell A. Communication and cultural knowledge in aboriginal health care. 1998. cooperative research centre for aboriginal and tropical health's indigenous health and education research program. retrieved at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.180.6365&rep=rep1&type=pdf

21. Bernardes CM, Lin I, Birch S, Meuter R, Claus A, Bryant M, et al. Study protocol: clinical yarning, a communication training program for clinicians supporting aboriginal and torres strait islander patients with persistent pain: a multicentre intervention feasibility study using mixed methods. Public Health in Practice. (2021) 3:3. Article number: 100221. doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100221

22. Bernardes CM, Ekberg S, Birch S, Meuter RFI, Claus A, Bryant M, et al. Clinician perspectives of communication with aboriginal and torres strait islanders managing pain: needs and preferences. IJERPH. (2022) 19(3):1572. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031572

23. Colaizzi PF. Psychological research as the phenomenological views it. In: Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology. Valle R.S. and King M.: New York: Oxford University Press; 1978:6.

24. Morrow R, Rodriguez A, King N. Colaizzi's descriptive phenomenological method. Psychologist. (2015) 28(8):643–4. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/26984/

25. Boddington P, Raisanen U. Theoretical and practical issues in the definition of health: insights from aboriginal Australia. J Med Philos. (2009) 34(1):49–67. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhn035

26. Carnago L, O'Regan A, Hughes JM. Diagnosing and treating chronic pain: are we doing this right? J Prim Care Community Health. (2021) 12:21501327211008055. doi: 10.1177/21501327211008055

27. Zhang K, Hannan E, Scholes-Robertson N, Baumgart A, Guha C, Kerklaan J, et al. Patients’ perspectives of pain in dialysis: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Pain. (2020) 161(9):1983–94. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001931

28. Dudgeon P, Wright M, Paradies Y, Garvey D, Walker I. The social, cultural and historical context of aboriginal and torres strait islander Australians. In: The social, cultural and historical context of aboriginal and torres strait I slander Australians, in working together: Aboriginal and torres strait islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Canberra, A. C. T.: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2010:25–42.

29. Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. (2019) 123(2):e273–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.023

30. Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA, Smith SB, Slade GD. Overlapping chronic pain conditions: implications for diagnosis and classification. J Pain. (2016) 17(9 Suppl):T93–T107. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.06.002

31. Priest N, Thompson L, Mackean T, Baker A, Waters E. “Yarning up with koori kids” - hearing the voices of Australian urban indigenous children about their health and well-being. Ethn Health. (2017) 22(6):631–47. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2016.1246418

32. Shepherd SM, Spivak B, Arabena K, Paradies Y. Identifying the prevalence and predictors of suicidal behaviours for indigenous males in custody. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18(1):1159. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6074-5

33. Hackett RA, Ronaldson A, Bhui K, Steptoe A, Jackson SE. Racial discrimination and health: a prospective study of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20(1):1652. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09792-1

34. Biddle N, Priest N. The importance of reconciliation in education. CSRM WORKING PAPER NO. 1/2019: Centre for Social Research & Methods - Australian National University, retrieved at https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/research/publications; 2019.

35. Falls T, Anderson J. Attitudes towards aboriginal and torres strait islander peoples in Australia: a systematic review. Aust J Psych. (2022) 74(1):15. doi: 10.1080/00049530.2022.2039043

36. Potter L, Zawadzki MJ, Eccleston CP, Cook JE, Snipes SA, Sliwinski MJ, et al. The intersections of race, gender. Age, and socioeconomic Status: implications for reporting discrimination and attributions to discrimination. Stigma Health. (2019) 4(3):264–81. doi: 10.1037/sah0000099

37. Aronson J, Burgess D, Phelan SM, Juarez L. Unhealthy interactions: the role of stereotype threat in health disparities. Am J Public Health. (2013) 103(1):50–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300828

38. Robards F, Kang M, Steinbeck K, Hawke C, Jan S, Sanci L, et al. Health care equity and access for marginalised young people: a longitudinal qualitative study exploring health system navigation in Australia. Int J Equity Health. (2019) 18(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-0941-2

39. Butow P, Sharpe L. The impact of communication on adherence in pain management. Pain. (2013) 154(Suppl 1):S101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.048

40. Henry SG, Bell RA, Fenton JJ, Kravitz RL. Communication about chronic pain and opioids in primary care: impact on patient and physician visit experience. Pain. (2018) 159(2):371–9. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001098

41. Mittinty MM, McNeil DW, Jamieson LM. Limited evidence to measure the impact of chronic pain on health outcomes of indigenous people. J Psychosom Res. (2018) 107:53–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.02.001

Keywords: communication, Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, pain, access to healthcare

Citation: Bernardes CM, Houkamau K, Lin I, Taylor M, Birch S, Claus A, Bryant M, Meuter R, Isua J, Gray P, Kluver Joseph P, Jones C, Ekberg S and Pratt G (2022) Communication and access to healthcare: Experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people managing pain in Queensland, Australia. Front. Pain Res. 3:1041968. doi: 10.3389/fpain.2022.1041968

Received: 12 September 2022; Accepted: 14 November 2022;

Published: 6 December 2022.

Edited by:

Shivantika Sharad, University of Delhi, IndiaReviewed by:

Kshitija Wason, University of Delhi, IndiaAishwarya Jaiswal, Banaras Hindu University, India

© 2022 Bernardes, Houkamau, Lin, Taylor, Birch, Claus, Bryant, Meuter, Isua, Gray, Kluver, Jones, Ekberg and Pratt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christina Maresch Bernardes Y2hyaXN0aW5hLmJlcm5hcmRlc0BxaW1yYmVyZ2hvZmVyLmVkdS5hdQ==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Pain Research Methods, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pain Research

Christina Maresch Bernardes

Christina Maresch Bernardes Kushla Houkamau1

Kushla Houkamau1 Marayah Taylor

Marayah Taylor Renata Meuter

Renata Meuter Corey Jones

Corey Jones Stuart Ekberg

Stuart Ekberg