- 1Department of Gynecology, The Affiliated Changzhou Second People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Changzhou, China

- 2Suqian First People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Suqian, Jiangsu, China

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China

Lymphoma is a malignant tumour of the lymphatic system with an incidence rate of about 6.6 per 100,000 people. Among the many lymphoma types, the most common is non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Lymphomas are common in the gastrointestinal tract, breast, neck, etc., while those in female genital tracts are rare. In this article, we report four cases of primary female genital system lymphoid malignancies diagnosed and treated at our hospital from 2018 to 2023, with a systematic review.

1 Background

Lymphoma is a general term for a group of malignant tumours of the lymphohematopoietic system with an incidence rate of approximately 6.6 per 100,000 people. Specifically, 90% of them are non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (1). Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma can occur in or outside the lymph nodes and usually presents as a progressively enlarged, painless mass. The most lymphoma-prone sites are the gastrointestinal tract, neck, and central nervous system, but rarely the lymphoma may also occur in sites such as liver, lung, and bladder. Approximately 0.5% to 1.5% of extranodal lymphomas are found in the female reproductive system, of which 75% are of the primary type (1, 2). According to statistical analysis, female genital lymphomas are most commonly found in the ovary, cervix, and uterus (2). We will report one case of primary uterine lymphoma with uterine lesions as the first symptom, two cases of asymptomatic primary ovarian lymphoma, and one case of vulvar lymphoma (See Tables 1, 2 for details).

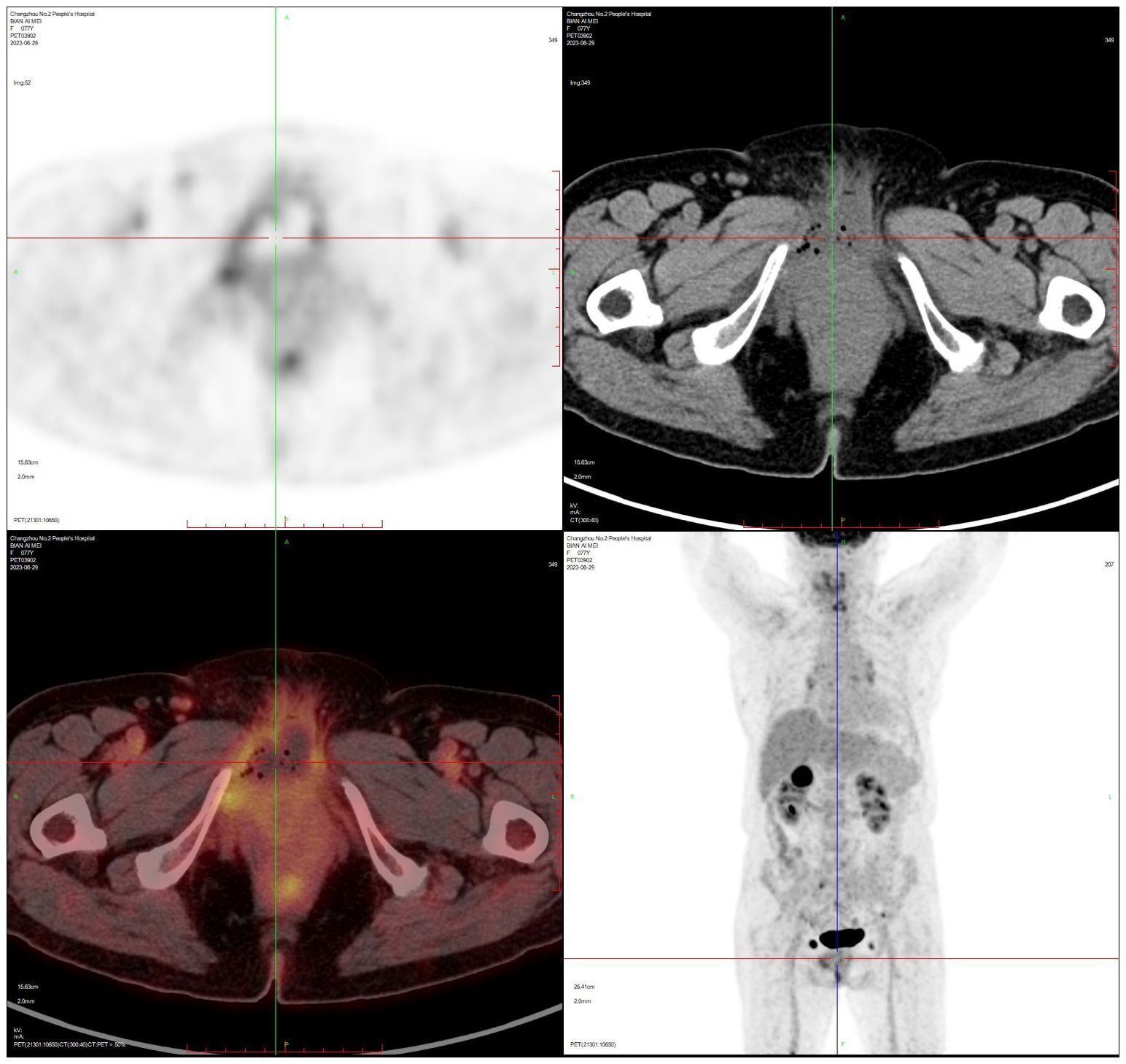

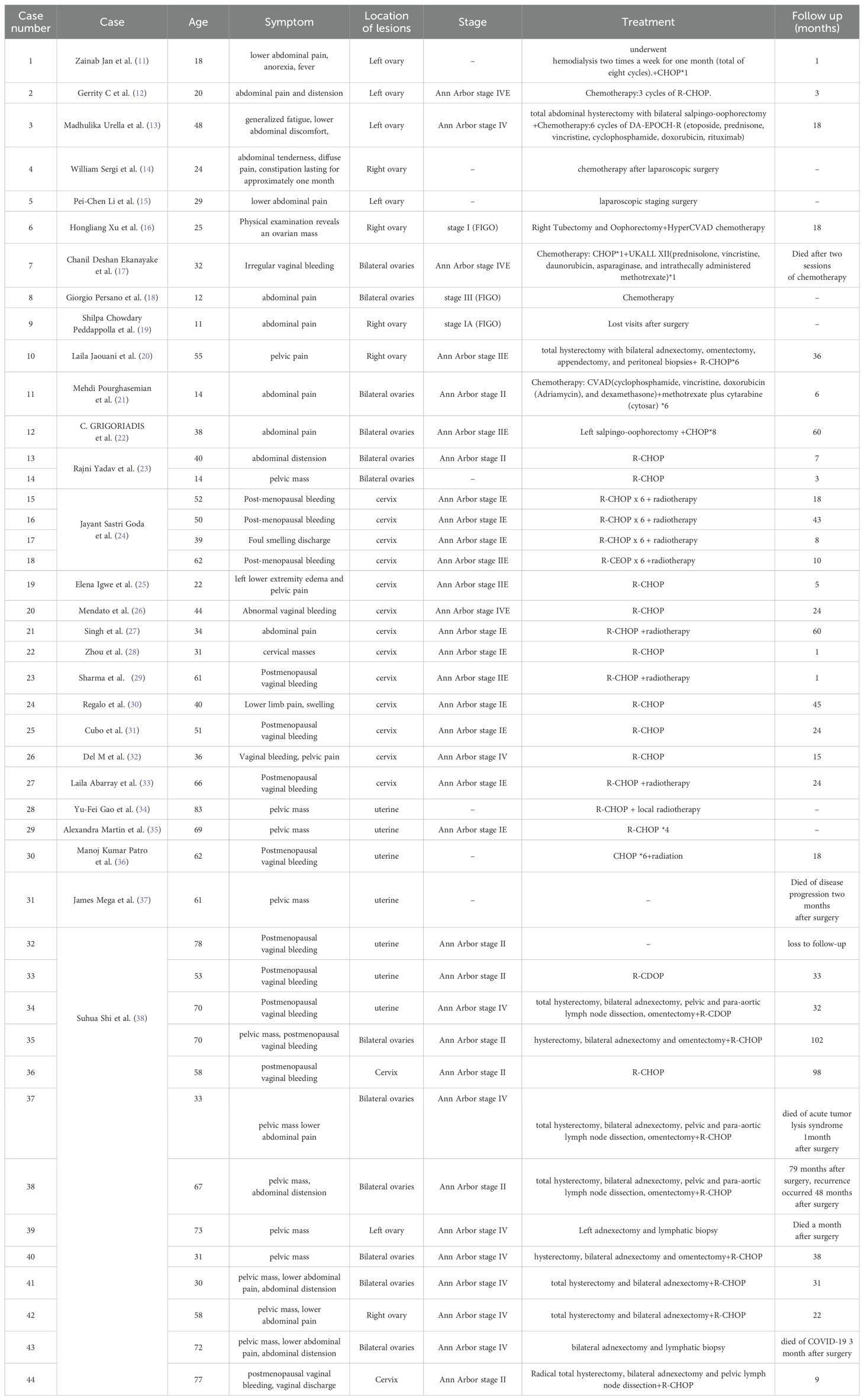

Table 1. Clinical characteristics, laboratory investigations, surgical approach and postoperative pathology in four patients.

Table 2. Postoperative immunohistochemistry, PET-CT, staging, treatment and prognosis in 4 patients.

2 Case presentation

2.1 Case 1

The patient, female, 66 years old, was admitted to the hospital because of “postmenopausal vaginal bleeding for 1 year”. The ultrasound showed that the uterus was about 9.0×7.8×8.6 cm in size, and the mixed echoes in the uterine cavity were about 4.9×0.7cm. The relevant examinations before hospitalisaiton were completed, and the lactic acid dehydrogenase was 264 U/L. Other examinations such as tumour indexes did not show any obvious abnormality. The patient underwent hysteroscopy at our hospital, during which the uterine cavity was found to be filled with dark red cauliflower-like tissue (see Figure 1). After diagnostic scraping, the sample was sent to pathology.

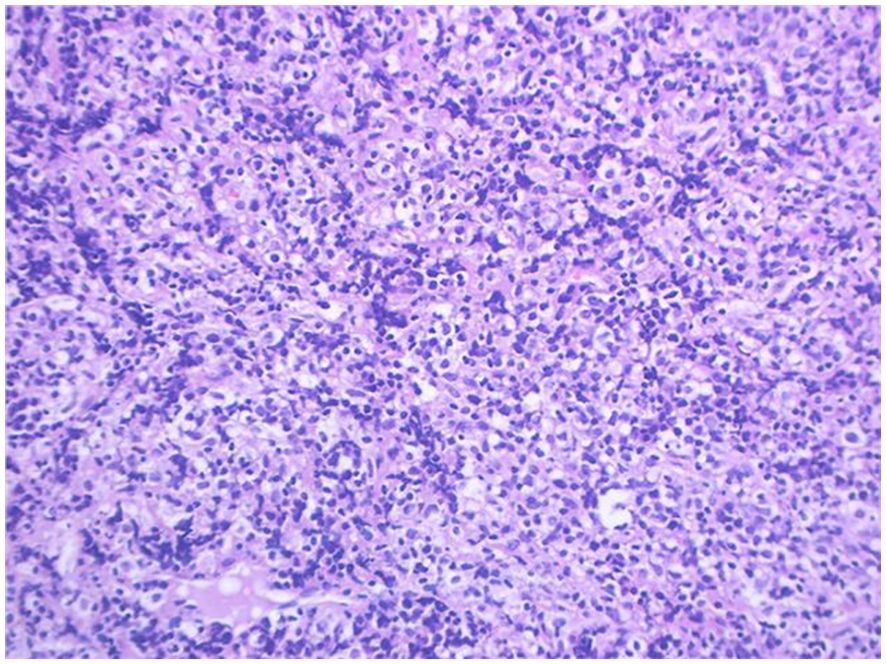

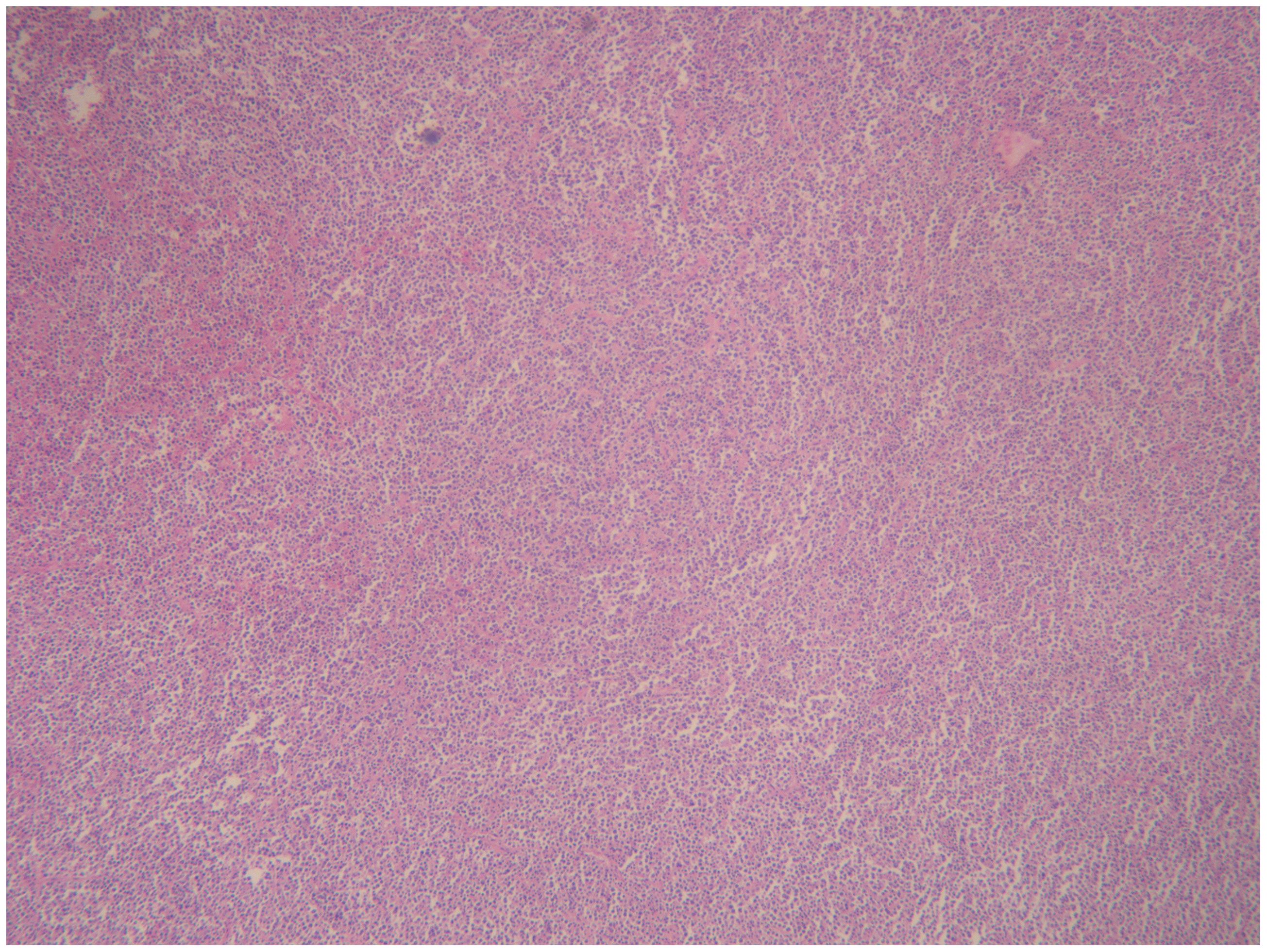

Pathology + immunohistochemistry: Diffuse tumour cells with a predilection for the lymphohematopoietic system (see Figure 2). cD20 (+), cD79a (+), cD3 (-), cD5 (-), KI-67 (+, 80%), BCL-2 (+, 80%), cD10 (+), Bcl-6 (+), Mum-1 (+), c-Myc (+, 30%), EBER (-), EBER (-), EBER (+, 30%) EBER (-), CD21 (-), CyclinD1 (+), CD23 (-).

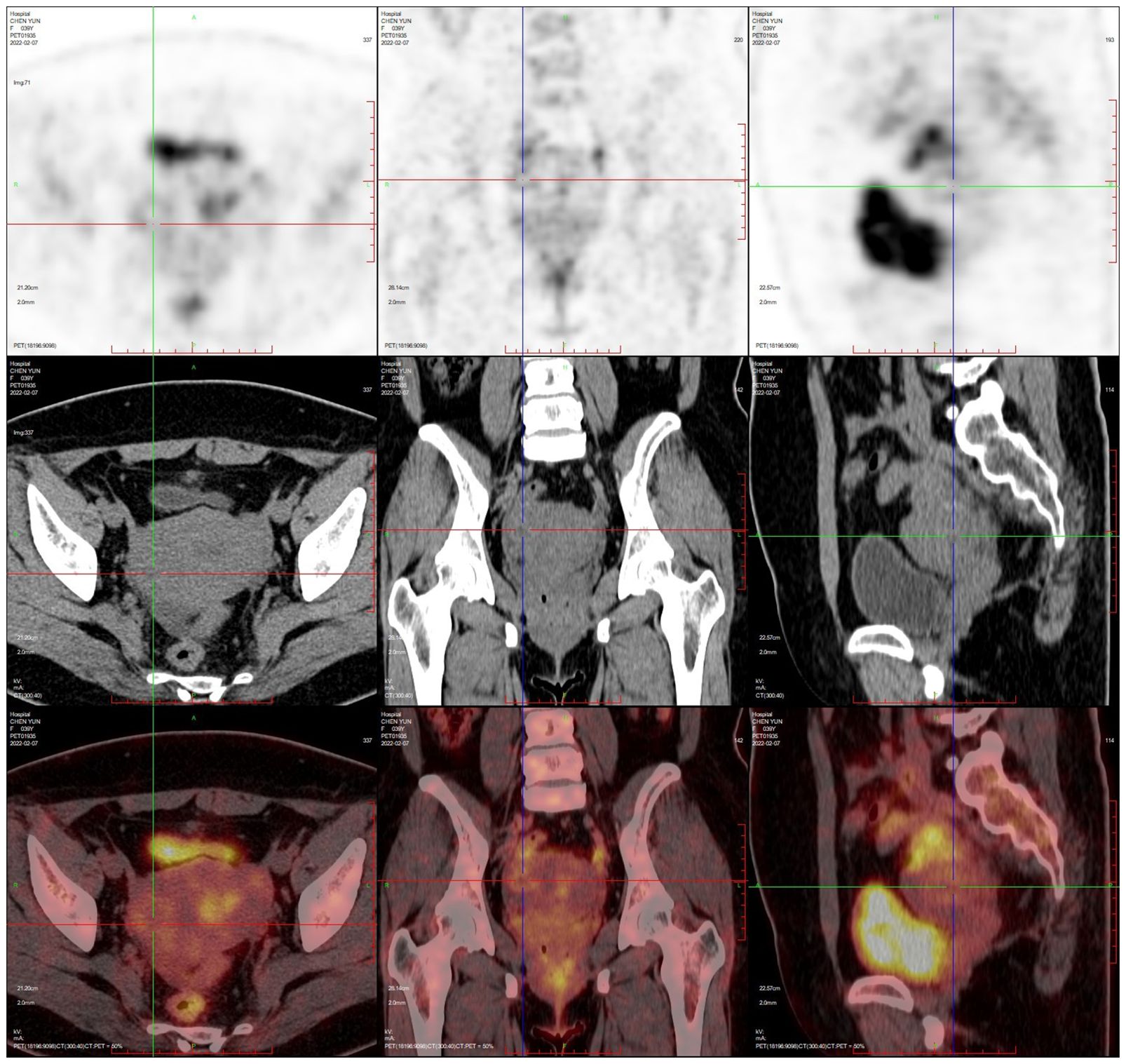

PET-CT (after hysteroscopy): 1. Enlarged uterus with increased glucose metabolism, and malignant lesions were considered. Follow-up was recommended in the left external iliac paravascular and both inguinal lymph nodes. 2. Systemic bone marrow diffuse increased glucose metabolism (see Figure 3).

The patient underwent immunochemotherapy with the R-CHOP regimen in our hematology department. The specific regimen was: rituximab 600mgd0, cyclophosphamide 0.8g d1, epirubicin 80mg d1, vinblastine 3mg d1, and prednisone 40mg bid d1-d5. She has now had six courses of chemotherapy and is stable. There was no evidence of relapse at the one-year reexamination after chemotherapy.

2.2 Case 2

The patient, female, 40 years old, was admitted to the hospital on 2022-01-16 because of “adnexal mass gradually increasing for 1 year”. The ultrasound showed that there were multiple fibroids in the uterus and an uneven mass of 7.1×4.7cm in the right adnexal region. The relevant examinations before hospitalisaiton were completed. LDH: 195 U/L. No obvious abnormality in other investigations such as tumour index was found. Laparoscopic myomectomy + ovarian tumour debulking was performed.

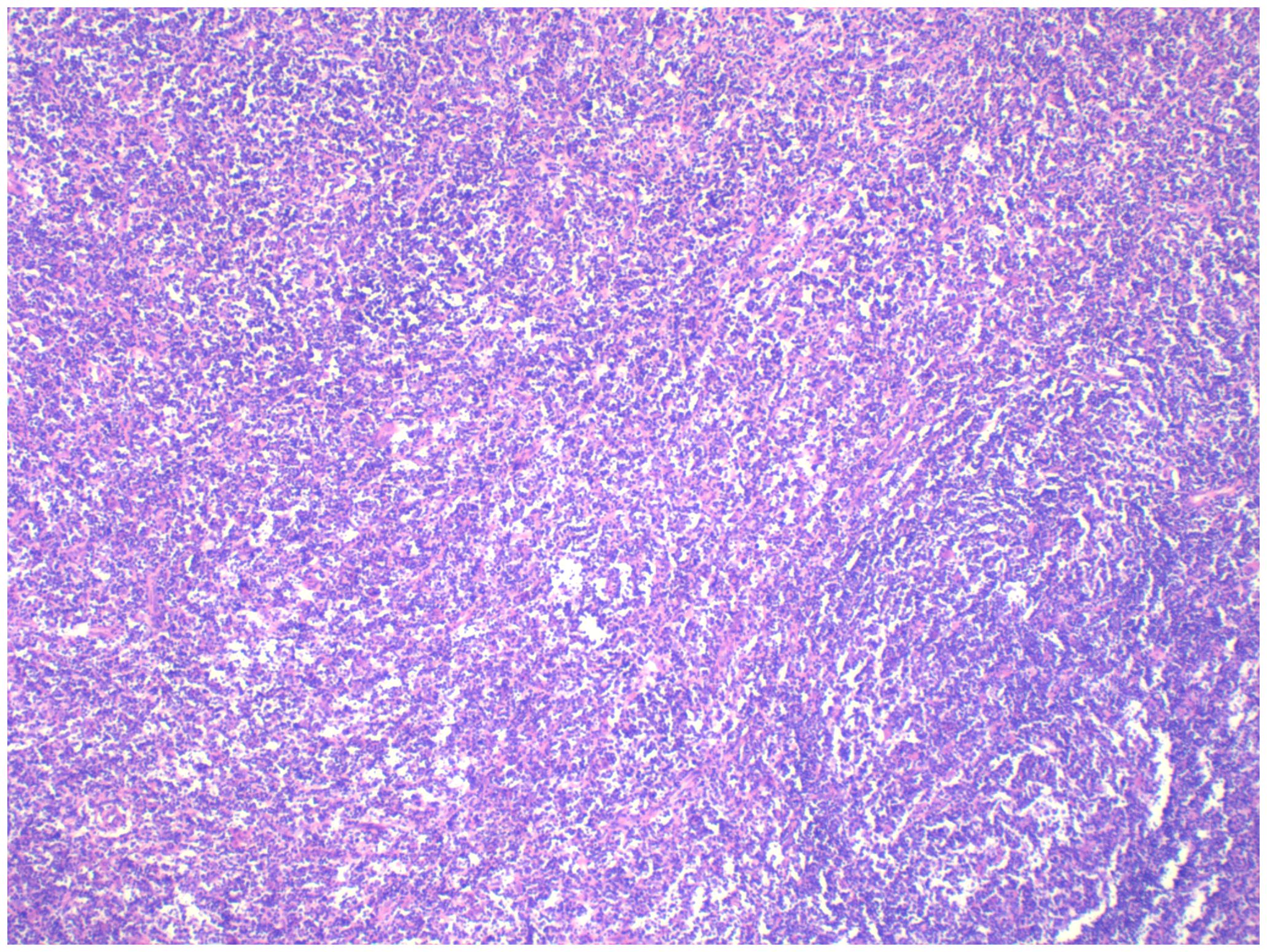

Pathology: The right ovarian tumour was considered to be malignant lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell type, with a T-cell-rich background (see Figure 4).

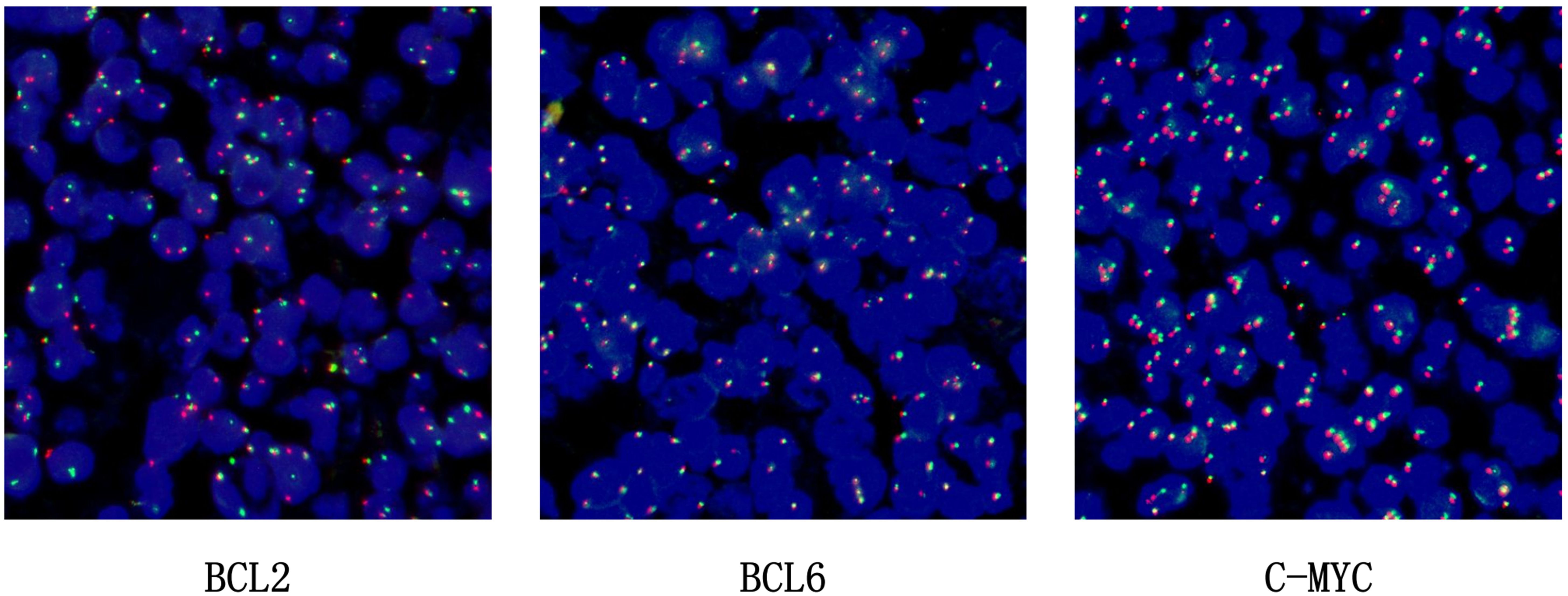

BCL2 probe: The BCL2 gene in the tumour cells showed a ratio of one red, one green, and one yellow accounting for more than 30%, indicating that the BCL2 gene had been broken and recombined. BCL6 showed no obvious abnormality and the c-MYC gene was amplified, not broken and recombined (see Figure 5).

Immunohistochemistry: CD20 (+) CD79α (+) Pax5 (+) CD3 (partially +) CD5 (partially +) Ki-67 (+, 40%) bcl-2 (+) bcl-6 (+) CD10 (+) Mum-1 (-) CD23 (+) C-myc (+, 5%) EBER (-) CKp (-) EMA (-) CD30 (+) CD15 (-) CyclinD1 (-) CD4 (partially +) CD8 (partially +) CD43 (partially +) ALK-Ventana D5F3 (-).

Ovarian pathology section Genotyping - IGH + genotyping TCRD + fusion gene - rearrangement: IGH gene rearrangement: positive; IGK gene rearrangement: positive; TCRβ gene rearrangement: positive.

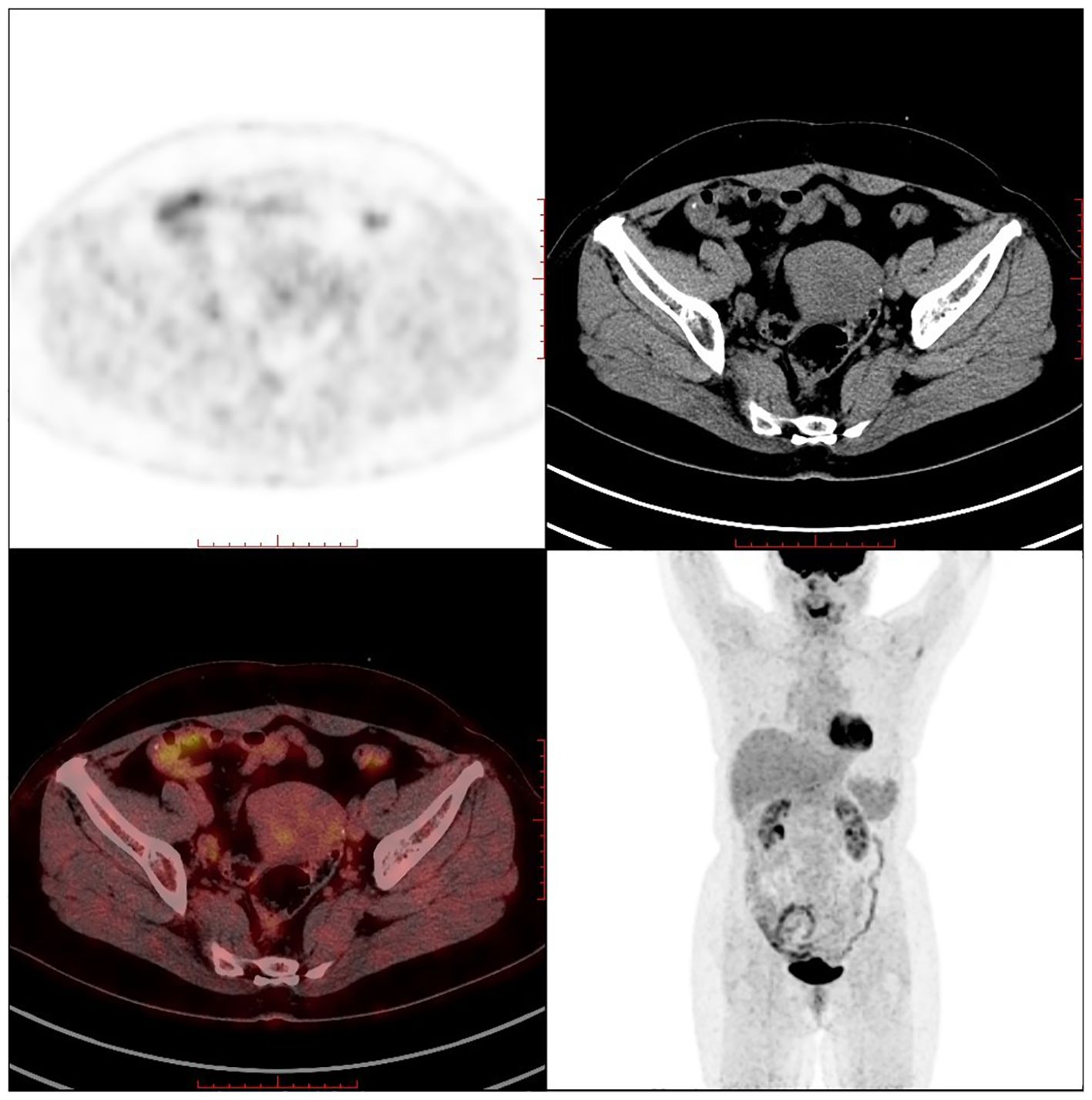

PET-CT (postoperative): 1. Postoperative changes of uterine fibroids and right ovarian tumour debulking; pelvic effusion; 2. Multiple retroperitoneal lymph node shadows with fuzzy thickening of the fat interstitial space in the root of the mesentery, measuring approximately 1.6×0.9cm, with a maximum SUV value of approximately 1.8 (see Figure 6).

The patient underwent six cycles of R-CHOP intravenous immunochemotherapy in the hematology department within 6 months of surgery. The specific regimen was rituximab 700mg d0, epirubicin liposome 120mg d1, vincristine 4mg d1, cyclophosphamide 1.35g d1, and prednisone 50mg bid d1-5. The patient’s lymphoma was stable after two years of regular check-ups at our hospital, with no signs of recurrence.

2.3 Case 3

The patient, female, 58 years old, underwent ovarian tumour subtraction in our hospital on 2018-06-13 due to “discovery of gradual enlargement of bilateral adnexa for 6 months”. Postoperative pathology: Left ovary 4.5×3.5×3.5cm, right adnexa 7.5×7×4cm, which is in line with diffuse large B lymphoma symptom. Immunohistochemistry: Tumour cells CD20 (+), Bcl-2 (+, 70%), C-myc (+, 10%), Bcl-6 (+), CD3 (-) Ki-67+ (+, 80%), MUM (+), CD10 (-). FISH: No c-MYC gene translocation, no Bcl-2 gene translocation, and BCL6 gene related translocation. The patient received postoperative PET-CT re-examination in our hospital: After the bilateral ovarian lymphoma surgery, retroperitoneal and bilateral iliac paravascular lymph nodes were invaded (see Figure 7).

The patient underwent six times of R-CHOP intravenous immunochemotherapy in the hematology department within 6 months of surgery. The specific regimen was rituximab 600mg d0, doxorubicin hydrochloride liposome 81.5mg d1, vincristine 3mg d1, cyclophosphamide 1.22g d1, and prednisone 50mg bid d1-5. The patient has been followed up regularly in our hospital for three years after chemotherapy, and no recurrence of lymphoma has been observed, and her current lymphoma status is stable.

2.4 Case 4

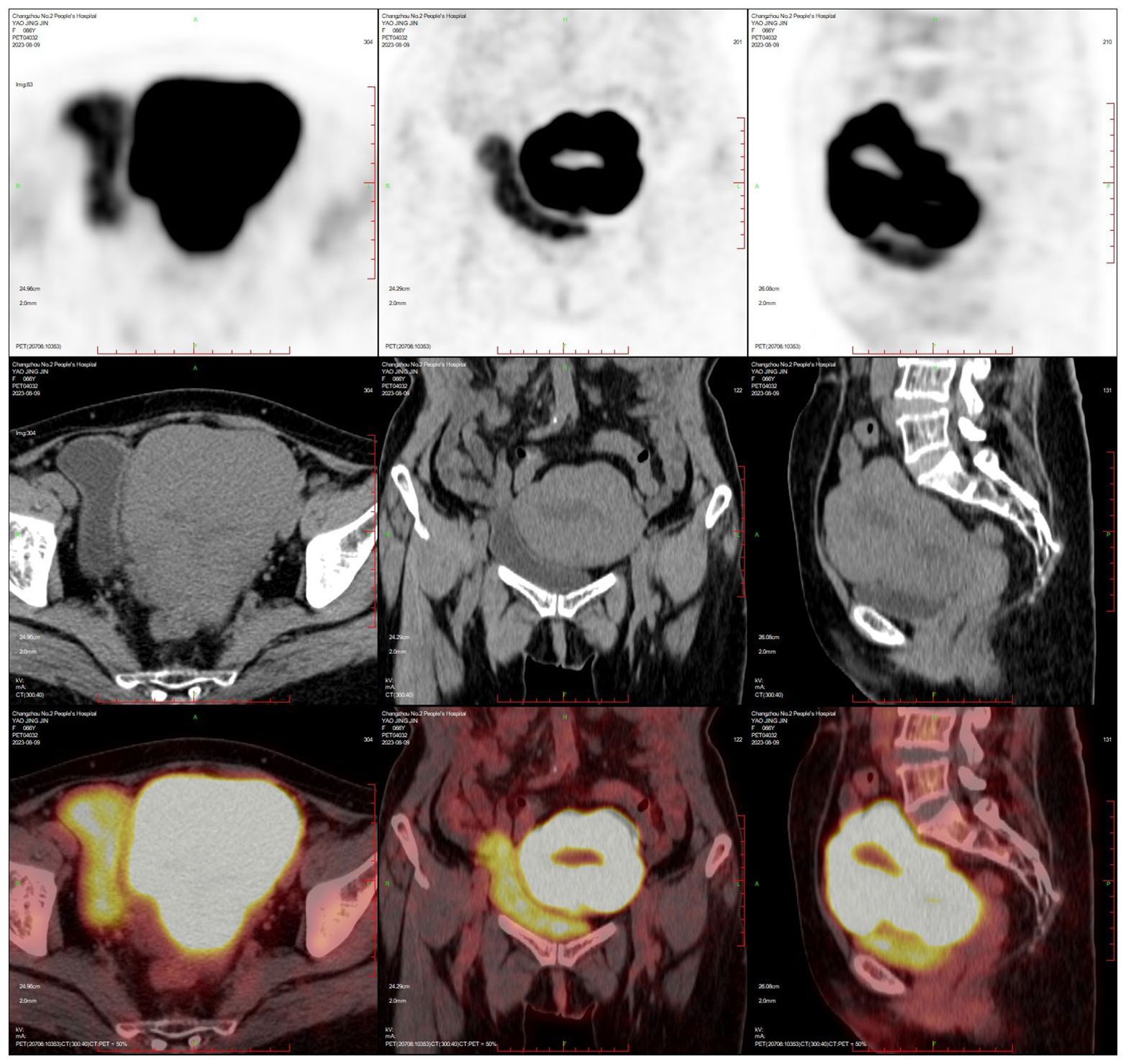

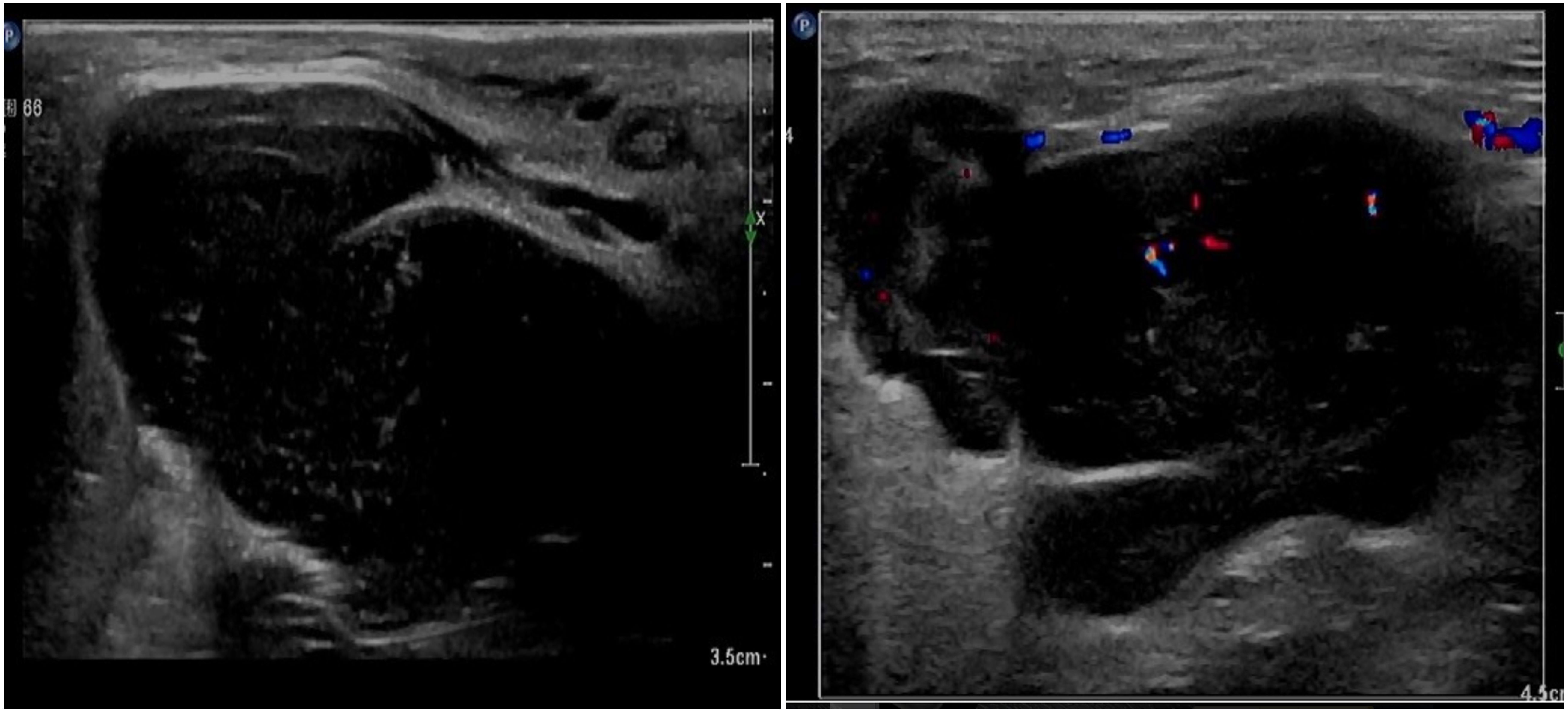

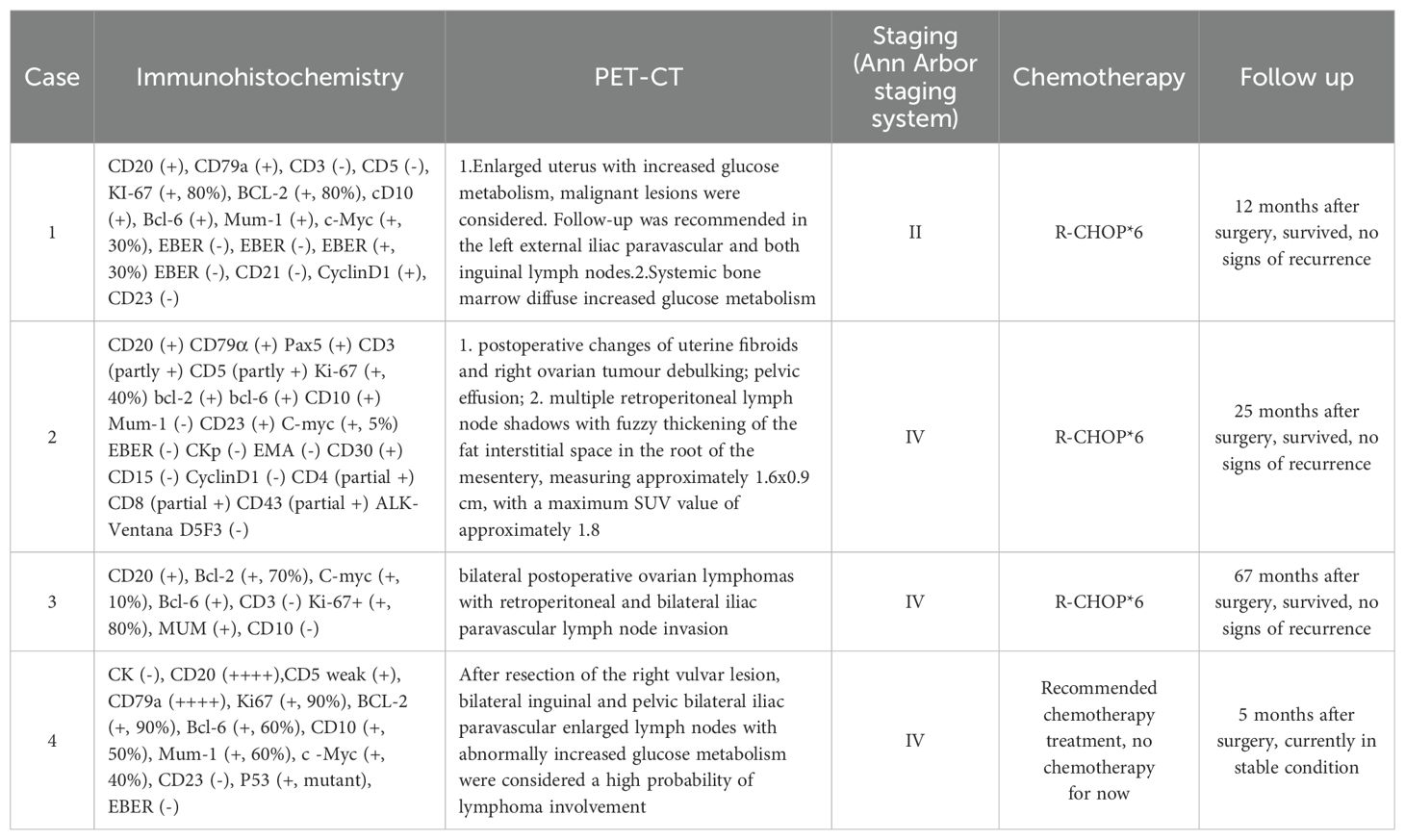

The patient, female, 77 years old, underwent vulvovaginal lesion excision in our hospital on 2023-06-13 for a “1-month-old vulvovaginal mass with swelling and pain”. Preoperative superficial mass (see Figure 8): Mixed echoes of about 5.7×2.9cm in size were seen under the perineal skin and blood flow signal was visible. Intraoperatively, a mass of about 4×4×4.5cm was seen on the external labia majora of the mons pubis, with a hard texture, poor mobility, and deep to the surface of the descending branch of the pubic bone and the pubic symphysis. After complete excision of the mass, a section view showed that the section surface was fish-like with a brittle texture. Postoperative pathology: (Vulvar mass) Highly aggressive B-cell lymphoma (see Figure 9), immunohistochemistry: CK (-), CD20 (++++), CD5 weak (+), CD79a (++++), Ki67 (+, 90%), BCL-2 (+, 90%), Bcl-6 (+, 60%), CD10 (+, 50%), Mum-1 (+, 60%), c-MYC (+, 40%), CD23 (-), P53 (+, mutant), EBER (-). Postoperative PET-CT (see Figure 10): After resection of the right vulvar lesion, the patient’s bilateral inguinal and pelvic bilateral iliac paravascular enlarged lymph nodes showed abnormally increased glucose metabolism, which was considered lymphoma involvement of a high probability.

3 Discussion

Lymphoma is a malignant tumour that originates in the lymph nodes or extra-nodal lymphoid tissues, and can be classified according to its pathology into Hodgkin’s lymphoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It can occur in a variety of sites and in any organ of the body. Studies have shown that about 30% of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas occur outside the lymph nodes and are most commonly seen in the gastrointestinal tract and neck (3). Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas originating in the female reproductive system accounts for only 0.5%–1.5% of extranodal cases, including the ovary (37%), cervix (21.4%), uterus (16.5%), vagina (11.8%), and vulva (8.8%) (4). Currently, the criteria proposed by Vang et al. for primary genital lymphoma are still in use: (1) Patient has no previous history of lymphoma. (2) The patient’s primary disease is in the genital system and may involve adjacent genital organs or lymph nodes. (3) Hemorrhagic abnormal cells are present in the peripheral blood or spinal cord. (4) If recurrent lymphoma occurs at a distant site, the time gap between it and the primary lymphoma must be longer than 6 months (5).

3.1 Primary ovarian lymphoma

The ovary is the most common site of female genital lymphomas and the clinical presentation is variable. A painless adnexal or pelvic mass that gradually increases in size is usually the first symptom, and the mass is usually large and easily distorted, causing abdominal pain. It may be accompanied by abdominal distension, uterine bleeding, or local symptoms such as frequent urination and constipation due to pressure on surrounding organs. Systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss may also be present (6). Patients tend to have elevated lactate dehydrogenase and CA125 in most reported cases (7). Histopathology is the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of ovarian lymphoma. In immunohistochemistry of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of the ovary, CD10, CD19, CD20, and CD22 are all positive, indicating that B cells are in a high expression status. Besides, the following conditions should be met during the diagnostic period: 1. MYC gene breakpoints and rearrangements. 2. CD10 (+). 3. Ki-67 value at 90%. 4. Absence of BCL-2 expression (8).

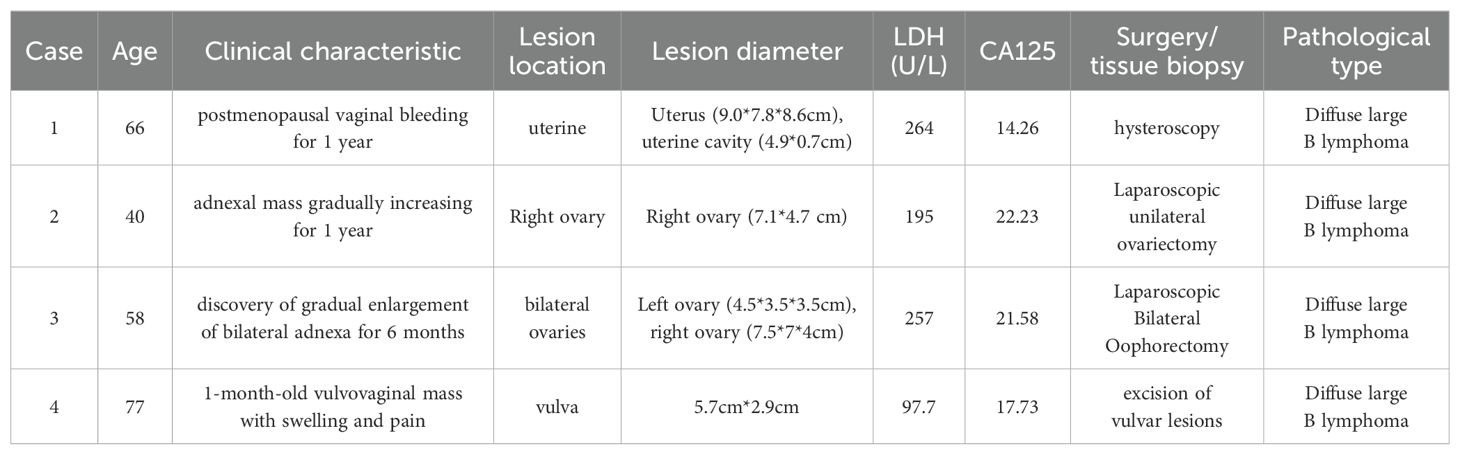

Currently, the treatment of ovarian lymphoma is mainly a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Preoperative diagnosis of ovarian lymphoma is usually difficult, so we usually treat it surgically first, and then chemotherapy with R-CHOP regimen after surgery. There remains a big difference between domestic and foreign countries on adoption of complete tumour reduction surgery, and foreign countries believe that surgery plays an important role in providing a diagnostic basis (7). In contrast, the domestic circle believes that reducing the size of the primary lesion as much as possible by removing the uterus, greater omentum, and bilateral fallopian tubes and ovaries will improve the prognosis (9). Primary ovarian lymphoma has a better prognosis. According to a recent study, the 5-year survival rate of patients receiving primary ovarian lymphoma treatment can reach 80% (10). Treatment and prognosis of selected primary ovarian lymphomas are shown in Table 3 (11–38).

3.2 Primary lymphoma of the uterine cervix

Uterine cervical lymphoma accounts for 0.008% of cervical malignancies (26). Its main clinical manifestations are vaginal bleeding and increased discharge. Uterine cervical exfoliative cytology is usually used as the primary screening test for cervical malignancy. However, it is difficult to diagnose cervical lymphoma, probably because lymphoma originates from the mesenchyme, which is covered by a layer of epithelial cells, and its anisotropic cells are not easy to obtain at an early stage (39, 40). Therefore, biopsy with immunohistochemistry is usually used to confirm the diagnosis of cervical lymphoma.

But no consensus has been reached regarding the best treatment of this disease due to its rarity. According to several studies, chemotherapy ± radiotherapy is the main treatment for primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of the cervix. This treatment can achieve complete remission with a 5-year survival rate of 80% (24, 29). For young female patients with fertility requirements, the treatment is usually chemotherapy + immunotherapy to reduce the damage to fertility caused by radiotherapy or surgery (41). Hysterectomy and radical surgery are not preferred and there is no evidence that surgical patients have a better prognosis (1, 6, 41). Treatment and prognosis of selected primary lymphoma of the uterine cervix are shown in Table 3 (11–38).

3.3 Primary uterine lymphoma

Primary uterine lymphoma usually occurs in postmenopausal women. Its main clinical manifestations are postmenopausal vaginal bleeding, increased menstrual flow, and abnormal uterine bleeding. The uterus of patients with this type of disease usually enlarges progressively over a short period of time (42). Uterine lymphoma is diagnosed in the same way as cervical lymphoma - diagnostic curettage and endometrial biopsy. In the case of deeper tumours, the test result may be negative. Therefore, the diagnosis needs to be confirmed by a combination of clinical symptoms, imaging, laboratory, and hysteroscopy to exclude other disease diagnoses (43).

There is still no standard protocol for treating primary uterine lymphoma. Some studies have shown that surgery combined with chemotherapy has a better prognosis, while postoperative combined radiotherapy has a worse prognosis (44). Patients with primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) can be treated with total hysterectomy with preservation of the ovaries and postoperative R-CHOP chemotherapy. In patients with fertility needs, if the diagnosis is clear before surgery, chemotherapy can be used to achieve clinical remission and avoid postoperative complications (6, 43). The prognosis of primary uterine lymphoma is poor, with a median survival of only 19.6 months and a 5-year survival rate of 25%, according to the literature (45). Treatment and prognosis of selected primary uterine lymphoma are shown in Table 3 (11–38).

3.4 Primary vulvar lymphoma and vaginal lymphoma

Primary vulvar lymphoma and vaginal lymphoma are rare. Clinical manifestations usually include vaginal bleeding, prolapse of intravaginal masses, and formation of vulvar masses, which may be accompanied by local redness, swelling, pain, and ulceration. The standard treatment for vulvar and vaginal lymphoma is chemotherapy. The R-CHOP regimen is used in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and challenges remain in the treatment of relapsed lymphoma (46, 47).

4 Summary and outlook

Female genital lymphomas are relatively rare in clinical practice, and the clinical manifestations are not typical. In this paper, we present four cases who were admitted to the hospital with symptoms of increased adnexal mass, postmenopausal vaginal bleeding, and vulvar mass. The pathology suggested primary malignant genital tract lymphoma in the course of diagnosis and treatment, and the patients were treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy in our hospital after surgery. Their lymphomas are all in stable stage at present. Primary large B cell lymphoma in female genital tract was treated following individualized treatment plans through multidisciplinary consultation, taking into account the primary site, patient’s age, fertility requirements, physical condition, and other conditions. Chemotherapy with the R-CHOP regimen was the primary treatment, supplemented by surgical treatment. The surgical treatment aimed at reducing the tumour load, and radiotherapy was not recommended as the standard and preferred treatment option. The limitations of this study lie in the relative rarity of female genital lymphomas, which makes it difficult to conduct a prospective study. Besides, this study has a small sample size and acts as a retrospective study only. We reviewed these four cases systematically to improve our clinical understanding of this type of disease. This will help us reduce omission and misdiagnosis, facilitate early diagnosis and treatment, improve patients’ quality of life, and increase their survival rate during future diagnosis and treatment of this type of disease. If possible, joint multi-center large-sample data studies can be conducted in future to explore and clarify key clinical diagnostic and treatment points of female genital lymphomas, so as to enhance clinicians’ comprehensive understanding of this disease and its diagnosis and treatment effectiveness.

Author contributions

QJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. TH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. ZD: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. WC: Writing – review & editing. MC: Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing. WW: Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by grants from Top Talent of Changzhou “The 14th Five-Year Plan” High-Level Health Talents Training Project (2022CZBJ074), the maternal and child health key talent project of Jiangsu Province (RC202101), the maternal and child health research project of Jiangsu Province (F202138), the Scientific Research Support Program for Postdoctoral of Jiangsu Province (2019K064), and the Scientific Research Support Program for “333 Project” of Jiangsu Province (BRA2019161).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Capsa C, Calustian LA, Antoniu SA, Bratucu E, Simion L, Prunoiu VM. Primary non-hodgkin uterine lymphoma of the cervix: A literature review. Medicina (Kaunas). (2022) 58:106. doi: 10.3390/medicina58010106

2. Hilal Z, Hartmann F, Dogan A, Cetin C, Krentel H, Schiermeier S, et al. Lymphoma of the cervix: case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. (2016) 36:4931–40. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11059

3. Vannata B, Zucca E. Primary extranodal B-cell lymphoma: current concepts and treatment strategies. Chin Clin Oncol. (2015) 4:10. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3865.2014.12.01

4. Nasioudis D, Kampaktsis PN, Frey M, Witkin SS, Holcomb K. Primary lymphoma of the female genital tract: An analysis of 697 cases. Gynecol Oncol. (2017) 145:305–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.02.043

5. Vang R, Medeiros LJ, Fuller GN, Sarris AH, Deavers M. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving the gynecologic tract: a review of 88 cases. Adv Anat Pathol. (2001) 8:200–17. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200107000-00002

6. Zhang Yi, Tian D, Li F, Wang J, Zhang S. Chinese expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the female genital tract (2023 edition). Cancer Prog. (2023) 21:1045–1049 + 1053.

7. Stepniak A, Czuczwar P, Szkodziak P, Wozniakowska E, Wozniak S, Paszkowski T. Primary ovarian Burkitt’s lymphoma: a rare oncological problem in gynaecology: a review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2017) 296:653–60. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4478-6

8. Haralambieva E, Boerma EJ, van Imhoff GW, Rosati S, Schuuring E, Müller-Hermelink HK, et al. Clinical, immunophenotypic, and genetic analysis of adult lymphomas with morphologic features of Burkitt lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. (2005) 29:1086–94. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000168176.71405.e5

9. Wu J, Ji W, Shi C, Chang S, Wang M. Clinical analysis of 32 cases of primary ovarian non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Chin J Pract Gynaecology Obstetrics. (2013) 29:359–63.

10. Yun J, Kim SJ, Won JH, Choi CW, Eom HS, Kim JS, et al. Clinical features and prognostic relevance of ovarian involvement in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) report. Leuk Res. (2010) 34:1175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.02.010

11. Jan Z, Khan AU, Ilyas A, Faiz S. Primary ovarian burkitts lymphoma. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. (2023) 35:S807–9. doi: 10.55519/JAMC-S4-12410

12. Gerrity C, Mercadel A, Alghamdi A, Huang M. Primary ovarian lymphoma: A case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. (2023) 47:101212. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2023.101212

13. Urella M, Nwanwene K, Sidda A, Pacioles T. A rare case of ovarian double-hit/diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A case report and review of literature. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. (2023) 11:23247096231154641. doi: 10.1177/23247096231154641

14. Sergi W, Marchese TRL, Botrugno I, Baglivo A, Spampinato M. Primary ovarian Burkitt’s lymphoma presentation in a young woman: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2021) 83:105904. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.105904

15. Li PC, Lim PQ, Hsu YH, Ding DC. Ovarian diffuse large B-cell lymphoma initially suspected dysgerminoma managed by laparoscopic staging surgery. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. (2020) 9:162–5. doi: 10.4103/GMIT.GMIT_79_19

16. Xu H, Zhao C, Wang Q, Chen Y, Zhang W, Zhuang Y, et al. Primary ovarian Burkitt lymphoma: report of a case and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. (2022) 15:110–9.

17. Ekanayake CD, Punchihewa R, Wijesinghe PS. An atypical presentation of an ovarian lymphoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. (2018) 12:338. doi: 10.1186/s13256-018-1884-8

18. Persano G, Crocoli A, Martucci C, Vinti L, Cassanelli G, Stracuzzi A, et al. Case report: Primary ovarian Burkitt’s lymphoma: A puzzling scenario in pediatric population. Front Pediatr. (2023) 10:1072567. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.1072567

19. Peddappolla SC, Pandey U, Shahi UP. Primary unilateral ovarian lymphoma in a young girl: case report. J Obstet Gynaecol India. (2021) 71:541–4. doi: 10.1007/s13224-021-01467-0

20. Jaouani L, Zaimi A, Al Jarroudi O, Berhili S, Brahmi SA, Afqir S. An extranodal site of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as ovarian cancer. Cureus. (2023) 15:e34337. doi: 10.7759/cureus.34337

21. Pourghasemian M, Danandeh Mehr A, Alavizadeh E, Behzadi F, Roosta Y. Primary bilateral ovarian involvement in Burkitt’s lymphoma with an adnexal Torsion-like manifestation: A case report. Clin Case Rep. (2021) 9:e05058. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.5058

22. Grigoriadis C, Tympa A, Chasiakou A, Baka S, Botsis D, Hassiakos D. Bilateral primary ovarian non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and fertility preservation: 5-year follow-up. G Chir. (2017) 38:77–9. doi: 10.11138/gchir/2017.38.2.077

23. Yadav R, Balasundaram P, Mridha AR, Iyer VK, Mathur SR. Primary ovarian non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Diagnosis of two cases on fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytojournal. (2016) 13:2. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.173588

24. Goda JS, Gaikwad U, Narayan A, Kurkure D, Yadav S, Khanna H, et al. Primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma of Uterine Cervix: Treatment outcomes of a rare entity with literature review. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). (2020) 3:e1264. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1264

25. Igwe E, Diaz J, Ferriss J. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the cervix with rectal involvement. Gynecol Oncol Rep. (2014) 10:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2014.07.004

26. Mandato VD, Palermo R, Falbo A, Capodanno I, Capodanno F, Gelli MC, et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the uterus: case report and review. Anticancer Res. (2014) 34:4377–90.

27. Singh L, Madan R, Benson R, Rath GK. Primary non-Hodgkins lymphoma of uterine cervix: a case report of two patients. J Obstet Gynaecol India. (2016) 66:125–7. doi: 10.1007/s13224-014-0647-8

28. Zhou W, Hua F, Zuo C, Guan Y. Primary uterine cervical lymphoma manifesting as menolipsis staged and followed up by FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. (2016) 41:590–3. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001196

29. Sharma V, Dora T, Patel M, Sancheti S, Sridhar E. Case report of diffuse large B cell lymphoma of uterine cervix treated at a semiurban cancer centre in North India. Case Rep Hematol. (2016) 2016:3042531. doi: 10.1155/2016/3042531

30. Regalo A, Caseiro L, Pereira E, Cortes J. Primary lymphoma of the uterine cervix: a rare constellation of symptoms. BMJ Case Rep. (2016) 2016:bcr2016216597. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216597

31. Cubo AM, Soto ZM, Cruz MÁ, Doyague MJ, Sancho V, Fraino A, et al. Primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the uterine cervix successfully treated by combined chemotherapy alone: A case report. Med (Baltimore). (2017) 96:e6846. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006846

32. Del M, Angeles MA, Syrykh C, Martínez-Gómez C, Martínez A, Ferron G, et al. Primary B-Cell lymphoma of the uterine cervix presenting with right ureter hydronephrosis: A case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. (2020) 34:100639. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2020.100639

33. Abarray L, Lahlimi FZ, Ilias T. Primary lymphoma of the uterine cervix: A case report. Niger Med J. (2023) 63:485–8.

34. Gao YF, Wang Y, Wang T, Han LN, Zhang H. A rare case report of primary uterine and vaginal lymphoma in the elderly. J Int Med Res. (2023) 51:3000605221147192. doi: 10.1177/03000605221147192

35. Martin A, Medlin E. Primary, non-germinal center, double-expressor diffuse large B cell lymphoma confined to a uterine leiomyoma: A case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. (2017) 22:78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2017.10.003

36. Patro MK, Bal AK, Santosh T, Mishra B. Primary non-hodgkin’s lymphoma of diffuse large B-cell phenotype [DLBCL] of uterine corpus: A rare case report with brief review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol India. (2016) 66:675–8. doi: 10.1007/s13224-016-0880-4

37. Mega J, O’Brien V, Hammond N, Aeum J, Bunch K. A rare case of metastatic uterine lymphoma in a renal transplant patient. Radiol Case Rep. (2021) 16:3675–9. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2021.08.061

38. Shi S, Li W, Ni G, Ding J, Liu Y, Wu H, et al. Primary lymphoma of the female genital tract masquerading as gynecological Malignancy. BMC Womens Health. (2024) 24:247. doi: 10.1186/s12905-024-03037-8

39. Zhou J, Zhao S, Wu Y, Zou Z, Xi L, Rong R. Clinicopathological analysis of uterine cervical TCT combined with cell wax block immunolabelling for diagnosis of Malignant lymphoma. J Clin Exp Pathol. (2023) 39:350–2. doi: 10.13315/j.cnki.cjcep.2023.03.020

40. Zou H, Fu J, Hu L. Progress in the study of primary Malignant lymphoma of the female reproductive system. J Pract Obstetrics Gynaecology. (2011) 27:339–41.

41. Stabile G, Ripepi C, Sancin L, Restaino S, Mangino FP, Nappi L, et al. Management of primary uterine cervix B-cell lymphoma stage IE and fertility sparing outcome: A systematic review of the literature. Cancers. (2023) 15:3679. doi: 10.3390/cancers15143679

42. Mao J-Y, Yao X-Y, Sheng C-ZYa. Clinicopathological analysis of primary endometrial non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Modern Pract Med. (2010) 22:1034–5.

43. Zhang Z, Yang Q. Primary diffuse large B-cell tumor of the uterus: a case report. Front Med (Lausanne). (2023) 10:1234861. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1234861

44. Chen F, Duan H, Wang K, Xin L, Cheng J. A case report and literature review of primary uterine large B-cell lymphoma. Adv Modern Biomedicine. (2020) 20:3683–6. doi: 10.13241/j.cnki.pmb.2020.19.016

45. Qu F, Liu H, Zhang X. Clinicopathological observation of primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the uterine corpus. J Diagn Pathol. (2007) 03:199–201.

46. Xiao H, Wang Ke. Diagnostic and therapeutic progress of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma originating in the female reproductive system. China Cancer Clinics. (2020) 47:530–4.

Keywords: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, primary female genital system lymphoma, uterine lymphoma, ovarian lymphoma, vulvar lymphoma

Citation: Jia Q, Tang H, Dong Z, Chen W, Chen M, Wei W and Chen J (2024) Malignant primary female genital system lymphoid. Front. Oncol. 14:1438812. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1438812

Received: 26 May 2024; Accepted: 02 September 2024;

Published: 26 September 2024.

Edited by:

Guglielmo Stabile, Institute for Maternal and Child Health Burlo Garofolo (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Apurva Patel, Gujarat Cancer and Research Institute, IndiaChiara Ripepi, University of Trieste, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Jia, Tang, Dong, Chen, Chen, Wei and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiming Chen, Y2ptaW5nQDEyNi5jb20=

†These authors share first authorship

Qiucheng Jia

Qiucheng Jia Huimin Tang

Huimin Tang Zhiyong Dong

Zhiyong Dong Wanying Chen1

Wanying Chen1 Weiwei Wei

Weiwei Wei Jiming Chen

Jiming Chen