95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CORRECTION article

Front. Oncol. , 21 March 2025

Sec. Hematologic Malignancies

Volume 15 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2025.1559194

This article is a correction to:

Efficacy and survival outcome of allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: meta-analysis in the recent 10 years

A Corrigendum on

Efficacy and survival outcome of allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: meta-analysis in the recent 10 years

By Lin SY, Lu KJ, Zheng XN, Hou J and Liu TT (2024) Front. Oncol. 14:1341631. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1341631

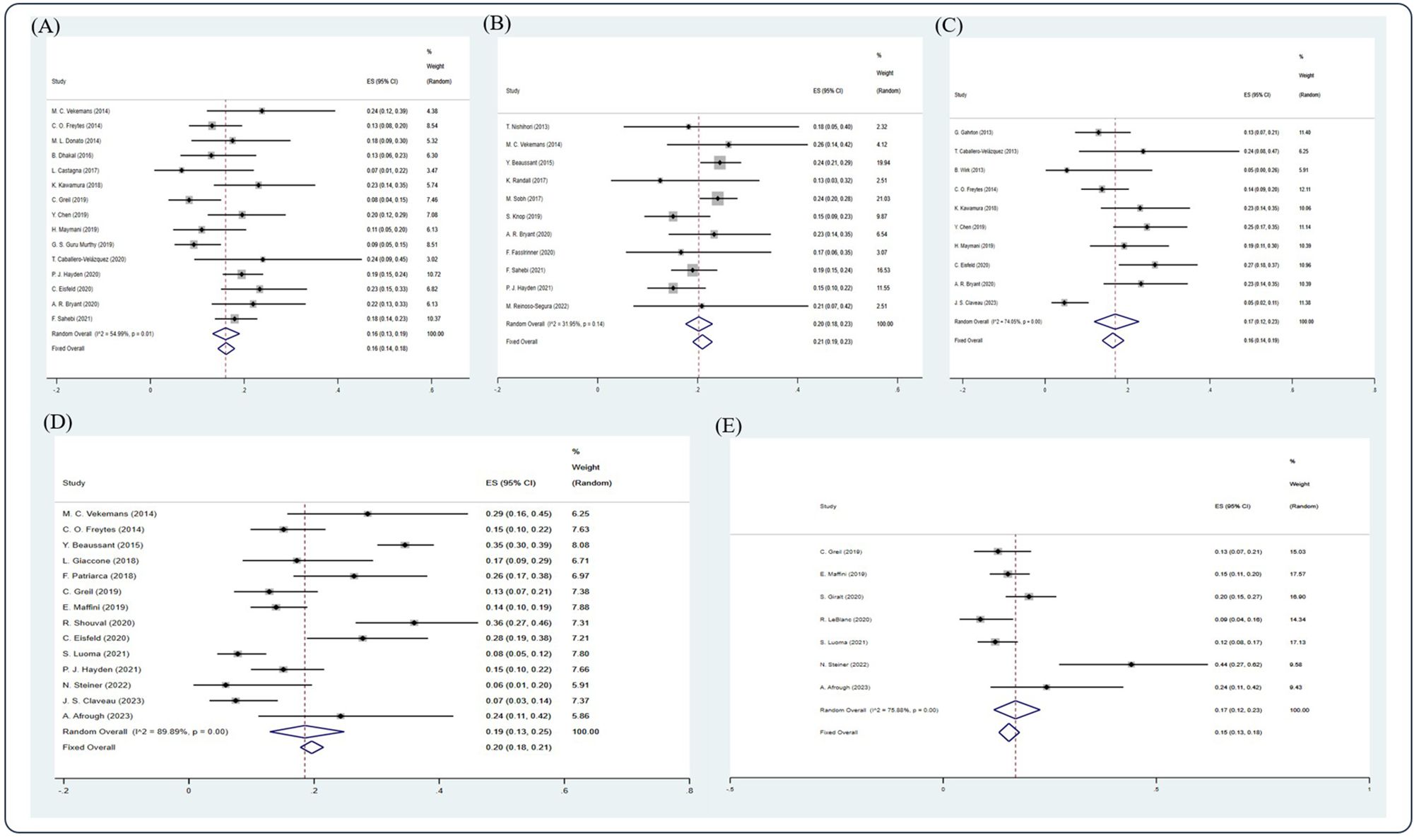

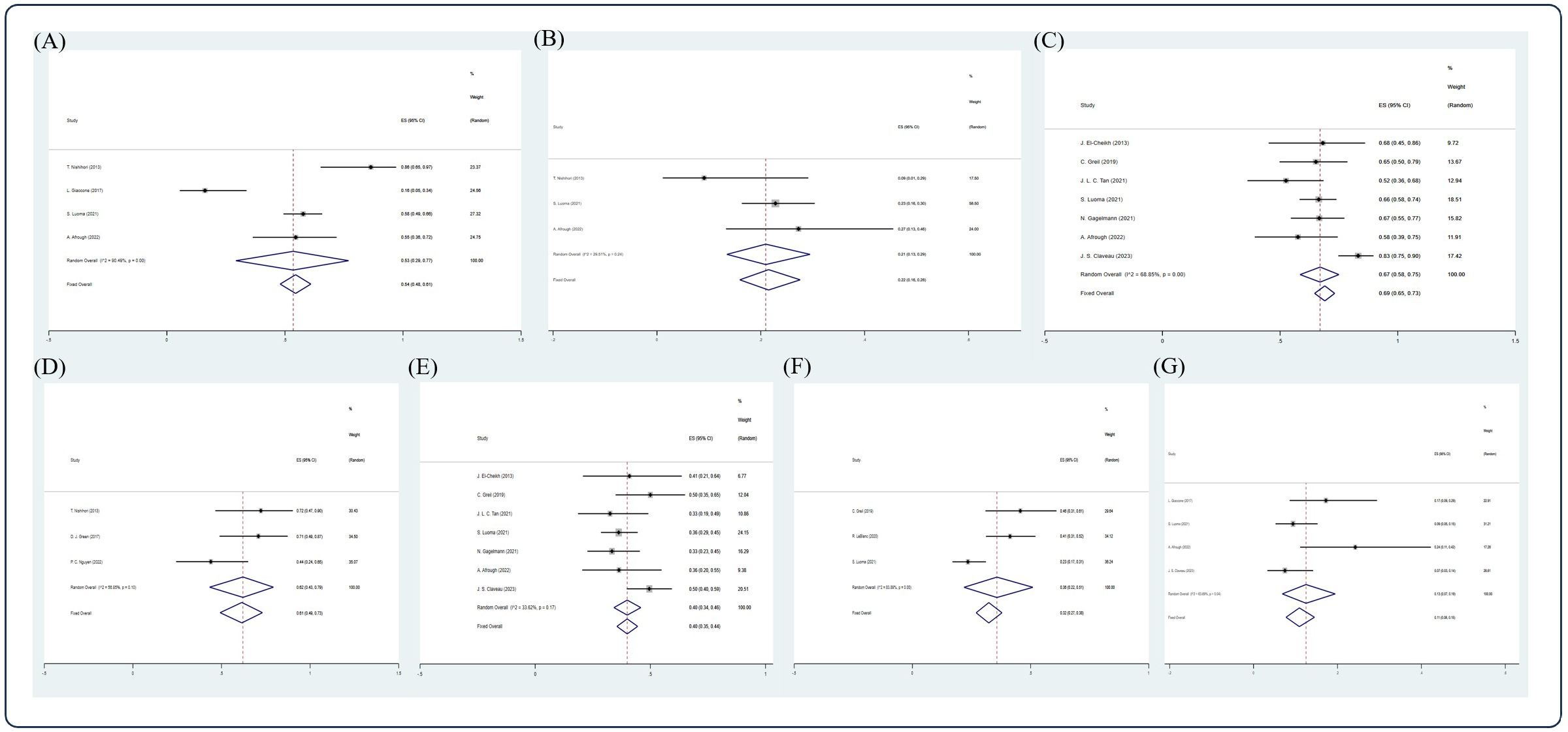

In the published article, there was an error in Figure 5 and Figure 6 as published. There was a tag on both figures. The corrected Figure 5 and Figure 6 and their captions appear below.

Figure 5. Forest plot of pooled weighted (A) 1-year, (B) 2-year, (C) 3-year, (D) 5-year, and (E) 10-year NRM based on the random-effect model.

Figure 6. Forest plot of pooled weighted (A) CR, (B) PR, (C) 5-year OS, (D) 2-year PFS, (E) 5-year PFS, (F) 10-year PFS, (G) 5-year NRM in NDMM/frontline setting based on random effect model.

The authors apologize for this error and state that this does not change the scientific conclusions of the article in any way. The original article has been updated.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, allogeneic stem cell transplantation, response rate, survival outcome, OS, PFS

Citation: Lin SY, Lu KJ, Zheng XN, Hou J and Liu TT (2025) Corrigendum: Efficacy and survival outcome of allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: meta-analysis in the recent 10 years. Front. Oncol. 15:1559194. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1559194

Received: 12 January 2025; Accepted: 03 March 2025;

Published: 21 March 2025.

Edited and Reviewed by:

Jacopo Mariotti, Humanitas Research Hospital, ItalyCopyright © 2025 Lin, Lu, Zheng, Hou and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ting Ting Liu, bGl1dGluZ3RpbmdfMDEzMUBzaW5hLmNvbQ==; Jian Hou, aG91amlhbkBtZWRtYWlsLmNvbS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.