94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 01 March 2023

Sec. Surgical Oncology

Volume 13 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1083618

This article is part of the Research Topic Surgical Oncology in the Elderly: The State of the Art and Future Challenges View all 11 articles

Background: Surgery is the sole curative therapy for gallbladder cancer (GBC) patients. Confronting an aging society, the demand to treat elderly patients with GBC is increasing. But there are few reports on survival benefit in elderly GBC patients treated with surgery. Therefore, we designed this population-based study to assess the survival benefit of surgery in GBC patients aged 70 years or older.

Methods: GBC patients aged 70 years or older were identified in the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results cancer (SEER) database from 2010 to 2017. A 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was conducted to balance the baseline data of patients. Overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) of patients were evaluated by Kaplan-Meier analysis and compared with log-rank test. Independent risk factors associated with OS and CSS were determined by univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses and subgroup analysis were performed.

Results: A total of 2055 GBC patients aged 70 years or older were included in our study, with 1734 patients underwent surgery. Before PSM, the age, AJCC stage, TNM stage, and chemotherapy were significantly different between the surgery and no-surgery group (all P<0.05). Patients with surgery had significantly longer OS and CSS than those without surgery (P<0.0001). After 1:1 PSM, the differences in clinicopathological characteristics were reduced (all P>0.05). Kaplan-Meier analysis also showed patients received surgery had significantly better OS and CSS (P<0.0001). Subgroup analysis further indicated that almost all subgroups received surgery had OS and CSS advantage, especially patients aged 70-84 years old. Finally, univariate and multivariate COX regression analyses showed that age, AJCC stage and T stage were independent prognostic factors for OS and CSS in patients undergoing surgery.

Conclusion: Our study found that surgery significantly improved OS and CSS in GBC patients aged 70-84 years, but more prospective studies are needed to prove our findings.

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is a rare tumor ranking sixth among most common gastrointestinal cancer, and the most prevalent cancer of biliary tract (1, 2). The estimated number of new GBC cases was 115,949, representing 0.6% of all cancer cases in 2020 (3). It is well known that gallbladder adenocarcinoma (GBAC) is the most common pathological type of gallbladder cancer. The elderly patients account for the vast majority of patients with gallbladder cancer, previous study showed that the median age of GBC patients was 71 years (4). The prognosis of patients with gallbladder cancer deteriorates with age, the increasing incidence and mortality rates were primarily observed in men≥60 years and in women≥70 years of age (5). Surgery is the first line of treatment for gallbladder cancer patients (6). Currently, there have not been standard treatment guidelines for GBC in the elderly patients. Treatment in these patients remains a complicated issue because of the limited evidence, pre-existing disease, and adverse drug reactions, which lead to either undertreatment or overtreatment. Study demonstrated that complication rates, length of hospital stay, and intensive care unit admissions increased with patient age (7). The benefit of surgery for the old population has been discussed, but the results were contradictory (8–10). Several studies have also shown that age is a risk factor for prognosis in patients undergoing surgery for gallbladder cancer (11, 12). Thus, whether elderly patients with gallbladder cancer can benefit from surgical treatment or not is a topic worth exploring.

Therefore, in the current study, we extracted data of elderly patients with gallbladder cancer from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, in order to clarify the impact of surgery on elderly GBC patients (≥70 years old).

The patient data were obtained from the SEER database, which is openly accessible and freely available for researchers. We used the SEER*Stat software with a data user agreement, the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition (ICD-O-3) Code C23.9 was used as a reference for selection. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Patients diagnosed with GBC between 2010-2017. The diagnosis was confirmed by positive histology, and the type of reporting source was not autopsy or death certificate. Patients diagnosed as non-adenocarcinoma, younger than 70 years old, survival time less than 1 month, lacking data about pathological diagnosis, TNM stage and survival were excluded. The data for patients’ sex, age, marital status, race, AJCC stage, TNM stage, surgery status, radiation status and chemotherapy status were identified. Our detailed workflow was shown in Figure 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics were compared between surgery and no-surgery group by Chi-square and Fisher’s exact probability tests. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to the date of death due to any cause or the last follow-up. Cancer cause-specific survival (CSS) was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from cancer. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional risk regression analyses were applied to identifying independent risk factors on survival of GBC patients. Survival analysis was accomplished by the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. Propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted to calibrate the effects of the baseline data differences. All the statistical analyses and graphics were performed with the R statistical software.

Among 8583 GBC patients originally identified from SEER database, cases of 1734 patients treated with surgery and 321 without surgery from 2010 to 2017 were included in our study. The clinicopathological characteristics between two groups before PSM were summarized in Table 1. A majority were female in both surgery and no-surgery group (67.99% vs 69.78%, P=0.571), and most of them were White (80.22% vs 76.95%, P=0.237). The proportion of patients aged 75-85 years was higher in surgery group compared with no-surgery group (72.43% vs 63.24%, P=0.005). In total, 18.4% of the patients with surgery versus 72.59% of those without surgery were AJCCIV(P<0.001). Compared with patients underwent surgery, significantly more patients in no-surgery group had TNM clinical stage of T4 (12.46% vs 1.85%, P < 0.001), N2 (9.97% vs 2.77%, P < 0.001), and M1 (64.80% vs 15.80%, P < 0.001). The PSM method was used to balance all characteristics, including sex, age, marital status, race, AJCC, TNM stage, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy between surgery and no-surgery groups. And a total of 248 surgery patients were matched with 248 no-surgery patients (1:1). The clinicopathological characteristics were shown in Table 2. Most of the patients were female in both surgery and no-surgery group (68.15% vs 70.97%, P= 0.558). Approximately 62% patients were aged 70-79 years in both two groups (P=0.146). AJCCIVtumors (65.73% vs 64.52%, P = 0.565) as well as TNM clinical stage of T4 (7.66% vs 6.45%, P < 0.726), N2 (9.27% vs 8.06%, P < 0.213), and M1 (56.45% vs 57.26%, P=0.928) were balanced in two groups. Other characteristics, including marital status, race, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy status also showed no significantly difference between the two groups (all P>0.05).

We explored the potential independent prognosis factor for GBC patients through univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis. Multivariate analysis showed that age≥85 years old (HR=1.661, 95%CI: 1.216-2.268, P=0.001), M1 (HR=1.774, 95%CI: 1.455-2.163, P<0.001) were significantly associated with poor OS. Surgery (HR=0.633, 95%CI: 0.527-0.761, P<0.001) and chemotherapy (HR=0.568, 95%CI: 0.466-0.694, P<0.001) were significantly associated with better OS (Table 3). The same results were also observed on the analysis of CSS. Age≥85 years old (HR=1.507, 95%CI: 1.076-2.111), M1 (HR=1.862, 95%CI: 1.504-2.306, P<0.001) were significantly associated with poor CSS. Surgery (HR=0.607, 95%CI: 0.498-0.739, P<0.001) and chemotherapy (HR=0.599, 95%CI: 0.484-0.741, P<0.001) were significantly associated with better CSS (Table 4).

Before PSM, patients in surgery group had significantly longer OS and CSS compared with patients in no-surgery group (median OS: 17 months vs 4 months, P < 0.001; median CSS: 26 months vs 5 months, P < 0.001, Figure 2). After adjusting for variables (sex, age, marital status, AJCC, TNM stage, radiotherapy and chemotherapy), surgery group still performed better OS and CSS (median OS: 8 months vs 4 months, P < 0.0001; median CSS: 9 months vs 5 months, P < 0.001, Figure 3).

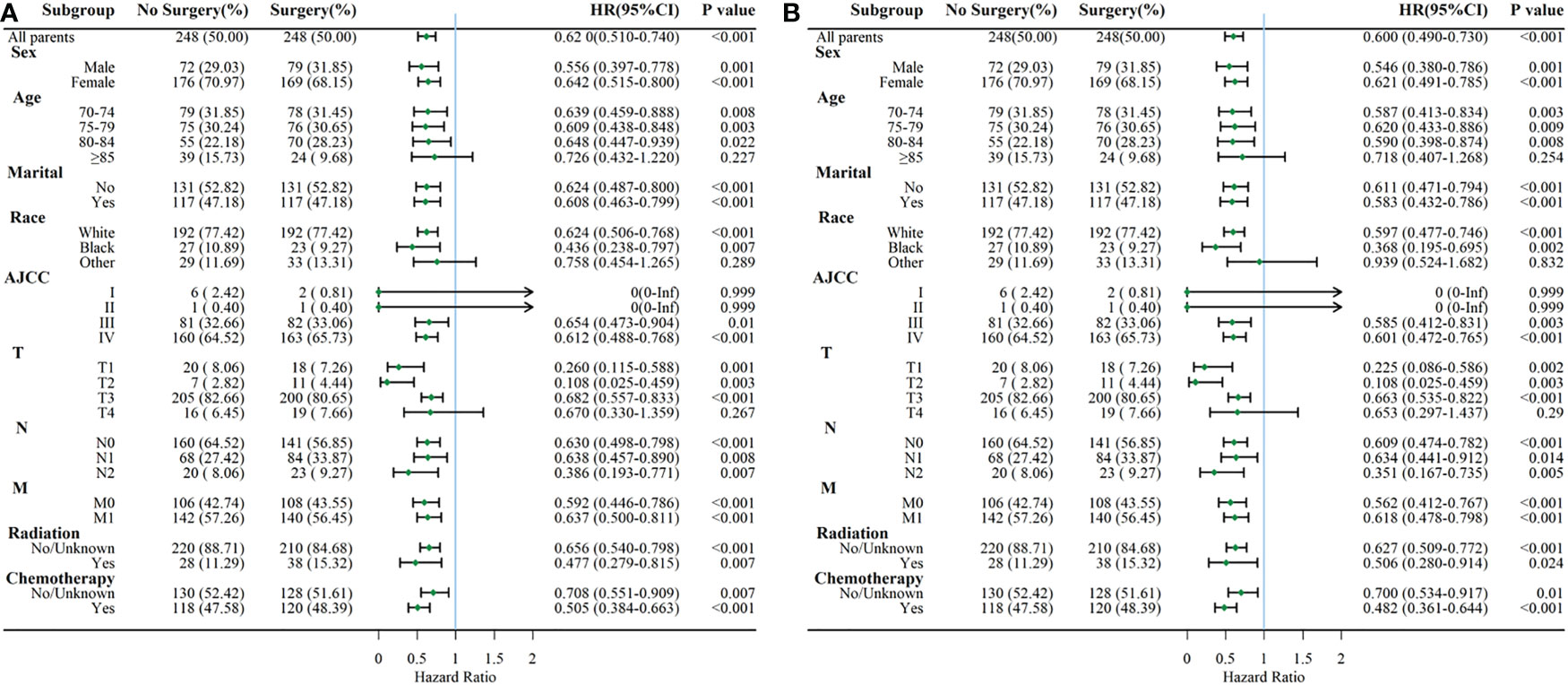

Considering the reduction of selection bias, patients were stratified into subgroups according to the different clinical characteristics, and subgroup analysis were performed (Figure 4). The results showed that surgery was a protective prognostic factor for OS in almost all subgroups, including patients aged 70-84 years old. AJCCIandIIsubgroups presented insignificant differences in OS between surgery and no-surgery patients because of a small number of available cases. The CSS subgroup analysis showed that surgical treatment was a protective factor for DSS survival in the same subgroups as OS.

Figure 4 Subgroup analysis comparing OS (A) and CSS (B) between surgery and no-surgery order GBC patients.

To further investigate the prognostic factors affecting elderly patients who underwent surgery, we performed univariate and multivariate cox regression analyses. The results showed that age, AJCC stage and T stage were independent risk factors for OS (Table 5) and CSS (Table 6). In addition, marriage was also an independent risk factor for OS but not for CSS.

Surgery remains a fundamental part of GBC management and is the only potentially curative modality (13). Although many studies have reported some prognostic factors for GBC patients, including age, TNM stage, tumor size, adjuvant therapy, and pathological grade (11, 14–17), there were little data on the survival benefit of surgery in elderly patients with GBC. This special population was rarely included in randomized controlled trials that exploring the effect of surgery. Only a few observational studies have investigated this problem, but the applicability of the results was limited by the small sample sizes (18–20). Hence, we conducted this population-based study to explore the survival benefit of surgery in GBC patients aged 70 years or older.

The clinicopathological features and survival outcomes of GBC patients in surgery and no-surgery group were compared in this study. We found that patients with better AJCC and TNM stage were more likely to receive surgery (P<0.001). The AJCC and TNM stage are essential factors for judging the degree of tumor progression, choosing treatment decisions, and determining prognosis (21). GBC patients in advanced stages experienced the lowest rates of survival. Previous research demonstrated that patients with distant metastasis had higher mortality risk (HR= 2.392, 95% CI=2.027-2.823, P<.001) (14). Similarly, the present study showed that patients presented with M1 stage experienced higher mortality risk (for OS, M1 vs M0: HR=1.774; for CSS, M1 vs M0: HR=1.862, P<0.001). Subgroup analysis according to AJCC demonstrated that surgery could improve OS and CSS in elderly patients with AJCC III and IV. However, surgery did not affect OS and CSS in AJCC I andIIpatients. This might because of the relative small size of GBC patients with AJCC I andIIincluded in our study. Subgroup analysis also indicated that GBC patients aged 70 years or older with T1-3, any N and M stage could get OS and CSS benefits from surgery. Thus, the AJCC and TNM stage are helpful in selecting patients suitable for surgery and evaluating the prognosis for GBC patients. In addition, our study found that age, AJCC stage, and T stage were prognostic predictors for elderly patients with gallbladder cancer who underwent surgery, which is consistent with previous studies (16, 17, 22). This suggests that a detailed assessment of these factors is an important part of the comprehensive evaluation before receiving surgical treatment. Notably, our study also found that marriage was an independent predictor of OS in patients undergoing surgery and it was not statistically significant for CSS. Patients who are fighting cancer may benefit from the good experience and emotional support that come from marriage. These non-disease-induced interferences were corrected for in the CSS analysis.

In our study, we demonstrated that the cumulative mortality of GBC patients in surgery group was lower than that of no-surgery group, as well as after PSM. Multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that surgery was a positive predictive factor of OS and CSS in GBC patients (for OS, HR=0.633, 95% CI=0.527-0.761, P<0.001; for CSS, HR=0.607, 95% CI=0.498-0.739, P<0.001). Subgroup analysis according to age was made in our study. Surgery significantly improved OS and CSS in patients aged 70-84 years old (P<0.05), but did not enhance survival in patients aged 85 or older (P>0.05). We assumed that increased age may account for more post-surgery complications, and the usual poorer nutritional status could decrease their resistance to complications. Considering their short remaining survival time, there will be few benefits to perform surgery in GBC patients aged ≥85 years, both patients and physicians had better not take the surgical risks. At the same time, if surgery must be performed inevitably, risk management is essential. Li P et al. showed that patients who underwent gallbladder adenocarcinoma resection older than 65 years may have a relatively poor OS (17). Xu X et al. demonstrated that GBC patients older than 70 years after surgery were also inversely correlated with survival (11). Our study provides further evidence that elderly patients aged 70-84 years with GBC can still benefit significantly from surgical treatment after a reasonable comprehensive evaluation. To our best knowledge, the present study was the first population-based study that systematically clarify the effect of surgery on patients over 70 years of age.

Our research has some strengths. First, our research was based on the SEER database, which collected clinical data from 28% of the US population. This means that our result is supported by a large amount of data. Second, compared with previous studies, our research targeted patients with GBC older than 70 years old. The present study also has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study based on the SEER database, so selective bias was inevitable. Although we adjusted for confounding bias based on Cox regression, PSM, and subgroup analysis, these methods still failed to correct for potential unknown bias. Second, the SEER database lacks many data on factors such as basic diseases, preoperative physical status, and complications that may have a significant impact on the choice of treatment methods and prognosis of patients. More high-quality prospective studies are needed in the future to validate our conclusions.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that surgery was an independent prognostic factor of OS and CSS for elderly GBC patients (≥70 years old). For patients of 70-84 years old, surgery was associated with improved OS and CSS. Future studies of prospective, randomized and multicenter trials are needed to validate our finding.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The data of this study is obtained from the SEER database. The patients’ data is public and anonymous, so this study does not require ethical approval and informed consent.

XX and QD designed the study. XX collected and analyzed the data. XX drafted the initial manuscript. QD and JW reviewed and edited the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Miranda-Filho A, Pineros M, Ferreccio C, Adsay V, Soerjomataram I, Bray F, et al. Gallbladder and extrahepatic bile duct cancers in the americas: Incidence and mortality patterns and trends. Int J Cancer (2020) 147(4):978–89. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32863

2. Halaseh SA, Halaseh S, Shakman R. A review of the etiology and epidemiology of gallbladder cancer: What you need to know. Cureus (2022) 14(8):e28260. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28260

3. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(3):209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

4. Coburn NG, Cleary SP, Tan JC, Law CH. Surgery for gallbladder cancer: A population-based analysis. J Am Coll Surg (2008) 207(3):371–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.02.031

5. Zhang M, Wu C, Zuo B, Gong W, Zhang Y, Yang Y, et al. Trends of gallbladder cancer incidence, mortality, and diagnostic approach in urban shanghai between 1973 and 2009. Tumori (2020) 106(5):392–9. doi: 10.1177/0300891619890232

6. Kondo S, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Miyakawa S, Tsukada K, Nagino M, et al. Guidelines for the management of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas: Surgical treatment. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg (2008) 15(1):41–54. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1279-5

7. Al-Refaie WB, Parsons HM, Habermann EB, Kwaan M, Spencer MP, Henderson WG, et al. Operative outcomes beyond 30-day mortality: Colorectal cancer surgery in oldest old. Ann Surg (2011) 253(5):947–52. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318216f56e

8. di Sebastiano P, Festa L, Buchler MW, di Mola FF. Surgical aspects in management of hepato-Pancreatico-Biliary tumours in the elderly. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol (2009) 23(6):919–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.10.003

9. Petrowsky H, Clavien PA. Should we deny surgery for malignant hepato-Pancreatico-Biliary tumors to elderly patients? World J Surg (2005) 29(9):1093–100. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-1130-6

10. Papis D, Vagliasindi A, Maida P. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery in the elderly: Current status. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg (2020) 24(1):1–5. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.2020.24.1.1

11. Xu X, He M, Wang H, Zhan M, Yang L. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for gallbladder cancer patients after surgery. BMC Gastroenterol (2022) 22(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s12876-022-02281-2

12. Lin Y, Chen H, Pan F. Prognostic nomograms to predict survival of patients with resectable gallbladder cancer: A surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (Seer)-based analysis. Med Sci Monit (2021) 27:e929106. doi: 10.12659/MSM.929106

13. Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer: Comparison of patients presenting initially for definitive operation with those presenting after prior noncurative intervention. Ann Surg (2000) 232(4):557–69. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00011

14. Zhu X, Zhang X, Hu X, Ren H, Wu S, Wu J, et al. Survival analysis of patients with primary gallbladder cancer from 2010 to 2015: A retrospective study based on seer data. Med (Baltimore) (2020) 99(40):e22292. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022292

15. Wang SJ, Lemieux A, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Ord CB, Walker GV, Fuller CD, et al. Nomogram for predicting the benefit of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy for resected gallbladder cancer. J Clin Oncol (2011) 29(35):4627–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8020

16. Xiao Z, Shi Z, Hu L, Gao Y, Zhao J, Liu Y, et al. A new nomogram from the seer database for predicting the prognosis of gallbladder cancer patients after surgery. Ann Transl Med (2019) 7(23):738. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.11.112

17. Li P, Song L. Prognostic evaluation for patients over 45 years old with gallbladder adenocarcinoma resection: A seer-based nomogram analysis. BioMed Res Int (2020) 2020:6370946. doi: 10.1155/2020/6370946

18. Yao GL. Laparoscopic hepatopancreaticoduodenectomy for synchronous gallbladder cancer and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A case report. World J Surg Oncol (2022) 20(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s12957-022-02628-9

19. Okumura T, Nakamura J, Kai K, Ide Y, Nakamura H, Koga H, et al. Curative resection of gallbladder cancer with liver invasion and hepatic metastasis after chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus s-1: Report of a case. World J Surg Oncol (2014) 12:326. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-326

20. Kim S, Yoon YS, Han HS, Cho JY, Choi Y. Laparoscopic extended cholecystectomy for T3 gallbladder cancer. Surg Endosc (2018) 32(6):2984–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5952-8

21. Cai ZQ, Guo P, Si SB, Geng ZM, Chen C, Cong LL. Analysis of prognostic factors for survival after surgery for gallbladder cancer based on a Bayesian network. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):293. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00491-3

Keywords: PSM, old age, SEER database, OS, CSS, gallbladder cancer

Citation: Xu X, Wang J and Duan Q (2023) Effects of surgery on survival of elderly patients with gallbladder cancer: A propensity score matching analysis of the SEER database. Front. Oncol. 13:1083618. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1083618

Received: 29 October 2022; Accepted: 17 February 2023;

Published: 01 March 2023.

Edited by:

Cosimo Sperti, University of Padua, ItalyReviewed by:

Maolan Li, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Xu, Wang and Duan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qilong Duan, RHVhbnFpbG9uZ3NkbWNAMTI2LmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.