94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol., 28 February 2025

Sec. Cancer Imaging and Image-directed Interventions

Volume 15 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2025.1486149

Objective: An effective model for risk stratification and prognostic assessment of early hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients following microwave ablation (MWA) is lacking in clinical practice. The aim of this study is to develop and validate a prognostic model specifically for these patients.

Methods: Between January 2008 and December 2018, 345 treatment-naïve patients with HCC conforming to the Milan criteria who underwent MWA were enrolled and randomly assigned to the training (n=209) and validation (n=136) cohorts. The nomogram model was constructed based on the predictors assessed by the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model and validated. Predictive accuracy and discriminative ability were further evaluated and compared with other prognostic models.

Results: After a median follow-up of 59.0 months, 52.5% (187/356) of the patients had died. Prognostic factors for overall survival (OS) were α-fetoprotein (AFP), albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score, platelets, and ablation margins, which generated the nomograms. The nomogram model consistently achieved good calibration and discriminatory ability with a concordance index of 0.64 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.59-0.69) and 0.69 (95% CI: 0.63-0.75) in both the training and validation cohorts. The performance of the nomogram model also outperformed other prognostic models. By using the nomogram model, the patient population could be correctly divided into low- and high-risk strata presenting significantly different median OS of 105.0 (95% CI: 84.1-125.9) months, and 45.0 (95% CI: 28.0-62.0) months, respectively.

Conclusion: The nomogram model based on AFP, PLT, ablation margins, and ALBI score was a simple visualization model that could stratify patients with early‐stage HCC after MWA and predict individualized long-term survival with favorable performance.

Although surgical resection (SR) remains the optimal treatment for patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and preserved liver function, microwave ablation (MWA) has also been used as a first-line treatment option for early HCC as recommended by guidelines due to its minimal invasiveness, good safety and excellent reproducibility (1–4). Studies comparing the outcomes of early patients with HCC treated with SR or MWA suggested that MWA offered comparable overall survival (OS) to SR (5–7). Although MWA shows promise in treating early-stage HCC, the 5-year survival rates of patients vary greatly, ranging from 37% to 90.9% (8–10). Therefore, risk stratification and prognostic evaluation are critical for early-stage HCC.

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system is the most relevant and extensively validated staging system for HCC. Although the BCLC system can stratify HCC risk at different stages, it may not be sufficient to provide a personalized long-term survival prediction (11, 12). Liver functional reserve is critical in predicting the prognosis of HCC. The Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) classification is the most commonly used liver function assessment. However, its predictive ability in HCC is poor and limited by the absence of cirrhosis in some patients with HCC (13). The albumin–bilirubin (ALBI) grade, a promising alternative to the CTP grade to evaluate liver function reserve, was found to be a prognostic factor for patients with HCC undergoing different treatment modalities. Platelet-albumin-bilirubin (PALBI) has shown superior accuracy compared to ALBI in predicting survival in patients with HCC, particularly in patients receiving more aggressive treatment (14). As ALBI and PALBI grades only focus on liver function parameters without tumor status, their value in personalized survival prediction is diminished (11).

The nomogram is a simple visualization tool that enables the creation of personalized prediction (15–17). Several nomogram models have been developed to predict the outcomes of patients with HCC after SR, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), or radiofrequency ablation (RFA), showing excellent discriminative ability compared with conventional staging methods (13, 16, 18, 19). Nomogram models to predict tumor recurrence after MWA for early-stage HCC have also been reported (3, 20). Furthermore, one study reported that a nomogram model could predict the long-term survival of patients with recurrent HCC who underwent MWA (21). Two studies have reported predictive models for the long-term survival of patients with early HCC following MWA, but one included only elderly patients and the other focused on patients with HCV-associated HCC (20, 22).

In the present study, we developed and validated a nomogram model for risk stratification and personalized survival prediction for patients with early HCC after MWA.

We conducted a retrospective study of patients with HCC initially treated with MWA at XiJing hospital between January 2008 and December 2018. This study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital, and patients’ written consent for inclusion was waived. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) solitary HCC ⩽5.0 cm in diameter, or two to three HCC tumors, each ⩽3.0 cm in diameter according to the Milan criteria; 2) no radiological evidence of extrahepatic metastasis or major vascular invasion; 3) Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) class A or B liver function; 4) no previous treatment for HCC. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) recurrent HCC; 2) combined with other malignancies; 3) loss to follow-up within 1 month after MWA; 4) other anti-cancer treatment after MWA.

Clinical and demographic data were retrieved from medical records, such as age, sex, tumor size, tumor number, comorbidity, BCLC staging, CTP grade, albumin, total bilirubin, platelet count (PLT), international normalized ratio (INR), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, creatinine, ALBI score (14), α-fetoprotein (AFP), AST-to-PLT ratio index (APRI), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and PALBI score (14).

MWA was performed as previously reported (23). All MWA procedures were performed by experienced interventional radiologists. The MWA system consisted of a monopole microwave antenna and a water-cooled microwave device (ECO-100, ECO Microwave Electronic Institute; KY-2000, Kangyou Medical Instrument) (14 G). A rational MWA scheme was designed based on the findings of enhanced computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. An ideal ablative margin was achieved to completely cover the tumor and surrounding tumor edge (≥0.5 cm), with the exception of margins situated in difficult locations—large vessels, gallbladder, or bile ducts—where individual MWA procedures were performed with the intention of minimizing the potential damage (5, 10, 24).

After the administration of local anesthesia, the MWA antenna was inserted under US guidance and introduced into the tumor to reach its deep margin. To achieve complete ablation, multiple overlapping ablation approaches were applied to the tumors. When the deep lesion site and every area of the targeted tumor were covered by hyperechoic regions on the US, the procedure was terminated. The ablation area covering the tumor and its surrounding area measured at least 0.5–1.0 cm as a “safety margin.” This measurement was determined by comparing the diameter of the hyperechoic regions after the procedure with the diameter of the tumors before treatment (25).

One month after MWA treatment, all patients underwent contrast-enhanced CT or MRI to evaluate the technical success rate and ablation margins. After the initial CT scan, patients were subsequently followed up every 3 to 6 months until death or loss of follow-up. Each follow-up visit included a physical examination, liver function tests, AFP and at least one imaging examination (abdominal contrast-enhanced CT or MRI). Patients with elevated AFP or suspicious lesions on US screening were examined by contrast-enhanced CT or MRI to confirm tumor recurrence. Nodules with equivocal imaging findings were biopsied. Patients who did not visit our hospital as scheduled were telephoned for follow-up to obtain the imaging examination, treatment information and living status. The primary endpoint of the study was OS, which was defined as the interval between the first MWA and all-cause death or the final follow-up date of 31 December 2023.

Quantitative variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Student t-test or non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, whereas categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Only variables associated with a p<0.1 identified by the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to identify the independent predictors of OS after multiple imputations for missing values.

The nomogram model was then developed using a combination of backward procedure and forward stepwise elimination techniques and Akaike’s information criteria. The variance inflation factor and correlation statistics were used to evaluate collinearity between the variables. To account for nonlinearity, continuous variables were fitted using restricted cubic splines. The Hosmer−Lemeshow test and coefficient of determination (R2) were used to identify the goodness of fit of the nomogram model. The area under the time-dependent receiving operator characteristic curve (AUROC), concordance index (C-index) and calibration curve were used to assess the predictive accuracy and discriminative ability of the nomogram model. To reflect the clinical utility and net benefit of the model to patients, decision curve analysis (DCA) was also performed using the source file “stdca.R.” These activities utilized bootstrapping with 1000 replications. In both the training and validation cohorts, the nomogram model was compared with other prognostic models such as the BCLC staging system (11), ALBI grade (14, 26), PALBI grade (14), and NLR (27). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 4.1.3 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with rms, pROC and ggplot2. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant for differences.

A total of 345 patients with HCC were finally enrolled and randomly assigned to the training (n=209) and validation (n=136) cohorts in a 6:4 ratio using computer-generated randomization (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics and follow-up data were comparable between the two cohorts (all p-values>0.05) (Table 1). The 97.6% technical success rate in the training cohort was comparable to the 97.8% technique success rate in the validation cohort (p=0.910). After a median follow-up of 90.0 (IQR: 70.0-115.0) months, 120 (57.4%) patients in the training cohort and 69 (50.7%) patients in the validation cohort died. The OS rates had no statistically significant differences in the training and validation cohorts (p=0.263).

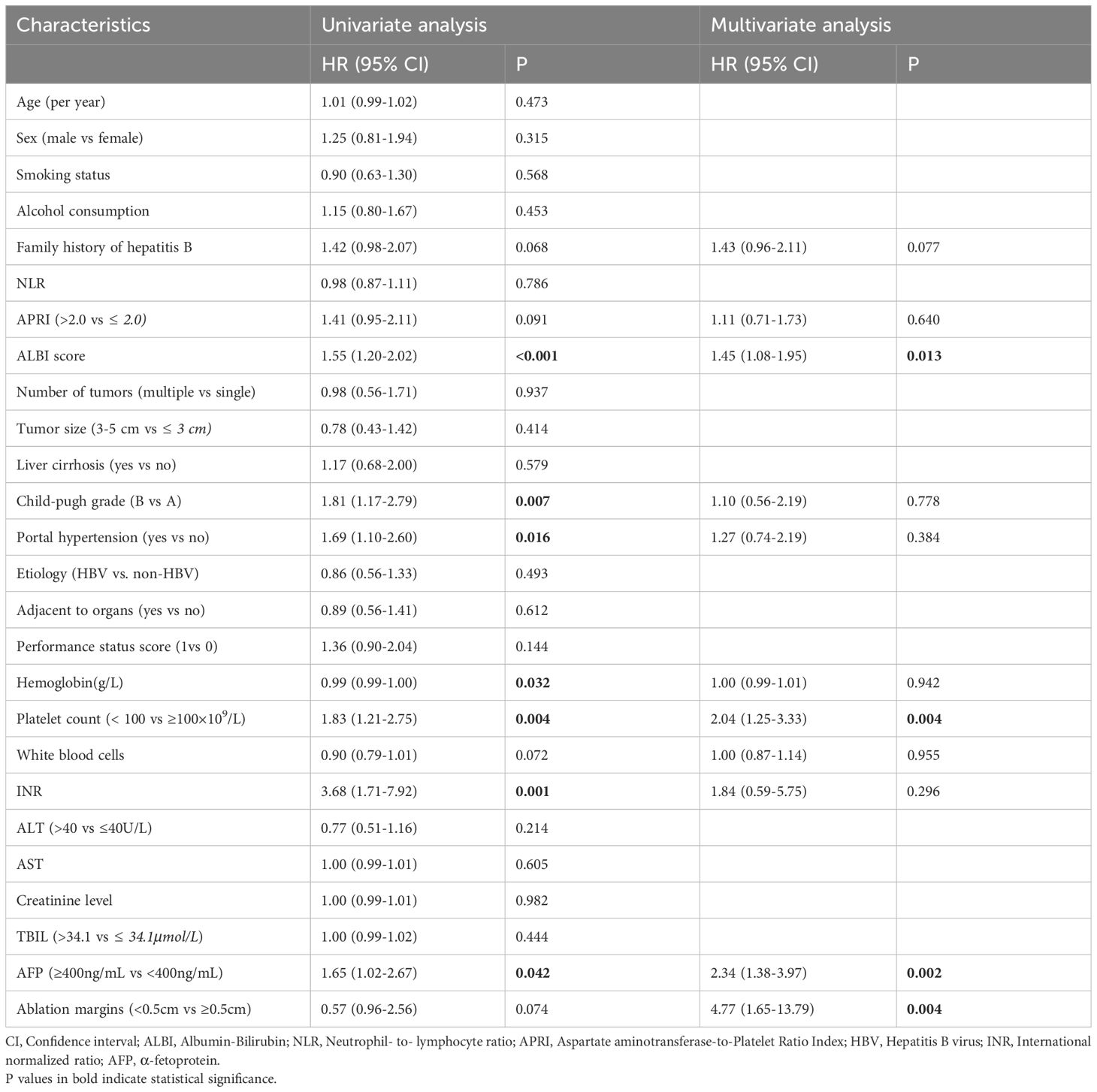

The multivariate Cox regression analyses after multiple imputation suggested that AFP level (hazard ratio (HR), 2.38; 95% CI: 1.41-4.01, p=0.007), ALBI score (HR, 1.50; 95% CI: 1.19-2.02, P=0.007), ablation margins (HR, 4.14; 95% CI: 1.46-11.73, P=0.007) and PLT level (HR, 1.97; 95% CI: 1.23-3.20, p=0.006) were independent prognostic factors associated with OS (Table 2). Restrictive cubic spline functions showed that the ALBI score presented a non-linear profile in the training and validation cohorts (non-linearity p-values: 0.016 and 0.034, respectively) (Supplementary Figures S1A, B). A nomogram model was developed to predict the 3- and 5-year OS rates based on the identified prognostic factors (Figure 2). The survival probability of individual patients at different time points after MWA could be predicted with the sum of the scores for the four factors on the point scale.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate Cox analysis of risk factors associated with overall survival in the training cohort.

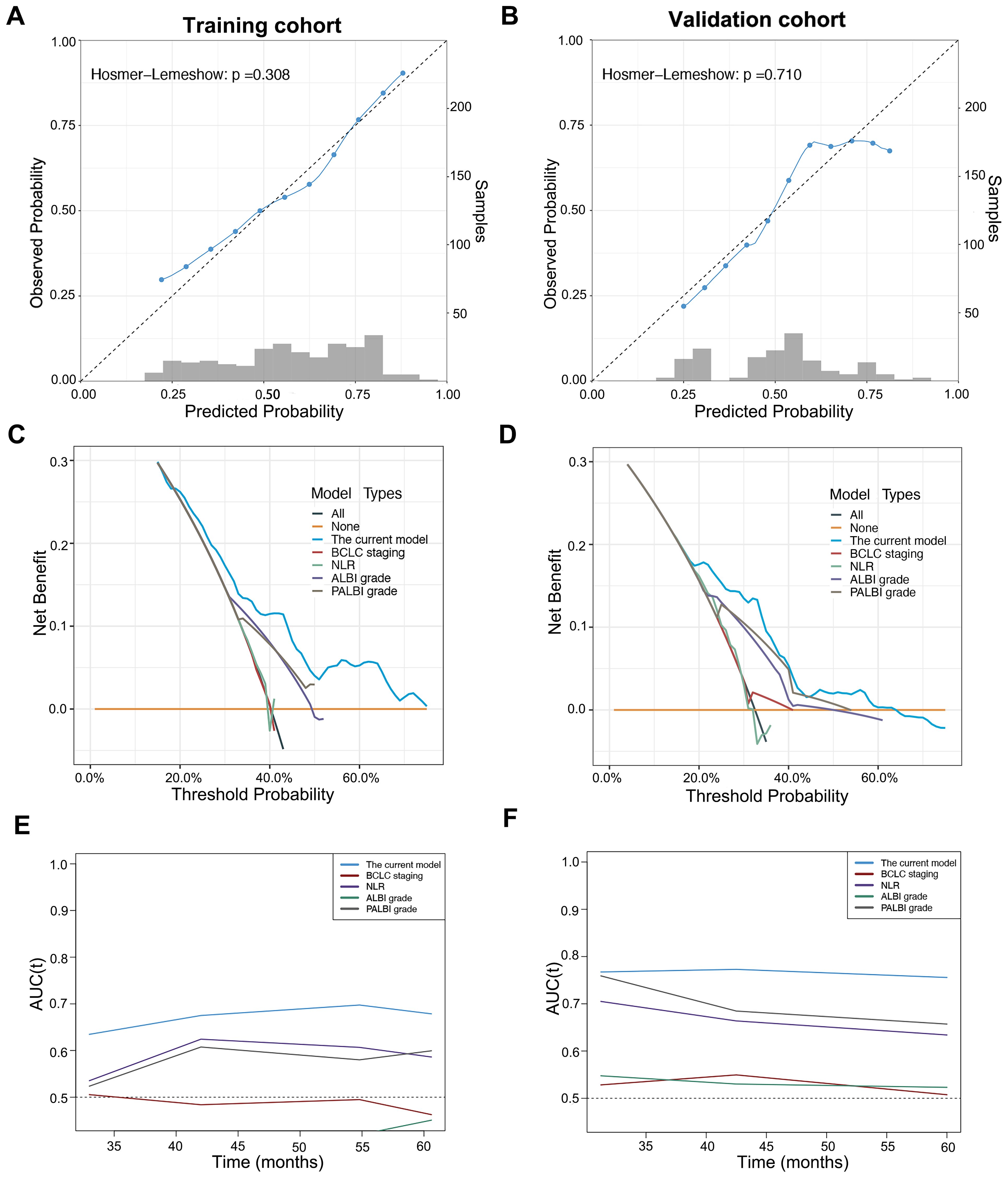

The C-index value of the current model for OS prediction was 0.64 and 0.69, respectively, in the training and validation cohorts and the calibration curves were close to the ideal diagonal line (Figures 3A, B). DCA demonstrated a higher net benefit of the current model than other prognostic models (Figures 3C, D). Additionally, the Hosmer−Lemeshow test confirmed that the current model was a good fit (p=0.308 and p=0.710 in the training and validation cohorts, respectively). The performance and discriminative ability of the current model were compared with other prognostic models, such as the ALBI grade, PALBI grade, BCLC staging system and NLR. The 3- and 5-year AUROC values and the C-index of the current model were higher than other prognostic models, which remained consistent in the validation cohort, indicating good performance and discriminative ability (Table 3, Figures 3E, F).

Figure 3. Calibration curve, decision curve analysis and time-dependent area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of the current model in patients with early-stage HCC after microwave ablation. Calibration curve of the current model in the training cohort (A) and validation (B) cohort. Decision curve analysis of the current model compared with other prognostic models in the training cohort (C) and validation cohort (D). Time-dependent AUROC values of the current model compared with other prognostic models in the training cohort (E) and validation cohort (F).

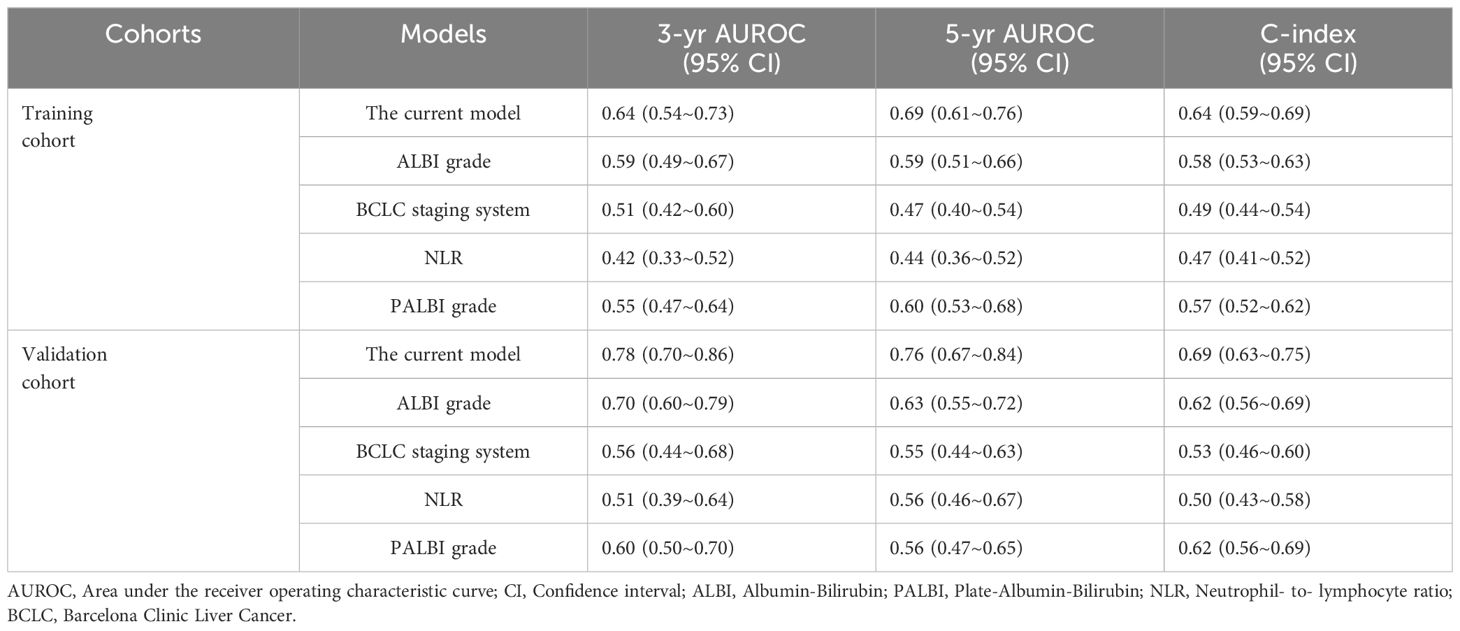

Table 3. Comparison of performance and discriminative ability between the current model and other prognostic models.

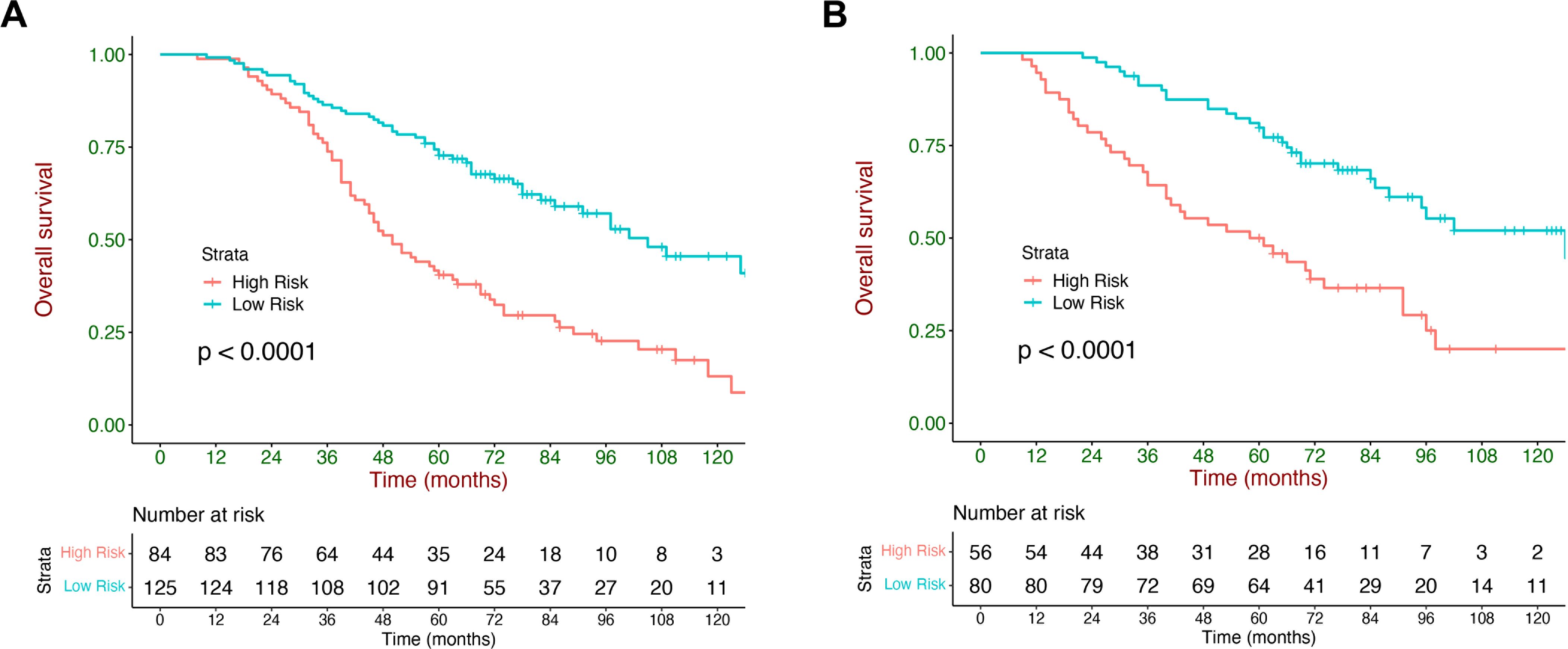

The X-tile was adopted to generate an optimal cutoff value (87), which divided the validation cohort into 2 strata with a highly different survival probability: low-risk (score <87, n=80) and high-risk (score ≥87, n=56). The median OS of the low- and high-risk strata was 126.0 (95% CI: 75.2-176.9) months and 58.0 (95% CI: 33.6-82.4) months, respectively. The survival curves were significantly different between the two strata in the training and validation cohorts (p <0.001, Figures 4A, B).

Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier overall survival (OS) curves stratified by the current model. Kaplan–Meier curves of OS stratified by the current model in the training cohort (A) and validation (B) cohort.

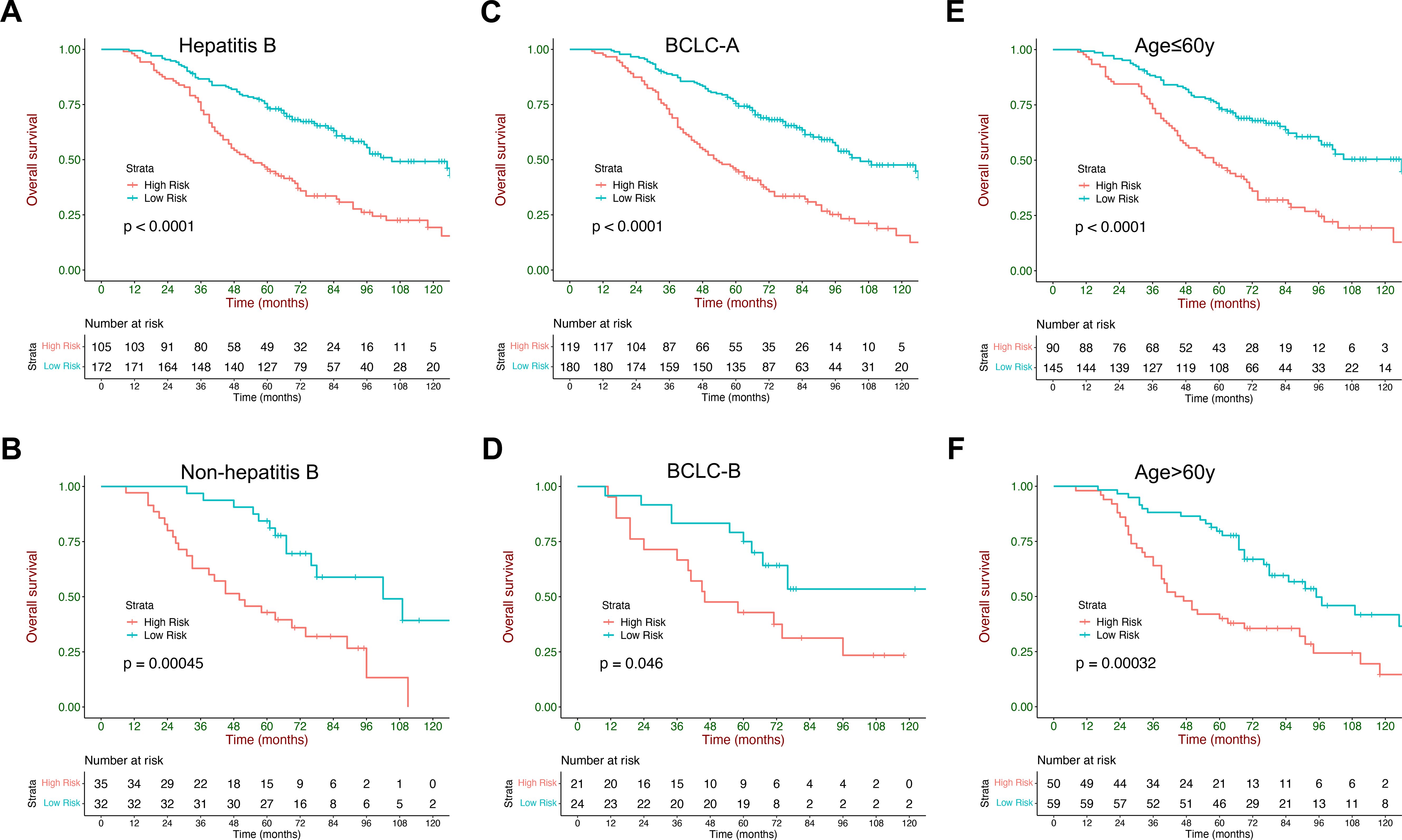

The current model could also stratify patients with HCC into low- and high-risk strata across subgroups with different etiologies (HBV and other etiology), age (≤60 y and >60 y), and BCLC staging system (A and B), and exhibited consistent performance in these populations (Figure 5). Rates of BCLC stage A and B within each stratum are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Median survival and HRs with 95% CI of the low- and high-risk strata in different subgroups are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 5. Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival stratified by the current model in subgroups: (A, B) different etiologies (HBV and other etiology), (C, D) ages (<60 y and ≥60 y), (E, F) and sex (female subjects and male subjects).

In this retrospective observational study, we developed and validated a nomogram model including 4 items (AFP, ALBI score, ablation margins and PLT) to predict the individual outcomes in patients with early HCC after MWA. The nomogram model could accurately stratify patients into two prognostic strata with significantly distinct OS. The nomogram model showed good performance and discriminative ability and outperformed other prognostic models in predicting the long-term survival of patients with early HCC. The strength and novelty of this study lie in:1) developing the first prognostic model specifically for patients with HCC after MWA rather than unrelated to therapy; 2) The predictors are objective, routinely available and easily measured; and 3) The nomogram could be easily applied for individual survival prediction and risk stratification.

To date, some factors associated with poor outcomes in ablation have been reported. The most consistently demonstrated risk factors for poor OS included liver dysfunction, high AFP level and low PLT count. Compared with advanced tumor stages, liver function reserve is more important in patients with early HCC (13). ALBI grade incorporating both serum albumin and bilirubin could be a simple and objective method to evaluate liver function with good performance in patients with HCC. ALBI grade could predict the survival of patients with HCC across different BCLC staging and treatment modalities (14). According to previous studies, ALBI grade has been identified as a categorical predictor of long-term survival before ablation (13, 21). However, few patients with early-stage HCC had ALBI grade 3, which might weaken the statistical power of the nomogram, especially when the number of patients with ALBI grade 3 was small (13). In the present study, only 12 patients with HCC were in ALBI grade 3. Therefore, we used the ALBI score rather than the ALBI grade as a prognostic component. In recent years, the ablation margins, defined as the minimal margin distance that is measured between the area of tissue necrosis and the tumor edge, has been proposed as an independent prognostic factor (28). Recently published retrospective studies reported insufficient ablative margin as an important therapeutic predictor of mortality after ablation (28, 29), while ablative margin ≥5 mm could improve the survival outcomes (30). In the present study, we identified ALBI score, AFP, PLT, and ablation margins as the independent prognostic factors for OS.

Based on these factors, we developed a nomogram model to predict the 3- and 5-year survival in patients with early HCC after MWA. The performance and discriminative ability of the nomogram model was higher than that of other prognostic models, which was confirmed in the validation cohort. In terms of risk stratification, by forming low-risk (score <87) and high-risk (score ≥87) groups, the nomogram model could provide the survival probability prediction at different time points and divide the risk stratification with distinct OS, which was essential for the implementation of a surveillance program after MWA.

The BCLC staging system has been extensively validated and recommended for prognostic prediction and treatment allocation of HCC. However, the BCLC system is unable to stratify the survival probability of patients undergoing identical treatment. This BCLC staging system was less effective than our nomogram model in predicting OS (C-index: 0.53 vs 0.69), and its discriminative ability was less useful for patients with early HCC after MWA. Our nomogram model could differentiate BCLC A or B patients into low- and high-risk groups. The data implied that not every BCLC A or B patient was the same. The heterogeneity in early-stage HCC harbors the potential to alter HCC prognosis and surveillance strategy. For example, 40% of BCLC stage A patients and 44.5% of BCLC stage B patients were classified as high-risk strata; these patients can be considered to have similar OS rates. In addition, we also analyzed the discriminative ability of the nomogram model in patients with different ages and etiologies and found that these patients could also be divided into two strata with different OS. This result indicated that our nomogram model had a stable predictive ability of survival outcomes for patients with early-stage HCC after MWA and had great potential applications in clinical practice.

Tumor recurrence is also a critical concern that heavily influences the long-term survival of patients with HCC. We also performed multivariate analyses on factors affecting HCC recurrence. We found that only 2 factors, ablation margins and AFP level, were independent predictors of tumor recurrence (Supplementary Table S3). However, these two factors were not included in the nomogram model due to a lack of predictive power for survival. A possible explanation for this may be that patients with HCC underwent regular follow-up after MWA, and the majority of recurrent HCC were at an early stage, which could be treated with potentially curative methods.

For clinical application, our nomogram model could predict individualized long-term survival after MWA. This is of great importance for clinical practice. The model could identify those at high risk for poor clinical outcomes and help design an optimal surveillance strategy. A recent study evaluated the efficacy of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in preventing recurrence of HCC in patients at high risk of recurrence after curative-intent resection or ablation and found that adjuvant therapy improved recurrence-free survival (31). With the current model, randomized controlled trials could be designed to see whether adjuvant therapy could improve overall survival in patients after MWA after stratification for long-term survival.

There are several limitations to our study. First, as a single-center retrospective study in an area where HBV is prevalent, selection bias could not be completely avoided. Although subgroup analysis by etiology suggested that our nomogram model could be effective for patients other than HBV-related HCC, its prognostic value in patients with HCC with other etiologies needs to be validated by further studies. Second, the samples from the current cohort could only be regarded as representative of the northwestern region of China, therefore a multi-center prospective study should be conducted to evaluate the prognostic accuracy. Third, our study was limited by the lack of CT and 3D software evaluation of the ablation margins, which have been demonstrated to be more accurate in assessing the successful treatment of MWA (32, 33). Finally, because this study was retrospectively designed, it is inevitable that there would be OS confounders and insufficient adherence to the follow-up protocol after MWA.

In conclusion, we developed and validated a nomogram model including AFP, PLT, ablation margins and ALBI score that could perform risk stratification and predict individual survival of early HCC patients after MWA with favorable performance and discrimination. Further validation in patients with different etiologies is still needed.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Department of Gastroenterology, XiJing Hospital. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the corresponding authors with the permission of XiJing hospital. Requests to access the datasets should be directed toemhvdXhtbUBmbW11LmVkdS5jbg==.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of XiJing hospital, and patient written consent for inclusion was waived. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because This is a retrospective observational cohort study. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

JZ: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. GG: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. TL: Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. CG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YH: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi (No. 2022ZDLSF03-03, No. 2023-ZDLSF-33) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81820108005).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1486149/full#supplementary-material

SR, surgical resection; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MWA, microwave ablation; OS, overall survival; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; EASL, European Association for the Study of Liver; AASLD, American Association for the study of Liver Disease; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; PLT, platelet count; INR, international normalized ratio; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; AFP, α-fetoprotein; APRI, AST-to-PLT ratio index; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PALBI, platelet-albumin-bilirubin; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; IQR, interquartile range.

1. Bailey CW, Sydnor MK Jr. Current state of tumor ablation therapies. Dig Dis Sci. (2019) 64:951–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05514-9

2. Yu J, Liang P. Status and advancement of microwave ablation in China. Int J Hyperthermia. (2017) 33:278–87. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2016.1243261

3. An C, Wu S, Huang Z, Ni J, Zuo M, Gu Y, et al. A novel nomogram to predict the local tumor progression after microwave ablation in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: A tool in prediction of successful ablation. Cancer Med. (2020) 9:104–15. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2606

4. European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. (2018) 69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019

5. Zhou Y, Yang Y, Zhou B, Wang Z, Zhu R, Chen X, et al. Challenges facing percutaneous ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: extension of ablation criteria. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. (2021) 8:625–44. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S298709

6. Liu W, Zou R, Wang C, Qiu J, Shen J, Liao Y, et al. Microwave ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity-score analysis. Ther Adv Med Oncol. (2019) 11:1–13. doi: 10.1177/1758835919874652

7. Shin SW, Ahn KS, Kim SW, Kim TS, Kim YH, Kang KJ. Liver resection versus local ablation therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. (2021) 273:656–66. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004350

8. Cheung TT, Ma KW, She WH. A review on radiofrequency, microwave and high-intensity focused ultrasound ablations for hepatocellular carcinoma with cirrhosis. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. (2021) 10:193–209. doi: 10.21037/hbsn.2020.03.11

9. Santambrogio R, Chiang J, Barabino M, Meloni FM, Bertolini E, Melchiorre F, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic microwave to radiofrequency ablation of small hepatocellular carcinoma (</=3 cm). Ann Surg Oncol. (2017) 24:257–63. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5527-2

10. Liu W, Zheng Y, He W, Zou R, Qiu J, Shen J, et al. Microwave vs radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria: a propensity score analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2018) 48:671–81. doi: 10.1111/apt.2018.48.issue-6

11. Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. (2018) 391:1301–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2

12. Xie DY, Ren ZG, Zhou J, Fan J, Gao Q. 2019 Chinese clinical guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: updates and insights. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. (2020) 9:452–63. doi: 10.21037/hbsn-20-480

13. Kao WY, Su CW, Chiou YY, Chiu NC, Liu CA, Fang KC, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: nomograms based on the albumin-bilirubin grade to assess the outcomes of radiofrequency ablation. Radiology. (2017) 285:670–80. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162382

14. Liu PH, Hsu CY, Hsia CY, Lee YH, Chiou YY, Huang YH, et al. ALBI and PALBI grade predict survival for HCC across treatment modalities and BCLC stages in the MELD Era. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2017) 32:879–86. doi: 10.1111/jgh.2017.32.issue-4

15. Iasonos A, Schrag D, Raj GV, Panageas KS. How to build and interpret a nomogram for cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. (2008) 26:1364–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9791

16. Ni JY, Fang ZT, Sun HL, An C, Huang ZM, Zhang TQ, et al. A nomogram to predict survival of patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma after transarterial chemoembolization combined with microwave ablation. Eur Radiol. (2020) 30:2377–90. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06438-8

17. Tattersall HL, Callegaro D, Ford SJ, Gronchi A. Staging, nomograms and other predictive tools in retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Chin Clin Oncol. (2018) 7:36. doi: 10.21037/cco.2018.08.01

18. Wang Q, Xia D, Bai W, Wang E, Sun J, Huang M, et al. Development of a prognostic score for recommended TACE candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicentre observational study. J Hepatol. (2019) 70:893–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.013

19. Shim JH, Jun MJ, Han S, Lee YJ, Lee SG, Kim KM, et al. Prognostic nomograms for prediction of recurrence and survival after curative liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. (2015) 261:939–46. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000747

20. An C, Li X, Yu X, Cheng Z, Han Z, Liu F, et al. Nomogram based on albumin-bilirubin grade to predict outcome of the patients with hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after microwave ablation. Cancer Biol Med. (2019) 16:797–810. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2018.0486

21. Qi C, Li S, Zhang L. Development and validation of a clinicopathological-based nomogram to predict the survival outcome of patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy who underwent microwave ablation. Cancer Manag Res. (2020) 12:7589–600. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S266052

22. Huang Z, Gu Y, Zhang T, Wu S, Wang X, An C, et al. Nomograms to predict survival outcomes after microwave ablation in elderly patients (>65 years old) with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Hyperthermia. (2020) 37:808–18. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2020.1785556

23. Hu H, Chi JC, Liu R, Zhai B. Microwave ablation for peribiliary hepatocellular carcinoma: propensity score analyses of long-term outcomes. Int J Hyperthermia. (2021) 38:191–201. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2019.1706766

24. Kuroda H, Nagasawa T, Fujiwara Y, Sato H, Abe T, Kooka Y, et al. Comparing the safety and efficacy of microwave ablation using thermosphere(TM) technology versus radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity score-matched analysis. Cancers (Basel). (2021) 13:1–13. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061295

25. Chu HH, Kim JH, Kim PN, Kim SY, Lim YS, Park SH, et al. Surgical resection versus radiofrequency ablation very early-stage HCC (</=2 cm Single HCC): A propensity score analysis. Liver Int. (2019) 39:2397–407. doi: 10.1111/liv.14258

26. Chong CC, Chan AW, Wong J, Chu CM, Chan SL, Lee KF, et al. Albumin-bilirubin grade predicts the outcomes of liver resection versus radiofrequency ablation for very early/early stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgeon. (2018) 16:163–70. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2017.07.003

27. Wang C, He W, Yuan Y, Zhang Y, Li K, Zou R, et al. Comparison of the prognostic value of inflammation-based scores in early recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Liver Int. (2020) 40:229–39. doi: 10.1111/liv.14281

28. Verdonschot KHM, Arts S, Van den Boezem PB, de Wilt JHW, Futterer JJ, Stommel MWJ, et al. Ablative margins in percutaneous thermal ablation of hepatic tumors: a systematic review. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. (2023) 23:977–93. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2023.2247564

29. Teng W, Liu KW, Lin CC, Jeng WJ, Chen WT, Sheen IS, et al. Insufficient ablative margin determined by early computed tomography may predict the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. Liver Cancer. (2015) 4:26–38. doi: 10.1159/000343877

30. Liao M, Zhong X, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhu Z, Wu H, et al. Radiofrequency ablation using a 10-mm target margin for small hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis: A prospective randomized trial. J Surg Oncol. (2017) 115:971–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.v115.8

31. Qin S, Chen M, Cheng AL, Kaseb AO, Kudo M, Lee HC, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus active surveillance in patients with resected or ablated high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma (IMbrave050): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2023) 402(10415):1835–1847. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01796-8

32. Long H, Zhou X, Zhang X, Ye J, Huang T, Cong L, et al. 3D fusion is superior to 2D point-to-point contrast-enhanced US to evaluate the ablative margin after RFA for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Radiol. (2023) 34(2):1247–1257. doi: 10.1007/s00330-023-10023-5

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, early stage, microwave ablation, overall survival, nomogram

Citation: Zhang J, Guo G, Li T, Guo C, Han Y and Zhou X (2025) Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for early hepatocellular carcinoma treated with microwave ablation. Front. Oncol. 15:1486149. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1486149

Received: 25 August 2024; Accepted: 06 February 2025;

Published: 28 February 2025.

Edited by:

Sharon R Pine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, United StatesReviewed by:

Sarah Allegra, San Luigi Gonzaga University Hospital, ItalyCopyright © 2025 Zhang, Guo, Li, Guo, Han and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinmin Zhou, emhvdXhtbUBmbW11LmVkdS5jbg==; Ying Han, aGFueWluZzFAZm1tdS5lZHUuY24=; Changcun Guo, Z3VvY2hjQHNpbmEuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.