95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 22 October 2024

Sec. Pediatric Oncology

Volume 14 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1387905

This article is part of the Research Topic Current Status and Future Directions of Pediatric Palliative Care in Oncology View all 8 articles

Background: Cancer is still the leading cause of non-accidental death in childhood, although the majority of children diagnosed in high-income countries survive their illness. In accordance with international standards, equal and early access to palliative care should be available to children and adults. Yet communication and prognostic disclosure may influence the timing of involvement in palliative care. Purpose: To investigate whether parents perceived that their child received palliative care and to what extent that contrasted parents’ perceptions of their child’s care and symptoms in the last month of life.

Methods: A nationwide population-based parental questionnaire study in Sweden, one to five years after their child’s death (n=226). Descriptive statistics were used.

Results: A majority of parents (70%) reported that they were aware that their child received palliative care and they were informed about the incurable disease (57%) within 3 months before the child died. The most common diagnosis among children receiving palliative care was a brain tumor (45%) with a disease related death (90%) and the care was often received at home (44%). Based on the reports of parents who felt that their child did not receive palliative care, 45% were informed within days or hours about the child’s incurable disease, 45% of these children were diagnosed with leukemia, 60% died at the intensive care unit, and 49% died of treatment-related complications. It was most common for families who lived in urban areas (28%) to report their child received palliative care, in comparison to families living in sparsely populated areas (11%). A significant proportion of parents whose child received palliative care (96%) stated that the healthcare professionals were competent in caring for their child, for those who reported no palliative care it was slightly lower (74%). In both groups many children were affected by multiple symptoms the last month of life.

Conclusions: The study findings highlight the role of understanding parental perceptions of pediatric palliative oncology care, the role of initiating palliative care early, the need of access to national equitable PC and professional competence across the lifespan, regardless of diagnosis and place of residence.

Worldwide, approximately 400 000 children and adolescents aged 0 to 19 are diagnosed with cancer every year (1). Childhood cancer is an example of the group of diseases where a majority of children diagnosed in high-income countries survive their illness today, although survival varies between different diagnoses (2). The cancer-trajectory can be prolonged, the treatment can be intense, and it is not uncommon for the treatment to pose a threat to the child’s well-being and even their life (2). The definition of pediatric palliative care, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1998, was based on experiences of caring for children with cancer. Today, the definition includes all diagnoses and emphasizes the role of active multidimensional care that provides support to all family members and carried out with interdisciplinary competence (3). The World Health Organization recommends that palliative care begins when a life-threatening disease or a life-limiting condition is diagnosed, and continues regardless of whether the child receives targeted treatment or not (3). The International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC) has further developed the WHO definition to clearly encompass all ages, both children and adults. Most importantly, this proposal focuses on the suffering of a person with a severe illness, rather than the life-threatening illness itself (4). In 2007, standards for pediatric palliative care were presented by an international consortium of experts and these standards have recently been updated (5). The threat of losing a child is a profound trauma for parents (6). Regardless of the diagnosis, life changes for the entire family when a child is diagnosed with a life-threatening illness (7). Parents struggle to grasp the information (8) and handle the situation, irrespective of prognosis (9). Research has shown that parents want information in as much detail as is possible, even when the prognosis is uncertain or the disease is incurable (10–12). The timing of conversations imparting bad news is crucial. Sometimes parents are informed too late, or not informed at all, that their child might not survive (11).

In Sweden, around 350 children and adolescents (under 19 years old) are diagnosed with cancer each year, and approximately 60 die from the disease or treatment-related complications. The Swedish healthcare model has a decentralized structure with 21 county councils, is tax-financed and different healthcare services provide palliative care. The care is based on a regional and local organization, including specialized and primary palliative caregivers (13, 14). The majority of children in need of palliative care have access to specialized services; however, Sweden has only one hospice for children. This means that there is varying access to pediatric palliative care and specialists within the field. To align with international standards for pediatric palliative care, underlining children’s right to equal care, national and regional initiatives are ongoing (15). Yet, access to palliative care is not solely a matter of organization. Individual knowledge and attitudes toward palliative care among healthcare professionals may influence communication regarding palliative care and the time of involvement. Many care providers still see palliative care as the very last option, and then the benefits may not be fully experienced by their patients. Thus, the aim of the current nationwide study was to investigate whether parents perceived that their child received palliative care and to what extent this contrasted parents’ perceptions of their child’s care and symptoms in the last month of life.

This was a nationwide population-based questionnaire study conducted with parents one to five years after their child’s death due to cancer, evaluating the end-of-life care.

In 2016, presumptive study participants were identified based on three Swedish national quality registries, which all have a very high coverage rate. Since the early 1980s, children diagnosed with cancer have been registered in the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry. This national register was used to identify children diagnosed with cancer before the age of 17 and during the years 2010-2015. Register data were linked to the Cause of Death Registry, established in 1961, which reports all children and young adults who had died from childhood cancer. Parents of the deceased children were identified through the Swedish Population Register at the Swedish Tax Agency, established in its current form in 1946. This identification was possible based on the child’s personal identification number.

The questionnaire was developed with items based on previous research (16) and sociodemographic data. A validation process was performed to ensure that the items were interpreted by the participants as intended by the researchers and to guarantee quality and relevance to the targeted population. The validation consisted of face- to-face interviews, conducted by the second author, with parents who had lost a child to cancer. The variables included in this study present data on parents’ awareness of the healthcare their child received, i.e., whether the child received palliative care or not, the parental view of aspects of healthcare, and the child’s symptoms during the last month of life. Previous publications based on the same national survey present the bereaved parents’ perceived social support, levels of prolonged grief, their psychological health, and the role of family communication (10, 17–20).

An introductory letter was sent to each identified registered parent (n=512) of the deceased child. The letter described the study purpose, design, and procedure and provided contact information for the research group. In the questionnaire, the research group added information regarding the definition of palliative care, namely, ‘Palliative care refers to symptom-relieving care provided without the direct intention to cure’. This was done to facilitate the parent’s accurate response to the study’s central question of whether their child had received palliative care. Approximately ten days later, all parents were contacted by telephone and asked if they would consent to participate. If there was a lack of information concerning the parents’ telephone numbers, letters were sent to their home addresses requesting them to contact the research group. Upon receiving positive consent, a questionnaire was sent by mail with a prepaid return envelope. No questionnaires were sent without consent. Around two weeks later, a reminder call was made to those who did not return the questionnaire.

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden, approved the study (No. 2015/2183-31/5)

Descriptive statistics are presented as frequencies, percentages, mean values, and standard deviations. Comparisons between responders and non-responders regarding sociodemographic data were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and chi-square analyses. The significance level was set to P < 0.05. All data were processed confidentially with code numbers. If a questionnaire contained more than 10% missing data, it was excluded from further analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows, version 22 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

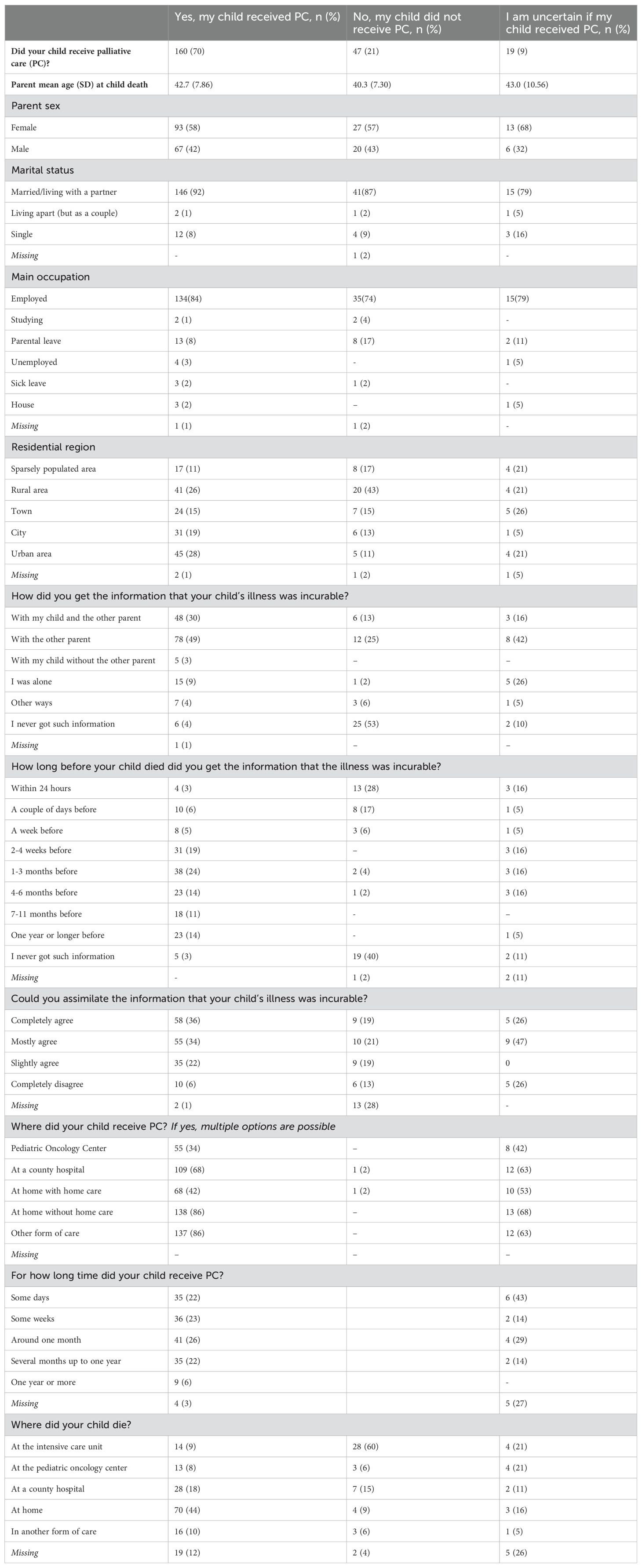

In total, 530 bereaved parents were eligible in the registries, of which 157 were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were as follows: they could not be reached by e-mail or by telephone (n=76), they declined participation (n=63) or they did not have sufficient knowledge of Swedish to answer the questionnaire (n=18). Questionnaires were sent to all bereaved parents (each parent separately in case of the same child) who consented to participate (n=373) and those who returned the questionnaires were included (n= 232). The study population was divided into three groups based on the following question: did your child receive palliative care? In total the question was answered by 226 bereaved parents and 155 children are represented by the study, i.e., 71 children are reported by two parents. The concordance between parents was high and equal to 93%. The majority of the participating parents were married or lived with a partner and were employed. The total study population of parents is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Parental demographic data and factors related to the parent’s perception regarding the provided information and the child’s care.

The study material was analyzed and is presented in relation to the parental answer, i.e., those who answered ‘yes’, those who answered ‘no’, and those who were uncertain if their child had received palliative care or not. In a dropout analysis, comparing those who responded to the survey and those who did not respond, there were no significant differences regarding the sociodemographic data presented in Table 1. However, the percentage of women was significantly higher among responders in comparison with non-responders (x2 = 8.83; P <0.05).

A majority of the parents (70%) reported that their child had received palliative care, 21% reported that their child did not receive palliative care and 9% were uncertain whether their child had received palliative care or not. In the group of parents who reported that their child received palliative care, 9% were informed that the disease was incurable within hours to days before the child’s death, while 3% were not informed at all. Corresponding numbers for parents who reported that their child did not receive palliative care were, 45% and 40%, respectively. The majority of parents who reported that their child received palliative care were informed about the child’s incurable disease with the other parent present (49%), and 30% with both the child and the other parent present. The majority (92%) of parents who answered ‘yes’ to the question that palliative care was received stated that they were able to assimilate the message that the disease was incurable, in comparison with 59% among those who answered ‘no’ and 73% of those who were uncertain. If palliative care was received, the most common place of care was at home without home care (86%) and the least common place was a pediatric oncology center (34%). The duration of palliative care varied from a few days, weeks, or several months up to a year, with roughly equal reported percentages for each time interval. A smaller proportion (6%) received palliative care for a year or longer. Among children receiving palliative care, most died at home (44%), in comparison with no reported palliative care where 9% died at home and 60% died at the intensive care unit (Table 1).

Parents of children who received palliative care perceived that they had influence in the child-care-related decisions (93%), received a quick response from healthcare professionals when assistance was needed (96%), and, based on the individual needs of the child, hospital (87%) or home (78%) care was provided. Similar professional support and guidance were experienced by parents in the groups ‘No, my child did not receive palliative care’ and ‘I am uncertain if my child received palliative care’. It was most common for families who lived in urban areas (28%) to report their child received palliative care, followed by rural areas (26%), cities (19%), towns (15%), and sparsely populated areas (11%). In the ‘No, my child did not receive palliative care’ group the majority lived in rural areas (43%). A significant proportion of caregivers in all three groups, ‘Yes, my child received palliative care’ (96%), ‘No, my child did not receive palliative care’ (74%) and those who were uncertain (89%), reported that the healthcare professionals were competent in caring for their child.

Based on the parental report, the parents played a significant role in the healthcare during the final month. The majority with a child receiving palliative care participated in their child’s care throughout the entire illness trajectory (n=134, 84%), and many felt that they were involved to the extent that they desired (n=116, 73%). More than half of the parents (62%) whose child received palliative care reported being able to have important conversations with their child. In the groups where no palliative care was received or uncertainty prevailed, the corresponding numbers were 40% and 33%, respectively. Around a third of the parents in the group whose child received palliative care (35%) claimed they talked with their child about death, while 19% of those whose child did not receive palliative care and 5% of those who were uncertain reported the same (Tables 1, 2).

According to the parents’ reports for children who received palliative care, the most common diagnosis was a brain tumor (45%), followed by children with leukemia (19%), sarcoma (10%), and other diagnoses (25%). In the two other groups of parental answers, leukemia was predominant. The malignant disease was identified as the leading cause of death in the group receiving palliative care (90%) and the group of uncertain parents (68%). Treatment-related complications represented the leading cause of death (49%) in the group who received no palliative care. Regardless of whether the child received palliative care or not, parents reported that during the last month of the child’s life, the child experienced multiple symptoms. In all three groups, the majority of parents reported that their child suffered to a large extent from physical weakness. In the group who received palliative care, the children suffered to a large extent from pain (64%) and poor appetite (61%) and were bothered by depression (32%), worry and anxiety (27%). When no palliative care was received the children were bothered to a large extent from poor appetite (54%), anxiety (43%), and respiratory distress (41%). Parents who were uncertain if their child received palliative care or not reported that the children to a large extent suffered from poor appetite (56%), pain (55%), weight loss (47%), and vomiting (41%) (Tables 3, 4).

In this nationwide study, the majority of parents of children deceased from cancer or treatment related complications reported that they were aware that their child received palliative care and felt informed about the incurable disease within weeks up to months before the child died. In this group, the most common diagnosis was a brain tumor with a disease-related death, and the care was often received at home. In the group of parents who reported that their child did not receive palliative care most parents claimed that they were informed about the incurable disease hours or days before the child died. The most common diagnosis in this group was leukemia, with a treatment-related death, and the care was often received at the intensive care unit.

Families living in urban or rural areas, compared to sparsely populated areas, reported to a greater extent that their child had received palliative care. A majority of parents whose child received palliative care stated that the healthcare professionals were competent in caring for their child. This confidence in healthcare professionals was also present among many parents in the other two groups. Not surprisingly, it was more likely to have talked about death with the child if palliative care was received, compared to those who did not receive palliative care, or if the parents expressed uncertainty about palliative care involvement. In all three groups, many children were affected by both physical and mental symptoms during the last month of their life.

In line with previous research in Sweden on children with cancer (21), a brain tumor was the most common diagnosis when parents reported that their child received palliative care. If parents did not perceive ongoing palliative care, leukemia was the predominant diagnosis. The results indicate differences in the timing of communication regarding prognosis between these two groups. Lack of timely communication is a well-known challenge in pediatrics (11). Parents who reported that their child received palliative care also reported that prognostic information was provided at an earlier stage of disease progression, compared to the group who did not receive palliative care. In the aforementioned group, one possible reason is that the child died from treatment-related complications, in line with the above-mentioned parental view, and therefore less likely to have had conversations about ‘disease incurability’. Another potential explanation is that the child’s disease progressed more rapidly, not leaving time for such conversations. Severe complications and rapid deterioration can lead to care in an intensive care unit, which may contribute to parents perceiving the treatment as curative. Previous research has shown that children with leukemia are more likely to die from complications related to treatment rather than to the disease itself, indicating high treatment intensity with an increased risk of complications (22).

Irrespective of the cancer diagnosis, prognosis is difficult to predict. A previous study has shown that pediatric oncologists are aware of the child’s potentially poor prognosis on average three months before the parents (23). Additionally, if both the parent and the physician recognize that there is no realistic chance of a cure, it is more likely that elements of palliative care will be included in the child’s care (23). According to the parents whose child received palliative care, the information about the incurable disease was given to most families with both parents present and sometimes also with the child present. This reflects an ‘open approach’ to disclosure of a prognosis and is based on the belief that children already know when they are seriously ill, and silence can create uncertainty and a lack of support for the dying child (24, 25). Research underscores the importance of balancing the complexity of these issues with considerations on a ‘case-by-case basis’, where aspects of the role of hope and culture are crucial (24). When the question was posed of whether the parent had talked to their child about death, the most common answer was ‘no’, regardless of whether the child had received palliative care. The literature confirms that it is an emotional and distressing situation and a major challenge for parents to convey difficult information and talk about death with their child (26). However, research has also shown that avoidance may increase the risk that parents regret their silence after the child’s death (6), and communication allows families to plan for their child’s final time and to help them cope with the severe circumstances (27). From the healthcare professionals’ perspective, studies highlight the fact that being a messenger of malignant disorders, communicating a poor or uncertain prognosis, especially to adolescents, is a challenging task (28, 29). When breaking bad news, physicians need to be open about the facts, be honest with their message, and at the same time convey hope (29, 30). Healthcare professionals state that providing care for the suffering and dying child adds complexity to all other challenges in end-of-life care (31, 32). Additionally, in the encounter between the family and the multidisciplinary healthcare providers, cultural issues, communication patterns and preferences need to be considered when disclosing bad news (24, 33). An early involvement of palliative care can help families and oncologists navigate the complexities and the ‘case-by case’ considerations (3).

In the present study, the child’s home was the most common place of death when receiving palliative care, and this has also been found to be the preferred location of care and death by parents and pediatric oncologists (34). Regardless of whether the child received palliative care, parents reported that they felt they had influence on decisions regarding their child’s care and they were confident that the child would get a place in the hospital and immediate help at home if needed. However, access to palliative care was not as good for families living in sparsely populated areas. A conceivable explanation is that the decentralized Swedish healthcare model plays a role and that regional differences become apparent when a child requires palliative care (13, 14). It should be noted that the study had a broad definition of palliative care and did not determine whether the care was provided by specialized or primary palliative care providers, nor did it identify the specific healthcare needs of each child. Despite differences in the level of care needed, most parents did not feel burdened by their child’s care, which aligns with a previous publication in the childhood cancer field (35). Practical support from healthcare professionals in managing daily tasks, along with parents’ perceptions that they are not obligated to take on more responsibilities than they can handle or wish to accept, is essential in this challenging situation, as noted by parents of children with serious illnesses (36). Irrespective of the type of care, the majority of parents reported that they considered the healthcare professionals competent. A contributing factor to their professional competence could be the specialized training in pediatric oncology that has been ongoing since the early 2000s in Sweden. These training programs for physicians and nurses include teaching and seminars on symptom control, communication, and palliative care, based on research and clinical experience. A scientific evaluation has been conducted regarding this training for nurses (37).

Parents reported that in the last month of the child’s life the child had physical weakness, pain and decreased appetite, and signs of depression and distress, irrespective of whether the child received palliative care. Regarding the symptoms affecting the children receiving palliative care, our findings do not differ from previous studies (38, 39). When children receive palliative care, it is part of the treatment to regularly assess various symptoms, particularly pain. This study did not explore symptom assessment; however, if the care is defined as palliative, it is likely that parents are particularly vigilant for signs that indicate a need for symptom relief. Regardless of how the form of care was defined, it was unsatisfactory to observe that not all children could have their symptoms alleviated. A recently published study shows that children’s symptoms need to be addressed more effectively (40). It is known that parents rate their child’s suffering higher than the child does themselves (41). Interestingly, when children with cancer report on their situation in their final days, their physical suffering is greater than their social and existential challenges (42).

The strength of this study is the national approach, including parental perceptions of their child’s incurable illness after treatment for several different cancer diagnoses. A limitation is the risk of recall bias regarding parental perceptions. Furthermore, we do not know if parents who reported that their child did not receive palliative care or those who were uncertain had wished to get this care for their child or received ‘non- articulated’ palliative care. The study has a response rate of less than 50%, and there is a potential risk for selection bias, as well as recruitment bias. However, given the subject area and the extensive study design with multiple research questions, the study findings are considered to reflect the target population.

In conclusion, understanding parental perceptions in pediatric palliative oncology care is vital for developing child-centered care. The study findings highlight the role of initiating palliative care early, the need for access to national equitable palliative care, and professional competence across the entire lifespan, regardless of diagnosis and place of residence.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (No. 2015/2183-31/5). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LP: Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – review & editing. UK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study was founded by the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation, Gålö Foundation, Marie Cederschiöld university college (formerly Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College) and Stockholm County Council.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Lam CG, Howard SC, Bouffet E, Pritchard-Jones K. Science and health for all children with cancer. Sci (New York NY). (2019) 363:1182–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw4892

2. Erdmann F, Frederiksen LE, Bonaventure A, Mader L, Hasle H, Robison LL, et al. Childhood cancer: Survival, treatment modalities, late effects and improvements over time. Cancer Epidemiol. (2021) 71:101733. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2020.101733

3. Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative Care: the World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2002) 24:91–6. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00440-2

4. Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, Wenk R, Ali Z, Bhatnaghar S, et al. Redefining palliative care-A new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2020) 60:754–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027

5. Benini F, Papadatou D, Bernadá M, Craig F, De Zen L, Downing J, et al. International standards for pediatric palliative care: from IMPaCCT to GO-PPaCS. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2022) 63:e529–e43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.12.031

6. Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, Henter JI, Steineck G. Talking about death with children who have severe Malignant disease. N Engl J Med. (2004) 351:1175–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040366

7. Bjork M, Wiebe T, Hallstrom I. Striving to survive: families' lived experiences when a child is diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. (2005) 22:265–75. doi: 10.1177/1043454205279303

8. Nelson M, Kelly D, McAndrew R, Smith P. 'Just gripping my heart and squeezing': Naming and explaining the emotional experience of receiving bad news in the paediatric oncology setting. Patient Educ counseling. (2017) 100:1751–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.028

9. Carlsson T, Kukkola L, Ljungman L, Hovén E, von Essen L. Psychological distress in parents of children treated for cancer: An explorative study. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0218860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218860

10. Bartholdson C, Kreicbergs U, Sveen J, Lövgren M, Pohlkamp L. Communication about diagnosis and prognosis-A population-based survey among bereaved parents in pediatric oncology. Psychooncology. (2022) 31:2149–58. doi: 10.1002/pon.v31.12

11. Brouwer MA, Maeckelberghe ELM, van der Heide A, Hein IM, Verhagen E. Breaking bad news: what parents would like you to know. Arch Dis childhood. (2021) 106:276–81. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-318398

12. Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. (2006) 24:5265–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5326

13. Nilsson S, Öhlén J, Nyblom S, Ozanne A, Stenmarker M, Larsdotter C. Place of death among children from 0 to 17 years of age: A population-based study from Sweden. Acta paediatrica (Oslo Norway: 1992). (2024) 113(9):2155–63. doi: 10.1111/apa.v113.9

14. Adolfsson K, Kreicbergs U, Bratthäll C, Holmberg E, Björk-Eriksson T, Stenmarker M. Referral of patients with cancer to palliative care: Attitudes, practices and work-related experiences among Swedish physicians. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2022) 31:e13680. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13680

15. Castor C, Ivéus K, Kreicbergs U. Pediatric palliative care in Sweden. Curr problems Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2023) 54(1):101455. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2023.101455

16. Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, Henter JI, Steineck G. Anxiety and depression in parents 4-9 years after the loss of a child owing to a Malignancy: a population-based follow-up. Psychol Med. (2004) 34:1431–41. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704002740

17. Pohlkamp L, Sveen J, Kreicbergs U, Lövgren M. Parents' views on what facilitated or complicated their grief after losing a child to cancer. Palliat Support Care. (2021) 19:524–9. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520001212

18. Pohlkamp L, Kreicbergs U, Sveen J. Factors during a child's illness are associated with levels of prolonged grief symptoms in bereaved mothers and fathers. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:137–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01493

19. Pohlkamp L, Kreicbergs U, Sveen J. Bereaved mothers' and fathers' prolonged grief and psychological health 1 to 5 years after loss-A nationwide study. Psychooncology. (2019) 28:1530–6. doi: 10.1002/pon.v28.7

20. Sveen J, Pohlkamp L, Kreicbergs U, Eisma MC. Rumination in bereaved parents: Psychometric evaluation of the Swedish version of the Utrecht Grief Rumination Scale (UGRS). PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0213152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213152

21. Jalmsell L, Forslund M, Hansson MG, Henter JI, Kreicbergs U, Frost BM. Transition to noncurative end-of-life care in paediatric oncology–a nationwide follow-up in Sweden. Acta paediatrica (Oslo Norway: 1992). (2013) 102:744–8. doi: 10.1111/apa.2013.102.issue-7

22. Surkan PJ, Dickman PW, Steineck G, Onelöv E, Kreicbergs U. Home care of a child dying of a Malignancy and parental awareness of a child's impending death. Palliative Med. (2006) 20:161–9. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1139oa

23. Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, Duncan J, Salem-Schatz S, Emanuel EJ, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. Jama. (2000) 284:2469–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2469

24. Sisk BA, Bluebond-Langner M, Wiener L, Mack J, Wolfe J. Prognostic disclosures to children: A historical perspective. Pediatrics. (2016) 138(3):e20161278. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1278

25. Jalmsell L, Lövgren M, Kreicbergs U, Henter JI, Frost BM. Children with cancer share their views: tell the truth but leave room for hope. Acta paediatrica (Oslo Norway: 1992). (2016) 105:1094–9. doi: 10.1111/apa.2016.105.issue-9

26. Kenny M, Duffy K, Hilliard C, O'Rourke M, Fortune G, Smith O, et al. 'It can be difficult to find the right words': Parents' needs when breaking news and communicating to children with cancer and their siblings. J psychosocial Oncol. (2021) 39:571–85. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2021.1890305

27. Snaman J, McCarthy S, Wiener L, Wolfe J. Pediatric palliative care in oncology. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:954–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02331

28. Udo C, Kreicbergs U, Axelsson B, Björk O, Lövgren M. Physicians working in oncology identified challenges and factors that facilitated communication with families when children could not be cured. Acta paediatrica (Oslo Norway: 1992). (2019) 108:2285–91. doi: 10.1111/apa.v108.12

29. Stenmarker M, Hallberg U, Palmérus K, Márky I. Being a messenger of life-threatening conditions: experiences of pediatric oncologists. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2010) 55:478–84. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22558

30. Harrison ME, Walling A. What do we know about giving bad news? A review. Clin pediatrics. (2010) 49:619–26. doi: 10.1177/0009922810361380

31. Gilmer MJ, Foster TL, Bell CJ, Mulder J, Carter BS. Parental perceptions of care of children at end of life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. (2013) 30:53–8. doi: 10.1177/1049909112440836

32. Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, Levin SB, Ellenbogen JM, Salem-Schatz S, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. (2000) 342:326–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506

33. Sobo EJ. Good communication in pediatric cancer care: a culturally-informed research agenda. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. (2004) 21:150–4. doi: 10.1177/1043454204264408

34. Kassam A, Skiadaresis J, Alexander S, Wolfe J. Parent and clinician preferences for location of end-of-life care: home, hospital or freestanding hospice? Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2014) 61:859–64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24872

35. Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, Björk O, Steineck G, Henter JI. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2005) 23:9162–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.557

36. Hjorth E, Kreicbergs U, Sejersen T, Lövgren M. Parents' advice to healthcare professionals working with children who have spinal muscular atrophy. Eur J paediatric neurology: EJPN: Off J Eur Paediatric Neurol Society. (2018) 22:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.10.008

37. Sandeberg MA, Olsson M, Ek T, Enskär K, Stenmarker M, Pergert P. Nurses' Perceptions of the impact of a national educational program in pediatric oncology nursing: A cross-sectional evaluation. J Pediatr hematology/oncology nursing. (2023) 40:178–87. doi: 10.1177/27527530221147879

38. Duncan J, Spengler E, Wolfe J. Providing pediatric palliative care: PACT in action. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. (2007) 32:279–87. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000287997.97931.5f

39. Jalmsell L, Kreicbergs U, Onelöv E, Steineck G, Henter JI. Symptoms affecting children with Malignancies during the last month of life: a nationwide follow-up. Pediatrics. (2006) 117:1314–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1479

40. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Howard RF, Slater R, Forgeron P, Palermo TM, et al. Delivering transformative action in paediatric pain: a Lancet Child & Adolescent Health Commission. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2021) 5:47–87. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30277-7

41. Mack JW, McFatrich M, Withycombe JS, Maurer SH, Jacobs SS, Lin L, et al. Agreement between child self-report and caregiver-proxy report for symptoms and functioning of children undergoing cancer treatment. JAMA pediatrics. (2020) 174:e202861. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2861

Keywords: pediatric oncology, palliative care, children, adolescent, cancer, palliative cancer care, parents, bereaved parents

Citation: Stenmarker M, Pohlkamp L, Sveen J and Kreicbergs U (2024) Bereaved parents’ perceptions of their cancer-ill child’s last month with or without palliative care - a nationwide study. Front. Oncol. 14:1387905. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1387905

Received: 18 February 2024; Accepted: 02 October 2024;

Published: 22 October 2024.

Edited by:

Ana Lacerda, Portuguese Institute of Oncology, PortugalReviewed by:

Richard Hain, Swansea University, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Stenmarker, Pohlkamp, Sveen and Kreicbergs. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Margaretha Stenmarker, bWFyZ2FyZXRoYS5zdGVubWFya2VyQHJqbC5zZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.