95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 27 February 2024

Sec. Gynecological Oncology

Volume 14 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1356654

This article is part of the Research Topic Cervical Screening Awareness Week 2023: Integrating Cervical Cancer Screening and Precancer Treatments View all 10 articles

Fan Lee1*

Fan Lee1* Shannon McGue2

Shannon McGue2 John Chapola3

John Chapola3 Wezzie Dunda4

Wezzie Dunda4 Jennifer H. Tang1,4,5

Jennifer H. Tang1,4,5 Margret Ndovie4

Margret Ndovie4 Lizzie Msowoya4

Lizzie Msowoya4 Victor Mwapasa6

Victor Mwapasa6 Jennifer S. Smith5,7

Jennifer S. Smith5,7 Lameck Chinula1,4,5,6

Lameck Chinula1,4,5,6Objective: To explore the experiences of Malawian women who underwent a human papillomavirus (HPV)-based screen-triage-treat algorithm for cervical cancer (CxCa) prevention. This algorithm included GeneXpert® HPV testing of self-collected vaginal samples, visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and colposcopy for HPV-positive women, and thermal ablation of ablation-eligible women.

Method: In-depth interviews were conducted with participants of a trial that evaluated the feasibility of a HPV-based screen-triage-treat algorithm among women living with HIV and HIV negative women in Lilongwe, Malawi. Participants were recruited from 3 groups: 1) HPV-negative; 2) HPV-positive/VIA-negative; 3) HPV-positive/VIA-positive and received thermal ablation. Interviews explored baseline knowledge of CxCa and screening, attitudes towards self-collection, and understanding of test results. Content analysis was conducted using NVIVO v12.

Results: Thematic saturation was reached at 25 interviews. Advantages of HPV self-collection to participants were convenience of sampling, same-day HPV results and availability of same-day treatment. There was confusion surrounding HPV-positive/VIA-negative results, as some participants still felt treatment was needed. Counseling, and in particular anticipatory guidance, was key in helping participants understand complex screening procedures and results. Overall, participants expressed confidence in the HPV screen-triage-treat strategy.

Discussion: HPV testing through self-collected samples is a promising tool to increase CxCa screening coverage. A multi-step screening algorithm utilizing HPV self-testing, VIA triage and thermal ablation treatment requires proper counseling and anticipatory guidance to improve patient understanding. Incorporating thorough counseling in CxCa screening programs can change women’s perspectives about screening, build trust in healthcare systems, and influence healthcare seeking behavior towards routine screening and prevention.

Malawi has the highest cervical cancer (CxCa) mortality rate in the world (51.5 deaths/100,000 per year), seven times higher than the global rate (1). This disease burden is largely due to the high prevalence of HIV (>9% for women 15-50 years of age) (2) and low CxCa screening coverage (3). For the last two decades, the national CxCa screening program in Malawi has been using visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) for screening and cryotherapy for treatment of VIA-positive lesions amenable for ablative therapy. However, a comprehensive evaluation of this program in 2015 showed that screening coverage has remained low (<27%) and less than half of those who required treatment received treatment (3).

Lack of trained staff was cited as the main challenge in offering CxCa screening by service providers in Malawi (4). Pelvic exam-based screening for cervical cancer, such as VIA, requires trained providers, adequate facilities, and patient acceptability of exams, thus limiting screening efficiency, access, and uptake. Human papillomavirus (HPV) screening by self-collection can bypass some of these challenges. The detection of high-risk types of HPV associated with CxCa has improved the accuracy of detecting cervical precancer (5) and was recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2021 to be the primary screening method, when available (6). Recent advancements in technology, such as GeneXpert® HPV tests (Cepheid Inc, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), has made HPV testing available in low-resource settings and allow the possibility of same-day treatment because of the quick result turnaround (about 1-2 hours with GeneXpert®). Self-collection of vaginal sample for HPV testing has been validated as an effective and sensitive method for CxCa screening if highly sensitive assays are utilized, with notably lower provider burden compared to provider-collected tests (5). HPV self-collection has been shown to increase CxCa screening compared to VIA (7) and is acceptable to women all over the world (8), including in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (9).

The biggest limitation to same-day treatment of cervical precancerous lesions in Malawi was maintaining functional cryotherapy machines and sustaining the supply of refrigerant gas (3). Thermal ablation, a battery-powered, portable, and less time-intensive treatment modality is replacing cryotherapy as the preferred treatment modality in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). With increasing evidence of safety, efficacy, and the ability to increase same-day screening and treatment (10, 11), the Malawi Ministry of Health (MoH) added thermal ablation as a treatment option in the national screening guidelines (12).

In line with WHO and Malawi MoH recommendations, we implemented a HPV-based screen-triage-treat algorithm that incorporates the strategies of HPV self-collection and same-day thermal ablation treatment. Our single-arm prospective trial evaluated the feasibility and performance of this algorithm in Lilongwe, Malawi among women living with HIV (WHIV) and HIV-negative women (13). This manuscript focuses on the study’s secondary aim, which was to explore the experiences of the participants. Perceptions of HPV-based screening have primarily been evaluated in HPV/Pap smear algorithms among patients in high income countries (14, 15). This study uniquely evaluated the experience of women undergoing a HPV/VIA screen-triage-treat algorithm, including acceptance of HPV self-collection, understanding of results, and challenges posed by a multistep screening process.

Participants for this qualitative sub-study were recruited from a single-arm prospective study that investigated a novel HPV screen-triage-treat strategy among 1,250 women (625 WHIV and 625 HIV-uninfected) in Lilongwe, Malawi. The strategy consisted of 1) GeneXpert® HPV testing of self-collected cervicovaginal samples; 2) VIA and colposcopy for HPV-positive women; and 3) thermal ablation for HPV-positive/ablation-eligible women. Colposcopy was conducted following VIA to determine final eligibility for thermal ablation, and additional samples (endocervical curettage and cervical biopsy or pap smear) were collected based on colposcopy results for other study objectives (see protocol paper for details) (13). For this qualitative sub-study, we focused on the HPV self-collection screening, VIA triage, and thermal ablation treatment components of the algorithm.

The parent study and this qualitative sub-study were conducted at UNC Project-Malawi’s Tidziwe Centre clinic in Lilongwe, Malawi. UNC Project-Malawi is a collaboration between the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Malawi MoH. Recruitment of participants for the parent study are detailed in the protocol paper (13). Briefly, study staff provided educational talks about cervical cancer screening and the study in waiting areas of outpatient clinics that provided reproductive health and HIV care services. Women who were interested in the study were scheduled for screening at the UNC Project-Malawi research clinic. On arrival, informed consent began with a summary of study goals and introduction to the new approach to cervical cancer screening employed in the study. Specifically, counseling was focused on HPV, its relationship to cervical cancer and detailed descriptions of each screening step. For those who continued to be interested, the remainder of the informed consent was completed, which further included counseling on what to expect at each step of screening and after each result. During screening, participants’ understanding of procedures and results was continually assessed and counseling was reiterated as needed. Study eligibility criteria included: femal1es between 25-50 years of age; non-pregnant; at least 12 weeks postpartum; and able and willing to provide written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: current or prior history of cervical, vaginal, or vulvar cancer; current symptomatic sexually transmitted infection (STI) requiring treatment; prior HPV vaccination; allergy to acetic acid; or history of total hysterectomy.

At the enrollment visit of the parent study, participants were asked if they were interested in joining the qualitative sub-study. Convenience sampling was used among those who expressed interest and the sub-study participants were recruited via phone call by study staff. Those interested were asked to come back to Tidziwe Centre to consent and enroll in the sub-study. We planned to enroll up to thirty women for in-depth-interviews (IDIs) across 3 groups of screening outcomes: 1) those who screened negative on self-collection HPV test (HPV-negative); 2) those who screened positive on self-collection HPV test but had a negative VIA (HPV-positive/VIA-negative) and did not receive treatment; and 3) those who screened positive on HPV self-collection, had a positive VIA triage exam (HPV-positive/VIA-positive) and received same-day thermal ablation. All participants received transport reimbursement, as approved by the local ethics committee.

Semi-structured IDIs were developed around four main domains of inquiry: 1) baseline knowledge and perception of CxCa and CxCa screening; 2) attitudes towards self-collection; 3) experience with the screen-triage-treat procedures; and 4) understanding of screening results. Domains were developed based on existing literature that assessed acceptability of and perspectives on HPV-based screening (9, 16, 17). Interviews were conducted in Chichewa, the local language, by study staff experienced in qualitative data collection methods (WD). Interviews were audiotaped and then translated and transcribed into English. Completed transcripts were reviewed immediately by study investigators and analyzed for emerging and/or new themes to inform the questions for subsequent interviews. This iterative process ensured saturation of themes and depth of content within the predetermined domains of inquiry.

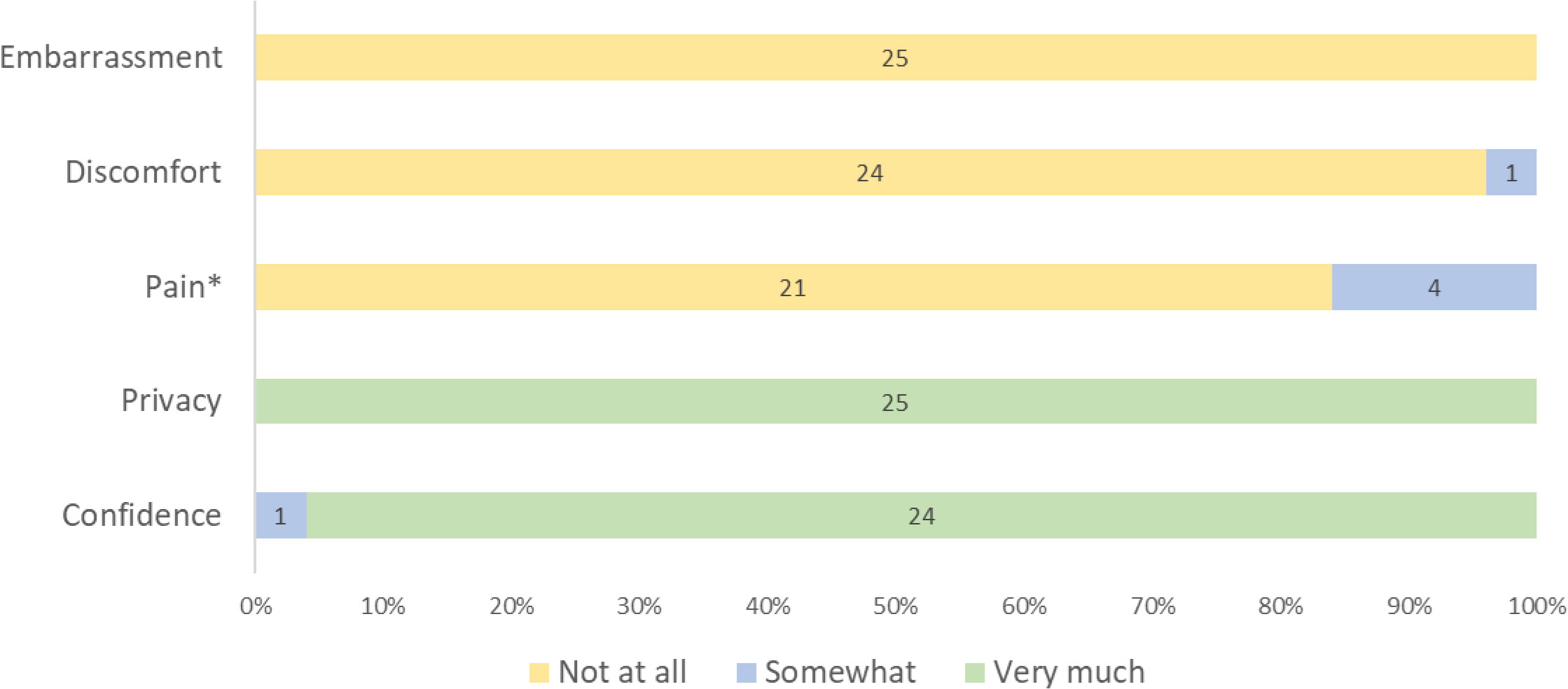

Additionally, five survey questions specific to participants’ HPV self-collection experience were administered after IDIs. The survey asked participants to rank whether they felt embarrassed, experienced discomfort, experienced pain, had privacy, and felt confident that they self-collected correctly on a three-point scale of 1) not at all; 2) somewhat; and 3) very much.

Three qualitative investigators (FL, SM, JC) independently reviewed and coded three transcripts at a time using thematic analysis, followed by a group discussion, to identify relationships between emerging themes and ensure relevance to research questions. This was repeated until the code book was finalized. The code book and IDIs were uploaded to NVIVO 12 software. To ensure validity of coding and robustness of analysis, nine interviews were coded by all three investigators and the remaining 16 were doubly coded. The code book was refined as analysis progressed. An Excel spreadsheet was used to structure and compile all extracted quotes for each code. The quotes were reviewed by all three coders and themes were revised until it was felt that they accurately reflected the data.

Survey data on HPV self-collection experience was entered into an Excel spreadsheet, and descriptive statistics were used for analysis.

This study was approved by Malawi National Health Sciences Research Committee and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institution Review Board. All participants underwent informed consent and provided written consent.

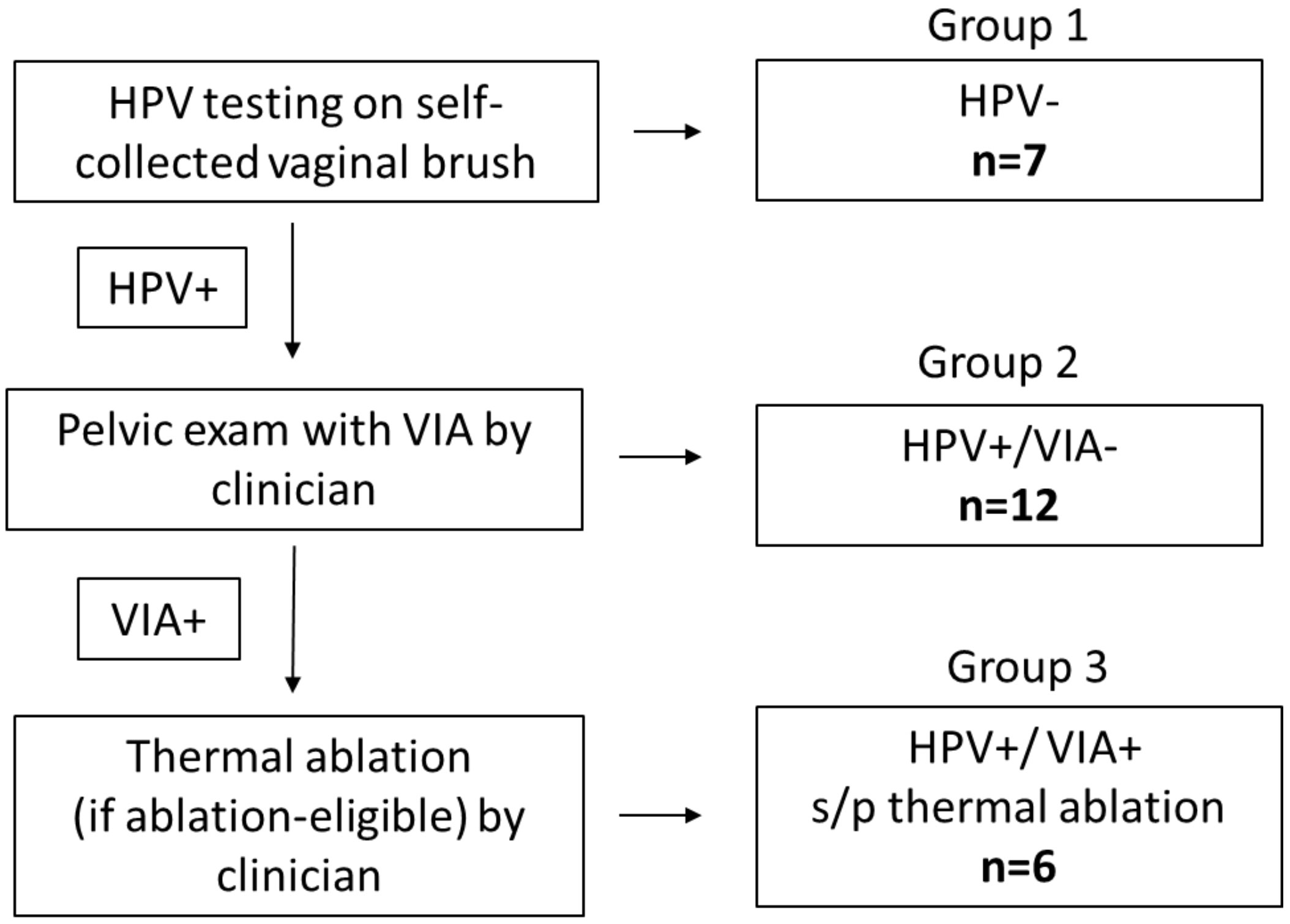

Between July 2020 – March 2021, we interviewed 25 women across the three groups of screening outcomes. Thematic saturation was reached at seven for Group 1, twelve for Group 2, and six for Group 3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Screening algorithm, screening outcomes (Group 1: HPV-negative; Group 2: HPV-positive/VIA-negative; Group 3: HPV-positive/VIA-positive and underwent thermal ablation) and number of participants interviewed in each group. HPV, Human papillomavirus (testing for high risk HPV); VIA, Visual inspection with acetic acid s/p: status post. Healthcare provider included nurses and clinicians.

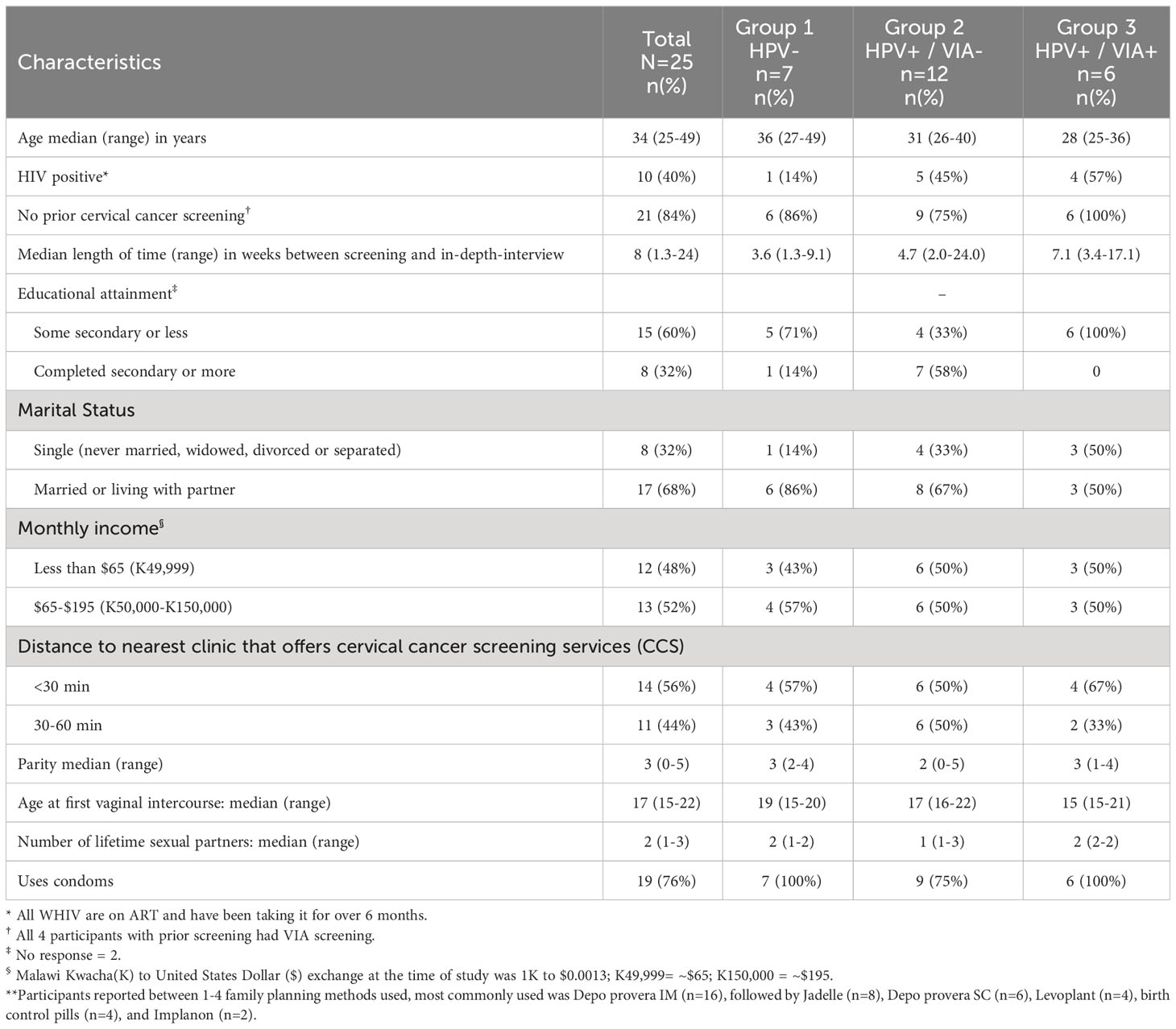

Participants were between 25-49 years old, with a median age of 34 (Table 1). Overall, ten (40%) of participants were WHIV (one in Group 1, five in Group 2, and four in Group 3). Most participants (84%) reported no prior CxCa screening; for those who did, the prior screening method reported was VIA. The majority of participants (72%) report a travel time between 30-60 minutes to reach the nearest clinic that offered CxCa screening. Of note, participants in Group 3 had a longer time between initial HPV screening and their IDI (median of 7 weeks vs. 3-4 weeks for Groups 1 & 2). Baseline socioeconomic characteristics were similar across the three groups. Most (60%) had at most some secondary school education, most (68%) were married or living with their partner, and most (64%) worked outside the house. Half of the participants (48%) made less than the equivalent of about $2 per day (<K49,999 per month), and the others (52%) made the equivalent of about $2-6 per day (K50,000-K150,000 per month). The median age at first vaginal intercourse among participants was 17 years, with a range of 15-22 years. The median number of lifetime partners was two, with a range of 1-3. Most (76%) reported using condoms at least some of the time.

Table 1 Baseline demographic of participants by self-collection HPV screening and VIA triage result.

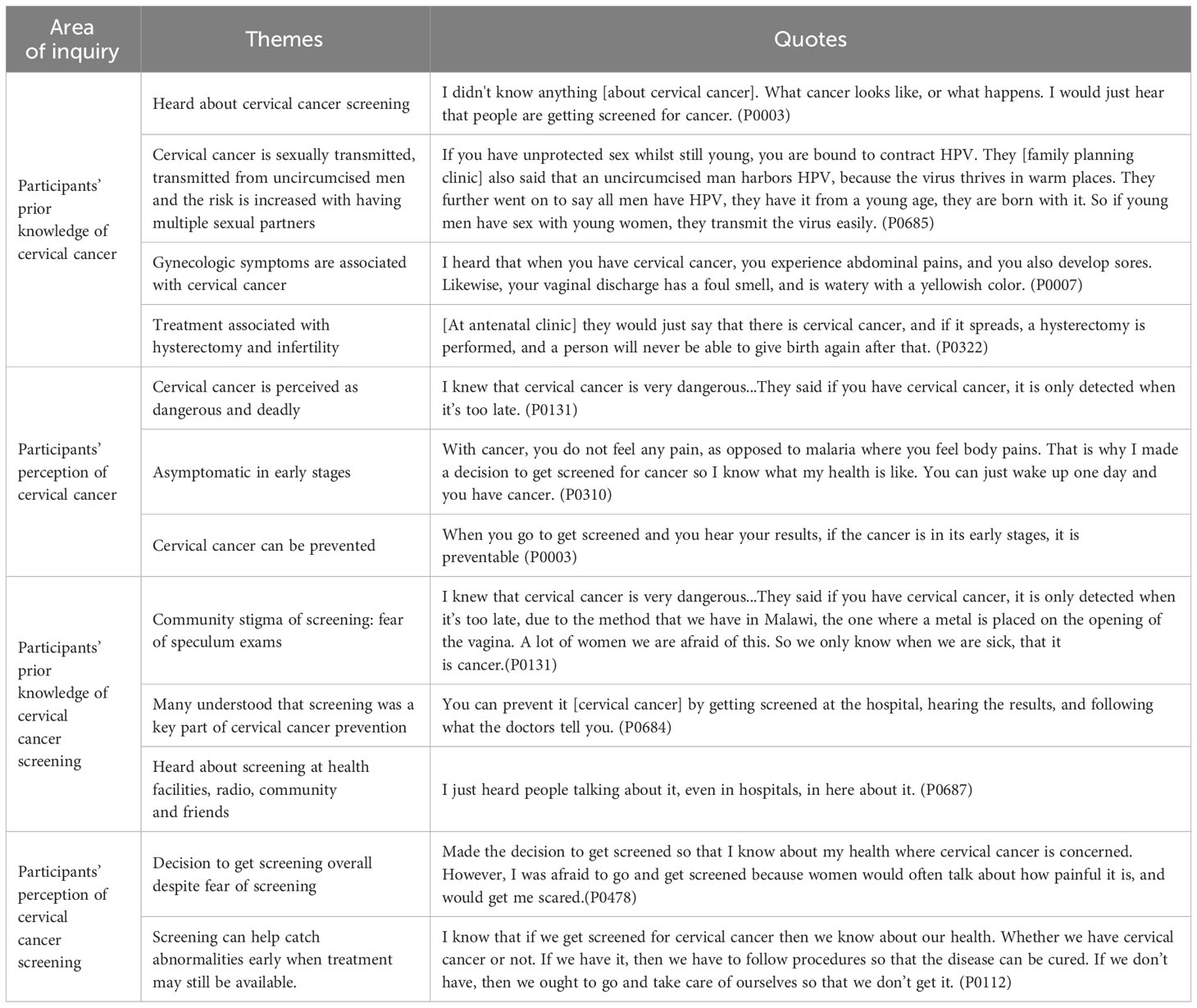

All participants had heard of CxCa, predominantly from CxCa screening messages on the radio, at clinics (antenatal, family planning and HIV), and/or from other women in the community (Table 2). Participants’ reported that CxCa is associated with sexual transmission, early sexual debut, and having multiple sexual partners, specifically with uncircumcised men. Some participants described CxCa as asymptomatic in the early stage. Others described gynecological symptoms, such as vaginal discharge, abnormal vaginal bleeding, abdominal pains, and genital sores, as associated with CxCa. Several participants reported that CxCa can spread to the womb and treatment involves hysterectomy, which leads to the inability to give birth again. The general perception of CxCa was that it is dangerous and deadly when detected in advanced stages when it is too late for treatment (Table 2). All felt that CxCa can be prevented; some reported prevention through lifestyle changes, such as limiting number of sexual partners, male circumcision, and vaginal hygiene. Several participants also specifically reported that CxCa can be prevented with screening.

Table 2 Participants’ prior knowledge and perception of cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening before undergoing self-collection HPV-based screen-triage-and treat program.

Participants reported that in their communities, screening is associated with the embarrassment and painful speculum exams (Table 2) and that these fears hinder screening attendance. Many had heard about screening through clinics (e.g., antenatal or family planning), and some were encouraged by clinicians or other women to attend screening. Some expressed initial hesitancy towards screening based on hearsay from the community, however, all participants had a positive perception of screening and believed that screening can prevent disease. The predominant reason participants decided to undergo screening was to know about their health and to catch abnormalities at an early stage when treatment was still available.

All participants reported a positive overall experience with self-collection of vaginal samples for HPV testing (Table 3). All expressed understanding of the self-collection process and many were able to describe the steps in detail even weeks after screening. They felt well-counseled on the collection steps, described it as an easy procedure, and valued the quick turn-around of HPV results. When participants were asked to rate a series of experiences during self-collection, all 25 participants reported no embarrassment, only one reported discomfort (rated as mild), and only four reported pain (rated as mild by all four) (Figure 2). On further inquiry, mild pain was described as more of a “discomfort” or “sensation” or “pinch” by participants (Table 3). All participants reported they had very good privacy, and all but one reported being very confident in collecting the sample correctly (Figure 2). Many suggested that this method could be more acceptable to women who feel embarrassed to undress for speculum-based screening (Table 3).

Figure 2 Participants’ reported HPV self-collection experience on a three point scale (N=25). *Of those who reported “somewhat” pain during HPV self-collection, 3 had HPV negative and 1 had HPV positive results.

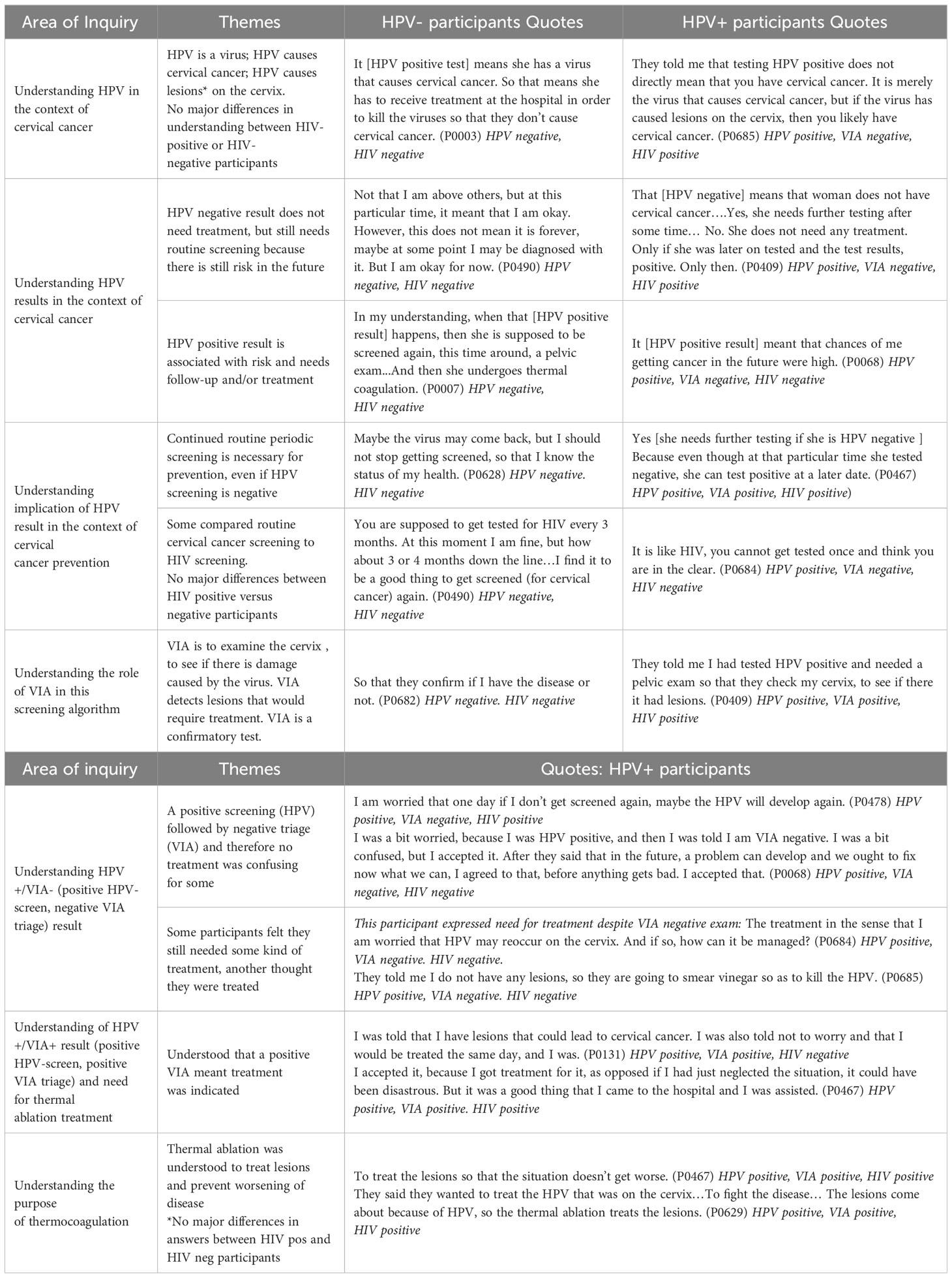

All participants, except one, reported that they had never heard of HPV prior to being involved in the research study. After undergoing screening and counseling, participants were able to describe HPV as a virus that can cause CxCa or lesions on the cervix (Table 4). Regardless of their own HPV result, participants reported that a HPV-positive test is associated with increased risk of CxCa, which requires further evaluation and/or treatment. Participants also recognized that while HPV-negative result was reassuring, regular screening is still necessary since the infection could occur later. The concept of routine screening was compared to HIV testing by both WHIV and HIV-negative women.

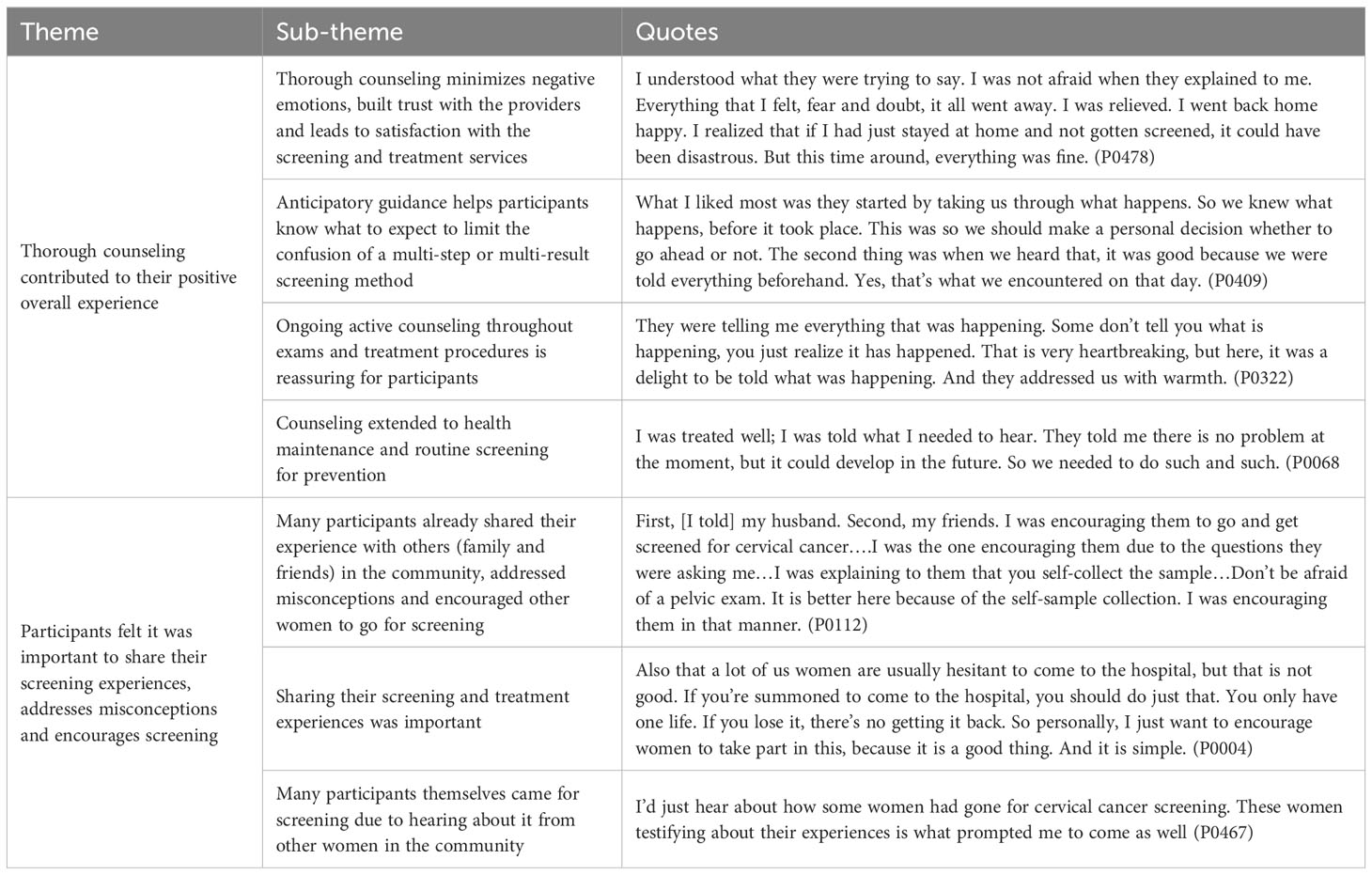

Table 4 Participants’ overall impression and major take away messages from the self-collection HPV-based screen-triage-and treat strategy.

Several participants who underwent VIA triage (Groups 2 and 3) reported negative experiences during pelvic exams (Table 3). Some reported discomfort related to the insertion and removal of the speculum, and others reported feeling embarrassed, especially when male providers were present. One participant did not like having to go for another test after the initial HPV self-collection. The discomfort and embarrassment were ameliorated by ongoing counseling during the exam process (Table 5). When thermal ablation was recommended, some participants reported having anxiety about the treatment procedure and others reported mild discomfort during treatment. However, overall, most expressed that thermal ablation itself was quick, painless, and well tolerated. Many participants who underwent treatment expressed gratitude for the treatment.

Table 5 Participants’ understanding of results and purpose of screening, triage and treatment steps stratified by HPV result.

Participants reported understanding that the purpose of VIA was to examine the cervix for “damage” caused by the virus or “lesions” that need treatment (Table 4). Even those who were HPV-negative and did not undergo VIA described VIA triage as a “confirmatory test,” to see if one has the disease or not. However, there was confusion in Group 2 about the significance of a positive screening test (HPV) with VIA-negative result. One participant expressed concern that the HPV will develop again if not treated, and others felt they still needed some kind of treatment for a positive HPV result, despite the VIA-negative result. One participant reported that the vinegar used in VIA was used to kill the HPV. The majority of Group 2 however viewed a negative VIA triage as an overall negative screening result and expressed relief.

All Group 3 participants understood that an HPV-positive/VIA-positive result meant that treatment was indicated. Many reported initial concerns when lesions were seen on exam, however, they also reported being counseled to not worry, as treatment was available right away (Table 5). Participants in this group predominantly expressed acceptance of the results and gratitude that they could proceed with immediate treatment. Participants who underwent treatment with thermal ablation correctly explained that the purpose was to treat lesions and prevent worsening of disease. Of note, we found no differences in understanding between WHIV and HIV-negative participants (Table 4).

Those who experienced symptoms after ablation viewed these as minor side effects (Table 3). The major post-treatment challenge participants reported was having to explain the need for several weeks of abstinence to their male partners. One participant reported that she did not know how to explain the treatment to her husband, as there was no medication that she could show him and felt the conversation would not go well. Other participants reported they were not able to abstain from sex due to the lack of male partner support. Some participants desired male partner counseling to be incorporated in the screen-and-treat program so that their husbands could understand and be supportive of abstinence recommendations. Some felt that same-day screen-and-treat did not allow them the opportunity to discuss treatment with their husbands before receiving it.

Many participants reported that after screening, they shared their experiences with others in their communities, including family, friends, and male partners (Table 3). Several participants reported answering questions from other women about screening and addressing misconceptions that kept women from presenting for CxCa screening. Almost all participants felt it was important to share their own experiences with the community and encourage screening uptake (Table 5).

The 25 participants of this study, including both WHIV and HIV-uninfected women, exhibited a higher baseline knowledge of CxCa and CxCa screening than reported in prior studies (18). Despite the introduction of several new factors and concept in our study’s screening algorithm – including HPV test, self-collection, a triage step and same-day treatment – participants reported accurate understanding of each step and an overall positive experience. The process of self-collection was highly acceptable, and participants demonstrated understanding and trust towards the HPV test result. Confusion did occur when the VIA result was discordant with the HPV result, indicating the need for additional targeted counseling in this group. Participants demonstrated confidence in their knowledge and expressed desire to share these experiences with their community so that other women are encouraged to attend screening. Counseling, and in particular anticipatory guidance, was key in helping participants understand complex screening procedures and results (Table 5).

Participants demonstrated a higher baseline knowledge of CxCa (e.g. association with sexual transmission, gynecological symptoms, infertility after treatment) and screening awareness (i.e. majority have heard of screening) than previously seen in Lilongwe district (19). This likely was due to recruitment of participants from clinics where women are already engaged in health care, compared to rural populations reached by mobile campaigns (20).

Notably, study participants displayed an understanding of the importance of screening for prevention. While fatalistic views of CxCa still existed (19, 21, 22), they were associated more with late diagnosis. In this study, screening was generally viewed positively and recognized as the way to find disease at a treatable stage and prevent fatal disease progression. Recent studies among women in southern Malawi also captured similar sentiment around the importance of early detection in CxCa screening (23). However, despite adequate knowledge of the disease and understanding of prevention, fears around pelvic exams (e.g. pain and embarrassment) hindered women from previously seeking out screening services; similar acceptability-related barriers have been identified in other studies from low- and middle-income countries (18).

Self-collection of vaginal samples for HPV testing was well-received and valued among our participants for ease of collection, avoidance of embarrassment or discomfort from speculum exams, and quick turnaround time of results. Many felt that self-collection could mitigate the fear and stigma surrounding speculum exams. These findings are consistent with existing literature over the last couple of decades that has shown self-collection to be acceptable across a variety of geographic locations, cultures and age groups (8, 9). Studies specific to African populations showed that women are willing to collect their own samples and that it is a more socially acceptable and feasible method than pelvic exam-based screening methods, such as Pap smear or VIA (24, 25).

Major concerns surrounding self-collection were worry about not collecting it correctly, fear of receiving a positive result, and fear that screening would reveal cancer. These are also well-documented concerns in studies on self-collection HPV testing (26, 27) and have been identified as barriers to screening (28). Factors mitigating these concerns, reported by our participants, were anticipatory guidance of what came next after each step of the screening process, quick results, and availability of same-day treatment. Knowing what to expect with a positive result, and knowing there is treatment right away if the result was positive, were identified as two reassuring factors by participants.

VIA has been the primary screening method, followed by cryotherapy in Malawi’s screen-and-treat national strategy for CxCa prevention (12). In our study screening algorithm, several concepts including HPV screening, self-collection of vaginal samples, and thermal ablation treatment were new. Additionally, none of the participants (except one) had heard of HPV or its association with CxCa. A large part of the initial recruitment and consent process for the parent study was spent on explaining the relationship between HPV, cervical dysplasia, and CxCa. When this understanding was assessed though IDIs weeks or even months after screening, most participants accurately described that HPV is a virus that causes cervical lesions, and if untreated, can lead to CxCa. This likely is evidence of successful pre-enrollment education, but also suggests that perhaps participants were already familiar with the concept of a virus causing significant illness (e.g., HIV). Exposure to HIV knowledge could have helped make new disease concepts more understandable. Participants engaged in HIV care may have greater knowledge in this area, but in our study, both WHIV and HIV-negative participants displayed good understanding of HPV (Table 4).

HPV testing has been shown to be difficult to comprehend for women more accustomed to pelvic exams for screening, with the main challenge being failure to understand why a positive HPV test may not lead to immediate treatment (14, 15). We found similar sentiments among three (of twelve) HPV-positive/VIA-negative participants (Table 4). Thematic saturation was reached later with this group due to the variability in understanding. A major hinderance in understanding HPV screening results identified in literature is that patients do not feel that healthcare professionals provide sufficient or understandable information during results delivery (14). When confusion was identified through IDIs, the clinic study staff increased anticipatory guidance of what to except with the VIA triage step and emphasized counseling for those with discordant results so that patients understood why they did not need treatment. The IDIs that occurred after increased counseling efforts revealed less confusion among participants (data not shown).

Ongoing counseling throughout the screening process and anticipatory guidance on what to expect with varying outcomes were key in creating a positive screening experience. Proper counseling leads to understanding, which can increase acceptability, uptake and adherence to routine screening. Counseling can also lead to trust with the healthcare team and mitigates negative psychological effects such as worry and fear, which are well identified barriers to accessing preventative care (29).

Anticipatory guidance was especially helpful in this multi-step screening process. Participants specifically described how knowing what to expect at each step of screening and anticipating what came next after each outcome was helpful in minimizing confusion and reducing negative emotions (Table 5). Anticipatory guidance is most practiced in pediatrics to prepare parents on the expected growth and development of their children (30), but not readily employed in cancer screening. Anticipatory guidance is also naturally present through the informed consent process of research, where each step of the study after each potential outcome is clearly reviewed, and the understanding of participants is assessed. While time can be a limitation in real-world cancer screening programs, our study suggests that the time spent on anticipatory guidance, especially if it involves a multi-step screening process, is invaluable for women to prepare for the emotional challenges of CxCa screening.

Thermal ablation was well tolerated by the six participants who underwent treatment. Consistent with prior studies, post-treatment side-effects were minimal and most expressed gratitude for being able to receive treatment right away (13, 31). The major challenge reported was difficulty communicating with their male partners at home. Participants felt that because a period of sexual abstinence was recommended post-treatment, they had to inform their male partners of the procedure, which could lead to misunderstandings, conflicts, and for many, inability to comply with post-treatment abstinence. We saw similar challenges in our prior VIA and thermal ablation study (32) that identified male partners as a barrier to returning for follow-up. However, the prior study also identified male partners as a potential source of support in CxCa screening. Including male partners counseling in screen-and-treat services may be vital for women’s safety and acceptance, especially when treatment is indicated.

This study was successful in reaching and unscreened women. However, being facility-based resulted in a selection of women with access to care. Familiarity with the health system and exposure to health concepts can favorably skew acceptability of the screening procedures. Perspectives from women in rural, hard-to-reach areas need to be considered for successful expansion of this strategy. Notably, a recent study in Malawi that implemented community-based self-collection for HPV screening found that it increased screening uptake (compared to facility-based screening alone) and was acceptable to both clients and health workers (33–35). A strength of this study is that we included both WHIV and HIV-uninfected women and found no differences in their ability to understand results or perspectives on screening steps. Timing of our IDIs weeks to months after screening allowed us to cover topics such as how women had shared their experiences with their community and barriers faced in remaining abstinent for the recommended period following thermal ablation. On the other hand, the delay between the experience and the IDI could have resulted in some recall bias.

HPV-based screen-and-treat experiences through a research study may differ from real-world clinical settings where providers have higher volumes of patients with more limited staffing and resources. For example, good counseling was overwhelmingly identified as being valued by participants in our study, but time may be more constrained in actual clinical practice, limiting provider time to thoroughly counsel patients about potentially confusing results. In addition, our study utilized additional procedures that would not be routinely implemented in non-study settings, such as colposcopy, Pap smear, and/or biopsy, which could have confounded participant’s experiences. However, most patients did not mention the additional procedures, and it did not seem to negatively affect their experiences.

Self-collection HPV primary screening is a promising method to expand CxCa screening access and increase cervical precancer detection (5, 6). However, the lower specificity of the HPV assay requires a triage test for HPV-positive results to prevent overtreatment (36). As HPV-based multi-step screening is being implemented, our findings provide rich insight for healthcare providers and policymakers surrounding women’s experiences undergoing a same-day HPV-based screen-triage-treat algorithm. We captured what was important to women: convenience of self-collection, quick result turnaround, availability of same-day treatment, and thorough counseling. HPV self-collection can overcome barriers to pelvic exams including discomfort, embarrassment and need for trained providers. While a multi-step screening process with VIA triage can lead to confusion about required follow-up procedures, proper counseling and anticipatory guidance can improve understanding. Incorporating thorough counseling in CxCa screening programs can change women’s perspective of screening, build trust with healthcare systems, and influence healthcare seeking behavior towards routine screening and prevention.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Malawi National Health Sciences Research Committee, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institution Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

FL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WD: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MN: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. LM: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. VM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA [grant number: NIH R21CA236770], UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Tier 2 Stimulus Award, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, Tier 2 Stimulus Award, and U.S. Agency for International Development, Washington, DC, USA [grant number: AID-OAA-A-11-00012]. The study funders were not involved in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. U.S. National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA [grant number: UM1CA121947].

We would like to thank study participants, study staff, UNC Project-Malawi Community Advisory Board, the Lilongwe District Health Management Team, and the Malawi Ministry of Health Reproductive Health Directorate for their support.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, et al. No Title Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today 2020. Available at: https://gco.iarc.fr/today.

2. UNAIDS. Country factsheets Malawi 2022 HIV and AIDS estimates . Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/malawi.

3. Msyamboza KP, Phiri T, Sichali W, Kwenda W, Kachale F. Cervical cancer screening uptake and challenges in Malawi from 2011 to 2015: retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health (2016) 16(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3530-y

4. Maseko FC, Chirwa ML, Muula AS. Health systems challenges in cervical cancer prevention program in Malawi. Global Health action (2015) 8(1):26282. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.26282

5. Magdi R, Elshafeey F, Elshebiny M, Kamel M, Abuelnaga Y, Ghonim M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy of HPV tests for the screening of cervical cancer in low-resource settings. Int J gynaecol obstet (2021) 152(1):12–8. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13455

6. Web Annex A. WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

7. Arrossi S, Thouyaret L, Herrero R, Campanera A, Magdaleno A, Cuberli M, et al. Effect of self-collection of HPV DNA offered by community health workers at home visits on uptake of screening for cervical cancer (the EMA study): a population-based cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Global Health (2015) 3(2):e85–94. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70354-7

8. Serrano B, Ibáñez R, Robles C, Peremiquel-Trillas P, de Sanjosé S, Bruni L. Worldwide use of HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening. Prev Med (2022) 154:106900. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106900

9. Dzobo M, Dzinamarira T, Maluleke K, Jaya ZN, Kgarosi K, Mashamba-Thompson TP. Mapping evidence on the acceptability of human papillomavirus self-sampling for cervical cancer screening among women in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. BMJ Open (2023) 13(4):e062090. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062090

10. Randall TC, Sauvaget C, Muwonge R, Trimble EL, Jeronimo J. Worthy of further consideration: an updated meta-analysis to address the feasibility, acceptability, safety and efficacy of thermal ablation in the treatment of cervical cancer precursor lesions. Prev Med (2019) 118:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.10.006

11. Kunckler M, Schumacher F, Kenfack B, Catarino R, Viviano M, Tincho E, et al. Cervical cancer screening in a low-resource setting: a pilot study on an HPV-based screen-and-treat approach. Cancer Med (2017) 6(7):1752–61. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1089

12. Malawi Ministry of Health. National CxCa prevention program strategy. Lilongwe, Malawi (2016). Available at: https://malawi.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/National_Cervical_Cancer_Strategy_A5_30Oct17_WEB.pdf.

13. Chinula L, McGue S, Smith JS, Saidi F, Mkochi T, Msowoya L, et al. A novel cervical cancer screen-triage-treat demonstration project with HPV self-testing and thermal ablation for women in Malawi: protocol for a single-arm prospective trial. Contemp Clin Trials Commun (2022) 26:100903. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2022.100903

14. McBride E, Tatar O, Rosberger Z, Rockliffe L, Marlow LA, Moss-Morris R, et al. Emotional response to testing positive for human papillomavirus at cervical cancer screening: a mixed method systematic review with meta-analysis. Health Psychol review (2021) 15(3):395–429. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2020.1762106

15. O’Connor M, Costello L, Murphy J, Prendiville W, Martin CM, O’Leary JJ, et al. Influences on human papillomavirus (HPV)-related information needs among women having HPV tests for follow-up of abnormal cervical cytology. J Family Plann Reprod Health Care (2015) 41(2):134–41. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2013-100750

16. Bansil P, Wittet S, Lim JL, Winkler JL, Paul P, Jeronimo J. Acceptability of self-collection sampling for HPV-DNA testing in low-resource settings: a mixed methods approach. BMC Public Health (2014) 14(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-596

17. Mao C, Kulasingam SL, Whitham HK, Hawes SE, Lin J, Kiviat NB. Clinician and patient acceptability of self-collected human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening. J Women’s Health (2017) 26(6):609–15. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5965

18. Islam RM, Billah B, Hossain MN, Oldroyd J. Barriers to cervical cancer and breast cancer screening uptake in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Asian Pacific J Cancer prevent: APJCP. (2017) 18(7):1751. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.7.1751

19. Bula AK, Lee F, Chapola J, Mapanje C, Tsidya M, Thom A, et al. Perceptions of cervical cancer and motivation for screening among women in Rural Lilongwe, Malawi: A qualitative study. PloS One (2022) 17(2):e0262590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262590

20. Chinula L, Topazian HM, Mapanje C, Varela A, Chapola J, Limarzi L, et al. Uptake and safety of community-based “screen-and-treat” with thermal ablation preventive therapy for cervical cancer prevention in rural Lilongwe, Malawi. Int J cancer (2021) 149(2):371–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33549

21. McFarland DM, Gueldner SM, Mogobe KD. Integrated review of barriers to cervical cancer screening in sub-Saharan Africa. J Nurs Scholarship (2016) 48(5):490–8. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12232

22. Ginjupalli R, Mundaden R, Choi Y, Herfel E, Oketch SY, Watt MH, et al. Developing a framework to describe stigma related to cervical cancer and HPV in western Kenya. BMC Women’s Health (2022) 22(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01619-y

23. Carvalho MME. Shaping service delivery for cervical cancer screening: Understanding knowledge, acceptability and preferences among women in the Neno district of Malawi. Public Health Theses (2016), 1036. Available at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ysphtdl/1036.

24. Podolak I, Kisia C, Omosa-Manyonyi G, Cosby J. Using a multimethod approach to develop implementation strategies for a cervical self-sampling program in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res (2017) 17(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2160-0

25. Rositch AF, Gatuguta A, Choi RY, Guthrie BL, Mackelprang RD, Bosire R, et al. Knowledge and acceptability of pap smears, self-sampling and HPV vaccination among adult women in Kenya. PloS One (2012) 7(7):e40766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040766

26. Racey CS, Withrow DR, Gesink D. Self-collected HPV testing improves participation in cervical cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Public Health (2013) 104:e159–66. doi: 10.1007/BF03405681

27. Camara H, Zhang Y, Lafferty L, Vallely AJ, Guy R, Kelly-Hanku A. Self-collection for HPV-based cervical screening: a qualitative evidence meta-synthesis. BMC Public Health (2021) 21(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11554-6

28. Ackerson K, Preston SD. A decision theory perspective on why women do or do not decide to have cancer screening: systematic review. J adv nursing (2009) 65(6):1130–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.04981.x

29. Vasudevan L, Stinnett S, Mizelle C, Melgar K, Makarushka C, Pieters M, et al. Barriers to the uptake of cervical cancer services and attitudes towards adopting new interventions in Peru. Prev Med Rep (2020) 20:101212. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101212

30. Reisinger KS, Bires JA. Anticipatory guidance in pediatric practice. Pediatrics (1980) 66(6):889–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.66.6.889

31. Lee F, Bula A, Chapola J, Mapanje C, Phiri B, Kamtuwange N, et al. Women’s experiences in a community-based screen-and-treat cervical cancer prevention program in rural Malawi: a qualitative study. BMC cancer (2021) 21(1):428. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08109-8

32. Chapola J, Lee F, Bula A, Mapanje C, Phiri BR, Kamtuwange N. Barriers to follow-up after an abnormal cervical cancer screening result and the role of male partners: a qualitative study. BMJ Open (2021) 11(9):e049901. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049901

33. Tang JH, Lee F, Chagomerana MB, Ghambi K, Mhango P, Msowoya L, et al. Results from two HPV-based cervical cancer screening-family planning integration models in Malawi: A cluster randomized trial. Cancers (2023) 15(10):2797. doi: 10.3390/cancers15102797

34. Bula AK, Mhango P, Tsidya M, Chimwaza W, Kayira P, Chinula L, et al. Client perspectives on integrating facility and community-based HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening with family planning in Malawi, 2020-2021: a qualitative study, in: Presented at the International Papillomavirus Conference in Washington, DC, April 17-21, 2023.

35. Mhango P, Kandeya B, Chinula L, Tang JH, Kumitawa A, Chimwaza W, et al. Acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of integrating HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening into voluntary family planning services in Malawi, in: Presented at the International Papillomavirus Conference in Washington, DC, , April 17-21, 2023.

36. Zhao F-H, Lin MJ, Chen F, Hu SY, Zhang R, Belinson JL, et al. Performance of high-risk human papillomavirus DNA testing asa primary screen for cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from 17population-based studies from China. Lancet Oncol (2010) 11:1160–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70256-4

Keywords: HPV self-collection, VIA triage, thermal ablation, cervical cancer screening experience, Malawi (MeSH [Z01.058.290.175.500])

Citation: Lee F, McGue S, Chapola J, Dunda W, Tang JH, Ndovie M, Msowoya L, Mwapasa V, Smith JS and Chinula L (2024) Experiences of women participating in a human papillomavirus-based screen-triage-and treat strategy for cervical cancer prevention in Malawi. Front. Oncol. 14:1356654. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1356654

Received: 15 December 2023; Accepted: 26 January 2024;

Published: 27 February 2024.

Edited by:

Manoj Menon, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Olugbenga Akindele Silas, University of Jos, NigeriaCopyright © 2024 Lee, McGue, Chapola, Dunda, Tang, Ndovie, Msowoya, Mwapasa, Smith and Chinula. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fan Lee, RmFuLmxlZUBqZWZmZXJzb24uZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.