94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Oncol., 05 July 2024

Sec. Hematologic Malignancies

Volume 14 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1378647

This article is part of the Research TopicImmunobiology and Immunotherapeutics in Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Acute Myeloid LeukemiaView all 6 articles

Since its initial report in 2015, CD47 has garnered significant attention as an innate immune checkpoint, raising expectations to become the next “PD-1.” The optimistic early stages of clinical development spurred a flurry of licensing deals for CD47-targeted molecules and company mergers or acquisitions for related assets. However, a series of setbacks unfolded recently, starting with the July 2023 announcement of discontinuing the phase 3 ENHANCE study on Magrolimab plus Azacitidine for higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Subsequently, in August 2023, the termination of the ASPEN-02 program, assessing Evorpacept in combination with Azacitidine in MDS patients, was disclosed due to insufficient improvement compared to Azacitidine alone. These setbacks have cast doubt on the feasibility of targeting CD47 in the industry. In this review, we delve into the challenges of developing CD47-SIRPα-targeted drugs, analyze factors contributing to the mentioned setbacks, discuss future perspectives, and explore potential solutions for enhancing CD47-SIRPα-targeted drug development.

Immunotherapy has emerged as the primary treatment approach for various cancers, significantly altering survival outcomes for numerous cancer types. A rising number of patients now experience prolonged survival without active therapy, hinting at the potential for curing even stage IV diseases. However, the majority still succumbs to cancer, primarily due to the limitations of current immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) immunotherapies (1, 2). Recent findings underscore the pivotal role of CD47 in innate and adaptive immune escape, functioning as an immunological checkpoint (3). Conversely, signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) is an Ig-like protein highly expressed in macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, and neurons (4–6). The CD47/SIRPα signaling pathway through CD47 interacting with SIRPα on macrophages and dendritic cells, is an attractive target for cancer therapies in both solid tumors and hematological malignancies by regulating normal immune tolerance and autoimmunity (4, 7–10). Numerous studies of CD47/SIRPα blockades by targeting either CD47 or SIRPα have demonstrated potent anti-tumor action in preclinical models and clinical studies (4, 11, 12). However, numerous setbacks have been reported regarding this targeted therapy which not only raised doubts in the industry about CD47 targeted drug development plan but also various interpretations pointing to the druggability of CD47 targets. In this review, we highlight the recent progress and difficulties in CD47/SIRPα targeted drug development for cancer immunotherapy, look into future perspectives, and explore potential solutions to improve CD47/SIRPα targeted drug development.

“Don’t eat me” signaling pathways refer to mechanisms employed by cancer cells to evade detection and destruction by the immune system. Some key pathways have been identified and explored for their implications in immunotherapy, including the CD47-SIRPα axis, the Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1)/programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) pathway, the CD24/Siglec axis, and others. Each of these signaling pathways offers advantages in cancer immunotherapy, and a list of agents under development for these pathways is summarized in Table 1. In summary, targeting “don’t eat me” signaling pathways in cancer immunotherapy holds promise for enhancing anti-tumor immune responses. However, the efficacy of these approaches may vary among different cancer types and individuals, and further research is needed to optimize their therapeutic potential and minimize potential side effects.

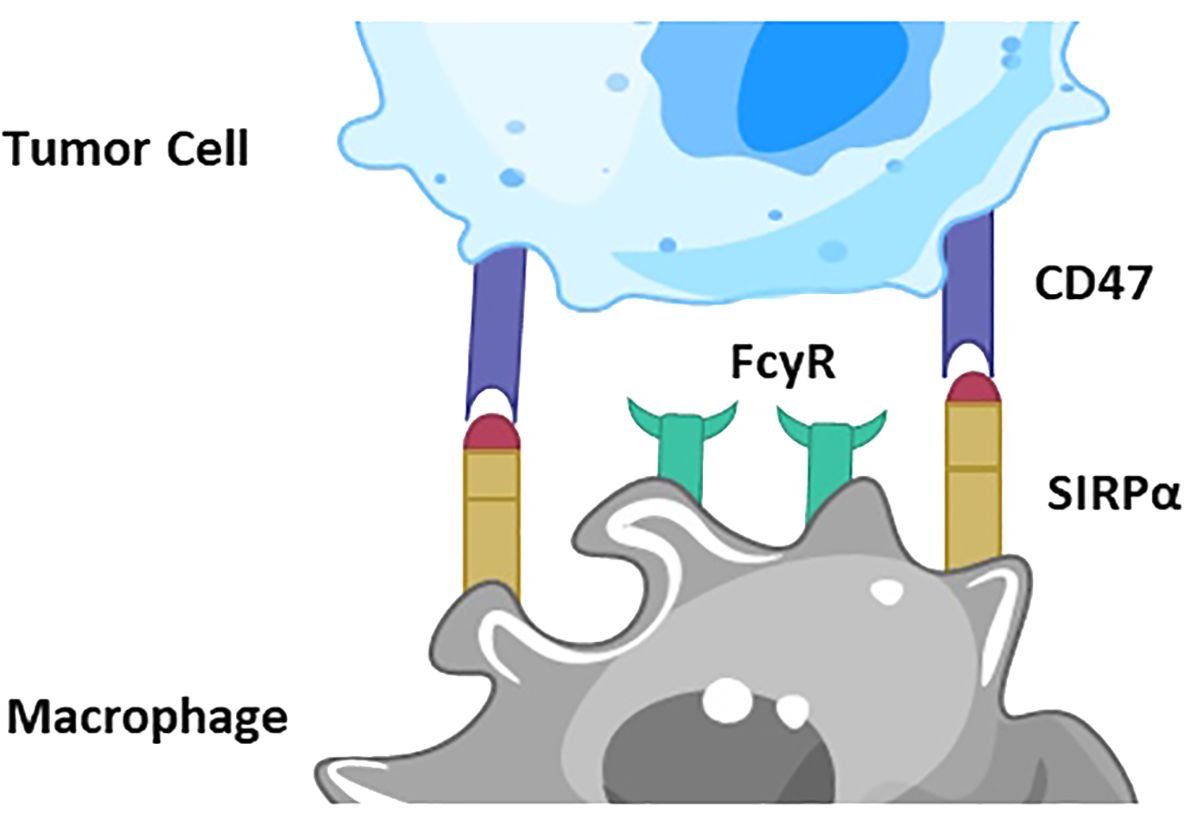

The CD47/SIRPα pathway plays a crucial role in regulating immune responses, particularly in the context of cancer immunotherapy. Briefly, CD47 is often overexpressed on the surface of cancer cells, acting as a “don’t eat me” signal. SIRPα is a receptor found on the surface of myeloid cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells. When CD47 binds to SIRPα, it sends an inhibitory signal to the myeloid cells. This interaction inhibits the phagocytic activity of the myeloid cells, preventing them from engulfing and destroying cancer cells, thus allowing the cancer cells to evade the immune system (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Depiction of CD47/SIRPα signaling pathway. CD47 is overexpressed on the surface of cancer cells, acting as a “don’t eat me” signal. SIRPα is a receptor on the surface of macrophages and dendritic cells. When CD47 binds to SIRPα, it sends an inhibitory signal to the myeloid cells. This interaction inhibits the phagocytic activity of the myeloid cells, preventing them from engulfing and destroying cancer cells, thus allowing the cancer cells to evade the immune system.

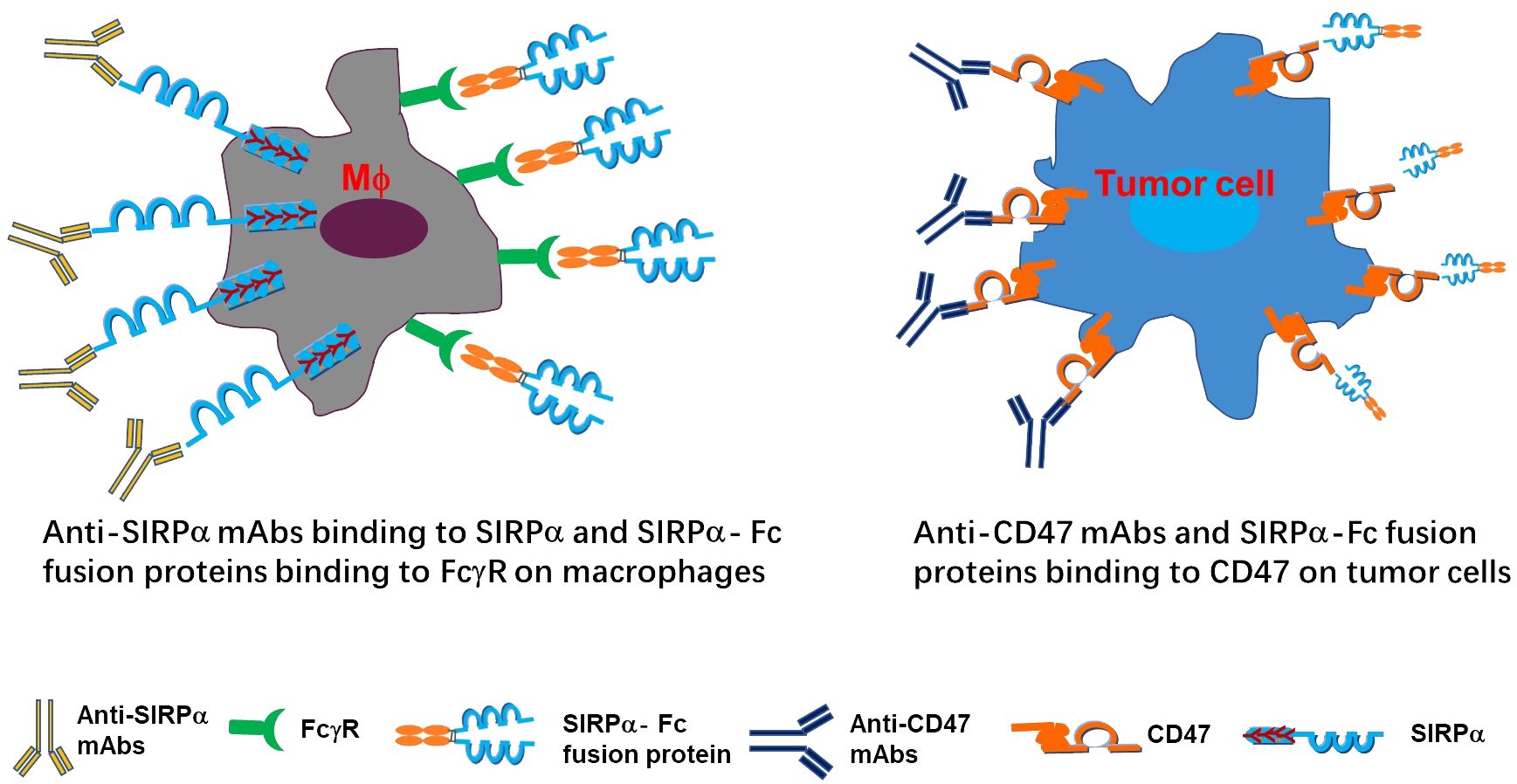

In immunotherapy, blocking the CD47/SIRPα interaction can enhance the immune system’s ability to target and eliminate cancer cells. Anti-CD47 antibodies or SIRPα-Fc fusion proteins can be used to block this pathway. By inhibiting the CD47/SIRPα interaction, the “don’t eat me” signal is turned off, allowing macrophages and other myeloid cells to recognize and phagocytose cancer cells more effectively. This mechanism makes the CD47/SIRPα pathway a promising target for cancer immunotherapies, aiming to boost the natural immune response against tumors.

As a potent “don’t eat me” anti-phagocytosis messaging signal, CD47 serves its functions by interacting with SIRPα on macrophages and dendritic cells. This signaling pathway is an attractive target for cancer therapies as it serves roles in both solid tumors and hematological malignancies in addition to its involvement in regulating normal immune tolerance and autoimmunity (4, 5, 13–15).

The structures of CD47 and signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) have been extensively reported in various publications (5–9, 16). CD47, also known as integrin-associated protein (IAP), is an Ig-like protein with widespread expression, including T cells, B cells, red blood cells, platelets, and hematopoietic stem cells. Conversely, SIRPα is an Ig-like protein highly expressed in macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, and neurons (Figure 2) (7, 10, 16). Recent advancements, such as the crystallization of CD47-targeting agent IMM01, provide a structural basis for potential clinical applications (16).

The CD47/SIRPα signaling pathway plays a crucial role in regulating myeloid cell-target cell signal transduction, as depicted in Figure 3 (7, 14). This axis has broad implications in the maintenance of erythrocytes, platelets, and hematopoietic stem cells. The expression of CD47 on cancer cells, akin to the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction inhibiting T cell activity, can impede myeloid cell-mediated clearance. Numerous studies have delved into the mechanisms of action of CD47/SIRPα blockades by targeting either CD47 or SIRPα. Various promising molecules blocking the CD47-SIRPα axis are in pre-clinical development.

Figure 3 Depiction of mechanism of actions targeting CD47/SIRPα axis. The anti-SIRPα mAbs bind to SIRPα and SIRPα-Fc fusion proteins bind to FcγR on macrophages (left panel), while anti-CD47 mAbs SIRPα-Fc fusion proteins bind to CD47 on tumor cells (right panel).

Monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins blocking CD47/SIRPα signaling have demonstrated potent anti-tumor action in preclinical models and clinical studies (7, 11, 12). Clinical trials have been initiated to investigate the effects of combining Azacitidine (Aza), an anti-metabolite chemotherapy drug, with CD47/SIRPα inhibition, such as the anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody (mAb) Magrolimab, in patients with hematologic malignancies. Although anemia was a frequent side effect of anti-CD47 therapy, risk-mitigation strategies such as using a low “priming” dose have significantly decreased this risk in clinical studies (17).

However, numerous setbacks have been encountered and reported regarding this targeted therapy which not only raised doubts in the industry about CD47 targeted drug development plan but also various interpretations pointing to the druggability of CD47 targets. With that, first, the phase II trial plan for CD47 mAb ZL-1201 was cancelled in August 2022 (18); then, in July 2022, the developer of ZL-1201 decided to deprioritize ZL-1201 for internal development but would pursue out-licensing opportunities; furthermore, in January 2023, another developer abandoned the clinical development of CD47 antibodies and dismissed all employees. Intense debates in the industry were further triggered by the termination of the phase III clinical study ENHANCE in which the combination of Magrolimab and Aza was tested against Aza alone as the first-line treatment for high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) (19). How can we approach the viability of CD47 targets with greater objectivity and reasoning? In this review, we highlight the difficulties in CD47/SIRPα targeted drug development for cancer immunotherapy, look into the future perspectives and explore potential solutions to improve CD47-SIRPα targeted drug development.

The landscape of clinical development for CD47/SIRPα targeted agents has witnessed a substantial surge in recent years, with numerous candidates entering clinical trials. The clinicaltrial.gov registry currently lists 38 ongoing trials targeting CD47 and 6 trials targeting SIRPα. This new generation of CD47 antagonist products falls into five categories (12, 20) (Table 2):

As of October 2023, there are no publicly published clinical trials on CD47 small-molecule inhibitors or ADC specifically for hematologic malignancies. Notably, SIRP/Fc fusion protein antibodies possess the capability to block CD47/SIRPα binding, thereby reducing the “don’t eat me” signal from CD47 and activating a pro-phagocytic signal via Fc receptors (7, 21). These antibodies exhibit low binding to red blood cells (RBCs) or blood platelets, distinguishing them from anti-CD47 monoclonal antibodies due to the absence of SIRPα expression on human blood cells (22).

Several anti-CD47 mAb products are actively undergoing clinical development in various forms, excluding acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Examples include AO-176 (CD47 mAb) (23), TG1801 (anti-CD19xCD47 bispecific), IMC-002 (CD47 mAb), STI-6643 (CD47 mAb), SL-172154 (SIRPα-Fc-CD40L), ZL-1201 (CD47 mAb), IMM01 (SIRPα-Fc fusion protein), PF-07257876 with IBI322 (anti-CD47 and PD-L1), and IMM-0306 (CD47xCD20 bispecific). Additionally, products targeting SIRPα, such as GS-0189, CC-95251, and BI765063/OSE-172, are also actively undergoing clinical development.

CD47 has been identified as a specific and overexpressed marker on ovarian cancer (OC) cells since 1986 (24), with factors such as Myc, NF-B, and HIF-1 regulating its expression (25–29). In the realm of CD47 targeted therapy for ovarian cancer, various approaches have been explored, ranging from monotherapy inhibiting the CD47-SIRPα axis to combinations with tumor-targeting antibodies and bispecific antibodies disrupting the CD47-SIRPα axis (30). As of August 19, 2023, four CD47 targeted treatment trials for ovarian cancer were registered in the US National Clinical Trials Registry (NCT), including BI 765063 (an antibody antagonist of SIRPα formerly known as OSE-172, NCT04653142), which exhibited potential effectiveness and good tolerance in its preliminary report without dose-limiting toxicities in patients with ovarian cancer (Table 3) (31). Notably, BI 765063 is also undergoing clinical trials for other cancer types (NCT03990233, NCT05249426, NCT05446129, and NCT05068102).

Monotherapy involving the blockade of the CD47-SIRPα axis has shown promising outcomes in ovarian cancer, with the combination of pro-phagocytic CD47-SIRPα axis monoclonal antibodies and Fc-dependent effects of tumor-targeting antibodies, such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), demonstrating synergistic efficacy (10, 24). In a phase Ib trial involving 18 platinum-resistant or refractory OC patients, the combination of Hu5F9-G4 with Avelumab (PD-L1) showcased a 56% stable disease (SD) rate (32), prompting further evaluation in a phase II trial (NCT03558139). Another promising candidate, PF-07257876, a dual checkpoint inhibitory bispecific antibody simultaneously blocking CD47 and PD-L1, is currently undergoing a phase I dose escalation and expansion trial in OC patients (NCT04881045).

In the realm of breast cancer treatments, a preclinical study suggests that overcoming resistance to trastuzumab in HER2/Neu+ breast cancer can be achieved by combining CD47 blockade with trastuzumab (33). The combination of CD47 mAb with trastuzumab not only significantly reduced the growth of HER2+ breast tumors resistant to ADCC but also enhanced the efficacy of trastuzumab, leading to complete tumor regression (33, 34).

In the case of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), cells that had previously undergone chemotherapy showed increased CD47 expression (35, 36). Preclinical studies have demonstrated that anti-CD47 mAb decreases breast cancer cell proliferation and induces the death of breast cancer cells in vitro (37). The synergistic effect of anthracyclines and CD47 mAb has been observed to enhance tumor ablation in vivo (38, 39). In other preclinical studies, the combination of CD47 mAb and cabazitaxel exhibited a significant anti-cancer effect in TNBC (40). Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) utilizing mertansine and anti-CD47 mAb for TNBC treatment demonstrated potent tumor suppressive activity without systemic immune toxicity (20). Furthermore, in vivo studies have shown that inhibiting CD47 successfully reverses radiation resistance and improves phagocytosis (41). Currently, five products targeting the CD47-SIRPα signaling pathway are undergoing various clinical trials for breast cancer treatment (Table 4). These trials reflect the growing interest and exploration of CD47-SIRPα targeted immunotherapy in the context of breast cancer. In addition, CD47 inhibitors are also under evaluation on multiple other malignancies, such as head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

In the realm of targeting CD47 immunotherapy for lymphomas, there are currently 15 CD47 antagonists undergoing clinical studies for treatment (Table 5). Some CD47 monoclonal antibodies, including CC-90002, Hu5F9-G4 (Magrolimab), TJ011133 (Lemzoparlimab) (33). and AK117 (Ligufalimab), have recently initiated clinical trials (12).

Magrolimab (Hu5F9-G4), a humanized-IgG4 antibody, has shown promising activity in both aggressive and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) patients in a phase Ib trial (NCT02953509) (17, 42). The combination of Magrolimab with rituximab demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 50% and a complete response rate (CR) of 36% in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) lymphoma. Notably, patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) had an ORR of 40% and a CR of 33%, while patients with follicular lymphoma (FL) exhibited an ORR of 71% and a CR of 43% (15, 17, 43). Additionally, Bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) simultaneously blocking the CD47-SIRPα axis and binding to the tumor-specific antigen (CD20) have shown promising efficacy with less blood cell destruction in a human NHL-engrafted mouse model (44).

CC-90002, a CD47 monoclonal antibody, in combination with rituximab (CD20 monoclonal antibody), has been studied in a phase I trial for patients with heavily pretreated R/R NHL, showing good tolerance and modest clinical activity (45). TJ011133 (Lemzoparlimab) has been examined in a phase Ib clinical trial (NCT03934814) for R/R patients with CD20-positive NHL, demonstrating therapeutic efficacy, good tolerance, and controllable side effects, with an ORR of 57% (46). These ongoing clinical trials underscore the growing interest and potential of CD47-SIRPα targeted immunotherapy in the treatment of lymphomas, presenting new avenues for improving patient outcomes.

AK117, currently in a phase I clinical trial, has demonstrated good tolerance with no hematological adverse events (AEs). Being tested for various hematologic malignancies, AK117 is undergoing clinical trials either as a monotherapy or in combination with other agents, such as rituximab (47).

IMM0306, a fusion protein of CD20 monoclonal antibody with the CD47 binding domain of SIRPα, demonstrated excellent cancer-killing efficacy by activating both macrophages and NK cells (48). Clinical trials (NCT05771883 and NCT05805943) are underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of IMM0306 in combination with lenalidomide and as a monotherapy in patients with R/R CD20-positive B-cell NHL, respectively. Clinical trials (NCT05771883 and NCT05805943) are underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of IMM0306 in combination with lenalidomide and as a monotherapy in patients with R/R CD20-positive B-cell NHL, respectively (1). IMM0306 has displayed superior tumor cell binding preference and more effective anti-lymphoma activity compared to CD47 monoclonal antibody alone in both in vivo and in vitro studies (44, 49). IMM0306 activates macrophages and NK cells by blocking the connection between CD47 and SIRPα and engaging FcγR, resulting in excellent cancer-killing effectiveness without binding activity on human RBCs and no hemolytic side effects. When compared to rituximab, IMM0306 shown stronger ADCC activity and reduced CDC activity in several hematologic malignancy cells, presumably, because the IMM0306’s Fc portion is an IgG1 molecule. In combination with lenalidomide, IMM0306 has shown greater efficacy than any single treatment or rituximab in combination with lenalidomide in an orthotopic lymphoma model (9). Phase I clinical trials for IMM0306 have been initiated in the United States and China for patients with R/R CD20-positive B-cell NHL (NCT05771883, NCT05805943, and CTR20192612).

The anti-CD47/CD19 BsAb TG-1801 (NI-1701) has demonstrated strong potential in preclinical studies to elicit ADCP and ADCC in malignant B-cell lines and primary tumor B-cells from patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and several subtypes of NHL (7, 50, 51). Two phase I trials (NCT03804996 and NCT04806035) are currently evaluating TG-1801’s safety and effectiveness in treating patients with B-cell lymphoma and CLL.

Four SIRPα/Fc fusion protein antibodies, TTI-621, TTI-622, ALX418, and IMM01, are undergoing clinical testing. These fusion proteins, created by combining the CD47-binding domain of human SIRPα with either the human IgG1 or IgG4 Fc region, aim to enhance phagocytosis and anti-cancer activity of macrophages by blocking CD47-SIRPα contact between malignant cells and macrophages through Fc receptor engagement (9, 21, 52–55). In a phase I study of TTI-621 in patients with R/R lymphoma, favorable safety and efficacy profiles were observed, with 14 out of 71 NHL patients showing responses and a 20% ORR (21, 56).

TTI-622 is currently undergoing a multicenter phase I dose-escalation and expansion trial (NCT03530683). According to preliminary findings, out of the nine patients, two achieved a CR (one in DLBCL and one in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma—mycosis fungoides), and seven achieved a partial response (PR) (two each in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, DLBCL, and FL) (53).

ALX148, also known as Evorpacept, is a CD47-blocking molecule with a modified SIRP D1 domain connecting to an inactive human IgG1 Fc. In a phase I clinical trial (NCT03013218) involving 33 patients receiving various doses of ALX148 along with rituximab, it demonstrated promising anti-tumor efficacy and low adverse events (57).

IMM01, a recombinant human SIRP-IgG1 fusion protein, has shown potent dual-functional anti-tumor action by inducing phagocytosis in preclinical experiments. It also exhibited the ability to weakly bind human erythrocytes without significant hemolysis (9, 16). According to preliminary findings from a phase I study (CTR1900024904) involving 14 patients with R/R lymphoma, the ORR was 14.3% (one CR and one PR), with two patients at validated SD (58). Additionally, preliminary data from a phase II clinical trial with IMM01 demonstrated a robust anti-tumor effectiveness with a well-tolerated safety profile in classical Hodgkin lymphoma patients who had failed prior anti-PD-1 therapy (59).

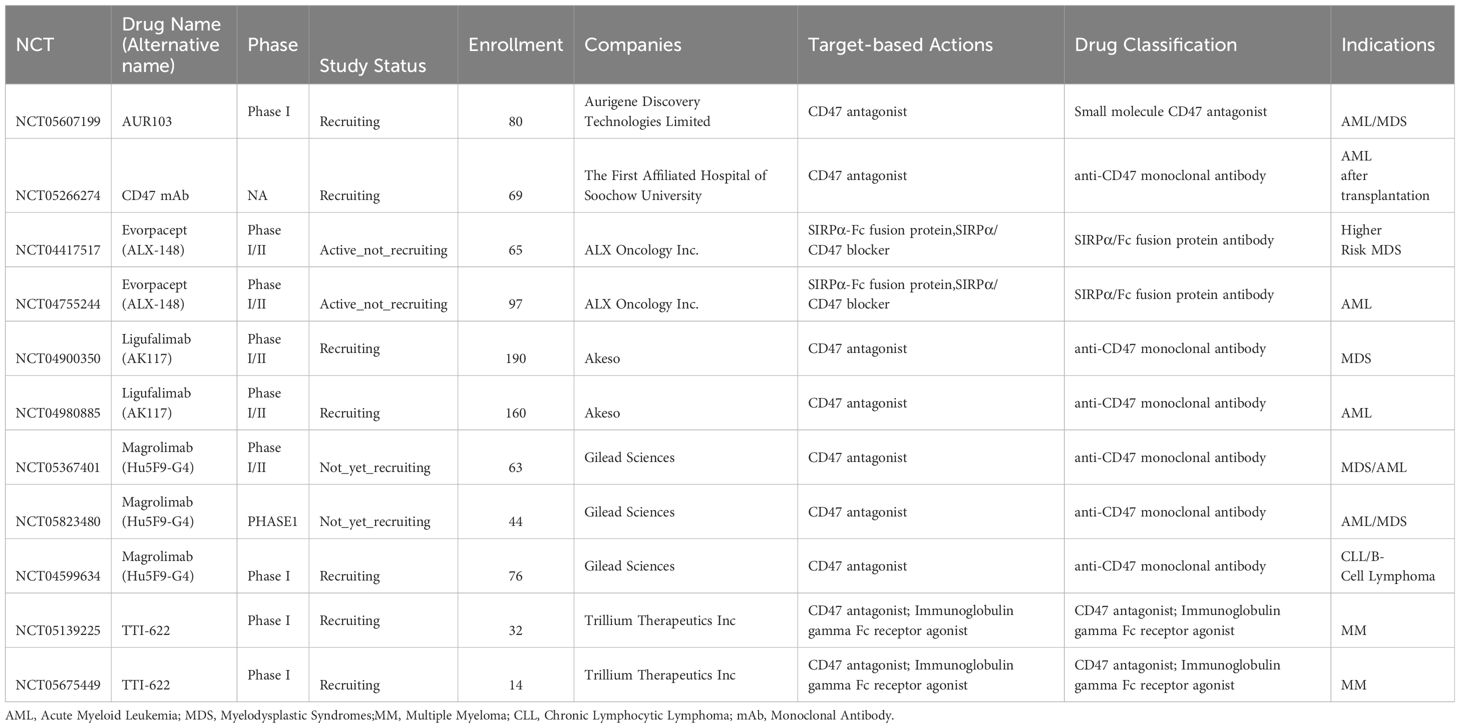

CD47 is highly expressed on AML cells, including leukemic stem cells, in 25–30% of AML patients, serving as an independent prognostic factor for poor overall survival (60). Currently, 11 CD47 antagonists are undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of hematological malignancies (Table 6), with published clinical research data available for some of these CD47 antagonists (7, 9, 12, 17, 43, 61).

Table 6 CD47 agents currently entering clinical trials for treatment of hematological malignancies except lymphoma.

Magrolimab (5F9), a humanized IgG4 anti-CD47 antibody, demonstrated leukemic eradication and long-term survival in a preclinical xenografted mouse model (62). In a phase I monotherapy trial for patients with R/R AML, Magrolimab did not achieve CR (63). However, promising ORR were observed in combination with Aza for untreated AML in phase Ib trials (64). The ORR was 65% among 34 evaluable patients, with a higher CR rate in TP53-mutated AML patients. Subsequent trials showed 53% and 56% CR or incomplete count recovery (CRi) (63). Subsequent trials showed 53% and 56% CR or CRi rates in AML/MDS patients, with higher rates in those with TP53 mutations (63). In another study with 15 patients enrolled, the CR/CRi rate in the newly diagnosed AML patients was 100% (15/15) with a CR rate of 87% (13/15). Patients with TP53 mutations achieved a CR/CRi of 100% (7/7) and a CR of 86% (6/7) (65). In R/R prior venetoclax (VEN) failure AML, the CR/CRi rate was 27% (3/13) with a median overall survival (OS) of 3.1 months (range 0.9–6.5) (66). Magrolimab has progressed to phase III trials.

CD47 mAb IBI-188 (Letaplimab) is undergoing clinical trials for newly diagnosed intermediate and high-risk MDS and AML. Phase III trials in China for hematologic disorders and phase I trials with rituximab in advanced lymphoma, Aza in AML, and Aza in newly diagnosed higher-risk MDS are also ongoing (NCT03717103, NCT04485052 and NCT04485065).

CD47 mAb TJ011133 (TJC4, Lemzoparlimab) is being tested in a phase I trial for R/R AML or MDS, showing promising efficacy and manageable adverse events (NCT04202003). Four of five patients had treatment-related AEs with one AE of grade 3 while the rest at grades 1–2. One R/R AML patient attained morphologic leukemia-free status following two cycles of therapy (67). A phase III trial in primary higher-risk MDS is planned.

CC-90002, a newer CD47 antagonist, demonstrated potential efficacy in preclinical models but a phase I study for R/R AML and MDS was terminated due to lack of monotherapy activity and evidence of anti-drug antibodies (68–70). At present, no clinical trial of CC-90002 was found in hematological malignancies.

In a phase Ib trial, anti-CD47 mAb AK117 in combination with Aza demonstrated favorable tolerance and a 54.2% CR rate in newly diagnosed high-risk MDS patients (71).

Targeting the CD47-SIRPα pathway with recombinant fusion proteins (e.g., TTI-662)) and bispecific antibodies has entered clinical trials (72, 73). Preliminary data for the SIRPα-Fc fusion protein IMM01 in combination with Aza showed promising efficacy and tolerability in patients with treatment-naive chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) and higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (HR-MDS). Among the 16 efficacy-evaluable CMML patients with treatment duration ≥3 months, the ORR was 87.5%, and the CR rate reached 25.0% (74). In another study IMM01 (without low-dose priming) in combination with Aza showcased promising efficacy in patients with treatment-naive HR-MDS. Among the 22 efficacy-evaluable patients with treatment duration ≥4 months, the ORR was 81.8%, and the CR rate was 36.4% (75). Combination therapy with AK117 and Aza displayed a manageable safety profile and significant efficacy as a first-line treatment in AML patients unable to undergo intensive chemotherapy, with a 55% complete clinical response rate (76).

Multiple myeloma (MM) has been considered to be incurable despite recent therapeutic advances. Preclinical studies targeting CD47/SIRPα signaling pathway related immunotherapy has been explored in MM patients. Study demonstrated that bortezomib-resistant multiple myeloma patient-derived xenograft is sensitive to anti-CD47 therapy (77). Blocking of CD47 using an anti-CD47 antibody induced immediate activation of macrophages showed phagocytosis and killing of MM cells in the 3D-tissue engineered bone marrow model (78). The tumor microenvironment plays a critical role in disease progression in MM. Single-cell atlas of the immune microenvironment reveals macrophage reprogramming and the potential dual macrophage-targeted strategy in MM by combining an anti-CD47 antibody and MIF (macrophage inhibitory factor) inhibition. The dual macrophage-targeted approach blocking both CD47 and MIF showed potent antitumor effects (79). Delivery of CD47-SIRPα checkpoint blocker by BCMA-directed universal chimeric antigen receptor T (UCAR-T) cells enhances antitumor efficacy in multiple myeloma in the xenograft model. Two possible mechanisms include the UCAR-T cells directly killed tumor cells and enhanced the phagocytosis of macrophages by secreting anti-CD47 nanobody hu404-hfc fusion (80).

A fully human CD38xCD47 bispecific antibody, ISB 1442, consists of two anti-CD38 arms targeting two distinct epitopes that preferentially drive binding to tumor cells and enable avidity induced blocking of proximal CD47 receptors on the same cell while preventing on-target off-tumor binding on healthy cells. Combined strategies for effective cancer immunotherapy with IBI188 have been considered as a potential treatment for MM patients (81). ISB 1442 is currently in a phase I clinical trial in R/R MM (NCT05427812) (82). In addition, a phase II multi-arm study of Magrolimab combinations in patients with R/R MM is under study (NCT04892446) (83). Another trial (NCT05139225) with the SIRPα/Fc fusion protein TTI-622 in combination with daratumumab hyaluronidase-fihj in patients with MM is ongoing. More extensive studies are needed regarding the efficacy of these agents targeting CD47/SIRPα signaling pathway in patients with MM.

Despite the promising outcomes observed in preclinical and clinical trials, the journey of developing CD47 mAbs has been riddled with challenges, notably centered around therapeutic efficacy and safety concerns. The persistent obstacles of toxicities pose ongoing challenges, with hematotoxicity, particularly anemia, and off-target myelosuppression emerging as predominant AEs associated with CD47 inhibitors. The widespread expression of CD47 on normal cells, particularly on red blood cells (RBCs) and platelets, creates a scenario where CD47 antagonists can directly target these cells or induce their recognition by natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages through Fc-mediated ADCC or complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) (84). The resultant hemolysis, a known consequence of CD47 mAbs, has led to the implementation of RBC pruning strategies in AML trials (2). This innovative approach involves a Magrolimab priming dose-escalation regimen, wherein the dosage is gradually increased from 1 to 30 mg/kg administered intravenously weekly (85, 86). This is followed by a maintenance dose of 30 mg/kg every 2 weeks in subsequent cycles beyond the third, aiming to alleviate the on-target anemia effects (63). The meticulous orchestration of dosing regimens reflects the dedication to mitigating adverse impacts, emphasizing the ongoing commitment to refining the therapeutic profile of CD47 antagonists in the pursuit of safer and more effective treatments. Several CD47-targeted clinical trials have been terminated, due to the safety concerns regarding the RBC binding activity and other adverse effects (87) (Table 7). Especially, the development of Magrolimab was interrupted in patients with AML and MDS and the related trials were discontinued for futility, non-efficacy, and increased mortality related to infections and respiratory problems. Overall, challenges remain to be overcome for the CD47/SIRPα related checkpoint inhibition immunotherapy, especially in AML (88).

Beyond the immunological challenges associated with CD47 antagonists, the inhibition of SIRPα introduces potential concerns related to the nervous system (86). Given the elevated expression of SIRPα on cells within both the central and peripheral nervous systems, the impact of SIRP inhibition on neural tissues becomes a notable consideration. The inherent structural similarities among members of the SIRP family further raise the prospect of improper interactions when CD47, present on cells, reacts with other SIRP members (81).

The conserved sequences within the SIRP family highlight the need for a nuanced approach to avoid unintended consequences. Recent insights into human T cell activation and proliferation underscore the favorable regulatory role played by CD47 when binding to SIRPα, particularly in comparison to the beta or gamma variants. The potential inhibition of T-cell activity, a critical component of the immune response, underlines the importance of thorough investigation in future research. To address these challenges and enhance therapy effectiveness while minimizing toxicity, the development of innovative strategies such as SIRPα/Fc fusion protein antibodies and CD47-targeted BsAbs is being explored (89, 90).

These novel approaches aim to strike a balance between therapeutic impact and safety, offering promising avenues to navigate the complexities associated with CD47-SIRPα axis modulation (62). However, the administration of higher dosages or frequent treatments carries the risk of inflicting damage on healthy cells, leading to potential unfavorable treatment-related consequences. Moreover, the effective dosage of CD47 antagonists may require adjustments in scenarios where tumor cells express both SIRPα and thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), both of which disrupt the CD47-SIRPα interaction. To adequately activate macrophages, it becomes imperative to engage Fc receptors. Consequently, the choice of the appropriate human Immunoglobulin G (IgG) subtype plays a pivotal role (48, 55). While human IgG1 stimulates macrophages more effectively, it also heightens the risk of immune cells targeting RBCs. In response to this challenge, most companies opt for the development of human IgG4-type antibodies (55, 91). This strategic selection aims to strike a balance between the desired immune activation and the potential off-target effects, emphasizing the nuanced considerations involved in CD47-targeted therapies.

The safety concerns and incidents during the development of CD47-targeted drugs highlight the challenges in bringing these therapies to clinical applications. Instances like the premature termination of the phase 1 clinical trial of Ti061 (CD47 mAb) in 2017 due to unexpected deaths (92)and the failure of CD47 mAb CC90002 in a phase I clinical trial (NCT02641002) because of severe hemagglutination emphasize the importance of safety considerations (69, 70).

The favorable phase 1b results of Magrolimab in combination with Aza in patients with MDS and AML sparked enthusiasm for CD47-targeted drug development. The use of a low priming dose to remove aged erythrocytes and induce compensatory hematopoiesis (17, 63), along with the subsequent maintenance dose, led to Magrolimab receiving a Breakthrough Therapy designation for the treatment of newly diagnosed MDS in 2020. However, a partial clinical hold was placed on studies evaluating the combination of 5F9 plus Aza in January 2022 due to an apparent imbalance in suspected unexpected severe adverse reactions (93). Although concerns were initially linked to the hematotoxicity of Magrolimab or the additive toxicity of Aza, the partial clinical hold was removed in April 2022 after a comprehensive safety data review (94). In July 2023, the phase 3 ENHANCE study of Magrolimab in HR-MDS was discontinued (19). In August 2023, a partial clinical hold was placed on the recruitment of new patients in U.S. studies evaluating Magrolimab to treat AML (95).

There are several potential reasons for the inadequate efficacy of Magrolimab in recent clinical trial failures for cancer immunotherapy. These include tumor microenvironment complexity, heterogeneity of cancer cells, adaptive resistance, insufficient drug delivery and penetration, myeloid cell dysfunction, immune system modulation, off-target effects and toxicity, and clinical trial design. Further research and analysis of clinical trial data are necessary to pinpoint the exact reasons for the inadequate efficacy observed in these trials. Understanding these factors will help refine future therapeutic strategies and improve the design of subsequent trials.

Despite these challenges, CD47-targeted drugs continue to be a focus of tumor immunotherapy. Various strategies, such as anti-SIRPα mAbs, SIRPα-fusion proteins, BsAbs, dual ICIs, dual CAR-T cells, and OC-CD47, are being explored to overcome current limitations. Additionally, TAX2, the first antagonist of the TSP-1/CD47 axis, has been engineered. TAX2 selectively targets tumor-overexpressed TSP-1, inhibiting tumor angiogenesis and activating the anti-tumor immune system without harming blood cells (96).

In summary, the development of CD47-targeted drugs involves addressing safety concerns, overcoming limitations, and exploring innovative strategies to enhance tumor immunotherapy. Ongoing research and clinical trials aim to optimize the therapeutic potential of CD47-targeted therapies for various hematological malignancies and solid tumors.

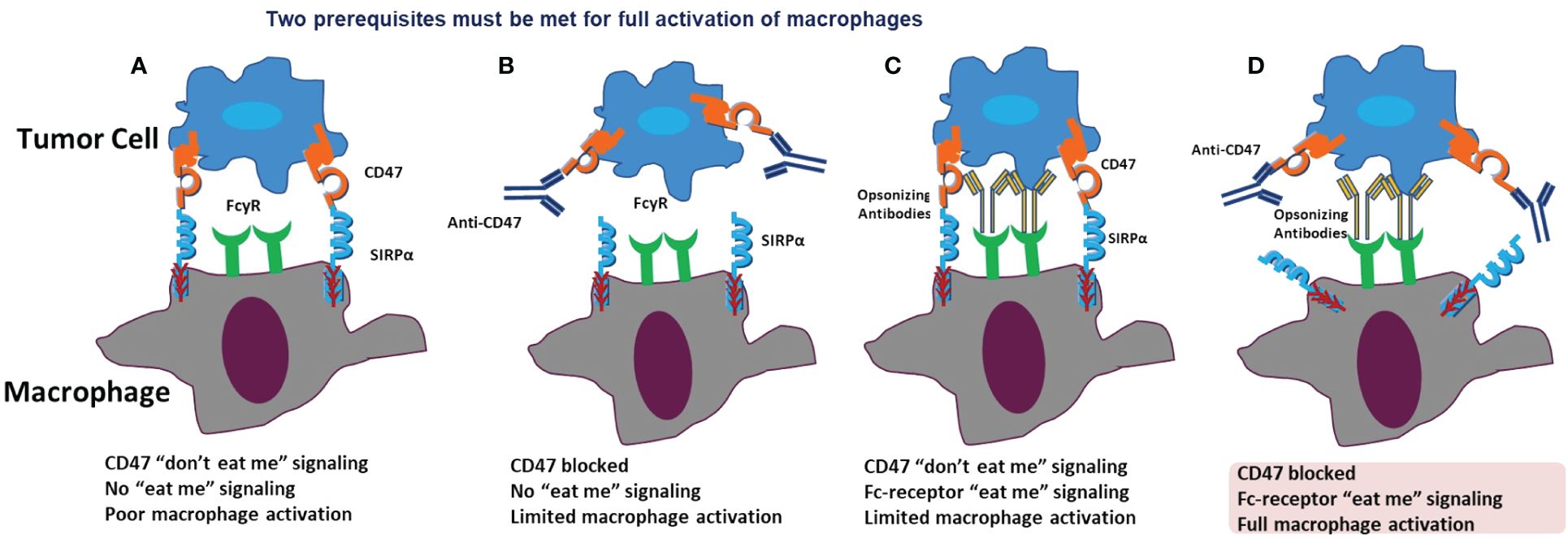

In our exploration of drug actions targeting the CD47/SIRPα signaling pathway for tumor immunotherapy, we propose a hypothesis on macrophage activation. Full macrophage activation for effective tumor cell elimination hinges on two prerequisites: blocking the CD47 ‘don’t eat me’ signal and activating the Fc-receptor ‘eat-me’ signal. In the typical tumor cell environment, where tumor cells express CD47 and macrophages express SIRPα, there is an absence of the ‘eat-me’ signal. Limited macrophage activation occurs when either the CD47 ‘don’t eat me’ signal is blocked or the Fc-receptor ‘eat-me’ signal is activated. Only when both signals are manipulated—blocking CD47 and activating the Fc-receptor—do macrophages achieve full activation for effective tumor killing (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Prerequisites for macropage activation. In a normal situation, CD47 binds to SIRPα, acting as the “don’t eat me” signal, and no “eat me” signal is present. Therefore, there is no or poor macrophage activation (A). When only CD47 is blocked, the “don’t eat me” signal is inhibited. However, no “eat me” signal is activated, resulting in only limited macrophage activation (B). When the CD47 “don’t eat me” signal is present, and only the Fc-receptor “eat me” signal is activated, there is still only limited macrophage activation (C). When both CD47 is blocked and the Fc-receptor “eat me” signal is activated, full macrophage activation occurs (D).

Despite the discontinuation of the phase 3 ENHANCE study of Magrolimab in MDS, there is still a glimmer of hope as several other key clinical trials, including AML, are progressing on track. CD47 is highly expressed on tumor cells and relatively low in peripheral blood cells. The receptor occupancy (RO) of CD47-targeting drugs (antibodies or SIRPα Fc recombinant protein) is predominantly detected by peripheral blood cells. The RO value does not directly correspond to the therapeutic effect of the drug but rather has a direct correlation with the “antigen sink” effect. Therefore, using peripheral blood to detect the RO of CD47-targeting drugs in clinical practice lacks therapeutic reference value.

Targeting the CD47/SIRPα signaling pathway continues to hold significant promise in solid tumor immunotherapy. When the selected mAb exhibits a moderate affinity with CD47 (in the nanomolar range) and does not excessively bind to red blood cells, it remains promising to determine an appropriate dosage for combination therapy with other drugs, such as IgG1 monoclonal antibodies like rituximab and Herceptin.

In contrast to antibodies, recombinant proteins targeting CD47, like IMM01, present a greater opportunity. IMM01, a recombinant human SIRPα IgG1 fusion protein, comprises SIRPα domain 1 and humanized IgG1 Fc segments. IMM01 demonstrates multifunctionality by blocking the CD47-SIRPα signaling pathway to avoid the “don’t eat me” signal. Additionally, it activates the “eat me” signal through Fc binding to the Fcγ receptors on the macrophage membrane, leading to the activation of macrophages. This activation, in turn, facilitates the presentation of tumor antigens to T cells, inducing tumor-specific T cell anti-tumor immunity (9, 97).

IMM01 presents several potential advantages over other agents in the realm of CD47-targeted immunotherapy. Firstly, it avoids the “antigen sink” risk, as it does not bind to red blood cells, and its target affinity is moderate. In comparison to Magrolimab, which exhibits a binding affinity range of 2–14.3 pM, IMM01 has a maximum binding affinity of 3 nM. The average receptor occupancy of peripheral PBMC cells is less than 20%, resulting in no significant ‘antigen sink’ effect. Secondly, owing to the unique molecular design of IgG1-Fc, the clinical recommended phase II dose (RP2D) of IMM01 is considerably lower than that of Magrolimab (IMM01: 2mg/kg; Magrolimab: 1mg/kg+30mg/kg), demonstrating good clinical safety and efficacy. Preliminary clinical trial results indicate a significant reduction in the incidence of grade 3 anemia with no cases of hemolytic anemia. Notably, IMM01 does not require priming dose administration. The stimulation of macrophages via IMM01 provides a scientific rationale for combining it with PD-1 monoclonal antibodies. This combination leads to the production of certain chemokines (CXCL9/CXCL10), driving T lymphocytes into tumor tissue and transforming ‘cold tumors’ into ‘hot tumors.’ Simultaneously, macrophages present tumor antigens processed by phagocytosis to T cells. Based on preliminary clinical trial data in patients with classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma relapsed after PD-1 antibody treatment, a synergistic effect with IMM01 has been observed, demonstrating an improved overall response rate from 17% to over 60% (unpublished data).

Given the current available information, predicting the outcome of Magrolimab+Aza therapy in AML appears challenging. The development of anti-CD47 antibody drugs faces inevitable safety issues, particularly when the binding ability of the antibody to red blood cells is too strong, causing an “antigen sink” effect where antibodies are predominantly taken by normal cells, leaving a minimal effective amount for tumor tissue. Higher doses may result in increased blood toxicity, including anemia and neutropenia. The root of the problem is believed to lie in the antibody itself, as IgG4 antibodies for the Fc portion do not encounter such issues.

In the foreseeable future, CD47/SIRPα immunotherapy holds the potential to stand as a promising option, on par with PD-1/PD-L1. Enhancing the efficacy and safety of CD47 antagonists requires strategic development, and we propose several potential tactics for future exploration, including prime and maintenance dosing strategy, structure modification, dual blockade strategies (48, 98), BsAbs and fusion proteins (89), small-molecule inhibitors, novel drug delivery systems (49, 98–100), SIRP-1 and SIRP-2 applications (98), cis and trans interactions (49, 98, 99), and tumor selectivity enhancement (6) (Table 8). Furthermore, a combination of blockade of the CD47/SIRPα axis and secondary targets in the tumor microenvironment may also improve the clinical efficacy of current immunotherapeutic approaches (95).

In summary, the intricate dance of the CD47-SIRPα axis shields malignancies from immune scrutiny by issuing ‘don’t eat me’ signals that dampen macrophage phagocytosis. Overcoming these evasive tactics demands ongoing exploration of innovative cancer immunotherapeutic strategies targeting this axis, fueled by dedicated research and clinical trials. The current constraints of available treatments underline the pressing need for advancements. Furthermore, the specificity of CD47-targeted BsAbs limited to certain tumor types underscores the critical importance of precise malignancy identification and classification. As CD47 BsAbs progress through phases I and II clinical trials, the quest for the optimal dosage of dual antibodies becomes paramount.

Navigating this dynamic landscape calls for a profound understanding of the immune system, coupled with sophisticated designs for CD47 antagonists. This sets the stage for the emergence of new anti-CD47 drugs characterized by enhanced efficacy and safety. The notable progress achieved by innovative agents like IMM01 serves as a beacon of hope for patients facing unmet clinical needs. The future unfolds with the promise of transformative breakthroughs in cancer therapeutics, propelled by our ongoing exploration of the intricate interplay between CD47 and SIRPα.

CJ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HS: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZJ: Writing – review & editing. WT: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Zhengzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (CN) XTCX2023010 (recipient JY) and Talent Research Fund of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (recipient JY).

Author WT is the founder of the company ImmuneOnco Biopharmaceuticals Shanghai Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

ADCC, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity; ADCP, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis; ADCs, Antibody-drug conjugates; AEs, adverse events; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; Aza, Azacitidine; BsAbs, bispecific antibodies; CDC, complement dependent cytotoxicity; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; CR, complete response; Cri, incomplete count recovery; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; HR-MDS, higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome; IAP, integrin-associated protein; ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors; mAb, monoclonal antibody;

MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MM, multiple myeloma; NCT, National Clinical Trials Registry;

NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; NK, natural killer; OC, ovarian cancer; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PR, partial response; R/R, recurrent or refractory; RBC, red blood cells;

RO, receptor occupancy; RP2D, recommended phase II dose; SD, stable disease; SIRPα, signal regulatory protein α; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; TSP-1, thrombospondin-1; UCAR-T, universal chimeric antigen receptor T cell; VEN, venetoclax.

1. Wang Y, Zhang H, Liu C, Wang Z, Wu W, Zhang N, et al. Immune checkpoint modulators in cancer immunotherapy: recent advances and emerging concepts. J Hematol Oncol. (2022) 15:111. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01325-0

2. Marin-Acevedo JA, Kimbrough EO, Lou Y. Next generation of immune checkpoint inhibitors and beyond. J Hematol Oncol. (2021) 14:45. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01056-8

3. Qu T, Li B, Wang Y. Targeting CD47/SIRPα as a therapeutic strategy, where we are and where we are headed. biomark Res. (2022) 10:20. doi: 10.1186/s40364-022-00373-5

4. Jiang Z, Sun H, Yu J, Tian W, Song Y. Targeting CD47 for cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. (2021) 14:180. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01197-w

5. Yu J, Li S, Chen D, Liu D, Guo H, Yang C, et al. Crystal Structure of Human CD47 in Complex with Engineered SIRPα.D1(N80A). Molecules. (2022) 27(17):5574. doi: 10.3390/molecules27175574

6. Barclay AN, Van den Berg TK. The interaction between signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) and CD47: structure, function, and therapeutic target. Annu Rev Immunol. (2014) 32:25–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120142

7. Kuo TC, Chen A, Harrabi O, Sockolosky JT, Zhang A, Sangalang E, et al. Targeting the myeloid checkpoint receptor SIRPα potentiates innate and adaptive immune responses to promote anti-tumor activity. J Hematol Oncol. (2020) 13:160. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00989-w

8. Willingham SB, Volkmer JP, Gentles AJ, Sahoo D, Dalerba P, Mitra SS, et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:6662–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121623109

9. Li W, Wang F, Guo R, Bian Z, Song Y. Targeting macrophages in hematological Malignancies: recent advances and future directions. J Hematol Oncol. (2022) 15:110. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01328-x

10. Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Tang C, Myklebust JH, Varghese B, Gill S, et al. Anti-CD47 antibody synergizes with rituximab to promote phagocytosis and eradicate non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cell. (2010) 142(5):699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.044

11. Matthews AH, Pratz KW, Carroll MP. Targeting menin and CD47 to address unmet needs in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14(23):5906. doi: 10.3390/cancers14235906

12. Yang H, Xun Y, You H. The landscape overview of CD47-based immunotherapy for hematological Malignancies. biomark Res. (2023) 11:15. doi: 10.1186/s40364-023-00456-x

13. Li Y, Liu J, Chen W, Wang W, Yang F, Liu X, et al. A pH-dependent anti-CD47 antibody that selectively targets solid tumors and improves therapeutic efficacy and safety. J Hematol Oncol. (2023) 16:2. doi: 10.1186/s13045-023-01399-4

14. Zhang W, Huang Q, Xiao W, Zhao Y, Pi J, Xu H, et al. Advances in anti-tumor treatments targeting the CD47/SIRPα Axis. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:18. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00018

15. Yu J, Li S, Chen D, Liu D, Guo H, Yang C, et al. SIRPα-Fc fusion protein IMM01 exhibits dual anti-tumor activities by targeting CD47/SIRPα signal pathway via blocking the “don’t eat me” signal and activating the “eat me” signal. J Hematol Oncol. (2022) 15:167. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01385-2

16. Yu J, Li S, Chen D, Liu D, Guo H, Yang C, et al. SIRPα-Fc fusion protein IMM01 exhibits dual anti-tumor activities by targeting CD47/SIRPα signal pathway via blocking the "don't eat me" signal and activating the "eat me" signal. J Hematol Oncol. (2022) 15:167. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01385-2

17. Advani R, Flinn I, Popplewell L, Forero A, Bartlett NL, Ghosh N, et al. CD47 blockade by hu5F9-G4 and rituximab in non-hodgkin's lymphoma. New Engl J Med. (2018) 379:1711–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807315

18. Release. P. Zai lab announces second quarter 2022 financial results and corporate updates(2023). Available online at: https://irzailaboratorycom/news-releases/news-release-details/zai-lab-announces-second-quarter-2022-financial-results-and (Accessed 09-04-2023). Zai Lab Announces Second Quarter 2022 Financial Results and Corporate.

19. Release. P. Gilead to discontinue phase 3 ENHANCE study of magrolimab plus azacitidine in higher-risk MDS(2023). Available online at: https://wwwgileadcom/news-and-press/press-room/press-releases/2023/7/gilead-to-discontinue-phase-3-enhance-study-of-magrolimab-plus-azacitidine-in-higher-risk-mds (Accessed July 21, 2023).

20. Si Y, Zhang Y, Guan JS, Ngo HG, Totoro A, Singh AP, et al. Anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody-drug conjugate: A targeted therapy to treat triple-negative breast cancers. Vaccines (Basel). (2021) 9(8):882. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080882

21. Ansell SM, Maris MB, Lesokhin AM, Chen RW, Flinn IW, Sawas A, et al. Phase I study of the CD47 blocker TTI-621 in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic Malignancies. Clin Cancer research: an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. (2021) 27:2190–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3706

22. Petrova PS, Viller NN, Wong M, Pang X, Lin GH, Dodge K, et al. TTI-621 (SIRPαFc): A CD47-blocking innate immune checkpoint inhibitor with broad antitumor activity and minimal erythrocyte binding. Clin Cancer research: an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. (2017) 23:1068–79. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1700

23. Wilson WC, Bouchlaka MN, Capoccia BJ, Hiebsch RR, Donio MJ, Puro RJ, et al. Therapeutic potential of AO-176, a next generation humanized CD47 antibody, for hematologic Malignancies. Blood. (2018) 132:4180.

24. Logtenberg MEW, Scheeren FA, Schumacher TN. The CD47-SIRPα Immune checkpoint. Immunity. (2020) 52(5):742–52. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.011

25. Casey SC, Tong L, Li Y, Do R, Walz S, Fitzgerald KN, et al. MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science. (2016) 352(6282):227–31. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9935

26. Zhang H, Lu H, Xiang L, Bullen JW, Zhang C, Samanta D, et al. HIF-1 regulates CD47 expression in breast cancer cells to promote evasion of phagocytosis and maintenance of cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2015) 112:E6215–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520032112

27. Jia X, Yan B, Tian X, Liu Q, Jin J, Shi J, et al. CD47/SIRPα pathway mediates cancer immune escape and immunotherapy. Int J Biol Sci. (2021) 17:3281–7. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.60782

28. Shimizu A, Sawada K, Kobayashi M, Yamamoto M, Yagi T, Kinose Y, et al. Exosomal CD47 plays an essential role in immune evasion in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Res. (2021) 19:1583–95. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-20-0956

29. Xu T, Yu S, Zhang J, Wu S. Dysregulated tumor-associated macrophages in carcinogenesis, progression and targeted therapy of gynecological and breast cancers. J Hematol Oncol. (2021) 14:181. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01198-9

30. Luo X, Shen Y, Huang W, Bao Y, Mo J, Yao L, et al. Blocking CD47-SIRPα Signal axis as promising immunotherapy in ovarian cancer. Cancer Control. (2023) 30:10732748231159706. doi: 10.1177/10732748231159706

31. Champiat S, Cassier PA, Kotecki N, Korakis I, Vinceneux A, Jungels C, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and preliminary biomarker data of first-in-class BI 765063, a selective SIRPα inhibitor: Results of monotherapy dose escalation in phase 1 study in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. (2021) 39:2623. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.2623

32. Lakhani NJ, Patnaik A, Liao JB, Moroney JW, Miller DS, Fleming GF, et al. A phase Ib study of the anti-CD47 antibody magrolimab with the PD-L1 inhibitor avelumab (A) in solid tumor (ST) and ovarian cancer (OC) patients. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.5_suppl.18

33. Upton R, Banuelos A, Feng D, Biswas T, Kao K, McKenna K, et al. Combining CD47 blockade with trastuzumab eliminates HER2-positive breast cancer cells and overcomes trastuzumab tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2021) 118(29):e2026849118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2026849118

34. Tsao LC, Crosby EJ, Trotter TN, Agarwal P, Hwang BJ, Acharya C, et al. CD47 blockade augmentation of trastuzumab antitumor efficacy dependent on antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis. JCI Insight. (2019) 4(24):e131882. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131882

35. Nigro A, Ricciardi L, Salvato I, Sabbatino F, Vitale M, Crescenzi MA, et al. Enhanced expression of CD47 is associated with off-target resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib in NSCLC. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:3135. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03135

36. Samanta D, Park Y, Ni X, Li H, Zahnow CA, Gabrielson E, et al. Chemotherapy induces enrichment of CD47(+)/CD73(+)/PDL1(+) immune evasive triple-negative breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2018) 115:E1239–e48. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718197115

37. Manna PP, Frazier WA. CD47 mediates killing of breast tumor cells via Gi-dependent inhibition of protein kinase A. Cancer Res. (2004) 64:1026–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1708

38. Feliz-Mosquea YR, Christensen AA, Wilson AS, Westwood B, Varagic J, Meléndez GC, et al. Combination of anthracyclines and anti-CD47 therapy inhibit invasive breast cancer growth while preventing cardiac toxicity by regulation of autophagy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2018) 172:69–82. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4884-x

39. Iribarren K, Buque A, Mondragon L, Xie W, Lévesque S, Pol J, et al. Anticancer effects of anti-CD47 immunotherapy in vivo. Oncoimmunology. (2019) 8:1550619. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1550619

40. Cao X, Li B, Chen J, Dang J, Chen S, Gunes EG, et al. Effect of cabazitaxel on macrophages improves CD47-targeted immunotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer. J immunotherapy Cancer. (2021) 9(3):e002022. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002022

41. Candas-Green D, Xie B, Huang J, Fan M, Wang A, Menaa C, et al. Dual blockade of CD47 and HER2 eliminates radioresistant breast cancer cells. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:4591. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18245-7

42. Meng Z, Wang Z, Guo B, Cao W, Shen H. TJC4, a differentiated anti-CD47 antibody with novel epitope and RBC sparing properties. Blood. (2019) 134:4063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-122793

43. Sikic BI, Lakhani N, Patnaik A, Shah SA, Chandana SR, Rasco D, et al. First-in-human, first-in-class phase I trial of the anti-CD47 antibody hu5F9-G4 in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin oncology: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. (2019) 37:946–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02018

44. Eladl E, Tremblay-LeMay R, Rastgoo N, Musani R, Chen W, Liu A, et al. Role of CD47 in hematological Malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. (2020) 13:96. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00930-1

45. Yu J, Li S, Chen D, Liu D, Guo H, Yang C, et al. IMM0306, a fusion protein of CD20 mAb with the CD47 binding domain of SIRPα, exerts excellent cancer killing efficacy by activating both macrophages and NK cells via blockade of CD47-SIRPα interaction and FcγR engagement by simultaneously binding to CD47 and CD20 of B cells. Leukemia. (2023) 37:695–8. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01805-9

46. Abrisqueta P, Sancho J-M, Cordoba R, Persky DO, Andreadis C, Huntington SF, et al. Anti-CD47 antibody, CC-90002, in combination with rituximab in subjects with relapsed and/or refractory non-hodgkin lymphoma (R/R NHL). Blood. (2019) 134:4089. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-125310

47. Qu T, Zhong T, Pang X, Huang Z, Jin C, Wang ZM, et al. Ligufalimab, a novel anti-CD47 antibody with no hemagglutination demonstrates both monotherapy and combo antitumor activity. J immunotherapy Cancer. (2022) 10(11):e005517. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-005517

48. Piccione EC, Juarez S, Liu J, Tseng S, Ryan CE, Narayanan C, et al. A bispecific antibody targeting CD47 and CD20 selectively binds and eliminates dual antigen expressing lymphoma cells. mAbs. (2015) 7:946–56. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1062192

49. Ma L, Zhu M, Gai J, Li G, Chang Q, Qiao P, et al. Preclinical development of a novel CD47 nanobody with less toxicity and enhanced anti-cancer therapeutic potential. J Nanobiotechnology. (2020) 18(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12951-020-0571-2

50. Dheilly E, Moine V, Broyer L, Salgado-Pires S, Johnson Z, Papaioannou A, et al. Selective blockade of the ubiquitous checkpoint receptor CD47 is enabled by dual-targeting bispecific antibodies. Mol Ther. (2017) 25:523–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.11.006

51. Chauchet X, Cons L, Chatel L, Daubeuf B, Didelot G, Moine V, et al. CD47xCD19 bispecific antibody triggers recruitment and activation of innate immune effector cells in a B-cell lymphoma xenograft model. Exp Hematol Oncol. (2022) 11:26. doi: 10.1186/s40164-022-00279-w

52. Querfeld C, Thompson JA, Taylor MH, DeSimone JA, Zain JM, Shustov AR, et al. Intralesional TTI-621, a novel biologic targeting the innate immune checkpoint CD47, in patients with relapsed or refractory mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome: a multicentre, phase 1 study. Lancet Haematol. (2021) 8:e808–e17. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00271-4

53. Patel K, Zonder JA, Sano D, Maris M, Lesokhin A, von Keudell G, et al. CD47-blocker TTI-622 shows single-agent activity in patients with advanced relapsed or refractory lymphoma: update from the ongoing first-in-human dose escalation study. Blood. (2021) 138:3560. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-153683

54. Kauder SE, Kuo TC, Harrabi O, Chen A, Sangalang E, Doyle L, et al. ALX148 blocks CD47 and enhances innate and adaptive antitumor immunity with a favorable safety profile. PloS One. (2018) 13:e0201832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201832

55. Yu J, Song Y, Tian W. How to select IgG subclasses in developing anti-tumor therapeutic antibodies. J Hematol Oncol. (2020) 13:45. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00876-4

56. Horwitz SM, Foran JM, Maris M, Lue JK, Sawas A, Okada C, et al. Updates from ongoing, first-in-human phase 1 dose escalation and expansion study of TTI-621, a novel biologic targeting CD47, in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic Malignancies. Blood. (2021) 138:2448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-154490

57. Kim TM, Lakhani N, Gainor J, Kamdar M, Fanning P, Squifflet P, et al. ALX148, a CD47 blocker, in combination with rituximab in patients with non-hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. (2020) 136:13–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2020-135941

58. Sun M, Qi J, Zheng W, Song L, Jiang B, Wang Z, et al. Preliminary results of a first-in-human phase I dtudy of IMM01, SIRPα Fc protein in patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. (2021) 39:2550. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.2550

59. Zhou K, Song Y, Yi T, Hou S, Liu X, Lin N, et al. IMM01 plus tislelizumab in prior Anti-PD-1 failed classic hodgkin lymphoma: an open label, multicenter, phase 2 study (IMM01-04) evaluating safety as well as preliminary anti-tumor activity. Blood. (2023) 142(Supplement 1):609. doi: 10.1182/blood-2023-174829

60. Majeti R, Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Pang WW, Jaiswal S, Gibbs KD Jr., et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. (2009) 138:286–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045

61. Mohty R, Al Hamed R, Bazarbachi A, Brissot E, Nagler A, Zeidan A, et al. Treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes in the era of precision medicine and immunomodulatory drugs: a focus on higher-risk disease. J Hematol Oncol. (2022) 15:124. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01346-9

62. Liu J, Wang L, Zhao F, Tseng S, Narayanan C, Shura L, et al. Pre-clinical development of a humanized anti-CD47 antibody with anti-cancer therapeutic potential. PloS One. (2015) 10:e0137345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137345

63. Sallman DA, Donnellan WB, Asch AS, Lee DJ, Malki MA, Marcucci G, et al. The first-in-class anti-CD47 antibody Hu5F9-G4 is active and well tolerated alone or with azaciti dine in AML and MDS patients: Initial phase 1b results. J Clin Oncol. (2019) 37:7009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.70

64. Daver NG, Vyas P, Kambhampati S, Malki MMA, Larson RA, Asch AS, et al. Tolerability and efficacy of the first-in-class anti-CD47 antibody magrolimab combined with azacitidine in frontline TP53m AML patients: Phase 1b results. J Clin Oncol. (2022) 40:7020. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.7020

65. Sallman D, Asch A, Kambhampati S, Malki MA, Zeidner J, Donnellan W, et al. AML-196: the first-in-class anti-CD47 antibody magrolimab in combination with azacitidine is well tolerated and effective in AML patients: phase 1b results. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leukemia. (2021) 21:S290. doi: 10.1016/S2152-2650(21)01694-3

66. Daver N, Konopleva M, Maiti A, Kadia TM, DiNardo CD, Loghavi S, et al. Phase I/II study of azacitidine (AZA) with venetoclax (VEN) and magrolimab (Magro) in patients (pts) with newly diagnosed older/unfit or high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and relapsed/refractory (R/R) AML. Blood. (2021) 138:371. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-153638

67. Qi J, Li J, Jiang B, Jiang B, Liu H, Cao X, et al. A phase I/IIa study of lemzoparlimab, a monoclonal antibody targeting CD47, in patients with relapsed and/or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS): initial phase I results. Blood. (2020) 136:30–1. doi: 10.1182/blood-2020-134391

68. Zeidan AM, DeAngelo DJ, Palmer JM, Seet CS, Tallman MS, Wei X, et al. A phase I study of CC-90002, a monoclonal antibody targeting CD47, in patients with relapsed and/or refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): final results. Blood. (2019) 134:1320. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-125363

69. Narla RK, Modi H, Bauer D, Abbasian M, Leisten J, Piccotti JR, et al. Modulation of CD47-SIRPα innate immune checkpoint axis with Fc-function detuned anti-CD47 therapeutic antibody. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2022) 71(2):473–89. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-03010-6

70. Zeidan AM, DeAngelo DJ, Palmer J, Seet CS, Tallman MS, Wei X, et al. Phase 1 study of anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody CC-90002 in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Ann Hematology. (2022) 101:557–69. doi: 10.1007/s00277-021-04734-2

71. Miao M, Teng Q, Wu D, Jiang Z, Jiang S, Li F, et al. AK117 (anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody) in combination with azacitidine for newly diagnosed higher risk myelodysplastic syndrome (HR-MDS): AK117-103 Phase 1b results. Blood. (2023) 142(Supplement 1):1865. doi: 10.1182/blood-2023-179099

72. Lin GHY, Chai V, Lee V, Dodge K, Truong T, Wong M, et al. TTI-621 (SIRPαFc), a CD47-blocking cancer immunotherapeutic, triggers phagocytosis of lymphoma cells by multiple polarized macrophage subsets. PloS One. (2017) 12:e0187262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187262

73. Johnson Z, Papaioannou A, Bernard L, Cosimo E, Daubeuf B, Richard F, et al. Bispecific antibody targeting of CD47/CD19 to promote enhanced phagocytosis of patient B lymphoma cells. J Clin Oncol. (2015) 33:e14016–e. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.33.15_suppl.e14016

74. Tong H, Gao S, Yang W, Li J, Yin Q, Zhao X, et al. Preliminary results of a phase 2 study of IMM01 combined with azacitidine (AZA) as the first-line treatment in adult patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). Blood. (2023) 142(Supplement 1):1859. doi: 10.1182/blood-2023-181501

75. Yang W, Gao S, Yan X, Guo R, Han L, Li F, et al. Preliminary results of a phase 2 study of IMM01 combined with azacitidine (AZA) as the first-line treatment in adult patients with higher risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Blood. (2023) 142(Supplement 1):320. doi: 10.1182/blood-2023-174420

76. Wang H, Zhang Q, Teng Q, Li Z, Liu H, Wang ZM, et al. A Phase 1b Study Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of AK117 (anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody) in Combination with Azacitidine in Patients with Treatment-Naïve Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood. (2023) 142(Supplement 1):4280. doi: 10.1182/blood-2023-180618

77. Yue Y, Cao Y, Wang F, Zhang N, Qi Z, Mao X, et al. Bortezomib-resistant multiple myeloma patient-derived xenograft is sensitive to anti-CD47 therapy. Leuk Res. (2022) 122:106949. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2022.106949

78. Sun J, Muz B, Alhallak K, Markovic M, Gurley S, Wang Z, et al. Targeting CD47 as a novel immunotherapy for multiple myeloma. Cancers (Basel). (2020) 12:305. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020305

79. Li J, Yang Y, Wang W, Xu J, Sun Y, Jiang J, et al. Single-cell atlas of the immune microenvironment reveals macrophage reprogramming and the potential dual macrophage-targeted strategy in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. (2023) 201:917–34. doi: 10.1111/bjh.18708

80. Lu Q, Yang D, Li H, Zhu Z, Zhang Z, Chen Y, et al. Delivery of CD47-SIRPα checkpoint blocker by BCMA-directed UCAR-T cells enhances antitumor efficacy in multiple myeloma. Cancer Lett. (2024) 585:216660. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216660

81. Piccio L, Vermi W, Boles KS, Fuchs A, Strader CA, Facchetti F, et al. Adhesion of human T cells to antigen-presenting cells through SIRPbeta2-CD47 interaction costimulates T-cell proliferation. Blood. (2005) 105:2421–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2823

82. Grandclément C, Estoppey C, Dheilly E, Panagopoulou M, Monney T, Dreyfus C, et al. Development of ISB 1442, a CD38 and CD47 bispecific biparatopic antibody innate cell modulator for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:2054. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-46310-y

83. Paul B, Liedtke M, Khouri J, Rifkin R, Gandhi MD, Kin A, et al. A phase II multi-arm study of magrolimab combinations in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Future Oncol. (2023) 19:7–17. doi: 10.2217/fon-2022-0975

84. Buatois V, Johnson Z, Salgado-Pires S, Papaioannou A, Hatterer E, Chauchet X, et al. Preclinical development of a bispecific antibody that safely and effectively targets CD19 and CD47 for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Mol Cancer Ther. (2018) 17:1739–51. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-1095

85. Chen JY, McKenna KM, Choi TS, Duan J, Brown L, Stewart JJ, et al. RBC-specific CD47 pruning confers protection and underlies the transient anemia in patients treated with anti-CD47 antibody 5F9. Blood. (2018) 132:2327. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-99-115674

86. Ding X, Wang J, Huang M, Chen Z, Liu J, Zhang Q, et al. Loss of microglial SIRPα promotes synaptic pruning in preclinical models of neurodegeneration. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:2030. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22301-1

87. Wang T, Wang SQ, Du YX, Sun DD, Liu C, Liu S, et al. Gentulizumab, a novel anti-CD47 antibody with potent antitumor activity and demonstrates a favorable safety profile. J Transl Med. (2024) 22:220. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04710-6

88. Patel SA, Bello E, Wilks A, Gerber JM, Sadagopan N, Cerny J. Harnessing autologous immune effector mechanisms in acute myeloid leukemia: 2023 update of trials and tribulations. Leuk Res. (2023) 134:107388. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2023.107388

89. Yang Y, Yang Z, Yang Y. Potential role of CD47-directed bispecific antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:686031. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.686031

90. Jain N, Mamgain M, Chowdhury SM, Jindal U, Sharma I, Sehgal L, et al. Beyond Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors in mantle cell lymphoma: bispecific antibodies, antibody–drug conjugates, CAR T-cells, and novel agents. J Hematol Oncol. (2023) 16:99. doi: 10.1186/s13045-023-01496-4

91. Pietsch EC, Dong J, Cardoso R, Zhang X, Chin D, Hawkins R, et al. Anti-leukemic activity and tolerability of anti-human CD47 monoclonal antibodies. Blood Cancer J. (2017) 7:e536–e. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2017.7

92. Evans TRJ, Italiano A, Eskens F, Symeonides SN, Bexon AS, Graham P, et al. Phase 1-2 study of TI-061 alone and in combination with other anti-cancer agents in patients with advanced Malignancies. J Clin Oncol. (2017) 35:TPS3109–TPS. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.TPS3109

93. Release P. Gilead announces partial clinical hold for studies evaluating magrolimab in combination with azacitidine(2022). Available online at: https://wwwgileadcom/news-and-press/press-room/press-releases/2022/1/gilead-announces-partial-clinical-hold-for-studies-evaluating-magrolimab-in-combination-with-azacitidine (Accessed January 25, 2022).

94. Release P. FDA lifts partial clinical hold on MDS and AML magrolimab studies(2022). Available online at: https://wwwgileadcom/news-and-press/press-room/press-releases/2022/4/fda-lifts-partial-clinical-hold-on-mds-and-aml-magrolimab-studies (Accessed April 11, 2022).

95. Release. P. Gilead announces partial clinical hold for magrolimab studies in AML(2023). Available online at: https://www.gilead.com/news-and-press/press-room/press-releases/2023/8/gilead-announces-partial-clinical-hold-for-magrolimab-studies-in-aml (Accessed 09-04-2023).

96. Jeanne A, Sarazin T, Charlé M, Moali C, Fichel C, Boulagnon-Rombi C, et al. Targeting ovarian carcinoma with TSP-1:CD47 antagonist TAX2 activates anti-tumor immunity. . Cancers (Basel). (2021) 13(19):5019. doi: 10.3390/cancers13195019

97. Tian Z, Liu M, Zhang Y, Wang X. Bispecific T cell engagers: an emerging therapy for management of hematologic Malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. (2021) 14:75. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01084-4

98. Ni H, Cao L, Wu Z, Wang L, Zhou S, Guo X, et al. Combined strategies for effective cancer immunotherapy with a novel anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody. Cancer Immunology Immunother. (2022) 71:353–63. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-02989-2

99. Tahk S, Vick B, Hiller B, Schmitt S, Marcinek A, Perini ED, et al. SIRPα-αCD123 fusion antibodies targeting CD123 in conjunction with CD47 blockade enhance the clearance of AML-initiating cells. J Hematol Oncol. (2021) 14:155. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01163-6

100. Billerhart M, Schönhofer M, Schueffl H, Polzer W, Pichler J, Decker S, et al. CD47-targeted cancer immunogene therapy: Secreted SIRPα-Fc fusion protein eradicates tumors by macrophage and NK cell activation. Mol Ther - Oncolytics. (2021) 23:192–204. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2021.09.005

101. Wang H, Sun Y, Zhou X, Chen C, Jiao L, Li W, et al. CD47/SIRPα blocking peptide identification and synergistic effect with irradiation for cancer immunotherapy. J immunotherapy Cancer. (2020) 8(2):e000905. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000905

102. Andrejeva G, Capoccia BJ, Hiebsch RR, Donio MJ, Darwech IM, Puro RJ, et al. Novel SIRPα Antibodies that induce single-agent phagocytosis of tumor cells while preserving T cells. J Immunol. (2021) 206:712–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2001019

103. Weiskopf K, Ring AM, Ho CCM, Volkmer J-P, Levin AM, Volkmer AK, et al. Engineered SIRPα Variants as immunotherapeutic adjuvants to anticancer antibodies. Science. (2013) 341:88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1238856

104. Oldenborg PA, Zheleznyak A, Fang YF, Lagenaur CF, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Sci (New York NY). (2000) 288(5473):2051–4. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2051

Keywords: cd47, SIRPα, signaling pathway, monoclonal antibody, targeted therapy, cancer immunotherapy

Citation: Jiang C, Sun H, Jiang Z, Tian W, Cang S and Yu J (2024) Targeting the CD47/SIRPα pathway in malignancies: recent progress, difficulties and future perspectives. Front. Oncol. 14:1378647. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1378647

Received: 30 January 2024; Accepted: 20 June 2024;

Published: 05 July 2024.

Edited by:

Shyam Patel, University of Massachusetts Medical School, United StatesReviewed by:

Zhifang Zhang, City of Hope National Medical Center, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Jiang, Sun, Jiang, Tian, Cang and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jifeng Yu, WXVqaWZlbmd6enVAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Wenzhi Tian, d2VuemhpLnRpYW5AaW1tdW5lb25jby5jb20=; Shundong Cang, c2h1bmRvbmdjYW5nQHp6dS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡ORCID: Jifeng Yu, orcid.org/0000-0003-1117-4385

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.