95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 25 April 2024

Sec. Gastrointestinal Cancers: Gastric and Esophageal Cancers

Volume 14 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1336859

Hong Zhao1,2,3†

Hong Zhao1,2,3† Chenan Liu1,2,3†

Chenan Liu1,2,3† Guotian Ruan1,2,3†

Guotian Ruan1,2,3† Xin Zheng1,2,3

Xin Zheng1,2,3 Yue Chen1,2,3

Yue Chen1,2,3 Shiqi Lin1,2,3

Shiqi Lin1,2,3 Xiaoyue Liu1,2,3

Xiaoyue Liu1,2,3 Jinyu Shi1,2,3

Jinyu Shi1,2,3 Xiangrui Li1,2,3

Xiangrui Li1,2,3 Shuqun Li1,2,3

Shuqun Li1,2,3 Hanping Shi1,2,3*

Hanping Shi1,2,3*Introduction: Malnutrition is prevalent among individuals with gastric cancer and notably decreases their quality of life (QOL). However, the factors impacting QOL are yet to be clearly defined. This study aimed to identify essential factors impacting QOL in malnourished patients suffering from gastric cancer.

Methods: By using the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) to assess the nutritional status (≥4 defined malnutrition) of hospitalized cancer patients, 4,586 gastric cancer patients were ultimately defined as malnourished. Spearman method was used to calculate the relationship between clinical features and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30). Then, univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to observe which factors affected QOL, and subgroup analysis was performed in young and old population respectively. In addition, we used univariate and multivariate logistic regression to explore whether and how self-reported frequent symptoms in the last 2 weeks of the PG-SGA score affected QOL.

Results: In multivariate logistic regression analysis of clinical features of patients with malnourished gastric cancer, women, stage II, stage IV, WL had an independent correlation with a low global QOL scores. However, BMI, secondary education, higher education, surgery, chemotherapy, HGS had an independent correlation with a high global QOL scores. In multivariate logistic regression analysis of symptoms in self-reported PG-SGA scores in patients with malnourished gastric cancer, having no problem eating had an independent correlation with a high global QOL scores. However, they have no appetite, nausea, vomiting, constipation and pain had an independent correlation with a lower global QOL scores. The p values of the above statistical results are both < 0.05.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that QOL in malnourished patients with gastric cancer is determined by female sex, stage II, stage IV, BMI, secondary and higher education or above, surgery, chemotherapy, WL, and HGS. Patients’ self-reported symptoms of nearly 2 weeks, obtained by using PG-SGA, are also further predictive of malnourished gastric cancer patients. Detecting preliminary indicators of low QOL could aid in identifying patients who might benefit from an early referral to palliative care and assisted nursing.

Despite variations in incidence and mortality rates across different regions, gastric cancer is the fifth most commonly detected cancer worldwide and the fourth most common cause of death due to cancer (1). In China, it is the second leading cause of death related to cancer (2). The incidence and progression of this disease is determined by an interplay of environmental and genetic factors, indicating that gastric cancer is multifactorial in nature (3). Currently, the management of gastric cancer is far from optimal, given that patients, irrespective of their disease subtype, generally receive uniform treatment (4). Recently, there has been a shift in discussion and decision-making about cancer care, especially when considering patient selection, from a variety of clinical outcomes to patient-centered outcomes such as QOL (5). There has also been a significant evolution in palliative care and treatment approaches, where the objective is to unify life-extending treatments with patient QOL (4, 6–11). Although new therapies and technologies can improve treatment outcomes in cancer patients, it is of equal importance to maintain physical and emotional health by assessing QOL (12, 13), which is negatively affected by cancer (14). Patients with late-stage or uncontrollable gastric cancer constantly experience malnutrition, which affects their QOL, increases the chemotherapy toxicity and reduces the overall survival rate (15, 16). Despite the widespread prevalence of gastric cancer worldwide, our knowledge about its effect on QOL is still limited (17). The goal of this research is to assess the factors impacting the QOL of malnourished patients with gastric cancer. The findings of this study will enhance care strategies and management of patients, and offer vital references for future clinical practice and research.

The INSCOC is a nationwide survey exploring the link between nutritional health and clinical results in patients suffering from malignant tumors. This project was both conceived and put into action by the Tumor Nutrition and Support Professional Committee within the Chinese Cancer Society. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the reviewing bodies of all participating institutions, with all participants giving their informed written consent. The criteria for participation in this study were as follows:

1. Individuals aged 18 to 90 years with full mental capacity, no communication issues, and capable of participating in the necessary examinations.

2. Histological diagnosis of gastric cancer.

3. Experienced multiple hospitalizations for the same condition.

4. Comprehensive documentation of medical history and any subsequent data.

5. Able to voluntarily participate.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

1. Patients with HIV/AIDS or organ transplant recipients.

2. Patients in critical condition or difficult to evaluate.

3. Patients who refuse or do not cooperate with the survey questionnaire.

We use Investigation on Nutrition Status and Clinical Outcome of Common Cancers (INSCOC) data screened 5,845 eligible adult patients with gastric cancer from 26 provinces and municipalities in China between 2012 and 2022. Professional staff used a standardized questionnaire and professional measurement methods to collect information on sex, age, TNM stage, body mass index (BMI) (18), the rate of weight loss over one month (WL), hand grip strength (HGS),occupation, education level, residence, and treatment within the initial 48 hours of hospital admission. Missing data is interpolated using R software (Supplementary Figure 1). By Asian standards, HGS is classified as low grip strength (HGS<18 for Female; HGS<28 for Male) and high grip strength (HGS≥18 for Female; HGS≥28 for Male) (19). Occupations are divided into mental work, manual work and retired or other. Mental work includes professional or managerial personnel, civil servants, teachers, career and enterprise staff. Manual work includes farmers and workers. The level of education is divided into higher education (college, bachelor’s, master’s and above), secondary education (middle and high school) or no education and primary education. Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) (20) are obtained by the investigators in the form of filling in questionnaires after the patients understand the questions and explain the questions. In this way, the errors caused by the patients’ unclear understanding can be avoided to the maximum extent. The PG-SGA score is recognized by the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) as the benchmark nutritional assessment tool for cancer patients. The PG-SGA score is composed of patient self-assessment and a comprehensive assessment by the health care provider and is not a short form of nutritional risk screening. The PGSGA score is 0-1 (no intervention is required at this time, and routine follow-up and evaluation are maintained during treatment). The PG-SGA score is 2-3 (patient or patient family education by a dietitian, nurse, or physician, and medical intervention may be performed based on the presence of symptoms and the results of laboratory tests). The PG-SGA score of 4-8 (intervention by a dietitian and, depending on the severity of symptoms, in conjunction with a physician and caregiver). The PG-SGA score≥9 (urgent need for symptom improvement and/or concurrent nutritional intervention). In this study, PG-SGA≥4 was defined as malnutrition, and the higher the score, the more severe the malnutrition, on the contrary, the lower the score, the better the nutritional status. QOL was assessed using the EORTC QLQC30, which evaluates 5 functional scores (physical function, role function, emotional function, congnitive function, social function), global health, 3 symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain), 6 individual measures (dyspnea, sleep disturbance, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, financial difficulties). The computation of each domain’s summary QOL score (0-100) adhered to the EORTC QLQ-C30 formulas. Higher scores on the functional and global health status scales indicate improved functioning. Conversely, Symptom scales and individual measurement items use negative scores, with higher scores indicating greater intensity. The total score of the QOL is added by each functional score, then added to 800 minus 3 symptom scores and 5 individual measures (except financial difficulties), and finally 13 (21).

We employed a multiple imputation chain-equation method to impute missing data, assuming that the missingness was random. Predictive mean matching was used to impute missing continuous variables, while a logistic regression model was used for imputing missing binary variables. Through 100 iterations, we generated five imputed datasets and analyzed each separately. Finally, we combined the results using Rubin’s method. The data is presented as a simple percentage or median interquartile range (IQR). The correlation between clinical features of patients with malnourished gastric cancer and EORTC QLQ-C30 was calculated by the spearman method. The greater the absolute value of the correlation coefficient calculated by the spearman method, the stronger the correlation was. Then the OR is calculated by univariable and multivariable logistic regression. The OR>1 indicates that it is a predictor of outcome events (low global QOL scores, low physical function scores, high fatigue scores, high appetite loss scores). The OR<1 indicates that it is a predictor of outcome events (high global QOL scores, high physical function scores, low fatigue scores, low appetite loss scores). The above scores are compared with the average. If in univariate and multivariate logistic regression, p values are both <0.05, indicating that this factor can independently affect outcome events. R software, version 4.3.0, was used for all analytical procedures.

The baseline characteristics of 5845 gastric cancer patients were shown in supplementary Table 1, of which 4586 (78.5%) were malnourished. In Table 1, we observed the baseline characteristics of 4586 malnourished patients with gastric cancer, 3149 men (68.7%) and 1437 women (31.3%). the median age was 60 years old, IQR (52.00, 67.00). Of the total number of patients, 546 patients in stage I (11.9%); 884 patients in stage II (19.3%); 1813 patients in stage III (39.5%), and 1,343 patients in stage IV (29.3%). The median BMI was 20.57 (IQR 18.44, 22.96). Less than half of patients were treated with surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy. More than half of the patients with gastric cancer experienced WL (69.1%). There were 2358 (51.4%) people with low HGS and 2228 (48.6%) people with high HGS. 1720 (37.5%) of the study population had primary education or no education, 2259 (49.3%) had secondary education, and 607 (13.2%) had higher education. The proportion of patients living in urban and rural areas is similar.

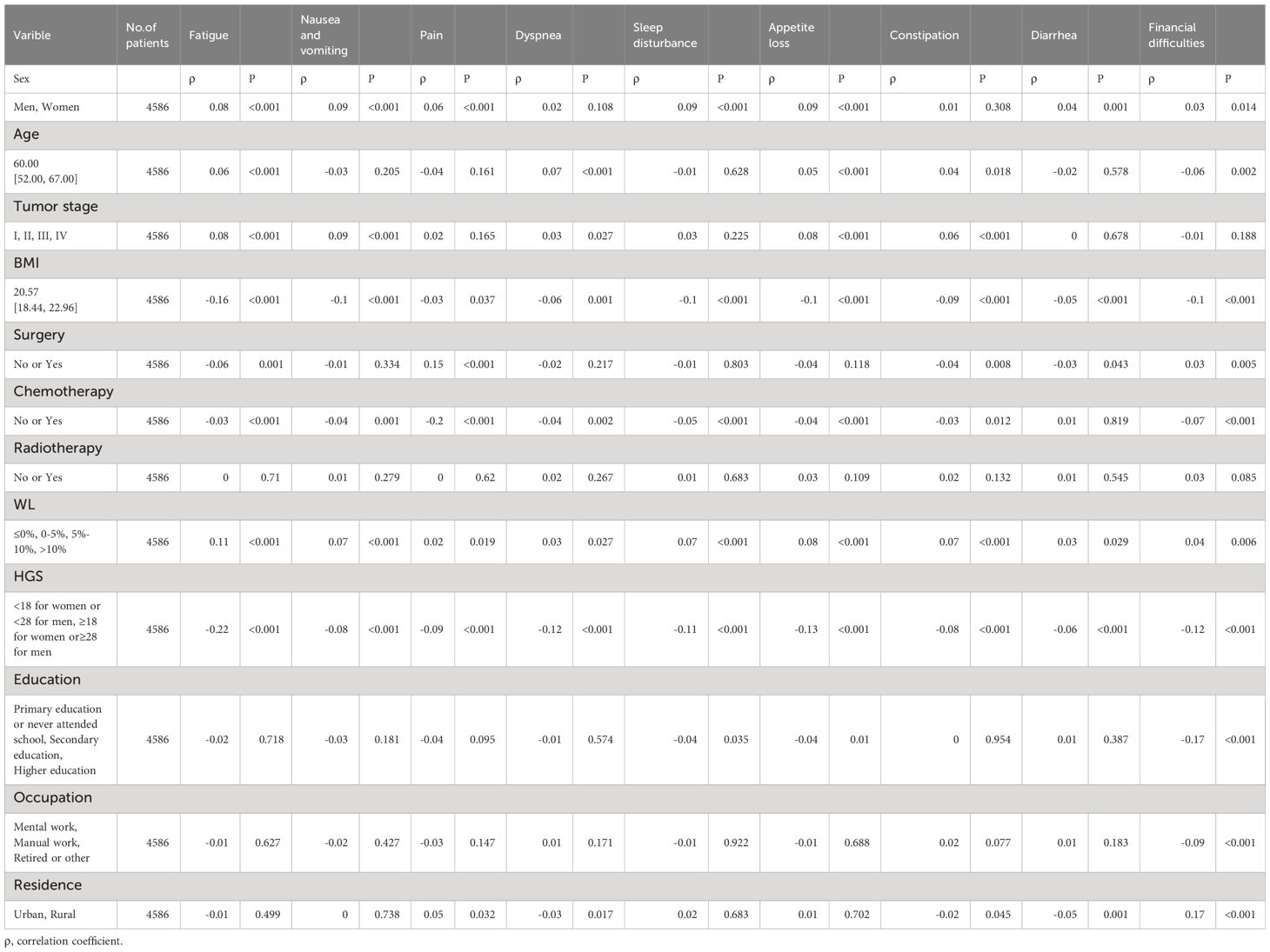

Female (ρ-0.11), age (ρ-0.05), tumor stage (ρ-0.08) and WL (ρ-0.1) were negatively correlated with the global QOL score. BMI (ρ0.16), surgery (ρ0.04), chemotherapy (ρ0.07), HGS (ρ0.24) and education (ρ0.06) were positively correlated with the global score of QOL (Tables 2, 3).

Table 3 Relation Between Clinical and Nutritiona Parameters With European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Symptom Scales.

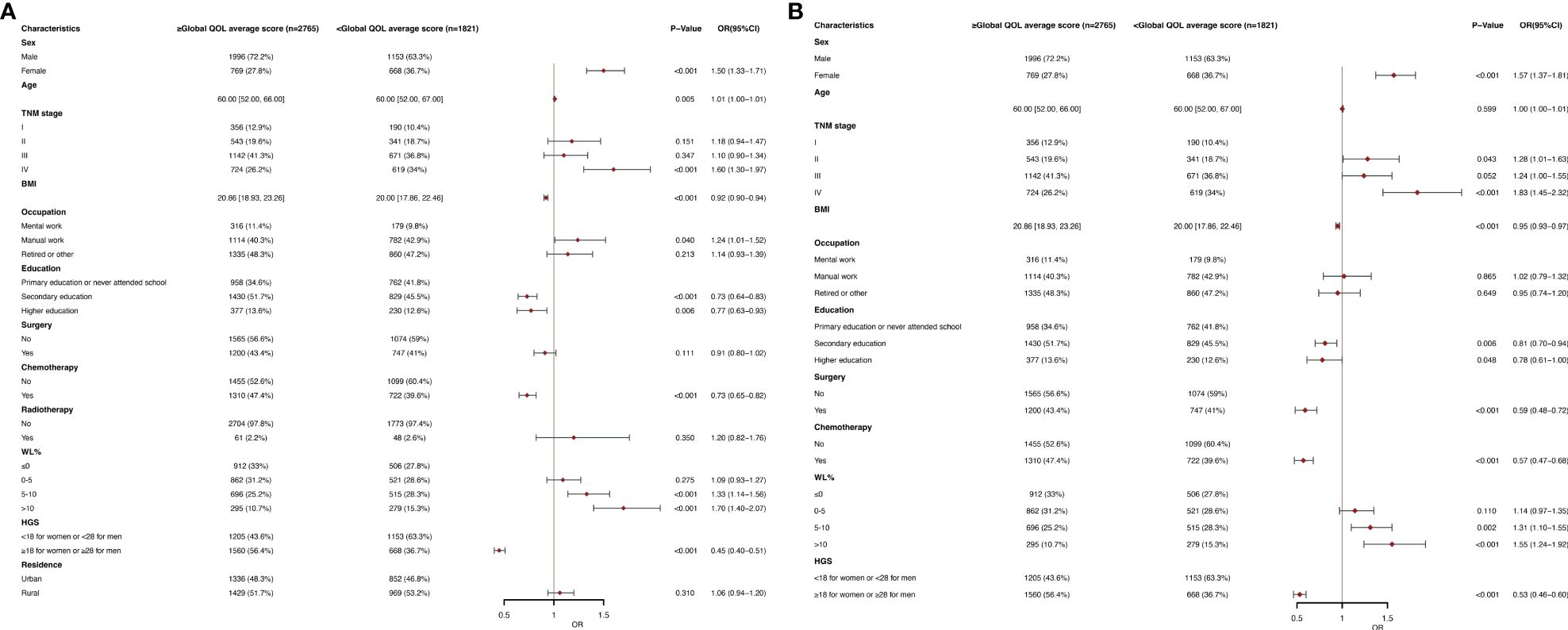

The global QOL scores was segmented based on the mean score (82.83) in the univariable and multivariate logistic regression analysis (Figures 1A, B). Female sex (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.37-1.81; P<0.001), stage II (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.01-1.63; P =0.043), stage IV (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.45-2.32; P<0.001) and WL (WL 5-10%: OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.10-1.55; P =0.002; WL>10%: OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.24-1.92; P<0.001) were an independent predictor of a lower global QOL scores (<82.83). BMI (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.93-0.97; P<0.001), secondary education (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.70-0.94; P =0.006), higher education (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.61-1.00; P =0.048), surgery (OR, 0.59; CI, 0.48-0.72; P < 0.001), chemotherapy (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.68;P<0.001) and high HGS (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.46-0.60; P< 0.001) were an independent predictor of higher global QOL scores (≥82.83). The study population was divided into young group (<65) and elderly group (≥65), and subgroup analysis was performed. We found that in the elderly population, the age (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05; P =0.008) was an independent predictor of low global QOL scores, and other results were similar to those of the total population analysis (Supplementary Table 3B). In the young age group, the results obtained are similar to the results of the general population analysis (Supplementary Table 3A).

Figure 1 (A) Clinical and Nutritional Parameters Related to Poor Global QOL average score (Below the Mean of <82.83) According to Univariable Logistic Regression Analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; The summary statistics present N% for categorical variables and median [IQR] deviation for continuous variables. (B) Clinical and Nutritional Parameters Related to Poor Global QOL average score (Below the Mean of <82.83) According to Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; The summary statistics present N% for categorical variables and median [IQR] deviation for continuous variables. .

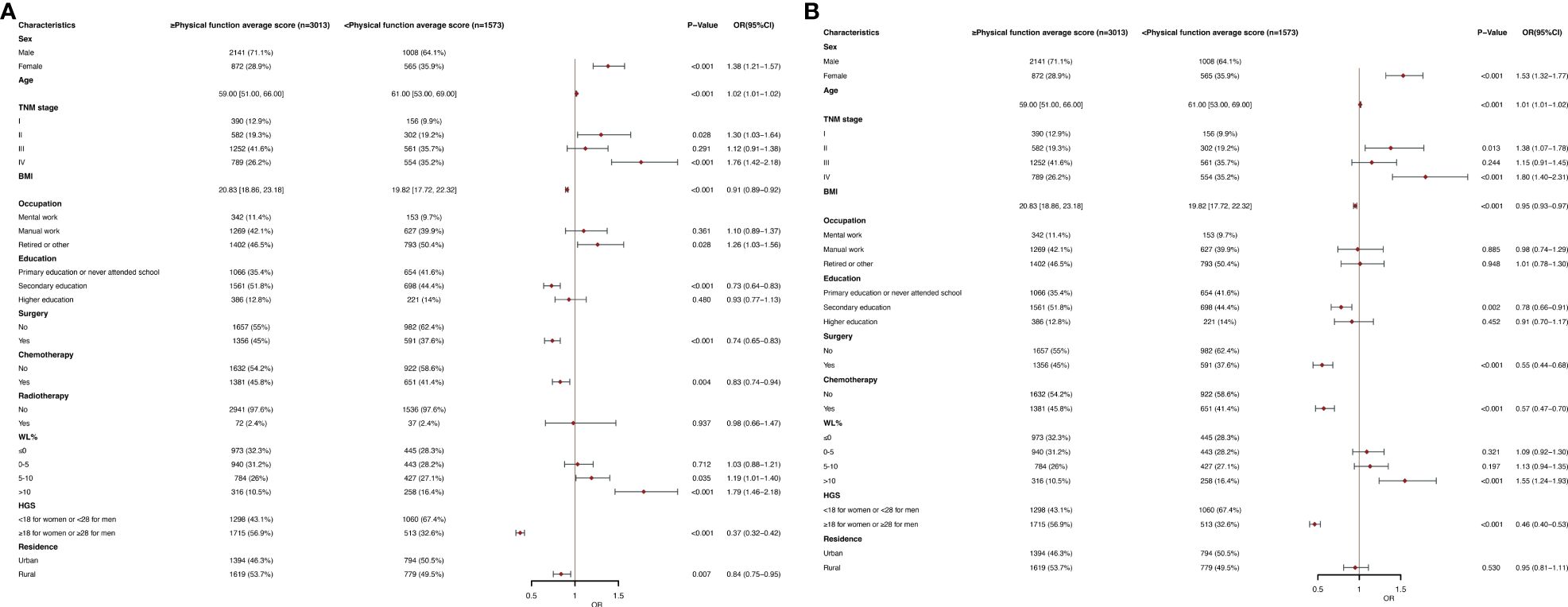

Figures 2A, B show the physical function in The EORTC QLQC30 score divided by an average score (78.67). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, women (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.32-1.77; P< 0.001), age (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.01-1.02; P <0.001), stage II (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.07-1.78; P =0.013), stage IV (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.40-2.31; P <0.001) and WL >10 (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.24-1.93; P <0.001) were associated with poor physical function (< 78.67) of independent predictors. BMI (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.93-0.97; P <0.001), secondary school (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.66-0.91; p=0.002), surgery (OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.44-0.68; p<0.001), chemotherapy (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.70; p<0.001) and high HGS(OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.40-0.53; p<0.001) were an independent predictor of better physical function (≥78.67). In a subgroup analysis of age, in the younger age group, results were obtained that were similar to the general population (Supplementary Table 4A). In the elderly population, the age (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.09; p<0.001) became an independent predictor of lower physical function scores (Supplementary Table 4B).

Figure 2 (A) Clinical and Nutritional Parameters Related to Poor Physical function average score (Below the Mean of <78.67) According to Univariable Logistic Regression Analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; The summary statistics present N% for categorical variables and median [IQR] deviation for continuous variables. (B) Clinical and Nutritional Parameters Related to Poor Physical function average score (Below the Mean of <78.67) According to Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; The summary statistics present N% for categorical variables and median [IQR] deviation for continuous variables.

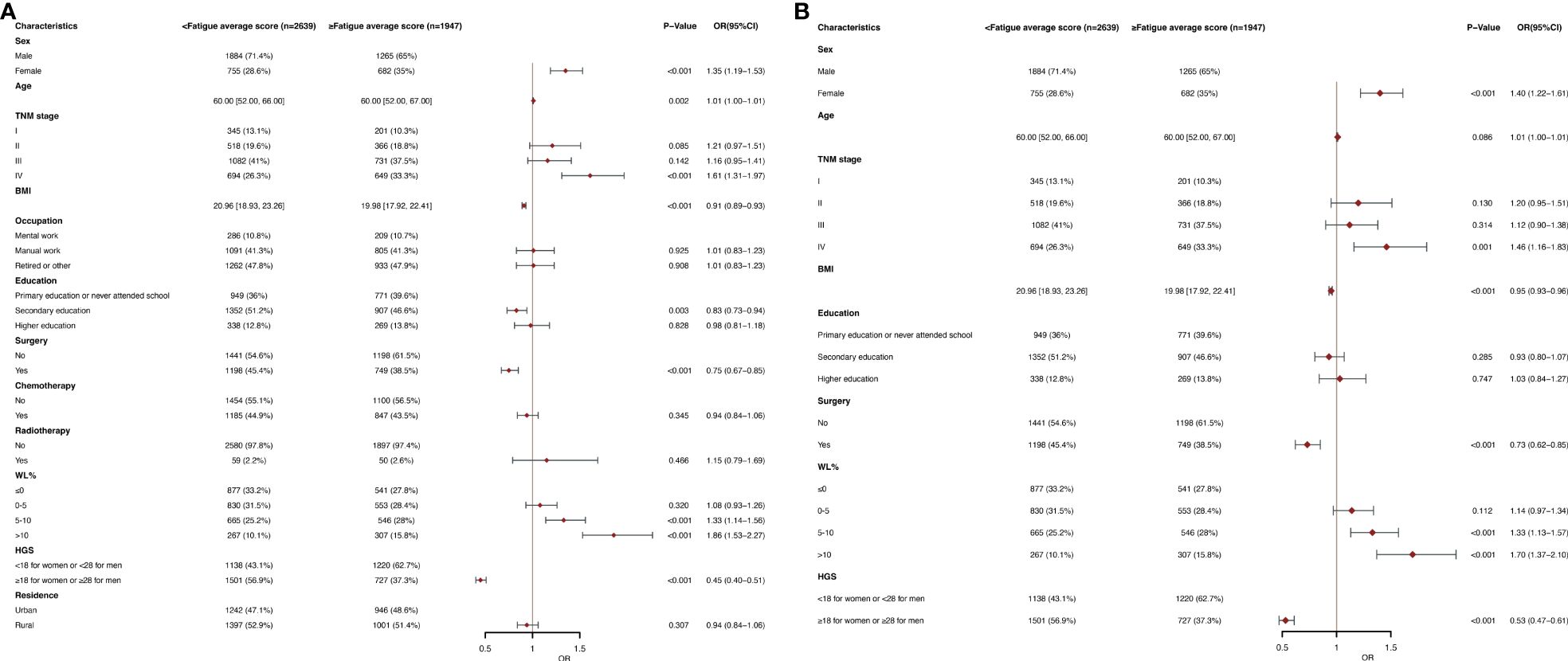

Figures 3A, B show the fatigue in The EORTC QLQC30 score divided by an average score (24.15). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, women (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.22-1.61; p<0.001), stage IV (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.16-1.83; P =0.001) and WL of 5-10 (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.13-1.57; p<0.001), WL of >10 (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.37-2.10; p<0.001) were an independent predictor of higher fatigue scores (≥24.15). BMI (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.93-0.96; p<0.001), surgery (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.62-0.85; p<0.001), and high HGS (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.47-0.61; p<0.001) were a low fatigue scores (<24.15) of independent predictors. In subgroup analysis, in the elderly population, the age (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05; p=0.007) was an independent predictor of higher fatigue scores, and other observations were similar (Supplementary Table 5B). Results were observed in younger age groups similar to the general population (Supplementary Table 5A).

Figure 3 (A) Clinical and Nutritional Parameters Related to Increased Fatigue average score (Above the Mean of >24.15) According to Univariable Logistic Regression Analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; The summary statistics present N% for categorical variables and median [IQR] deviation for continuous variables. (B) Clinical and Nutritional Parameters Related to Increased Fatigue average score (Above the Mean of >24.15) According to Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; The summary statistics present N% for categorical variables and median [IQR] deviation for continuous variables.

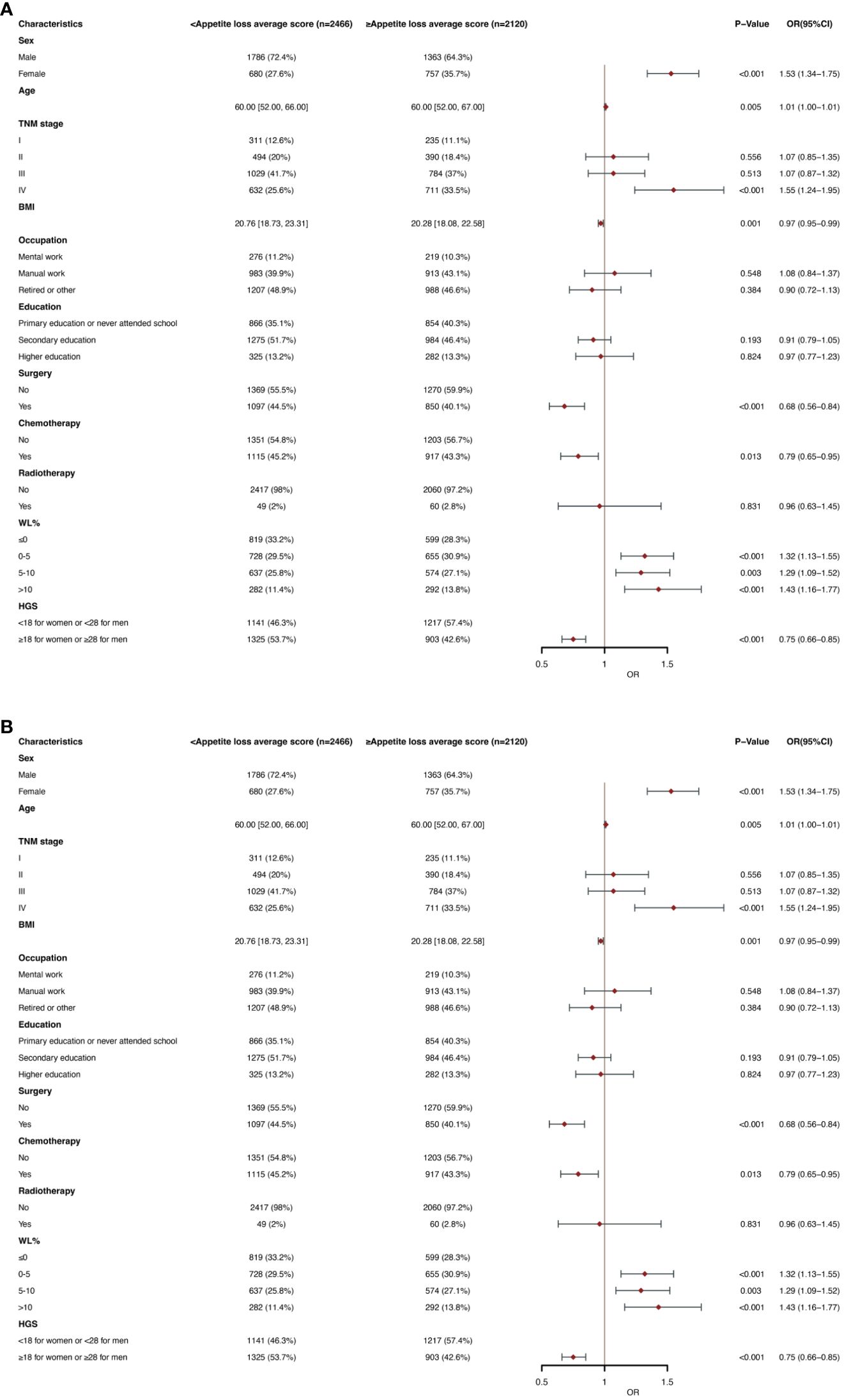

Figures 4A, B show that appetite loss in the EORTC QLQC30 score was divided by mean score (21.56). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, female (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.34-1.75; p< 0.001), age (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00-1.01; p=0.005), stage IV (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.24-1.95; P < 0.001), WL of 0-5 (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.13-1.55; P<0.001), WL of 5-10 (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.09-1.52; P =0.003) and WL >10 (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.16-1.77; P < 0.001) were an independent predictor of higher appetite loss scores (≥21.56). BMI (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.95-0.99; P =0.001), surgery (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56-0.84; P< 0.001), chemotherapy (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65-0.95; P =0.013) and high HGS (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.66-0.85; P <0.001) were a lower appetite loss scores (< 21.56) of independent predictors. In the subgroup analysis of age, similar results were obtained in the older and younger groups, respectively (Supplementary Tables 6A, B).

Figure 4 (A) Clinical and Nutritional Parameters Related to Increased Appetite loss average score (Above the Mean of >21.56) According to Univariable Logistic Regression Analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; The summary statistics present N% for categorical variables and median [IQR] deviation for continuous variables. (B) Clinical and Nutritional Parameters Related to Increased Appetite loss average score (Above the Mean of >21.56) According to Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; The summary statistics present N% for categorical variables and median [IQR] deviation for continuous variables.

As part of the added value of PG-SGA, we also explored the relationship between self-reported symptoms and global QOL scores in the last 2 weeks. In multivariate logistic regression analysis, having no problem eating (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.50-0.71; P < 0.001) was an independent predictor of high QOL scores. Having no appetite (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.88-2.55; p< 0.001), nausea (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.34-1.95; P<0.001), vomiting (OR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.81-2.73; p<0.001), constipation (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.62-2.48; P <0.001) and pain (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.13-1.54; P <0.001) were an independent predictor of low QOL scores (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Multivariate logistic regression between patients' self-reported PG-SGA symptoms and poor global QOL average score (<82.83) in the past 2 weeks. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; The summary statistics present N% for categorical variables and median [IQR] deviation for continuous variables.

Our results suggest that women are independent predictors of lower global QOL scores, lower physical function scores, higher fatigue scores, and higher appetite loss scores, and that more attention should be paid to older patients when it comes to QOL in cancer patients. The symptoms of PG-SGA that occurred frequently in the last 2 weeks were also correlated with QOL scores.

Globally, gastric cancer continues to be a major contributor to cancer-related deaths, owing to its high mortality rate. This is largely because most diagnoses occur at later stages, when prognosis is often poor and treatment options are limited (22, 23). Alleviating symptoms, particularly malnourishment, and improving QOL should be a main objective of care (24). As far as we know, this is the first study to report an extensive examination of how the clinical aspects of nutrition impact the QOL of malnourished patients diagnosed with gastric cancer. Our results indicate that female patients may experience malnutrition more often than men. This is consistent with earlier studies, which also show a heightened risk of malnutrition in women with cancer (25). Therefore, when formulating nutritional assistance programs, it is crucial to focus on the dietary requirements of female patients.

Malnutrition poses a significant risk to patients with cancer as their nutritional condition can be compromised by both the illness itself and its treatment (26). Understanding the epidemiology of malnutrition could aid in the early management of complications during treatment, potentially improving patient QOL, the intensity of treatment, and outcome (27). Therefore, healthcare professionals should assess the nutritional condition of patients with gastric cancer and offer appropriate interventions or treatments for those suffering from malnutrition.

Individuals diagnosed with stage 4 gastric cancer were more prone to malnutrition, potentially due to interference from the tumor, which obstructs the normal functioning of the pylorus or duodenum and leads to inadequate intake. These patients also experience a surge in metabolic demands, which deteriorates their QOL and physical capacity (28). The results of our analysis are consistent with those reported in previous studies where patients with advanced or uncontrollable stomach cancer often suffer from malnutrition, which can impact their QOL (15). Malnourished patients with a low BMI also had a lower QOL. Previous studies have shown that malnutrition is a poor prognostic factor for many cancers (29). Following gastric cancer surgery, particularly after hospital discharge, malnutrition frequently occurs and can intensify (30). In addition, gastrointestinal malabsorption decreases ingestion of food and weight loss, which are not uncommon sequelae after a gastrectomy, and can lead to malnutrition, which in turn leads to prolonged recovery time, decreased physical function, and decreased QOL (31). Patients with gastric cancer who are undernourished and experience significant WL often report decreased QOL, as we observed in this study. Studies have shown that weight loss can affect cancer mortality and chances of cancer recurrence or secondary cancer formation (32). Nutritional interventions can enhance QOL and survival rates of patients with gastric cancer (32, 33).

The essential steps for preventing and managing malnutrition include early detection and tracking of WL, along with suitable nutritional strategies. The QOL of malnourished patients can be influenced by their geographic location and living conditions. HGS is another indicator of subpar QOL in malnourished patients with gastric cancer. Malnourished patients often experience muscle loss and physical decline, resulting in decreased HGS. Higher HGS is associated with a better physical status, as reported previously (34). A risk factor for cancer is sarcopenia because it increases mortality and postoperative complications and reduces treatment response and QOL (35). For cancer survivors, low HGS is connected with poorer QOL. Enhancing muscle strength should be a key focus to improve QOL of those who have survived cancer (36). Consequently, along with providing proper nutritional assistance, the overall treatment plan must include suitable measures for muscle development and rehabilitation to boost the patient’s physical health and overall well-being.

This study had some limitations. Other factors, such as inflammation and body composition, that were not assessed in this study, may impact QOL. We were unable to incorporate these factors into the multivariate analysis as the database we used had limited data on these parameters. Future studies should consider these variables. Secondly, we do not have survival information for the study population, and unfortunately we cannot compare whether the PG-SGA stage assessment or the PG-SGA numerical score analyzed in this study is more beneficial for the survival of patients with gastric cancer. Moreover, both PG-SGA and EORTC QLQC30 questionnaires are asked by professional investigators to study the population, which may cause the deviation of scores due to personal subjective reasons.

Malnutrition, which impacts functional survival and QOL, is common in patients with cancer (37). Malnutrition has negative impacts on the clinical outcome, prolongs hospital stays, and reduces the QOL for patient (38). Our findings may help to focus on certain factors in malnourished gastric cancer patients, thereby improving their QOL.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Medical Ethical Review Committees and Institutional Review Boards of the participating registered hospitals. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

HZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. GR: Conceptualization, Software, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. YC: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. SL: Validation, Writing – original draft. XYL: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – original draft. XGL: Writing – original draft. SL: Writing – review & editing. HS: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2022YFC2009600, 2022YFC2009601), Laboratory for Clinical Medicine, Capital Medical University (2023-SYJCLC01), National Multidisciplinary Cooperative Diagnosis and Treatment Capacity Project for Major Diseases : Comprehensive Treatment and Management of Critically Ill Elderly Inpatients (No.2019.YLFW) to HS.

We sincerely thank the INSCOC project members for their substantial work on data collection and patient follow-up.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2024.1336859/full#supplementary-material

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2. Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N, Chen WQ. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J (Engl). (2021) 134:783–91. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474

3. Machlowska J, Baj J, Sitarz M, Maciejewski R, Sitarz R. Gastric cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, classification, genomic characteristics and treatment strategies. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21(11):4012. doi: 10.3390/ijms21114012

4. Chia NY, Tan P. Molecular classification of gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. (2016) 27:763–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw040

5. Schütte K, Schulz C, Middelberg-Bisping K. Impact of gastric cancer treatment on quality of life of patients. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. (2021) 50-51:101727. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2021.101727

6. Efficace F, Osoba D, Gotay C, Sprangers M, Coens C, Bottomley A. Has the quality of health-related quality of life reporting in cancer clinical trials improved over time? Towards bridging the gap with clinical decision making. Ann Oncol. (2007) 18:775–81. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl494

7. Kelley AS, Meier DE. Palliative care–a shifting paradigm. N Engl J Med. (2010) 363:781–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1004139

8. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2010) 363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678

9. Patel JD, Krilov L, Adams S, Aghajanian C, Basch E, Brose MS, et al. Clinical cancer advances 2013: annual report on progress against cancer from the American society of clinical oncology. J Clin Oncol. (2014) 32:129–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.7076

10. Jordan K, Aapro M, Kaasa S, Ripamonti CI, Scotté F, Strasser F, et al. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol. (2018) 29:36–43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx757

11. Lippman SM, Hawk ET. Cancer prevention: from 1727 to milestones of the past 100 years. Cancer Res. (2009) 69:5269–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1750

12. Suarez-Almazor M, Pinnix C, Bhoo-Pathy N, Lu Q, Sedhom R, Parikh RB. Quality of life in cancer care. Med. (2021) 2:885–8. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2021.07.005

13. Lewandowska A, Rudzki G, Lewandowski T, Próchnicki M, Rudzki S, Laskowska B, et al. Quality of life of cancer patients treated with chemotherapy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17(19):6938. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17196938

14. Xunlin NG, Lau Y, Klainin-Yobas P. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions among cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. (2020) 28:1563–78. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05219-9

15. Mizukami T, Piao Y. Role of nutritional care and general guidance for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer. Future Oncol. (2021) 17:3101–9. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0186

16. Bovero A, Leombruni P, Miniotti M, Rocca G, Torta R. Spirituality, quality of life, psychological adjustment in terminal cancer patients in hospice. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2016) 25:961–9. doi: 10.1111/ecc.2016.25.issue-6

17. Fu L, Feng X, Jin Y, Lu Z, Li R, Xu W, et al. Symptom clusters and quality of life in gastric cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2022) 63:230–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.09.003

18. Weir CB, Jan A. BMI classification percentile and cut off points. Treasure Island (FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC (2023).

19. Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2020) 21:300–7.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012

20. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. (1993) 85:365–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

21. Giesinger JM, Kieffer JM, Fayers PM, Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Scott NW, et al. Replication and validation of higher order models demonstrated that a summary score for the EORTC QLQ-C30 is robust. J Clin Epidemiol. (2016) 69:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.007

22. Necula L, Matei L, Dragu D, Neagu AI, Mambet C, Nedeianu S, et al. Recent advances in gastric cancer early diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. (2019) 25:2029–44. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i17.2029

23. Pan X, Tao H, Nie M, Liu Y, Huang P, Liu S, et al. A clinical study of traditional Chinese medicine prolonging the survival of advanced gastric cancer patients by regulating the immunosuppressive cell population: A study protocol for a multicenter, randomized controlled trail. Med (Baltimore). (2020) 99:e19757. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019757

24. Mahar AL, Coburn NG, Karanicolas PJ, Viola R, Helyer LK. Effective palliation and quality of life outcomes in studies of surgery for advanced, non-curative gastric cancer: a systematic review. Gastric Cancer. (2012) 15 Suppl 1:S138–45. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0070-0

25. Guo ZQ, Yu JM, Li W, Fu ZM, Lin Y, Shi YY, et al. Survey and analysis of the nutritional status in hospitalized patients with Malignant gastric tumors and its influence on the quality of life. Support Care Cancer. (2020) 28:373–80. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04803-3

26. Arends J, Baracos V, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Calder PC, Deutz NEP, et al. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr. (2017) 36:1187–96. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.06.017

27. Bossi P, Delrio P, Mascheroni A, Zanetti M. The spectrum of malnutrition/cachexia/sarcopenia in oncology according to different cancer types and settings: A narrative review. Nutrients. (2021) 13(6):1980. doi: 10.3390/nu13061980

28. Troncone E, Fugazza A, Cappello A, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Monteleone G, Repici A, et al. Malignant gastric outlet obstruction: Which is the best therapeutic option? World J Gastroenterol. (2020) 26:1847–60. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i16.1847

29. Ma LX, Taylor K, Espin-Garcia O, Anconina R, Suzuki C, Allen MJ, et al. Prognostic significance of nutritional markers in metastatic gastric and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. (2021) 10:199–207. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3604

30. Meng Q, Tan S, Jiang Y, Han J, Xi Q, Zhuang Q, et al. Post-discharge oral nutritional supplements with dietary advice in patients at nutritional risk after surgery for gastric cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr. (2021) 40:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.04.043

31. Gharagozlian S, Mala T, Brekke HK, Kolbjørnsen LC, Ullerud ÅA, Johnson E. Nutritional status, sarcopenia, gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life after gastrectomy for cancer - A cross-sectional pilot study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. (2020) 37:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.03.001

32. Salas S, Cottet V, Dossus L, Fassier P, Ginhac J, Latino-Martel P, et al. Nutritional Factors during and after Cancer: Impacts on Survival and Quality of Life. Nutrients. (2022) 14(14):2958. doi: 10.3390/nu14142958

33. Rinninella E, Cintoni M, Raoul P, Pozzo C, Strippoli A, Bria E, et al. Effects of nutritional interventions on nutritional status in patients with gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr ESPEN. (2020) 38:28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.05.007

34. Cheung AT, Li WHC, Ho LLK, Xia W, Luo Y, Chan GCF, et al. Associations of physical activity and handgrip strength with different domains of quality of life in pediatric cancer survivors. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14(10):2554. doi: 10.3390/cancers14102554

35. Souza VF, Ribeiro TSC, Marques RA, Petarli GB, Pereira TSS, Rocha JLM, et al. SARC-CalF-assessed risk of sarcopenia and associated factors in cancer patients. Nutr Hosp. (2020) 37:1173–8. doi: 10.20960/nh.03158

36. Kim H, Yoo S, Kim H, Park SG, Son M. Cancer survivors with low hand grip strength have decreased quality of life compared with healthy controls: the Korea National Health and nutrition examination survey 2014-2017. Korean J Fam Med. (2021) 42:204–11. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.20.0060

37. Xu H, Song C, Yin L, Wang C, Fu Z, Guo Z, et al. Extension protocol for the Investigation on Nutrition Status and Clinical Outcome of Patients with Common Cancers in China (INSCOC) study: 2021 update. Precis Nutr. (2022) 1:e00014. doi: 10.1097/PN9.0000000000000014

Keywords: gastric cancer, quality of life, malnourishment, PG-SGA, young and old

Citation: Zhao H, Liu C, Ruan G, Zheng X, Chen Y, Lin S, Liu X, Shi J, Li X, Li S and Shi H (2024) The quality of life impacting factors in malnourished patients with gastric cancer. Front. Oncol. 14:1336859. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1336859

Received: 11 November 2023; Accepted: 09 April 2024;

Published: 25 April 2024.

Edited by:

Xiaohua Jiang, Tongji University, ChinaReviewed by:

Chengyu Liu, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (CAMS), ChinaCopyright © 2024 Zhao, Liu, Ruan, Zheng, Chen, Lin, Liu, Shi, Li, Li and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanping Shi, c2hpaHBAY2NtdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.