- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Peking University Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China

- 2Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Shenzhen Peking University-Hongkong University of Science and Technology (PKU-HKUST) Medical Center, Shenzhen, China

- 3Shenzhen Key Laboratory on Technology for Early Diagnosis of Major Gynecologic Diseases, Peking University Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China

- 4Department of General Surgery, Shanghai General Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, China

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sanming Project of Medicine in Peking University Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Background: Few articles have focused on the cytological misinterpretation of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). Due to estrogen deficiency, cervical epithelial cells in postmenopausal women tend to show atrophic change that looks like HSIL on Papanicolaou-stained cytology slides, resulting in a higher rate of cytological misinterpretation. P16INK4a immunocytochemical staining (P16 cytology) can effectively differentiate diseased cells from normal atrophic ones with less dependence on cell morphology.

Objective: To evaluate the role of P16 cytology in differentiating cytology HSIL from benign atrophy in women aged 50 years and above.

Methods: Included in this analysis were women in a cervical cancer screening project conducted in central China who tested positive for high-risk human papillomavirus (hr-HPV) and returned back for triage with complete data of primary HPV testing, liquid-based cytology (LBC) analysis, P16 immuno-stained cytology interpretation, and pathology diagnosis. The included patients were grouped by age: ≥50 (1,127 cases) and <50 years (1,430 cases). The accuracy of LBC and P16 cytology in the detection of pathology ≥HSIL was compared between the two groups, and the role of P16 immuno-stain in differentiating benign cervical lesions from cytology ≥HSIL was further analyzed.

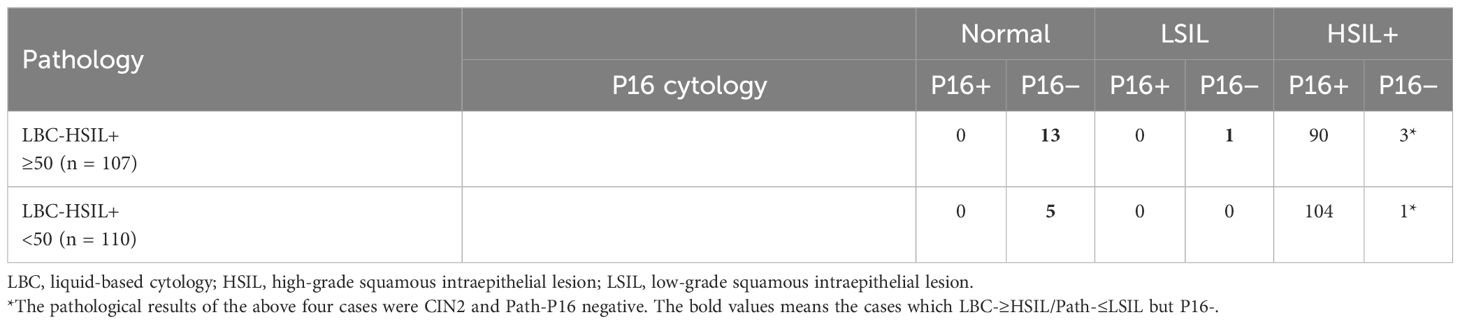

Results: One hundred sixty-seven women (14.8%; 167/1,127) in the ≥50 group and 255 (17.8%, 255/1,430) in the <50 group were pathologically diagnosed as HSIL (Path-HSIL). LBC [≥Atypical Squamous Cell Of Undetermined Significance (ASCUS)] and P16 cytology (positive) respectively detected 63.9% (163/255) and 90.2% (230/255) of the Path-≥HSIL cases in the <50 group and 74.3% (124/167) and 93.4% (124/167) of the Path-≥HSIL cases in the ≥50 group. LBC matched with pathology in 105 (41.2%) of the 255 Path-≥HSIL cases in the <50 group and 93 (55.7%) of the 167 Path-≥HSIL cases in the ≥50 group. There were five in the <50 group and 14 in the ≥50 group that were Path-≤LSIL cases, which were interpreted by LBC as HSIL, but negative in P16 cytology.

Conclusion: P16 cytology facilitates differentiation of Path-≤LSIL from LBC-≥HSIL for women 50 years of age and above. It can be used in the lower-resource areas, where qualified cytologists are insufficient, as the secondary screening test for women aged ≥50 to avoid unnecessary biopsies and misinterpretation of LBC primary or secondary screening.

1 Background

Diagnostics and treatment of cervical precancer for postmenopausal women are important to cervical cancer prevention in aged women because of the tendency of social aging in many countries. Cervical cytology remains the standard cervical cancer screening test worldwide for either primary or secondary screening. However, evidence shows that some atrophic changes in squamous and columnar epithelium may be misinterpreted as high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) when analyzing the exfoliated cervical cells from postmenopausal women who are usually low in estrogen (1). However, many studies have evidenced that overexpression of P16 protein is positively related to transformative high-risk human papillomavirus (hr-HPV) infection and grade of cervical cell proliferation and can be an objective indicator for lesion grade. As a tumor suppressor that is highly related to HSIL and cervical cancer, P16 overexpression can be a biomarker for early diagnosis of squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) and evaluation of the lesion prognosis (2).

A P16 immunocytochemical stain technology was developed by Senying Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China), which uses P16INK4a monoclonal antibodies (sy-a01) to stain exfoliated cervical cells that were diluted at a ratio of 1:4,000 on PathCIN®P16INK4a automatic staining system (P16 immuno-stained cytology). This technology has been demonstrated to be more sensitive than and equally specific with liquid-based cytology (LBC) in the detection of grade II and above cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2+) (3). As it provides the cytopathologists with a more objective marker for cytology interpretation, it potentially reduces the subjective diversity in cytology interpretations from different cytologists and consequently reduces the reliance of cytology on cytologists’ experiences. This study aimed to demonstrate the performance of P16 immuno-stained cytology (or P16 cytology) in facilitating the differentiation of HSILs from atrophic lesions by comparing the concordance of P16-immuno-stained cytology with the LBC and histopathology diagnoses between the groups of women ≤50 and >50 years of age.

2 Materials and method

2.1 Study design, participants, and procedures

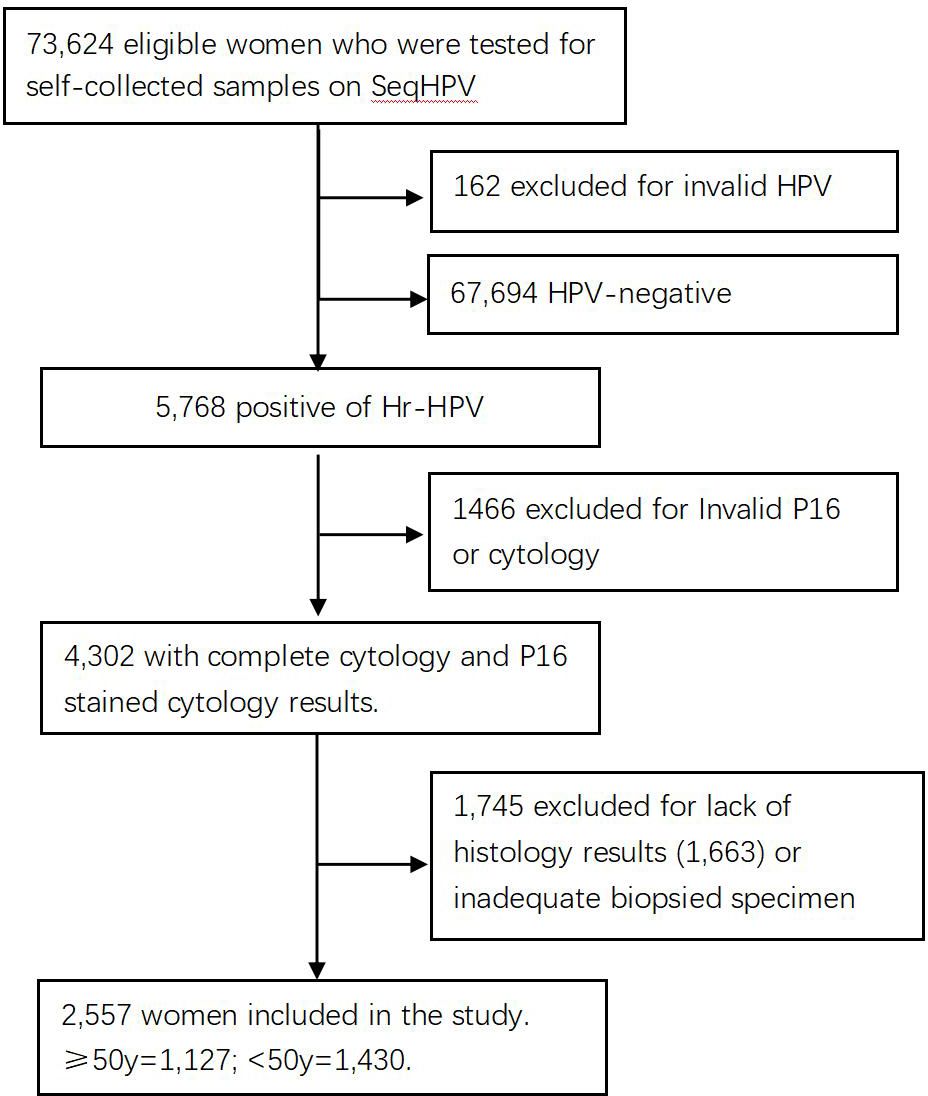

The subjects of the study were 73,624 women living in central China who were screened for cervical cancer by primary HPV testing in a population-based municipal cervical cancer screening program in November 2019. Those women were enrolled for screening because they were eligible: 30–64 years of age, not pregnant, without uterine or cervical resection, and consented to participate in the screening and this study by signing an electronic version of the informed consent form when they registered for participation on a website (www.curekeys.com). Eligible women were primarily tested for hr-HPV with SeqHPV assay on their self-collected samples. Women with HPV-negative results were advised to undergo regular screening by HPV assay after 3 years. Those positive for hr-HPV were recalled back for management following a protocol that required a cervical sample be collected first by the physician for LBC and P16 cytology analysis for all positive women, followed by multiple biopsies on women who were positive for HPV-16 and/or HPV-18, positive for the hr-HPV types other than HPV-16 and HPV-18 (other hr-HPV type) plus positive for acetic acid test, or positive for other hr-HPV types, and negative for acetic acid test but positive for LBC (≥ASCUS). Endocervical curettage (ECC) was performed on patients whose squamocolumnar junction zone (T-zone) could not be completely visible. Pathology analysis was conducted on the biopsies and ECC specimens. Included in this analysis were 2,557 women who had complete data on the primary HPV testing, LBC analysis, P16INK4a immune-stained cytology (P16 cytology) interpretation, and pathology diagnosis. Women who were positive for other hr-HPV types but normal for both LBC and P16 cytology, or positive for any type but did not have results of LBC, P16 cytology, or histopathology, mainly due to sample reasons, were excluded from this study (Figure 1). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of BGI Institute and the Ethics Committee of Peking University Shenzhen Hospital (PUSH, No. 2018035).

2.2 Sampling and HPV testing

After successful registration, which confirmed eligibility for participation in the primary screening, women were screened in the sampling sites temporarily set up in the communities according to the number of registered women in the relevant communities or nearby medical facilities (the screening sites). At the screening site, eligible women were guided to collect cervical/vaginal samples for themselves in sampling rooms by referring to the graphic self-sampling instruction with texts. A conical-shaped brush was used for self-sampling. If any woman had a problem with self-sampling, an on-site medical provider would give personal instruction. The collected sample was applied on an FTA-Illusive-card (GE) for HPV testing on SeqHPV (BGI-Shenzhen) by a reference laboratory of BGI-Shenzhen. SeqHPV is a next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based HPV testing assay that uses multi-plex PRC to amplify DNA and NGS for HPV genotyping (3). This assay can detect and report 14 hr-HPV genotypes, including HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, HPV-39, HPV-45, HPV-51, HPV-52, HPV-56, HPV-58, HPV-59, HPV-66, and HPV-68. SeqHPV had been validated to be equally sensitive and specific with Cobas4800 when tested on either provider-collected or self-collected samples (4) and to work well with FTA cards (a hard sample processing card). It has been licensed by China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) for clinical use.

2.3 LBC and P16INK4a immuno-stained cytology

LBC and the P16INK4a immuno-stained cytology (Senying Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) were used for research purposes and as the secondary screening in the triage of the women who were positive for 12 other types of hr-HPV plus negative for acetic acid test. The cervical sample was collected by the provider and then put into a vial containing cell preservation liquid provided by Senying. The samples were shipped to the Senying laboratory for processing: part of each sample was processed with P16INK4a immunocytochemical stain, and the remaining sample was processed for standard Papanicolaou stains. Both the P16INK4a immuno- and Papanicolaou-stained cytology slides were reviewed and interpreted by two senior cytopathologists who were blinded to each other’s interpretation.

Following The Bethesda System (TBS) classification standards (5), LBC interpretations were reported as negative for squamous intraepithelial lesion (NILM), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), atypical glandular cells (AGC), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), atypical squamous cells-cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H), HSIL, or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) accordingly. P16 cytology positive result was reported when at least one cell was found to have P16INK4a immuno-stained substance in the nucleus or cytoplasm. Quality control was conducted after the two cytopathologists completed their review of the slides, on which all cases with inconsistent interpretations by the cytologists were selected to resolve consistent interpretations via discussions between the two cytopathologists.

2.4 Colpo/biopsy and histopathology diagnostics

For women who needed biopsies according to the protocol for positive management, multiple biopsies were obtained at the site with colposcopically suspected lesions and the opposite sites, or randomly at the squamocolumnar junction zone in four quadrants of the cervix if no lesion was suspected. ECC was performed on patients whose squamocolumnar junction zone could not be completely visible under colposcopy (6).

All the pathology slides were analyzed by a senior pathologist from PUSH who performed pathology analysis for several international clinical trials. Pathology slides were analyzed while blinded to the results from both the P16 cytology and LBC tests. Histological diagnoses for cervical lesions were reported following a two-grade classification system, according to which the cervical lesions were classified as LSIL and HSIL. This system was adopted because many studies demonstrated that different grades of CIN are not the different stages of a cervical lesion development but the two obviously distinguishable pathological processes, and the two-grade classification matches with the bio-behavior of HPV that causes pathology changes in human cells and is with better duplicability (7–9).

2.5 Statistics

Results from LBC and pathology were compared to demonstrate the bias of LBC on the interpretation of HSILs in women ≥50 years of age, and P16 cytology results of the cases with LBC-LSIL and LBC-HSIL were analyzed using the relevant pathology diagnosis as the endpoint (Path-LSIL and Path-HSIL). SPSS 26.0 statistical software was used for data analysis. The chi-square test was used to compare the differences in various rates. Differences in sensitivity and specificity along with 95% CI were calculated using McNemar’s test, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

3 Results

Among the 73,624 primarily screened women, 73,462 had valid results for HPV primary testing after excluding 162 for failure of HPV testing. Of the 73,462, 5,768 were positive for primary HPV testing, and 2,557 of those positive results had complete data of HPV, LBC, P16 cytology, and histopathology results and were included in the analysis for the purpose of this study (the analytic cases). Patients who were primarily positive for 12 other types of hr-HPV but normal in cytology and P16 cytology, or abnormal in the two cytology tests but did not return for colposcopy, were excluded from this analysis.

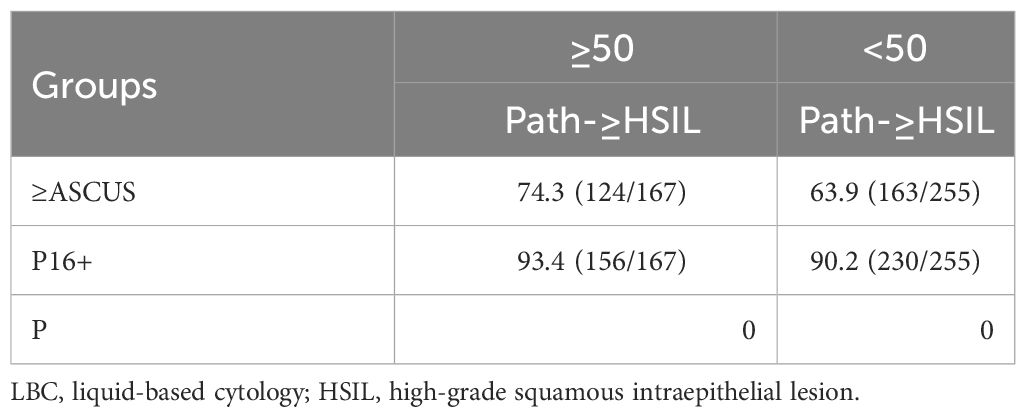

Of the 2,557 analytic cases, 1,430 were younger than 50 years and included in the <50 group, while the remaining 1,127 were aged 50 and above and included in the ≥50 group. HSIL was pathologically confirmed (Path-HSIL) on 255 and 167 positive women in the <50 group and ≥50 group, respectively. When analyzed in age groups with LBC≥ASCUS and P16 cytology positive results as the cutoff, LBC and P16 cytology respectively detected 63.9% (163) and 90.2% (230) of the 255 Path-HSIL cases in the <50 group, while in the ≥50 group, LBC and P16 cytology detected 74.3% (124) and 93.4% (156) of the 167 Path-HSIL cases, respectively (Table 1).

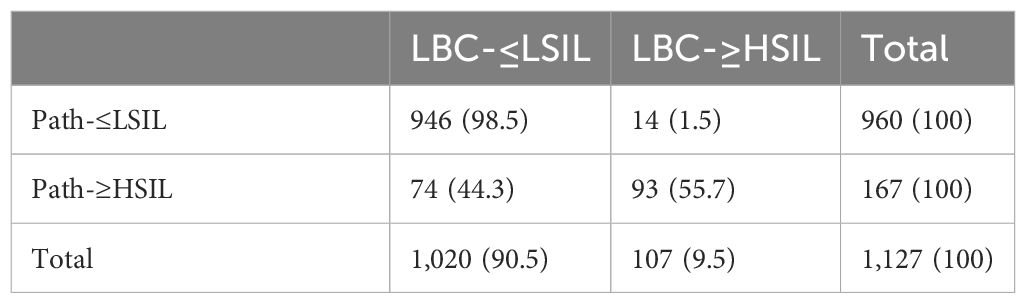

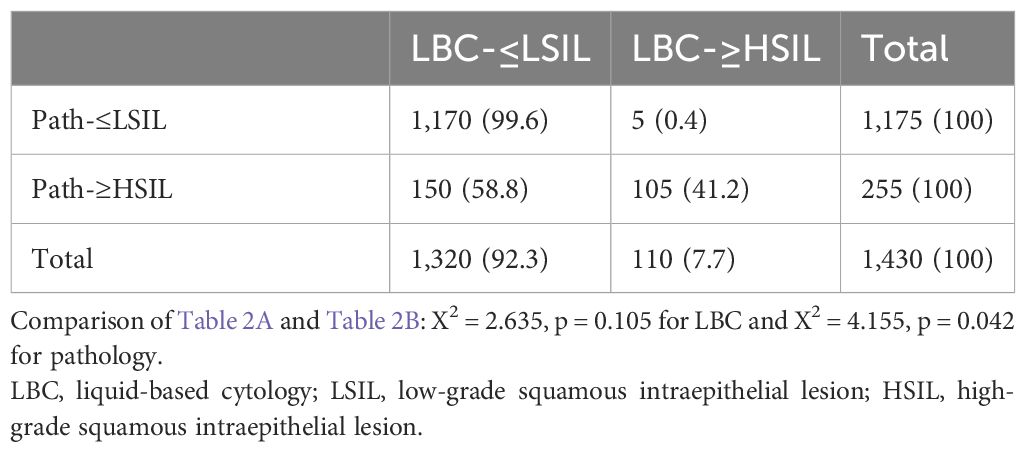

When looking at the number of HSIL cases reported by LBC and pathology, we observed that HSIL from LBC (LBC-HSIL) and pathology (Path-HSIL) in the <50 group were 110 and 255 cases, respectively (Table 2A), while LBC- and Path-HSIL in the ≥50 group were 107 and 167 cases, respectively (Table 2B). However, when looking at the concordance of LBC and pathology detecting HSIL, we found that LBC matched with pathology in 41.2% (105/255) of the HSIL cases from the <50 age group and 55.7% (93/167) of such cases from the ≥50 group.

What interested us were the five (0.4%) and 14 (1.5%) Path-≤LSIL cases in the <50 and ≥50 groups, respectively, that were reported by LBC as HSIL cases (LBC-HSIL/Path-≤LSIL cases), with significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.042). Further analysis showed that all the five LBC-HSIL/Path-≤LSIL cases in the <50 group and 14 such cases in the ≥50 group were negative for P16 cytology, of which the five from the <50 group and 13 from the ≥50 group were pathologically confirmed as normal, and one from the ≥50 group was Path-LSIL (Table 3). These results indicate that P16 cytology is contributive in differentiating benign lesions from HSIL for cytology (LBC) on women ≥50 years of age.

Table 3 also shows that there were one and three LBC-HSIL/Path-HSIL cases in the <50 and ≥50 groups, respectively, that were negative for P16 cytology. All those cases were pathologically graded as CIN2.

4 Discussion

Our prior study has demonstrated that P16 cytology is better than LBC in the sensitivity and specificity for the detection of CIN2+ (10) but less dependent on cell morphology, which makes it more applicable in lower-resource areas where experienced and acknowledgeable cytologists are insufficient. In this study, we found that P16 cytology is advantageous in facilitating cytologists to differentiate benign lesions from LBC-≥HSIL in women ≥50 years of age. Due to obvious decreased levels of estrogen in women during perimenopause, some atrophic cervical cells are usually included in the cervical samples for cytology, resulting in its potential misinterpretation as HSIL (11). As the atrophic cells have smaller portions of cytoplasm, it is easy to be confused with HSIL cells on Papanicolaou-stained cytology slides, and this has always been challenging to cytologists, especially to the inexperienced ones in lower-resource regions.

Our analysis shows that the rate of LBC-reported false HSILs is significantly higher in the ≥50 group than in the <50 group. This result is consistent with many studies that reported that among the cases that returned for colposcopy/biopsies for LBC-≥HSIL, the average age of the cases’ normal pathology was higher than those pathologically diagnosed as HSIL (12–14). In a study on LBC-ASC-H cases (15), Halford and coauthors reported that the rates of CIN2 were 55.8% and 37.5% among patients aged <50 and ≥50 years, respectively, with significant differences. Other studies attributed the higher rate of inconsistency between LBC-HSIL and Path-Normal among women aged ≥50 years to cervical atrophic changes caused by the drop in estrogen levels, which often led to many parabasal cells and basal cells being stained dark on cytology views (16–18). LBC may possibly misinterpret cervical atrophic cells as HSIL or even cancer (19). The atrophy changes on squamous epithelium make the Papanicolaou test less precise and specific in the detection of HSIL (20, 21). Recent studies found that P16/Ki67 double-stained cytology performed high profiles for CIN2+ in postmenopausal women cytologically reported with ASCUS (22). Since misinterpretation of atrophic cells as HSIL+ would not only bring heavy psychological pressure to women but also lead to unnecessary biopsies, the performance of P16 immunocytochemical stain in the facilitation of the interpretation of cytology for women aged 50 or above is worth addressing for its clinical application.

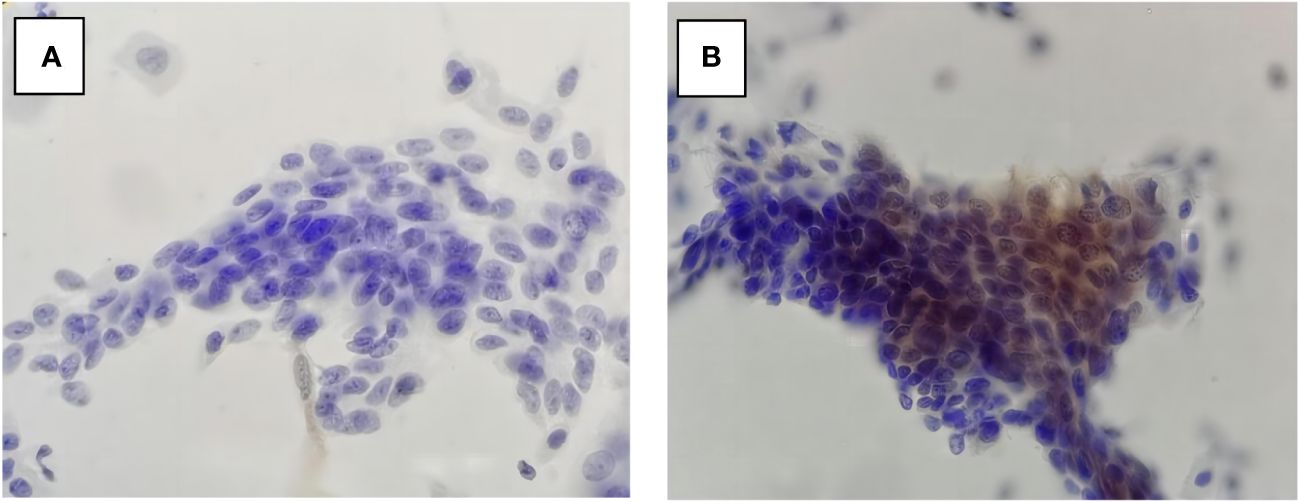

In our study, P16INK4a-stained cytology (P16 cytology) performs well in differentiating Path-≤LSIL from LBC-≥HSIL (Figure 2). Those findings are important for further studies and clinic services since P16 cytology helps avoid the atrophic changes of the cervical cells from aged women being misinterpreted as ≥HSIL by LBC. P16-immuno-stain also contributes to the indication of the invisible HSIL+ under colposcopy (23). In our study, all the LBC-≥HSIL cases that were also positive for P16 were pathologically diagnosed as ≥HSIL. Further analysis of the four Path-≥HSIL cases that were negative for P16 showed that all of them were pathologically graded as CIN2. We do not have data to confirm whether P16 negative results in those cases are potentially caused by hypermethylation (24, 25) or a regressive tendency of those CIN2 cases. The persistence of HPV infections also should be given great importance, as it is related to the persistence and recurrence of HSIL (26, 27). Further study is needed to answer those questions. The findings in our study suggest that P16 immuno-stain can play an important role in avoiding either overdiagnosis or misdiagnosis. For many years, investigators have endorsed finding proper technology for secondary screening that can keep enough sensitivity for the detection of HSIL but avoid unnecessary biopsies.

Figure 2 P16 cytology in LBC-≥HSIL/Path-≤LSIL (A) and LBC-≥HSIL/Path-≥HSIL (B). LBC, liquid-based cytology; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Our previous studies demonstrated that the detection rate of P16 cytology is as same as that of HPV testing and LBC analysis for Path-HSIL and above and can be used as the secondary screening test for positive women after primary HPV screening (28). Those studies also indicated that P16 cytology as well as cytology can find abnormal cells that may potentially progress to carcinomas and is better than HPV testing in indicating precancer (29). P16 cytology can be tested at the same time with LBC on the same sample and is advantageous as the secondary screening after primary hr-HPV testing in improving the accuracy of cytology analysis (30). Our analysis in this study further demonstrated the important advantage of P16 cytology in facilitating cytologists to differentiate atrophic changes from HSIL.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that P16 cytology facilitates differentiation of Path-≤LSIL from LBC-≥HSIL for women 50 years of age and above. It can be used in the lower-resource areas where qualified cytologists are insufficient as the secondary screening test for women aged ≥50 to avoid unnecessary biopsies and misinterpretation of LBC primary or secondary screening.

This study is one of the few retrospective studies on triage in women with LBC-≥HSIL with P16INK4a immunocytochemical stain. It contributes a basis for further studies in the relevant area. However, our study has limitations: patients were grouped by age rather than by menstruation status; thus, there is a lack of proof for the histological atrophy changes. It could be more evident if the LBC and P16 cytology results were from primary screening.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Ethics Committee from Peking University Shenzhen Hospital (No.2018035). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. HD: Writing – review & editing. CW: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Resources, Supervision. FS: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XQ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Shenzhen High-level Hospital Construction Fund (YBH2019–260), the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (No.SZSM202011016), and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Project (GJHZ20210705142543018).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Waddell CA. The influence of the cervix on smear quality. I: Atrophy. An audit of cervical smears taken post-colposcopic management of intraepithelial neoplasia. Cytopathology. (1997) 8:274–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.1997.8382083.x

2. Hu H, Zhao J, Yu W, Zhao JW, Wang Z, Lin J, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA HPV L1 capsid protein and p16INK4a protein as markers to predict cervical lesion progression. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2019) 299:141–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4931-1

3. Belinson JL, Wang G, Qu X, Du H, Shen J, Xu J, et al. The development and evaluation of a community based model for cervical cancer screening based on selfsampling, Gynecol. Oncol. (2014) 132:636–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.006

4. Du H, Duan X, Liu Y, Shi B, Zhang W, Wang C, et al. Evaluation of cobas HPV and SeqHPV assays in the chinese multicenter screening trial. J Low Genit. Tract. Dis. (2021) 25:22–6. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000577

5. Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O'Connor D, Prey M, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. (2002) 287:2114–2119. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114

6. Belinson JL, Pretorius RG. A standard protocol for the colposcopy exam. J Low Genit Tract Dis. (2016) 20:e61⁃e62. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000239

7. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Thomas Cox J, Heller DS, Henry MR, Luff RD, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for hpv-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the college of american pathologists and the american society for colposcopy and cervical pathology. Int J Gynecol Pathol. (2013) 32:76–115. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31829c681b

8. Stoler MH. New Bethesda terminology and evidence-based management guidelines for cervical cytology findings. JAMA. (2002) 287:2140–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2140

9. Quddus MR, Sung CJ, Steinhoff MM, Lauchlan SC, Singer DB, Hutchinson ML. Atypical squamous metaplastic cells: reproducibility, outcome, and diagnostic features on ThinPrep Pap test. Cancer. (2001) 93:16–22. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010225)93:1<16::aid-cncr9002>3.0.co;2-a

10. Song F, Du H, Xiao A, Wang C, Huang X, Yan PS, et al. Application value of p16INK4a immunocytochemical staining in cervical cancer screening. Chin J Obstetrics Gynecology. (2020) 55:784–90. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112141-20200520-00428

11. Yan P, Du H, Wang C, Song F, Huang X, Luo Y, et al. Differential diagnosis of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions and benign atrophy in older women using p16 immunocytochemistry. Gynecology Obstetrics Clin Med. (2021) 1:14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gocm.2020.10.005

12. Saad RS, Dabbs DJ, Kordunsky L, Kanbour-Shakir A, Silverman JF, Liu Y, et al. Clinical significance of cytologic diagnosis of atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high grade, in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Pathol. (2006) 126:381–8. doi: 10.1309/XVB01JQYQNM7MJXU

13. Sherman ME, Solomon D, Schiffman M. Qualification of ASCUS. A comparison of equivocal LSIL and equivocal HSIL cervical cytology in the ASC-US LSIL Triage Study. Am J Clin Pathol. (2001) 116:386–94. doi: 10.1309/JM3V-U4HP-W8HJ-68XV

14. Srodon M, Parry Dilworth H, Ronnett BM. Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion: diagnostic performance, human papillomavirus testing, and follow-up results. Cancer. (2006) 108:32–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21388

15. Halford J, Walker KA, Duhig J. A review of histological outcomes from peri-menopausal and postmenopausal women with a cytological report of possible high grade abnormality: an alternative management strategy for these women. Pathology. (2010) 42:23–7. doi: 10.3109/00313020903434363

16. Patton AL, Duncan L, Bloom L, Phaneuf G, Zafar N. Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude a high-grade intraepithelial lesion and its clinical significance in postmenopausal, pregnant, postpartum, and contraceptive-use patients. Cancer. (2008) 114:481–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23949

17. Onuma K, Saad RS, Kanbour-Shakir A, Kanbour AI, Dabbs DJ. Clinical implications of the diagnosis “atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion” in pregnant women. Cancer. (2006) 108:282–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22170

18. Li Y, Shoyele O, Shidham VB. Pattern of cervical biopsy results in cases with cervical cytology interpreted as higher than low grade in the background with atrophic cellular changes. CytoJournal. (2020) 17:12. doi: 10.25259/Cytojournal_82_2019

19. Davey DD, Greenspan DL, Kurtycz DF, Husain M, Austin RM. Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion: Review of ancillary testing modalities and implications for follow-up. J Low Genit Tract Dis. (2010) 14:206–14. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3181ca66a6

20. Wikstrom I, Stenvall H, Wilander E. Low prevalence of high-risk HPV in older women not attending organized cytological screening: A pilot study. Acta Derm. Venereol. (2007) 87:554–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0326

21. Michiyasu M, Yoshihiro I, Hiroshi T, Iwata A, Tsukamoto T, Nomura H, et al. Lower accuracy of cytological screening for high-grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasia in women over 50 years of age in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. (2022) 27:427–33. doi: 10.1007/s10147-021-02065-w

22. Yang B, Pretorius RG, Belinson JL, Zhang X, Burchette R, Qiao Y-L. False negative colposcopy is associated with thinner cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 and 3. Gynecol Oncol. (2008) 110:32–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.03.003

23. Rokutan-Kurata M, Minamiguchi S, Kataoka TR, Abiko K, Mandai M, Haga H. Uterine cervical squamous cell carcinoma without p16(CDKN2A) expression: Heterogeneous causes of anunusual immunophenotype. Pathol Int. (2020) 70:413–21. doi: 10.1111/pin.12930

24. Vink FJ, Dick S, Heideman DAM, De Strooper LMA, Steenbergen RDM, Lissenberg-Witte BI, et al. Classification of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia by p16ink4a, Ki-67, HPV E4 and FAM19A4/miR124–2 methylation status demonstrates considerable heterogeneity with potential consequences for management. Int J Cancer. (2021) 149:707–16. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33566

25. Bogani G, Sopracordevoleb F, Ciavattini A, De Strooper LMA, Steenbergen RDM, Lissenberg-Witte BI, et al. Duration of human papillomavirus persistence and its relationship with recurrent cervical dysplasia. Eur J Cancer Prev. (2023) 32:525–32. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000822

26. Bogani G, Sopracordevole F, Ciavattiniel A, Vizza E, Vercellini P, Ghezzi F, et al. HPV persistence after cervical surgical excision of high-grade cervical lesions. Cancer Cytopathol. (2024) 132(5):268–9. doi: 10.1002/cncy.22760

27. Pretorius RG, Kim RJ, Belinson JL, Elson P, Qiao Y-L. Inflation of sensitivity of cervical cancer screening tests secondary to correlated error in colposcopy. J Lower Genital Tract Dis. (2006) 10:5–9. doi: 10.1097/01.lgt.0000192694.85549.3d

28. Duan LF, Du H, Xiao A, Wang C, Yan PS, Huang X, et al. Value of cytology p16INK4a in early diagnosis of cervical cancer. Chin J Pathol. (2020) 49:812–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20191203-00779

29. Song F, Belinson JL, Yan P, Huang X, Wang C, Du H, et al. Evaluation of p16INK4a immunocytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping triage after primary HPV cervical cancer screening on self-samples in China. Gynecologic Oncol. (2021) 162:322–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.05.014

Keywords: P16 immunocytochemical stain, atrophy, cytology, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), menopause

Citation: Hou J, Du H, Wang C, Song F, Qu X and Wu R (2024) Performance of P16INK4a immunocytochemical stain in facilitating cytology interpretation of HSIL for HPV-positive women aged 50 and above. Front. Oncol. 14:1332172. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1332172

Received: 02 November 2023; Accepted: 08 May 2024;

Published: 28 May 2024.

Edited by:

Songlin Zhang, Baylor College of Medicine, United StatesReviewed by:

Mirella Fortunato, Azienda Sanitaria Ospedaliera S.Croce e Carle Cuneo, ItalyIlaria Cuccu, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Bhagyalaxmi Nayak, Acharya Harihar Post Graduate Institute of Cancer, India

Copyright © 2024 Hou, Du, Wang, Song, Qu and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinfeng Qu, c3RldmUxMDA1QGljbG91ZC5jb20=; Ruifang Wu, d3VyZnB1c2hAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Jun Hou

Jun Hou Hui Du1,2,3

Hui Du1,2,3 Fangbin Song

Fangbin Song Xinfeng Qu

Xinfeng Qu Ruifang Wu

Ruifang Wu