94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol., 02 December 2024

Sec. Cancer Molecular Targets and Therapeutics

Volume 14 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1502819

This article is part of the Research TopicNovel Molecular Targets in Cancer TherapyView all 28 articles

Sunanda Kulshrestha1

Sunanda Kulshrestha1 Anjana Goel1*

Anjana Goel1* Subhadip Banerjee2

Subhadip Banerjee2 Rohit Sharma3

Rohit Sharma3 Mohammad Rashid Khan4

Mohammad Rashid Khan4 Kow-Tong Chen5,6*

Kow-Tong Chen5,6*Introduction: Cancer has emerged as one of the leading causes of fatality all over the world. Phytoconstituents are being studied for their synergistic effects, which include disease prevention by altering molecular pathways and immunomodulation without side effects. The present experiment aims to explore the cancer preventive activities of Argemone mexicana Linn leaves extract in skin cancer cell lines (A431) and colon cancer cell lines (COLO 320DM)). In addition, TNF-α expression patterns and NF-kB signaling pathways have been examined.

Methods: LC/MS study of Argemone mexicana Linn extracts in various solvents revealed anti-cancerous phytoconstituents. Network pharmacology analysis used Binding DB, STRING, DAVID, and KEGG for data mining to evaluate predicted compounds using functional annotation analysis. Cytoscape 3.2.1 created “neighbourhood approach” and networks. The MNTD of these extracts was tested on L929 fibroblasts. Skin cancer (A431) and colon cancer (COLO 320DM) cell lines were tested for IC50 inhibition. Evaluation of TNF-α and NF-kB expression in cell culture supernatants and homogenates reveals anti-cancerous effects.

Results: LC-MS analysis of extracts predicted the presence of anticancer alkaloids Berberine, Atropine, Argemexicin, and Argemonin. In Network pharmacology analysis, enrichment was linked to the PI3-AKT pathway for both cancer types. MNTD was calculated at 1000μg/ml in L929. The ethanolic extract at 1000μg/ml significantly inhibited skin cancer cell proliferation by 67% and colon cancer cells by 75%. Ethanolic extract significantly reduced TNF-α expression in both cell lines (p<0.001), with the highest inhibition at 1000μg/ml. In TNF-α stimulated cell lines, 1000μg/ml ethanolic extract significantly reduced the regulation of the NF-kB pathway, which plays a role in cancer progression (p<0.001).

Conclusion: Argemone mexicana Linn. known as ‘swarnkshiri’ in Ayurveda has been reported to be used by the traditional healers for the treatment of psoriasis and its anti-inflammatory and anti-cancerous properties, according to the Indian Medicinal Plant dictionary. In the experiment, the abatement in the expression of inflammatory cytokine TNF-α and inhibition of NF-kB transcription factor activation could be linked with the downregulation of cancer cell proliferation. The study revealed the anticancer activity of Argemone mexicana Linn in the cancer cell lines and paved a pathway for molecular approaches that could be explored more in In vivo studies.

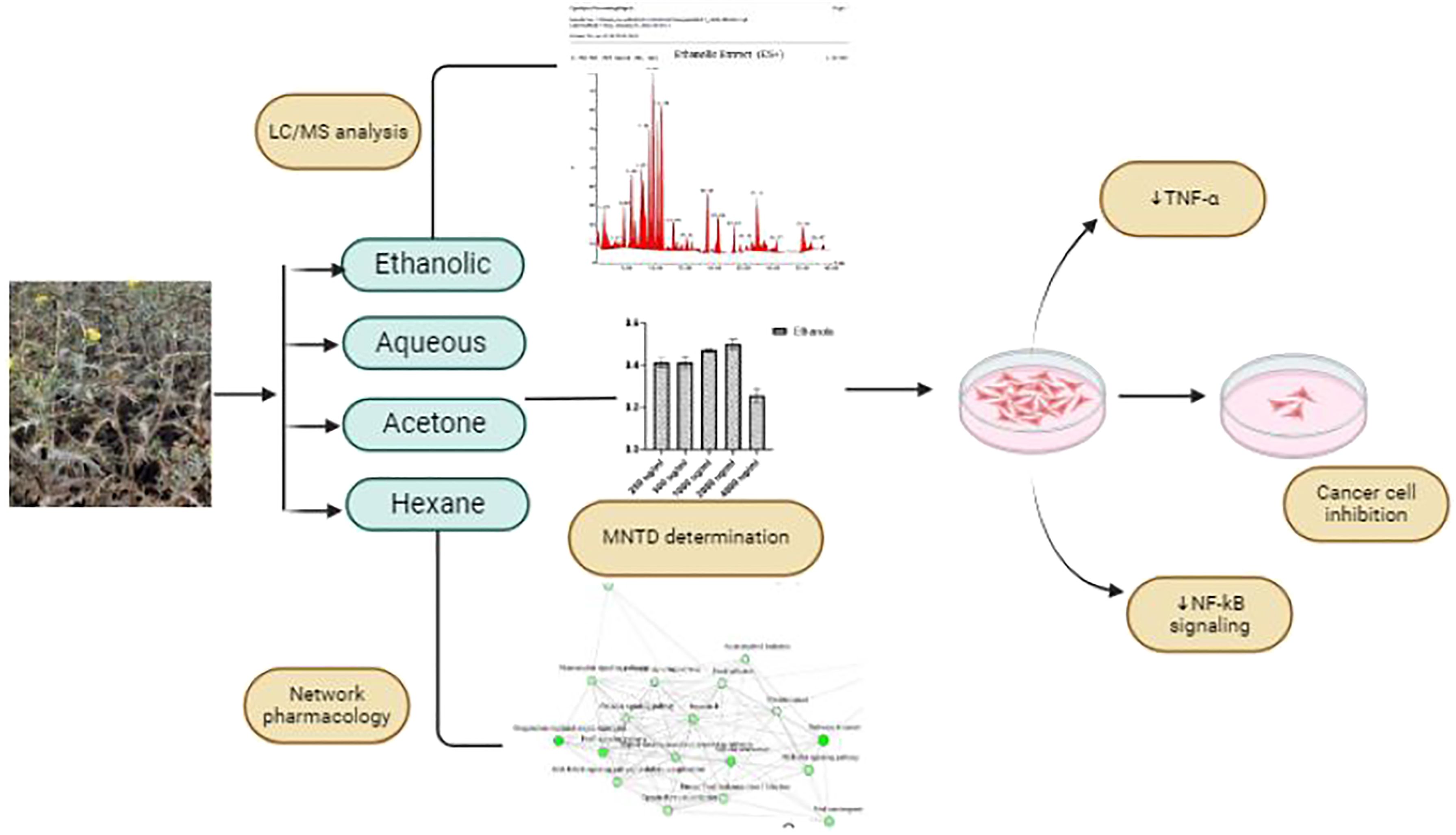

Graphical Abstract. Assessment of anti-cancerous activity of Argemone mexicana by its leaf extracts on skin and colon cancer cell lines using network pharmacology in conjunction with research into the regulatory patterns of TNF-α and NF-kB.

● Argemone mexicana Linn. is known for its anti-inflammatory properties.

● Ethnomedicinal use of the plant is employed to treat skin diseases like psoriasis.

● LC/MS analysis of extracts was followed by network pharmacology studies.

● 1,000 µg/ml of the ethanolic extract exhibited significant anticancer effect in cell lines.

● Downregulation in TNF-α and NF-kB was observed by ethanolic extract at the same dose.

Cancer is prominent worldwide, leading to an increased burden on healthcare and the economy of any country (1). The number of cases of cancer is increasing at an exponential rate because of prolonged exposure to carcinogens, UV light, genetic factors, eating habits, and stagnant lifestyles, which lead to a suppressed immunity population and give a niche for the development of such disorders (2).

Skin cancer is one of the most prominent cancers in the world accounting for 2–3 million cases diagnosed in the world in the past 5 years. With 1,08,270 new cases and 4,420 deaths all over the world, making it the fifth most common cancer in the world, and in turn a burden on the economy of any country (1). Apart from this, with an estimated 106,590 new cases and 53,010 cancer deaths per year, colorectal cancer is the second most prevalent cancer-related cause of death. It accounts for 11% of all cancer diagnoses worldwide and is one of the tumours whose incidence is rising (1).

The basic therapy given to a diagnosed patient includes chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, and oral drugs, but the situation does not seem to be in control (3). The drugs after a certain limit start lingering on with the patient’s life rather than curing and hindering the metastasis. Hence, in such a situation, some inspiration could be drawn from the ancient literature of Ayurveda to study and find some ways to cure the malignancy and interfere with the process of spreading and growing, which could in turn help to prepare an arsenal against cancer (4).

Argemone mexicana Linn, from family Papaveraceae, is a well-known toxic plant reported for possessing anti-inflammatory properties (5). Its authenticity and use as ethnomedicine have been cross-checked from The Plant List (http://www.theplantlist.org/) and MPNS (https://mpns.science.kew.org/) where the plant was found to be occurring 38 times in medicinal sources. It is called “swankshiri” in Ayurveda and is given to patients as a natural purgative in the process of Virechana Panchkarma (6). It has been used for treating psoriasis and other skin diseases by traditional healers and has also been patented by Arora et al. (7) for its effective healing in psoriasis. The plant has also been seen for its anti-cancerous properties by traditional healers (8). The herb is also quoted in Indian Medicinal Plants (9) where it is found to possess alkaloids helpful in treating skin infections, warts, and tumours. Willcox et al. (10) claimed a study to cure malaria in Mali; a prospective, dose-escalating, quasi-experimental clinical trial was carried out there with a traditional healer who used a decoction of Argemone mexicana Linn (10). Evidence from clinical or preclinical studies could be not retrieved related to its effect on cancers, but the present study will prove its preliminary evidence in in vitro cell lines, which could be expanded further to preclinical studies later.

Cancer is a disease that is caused by orchestrated stimulation of inflammatory pathways. The study of regulatory pathways playing a role in inflammation gives a better understating of the prognosis of the disease (11). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) derived from either inflammatory/immune cells or the mitochondria of epithelial cells act as the central endogenous carcinogens that drive cancer-promoting signalling pathways which include nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB), STAT3, AKT, and COX-2 and are linked with different stages of cancer progression. This highlights the important role of such signalling pathways and involvement of transcriptional factors especially NF-kB which could be targeted in therapy for cancer. Rossi et al. (12) quoted the importance of TNF-α in cancers as it regulates some critical cellular processes such as cell survival and apoptosis, which are disrupted by TNF-α and its receptors (12). Xia et al. (13) and Tao et al. (14) reported the expression of inflammatory cytokines, NF-kB pathway stimulation, and other immunological events that leads to inflammation and eventually to cancer.

The prior literature review gave the research statement which helped us to draw the experiment where we could contemplate on the pivotal role of TNF-α and NF-kB regulation in the skin and colon cancer cell lines under the influence of Argemone mexicana (Linn) crude extract. To give supportive evidence to the study, the network pharmacology approach has also been utilized. With the help of network pharmacology approach, we can shed light on the way forward for the modernization of traditional medicine research and development through network pharmacology analysis, which also allows us to forecast and analyse the likelihood of drug side effects and identify new targets of drug effects (15).

Chemicals including MEM media (minimum essential medium), DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium), FBS (foetal bovine serum), and antibiotics (penicillin–streptomycin) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. The standard chemotherapeutic drugs dacarbazine (Da) and doxorubicin (Do) were purchased from Pfizer, USA. Plasticware including culture plates and flasks was purchased from NEST, China. The cell lines of skin cancer cells (A431), colon cancer cells (COLO 320DM), and L929 (Fibroblast) were procured from NCCS, Pune. The LC-MS analysis was done from SAIF, CDRI, Lucknow. The TNF-α kit (Catalogue No.: ELK1190) and NF-kB kit (Catalogue No: ELK1387) were purchased from ELK Biotechnology.

The leaves of Argemone mexicana Linn were collected from local areas and villages surrounding GLA University, Mathura, during February and March (coordinates: 27.49°N and 77.69°E). The leaves were authenticated from CIMAP (Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants), Lucknow, and the specimen sample was deposited with Voucher no. CIMAP/Bot-pharm/2021/09.

The extracts were prepared by a hot extraction method using the Soxhlet apparatus (16). The ethanolic (Eth), aqueous (Aq), acetone (Ac), and hexane (Hex) extracts were prepared and concentrated using a rotary vacuum evaporator (Yamato Scientific Co., Japan).

The LC-MS analysis was performed on Acquity Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography equipped with a Xevo TQD interfaced via an ESI source (Waters Co., Milford). The compounds were separated on a Thermo Scientific™ Accucore C-18, 150 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm reverse-phase column at a constant flow rate of 0.25 mL/min. The temperatures of the applied column and the auto-sampler were 35 ± 5°C and 25 ± 5°C, respectively. The mobile phase consisted of three solvents: acetonitrile (A), 0.1% formic acid buffer which was prepared in 95:5 v/v water/acetonitrile (B) using a multi-step gradient (Supplementary Table S1), and a sample injection volume of 2 μl. 1 mg of extracts was dissolved with 1 ml of methanol (LC/MS grade) and diluted to the concentration of 1 µl/ml. Then, the sample was filtered through a 0.22-µm PTFE membrane syringe filter before chromatographic analysis. The injection volume was 1 µl. The gas temperature was 350°C, and the gas flow was 13 L/min. Full-scan mass spectra in the range m/z 100–1,000 amu were acquired in positive and negative ion modes. The nebulizer was 45 psig. The analysis was performed by using Agilent MassHunter B.08.00 software (Qualitative Navigator, Qualitative Workflows) and the PCDL database (TCM database, phenolic acid, and PubChem chemical database). Peak identification was compared with the retention time, mass spectra, and fragmentation patterns with reference compounds from the library where accuracy was error less than 5 ppm and MS/MS fragment matching for each compound (17). The Mass Profiler Professional was used to perform chemometric differential MS data analysis to derive the relationship between the extract and their bioactivity. For qualitative analysis, full-scan data in both ES ± ion modes with a mass range of m/z 150–2,000 are summarized in Supplementary Table S2 of the Supplementary File. The LC-MS data acquisition was done using MassLynx software version 4.1.

For qualitative analysis, full-scan data in both ES ± ion modes in a mass range of m/z 150–2,000 are summarized in Supplementary Table S2 of the Supplementary File. The LC-MS data acquisition was done using MassLynx software version 4.1.

The compounds were mined extensively for target prediction by SwissTargetPrediction (threshold >0.1). The target ID identified as a human target with accurate UniProtKB/ID was retrieved. STRING 3.0 was used to analyse protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis. PPI networks, which are undirected graphs with proteins as nodes and known interactions between the linking proteins as edges, were analysed to exhibit them. To comprehend the organization and localization, additional topological and module analysis was conducted to identify the main hub proteins, their connections, and collective activities. For additional hub and module analysis, a minimal interaction network was chosen. The hub proteins are a representation of their essential signalling pathway roles. KEGG is used to analyse the protein’s functional importance. Cytoscape was used to create the networks (18).

L929, A431, and COLO 320DM cell lines were cultured and maintained in their defined medium as per the instruction from the cell culture repository, NCCS, Pune. The fibroblast cell line (L929) was used to determine the maximum non-toxic dose, and the skin (A431) and colon (COLO 320DM) cancer cell lines were used to study the cytotoxicity of the extracts with different non-toxic doses.

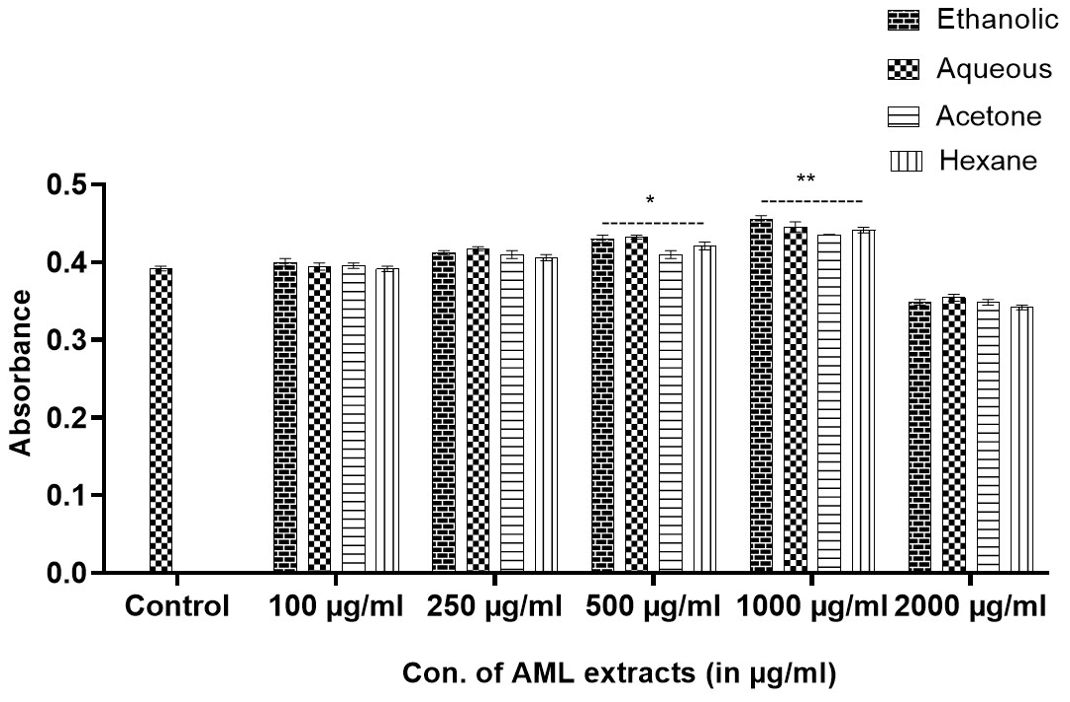

200 µl of 2 × 106 fibroblast cells/ml was seeded in a 96-well cultured plate using DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics at 37°C with 5% CO2 along with different concentrations 100 µg/ml, 250 µg/ml, 500 µg/ml, 1,000 µg/ml, and 2,000 µg/ml of the Argemone mexicana leaf Linn extracts (Eth, Aq, Ac, Hex). The cells were seeded in triplicates. The maximum non-toxic dose (MNTD) was determined by using MTT proliferation assay after 72 h of culture. The optical density was measured at 570 nm.

200 µl of 4 × 104 cells/ml from A431 and COLO 320DM was seeded in each well in modified MEM and RPMI 1640 media, respectively. The cells were incubated for 72 h with the non-toxic concentrations of the extracts Argemone mexicana Linn from 100 µg/ml to 1,000 µg/ml. Dacarbazine (DA) and doxorubicin (DO), standard chemotherapeutic drugs, were used as positive control in different concentrations 20 µg/ml, 40 µg/ml, 60 µg/ml, and 80 µg/ml. The percentage inhibition of cells was calculated by MTT assay after 72 h. The IC 50 value was calculated, and statistical analysis was done using GraphPad Prisma version 8.

A431 and COLO 320DM were cultured in 96-well plates as given above with different concentrations of Argemone mexicana Linn extract and standard chemotherapeutic drug. The culture supernatant was collected after 48 h. The concentration of TNF-α was estimated using an ELISA kit as per the manufacturer’s instruction.

1 ml of 4 × 104 cells of A431 and COLO 320DM was cultured in 1-cm2 culture plates along with different concentrations of Argemone mexicana Linn extracts. The cells were cultured and left unstimulated as well as stimulated with 20 pg/ml of TNF-α (19) as per the protocol by Ernst et al. (20). After 40 min, the supernatant was discarded and the cells were collected with 0.25% trypsin and lysed with 1 M lysis buffer containing 10 mM tris HCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.01% sodium deoxycholate, 140 mm NaCl, and 1× PMSF (21). The cells were further sonicated for 10 min for complete lysis. The cell homogenate was then centrifuged for 10 min at 1,500 rpm. The supernatant was collected, and the p65 transcription factor was estimated using ELISA kit according to its manufacturer protocol.

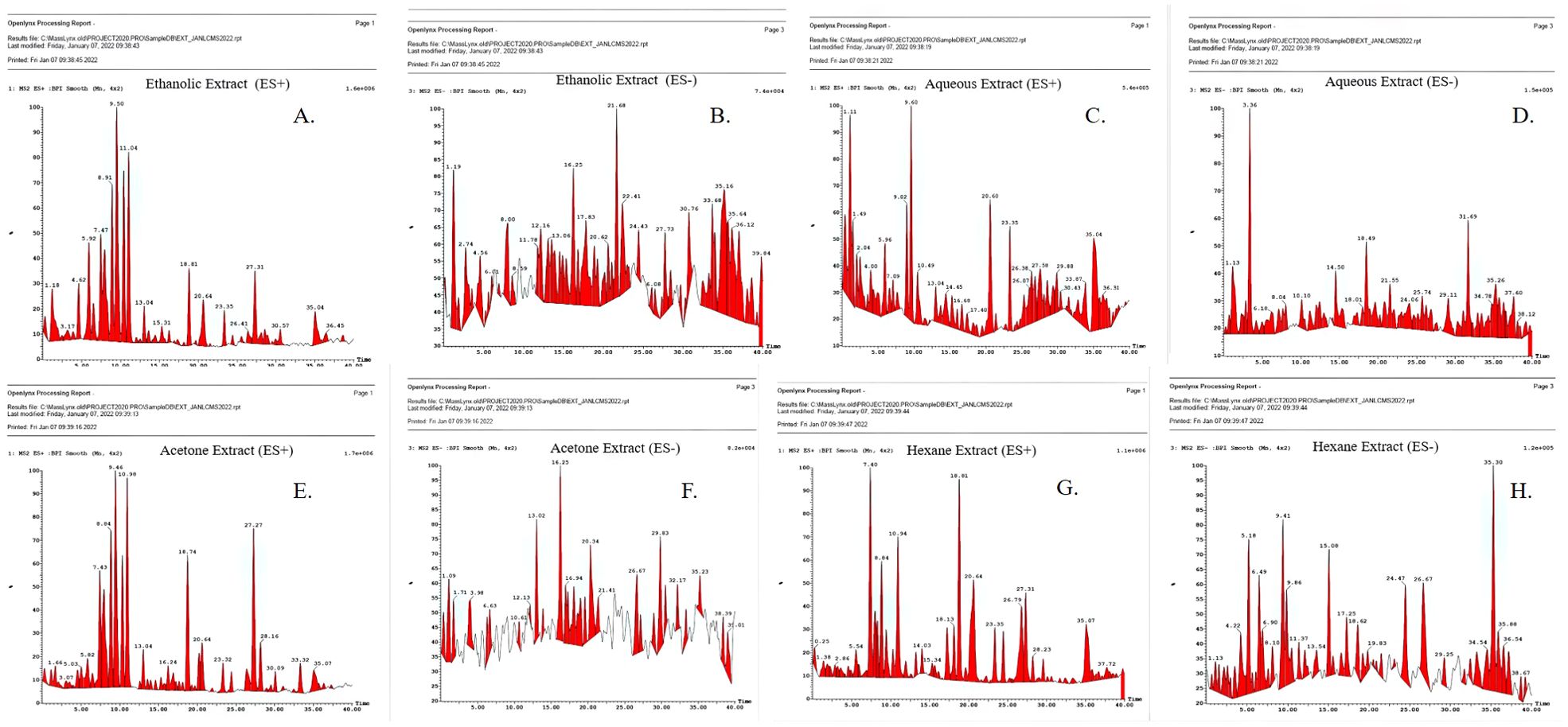

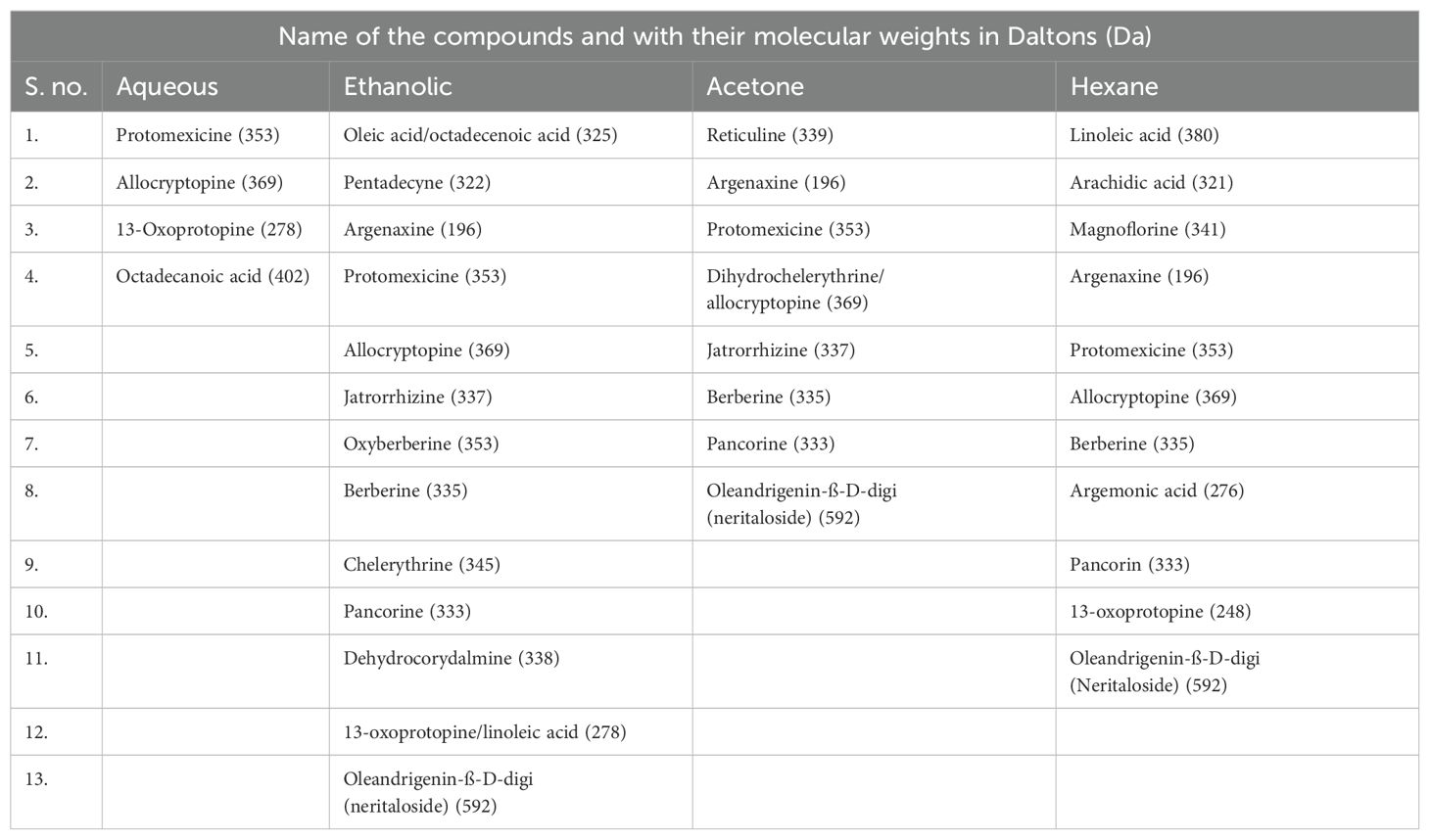

The mass spectra of the tested extracts are shown in Figure 1 and predicted compounds in Table 1. Anti-cancerous compounds like berberine (mw: 335 da), octadecanoic acid (mw: 402 da), protomexicine (mw: 353 da), jatrorrhizine (mw: 337 da), oleandrigenin-ß-D-digi (neritaloside) (mw: 592 da) were predicted in ES+ and ES− spectra of different extracts. Detailed lists of the compounds with their predicted molecular weights are given in the supplementary file (Supplementary Tables S3.1–S3.4) with their biological activities. The spectrum analysis precited the presence of compounds having noted anti-cancerous activity from the literature.

Figure 1. LC/MS spectrum of Argemone mexicana Linn leaf extract (A-H). (A) Ethanolic extract (ES+). (B) Ethanolic extract (ES−). (C) Aqueous extract (ES+). (D) Aqueous extract (ES−). (E) Acetone extract (ES+). (F) Acetone extracts (ES−). (G) Hexane extract (ES−). (H) Hexane extract (ES−).

Table 1. LC/MS-predicted compounds with their calculated molecular weights in different extracts of Argemone mexicana Linn.

The targets searched intersecting with the disease interacting space shown above (see Figure 2) were searched for crucial protein interactions in the STRING interactome. The protein–protein interaction network had 290 nodes and 434 edges highlighted to show enrichment for melanoma (p-value 1.83E−13) involving MAPK1, CDK4, MDM2, PDGFRB, MAPK3, PIK3CA, MAP2K1, MET, PIK3CD, AKT2, BAD, FGFR1, BRAF, AKT1, AKT3, PIK3CB; pathways in cancer (p-value 1.39E−25) involving MAPK1, TGFB1, RPS6KB1, FLT3, CDK4, MDM2, PDGFRB, CREBBP, MAPK3, PRKCG, PIK3CA, CDK2, CSF1R, PPARG, KIT, MAP2K1, F2, TERT, PRKACA, PPARD, MET, ROCK2, GSK3B, HSP90AA1, MTOR, PTGS2, ABL1, PIM1, HDAC1, AR, PIM2, PIK3CD, IL6ST, JAK2, AKT2, BAD, MAPK8, ROCK1, FGFR1, MAPK9, AGTR1, PRKCA, BRAF, HDAC2, NTRK1, JAK3, TGFBR1, AKT1, CDC42, AKT3, and PIK3CB. This network was then used to elucidate significant functional annotations further. The target functional enrichments are represented in a pie, where the pie is coloured according to the most significant functional terms which are regulated by melanoma represented by the green colour, cancer represented by red, pathways in carcinoma represented by purple, and colon cancer cells represented by orange (Figure 2A). Important targets related to skin and colon cancer are indicated by the yellow colour.

Figure 2. (A) Compound target–protein–protein interaction functional enrichment network of A. mexicana. (B) Pathway enrichment network.

The compounds in allocryptopine, oxy-berberine, chelerythrine, and neritaloside all show a connection to the metabolic process. The PPI pathways study revealed melanoma (FDR: 1.823E−13), cancer (FDR: 3.121E−13), and colonic cancer (0.0049) in terms of enrichment, indicating that the active compounds are more likely to involve targeted pathways in melanoma than colon cancer. Additional research intends to investigate these links to their potential role in cancer.

The network analysis of the molecules shows their importance in the promotion of cancer in colon and skin cancer cell lines. Figure 2B shows the enriched network clustered based on enrichment scores of pathway terms which were used in the network of pathway and process enrichment analyses. The distance between the targets is proportional to their involvement in the targeted pathways about their involvement in the enriched terms which were clustered according to their kappa scores with a similarity >0.3, and nodes reflecting significant p-values from each of the top clusters are connected by edges. We find a high correlation between microRNAs in cancer and the PI3K-Akt pathway. The PI3K-Akt signalling pathway was determined to have the highest likelihood shown in Figure 3A, which displays a comparative analysis and ranking of enriched pathways. This pathway is the best-ranked one, and it has 40 target genes that have a relatively small fold enrichment distance; these genes may be involved in skin and colon cancers. The PI3K-Akt signalling pathway as shown in Figure 3B is the most crucial one that has been highlighted.

The network pharmacology study found that the phytochemicals from Argemone mexicana have an effect on PI3K-Akt. It has been shown in multiple studies that NF-kB is involved in the PI3K-Akt signalling pathway. According to Tewari et al. (22), NF-kB is situated downstream of AKT, even though it is not directly involved in the main PI3/AKT pathway. Activation of AKT is essential for various tumorigenic NF-kB activities, which is tried to tap along with TNF-α expression. In diseases like skin cancer and colon cancer, where an overabundance of TNF-α production is a factor in disease progression, this study in expression is important to be noted.

After 72 h, MTT dye analysis revealed that the Argemone mexicana extract at 1,000 µg/ml was non-toxic and promoted fibroblast cell growth. The proliferation rate was 22.5% with Eth, 12.34% with Aq, 15.96% with Ac, and 11.54% with Hex extracts compared with control. The 2,000-µg/ml concentration was toxic, resulting in a −35% reduction in proliferation compared with the control (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Determination of non-toxic doses of Argemone mexicana Linn extracts by MTT cell viability assay on L929 fibroblast cells. The extracts up to 1,000 µg/ml were found to be non-toxic, and a dose of 2,000 µg/ml was toxic to the cells.

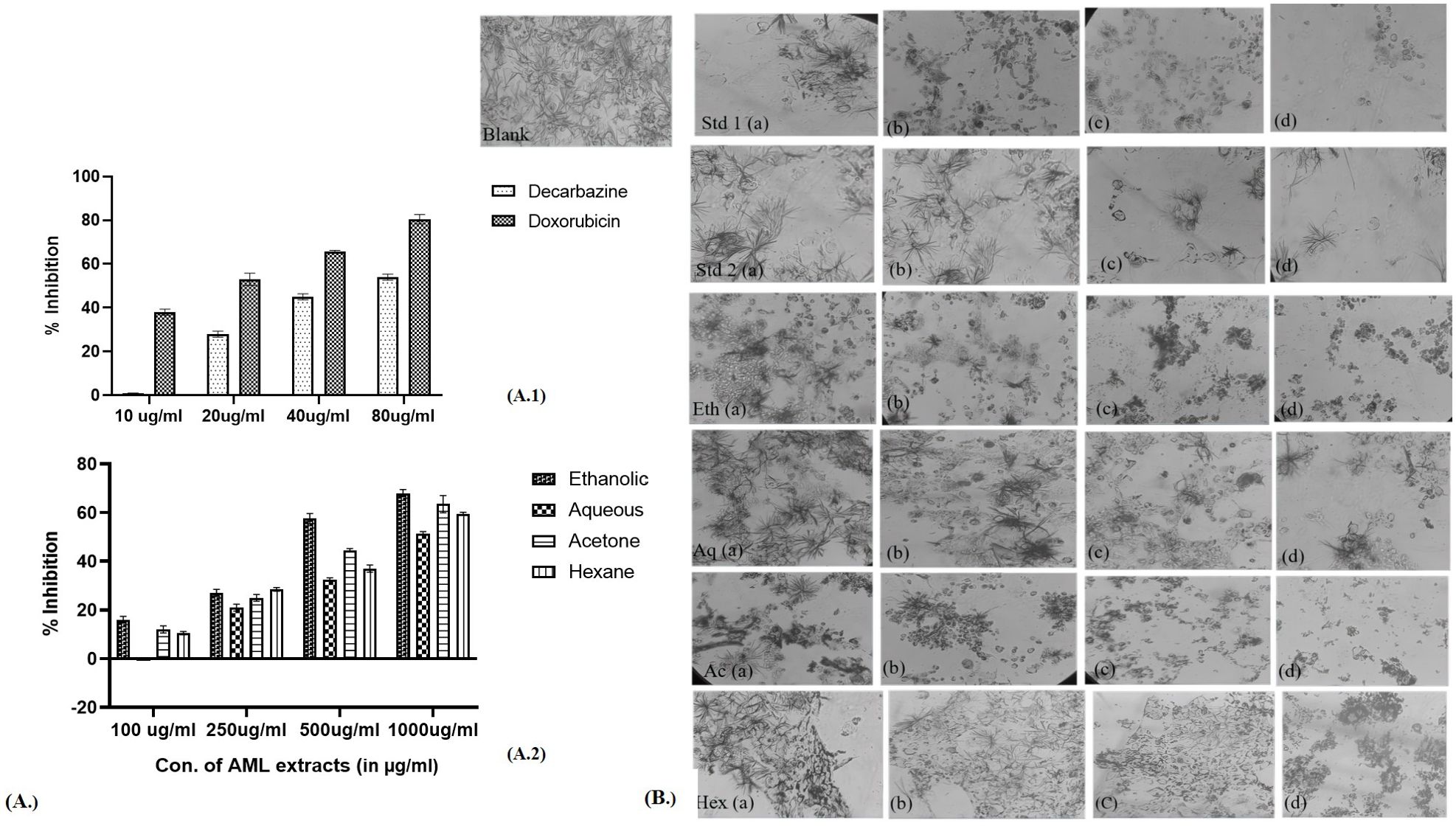

The cytotoxic effect of different extracts of leaves Argemone mexicana Linn was observed in cancer cell lines in the form of inhibition of proliferation, which is shown in Figure 5 (skin cancer) and Figure 6 (colon cancer). The significant differences were observed in form of percentage of inhibition calculated using the formula.

Figure 5. Percentage inhibition in the skin cancer cell line in the presence of different extracts of Argemone mexicana Linn leaves. (A) 1: percentage inhibition of skin cancer cells by doxorubicin and dacarbazine at 80 µg/ml. (A) (2.): depicts the inhibition to be reduced at 1,000 µg/ml by the ethanolic extract. (B): Std 1 (a.) has been treated with 20 µg/ml, (b.) 40 µg/ml, (c.) 60 µg/ml, and (d.) 80 µg/ml of chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin and the same dose has been administered in Std 2 (a-d) of dacarbazine. Eth (a-d) has been treated with 100 µg/ml, 250 µg/ml, 500 µg/ml, and 1,000 µg/ml of the ethanolic extract. The same doses have been given for Aq (a-d), Ac (a-d), and Hex (a-d). The cytotoxic effects become apparent when the number of cells decreases following the MTT assay.

Figure 6. Percentage inhibition in colon cancer cell line in the presence of different extracts of Argemone mexicana Linn leaves. (A) 1: percentage inhibition of colon cancer cells by dacarbazine and doxorubicin at 80 µl/ml. (A) 2: The inhibition can be seen to reduce at 1,000 µg/ml by the ethanolic extract. (B) The doses Std 1 (a-d.), Std 2 (a-d), Eth (a-d), Aq (a-d), Ac (a-d), and Hex (a-d) have been given the same as skin cancer.

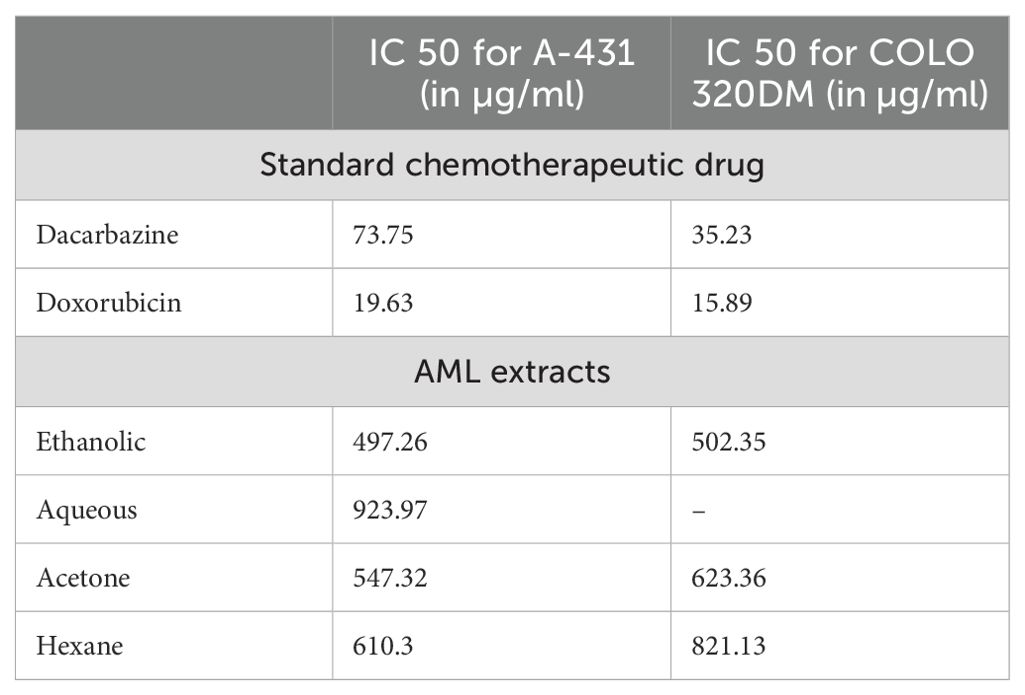

The extracts showed dose-dependent effectiveness, with ethanolic extract at 1,000 µg/ml inhibiting cell growth by up to 68.7%. In skin cancer cells, the IC50 for standard chemotherapeutic drugs was 73.75 µg/ml for dacarbazine and 19.63 µg/ml for doxorubicin. The IC50 values for AML extracts were 497.26 µg/ml for ethanol, 923.97 µg/ml for aqueous, 547.32 µg/ml for acetone, and 610.3 µg/ml for hexane. Figure 5 presents the pictures of skin cancer cells treated with AML extracts. Table 2 presents the IC50 values for respective AML extracts for A-431 and COLO 320 DM cell lines.

Table 2. Comparative IC50 values of standard chemotherapeutic drugs and AML extracts on skin and colon cancer cell lines.

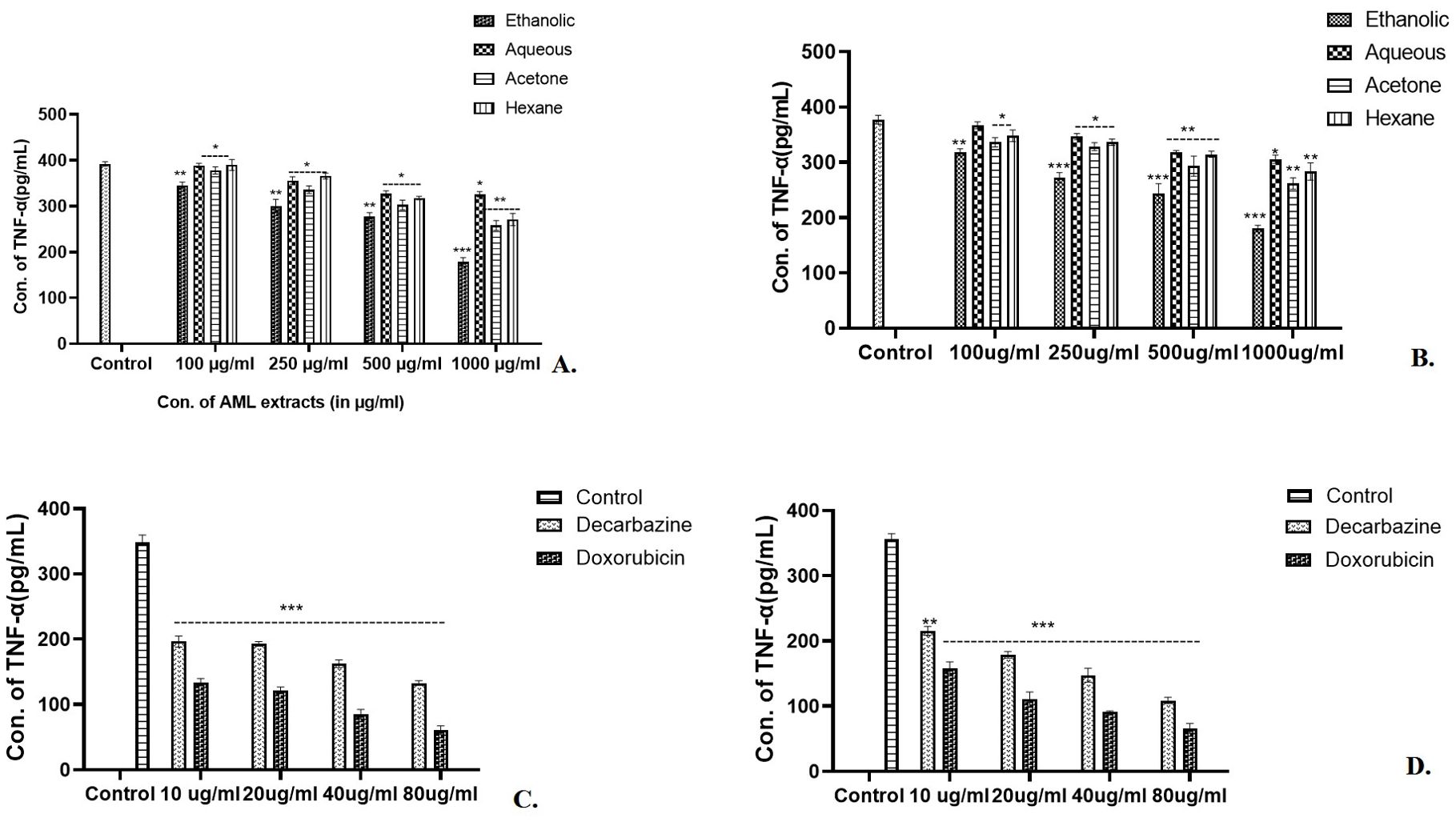

In the case of skin cancer and colon cancer cell lines (Figures 7A, B), a highly significant (p<0.001) scaling down in concentration of TNF-α was observed by 1,000 µg/ml of ethanolic extract. The other extracts reduced the TNF-α concentrations of Aq (p<0.05), Ac (p<0.01), and Hex (p<0.01) at 1,000 µg/ml of AML extract (Figures 7A, B). A significant reduction by 80 µg/ml of standard chemotherapeutic drug dacarbazine (p<0.001) and doxorubicin (p<0.001) was also observed (Figures 7C, D) in both the cell lines. In conclusion, 1,000 µg/ml of ethanolic extract had the lowest TNF-α concentration (187.67 pg/ml) as compared with other extracts in the case of skin cancer cell lines. On the other hand, the AML extracts showed inhibition in TNF-α significantly by 1,000 µg/ml of ethanolic and acetone extracts (p<0.001) for colon cancer (Figure 7B), p<0.01 for acetone and hexane, and p<0.05 for aqueous extract.

Figure 7. After exposure to the Argemone mexicana leaf extract, the expression of TNF-α cytokine was reduced. Eth AML extract (1,000 µg/ml) significantly reduced the expression of TNF-α in skin and colon cancer cell lines [p<0.001, (A, B)]. Using 80 µg/ml of doxorubicin and dacarbazine, TNF-α levels in skin cancer cells in (C) and colon cancer cells in (D) were considerably decreased. *** stands for p<0.001, ** for p<0.01, and * for p<0.05 respectively. The two-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test was employed to calculate the significance.

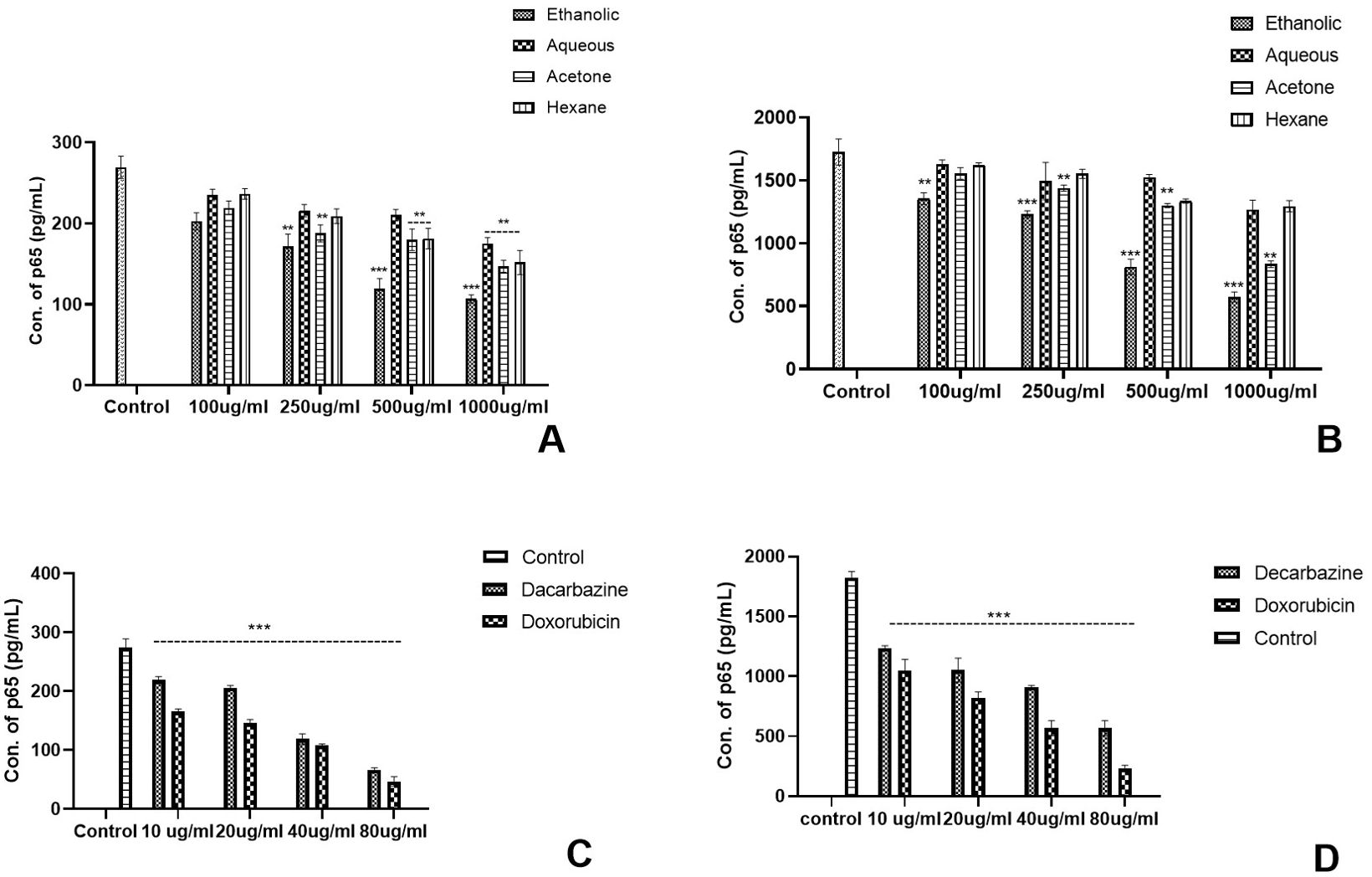

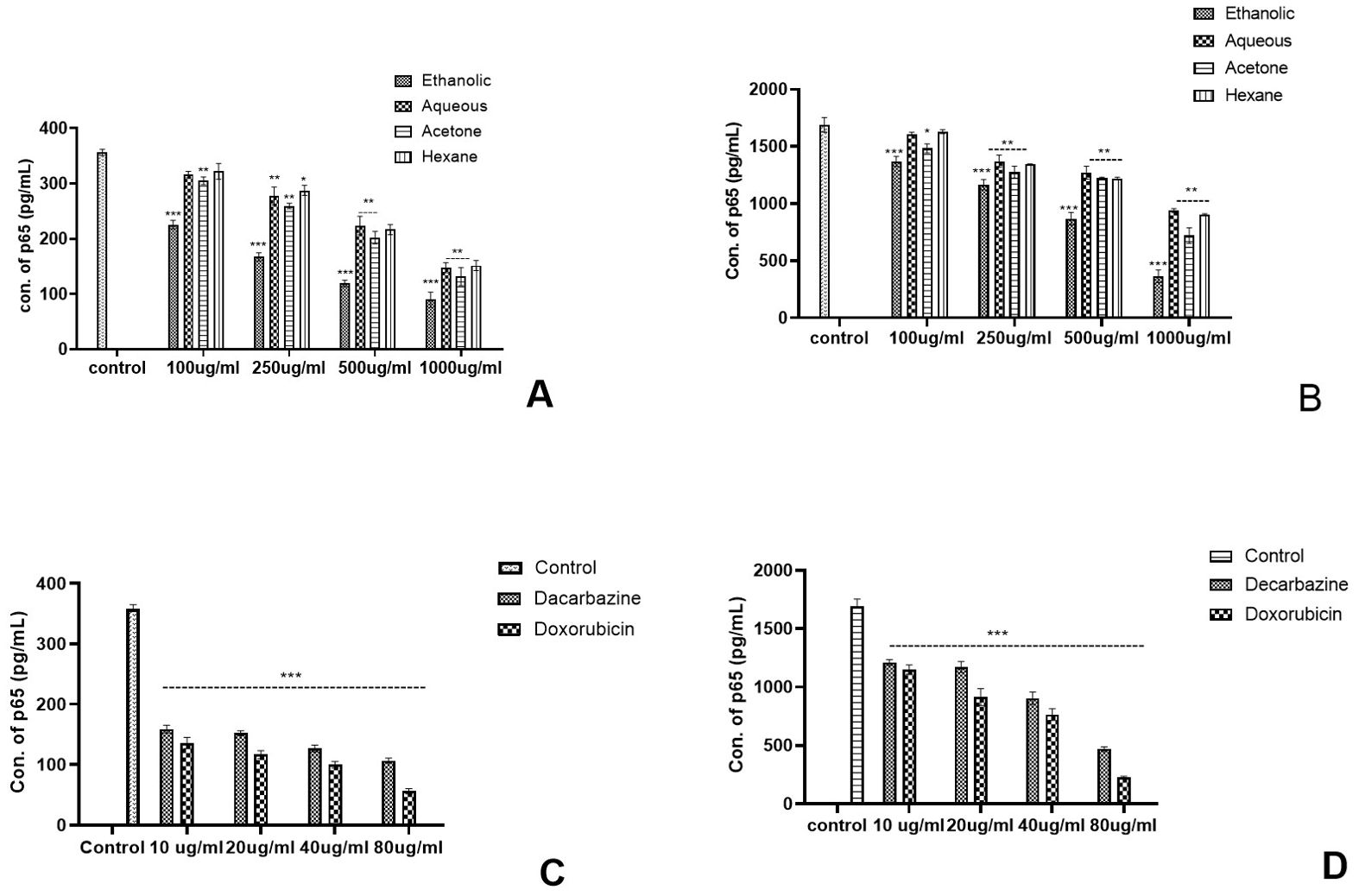

The experiment was conducted as a comparative study to differentiate the activation of the NF-kB pathway by analysing the concentration of the p65 transcription factor in TNF-α stimulated and unstimulated cancer cell cultures as per the protocol by Ernst et al. It was evaluated that p65 in the TNF-α-stimulated cell culture was ~8–9 times higher than the unstimulated cells. In skin cancer, the concentration of p65 transcription factor was significantly reduced in unstimulated cancer cells by Eth extract of Argemone mexicana Linn (Figures 8A, C) and stimulated culture (Figures 8B, D). However, less significant reduction in p65 concentration was observed with the aqueous and hexane extracts of Argemone mexicana Linn leaves in skin as well as colon cancer cell lines (Figures 9A, B). A 80-µg/ml concentration of standard chemotherapeutic drug was found to significantly reduce the p65 subunit by Da (52.36%) and Do (78.56%) (Figure 8C). On the other hand, in the unstimulated cells, the p65 concentration was extremely reduced in the ethanolic extract from 268.18 pg/ml to 112.89 pg/ml and significantly reduced to 145.56 pg/ml in the acetone extract, while in aqueous and hexane extracts, no significant reduction was observed.

Figure 8. Effect of Argemone mexicana extracts on the reduction of the p65 transcription factor concentration in the skin cancer cell line. (A) presents the unstimulated cell culture where the amount of NF-kB has been significantly reduced under the influence of 1,000 µg/ml of ethanolic extract (p<0.001). (B) presents the stimulated cell culture where the amount of NF-kB expressed is higher in comparison with image (A). The expression of the transcription factor significantly reduced p<0.001 with 1,000 µg/ml of ethanolic extract. (C) depicts the unstimulated cancer cell culture treated with the standard chemotherapeutic drugs dacarbazine and doxorubicin, while (D) represents the TNF-α-stimulated culture in the presence of dacarbazine and doxorubicin. A statistically significant (p<0.001) reduction was observed with both the drugs. *** stands for p<0.001, ** for p<0.01, and * for p<0.05. Two-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test was employed to calculate the significance.

Figure 9. Effect of Argemone mexicana extracts on the reduction of the p65 transcription factor concentration in the colon cancer cell line. (A) represents the TNF-α unstimulated colon cancer cell culture where the concentration of p65 was significantly reduced by ethanolic extract at different doses while the highest dose 1,000 µg/ml reduced the p65 in other extracts. (B) represents the TNF-αstimulated cell culture where all the extracts significantly reduced the p65 concentration. However, maximum reduction was with the 1,000-µg/ml ethanolic extract. (C) summarizes the TNF-αunstimulated cancer cell culture treated with the standard chemotherapeutic drugs dacarbazine and doxorubicin. (D) represents the TNF-α-stimulated cancer cells treated with the same chemotherapeutic drugs with the same doses. Both the drugs statistically significantly (p<0.001) reduced the p65 concentration. *** stands for p<0.001, ** for p<0.01, and * for p<0.05. Two-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test was employed to calculate the significance.

In comparison with skin cancer cell lines in colon cancer cell lines, significant reduction was noted with all the extracts in TNF-α-stimulated as well as unstimulated cultures. However, the highest reduction was observed with ethanolic extracts at different concentrations as compared with the respective concentrations of the other extracts (Figures 9A, B). Both the standard chemotherapeutic drugs dacarbazine and doxorubicin reduced the concentration p65 transcription factor. Doxorubicin reduced the concentration of p65 from 355.12 pg/ml to 45.16 pg/ml in TNF-α-unstimulated and from 1782.79 pg/ml to 228.16 pg/ml values in stimulated cultures, respectively (Figures 9C, D). The ethanolic AML extract was found to reduce the p65 concentration from 355.57 pg/ml to 88.13 pg/ml in the unstimulated cell culture.

Cancer, the second-biggest cause of mortality after heart disease, is a global health issue. In recent years, interest in natural compounds having anticancer therapeutic potential has grown. Without a doubt, pharmacological studies of plant extracts as a source of secondary metabolites (23) are the most crucial step in discovering molecules from plants that could potentially serve as medicines. Argemone mexicana Linn is one of the plants known for its anticancer activity. Indians use different parts of the plant to treat a variety of diseases, including jaundice, scabies, fungal infections, ulcers, asthma, intestinal infections, skin, cough, and other conditions (24, 25). The plants’ pooled phytochemicals and their derivatives, such as sterols, flavonoids, and alkaloids, could potentially treat cancer (26).

We performed the LC/MS analysis for four distinct leaf extracts (ethanolic, aqueous, acetone, and hexane) and predicted the compounds based on their molecular weights. The study predicted various types of alkaloids and flavonoids, such as berberine, oleandrigenin-ß-D-digi (neritaloside), and pancorine, among others. All the extracts shared octadecanoic acid (M.W. 402 Da). This was also found in the GC/MS analysis done by Khan and Bhaduria in 2019 (27). In addition to this, oleandrigenin-ß-D-digi (Neritaloside) (592 Da) was found in all three extracts. This substance has been found in Nerium oleander and has been studied extensively for its ability to fight cancer by various researchers (28). The literature has already reported the anticancer properties of all the identified compounds (29, 30).

It was observed that the compounds allocryptopine, oxyberberine, chelerythrine, linoleic acid, and neritaloside, common in all extracts, support the experimentally observed effects. It was found that the PI3K-Akt signalling pathway is very important for controlling inflammation and tumour growth. The effect of this pathway is by modulating the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and the activity of transcription factors like NF-kB-p65 (31, 32). The results of the tests with Argemone mexicana Linn extracts show that natural compounds may be able to target these pathways to help treat cancer and inflammatory diseases.

Despite being a well-known toxic plant, sanguinarine has garnered significant attention in the past, particularly following the case of dropsy, which resulted from the mixing of plant seeds with mustard seeds due to their similarity (33), However, a study conducted in Mali, South Africa, revealed the effectiveness of using plant extract as a treatment for malaria. The study was conducted in clinical trials in Mali and Switzerland (10). These showed that the other parts are safe because they do not contain sanguinarine. This led to our study, in which we tested the MNTD of Argemone mexicana Linn leaf extracts on fibroblast cell lines (L929). It was evaluated that the dose of 2,000 µg/ml of all the extracts was found to be toxic and showed inhibition in proliferation of fibroblast cells, and the MNTD was determined to be 1,000 µg/ml of all the extracts, which were used for further study.

The study used skin cancer cell lines (A-431) and colon cancer cell lines (COLO 320 DM) to determine the anti-cancerous activity. In this experiment, 1,000 µg/ml of the ethanolic extract showed the highest inhibition percentage for both cell lines compared with other extracts.

Prabhakaran et al. (34) cited research on Argemone mexicana. Linn flowers’ anticancer effect against HEPG2 human liver cancer cells using alkaloids such as angoline (34). Other in vitro studies reported the activity of compounds like chelerythrine on the human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line (HONE-1) and the human gastric cell line (NUGC) (35). The LC/MS analysis of the ethanolic AML extract had predicted the presence of a chelerythrine component (ref. Table 1), which may be consistent with the extract’s potent anticancer effects. Gacche et al. (36) conducted a study to examine the cytotoxic effects of three different AML extracts. The results showed that the ethanolic extract had the most favourable impact. According to the reports, Argemone mexicana Linn leaves were found to exhibit cytotoxic effects on a variety of cell lines, including those representing metastatic breast cancer (MDA-MB-435S), colon cancer (HT29), gastric cancer (AGS), cervical cancer (HELA), leukaemia (HL-60), and renal carcinoma (PN-15) (37, 38). Singh et al. (39) found 200 µg/ml of isolated alkaloids effective in colon cancer cell lines. This study tested the crude extract on cell lines, and the synergistic effect of the phytoconstituents confirmed their activity and high dose compared with isolated chemicals (40). The findings on cancer cell growth inhibition by ethanolic AML extract were supported by a dose-dependent downregulation in the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α. In the test, 1,000 µg/ml of the ethanolic extract was shown to significantly lower the level of TNF-α in skin cancer (p<0.001 at 187.67 pg/ml) and colon cancer (p<0.001 at 175.99 pg/ml) cell lines (b). The results could be correlated with the study by Monterrosas-Brisson et al. (41), where it was concluded that the methanolic extract of Argemone mexicana Linn lowered TNF-α in inflammation in an ear oedema-induced mouse model.

The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) family of transcription factors plays a key role in inflammation and cancer. Various biological stimuli activate the cytoplasmic NF-kB protein. Two different pathways, conventional and non-conventional, turn on NF-kB. These pathways involve complex molecular interactions involving adaptor proteins, phosphorylation, and ubiquitinase enzymes. The nucleus experiences an increase in NF-kB translocation, which in turn regulates gene expression (42). In cancer, NF-kB activation is associated with cell proliferation, survival, invasion, and angiogenesis, making it a viable therapeutic target. Inhibitors of NF-kB have been found to suppress tumour growth and induce apoptosis in malignant cells (43). The NF-kB transcription factor was similarly tapped in our study to understand the potential of AML as an anticancer agent. It was found that the concentration of p65 (the transcription factor of the NF-kB pathway) was found to be reduced in TNF-α-stimulated skin cancer cells (232.89 pg/ml), colon cancer cells (325.89 pg/ml), unstimulated skin cancer cells (63.16 pg/ml), and colon cancer cell lines (88.13 pg/ml) as compared with control cultures by the AML extract. The ethanolic extract exhibited a significant reduction (p> 0.001) at 1000 µg/ml in the cell cultures.

The downregulation of TNF-α expression and the modulation of NF-kB-p65 transcription factor in a dose-dependent manner, as observed in the experiments, can be correlated with the involvement of Argemone mexicana phytochemicals on PI3K-Akt, as concluded in the network pharmacology study (ref. Figure 2). There is various evidence indicating a connection between the PI3K-Akt signalling pathway and NF-kB (32, 44, 45). Despite not being a part of the main PI3/AKT pathway, NF-kB is located downstream of AKT (22). AKT activation plays a critical role in several NF-kB tumorigenic activities (46). This downregulation is significant in cases where excessive TNF-α production contributes to disease pathology, such as skin cancer and colon cancer. It can influence NF-kB activity by regulating its nuclear translocation and DNA binding ability. In the context of inflammation and cancer, aberrant NF-kB activation can lead to the upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes and promote tumorigenesis. So, changing the activity of NF-kB through the PI3K-Akt pathway can help control inflammatory responses and stop the growth of tumours. The ethanolic extracts of Argemone mexicana Linn have been found to exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by downregulating TNF-α expression and modulating NF-kB-p65 transcription factor activity, suggesting their potential therapeutic efficacy in inflammatory and cancer-related conditions.

The present study evaluated the anticancer properties of Argemone mexicana Linn, which is a plant already known for its anti-inflammatory and other medicinal properties. Different types of extracts (Eth, Aq, Ac, and Hex) in different doses were tested with A431 and COLO 320DM cell lines, and a significant inhibition in cell proliferation could be seen in a dose-dependent manner. The observed inhibition could be validated by studying the TNF-α expression and regulation of the NF-kB-p65 transcription factor and its signalling pathway. The latter are well known to play a role in inflammatory diseases, including cancer. The 1,000 µg/ml of ethanolic extract was found to be the most effective in the experiments conducted. We can conclude that the plant possesses anticancer properties, and further experimental setups, such as in vivo and other preclinical studies, could further explore the medicinal potential of Argemone mexicana in cancer treatment.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

SK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization. AG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, GLA University, Mathura, India, for providing the financial support to conduct this study. This study was supported by a grant (No. RD-11302) from the Tainan Municipal Hospital (managed by Show Chwan Medical Care Corporation), Tainan, Taiwan. The authors also acknowledge and extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSPD2024R713), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2024.1502819/full#supplementary-material

TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; NF-kB, Nuclear factor kappa B; MNTD, Maximum Non-toxic Dose; ELISA, Enzyme-Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; STAT-3, Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; COX-2, Cyclooxygenase 2; MEM, Minimum Essential Medium; DMEM, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium; FBS, Fetal Bovine Serum; LC/MS, Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry; ESI, Electrospray Ionization; MTT, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide; EDTA, Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid; PMSF, Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; Abs, Absorption; Std, standard.

1. Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistic. CA: Cancer J Clin. (2024) 74:12–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820

2. Miller KD, Ortiz AP, Pinheiro PS, Bandi P, Minihan A, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics for the US Hispanic/Latino populatio. CA: Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:466–87. doi: 10.3322/caac.21695

3. Debela DT, Muzazu SG, Heraro KD, Ndalama MT, Mesele BW, Haile DC, et al. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE Open Med. (2021) 9:1–10. doi: 10.1177/20503121211034366

4. Arnold JT. Integrating ayurvedic medicine into cancer research programs part 1: Ayurveda background and applications. J Ayurveda Integr Med. (2023) 14:p.100676. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2022.100676

5. Kulshrestha S, Goel A. A panoramic view on Argemone mexicana: its medicinal importance and phytochemical potentials. Plant Arch. (2021) 21:40–9. doi: 10.51470/PLANTARCHIVES.2021.v21.no1.006

6. Pathak R, Goel A, Tripathi SC. Medicinal property and ethnopharmacological activities of Argemone mexicana: an overview. Ann Rom Soc Cell Biol. (2021) 1615–41. Available online at: http://annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/1609.

7. Arora S, Gupta L, Srivastava V, Narender S, Dinesh S. Herbal Composition for Treating Various Disorders Including Psoriasis, A Process For Preparation Thereof And Method For Treatment Of Such Disorders. India, Patent No WO 2003/057133A3. (2003)

8. Gayoor KM, Kanta SN, Umama Y, Baskar H, Ayush K, Prasad TS. Ethnopharmacological studies of argemone mexicana for the management of psoriasis followed by molecular techniques through metabolomics. Signs. (2019) 1:4.

9. Khare CP. Indian medicinal plants: an illustrated dictionary. Springer Science & Business Media. New York, USA: Springer Publications (2008).

10. Willcox ML, Graz B, Falquet J, Sidibé O, Forster M, Diallo D. Argemone mexicana decoction for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hygiene. (2007) 101:1190–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.05.017

11. Das R, Mitra S, Tareq AM, Emran TB, Hossain MJ, Alqahtani AM, et al. Medicinal plants used against hepatic disorders in Bangladesh: A comprehensive review. J Ethnopharmacol. (2022) 282:114588. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114588

12. Rossi AFT, Contiero JC, da Silva Manoel-Caetano F, Severino FE, Silva AE. Up-regulation of tumor necrosis factor-α pathway survival genes and of the receptor TNFR2 in gastric cancer. World J Gastrointestinal Oncol. (2019) 11:281. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i4.281

13. Xia L, Tan S, Zhou Y, Lin J, Wang H, Oyang L, et al. Role of the NFκB-signaling pathway in cancer. OncoTargets Ther. (2018), 2063–73. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S161109

14. Tao X, Li J, He J, Jiang Y, Liu C, Cao W, et al. Pinelliaternata (Thunb.) Breit. attenuates the allergic airway inflammation of cold asthma via inhibiting the activation of TLR4-medicated NF-kB and NLRP3 signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. (2023) 315:116720. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116720

15. Noor F, Tahir ul Qamar M, Ashfaq UA, Albutti A, Alwashmi AS, Aljasir MA. Network pharmacology approach for medicinal plants: review and assessment. Pharmaceuticals. (2022) 15:572. doi: 10.3390/ph15050572

16. Sharma A, Goel A, Lin Z. In vitro and in silico anti-rheumatic arthritis activity of nyctanthesarbor-tristis. Molecules. (2023) 28:6125. doi: 10.3390/molecules28166125

17. Banerjee S, Tiwari A, Kar A, Chanda J, Biswas S, Ulrich-Merzenich G, et al. Combining LC-MS/MS profiles with network pharmacology to predict molecular mechanisms of the hyperlipidemic activity of Lagenaria siceraria stand. J Ethnopharmacol. (2023) 300:115633. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115633

18. Sharma R, Jadhav M, Choudhary N, Kumar A, Rauf A, Gundamaraju R, et al. Deciphering the impact and mechanism of Trikatu, a spices-based formulation on alcoholic liver disease employing network pharmacology analysis and in vivo validation. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:1063118. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1063118

19. Szychowski KA, Skóra B, Kryshchyshyn-Dylevych A, Kaminskyy D, Tobiasz J, Lesyk RB, et al. 4-Thiazolidinone-based derivatives do not affect differentiation of mouse embryo fibroblasts (3T3-L1 cell line) into adipocytes. Chemico-Biol Interact. (2021) 345:109538. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109538

20. Ernst O, Vayttaden SJ, Fraser ID. Measurement of NF-κB activation in TLR-activated macrophages. Innate Immune Activation: Methods Protoc. (2018) 1714:67–78. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7519-8_5

22. Tewari D, Patni P, Bishayee A, Sah AN, Bishayee A. Natural products targeting the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway in cancer: A novel therapeutic strategy. In: Seminars in cancer biology, vol. 80. New York, USA: Academic Press (2022). p. 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.12.008

23. Anand U, Jacobo-Herrera N, Altemimi A, Lakhssassi N. A comprehensive review on medicinal plants as antimicrobial therapeutics: potential avenues of biocompatible drug discovery. Metabolites. (2019) 9:258. doi: 10.3390/metabo9110258

24. Sharma J, Gairola S, Gaur RD, Painuli RM. The treatment of jaundice with medicinal plants in indigenous communities of the Sub-Himalayan region of Uttarakhand, India. J Ethnopharmacol. (2012) 143:262–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.06.034

25. Iqbal J, Abbasi BA, Mahmood T, Kanwal S, Ali B, Shah SA, et al. Plant-derived anticancer agents: A green anticancer approach. Asian Pacific J Trop Biomed. (2017) 7:1129–50. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.10.016

26. Brahmachari G, Roy R, Mandal LC, Ghosh PP, Gorai D. A new long-chain secondary alkanediol from the flowers of Argemone mexicana. J Chem Res. (2010) 34:656–7. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2013005000021

27. Khan AM, Bhadauria S. Analysis of medicinally important phytocompounds from Argemone mexicana. J King Saud University-Sci. (2019) 31:1020–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2018.05.009

28. Singh Y, Nimoriya R, Rawat P, Mishra DK, Kanojiya S. Quantitative evaluation of cardiac glycosides and their seasonal variation analysis in Nerium oleander using UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Phytochem Anal. (2022) 33:746–53. doi: 10.1002/pca.3126

29. Kanwal N, Rasul A, Hussain G, Anwar H, Shah MA, Sarfraz I, et al. Oleandrin: A bioactive phytochemical and potential cancer killer via multiple cellular signaling pathways. Food and Chemical Toxicology. (2020) 143:111570. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111570

30. Goel A. Current understanding and future prospects on Berberine for anticancer therapy. Chem Biol Drug Design. (2023) 102:177–200. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.14231

31. Salam DSD, San HS, Bhave M, Theng LB, Wezen XC. NF-κB pathway analysis and biomarker identification in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Re: Gen Open. (2023) 3:11–20. doi: 10.1089/regen.2022.0032

32. Banerjee S, Kar A, Mukherjee PK, Haldar PK, Sharma N, Katiyar CK. Immunoprotective potential of Ayurvedic herb Kalmegh (Andrographis paniculata) against respiratory viral infections–LC–MS/MS and network pharmacology analysis. Phytochem Anal. (2021) 32:629–39. doi: 10.1002/pca.3011

33. Das M, Ansari KM, Dhawan A, Shukla Y, Khanna SK. Correlation of DNA damage in epidemic dropsy patients to carcinogenic potential of argemone oil and isolated sanguinarine alkaloid in mice. Int J Cancer. (2005) 117:709–17. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21234

34. Prabhakaran D, Senthamilselvi MM, Rajeshkanna A. Anticancer activity of Argemone mexicana L.(flowers) against human liver cancer (HEPG2) cell line. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. (2017) 10:351–53. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i10.20744

35. Chang YC, Chang FR, Khalil AT, Hsieh PW, Wu YC. Cytotoxic benzophenanthridine and benzylisoquinoline alkaloids from Argemone mexicana. Z Für Naturforschung C. (2003) 58:521–6. doi: 10.1515/znc-2003-7-813

36. Gacche RN, Shaikh RU, Pund MM. In vitro evaluation of anticancer and antimicrobial activity of selected medicinal plants from Ayurveda. Asian J Trad Med. (2011) 6:1–7.

37. Gali Kiranmayi GK, Ramakrishnan G, Kothai R, Jaykar B. In-vitro anti-cancer activity of methanolic extract of leaves of Argemone mexicana Linn. Int J PharmTech Res. (2011) 3:1329–33.

38. Uddin SJ, Grice ID, Tiralongo E. Cytotoxic effects of Bangladeshi medicinal plant extracts. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern Med. (2011) 2011:1–7. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep111

39. Singh S, Verma M, Malhotra M, Prakash S, Singh TD. Cytotoxicity of alkaloids isolated from Argemone mexicana on SW480 human colon cancer cell line. Pharm Biol. (2016) 54:740–5. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1073334

40. Liu Y, Liu C, Kou X, Wang Y, Yu Y, Zhen N, et al. Synergistic hypolipidemic effects and mechanisms of phytochemicals: a review. Foods. (2022) 11:p.2774. doi: 10.3390/foods11182774

41. Monterrosas-Brisson N, Zagal-Guzmán M, Zamilpa A, Jiménez-Ferrer E, Avilés-Flores M, Fuentes-Mata M, et al. Effect of argemone mexicana on local edema and LPS-induced neuroinflammation. Chem Biodiversity. (2021) 18:e2000790. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.202000790

42. Zinatizadeh MR, Schock B, Chalbatani GM, Zarandi PK, Jalali SA, Miri SR. The Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-kB) signaling in cancer development and immune diseases. Genes Dis. (2021) 8:287–97. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.06.005

43. Jung J, Koh S, Lee K. The TNF-α-induced protein 3-interacting protein1 (TNIP1) suppresses HGF mediated NF-kB pathway activation and growth in gastric cancer cells. Cancer Res. (2024) 84:6003–3. doi: 10.21873/cgp.20449

44. Ahmad A, Biersack B, Li Y, Kong D, Bao B, Schobert R, et al. Targeted regulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling by indole compounds and their derivatives: mechanistic details and biological implications for cancer therapy. Anti-Cancer Agents Medicinal Chem (Formerly Curr Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents). (2013) 13:1002–13. doi: 10.2174/18715206113139990078

45. El-Hanboshy SM, Helmy MW, Abd-Alhaseeb MM. Catalpol synergistically potentiates the anti-tumour effects of regorafenib against hepatocellular carcinoma via dual inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB and VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathways. Mol Biol Rep. (2021) 48:7233–42. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06715-0

46. Tang Q, Cao H, Tong N, Liu Y, Wang W, Zou Y, et al. Tubeimoside-I sensitizes temozolomide-resistant glioblastoma cells to chemotherapy by reducing MGMT expression and suppressing EGFR induced PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB-mediated signaling pathway. Phytomedicine. (2022) 99:154016. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154016

Keywords: anti-cancer, mexican poppy, colon cancer, medicinal plants, PI3/AKT pathway, skin cancer

Citation: Kulshrestha S, Goel A, Banerjee S, Sharma R, Khan MR and Chen K-T (2024) Metabolomics and network pharmacology–guided analysis of TNF-α expression by Argemone mexicana (Linn) targeting NF-kB the signalling pathway in cancer cell lines. Front. Oncol. 14:1502819. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1502819

Received: 27 September 2024; Accepted: 04 November 2024;

Published: 02 December 2024.

Edited by:

Sandip Patil, Shenzhen Children’s Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Manzar Alam, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Kulshrestha, Goel, Banerjee, Sharma, Khan and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anjana Goel, YW5qYW5hLmdvZWxAZ2xhLmFjLmlu; Kow-Tong Chen, a3RjaGVuQG1haWwubmNrdS5lZHUudHc=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.