- 1Department of Oncology, Xiangyang No. 1 People’s Hospital, Hubei University of Medicine, Xiangyang, China

- 2Department of Orthopedics, Xiangyang No. 1 People’s Hospital, Hubei University of Medicine, Xiangyang, China

- 3Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Background: Infantile hepatic hemangioma (IHH) is a common vascular, fast-growing hepatic tumor that is usually accompanied by multiple cutaneous hemangiomas. Diffuse IHH (DIHH) is a rare type of IHH that exhibits many tumors with nearly complete hepatic parenchymal replacement. At present, there is no specific standardized treatment plan for DIHH. Herein, we present the case of a 2-month-old girl with DIHH and without cutaneous hemangioma who achieved complete remission after undergoing propranolol monotherapy.

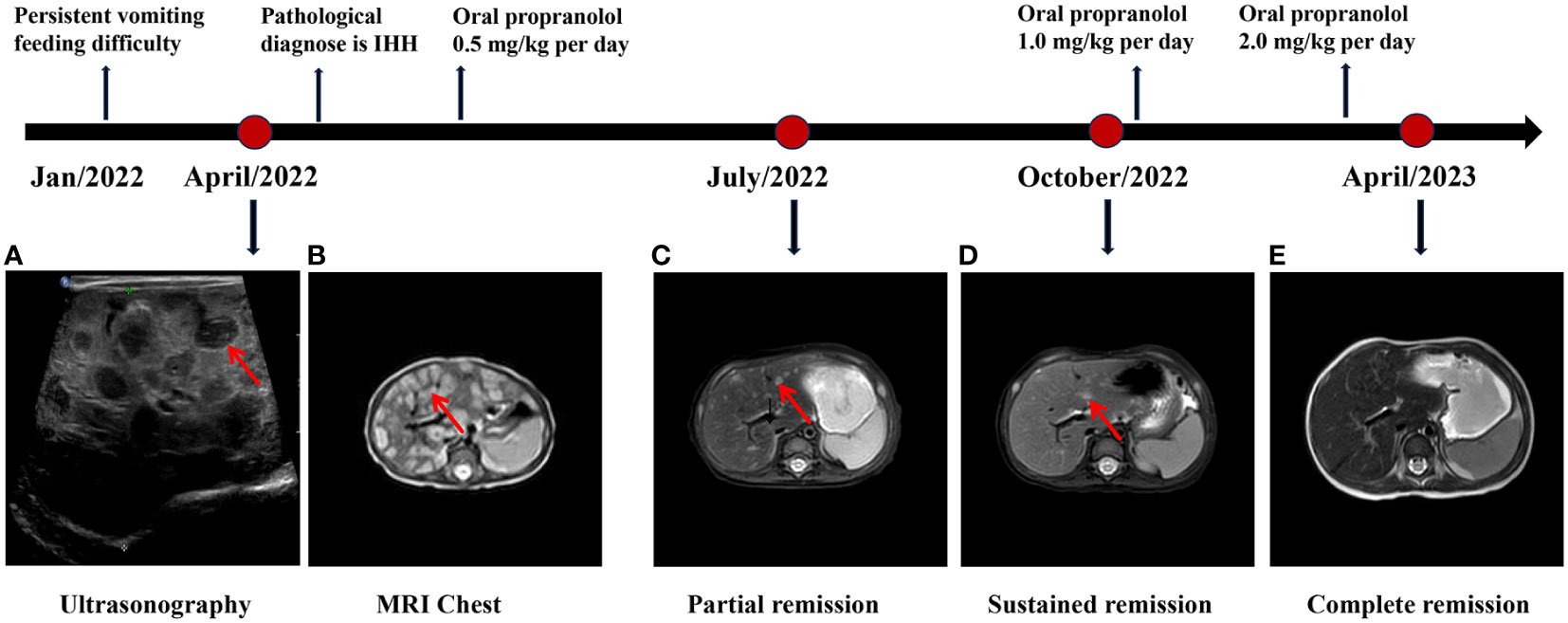

Case presentation: The infant with low birth weight was presented to the pediatric department with a 2-month history of persistent vomiting and feeding difficulty. Ultrasonography and abdominal magnetic resonance imaging revealed hepatomegaly and diffused intrahepatic lesions. A computed tomography-guided percutaneous liver biopsy was performed, and the pathological examination suggested the diagnosis was DIHH. The patient exhibited remarkably response to an increasing dose of oral propranolol, from 0.5 mg/kg to 2 mg/kg every day. The intrahepatic lesions were almost completely regressed after one year of treatment and no distinct adverse reaction was observed.

Conclusion: DIHH can induce life-threatening complications that require prompt interventions. Propranolol monotherapy can be an effective and safe first-line treatment strategy for DIHH.

Introduction

Infantile hepatic hemangioma (IHH) is a common benign mesenchymal tumor of the liver in fetuses and infants with a slightly high predominance in females. Approximately 90% of IHH cases are diagnosed within the age of six months and 30% are detected within the first month of life (1).

IHH was first described in 1919, and was frequently identified due to variable clinical symptomatology. The earliest known case of IHH were categorized into two subtypes in 1971 based on the tumor size and vascularity, namely type 1 and type 2 (2). IHH type 1 is usually considered benign and is the most common variant, whereas type 2 accounts for an insignificant portion of IHHs and can be malignant (3). In 2004, IHH was categorized into symptomatic and asymptomatic types based on the tumor size and hemodynamic effects (4).

A systematic classification scheme for IHH was introduced in 2007, which divided IHH lesions into focal, multifocal, and diffuse based on the clinical presentation, radiographic appearance, pathological features, physiological behavior, and natural history of patients (5). Focal IHH is generally manifested as a well-defined, solitary, and spherical tumor in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Most focal IHHs are asymptomatic. Only a few cases may present with minor anemia or thrombocytopenia, and cases are rarely accompanied by cutaneous hemangiomas. Multifocal IHH shared a similar MRI feature with multifocal lesions and may present with arteriovenous shunts. Nearly 60% of multifocal cases can present with more than five cutaneous hemangiomas (6) and some cases are associated with secondary high-output cardiac failure. DIHH presented as innumerable lesions spread into the entire liver, leading to the near-total replacement of the hepatic parenchyma. Infants with DIHH are more likely to develop serious complications, such as massive associated compression, congestive heart failure thrombocytopenia, and hypothyroidism, compared with those with the other two types (7).

Propranolol has been recommended as the first-line treatment for IHH in the American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline (8). However, to date, there is no gold standard treatment available for DIHH. The efficacy of propranolol as a first-line treatment for life-threatening DIHH has not been demonstrated. Additionally, the optimal treatment choice for patients who do not respond to initial therapy with propranolol remains unclear. In this case study, we present a successful treatment of infant DIHH using conservative oral propranolol monotherapy. Based on our experience and the existing literature, we also propose diagnosis and treatment recommendations.

Case presentation

A 2-month-year old infant girl with persistent vomiting and feeding difficulty was admitted to Xiangyang No. 1 People’s Hospital. The birth, family, and medical history of the patient were normal. The birthweight of the patient was 1.3 kg and she gained only 1.2 kg after 3 months. No cutaneous strawberry hemangioma was observed. The physical examination revealed that the liver could be easily palpated at 1 cm below the right costal margin. The laboratory tests, including routine blood tests, tumor markers, and thyroid function tests, including serum thyroid-stimulating hormone, free triiodothyronine, and free thyroxine, were all normal. Biochemical tests revealed slight mild increases in alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, at the level of 77.5 IU/L and 131.35 IU/L (normal 0-40 IU/L), respectively.

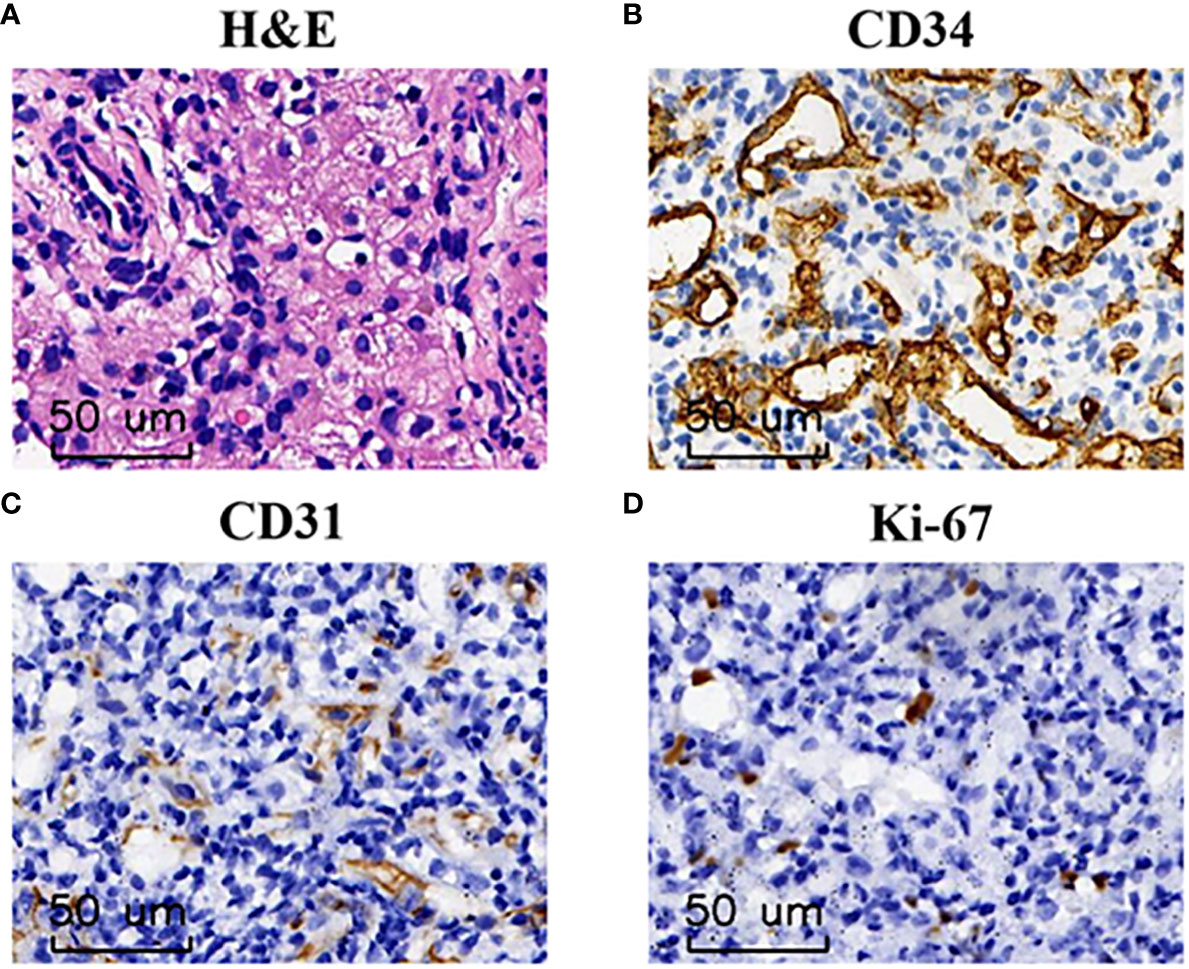

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) indicated diffusely heterogeneous hepatomegaly with diffused rounded hypoechoic lesions (Figure 1A). Cardiac ultrasound indicated mild-moderate mitral and tricuspid regurgitation and left ventricular ejection fractions was 60%. The MRI revealed diffuse lesions with the hypointense pattern on the T1-weighted images and hyperintense pattern on the T2-weighted images in the liver (Figure 1B). Accordingly, a computed tomography-guided percutaneous live biopsy was performed after the oral administration of chloral hydrate (0.5 ml/kg). Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining revealed that the tumor was composed of several proliferating vascular endothelial cells (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemical analysis showed positive staining for CD31 and CD34 (Figures 2B, C), with a low Ki-67 index (Figure 2D). Thus, the definite diagnosis was DIHH based on the imaging and pathological evaluations.

Figure 1 The diagnosis and treatment process of DIHH. (A) The abdominal ultrasonography indicated diffusely heterogeneous hepatomegaly with diffused rounded hypoechoic lesions. (B) The MRI revealed diffuse lesions with hyperintense pattern on the T2-weighted images in the liver. (C-E) The MRI indicates a continuous regression in the lesions during the 6 months follow-up, and ultimately reaching complete remission (CR).

Figure 2 The pathological finding of DIHH. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining identified a large number of proliferating vascular endothelial cells at 200× magnification. (B–D) Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that tumor cells were immunoreactive for CD34 (B) and CD31 (C), low Ki-67 index (D) at the magnification of ×200.

The patient underwent an oral monotherapy of 0.5 mg/kg of propranolol twice daily, which was gradually increased to 2 mg/kg/day. During the initial three days of treatment, the blood pressure, heart rate, and blood glucose levels of the patient were closely monitored and no reaction was observed. One week after the treatment, the vomiting symptoms of the infant stopped and milk consumption increase significantly. Most lesions were significantly regressed, and some lesions shrunk after three months of treatment (Figure 1C). The patient was persistently responsible for the current treatment and achieved near-complete remission after six months of treatment (Figure 1D). The intrahepatic lesions were completely regressed after one year of treatment and the patient was developing well (Figure 1E). The detailed diagnosis and treatment process is shown in Figure 1.

Discussion

IHH is the most common pediatric vascular tumor in infants. IHH was previously called infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma. The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies first adopted the name IHH in 1982 based on the classification of vascular anomalies (9). IHH is commonly used instead of infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma to avoid confusion with other malignant vascular tumors including Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

IHH exhibits a slightly higher predominance in females than in males and familial tendency but without racial predilection (6). The reported incidence of IHH was approximately 1/20,000 newborns. The true incidence rate is underestimated because some cases are asymptomatic and undiagnosed. Previous studies have indicated that multifocal IHH is the most common type of IHH, whereas DIHH only accounts for > 20% of all IHH cases (10). This could be because multifocal IHH exhibits a higher probability of accompanying cutaneous hemangiomas than the other two types, which can be easily diagnosed (10).

The pathogenesis of IHH is poorly understood. One possible mechanism is the aberrant response of pluripotent stem cells to stimuli, including hypoxia and the renin–angiotensin–system. Focal IHHs are clinically and biologically distinct from multifocal and DIHHs (10). Multifocal IHH and DIHH manifest in the initial days and weeks of life. However, focal IHH is usually diagnosed prenatally. Moreover, all multifocal and DIHHs positively express glucose transporter isoform 1 (GLUT 1), which is a classic histological marker that differentiates IHH from other types of vascular anomalies. However, GLUT1 is rarely expressed in focal IHH (10, 11).

Approximately all cases of DIHHs are symptomatic and the clinical manifestations of DIHH are variable. The rapidly-proliferating masses can compress of the inferior vena cava, leading to hepatomegaly or abdominal distention, secondary hepatic failure, pulmonary embarrassment, and multi-organ system failure (12). These highly vascularized tumors can form arteriovenous shunts within the lesions, causing aggressive high blood volume and life-threatening congestive heart failure (13). The presence of several lesions can also trap of platelets within the tumors, resulting in anemia, thrombocytopenia, and consumptive coagulopathy (14). In addition, the overproduction of iodothyronine deiodinase type 3 and humoral thyrotropin-like factor by tumors is associated with hypothyroidism (15).

Generally, most cases of DIHHs can be diagnosed based on the clinical features and imagining results of the patient, and pathological examination is not required (16). US is the preferred imaging test for identifying DIHH, MRI can be chosen when the diagnosis is uncertain. Computed tomography is not recommended because it has a decreased resolution and an increased risk of radiation exposure in infants. A biopsy can be performed when clinical and imaging presentations are not atypical. In this case, we finally performed a biopsy using a fine needle aspiration to confirm the diagnosis due to the atypical clinical presentation.

DIHH can present with life-threatening complications and sporadic cases can undergo malignancy (17). Therefore, nearly all DIHH cases require systemic treatment. Several different medical therapies, such as steroids, interferon, and even cytotoxic agents, have been used for treating tumors and associated secondary symptoms (18). Corticosteroids were previously considered the first-line therapy for DIHH (5). However, owing to the subsequent side effects, such as abnormal fat deposits, gastric irritation, osteoporosis, and infection risk, its long-term application has been limited. Furthermore, approximately 23.1% of infants can present steroid resistance (19). Interferons were previously used to shrink tumors when patients were unresponsive to steroids (20). However, recent guidelines no long recommend interferon therapy owing to the risk of serious complications, including spastic diplegia and motor developmental disturbances (21).

Propranolol, a nonselective antagonist of β-1 and β-2 adrenergic receptors, was serendipitously found to pose an anti-proliferative effect in IHH in 2008 (22). The exact underlying mechanisms of propranolol in promoting hemangioma involution are unclear. It may be due to pericyte-mediated vasoconstriction, reduction of the vascular endothelial and basic fibroblast growth factor, and the inactivation of the renin-angiotensin system (23). In 2014, propranolol was approved by the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the systemic treatment of IHH. Since then, propranolol was considered an effective and safe drug managing of IHH and it has replaced steroids (6). Furthermore, some case series have also demonstrated the efficacy of monotherapy with propranolol in DIHH (24, 25).

The recommended initial dose of propranolol by the FDA is 0.6 mg/kg, twice daily, with a gradual increase over 2 weeks to a maintain a dose of 1.7 mg/kg twice daily (8). European expert consensus group recommended that the starting dose of propranolol should be 1.0 mg/kg per day and a targeted dose should be 2.0 to 3.0 mg/kg per day and divided into two or three doses (26). The dosage should be adjusted based on the condition of the patient, especially in patients with (posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta/cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities) and adverse reactions, such as sleep disturbance (8, 27).

Treatment should sustain for at least 6 months and maintain until 12 months of age. Rebound growth may occur in 10% to 25% of patients during the tapering period or after the withdrawal period, which can occur even 6 months after the completion of therapy (28, 29). A large multicenter retrospective cohort study reported that patients whose therapy was discontinued at <12 months of age, especially below 9 months, exhibited the greatest risk of rebound. The lowest risk of rebound is in patients whose treatment was discontinued between 12 and 15 months of age (28).

Surgical or radiological intervention should be promptly performed when life-threatening symptoms progress after medical treatment or malignancy was present. Hepatic artery embolization (HAE) or Hepatic artery ligation (HAL) is an effective alternative approach to decrease shunts and counteracts cardiac failure (30). Orthotopic liver transplantation may also be chosen for patients with DIHH because total hepatectomy cannot be sustained (6).

Previous studies have reported that multimodal strategies, including corticosteroids, vincristine or propranolol and levothyroxine, have successfully treated DIHH (31). In our case study, considering the infant did not exhibit significant hypothyroidism or heart failure, we selected a conservative treatment with propranolol monotherapy. The patient achieved complete remission after one year of treatment, and no adverse reaction was found. This case study indicates that oral propranolol is an effective and safe conservative treatment for DIHH. The limitation of our study is that it is a case report, we believe that larger clinical studies to further investigate the effectiveness of propranolol monotherapy are still needed.

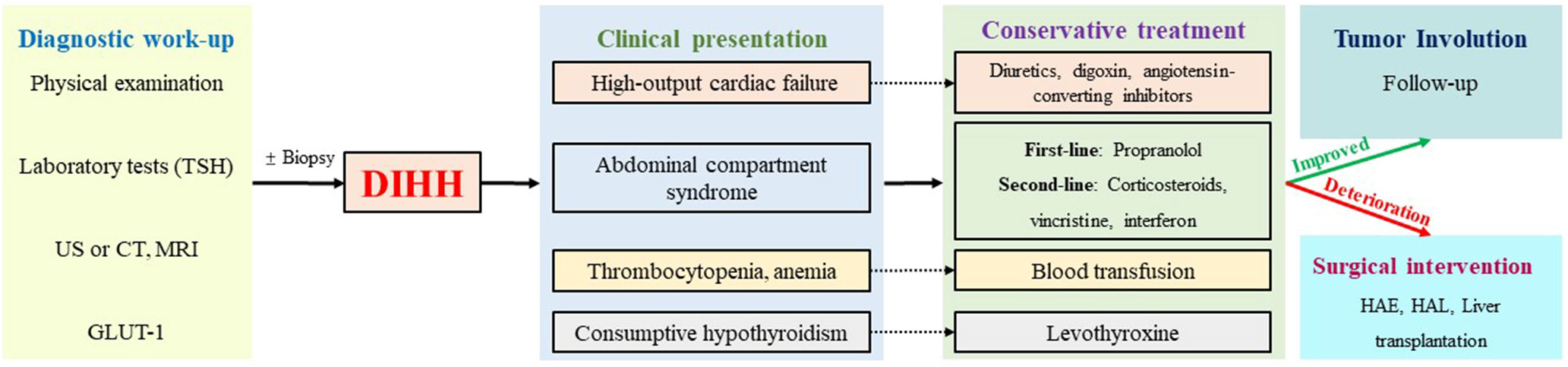

DIHH exhibits a relatively high mortality rate, with the reported highest rate of up to 53.8% (6). Serious complications, including abdominal compartment syndrome and heart failure, contribute to early mortality, whereas late mortality is mainly associated with incorrect treatment choices (32). Therefore, early diagnosis and prompt and effective intervention are important for treating DIHH. Based on the previous literature reports and our experience, we summarized the detailed diagnosis and treatment procedures of DIHH (Figure 3).

Figure 3 The diagnosis and treatment algorithms for DIHH. US, ultrasonography; CT, computed tomography MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; GLUT-1, glucose transporter isoform 1; HAE, Hepatic artery embolization; HAL, Hepatic artery ligation.

Propranolol can be recommended as first-line treatment for DIHH (33). In cases where patients are accompanied by high-output cardiac failure, diuretics, digoxin, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors may also be administered. Additionally, levothyroxine should be supplemented if consumptive hypothyroidism occurs, and blood component transfusion may be necessary in cases of hemocytopenia. For refractory cases, corticosteroids, vincristine, and interferon can be considered as second-line agents. In instances where pharmacologic therapy fails or there is deterioration, surgical intervention, such as HAE or HAL, was required to achieve satisfactory symptom control (14). In rare cases where the above treatments are ineffective, liver transplantation could be considered as an option (34).

To summarize, we have reported a patient with DIHH presenting having low body weight, persistent vomiting, and feeding difficulty. The patient did not have cutaneous hemangiomas or any other typical presentations and was completely cured after 1 year of oral propranolol monotherapy. We also propose an initial diagnosis and treatment algorithm for DIHH. We believe our study can provide some helpful insights into the precise diagnosis and treatment of DIHH in the future.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics and Scientific Committee of Hubei University of Medicine with approval number XYY2021002. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual for the publication of any potentially identifiable images included in this article.

Author contributions

ZL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ZW: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YD: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. XY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. DZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants number: 82200214), Key Research and Development Project of Hubei (Grants number: 2022BCE028), Young and middle-aged talent program of Hubei Education Bureau (Grants number: Q20222101), Platform Special Fund for Scientific Research of Xiangyang No.1 People’s Hospital (Grants number: XYY2022P05) and Instructional projects of Hubei Provincial Health and Health Commission (WJ2023F074).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Razon MJ, Kräling BM, Mulliken JB, Bischoff J. Increased apoptosis coincides with onset of involution in infantile hemangioma. Microcirculation (1998) 5(2-3):189–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.1998.tb00068.x

2. Dehner LP, Ishak KG. Vascular tumors of the liver in infants and children. A study of 30 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathology (1971) 92(2):101–11.

3. Sigamani E, Iyer VK, Agarwala S. Fine needle aspiration cytology of infantile haemangioendothelioma of the liver: a report of two cases. Cytopathology Off J Br Soc Clin Cytology (2010) 21(6):398–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2010.00739.x

4. Kassarjian A, Zurakowski D, Dubois J, Paltiel HJ, Fishman SJ, Burrows PE. Infantile hepatic hemangiomas: clinical and imaging findings and their correlation with therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenology (2004) 182(3):785–95. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820785

5. Christison-Lagay ER, Burrows PE, Alomari A, Dubois J, Kozakewich HP, Lane TS, et al. Hepatic hemangiomas: subtype classification and development of a clinical practice algorithm and registry. J Pediatr Surg (2007) 42(1):62–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.041

6. Zavras N, Dimopoulou A, Machairas N, Paspala A, Vaos G. Infantile hepatic hemangioma: current state of the art, controversies, and perspectives. Eur J Pediatr (2020) 179(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00431-019-03504-7

7. Butters CT, Nash M. Infantile hepatic hemangiomas. N Engl J Med (2021) 385(3):e10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1907892

8. Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, Darrow DH, Blei F, Greene AK, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics (2019) 143(1):e20183475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3475

9. Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg (1982) 69(3):412–22. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198203000-00002

10. Kulungowski AM, Alomari AI, Chawla A, Christison-Lagay ER, Fishman SJ. Lessons from a liver hemangioma registry: subtype classification. J Pediatr Surg (2012) 47(1):165–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.10.037

11. Ernst L, Grabhorn E, Brinkert F, Reinshagen K, Königs I, Trah J. Infantile hepatic hemangioma: avoiding unnecessary invasive procedures. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr (2020) 23(1):72–8. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2020.23.1.72

12. Li K, Wang Z, Liu Y, Yao W, Gong Y, Xiao X. Fine clinical differences between patients with multifocal and diffuse hepatic hemangiomas. J Pediatr Surg (2016) 51(12):2086–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.09.045

13. Rialon KL, Murillo R, Fevurly RD, Kulungowski AM, Christison-Lagay ER, Zurakowski D, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with multifocal and diffuse hepatic hemangiomas. J Pediatr Surg (2015) 50(5):837–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.09.056

14. Macdonald A, Durkin N, Deganello A, Sellars ME, Makin E, Davenport M. Historical and contemporary management of infantile hepatic hemangioma: A 30-year single-center experience. Ann Surg (2022) 275(1):e250–e5. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003881

15. Kim YH, Lee YA, Shin CH, Hong KT, Kim GB, Ko JS, et al. A case of consumptive hypothyroidism in a 1-month-old boy with diffuse infantile hepatic hemangiomas. J Korean Med Sci (2020) 35(22):e180. doi: 10.3904/kjm.2020.95.1.18

16. Iacobas I, Phung TL, Adams DM, Trenor CC 3rd, Blei F, Fishman DS, et al. Guidance document for hepatic hemangioma (Infantile and congenital) evaluation and monitoring. J Pediatr (2018) 203:294–300.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.012

17. Kamath SM, Mysorekar VV, Kadamba P. Hepatic angiosarcoma developing in an infantile hemangioendothelioma: A rare case report. J Cancer Res Ther (2015) 11(4):1022. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.146132

18. Dickie B, Dasgupta R, Nair R, Alonso MH, Ryckman FC, Tiao GM, et al. Spectrum of hepatic hemangiomas: management and outcome. J Pediatr Surg (2009) 44(1):125–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.021

19. Ji Y, Chen S, Xiang B, Xu Z, Jiang X, Liu X, et al. Clinical features and management of multifocal hepatic hemangiomas in children: a retrospective study. Sci Rep (2016) 6:31744. doi: 10.1038/srep31744

20. Kalpatthi R, Germak J, Mizelle K, Yeager N. Thyroid abnormalities in infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer (2007) 49(7):1021–4. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20801

21. Barlow CF, Priebe CJ, Mulliken JB, Barnes PD, Mac Donald D, Folkman J, et al. Spastic diplegia as a complication of interferon Alfa-2a treatment of hemangiomas of infancy. J Pediatr (1998) 132(3 Pt 1):527–30. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70034-4

22. Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, Boralevi F, Thambo J-B, Taïeb A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med (2008) 358(24):2649–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0708819

23. Ji Y, Chen S, Xu C, Li L, Xiang B. The use of propranolol in the treatment of infantile haemangiomas: an update on potential mechanisms of action. Br J Dermatol (2015) 172(1):24–32. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13388

24. Ray G, Das K, Sarkar A, Bose D, Halder P. Propranolol monotherapy in multifocal/diffuse infantile hepatic hemangiomas in Indian children: A case series. J Clin Exp Hepatol (2023) 13(4):707–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2023.02.005

25. Yang K, Peng S, Chen L, Chen S, Ji Y. Efficacy of propranolol treatment in infantile hepatic haemangioma. J Paediatr Child Health (2019) 55(10):1194–200. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14375

26. Hoeger PH, Harper JI, Baselga E, Bonnet D, Boon LM, Ciofi Degli Atti M, et al. Treatment of infantile haemangiomas: recommendations of a European expert group. Eur J Pediatr (2015) 174(7):855–65. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2570-0

27. Garzon MC, Epstein LG, Heyer GL, Frommelt PC, Orbach DB, Baylis AL, et al. PHACE syndrome: consensus-derived diagnosis and care recommendations. J Pediatr (2016) 178:24–33.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.07.054

28. Shah SD, Baselga E, McCuaig C, Pope E, Coulie J, Boon LM, et al. Rebound growth of infantile hemangiomas after propranolol therapy. Pediatrics (2016) 137(4):e20151754. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1754

29. Léauté-Labrèze C, Hoeger P, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Guibaud L, Baselga E, Posiunas G, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma. N Engl J Med (2015) 372(8):735–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404710

30. Wang L, Li J, Song D, Guo L. Clinical evaluation of transcatheter arterial embolization combined with propranolol orally treatment of infantile hepatic hemangioma. Pediatr Surg Int (2022) 38(8):1149–55. doi: 10.1007/s00383-022-05143-w

31. Yeh I, Bruckner AL, Sanchez R, Jeng MR, Newell BD, Frieden IJ. Diffuse infantile hepatic hemangiomas: a report of four cases successfully managed with medical therapy. Pediatr Dermatol (2011) 28(3):267–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01421.x

32. Daller JA, Bueno J, Gutierrez J, Dvorchik I, Towbin RB, Dickman PS, et al. Hepatic hemangioendothelioma: clinical experience and management strategy. J Pediatr Surg (1999) 34(1):98–105. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(99)90237-3

33. Varrasso G, Schiavetti A, Lanciotti S, Sapio M, Ferrara E, De Grazia A, et al. Propranolol as first-line treatment for life-threatening diffuse infantile hepatic hemangioma: A case report. Hepatol (Baltimore Md) (2017) 66(1):283–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.29028

Keywords: infantile hepatic hemangioma, diffuse infantile hepatic hemangioma, propranolol, safety, efficacy

Citation: Li Z, Wu Z, Dong Y, Yuan X and Zhang D (2024) Diffuse infantile hepatic hemangioma successfully treated with propranolol orally: a case report and literature review. Front. Oncol. 14:1336742. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1336742

Received: 11 November 2023; Accepted: 12 January 2024;

Published: 29 January 2024.

Edited by:

Kaiying Yang, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, ChinaReviewed by:

Nguyen Minh Duc, Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, VietnamDarja Paro-Panjan, University Children’s Hospital Ljubljana, Slovenia

Takamichi Ishikawa, Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, Japan

Copyright © 2024 Li, Wu, Dong, Yuan and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaojun Yuan, yuanxiaojun@xinhuamed.com.cn; Dongdong Zhang, zhangdongdong@whu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Zengyan Li1†

Zengyan Li1†