95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 02 June 2023

Sec. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention

Volume 13 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1166580

This article is part of the Research Topic Effectiveness And Mechanisms of Acupuncture For Chronic Pain Management: From Bench to Bedside View all 6 articles

Background: Pain is one of the most common and troublesome symptoms of cancer. Although potential positive effects of acupuncture-point stimulation (APS) on cancer pain have been observed, knowledge regarding the selection of the optimal APS remains unclear because of a lack of evidence from head-to-head randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Objective: This study aimed to carry out a network meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of different APS combined with opioids in treating moderate to severe cancer pain and rank these methods for practical consideration.

Methods: A comprehensive search of eight electronic databases was conducted to obtain RCTs involving different APS combined with opioids for moderate to severe cancer pain. Data were screened and extracted independently using predesigned forms. The quality of RCTs was appraised with the Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias tool. The primary outcome was the total pain relief rate. Secondary outcomes were the total incidence of adverse reactions, the incidence of nausea and vomiting, and the incidence of constipation. We applied a frequentist, fixed-effect network meta-analysis model to pool effect sizes across trials using rate ratios (RR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Network meta-analysis was performed using Stata/SE 16.0.

Results: We included 48 RCTs, which consisted of 4,026 patients, and investigated nine interventions. A network meta-analysis showed that a combination of APS and opioids was superior in relieving moderate to severe cancer pain and reducing the incidence of adverse reactions such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation compared to opioids alone. The ranking of total pain relief rates was as follows: fire needle (surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) = 91.1%), body acupuncture (SUCRA = 85.0%), point embedding (SUCRA = 67.7%), auricular acupuncture (SUCRA = 53.8%), moxibustion (SUCRA = 41.9%), transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation (TEAS) (SUCRA = 39.0%), electroacupuncture (SUCRA = 37.4%), and wrist–ankle acupuncture (SUCRA = 34.1%). The ranking of total incidence of adverse reactions was as follows: auricular acupuncture (SUCRA = 23.3%), electroacupuncture (SUCRA = 25.1%), fire needle (SUCRA = 27.2%), point embedding (SUCRA = 42.6%), moxibustion (SUCRA = 48.2%), body acupuncture (SUCRA = 49.8%), wrist–ankle acupuncture (SUCRA = 57.8%), TEAS (SUCRA = 76.3%), and opioids alone (SUCRA = 99.7%).

Conclusions: APS seemed to be effective in relieving cancer pain and reducing opioid-related adverse reactions. Fire needle combined with opioids may be a promising intervention to reduce moderate to severe cancer pain as well as reduce opioid-related adverse reactions. However, the evidence was not conclusive. More high-quality trials investigating the stability of evidence levels of different interventions on cancer pain must be conducted.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/#searchadvanced, identifier CRD42022362054.

Cancer is the world’s second leading cause of death, and its incidence rate increased yearly due to population aging and unhealthy lifestyle. Global cancer cases are estimated to reach 28.4 million by 2040, which is a 47% increase over 2020 (1). Pain is one of the most common and intractable symptoms of cancer caused by tumors or antitumor treatments and can occur at various stages of tumors. This is an important reason for patients to have their life quality decreased and to lose their confidence in treatment (2). According to statistics, about 40% of early to intermediate cancer patients and 90% of terminal cancer patients have suffered from moderate to severe cancer pain, of which 70% have not been effectively controlled (3). Opioids are the primary drugs used to treat moderate to severe cancer pain, but up to two-thirds of cancer patients reported inadequate pain management (4). Moreover, opioids may cause unexpected side effects, including nausea, vomiting, constipation, sedation, and cognitive impairment. Due to their inability to tolerate these adverse events, 10% to 20% of patients stop taking drugs (2).

In order to relieve cancer pain and reduce the demand for painkillers, various nondrug methods have been adopted, including acupuncture-point stimulation (APS), educational intervention, and relaxation. APS has been considered a promising alternative analgesia (5). In recent years, APS analgesia has been widely studied and generally recognized as safe, effective, and easy to operate with few adverse reactions (6–8). The role of APS in controlling cancer pain has been gradually verified (9, 10). Apart from relieving pain, APS could also help relieve fatigue and improve the quality of life for patients receiving palliative treatment (11). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Adult Cancer Pain Guidelines have included acupuncture as a comprehensive intervention for cancer pain (2).

However, APS is diverse and has different therapeutic advantages (12, 13). Existing original studies and meta-analyses mostly compare APS combined with opioid therapy and opioids alone, lacking comparison among different APS methods in opioid-used situations. Therefore, this study used network meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of different APS therapies in treating cancer pain. These outcome indexes were ranked quantitatively to find the best intervention for patients with moderate to severe cancer pain, which can provide evidence for selection prescription and medical decision-making.

Four English-language databases (PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) and four Chinese-language databases (Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals, Wan Fang) were searched from the inception date to 30 June 2022. The search strategy consisted of three components: population (“cancer,” “tumor/tumor,” “carcinoma,” “neoplasm,” “pain,” “analgesia”), interventions (“acupuncture,” “electroacupuncture,” “manual acupuncture,” “moxibustion,” “point embedding,” “transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation,” “auricular point,” “thumb-tack acupuncture,” “wrist-ankle acupuncture,” “warm acupuncture”), and study type (“randomized clinical trial”). Existing systematic reviews were examined to identify additional trials. There were no restrictions on languages. Details of the search strategy are listed in Supplementary Data 1.

Studies were included if they matched the following criteria: (1) Study type: randomized controlled trial, RCT. (2) Population: meet the diagnostic criteria of cancer pain (2); gender, race, and type of cancer are not limited. (3) Interventions: the control group was treated with opioids recommended by the WHO (combined with a placebo). On the basis of the control group, the experimental group was combined with APS therapy (filiform acupuncture, electroacupuncture, fire acupuncture, moxibustion, acupoint application, massage, and auricular acupuncture), and each therapy needs to be supported by sufficient research data (including RCTs ≥ 3, participants in each group ≥ 30). (4) Outcomes: at least one outcome measure. The primary outcome was the total pain relief rate. The main reference criteria were as follows (14): the cases of patients with partial relief or above (≥ 50%) or with marked effect or above were regarded as effective cases (i.e., the pain was tolerable and did not affect normal life or sleep). The safety outcomes were the incidence of adverse reactions (i.e., nausea/vomiting, constipation). We recorded the outcomes as close to 2 weeks as possible for all analyses. If the information at 2 weeks was not available, we used data ranging between 1 and 4 weeks and gave preference to the timepoint closest to 2 weeks. If time points were equidistant (i.e., 1 and 3 weeks), we took the longer outcome (3 weeks).

(1) Studies with more than two APS methods combined interventions. (2) Studies on nonrandomized controlled trials or unbalanced baseline data between groups. (3) Studies with outcomes that cannot fit the design of this study. (4) Studies in which the data cannot be integrated, such as incorrect data or incomplete information. (5) Repeatedly published studies: only include one with the most complete data.

All records found were imported into EndNote X9 to eliminate duplicate studies. Two independent reviewers (Q.L. Z. and Y.T. Y.) screened all titles and abstracts. Full-text articles of studies identified as potentially relevant were obtained and assessed by two independent reviewers according to the inclusion criteria. Only studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected for the systematic review and data extraction for network meta-analysis evaluation. Data were extracted from the included studies, including author name, published year, sample size, age, methods and duration of intervention, total pain relief rate, and adverse reactions. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion or through adjudication by a third investigator (L. F.).

Two researchers (Q.L. Z. and Y.T. Y.) evaluated the risk of bias in each study based on the criteria of the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (15). The quality evaluation items of each study included selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective reporting), and other biases. These items were scored as low, high, or unclear risk of bias. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

All analyses were performed using a network suite of commands in Stata/SE (version 16.0). The network package performed the network meta-analysis based on the frequentist framework (16). Firstly, network plots were drawn to show the quantitative relationship between various interventions. When it could form a closed loop, inconsistencies were detected. Statistical heterogeneity was investigated with the I2 statistics and predefined heterogeneity (I2 = 0 indicates that the inconsistency of the results makes no statistical difference, I2 ≤ 50% for low and I2 > 50% for high). If I² ≤ 50%, a fixed-effects model was used; otherwise, a random-effects model was used. Next, the rate ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to estimate the effect size. The results of the network meta-analysis were summarized based on all possible pairwise comparisons, including mixed comparisons and indirect comparisons. The effect of different interventions was estimated based on the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA), which ranged from 0% to 100%. Synthetic sorting bubble diagrams based on the SUCRA value were drawn to comprehensively present the relatively better interventions in this Network Meta-Analysis (NMA). Finally, funnel plots were drawn to evaluate the publication bias and small samples of the included studies.

This review was conducted according to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (17, 18). The protocol for this study was registered in the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The protocol registration ID is CRD42022362054.

We identified 6,196 studies from the databases and trial registries and selected 97 possible eligible citations for full-text review. After excluding 49 studies, 48 trials met the inclusion criteria. The process of study search, screening, and selection is shown in Figure 1. These studies were all conducted in China, published between 2000 and 2022, and included a total of 4,026 patients (2,012 patients in the experiment group and 2,014 patients in the control group). All studies were two-arm studies with opioids as the intervention measures in the control group and APS combined with opioids in the experiment group.

Eight types of APS were reported among all trials. The main treatments were body acupuncture combined with opioids (19–30), moxibustion combined with opioids (31–38), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (39–43), auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (44–51), point embedding combined with opioids (52–54), transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation (TEAS) combined with opioids (55–60), wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids (61–63), and fire needle combined with opioids (64–67). The number of research reporting pain relief was 45, while 29 studies mentioned treatment and painkiller-related adverse reactions (Supplementary Data 2).

Regarding the random sequence generation method, 30 studies used a random number list, two used simple randomization, and one used drawing lots to divide groups, which was evaluated as low risk. In total, 13 studies did not mention the specific randomization and were rated as unknown risks. Two studies were randomly assigned to the patient’s sequence of entry into the hospital and were classified as high-risk. All studies that did not mention allocation concealment were rated as unknown risks. All experimental groups were treated with APS on the basis of the control group. Although the blind method was mentioned in one study, it could not achieve blinding for the implementers and was rated as high risk. One study mentioned using blind methods for evaluators and statistical analysts and was rated as low risk, while other studies did not mention it and were all rated as unknown risks. All studies had complete data, so the attrition bias was evaluated as low risk. The proposals for all studies were not available and were rated as unknown risks. Other biases were unknown risks because there were no available details to evaluate (Supplementary Figure S1). Details of the risk of bias items across all included studies are listed in Supplementary Figure S2.

No closed loop was formed in these outcomes, so the consistency model was directly selected. The heterogeneity of all outcome indicators was small at the overall level (I² < 50%), and the fixed-effect model was used for analysis.

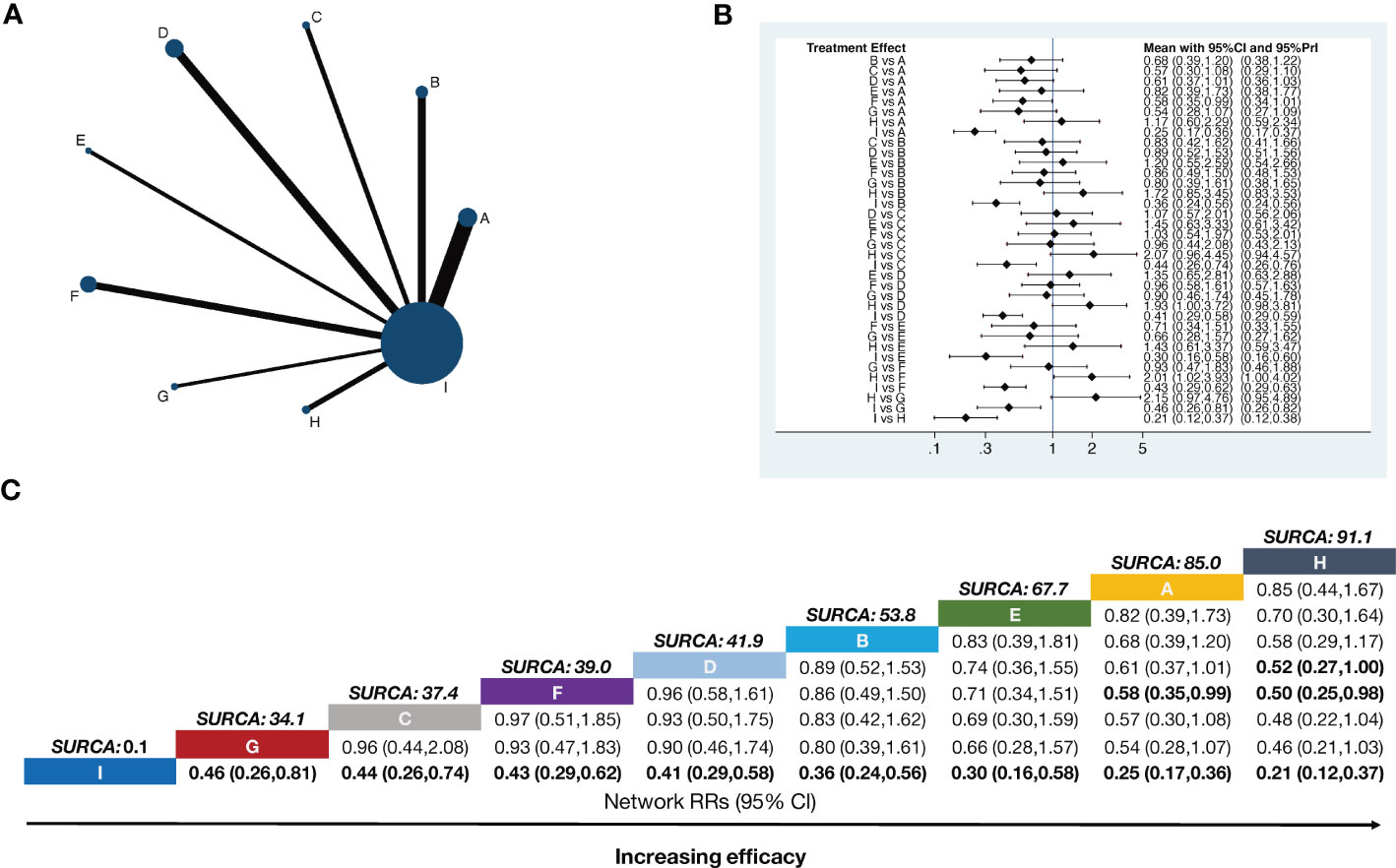

A total of 45 two-arm studies referred to the total pain relief rate involving eight APS therapies. There were 11 studies on body acupuncture combined with opioids, six studies on moxibustion combined with opioids, four studies on electroacupuncture combined with opioids, eight studies on auricular acupuncture combined with opioids, three studies on point embedding combined with opioids, six studies on TEAS combined with opioids, three studies on wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids, and four studies on fire needle combined with opioids. Using opioids as the comparison, eight pairs of direct comparisons were generated, and no closed loop was formed. A network of comparisons between interventions is shown in Figure 2A.

Figure 2 Network meta-analysis of total pain relief rate. The bold font indicates a statistically significant difference between the two treatments. (A) Network plot showing comparisons in efficacy between nodes (blue circles), each representing a unique intervention. Each node’s size is proportional to the total number of randomly assigned participants receiving the treatment. The width of each connecting line is proportional to the number of trial-level comparisons between the two nodes. (B) Forest plot of the network meta-analysis comparing the efficacy of each treatment. (C) Schematic detailing the most efficacious treatments according to the surface under the cumulative ranking curve analysis (SUCRA). A, Body acupuncture combined with opioids; B, moxibustion combined with opioids; C, electroacupuncture combined with opioids; D, auricular acupuncture combined with opioids; E, point embedding combined with opioids; F, TEAS combined with opioids; G, wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids; H, fire needle combined with opioids; I, opioids.

Compared with opioids alone, body acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 0.25, 95% CI [0.17–0.36]), moxibustion combined with opioids (RR = 0.36, 95% CI [0.24–0.56]), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 0.44, 95% CI [0.26–0.74]), auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 0.41, 95% CI [0.29–0.58]), point embedding combined with opioids (RR =0.30, 95% CI [0.16–0.58]), TEAS combined with opioids (RR = 0.43, 95% CI [0.29–0.62]), wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 0.46, 95% CI [0.26–0.81]), and fire needle combined with opioids (RR = 0.21, 95% CI [0.12–0.37]) could improve the total pain relief rate and make the difference between groups statistically significant. Body acupuncture (RR = 0.58, 95% CI [0.35–0.99]) and auricular acupuncture (RR = 0.50, 95% CI [0.25–0.98]) showed a more practical function than TEAS in relieving pain, all of them happened in opioid-used situation. The RR values are shown in Figure 2B.

The SUCRA rank and probability value results indicated that fire needle combined with opioids (91.1%) was most likely to improve the pain relief rate, followed by body acupuncture combined with opioids (85.0%), point embedding combined with opioids (67.7%), auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (53.8%), moxibustion combined with opioids (41.9%), TEAS combined with opioids (39.0%), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (37.4%), wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids (34.1%), and opioids alone (0.1%) (Figure 2C).

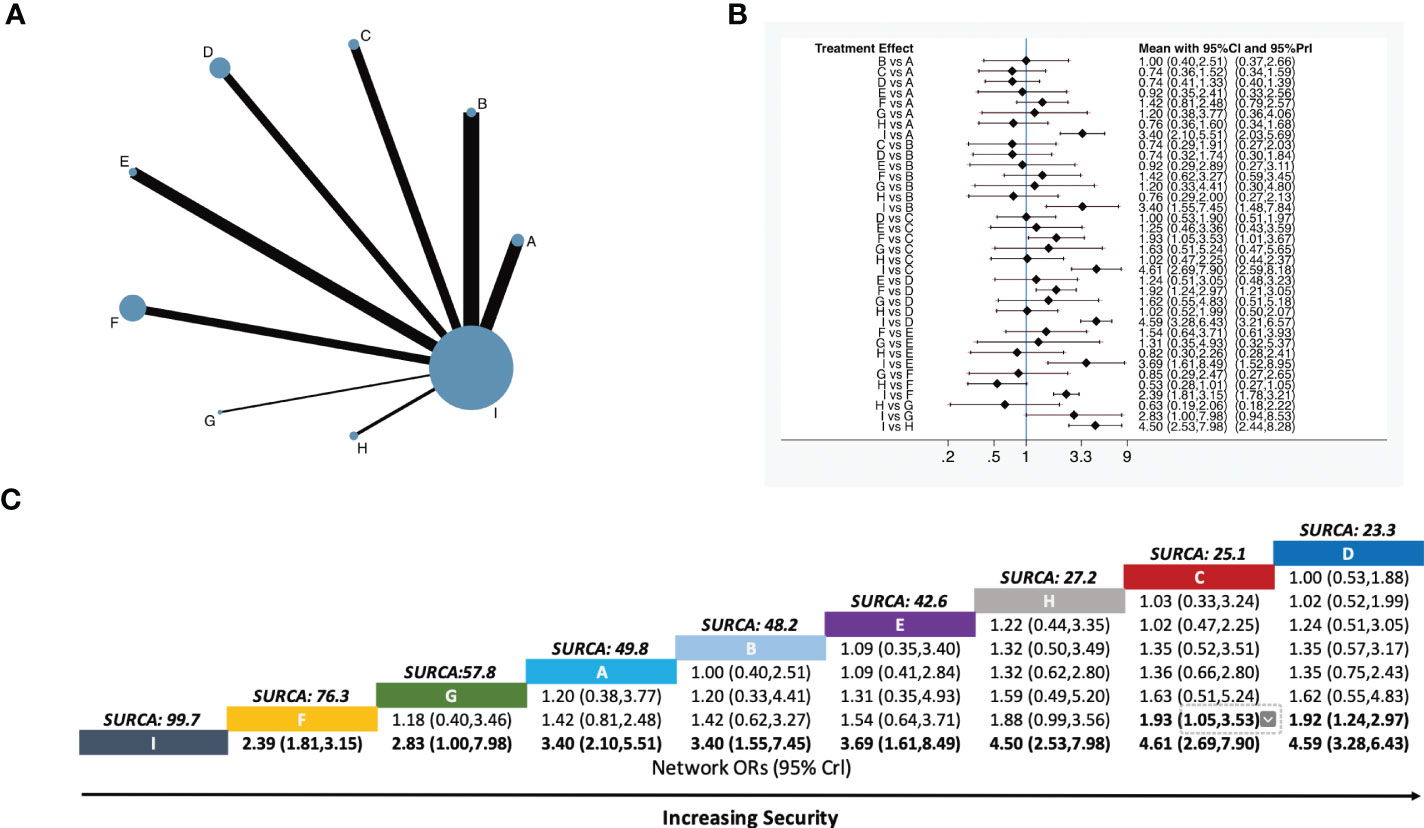

The occurrence of adverse reactions was noted in 29 studies, making up eight pairs of direct comparisons. The adverse reactions mainly include dizziness, headache, dysuria, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, poor appetite, and drowsiness. There were six studies on body acupuncture combined with opioids, four studies on moxibustion combined with opioids, four studies on electroacupuncture combined with opioids, four studies on auricular acupuncture combined with opioids, three studies on point embedding combined with opioids, five studies on TEAS combined with opioids, one study on wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids, and two studies on fire needle combined with opioids. No closed loop was formed in terms of safety outcome indicators. The network diagram is shown in Figure 3A.

Figure 3 Network meta-analysis of total incidence of the adverse reactions. (A) Network plot showing comparisons in security between each intervention. (B) Forest plot of the network meta-analysis comparing the security of each treatment. (C) Schematic detailing the safest treatments according to the surface under the cumulative ranking curve analysis (SUCRA). A, Body acupuncture combined with opioids; B, moxibustion combined with opioids; C, electroacupuncture combined with opioids; D, auricular acupuncture combined with opioids; E, point embedding combined with opioids; F, TEAS combined with opioids; G, wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids; H, fire needle combined with opioids; I, opioids.

Eight-pair comparisons were generated among the nine interventions. Compared with opioids alone, body acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 3.40, 95% CI [2.10–5.51]), moxibustion combined with opioids (RR = 3.40, 95% CI [1.55–7.45]), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 4.61 95% CI [2.69–7.90]), auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 4.59, 95% CI [3.28–6.43]), point embedding combined with opioids (RR = 3.69, 95% CI [1.61–8.49]), TEAS combined with opioids (RR = 2.39, 95% CI [1.81–3.15]), wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 2.83, 95% CI [1.00–7.98]), and fire needle combined with opioids (RR = 4.50, 95% CI [2.53–7.98]) were safer in the total incidence of adverse reactions and made the difference between groups statistically significant. Compared with TEAS combined with opioids, auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 1.92, 95% CI [1.24–2.97]) and electroacupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 1.93 95% CI [1.05–3.53]) were found to be safer in treatment of moderate to severe cancer pain (Figure 3B).

Based on SUCRA values, the ranking of nine interventions was as follows: auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (23.3%), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (25.1%), fire needle combined with opioids (27.2%), point embedding combined with opioids (42.6%), moxibustion combined with opioids (48.2%), body acupuncture combined with opioids (49.8%), wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids (57.8%), TEAS combined with opioids (76.3%), and opioids alone (99.7%). Specific values are shown in Figure 3C.

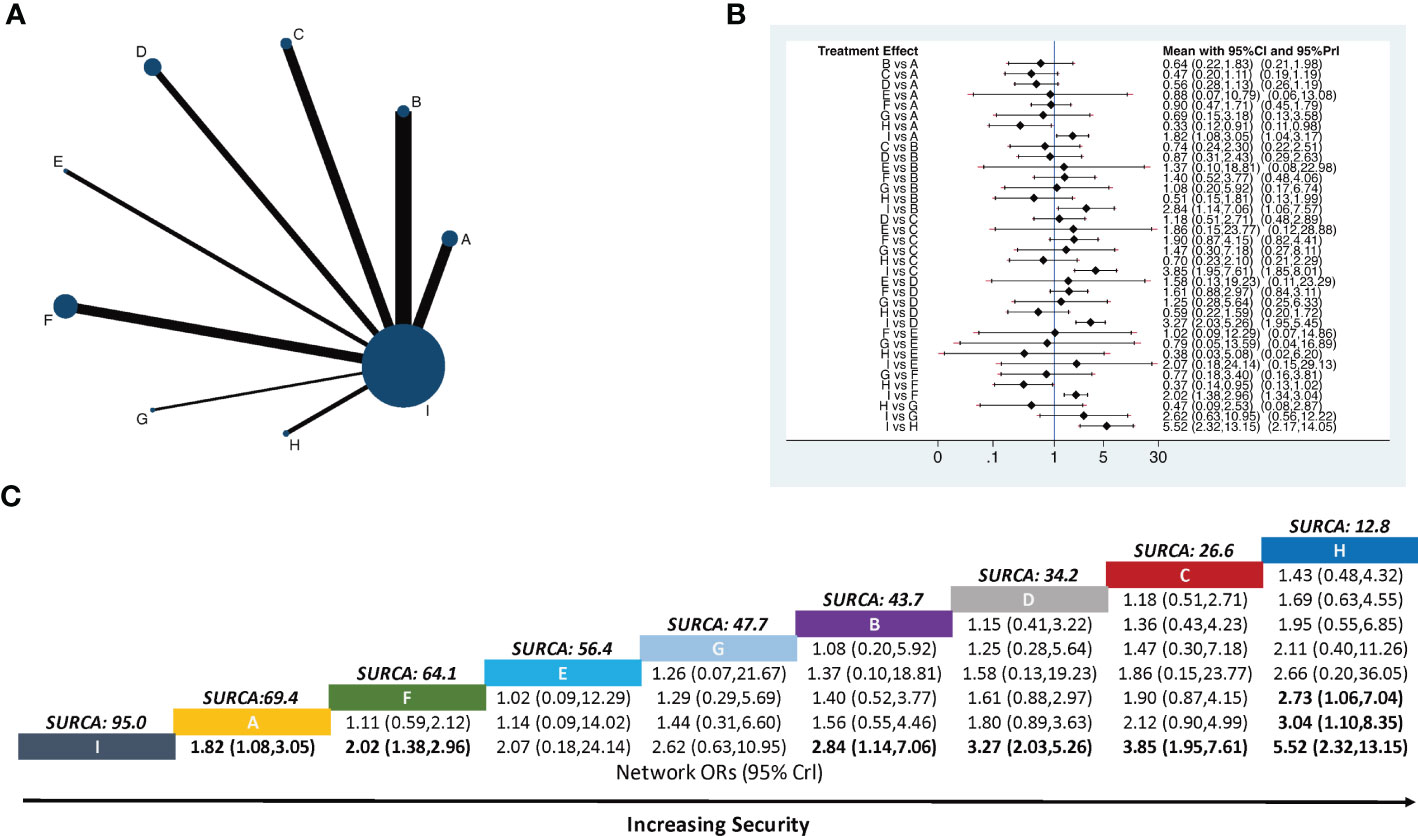

Nine therapies were described in 26 studies that included the number of patients with nausea and vomiting (Figure 4A). For nausea and vomiting incidence, the pairwise meta-analysis comparing each intervention against opioids revealed that fire needle combined with opioids (RR = 5.52, 95% CI [2.32–13.15]), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 3.85, 95% CI [1.95–7.61]), auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 3.27, 95% CI [2.03–5.26]), moxibustion combined with opioids (RR = 2.84, 95% CI [1.14–7.06]), TEAS combined with opioids (RR = 2.02, 95% CI [1.38–2.96]), and body acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 1.82, 95% CI [1.08–3.05]) were significantly superior to opioids alone. Body acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 3.04, 95% CI [1.10–8.35]) and TEAS combined with opioids (RR = 2.73, 95% CI [1.06–7.04]) had a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting when compared with fire needle combined with opioids (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 Network meta-analysis of the incidence of nausea and vomiting. (A) Network plot showing comparisons in the incidence of nausea and vomiting between each intervention. (B) Forest plot of the network meta-analysis comparing the incidence of nausea and vomiting in each treatment. (C) Schematic detailing the most secure treatments according to the surface under the cumulative ranking curve analysis (SUCRA). A, Body acupuncture combined with opioids; B, moxibustion combined with opioids; C, electroacupuncture combined with opioids; D, auricular acupuncture combined with opioids; E, point embedding combined with opioids; F, TEAS combined with opioids; G, wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids; H, fire needle combined with opioids; (I) opioids.

The ranking of nine interventions based on SUCRA values was as follows: fire needle combined with opioids (12.8%), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (26.6%), auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (34.2%), moxibustion combined with opioids (43.7%), wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids (47.7%), point embedding combined with opioids (56.4%), TEAS combined with opioids (64.1%), body acupuncture combined with opioids (69.4%), and opioids alone (95.0%) (Figure 4C).

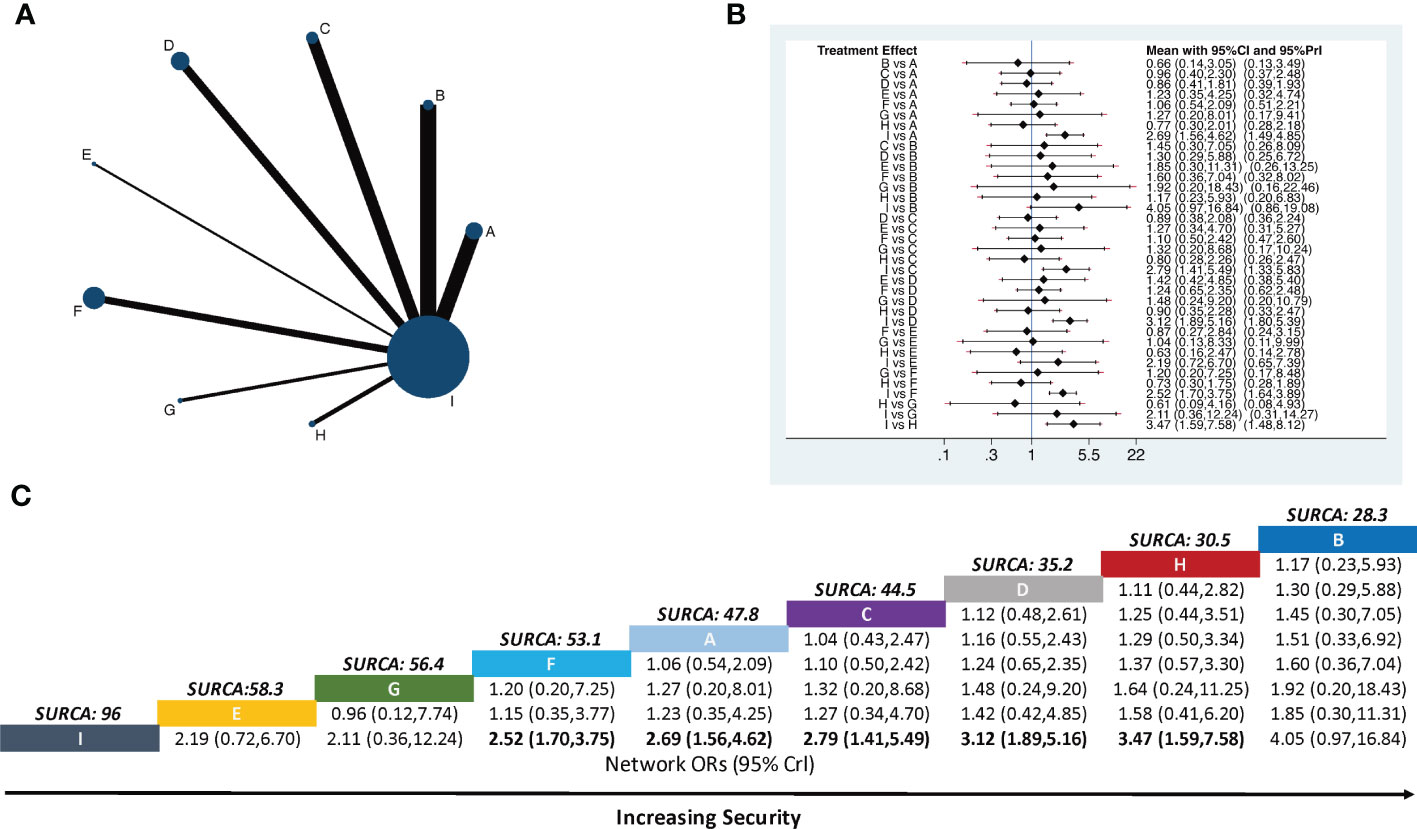

In total, 25 studies reported the incidence of constipation, which constituted eight pairs of direct comparisons (no closed loop). The above results are detailed in Figure 5A. There were 25 pair comparisons in the NMA in terms of the incidence of constipation, and five indicated statistically significant differences. Fire needle combined with opioids (RR = 3.47, 95% CI [1.59–7.58]), auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 3.12, 95% CI [1.89–5.16]), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 3.04, 95% CI [1.53–6.08]), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 2.79, 95% CI [1.41–5.49]), body acupuncture combined with opioids (RR = 2.69, 95% CI [1.56–4.62]), and TEAS combined with opioids (RR = 2.52, 95% CI [1.70–3.75]) were significantly superior to opioids alone (Figure 5B).

Figure 5 Network meta-analysis of the incidence of constipation. (A) Network plot showing comparisons in the incidence of constipation between each intervention. (B) Forest plot of the network meta-analysis comparing the incidence of constipation in each treatment. (C) Schematic detailing the most secure treatments according to the surface under the cumulative ranking curve analysis (SUCRA). A, Body acupuncture combined with opioids; B, moxibustion combined with opioids; C, electroacupuncture combined with opioids; D, auricular acupuncture combined with opioids; E, point embedding combined with opioids; F, TEAS combined with opioids; G, wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids; H, fire needle combined with opioids; I, opioids.

The ranking of nine interventions based on SUCRA values was as follows: moxibustion combined with opioids (28.3%), fire needle combined with opioids (30.5%), auricular acupuncture combined with opioids (35.2%), electroacupuncture combined with opioids (44.5%), body acupuncture combined with opioids (47.8%), TEAS combined with opioids (53.1%), wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids (56.4%), point embedding combined with opioids (58.3%), and opioids alone (96.00%) (Figure 5C).

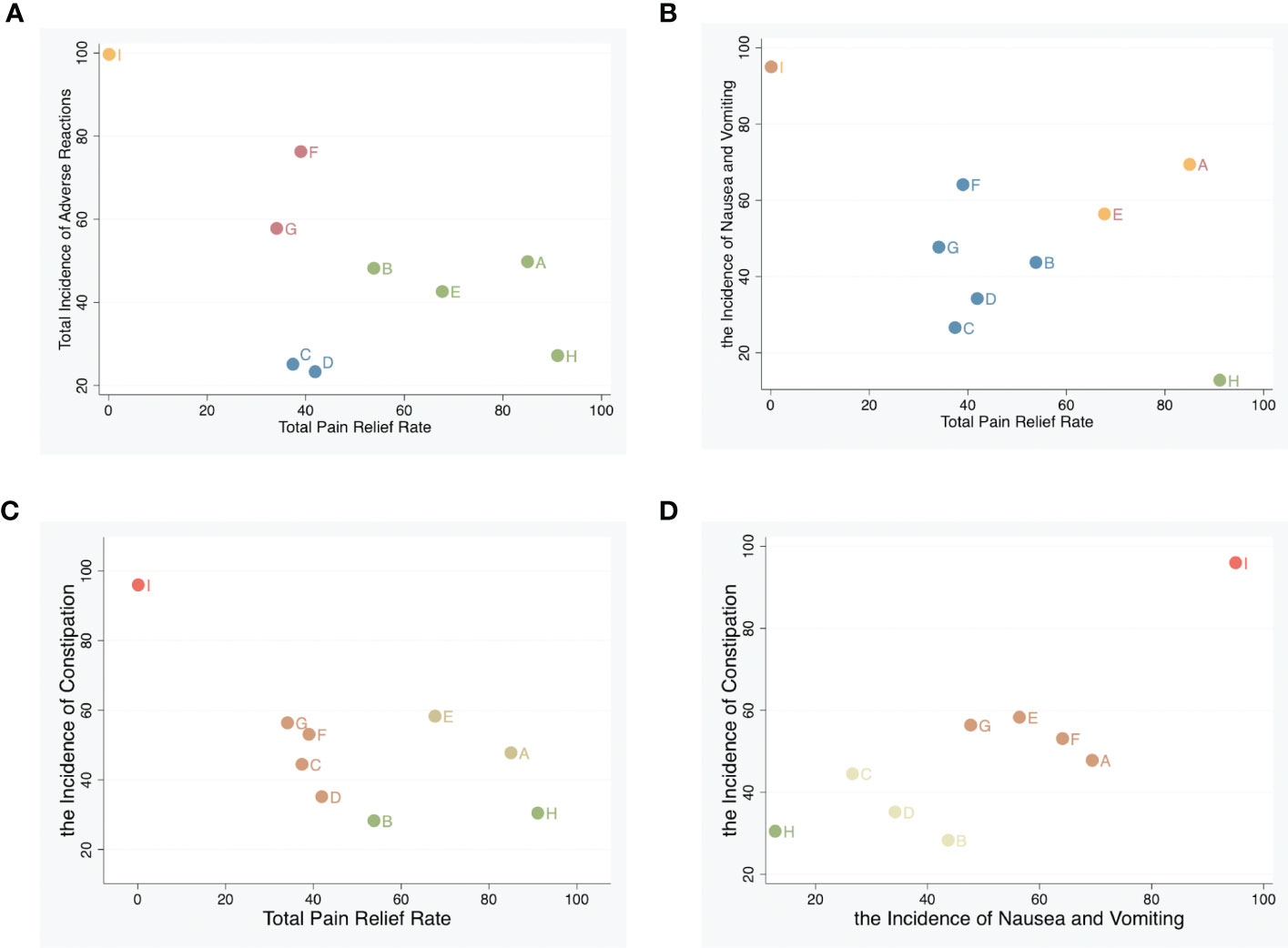

We used synthetic sorting bubble diagrams to comprehensively present the relatively better intervention for cancer pain in this NMA. Bubble plots indicated that, considering the total pain relief rate and incidence of adverse reactions, fire needle combined with opioids was the preferred treatment. It has the highest pain relief rate and the lowest incidence of adverse reactions, especially nausea and vomiting. The second is body acupuncture combined with opioids, which has a high pain relief rate and a low incidence of constipation, but a high incidence of nausea and vomiting. Opioids alone has the lowest pain relief rate and the highest incidence of adverse reactions (nausea, vomiting, or constipation) (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Synthetic sorting bubble diagram plot for outcomes. (A) Bubble diagram plot for the total pain relief rate and adverse reactions; (B) bubble diagram plot for total pain relief rate and nausea and vomiting. (C) Bubble diagram plot for total pain relief rate and constipation. (D) Bubble diagram plot for nausea and vomiting, and constipation. Note: Interventions with the same color belong to the same regimen, and interventions located in the lower left corner indicate optimal therapy for two different outcomes. A, Body acupuncture combined with opioids; B, moxibustion combined with opioids; C, electroacupuncture combined with opioids; D, auricular acupuncture combined with opioids; E, point embedding combined with opioids; F, TEAS combined with opioids; G, wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids; H, fire needle combined with opioids; I, opioids.

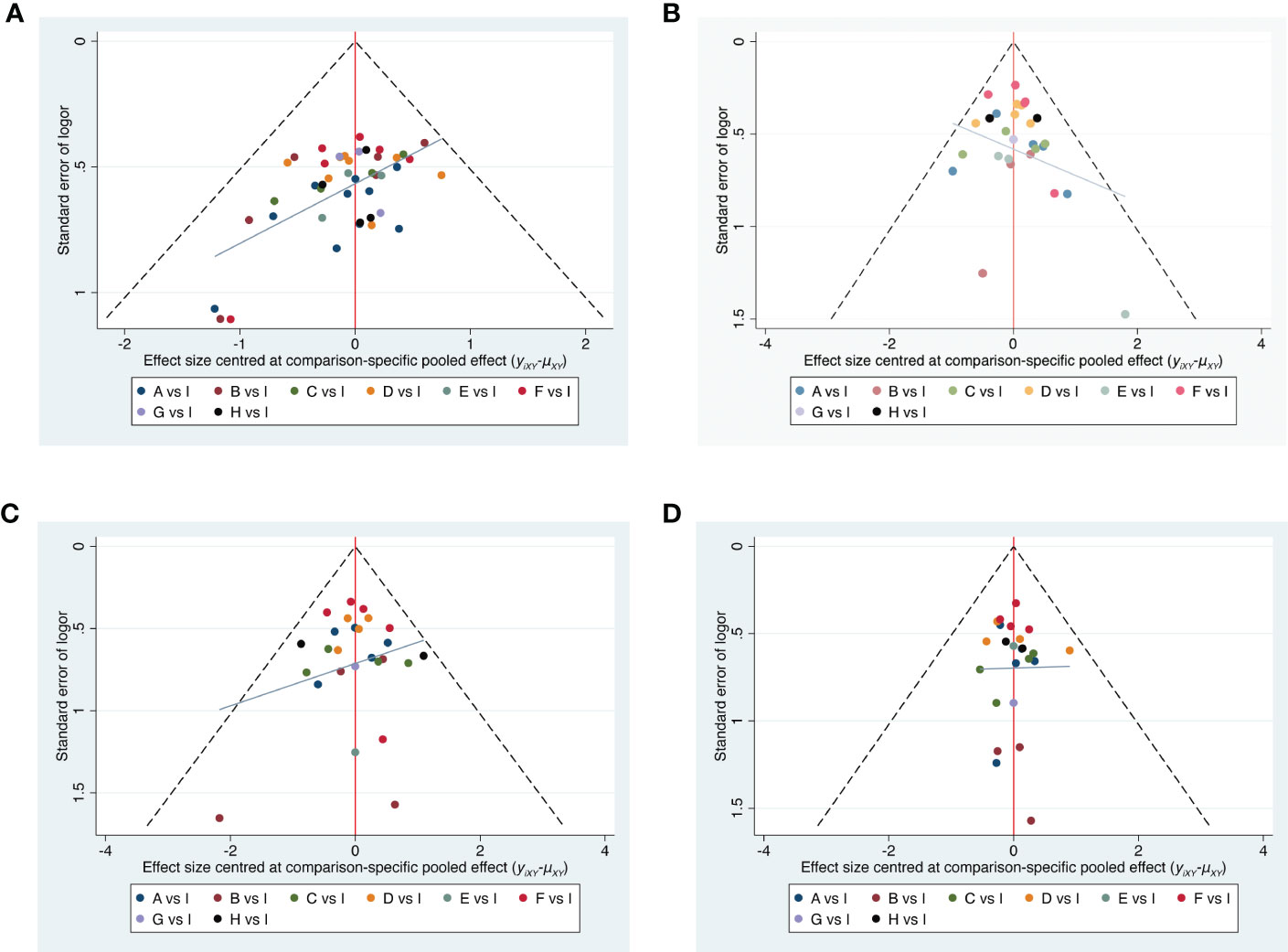

Publication bias was detected via comparison-adjusted funnel plots for four outcomes, respectively. All included randomized controlled trials had an overall bias with some concerns, suggesting that there may be some publication bias or a small sample effect in the inclusion study (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Funnel plots. (A) Total pain relief rate. (B) Total adverse reactions. (C) The incidence of Nausea and vomiting. (D) The incidence of constipation. A, Body acupuncture combined with opioids; B, moxibustion combined with opioids; C, electroacupuncture combined with opioids; D, auricular acupuncture combined with opioids; E, point embedding combined with opioids; F, TEAS combined with opioids; G, wrist–ankle acupuncture combined with opioids; H, fire needle combined with opioids; I, opioids.

Acupuncture points can be stimulated with different methods, including invasive and noninvasive stimulation. It is widely used in the treatment of various pain conditions. During the thousands of years practicing in China, a wide range of technical manipulations conducted by needle, magnetic bead, fire, electricity, and even the operator’s fingers were applied to muscle or soft tissue at specific body locations to remotely regulate body function (68). Studies have pointed out that acupuncture inhibits both the sensory and the affective components of inflammatory pain, acting through peripheral, spinal, and supraspinal mechanisms with the involvement of a battery of bioactive molecules (7, 69, 70). Of these, opioids play a central role in pain (7).

In this study, NMA was used to compare the effectiveness and safety of APS combined with opioids in treating moderate and severe cancer pain. A stratified analysis was conducted on opioid-related adverse reactions (including nausea and vomiting). Finally, the quantitative sequencing results of different outcome indicators were integrated to find the best intervention measures for the treatment of moderate and severe cancer pain. The results showed that compared with opioids alone, eight APS therapies (body acupuncture, moxibustion, electroacupuncture, auricular acupuncture, point embedding, TEAS, wrist–ankle acupuncture, and fire needle) could improve the rate of pain relief and reduce the incidence of opioid-related adverse reactions. These findings were consistent with findings in previous studies and reviews (5, 71). Fire needle combined with opioids was considered to be the most effective treatment for moderate to severe cancer pain. Fire needle is a traditional form of acupuncture that combines conventional acupuncture and cauterization with heated needle therapy. Previous studies have found that the fire needle is widely employed to relieve acute and chronic pain (72–74). Studies showed that the fire needle could regulate Wnt/ERK multi-signal pathways bidirectionally, which have been shown to be closely associated with neuropathic pain (73).

In terms of the incidence of adverse reactions, auricular acupuncture had the lowest incidence of total adverse reactions. It is a complementary alternative therapy based on the theory that dysfunction in the body’s organs causes changes in various areas outside the ears by stimulating these response points, which were connected to the “pathological” organs, to improve the function of the organ and thus relieve pain. At present, a number of studies have shown that auricular acupuncture has a positive effect on the treatment of various pains with a lower incidence of adverse reactions (75, 76). The analgesic effects of auricular acupuncture may be explained by the stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagal nerve (77). Opioids commonly cause gastrointestinal adverse reactions such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation, restricting their dosage for chronic pain control (78). In terms of the incidence of nausea and vomiting, APS combined with opioids was lower than opioids alone, and fire needle combined with opioids was the lowest. There was good clinical evidence showing that acupuncture had some effects in preventing or attenuating nausea and vomiting (79). Recent research also suggested that APS may be a kind of alternative therapy for the prevention and treatment of tumor nausea and vomiting (80).In terms of the incidence of constipation, moxibustion combined with opioids had the lowest incidence of constipation. A recent meta-analysis showed that combined therapy with both medicine and acupuncture has insightful potential for future clinical cancer patient management of constipation problems.

Considering the total pain relief rate and the incidence of adverse reactions, fire needle, body acupuncture, point embedding, and moxibustion were considered to be effective and safe methods in treating moderate to severe cancer pain. The combination of fire needle and opioids had the highest rate of total pain relief, and a lower incidence of adverse reactions, especially vomiting. This would be considered to be a priority option. The total pain relief rate of body acupuncture combined with opioids was second to fire needle but had a higher incidence of adverse reactions among the eight therapies, especially nausea and vomiting, which needed to be balanced. Point embedding also performed well in pain relief and the consideration of safety. Current studies on point embedding mainly focus on metabolic-related diseases (such as obesity, diabetes, etc.), and there were few studies on pain management. Only three studies were included in this study, and the evidence quality was relatively unsatisfactory; therefore, the conclusions should be treated with caution. In addition, the comprehensive effect of the fire needle and moxibustion was better. They both belong to traditional Chinese medicine’s warm and hot therapies that could dredge meridian to relieve pain. This might be why they were superior to other therapies.

We performed a comprehensive examination of the efficacy and safety of eight APS therapies in patients with moderate to severe cancer pain. The outcome measures were determined for the total pain relief rate and the incidence of adverse reactions. Given the large sample size and narrower confidence intervals applied in this network meta-analysis, we believed that the findings were reliable. This review has some limitations. Firstly, the heterogeneity of the baseline characteristics, such as male-to-female ratio, sample size, site, and duration were not analyzed. Second, the sample sizes were relatively small, which may reduce questions about the applicability and accuracy of the results. Thirdly, most studies were based on short follow-up periods, which limited long-term effects. Lastly, some outcomes, such as analgesic dose and quality of life, were not analyzed because of limited data.

Eight methods included in the present network analysis had different advantages in treating moderate to severe cancer pain. Based on the results of the network meta-analysis and probability ranking analysis, fire needle combined with opioids, filiform needle combined with opioids, moxibustion combined with opioids, and point embedding combined with opioids might be the four best ways to treat moderate to severe cancer pain. Of course, clinicians should thoroughly evaluate the degree of pain and the occurrence of adverse reactions and then make individualized treatment plans for patients to improve the analgesic effect. In addition, this network meta-analysis is vital for future research, highlighting the need for adequately designed RCTs and more head-to-head comparisons of the most commonly used dressings in this field. Currently, there is scant evidence, mainly indirect and mostly from small trials, with a risk of unclear bias.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

QZ: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing the original draft. LF: writing—review and editing and supervision. YW: conceptualization, validation, and data curation. YC: methodology and formal analysis. YY: writing review and editing and supervision. MZ: conceptualization, Project administration, and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the Project of the Central Public Scientific Research Institute of Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (No. 2019XK320072) and the Special Research Project of the Capital Health Development (No. 2020-2-4026).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2023.1166580/full#supplementary-material

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(3):209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2. Swarm RA, Paice JA, Anghelescu DL, Are M, Bruce JY, Buga S, et al. Adult cancer pain, version 3.2019, nccn clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw (2019) 17(8):977–1007. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0038

3. Kwon JH. Overcoming barriers in cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol (2014) 32(16):1727–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4827

4. Bennett M, Paice JA, Wallace M. Pain and opioids in cancer care: benefits, risks, and alternatives. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book (2017) 37:705–13. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_180469

5. He Y, Guo X, May BH, Zhang AL, Liu Y, Lu C, et al. Clinical evidence for association of acupuncture and acupressure with improved cancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol (2020) 6(2):271–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5233

7. Zhang R, Lao L, Ren K, Berman BM. Mechanisms of acupuncture-electroacupuncture on persistent pain. Anesthesiology (2014) 120(2):482–503. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000101

8. Vickers AJ, Linde K. Acupuncture for chronic pain. JAMA (2014) 311(9):955–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285478

9. Huang L, Zhao Y, Xiang M. Knowledge mapping of acupuncture for cancer pain: a scientometric analysis (2000-2019). J Pain Res (2021) 14:343–58. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S292657

10. Yang J, Wahner-Roedler DL, Zhou X, Johnson LA, Do A, Pachman DR, et al. Acupuncture for palliative cancer pain management: systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care (2021) 11(3):264–70. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002638

11. Wu X, Chung VCH, Hui EP, Ziea ETC, Ng BFL, Ho RST, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies for palliative care of cancer: overview of systematic reviews. Sci Rep (2015) 5:16776. doi: 10.1038/srep16776

12. Lu Y, Zhu H, Wang Q, Tian C, Lai H, Hou L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of multiple acupuncture therapies for primary insomnia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trial. Sleep Med (2022) 93:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2022.03.012

13. Wang L, Yin Z, Zhang Y, Sun M, Yu Y, Lin Y, et al. Optimal acupuncture methods for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Pain Res (2021) 14:1097–112. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S310385

14. Su P, Leng Y, Liu J, Yu Y, Wang Z, Dang H. Comparative analysis of the efficacy and safety of different traditional Chinese medicine injections in the treatment of cancer-related pain: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol (2021) 12:803676. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.803676

15. Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2019) 10:ED000142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142

16. Shih C-Y, Gordon CJ, Chen T-J, Phuc NT, Tu M-C, Tsai P-S, et al. Comparative efficacy of nonpharmacological interventions on sleep quality in people who are critically ill: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud (2022) 130:104220. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104220

17. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, et al. The prisma extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med (2015) 162(11):777–84. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385

18. Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. Prisma 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (2021) 372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160

19. Chao Z, Xiufang W, Yinyin H, Yulong C, Liang Z, Deng L. Effect of acupuncture and moxibustion on bone metastasis cancer pain in community health service. Women’s Health Res (2019) 2019(20):119–20.

20. Dan L, Rui-Rui S, Qing-Ling L, Qiang M, Yong-Lei Z, Xue-Zhao J, et al. Acupuncture combined with opioid drugs on moderate and severe cancer pain: a randomized controlled trial. Zhongguo Zhen jiu Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion (2020) 40(3):257–61. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20190311-k0001

21. Dehui L, Chunxia S, Huanfang F, Xiao W, Liying W. Clinical study on acupuncture at zusanli, taichong and hegu points combined with three-step analgesic ladder for treatment of gastric cancer pain. J Guangzhou Univ Traditional Chin Med (2017), 344–7. doi: 10.13359/j.cnki.gzxbtcm.2017.03.011

22. Dian-rong L, Sheng-qi H, Li F, Dian-xiang L, Xiao-fen Y, Fang W, et al. Clinical research in the treatment of moderate and severe bone metastasis pain with acupuncture for tonifying kidney and eliminating stasis. World J Integrated Traditional Western Med (2018) 13(01):116–20. doi: 10.13935/j.cnki.sjzx.180132

23. Fan L, Gao S, Wang Y, Qi Z. Clinical observation of acupuncture combined with Western medicine in treatment of advanced lung cancer pain. Med J Chin People’s Health (2017) 29(11):36–8.

24. Na X, Fangfang M, Peiyu C, Qi F, Yongme X, Guowang Y. Clinical observation acupuncture for regulating the mind and relieving pain in the treatment of moderate and severe cancer pain. Modern J Integrated Traditional Chin and Western Med (2022) 03(31):334–7+424. doi: 10.3969//j.issn.1008-8849.2022.03.008

25. Qinggang D. Clinical study of acupuncture at mingmen and guanyuan acupionts combined with analgesic on the treatment of lumbar spinal metastatic carcinoma pains. Chin Med Modern Distance Educ China (2015) 13(07):65–6.

26. Weiji L, Jinyuan Y. Therapeutic effect of acupuncture and morphine in the treatment of advanced lung cancer pain. China Health Care Nutr (2012) 2012(09):78.

27. Yi D. Effect of morphine sulfate controlled-release tablets combined with acupuncture on improving quality of life in elderly patients with cancer pain. Modern J Integrated Traditional Chin Western Med (2015) 24(06):606–8.

28. Ying H. Effect of acupuncture and moxibustion combined with three steps drugs on moderate and severe cancer pain. Inner Mongolia J Traditional Chin Med (2018) 37(05):58–9. doi: 10.16040/j.cnki.cn15-1101.2018.05.041

29. Zhiwei Q. Clinical study of acupuncture combined with opioids in the treatment of cancer pain. Modern Digestion Intervention (2019) 24(A01):0310–1.

30. Zhuo C, Hong-yu X, Qi C. Clinical observation on acupuncture plus oxycodone hydrochloride sustained release tablets for severe cancer pain caused by vertebral metastasis. Shanghai J Acupuncture Moxibustion (2021) 40(4):411–5. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2021.04.0411

31. Bing L, Lin L, Li T, Cuiqing D, Jinfang J. Curative effect and mechanism of heat-sensitive moxibustion combined with Western medicine in treating severe colon cancer pain of deficient healthy qi and blood stasis type. J Shandong Univ Traditional Chin Med (2020) 44(05):539–43+49. doi: 10.16294/j.cnki.1007-659x.2020.05.017

32. Hongyan X. Effect of thunder fire moxibustion on moderate to severe cancer pain. Cardiovasc Dis Electronic J Integrated Traditional Chin Western Med (2018) 6(09):147+50. doi: 10.16282/j.cnki.cn11-9336/r.2018.09.103

33. Jun C, Haifa Q, Jing L. The clinic research of Back shu point moxibustion plus oral oxycodone in cancer pain. Shaanxi J Traditional Chin Med (2020) 41(01):105–107.

34. Li-xia L. Therapeutic efficacy of heat-sensitive moxibustion in adjuvant treatment of moderate liver cancer pain and its effects on tnf-A and il-2. Shanghai J Acupuncture Moxibustion (2020) 39(06):692–6. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2020.06.0692

35. Liqiong L, Xiaoxiao Z, Xiang T. Effect of thunder fire moxibustion on moderate and severe cancer pain. Res Integrated Traditional Chin Western Med (2021) 13(04):284–5+8.

36. Ping X, wen X, Youhui Y, Lu Z, Yarong T. Effect of thunder fire moxibustion combined with opioid drugs on cancer pain. Lab Med Clinic (2021) 18(19):2875–7.

37. Qiaotong H, Lian C, Yunfeng J. Effect of thunder fire moxibustion on moderate to severe cancer pain. Guangxi J Traditional Chin Med (2014) 37(06):37–8.

38. Jun C, Haifa Q, Jing L. The clinic research of back shu point moxibustion plus oral oxycodone in cancer pain. Shaanxi J Traditional Chin Med (2020) 41(01):105–7.

39. Can W. Clinical study on electroacupuncture combined with hydromorphone for moderate and severe cancer pain of stagnation of static blood type. New Chin Med (2019) 51(10):242–4. doi: 10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2019.10.069

40. Chu-ting X, Xin-wei L, Yi-nuo T. Clinical observation of 35 cases of lung cancer patients with pain treated by dense wave electroacupuncture combined with Western medicine. Zhejiang J Traditional Chin Med (2020) 55(04):295–6. doi: 10.13633/j.cnki.zjtcm.2020.04.035

41. Hui W, Ying W, Hong-ming F. Thirty cases of patients with lung cancer pain treated with electro-acupuncture based on syndrome differentiation. Henan Traditional Chin Med (2018) 38(03):454–7. doi: 10.16367/j.issn.1003-5028.2018.03.0120

42. Lu D-R, Xia Y-Q, Chen F, Wang N-J, He S-Q, Wang F, et al. Effect of electrothermal acupuncture on moderate to severe cancer pain with yin-cold stagnation: a randomized controlled trial. Zhongguo Zhen jiu Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion (2021) 41(2):121–4.

43. Zhi-ling Y, Ya-bin G. Clinical observation of electroacupuncture combined with opioids in the treatment of cancerous pain. J Oncol Chin Med (2021) 3(03):30–5. doi: 10.19811/j.cnki.ISSN2096-6628.2021.03.000

44. Chen L-x, Yan F. Clinical study on auricular point sticking plus Western medicine for moderate gastric cancer pain. J Acupuncture Tuina Sci (2020) 18(4):276–80. doi: 10.1007/s11726-020-1188-6

45. Fengying Y, Ailing P. Clinical observation of auricular acupuncture combined with morphine sustained-release tablets in the treatment of cancer pain. Chin Pract J Rural Doctor (2011) 18(2):56–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7185.2011.02.036

46. ZW HL HU. Clinical observation on auricular acupressure therapy combined with strong opioids for moderate to severe cancer pain. J Traditional Chin Med (2012) 53(13):1123–5.

47. Jing X, Zunhua S. The evaluation on the curative effect of auricular needle in treating hepatocellular pain for 40 cases. Chin Med Modern Distance Educ China (2017) 15(18):112–3.

48. Qing-quan W, Yu C, Lei Z, Ming L. Treatment of 60 cases of cancer pain with auricular acupoint pressing bean combined with morphine sulfate sustained-release tablets. J External Ther Traditional Chin Med (2016) 25(04):18–9.

49. Run C, Ruifang Z, Ping F, Weixia H. The effect of auricular plaster therapy combined with oxycodone hydrochloride sustained release tablets on the number of pain outbreak, ppi score and kps score in cancer pain patients. Med J West China (2021) 33(11):1683–6.

50. Wei S, Zi-li Z. Clinical observation of auricular press-needle combined with Western medicine treating cancer pain. Chin Manipulation Rehabil Med (2016) 7(09):24–5.

51. Xiaodan H, Shi C. Effect of auricular point pressing pill combined with morphine on patients with moderate and severe cancer pain in hospice care. Chin Community Doctors (2019) 35(24):90. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-614x.2019.24.064

52. Guo-dong Z, Zhi-hui Z, Hong-fang S. Clinical study of acupoint catgut embedding therapy on colorectal cancer pain. World Latest Med Inf (2021) 21(20):9–10. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-3141.2021.20.005

53. Jiao G, Jie C, Yan-hua X, Chao K, Mei-mei H, Chen-guang Y. Clinical effect of acupoint catgut-embedding combined with painkillers on bone metastatic cancer pain. Clin Res Pract (2020) 5(07):115–7. doi: 10.19347/j.cnki.2096-1413.202007049

54. Yougang W, Changping Z. Therapeutic effect of acupoint catgut embedding on cancer pain of lung cancer. J Prev Med Chin People’s Liberation Army (2016) 34(S1):297–8. doi: 10.13704/j.cnki.jyyx.2016.s1.264

55. Ding J, Huang J. Curative effects and costs of oxycontin combined with bio-electric stimulation therapy in treatment of moderate or severe cancer pain. Chin Gen Pract (2014) 17(3):325–7.

56. Hui Z, Wei-fang H, Li-li H, Li-hua H. The influence of traditional Chinese medical nursing intervention combined with transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation in the treatment of bone metastasis pain of advanced lung cancer. J Guizhou Univ Traditional Chin Med (2016) 38(04):85–9. doi: 10.16588/j.cnki.issn1002-1108.2016.04.023

57. Jian-chun P, Hui-ying H, Sheng-ling Z. Nursing with traditional Chinese medicine combined with percutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation for advanced lung cancer complicated with bone metastasis related pain. Chin J Clin Oncol Rehabil (2021) 28(10):1243–6. doi: 10.13455/j.cnki.cjcor.2021.10.24

58. Ming-hua W, You-jie Y. Efficacy of oxycodone hydrochloride sustained release tablets combined with bioelectrical stimulation in the treatment of moderate to severe cancer pain. Health Res (2015) 35(05):562–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-6449.2015.05.032

59. Qiuhong L, Wei Z, Zhiqun L. Curative effect and costs of oxycontin combined with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulationn treatment of moderate or severe cancer pain. Pract J Cancer (2015) 30(06):922–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5930.2015.06.042

60. Yun D, Xing-feng Z, Juan-juan P, Yu-lin Y. The therapeutic efficacy of oxycodone hydrochloride prolonged release tablets combined with bioelectric stimulation in treatment of neuropatho-logical cancer pain. J North Sichuan Med Coll (2017) 32(1):30–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-3697.2017.01.009

61. Ling-ling W, Xue-dong L, Bi-quan Q, Ye-jing L, Dan-qian W. Efficacy observation of wrist-ankle acupuncture combined with opioids for primary liver cancer-related pain. Shanghai J Acupuncture Moxibustion (2021) 40(11):1336–40. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2021.11.1336

62. Su-e S. Clinical observation on analgesic effect of wrist and ankle needle combined with drugs in cancer patients. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion (2000) 2000(03):15–6. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.2000.03.008

63. Xiang-hong W, Fei-hong L. Study on clinical effect of wrist ankle acupuncture combined with oxycodone hydrochloride sustained-release tablets in the treatment of refractory cancer pain. Chin Evidence-Based Nurs (2021) 7(18):2497–500. doi: 10.12102/j.issn.2095-8668.2021.18.015

64. Guo-dong Z, Zhi-hui Z. Clinical study on the treatment of cancer pain with fire needle. China Health Care Nutr (2018) 28(27):36–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-7484.2018.27.021

65. Weijie B, Enming L, Cantu F, Zekun L, Zhiqiang Z, Meizhen X, et al. Clinical study on the treatment of cancer pain based on the theory “Fire to smooth, generally no pain”. Chin Manipulation Rehabil Med (2019) 10(15):14–7.

66. Xin G, Shi-Nian Z. Clinical observation of filiform fire needling on moderate and severe pain in advanced cancer. Zhongguo Zhen jiu= Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion (2020) 40(6):601–4.

67. Zhi-peng Z, Yu-chun N. Effect of oxycontin combined with fire needling in treating cancer pain. World J Integrated Traditional Western Med (2020) 15(04):753–6. doi: 10.13935/j.cnki.sjzx.200442

68. Eshkevari L. Acupuncture and chronic pain management. Annu Rev Nurs Res (2017) 35(1):117–34. doi: 10.1891/0739-6686.35.117

69. Jang J-H, Song E-M, Do Y-H, Ahn S, Oh J-Y, Hwang T-Y, et al. Acupuncture alleviates chronic pain and comorbid conditions in a mouse model of neuropathic pain: the involvement of DNA methylation in the prefrontal cortex. Pain (2021) 162(2):514–30. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002031

70. Abali AE, Cabioglu T, Bayraktar N, Ozdemir BH, Moray G, Haberal M. Efficacy of acupuncture on pain mechanisms, inflammatory responses, and wound healing in the acute phase of major burns: an experimental study on rats. J Burn Care Res (2022) 43(2):389–98. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irab142

71. MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, Fitter M. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ (2001) 323(7311):486–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.486

72. Fu Y-B, Chen J-W, Li B, Yuan F, Sun J-Q. Effect of fire needling on mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis and related serum inflammatory cytokines. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu (2021) 41(5):493–7. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.20200708-k0003

73. Xu J, Cheng S, Jiao Z, Zhao Z, Cai Z, Su N, et al. Fire needle acupuncture regulates Wnt/Erk multiple pathways to promote neural stem cells to differentiate into neurons in rats with spinal cord injury. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets (2019) 18(3):245–55. doi: 10.2174/1871527318666190204111701

74. Wang Y, Fu Y, Zhang L, Fu J, Li B, Zhao L, et al. Acupuncture needling, electroacupuncture, and fire needling improve imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin lesions through reducing local inflammatory responses. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med (2019) 2019:4706865. doi: 10.1155/2019/4706865

75. Murakami M, Fox L, Dijkers MP. Ear acupuncture for immediate pain relief-a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Med (2017) 18(3):551–64. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw215

76. Asher GN, Jonas DE, Coeytaux RR, Reilly AC, Loh YL, Motsinger-Reif AA, et al. Auriculotherapy for pain management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Altern Complement Med (2010) 16(10):1097–108. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0451

77. Usichenko T, Hacker H, Lotze M. Transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation (Tavns) might be a mechanism behind the analgesic effects of auricular acupuncture. Brain Stimul (2017) 10(6):1042–4. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2017.07.013

78. Bell TJ, Panchal SJ, Miaskowski C, Bolge SC, Milanova T, Williamson R. The prevalence, severity, and impact of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results of a us and European patient survey (Probe 1). Pain Med (2009) 10(1):35–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00495.x

79. Streitberger K, Ezzo J, Schneider A. Acupuncture for nausea and vomiting: an update of clinical and experimental studies. Auton Neurosci (2006) 129(1-2):107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.015

Keywords: cancer pain, acupuncture-point stimulation, opioid, supplementary alternative therapy, network meta-analysis

Citation: Zhang Q, Yuan Y, Zhang M, Qiao B, Cui Y, Wang Y and Feng L (2023) Efficacy and safety of acupuncture-point stimulation combined with opioids for the treatment of moderate to severe cancer pain: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Oncol. 13:1166580. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1166580

Received: 20 February 2023; Accepted: 15 May 2023;

Published: 02 June 2023.

Edited by:

Linqing Miao, Beijing Institute of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Ran Ding, Nantong First People’s Hospital, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Zhang, Yuan, Zhang, Qiao, Cui, Wang and Feng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Li Feng, ZmVuZ2xpNjYzQDEyNi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.